FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Firstmac Limited v Zip Co Limited [2025] FCAFC 30

Appeal from: | Firstmac Limited v Zip Co Ltd [2023] FCA 540 | ||

File number: | NSD 663 of 2023 | ||

Judgment of: | PERRAM, KATZMANN AND BROMWICH JJ | ||

Date of judgment: | 19 March 2025 | ||

Catchwords: | TRADE MARKS – appeal against decision that composite marks not deceptively similar to registered trade mark pursuant to s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act) – whether stylised marks containing the registered trade mark and other words deceptively similar – appeal against decision to uphold defences against trade mark infringement of honest concurrent use under s 122(1)(f) and (fa) of the TM Act and use of own name in good faith s 122(1)(a) – whether respondents acted honestly in use of the mark – appeal against decision to order removal of the appellant’s registered trade mark from the Register of Trade Marks pursuant to s 92(1) and s 92(4)(b) of the TM Act – whether the appellant did not during the relevant non-use period use its registered trade mark in good faith in relation to its services – appeal against decision to order rectification of the Register by cancelling the appellant’s registered trade mark under s 88(1) and 88(2)(c)of the TM Act – whether discretion to not to order removal from the Register exercised in error HELD: Appeal allowed – primary judge erred by finding that stylised composite marks contained the form of the registered mark and another word were not deceptively similar to registered trade mark – defence of honest concurrent use and use of own name in good faith not made out due to honesty not being proven – appellant demonstrated use during the relevant non-use period – trade mark not to be removed from Register – primary judge erred in exercising discretion to cancel appellant’s mark as no blameworthy conduct on part of appellant leading to any confusion caused by appellant’s use of its own mark – trade mark not to be cancelled | ||

Legislation: | Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) ss 7(3), 8, 44(3), 88(1)(a), 88(2)(c), 89, 92(1), 92(4)(b), 100(1)(c), 101, 105, 120(1), 122(1)(a), (f), (fa) Trade Marks Regulations 1995 (Cth) r 8.2 | ||

Cases cited: | Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 56; 124 IPR 264 Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 261 FCR 301 Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; 259 FCR 514 Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budějovický Budvar, Národní Podnik [2002] FCA 390; 56 IPR 182 Berlei Hestia Industries Ltd v Bali Co Inc [1973] HCA 43; 129 CLR 353 Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 1258 Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 156 Dunlop Aircraft Tyres Ltd v Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company [2018] FCA 1014; 262 FCR 76 Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 113; 165 IPR 301 Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 44; 407 ALR 473 Firstmac Ltd v Zipmoney Payments Pty Ltd [2018] ATMO 195; 147 IPR 59 Flexopack S.A. Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; 118 IPR 239 Gain Capital UK Ltd v Citigroup Inc (No 4) [2017] FCA 519; 123 IPR 234; General Electric Co v General Electric Co Ltd [1972] 1 WLR 729 GLJ v Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore [2023] HCA 32; 414 ALR 635 Halal Certification Authority Pty Limited v Flujo Sanguineo Holdings Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 175; 300 FCR 478 HTX International Pty Ltd v Semco Pty Ltd (1983) 1 IPR 403 In Re Parkington & Co Ltd’s Application (1946) 63 RPC 171 Killer Queen, LLC v Taylor [2024] FCAFC 149 Kural v The Queen [1987] HCA 16; 162 CLR 502 McCormick & Company Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335; 51 IPR 102 McD Asia Pacific LLC v Hungry Jacks Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1412; 175 IPR 397 New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-Operative Co Ltd [1990] HCA 60; 171 CLR 363 Pereira v Director of Public Prosecutions [1988] HCA 57; 82 ALR 217 Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; 251 FCR 379 Re Alex Pirie & Sons Ltd’s Trademark Application (1933) 50 RPC 147 Riv-Oland Marble Co (Vic) Pty Ltd v Settef SpA [1988] FCA 553; 19 FCR 569 Saad v The Queen [1987] HCA 14; 70 ALR 667 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; 277 CLR 186 Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; 109 CLR 407 Steven Moore (A Pseudonym) v The King [2024] HCA 30; 98 ALJR 1119 Swancom Pty Ltd v Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 328; 157 IPR 498 Thomas Prince, ‘Recurring Issues in Civil Appeals – Part 2’ (2022) 96 Australian Law Journal 27 | ||

Division: | General Division | ||

Registry: | New South Wales | ||

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property | ||

Sub-area: | Trade Marks | ||

Number of paragraphs: | 184 | ||

Date of hearing: | 16-17 November 2023 | ||

Counsel for the Appellant: | Mr H Bevan SC and Mr W Rothnie | ||

Solicitor for the Appellant: | Spruson & Ferguson | ||

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr A Bannon SC and Mr L Merrick KC | ||

Solicitor for the Respondents: | King & Wood Mallesons | ||

ORDERS

NSD 663 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | FIRSTMAC LIMITED Appellant | |

AND: | ZIP CO LIMITED First Respondent ZIPMONEY PAYMENTS PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM, KATZMANN AND BROMWICH JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 19 march 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The parties confer and within 28 days, or such further time as may be allowed, furnish by email to the associates to Justices Perram, Katzmann and Bromwich agreed or competing draft declarations and orders to give effect to these reasons.

3. If there is any need for further evidence or written submissions, agreed or competing procedural orders to facilitate compliance with order 2, they should be furnished within the same period of time as for order 2.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

PERRAM J:

1 I have had the advantage of reading in draft the joint reasons of Katzmann and Bromwich JJ with which I agree. However, I wish to state my own views on the defence of honest and concurrent use under ss 122(1)(f) and (fa) when read with s 44 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (‘the Act’).

2 The Appellant is the registered owner of the trade mark ZIP. In November 2013, the Second Respondent for the very first time used as a trade mark the wordmark ZipMoney by making the Respondents’ credit and payment services available to the customers of Chappelli Cycles under that name. As Katzmann and Bromwich JJ have explained, the use of the word ZipMoney in that fashion infringed the Appellant’s trade mark ZIP.

3 In their defence, the Respondents relied upon the defence of honest and concurrent use. In an infringement suit, the time at which that defence is to be assessed is the date of the alleged infringement, here November 2013: Killer Queen, LLC v Taylor [2024] FCAFC 149; 306 FCR 199 (‘Killer Queen’) at [193] per Yates, Burley and Rofe JJ; Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; 259 FCR 514 at [217] per Nicholas, Yates and Beach JJ. Further, it is the party asserting the defence, here the Respondents, who must show that their use was an honest one: Killer Queen at [198]. The nature of that legal onus of proof carries with it the prospect that the Respondents may fail to show that their use of the word ZipMoney was an honest use without any corresponding finding by the Court that the use was in fact dishonest. The Court, in other words, must be affirmatively satisfied that the use was an honest one and its failure to be so satisfied does not necessarily entail that it is affirmatively satisfied that the use was dishonest.

4 Mr Gray was chief operations officer, co-founder and a director of the First Respondent (Zip Co) and a director of the Second Respondent (Zipmoney Payments). In early 2013, well before the use as a trade mark of the word ZipMoney in November 2013, he had conducted internet searches in relation to the name ZIP. None of these searches revealed the existence of the Appellant’s registered trade mark, ZIP.

5 It was following this, in June 2013, that Mr Gray and Mr Diamond, who was the Respondents’ managing director, chief executive officer and co-founder and a director of Zipmoney Payments, had then decided to use the words ZIP and ZIPMONEY for their business. Following that decision, it appears that the Respondents took steps to prepare for the launch of the business. These steps included the preparation of artwork for logos, an application to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission for a credit licence, and the applications for the registration of trade marks involving the word ZIP.

6 Although the word ZIP was used in each of these activities, it was not used as a trade mark because none of these uses involved the provision of its services by reference to that word. These uses did not therefore involve any trademark use of the word ZIP.

7 The trial judge was satisfied that at the time Mr Gray and Mr Diamond decided that they would use the word ZIP in June 2013 they did not know of the Appellant’s registered trade mark, ZIP. However, counsel for the Respondents below made a beguiling submission to her Honour which had two elements. First, it was clear that the Respondents’ initial use of the word ZIP must have been honest since nothing in the internet searches Mr Gray had conducted had indicated the existence of the Appellant’s mark, ZIP. Secondly, it was difficult to see that a use which had started off as plainly honest (when Mr Diamond and Mr Gray decided to use the ZipMoney mark for their business in June 2013) could have become dishonest by the time the word ZipMoney came to be used as a trade mark in November 2013.

8 The difficulty with this submission is that it involves a deft misdirection. The misdirection is that the Respondents had used the word ZipMoney as a trade mark prior to November 2013 whereas in fact they had never used the word ZipMoney as a trade mark before that time at all. Rather, the Respondents’ first use of the word ZipMoney as a trade mark occurred when partnering with Chappelli Cycles in November 2013 to make their credit and payment services available to its customers. The submission therefore invited the trial judge to assess the honesty of the Respondents’ use of the word ZipMoney as a trade mark at a time when they were not using it as a trade mark.

9 As I have already mentioned, after Mr Gray and Mr Diamond decided to use the word ZipMoney for the Respondents’ business in June 2013 but before they did in fact use it in November 2013, the Respondents applied for the registration of their own trade marks based on the word ZIP. Two applications were lodged towards the end of August 2013. These trade mark applications received adverse examination reports in October 2013 which explicitly drew to the Respondents’ attention the existence of the Appellant’s registered ZIP trade mark and the obstacle to registration it posed.

10 The case does not present therefore as one in which the Respondents had commenced using the word ZipMoney as a trade mark and only then to discover that it was also someone else’s trade mark. Rather, it is one in which the Respondents were on notice from the time of the adverse examination reports in October 2013 of the existence of the Appellant’s registered trade mark but, even so, decided to launch their services and start using the trade mark ZipMoney anyway in November 2013.

11 Of course, that does not necessarily mean that the Respondents’ use in November 2013 could not have been an honest use of the ZipMoney mark. For example, in some cases a Respondent may have genuinely believed, despite the existence of the known anterior mark, that its own use of its mark was unlikely to lead to confusion: McCormick & Company Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335; 51 IPR 102 at [32]-[33] per Kenny J and the cases there collected.

12 Whilst the concept of honest use is in terms of a subjective inquiry, this Court has accepted that it has an objective element. In particular, it has been accepted by this Court that use will not be honest use within the meaning of the provision if the allegedly infringing party does not take steps that an honest and reasonable person would take to ascertain its ability to use the trade mark and has in effect taken a risk. So much was explained by Beach J in Flexopack SA Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; 118 IPR 239 (‘Flexopack’) at [111] in relation to s 122(1)(a) (honest use of a person’s name) of the Act and there is no reason to think that this reasoning does not apply to ss 122(1)(f) or (fa) (honest use where registration would be granted). Subsequently, the observation of Beach J was applied by the Full Court in the context of s 122(1)(a) in Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; 251 FCR 379 (‘Pham’) at [103].

13 On the question of honest use, the facts found by the trial judge were these:

(1) Mr Gray had undertaken internet searches in the first part of 2013 for the name ZIP and the Appellant did not lead evidence to contradict that;

(2) Mr Gray and Mr Diamond had decided to proceed with the business using the word ZIP in June 2013;

(3) Mr Diamond had applied to register the Respondents’ trade marks in August 2013;

(4) Adverse examination reports were received in October 2013 which drew to the Respondents’ attention the existence of the Appellant’s trade mark;

(5) Mr Diamond was aware of the contents of the examination reports and hence of the Appellant’s trade mark;

(6) Mr Diamond and Mr Gray did not decide to get any legal advice about the adverse reports;

(7) Mr Diamond did, however, seek extensions of time for both trade mark applications which were granted through to February 2015;

(8) At the time of the adverse reports, Mr Diamond was distracted with establishing the business and consequently did not give the adverse reports and the question of the registration of the Respondents’ marks much attention;

(9) Mr Diamond gave no evidence for why he let the trade mark applications lapse; and

(10) As at November 2013, so far as Mr Diamond and Mr Gray were aware, there was no other trader conducting the same business as the Respondents using the word ZIP.

14 The trial judge drew the inference that the use of the word ZipMoney in November 2013 was an honest use. In my respectful opinion, her Honour was led into error in this regard by the Respondents’ submission that it was difficult to see how a use which had been honest in June 2013 could cease to be such in November 2013. If there had been an honest trademark use in June 2013 I would be disposed to see the force of this contention. On that view of affairs, once it was shown that there had been a use of ZipMoney as a trade mark in June 2013 and that the use was an honest one then it would be difficult to see how a subsequent trademark use in November 2013 could lack that quality. But those were not the facts. There was no honest trademark use in June 2013 because there was no trademark use at all.

15 Like Katzmann and Bromwich JJ, I nevertheless agree that these earlier events were not irrelevant to the factual determination the trial judge had to make viz whether the use in November 2013 was an honest one. But where the events in June 2013 had not included any use of the word ZipMoney as a trade mark these earlier events could not quarantine the analysis from the subsequent event of the adverse reports which occurred before that use.

16 Error being established the question then becomes what inference this Court should now draw. I am unpersuaded from the facts set out above that an inference should be drawn that the Respondents acted honestly in using the word Zip and the variants of it as trade marks in November 2013. This is not to say that I am affirmatively persuaded that the Respondents’ use was dishonest. Rather, what is involved is a failure by the Respondents to discharge their onus of proving the defence. In particular, in terms of Flexopack and Pham, I am unpersuaded that it is not the case that they failed to take steps that an honest and reasonable person would take to ascertain their ability to use the trade mark and in effect took a risk.

17 I agree with orders proposed by Katzmann and Bromwich JJ.

I certify that the preceding seventeen (17) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

Associate:

Dated: 19 March 2025

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

KATZMANN AND BROMWICH JJ:

INTRODUCTION

18 This is an appeal by Firstmac Limited from orders made by a judge of this Court by which her Honour dismissed an originating application seeking relief against related respondents, Zip Co Limited and Zipmoney Payments Pty Ltd, alleging trade mark infringement contrary to s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act or Act). The primary judge also:

(a) upheld an application by Zipmoney Payments for removal of Firstmac’s mark from the Register of Trade Marks for non-use of that mark, ordering that the mark be removed from the Register; and

(b) allowed part of a cross-claim by which the respondents sought rectification of the Register and cancellation of Firstmac’s trade mark, making orders to that effect; and

(c) awarded costs to the respondents.

19 By its notice of appeal, Firstmac seeks:

(a) to have the primary judge’s orders set aside and instead to have declarations of infringement made;

(b) to have injunctions granted that restrain the respondents from using the “ZIP” word mark in relation to certain services, or any mark or sign that is substantially similar in Australia, orders to deliver up various domain names;

(c) dismissal of both the respondents’ cross-claim and non-use application

(d) costs; and

(e) remittance of the matter to the primary judge for an inquiry and determination as to damages.

20 For the reasons below, the appeal succeeds. The relief sought by Firstmac should be granted.

Overview

21 In these reasons:

(a) all references to legislative provisions will be to those in the TM Act unless indicated to the contrary;

(b) references to a “Trade Mark” will be a reference to a mark registered under the TM Act; and

(c) references to “trade marks” or “marks” will be references to trade marks or marks of trade which are not necessarily registered.

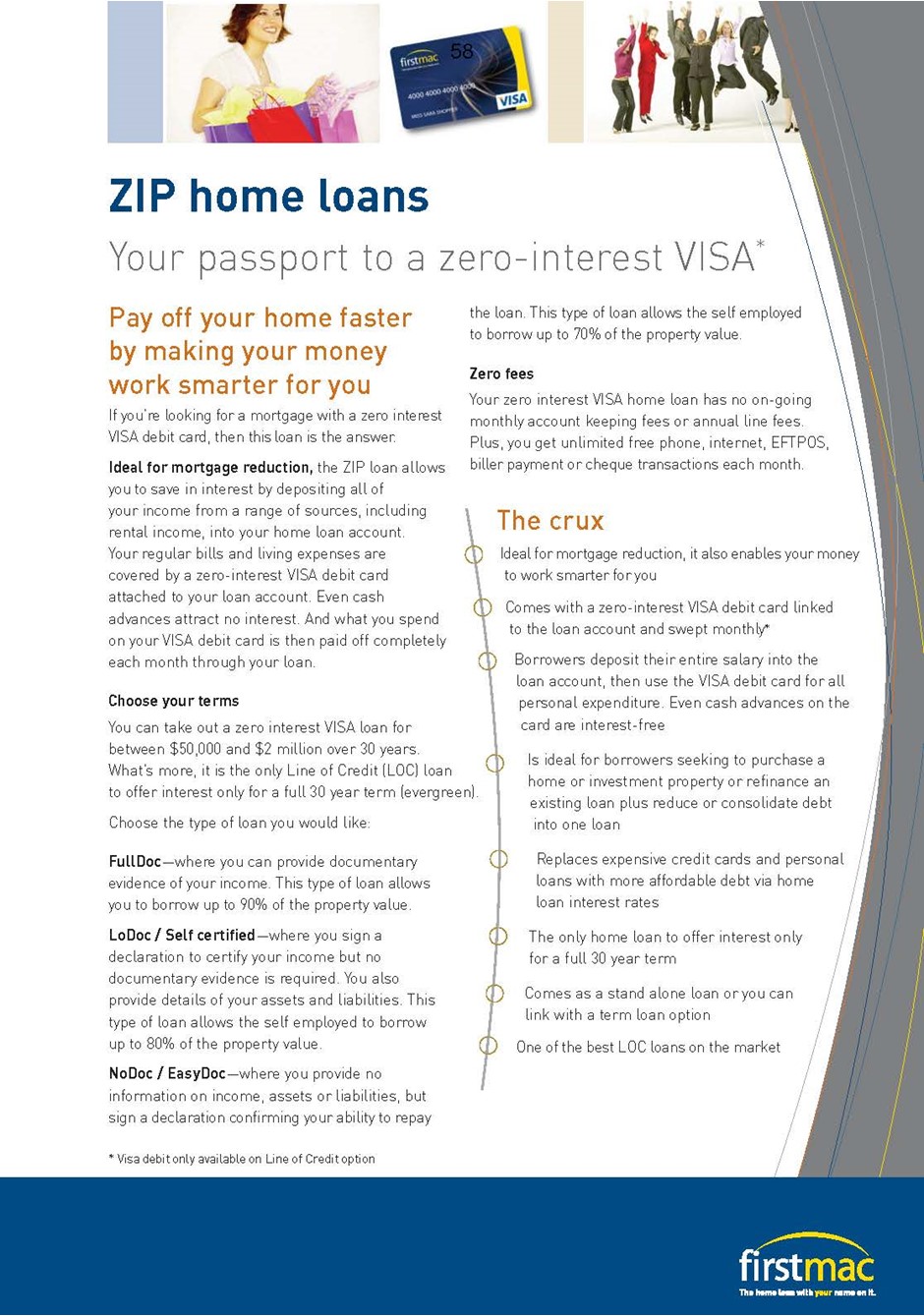

22 Since 2004, Firstmac has been the registered owner of Trade Mark 1021128 (Firstmac Mark) for the word “ZIP” in respect of “financial affairs (loans)” in class 36 (Services). Firstmac is part of a group of companies referred to as the Firstmac Group. The Firstmac Group is Australia’s largest non-bank lender, providing a range of financial products and services, including home and car loans, and investment products.

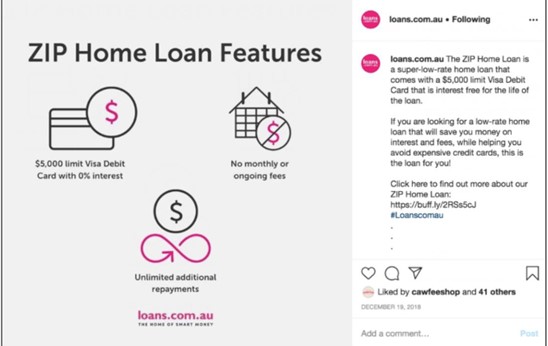

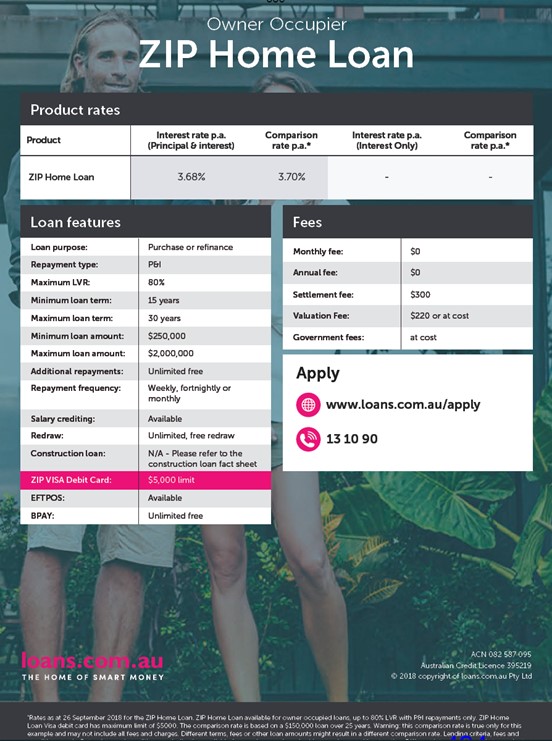

23 Since 2013, the respondents have operated what is commonly known as a buy now pay later (BNPL) service. That service provides unsecured loans in the form of credit facilities to customers buying products and services from a range of retailers who have agreed to payment by that means. The respondents provide the BNPL service using the trade mark “Zip” or “ZIP”, either on its own, or in connection with another word, such as “money”, “pay”, “trade” or “business”, both as plain words and in stylised formats, as well as using a number of domain names including that word.

24 The use of the word “zip” connoted different things in their usages by the parties, meaning “nothing” in the sense of Firstmac’s use and “speedy” in the sense of the respondents’ use. In the case of Firstmac’s use, it referred to a central feature of its loan product whereby there was no cost to the customer of an associated debit card facility. In the case of the respondents’ use, it referred to the speed of the service provided.

25 The marks used by the respondents at issue on Firstmac’s case were conveniently identified in Annexure A to the primary judge’s reasons, and are extracted and included as Annexure A to these reasons, being essential to understanding both judgments. Those marks fell into two categories:

(a) Stylised Zip Marks which contain only the word “ZIP”, stylised in various colours and fonts, which were not the subject of any real contest as to deceptive similarity in light of her Honour’s reasoning and conclusions, being items 1 to 6 in Annexure A; and

(b) ZIP Formative Marks which each include the word “ZIP” and another ordinary English word, to make word combinations such as “ZIP PAY” and “ZIP MONEY”, and were also largely stylised, which was the substance of the real contest on deceptive similarity, being items 7 to 25 in Annexure A.

26 Domain names owned by one or the other of the respondents comprising or including the word “ZIP” were also in issue, being items 26 to 29 in Annexure A.

27 At the hearing before the primary judge:

(a) Firstmac alleged that the respondents had infringed the Firstmac Mark in breach of s 120(1);

(b) the respondents relied upon defences of honest concurrent use, and use of own name in good faith;

(c) by the respondents’ cross-claim, they sought cancellation of the Firstmac Mark under s 88(2)(c), as well as removal for non-use;

(d) the respondents also claimed common law rights in the trade mark “ZIP” and variants such as “ZIP MONEY” and “ZIP PAY”;

(e) the respondents admitted that the name and trade mark “ZIP” is substantially identical to the Firstmac Mark, and, subject to defences they advanced, their cross-claim and their application for non-use, admitted their conduct was otherwise infringing.

28 The primary judge dismissed Firstmac’s originating application, and ordered that the Firstmac Mark be removed from the Register pursuant to s 92(4)(b) and cancelled pursuant to s 88(2)(c). The order removing and cancelling the Firstmac Mark is stayed until the conclusion of this appeal. Firstmac has entered into an undertaking to the Court not to threaten any person with claims of, or proceedings for, infringement of the Firstmac Mark during the stay.

Grounds of Appeal

29 The notice of appeal contains the following six grounds:

1. The primary judge erred in failing to find that each of the Zip Formative Marks and domain names held by the respondents were not deceptively similar to the Firstmac Mark.

2. The primary judge erred in finding that a defence under s 122(1)(f) or (fa), of honest concurrent use, was made out.

3. The primary judge erred in holding that a defence under s 122(1)(a) of good faith use of corporate name was made out.

4. The primary judge erred in holding that Firstmac had not used the Firstmac Mark in relation to the registered services in the period from 22 February 2016 to 22 February 2019, and also in failing to exercise the discretion against removal of the Firstmac Mark.

5. The primary judge erred in holding that the Firstmac Mark should be cancelled by finding that the ground in s 88(2)(c) was made out, and erred by failing to exercise the discretion not to cancel the Firstmac Mark.

6. The primary judge should have found that the respondents had infringed the Firstmac Mark.

30 Firstmac identified and addressed four main issues arising from the six grounds of appeal, being those concerned with deceptive similarity, the defences, non-use and cancellation of the Firstmac Mark. Firstmac submits that ground 1, being the challenge to the finding that there was no deceptive similarity in relation to the ZIP Formative Marks, is an essential step in the infringement analysis including as to the operation of the use of corporate name defence, and so has significance in relation to the other grounds and would also have an impact on the scope for relief. Firstmac accepts that it needs to succeed on both grounds 4 and 5 to reverse the primary judge’s removal and cancellation orders. Ground 6 has no independent life, but rather flows from the preceding grounds.

31 The respondents contend that ground 1 (and thus ground 6) are only of any significance if Firstmac succeeds on its case in relation to the defences in grounds 2 and 3.

Chronology of key events

32 Each of the parties provided a chronology of relevant events for the purposes of this appeal. The following key events were either not in dispute between the parties, or are otherwise the subject of findings by the primary judge that are not challenged on appeal, and as such serve to summarise succinctly the sequence of events and, when considered with Annexure A, provide much of the historical factual context necessary for the consideration of the grounds of appeal:

Date | Event |

Early 2005 | Firstmac first launched ZIP home loan products. |

About November 2012 | Mr Larry Diamond and Mr Peter Gray (of the respondents) met to discuss business opportunities, including short term digital lending. Mr Diamond had the word “ZIP” in mind because it had connotations with fast movement. |

19 November 2012 | Mr Diamond registered the domain name zipmoney.com.au. |

Early 2013 | Mr Gray undertook internet searches in relation to the name “ZIP”, none of which returned results for the Firstmac home loan products. Messrs Diamond and Gray began developing the preliminary business model, such as the product and technology required for the product, and began pitching it to potential retailers and seeking capital. At this time they were using the name “ZIP” to refer to the business but were still discussing other options. |

By June 2013 | Messrs Gray and Diamond decided to use the names “ZIP” and “ZIPMONEY” for their business. |

24 June 2013 | Zipmoney Holdings Pty Ltd and Zipmoney Payments Pty Ltd (then Zipmoney Pty Ltd) were incorporated. |

June to mid-August 2013 | Mr Diamond took some steps to inform himself about trade marks and their registration. |

18 July 2013 | First non-use period begins. |

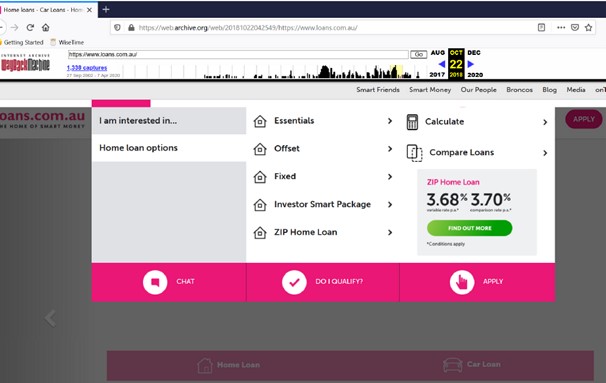

19 and 20 August 2013 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd filed Trade Mark applications 1575528 for “zipMoney” logo in class 36 and 1575717 for “zip” logo in class 36:

|

3 September 2013 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd obtained its credit licence from ASIC (no. 441878) which allowed it to engage in credit activities. |

October 2013 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd received adverse examination reports from IP Australia in relation to the August trade mark applications (2013 IP Australia Adverse Reports). Mr Gray collected those reports and understood from them that the trade mark applications had not been accepted, but did not read them in detail. Mr Gray provided the adverse reports to Mr Diamond who only gave them cursory attention. They did not seek legal advice in relation to the 2013 IP Australia Adverse Reports or connected trade mark applications. Mr Diamond believes this is when he first became aware of Firstmac. |

Late November 2013 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd partnered with its first retail merchant, Chappelli Cycles, and its credit and payment services were available to customers of that business (being members of the Australian public). |

January 2014 | By this time, the zip.com.au website showed that Zipmoney Pty Ltd had signed with five merchants. |

Early 2014 | Firstmac ceased offering ZIP home loans to new customers, but continued to service existing loans, including the issuance of statements for each original ZIP home loan. |

September 2014 | Loans.com.au entered into a mortgage origination and management agreement with Firstmac Origination to act as a mortgage originator exclusively for Firstmac products and services and to promote those products and services. Firstmac still dealt with the loan arrangements from and after the loan agreement stage. Since that date, Firstmac regularly issued product rate sheets to Loans.com.au setting out new products and services and changes to existing products and services. |

8 December 2014 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd applied for an extension of time to respond to the 2013 IP Australia Adverse Reports through their lawyers in Mr Diamond’s name, though he has no recollection of seeking that extension. That extension of time was granted, but Zipmoney Pty Ltd did not respond to the 2013 IP Australia Adverse Reports. |

February 2015 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd’s 2013 trade mark applications lapsed. |

April-September 2015 | Rubianna Resources Limited, an ASX listed mining and resources company, agreed to exercise an option to acquire shares in Zipmoney Pty Ltd by acquisition of all shares in Zipmoney Holdings. This was announced to the ASX. |

14 June 2015 | Zipmoney Pty Ltd changed its name to Zipmoney Payments Pty Ltd. |

25 June 2015 | Four trade mark applications were filed on behalf of Zipmoney Payments for registration of the following marks in class 36: application no. 1703059 for

application no. 1703060 for

application no. 1703102 for the word ZIP; and application no. 1703103 for the word ZIPMONEY. |

21 and 22 July 2015 | The Trade Marks Office issued adverse examination reports for applications no. 1703059, no. 1703060, no. 1703102 and no. 1703103. |

11 August 2015 | Rubianna Resources issued the prospectus for the public offering of 20 million shares. That prospectus included the identification of “key risks” and “risk factors”. Relevantly, that in turn included that Zipmoney Payments did not have its own Trade Mark, there were a number of prior registered Trade Marks similar to the trade marks used by Zipmoney Payments, and there was a risk that the owners of those Trade Marks may assert rights against Zipmoney Payments. |

14 August 2015 | Mr Omond, a trade mark attorney advising Rubianna Resources, undertook internet searches to see when Firstmac stopped using the Firstmac Mark and sent copies to Mr Diamond. Mr Omond sent an email to Mr Diamond titled “Trade Mark Removal actions – update” with a draft letter to Firstmac “requesting consent”. Mr Diamond sent a calendar invitation to Mr Gray and Adam Finger (of the respondents) with the subject line “ATTACK FIRSTMAC TRADEMARK ‘ZIP’…” |

7 September 2015 | The respondents registered the domain name zipmoneylimited.com.au. Rubianna Resources was renamed Zipmoney Limited. |

21 September 2015 | Zipmoney Limited reverse listed on the ASX. |

10 October 2015 | Zipmoney Payments registered the domain name zippay.com.au. |

7 December 2015 | Zipmoney Limited was renamed Zip Co Limited. |

10 December 2015 | On behalf of Zipmoney Payments, a trade mark registration application was made for the word ZIPPAY in class 36. |

December 2015 | The respondents launched the ZIP PAY service. From this point on it was available to Australian customers. |

22 February 2016 | Second non-use period begins. The first and second non-use periods overlap between 22 February 2016 and 18 July 2016. |

8 March 2016 | The Trade Marks Office issued an adverse examination report in relation to the ZIPPAY trade mark application. |

18 July 2016 | First non-use period ends. |

19 August 2016 | Zipmoney Payments filed a s 92(4)(b) application seeking removal of the Firstmac Mark from the Register (first non-use application). Firstmac opposed the application. |

August or September 2016 | Mr Gration of Firstmac first became aware of Zipmoney Payments following the application for removal of the Firstmac Mark on the grounds of non-use. |

December 2016 | The respondents engaged Christopher Doyle & Co, a marketing agency, to undertake a brand identity assessment and redesign the ZIP brand. |

19 January 2017 | Zipmoney Payments registered the domain name zip.co. |

4 April 2017 | Zipmoney Payments applied to register Australian trade marks for ZIPME, ZIPNOW and ZIPUP (nos 1836052, 1836053 ad 1836054). |

June 2017 | Christopher Doyle & Co present a proposed rebrand strategy to the respondents, which included adopting the master brand of “ZIP”. |

9 May 2018 | Zipmoney Payments filed Australian trade mark applications for ZIP IT and JUST ZIP IT (nos 1925411 and 1925412). |

13 June 2018 | Mr Diamond emailed Mr Gray and Mr Philip Crutchfield QC, a director of Zip Co, suggesting a process by which he would seek a meeting with Mr Kim Cannon, owner of Firstmac. |

15 June 2018 | Mr Gration sent an email to others at Firstmac asking them to consider product and legal requirements to launch a new product with the working title “zip home loan”. |

19 June 2018 | The respondents rolled out a rebrand to all merchants, adopting head brand “Zip” and new logos. The rebrand cost approximately $1.09 million. |

19 and 20 June 2018 | Mr Diamond messaged Mr Cannon of Firstmac. That message was replied to by Mr Rod Minnell, Executive Director of Firstmac, the next day suggesting the two speak. This was the first approach to Firstmac by the respondents. |

20 June 2018 | Representatives of Firstmac and the respondents spoke. That same day Mr Minell emailed Mr Diamond, including the following statement: It is our intention to maintain ownership of the trademark. Thank you for expressing your interest. |

26 July 2018 | Mr Gration sent an internal Firstmac email about launching a new home loan under the name ZIP which included a visual guide as to how the loan was to be structured and included the words “Zip zero zilch interest on ZIP Saver Account”. |

July or August 2018 | The Zip mobile application (Zip App) was released by the respondents. |

27 September 2018 | Zipmoney Payment’s first non-use application was heard by a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks. That application was opposed by Firstmac and defended by Zipmoney Payments. |

September 2018 | Firstmac relaunched the ZIP home loan product as a term loan and VISA debit card. This product has been promoted on the Firstmac website since then. |

4 December 2018 | Zipmoney Payment’s first non-use application against Firstmac for non-use of the Firstmac Mark was dismissed by a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks upon the basis that the evidence, by way of a loan statement, established that there had been genuine commercial use of the Trade Mark with respect to the specified services in the registration during the relevant period: Firstmac Ltd v Zipmoney Payments Pty Ltd [2018] ATMO 195; 147 IPR 59. |

21 December 2018 | Zipmoney Payments filed Australian trade mark applications for: ZIP (No. 1977513); ZIP MONEY (no. 1977514) ZIP PAY (no. 1977515) ZIP CARD (no. 1977520) ZIP BILLS (no. 1977521) ZIP BIZ (no. 1977522); and |

8 March 2019 | Firstmac sent its first letter of demand via its solicitors to Zipmoney Payments in relation to its use of the ZIP trade mark and its variants, and demanding Zipmoney Payments cease use of the ZIP trade mark. |

22 February 2019 | End of the second non-use period. |

22 March 2019 | Zipmoney Payments filed a second application seeking removal of the Firstmac Mark from the Register (second non-use application). |

7 June 2019 | Zipmoney Payments filed an Australian trade mark application for ZIP ANYWHERE (no. 2014916). |

20 June 2019 | Firstmac commenced proceedings in the Federal Court for Trade Mark infringement against the respondents. |

30 July 2019 to 31 August 2020 | Zipmoney Payments lodged a further five (5) trade mark applications for marks including the word “ZIP” either with other words or in a stylised form. |

21 August 2019 | The 22 March 2019 second non-use application was referred to this Court for determination. The application was supported in the Court by points of claim, which asserted Firstmac did not use the Firstmac Mark at any time during the relevant period for the second non-use period, within the meaning in s 92(4)(b)(i), or alternatively had not used it in good faith, within the meaning in s 92(4)(b)(ii), rendering it liable to removal from the Register pursuant to s 101. |

9 September 2019 | A Certificate of Use under s 105 was issued to Firstmac by the Acting Deputy Registrar of the Trade Marks Office in accordance with the finding in relation to the first non-use application. |

February 2020 | Firstmac began launching its relaunched 2018 Zip home loan product to over 8,000 accredited mortgage brokers in Australia. |

August 2021 | Zipmoney Payments commenced a progressive rebrand, which included new stylised marks, in order to unify the brand following the acquisition of a US BNPL business. |

DECEPTIVE SIMILARITY

33 The substance of Firstmac’s case on deceptive similarity is that the primary judge correctly stated the law, but then misapplied it, essentially at the practical level.

34 The relevant legal principles can be shortly stated, as they emerge succinctly from the restatement in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; 277 CLR 186 (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ). In the following key paragraphs the references to goods may be taken to have equivalent operation in relation to the present situation involving financial services (footnotes omitted):

[22] There are two separate and essential elements to establish infringement under s 120(1): (1) that the person has “use[d] as a trade mark” a sign in relation to goods or services; and (2) that the trade mark was “substantially identical” or (as alleged in this case) “deceptively similar” to a trade mark registered in relation to those goods or services.

[Paragraphs 23-25 are reproduced below in relation to ground 4]

Deceptive similarity to the registered mark

Nature of the inquiry

[26] Section 10 of the TM Act, headed “Definition of deceptively similar”, provides that a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it “so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion”. The essential task is one of trade mark comparison; the resemblance between the two marks must be the cause of the likely deception or confusion. In evaluating the likelihood of confusion, the marks must be judged as a whole, taking into account both their look and their sound.

[27] The principles for assessing whether a mark is deceptively similar to a registered trade mark under s 120(1) are well established. In Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v F S Walton & Co Ltd, Dixon and McTiernan JJ explained the task in these terms:

“But, in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained.”

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. The effect of spoken description must be considered. If a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods, then similarities both of sound and of meaning may play an important part.”

[28] The question to be asked under s 120(1) is artificial – it is an objective question based on a construct. The focus is upon the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers. The buyer posited by the test is notional (or hypothetical), although having characteristics of an actual group of people. The notional buyer is understood by reference to the nature and kind of customer who would be likely to buy the goods covered by the registration. However, the notional buyer is a person with no knowledge about any actual use of the registered mark, the actual business of the owner of the registered mark, the goods the owner produces, any acquired distinctiveness arising from the use of the mark prior to filing or, as will be seen, any reputation associated with the registered mark.

[29] The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. The marks are not to be looked at side by side. Instead, the notional buyer’s imperfect recollection of the registered mark lies at the centre of the test for deceptive similarity. The test assumes that the notional buyer has an imperfect recollection of the mark as registered. The notional buyer is assumed to have seen the registered mark used in relation to the full range of goods to which the registration extends. The correct approach is to compare the impression (allowing for imperfect recollection) that the notional buyer would have of the registered mark (as notionally used on all of the goods covered by the registration), with the impression that the notional buyer would have of the alleged infringer’s mark (as actually used). As has been explained by the Full Federal Court, “[t]hat degree of artificiality can be justified on the ground that it is necessary in order to provide protection to the proprietor’s statutory monopoly to its full extent”.

(Emphasis added.)

35 It is convenient to begin with the respondents’ defence of the primary judge’s reasoning and conclusion on the topic of deceptive similarity.

36 The respondents effectively conceded that the primary judge erred by comparing the impression the notional buyer would have of the respondents’ marks as actually used with the impression the notional buyer would have of Firstmac’s mark as actually used, rather than as notionally used on all services covered by the registration. Nevertheless, the respondents contended that the outcome would be no different if the correct approach were taken because her Honour’s other reasons supported the same conclusion and this Court would be satisfied that there was no risk of confusion.

37 None of the arguments for the respondents were compelling, especially as they did not engage with the substance and detail of the ground of appeal and submissions in support of it. Thus, the fate of this ground largely turns on an examination of the primary judge’s reasons and an evaluation of Firstmac’s arguments.

38 The respondents also submit that, if this ground is upheld, while it may add to the infringing conduct of the respondents, it is only of significance if grounds 2 and 3, addressing the defences, are also upheld. That is plainly correct as a matter of logic, but the question of whether the primary judge erred on this ground of appeal as a threshold matter remains unavoidable for it is only necessary to consider the defences if ground 1 succeeds.

39 It is not in doubt that the respondents used the word “ZIP” in the provision of financial services, that is, in the same category in which the Firstmac Mark is protected, albeit that the sector of the financial services market which each side occupied was quite different. The respondents admitted that the name and trade mark “ZIP” taken alone is substantially identical to the Firstmac Mark. They could hardly do otherwise, and the limited contrary arguments advanced before the primary judge justifiably received short shrift from her Honour. This encompassed conclusively the stand-alone use of the word “Zip”, in upper or lower case (items 1 to 6 in Annexure A), and the sole use of “Zip” as the substantive domain name (item 26 in Annexure A), which were correctly characterised by her Honour as substantially identical to the Firstmac Mark.

40 However, when turning to deceptive similarity, her Honour found that items 7 to 25 of Annexure A, being the ZIP Formative Marks, as well as domain names of the respondents containing the word “ZIP” accompanied by other words, in items 27 to 29 of Annexure A, were not deceptively similar to the Firstmac Mark: PJ [198]-[207], [223]-[224]. In reasoning to this conclusion, the primary judge correctly identified the relevant question as “whether the ZIP Formative Marks so closely resemble the [Firstmac] Mark for financial affairs (loans) in class 36 that they are likely to deceive or cause confusion about the source of the services”: PJ[212]. Her Honour also articulated the test as one which concerns the notional buyer’s imperfect recollection of the registered trade mark, used in relation to the full range of services to which the registration extends, by comparing the impression (imperfectly recollected) of that mark against the impression of the alleged infringer’s mark as used: PJ [212]. Her Honour formed the view that there was “no real tangible danger of deception or confusion occurring from use of the ZIP Formative Marks”: PJ[213].

41 The primary judge found that the similarity between the Firstmac Mark and each of the ZIP Formative Marks begins and ends with the use of the word “ZIP”. Because the respondents’ ZIP Formative Marks include an additional word (or words) attaching to “ZIP”, being ordinary English words, her Honour found they operated to distinguish the ZIP Formative Marks from the Firstmac Mark both visually and aurally to the notional buyer: PJ[214]-[215]. These words include “money”, “pay” “business”, “trade”, “card” and others that are used in conjunction with the word “ZIP”. Her Honour did not accept that the essential feature in each of the ZIP Formative Marks was the use of the word “ZIP”, instead giving each of the two words in the ZIP Formative Marks, “ZIP” and one of those ordinary English words, equal weighting, and finding that neither took prominence: PJ[216].

42 The primary judge found that, as the ZIP Formative Marks each use additional ordinary English words which serve to distinguish those ZIP Formative Marks visually and aurally from the Firstmac Mark, the word “ZIP” is not an essential feature of each of the ZIP Formative Marks as it has equal weighting to the other word/s in the ZIP Formative Marks, with “ZIP” being absorbed into the made-up merged word (such as ZIPPAY and ZIPMONEY): PJ [214]-[217]. The primary judge held that the stylised ZIP Formative Marks, which have been used since 2018 by the respondents, have distinctive elements and a use of colour which visually distinguished them from the Firstmac Mark.PJ [218-219]) The primary judge also referred to her own judgment in Gain Capital UK Ltd v Citigroup Inc (No 4) [2017] FCA 519; 123 IPR 234 in relation to the mark “CITYINDEX” and Halley J’s judgment in Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 113; 165 IPR 301 in relation to the mark “MOTHERSKY” in support of this conclusion.

43 The primary judge next considered “whether the notional buyer would be caused to wonder whether the services came from the same source”: PJ[220]. The context her Honour identified for this enquiry was in relation to home loan products for the Firstmac Mark, and for ZIP, contrasting online use for home loans and related features by Firstmac with in-person retail short term small loan products by the respondents. Her Honour found that “[i]n those circumstances, there is no real tangible danger of confusion or deception between the [Firstmac] Mark on the one hand and the ZIP Formative Marks on the other”: PJ[221]. Her Honour also referred to there being no evidence of actual confusion among customers having occurred in relation to the marks: PJ [222].

44 Firstmac submits that, despite identifying the reasoning process required, especially by reference to Self Care v Allergan, the primary judge failed to apply it correctly.

45 Firstmac challenges the finding by the primary judge that the ZIP Formative Marks were not deceptively similar to the Firstmac Mark upon the bases that:

(a) the question for this Court is what is the correct, or proper, impression an ordinary consumer would take from the respondents’ various marks all of which include the word “ZIP”;

(b) the “dominant cognitive cue” in each case is the word “zip” operating as a “badge of origin” in order to distinguish the services it provided from those provided by others, citing the use of that phrase in Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 56; 124 IPR 264 (Greenwood, Besanko and Katzmann JJ) at [206]; see also [223] and [258]-[259];

(c) in relation to loan or credit and payment services the word “zip” is wholly distinctive and not descriptive, whereas the words that accompany “ZIP” in each of the ZIP Formative Marks (such as “money”, or “it”, “bills” etc) should be read in the context of the respondents’ admission that they are all words in relation to financial affairs and loans, and are words of plain and ordinary meaning which are descriptive in nature and do nothing to distinguish them from the Firstmac Mark;

(d) “ZIP” then serves the function of signalling to the consumer that ZIP is the provider of those services.

46 The practical thrust of Firstmac’s argument on appeal was captured in its reply submissions to the evocative effect that the matters of impression involved in deceptive similarity in the area of financial affairs and loans is that a hypothetical person with an imperfect recollection of the Firstmac Mark may be caused to wonder whether, for example, Zip Pay or Zipmoney is a kind of loan, and be led to think that it was something additional from the people who provided the Zip home loans, or another offering being made by them.

47 The resolution of this ground ends up turning on the evaluative exercise carried out by the primary judge being replicated by this Court on appeal in order to discern the presence or absence of error. This Court is at no disadvantage to her Honour in that respect. The only real issue is whether or not the respondents’ marks in items 7 to 25 in Annexure A had sufficient resemblance to the Firstmac Mark to be deceptively similar, to be assessed by reference to the notional full use of the Firstmac Mark and the actual use of the ZIP Formative Marks.

48 Respectfully, the primary judge may be seen to have erred in a number of independent and important respects, which individually and in combination have produced an erroneous conclusion.

49 First, it was incorrect to treat the services being provided by Firstmac and the respondents as being relevantly different when regard is had to the requirement adverted to in Self Care v Allergan at [29] to consider the notional use by a Trade Mark owner across the full range of services to which that mark could be applied and compare that to the actual use by the alleged infringer. BNPL services were within the range of services able to be covered by the Firstmac Mark, such that confining consideration to how that mark had in fact been used only for loans brings to bear the wrong comparison in the sense of being incomplete. In these particular circumstances, that full range could readily apply to extended financial services, such as BNPL, of the kind provided by the respondents. It is not stretching the concept of a full range to contemplate a home loan provider such as Firstmac also providing BNPL services. That is the required mindset for the comparative exercise required to be carried out. Thus, the full notional use by Firstmac, including BNPL, needed to be compared with the actual use by the respondents for BNPL.

50 That “ZIP” was a mark in fact used for home loans does not diminish the significance of its potential use for consumer loans. This is all the more significant when consideration is given to the admission by the respondents that they used certain marks containing the word “ZIP” in relation to credit and payment services, admitting broadly that the respondents’ services are services in respect of “financial affairs (loans)”, the category in which the Firstmac Mark is registered.

51 Second, the assessment by the primary judge that the word “ZIP” as used by the respondents was equal in prominence to each of the other words used with it failed to have regard to the distinction between the former as being distinctive and non-descriptive, and each of the latter as being non-distinctive and descriptive. Moreover, her Honour also treated the usage of “ZIP” as being substantially the same as the usage of the other words, whereas that usage clearly differed with the former being emphasised, especially in the logo usage, by use of a range of visual devices for “ZIP” as depicted by a number of the items within the ZIP Formative Mark range from items 7 to 25 in Annexure A, such as colour, a stylised use of the “Z”, bolder lettering, or the other word being used as part of the word “ZIP”, including in place of the “i”,. To express this evocatively, the image conveys that “ZIP” is the kind of, or provider of, the pay, money, payments, trade or business, in the sense of a badge of origin.

52 Third, the primary judge’s reliance on Gain Capital and Energy Beverages was misplaced. Her Honour referred to her reasons in Gain Capital at PJ[107]-[108] to support her conclusion that neither word used in the ZIP Formative Marks could be characterised as the essential feature of the mark as “neither takes prominence”. Whatever the position may have been in Gain Capital where the competing marks were CITYINDEX and CITI, in our view, the same reasoning does not apply to the ZIP Formative Marks.

53 The relevant passage in Energy Beverages did not survive an appeal: Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 44; 407 ALR 473at [161]-[166] (Yates, Stewart and Rofe JJ). The primary judge referred to Energy Beverages at PJ[217]. There, her Honour noted that Halley J had found that the use of the trade mark MOTHERSKY in relation to coffee was not deceptively similar to the registered trade mark MOTHER “which covered beverages”, amongst other things because he found that the MOTHERSKY mark comprises a single invented word, where the word “mother” is completely absorbed within MOTHERSKY and the emphasis and impression conveyed is not on the word “mother”. Her Honour considered that “the same may be said in relation to ZIP when compared to ‘ZIPPAY’, ‘ZIPMONEY’ and ‘ZIPTRADE’.

54 In its judgment in the Energy Beverages appeal, however, the Full Court relevantly observed at [167] that, although “mother” might be a commonly used word, it was not at all descriptive of the relevant goods (non-alcoholic beverages); rather it was inherently distinctive. Their Honours added (at [168]) that it was important that the word “mother” was wholly incorporated within the MOTHERSKY mark because the word “mother” does not lose its identity by the simple addition of the suffix “sky”.

55 Finally, the absence of any evidence of actual confusion, referred to by the primary judge at PJ[222], was of no moment in this case and in any event does not overcome the problems in reasoning already identified. If such evidence is available, it may help the case for the Trade Mark owner, especially when the resemblance is more at the margin, but in a case such as this where the use of the word mark is stark and undeniable, the absence of such evidence does not weaken the outcome of a proper comparative exercise.

56 It follows that ground 1 must succeed. The use of “ZIP” by the respondents in conjunction with other words as set out in items 7 to 25 of Annexure A was deceptively similar, not confined as the primary judge did to items 1 to 6 and 26.

DEFENCES

57 Grounds 2 and 3 concern the defences run by the respondents before the primary judge of honest concurrent use and good faith use of a business name.

58 As to appeal ground 2, concerning the defence of honest concurrent use under s 122(1)(f) and (fa), the primary judge found that if, contrary to her Honour’s primary finding, there had been infringing conduct in relation to the ZIP Formative marks, the respondents would have made good those defences. That is, her Honour found that, to the extent that there had been infringement of the Firstmac Mark at all, the s 122(1)(f) and (fa) defences succeeded, so that there was no infringing conduct at all: PJ[171].

59 As to appeal ground 3, concerning the defence of use of own name in good faith under s 122(1)(a), the primary judge found that in respect of ZIP MONEY for the period 7 September 2015 to 7 December 2017 this additional defence had also been made out, relying upon the findings of honesty for honest concurrent use in relation to ground 2. It follows that the success of both these grounds turns on establishing error in her Honour’s finding that honest concurrent use had been established by the respondents. The parties appeared to approach ground 3 in this way.

Honest concurrent use

60 It is convenient to extract s 122(1)(f) and (fa) and also s 44(3), which is commonly deployed to give content to the hypothetical Trade Mark registrations contemplated by those provisions, and was so deployed in this case:

(a) s 122(1)(f) and (fa) provide:

122 When is a trade mark not infringed?

(1) In spite of section 120, a person does not infringe a registered trade mark when:

…

(f) the court is of the opinion that the person would obtain registration of the trade mark in his or her name if the person were to apply for it; or

(fa) both:

(i) the person uses a trade mark that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the first-mentioned trade mark; and

(ii) the court is of the opinion that the person would obtain registration of the substantially identical or deceptively similar trade mark in his or her name if the person were to apply for it;

…

(b) s 44(3) provides:

44 Identical etc. trade marks

…

(3) If the Registrar in either case is satisfied:

(a) that there has been honest concurrent use of the 2 trade marks; or

(b) that, because of other circumstances, it is proper to do so;

the Registrar may accept the application for the registration of the applicant’s trade mark subject to any conditions or limitations that the Registrar thinks fit to impose. If the applicant’s trade mark has been used only in a particular area, the limitations may include that the use of the trade mark is to be restricted to that particular area.

…

61 Thus, while s 44(3) is dealing with an actual application for registration of a trade mark, it provides a mechanism for giving content to the hypothetical application for registration contemplated by s 122(1)(f) and (fa), ordinarily, and in this case, to be assessed at the first date of the infringing conduct: see Killer Queen, LLC v Taylor [2024] FCAFC 149 (Yates, Burley and Rofe JJ) at [193], adopting the reasoning in Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; 259 FCR 514 (Nicholas, Yates and Beach JJ) at [217]; see also Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 1258 (Yates J) at [631]. Here, the undisputed time of first infringement is November 2013, being the date of first use by the respondents.

62 The cornerstone of the primary judge’s reasoning in upholding the honest concurrent use defence was her finding that the respondents’ adoption of the ZIP and ZIP MONEY marks, which took place before August 2013 when the respondents applied to register those marks, and therefore before they became aware of the Firstmac Mark, was both honest and concurrent, having followed extensive internet searches which had not revealed the use of the Firstmac Mark. Her Honour attached determinative weight to those internet searches, having regard to the limited challenge in cross-examination to the sufficiency of those searches. Her Honour placed little weight on the absence of any search of the Register or on the adverse examination reports from IP Australia which Zipmoney received in October 2013, the month before they proceeded to use the ZIP and ZIP MONEY marks.

63 The honesty required to be established by the respondents for the defences to apply was not merely an absence of dishonesty, but the presence, objectively ascertained, of honesty: see, by analogy with good faith, Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budějovický Budvar, Národní Podnik [2002] FCA 390; 56 IPR 182 (Allsop J) at [217]-[218]; see also Flexopack S.A. Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; 118 IPR 239 (Beach J) at [110]-[111], [118]. An absence of sufficient care and diligence can be sufficient to find the evidence relied upon is inadequate to establish either honesty or good faith: Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; 251 FCR 379 (Greenwood, Jagot and Beach JJ) at [103], expressly applying Flexopack reasoning. There, the Full Court relevantly held that the primary judge was “correct to reject the contention of honest concurrent use given the unchallenged finding that there had been a ‘lack of diligence and reasonable care in carrying out adequate searches before the marks were adopted for use by Insight Radiology’ (at [125]), based on the reasoning in Flexopack”. The respondents did not submit that the Full Court was plainly wrong in this respect.

64 With the above in mind, there are a number of errors in the primary judge’s reasoning.

65 First, it was not for Firstmac to show that the respondents’ internet searches were inadequate. The onus was on the respondents to establish that using the unregistered trade marks “ZIP” and “ZIP MONEY” on the basis of its internet searches alone was sufficient in all the circumstances to establish honesty for the purpose of honest concurrent use. In our respectful opinion that onus was not discharged.

66 In August 2013, prior to the relevant use by the respondents of “ZIP” or “ZIP MONEY” in November 2013, Zipmoney Payments (using its then name, Zipmoney Pty Ltd) applied to register “ZIP” and “ZIP MONEY” as Trade Marks. In October 2013, Zipmoney received adverse reports refusing each application. Each adverse report not only included details of the relevant existing registered Trade Marks (ZIP and ZIPFUND respectively), but expressly said that each proposed trade mark was identical to, or closely resembled, the existing registered Trade Mark, with an earlier priority date. Those adverse reports each stated (with only slight variation in wording):

• Your trade mark closely resembles the earlier trade mark because the prominent and memorable feature of your trade mark is the word ZIP and the earlier trade mark is for the word ZIP.

AND

• The services are similar ....

…

PLEASE NOTE: I have taken into account any differences between this trade mark and your trade mark. I consider, however, that confusion between them is still likely to occur.

And then under the section titled “HOW TO SUPPLY EVIDENCE OF HONEST CONCURRENT USE…” which dealt with s 44 applications, each report said:

HONEST CONCURRENT USE: The evidence must show that your trade mark was chosen honestly and was then used for a significant time concurrently with any conflicting trade mark.

67 Knowledge of the existence of an earlier registered trade mark is not necessarily fatal to a finding of honesty, but a finding of knowledge will ordinarily weigh strongly against a finding of honesty: R Burrell and M Handler, Trade Mark Law in Australia, 3rd ed., LexisNexis Australia, 2024 (Burrell and Handler), [8.9], citing Flexopack at [130]–[140] and [177] and Henley Arch Pty Ltd v Henley Constructions Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1369; 163 IPR 1 at [699]-[703] (Anderson J).

68 The primary judge inferred that Mr Diamond of the respondents had read the adverse reports, a conclusion that is not challenged. PJ[257] But even if that inference had not been drawn or the inference was directed to a later point in time (her Honour’s reasons do not include a finding about when he read them), Mr Diamond, and through him the respondents, knew that registration had been applied for and refused, and were fixed with the means of knowing why registration had been so refused. It would simply be untenable for a party relying upon the defence to infringement of honest concurrent use to rely upon a failure to consider why such a material event as refusal of registration had taken place as a virtue rather than a vice.

69 In any case, the primary judge had earlier, at PJ[84], referred to evidence from Mr Gray, who was the respondents’ chief operating officer and a director of both respondents, that he collected the 2013 adverse reports from a post office box and that “while he has no recollection of reading them in detail, he does recall understanding from them that the 2013 trade mark applications had not been accepted for registration”. Her Honour observed that:

He understood that this was a potentially important matter for the business, and that the reason why the application had been unsuccessful was because there was another trade mark that was close to the one applied for …

70 Having applied for registration and being aware that it had been refused, it can readily be inferred that the respondents were aware of the likelihood that there was a material impediment to the legitimate use of the respondents’ marks: see, by analogy, Pereira v Director of Public Prosecutions [1988] HCA 57; 82 ALR 217 at 219-220 (Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ); see also Kural v The Queen [1987] HCA 16; 162 CLR 502 at 505 (Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ); Saad v The Queen [1987] HCA 14; 70 ALR 667 at 669 (Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ).

71 The adverse reports also advised of the options available to overcome the problems with the respondents’ application, including identifying the sorts of evidence required, and pointed out the difficulties in successfully doing so (an extension of time to make such an application was sought and granted, but never acted upon). Having received the adverse reports, the respondents were squarely on notice of the registered priority marks, including the Firstmac Mark, and they were also aware that IP Australia considered that their marks so nearly resembled the earlier registered marks such that using their marks was likely to cause confusion. Due to concerns with other business matters, the respondents chose not to engage with the adverse reports or their findings, including by not seeking legal advice which might have assisted in proving honesty (see the reasoning in relation to good faith by Beach J in Flexopack at [112]). In those circumstances, it was not to the point that a more thorough exploration in cross-examination of the process of conducting internet searches was possible; the cases in which internet searches or other steps had been challenged to a greater extent relied upon by the respondents and addressed by the primary judge were not reasonably capable of being determinative on their own.

72 It follows that the primary judge’s reliance on the extent of the cross-examination on the internet searches was misconceived insofar as it contributed to a finding that the defence of honest concurrent use had been established: PJ[246]. The fact of conducting those searches was not sufficiently material to the defence to lend any real support to the honesty of the use that the respondents relied upon. It did not address the fact that before the first use of their marks the respondents were fixed with knowledge of the Firstmac Mark as a barrier to registration. It follows that the respondents were unable to establish honesty in relation to the use of later variations of their marks, all of which incorporated the Firstmac Mark.

73 This conclusion is not intended to provide any incentive not to apply for a trade mark to be registered. Failing to apply for the Trade Marks, and hence not receiving the adverse reports, which would be a failure to engage with the Register at all, would not have been any better. As mentioned above, the respondents had the onus to prove the defence, and hence to prove honesty. In circumstances such as these, one would expect an honest trader to do more than the respondents did.

74 Second, it is apparent from the primary judge’s focus on honesty at the time of the decision to adopt the marks of “ZIP” and “ZIP MONEY” ahead of their use, which took place by June 2013, and her finding that no subsequent events were sufficient to infect or displace that conclusion of honesty, that her Honour asked the wrong ultimate question, or applied the wrong test, when it came to honest concurrent use. That is not because prior adoption was an irrelevant contextual circumstance. Nor is it because subsequent events may not also have had contextual relevancy, including the internet searches that were carried out in early 2013. Rather it is because the question of whether there is honest concurrent use is to be assessed as at the date that the first infringing conduct, being use, took place: Anchorage Capital at [217], in the context of [209]-[216]. Her Honour referred to the principle and to the relevant paragraphs in Anchorage Capital at PJ[236] but did not apply them.

75 As the Full Court said in Anchorage Capital at [217], “if the court is not satisfied that the respondent would obtain registration of the relevant trade mark with effect from that date, then the defence fails”. If honest concurrent use cannot be established as at the time of first use, a prior or subsequent state of affairs could not ordinarily assist, and did not do so in the present case. By the first instance of infringing conduct, there was an objective lack of entitlement to use the unregistered marks, with the respondents by then having been given express written notice of that state of affairs. This, too, undermines the primary judge’s finding of honesty.

76 The parties made submissions on appeal as to the correct time for assessment of honesty for the purpose of the honest concurrent use defence. Having found that honesty was not established, it is not strictly necessary to determine whether it would be possible to establish, in any circumstances, honest concurrent use where the first infringement is the first use, due to an inability to establish concurrent use. It is likely that an inability to establish any concurrency of use would also have been fatal to any attempts to establish the defence, at least for the respondents’ use of the “ZIP” mark simpliciter: see Killer Queen, LLC v Taylor [2024] FCAFC 149 at [215]-[216]. However, there is some complexity arising out of the subsequent uses of variations of the mark by the respondents, for which the concurrency issue was not as clear-cut as the honesty issue. The failure to prove honesty at first use infects the findings in relation to subsequent uses as well.

77 Third, the primary judge erred in discounting the significance of the respondents’ knowledge of the prior registration of the Firstmac Mark. In this respect, her Honour’s analysis focused on statements made in Re Alex Pirie & Sons Ltd’s Trademark Application (1933) 50 RPC 147 at 159 (as cited by Nicholas J in Dunlop Aircraft Tyres Ltd v Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company [2018] FCA 1014; 262 FCR 76 at [266]) and McCormick & Company Inc v McCormick [2000] FCA 1335; 51 IPR 102 (Kenny J) at [30] and [32]. As the following discussion demonstrates, the facts of each of those cases is materially different from the facts of the present case, calling for caution in the application of the principles upon which the respondents relied.

78 Alex Pirie was an actual registration case, rather than a hypothetical registration case of the kind created by the use of s 44(3) to address the question of registrability for the purposes of s 122(1)(f) or (fa). Registration was allowed by the Registrar, overturned by a single judge, and restored by the Court of Appeal, with that restoration being upheld by the House of Lords. There had been a substantial period of concurrent use of a similar product name by companies in the USA (being registered) and in the UK (seeking registration). The presence of undoubted honesty was not in issue, giving rise to the seminal statement by Lord Tomlin that “[k]nowledge of registration may be important where the honesty of the user of the mark sought to be registered is impugned, but … once the honesty of the user has been established the fact of knowledge loses much of its significance …”. Consequently, Alex Pirie is of no assistance in the present case.

79 In McCormick, the delegate found the respective marks had co-existed in the market for a long time and there was no suggestion of any improper motive in the small-scale individual trader who was the respondent seeking registration. The case was not concerned with the hypothetical situation in s 122(1)(f) or (fa). Registration was allowed in all the circumstances, but confined to the home State of Queensland where the respondent’s mark was used, with adverse findings as to conduct being rejected. Again, the facts in that case limit the applicability of the principles stated.

80 Dunlop was again an actual registration case, in which there had been a long period of prior use under a legal and factual regime which had ceased to apply, and honesty overtly was not in issue, such that there was a parallel to Alex Pirie, which was applied in the same way. By contrast, here the respondents were on notice of the Firstmac Mark before their use of the marks commenced, were on notice that this was a problem because their registration application was rejected, and they had the benefit of the views of IP Australia about how the problem might be addressed, including how they might go about proving honest concurrent use. Further, once Firstmac became aware of the respondents’ BNPL service, as the primary judge found, it gave a clear signal that it intended to “preserve and defend its rights”, which would act to “dispel any assumption that [the respondents] may have had that they could continue to conduct their business based on the state of affairs that had prevailed since 2013”: PJ[295].

81 Firstmac correctly draws a closer parallel with In Re Parkington & Co Ltd’s Application (1946) 63 RPC 171, which also described and thereby distinguished Alex Pirie (see Parkington at 183). Although not on all fours with this case, in Parkington at 183 Romer J said:

The applicants in Pirie’s case had a mere knowledge little more than subconscious, one gathers from the report, of the opponents’ mark when they started to use their own and that knowledge had nothing to do with the creation of their mark in its inception. Parkingtons not only knew in the present case of Robinsons mark; they knew that Robinsons were actively and jealously preserving that mark and the full monopoly which its registration gave them. Parkingtons must further have known, and I am sure they did know, that Robinsons, in furtherance of what they believed to be their own interests, would (in the absence at all events of stringent conditions) never have permitted the use, far less the registration, of a mark so similar to their own that, in the absence of the most rigid safeguards, confusion. and deception would almost certainly result. In knowledge of all this Parkingtons secretly adopted their mark and secretly put it to commercial use. I should be sorry for it to be thought that such conduct is, in the view of this Court, commercially, honest. I am abundantly clear that it is not, and that traders who obtain the use of a name by hoodwinking those who would have interfered had they known the truth, cannot some years later come to the Court and found a claim for relief .on the footing of honest concurrent user. Perhaps, however, it is sufficient for me to say in brief that the onus is on the Applicants to establish their case in this as in other respects and that in my judgment they have signally failed to discharge it.

82 There is a material distinction between it being difficult to displace a taint attaching to the commencement of concurrent use, and initial honest conduct prior to use not necessarily being beyond impeachment by the circumstances prevailing at the relevant time of first infringing use, especially when new information comes to hand in the intervening period. Again, in the present case, application of the correct approach tells convincingly against the availability of a conclusion of honesty in the relevant sense.

83 Fourth, Firstmac’s case was not one of positively establishing dishonesty, but rather resisting the respondents’ attempts to discharge their onus of positively proving all the features of honest concurrent use as at the relevant time of first infringement of the Firstmac Mark. That is, contrary to PJ[259]-[260], the stance that Firstmac took was to challenge the establishment of honest concurrent use, rather than seeking to establish active dishonesty. Additionally, in relation to subsequent applications for registration of later versions of the respondents’ marks no separate attempt was made to meet the necessary test, and for those marks the circumstances did not improve as to honesty.

84 Firstmac’s approach accords with the history of the development of the defence of honest concurrent use, as described by Dawson and Toohey JJ in New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-Operative Co Ltd [1990] HCA 60; 171 CLR 363 at 405-407; see also Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 at [51]-[52]. That reasoning includes the notion that something more than mere deception or confusion was needed to disentitle a Trade Mark to protection. The proposition advanced by Firstmac is that what is required for honest concurrent use is not just use that is honest, but “the legitimate acquisition of goodwill through trade over a period of time”, consistently with what the tort of passing off is intended to protect and therefore “of sufficient length, volume and scope, geographically or otherwise, such as to found valuable goodwill”, “honestly acquired”. The evident point of this argument is to point out that the respondents did not fall within the category of subsequent user that historically ought to be able to dilute, let alone displace, the protections afforded to a registered owner and user of a Trade Mark. The necessary evaluative inquiry is objective, but may be informed by subjective considerations.

85 Having found that there was honest concurrent use, the primary judge proceeded to consider “the other factors that inform the exercise of the discretion under s 44(3)”. The factors that her Honour identified were “relative inconvenience” and the absence of evidence of confusion.