Federal Court of Australia

Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd v Motorola Solutions Inc [2024] FCAFC 168

Appeal from: | Motorola Solutions, Inc. v Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd (Liability) [2022] FCA 1585 |

File number: | NSD 675 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | BEACH, O'BRYAN AND ROFE jJ |

Date of judgment: | 18 December 2024 |

Catchwords: | PATENTS – indirect infringement – appellant found to have infringed respondent’s patent (Australian Patent No 2005275355) relating to digital mobile radios (DMRs) using Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA) technology to divide frequency channel – appeal against finding of infringement – disputed issues of construction – appeal against finding of validity – whether the invention claimed involved an inventive step – whether the invention claimed is useful – whether the invention claimed is a manner of manufacture – appeal dismissed PATENTS – validity – respondent’s patent (Australian Patent No. 2006276960) relating to DMRs using TDMA technology found to be invalid by reason that the invention claimed did not involve an inventive step – cross-appeal against that finding dismissed – cross-contentions concerning manner of manufacture and infringement also dismissed COPYRIGHT – indirect infringement - respondent owner of Australian copyright in 11 computer programs in source code – appeal against finding of infringement by the importation into Australia of DMR devices containing firmware in object code, where firmware compiled from appellants’ source code in China and installed into DMR devices in China, and where appellants’ source code developed using respondent’s source code – whether the appellants copied a substantial part of the respondent’s copyright works – whether fact that copied parts of the respondent’s copyright works derived from earlier versions of the respondent’s computer renders them not original for the purposes of infringement, such that the copied parts are not a substantial part – whether appellants otherwise copied a substantial part of the respondent’s copyright works – the correct approach to assessing the copying of a substantial part – where appellants deliberately deleted source code to suppress evidence which might assist in a copyright infringement suit – application of the maxim omnia praesumuntur contra spoliatorem (all things are presumed against the wrongdoer) – primary judge’s approach to assessing the copying of a substantial part shown to be in error COPYRIGHT – requirement of knowledge for the purposes of ss 37 and 38 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act) – whether relevant executives who undertook or supervised copying were acting within the scope of their authority – principles concerning attribution of knowledge to a corporation – no error shown COPYRIGHT – award of additional damages under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act – discretionary decision – no error in the exercise of discretion shown |

Legislation: | Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 10, 13(1), 14, 31(1), 32, 36(1), 37, 38, 115(4), 126 Copyright Amendment Bill 1984 (Cth) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 81, 136 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 27 Patents Act 1990 (Cth) ss 7(3), 18(1), 117 |

Cases cited: | Aequitas Ltd v AEFC Leasing Pty Ltd (2001) 19 ACLC 1,006 Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Limited (2002) 212 CLR 411 Albert v S Hoffnung & Co Ltd (1921) 22 SR (NSW) 75 Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd (2018) 261 FCR 301 Allen v Tobias (1958) 98 CLR 367 Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S [2008] FCA 559 Apotex Pty Ltd v Warner-Lambert Co LLC (No 2) [2016] FCA 1238 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (2022) 274 CLR 115 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v DAP Services (Kempsey) Pty Ltd (in liq) (2007) 157 FCR 564 Autodesk Inc v Dyason (No 2) (1993) 176 CLR 300 Beach Petroleum NL v Johnson (1993) 43 FCR 1 Berry v CCL Secure Pty Ltd (2020) 271 CLR 151 Brambles Holdings Ltd v Carey (1976) 15 SASR 270 Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd (2001) 117 FCR 424 CA Inc v ISI Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 23 Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 156 Commissioner of Patents v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 202 Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Limited (1959) 102 CLR 232 Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd (2020) 277 FCR 267 Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Kojic (2016) 249 FCR 421 Data Access Corporation v Powerflex Services Pty Ltd (1999) 202 CLR 1 Davies v Lazer Safe Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 65 Designers Guild Ltd v Russell Williams (Textiles) Ltd [2000] 1 WLR 2416 Director of Public Prosecutions (Vic) Reference No 1 of 1996 [1998] 3 VR 352 Farrow Finance Company Ltd (in liq) v Farrow Properties Pty Ltd (in liq) [1999] 1 VR 584 Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 Fuchs Lubricants (Australasia) Pty Ltd v Quaker Chemical (Australasia) Pty Ltd (2021) 284 FCR 174 Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (No 2) (2012) 200 FCR 296 Hyperion Records Ltd v Sawkins (2005) 64 IPR 627 IceTV Pty Limited v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (2009) 239 CLR 458 Interlego AG v Croner Trading Pty Ltd (1992) 39 FCR 348 International Business Machines Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1991) 33 FCR 218 IPC Global Pty Ltd v Pavetest Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 82 JR Consulting & Drafting Pty Ltd v Cummings [2016] FCAFC 20 Katsilis v Broken Hill Pty Co Ltd (1977) 18 ALR 181 Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd (1995) 183 CLR 563 Ladbroke (Football) Ltd v William Hill (Football) Ltd [1964] 1 WLR 273 Lennard's Carrying Co. Ltd. v. Asiatic Petroleum Co. Ltd. [1915] AC 705 Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) (2007) 235 CLR 173 Meridian Global Funds Management Asia Ltd v Securities Commission [1995] 2 AC 500 Mylan Health Pty Ltd (formerly BGP Products Pty Ltd) v Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd (formerly Ranbaxy Australia Pty Ltd) [2019] FCA 28 N V Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Limited (1995) 183 CLR 655 Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 2 Oxworks Trading Pty Ltd v Gram Engineering Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 240 Productivity Partners Pty Ltd (trading as Captain Cook College) v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2024] HCA 27 Raben Footwear Pty Ltd v Polygram Records Inc (1997) 75 FCR 88 Re Hampshire Land Company [1896] 2 Ch 743 Repipe Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Patents [2021] FCAFC 223 Research in Motion v Samsung Electronics Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 176 FCR 66 SW Hart v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 Tesco Supermarkets Ltd v Nattrass [1972] AC 153 The Ophelia (1916) 2 AC 206 UbiPark Pty Ltd v TMA Capital Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 885 University of Sydney v ObjectiVision Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1625 Venus Adult Shops Pty Ltd v Fraserside Holdings Ltd (2006) 157 FCR 442 Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-areas: | Copyright and Industrial Designs |

Number of paragraphs: | 923 |

Date of last submission: | 18 December 2023 |

Date of hearing: | 27, 28, 29 and 30 November 2023 |

Counsel for the Appellants and Cross-Respondents: | C Dimitriadis SC and J S Cooke SC with J Ambikapathy and M Evetts |

Solicitors for the Appellants and Cross-Respondents: | Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers Pty Ltd and Minter Ellison |

Counsel for the Respondent and Cross-Appellant: | C A Moore SC with P L Arcus and N L Gollan |

Solicitors for the Respondent and Cross-Appellant: | Herbert Smith Freehills |

ORDERS

NSD 675 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | HYTERA COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION LTD First Appellant HYTERA COMMUNICATIONS (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD ACN 165 879 701 Second Appellant | |

AND: | MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS INC. Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS INC. Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | HYTERA COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION LTD First Cross-Respondent HYTERA COMMUNICATIONS (AUSTRALIA) PTY LTD ACN 165 879 701 Second Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | BEACH, O'BRYAN AND ROFE JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 December 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The First and Second Appellants’ Amended Notice of Appeal dated 8 November 2023 be dismissed.

2. The Cross-Appellant’s Amended Notice of Cross-Appeal dated 27 November 2023 be allowed in part, in respect of grounds 2 and 3, and otherwise dismissed.

3. The Cross-Appellant’s Amended Notice of Cross-Appeal dated 27 November 2023 be listed for case management before this Court at 10.15 am on Friday 7 February 2025 for the making of timetabling orders for the further hearing and determination of the copyright infringement claims that arise on the appeal in accordance with the reasons accompanying these orders.

4. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), until further order of the Court, access to and disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the unredacted text of the reasons for judgment delivered today be restricted to the legal representatives of the parties and those persons to whom access is allowed under the terms of the confidentiality regimes agreed between the parties on 10 April 2018 and/or the confidentiality regime agreed between the parties on 24 May 2019.

5. Nothing in Order 4 or any other earlier order of the Court prevents any party from publishing the covering pages of these reasons for judgment up to and including these orders and paragraphs 1 to 21 and 918 to 923 of the reasons.

6. By 31 January 2025, the legal representatives for the parties exchange highlighted versions of the reasons for judgment identifying any parts of the reasons that are claimed to contain information confidential to their respective clients for redaction.

7. By 14 February 2025, the legal representatives for the parties confer on the proposed redactions and, if the parties are able to agree on the proposed redactions, provide to chambers an agreed form of the reasons for judgment with the proposed redactions highlighted, together with an agreed redacted form of the reasons for judgment that is suitable for publication.

8. In the event the parties are unable to agree on the proposed redactions, by 21 February 2025 the legal representatives for the parties provide chambers with:

(a) a version of the reasons for judgment which identifies the redactions which have been agreed and those which are in dispute; and

(b) a short written submission addressing the areas of disagreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

A. Introduction

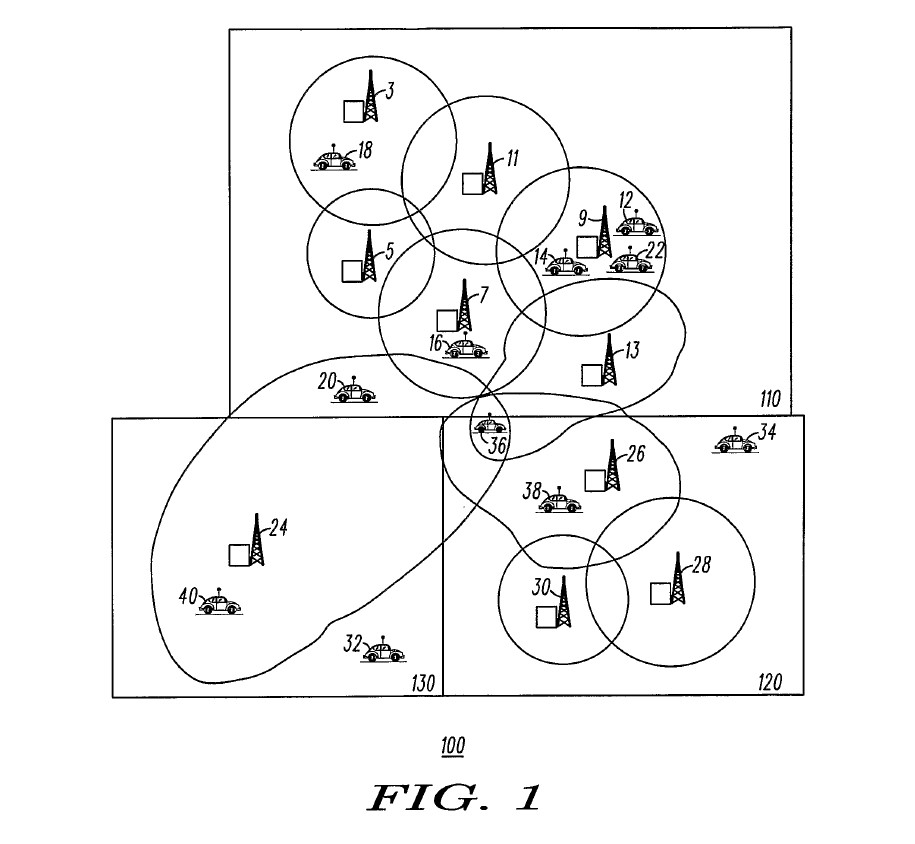

1 This appeal concerns digital mobile radios (DMRs) supplied in Australia by Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd (Hytera) and its Australian subsidiary, Hytera Communications (Australia) Pty Ltd (Hytera Australia), including the computer firmware incorporated within the devices. In these reasons, Hytera and Hytera Australia are referred to collectively as ‘Hytera’ unless there is a reason to refer to Hytera Australia specifically.

2 A DMR is a digital two-way radio device that can both receive and transmit signals from other radio devices operating on the same radio frequency. DMRs can be mobile (e.g. affixed to a vehicle which moves) or portable (e.g. carried around by a person). An individual DMR can communicate directly with another DMR and, when it does so, the two devices are said to be communicating in ‘direct mode’. However, DMRs are frequently deployed with fixed base stations, or ‘repeaters’, through which they communicate with each other and by which means their range is extended. In contrast to mobile telephones, two-way radios are focussed on group call communications which are also known as one-to-many communications and are designed to be used in sectors such as government, industry and emergency services. Two-way radio systems may use analogue or digital systems. Analogue radio systems use electrical signals which, at least conceptually, resemble sound waves to deliver voice audio over a radio frequency. Digital radio systems, by contrast, process sounds into patterns of numbers (in binary code) which are then transmitted over a radio frequency. Digital two-way radios can allow users to transmit data as well as audio and they are also more secure than analogue radios.

3 In April 2005, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) published a standard for a digital two-way radio system (2005 DMR Standard). The purpose of the 2005 DMR Standard was to reduce channel interference and to increase radio spectrum efficiency. The 2005 DMR Standard concerned the division of a frequency band within the radio spectrum (a channel) into timeslots so that more than one person may use the same channel at the same time. This is known as Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA).

4 Motorola Solutions Inc (Motorola) began work on a DMR project in earnest in 2003. The software development for this project was called the ‘Matrix’ project. The development of the Matrix software continued until February 2007. Motorola began selling its DMR devices in the United States and Canada in the first quarter of 2007. Those devices utilised the initial version of the firmware resulting from the Matrix project which was known as ‘Release 1’.

5 From about 2005, Hytera was also seeking to develop a DMR device. The design task had been given to Professor Sun within Hytera. By September 2007, Hytera’s development of a DMR device had proceeded as far the creation of a prototype. However, by the end of 2007, Hytera’s DMR project was confronted with two significant problems. The first was that it was going to result in a product which would not be competitive with Motorola’s device. The second was that it would take at least until the end of 2009 before the process of commercialisation of the product could begin, and a product launch would not occur before the middle of 2011. By the end of 2007, Hytera’s development of its DMR device was in disarray. Hytera had wasted three years getting to that position and its competitor, Motorola, was already in the market.

6 The President and Chief Executive Officer of Hytera, Mr Chen, recruited Mr GS Kok from Motorola, commencing mid-February 2008. Mr GS Kok was a senior employee within Motorola on the Matrix project. At Hytera, Mr GS Kok was put in charge of the DMR team, replacing Professor Sun. Very soon after his arrival at Hytera, Mr GS Kok provided Mr Chen with a negative assessment of the state of Hytera’s DMR project and proposed the recruitment of additional engineers from Motorola who had worked on the Matrix project. Over the ensuing months, Mr GS Kok recruited 12 engineers from Motorola.

7 At trial, Hytera did not dispute that Mr GS Kok and certain of the other ex-Motorola engineers brought with them to Hytera, without authorisation from Motorola, Motorola documents and computer code relating to Motorola’s DMR device and made use of some of these materials, including the computer code, in the development of Hytera’s firmware for its DMR device. That in itself is a damning admission, but the primary judge’s ultimate findings were even stronger. His Honour found that the ex-Motorola engineers took with them to Hytera all of the computer source code for Motorola’s DMR device to provide themselves with a resource for the purposes of writing Hytera’s source code for its DMR device. His Honour characterised Hytera’s actions as a “substantial industrial theft” and found that (Motorola Solutions, Inc. v Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd (Liability) [2022] FCA 1585 (the primary judgment or PJ) at [1576]):

There is no doubt that Hytera’s software engineers engaged in industrial scale harvesting of Motorola’s source code and that they set out to make this as difficult to detect as possible.

8 The Hytera DMR devices were brought to market in March 2010. The primary judge found that Hytera benefitted from the actions of the ex-Motorola engineers in at least two ways: first, it got to market with devices which were commercially competitive with Motorola’s products where otherwise it would not have done so; and secondly, it got to market by at least 15 months earlier than it otherwise would have. From September 2013, Hytera began distributing its DMRs in Australia.

9 In March 2017, Motorola commenced proceedings against Hytera in the United States alleging patent infringement and breach of confidence. In July 2017, Motorola commenced proceedings (the subject of the primary judgement) in Australia alleging infringement of Australian Patent No 2005275355 (355 patent), Australian Patent No. 2006276960 (960 patent) and Australian Patent No. 2009298764 (764 patent) under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Patents Act). Each of those patents are methods which refine the efficiency of TDMA. Motorola alleged that Hytera infringed the Australian patents by distributing in Australia Hytera’s DMR devices without Motorola’s license. By cross-claim, Hytera challenged the validity of the Australian patents.

10 Following the discovery by Hytera of its source code for its DMR products for the purposes of the patent proceeding, Motorola added a claim for infringement of copyright in its own source code, first in the United States proceeding (in August 2018) and then in the proceeding before the primary judge (in December 2018). Substantially complete particulars of Motorola’s copyright claim were provided to Hytera in June 2019. Motorola alleged that Hytera infringed its Australian copyright in the ‘Release 1’ version of its computer source code for its DMR devices by, first, importing into Australia Hytera DMRs containing firmware which was a reproduction or an adaptation of the whole or a substantial part of Motorola’s source code and, second, making that firmware available for download in Australia from its website portal. Those claims were made under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act).

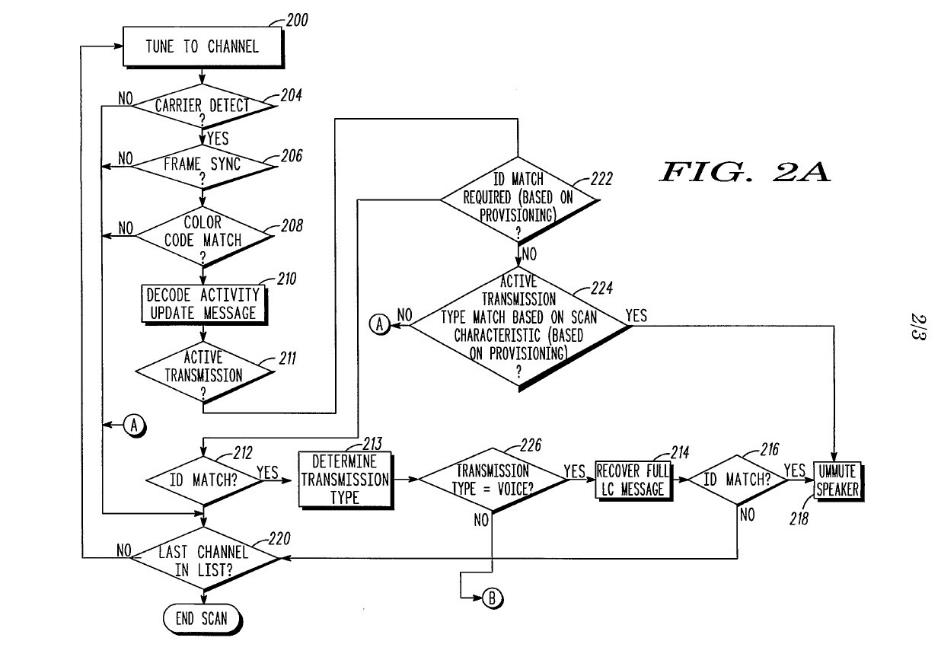

11 In 2018, Hytera reprogrammed its DMR devices to remove or disable functionalities relevant to the patents in suit. Then, on 17 May 2019, Hytera gave undertakings to Motorola not to exploit devices installed with non-reprogrammed firmware, not to make available the non-reprogrammed firmware and to refrain from reversing the reprogramming unless this Court found that the non-reprogrammed firmware did not infringe Motorola’s patents. By 20 November 2019, Hytera had taken sufficient steps by way of reprogramming to prevent further patent infringement.

12 In June 2019, after receiving particulars of Motorola’s copyright claim, Hytera began to rewrite the firmware for its DMR devices relevant to the copyright claims. From 22 November 2019, Hytera deployed rewritten firmware in its DMR devices. On 9 April 2020, Hytera gave undertakings to the Court not to import or sell in Australia DMR devices with the allegedly infringing firmware. On 12 June 2020, Hytera gave undertakings to the Court not to make the allegedly infringing firmware available for download in Australia from its website portal.

13 The trial of the proceeding occurred in two stages. The patent issues were heard in July and August 2019 over a period of 13 days. The copyright issues were heard between July and October 2020 over a period of 23 days. The evidence was voluminous and the subject matter of the proceeding was technical and complex.

14 The primary judge delivered judgment on 23 December 2022. In respect of the claims for patent infringement, his Honour concluded that Hytera had infringed claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 10 of the 355 patent in respect of the distribution of its DMR devices before 20 November 2019, that Hytera had not infringed the 764 patent, and that the 960 patent was invalid. In respect of the claims for copyright infringement, his Honour concluded that Hytera had infringed Motorola’s copyright in six of the eleven works (comprising computer software) in respect of which Motorola made claims.

15 The primary judge granted declaratory and injunctive relief in respect of the above conclusions, but deferred the question of compensatory relief (damages or an account of profits) pending any appeal. His Honour also found that Motorola was entitled to an award of additional damages in respect of Hytera’s copyright infringement, but not in respect of Hytera’s patent infringement.

16 By its amended notice of appeal, Hytera challenges all of the findings of patent and copyright infringement made against it and the conclusion that Motorola was entitled to an award of additional damages in respect of Hytera’s copyright infringement. By its amended notice of contention on Hytera’s appeal, Motorola contends that the primary judge’s findings on patent infringement and copyright infringement which are challenged by Hytera should be affirmed on additional grounds.

17 By its amended notice of cross-appeal, Motorola challenges the findings that the 960 patent is invalid and the scope of the findings that Hytera infringed Motorola’s copyright (contending that the scope of the infringement was wider than as found by the primary judge). By its amended notice of cross-contention, Hytera contends that the primary judge’s findings challenged by Motorola should be affirmed on additional grounds.

18 The grounds of appeal and contentions raised by the parties on this appeal are extensive. A number of the grounds and contentions raise significant matters of legal principle. Other grounds and contentions challenge respectively findings of fact, the drawing of inferences and the overall evaluation undertaken by the primary judge. In undertaking its appellate function on this appeal, the Court has kept in mind the well-established principles that guide appellate review in this Court. The appeals are by way of rehearing: s 27 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). The Court’s review of the primary judge’s findings of fact and inferences drawn from those facts are subject to the principles stated in Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 (Fox v Percy) and Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 (Warren v Coombes). The principles applicable to appellate review of evaluative judgments (such as a finding that a substantial part of a work has been copied) have been discussed in a number of cases. In Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd (2018) 261 FCR 301, the Full Court affirmed the principles as stated in Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd (2001) 117 FCR 424 (Branir). On such appeals, the Court must first make up its own mind on the facts, observing the “natural limitations” that exist in the case of any appellate court proceeding wholly or substantially on the record, as explained in Fox v Percy. Having determined the facts, the Court must undertake itself the required evaluative assessment. As also explained by Allsop J in Branir (at [28]-[30]), while the appeal court has a duty to make up its own mind, it does not deal with the case as if trying it at first instance. Appellate intervention requires the demonstration of error on the part of the trial judge. Those principles were recently reaffirmed by the Full Court in Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 156 which reiterated that the standard of appellate review in the context of evaluative judgments is the “correctness standard” (at [133]).

19 In relation to the case concerning patent infringement, the Court has concluded that the grounds of appeal advanced by Hytera (on its appeal) and by Motorola (on its cross-appeal) should be rejected.

20 In relation to the case concerning copyright infringement, the Court has concluded that Motorola’s grounds of appeal should be upheld, whereas Hytera’s grounds of appeal should be rejected.

21 It follows that Hytera’s appeal is dismissed. With respect to Motorola’s cross-appeal, ground 1 is rejected while grounds 2 and 3 are upheld. However, the Court will not make final orders with respect to Motorola’s cross-appeal. Although the Court has upheld grounds 2 and 3 of Motorola’s cross-appeal by finding that the primary judge erred in certain respects to the approach taken to the determination of copyright infringement, to this point the Court is not able to determine whether Motorola’s claim of copyright infringement should succeed in whole or in part. Relevant factual findings have not been made that would enable this Court to determine finally the copyright infringement case applying the methodology that the Court considers is correct. The Court considers that the appropriate course is to conduct a further hearing at which the parties will be given an opportunity to advance further submissions in respect of the copyright infringement claims that arise on the appeal in accordance with the Court’s reasons. The hearing will be a continuation of Motorola’s cross-appeal. The Court will list the matter for case management to make timetabling orders for the conduct of the further hearing.

B. Patent validity and infringement

B.1 Introduction to the 355 patent appeal and the 960 patent cross-appeal

22 It is appropriate to begin with some introductory remarks relating to Hytera’s appeal concerning the 355 patent and Motorola’s cross-appeal concerning the 960 patent.

23 In the proceedings before the primary judge, Motorola alleged that Hytera’s DMRs infringed three of its Australian standard patents. As noted earlier, these patents relate to TDMA technology which permits a frequency band within the radio spectrum (that is, a channel) to be divided into timeslots so that more than one person may use the same channel at the same time. The asserted claims of the three patents involve methods which are said to refine the efficiency of TDMA.

24 The 355 patent is a method and system which improves the time taken to scan a TDMA channel to determine whether there is activity on that channel. It has a priority date of 26 July 2004.

25 The 764 patent is a method for efficiently synchronising to a desired timeslot in a TDMA communication system.

26 The 960 patent is a method and system for accessing a base station which has been de-keyed, a concept which is explained below. It has a priority date of 28 July 2005.

27 At first instance Motorola alleged that Hytera had imported into Australia DMRs which infringed the methods of the three patents and it sued for secondary infringement. Hytera disputed Motorola’s construction of each of the patents and contended in each case that, even if the asserted claims of the patents were to be construed as Motorola suggested, each patent was invalid for various reasons.

28 The primary judge concluded that Motorola’s construction of the 355 patent was correct and that the challenges to its validity such as a lack of inventive step and there being no manner of manufacture failed. His Honour concluded that Motorola’s infringement case in relation to the 355 patent largely succeeded although he accepted that Hytera did not infringe the patent after November 2019 when it took steps to ensure that existing mobile stations were upgraded before reprogrammed base stations were supplied to end users.

29 The primary judge rejected Motorola’s infringement case on the 764 patent. His Honour rejected Motorola’s construction of that patent, but said that even if it had been correct, he would have concluded that the patent was invalid as it would not have been fairly based. His Honour’s findings concerning the 764 patent have not been challenged before us and we need say nothing further about that patent or the proceedings at first instance concerning it.

30 As to the 960 patent, the primary judge held that Motorola’s construction of the 960 patent was correct, but he held that the patent was invalid for want of an inventive step. His Honour rejected Hytera’s contention that no manner of manufacture was involved.

31 Hytera’s appeal challenges the primary judge’s findings and determination concerning the 355 patent. Motorola has filed a notice of contention on one aspect concerning construction.

32 Motorola’s cross-appeal challenges the primary judge’s findings and determination concerning the 960 patent. Hytera has filed a notice of cross-contention on aspects concerning construction and infringement if the 960 patent is held to be valid. It has also sought to re-agitate the manner of manufacture question.

33 Before dealing with the specific grounds of appeal and cross-appeal, it is necessary to set out some of the technical background.

B.2 Background — two-way radio communications and relevant technology

34 To understand the issues which have arisen before us, it is necessary to say something concerning the electronic engineering underpinning two-way radio communications. We have gratefully drawn from aspects of the primary judge’s detailed technical description that are relevant to the grounds of appeal and cross-appeal before us.

General

35 Radio is a method of transmitting electromagnetic energy across distance without using a direct, wired connection. The electromagnetic energy takes the form of radio waves which have a certain frequency. Radio waves are generated and sent out through a transmitter and are then received by a radio receiver using antennas. Depending upon their length, radio waves may travel by line of sight, by being reflected off buildings or other objects, in which case the communications will not travel beyond the horizon, and by being reflected off the ionosphere, in which case they can return to earth beyond the horizon. Different radio frequencies (RFs) are used for these different reflective requirements.

36 As stated above, radio communications can be transmissions of audio (analogue transmissions) or of data (digital transmissions). Where a transmission is an analogue transmission, the whole of the voice transmission can be sent and decoded without any additional information being transmitted. Contrastingly, where a digital communication is involved, the decoding of the message requires the use of overheads. Overheads are the bits of digital information that are not associated with the substantive transmission, being the payload. So, digital transmissions are made up of two kinds of information being the overhead and the payload.

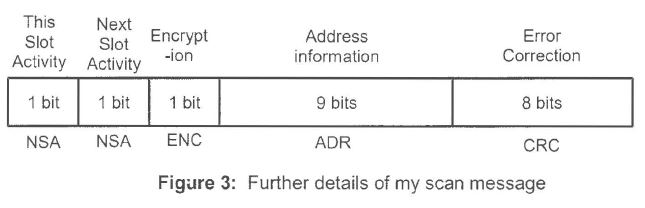

37 One of the overheads in a digital communication arises from the need to achieve synchronisation between the devices which is achieved using a synchronisation pattern. Another relates to the scanning of channels which involves the use of information to identify the devices to which a payload is to be delivered. This kind of information is referred to as control information. The more of the radio transmission that is consumed by transmitting control information, the less of it is available to transmit payload.

The radio spectrum

38 The radio portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, which radio communications are transmitted on, is divided into three sub-categories known as frequency bands. These bands are the high frequency band (3,000 kHz to 30 MHz), the very high frequency band (30 MHz to 300 MHz) and the ultra-high frequency band (300 MHz to 3 GHz). Each of these bands is further separated into bandwidth channels which radio users use to transmit communications. These channels reflect the frequency range occupied by a carrier signal and are separated by a space known as channel spacing.

39 The size of the bandwidth channel and the size of the channel spacing between each channel is determined in Australia by the Australian Communications and Media Authority. In 1999, ACMA determined that two-way radios would use channel bandwidths of 12.5 kHz, meaning each channel may occupy a range of frequencies in the radio spectrum which are no wider than 12.5 kHz. The size of this bandwidth limits the number of frequencies that can be defined inside a relevant band. Generally, the wider the channel bandwidth, the better the audio fidelity or the higher the data rate will be.

The components of radio devices

40 A two-way radio is a device that can both receive and transmit signals from other radios operating on the same RF. There are two kinds of two-way radio devices being half-duplex devices and full-duplex devices. A half-duplex radio is one which permits the user to talk or to listen but not to do both at the same time. Contrastingly, a full-duplex radio has the ability to send and receive transmissions at the same time. It does so by sending transmissions on one frequency and receiving them on another.

41 In the case of a half-duplex two-way radio, the user presses a Push-To-Talk (PTT) button which activates the transmitter. When the PTT button is not pressed, the device’s radio receiver is activated. Half-duplex radios may also function by using what is referred to as simplex communication. Where this occurs, the transmission and reception occurs on a single RF. In other words, the radio switches between the transmit and receive functions, transmitting on one frequency and then switching to receive any incoming transmissions using the same frequency.

42 To be able to transmit and receive at the same time, full-duplex radios may use two different frequencies. Typically, this means that one frequency is assigned for the radio to transmit and another is assigned to receive communications. Together, the two frequencies are known as a frequency pair or a physical channel. Alternatively, a full-duplex radio may use what are called frequency sharing methods. In a digital system this involves breaking the communications up into digital packages and transmitting the packages sufficiently frequently such that the underlying process is not audible.

Terminal equipment

43 Mobile stations are typically vehicle based installations that allow for communication to other local terminal equipment, say, between police cars. These are also referred to as radios or subscriber units. They may communicate in either direct mode or repeater mode. A direct mode transmission occurs between two mobile stations without the use of a repeater and usually takes place on the same transmit and receive frequencies, that is, with each radio switching between transmitting and receiving communications. A direct mode communication is possible so long as both mobile station users are not too far apart and there is no obstruction between the sender of the communication and the receiver.

Repeater equipment

44 Repeaters, which are also referred to as base stations, are devices which relay transmissions from terminal equipment, and so extend the coverage of those terminals. They are typically located above terminals such as on top of a mountain or building, and utilise a hard-wired power source. So, where a repeater is used, the sender of the communication will transmit the message from their terminal and once the transmission reaches the base station, the base station will then repeat the message to the intended receiver. In a trunked system, a repeater also repeats the transmissions which it receives from a control station.

45 Relatively simple two-way radio systems only include a single repeater. Multiple repeaters, however, may be interconnected to increase the coverage area (a cell) and to enable direct links to control stations. Repeaters typically receive and transmit on two different RFs, known as the uplink and the downlink. Terminals transmit information such as voice calls through the uplink towards the repeater. The repeater then retransmits or repeats the information through the downlink towards another repeater or terminal. In its most simple form, a repeater is therefore two terminal devices connected together, with one operating as the uplink and one operating as the downlink. The downlink is essential to the processes of de-keying and re-keying which are relevant to the 960 patent.

46 In many two-way radio systems, the repeater is designed to de-key after a transmission. When a repeater de-keys, it turns off the downlink. This means that the repeater cannot transmit information using the downlink unless it re-keys. Further, terminals listening to the repeater’s downlink frequency will not receive transmissions from that repeater. A common reason why a repeater will de-key is because there is no active terminal using the repeater’s cell. As the radio spectrum is a limited and shared resource, repeaters are often programmed to de-key in order to ensure that they are not powered on when they are not in use and to allow other repeaters to use the frequency.

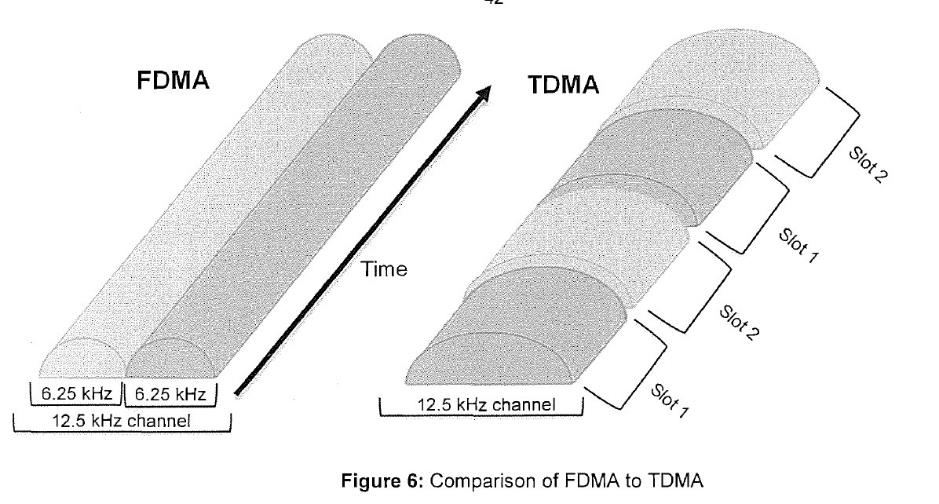

47 Repeaters often have a fixed timer, for example, 10 seconds which starts when the repeater detects that there is no activity on the repeater’s uplink frequency. This will occur when there is no transmission being sent from any of the terminal devices. This timer is often referred to as the hangtimer. One of the purposes of the hangtimer is to ensure that the recipient has sufficient time to respond to a communication before the repeater de-keys. When the hangtimer expires, the repeater de-keys.

48 If a mobile station wants to utilise a de-keyed repeater for transmissions, it must first wait for the repeater to re-key. When the repeater re-keys, it reactivates the downlink and can send outgoing transmissions again. Although a de-keyed repeater’s downlink is deactivated, its uplink is still monitored and is able to receive transmissions. This allows a de-keyed repeater to receive messages from terminals, enabling it to re-key. But the process of re-keying can take time and delay transmissions. This can be a problem for users, such as members of the emergency services who need to relay a communication quickly.

Control stations and control channels

49 Control stations facilitate communication and signalling to remote terminal equipment. They may be positioned in a control centre or a depot. A simple control station may consist of a speaker, a microphone and a PTT switch. A more complex control station may include several networked computers and remotely accessible data bases. Control stations are a common feature of trunked systems. A control channel is a channel in a trunking system where network access is requested and assigned. They are used by radio users to be assigned to a traffic channel to begin a voice transmission.

Modems

50 Modems facilitate the transfer of data using RFs. Prior to July 2004, some analogue two-way radio systems included modems as an optional component. This is because their presence allowed analogue systems to transmit data, as opposed to just voice, over the analogue signal. By allowing data to be transmitted in this way, control information could therefore be transmitted even though the system was not digital. Examples of the kind of control information that could be transmitted included information identifying a particular terminal, information identifying groups of terminals to be included in a communication, and information as to which channels were to be used for what. The word “terminal” is used interchangeably with “subscriber unit” or “mobile station”.

51 In analogue systems, modems were a physical component of the radio device, that is, hardware in the terminals and the repeaters, which turned converted data into an analogue, that is, audio signal. But in digital systems, modem functionality was incorporated into the software of the devices and no physical modem was needed.

Two-way radio functionality

52 Cellular communication systems such as mobile phones are designed for one-to-one communications and so are usually used by individual consumers. By contrast, two-way radios are designed to be used by professionals in sectors such as government, industry, and emergency services and so are focused on group call communications which are also known as one-to-many communications. As a result, two-way radios utilise a feature known as talkgroups. Mobile phones are typically smaller, have lower power levels and are full-duplex devices, that is, they can communicate and receive at the same time. Two-way radios are larger devices with a relatively higher power level and may be full-duplex or half-duplex, in which case they cannot transmit and receive at the same time.

53 Two-way radios can engage in direct mode between themselves, or in repeater mode via a repeater. Mobile phones do not have a direct mode and only communicate through network infrastructure.

Talkgroups

54 A talkgroup is a way of organising multiple individual radio devices into groups of users who can all communicate with each other. Each talkgroup has its own group identity which is programmed into the memory of each individual radio device. When a radio device that is a member of a specific talkgroup transmits, all the other members of the talkgroup are able to hear and respond to that transmission. The use of talkgroups allows for private communications between members of a particular talkgroup by excluding radio users that are not part of that group. It also facilitates effective communication, in that one user can communicate to a group with a single transmission.

Scanning

55 Mobile and portable radio users tune into specific channels in order to transmit or receive communications. Users can select a channel either manually, and usually through a dial or buttons, by selecting an appropriate channel, or by using the radio automatically to scan channels. The 355 patent is concerned with scanning.

56 The process of scanning involves the receiver radio searching multiple channels (a scan group) to find a valid transmission. A scan group consists of a group of frequencies that may be of interest and is stored in the memory of the radio. When the radio determines that it has found a valid transmission, it will stop and lock onto that channel and then send the communication to the radio’s speaker. A valid transmission is a communication which meets specific conditions, such as having certain talkgroup or address information. The conditions which will make a transmission valid are programmed into the radio device. If the receiver radio decodes the message and identifies that all of the relevant conditions are present, the transmission will be deemed valid and will be broadcast through the speaker. If the transmission does not meet all of the programmed conditions, however, it will be ignored. In the example of the firefighter above, for instance, the radio device could be programmed such that a transmission addressed to one or more of the three talkgroups would be a valid transmission.

57 There are various ways to program a radio’s scanning capabilities. One way in which a radio’s scanning capabilities might be programmed is called priority scanning, which enables the radio to scan important channels more frequently. Automatic scanning, such as priority scanning, can be advantageous because it can take time for a user manually to select channels and users may miss transmissions if they are on the wrong channel. Various systems existed for automatic scanning prior to the priority date for the 355 patent.

Different types of two-way radios

58 Two-way radio systems are generally split into analogue and digital systems. The main difference between them is the way that signals are transmitted and received. Analogue radio systems use electrical signals which, at least conceptually, resemble sound waves to deliver voice audio over an RF. Digital radio systems, by contrast, process sounds into patterns of numbers which are then transmitted over an RF. Digital two-way radios can allow users to transmit data as well as audio. They are also more secure.

59 Early two-way radio systems transmitted voice messages using analogue methods over RFs. Communication was either direct from one terminal to another on a simplex channel, that is, on a single frequency, or it was transmitted between terminals via a repeater on different transmit and receive frequencies.

60 Without the inclusion of the repeater, the coverage of a radio system is dependent on the power of the terminal. Since terminals are often portable and therefore powered by a battery, the power of early terminals was relatively low. However, since early analogue two-way radio systems could be used in both direct mode and repeater mode, that is, with or without a repeater, simple analogue two-way radio systems often included a single repeater to relay communications between connected terminals. The coverage of such a system is restricted by the power of the single repeater. This type of system was very common in Australia before the 1980s.

61 Larger two-way radio systems include multiple repeaters that enable the system to cover a larger area. While this type of system allowed for extended coverage, a problem was that all of the connected repeaters were required for a single transmission. This meant that only one transmission could take place using connected repeaters in the system at a time.

Scanning in analogue two-way radio systems before 26 July 2004

62 Early two-way radio systems required radio users, such as the user of a mobile station in a vehicle, manually to change the channel to scan the system for relevant transmissions. This meant that when a user was moving around they would need to know the channel which was associated with the closest repeater and then select that channel on the mobile station in order to receive the transmission.

63 Automatic scanning functionality was then developed in around the 1980s to allow for users moving between different repeaters to automatically receive communications from different repeaters. In early analogue systems, this was achieved by a list of frequencies, each of which was associated with a different repeater, being saved in the memory of the terminal devices. When set to scan automatically, the terminal device would then step through the list of frequencies and lock onto each to determine if a transmission was taking place.

64 A problem with this automatic scanning methodology, however, was that there was no assessment of signal strength when the terminal device stepped through the list of frequencies. As a result, terminals often locked onto a repeater that was not the closest repeater to them, with the consequence that they had low signal strength.

65 Automatic voting was thus developed to ensure that signal strength was taken into account when a terminal automatically scanned RFs. Automatic voting was similar to automatic scanning in that the terminal would automatically scan through a list of frequencies saved to memory in the terminal. However, automatic voting required the terminal device to assess the signal strength of each frequency stored in memory in the terminal before deciding which frequency, that is, which repeater to lock onto. This type of system often included a control station that was independent of the repeaters. That control station would re-key the repeaters every minute or so to produce a burst of energy for a length of time that was sufficient for each terminal to complete the automatic voting function and record their local site, that is, the local repeater with the strongest signal strength.

66 Techniques were also developed before 26 July 2004 that enabled analogue terminals to automatically scan frequencies for specific types of communications, for example, communications to a specific talkgroup. One example of this kind of technique was what was known as the Code Tone-Coded Squelch System (CTCSS). The CTCSS adds a low frequency tone to a voice communication. Terminals included in their memory a list of CTCSS tones that were associated with, for example, a talkgroup. This enabled the terminals to listen for a specific CTCSS tone. If the tone for a talkgroup which was saved to the terminal’s memory was heard on a channel while it was automatically scanning, then the terminal would stay on the channel. Otherwise, the terminal would continue scanning the other channels saved in its scan list. As we have indicated, the concepts of scanning and staying on a channel are relevant to the 355 patent.

67 A well-known problem with both automatic scanning and automatic voting in early analogue two-way radio systems was the length of time that it took for a terminal to complete the process. This limitation was a physical limitation which was inherent in analogue two-way radio systems. It was caused by the fixed amount of time that it took the terminal to perform the automatic scanning and automatic voting processes because it involved a number of steps. First, the radio would find an RF carrier. Second, using the example of CTCSS tones, although other methods might be used, it would decode the CTCSS in a hardware chip or in software. Third, it would “qualify” the channel and then, if all the relevant criteria were met, it would remain on the channel to start receiving communications. What is meant by “qualify” is that having detected the relevant CTCSS tone, the device had to be sure that it had done so and that what had occurred was not a random appearance of a tone frequency. This is consistent with the explanation that automatic scanning and voting in analogue two-way radios required the device to receive a certain number of radio wave cycles before the device could qualify the radio signal. As a result of the CTCSS tone being of such a low frequency, the time spent scanning and voting was determined by the period of the waveforms. For example, a two-way radio might have to wait for five cycles of the CTCSS waveform before it could complete the process and start receiving transmissions. The primary judge accepted that this problem was a well-known problem prior to the late 1980s. One solution to the problem was to limit the number of frequencies to be scanned.

De-keying and re-keying in analogue two-way radios prior to 26 July 2004

68 Prior to 26 July 2004, analogue repeaters included a hangtimer which prevented a repeater from de-keying immediately after a transmission. This hangtimer ensured that the recipient had sufficient time to respond before the repeater de-keyed. Where a repeater de-keyed it would result in the repeater releasing the downlink frequency to allow for other system users to begin a transmission. When it re-keyed the repeater would, before selecting a frequency upon which to broadcast, check to see that that frequency did not already have a CTCSS tone on it. If it did have such a tone, the repeater would re-key to a different frequency.

Digital two-way radios

69 Digital two-way radios were introduced in around the 1990s. In digital two-way radios, voice (and data) is transmitted using binary digits (bits) over RFs. The use of the binary system allows for error correction embedded signalling and control information to be included in each transmitted packet. Each packet contains an assembly of bits. Digital radios also introduced two other relevant innovations.

70 First, the software in a digital radio contains an algorithm which understands the difference between voice audio and background noise. As a result, unwanted background noise is not transmitted to the radio’s speaker and digital radios provide users with enhanced voice capacity and higher-quality coverage.

71 Second, digital two-way radio technologies introduced the ability to divide single-call RF channels. What is meant by a single-call RF channel is that the frequency is devoted to the carrying of a single communication. In a digital radio communication, the fact that the transmission is made up of packets of data means that with appropriate timing protocols in place, more than one communication can be carried at one time on the same frequency. This means that multiple users could access a single channel at one time. The first digital two-way radio systems were the MPT1327 (analogue voice with digital control messaging), APCO P25 (digital voice and data) and Terrestrial Trunked Radio (TETRA) (digital voice and data).

72 A transmission from a radio user in a digital system comprises two key elements, being the payload and embedded signalling information, which is also known as control information.

Payload

73 Payload is the term used to describe the part of a transmission that contains the substantive communication as opposed to, for example, the control information. It is a type of data that is transmitted in large blocks made up of many bits and usually relates to voice based or data based transmissions. When voice is being transmitted it is typically referred to as voice payload. Similarly, when data is being transmitted it is referred to as data payload.

Embedded signalling (control information)

74 After a process referred to as synchronisation, the receiving station needs to determine what sort of transmission is in progress. This is performed using embedded signalling which is also known as control information. Control information is decoded messages which consist of bits or words, which are groups of bits. These messages give information about certain parts of the transmission. For example, the control message could give information about the payload type by differentiating between voice or data, the source of the transmission, that is, which radio device the message has come from, or the recipient of the message which could be a single radio, a talkgroup or a colour code. Colour codes may be understood as referring to the geographical area covered by a particular base station.

Data frames

75 Control information is contained within what are called data frames. A data frame is the frame in a digital communication system which the bits that are used to carry voice and data are packaged into. A frame is a unit of repeating structure and typically includes a specific number of bits. Bits relating to specific functions, for example, the payload, frame synchronisation, and control messages, are assigned a specific location within a frame. A set frame structure is important as the receiving device needs to be able to decode the bits within a frame. For example, the receiving device needs to know which series of bits provide the payload portion of the received frame.

Frame synchronisation

76 In order for these data frames to be transmitted, the sending and receiving stations must be in synchronisation. Synchronisation is important for what are referred to as multiple access communications systems. The present matter is concerned with such systems.

77 Synchronisation is important in multiple access communications systems because the receiving device needs to determine which portion of the data on an RF is intended for that receiving device. When in use, a receiving device receives a constant stream of bits during the digital transmission. Frame synchronisation enables a receiving device to differentiate between the different portions of the constant stream of data so that it can determine the portion of the data that corresponds to the payload. In a data frame, if different groups of bits are assigned for different purposes, the receiving device must be able to know which part of the stream it is looking at. If a data frame is 216 bits in length, for example, and the first bit of the frame signals some particular meaning such as whether the channel is active, then this meaning will be lost if the receiving device does not know where the frame starts.

78 To enable frame synchronisation, digital terminal and repeater devices include a crystal. The crystal is an electronic element made from quartz crystal which is used to generate an internal timing reference like an internal clock. The purpose of frame synchronisation is to synchronise the internal clock of the receiving device such as a terminal with the internal clock of the transmitting device such as a repeater. The purpose of this clock synchronisation is so that the receiving device is then able to recognise the start and end of the data frames. Once the receiving device knows this, it can locate specific portions of the incoming data within each frame.

79 To synchronise with a transmitting device, a receiving device locates what is known as a synchronisation pattern or synchronisation word. A synchronisation pattern or synchronisation word is a known data sequence that is transmitted at certain times or intervals during a transmission. This synchronisation pattern is a series of bits that form a word and is a specific sequence of 1s and 0s that the receiving device will recognise. The two devices do not need to have been synchronised in order for the synchronisation pattern to be recognised. That is, the synchronisation pattern can be transmitted asynchronously.

80 Recognition of the synchronisation pattern allows for frame synchronisation between a receiving and transmitting device. Typically, the synchronisation pattern is located at the start or the middle of the data frame. Once a device locates the recurring synchronisation pattern, which is recurring because it is located in each repeating frame, the receiving device is able to determine where the pattern is in the data stream and is then able to decode the incoming frames to obtain relevant information.

Frame synchronisation in repeater mode

81 Terminals operating in repeater mode, that is, where they are communicating through a repeater, synchronise to the reference timing set by the repeater. The repeater sets the reference timing, being the timing of the repeating frames, and as such, the timing of the synchronisation patterns. This ensures that all of the terminals that are connected to the repeater are working to the timing reference and are synchronised to the repeater without conflicting with one another. This is important where multiple channels are included on the one frequency. Communications which are received out of synchronisation are ignored by a repeater unless the signal is a wake-up message.

82 Terminals can lose synchronisation for a variety of reasons. A loss of signal is generally referred to as a signal drop-out or a loss of carrier. Drop-outs can be short such as a few milliseconds, or long such as several seconds. Longer drop-outs may occur when the terminal moves too far away from the repeater or during periods of interference, such as when a terminal moves underground or under a bridge and is unable to maintain a signal with the repeater.

83 A phenomenon referred to as “Rayleigh fading” causes short term drop-outs in two-way radio systems. Fading may occur due to radio waves reflecting off buildings or other objects which cause an interference to radio signals. In this circumstance, signal strength may drop down to zero and then return very quickly, say, within milliseconds.

84 In digital two-way radio systems, terminals communicating in repeater mode may temporarily maintain data synchronisation or reference timing during short periods of interference. But this is typically a short period of time because the reference timing being maintained by the terminal will begin to drift from the timing which was being provided by the repeater before the interference occurred. The period of time that a terminal is able to maintain frame synchronisation for when there is an interference is dependent on a range of factors including the quality of the terminal’s hardware such as the crystal. For example, the period of time for which a terminal is able to maintain adequate frame synchronisation may be less than one second. When the period of interference ends and the terminal again receives data from the repeater’s downlink including the synchronisation pattern, it will adjust its timing, if required, to ensure that synchronisation with the repeater remains in place.

85 The eventual drift between a terminal’s reference timing and the repeater’s timing means that after a period of time without receiving transmissions from the repeater, the terminal may then need to resynchronise with the repeater once again to receive and transmit data.

Examples of systems using frame synchronisation

86 An example of a two-way radio system that includes frame synchronisation is a system called APCO P25. In P25 systems, a special sequence of 48 bits (a synchronisation pattern) is located at the beginning of a frame. In a P25 system, frame synchronisation occurs at the beginning of every message and is inserted every 180 msec throughout the voice message. MPT1327 devices also rely on frame synchronisation in order to decode messages. In TETRA systems, the repeater sends out frames in a repeating structure at constant intervals. The receiving device recognises that the synchronisation pattern is being received at every interval and will set its own clock to match the intervals of the synchronisation pattern. The terminal can then decode the incoming data frames to obtain relevant information such as the control information or payload. Also inbuilt into the system is a feature that is called forward error correction which is designed to compensate for a small percentage of lost data stream, which can occur if the user goes out of range.

Scanning in digital two-way radio systems

87 P25 terminals are able to automatically scan frequencies in a conventional two-way radio system. Transmissions between repeaters and terminals include embedded control messaging that allows for the late entry into conversations, such as talkgroup conversations, by scanning terminals.

88 TETRA terminals also automatically scan. However, TETRA terminals scan control channels rather than traffic channels. This occurs periodically to determine if a control channel with an improved signal strength can be identified. Prior to 26 July 2004, being one of the priority dates, the length of time it took to automatically scan frequencies in analogue systems was a well-known problem. Prior to that date, the known digital two-way radio systems provided little improvement on the length of time it took to automatically scan frequencies.

De-keying and re-keying in digital two-way radios

89 Similar to analogue repeaters, digital receivers have a hangtimer which prevents the repeater from de-keying immediately after a transmission. This ensures that the receiving user has sufficient time to respond to a communication before the repeater de-keys.

90 In conventional digital two-way radio systems, repeaters require a wake-up message in order to re-key. The repeater’s uplink continues to monitor the frequency so that the repeater is able to receive transmissions from terminals. This allows terminals to transmit a wake-up message to the repeater, enabling it to re-key. Although the specific type of wake-up message differs between two-way radio systems, every digital system will look for a valid transmission in order to successfully re-key.

91 Terminals are able temporarily to maintain data synchronisation or reference timing during short periods of interference. A short period of interference has the same effect as a condition where a repeater initially de-keys. In both circumstances, the terminal will no longer receive any data from the repeater’s downlink. As such, in both circumstances, the terminal will temporarily maintain data synchronisation without requiring data such as the repeating synchronisation pattern to be received from the repeater’s downlink.

92 An issue which exists in conventional digital two-way radio systems is that communications could be lost when a repeater’s downlink is initially deactivated. This can occur because of the inability of a receiving terminal to maintain reference timing in a temporary data synchronisation state. When this occurs, it is possible that the terminal transmitting a communication may not recognise that the repeater has de-keyed. This presents an issue because the terminal may continue to transmit communications which are then not repeated to the intended receiver.

Multiple access methods

93 There are three well-known and generally accepted methods implemented to utilise the limited RF spectrum more efficiently in two-way radio wireless communications. These methods aim to increase the number of users communicating within a specific portion of the radio spectrum. They are:

(a) frequency division multiple access (FDMA);

(b) as described above, time division multiple access (TDMA); and

(c) code division multiple access (CDMA).

94 CDMA was not used for two-way radio systems before 2004 and was instead used in cellular telecommunications systems.

FDMA

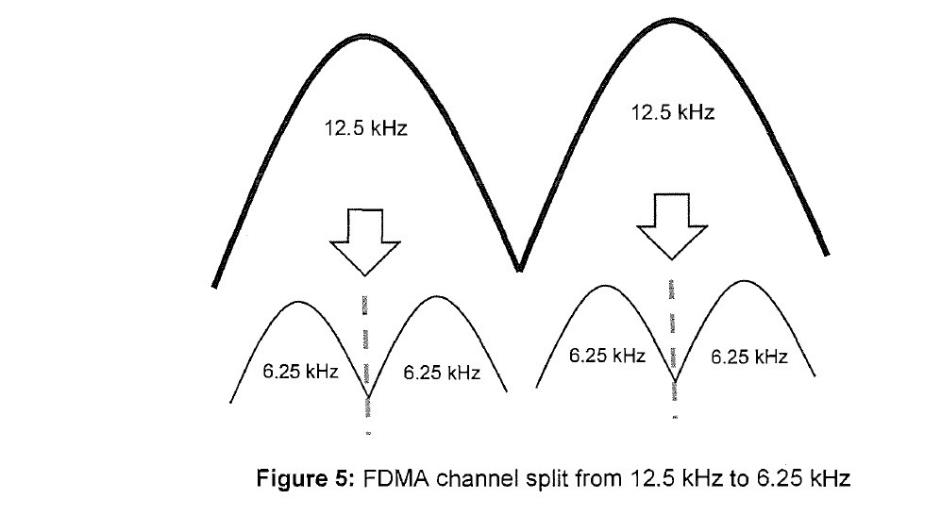

95 FDMA separates RF channels by frequency. For instance, for two-way radio communications, FDMA may split a 12.5 kHz channel into two, smaller, 6.25 kHz channels on which communications can each be transmitted. FDMA was introduced into digital two-way radio systems in the 1990s. It has been implemented into both digital and analogue two-way radio systems such as the P25 digital radio system. An illustration of FDMA channel splitting given by the primary judge is the following:

96 Using FDMA, a conversation occupies a whole channel exclusively, meaning there is one user and one conversation at a time per channel. To increase the number of channels it is necessary to increase the number of frequencies. However, it can be difficult and costly to obtain channel assignments from the regulator. For example, using FDMA, four users each of whom wishes to communicate at the same time would need access to four 6.25 kHz channels, which would be split from the two 12.5 kHz channels.

TDMA

97 TDMA was introduced in or around 1979 as a common multiple access technique for wired networks. It was first introduced to digital two-way radio systems in the 1990s and is still currently implemented into digital two-way systems. TETRA was the first system to implement TDMA in two-way radios.

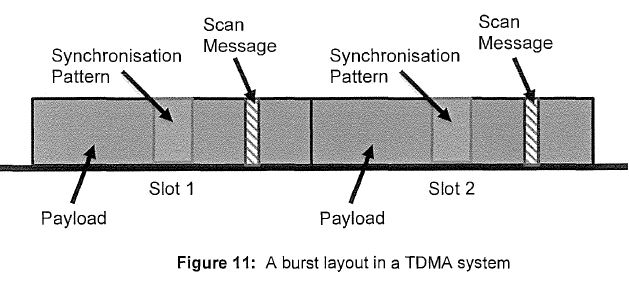

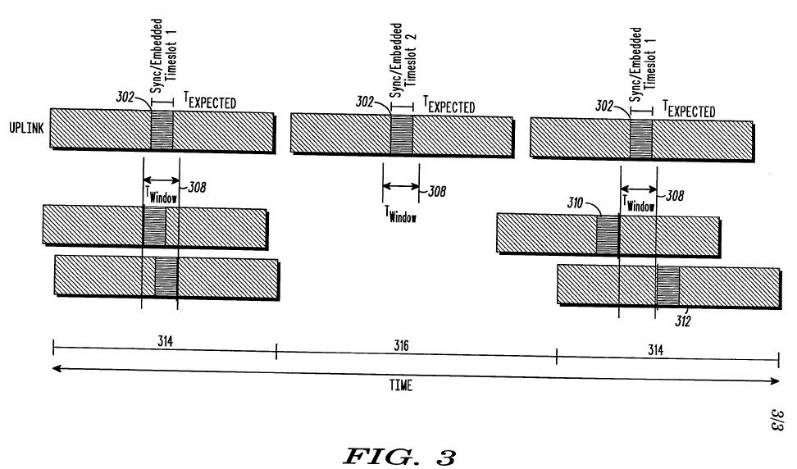

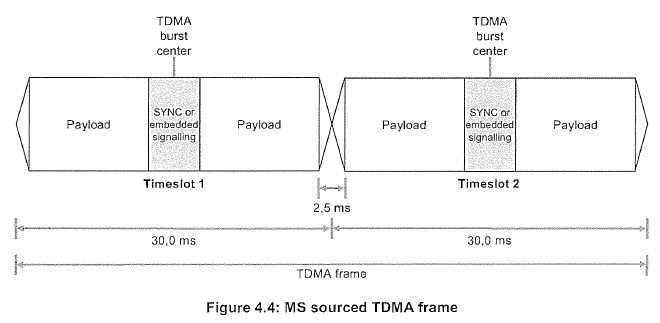

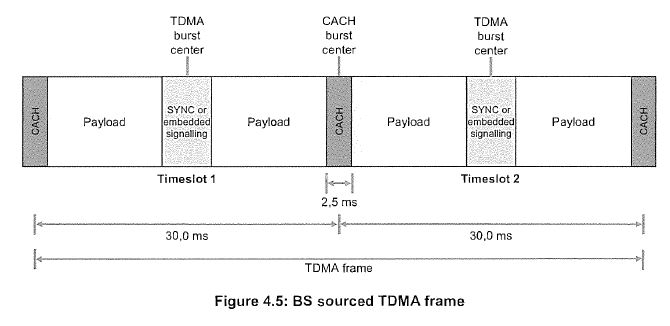

98 TDMA separates RF channels into different timeslots while preserving the width of the 12.5 kHz channel. Timeslots are a defined period of time, usually a very short period of time, during which the sender’s communication is transmitted. TDMA allows several users to share the same channel. As a user transmits, their communication will be inserted into a timeslot of a very short, fixed period such as 50 msec or one twentieth of a second. Usually, a mobile station operating in repeater mode will be allocated to a timeslot by a repeater whereas a mobile station operating in direct mode is able to transmit in a free timeslot which is available on the frequency.

99 Users transmit in rapid succession which gives each user the impression that they have exclusive use of the channel and that their communication is being broadcast in real time. For example, in a two-timeslot TDMA system, two users can share one frequency at the same time. The distinction between FDMA and TDMA systems was illustrated by the primary judge using the following diagram:

100 In a TDMA system, User 1 utilises the frequency for the first timeslot (slot 1 in the above diagram) then User 2 transmits for the next fixed period of time (slot 2). The channel then reverts back to User 1 who transmits for the next fixed period of time. The channel then reverts back to User 2 who transmits for the next time period and so on. The process occurs so quickly that neither user is aware that they are sharing a channel and neither experiences a delay in transmission. However, if more than two users wish to transmit, additional radio channels are needed. For example, in a two-timeslot TDMA system, four users who wished to communicate at the same time would require two 12.5 kHz frequencies.

101 TDMA introduced the ability to divide the physical channels (e.g. the 12 kHz channel) into logical channels. A logical channel is a channel which has the appearance and functionality of a channel but which is, at a technical level, actually made up of quite different constituent elements. For example, a user could select a logical channel designated as channel 1. This logical channel consists of one slot on the transmit frequency and a corresponding slot on the receiving frequency. Although the communication is happening over two frequencies, those two frequencies constitute, so far as the user is concerned, a channel called 1.

102 A half-duplex radio device cannot transmit and receive at the same time. However, using TDMA, such a device can constantly tune between the transmit and receive frequencies which has the effect of simultaneously transmitting and receiving for the user. This is possible for mobile stations operating in either repeater mode or direct mode.

B.3 Well-known digital radio systems before 26 July 2004

103 At this point we will identify various digital radio systems used before 26 July 2004, being the priority date of the 355 patent, as they are relevant to some of the issues that we will address concerning common general knowledge.

The MPT1327 standard and systems

104 One of the first trunked two-way radio systems was the MPT1327 standard. This is a standard which was developed by the United Kingdom Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications in the mid-1980s. It is a hybrid digital/analogue radio communication system in that it transmits both data to set up a call and analogue voice communications. It includes a trunked system controller that retains information including a list of terminal devices that are subscribed to the network, a record of the location of the terminals subscribed to the network, and the configuration of repeaters connected to the network. Each repeater in the network is connected to the traffic system controller with several cables, including a data cable for the dedicated control channel and physical cables for each of the repeaters that have traffic channels. MPT1327 systems include sites that each typically include several connected repeaters. One of the repeaters in each site operates as the dedicated control channel and the remaining repeaters are associated with the traffic channels.

105 Terminals connected to an MPT1327 network communicate with the dedicated control channel in order to set up and receive calls. Unless the system includes a time shared control channel, system users are typically allocated a traffic channel on the site that they are connected to in order to communicate with another system user. In a time shared MPT1327 system, the control channel can also be allocated as a traffic channel.

106 Terminals in an MPT1327 system automatically scan the control channels associated with repeaters in the network on a regular basis to determine if a site with increased signal strength is able to be located. To enable the automated scanning process, the terminals include a list of frequencies associated with control channels as well as associated repeater identifications in the network that are saved to memory in the terminal.

107 MPT1327 terminals typically included more frequencies saved to the memory to which the terminal is subscribed.

108 The repeater associated with the control channel for each site transmits control messages on the control channel to perform an action, such as setting up calls. The control messages included information such as the identification of a source terminal, the identification of a talkgroup, the identification of a site and the identification of a repeater. The primary judge set out in some detail the various types of control messages used. We do not need to set out that detail for present purposes.

109 MPT1327 used fast frequency shift keying to transmit data over the control channel. Such shift keying implements a technique that allows for digital data to be transmitted using an analogue signal. An electromagnetic carrier wave is used to carry the digital data over a distance and connect repeaters with terminals in remote locations. In such shift keying, the repeaters transmit data on the control channel by modulating the carrier frequency between two discrete values. Each of the discrete values correspond to a zero or a one. The terminals are able to receive and decode the digital data corresponding to control messages then perform the desired functions.

110 MPT1327 terminals are not able to communicate with each other in direct mode but use repeaters to transmit. Similar to conventional analogue two-way radio systems, the repeaters in trunking two-way radio systems such as MPT1327 de-key when the downlink associated with the repeater is not in use. At the end of a transmission, terminals leave the traffic channel that was being used for a communication. A message is then sent to the traffic system controller, indicating that the conversation is complete. After certain conditions are met, such as after the expiration of a timer, the traffic system controller sends a message to the repeater associated with the traffic channel that is no longer in use and instructs the repeater to de-key.

APCO P25 standards and systems

111 APCO P25 is a set of digital two-way radio standards that were produced by the Association of Public Safety Communications International in the United States in the 1990s. P25 is an open architecture that defines a digital radio communications system for public safety organisations. P25 was implemented by various manufacturers and organisations including Motorola. The P25 standards define the interfaces, operation and capabilities of P25 radio systems.

112 Before 26 July 2004, P25 systems were both conventional and trunked digital two-way radio communication systems that transmitted data using FDMA methods. These systems are now referred to as “Phase 1 P25”. Phase 1 systems operate using a 12.5 kHz frequency bandwidth and use Continuous 4 Level FM, a type of frequency shift keying modulation to transmit data. P25 systems implement a vocoder to encode speech into a digital data stream.

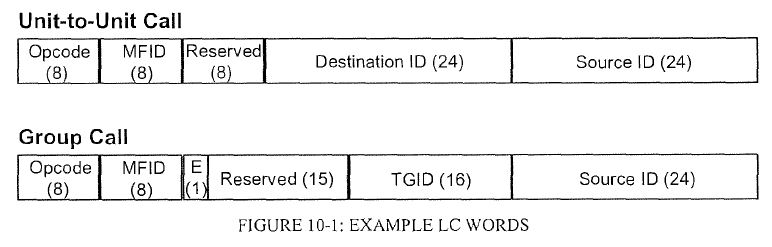

113 P25 transmissions include a link control (LC) message that forms part of voice transmissions to provide signalling information to terminals. The LC message is referred to as an LC word. Examples of LC words are shown in the P25 standards and include a message to specify the LC word’s content (LCF), the manufacturer’s identification (MFID), the talkgroup identification (TGID), the source identification (Source ID), the destination identification (Destination ID), and an emergency indicator.

114 P25 terminals are able to automatically scan frequencies that are saved to memory in the terminals. P25 transmissions between repeaters and terminals included embedded control messaging that allowed for the late entry into conversations by scanning terminals.

115 A sequence of bits provides frame synchronisation which allows for the messages which follow to be decoded. For P25 transmissions, frame synchronisation messages are located at the start of every voice and data transmission and within transmissions, which are spaced at 180 msec intervals as provided for in the P25 standards, to allow for late entry by terminals. Once a terminal has synchronised to a transmission, it is then able to determine if the transmission is relevant by interrogating the LC message, that is to say, the LC word. This might occur to determine if an LC message indicates that the transmission is for a talkgroup to which the scanning terminal is subscribed.

116 The LC word is included in the Logical Link Data Units (LDU1 and LDU2) that are transmitted during a voice call. In order to receive LDU1 and LDU2 while scanning, a P25 terminal needs to decode all of the data being transmitted, including the data associated with the error correction algorithm. This was a known limitation with P25 systems and meant that it was slow to lock onto a channel.

117 An additional associated limitation with P25 systems was that a P25 terminal required several messages within a data stream to be decoded and then interrogated for the required information. So, automatically scanning for incoming transmissions in a P25 system was a slow process as terminals were required to decode large parts of the data stream and perform error correction of the data to allow the terminal then to interrogate the data stream for conditional requirements before locking onto a particular channel. If the transmission was a voice call, most of the packets of data were allocated to the payload being transmitted and the address information would only be transmitted every ninth frame, which was every 180 msec. This meant that terminals needed to wait until the relevant information was received and decoded before the terminal was able to make a decision with respect to remaining on a channel. As a result, P25 did not provide much improvement to the well-known scanning problem with reference to analogue systems. This was a well-known limitation of P25.

118 P25 two-way radio systems can be used in conventional direct mode and repeater mode. Terminal devices also may include a button that allowed for users to toggle between the different modes. Similar to conventional analogue two-way radio systems, the repeaters in P25 systems keyed and de-keyed when the downlink associated with the repeater was not in use such as when the talk channel is released. Also, similar to conventional analogue two-way radio systems, the repeaters in P25 systems on occasion included a timer to prevent the repeater from de-keying immediately after a transmission.

TETRA

119 TETRA is a digital trunking system that was standardised by ETSI in the mid-1990s. It was first introduced commercially in the early 2000s. TETRA is a digital system that implements TDMA to transmit communications between terminals and repeaters. Each TDMA frequency of 25 kHz is separated into four timeslots to allow for several communications to take place on a single frequency.

120 TETRA systems implement a vocoder to encode speech into a digital data stream. TETRA terminals are able to communicate directly with one another, without using a repeater. This is referred to as direct mode operation. Devices which implement TETRA perform frame synchronisation to transmit communications.

121 TETRA is similar to MPT1327 in that it includes a dedicated control channel. But unlike MPT1327, because the system implements TDMA, a single repeater can be used for both a control slot and multiple talk slots. This means one timeslot can be used to communicate control messaging and the remaining timeslots can be used to communicate voice and data between terminals. TETRA implements a form of phase-shift keying (differential quadrature phase-shift keying) to transmit data between connected repeaters and terminals. Phase-shift keying is a method of conveying data by modulating the frequency. It is not necessary here to explore the nature of phase-shift keying. However, similar to MPT1327, the repeater associated with the control channel for each site transmits on the control slot to perform actions such as setting up calls. As also occurs in MPT1327, the control messages include information such as the identification of a source terminal, the identification of a talkgroup, the identification of a site, and the identification of a repeater.