Federal Court of Australia

Seven Network (Operations) Limited v Greiss [2024] FCAFC 162

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 11 DECEMBER 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The cross-appeal be dismissed.

3. Order 1 made on 20 February 2024 entering judgment in favour of the applicant and Order 1 made on 16 April 2024 as to costs be set aside and in lieu thereof order that proceedings NSD 292 of 2022 be dismissed with costs.

4. The respondent pay the appellants’ costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY

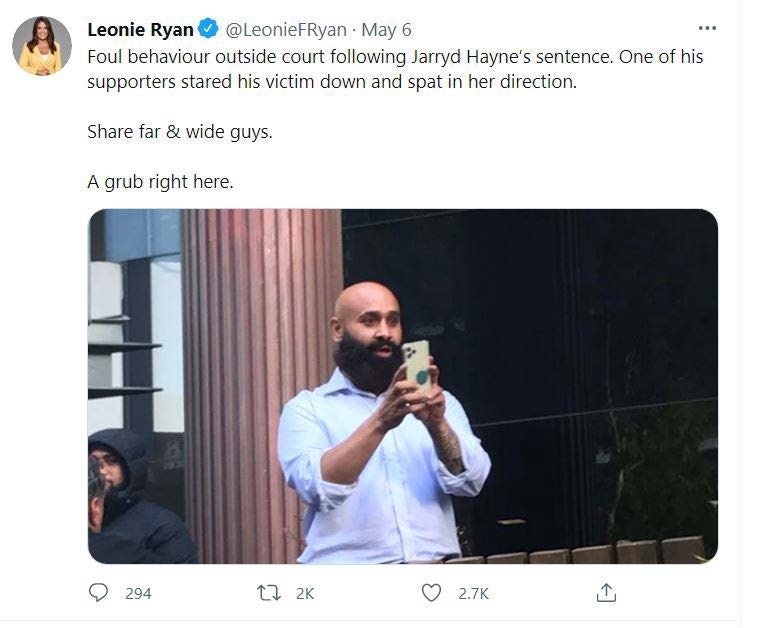

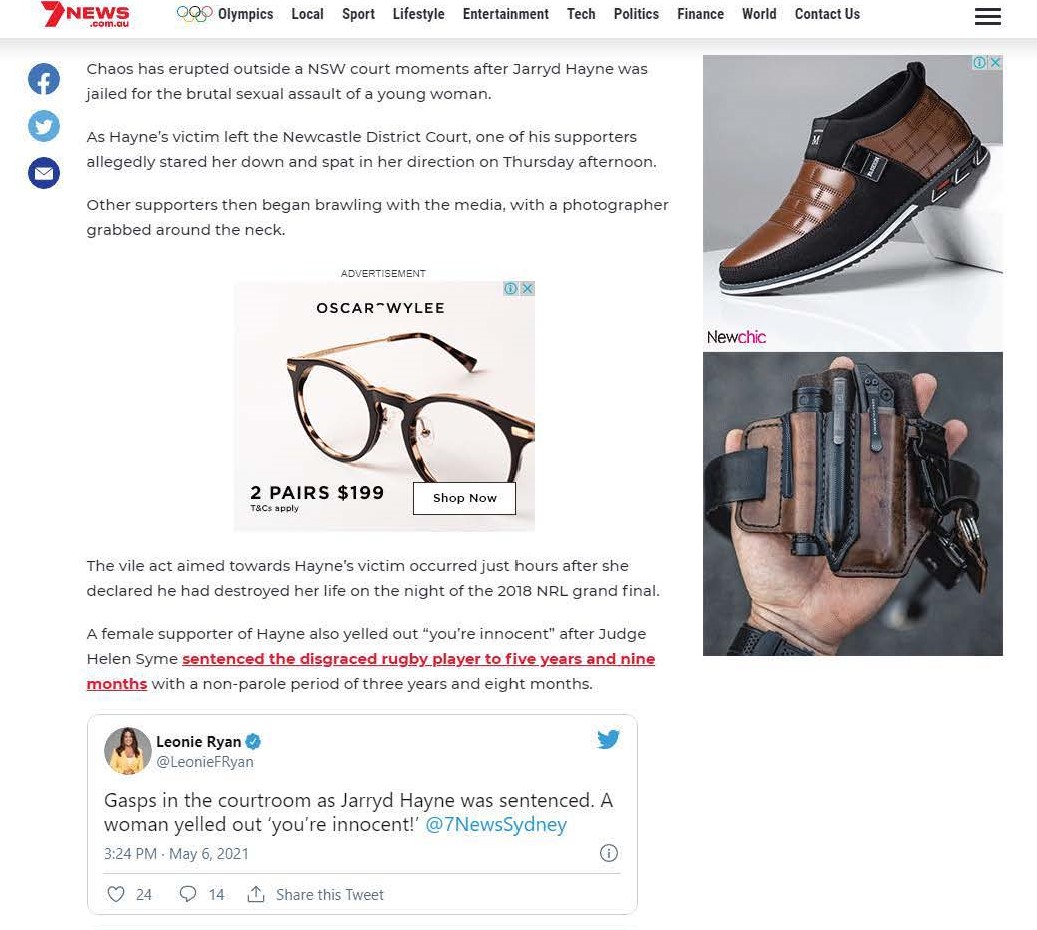

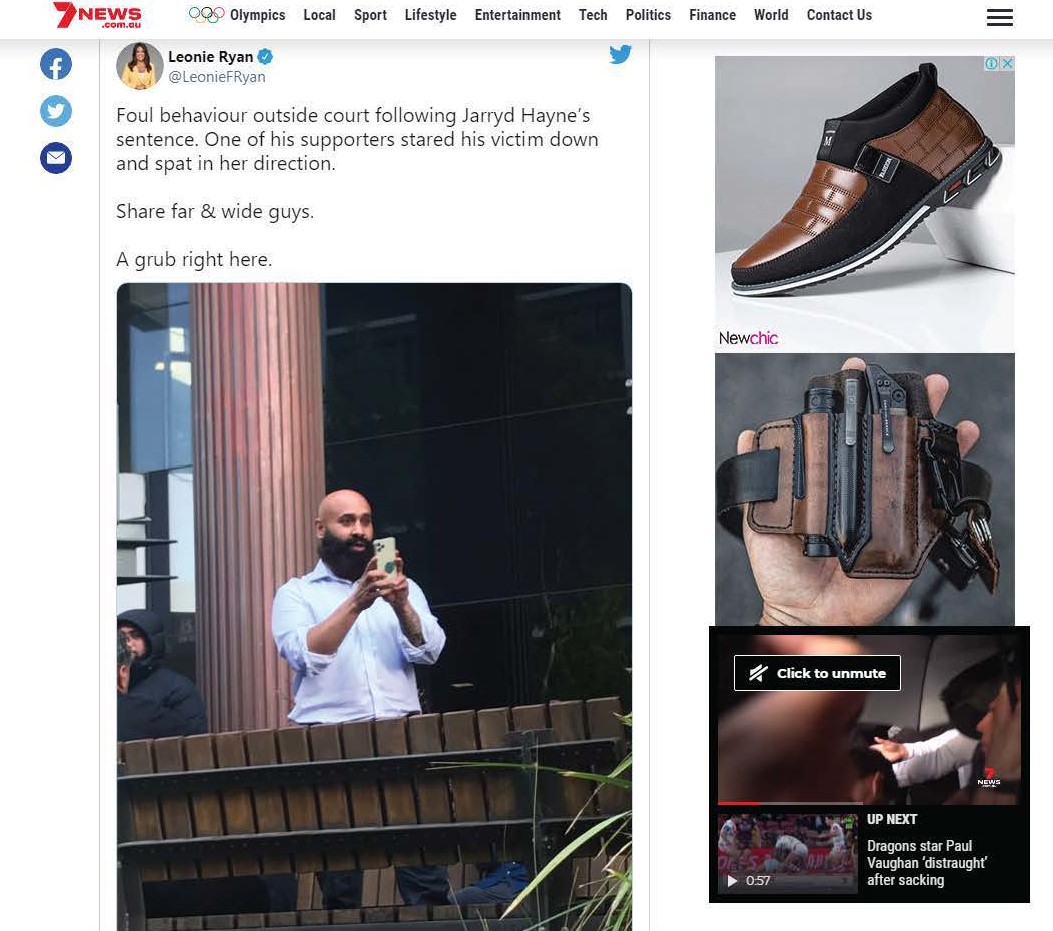

1 This is a defamation appeal in relation to a judgment whereby the respondent, Mr Greiss, recovered the modest sum of $37,940 plus an award of costs against the appellants: Greiss v Seven Network (Operations) Limited (No 2) [2024] FCA 98 (primary judgment or PJ). Although the appellants published three matters being an Article, a Facebook post and a Tweet (which, for convenience, are set out as annexures to these reasons), they were only found liable in relation to the publication of the second matter, the Facebook post.

2 The genesis of the controversy arose from Mr Greiss attending the District Court of New South Wales in Newcastle supporting Mr Jarryd Hayne, who was being sentenced following his conviction for criminal offences (a conviction that was subsequently set aside by the Court of Criminal Appeal of New South Wales). Mr Greiss and other supporters of Mr Hayne left the courthouse and stood together within a courtyard to the right of the entrance. About five minutes later, the primary Crown witness (who I will describe as the complainant) emerged from the building, escorted by two sheriff’s officers and others, apparently detectives and the Crown prosecutor. As the group left the building, they turned right and walked down a ramp. When Mr Greiss noticed the group leaving, he rose from his seat and walked towards the ramp, positioning himself at the top of a small staircase which led to the ramp. He looked at the group and noticed that it included the complainant (see PJ [8]–[9]).

3 What thereafter occurred was controversial at trial.

4 Following a lengthy trial and an exhaustive review of the evidence, the primary judge (at PJ [201]–[202]) made several central findings as to what occurred (central findings) in the course of rejecting aspects of the evidence given by Mr Greiss. These were:

(1) Mr Greiss’s attention was focussed on the complainant from the moment he stood up to the moment the complainant left the court precinct;

(2) Mr Greiss stared at the complainant;

(3) Mr Greiss pointed at the complainant;

(4) At the time Mr Greiss’s head made a downward motion on the CCTV, he spat;

(5) Mr Greiss spat in the direction of the complainant;

(6) Mr Greiss intended for his spit to be a sign of disgust and contempt for the complainant;

(7) Mr Greiss called the complainant an escort on two separate occasions and urged the media to publish this allegation;

(8) Mr Greiss intended to harm the complainant by calling her an escort;

(9) The conduct referred to in 1 to 8 above was disgraceful; and

(10) Mr Greiss spoke with a raised voice that was loud enough to attract the attention of the woman walking beside the complainant (and was not speaking quietly, just asking the sheriff a “simple” or “harmless” question or having a polite conversation with the sheriff).

5 The primary judge also found, and it was not in dispute, that the Facebook post carried the following imputations (at PJ [44]):

(1) Mr Greiss spat at a rape complainant outside court; and

(2) Mr Greiss is despicable, in that he spat at a rape complainant outside court.

6 Despite the central findings, including those findings identified above (at [4(2)] to [4(6)]), the primary judge rejected a justification or substantial truth defence pleaded in answer to the defamatory imputations published by the Facebook post. The rejection of this defence is the subject of Ground 1(a)–(d) of the appeal.

7 For reasons I explain below, at least parts of this ground of appeal have merit and the primary judge’s orders, including an order for costs, premised upon the partial success of Mr Greiss below (Greiss v Seven Network (Operations) Limited (Costs) [2024] FCA 377 (costs judgment)), must be set aside and, in lieu thereof, an order be made the proceedings be dismissed with costs.

8 In the light of this conclusion, one might be forgiven for thinking that the appeal could be dealt with very briefly, but regrettably this is not the case. A cross-appeal (CA) has been filed which overlaps with an extensive notice of contention (NOC). Not only does the consideration of Ground 1 require evaluating a challenge made by Mr Greiss to the central findings, but the primary judge’s conclusion that the Article and the Tweet were defensible is impugned, for a variety of reasons, including a practice and procedure decision allowing an amendment to the defence. Further, challenges are made to the primary judge’s findings concerning ordinary and aggravated compensatory damages.

9 It is necessary to organise all these issues in some logical way, and it follows that the balance of these reasons are divided as follows:

B THE ATTACK ON THE CRITICAL FINDINGS (CA 2, 3, 4 and NOC 1, 2, 3);

C SUBSTANTIAL TRUTH OF THE FACEBOOK POST (Appeal 1(a)–(d));

D THE AMENDMENT ISSUE (CA 1);

E CONTEXTUAL TRUTH: THE ARTICLE AND THE TWEET (CA 5);

F HONEST OPINION (CA 6) & OTHER MATTERS (Appeal 1(e)–(i) and 2; NOC 4 and 5);

G COSTS AND ORDERS.

10 As will be seen, to the extent they are necessary to resolve, the issues raised by the CA and the NOC do not affect the conclusion that the appellants’ success on at least parts of Ground 1(a)–(d) is determinative of the appeal.

B THE ATTACK ON THE CRITICAL FINDINGS (CA 2, 3, 4 AND NOC 1, 2, 3)

11 Mr Greiss challenges the central findings in circumstances where the primary evidence of what occurred at the Newcastle Court House is CCTV footage and the video is tolerably clear. Although the Full Court is in as good a position as the primary judge to consider that aspect of the evidence, our task is to discern error and, in particular, to consider whether it was open to the primary judge to make the findings her Honour made based upon the whole of the evidence, including admissions and contemporaneous representations.

12 Mr Greiss accepts that the finding he spat towards or in the direction of the complainant relied, in part, on the primary judge’s acceptance of the evidence that during a subsequent altercation with the second respondent (a journalist, Ms Leonie Ryan), Mr Greiss said to her: “Yeah I did spit”, in response to Ms Ryan accusing him of spitting towards the complainant. A friend of Mr Petras (who was next to Mr Greiss at the relevant time) also made a representation that was adduced in evidence that: “he [that is, Mr Greiss] spat on an escort” (at PJ [280]–[303]).

13 Mr Greiss submits, however, that such material must be “reconciled” with the CCTV footage, with the most obvious alleged difficulty being that Mr Petras’s representation that Mr Greiss spat “on an escort” (at PJ [118]) could not “be understood literally”. Although the primary judge described the contents of the CCTV footage (at PJ [99]–[110]), it is asserted that her Honour made little reference to it in her findings about the principal issue of whether Mr Greiss spat at, towards, or in the direction of the complainant.

14 The Full Court was taken to the footage including what was said to be the “key moment”, when her Honour found that Mr Greiss spat into a garden bed facing Hunter Street (at PJ [105]). Mr Greiss submitted that, on any view, when the spit occurred the complainant was well away from Mr Greiss and the spittle went into a garden bed.

15 Additional complaints are made that: (1) it was wrong for the primary judge to accept the inferences Mr Greiss said should be drawn from the CCTV footage on the basis that no view at the Newcastle Court House was undertaken and there was no opinion evidence directed to measurement of relevant distances; and (2) insufficient weight was given to two witness statements, made by two sheriff’s officers who stated that the complainant left the area without incident and that there “was no interaction with her and the HAYNE group” (at PJ [192]– [194]).

16 In the end, however, the primary submission is that because the complainant was some metres away from Mr Greiss when he expectorated and because he had turned towards the street and spat into a garden bed, there was no sensible way to regard the action as spitting “towards” or “in the direction of” the complainant.

17 There is no error demonstrated.

18 The primary judge’s central findings demonstrate an engagement with all the evidence including, critically, the CCTV footage and the evidence initially given by Mr Greiss (and rejected) that he did not spit. In this regard, it is worth noting that the alternative submission that Mr Greiss spat in the garden bed (which received such emphasis on appeal) was only ever advanced below in the alternative to his unmeritorious denial (see PJ [206], [211], [270]).

19 Although it may be accepted the CCTV footage is consistent with a conclusion the complainant was some metres away from Mr Greiss, and the spittle went into a garden bed, the straightforward answer to Mr Greiss’s submission is that this conclusion is not inconsistent with a finding Mr Greiss spat towards or in the direction of the complainant intending his action to be a sign of disgust and contempt for her. One can spit “towards” or “in the direction of” someone while being unable to physically convey the saliva expectorated to the body of the object of one’s disgust or contempt.

20 Moreover, to the extent it matters, there was ample other evidence to support the finding Mr Greiss spat towards or in the direction of the complainant including: (1) the contemporaneous representations made by Ms Ryan and Ms Tiffiny Genders (another journalist) (at PJ [105], [109], [126], [131], [141], [145]–[148]); (2) the admissions of Mr Greiss (at PJ [118]–[119], [180], [299]–[300], [430]); and (3) the contemporaneous statement by Mr Petras – who was not called – referred to above (and the related finding that Mr Greiss did not correct Mr Petras (at PJ [118]–[119], [269], [292], [296], [299])).

21 Mr Greiss’s further submission that the representation of Mr Petras that Mr Greiss “spat on a [sic] escort” could not be understood literally goes nowhere. As the appellants correctly submit, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it was open to the primary judge to conclude that Mr Petras’s use of simple language reflects the finding that the spitting action “was an expression of [Mr Greiss’s] attitude towards the [complainant] and that it was directed at, or intended to represent his contempt for, her” (at PJ [269]).

22 As to the submissions in relation to the two sheriff’s officers, Mr Weaver and Mr Marsay, the issue of weight was quintessentially an issue for the trial judge and it was open for her Honour to approach these representations, by witnesses not called in the case, with a degree of circumspection for the reasons given.

23 The evidence for her Honour’s findings was overwhelming and is not undermined by her references to a view or alternative evidence Mr Greiss could have adduced. There is no reason to think that the primary judge made the basic error, described in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hellicar [2012] HCA 17; (2012) 247 CLR 345 (at 412–413 [165]–[167] per French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ), of deciding a disputed question according to speculation about what other evidence might possibly have been led rather than the evidence the parties adduced.

24 The attack on the primary judge’s central findings fails.

C SUBSTANTIAL TRUTH OF THE FACEBOOK POST (APPEAL 1(A)–(D))

25 The reason why the primary judge did not consider the substantial truth defence to be made out as to the Facebook post, despite her finding Mr Greiss “spat towards” and “spat in the direction of” the complainant (at PJ [305]) was: first, based on an apparent rejection of the submission of the appellants for the purposes of the substantial truth defence, the words “spat at the complainant” were the same in substance as “spat towards” and “spat in the direction of”, the complainant; and secondly, appears to be based upon the fact that “Ms Ryan conceded that it was false to say that Mr Greiss spat at the [complainant]” (at PJ [305]).

26 As to the first of these matters, as the appellants correctly submitted below, the spit was intended for the complainant and the “issues of distance and proximity between Mr Greiss and the rape [complainant] are of peripheral relevance to what Mr Greiss, Mr Petras and the media witnesses all understood on 6 May 2021 at the time Mr Greiss spat as the complainant walked past – the point is it was directed at the rape [complainant]” (appellants’ closing submissions (at [46]–[57], [58]–[71])). The justification defence is one directed to substance, not form or literal truth. The conclusion the spit was for the complainant or directed to her is sufficient to justify the substantial truth of the imputations. Mr Greiss spat at a rape complainant outside court. The conduct of Mr Greiss was disgraceful rightly characterised by the primary judge as, and hence the further imputation that the conduct of Mr Greiss was despicable, in that he spat at a rape complainant outside court, was also justified as a matter of substantial truth.

27 As to the second, it is a little unclear as to whether the primary judge determined the meaning of the words “spat at the victim” by reference to Ms Ryan’s subjective belief evident from the following exchanges in cross-examination (T218.8; T221.1–3):

MS CHRYSANTHOU: And it’s false to say, don’t you agree, that he spat at her?---That’s true.

…

MS CHRYSANTHOU: Do you accept that if you had told anyone else Channel 7, either Mr Morrison or Ms Dallimore or Mr Tiernan, that my client spat at the victim, that would not have been accurate at the time?---I would agree.

28 If in fact her Honour did so, this would constitute error, as Ms Ryan’s understanding was as irrelevant to meaning as the subjective views of others (such as Ms Genders or Mr Petras) who evidently had a different view. What matters, of course, is what meaning was conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader based on the natural and ordinary meaning of the publication alone. It is unnecessary to form a final view as to whether this was what her Honour was doing, because acceptance of the appellants’ first argument (identified in Ground 1(b) to (c)) is made out.

D THE AMENDMENT ISSUE (CA 1)

29 This assertion of error in allowing an amendment has no merit as an independent ground of appeal. As it was developed orally, it became largely indistinguishable from the errors alleged in the way the primary judge dealt with the contextual truth defence, which had been introduced by the impugned amendment.

30 There was no recognisable error in the way the primary judge dealt with the amendment application, and none was really identified, and no prejudice was demonstrated (other than the irrelevant one of facing an arguable defence).

E CONTEXTUAL TRUTH: THE ARTICLE AND THE TWEET (CA 5)

E.1 Introduction

31 The substance of the contextual truth defence upheld by the primary judge in relation to the Article and the Tweet is a more substantive point and requires extended consideration.

32 At the material time, s 26 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Defamation Act) provided that:

It is a defence to the publication of defamatory matter if the defendant proves that—

(a) the matter carried, in addition to the defamatory imputations of which the plaintiff complains, one or more other imputations (contextual imputations) that are substantially true, and

(b) the defamatory imputations do not further harm the reputation of the plaintiff because of the substantial truth of the contextual imputations.

33 As the primary judge noted (at PJ [308]), the effect of the section is that a respondent can defeat an action in defamation “if its substantially true contextual imputation(s) outweigh the plaintiff’s defamatory imputations”: Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Kermode [2011] NSWCA 174; (2011) 81 NSWLR 157 (at 179 [85] per McColl JA, with whom Beazley and Giles JA agreed).

34 The imputations conveyed by the Article were that:

Imputation 1: Mr Greiss engaged in the vile act of staring down and spitting towards Mr Hayne’s rape victim;

Imputation 2: Mr Greiss stared down and spat in the direction of Mr Hayne’s rape victim;

Imputation 3: Mr Greiss is despicable, in that he stared down and spat in the direction of Mr Hayne’s rape victim; and

Imputation 4: Mr Greiss sought to harass and intimidate Mr Hayne’s rape victim by staring her down and spitting at her.

35 The Tweet conveyed Imputations 2, 3 and 4.

36 The contextual imputation pleaded to the Article and the Tweet was that:

[Mr Greiss] behaved disgracefully outside of Court to the woman Jarryd Hayne had been sentenced for raping.

37 By the conclusion of the amendment application, the particulars provided were (at PJ [317]):

1. In March 2021, Mr Jarryd Hayne was found guilty of two charges of sexual assault without consent (Hayne Proceedings). Mr Hayne was to be sentenced on 6 May 2021.

2. On 6 May 2021, [Mr Greiss] attended Newcastle Court House to support Mr Hayne and his family at the sentencing hearing.

3. At the sentencing hearing, Mr Hayne was sentenced to 5 years and nine months in gaol.

4. [Mr Greiss] did not consider the sentence to be justified, for reasons including that he alleged the Victim was an escort.

5. After the sentencing hearing occurred, [Mr Greiss] stood with other supporters of Mr Hayne outside of the court building in an area next to a walkway, which walkway hugged the court building (Walkway).

6. When the victim in the Hayne Proceedings (Victim) left the court building, she left via the Walkway.

7. [Mr Greiss] faced the Walkway and stared at the Victim and spat in her direction as she passed by him to exit the court precinct.

8. After the Victim had left the Court precinct [Mr Greiss] described her as an “escort” to a member of the media.

9. The imputations pleaded in paragraphs 5(a)-(d), 8(a)-(b) and 11(a)-(c) of the ASOC are substantially true by reason of the facts, matters and circumstances set out in particulars 1 to 8 above.

38 In upholding the defence, the primary judge identified the issues arising (at PJ [316]) and then found: (1) the Article and the Tweet carried the alleged contextual imputation; (2) the contextual imputation “differs in substance” from the imputations pleaded by Mr Greiss (pleaded imputations); (3) it is substantially true; and (4) having regard to the contextual imputation, the publication of the pleaded imputations caused no further harm to Mr Greiss’s reputation (see PJ [317]–[328]).

39 Mr Greiss submits that her Honour erred in three respects.

40 First, the primary judge misdirected herself as to the correct version of s 26 of the Defamation Act and did not consider properly whether the contextual imputation arose “in addition to” the pleaded imputations as required by s 26(a) of the Defamation Act.

41 Secondly, the primary judge erred in failing to compare the reputational damage caused by the truth of the contextual imputation, according to the terms of the contextual imputation, against the reputational damage caused by pleaded imputations and, because the contextual imputation was pitched at a high level of abstraction, the only proper conclusion to the required analysis was that Mr Greiss’s reputation was “further harmed” by the more specific pleaded imputations.

42 Thirdly, the contextual imputation was not substantially true, and the primary judge’s reasoning miscarried because of the errors in her fact-finding discussed above.

43 I have already explained why there is no merit in the challenge to the primary judge’s central findings and so it is appropriate to turn to the other arguments of Mr Greiss.

E.2 “In addition to” Requirement

44 Notwithstanding an error in the reproduction of the current version of s 26, it is evident the primary judge rejected a submission that the contextual imputation did not arise “in addition to” the pleaded imputations because it “differed in substance”. This conclusion was reached because her Honour found the contextual imputation “captures a broader range of conduct than does the pleaded imputation” (at PJ [319]–[326]).

45 Mr Greiss submits that the application of a “differ in substance” test involves a gloss on the statutory text, albeit one that he accepts has received the imprimatur of the Court of Appeal of New South Wales in Abou-Lokmeh v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd [2016] NSWCA 228 (at [32]–[35] per McColl JA, with whom Gleeson and Payne JJA agreed) and Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Zeccola [2015] NSWCA 329; (2015) 91 NSWLR 341 (at 351–354 [42]–[54], 358–359 [70]–[73] per McColl JA, with whom Macfarlan JA and Sackville AJA agreed).

46 Mr Greiss accepted the “differ in substance” test would not pose difficulty to the extent that it is deployed simply as an aid for determining whether a contextual imputation is “in addition to” an applicant’s pleaded imputations, but it is said to divert attention from the statutory text, namely whether the contextual imputation is an “other” imputation carried “in addition to” those pleaded by the applicant.

47 This argument was developed by contending the present contextual imputation merely rearticulated “the sting of the matters at a higher level of abstraction”. This is because the only sense in which Mr Greiss was alleged in the two matters to have behaved disgracefully towards the victim was by staring her down and spitting at her, which was the conduct the subject of his pleaded imputations.

48 It was further said the contextual imputation was the “pretext” for introducing evidence of a specific incident – Mr Greiss describing the victim as an “escort” to a member of the media – which was not mentioned anywhere in the Article or the Tweet and which was distinct from the conduct, which was mentioned, in that it was not directed at the victim and occurred after the victim had left the area. Put another way, the breadth of the contextual imputation permitted the appellants to rely on particulars of truth which had nothing to do with the Article and the Tweet.

49 Mr Greiss correctly emphasises the need to pay close attention to the statutory words, but fairly read, the primary judge only employed reference to whether the contextual imputation differed in substance as a means of evaluating whether it was “in addition to” the pleaded imputations. This approach was consistent with longstanding authority and there is no reason to conclude the primary judge was distracted from the task required by the statute when her Honour was faced with a contextual imputation which was pleaded in a general or abstract form.

50 The applicable principles were explained (albeit in the context of a capacity dispute) by McColl JA in Abou-Lokmeh v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd (at [30]–[40]). By reference to that case, and the others to which McColl JA referred, those principles can be distilled into the following presently relevant propositions:

(1) in order to be carried “in addition to” the applicant’s defamatory imputations, the contextual imputation must differ in substance from the applicant’s imputations;

(2) the test is straightforward and should involve a process of impression gained from considering the defamatory quality of each party’s imputations having regard to the contents of the publication;

(3) in order to consider whether the contextual imputation is capable of being conveyed in addition to the applicant’s imputations, it is necessary to consider the act or condition attributed to the applicant by both parties’ imputations;

(4) where the applicant pleads several imputations, it will be necessary to consider all of them, separately and in combination, to determine whether a contextual imputation is carried in addition to them;

(5) the requirement that the contextual imputation be conveyed at the same time as the applicant’s imputations enables the tribunal to weigh or measure the relative worth or value of the imputation or imputations for which each party contends;

(6) the question of whether a contextual imputation differs in substance can, in appropriate cases, be determined by identifying what the respondent must or may prove to justify the contextual imputation; and

(7) the question of whether a particular charge of wrongdoing carries a general imputation may depend on the context in which the words are used and the gravity of the misconduct imputed in the more specific imputations – hence the mere fact that a contextual imputation may be “implicit” does not answer the question of whether the general imputation is “in addition to” the specific imputations.

51 There can be no doubt on the state of the authorities that if the publication conveys two imputations (one of a general nature and another of a specific nature which, although related to the same subject matter of the general imputation, differs in substance), the respondent is permitted to rely upon the general imputation.

52 The argument on appeal is more refined. A component of it is that the contextual imputation was not carried in addition to the pleaded imputations because there is nothing in the article to provide the basis for any imputation that Mr Greiss behaved disgracefully towards the victim, other than by staring her down and spitting towards her, and that the evidence must comprise matters that were communicated to the reader. This is a reprise of an argument made at trial (at PJ [324]).

53 Her Honour did not err in rejecting this submission. The primary judge correctly noted that although an imputation must usually be justified by reference to the facts in existence at the time of publication, the general rule may be departed from in circumstances where an imputation amounts to a general charge against the character of the applicant: see P Milmo and W V H Rogers, Gatley on Libel and Slander (Sweet & Maxwell, 11th ed, 2008) (at [11.8]). Here of course, as her Honour noted, the additional matters relied upon (as is evident from the particulars reproduced above (at [37])) include conduct which occurred both at the time, and within minutes of, the matters reported in the Article and the Tweet.

54 Following a commonsense process of evaluation, the primary judge found the generally pitched contextual imputation was carried in addition to the pleaded imputations. There was no error in her Honour’s approach and the impression or evaluative conclusion reached was open to her.

E.3 “Further Harm” Requirement

55 As noted above, at the relevant time, s 26(b) of the Defamation Act required that “the defamatory imputations do not further harm the reputation of the plaintiff because of the substantial truth of the contextual imputations”.

56 The issue posed by this ground of cross-appeal goes to how the Court is to assess the question of “further harm”. More particularly, Mr Greiss complains the primary judge held that the Court’s focus in determining the issue posed by s 26(b) must be on the facts, matters and circumstances establishing the substantial truth of the contextual imputation, rather than the terms of the contextual imputation (at PJ [314]). The kernel of Mr Greiss’s contention is that in adopting such an approach, the primary judge erred in relying upon decisions concerning the Defamation Act 1974 (NSW) (1974 Act) and applying them to the construction of s 26 of the Defamation Act.

57 This argument relied upon a textual difference between the contextual imputation provisions. Section 26(b) focuses on the harm to the applicant’s reputation caused by the “substantial truth of the contextual imputations”, whereas s 16(2)(c) of the 1974 Act focussed upon the fact that the contextual imputations are “matters of substantial truth”. It was this different language, Mr Greiss suggests, that apparently led Spigelman CJ (with whom Rolfe AJA agreed) in John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Blake [2001] NSWCA 434; (2001) 53 NSWLR 541 (at 543 [5]) to observe that the Court must focus on the facts, matters and circumstances said to establish the truth of the contextual imputation, rather than on the terms of the contextual imputation itself (although this explanation may be doubted given Hodgson JA took the contrary view to the majority (at 556–557 [61]) observing that given the reputation of the applicant is not in fact injured at all by the facts, matters and circumstances in question, but only by the publication carrying the contextual imputation; the proper approach is to weigh imputation against imputation).

58 Mr Greiss then provided a detailed history of how Blake has been applied (referring to the details of many cases, including McMahon v John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] NSWSC 196 (at [19]–[24] per McCallum J) (a strike out); Trad v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] NSWCA 477 (at [30]–[33] per Basten JA, with whom McColl JA and Tobias AJA agreed) (a pleading point); and Abou-Lokmeh v Harbour Radio Pty Ltd (at [29]) (a strike out), where McColl JA approved McCallum J’s reasoning in McMahon (at [19]).

59 This was all very interesting but does not reveal error below. The primary judge was well aware of the state of the authorities, including cases in this Court which were consistent with the course adopted by her Honour: see Nassif v Seven Network (Operations) Ltd [2021] FCA 1286 (at [125] per Abraham J) and Palmer v McGowan (No 5) [2022] FCA 893 (at [321] per Lee J).

60 Importantly, her Honour also specifically referred to Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Weatherup [2017] QCA 70; [2018] 1 Qd R 19, where Applegarth J (at 37 [46], Fraser JA and Douglas J agreeing) noted:

The requirement to prove no further harm to the plaintiff’s reputation focuses on the facts, matters and circumstances which establish the substantial truth of the contextual imputations. This reflects the language of the section. The alternative approach of weighing the imputations about which the plaintiff complains, and the contextual imputations which are proven to be substantially true, may be a convenient shorthand or lead to no different outcome in practice.

(Emphasis added, citations omitted)

61 The point made by Mr Greiss is that in many cases, but not all, there will be no difference between the two approaches discussed in the authorities as to the weighing exercise called for by s 26 of the Defamation Act. But the present case is one in which the distinction between the two approaches is said to be decisive because the contextual imputation was pitched at a high level of abstraction.

62 Unlike the more specifically worded pleaded imputations, the terms of the contextual imputation do not disclose any detail as to what he is alleged to have done to the complainant which was “disgraceful”. Readers of the Article and Tweet were not told anything about Mr Greiss calling the victim an “escort” or “prostitute”. It follows, it is submitted, that the fact that he engaged in this unworthy conduct could not have made any impression on the ordinary reasonable person’s assessment of the worth of his reputation, to weigh against the effect caused by what was specifically conveyed, namely that he had stared down and spat at the complainant. Mr Greiss contends that the primary judge’s reliance on this evidence “illustrates the unreality of the Blake approach”.

63 The notion that what should be done is to compare the reputational damage caused by the truth of the contextual imputation, according to the terms of the contextual imputation, against the reputational damage caused by the pleaded imputations, is not one without merit. It commended itself, after all, to no less a judge as Hodgson JA. But, as Applegarth J noted, the Blake approach is also consistent with a textual analysis and has become well established. The fact that the statements explaining the operation of the defence have occurred other than on appeals from trials is not to the point. The primary judge was correct to reason as her Honour did, and bound, as she was, by intermediate court of appeal authority.

64 Adopting the formulation I used as part of the Full Court in Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 122; (2020) 279 FCR 631 (at 668 [126], Allsop CJ and Jagot J agreeing) and by Leeming JA in Pallas v Lendlease Corporation Ltd [2024] NSWCA 83; (2024) 114 NSWLR 81 (at 116 [140]), there is no demonstrated “compelling reason” for this intermediate appellate court to depart from the decisions of other intermediate appellate courts on the operation of this statutory defence contained in uniform legislation.

65 The several attacks on the primary judge’s acceptance of the contextual truth defence in relation to the Article and Tweet fail.

F HONEST OPINION (CA 6) & OTHER MATTERS (APPEAL 1(E)–(I) AND 2; NOC 4 AND 5)

66 As I tried to stress at a case management hearing held in relation to this appeal, significant issues of proportionality arise in relation to a case where, upon success, Mr Greiss was adjudged to be entitled to such a modest amount.

67 Given that the appellants have established a defence in relation to all three publications, there is no utility in reaching a conclusion in relation to the miscellany of other matters advanced by the parties including:

(1) the defence of honest opinion upheld in relation to the Tweet only (although it is not immediately obvious how the Tweet would be understood by the ordinary reasonable person as an expression of opinion when the Facebook post – which also labelled Mr Greiss a “grub” and also was a report of things which took place outside the courthouse – was not regarded as an expression of opinion);

(2) Grounds 1(e)–(f) of the appeal, being an issue going only to damages and by which it is contended the primary judge erred in finding Mr Greiss did not “stare down” the complainant;

(3) Grounds 1(g)–(i) of the appeal, by which it was asserted the trial judge’s award to Mr Greiss of $35,000 plus interest for hurt to feelings was manifestly excessive;

(4) Grounds 2(a)–(e) of the appeal, which went to a contention that the primary judge erred in proceeding on the basis that the costs order below did not allow a recovery equal to that recoverable in a superior court when the primary judge evidently wished to achieve a reduction in the quantum of an adverse costs order (being a matter now rendered irrelevant because the costs order was premised on the partial success of Mr Greiss below); and

(5) contentions relating to aggravated damages.

G COSTS AND ORDERS

68 The appeal must be allowed and the orders entering judgment in favour of Mr Greiss set aside. The proceeding should be dismissed. In the circumstances, the appropriate order is for costs to follow the event of the appeal and further order that Mr Greiss pay the appellants’ costs below.

I certify that the preceding sixty-eight (68) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

Dated: 11 December 2024

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

CHEESEMAN J:

69 I have had the considerable advantage of reading, in draft, the reasons of Lee J. For the reasons given by his Honour, I agree with the orders outlined by Lee J.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Cheeseman. |

Associate:

Dated: 11 December 2024

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKMAN J:

70 I agree with Lee J.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Jackman. |

Associate:

ANNEXURE A (FIRST MATTER)

ANNEXURE B (SECOND MATTER)

ANNEXURE C (THIRD MATTER)