Federal Court of Australia

Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 12

ORDERS

CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD ACN 000 095 607 Appellant | ||

AND: | LAVAZZA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 605 275 107 First Respondent LAVAZZA AUSTRALIA OCS PTY LTD ACN 626 604 555 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal, to be assessed if not agreed.

3. Order 1 made by the primary judge on 17 November 2023 is stayed:

(a) for a period of 28 days from the date of these orders; or

(b) if any application for special leave to appeal is filed within the time specified in para (a), until the determination of such application or any appeal if special leave to appeal is granted.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 600 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | LAVAZZA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 605 275 107 First Applicant LAVAZZA AUSTRALIA OCS PTY LTD ACN 626 604 555 Second Applicant | |

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD ACN 000 095 607 Respondent | |

order made by: | NICHOLAS, JACKSON AND ROFE JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 FEBRUARY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The application for leave to appeal be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the respondent’s costs of the application, to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 This is an appeal from orders made on 17 November 2023 cancelling two trade mark registrations in the name of the appellant (“Cantarella”) pursuant to s 88(1)(a) and s 58 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (“the Act”), and dismissing its application for relief for infringement of those marks. The respondents to the proceeding before the primary judge and to the appeal are Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (“Lavazza Australia”) and Lavazza Australia OCS Pty Ltd (“Lavazza OCS”) (together “Lavazza”). The primary judge’s reasons for judgment (“J”) are found at Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 1258.

2 The trade marks in suit are Australian Trade Mark No. 829098 (“the 098 mark”) and Australian Trade Mark No. 1583290 (“the 290 mark”), each of which is for the word ORO (“the ORO trade mark”) registered in class 30 for “coffee; beverages made with a base of coffee, espresso; ready-to-drink coffee; coffee based beverages”. The priority dates of the 098 mark and the 290 mark are 24 March 2000 and 30 September 2013 respectively. There is an unchallenged finding that Cantarella first used the ORO trade mark in Australia in relation to coffee on 20 August 1996.

3 At trial Lavazza accepted that it had supplied and advertised coffee in packaging bearing the word ORO, but contended that the 098 mark and the 290 mark were wrongly registered and sought to have the trade mark registrations cancelled. Lavazza also denied that it had used the word ORO as a trade mark. It also raised various statutory defences to infringement under ss 122 and 124 of the Act.

4 Cantarella challenges various findings made by the primary judge concerning what his Honour held to be prior third-party use of the ORO trade mark in Australia before the date of Cantarella’s first use. In particular, Cantarella says that his Honour erred in finding that the ORO trade mark had been used in Australia prior to that date by Caffè Molinari SpA (“Molinari”) (“Ground 1”) and that his Honour should also have found that any such use, if it occurred, was not trade mark use (“Ground 2”).

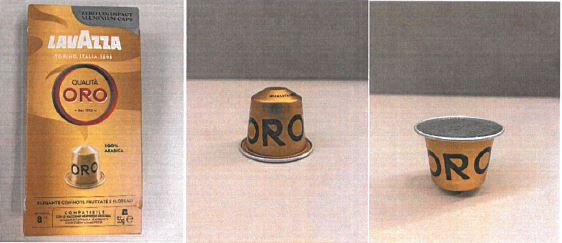

5 Other matters the subject of Cantarella’s notice of appeal include a challenge to the primary judge’s finding that ownership of the ORO trade mark the subject of the prior use findings had not been abandoned by Molinari by the priority date of the 098 mark or, alternatively, the priority date of the 290 mark (“Ground 3”). Cantarella also says that in the alternative to Grounds 1 – 3, this Court should conclude that the primary judge erred in failing to find that Cantarella was a “concurrent owner” of the ORO trade mark (“Ground 4”). Cantarella says that the primary judge erred in finding that the registrations for the 098 mark and the 290 mark were vulnerable to removal, and that each registration was and remains valid. Alternatively, Cantarella says the primary judge erred in failing to exercise the discretion not to cancel the trade mark registrations under s 88(1) of the Act (“Ground 5”).

6 Lavazza has filed an amended notice of contention and cross-appeal. In circumstances where it does not seek to disturb the primary judge’s orders, the reference to cross-appeal is a misnomer. In essence, Lavazza seeks to uphold the primary judge’s findings on a number of grounds that were rejected by the primary judge. First, Lavazza says that the primary judge erred in holding that Lavazza’s use of the ORO trade mark was trade mark use. Secondly, Lavazza says that the primary judge erred in rejecting its defence to the infringement case based on s 122(1)(b)(i) of the Act. Thirdly, Lavazza says that the primary judge erred in holding that the ORO trade mark was, at the date of its registration, distinctive within the meaning of s 41 of the Act. Finally, Lavazza contends that the primary judge erred in holding that various other alleged prior uses of the ORO trade mark on which it relied (in support of its argument that Cantarella was not the owner of the ORO trade mark) did not involve trade mark use in relation to the registered goods.

7 The primary judge ordered that Cantarella pay 50% of Lavazza’s costs of and relating to the proceeding on a party/party basis: Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Lavazza Australia Pty Ltd (No 4) [2024] FCA 419 (“J2”). Lavazza has filed an application for leave to appeal the costs order made by his Honour.

8 For reasons that follow, Cantarella’s appeal against the primary judge’s orders of 17 November 2023 and Lavazza’s application for leave to appeal his Honour’s costs orders should be dismissed.

THE MODENA PROCEEDING

9 Before considering Cantarella’s grounds of appeal, it is necessary to refer to an earlier proceeding to which Cantarella was a party in relation the 098 mark, which was ultimately determined by the High Court in Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd (2014) 254 CLR 337 (“Modena”). It was common ground in the Modena proceeding (and before the primary judge in this case) that “oro” is an Italian word that means “gold”. Modena Trading Pty Ltd has been Molinari’s exclusive distributor in Australia since around 2009.

10 By majority (French CJ, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ, Gageler J dissenting) the High Court allowed Cantarella’s appeal in Modena from a judgment of the Full Court of the Federal Court (Mansfield, Jacobson and Gilmour JJ) cancelling (inter alia) the 098 mark registration, on the ground that it was not capable of distinguishing the trade mark applicant’s goods from those of other persons contrary to the requirements of s 41 of the Act: Modena Trading Pty Ltd v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (2013) 215 FCR 16. The question before the High Court in Modena, which it decided in Cantarella’s favour, was whether the ORO trade mark was “inherently adapted to distinguish” Cantarella’s goods within the meaning of s 41(3) of the Act. As Lavazza noted in its submissions in the present case, there was no challenge to the validity of the ORO trade mark in Modena based on s 58 of the Act.

11 There are two matters of immediate significance arising out of the Modena proceeding. First, there is the High Court’s finding that the ORO trade mark was inherently distinctive when used in relation to the registered goods. Lavazza (which was not a party to that proceeding) submitted to the primary judge that Modena should not be followed. That submission was rejected by the primary judge. Before this Court Lavazza contended that the primary judge should not have followed Modena and should instead have found that the ORO trade mark was not inherently distinctive when used in relation to coffee. The submission was made but not developed in this Court on the express basis that, if necessary, Lavazza would seek to argue in any subsequent appeal to the High Court that Modena was wrongly decided.

12 The Modena proceeding also provides historical context to some evidence relevant to Molinari’s prior use of the ORO trade mark in Australia. The evidence before the primary judge included a copy of an affidavit made by Guiseppe Molinari on 13 September 2011 which was filed and read in the Modena proceeding (“the Molinari affidavit”). In his affidavit Mr Molinari indicates that he is a director and the general manager of Molinari and authorised to make the affidavit on its behalf. Mr Molinari states that Molinari was formed in 1964 and that it has produced various coffee products including the Caffè Molinari Oro blend continuously since 1965. The Molinari affidavit (redacted to take account of material rejected or not read) was exhibited to an affidavit read by Cantarella at the trial before the primary judge.

13 Copies of invoices exhibited to the Molinari affidavit were exhibited to a separate affidavit read by Cantarella at the trial. Those include copies of invoices issued by Molinari to CMS Coffee Machine Services Pty Ltd (“CMS”) and to Saeco Australia Pty Ltd (“Saeco”). The first of those invoices is dated 18 September 1996 and addressed to Saeco. In a section of the Molinari affidavit headed “Molinari in Australia” Mr Molinari states that “Molinari began exporting products to Australia in or about July 1996” and that CMS (formerly known as Saeco) “distributed Molinari products in Australia in the period July 1996 to March 2001”. The reference by Mr Molinari to CMS “formerly known as Saeco” appears to be an error. There is an unchallenged finding by the primary judge that in 2002 CMS changed its corporate name from CMS to Saeco. A company search in evidence shows that the change of name took effect on 3 January 2002.

GROUND 1

14 Against that background we now turn to the first ground of appeal. Under Ground 1, Cantarella challenges the primary judge’s finding that Molinari shipped coffee beans in the Caffè Molinari Oro 3kg packaging, identified as Product Code 6093, to CMS in Australia on 18 September 1995, 17 October 1995 and 26 March 1996 (“the disputed shipments”), which were received at CMS’s warehouse at 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg, Victoria, approximately four to seven weeks after the invoice date, and which were displayed for sale in Australia.

15 The primary judge’s consideration of this issue at J [117] – [208] focuses on the evidence of four witnesses called by Lavazza, Ms Maurizia Baraccani, Mr Fabrizio Mengoli, Mr Giorgio Ubertini and Ms Esther Toledano, together with relevant documentary evidence including the Molinari affidavit, an ASIC search in respect of CMS, and correspondence between Mr Mengoli and Mr Ubertini. The evidence of the four witnesses was central to Lavazza’s case under s 58 based on Molinari’s prior use of the ORO trade mark and, in particular, the disputed shipments.

16 The primary judge found at J [119] that in Molinari’s sales records CMS was given the client code 110103453 (‘453) and Saeco was given the client code 110103878 (‘878). Consistent with the primary judge’s finding, invoices exhibited to the first affidavit of Mr Mengoli include one addressed to CMS dated 24 July 1996 which bears the ‘453 client code, and another addressed to Saeco dated 15 October 1996 which bears the ‘878 client code. However, the invoice to Saeco predates the 2002 change in corporate name by more than five years. This and other discrepancies in the invoices were not the subject of any attention in the parties’ submissions in this Court.

Ms Baraccani

17 Ms Baraccani is the head of Molinari’s Data Processing Centre. She commenced working for Molinari in 1994 and took up her current position in 1997. Between 1994 and 1997 she worked as assistant to the head of Molinari’s Data Processing Centre. According to Ms Baraccani’s evidence, as summarised by the primary judge, before 1996 information relating to all Molinari coffee sales, both in Italy and abroad, was stored on a database managed by a computer system called “Olimpix”. Olimpix was used by Molinari to issue invoices to customers and record sales data. The invoices were printed and sent to customers by post or facsimile transmission. Hard copies of the invoices were kept by Molinari in its archives. According to Ms Baraccani’s evidence, much of Molinari’s paper records have since been destroyed.

18 In March 1996, Ms Baraccani participated in the migration of data from the old Olimpix system to a new system called “Kronos”. According to Ms Baraccani’s evidence, which the primary judge accepted, there were limits to the type of information that was stored in the Olimpix database and, as a result, only some of the information relating to Molinari sales and products in existence before June 1996 was migrated to the Kronos system. Ms Baraccani also gave evidence, accepted by the primary judge, that while the Kronos system can reproduce sales invoices from 1996 onwards, it cannot do this for sales occurring before 1996.

19 According to Ms Baraccani’s evidence, on around 21 April 2021, Mr Mengoli, the Sales, Marketing and Export Manager of Molinari, asked her to provide data stored in the Molinari computer system relating to sales to four client codes including ‘453 and ‘878. The primary judge accepted at J [118] that Ms Baraccani “interrogated Molinari’s computer records and prepared two spreadsheets of sales data concerning Molinari coffee exported to Australia in the period 1995 to 2003”.

20 Ms Baraccani exhibited to her affidavit a copy of the data in the form of two Excel spreadsheets which she downloaded from the Kronos system in respect of sales in the period 1995 to 2003. According to her evidence, the first 13 lines of the first Excel spreadsheet contain information relating to sales of Molinari coffee products to the customer identified by ‘453 client code, which have been transferred from the Olimpix system to the Kronos system. Ms Baraccani stated in her affidavit that the two Excel spreadsheets “are exact records of information stored in the Molinari Kronos system relating to sales to customers identified by customer codes” including the client codes ‘453 and ‘878.

21 Senior Counsel for Cantarella, Mr Bannon SC, referred us to parts of Ms Baraccani’s cross-examination in which she accepted that she had no role in the issuing of invoices to customers or the recording of sales data. In its written submissions, Cantarella contended that Ms Baraccani’s Excel spreadsheets should not have been received into evidence because they did not satisfy the requirements of the hearsay exception in s 69 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (“Evidence Act”) or, alternatively, that they should have been excluded under s 135 or given little or no weight. In his oral submissions, Mr Bannon focused not on the admissibility of the spreadsheets, but on whether they constituted evidence capable of supporting the primary judge’s findings concerning the disputed shipments. We will consider those and related submissions later in these reasons.

Mr Mengoli

22 Mr Mengoli is the Sales, Marketing and Export Manager of Molinari. He commenced employment with Molinari as an Export Manager on 18 March 1996. He was promoted to his current position in 2008. Mr Mengoli gave evidence that when he joined Molinari as Export Manager in March 1996, Molinari already exported coffee, including what he referred to as Caffè Molinari Oro, to Australia.

23 According to Mr Mengoli’s evidence, the Kronos system was in the process of being installed when he started with Molinari, and it was used throughout the business from June 1996 onwards. Although some of the sales details of the invoices prior to June 1996 were kept in Molinari’s electronic records on the Kronos system, the underlying hard copy invoices from that time were not retained by the business.

24 Mr Mengoli went on to interpret the first of the spreadsheets created by Ms Baraccani making reference to certain of the product codes appearing therein including, in particular, the product code 6093 for Caffè Molinari Oro 3kg and the product code 6091 for Caffè Molinari Oro 1kg.

25 Mr Mengoli also stated that he caused to be retrieved from the Kronos system invoices issued by Molinari for Caffè Molinari Oro dated between 24 July 1996 and 16 April 2003. As to the invoices dated 18 September and 17 October 1995, and 26 March 1996, for the disputed shipments, his evidence was that Molinari no longer had access to those invoices.

26 Mr Mengoli produced a copy of a letter signed by him from Molinari to CMS dated 23 July 1996 addressed to “Mr Ubaldini”, which the primary judge accepted was a mistaken reference to Mr Ubertini at CMS. In the letter (which is in Italian, but has been translated), Mr Mengoli thanked Mr Ubertini for his order, referred to a telephone call on 18 June 1996, and discussed the development of the Australian market for Molinari coffee products.

27 In his third affidavit, Mr Mengoli stated that Molinari’s shipments to Australia have always been sent by sea and that, depending on the shipping service used, these generally take between 25 to 50 days to arrive in Australia. To the best of his recollection, that period of time was the same in the mid-1990s. He also stated that “[i]nvoices are dated to align with the day the products leave Molinari’s warehouse”. Mr Mengoli also commented upon the Molinari affidavit stating that Molinari’s computing systems were changed in June 1996, and that this may explain why Mr Molinari did not provide evidence of exports to Australia prior to July 1996.

28 Mr Mengoli was cross-examined at some length. His evidence was given with the assistance of an interpreter. The cross-examination demonstrated that evidence given by him concerning the availability of sales documents for the period before June 1996 and the data migration was not based on his personal knowledge, but what he had been told by Ms Baraccani. It also established that Mr Mengoli had some involvement in the compilation of the information that was included in the Molinari affidavit. He also accepted that he was unable to say which department had responsibility for keeping Molinari’s physical records in 2011 when the Molinari affidavit was made.

29 Mr Mengoli said that he did not read the Molinari affidavit, but he provided some documentation to Mr Molinari for the preparation of the affidavit. His cross-examination included the following exchange:

MR BANNON: And you understood that Mr Giuseppe Molinari was relying on you for information for the purpose of the affidavit as to when Caffè Molinari first began exporting products to Australia?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes. He was relying on me just as much as he was relying on a lot of other people, maybe about 10 people, including his own father, the IT specialist, the secretary looking after the invoices. And so I was … one of them.

MR BANNON: And you looked at the documents which were gathered together for the purposes of identifying when sales were first made to Australia?

THE INTERPRETER: I honestly looked at documents starting from the time I was there.

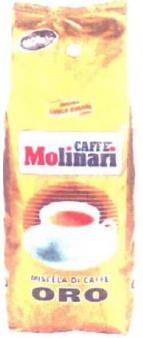

30 The primary judge accepted (at J [125]) that at the time Mr Mengoli commenced working at Molinari in March 1996, Caffè Molinari Oro coffee was packaged as follows:

31 The primary judge also accepted Mr Mengoli’s evidence that, based on an investigation conducted by him and others in his team, there was nothing to suggest that the products were packaged any differently in 1995. His Honour made a specific finding in relation to a sample of the Caffè Molinari Oro 3kg product packaged on 25 September 2007 (“Sample Product”) that was in evidence, which he was satisfied exemplified the packaging used for that product in 1995.

32 The primary judge found Mr Mengoli’s evidence to be credible and reliable at J [188].

Mr Ubertini

33 Mr Ubertini established CMS with his business partners in 1993. According to Mr Ubertini’s affidavit evidence, CMS operated from various premises in Melbourne including, at first, premises situated at 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg. His business partners were Mr Antonio Petrolito, Mr Vincenzo Nespeca and Mr Angelo Augello. Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello were also coffee roasters and they had their own business distributing coffee under the name “Monte Coffee”. Mr Ubertini said in his affidavit that, in the early years of the CMS business, CMS’s premises were next to the Monte Coffee warehouse, which was located at 31 Acheson Place. During that period, CMS provided promotional packets of Monte Coffee to customers who purchased coffee machines from CMS. In mid-1995 Mr Ubertini and Mr Petrolito bought Mr Nespeca’s and Mr Augello’s interest in CMS.

34 According to Mr Ubertini’s affidavit evidence, when Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello were bought out, CMS had an opportunity to offer other brands of coffee to its customers. Mr Ubertini said while he was in in Italy on a buying trip and to visit his parents in his hometown of Modena in around September of 1995, he arranged to meet with Mr Guiseppe Molinari for the purpose of securing supplies of coffee to replace the Monte Coffee that CMS had previously supplied.

35 In his affidavit Mr Ubertini said he did not remember the precise date of his meeting with Mr Molinari, but he believed it was in around September 1995 because it was not long after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello left CMS. He said it also coincided with the HOST trade show held every two years in Milan that he regularly attended. In the years when he attended the HOST trade show, Mr Ubertini would travel to Italy in late August or early September and return after the trade show concluded in October.

36 According to Mr Ubertini’s affidavit evidence, at his first meeting with Mr Molinari, he placed an initial order with Molinari for Molinari Oro coffee to import into Australia. He also said that he was at this time purchasing many products from Italy and that these generally arrived by sea between three to six weeks after orders were placed. He said that he could not recall the precise date when the first shipment of Molinari Oro coffee arrived in Australia, but he did recall that it was shortly after he returned to Australia from the HOST trade show at the end of October 1995.

37 In his affidavit Mr Ubertini said that even though Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello were no longer involved in the CMS business, they were still operating from the premises adjacent to 1/33 Acheson Place. He said that he was careful to cover the first pallet of Molinari Oro coffee when it arrived because he did not want to upset them. Mr Ubertini also said that while he could not recall what was in the first shipment from Molinari, he remembered that Molinari supplied CMS with its Molinari Oro blend of coffee, mainly in 1kg bags. He also remembered that at the start of CMS’s relationship with Molinari, CMS imported some larger 3kg bags of Molinari Oro. He said that from October 1995 onwards, the staff and directors of CMS used Molinari Oro coffee to make coffee for themselves and customers to promote Molinari Oro coffee.

38 Mr Ubertini was also cross-examined at some length. It is apparent from the transcript that Mr Ubertini was at times garrulous and non-responsive in his answers. Of course, it does not follow that his evidence was untruthful or unreliable. Mr Ubertini was clear in his answers that the first shipments from Molinari arrived at the 1/33 Acheson Place address before the end of 1995. It was put to him that the shipments did not arrive until after 25 July 1996. He disagreed. It was also put to him that he did not receive anything in 1995 from Molinari. He disagreed and said that he had two shipments from Molinari in 1995. Mr Ubertini also rejected the suggestion put to him that he had not spoken to Mr Molinari about importing coffee before 18 June 1996, though he agreed that he had not spoken to Mr Mengoli before that date. He also agreed that he recalled that the first delivery of Molinari Oro coffee came on a pallet.

39 It was put to Mr Ubertini that CMS did not commence operating from 1/33 Acheson Place until 24 July 1996. In that context he was taken to copies of various documents, including CMS’s Annual Returns for the years ending 30 June 1994 and 30 June 1995. Both documents identify the principal business office as 31 Acheson Place, Coburg. The first of them is signed by Mr Petrolito on 31 December 1994 and the second by Mr Ubertini with no date shown. In his cross-examination Mr Ubertini was also shown the ASIC Extract for CMS/Saeco which also refers to the “start date” of 24 July 1996 for the principal place of business at 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg.

40 The primary judge referred (at J [188]) to some “unsatisfactory aspects of Mr Ubertini’s oral evidence”. Nevertheless, his Honour considered Mr Ubertini to be a truthful witness. His Honour observed at J [166]:

In fairness, I should point out that Mr Ubertini gave his oral evidence by video-link from Italy at a difficult time (late evening/early morning). Mr Ubertini is elderly and giving evidence by this means at this time of the day was likely to have been challenging for him. I make allowance for that possibility in relation to his presentation as a witness. I do not think that Mr Ubertini was intending to be unhelpful. I do not think that he was attempting to evade answering questions. I consider him to be a truthful witness. Nevertheless, based on his presentation in cross-examination, I treat his evidence with circumspection.

41 His Honour went on (at J [188]) to accept Mr Ubertini’s evidence notwithstanding the unsatisfactory aspects to which his Honour referred.

Ms Toledano

42 Ms Toledano (who is Mr Ubertini’s ex-wife) was employed by CMS as a Finance and Administration Manager. In her affidavit she said that CMS first operated from 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg, next door to the Monte Coffee warehouse.

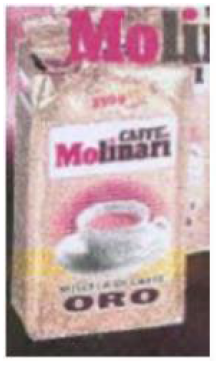

43 Ms Toledano said in her affidavit that she could not recall the exact date CMS began importing coffee from Molinari but that it was not long after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello left CMS. According to her evidence, this meant the date had to be some time after August 1995 and before the end of 1995. She said she remembered shipments of Molinari coffee arriving at CMS’s warehouse at 1/33 Acheson Place. She also said that she recalled receiving 3kg bags of Caffè Molinari Oro coffee in the same packaging as that shown in the photograph reproduced at [30] above. She said in her affidavit:

I specifically recall providing and selling bags of Caffè Molinari Oro coffee to several of these customers when I was alone in CMS’s showroom at 1/33 Acheson Place at the time when I was CMS’s only employee (i.e. from around the end of 1995 but definitely before April/May 1996 when CMS hired an additional employee). I also recall accounting for those early sales of Caffè Molinari Oro in CMS’s computer system during that time.

44 Ms Toledano was cross-examined briefly. As the primary judge recorded at J [179], her affidavit evidence was not directly challenged. As his Honour also noted, Ms Toledano said that CMS was trading at 1/33 Acheson Place before 1996. Her cross-examination included the following exchange:

Were you aware that the company records filed with ASIC indicate that that became the principle [sic] place of business of CMS on 24 July 1996, 1/33?---At Acheson Place?

Yes?---Acheson Place, we were there from ‘93.

… Were you aware that the ASIC records indicate that the principle [sic] place of business of a company did not become Unit 1/33 Acheson Place until 24 July 1996. Were you aware of that?---No, I don’t know what the ASIC records show. I know we were trading there before ‘96.

And I want to suggest to you that the first shipment which was received was received at 1/33 Acheson Place. I think you agreed with that?---Yes.

And that was after 24 July 1996. Do you agree?---It’s possible. I don’t remember the actual arrival date. I just know that we were – before September ‘96, we had already moved premises. Exactly what date that was, I can’t recall, but I just remember being there back in November – back into the office. I had taken two months off, so – yes, I’m not - - -

…

I didn’t mean to interrupt you. Sorry?---Sorry. It’s just that I don’t know the specific dates. Either it was after July or before July. I just know that we did get one before I took maternity leave, which is in September, and we had just moved to the new premises. So yes, I can’t – sorry –I can’t give you a specific date .....

45 In her affidavit Ms Toledano said that CMS hired another employee in around April/May 1996, that her first daughter was born in September of that year, and that CMS moved to new premises at 86 Newlands Road, Reservoir, Victoria, in around August 1997.

46 The primary judge found Ms Toledano to be a credible and reliable witness. His Honour referred to Ms Toledano’s oral evidence and accepted that it raised some doubt as to the reliability of her recollection. However, his Honour said at J [182]:

Ms Toledano’s affidavit gives a more focussed recollection—namely, that CMS commenced ordering Molinari coffee shortly after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello had left the CMS business, and that the first two shipments from Molinari arrived before the end of 1995. Although Ms Toledano’s oral evidence throws some doubt on the reliability of this recollection, I do not take her to have resiled from what she had said in her affidavit. Moreover, her evidence must be considered as a whole and with the other evidence before the Court, which includes Mr Ubertini’s evidence as to his first order on Molinari and the timing of the arrival of that order at 1/33 Acheson Place, and Molinari’s available accounting records, which accord with Mr Ubertini’s evidence on this topic.

47 It is apparent that his Honour accepted Ms Toledano’s evidence that shipments of Molinari coffee arrived at CMS’s 1/33 Acheson Place premises not long after Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello left CMS in around August 1995 (which is when they resigned as directors of CMS) and before the additional employee was hired in April or May 1996.

Consideration

48 Cantarella submitted that the primary judge made basic errors in his approach to fact finding. What these errors were said to be was not altogether clear, but at the core of Cantarella’s submission was the suggestion that his Honour wrongly preferred witnesses’ evidence that was based wholly on their recollections of events that took place many years ago in circumstances where those recollections were said by Cantarella to be inconsistent with, or at least not supported by, documentary evidence including the Molinari affidavit. Cantarella also submitted that there was no reliable evidentiary basis for the primary judge’s finding that the packaging of the Caffè Molinari Oro 3kg product in 1995 was the same as the packaging of the Sample Product packaged in 2007.

49 It was submitted that the primary judge had insufficient regard to the gravity of the allegations made by Lavazza which raised a challenge to the validity of the trade mark registrations that had been on the Register of Trade Marks for “a very long time”. In its written submissions in chief on the notice of appeal, Cantarella contended that this was particularly so where the size, colour, position and prominence of the word ORO, in relation to other packaging elements, was a determinative question in this matter. In support of this particular submission, we were referred to the judgment of the majority (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, and Jagot JJ) in GLJ v Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore (2023) 414 ALR 635 at [57], and of Gleeson J at [167], as well as s 140(2) of the Evidence Act. However, it is apparent from Mr Bannon SC’s oral submissions and Cantarella’s written submissions in reply on the notice of appeal, that this submission was made in respect of the entirety of Ground 1. Mr Bannon submitted that proof of prior use in this case required what he described as “a level of higher satisfaction”.

50 In our view, there can be no suggestion that the primary judge overlooked the fact that Cantarella’s ORO trade mark had been registered for many years, or that he did not appreciate the significance of the findings that Lavazza asked him to make. Referring to the evidence of the Lavazza witnesses, specifically in relation to the computer records tendered through Ms Baraccani and Mr Mengoli, his Honour said at J [190] that he was fully cognisant of the significance of that evidence to Cantarella’s rights of ownership.

51 Cantarella’s attack upon the primary judge’s prior use findings took as its starting point the Molinari affidavit, which was said by Cantarella to show that Molinari did not export any of its products to Australia until in or about July 1996. Cantarella submitted that it was apparent from the Molinari affidavit that the statements made were based on a comprehensive search of both electronic and hard copy records in order to determine the date of the first shipment to CMS, which is identified in the first of the invoices exhibited to the Molinari affidavit and dated 18 September 1996. Further, it was submitted that it should be concluded that the Molinari affidavit was:

… prepared by Molinari’s most senior executive following a comprehensive inspection of Molinari’s extant records and further…if Molinari could have proven first use and therefore ownership of the ORO word mark within the meaning of s 58 of the Act and wholly defend its distributor Modena from an otherwise successful infringement claim, it would have done so.

52 Cantarella’s submissions approach the Molinari affidavit as if it was the only credible or reliable evidence directed to the prior use issue, when there was in fact a substantial amount of other evidence, including evidence of witnesses who were found to be credible and reliable, that was also considered and weighed by the primary judge.

53 It is important at this point to refer to this Court’s role in reviewing factual findings made at trial. One area in which the primary judge’s findings will be treated with considerable deference is where they comprise findings of fact likely to have been affected by impressions about the credibility of witnesses formed after seeing and hearing their evidence: see Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [25] – [29] per Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ. In Lee v Lee (2019) 266 CLR 129, Bell, Gageler, Nettle and Edelman JJ (with whose reasons Kiefel CJ agreed) said at [55]:

A court of appeal is bound to conduct a “real review” of the evidence given at first instance and of the judge’s reasons for judgment to determine whether the trial judge has erred in fact or law. Appellate restraint with respect to interference with a trial judge’s findings unless they are “glaringly improbable” or “contrary to compelling inferences” is as to factual findings which are likely to have been affected by impressions about the credibility and reliability of witnesses formed by the trial judge as a result of seeing and hearing them give their evidence. It includes findings of secondary facts which are based on a combination of these impressions and other inferences from primary facts. Thereafter, “in general an appellate court is in as good a position as the trial judge to decide on the proper inference to be drawn from facts which are undisputed or which, having been disputed, are established by the findings of the trial judge”.

(Footnotes omitted)

54 The critical question at trial was whether CMS imported into Australia Molinari coffee (including, in particular, Caffè Molinari Oro in the 3kg packaging) in 1995 or early 1996. The invoices annexed to the Molinari affidavit indicate that the earliest sale by Molinari to CMS occurred in September 1996. However, Mr Ubertini’s evidence was very clearly to the effect that Molinari coffee (including Caffè Molinari Oro in the 3kg packaging) was imported by CMS into Australia in 1995, after he met with Mr Molinari in Italy in about September 1995 and placed an initial order. At the risk of stating the obvious, the allegation that the first importation occurred in 1995 was a disputed matter the subject of conflicting evidence that the primary judge was required to consider and weigh. That task necessarily involved forming a view as to the credibility of a number of witnesses who gave evidence before the primary judge, including Mr Ubertini. The primary judge’s finding on the critical question should not be disturbed unless it is “glaringly improbable” or “contrary to compelling inferences”.

55 Cantarella’s notice of appeal and submissions relevant to Ground 1 engage in an analysis of the evidence as if this appeal were a new trial, without recognising or allowing for the advantages enjoyed by the trial judge in weighing up the whole of the evidence including the written and oral evidence of Lavazza’s witnesses.

56 Cantarella placed considerable weight before the primary judge and in the appeal on the fact that the ASIC Extract for CMS/Saeco showed that the “start date” for the business address for CMS at 1/33 Acheson Place was 24 July 1996 (Ground 1 particular (ii)). In oral submissions to this Court, reference was also made to the CMS Annual Return for the year ending 30 June 1995, along with the Annual Return for the year ending 30 June 1994.

57 The ASIC Extract contains information derived from the ASIC database which, we would infer, reproduces information contained in (inter alia) the two Annual Returns. The 1994 Annual Return was signed by Mr Petrolito on 31 December 1994 and lodged by the accounting firm, N. Burchill & Co. As previously mentioned, the principal place of business is shown as 31 Acheson Place, Coburg, which was the address for Monte Coffee and immediately adjacent to 33 Acheson Place, Coburg. The 1995 Annual Return was prepared by the same firm of accountants and signed by Mr Ubertini. It continues to show CMS’s principal place of business as 31 Acheson Place, Coburg.

58 Cantarella’s submissions assume that the information in the Annual Returns is necessarily accurate or, at least, that it is more reliable than the evidence of Mr Ubertini and Ms Toledano. Both Mr Ubertini and Ms Toledano were clear in their evidence that CMS operated from 1/33 Acheson Place, Coburg from 1993. Neither witness resiled from that evidence. Acceptance of their evidence necessarily implies that the information in the ASIC Extract and the Annual Returns was incorrect. The possibility that the two addresses were confused by those who prepared the Annual Returns and that their error was then overlooked by those who signed them may well explain the discrepancy. In our view, this inference is readily made when one acknowledges the close business relationship between CMS and Monte Coffee. It was open to the primary judge to accept Mr Ubertini’s and Ms Toledano’s evidence on this topic.

59 Cantarella also relied on the letter from Molinari to CMS dated 23 July 1996, which Cantarella submitted was more consistent with a new business relationship that commenced in mid-1996 rather than one that began the previous year.

60 The 23 July 1996 letter was written by Mr Mengoli, who commenced employment with Molinari in March 1996 as Export Manager. There is nothing in the letter which implies that there was no business relationship between CMS and Molinari before mid-1995, or that the order referred to in the first paragraph of the letter was the first order placed by CMS. The letter of 23 July 1996 is consistent with an attempt by Mr Mengoli (relatively new to his then role) to develop and expand an existing business relationship with CMS. Cantarella’s submission with regard to the 23 July 1996 letter was considered and rejected by the primary judge. Cantarella does not identify any error in the primary judge’s analysis of the letter.

61 In his oral submissions to this Court, Mr Bannon SC indicated that he did not seek to revisit the correctness of the primary judge’s decision to admit Ms Baraccani’s Excel spreadsheets into evidence as a business record. However, he submitted that the Excel spreadsheets were not evidence of any sale or shipment of any product by Molinari to CMS in 1995. He submitted that properly analysed, the Excel spreadsheets, when viewed in light of the Molinari affidavit, and the absence of any witness employed by Molinari with any personal knowledge of relevant events, should have been given no weight by the primary judge.

62 Cantarella was particularly critical of the primary judge’s use of the word “shipments” to describe entries in the Excel spreadsheets. It submitted that the spreadsheet was not evidence of any export, completed transactions, shipment, or delivery. Mr Bannon SC pointed out that the Excel spreadsheets did not include any reference to delivery or payment. He submitted that even though the document referred to invoice dates, invoice numbers and invoice amounts, it was not open to infer that any of those entries related to actual product sales or shipments. Asked whether each of the relevant entries was evidence of a transaction between Molinari and CMS, he submitted that the word was ambiguous in that a transaction may or may not comprise a sale or a shipment of product.

63 Mr Bannon SC was prepared to accept that the entries on the spreadsheets comprised evidence of the generation of invoices. His submission was, in effect, that the primary judge should not have been satisfied that the entries in the Excel spreadsheets (or at least those created before July 1996) were anything other than records of “pro forma” invoices, which were not proven to record actual sales. The submission was developed by reference to evidence given by Mr Mengoli in cross-examination who explained that Molinari will sometimes issue a pro forma invoice for the approval of the customers.

64 Mr Mengoli’s cross-examination included the following:

MR BANNON: … So is this right; the company creates proforma invoices?

THE INTERPRETER: In the last few years, yes, this is how the company operates, but I cannot tell you for sure if that was the case years ago or if, maybe, we just send a fax or something else.

…

MR BANNON: Since the commencement of your time in the company, if an order was received, for example, by the telephone was a pro forma invoice sent to the client for their approval to let them know how much the goods would cost?

THE INTERPRETER: Okay. I’m not sure that we used to call it pro forma invoice or - but we did write when - when we received an order. We did write maybe an invoice or facsimile of an invoice to - to let them know - to send to - to send to the customers.

MR BANNON: And then, if they approved that invoice or facsimile, then the order would be shipped; is that right?

THE INTERPRETER: Yes

MR BANNON: And that type of invoice which you just referred: as far as you were aware, they were included on the computer system from your time in 1996?

THE INTERPRETER: No. I don’t even think that now we keep the proforma invoice in the computer.

MR BANNON: Am I right in saying that the invoice you referred to, the proforma, was created on the Molinari systems from 1996? A computer was used to create these invoices?

THE INTERPRETER: I don’t think so. I cannot be sure, but I - I - I believe that we used a manual system, not the computer.

MR BANNON: Well, do you know how any sort of invoice was generated in Caffè Molinari between 1996 and 2000? And was a computer used in the generation of any invoice? …

THE INTERPRETER: At this moment, this time in the company, I don’t know. I - it’s not my job, and it’s - it’s really not my - my- my job to know it. I don’t know.

…

MR BANNON: Well, is this right: you don’t know how invoices were generated from Caffè Molinari between 1996 and 2000, do you?

THE INTERPRETER: The invoices were generated by the computer - the system in our computer, but I don’t know if the proforma invoice were also generated by the computer or they were just paper, handmade.

MR BANNON: And you don’t know if any proforma invoices generated by - if it was generated by the computer, you don’t know whether the computer retained a copy of it, do you?

THE WITNESS: No.

65 The cross-examination was expressly directed to the use of pro forma invoices in the period between 1996 and 2000. Leaving that aside, Mr Mengoli’s evidence indicates that from time to time pro forma invoices may have been issued as a step along the way to arranging a sale and shipment of product. His evidence therefore gives rise to the possibility that the entries in Ms Baraccani’s Excel spreadsheets for invoices dated 18 September 1995, 17 October 1995 and 26 March 1996 were only entries relating to pro forma invoices which do not represent actual sales or shipments of the specified product.

66 Even if the entries in the Excel spreadsheets do not themselves prove that Molinari shipped products to CMS in 1995 and early 1996, they at least indicate that there were commercial dealings between Molinari and CMS at those times, at which point invoices were issued to CMS. And even if these invoices were “pro forma” invoices that did not record any concluded sale, they at least show that Molinari was offering to supply CMS with the specified product at the specified prices on or about those dates.

67 Cantarella’s submissions concerning Ms Baraccani’s spreadsheet focus on the inconsistency between what it shows and what appears in the Molinari affidavit. However, the primary judge was required to consider Ms Baraccani’s spreadsheet together with other evidence including Mr Ubertini’s evidence of his September 1995 meeting with Mr Molinari in Italy, and evidence from both Mr Ubertini and Ms Toledano of CMS’s receipt of coffee products from Molinari in the latter part of 1995. Having done this, his Honour accepted Mr Ubertini’s evidence that he placed CMS’s initial order with Mr Molinari in around September 1995 and that products the subject of that order and a second order were received by CMS later that year. We have already referred to the matters Cantarella pointed to in order to cast doubt on Mr Ubertini’s evidence, including Mr Mengoli’s letter of 23 July 1996 and the 24 July 1996 “start date” referred to in the ASIC Extract. These matters do not establish that Mr Ubertini’s account of his dealings with Molinari in 1995 was glaringly improbable, or contrary to compelling inferences.

68 Cantarella also relied on what was said to be the improbability of Mr Ubertini placing a second order with Molinari on or about 17 October 1995, before the initial order had been received. Mr Ubertini’s evidence was that products shipped from Italy to Australia generally arrived three to six weeks after an order was placed. However, as recorded above, the primary judge made a finding that shipments to CMS’s warehouse from Molinari were received four to seven weeks after the invoice date. The time between 18 September 1995 and 17 October 1995 is approximately four weeks. If Mr Ubertini’s evidence regarding shipment time is correct, it is highly likely that the first shipment was received after the date that CMS is said to have placed another order. Alternatively, the contents of the first order would only have been present at CMS’s premises for about a week. Going by the shipment time the primary judge adopted, the contents of the first order could have been present at CMS’s premises for, at most, a day or so before the second order was placed. According to Cantarella, these propositions are inconsistent with Mr Ubertini’s evidence that he would not have ordered a second shipment of coffee before he had received the first shipment.

69 The primary judge was satisfied that each of the disputed shipments was shipped on the date of invoice as recorded in the Kronos system, and received approximately four to seven weeks after that date (J [193]). That finding appears to take into account Mr Ubertini’s evidence that the first shipment arrived shortly after Mr Ubertini returned from Italy at the end of October 1995 (rather than the middle of October). It would follow from that finding that the second order was most likely placed before CMS received the first shipment. That may reflect a discrepancy in Mr Ubertini’s evidence. He was adamant that he would not have placed a second order before the first order was fulfilled. Nevertheless, Mr Ubertini was clear in his oral evidence that CMS received two shipments from Molinari in the latter part of 1995. In the context of the rest of the evidence, the primary judge was entitled to accept that testimony despite the discrepancy.

70 We have previously referred to Mr Ubertini’s evidence that he covered the first pallet of Caffè Molinari Oro because he did not want to upset Mr Nespeca and Mr Augello. In its submissions, Cantarella contrasted that evidence with Ms Toledano’s evidence that she recalled displaying the Caffè Molinari Oro in the 1kg and 3kg packaging when CMS was located at 1/33 Acheson Place (recorded at J [178]). According to Ms Toledano’s affidavit evidence:

I recall that during the period when I was CMS’s only employee (before April/May 1996), I often made cups of coffee for walk-in customers using the 1kg and 3kg bags of Caffè Molinari Oro coffee. The bags were displayed next to the coffee machines and grinders we used in the warehouse, for customers to see and purchase.

71 Mr Ubertini’s evidence was not specific as to when or for how long he covered the first pallet. Moreover, Ms Toledano referred to the display of bags of coffee, not a pallet. When asked whether the first pallet to arrive was covered by Mr Ubertini, Ms Toledano said she did not recall. We do not consider that the evidence of Ms Toledano on this topic is necessarily inconsistent with that of Mr Ubertini, or that it should have led the primary judge to reject as improbable Mr Ubertini’s evidence as to when and where the first pallet was delivered.

72 Cantarella dismisses Mr Ubertini’s evidence as glaringly improbable or contrary to compelling inferences drawn from other evidence including the Molinari affidavit. The Molinari affidavit was not uncontested or undisputed evidence. Lavazza’s case was that the Molinari affidavit was wrong in stating that Molinari began exporting Caffè Molinari coffee to Australia in or about July 1996. The primary judge resolved the inconsistency between the Molinari affidavit and Mr Ubertini’s evidence by finding that the Molinari affidavit was mistaken and inaccurate (at J [192]). In our opinion that finding, which depended on impressions formed by his Honour of Mr Ubertini and Ms Toledano as witnesses, was open to the primary judge and was neither glaringly improbable nor contrary to compelling inferences drawn from other evidence.

73 It was faintly suggested in Cantarella’s submissions that an inference should have been drawn by the primary judge against Lavazza because it failed to call Mr Molinari. This is not a point raised in any ground of appeal. Nor were we taken to any submission made to the primary judge by Cantarella on the point. The fact that the primary judge does not refer to any such submission suggests that it was not made. Whatever else might be said about any failure to call Mr Molinari, the point is outside the scope of Cantarella’s appeal.

74 The final issue raised by Cantarella under its first ground of appeal concerns the appearance of the packaging for the 3kg Caffè Molinari Oro product imported by CMS in 1995. As previously mentioned, the primary judge found (at J [127]) that the packaging of the 3kg product when Mr Mengoli commenced working for Molinari in March 1996 was as depicted in the photograph reproduced at [30] above. Cantarella submitted that there was “no reliable evidentiary basis” for that finding. In support of that submission, Cantarella referred to evidence as to the multiple iterations of packaging for Molinari products utilising the word ORO, and the frequency with which Lavazza (i.e. not Molinari) updated and altered the packaging of its coffee products (including the size and prominence of the word ORO) before, during and after the period 1995 to September 2007. Cantarella also submitted that no witness could independently recall the Caffè Molinari 3kg packaging.

75 Mr Mengoli was cross-examined on the form of the 3kg packaging. When it was put to him that he “did not attempt to remember what the packaging might have looked like”, he responded “[i]t’s the other way around. I remember [sic] the images, and I went to look for the documents that had the images as I remembered.” He was not asked any further questions on that or any other topic. There is no substance to the suggestion that Mr Mengoli had no independent recollection of the 3kg packaging.

76 Mr Ubertini and Ms Toledano were both shown the same photograph of the 3kg Caffè Molinari Oro product that was identified by Mr Mengoli, at the time of preparing their affidavits. Both gave evidence that the 3kg product was packaged as depicted in the photograph. Mr Ubertini’s evidence was that he could not recall any changes to the gold packaging between September 1995 and October 2003. Ms Toledano’s evidence was that the packaging was consistent with her memory of the packaging and that she also could not recall any changes to the gold packaging during the period that CMS imported coffee from Caffè Molinari. Neither Mr Ubertini nor Ms Toledano was asked any question relating to the appearance of the 3kg packaging. There is no substance to Cantarella’s submissions on this topic.

77 Ground 1 fails.

GROUND 2

78 The question that arises under ground 2 of the notice of appeal is whether the primary judge erred in holding that the use of the word ORO on the packaging of the 3kg Caffè Molinari Oro product constituted trade mark use of that word. Cantarella submitted that the primary judge should have found that there was no such use.

79 The following photographs of the 3kg product packaging are reproduced from the parties’ written submissions:

80 The primary judge found at J [573] that Molinari used the word ORO as a trade mark in Australia on the 3 kg packs of Caffè Molinari Oro coffee that Molinari supplied to CMS as part of the disputed shipments. His Honour said at J [574]:

I reach this conclusion having regard to the size, colour, positioning, and prominence of the word “oro” on the packaging in relation to the other packaging elements. I observe that the word “oro” on that packaging is as conspicuous as the other trade mark used—CAFFÈ MOLINARI. I do not accept Cantarella’s contention that the word “oro” is used only as an element in the composite mark MISCELA DI CAFFE ORO, and not as a trade mark its own right.

It is apparent from that paragraph that his Honour’s conclusion was based on the use of the word ORO simpliciter as a trade mark, not that it was substantially identical to the words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ ORO as they appear on the packaging.

81 Cantarella submitted that the only trade mark used on the packaging of the 3kg product was the “Caffè Molinari” mark which appears toward the middle of the package. It drew attention to the prominent location of those words and their distinctive script in black and red. Cantarella submitted in the alternative that if the word ORO was used as a trade mark, it was only as part of the composite mark comprising the words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ ORO. In support of that submission Cantarella observed that those words appear on the packaging twice and always as a “discrete unit” albeit with different orientation.

82 Cantarella accepted that a product can bear more than one trade mark. This possibility is well-established in the authorities and was referred to by the High Court in the course of a wider discussion of the concept of trade mark use in Self Care IP Holdings v Allergan Australia (2023) 277 CLR 186 (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ) at [25].

83 The question is whether the word ORO (whether alone or together with the adjacent words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ) was functioning as a trade mark within the meaning of s 17 of the Act. As Allsop J (as his Honour then was) explained in Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovický Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [191]:

It is not to the point, with respect, to say that because another part of the label … is the obvious and important “brand”, that another part of the label cannot act to distinguish the goods. The “branding function”, if that expression is merely used as a synonym for the contents of ss 7 and 17 of the [Act], can be carried out in different places on packaging, with different degrees of strength and subtlety. Of course, the existence on a label of a clear dominant “brand” is of relevance to the assessment of what would be taken to be the effect of the balance of the label.

84 Given the prominence of the word ORO, whether it is considered as a mark in its own right, or as part of a composite mark, the word is used on the packaging of the 3kg product as a trade mark or as part of a trade mark. We reject Cantarella’s submission to the contrary. The more difficult question is whether the word ORO was used as a trade mark in its own right.

85 A sign may be used as a trade mark even if it is used as a component of a larger composite mark: Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd (2010) 186 FCR 519 (“Sports Warehouse”) (Kenny J) at [133]; Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd v Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 139 (“GRBA v BBNT”) (Nicholas, Katzmann and Downes JJ) at [117]. Whether or not a mark is used as a trade mark depends on the facts of the case and impressions formed based on the facts. The answer to this question is very much a matter of impression in relation to which the primary judge’s conclusion should be given weight.

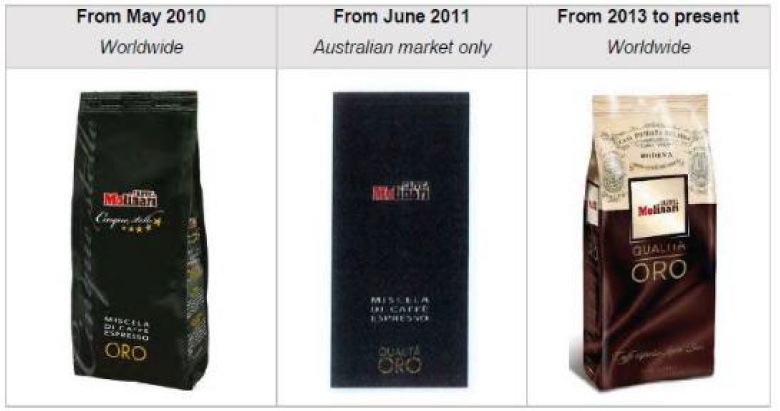

86 The packaging for the 1kg product with the product code 6071 was the impugned packaging in Modena. That packaging, as well as the packaging for product codes 6077 and 6021A/6021E is reproduced at J [204] and J [206]:

87 The High Court summarised the position in Modena as follows (product references have been interpolated) at [11]:

Modena imports coffee from Molinari, a company based in central northern Italy. Molinari has, since 1965, produced a blend of coffee using the marks "CAFFÈ MOLINARI" and "ORO". Molinari exports globally, and began exporting products to Australia in about July 1996 … During the period December 2009 to June 2011, Modena distributed various Molinari products, under and by reference to the abovementioned marks used by Molinari. Approximately 18 months before the trial Molinari ceased using the mark "ORO" on its own [see 6071 packaging above] on its coffee products and substituted the phrase “QUALITÀ ORO” [see 6077 packaging above], about which Cantarella has no complaint …

(emphasis added)

88 In Modena, Cantarella contended that the ORO trade mark was used on packaging for product 6071 and the High Court agreed. In this Court Cantarella submitted that in that case, the word ORO (as used on the 6071 packaging) stood apart from the phrase MISCELA DI CAFFÈ ESPRESSO and was in a different font, letter size and colour to the word ORO. It also submitted that products 6077 and 6021A/6021E which used the phrase QUALITÀ ORO were distinguishable, in that those two words did not stand apart from each other (unlike in the 6071 product) and were also in the same colour.

89 The arguments around the packaging in suit in Modena do not really advance the debate, except to emphasise the role that matters of impression play in deciding whether the word ORO has been used as a trade mark.

90 Cantarella relied on the Full Court decision in Colorado Group Ltd v Strandbags Group Pty Ltd (2007) 164 FCR 506 (“Colorado”) holding that the word “Colorado” was not separately used except as part of a composite mark including a mountain peak device. Allsop J (with whom Kenny and Gyles JJ agreed) said at [110]:

… the examples in evidence reveal an important, perhaps even dominant, effect of the word “Colorado”, but always with a device. That device was part of the trade mark use; it had a capacity to distinguish. It did not, in my view, operate as a separate mark, nor as a mere descriptor. It operated as part of a combination with the word “Colorado”, in part reinforcing it. In these circumstances, I agree with the primary judge’s concluded view that though the word “Colorado” is important in the impression, it cannot be said to have been used alone, rather than as part of a composite mark (with the device) to show origin.

91 We were also referred to the more recent Full Court decision in RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd (2024) 302 FCR 285 (“RB v Henkel”) (Nicholas, Burley and Hespe JJ) upholding the finding of the trial judge that a registered mark for a red ball against a white flash was used only as part of a composite mark comprising the Finish Powerball logo. In addressing that issue the Full Court (at [117]) considered whether the use of the registered mark in the composite mark was use as a separate “badge of origin”.

92 Cantarella submitted that in the present case there was nothing stylised about the use of ORO, that the word was far from the most prominent part of the overall packaging, and that it was only used in conjunction with the words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ. These matters were said by Cantarella to invite consideration of the words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ ORO as a composite expression.

93 We have had regard to the primary judge’s finding, applying Modena, that the word ORO is inherently distinctive and capable of acting as a badge of origin when used in relation to coffee. We have had regard to the prominence given to the word ORO both in the context of the packaging as a whole, and relative to the words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ in the much smaller font. We have also had regard to the appearance of what Cantarella calls the composite expression as it appears on both the front and back of the 3kg packaging, where the relevant words are differently arranged. In each case the word ORO appears much more prominently than the words MISCELA DI CAFFÈ. We consider the word ORO simpliciter acts as a badge of origin. We therefore agree with the primary judge’s finding on this topic.

94 Ground 2 fails.

GROUND 3

95 By Ground 3, Cantarella contends that the primary judge erred in finding that Molinari did not abandon the ORO trade mark in respect of coffee in Australia. The notice of appeal does not say when it was that Cantarella says Molinari abandoned the ORO trade mark, only that it did so by 24 March 2000 (the priority date of the 098 mark) or, alternatively, by 30 September 2013 (the priority date of the 290 mark).

96 Before considering the primary judge’s reasons for rejecting Cantarella’s allegation of abandonment, it is necessary to refer to some further findings made by the primary judge concerning the use of the ORO trade mark by Molinari, and packaging changes made to Molinari’s products.

Packaging prior to Modena

97 The packaging for the 1kg product shown above in paragraph [30] is the packaging which the primary judge found to be in use as at the time of the disputed shipments (J [193](b)). The primary judge was not persuaded that the use of “ORO BAR” on that packaging was use of the ORO trade mark (J [576]). The packaging for the 1kg product was changed as depicted below (“December 2003 1kg packaging”):

98 It is unclear when this change occurred. The best evidence recorded by the primary judge at J [199] – [202], given by Mr Mengoli, was that this change took place at some time after a similar change was made to the packaging for the 250g product with the code 1525E (shown above in paragraph [30]). That change was said to have taken place some time before December 2003. The updated packaging for that product is shown below (“December 2003 250g packaging”):

99 At J [583], the primary judge found that the ORO trade mark had been used on the packaging for the 250g product with the code 1525E, in the form it was in at the time of the disputed shipments and on the December 2003 250g packaging. The 250g product, in both forms of packaging, were found by the primary judge (at J [200]) to have been supplied by Molinari to CMS, and two other distributors, at various times from 1997 to 2007.

100 The primary judge also found at J [583] that the ORO trade mark had been used on the December 2003 1kg packaging. At J [203], the primary judge found that the product in the December 2003 1kg packaging had been supplied to at least one Australian distributor after December 2003. The primary judge referred to invoices dated 25 March, 27 May and 15 July 2004.

101 In oral submissions, Mr Bannon SC submitted that the December 2003 250g/1kg packaging was not use of the ORO trade mark, for the same reasons relied on in relation to the 3kg packaging. It follows from our findings in Ground 2 that Cantarella’s challenge to this finding must fail. The front packaging of those products, and of the 250g product at the time of the disputed shipments, demonstrate a use of the ORO trade mark that is not relevantly distinguishable from that of the 3kg product supplied to CMS in 1995.

102 Mr Mengoli said that, to the best of his recollection, the 1kg product was exported to Molinari’s Australian distributors in the December 2003 1kg packaging until that packaging was updated as follows (J [204] – [205]):

As shown above at [86], the codes for each of these 1kg products are 6071, 6077 and 6021A/6021E, respectively.

103 The primary judge found, at J [208], that Molinari supplied 1 kg packs with the product code 6071 to Modena and another distributor, from 25 March 2009 to 3 March 2011. Molinari also supplied Modena with 1kg packs with the product code 6077 from 6 May 2011 to 17 September 2013, and 1kg packs with the product code 6021A/6021E from 17 September 2013 to 17 September 2021. At J [584], the primary judge found that the ORO trade mark had been used on the packages for the 1kg products with codes 6071, 6077 and 6021A/6021E.

104 Cantarella accepts the use of ORO on product 6071 (the product in suit in Modena) was trade mark use of ORO simpliciter. Cantarella submits that the packaging for each of the 6077 and 6021A/6021E products involved use of a composite mark QUALITÀ ORO, rather than ORO simpliciter.

105 The primary judge found at J [584] that the word ORO was used a trade mark on the 6077 and 6021A/6021E products. His Honour said that he reached that conclusion having regard to the size, colour, positioning and prominence of ORO on the packaging in relation to each of the other packaging elements of the packs in question. His Honour said at J [585] – [586]:

[585] In reaching these conclusions, I have taken into account that, on the packaging for product codes 6077 and 6021A/6021E, the word “oro” appears below the word “qualità”. In my estimation, the proximity of the word “oro” to the word “qualità” does not diminish the prominence given to “oro” (which, in each case, is rendered in larger font than “qualità”) or its significance as a packaging element. Even if traders or customers were to associate the two words because of their proximity to each other on the packaging it does not follow that the word “oro” is not functioning, in its own right, as a trade mark. Once again, the existence of a descriptive element or purpose does not necessarily preclude the sign being used as a trade mark.

[586] That said, I would accept that the word “oro”, as used on the packaging for product codes 6021A/6021E, is a clearer use of “oro” as a trade mark than the use of the word “oro” on the packaging for product code 6077. This is because “oro” is rendered in still larger font than “qualità” and is separated from “qualità” by the use of a horizontal line. Also, “oro” appears in the middle of the pack, which I consider to be somewhat more prominent positioning because of its central location on the pack. I do not regard the use of “oro” on the packaging for product codes 6021A/6021E as any less a trade mark use of “oro” than the use of “oro” on the LAVAZZA QUALITÀ ORO packaging which I have found to infringe the 098 mark and the 290 mark.

His Honour went on to hold at J [588] that, in light of those findings, Cantarella’s case on abandonment could not be sustained as a matter of fact.

106 There are two distinct questions that arise. The first is whether the mark ORO has been used on the relevant products (i.e. with codes 6077 and 6021A/6021E) in its own right or only as part of a different mark comprising, or including, the words QUALITÀ ORO. If there has been no separate use of ORO then the next question is whether ORO simpliciter and QUALITÀ ORO were substantially identical marks. In that context, it is also necessary to mention s 7(1) of the Act which provides:

If the Registrar or a prescribed court, having regard to the circumstances of a particular case, thinks fit, the Registrar or the court may decide that a person has used a trade mark if it is established that the person has used the trade mark with additions or alterations that do not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark.

107 We should also refer to s 100(2) and (3) in Pt 9 of the Act (“Removal of trade mark from Register for non use”) which (like s 7(1) of the Act) refer to the use of a registered trade mark with additions or alterations not substantially affecting its identity. Those provisions enable the Court to find that a registered trade mark has been used notwithstanding differences between the mark used and the registered mark provided that those differences (being additions or alterations) do not substantially affect its identity. E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144 (“Gallo”) was a case in which the High Court found that the registered mark BAREFOOT had been used, notwithstanding the addition of a device comprising a drawing of a bare foot, which was found not to substantially affect the identity of the registered mark. The plurality (French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ) said at [69]:

…. The addition of the device to the registered trade mark is not a feature which separately distinguishes the goods or substantially affects the identity of the registered trade mark because consumers are likely to identify the products sold under the registered trade mark with the device by reference to the word BAREFOOT. The device is an illustration of the word. The monopoly given by a registration of the word BAREFOOT alone is wide enough to include the word together with a device which does not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark in the word alone. So much is recognised by the terms of s 7(1), which speak of additions or alterations which “do not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark”. Except for a situation of honest concurrent use, another trader is likely to be precluded from registering the device alone while the registered trade mark remains on the Register. The device is an addition to the registered trade mark that does not substantially affect its identity. Accordingly, the use of the registered trade mark with the device constitutes use of the registered trade mark in accordance with s 7(1).

108 There may be a question as to whether s 100(2) and (3) (or s 7(1)) can ever apply in circumstances where the relevant marks (i.e. in the form used, and in the form registered) differ to the point that they are not substantially identical: RB v Henkel at [85]. Professors Burrell and Handler argue in Australian Trade Mark Law, (3rd ed, LexisNexis Butterworths, 2024) (“Australian Trademark Law”) at pp 489 – 492 that while the relevant provisions sometimes involve a consideration of whether the marks in question are substantially identical, at other times (as was the case in Gallo), those provisions “merely clarify that a word mark does not cease to be used as a word mark when the word is used in proximity to decorative or ‘non-trade mark’ matter” that does not change the appearance or meaning of the word mark. It is not necessary in this case for us to explore the correctness of their view.

109 Lavazza did not contend that QUALITÀ ORO is substantially identical to ORO. Accordingly, the critical question is whether the primary judge erred in concluding that there had been trade mark use of the word ORO on the relevant products in spite of the presence of the word QUALITÀ immediately above it.

110 We have previously referred to the decision of the Full Court in Colorado holding that there was no separate use of the word “Colorado” as a trade mark when used as part of a composite mark including the mountain peak device. Important to that conclusion was the fact that the word Colorado was always used with a mountain device. As Allsop J observed, the device operated as part of a combination, reinforcing the word Colorado.

111 In GRBA v BBNT the Full Court upheld the primary judge’s finding that there had been no use by the appellant of the words “BED & BATH” as a trade mark by its use of a mark that consisted of the word “House” and the words “Bed & Bath”. The Full Court approved at [117] the following observations of Kenny J in Sports Warehouse at [133]:

… a sign may be registrable as a trade mark even though it is used together with another trade mark, and…there can still be use of a mark where it is a component of a larger composite mark…. Colorado … is not authority for the contrary proposition. Each case turns on its own facts and the trade mark in question viewed in the context of those facts. In Colorado Allsop J held that on the facts of that case the significant use as a trade mark was use as a composite mark and that there was no relevant use of the word “COLORADO” as a separate mark: at [110] (Allsop J); see also at [36] per Gyles J. Where an application for registration relies on use, the question is whether the particular sign for which registration is sought has itself been used as a trade mark so as to become capable of distinguishing the relevant goods or services…

(Some citations omitted)

112 The Full Court also said at [118]:

The question whether there has been trade mark use of multiple marks brought together in composite form will depend on the facts and circumstances of each case and the impression likely to be conveyed by their use. One matter of particular significance in this case is that the words “BED & BATH” were not shown to have ever been used by GRBA as a trade mark except as a component of the House B&B mark. Another matter of significance is the prominence given to the word “House” in the House B&B mark and what we consider to be the largely descriptive character of the words “BED & BATH” when used in relation to retailing services offering homewares.

113 The fact that the mark in question may appear as a component of a larger mark does not preclude a finding that it has been used as a trade mark. Whether or not there has been such use will depend on the circumstances and the overall impression conveyed.

114 In the case of both the 6077 and 6021A/6021E products, the word ORO is given prominence by the use of a larger font and, in the case of 6021A/6021E, ORO occupies a central position on the pack separated from the word QUALITÀ by the horizontal line immediately above the word ORO. We also note that the word ORO is given prominence across the relevant product range including on packaged coffee products 1525E, 6091 (as depicted in J [201], being the December 2003 1kg packaging) and 6071. The use across the range is consistent with the use of ORO as a sub-brand within the Molinari range of packaged coffee.

115 The primary judge’s conclusion on this issue depended on matters of impression about which minds might reasonably differ. On balance, however, we agree that the word ORO on the 6077 and 6021A/6021E packages was functioning in its own right as a trade mark.

116 There was no dispute between the parties as to the correctness of the primary judge’s summary of the principles with respect to the loss of ownership of a registered trade mark through intentional abandonment. His Honour accepted that ownership of a registered trade mark could be lost by an intentional abandonment. Whether an intentional abandonment is established in a given case is a question of fact to be determined having regard to all the circumstances of the case.

117 The primary judge said at J [588]:

… Cantarella’s case on abandonment, insofar as it is based on non-use by Molinari of the ORO word mark in Australia in respect of coffee, cannot be sustained as a matter of fact. The evidence establishes that before Cantarella’s first use of the ORO word mark in relation to coffee, before the priority date of the 098 mark, and before and after the priority date of the 290 mark, as well as at the commencement of the present proceeding (including the commencement of Lavazza’s cross-claim), Molinari used the word “oro” as a trade mark in Australia in relation to coffee.

118 Cantarella’s submissions to the primary judge, and in this Court, focused heavily on what was said to be Molinari’s non-use of the trade mark ORO in Australia over many years. Cantarella submits that, had Molinari registered the ORO mark in Australia, the registration would have been liable to be removed under s 92(4)(a) or (b) of the Act for non-use. It relied on what was said to be “the paradoxical effect of elevating the ‘rights’ of the owner of an unregistered trade mark no longer in use, to a position superior to that of the owner of a registered trade mark no longer in use and so vulnerable to cancellation”. However, Cantarella’s argument has no application in circumstances where the primary judge’s finding (which we have upheld) was that Molinari used the ORO mark in Australia in relation to coffee between 1995 and September 2021.

119 Cantarella also submitted that the primary judge’s finding that the packaging for products 6077 and 6021A/6021E involved the use of the ORO trade mark was “tantamount to finding…that Modena did not comply with the injunction made in the [Modena] proceedings”. In Modena, the majority explained that Cantarella had “no complaint” regarding Molinari’s use of QUALITÀ ORO and set out in a footnote to that statement:

“It was noted in the primary judge’s orders that nothing in them should be taken to

prevent Modena from using the phrase “QUALITÀ ORO” in respect of its products.”