FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Alumina and Bauxite Company Ltd v Queensland Alumina Ltd [2024] FCAFC 142

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellants pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 This appeal relates to sanctions imposed by the Australian Government in mid-March 2022 against Russia and certain Russian business-people pursuant to the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 (Cth) and the Autonomous Sanctions Regulations 2011 (Cth) (the Regulations). There are two relevant sanctions:

(a) a sanction (the Export Sanction) imposed by the combined effect of regs 4 and 12 of the Regulations and the Autonomous Sanctions (Export Sanctioned Goods—Russia) Designation 2022 (Cth) (made under reg 4(3)); and

(b) a sanction (the Designated Persons Sanction) imposed by the combined effect of reg 14 of the Regulations and the Autonomous Sanctions (Designated Persons and Entities and Declared Persons—Russia and Ukraine) Amendment (No 7) Instrument 2022 (Cth) (made under reg 6(a)),

(together, the Russia Sanctions). The sanctions referred to above commenced on 20 March 2022 and 18 March 2022 respectively.

2 The appellants (the Russian parties), who were the applicants at first instance, are: Alumina and Bauxite Company Ltd (ABC), Rusal Limited and JSC Rusal. These companies are subsidiaries of United Company Rusal IPJSC (UC Rusal), which is registered as an international public joint stock company in the Russian Federation.

3 The respondents, who were the respondents at first instance, are:

(a) Queensland Alumina Ltd (QAL), an Australian company that operates an alumina refinery in Gladstone, Queensland (the Gladstone Plant); and

(b) five companies that are part of the Rio Tinto Group: RTA Holdco Australia 5 Pty Ltd (RTA Holdco), Rio Tinto Aluminium (Holdings) Limited, Rio Tinto Limited, Rio Tinto Plc and Rio Tinto Aluminium Limited (RTA) (collectively, the Rio parties).

4 QAL operates the Gladstone Plant under an agreement (the Participants Agreement) with the Russian parties and the Rio parties. The business venture between QAL, the Russian parties and the Rio parties may be described as the Gladstone alumina joint venture, using that expression in a non-technical sense.

5 UC Rusal and its subsidiaries (the Rusal Group) engage in business activities involving bauxite and nepheline mining, alumina production, electrolytic production of primary aluminium, and the production of value-added aluminium products. The Rusal Group is Russia’s only primary aluminium producer and currently operates nine aluminium smelters in Russia. Each of Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg, who are referred to in the Designated Persons Sanction, indirectly holds significant shareholdings in UC Rusal.

6 Under the Participants Agreement, QAL refines bauxite into alumina on a toll basis for ABC, RTA Holdco and RTA (collectively, the Participants). ABC holds 20% of the shares in QAL and RTA Holdco and RTA collectively hold 80%.

7 QAL, the Russian parties and the Rio parties are also parties to a series of Tolling Contracts, under which a percentage of the capacity of the Gladstone Plant is allocated to each Participant. There are five Tolling Contracts because new contracts were made at various times when the capacity of the Gladstone Plant was increased. The contracts are in substantially the same terms.

8 The Rio parties have also entered into the following agreements with the Russian parties relating to the supply of bauxite to ABC and the shipment of the bauxite to the Gladstone Plant for processing into alumina:

(a) the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement and the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement, both dated 16 February 2022, under which RTA supplies bauxite from its mines in Cape York, Queensland and Gove, Northern Territory, to ABC to be processed into alumina at the Gladstone Plant; and

(b) the Shipping Agreement dated 31 December 2021, under which RTA ships the bauxite that has been supplied to ABC to the Gladstone Plant.

9 On 4 April 2022, QAL invoked Art 14A of the Participants Agreement and implemented the “step-in” arrangements pursuant to that article in reliance upon the Russia Sanctions. Article 14A provides that the step-in arrangements in Appendix E to the Participants Agreement apply if, relevantly, an Australian Government authority imposes sanctions “on” UC Rusal, ABC or any of their “affiliates” that are likely to prevent QAL from undertaking business activity with ABC and its affiliates. The effect of the step-in arrangements was to reallocate ABC’s entitlement to refine bauxite into alumina at the Gladstone Plant to RTA and RTA Holdco, and thereby exclude ABC from participation in the Gladstone alumina joint venture for the duration of the Russia Sanctions. From 11.59 pm on 4 April 2022 (AEST), QAL ceased to accept bauxite deliveries from ABC and ceased to refine and deliver alumina to ABC in accordance with the Participants Agreement and the Tolling Contracts.

10 On 8 April 2022, RTA invoked “force majeure” provisions in the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and the Shipping Agreement in reliance upon the Russia Sanctions. Since then, RTA has ceased to supply bauxite or shipping services to ABC under those agreements.

11 On 17 August 2022, the Russian parties commenced the proceeding at first instance against QAL and the Rio parties seeking declaratory and injunctive relief and damages. The Russian parties alleged that, in the circumstances that pertained on and since 18 March 2022, the acceptance of bauxite by QAL from ABC, the refining of alumina by QAL for ABC, and the delivery of alumina by QAL to ABC for sale to third parties outside Russia, did not amount to a contravention by QAL of the Russia Sanctions and that Art 14A of the Participants Agreement was not applicable. The Russian parties alleged that QAL had breached its contractual obligations under the Participants Agreement and the Tolling Contracts by ceasing to deliver alumina to ABC pursuant to those agreements. The Russian parties further alleged that the Rio parties had breached their contractual obligations under the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and the Shipping Agreement by ceasing to supply and ship bauxite to ABC at the Gladstone Plant pursuant to those agreements.

12 The hearing before the primary judge occupied seven days. On the last day of the hearing, the Russian parties proffered undertakings (the Rusal Group Undertaking) to the Court which, they submitted, would remove any risk that ABC’s continuing participation in the Gladstone alumina joint venture would result in contraventions of the Russia Sanctions.

13 On 1 February 2024, the primary judge dismissed the Russian parties’ amended originating application and published reasons for judgment: Alumina and Bauxite Company Ltd v Queensland Alumina Ltd [2024] FCA 43 (the Reasons). The primary judge concluded, in summary:

(a) on the balance of probabilities, at all times on and after 20 March 2022, the delivery of alumina by QAL to ABC would have been contrary to the Export Sanction (Reasons, [250], [290]);

(b) on the balance of probabilities, at all times on and after 19 March 2022, the production of alumina by QAL for ABC and the delivery of the alumina to ABC would have been contrary to the Designated Persons Sanction (Reasons, [288], [291]);

(c) Art 14A of the Participants Agreement was not engaged because:

(i) the Export Sanction was not a sanction imposed “on” UC Rusal, ABC or their affiliates (Reasons, [323], [342]);

(ii) although the Designated Persons Sanction was imposed “on” Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg, neither of them was an “affiliate” of UC Rusal (or ABC) within the meaning of Art 14A (Reasons, [334], [342]);

(d) as a result of the conclusions in (a) and (b) above, the defence of supervening illegality was available to QAL (Reasons, [359], [365]);

(e) as a result of the conclusions in (a) and (b) above, the Russia Sanctions were an event of force majeure within the meaning of Art 17 of the Tolling Contracts (Reasons, [362], [365]);

(f) RTA was relieved of its obligations to supply and ship bauxite to ABC at the Gladstone Plant by the operation of:

(i) the force majeure provisions in Art 21 of the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, Art 18.1 of the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and cl 11.1 of the Shipping Agreement (Reasons, [381]); and

(ii) the “sanctions provisions” in Art 26.2 of the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, Art 19.3(b) of the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and cl 12.2 of the Shipping Agreement (Reasons, [410]); and

(g) without deciding the question of the Court’s power to accept the Rusal Group Undertaking, the undertaking should not be accepted by the Court as a basis on which the Court would grant declaratory and injunctive relief on a prospective basis (Reasons, [432]).

14 The Russian parties appeal from the whole of the judgment of the primary judge. By their notice of appeal, they raise eight grounds. The Russian parties accept that they need to succeed on all of grounds 1, 2 and 3 in order to succeed in the appeal (T19). The grounds can be summarised as follows:

(a) the primary judge erred in concluding that, on and after March 2022, alumina delivered by QAL to ABC would have been exported to Russia for use in aluminium smelters owned and operated by UC Rusal (and for the benefit of Russia) in contravention of the Export Sanction (ground 1);

(b) the primary judge erred in concluding that, on a proper construction of the Export Sanction, a transfer of alumina by ABC and/or UC Rusal otherwise than to Russia would directly or indirectly result in a transfer of alumina for the benefit of Russia in contravention of the Export Sanction (ground 2);

(c) the primary judge erred in concluding that the production of alumina by QAL for ABC and the delivery of the alumina to ABC pursuant to the parties’ contractual arrangements would constitute directly or indirectly making an asset available to, or for the benefit of, Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg in contravention of the Designated Persons Sanction (ground 3);

(d) by reason of the matters outlined in grounds 1 to 3, the primary judge erred in holding that the doctrine of supervening illegality applied to excuse QAL from its performance obligations under the Participants Agreement and the Tolling Contracts (ground 4);

(e) by reason of the matters outlined in grounds 1 to 3, the primary judge erred in holding that the force majeure clauses in the Tolling Contracts applied to excuse QAL from failing to perform the Tolling Contracts (ground 5);

(f) by reason of the matters outlined in grounds 1 to 3, the primary judge erred in holding that the force majeure clauses in the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and the Shipping Agreement applied entitling RTA to refuse to perform its obligations thereunder (ground 6);

(g) by reason of the matters outlined in grounds 1 to 3, the primary judge erred in holding that the sanctions provisions of the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and the Shipping Agreement applied entitling RTA to refuse to perform its obligations thereunder (ground 7);

(h) by reason of the matters outlined in grounds 1 to 7:

(i) the Russian parties were entitled to the declaratory and injunctive relief sought and there was no occasion to consider that undertakings should form a necessary condition of any relief sought;

(ii) in any event, the exercise of discretion by the primary judge with respect to the undertakings proffered by the Russian parties miscarried, such that if and to the extent that undertakings are considered a necessary condition of any relief sought, such discretion is liable to be re-exercised according to law and favourably to the appellants

(ground 8).

15 In relation to ground 8, we note that, at the hearing of the appeal, the Russian parties said that they were not proffering comparable undertakings to those proffered in the proceeding at first instance (T37).

16 QAL and the Rio parties have each filed a notice of contention by which they contend that the judgment of the primary judge should be affirmed on additional bases. The grounds relied on include grounds that can be summarised as follows:

(a) the primary judge’s conclusion that the Export Sanction applied (that is the subject of challenge by ground 2 of the notice of appeal) should be affirmed on the additional basis that the availability in Russia of alumina (that would otherwise not be available) is by itself a benefit for Russia within the meaning of the Export Sanction (ground 1 of QAL’s notice of contention); and

(b) Art 14A of the Participants Agreement applied because, within the meaning of that Article:

(i) the Export Sanction was a sanction imposed “on” UC Rusal and/or ABC; and the Export Sanction was likely to prevent QAL from undertaking business activity with ABC; and/or

(ii) Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg were “affiliates” of UC Rusal and/or ABC; the Designated Persons Sanction was imposed on them; and the Designated Persons Sanction was likely to prevent QAL from undertaking business activity with ABC,

(ground 2 of QAL’s notice of contention and ground 1 of the Rio parties’ notice of contention) (the Art 14A issue). For the contention based on Art 14A to succeed, it is sufficient for QAL and the Rio parties to establish either (i) or (ii) in paragraph (b) above.

17 For the reasons that follow, we have concluded in summary that:

(a) ground 1 is not made out;

(b) ground 2 is not made out (including on the basis of ground 1 of QAL’s notice of contention);

(c) it is therefore unnecessary to determine ground 3;

(d) it follows from our conclusions that grounds 1 and 2 are not made out that grounds 4 to 8 are not made out.

18 Although it is not necessary for our decision to consider the Art 14A issue, we consider it appropriate to deal with it in part, as it has practical significance for the parties. In our view, Art 14A was engaged on the basis that: the Export Sanction was a sanction imposed “on” ABC; and the Export Sanction was likely to prevent QAL from undertaking business activity with ABC. To that extent we respectfully differ from the conclusions of the primary judge. It is unnecessary to consider, and we do not consider, the question whether Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg were “affiliates” of UC Rusal or ABC within the meaning of Art 14A.

19 The appeal is therefore to be dismissed.

Background facts

20 The following statement of the background facts is substantially based on the Reasons. The background facts set out in this section were not the subject of challenge in the appeal.

Global trade in alumina

21 Alumina is aluminium oxide and is usually produced as a white crystalline powder. Aluminium smelters require a continuous supply of alumina. The primary aluminium smelting process is a high-temperature, fully continuous process that takes place in large electrolytic cells. Each cell is connected in series through an electrical circuit to a number of other cells, collectively known as a potline. For an aluminium smelter to forcibly shut down an entire potline, the losses incurred are substantial. For that reason, smelters hold sufficient alumina inventory to avoid short-term disruptions.

22 Approximately 139 million tonnes of alumina (chemical and metallurgical grade) were produced globally in 2021, from an estimated world alumina capacity of 153 million tonnes per annum. China was the largest alumina-producing country in 2021, at approximately 75.3 million tonnes, accounting for 54% of the world total. Australia was the second largest, producing approximately 20 million tonnes, with the third largest being Brazil at over 10 million tonnes. Together, these three countries accounted for 77% of the world’s 2021 production.

23 Over the past decade, China consolidated its dominant position as the world’s largest alumina producer, by steadily growing its domestic capacity. In 2014, China’s total refining capacity accounted for over half the world’s total for the first time, and its proportion has been increasing ever since, reaching 54% in 2021. China became a significant net exporter of alumina in 2018, before swinging back to a net importer in 2019.

24 Australia’s 2021 alumina production was 20.4 million tonnes, of which an estimated 89% was exported.

25 Alumina can be considered as fungible, meaning it is interchangeable or replaceable with other alumina; this is the basis on which global alumina is traded, contracts can be swapped and material interchanged in different parts of the world. While alumina is considered to be fungible, different alumina refineries do produce alumina of different qualities, different levels (and types) of impurities and different crystalline structure.

26 Alumina is regularly stored in bonded warehouses prior to completing customs clearance requirements or waiting to be on-sold. Storage times in bonded warehouses are often measured in weeks and months depending on market conditions at the time.

27 As China began to emerge as the world’s largest producer and consumer of alumina, global trade patterns began adjusting to accommodate a new global supply/demand balance. The result is in effect a dual market, whereby China’s domestic alumina production generally met the requirements of its domestic smelting sector, and alumina supply in the rest of the world (ROW) met ROW smelting demand. The ROW market can be further divided between the Atlantic and Pacific markets, with the difference in prices reflecting supply/demand and freight differentials between the two regions. Heading into 2022, under “steady-state” global alumina market conditions, China’s market was absorbing surplus alumina from the ROW market under favourable economic conditions. In other words, the Chinese alumina market was acting as a “sponge” for surplus alumina produced in the ROW market.

28 Swap arrangements are a common instrument used in the global alumina market. They can be broadly categorised into two groups: planned and unplanned. Planned swaps are usually between two alumina suppliers, which can include refining companies, traders or other groups, and involve swapping of alumina in different geographical regions to save on transport costs and are agreed in advance of production. Unplanned swaps are between suppliers typically on a short-term basis to cover some unforeseen set of circumstances that have led to either a shortage or oversupply of alumina emerging in a specific location.

Russia’s aluminium industry and UC Rusal’s business operations

29 The Rusal Group engages in business activities involving bauxite and nepheline mining, alumina production, electrolytic production of primary aluminium, and the production of value-added aluminium products. UC Rusal conducts its business activities globally, including in Armenia, Australia, Germany, Guinea, Guyana, the Republic of Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Nigeria, Russia, Sweden and Ukraine.

30 UC Rusal owns eleven aluminium smelters, of which nine are in Russia, one is in Sweden, and one is in Nigeria (which is currently idle). A tenth Russian smelter commenced operations at the end of 2021, but is only running at a very low production rate because of market conditions (making aluminium production unprofitable). In the financial year ending 31 December 2022, UC Rusal’s Russian smelters had a requirement for 7.9 million tonnes of alumina. UC Rusal is Russia’s only primary aluminium producing company.

31 UC Rusal owns ten alumina refineries, of which four are in Russia, two are in Jamaica, one is in Ireland, one is in Ukraine, one is in Italy, and one is in Guinea. The Mykolaiv refinery in Ukraine ceased operating on 26 February 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Prior to that, it produced approximately 1.75 million tonnes of alumina per annum of which about 98% was supplied to UC Rusal’s aluminium smelters in Russia.

32 Through ABC, UC Rusal also has an interest in the Gladstone Plant operated by QAL. Immediately prior to April 2022, ABC received an annual entitlement of 760,000 tonnes of alumina from the Gladstone alumina joint venture.

33 Pursuant to a contract of sale entered into on 15 September 2005, ABC sold all of the alumina produced at the Gladstone Plant to which it was entitled to another subsidiary of UC Rusal, namely Rual Trade Limited. Under that contract, the purchaser obtained title to the alumina once it passed the ship’s rail at QAL’s wharf.

34 On 5 December 2012, the purchase obligations under that contract of sale were novated to a different subsidiary of UC Rusal, RTI Limited (RTI), by a deed of novation. On 23 November 2018, the term of the contract of sale (now with RTI) was extended to 31 December 2025. Thus, as at March/April 2022, ABC had sold all of the alumina produced at the Gladstone Plant to which it was entitled to RTI.

35 Prior to the imposition of the Russia Sanctions, UC Rusal also acquired a further 750,000 tonnes of alumina from Australia under swap agreements with Rio Tinto, Glencore International AG and Norsk Hydro. The purpose of those arrangements was to optimise the logistics of alumina supply to UC Rusal’s subsidiaries in Russia. The swap arrangement with Rio Tinto involved the swap of alumina produced at UC Rusal’s Aughinish refinery in Ireland for alumina produced by Rio Tinto in Australia. The swap was suspended on 21 March 2022. The swap arrangement with Norsk Hydro involved a swap of alumina produced at different locations in Australia. That arrangement was suspended on 18 March 2022.

36 Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, UC Rusal lost the supply of approximately 3.4 million tonnes per annum of alumina in aggregate from the Mykolaiv refinery and from Australia, which equated to approximately 40% of UC Rusal’s Russian requirements. At that time, UC Rusal became a net purchaser of alumina, rather than a seller of alumina. It acquired alumina from traders, including alumina sourced in China, as well as through its own subsidiary based in China. Alumina acquired in China is able to be transported to Russia by truck or barge.

37 According to China Customs data, Russia imported approximately 1.1 million tonnes of alumina from China over the 14-month period ending February 2023.

The Gladstone alumina joint venture

38 QAL is the owner and operator of an alumina refinery in Gladstone, Queensland. QAL’s facilities include the refinery, two storage sheds and a wharf known as South Trees.

39 QAL receives bauxite from ABC and the Rio Tinto companies, RTA Holdco and RTA, and processes that bauxite into alumina on a toll basis for those companies. QAL’s operations are governed by the Participants Agreement and the Tolling Contracts. The parties to those agreements are QAL, the Russian parties and the Rio parties. The Participants Agreement has been amended and restated a number of times. The Tolling Contracts have also each been restated and extended a number of times.

40 Article 2 of the Participants Agreement states the purpose of the Gladstone alumina joint venture in the following terms:

ARTICLE 2. The Project. The Participants (or their predecessors in interest) formed QAL for the sole purpose of constructing the Gladstone Plant at Gladstone, Queensland, Australia, and thereafter operating it for the conversion into alumina, on a toll basis, of bauxite owned by the Participants. Title to the bauxite furnished by a Participant, the material in process and the alumina into which it is converted shall at all times remain in that Participant. Where materials are commingled in transportation, storage or processing, a Participant shall have an undivided interest in such materials.

41 QAL refines approximately 3.65 million tonnes of alumina per year. QAL delivers and loads the processed alumina on board vessels chartered or owned by the Participants at the eastern end of its wharf which is known as South Trees East.

42 Prior to the imposition of the Russia Sanctions in March 2022, the vast majority of alumina produced for ABC at the Gladstone Plant was shipped to Russia.

Domicile, ownership and governance of the Russian parties and UC Rusal

43 ABC is incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. It is an indirect wholly-owned subsidiary of UC Rusal. Each of Rusal Limited and JSC Rusal are also wholly-owned subsidiaries of UC Rusal. Rusal Limited is incorporated in Jersey and JSC Rusal is incorporated in the Russian Federation.

44 The primary judge implicitly accepted, and it does not appear to have been in issue, that ABC was economically dependent upon the Rusal Group, ABC’s operating and financing decisions and a significant part of its transactions and settlements were controlled by UC Rusal, and UC Rusal had the power to direct the transactions of ABC at its discretion and for the group’s benefit.

45 UC Rusal was incorporated in Jersey and, until December 2020, known as United Company Rusal Plc. Also prior to December 2020, UC Rusal was a tax resident in Cyprus and managed and controlled from Cyprus. In December 2020, UC Rusal was redomiciled from Cyprus to Russia and is now registered in the Russian Federation and known as United Company Rusal IPJSC.

46 UC Rusal’s shares are listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and the Moscow Exchange. UC Rusal is a tightly held public company with the two largest shareholders being En+ (holding approximately 56.88%) and SUAL Partners ILLC (SUAL) (holding approximately 25.52%). The public hold only 17.59% of the issued shares. En+ is a company registered as an international public joint stock company in the Russian Federation. Its shares are listed on the Moscow Exchange. SUAL is an international limited liability company incorporated in the Russian Federation.

47 Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg are significant indirect shareholders of UC Rusal and thereby ABC. Given the bases upon which we have determined the appeal, it is not necessary to detail the nature and extent of Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg’s indirect shareholdings.

OFAC Sanctions (2018)

48 On 6 April 2018, the United States Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated Mr Deripaska and entities associated with him including En+ and UC Rusal, and Mr Vekselberg and entities associated with him comprising the Renova Group, on OFAC’s list of “Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons” (SDN List) pursuant to Executive Order 13661 of 16 March 2014 (Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine) and Executive Order 13662 of 20 March 2014 (Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine) (the OFAC Sanctions). A press release dated 6 April 2018 issued by OFAC included the following statements:

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), in consultation with the Department of State, today designated seven Russian oligarchs and 12 companies they own or control, 17 senior Russian government officials, and a state-owned Russian weapons trading company and its subsidiary, a Russian bank.

“The Russian government operates for the disproportionate benefit of oligarchs and government elites,” said Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin. “The Russian government engages in a range of malign activity around the globe, including continuing to occupy Crimea and instigate violence in eastern Ukraine, supplying the Assad regime with material and weaponry as they bomb their own civilians, attempting to subvert Western democracies, and malicious cyber activities. Russian oligarchs and elites who profit from this corrupt system will no longer be insulated from the consequences of their government’s destabilizing activities.”

…

All assets subject to U.S. jurisdiction of the designated individuals and entities, and of any other entities blocked by operation of law as a result of their ownership by a sanctioned party, are frozen, and U.S. persons are generally prohibited from dealings with them. Additionally, non-U.S. persons could face sanctions for knowingly facilitating significant transactions for or on behalf of the individuals or entities blocked today.

…

Oleg Deripaska is being designated pursuant to E.O. 13661 for having acted or purported to act for or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, a senior official of the Government of the Russian Federation, as well as pursuant to E.O. 13662 for operating in the energy sector of the Russian Federation economy. Deripaska has said that he does not separate himself from the Russian state. He has also acknowledged possessing a Russian diplomatic passport, and claims to have represented the Russian government in other countries. Deripaska has been investigated for money laundering, and has been accused of threatening the lives of business rivals, illegally wiretapping a government official, and taking part in extortion and racketeering. There are also allegations that Deripaska bribed a government official, ordered the murder of a businessman, and had links to a Russian organized crime group.

…

Viktor Vekselberg is being designated for operating in the energy sector of the Russian Federation economy. Vekselberg is the founder and Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Renova Group. The Renova Group is comprised of asset management companies and investment funds that own and manage assets in several sectors of the Russian economy, including energy. In 2016, Russian prosecutors raided Renova’s offices and arrested two associates of Vekselberg, including the company’s chief managing director and another top executive, for bribing officials connected to a power generation project in Russia.

…

EN+ Group is being designated for being owned or controlled by, directly or indirectly, Oleg Deripaska, B-Finance Ltd., and Basic Element Limited. EN+ Group is located in Jersey and is a leading international vertically integrated aluminum and power producer.

…

United Company RUSAL PLC is being designated for being owned or controlled by, directly or indirectly, EN+ Group. United Company RUSAL PLC is based in Jersey and is one of the world’s largest aluminum producers, responsible for seven percent of global aluminum production.

…

Renova Group is being designated for being owned or controlled by Viktor Vekselberg. Renova Group, based in Russia, is comprised of investment funds and management companies operating in the energy sector, among others, in Russia’s economy.

49 During 2018, En+ and UC Rusal negotiated with OFAC for their removal from the SDN List. On 19 December 2018, En+, UC Rusal and OFAC entered into an agreement by which En+ and UC Rusal agreed a number of measures (relating to shareholdings, voting of shares, director positions and dividend payments) and OFAC agreed to remove En+ and UC Rusal from the SDN List. The agreement contained requirements for an annual audit and a monthly certification of compliance, and an obligation to inform OFAC of any changes to the ownership and control of En+ and UC Rusal.

50 On 27 January 2019, OFAC publicly announced the removal of En+ and UC Rusal from the SDN List with immediate effect. The removal was subject to and conditional upon the satisfaction of a number of conditions including the fulfilment of the agreement with OFAC. The inclusion of En+ and UC Rusal on the SDN List, and their subsequent removal, were also publicly disclosed by each of those companies in their annual reports and in an announcement by UC Rusal to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

51 In the absence of evidence to the contrary adduced by the respondents, the primary judge inferred that QAL and the Rio parties were aware of the above disclosures made by OFAC, En+ and UC Rusal. The Rio Tinto Group engages in international trade where it is necessary to be familiar with sanction regimes imposed by different countries. The primary judge inferred that both QAL and the Rio parties would have been acutely conscious of the effect of the OFAC Sanctions on UC Rusal given its involvement in the Gladstone alumina joint venture.

52 The 2018 annual report for En+ was published in about April 2019 (the report discloses that the Board of Directors approved it on 26 April 2019). The OFAC Sanctions are referred to and described in many parts of that annual report. The first page of the annual report contains the following disclosures:

During 2018, the Company’s business was impacted by the imposition of the OFAC Sanctions (defined below) beginning in April of 2018 and lasting through to the end the year. The OFAC Sanctions were lifted from the Company on 27 January 2019. The Company has since adopted an enhanced compliance program and mechanisms, including at the Board level, to facilitate ongoing compliance with US sanctions and requirements following the removal of sanctions from the Company and its subsidiaries.

…

Shareholders and potential investors should be aware that on 6 April 2018, the Office of Foreign Assets Control of the Department of the Treasury of the United States of America (the “OFAC”) designated certain persons and certain companies which are controlled by some of these persons added to its Specially Designated Nationals List (the “OFAC Sanctions”). The designated persons/entities included Mr Oleg Deripaska, a non-executive director of the Company and its ultimate beneficial owner at the time that OFAC imposed sanctions, as well as the Company, United Company RUSAL Plc (“RUSAL”), JSC EuroSibEnergo, and two of the Company’s direct major shareholders at the time, B-Finance Ltd (a BVI company), and Basic Element Limited (a Jersey company), each controlled by Mr Deripaska.

On 27 January 2019, OFAC removed the Company, UC RUSAL Plc, and JSC EuroSibEnergo from the OFAC Sanctions. In removing the Company from the OFAC Sanctions, OFAC stated:

“Under the terms of their removal from OFAC’s List of Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN List”), En+, RUSAL, and ESE have reduced Oleg Deripaska’s direct and indirect shareholding stake in these companies and severed his control. This action ensures that the majority of directors on the En+ and RUSAL boards will be independent directors – including US and European persons – who have no business, professional, or family ties to Deripaska or any other SDN, and that independent US persons vote a significant bloc of the shares of EN+.”

53 The 2018 annual report for UC Rusal was also published in about April 2019 (the Chairman’s Statement was dated 29 April 2019). The OFAC Sanctions are also referred to and described in a number of parts of that annual report. In the notes to the financial statements, the following disclosure appeared:

On 6 April 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) designated, amongst others, the Company, as a Specially Designated National (“SDN”) (the “OFAC Sanctions”).

As a result, all property or interests in property of the Company and its subsidiaries located in the United States or in the possession of U.S. Persons were blocked, must have been frozen, and could not be transferred, paid, exported, withdrawn, or otherwise dealt in. Several general licenses were issued at the time of the designation and later on authorizing certain transactions with the Company, its majority shareholder En+ Group Plc (“En+”), and with their respective debt and equity.

On 27 January 2019 OFAC announced removal of the Company and En+ from OFAC’s SDN List with immediate effect. The removal was subject to and conditional upon the satisfaction of a number of conditions including, but not limited to, corporate governance changes, including, inter alia, overhauling the composition of the Board to ensure that independent directors constitute the majority of the Board, stepping down of the Chairman of the Board, and ongoing reporting and certifications by the Company to OFAC concerning compliance with the conditions for removal.

54 The primary judge inferred from the disclosures set out above that, as at the date the Participants Agreement was amended to insert Art 14A, QAL and the Rio parties were aware of the matters so disclosed.

The Participants Agreement (as amended in 2019)

55 The Participants Agreement was most recently amended and restated pursuant to a Deed of Amendment and Restatement entered into on 31 December 2019. Clause 3.1 of that deed provides that the “Parties agree that the Participants Agreement is amended as shown in markup in the document set out in Schedule 2 and the document set out in Schedule 2 reflects all of the historical amendments to the Participants Agreement”. Schedule 2 is headed “Amended and restated Participants Agreement”. That schedule sets out the current form of the Participants Agreement. Article 14A was first introduced into the Participants Agreement by the amendments made on 31 December 2019.

56 Articles 14 and 14A of the Participants Agreement (as set out in that schedule) provide in part:

ARTICLE 14. Reduced Capacity Percentages and Option Tonnage.

(A) A Participant may, subject to the application of Article 14A, at any time or from time to time reduce the rate at which QAL shall toll bauxite into alumina for its account under any Gladstone Tolling Contract by giving QAL notice in writing, at least 30 days prior to the date the reduction is to become effective, of the desired new rate, expressed as a Reduced Capacity Percentage, and the date the reduction is to be effective. That Participant may thereafter at any time or from time to time further reduce, or increase (to not more than its relevant Call Capacity Percentage), the rate at which QAL shall toll bauxite into alumina for its account under that Gladstone Tolling Contract by giving like notice at least 30 days prior to the date the further reduction or increase is to become effective. If commitments of Available Option Capacity under that Gladstone Tolling Contract declared by such Participant pursuant to Paragraph (B) of this Article 14 have been made to other Participants prior to any such increase, such Participant’s Reduced Capacity Percentage as increased shall not exceed its relevant Call Capacity Percentage reduced to the extent required to give effect to those commitments.

(B) A Participant which has given notice of a Reduced Capacity Percentage under any Gladstone Tolling Contract as provided in Paragraph (A) of this Article 14 may at any time or from time to time, by giving QAL notice in writing, declare that the capacity thereby unused or such portion thereof as the Participant may designate in such notice, expressed as Available Option Capacity, is available for other Participants and shall state the period of time during which that capacity is available.

(C) If any declaration of Available Option Capacity is made as provided in Paragraph (B) of this Article 14, QAL shall promptly give notice thereof to all Participants, expressed in terms of Available Option Tonnage under the relevant Gladstone Tolling Contract and stating the period during which that tonnage is available. Any Participant who desires such Available Option Tonnage shall give QAL notice within 15 days after the date of QAL’s notice, stating the amount of such tonnage which it desires to have produced for its account and the period during which it desires to commit for that production.

…

ARTICLE 14A. Step-In

If at any time, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) or corresponding governmental authority of Australia imposes sanctions on United Company Rusal Plc., ABC or any of their affiliates that are likely to prevent QAL from undertaking business activity with ABC and its affiliates (“Sanctions”), then Appendix E shall apply.

57 Appendix E to the Participants Agreement (as set out in Sch 2 to the deed of 31 December 2019) is headed “Step-in Arrangements” and comprises seven pages. The Appendix commences:

In the event that Article 14A applies, the Participants agree that the arrangements set out in this Appendix E shall operate to:

(a) reallocate ABC’s entitlement to use its capacity at the Gladstone Plant to RTA and Aust Holdco (together, the Rio Tinto Participants), pursuant to Article 14;

(b) ensure the Gladstone Plant can continue to operate at 100% capacity;

(c) ensure the continuation of the operation of the Project in a manner in which ABC’s participation is rendered sufficiently passive so as to ensure regulatory compliance by QAL and the Rio Tinto Participants for the purposes of the Sanctions for the duration of the Sanctions or the term of the Participants Agreement, whichever is the earlier (Term);

(d) to the extent permissible under applicable law, provide for, on a conditional basis (being that QAL and the Rio Tinto Participants would not be exposed to risk of secondary sanctions under U.S. or Australian law), an orderly return to ABCs’ participation in the Gladstone Plant.

Suspension of Gladstone alumina joint venture following the imposition of the Russia Sanctions

58 On 23 March 2022, QAL wrote to ABC stating that it was concerned that it could breach the Designated Persons Sanction if it continued to process bauxite on behalf of ABC and believed it was likely that it would be in breach of the Export Sanction if it continued to deliver alumina to ABC. The letter requested information from ABC with respect to Mr Deripaska’s interests in UC Rusal (and thereby ABC) to enable QAL to determine whether Art 14A of the Participants Agreement had been triggered by the imposition of the Russia Sanctions. Ms Baker, who authored the letter, deposed that at the time of the letter she was not aware of Mr Vekselberg’s interests in UC Rusal.

59 On 24 March 2022, ABC sent a letter QAL (the 24 March Letter). The letter stated in part:

We refer to your letter dated 23 March 2022.

You have sought our advice as to:

(a) the nature and extent of Mr Oleg Deripaska’s (Deripaska’s) interests in the EN+ Group, Rusal, ABC and each of their affiliated entities;

(b) whether we accept that QAL:

(i) will engage in a ‘sanctioned supply’ in contravention of the sanction imposed on 20 March 2022 if it transfers possession of alumina to ABC or Rusal; and

(ii) will be providing a ‘sanctioned service’ to the extent that it processes bauxite on behalf of ABC, delivers alumina to QAL’s wharf and loads that alumina on vessels for shipment by ABC or Rusal.

Deripaska Interests in EN+ Group, Rusal, ABC and each of their Affiliated Entities

…

Supply Sanctions

5. Following the Designation to which you refer in your letter, ABC has taken the following measures to ensure that there is no breach of Regulation 12 of the [Autonomous Sanctions Regulations 2011 (Cth)]:

(a) ABC will not provide any alumina it receives from QAL to Russia or to UC Rusal or any of its subsidiaries;

(b) all alumina delivered to ABC from QAL will be sold by ABC directly to third parties located outside Russia. Sales will be subject to a provision in the contract that:

(i) prohibits any alumina supplied, or resultant aluminium derived from the alumina supplied, from being sold or otherwise supplied to Russia; and

(ii) requires all sales contracts in respect of such alumina or aluminium to contain the same prohibition.

(c) any current agreements which were inconsistent with these arrangements have been or will be terminated or suspended.

6. Additionally, … ABC has never distributed dividends and does not propose to do so in the future. ABC is taxable in Australia. ABC is not taxable in Russia directly or indirectly and does not pay tax to the Russian Federation, as:

(a) ABC is exempt from Russian Controlled Foreign Company Rules (CFC Rules) as an active business (by virtue of Paragraph 3, Article 25-13.1 of the Russian Tax Code); and

(b) the ultimate parent company of ABC, UC Rusal (which is located in Russia and to which ABC is a wholly owned subsidiary), is exempt from CFC Rules until 2029 (Paragraph 58, Section 1 Article 251 of the Russian Tax Code).

7. ABC is prepared to give a binding undertaking, which reflects these matters, if this would give comfort to QAL.

8. In light of these matters, it is clear that any supply of alumina to ABC by QAL will not be a sanctioned supply because:

(a) the alumina will not directly or indirectly as a result of that supply be transferred to Russia or for use in Russia;

(b) as a direct or indirect result of that supply, the supply is not for the benefit of Russia.

9. As there is no sanctioned supply, it follows that:

(a) QAL will not be providing a sanctioned service in respect of ABC’s continued participation in the QAL operations; and

(b) the sanctions that are currently imposed do not trigger the Step-in Procedure pursuant to Article 14A of the Participations Agreement.

(Emphasis added.)

60 On 25 March 2022, Ms Baker prepared and sent a memorandum to the QAL Board which referred to legal advice received by the company that QAL would contravene the Russia Sanctions if Mr Deripaska holds an interest in the Rusal Group and QAL continues to process bauxite on behalf of ABC; and QAL is likely to contravene the Russia Sanctions if it processes bauxite on behalf of ABC, delivers alumina to QAL’s wharf and loads the alumina on vessels for shipment by ABC regardless of the intended destination of the alumina. QAL was advised that, in those circumstances, Art 14A of the Participants Agreement was likely to be enlivened.

61 On 29 March 2022, Ms Baker prepared and sent a further memorandum to the QAL Board, which provided an update on the advice the company had received concerning the 24 March Letter and the risk of contravening the Russia Sanctions. In short, the advice received by QAL did not change.

62 On 29 March 2022, ABC wrote to QAL stating that it disagreed with the advice that was summarised in the QAL Board memorandum of 29 March 2022.

63 On 1 April 2022, Ms Baker prepared and sent a further memorandum to QAL’s Board (dated 30 March 2022), which provided an update on the correspondence received from ABC dated 29 March 2022. The memorandum stated that QAL management intended to issue a letter on 4 April 2022 to ABC and Rio Tinto notifying them that the step-in procedure provided for in Art 14A of the Participants Agreement had been triggered.

64 On 2 April 2022, Ms Baker received a letter dated 1 April 2022 from Mr Gordymov requisitioning a meeting of the QAL Board on 7 April 2022 to consider and make a determination on whether to implement the step-in arrangement provided for in Art 14A and Appendix E of the Participants Agreement. Mr Gordymov also requested confirmation that QAL would continue to accept ABC’s bauxite deliveries and introduce its bauxite to the refinery process until such time as QAL’s Board had resolved to implement the step-in arrangement and that, pending the requisitioned Board meeting, QAL management would not take any steps to implement the step-in arrangement provided for in Art 14A of the Participants Agreement.

65 On 4 April 2022, QAL’s General Manager, Mr Pienaar, sent a letter (Step-in Notification) to ABC, RTA Holdco and RTA (which was incorrectly dated 4 April 2021) advising that:

(a) QAL management remained of the view that, to protect QAL from the risks associated with a breach of the Russia Sanctions, it was necessary to implement the step-in procedure provided for in Art 14A and Appendix E of the Participants Agreement; and

(b) the step-in procedure had been triggered and, for the purposes of Appendix E of the Participants Agreement, the “Bauxite Cessation Date”, the “Production Cessation Date” and the “Shipping Cessation Date” would be 11.59 pm (AEST) on Monday, 4 April 2022.

66 On 4 April 2022 at 11.59 pm (AEST), QAL gave effect to the step-in procedure provided for in Art 14A and Appendix E of the Participants Agreement, whereby it ceased to accept delivery of ABC’s bauxite, introduce ABC’s bauxite to the refinery process, and load ABC’s alumina shipments.

67 Due to the Step-in Notification, from the Bauxite Cessation Date of 11.59 pm (AEST) on 4 April 2022, QAL would not permit any kind of bauxite owned by ABC to be delivered to QAL’s wharf. The effect of this was that RTA could not unload the bauxite supplied to ABC pursuant to the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement and the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and shipped to the port of Gladstone under the Shipping Agreement. Therefore, due to the Step-in Notification and due to QAL not accepting delivery of ABC’s bauxite, RTA could not perform its obligations to supply and deliver bauxite under those agreements.

68 On 8 April 2022, RTA sent notices to the Russian parties of the occurrence of circumstances constituting force majeure events and the suspension of the supply of bauxite pursuant to para 1(c) of Appendix E of the Participants Agreement, Art 21 of the Monohydrate Bauxite Supply Agreement, Art 18.1 of the Low Mono Bauxite Supply Agreement and cl 11.1 of the Shipping Agreement.

ABC’s attempted shipment of alumina between 20 March and 4 April 2022

69 As at 20 March 2022, ABC had two scheduled shipments of QAL alumina to Russia for delivery to UC Rusal’s aluminium smelters. The first was a shipment of ABC alumina scheduled for 4 April 2022 to be loaded on the vessel Majesty Star, and the second was a shipment of Rio Tinto alumina pursuant to a swap agreement to be loaded on the vessel MV Ernest Vinberg. Mr Gordymov gave evidence that the swap agreement was suspended on 21 March 2022.

70 Mr Gordymov gave evidence that, following the announcement of the Export Sanction, he began looking for ways to divert ABC alumina to non-Russian ports for on-sale to third party customers. On 23 March 2022, Mr Gordymov arranged for the MV Ernest Vinberg to be nominated for the shipment of 57,000 tonnes of ABC alumina for discharge at the port of Qingdao in China. Mr Gordymov gave evidence that he intended that the alumina would be unloaded into the port storage and packed in so called “big bags” (flexible bulk containers) that would enable ABC to store alumina at the port of Qingdao until a suitable customer in China was found. Mr Gordymov gave evidence that Chinese ports are the only ports that offer such storage and that it is common practice among alumina sellers, including Alcoa and Rio Tinto, to deliver alumina to Chinese ports for storage. Mr Gordymov also gave evidence that, in parallel, he caused negotiations to begin on behalf of UC Rusal to sell ABC’s share of the alumina produced by QAL to customers in Europe, India and the Middle East.

71 Mr Gordymov gave evidence that negotiations regarding the cargo to be loaded onto the MV Ernest Vinberg fell through due to commercial and logistical reasons, while further negotiations regarding this cargo and negotiations regarding further cargos became redundant when QAL refused to load ABC alumina following the issue of the Step-in Notification.

The legislative framework

72 As the primary judge explained in the Reasons, the Australian Government has power to enact sanctions under two statutory regimes. The first regime is contained in the Charter of the United Nations Act 1945 (Cth), which relevantly empowers (in Pt 3) the Governor-General to make regulations for, and giving effect to, sanctions that the United Nations Security Council (UN Security Council) has resolved to impose and that Australia is required to carry out under the Charter of the United Nations, opened for signature 26 June 1945 (entered into force 24 October 1945). The second regime is contained in the Autonomous Sanctions Act and the Regulations. The sanctions imposed pursuant to this second regime are imposed by Australia autonomously, rather than derivatively following action taken by the UN Security Council. The second regime effectively broadens the power of the Australian Government to impose sanctions in circumstances where the UN Security Council is unwilling or unable to act, for example by reason of powers of veto held by permanent members of the UN Security Council. The Russia Sanctions were made under this second statutory regime.

The Autonomous Sanctions Act

73 The provisions of the Autonomous Sanctions Act set out below are from the compilation dated 8 December 2021, which was provided by the parties in the joint bundle of authorities.

74 The objects of the Autonomous Sanctions Act are stated in s 3 as follows:

3 Objects of this Act

(1) The main objects of this Act are to:

(a) provide for autonomous sanctions; and

(b) provide for enforcement of autonomous sanctions (whether applied under this Act or another law of the Commonwealth); and

(c) facilitate the collection, flow and use of information relevant to the administration of autonomous sanctions (whether applied under this Act or another law of the Commonwealth).

Country-specific sanctions

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), the autonomous sanctions may address matters that are of international concern in relation to one or more particular foreign countries.

Thematic sanctions

(3) Without limiting subsection (1), the autonomous sanctions may address one or more of the following:

(a) the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction;

(b) threats to international peace and security;

(c) malicious cyber activity;

(d) serious violations or serious abuses of human rights;

(e) activities undermining good governance or the rule of law, including serious corruption;

(f) serious violations of international humanitarian law.

75 The expression “autonomous sanction” is defined in s 4 as follows:

autonomous sanction means a sanction that:

(a) is intended to influence, directly or indirectly, one or more of the following in accordance with Australian Government policy:

(i) a foreign government entity;

(ii) a member of a foreign government entity;

(iii) another person or entity outside Australia; or

(b) involves the prohibition of conduct in or connected with Australia that facilitates, directly or indirectly, the engagement by a person or entity described in subparagraph (a)(i), (ii) or (iii) in action outside Australia that is contrary to Australia Government policy.

76 The Autonomous Sanctions Act contemplates that the scope and content of autonomous sanctions will be determined through the making of regulations. Part 2 of the Act concerns the making of such regulations. Section 10(1) relevantly provides as follows:

(1) The regulations may make provision relating to any or all of the following:

(a) proscription of persons or entities (for specified purposes or more generally);

(b) restriction or prevention of uses of, dealings with, and making available of, assets;

(c) restriction or prevention of the supply, sale or transfer of goods or services;

(d) restriction or prevention of the procurement of goods or services;

(e) provision for indemnities for acting in compliance or purported compliance with the regulations;

(f) provision for compensation for owners of assets that are affected by regulations relating to a restriction or prevention described in paragraph (b).

77 Section 14, within Part 2 of the Act, provides that if a person has engaged, is engaging, or proposes to engage, in conduct involving a contravention of the regulations, a superior court (which is defined to include this Court and the Supreme Court of a State or Territory) may by order, on the application of the Attorney-General, grant an injunction restraining the person from engaging in the conduct.

78 Part 3 of the Autonomous Sanctions Act creates offences relating to what are referred to as “sanction laws”. That expression is defined in s 4 to mean a provision that is specified in an instrument under s 6(1), which in turn empowers the Minister by legislative instrument to specify a provision of a law of the Commonwealth as a sanction law. Relevantly, regs 12 and 14 of the Regulations have been designated as sanction laws for the purpose of s 6(1) of the Act by the Autonomous Sanctions (Sanction Law) Declaration 2012 (Cth), Sch 1.

79 Section 16, within Part 3 of the Autonomous Sanctions Act, relevantly provides:

16 Offence—contravening a sanction law

…

Bodies corporate

(5) A body corporate commits an offence if:

(a) the body corporate engages in conduct; and

(b) the conduct contravenes a sanction law.

(6) A body corporate commits an offence if:

(a) the body corporate engages in conduct; and

(b) the conduct contravenes a condition of an authorisation (however described) under a sanction law.

Example: An example of an authorisation is a licence, permission, consent or approval.

(7) Subsection (5) or (6) does not apply if the body corporate proves that it took reasonable precautions, and exercised due diligence, to avoid contravening that subsection.

Note: The body corporate bears a legal burden in relation to the matter in subsection (7): see section 13.4 of the Criminal Code.

(8) An offence against subsection (5) or (6) is an offence of strict liability.

Note: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

(9) An offence against subsection (5) or (6) is punishable on conviction by a fine not exceeding:

(a) if the contravention involves a transaction or transactions the value of which the court can determine—whichever is the greater of the following:

(i) 3 times the value of the transaction or transactions;

(ii) 10,000 penalty units; or

(b) otherwise—10,000 penalty units.

Definition

(10) In this section:

engage in conduct means:

(a) do an act; or

(b) omit to perform an act.

The Regulations

80 Part 2 of the of the Regulations is headed “Autonomous sanctions” and contains regulations that define the scope of different sanction measures. Part 3 of the Regulations is headed “Sanctions laws” and contains prohibitions in respect of certain conduct; these prohibitions comprise the sanctions proper. Part 4 of the Regulations is headed “Authorisations” and contains regulations that define the circumstances in which conduct that would otherwise contravene autonomous sanctions may be authorised. The text of the regulations set out below is given as at 22 March 2022 (compilation date 5 March 2022), being the version used by the primary judge in the Reasons.

81 Regulation 3 sets out definitions and includes:

authorised supply means a sanctioned supply authorised by a permit granted under regulation 18.

…

designated person or entity includes a person or entity that has been designated under paragraph 6(a) …

82 Regulation 4 (which is relevant to the Export Sanction) provides in part:

4 Sanctioned supply

(1) For these Regulations, a person makes a sanctioned supply if:

(a) the person supplies, sells or transfers goods to another person; and

(b) the goods are export sanctioned goods in relation to a country or part of a country; and

(c) as a direct or indirect result of the supply, sale or transfer the goods are transferred:

(i) to that country or part of a country; or

(ii) for use in that country or part of a country; or

(iii) for the benefit of that country or part of a country.

(2) Goods mentioned in an item of the table are export sanctioned goods for the country or part of a country mentioned in the item.

[Table not reproduced. The Table refers to Russia, but the description of goods in respect of Russia does not include alumina.]

(3) In addition to subregulation (2), the Minister may, by legislative instrument, designate goods as export sanctioned goods for a country or part of a country mentioned in the designation.

Example: Equipment or technology related to the oil and gas industry.

…

83 Regulation 6 (which is relevant for the Designated Persons Sanction) provides in part:

6 Country-specific designation of persons or entities or declaration of persons

For paragraph 10(1)(a) of the Act, the Minister may, by legislative instrument, do either or both of the following:

(a) designate a person or entity mentioned in an item of the table as a designated person or entity for the country mentioned in the item;

…

84 Item 6A of the table under reg 6 concerns Russia and mentions the following persons:

(a) A person or entity that the Minister is satisfied is, or has been, engaging in an activity or performing a function that is of economic or strategic significance to Russia.

(b) A current or former Minister or senior official of the Russian Government.

(c) An immediate family member of a person mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b).

85 Regulation 12 (which is relevant to the Export Sanction) relevantly provides:

12 Prohibitions relating to a sanctioned supply

(1) A person contravenes this regulation if:

(a) the person makes a sanctioned supply; and

(b) the sanctioned supply is not an authorised supply.

…

(4) A body corporate contravenes this regulation if:

(a) the body corporate has effective control over the actions of another body corporate or entity, wherever incorporated or situated; and

(b) the other body corporate or entity makes a sanctioned supply; and

(c) the sanctioned supply is not an authorised supply.

Note: This regulation may be specified as a sanction law by the Minister under section 6 of the Act.

86 Regulation 14 (which is relevant to the Designated Persons Sanction) relevantly provides as follows:

14 Prohibition of dealing with designated persons or entities

(1) A person contravenes this regulation if:

(a) the person directly or indirectly makes an asset available to, or for the benefit of, a designated person or entity; and

(b) the making available of the asset is not authorised by a permit granted under regulation 18.

87 Regulation 18 relates to authorisation and provides in part:

18 Minister may grant permits

(1) The Minister may grant to a person a permit authorising:

(a) the making of a sanctioned supply; or

…

(e) the making available of an asset to a person or entity that would otherwise contravene regulation 14; or

…

(2) The Minister may grant a permit:

(a) on the Minister’s initiative; or

(b) on application by a person.

(3) The Minister must not grant a permit unless the Minister is satisfied:

(a) that it would be in the national interest to grant the permit; and

(b) about any circumstance or matter required by this Part to be considered for a particular kind of permit.

(4) A permit may be granted subject to conditions specified in the permit.

88 As the primary judge noted, a permit under reg 18 has not been granted in respect of the production of alumina by QAL for ABC or the delivery of alumina to ABC pursuant to the Gladstone alumina joint venture.

The relevant instrument and designation

89 On 17 March 2022, the Minister for Foreign Affairs made the Autonomous Sanctions (Designated Persons and Entities and Declared Persons—Russia and Ukraine) Amendment (No 7) Instrument 2022 (Cth) under reg 6(a). This added Messrs Deripaska and Vekselberg to the list of designated persons for Russia. The instrument commenced on 18 March 2022. In these reasons, consistently with the approach adopted by the primary judge, the expression “Designated Persons Sanction” is used to refer to the sanction law imposed by the combined effect of reg 14 of the Regulations and that instrument.

90 On 19 March 2022, the Autonomous Sanctions (Export Sanctioned Goods—Russia) Designation 2022 (Cth) was made under reg 4(3) and, relevantly, designated aluminium ores and other aluminium oxides as export sanctioned goods for Russia. The designation commenced on 20 March 2022. As the primary judge noted, it was not in dispute that, following this designation, the alumina produced by QAL at the Gladstone Plant was an export sanctioned good for Russia for the purpose of reg 4(3). In these reasons, consistently with the approach adopted by the primary judge, the expression “Export Sanction” is used to refer to the sanction law imposed by the combined effect of reg 12 of the Regulations and that designation.

The hearing at first instance

91 The following matters relating to the hearing at first instance (in particular, regarding witnesses called and whether they were cross-examined) are relevant for some of the issues to be considered on the appeal.

92 The Russian parties called four lay witnesses (Kirill Strunnikov, Aleksey Gordymov, Vladimir Runov and Dzianis Sidarkevich) and one expert witness (Natalia Kuznetsova, a tax expert), and tendered documents. Each of the witnesses was cross-examined. For present purposes, the most relevant witness is Mr Gordymov. He is the Head of Business Support (Head of Supply Chain) in UC Rusal, and is also a director of QAL. Mr Gordymov has never held a direct role or office in ABC, but part of his duties involves managing ABC’s procurement and shipment of alumina. The Russian parties did not call any director or officer of ABC to give evidence.

93 QAL called two lay witnesses and two expert witnesses (one of whom was Alan Clark), and tendered documents. None of those witnesses were required for cross-examination. Mr Clark is the founder and Managing Director of the CM Group, which is an independent research advisory group specialising in the analysis of global base and minor metals industries. Mr Clark holds a Bachelor of Applied Science (Metallurgy) from the University of South Australia and a Master of Business Administration (Management of Technology) from the University of Melbourne. He has over 25 years’ industry experience in base metals, specialising in supply-side analysis, cost assessment, primary production, technology development and process improvement. Mr Clark’s experience covers many of the world’s base, minor metals and minerals industries, including bauxite, alumina, aluminium, nickel, magnesium, scandium, tungsten, tin, mineral sands, molybdenum and manganese. He has particular expertise on the global aluminium value-chain, particularly bauxite and alumina. Through the CM Group, Mr Clark advises the world’s largest aluminium producers, investment banks, fund managers, traders, industry bodies and research houses as well as governments and major industry groups, such as the International Aluminium Institute, the Australian Aluminium Council and the Aluminium Association.

94 The Rio parties called two lay witnesses and tendered documents. Neither of those witnesses was required for cross-examination.

The reasons of the primary judge

95 The key conclusions of the primary judge have been set out at [13] above.

Section C

96 In section C of the Reasons, the primary judge set out the factual background. Substantial parts of that section have been reproduced above.

97 In section C.9 (at [129]ff, headed “Whether ABC alumina is likely to be exported to Russia”), his Honour set out, and made findings in respect of, evidence relating to two contested factual issues. The two issues were:

(a) the likelihood that, if QAL had delivered alumina to ABC after 20 March 2022, the alumina (that is, the alumina hypothetically delivered by QAL to ABC at Gladstone) would have been ultimately exported to Russia; and

(b) the likelihood that, if QAL had delivered alumina to ABC after 20 March 2022, the delivery of the alumina would have resulted in other alumina being supplied to Russia.

We will refer to the issue referred to in (a) as the Gladstone Alumina Issue and the issue referred to in (b) as the Other Alumina Issue. The primary judge gave further consideration to these issues in section D.3 of the Reasons (discussed below).

98 Section C.9 of the Reasons included the following at [130]:

Absent a binding and enforceable commitment given by ABC, there can be no doubt that, on and after March 2022, alumina delivered to ABC by QAL would have been, and would in the future be, exported to Russia for use in UC Rusal’s aluminium smelters. Mr Gordymov’s evidence was that ABC had, historically, shipped almost all of the alumina it obtained from QAL to Russia for use in UC Rusal’s aluminium smelters. As stated above, UC Rusal has a large demand for alumina for its Russian aluminium smelters (some 7.9 million tonnes per annum) and, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, had lost supply of alumina from the Mykolaiv refinery in Ukraine (which had produced approximately 1.75 million tonnes of alumina per annum) and from all Australian sources (760,000 tonnes per annum from QAL and 750,000 from other Australian producers).

(Emphasis added.)

The first sentence of the above paragraph was the subject of challenge on appeal.

99 In the next four paragraphs of the Reasons ([131]-[134]), the primary judge discussed the 24 March Letter and whether it had any bearing on the two contested factual issues identified at [97] above. The primary judge concluded at [134]:

For those reasons, I consider that the statements made in ABC’s letter of 24 March 2022 have no material bearing upon the assessment of the likelihood that alumina delivered to ABC by QAL would ultimately be exported to Russia or would by supplied in a manner that would result in other alumina being supplied to Russia (for example, pursuant to a swap agreement).

100 At [135], the primary judge referred to the Rusal Group Undertaking and observed that it could not affect the determination of past issues but could only operate prospectively (if accepted by the Court).

101 In the balance of section C.9 (at [136]-[147]), the primary judge set out, and made findings in respect of, the evidence of Mr Clark. As noted above, Mr Clark was called as an expert witness by QAL and was not cross-examined by the Russian parties. Nor did the Russian parties call an answering expert on the topics addressed by Mr Clark. Save for one minor matter (referred to at [147] of the Reasons), the primary judge accepted the evidence given by Mr Clark: see the Reasons at [141], [147]. Given the significance of Mr Clark’s evidence for the issues raised by the appeal, we set out [136]-[147] of the Reasons in full. We note that the following passage of the Reasons substantially reflects Mr Clark’s report dated 28 March 2023 (Mr Clark’s First Report) at pp 31-37. To assist the discussion later in these reasons, in some places, we have inserted in square brackets a reference to the relevant paragraph in Mr Clark’s First Report.

136 Mr Clark was asked to express his opinion concerning the likely effect on the supply of alumina to Russian aluminium smelters if QAL supplied alumina to ABC pursuant to the Gladstone alumina joint venture. In his report, Mr Clark assumed that, as at April 2022, UC Rusal would have had only weeks of alumina stocks on site. Mr Gordymov contradicted that assumption, stating that, at that time, UC Rusal had alumina stocks equivalent to two and a half months supply. Regardless of that difference, it is uncontroversial that UC Rusal’s demand for alumina did not reduce at that time and UC Rusal was forced to source alumina from other suppliers (including from China).

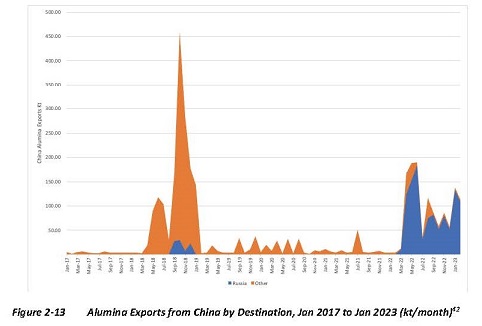

137 Mr Clark reported that China exported a total of 168,000 tonnes of alumina in April 2022 of which 124,000 tonnes was exported to Russia, accounting for 74% of the total [para 2.8(g)]. This resulted in China becoming a net exporter of alumina for the first time since 2018, despite no obvious price arbitrage opening between the Chinese and ROW markets. Mr Clark further reported that, in March and April 2022, China imported a total of 263,000 tonnes of alumina, 94% of which was sourced from Australia [para 2.8(i)]. Further, a report published by Wood Mackenzie in May 2022 titled “Can China keep Russian aluminium smelters afloat” stated that “more than 38% of China’s alumina exports (64kt) in April were identified as shipments from Customs’ warehouses” and concluded “it is likely that a sizeable portion of imported Australian alumina was transhipped to Russia”. Mr Clark considered that conclusion to be reasonable [para 2.8(i)]. Data presented by Mr Clark in his reports showed that alumina exports from China to Russia increased substantially in March 2022 from levels in the preceding years and remained elevated through to the time of Mr Clark’s report [para 2.8(i) and Fig 2-13]. As noted above, according to China Customs data, Russia has imported approximately 1.1 million tonnes of alumina from China over the 14-month period ending February 2023.

138 In question 9, Mr Clark was asked to express his opinion on the following question:

If ABC obtained from QAL the tonnage of alumina referred to in section 2 of this letter [approximately 730,000 to 760,000 tonnes] and sold it to third parties in China or otherwise outside Russia, as referred to in section 2 of this letter [on contractual terms prohibiting the buyers from on-selling that alumina to Russia], what effect, if any, would this have on the availability of alumina to Russian smelters?

139 Mr Clark reported that, heading into 2022, the ROW alumina market was generally balanced, meaning sufficient alumina was available to meet the requirements of ROW smelters and any surplus alumina produced in the ROW was sold into the Chinese market. The Chinese alumina market, however, was not balanced heading into 2022. China’s installed alumina refining capacity totalled 92.9 million tonnes per annum whereas its annualised production was estimated at 76.6 million tonnes per annum, approximately equivalent to its domestic aluminium smelting demand (being around 76 million tonnes per annum of alumina which is equivalent to approximately 38 million tonnes per annum of primary aluminium production). This is a difference in installed alumina refining capacity of 16.3 million tonnes per annum, representing a utilisation rate of only 82%. Thus, China’s domestic alumina industry had sufficient installed alumina refining capacity to produce a significantly larger volume of alumina which, if required and attractively priced, could have produced alumina to supply world markets in the first quarter of 2022. However, despite the structural overcapacity in China at the time, the country was a net importer of alumina, as it mostly is when the price arbitrage between domestic prices and ROW prices is sufficiently large to import alumina at a profit.

140 Mr Clark expressed the opinion that, given the balanced nature of the ROW market at the time, the fungibility of alumina and the structural overcapacity evident in China’s alumina industry at the time, the sale of any surplus alumina from QAL would most likely “free up” an equivalent volume of alumina elsewhere in the world [para 2.9(i)]. The most likely destination for the surplus alumina from QAL would be China, given the size of the market and the typical trading patterns at the time [para 2.9(j)]. However, with China’s market already in oversupply, any additional alumina would need to be “pushed” into China rather than “pulled”, meaning it would need to be offered into the Chinese market on more attractive terms than the current market price [para 2.9(k)]. Furthermore, with China’s market already saturated, pushing more alumina in would increase the likelihood that Chinese companies would seek to find export opportunities, including to Russia [para 2.9(l)]. Therefore, the most likely destination for QAL alumina tonnage supplied to ABC would be China, and supply to China would increase the likelihood that surplus alumina in China would find its way onto world markets, including Russia [para 2.9(m)].

141 I accept those opinions. It was not controverted by any other evidence.

142 In question 10, Mr Clark was asked to express his opinion on the following question:

Question 10: If ABC obtained from QAL the tonnage of alumina referred to in section 2 of this letter [approximately 730,000 to 760,000 tonnes] and sold it to third parties in China or otherwise outside Russia on contractual terms prohibiting the buyers from on-selling that alumina to Russia, as referred to in section 2 of this letter:

(a) would there remain a possibility that the alumina would end up in Russia, and, if so, how likely would that be and how would it occur?; and

(b) would there be any way of ensuring or monitoring compliance with the contractual prohibitions referred to?

143 Mr Clark reported that, when alumina is physically delivered under a contract to a customer, it cannot be traced with any degree of confidence [para 2.10(a)]. From a regulatory and compliance perspective, records are kept of alumina exports, including bills of lading, shipping records, insurance records, customs declarations and port records. Publication of this data by each country is usually in aggregate, meaning that, for example, port export data will provide monthly export volumes and countries of destination only [para 2.10(a)]. Once alumina arrives at its original country of destination, the chain can be easily lost and the original seller has no knowledge of, nor any means of checking, what happens to the alumina, whether for example it is processed by the buyer into aluminium or on-sold to a third party [para 2.10(b)].

144 Mr Clark expressed the opinion that, given the state of the global alumina supply/demand balance over the past two years, particularly the structural overcapacity in China, UC Rusal could source Chinese alumina from a wide variety of suppliers without great difficulty and have it shipped to Russia and UC Rusal would not necessarily know the origins of that alumina [para 2.10(d)].

145 Mr Clark also expressed the opinion that, if ABC obtained alumina from QAL, then that alumina could arrive in Russia through several different means, including [para 2.10(f)]:

(a) a series of subsequent on-selling transactions following the original purchase;

(b) through a swap arrangement;

(c) through blending the QAL alumina with alumina from another source; and

(d) following long-term storage in a bonded warehouse (ie a warehouse located in a jurisdiction that has not cleared any customs).