Federal Court of Australia

Zoetis Services LLC v Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc [2024] FCAFC 145

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM ANIMAL HEALTH USA INC Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed with costs.

2. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), access to and disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the unredacted text of the reasons for judgment delivered today be restricted to the external legal representatives of the parties for a period of three days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 On 3 April 2013 the Appellant (‘Zoetis’) applied to the Commissioner of Patents (‘the Commissioner’) for the registration of three Australian standard patents. The first was entitled ‘Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine’ and was numbered 2013243535 (‘the 535 Application’). The second was entitled ‘PCV/Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae combination vaccine’ and was numbered 2013243537 (‘the 537 Application’). The third was entitled ‘PCV/Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae/PRRS combination vaccine’ and was numbered 2013243540 (‘the 540 Application’).

2 Following the examination of the applications by a delegate of the Commissioner and thereafter their advertisement, the Respondent (‘Boehringer’) filed opposition proceedings before the Commissioner opposing their grant. On 28 August 2020, a delegate of the Commissioner found that several of the claims in the 535 Application lacked an inventive step but granted the 537 and 540 Applications in full: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Heath USA Inc v Zoetis Services LLC [2020] APO 40. Boehringer then filed an appeal in this Court in relation to all three applications and Zoetis cross-appealed in relation to the 535 Application. Notices of contention were also filed.

3 Following a trial, the primary judge delivered two sets of reasons. In the first set of reasons, her Honour found that the claims of all three applications were invalid on various grounds with the exception of claim 2 of the 535 Application which her Honour concluded was valid: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Heath USA Inc v Zoetis Services LLC [2023] FCA 1119 (‘J’). In the second set of reasons, the primary judge concluded that certain combination claims which had not been dealt with in the first set of reasons were invalid: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc v Zoetis Services LLC (No 2) [2024] FCA 291 (‘J2’). Her Honour also now held that claim 2 of the 535 Application was invalid: J2 [140]. On 26 March 2024, her Honour made orders disposing of the proceeding. Boehringer’s appeal from the delegate was allowed, Zoetis’s cross-appeal dismissed and the delegate’s decision set aside. In place of that decision the primary judge upheld Boehringer’s opposition to the three applications in full and ordered that each application be refused. Her Honour ordered Zoetis to pay Boehringer’s costs both at trial and before the Commissioner.

4 There are two issues in the appeal: (a) whether the specifications to the three applications disclose the best method known to Zoetis of performing the inventions (this issue being the subject of Grounds 1–8 of Zoetis’s Notice of Appeal); and (b) whether certain claims in the applications which relate to single dose vaccines involve an inventive step (Grounds 9–13).

Background to the three applications

5 The three specifications relate to pig vaccines. At the risk of some over-simplification, the 535 Application involves a composition which provides immunity to a common disease in pigs known as mycoplasmal pneumonia. This disease is caused by a bacterium known as Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (‘M. hyo’). It can affect pigs in particular locations and/or at particular times and so is also known as an ‘enzootic’ pneumonia. Apart from the discomfort of pigs, the problem with M. hyo is that it also hampers growth and hence interferes with the industrial efficiency of growing pigs for slaughter. Vaccines have long been available which provide immunity to M. hyo but, at least at the time that the 535 Application was filed, these vaccines were of a class known as bacterins. A bacterin is a vaccine made from killed whole cell preparations; in this case, killed whole cell M. hyo preparations.

6 M. hyo lacks a cell wall and was described in the expert evidence as a ‘fussy’ microbe. Consequently, it must generally be grown in a serum-containing medium, serum being the fluid or solvent component of blood from which cells and clotting factors have been removed.

7 The composition in the 535 Application is made by growing M. hyo in porcine serum. The resulting culture is then separated into soluble and insoluble parts by processes such as centrifugation, filtration or precipitation. However, porcine serum comes from pigs who will most likely have been exposed to disease. Consequently, it is likely to contain an antibody known as Immunoglobulin G (‘IgG’) and other immune complexes. IgG and other immune complexes remain in the soluble portion of the M. hyo culture after the separation process. It is the soluble portion which has immunogenic qualities (i.e., it can provide some protection against M. hyo), but the presence of the IgG and other immune complexes reduces its efficacy due to a phenomenon known as interference. In simple terms, the presence of antibodies in the composition degrades its effectiveness as a vaccine. The soluble portion is known in the art as a supernatant.

8 Claim 2 of the 535 Application discloses a method of removing the IgG and other immune complexes which the primary judge found was inventive. The method consists of the application of a particular treatment to the serum either before the culturing of the M. hyo (‘upstream’) or after the separation of the soluble portion from the insoluble portion (‘downstream’). The treatment involves column chromatography. The serum (or the soluble portion) is passed through a column containing two proteins known as Protein A and Protein G. The effect of this process is to remove from the serum (or, if downstream, the soluble portion) the IgG and other immune complexes. What results is a composition which can, depending on its precise makeup, provide protection in pigs against M. hyo.

9 Another effect of removing the IgG and immune complexes is to permit other immunogenic substances to be added to it. That is to say, the soluble portion can be used to provide protection not only from M. hyo, but also from other infections to which pigs may be susceptible. Although the 535 Application refers to a number of other such infections, the primary judge concluded (and it is not disputed) that no actual multivalent composition was disclosed by the 535 Application. At various points in these proceedings, the invention in the 535 Application has been described as a platform vaccine. Consistently with that observation, the terms of the 535 Application suggest that the M. hyo supernatant treated by column chromatography with Protein A and Protein G (either upstream or downstream) may be used in this fashion as a platform vaccine when combined with antigens against other porcine viruses (p 8 lines 15–24).

10 Turning then to the 537 and 540 Applications, two other diseases which are very bad for pigs are Post-weaning Multisystemic Wasting Syndrome (‘PMWS’) and Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (‘PRRS’). PMWS is caused by a virus known as the porcine circovirus type 2 (‘PCV-2’). PRRS is caused by a virus known as porcine reproductive and respiratory virus (‘PRRSV’). The 537 Application discloses a bivalent composition made from the supernatant the subject of the 535 Application (namely, the M. hyo supernatant treated with Protein A and Protein G) to which an antigen of PCV-2 has been added. The 540 Application discloses a trivalent composition made from the 535 Application supernatant to which antigens of both PCV-2 and PRRSV have been added.

BEST METHOD

11 Boehringer’s best method challenge before the Commissioner applied to each of the three patent applications in the same way and the vice in each was the same. In its written and oral submissions in this Court, Zoetis did not submit that the outcome of the appeal on best method varied between the 535, 537 and 540 Applications. Attention can therefore be confined to the 535 Application.

The 535 Application

12 The 535 Application concerns an immunogenic composition conferring immunity from M. hyo made by a particular method. It includes claims to a composition, a method for making the composition and various ways of administering the composition to a pig. The primary judge concluded that claims 2, 3, 7, 8 and 11 were invalid because they did not disclose the best method known to Zoetis of performing the invention: J [744]; J2 [140]. For the purposes of this appeal, however, the position of claims 3 and 8 may be put to one side since the primary judge concluded that these two claims were also invalid for a want of sufficiency and Zoetis does not seek to disturb that conclusion on appeal. It follows that the only claims where the best method issue actually arises are claims 2, 7 and 11. Claims 7 and 11 were also found to be invalid by the primary judge for want of an inventive step but that conclusion is challenged in this appeal. Claims 7 and 11 are dependent claims and do not make sense without the other claims. Claims 1 to 11 are as follows:

1. An immunogenic composition comprising the supernatant of a Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M.hyo) culture, wherein the supernatant of the M.hyo culture has been separated from insoluble cellular material by centrifugation, filtration, or precipitation and is substantially free of both (i) IgG and (ii) immunocomplexes comprised of antigen bound to immunoglobulin.

2. The composition of claim 1, wherein the soluble portion has been treated with protein-A or protein-G prior to being added to the immunogenic composition.

3. The composition of claim 1 or claim 2, wherein the composition further comprises at least one additional antigen which is protective against a microorganism selected from the group consisting of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), porcine parvovirus (PPV), Haemophilus parauis, Pasteurella multocida, Streptococcum suis, Staphylococcus hyicus, Actinobacillius pleuropneumoniae, Bordetella bronchiseptica, Salmonella choleraesuis, Salmonella enteritidis, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Mycoplama hyorhinis, Mycoplasma hyosynoviae, leptospira bacteria, Lawsonia intracellularis, swine influenza virus (SIV), Escherichia coli antigen, Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, porcine respiratory coronavirus, Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea (PED) virus, rotavirus, Torque teno virus (TTV), Porcine Cytomegalovirus, Porcine enteroviruses, Encephalomyocarditis virus, a pathogen causative of Aujesky's Disease, Classical Swine fever (CSF) and a pathogen causative of Swine Transmissable Gastroenteritis, or combinations thereof.

4. The composition of any one of claims 1 to 3, wherein the composition further comprises an adjuvant.

5. The composition of claim 4, wherein the adjuvant is selected from the group consisting of an oil-in-water adjuvant, a polymer and water adjuvant, a water-in-oil adjuvant, an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant, a vitamin E adjuvant and combinations thereof.

6. The composition of any one of claims 1 to 5, wherein the composition further comprises a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

7. The composition of any one of claims 1 to 6, wherein the composition elicits a protective immune response against M.hyo when administered as a single dose administration.

8. The composition of claim 3, wherein the composition elicits a protective immune response against M.hyo and at least one additional microorganism that can cause disease in pigs when administered as a single dose administration.

9. A method of immunizing a pig against Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M.hyo) which comprises administering to the pig the composition of claim 1.

10. The method of claim 9, wherein the composition is administered intramuscularly, intradermally, transdermally, or subcutaneously.

11. The method of claim 9 or claim 10, wherein the composition is administered in a single dose.

13 Section 40(2)(aa) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (‘the Act’) provides:

A complete specification must:

…

(aa) disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; …

14 Whilst the word ‘invention’ may bear various meanings in the Act, it is clear that in s 40(2)(aa) it refers to the embodiment which is described and around which the claims are drawn. For the purposes of determining whether the best method of performing the invention has been disclosed, it is necessary to consider both the description of the invention and the claims.

15 Section 40(2)(aa) requires disclosure of the best method known to the patentee of performing the invention. The nature and extent of the disclosure required depends on the nature of the invention itself: Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 138; 126 IPR 427 (‘Sandvik’) at 461 [115(c)] per Greenwood, Rares and Moshinsky JJ; Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 27; 247 FCR 61 (‘Servier’) at 88 [108] per Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ. The nature of the invention is to be discerned from the invention as described in the whole of the specification: Sandvik at 461 [115(d)]; Servier at 91 [124]. The effect of s 40(2)(aa) is that where a patent applicant knows of a method which permits the invention to be more satisfactorily performed, the patent applicant must disclose that method in the specification: Servier at 78 [64]. There is a controversy in the authorities as to whether the relevant date at which this question is to be posed is the date of the filing of the application or the date of the grant: see Servier at 121–122 [259]–[262]. That controversy has no relevance to this appeal since Boehringer’s best method case before the primary judge was based on what was contained in the specification filed with the application and thus satisfies both approaches.

16 Whilst the principles concerning the best method requirement are largely uncontroversial, what is material for the present appeal is the Full Court’s observation in Servier that the patentee ‘has an obligation to include aspects of the method of manufacture that are material to the advantages it is claimed the invention brings’: 94 [135]. Thus, if the impugned method is not material to the advantages it is claimed the invention brings then the disclosure obligation in s 40(2)(aa) is not enlivened. In both Servier and Sandvik the Court was satisfied that the non-disclosed method was material to the advantages it was claimed the inventions brought.

17 In Servier, the invention claimed was an arginine salt of perindopril (a blood pressure drug) to be used as a pharmaceutical composition. The specification disclosed that the salt could be prepared using ‘a classical method of salification’. Whilst the expert evidence showed that this was sufficient to enable the person skilled in the art to make the salt, there were in fact several such methods which resulted in different forms of the salt. Some of these forms were more advantageous as pharmaceutical compositions than others. Prior to the filing of the application, the patentee had used two particular classical methods of salification to produce the arginine salt of perindopril which had resulted in a composition which was suitable for pharmaceutical use. These two methods were not disclosed in the specification. The trial judge concluded that the best method of performing the invention had not been disclosed: Apotex Pty Ltd v Les Laboratoires Servier [2013] FCA 1426 at [179], [187] per Rares J. This conclusion was affirmed by the Full Court. Adopting a phrase deployed by the trial judge, the Full Court emphasised that disclosure of a particular classical method of salification which Servier knew to provide the stated advantages of the invention would have relieved the skilled addressee from ‘confronting blind alleys and pitfalls’ in formulating the composition: Servier at 93 [134].

18 In Sandvik the invention was an extension drilling system for use on a semi-automatic drilling rig that was used to drill holes during subterranean mining operations. In implementing the invention, an important issue which needed to be overcome was the design of an effective water sealing mechanism. The invention assumed that a water sealing mechanism would be provided although no claim was made for any particular water sealing mechanism. Sandvik knew of a particular water sealing mechanism which was effective but did not disclose this in the specification. The Court concluded that Sandvik had not disclosed the best method known to it of performing the invention: Sandvik at 463 [124].

19 At this point, mention should be made of the Full Court’s decision in Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd [2000] FCA 1689; 51 IPR 531 (‘Firebelt’), a decision of a Full Court comprising Spender, Drummond and Mansfield JJ. An appeal to the High Court on an unrelated ground was dismissed: Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd [2002] HCA 21; 76 ALJR 816. The patent was for an automated side loading refuse vehicle. The trial judge attached both the claims and a breakdown of their integers as Annexures 1 and 2 to his Honour’s reasons (Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (1998) 43 IPR 83) as follows:

ANNEXURE 1

1. In a side loading refuse vehicle having a cab, the combination of an elongate refuse storage tank divided into longitudinally extending tank sections, a loading mechanism adjacent a side of the refuse vehicle and a refuse transfer mechanism for delivering refuse or other material emptied into the vehicle by the loading mechanism to the respective tank sections, the loading mechanism having a lid opening device and the loading mechanism being adapted to engage a bin of the type having a pivoting lid by remote control from the cab, raise the lid and empty the bin into the vehicle, the bin holding recyclable waste separately from other waste in the bin and upon being emptied into the vehicle, the recyclable waste and the other waste are separately delivered by the transfer mechanism to respective ones of the said tank sections.

2. The combination of claim 1 wherein the tank sections are located one above the other.

3. The combination of claim 1 or claim 2 wherein the transfer mechanism is an active transfer mechanism.

ANNEXURE 2

(a) In a side loading refuse vehicle

(b) having a cab

(c) the combination of an elongate refuse storage tank divided into longitudinally extending tank sections

(d) a loading mechanism adjacent to the side of the refuse vehicle and

(e) a refuse transfer mechanism for delivering refuse or other material emptied into the vehicle by the loading mechanism to the respective tanks

(f) the loading mechanism having a lid opening device and

(g) the loading mechanism being adapted to engage a bin of the type having a pivoting lid by remote control from the cab

(h) raise the lid and

(i) empty the bin into the vehicle

(j) the bin holding recyclable waste separately from other waste in the bin, and

(k) upon being emptied into the vehicle, the recyclable waste and other waste are separately delivered by the transfer mechanism to the respective ones of the tank sections.

(l) the combination in claim 1 wherein the tank sections are located one above the other.

(m) The combination of claim 1 or claim 2 wherein the transfer mechanism is an active transfer mechanism.

20 It will be seen from (f) of Annexure 2 that claim 1 included a claim to a lid opening device. As with the method of classical salification in Servier and the water sealing mechanism in Sandvik, the specification did not disclose any particular lid opening device and left it to the addressee to provide one. There was evidence before the trial judge from the inventor that ‘the system would not work at all without the lid opening device as specified’ which the trial judge accepted: Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (1998) 43 IPR 83 at 87 per Dowsett J. The Full Court concluded at 544 [52] that the disclosure obligation was not enlivened:

The invention claimed is not of a particular type of lid opening device operating at any particular time. There is therefore no statutory obligation to describe which of the contemplated lid opening devices was considered to be the best, nor the preferred timing, contrary to his Honour’s understanding of the section.

21 This conclusion is difficult to reconcile with the outcomes in Servier and Sandvik. The advantage claimed for the invention would not obtain without the lid opening device and the person skilled in the art would need to spend time developing a lid opening mechanism to achieve the promise of the invention (since the system would not work without it). In that sense, the non-disclosed method was material to the advantages it was claimed the invention conferred. It was not submitted in Servier that this aspect of Firebelt was incorrectly decided and, indeed, the Full Court cited other parts of Firebelt with approval. In Sandvik the patentee relied on Firebelt to submit that since the water sealing mechanism was not part of the invention claimed it was not subject to an obligation to disclose the best water sealing mechanism known to it. At 463–464 [126] the Full Court in Sandvik said this:

In Firebelt, the Full Court held that the specification did not need to describe the best lid opening mechanism known to the inventors because the invention was “not of a particular type of lid opening device operating at any particular time” (at [52]). Sandvik submits that, by parity of reasoning, it was unnecessary for it to describe the best form of sealing member known to it. However, in determining whether the requirement to describe the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention has been satisfied, it is necessary to examine carefully the facts and circumstances of the particular case. In the present case, the invention as described in the specification is an extension drilling system as set out in [117] above. The use of an effective sealing member was necessary and important to carry that invention into effect. The same may not have been true of the lid opening mechanism in Firebelt in light of the way in which the invention was identified by the Full Court.

22 However, it is clear from the reasons of the trial judge in Firebelt that the lid opening mechanism was essential for carrying the invention into effect. Boehringer does not invite this Court to depart from Firebelt but instead seeks to distinguish it on the basis that the evidence in Firebelt showed that various forms of lid opening device had been disclosed in the specification (whereas in this case precise antigen concentrations had not). So much does appear from 545 [54] of the Full Court’s reasoning in Firebelt:

The text of the complete specification of the petty patent leaves no doubt that the figures 4, 5 and 8 referred to in that specification depict an embodiment of the lid opening device, and the description of figures 4 and 5 includes:

. . . a jet of water shown at 30 fired from nozzle 31 on the loading mechanism 19 opens the lid 32 of the bin 20 prior to the contents of the bin 20 being discharged. This will be slightly delayed due to the inertia of the bin being raised through its arc of movement to the final stop position illustrated in figure 5. In other words, the combined effect of the movement of the bin through its arc followed by the jet of water discharged from nozzle 31 followed by raising of the ramp into the aligned position illustrated in figure 5 will ensure that minimum recyclables from compartment 27 end up in the wrong tank section. As an alternative to the jet of water, other mechanically equivalent contrivances can be employed including air jets or directly acting mechanical lid openers.

23 The Full Court’s actual conclusion is at 545 [55]:

In our respectful view there has been no failure of the duty to disclose the best method of performing the invention known to the applicant, as required by s 40(2) of the Act.

24 Firebelt has been referred to on a number of occasions by the Full Court without disapproval including most recently in SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (t/as Database Consultants Australia) v Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 6; 176 IPR 391 at 429 [129] per Burley, Jackson and Downes JJ. However, the correctness of the reasoning in Firebelt at [52] does not appear to have been expressly considered, although the case has been distinguished from time to time for reasons that appear to be at odds with that reasoning: see, for example, Sandvik at 463 [124].

25 The Full Court’s reasons at [52] in Firebelt focus on the form of the claims. With respect to their Honours, if they are to be taken as saying that the form of the claims is determinative, we do not agree. The fact that none of the claims in that case was to a lid opening device operating at any particular time could not of itself be an answer to the best method challenge if the timing of such operations was advantageous to the working of the combination or the quality of the outcomes achieved from its use. In deciding whether the best method has been disclosed it is necessary to look at the invention disclosed in the specification as a whole, not merely the claims: Sandvik at 463–464 [125]–[126].

26 Other considerations relevant when determining if there has been non-compliance with s 40(2)(aa) of the Act may include the burden imposed on the skilled addressee by the non-disclosure of the relevant information and the burden imposed on the patent applicant by requiring its disclosure. As the authorities make clear, the question to be decided very much depends on the facts and circumstances of the particular case.

27 The issue of best method was considered in GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 71; 264 FCR 474 (‘GlaxoSmithKline’) in the context of a claim to a pharmaceutical composition in circumstances where the patent did not disclose the particular grade or viscosity of an excipient (HMPC) or the granulation endpoints used to make preferred embodiments described in the body of the specification.

28 As the Full Court (Middleton, Nicholas and Burley JJ) observed in GlaxoSmithKline at 511–512 [187]:

Whether there has been a failure to make the required disclosure is essentially a question of fact. Every case will depend on its own facts including the nature of the invention, and the significance of what is and what is not disclosed. And like many other questions that arise in relation to the interpretation of a patent specification and the scope of its disclosure, the question whether there has been sufficient disclosure of the best method should be addressed in a practical and common sense manner. It is also necessary to have regard to the public policy justification that supports the best method requirement.

29 The Full Court went on to consider whether it was open to a patent applicant to withhold information on the basis that it could be obtained by routine experimentation. We agree with the following observations of the Full Court at 513 [191]–[192]:

We do not think the patent applicant is entitled to withhold information that is necessary to enable the skilled addressee to perform the invention in accordance with the best method merely because the skilled addressee could ascertain such information by routine experiment. There is a great deal of experimentation performed in the field of drug development and formulation which, although routine and not requiring the application of any ingenuity, may be, time consuming and expensive. For the patent applicant to withhold information which it knows is necessary to perform the invention in accordance with the best method merely because the information could be obtained by routine experimentation is in our view inconsistent with what Fletcher Moulton LJ described [in Vidal Dyes Syndicate Ltd v Levinstein Ltd (1912) 24 RPC 295 at 269] as the settled law that required the patentee to give the best information in its power as to how to carry out the invention.

Whether or not it will be open to the patent applicant to not disclose relevant information on the basis that it is available to the skilled addressee by routine experimentation will depend on the importance of the information in question, the practicality of disclosing it, and the extent of the burden imposed on the skilled addressee who is left to rely upon routine experimentation. That question is, as we have already mentioned, to be addressed in a practical and common sense manner.

The nature of the invention

30 For the reasons already given, in discerning the nature of the invention for the purposes of s 40(2)(aa) the inquiry is not into the various inventions disclosed in the individual claims but rather into the invention as claimed in any claim read together with the whole of the specification. The primary judge identified the nature of the invention in the 535 Application in the following terms at J [718]–[719]:

718 The invention in the 535 Application and around which the claims are drawn may be described as an improved immunogenic composition or vaccine to elicit a protective response in pigs against the disease caused by M. hyo, utilising an M. hyo soluble preparation which can also be used as a base or platform for a combination vaccine with at least one additional antigen protective against selected microorganisms (other than PCV-2, as there are no claims to an M. hyo/PCV-2 combination).

719 Whilst claims 1 to 6 are to an immunogenic composition, a close reading of the whole of the specification shows that the invention is concerned with eliciting a protective immune response to protect pigs from disease caused by M. hyo, (ie a vaccine) which is within the specification’s definition of an immunogenic composition. The later claims are to methods of eliciting a protective response, and immunising a pig utilising the immunogenic composition (ie vaccines). The title of the 535 Application is “Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine” and the field of the invention relates to a vaccine. The 535 Application states that what is needed is an improved vaccine, and that it would be highly desirable to provide a ready-to-use, single dose M. hyo/PCV-2 combination vaccine. The prior art discussed in the specification are vaccines.

31 It is not suggested by either party on appeal that this characterisation of the invention was incorrect. The two important elements are, first, the ability to be administered as a single dose and, secondly, the suitability of the M. hyo composition to be used as part of a combination vaccine conferring immunity against both M. hyo and one of a number of other porcine viruses.

The undisclosed method

32 Boehringer’s best method case before the primary judge was set out at §5 of its Second Further Amended Notice of Contention. Without setting it out in full, what Boehringer alleged was that, prior to the filing of the 535 Application, Zoetis had formulated a number of compositions in the form of experimental vaccines each of which was a method of performing the invention in the 535 Application. These experimental vaccines were known as investigational vaccine products or ‘IVPs’.

33 Whilst the specification made extensive reference to the IVPs, it is not in dispute that the specification did not permit the person skilled in the art to make any of them. Boehringer does not seek to identify any particular IVP as the best method known to Zoetis of performing the invention but it does say that, between them, one must be that method. Its principal reason for this contention is that the specification did not disclose how to make any particular form of the vaccine but instead merely disclosed that it could be made with a given range of M. hyo antigens. Zoetis knew how to make several different forms of vaccine falling within that range but the specification did not disclose how to make any of them. To this may be added the observation that the specification also showed that the IVPs varied in their efficacy as vaccines. This the primary judge found at J [731] (‘Various passages in the specifications indicate that some IVPs performed better than others, for example in terms of efficacy’). If some of the IVPs were more efficacious than others then, so the argument runs, one of them must have been the most efficacious. On either of these views, it was necessary for Boehringer to identify which of the IVPs was the best method known to Zoetis because the logic of the situation necessarily entailed that one of them was.

34 This contention is related to other findings that her Honour also made. The first was that a greater titre of specific protective antigens was likely to lead to a greater duration of immunity. This finding was at J [663] and was based on evidence from Professor McVey in his affidavit that he ‘and other persons involved in swine vaccine development knew at April 2012 that the immune response would be related to the antigen mass titre in the vaccine’.

35 The second was that where bivalent or trivalent vaccines were concerned it was necessary to achieve a balance between the two or more antigens involved. Her Honour made this finding at J [731]–[732]:

731 The Applications either specify the potencies of the IVPs in the examples in relative units, without defining the relevant reference or comparator, or in certain cases, do not describe the preferred compositions at all. The examples describe particular IVPs and evaluate their performance by comparing them against each other. Various passages in the specifications indicate that some IVPs performed better than others, for example in terms of efficacy. There are also references to the need to “balance” the antigens, which the experts confirm as being important.

732 The three Applications claim to have developed an immunogenic composition that provides protective efficacy after a single dose. The experts understood single dose efficacy to be an important aspect of the invention. The potency of, and balance between, the antigens in such a composition is critical to its ability to meet that objective. Similarly, it is relevant that the Applications claim to have solved the problem of interference, including not only interference by serum-derived antibodies, but also antigen-antigen interference. Again, the potency of, and balance between, the antigens in such a composition is critical.

36 Her Honour did not explain what was meant by the concept of a balance between the antigens but the evidence before her Honour did and the finding above, whilst brief, is significant. The evidence was as follows.

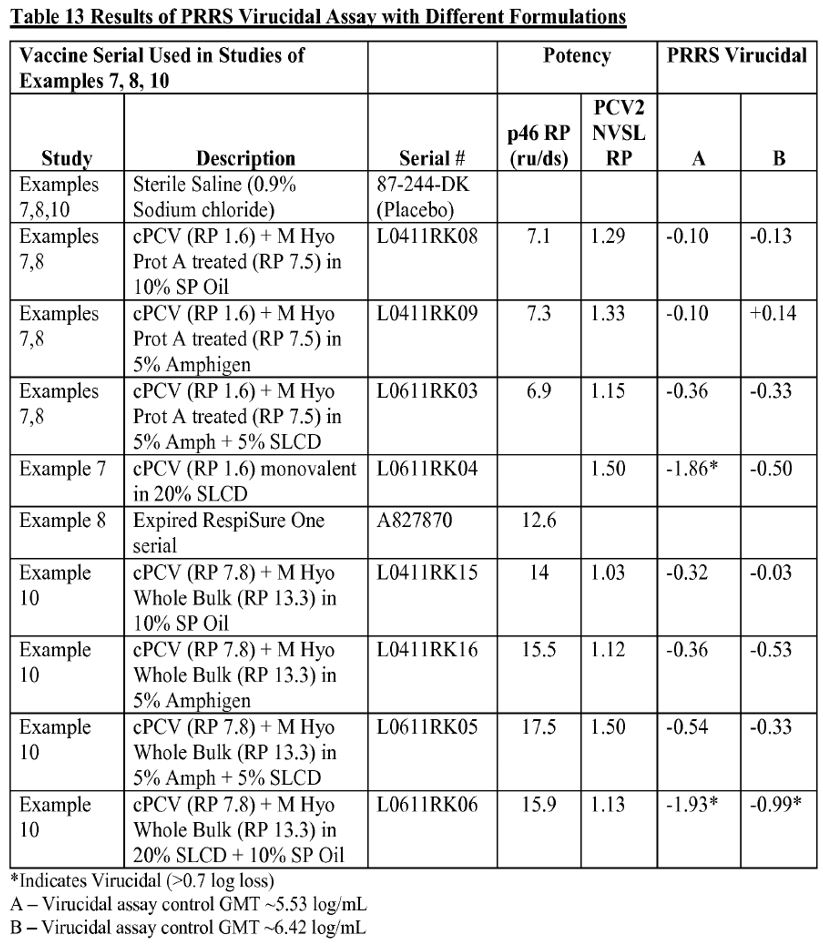

37 Example 12 of the 535 Application was concerned with an evaluation of the virucidal activity against the PRRS virus. In particular, as p 48 line 28 to p 49 line 2 of the 535 Application shows, what was being tested was the effect the various adjuvants had upon virucidal impact. A number of different formulations were tested and it is apparent from Table 13 at p 49 that different antigen strengths for M. hyo and PCV-2 were tested (noting that RP is a reference to the reference product):

38 The specification continued at p 50 lines 2–9:

The results presented in Table 13 above indicate that 10% SP-oil is non-virucidal to PRRS virus.

Further PCV/M.hyo vaccine serials were prepared using 10% SP-oil as the adjuvant (Table 14). The antigenic potency of these vaccine serials was compared to a Reference PCV/M.hyo vaccine serial (L1211RK15) which contained 0.688% of a 20X concentrate of PCV2 antigen (prepared as described in Example 2); and 9.40% of M.hyo antigen prepared as described in Example 11. The results shown in Table 14 below further indicate that 10% SP-oil is non-virucidal to PRRS virus. The test sample values in Table 14 were each higher (+ sign) than the virucidal assay control, which had a geometric mean titer (GMT) of about 5.9±0.5 log/ml.

39 Thus it is clear from the terms of the specification that Zoetis was deploying fluctuating levels of antigen contents. The results in Example 12 were picked up and applied, this time with PRRS in addition, in Example 13 (i.e., a trivalent composition). Since it is the same point, it is not necessary to set it out. Of course, neither Example 12 nor Example 13 used the word balance. That word instead emerged from the examination of the experts at T212.7–36:

MS CUNLIFFE: Okay. Thank you. Am I right in saying too that there is a prospect of interference between antigenic fractions. So for example, the first antigen might overpower the second antigen leading to a poor immune response to the second antigen. That’s a possibility, isn’t it?

PROF McVEY: It is a possibility.

MS CUNLIFFE: Professor Browning.

PROF BROWNING: I think it depends on your definition of antigen because there are – antigen is used to cover a host of different preparations. I think that’s very unlikely if you’re talking about purified proteins. It’s quite a different matter if you’re talking about antigen as a live attenuated vaccine.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you. Dr Nordgren.

DR NORDGREN: ..... think of examples where antigen interference has been an issue with the vaccine formulation that you need to respond with a shift in the antigenic content.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you. And Professor Chase.

PROF CHASE: Yes. I agree with that as well.

MS CUNLIFFE: Sorry. When you say you agree with that, which of the comments do you agree with?

PROF CHASE: Well, I agree with the fact that often times you have to look in the combination in terms of how you might have to change antigenic content to balance things out.

40 It also emerged from the examination at T215.35–216.16:

MS CUNLIFFE: So it would be necessary to do in vivo tests on the combined vaccine to assess immunogenicity and ensure a robust antibody response against each component and a sustained antibody response, wouldn’t it, Professor McVey?

PROF McVEY: That would be desirable. Although sometimes antibody response is – it may not be extremely high. There may be other aspects to the immune response that are important.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you, and can you expand on what those are?

PROF McVEY: Cellular responses or specific interactions of some antibodies with cells.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you.

PROF McVEY: Infector cells.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you. Professor Browning, would you care to comment on that answer?

PROF BROWNING: I agree.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you. Dr Nordgren.

DR NORDGREN: The balance. Yes.

MS CUNLIFFE: Thank you, and Professor Chase.

PROF CHASE: I would agree, too, that the ..... is also important often.

41 There is an agreed transcript correction that the ellipsis in the last line should be the word ‘balance’. Thus the expert evidence showed that balance between the antigens was relevant. This also appeared from Zoetis’s discovered documents. One of these, an email dated 28 January 2013 (known as AT204) contained this passage:

Dan is working on the protocol for the repeat M hyo immuno study (to be run at a CRO) and in light of our One-Bottle discussions around ‘balanced’ dosing between the PCV2 and M hyo components, was looking at alternatives to the vaccines we used in the original study – I’ve attached a couple of excerpts of potencies from the original group of Trivalent PMP studies below to help understand where this is going …

42 A second document, Exhibit A18 (known as AT303), was a confidential study report of Zoetis produced in late 2012. The study canvassed some of the IVPs referred to in Example 14 of the 535 Application. Under the heading ‘Abstract’ on p 2 it said:

Two experimental trivalent PCV1-2/M. Hyopneumoniae/PRRS vaccines at different, but balanced, antigen dose levels and one experimental monovalent M. Hyo.pneumoniae and PRRS lyophilized monovalent (negative control) vaccines were formulated with the highest passage antigen and mixed prior to administration.

43 Whilst the primary judge’s explanation of what balance between the antigens entailed was brief, there can be no doubt that her Honour’s finding at J [731]–[732] was sustained by the evidence which was before her Honour.

44 Thus, her Honour was correct to conclude that the concentration of the antigens and the balance between the antigens was important for the efficacy of the vaccine.

45 Returning to the IVPs, one difference between the various IVPs lies in their respective concentrations of M. hyo antigens. The specification did not identify the antigen concentrations of the IVPs other than by comparison to a reference vaccine but the antigen concentration of the reference vaccine was not disclosed in the specification either. In the specification, the efficacy of the IVPs was also measured against the reference vaccine. From reading the specification, the person skilled in the art could determine that some of the IVPs were more efficacious than others. This problem is exacerbated when the problem of balance between the antigens is introduced into the picture.

46 In order for the person skilled in the art to make one of the more efficacious IVPs it would be necessary for them to know the antigen concentration of that IVP. However, because the specification only stated the antigen concentration of each IVP by reference to the antigen concentration of the reference vaccine and because the antigen concentration of the reference vaccine was not disclosed, it would not be possible for the person skilled in the art to make any of the IVPs.

47 The evidence of Dr Nordgren, who was called by Boehringer, established that a person skilled in the art could make each of the IVPs if told of its antigen concentration. The primary judge also found that the 535 Application disclosed the invention in a manner which was clear and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art within the meaning of s 40(2)(a) of the Act (although not in relation to its combination claims which are not presently material): J [609]. Thus, since every vaccine has an antigen concentration, it follows that the 535 Application permitted a person skilled in the art to perform the invention with any desired antigen concentration.

48 There is nothing in Zoetis’s submission that the fact that the person skilled in the art was enabled to make vaccines with any desired antigen concentration had implications for the best method issue. The two grounds are distinct in s 40(2) and are to be kept that way. There is no conceptual difficulty in concluding that an invention is enabled across a range (as here of antigen concentrations) but, at the same time, concluding that the best method of making the composition has not been disclosed. This was the situation in Servier. There the specification enabled the person skilled in the art to make the arginine salt of perindopril using a range, in that case, of classical methods of salification. But the fact that the invention was enabled across that range did not save it from invalidity for failing to disclose the two particular classical methods of salification which it knew resulted in a suitable pharmaceutical composition.

Were the antigen concentrations material to the advantages the invention brings?

49 Zoetis will have been obliged to disclose the antigen concentration of the reference vaccine (as the ‘key to unlocking’ the antigen concentrations of the IVPs: J [744]) if, in terms of Servier, antigen concentration is ‘material to the advantages it is claimed the invention brings’: 94 [135]. This is a question of expert evidence. In Servier the expert evidence was that pitfalls and blind alleys confronted the person skilled in the art in selecting an appropriate method of classical salification to yield an arginine salt of perindopril suitable as a pharmaceutical composition. Servier’s knowledge that two particular methods of classical salification yielded a salt suitable for use as a pharmaceutical composition was knowledge which would have assisted the skilled addressee in avoiding those pitfalls and blind alleys. In Sandvik there was evidence that the water sealing mechanism was essential to the performance of the invention and that Sandvik knew how to make a water sealing mechanism which worked.

50 In this case, the advantages conferred by the invention are the ability to deliver a composition conferring immunity against M. hyo in a single dose and to do so in such a way that the composition can be used as a platform to deliver immunity against other porcine viruses.

51 Having reviewed the evidence, the primary judge concluded that ‘the examples describe particular IVPs and evaluate their performance against each other’: J [732]. Importantly, at the same paragraph her Honour also concluded that ‘various passages in the specifications indicate that some IVPs performed better than others, for example, in terms of efficacy’ (emphasis added).

52 This conclusion was consistent with the expert evidence which had been led. As already noted, Professor McVey was called by Zoetis and gave evidence that the immune response related to the antigen concentration of the specific antigens in the vaccine so that a greater titre of specific protective antigens was likely to lead to a greater duration of immunity, which the primary judge noted at J [663]. The question then becomes whether conferring a greater duration of immunity is one of the advantages that the invention is claimed to bring. The primary judge noted that the experts understood that single dose efficacy was an important part of the invention observing that ‘[t]he potency of, and balance between, the antigens in such a composition is critical to its ability to meet that objective’: J [732]. That finding is not challenged on this appeal.

53 It follows, applying Servier and Sandvik, that it would confer an advantage on the skilled addressee to know what antigen concentration would result in the composition being most effective when administered as a single dose and which balance between the antigens would result in a combination vaccine that could confer immunity against M. hyo and PCV-2.

Ground 2: ranges

54 This brings one to the range identified by Zoetis in the 535 Application, upon which Ground 2 of its Notice of Appeal hinges. The specification suggested that in one of the invention’s embodiments the concentration of the M. hyo protein antigen termed ‘p46’ was set at ‘about 1.5 µg/ml to about 10 µg/ml, preferably at about 2 µg/ml to about 6 µg/ml’. About this range, Zoetis makes two different submissions. First, the disclosure of this range in the specification was the disclosure by it of the best method known to it of performing the invention. On this view, the best method for making the vaccine was to make it with a range of antigens between ‘about 1.5 µg/ml to about 10 µg/ml, preferably at about 2 µg/ml to about 6 µg/ml’. This submission cannot be reconciled with the fact that within that range different IVPs demonstrated fluctuating levels of efficacy. The submission impermissibly elides enablement across that range with equality of efficaciousness across that range.

55 The second submission is that any vaccine made with antigen concentrations within the disclosed range would deliver the promise of the invention (an M. hyo vaccine capable of being administered in a single dose and usable as a combination vaccine). Any such vaccine would therefore be an embodiment of the invention. It follows, on Zoetis’s argument, that by disclosing that the concentration of the p46 antigen was set at ‘about 1.5 µg/ml to about 10 µg/ml, preferably at about 2 µg/ml to about 6 µg/ml’ the specification thereby constituted ‘the disclosure of a range of embodiments’. Zoetis also draws upon the principle that where a specification describes more than one embodiment of an invention, a patent applicant is not obliged to state which embodiment is best: Sandvik at 460 [113]. The application of that principle to the present case means, Zoetis submits, that it was not obliged to say which antigen concentration within that disclosed range was best. This argument is the subject of Ground 2 of the Notice of Appeal.

56 It is not in dispute that a patent applicant’s obligation to disclose the best method of performing the invention known to it is satisfied by disclosing that method in an embodiment in the specification and that, if this is done, there is no need to say that one of the embodiments constitutes the best method. The primary judge referred to this principle at J [622] and it was accepted by the Full Court in Sandvik at 460 [113]. Whilst this is true, however, the patent applicant remains bound to disclose the method fairly. As Nicholls LJ observed in C Van Der Lely NV v Ruston’s Engineering Co Ltd [1993] RPC 45 at 56, the patent applicant ‘is not required to state that it is the best method, so long as he fairly discloses it as a method’. But there must be a real disclosure of the best method which may require the patent applicant to do more than identify a range from within which the best method may be found.

57 Consistently with that observation, Boehringer submits that it is not correct that a general disclosure encompassing all embodiments without disclosing the details of any of them would satisfy the best method requirement. Boehringer’s identification of the nature of disclosure is correct. Zoetis’s submission is that the specification ‘disclose[d] a range of embodiments’ because it disclosed that the invention could be satisfactorily performed over the disclosed range of antigen concentrations. If this is correct, then the specification disclosed a large number of embodiments. The disclosed range at p 15 line 19 of the 535 Application is 1.5 µg/ml to about 10 µg/ml. Making the assumption in Zoetis’s favour that it would not be practical to deal in increments of less than 0.1 µg/ml, this still entails that the specification disclosed 85 embodiments. With such a number of embodiments, a fair disclosure of the best method known to Zoetis of making the vaccine required Zoetis to indicate which was the most efficacious to its knowledge from the trials it had conducted on that issue through the assay of the various IVPs. Thus, Ground 2 should be rejected.

Grounds 1 and 4: did Zoetis know a method of performing the invention which conferred the advantages of the invention?

58 It is clear, in our respectful opinion, that Zoetis knew how to make compositions which conferred the advantages identified at [50] above. Example 9 in the specification (p 43) was headed ‘Evaluation of M. hyo efficacy of a 1 bottle PCV2/M. hyo Combination Vaccine in 10% SP-Oil’. Under this heading the specification said at p 43 lines 20–25:

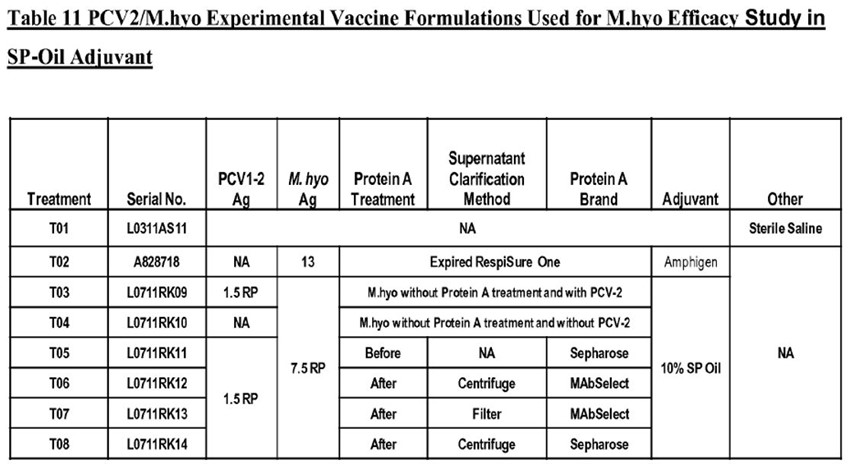

This study is a proof of concept designed to evaluate the M.hyo fraction efficacy of four experimental PCV2/M.hyo vaccines (Serials L071 IRK 11, L071 1RK12, L071 1RK13 and L071 1RK14 in Table 11 below) prepared by different M.hyo manufacturing processes which utilize Protein A for IgG removal compared to control vaccines prepared with the standard M.hyo manufacturing process. Each of these four experimental PCV2/M.hyo vaccines included 10% SP-oil as the adjuvant.

59 There then followed a description of 8 treatments leading to the vaccines known as T01–T08. Although these were detailed, as will be seen, because the absolute concentration of the antigens was not given it was not possible for a person skilled in the art to produce the IVPs which resulted. After the description of the methods there then appeared Table 11 on p 46:

60 The IVPs appear in the second column. The reference to ‘RP’ is a reference to the reference product against which efficacy was measured. The references to PCV1-2 ‘Ag’ and M. hyo ‘Ag’ are references to the antigen content of the IVP as measured against the RP. As the primary judge observed, the antigen content of the RP was not disclosed with the effect that the antigen content of the IVPs was not disclosed either.

61 Following Table 11 there then appeared at lines 5–22 the following:

Pigs at 3 weeks of age were intramuscularly inoculated with a single dose of the different vaccine formulations described in Table 11 above. There were 18 pigs included in each treatment group. Animals were challenged 21 days after vaccination with a virulent M.hyo field isolate. Animals were necropsied 28 days after challenge and the lungs were removed and scored for consolidation consistent with M.hyo infection. Figure 8 (A & B) show the lung lesion scores for the respective treatment groups. Statistical significance was determined by a Mixed Model Analysis of lung scores for each group.

The lung lesion results depicted in Figures 8A and 8B indicate that of all the treatments, only two (T07 and T08) had 100% of pigs in the <5% lung lesion category. It is noted that strong statistical difference were observed in this study.

The results in the present example demonstrate significant M.hyo efficacy in a 1 -bottle PCV2/M.hyo experimental formulation employing the Protein A-treated M.hyo supernatant and utilizing SP-oil as the adjuvant. Additionally, Example 7 above demonstrated PCV2 efficacy in a 1-bottle PCV2/M.hyo formulation employing the Protein A-treated M.hyo supernatant and utilizing SP-oil as the adjuvant. Taken together, both M.hyo and PCV2 efficacy have been demonstrated in the 1 -bottle PCV2/M.hyo combinations employing Protein A-treated M.hyo supernatant.

62 Tables 8A and 8B appeared at the end of the specification. The effect of this is that at least T07 (L0711RK13) and T08 (LK0711RK14) were shown to be significantly effective when administered as a single dose. This demonstrates that Zoetis knew a method of performing the invention which conferred the advantages promised by the invention, viz, efficacy when administered as a single dose and suitability to be used as a platform vaccine in combination with antigens conferring immunity against other porcine viruses. But without knowing what the actual antigen concentration of the IVPs was, the person skilled in the art was left to discover for themselves what the appropriate antigen concentrations were which could deliver the results illustrated in Table 11. It would be necessary for that person to conduct their own work to bring about the result that Zoetis had already accomplished.

63 It was therefore clear that there were methods known to Zoetis of performing the invention which delivered on the advantage it promised to confer; i.e. an M. hyo vaccine with single dose combination efficacy.

64 Zoetis submits that this does not entail that it had failed to disclose the best method known to it of performing the invention. It argues that to establish the case it had pleaded, Boehringer had to demonstrate that one or other of the ten IVPs was, and was known to Zoetis to be, a better method of performing the invention than any IVP with absolute antigen concentrations falling within the disclosed ranges. Boehringer submits that this was not so because the specification did not disclose any method at all since all that was disclosed was a range of antigen concentrations. Since no method was disclosed, the fact that Zoetis knew that the IVPs were of varying efficacy entailed that it knew which of them was most efficacious. It was not necessary therefore for Boehringer to identify which of the IVPs was known to Zoetis to be the best IVP.

65 We accept Boehringer’s submission. It would be possible, as Zoetis submits, for Boehringer to prove that one of the IVPs was the best method known to Zoetis and then to demonstrate that that method had not been disclosed. But what is involved is a factual question: did Zoetis disclose the best method known to it of performing the invention? Whilst that fact could be proved in the manner suggested by Zoetis this is not the only way it could be proved. Forensically, it was equally open to Boehringer to demonstrate that Zoetis knew of a best method which it had not disclosed without identifying that best method. The evidence showed that the IVPs varied in efficacy and the logic of this entailed that one of them was most efficacious (or even that two were equally the most efficacious). In that circumstance, there was no need for Boehringer to identify which of the IVPs was best. Zoetis’s argument to this effect is embodied in Ground 4 which should be rejected.

66 The case, therefore, is indistinguishable from Servier for four reasons. First, in Servier the specification of a classical method of salification was sufficient to allow the person skilled in the art to make the arginine salt of perindopril for use as a pharmaceutical composition. Here the specification is sufficient to allow the person skilled in the art to make a composition suitable for administration in a single dose and as part of a combination vaccine conferring immunity against both M. hyo and PCV-2.

67 Secondly, in Servier different methods of classical salification resulted in different forms of the arginine salt of perindopril which were of varying levels of suitability for use as a pharmaceutical composition. In this case, the person skilled in the art could make the composition with varying antigen concentrations (and different balances between the antigens).

68 Thirdly, in Servier the patentee had utilised two particular classical methods of salification to produce forms of the arginine salt of perindopril which were suitable to be used as a pharmaceutical composition. In this case, Zoetis produced IVPs some of which were more efficacious than others.

69 Fourthly, in Servier the particular classical methods of salification which the patentee had used were not disclosed. In this case, Zoetis did not disclose how to make any of the IVPs because it did not disclose their antigen concentration.

70 There is therefore no relevant difference between the facts of Servier and the facts of this case. The short of the matter is that Zoetis knew how to perform the invention so as to produce the IVPs and it knew that some of these IVPs were more efficacious than others. Apart from disclosing the possible range of antigens, it did not disclose how to make any of the IVPs. The primary judge correctly concluded that the best method was not disclosed. Ground 1 of the Notice of Appeal should accordingly be rejected.

Ground 6: indeterminacy of best method

71 As a fallback position Zoetis also submits that the concept of the best method of performing the invention is itself inherently indeterminate. For example, as Mr Flynn SC who appeared with Mr Mee of counsel for Zoetis pointed out, different users of the vaccine might wish to have different durations of immunity depending on the planned life cycles of the pigs in question. And, as the expert evidence showed, the most expensive element in a vaccine is the antigens. It followed that there could be trade-offs between the cost of the antigen concentration and the desired duration of immunity. Possibilities of this kind made it impossible to say that Zoetis knew of a ‘best’ method of performing the invention because what was best rather depended upon what one was trying to achieve with the vaccine. This argument is the subject of Ground 6.

72 The difficulty with this submission is that the question of best method is, on the strength of Servier, to be assessed against the advantages the invention is claimed to bring and not against engaging thought experiments of the kind posed by Mr Flynn. In this case, the promise of the invention is single dose efficacy and suitability for delivery as a combination vaccine. Once that is appreciated, it is straightforward to assess what the best method of performing the invention is. It is the IVP which demonstrated greatest suitability for those two purposes. Since it is clear from the specification that Zoetis had been testing the IVPs to assess, inter alia, those very matters, it necessarily follows that it must have known that one of them delivered best on the promise of the claimed invention. Ground 6 should be rejected.

Ground 3: best starting point

73 In the course of rejecting Zoetis’s submission that the disclosure of a range of antigen concentrations was sufficient to discharge its obligation under s 40(2)(aa), the primary judge observed at J [738] that the person skilled in the art would be required to expend time and money ‘embarking on a program of work to find the best starting point in that range – information that was known to the patentee when the Applications were filed, and information which it kept to itself’. By Ground 3 of its Notice of Appeal Zoetis points out that the primary judge made no finding as to what that best starting point was or what Zoetis considered it to be. In that circumstance, it is said that her Honour erred in concluding that the disclosure of the antigen ranges did not meet the requirements of s 40(2)(aa). We have already explained above why the disclosure of the range of antigen concentrations did not constitute a fair disclosure of the best method known to Zoetis of performing the invention. Ground 3 should be rejected.

Ground 5

74 We have found it difficult to follow Ground 5. In that circumstance, it is worth setting it out:

Further, or alternatively, in circumstances where:

a. the examples in the Applications showed that each of the Ten IVPs was efficacious when administered as a single dose;

b. the primary judge found that the potency of a commercial vaccine may vary over time and between batches (J [701]);

c. the evidence showed that the M. hyo p46 antigen concentration in the Ten IVPs varied over time within a range [see e.g. Annexure 1 to Zoetis’ Closing Submissions]; and

d. the evidence showed that the mean M. hyo p46 antigen concentration of each of the Ten IVPs was within the ranges disclosed in the Applications [see e.g. Annexure 1 to Zoetis’ Closing Submissions],

the primary judge:

e. erred in finding (at J [662], [699] and [730]) that Dr Nordgren gave evidence that the ranges disclosed in the Applications were “not meaningful” or “so broad as to be meaningless”;

f. erred in relying (at J [689] and [694]) on a single tendered document as evidence that “there were accepted values for the antigen concentration of samples at T0 (day zero)”; and

g. ought to have found that the respondent failed to establish that the disclosure of the Applications, including the disclosed antigen concentration ranges, did not satisfy the requirements of s 40(2)(aa) of the Act.

75 The difficulty lies in identifying why the errors alleged in 5(e)–(g) are connected to the matters put forward in (a)–(d) and in thereafter understanding why 5(e)–(g) matter for the disposition of this appeal. If the matters in (a)–(d) are correct then this entails that the 10 IVPs were efficacious as a single dose, that the potency of a commercial vaccine could vary over time and between batches, that the p46 antigen concentration in the IVPs varied over time within a range and that the p46 antigen concentration was within the ranges disclosed in the specifications. The question which arises is whether any of the errors alleged at 5(e)–(g) can be seen to follow from these matters and, if they do, whether this has any relevance to any issue before this Court.

Paragraph 5(e)

76 It is unclear how the matters at 5(a)–(d) can be connected with what is asserted in 5(e), i.e., why those matters mean that the primary judge erred in concluding that Dr Nordgren gave evidence that the ranges were not meaningful. Evidently, Zoetis itself encountered a similar problem since in its written submissions it does not rely upon 5(a)–(d) to make good the error alleged in 5(e). Instead, it submits that there was no evidence to support the finding alleged in 5(e).

77 That submission does have the virtue of being readily understood, but it lies outside Ground 5 of the Notice of Appeal which does not suggest at Ground 5(e) or anywhere else that the primary judge erred in law by making a finding of fact for which there was no evidence. Zoetis also submits that the factual finding at J [662] and [730] was in error because Dr Nordgren had said no such thing (we leave aside J [699] which is only a faithful recitation of Boehringer’s submission on the point). The submission refers to Dr Nordgren’s second affidavit and, in particular, to a section 25 pages in length running from §§115–176. Review of this material suggests that Dr Nordgren did not say that the range was so broad as to be meaningless. Boehringer submits that the same paragraphs did support her Honour’s finding but did not identify where in §§115–176 the relevant evidence was to be found. Neither party suggested that the transcript of Dr Nordgren’s cross-examination should be consulted. In those circumstances we conclude that, had the no evidence point actually been part of the Notice of Appeal, it ought to have been upheld.

78 At this point, however, a further difficulty would then have come into view. Why does it matter that the primary judge erred in accepting that the ranges were so broad as to be meaningless? The question before this Court is whether Zoetis had disclosed the best method known to it of performing the invention. Perusal of the primary judge’s dispositive reasoning at J [726]–[744] shows that her Honour concluded that, because the antigen concentration of the IVPs had not been disclosed in the specifications, Boehringer’s best method challenge was made good. That conclusion is unrelated to whether or not the range was too broad to be meaningful. It is true that the primary judge said this at J [730]:

Rather than providing the key, the Applications instead refer to a broad range of the antigen concentrations, expressed as absolute concentrations (in µg antigen/ml), within which the concentration preferably lies. Dr Nordgren described the range as being so broad as to be meaningless.

79 However, the breadth of the range and its meaningfulness are not connected to her Honour’s dispositive reasoning. Thus, Ground 5(e) appears to go nowhere. We would reject Ground 5(e) on the basis that it is not relevant to the outcome of the appeal and because the alleged error cannot follow from the matters in Grounds 5(a)–(d). We would not uphold the no evidence point which is outside the terms of Ground 5(e).

Grounds 5(f) and 5(g)

80 Ground 5(f) is explained in Zoetis’s submissions in these terms:

The primary judge found that antigen concentration of commercial vaccines may vary over time and between batches: J [701]. In addition, each of AT264, AT308 and AT112 demonstrated significant variation in measured antigen concentration between samples, between technicians and over time. In those circumstances, the primary judge erred in finding that there were “accepted values” for antigen concentration at day 0: J [689], [694].

81 The first sentence matches up with Ground 5(b) and the second sentence with Ground 5(c). The invitation in Ground 5(f) is to reverse the primary judge’s factual finding on the basis of those two matters. The relevant findings are at J [689] and [694]:

689 In an email to the Zoetis vaccine development team dated 20 April 2012, the principal scientist sent the mean p46 values for serials LK1211RK09 and L1211RK15 in micrograms per ml, as measured on day zero, noting that serial LK1211RK09 was formulated at 1.5x that of serial L1211RK15.

…

694 However, by the time L1211RK15 was selected as the qualifying serial in late March 2013 and it was being used as the reference against which the relative potencies of other samples were being tested against, there were accepted values for the antigen concentration of samples at T0 (day zero).

82 As articulated in Ground 5(f) the error alleged consists of making these findings in reliance on a single tendered document. One may struggle to understand what it is that Ground 5(f) is driving at. However, as developed by Mr Flynn the point is that it was erroneous to think that the IVPs had particular antigen concentrations because the evidence showed that their antigen concentrations varied within a range. The variation was caused by the identity of the scientists who performed the formulation of the IVPs together with other matters such as time. For example, in the case of the reference vaccine there was a 1.2 µg/mL variation in the antigen concentration depending upon which scientist had done the measuring. Viewed in that light, Zoetis submits the primary judge’s conclusion at J [689] and [694] that the IVPs did have accepted values for antigen concentrations was in error.

83 Why this would matter is not elucidated in Zoetis’s submission extracted above. As developed by Mr Flynn in his address, however, the point seems to be this. If the IVPs were themselves defined by ranges of antigen concentrations rather than specific antigen concentrations then it was reasonable to disclose a range of antigen concentrations in the specification (as had been done): T29.31. This submission appears to relate to Ground 5(g). A second string to this argument is the contention that if one combined the antigen variations of the 10 IVPs one ended up with a range of antigen concentrations which was very similar to the disclosed range of antigen concentrations in the specification: T31.1. Again, this second variant appears to relate to Ground 5(g).

84 We do not see why this matters. The question is not whether it was reasonable to disclose in the specification a range of antigen concentrations (as was done). No one suggests that it was unreasonable and the primary judge was satisfied that the invention was enabled across that range. The question is instead whether the IVPs constituted a method of performing the invention and whether, if they did, they concealed between them the best method known to Zoetis of performing the invention. We have already explained why we agree with the primary judge that it was not necessary for Boehringer to identify which of the IVPs was the best method (because they had been compared against each other and were found to have varying efficacies). Once one accepts that, it does not matter whether the IVPs are defined by a specific antigen concentration or instead by a range of antigen concentrations resulting from variable matters such as the scientist doing the trial. Zoetis’s submissions under Ground 5(f) do not detract from the primary judge’s process of reasoning even if one accepts that there was an error.

85 It is no doubt for this reason that the primary judge did not address the evidence to which Mr Flynn took this Court in contending that the IVPs were defined by ranges of antigen concentrations. On the primary judge’s analysis, any such variability in the antigen concentration of the IVPs does not matter. Since we also do not think that it matters, it is not necessary to determine whether the primary judge’s reliance upon the single document referred to in Ground 5(f) was in error.

86 Grounds 5(f) and 5(g) should be rejected.

Ground 7

87 By Ground 7 Zoetis contends that the primary judge erred in reasoning as follows:

739 Zoetis’ focus on the precision of the pleadings and requiring Boehringer to nominate its IVP choice as the “best” as its answer to the best method challenge is at odds with the obligation of good faith. By doing so, the best method case became more akin to a game of battleship, wherein the challenger, not blessed with the patent applicant’s full knowledge of the in-house research and development work and context leading to the choice of the commercial product, is forced to nominate IVP’s as the “best method” known to the Patent Applicant. Ultimately, this was irrelevant as, whichever of the IVPs nominated, absolute concentration details were not provided for any of the antigens in them.

740 Zoetis’ demand that Boehringer define “best” was also not in keeping with its good faith requirement. When it filed the Applications, Zoetis knew the “key”, the absolute concentration of the reference IVP, and chose to keep it to itself.

88 There are said to be two errors in these paragraphs. The first is that the primary judge impermissibly considered the manner in which Zoetis conducted its defence, and in particular its insistence that Boehringer nominate one IVP as the best method and define what ‘best’ meant, in reasoning to her Honour’s conclusions on best method. Even if these considerations were irrelevant, however, they were but inputs into her Honour’s remarks concerning good faith. Those remarks are the subject of the second alleged error and for the reasons given at [93] below were immaterial to her Honour’s conclusion. Accordingly, so too was any error in relation to these considerations.

89 The second error is said to lie in thinking that there was an obligation of good faith that could extend to the manner in which Zoetis conducted its defence. Section 40(2)(aa) does not refer to good faith. Nevertheless, it has been said, most recently by the Full Court of this Court, that ‘principles of good faith underlie the best method requirement’: Servier at 89 [108]. We would prefer to focus on the language of s 40(2)(aa) which does not mention good faith. Introducing a concept as one which ‘underlies’ a statutory provision is apt to replace the words which appear on the page with words which do not. Across multiple fields of law, experience shows that this is unwise.

90 Whilst it is not to be doubted that historically good faith on the patent applicant’s part explains why the best method known to the patent applicant needs to be disclosed, it does not seem to assist analytically in any particular case. The best method known to the patent applicant is either disclosed or it is not disclosed. If it is disclosed, then bad faith on the part of the patent applicant is irrelevant. If it is not disclosed, then its good faith is likewise irrelevant. Put another way, debating the bona fides of the patent applicant is incapable of bearing upon the question the statute poses.

91 In our respectful opinion, this case illustrates the perils of intermingling the words which appear in a statute with words which do not. The Full Court’s observation in Servier that principles of good faith underlie the obligation is not a statement that the obligation is one of good faith or that s 40(2)(aa) imposes such an obligation. The primary judge’s reasoning at J [739]–[740] above, however, shows that her Honour elided the statutory best method obligation with a good faith obligation which does not exist except insofar as it historically explains the origins of s 40(2)(aa).

92 Even if all of that were wrong so that s 40(2)(aa) was to be read as imposing a good faith obligation, this would be an obligation imposed on the patent applicant in relation to the contents of the specification. J [739]–[740] show that the primary judge conceived that the (non-existent) obligation of good faith went well beyond what a patent applicant was to include in a specification and extended to the manner in which it conducted litigation many years after the grant of the patent. With respect to the primary judge, this cannot be correct. We therefore accept Zoetis’s submission under Ground 7 that paragraphs J [739]–[740] disclose error.

93 However, to accept that the primary judge erred in this way directs attention to whether the error was material to her Honour’s conclusions. We do not think that it was. J [739]–[740] betray evident annoyance at the manner in which Zoetis conducted its defence. But it is plain that her Honour’s dispositive reasons for upholding the best method challenge were unrelated to any lack of good faith on Boehringer’s part. That reasoning was that Zoetis had not disclosed the antigen concentration of the reference vaccine so that the skilled addressee was not enabled to make the IVPs, one or more of which was the best method known to Zoetis of making the composition. Since the error is immaterial to the outcome we would reject Ground 7.

Ground 8

94 Ground 8 is as follows:

Further or alternatively, having assumed that the patent applicant “considers that including IVPs in the examples in the Application, in combination with the disclosed ranges, satisfy its obligation to include the best method known to it at the time of filing” (J [735]), the primary judge erred in finding that the disclosure of the Applications did not satisfy the requirements of s 40(2)(aa) of the Act.

95 This focusses on J [735] which is as follows:

Zoetis was not obliged to identify the best method as such in the Applications. I am prepared to assume that Zoetis considers that including IVPs in the examples in the Applications, in combination with the disclosed ranges, satisfy its obligation to include the best method known to it at the time of filing.

96 Zoetis submits that it is implicit in J [735] that the primary judge was not satisfied that Zoetis held back an absolute antigen concentration within the range that Zoetis knew or believed to be better than the disclosed range. We do not agree that this is implicit at all. J [735] must be read with J [736]–[738]:

736 However, I consider that Zoetis has chosen to hide the best method in plain sight in each of the Applications. At first glance it appears that details, including concentration, are provided for the IVPs discussed in the examples. It is only when the skilled reader goes looking for the concentration information for the reference sample against which all the relative concentrations are given that it is apparent that information — the key to the relative concentrations — is not provided anywhere in the Applications.

737 Keeping the key to itself is contrary to the obligation of good faith which, as the authorities emphasise, is fundamental to the best method requirement.

738 Zoetis’ response, that the concentration ranges provided in the Applications are sufficient, is not an answer. The person skilled in the art seeking to make the invention at the expiry of the patents granted on the Applications would be forced to expend time and money embarking on a program of work to find the best starting point in that range – information that was known to the patentee when the Applications were filed, and information which it kept to itself.