Federal Court of Australia

Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd v Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 139

ORDERS

GLOBAL RETAIL BRANDS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | GLOBAL RETAIL BRANDS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The cross-appeal be dismissed.

3. The declarations, injunction and other orders in paragraphs 1-12 (inclusive), 14 and 16 made by the primary judge on 13 March 2024 be set aside and in lieu thereof order that:

(a) The originating application be dismissed.

(b) The applicant pay the respondent’s costs of the proceeding.

4. The respondent to the appeal pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal and the cross-appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

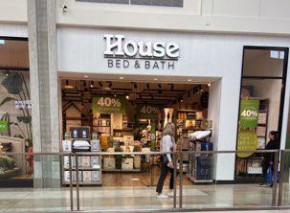

1 The appellant, Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd (“GRBA”), appeals against the primary judge’s judgment relating to its use of the following trade mark:

(“the House B&B mark”).

2 The respondent to the appeal, Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd (“BBNT”), is the registered owner of the following three registered trade marks, each of which it alleged was infringed by GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark:

(a) 654780 for the sign BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE, registered in class 24;

(b) 654781 for the sign BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE, registered in class 42; and

(c) 1878972 for the sign BED BATH N’ TABLE, registered in classes 24 and 35

(collectively, the “BBNT mark”).

The goods and services in respect of which the BBNT mark is registered are set out in Annexure A to these reasons.

3 The primary judge’s reasons in relation to liability (“J”) were published as Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd v Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1587 and her Honour’s reasons in relation to relief and costs were published as Bed Bath ‘N’ Table Pty Ltd v Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 226.

4 The primary judge was not persuaded that the House B&B mark was deceptively similar to the BBNT mark and therefore rejected BBNT’s claim for relief for trade mark infringement under the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (“TMA”). However, the primary judge found that GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, and that GRBA contravened s 18(1) and ss 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) as contained in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). Her Honour also found that GRBA engaged in the tort of passing off. Her Honour granted declaratory relief based on those findings and an injunction restraining GRBA from (inter alia) supplying, selling, offering to sell, advertising or promoting soft homewares, or the retailing of soft homewares, under the House B&B mark. GRBA appeals against the declaration and injunctive relief granted by the primary judge in respect of the contraventions of the ACL and for passing off. Independent of its appeal against those declarations and orders, GRBA also appeals against the costs orders made by the primary judge.

5 BBNT has brought a cross-appeal against the primary judge’s judgment dismissing its claim for relief under the TMA. BBNT also relies on a notice of contention in support of its position in the appeal. A notice of contention filed by GRBA in response to the cross-appeal was not pressed.

6 For the reasons that follow, we conclude that GRBA’s appeal should be allowed, the declaratory and injunctive relief granted by the primary judge should be set aside, and the claims for relief based on alleged contraventions of the ACL and passing off should be dismissed. We also conclude that the primary judge’s decision to dismiss the claims for relief under the TMA was correct and that BBNT’s cross-appeal should therefore be dismissed.

7 BBNT has traded under, and by reference to, the words “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” since 1976. The primary judge found that BBNT has approximately 30% of the Australian market share for speciality homewares and allied products based on the store numbers. Its competitors include Adairs, Pillow Talk, Linen House and Sheridan, which specialise in the sale of bed linen, bathroom products and household linen. Her Honour found that BBNT is a significant business that occupies a dominant position in the speciality soft homewares sector (J [26]-[28]). The term “soft homewares” encompasses textile goods, such as bedding and bed linen (for example, sheet sets, pillowcases and quilt covers); bathroom products (bath linen, such as towels, and bathroom accessories, such as soap dishes and shower caddies); household linen (for example, table cloths, table runners, napkins, teas towels and place mats); kitchenware (for example, cutlery, plates and bowls, serving ware and glasses, cups and mugs); and other homewares (for example, cushions, throws, vases and candles). By contrast, “hard homewares” refers to items such as pots, pans, plates and knives (J [24]-[25]).

8 Since the mid-1990s the BBNT brand has been consistently presented in accordance with the company’s brand guidelines in block capital letters on a plain background as follows:

9 BBNT stores typically display the brand prominently above the store entrance. The primary judge found the following presentation to be typical of BBNT’s physical stores:

10 The primary judge found that store signage used by BBNT typically appears in illuminated letters in white and green (J [31]). The primary judge also found that, until the launch of House B&B by GRBA, BBNT was the only retailer in Australia to use the words “bed” and “bath” in its name for over 40 years (J [75]).

11 The primary judge found that the BBNT brand had been used on packaging of BBNT’s goods, point of sale material, invoices and bags. The brand has been advertised and promoted extensively through the distribution of catalogues and email communications with customers. The brand has also been advertised and promoted in magazines including Better Homes & Gardens and Vogue Living and has also been featured in television programs including Channel 7’s “Postcards” and “House Rules” (J [33]-[34]). More recently, the focus of BBNT’s advertising has been on its website, social media and email communications (J [34]), including with members of a customer loyalty scheme established by BBNT which has almost 3 million members in Australia (J [42]). BBNT has operated an online store since 2013, and a Facebook page since 2017. It also operates Instagram and Pinterest accounts and undertakes digital advertising through Facebook and Google (J [43]-[47]).

12 According to BBNT’s statement of claim, each BBNT store front typically has:

(a) a prominent store front appearance including an open glass store front displaying homewares;

(b) prominent display signage bearing the BBNT mark appearing above the entryway to the store;

(c) the BBNT mark in frosted writing on the front glass of the store; and

(d) BBNT signage visible through the front windows and/store entryway in white writing on a green background

(“the BBNT Get-up”).

13 The primary judge referred to the evidence of Mr Jonathan Dempsey, the managing director of BBNT, concerning its use of the BBNT mark, the branding of its stores and the get-up of those stores as pleaded in BBNT’s statement of claim. Mr Dempsey referred in his evidence to some additional factors relevant to the get-up of the BBNT stores including the finishes of store floors, the point of the sale signage and the product signage (J [38]). His evidence was that the stores are carefully designed to create a home/boutique feel, with a bed or beds and linen and pillows displayed in the front windows to convey a sense of quality and trust and approximate the feel of a good home (J [39]).

14 The primary judge noted that BBNT accepted that a store front including an open glass display of homewares and made-up beds was not unique to the BBNT’s stores presentation. Rather, BBNT claimed that what is unique about the presentation of the BBNT stores is the use of the BBNT Get-up in combination with the BBNT name (J [40]). The primary judge noted that the experts and relevant lay witnesses all agreed that it is common for speciality retail linen stores to have similar store designs which comprise large shopfront glass windows with a made-up display bed visible through the windows near the entrance and the store name over the entrance. This “Hamptons style” look with white walls, wooden floorboards and no discount signage is intended to convey “a quality image” and a home feel that is luxurious and upmarket. This differentiates these stores from those with a strong discount focus, such as House, JB-HIFI or Chemist Warehouse, which tend to use yellow markdown signage (J [74]).

15 Mr Dempsey also gave evidence in relation to a number of concept stores operated by BBNT under and by reference to the “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE THE WORKS” and two other stores which operated for a few years under the name “HOMEWORKS BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE”. This evidence was relied on by BBNT as evidence of BBNT having engaged in the practice of brand extension and her Honour referred to it under that heading in her reasons (J [48]-[51]).

16 GRBA operates a range of stores under the “House” name and “sub-brands” including “House WAREHOUSE”, “House OUTLET”, “House POP UP”, “House Superstore” and “House CASA | MAISON | HOME”. The primary judge found that GRBA and its predecessors in title operated retail stores under the “House” brand from at least 1978. Her Honour found that by May 2021 the House brand was well-established in the hard homewares market, and that it had a substantial reputation as a retail brand throughout Australia. Her Honour also found that as at May 2021 there were approximately 100 physical House branded stores operating in Australia selling kitchenware and hard homewares which were generally located in major shopping centres or retail precincts (J [56]).

17 In around June 2020, GRBA acquired the business once known as “MyHouse” from administrators. MyHouse sold predominantly soft homewares (as opposed to the hard homewares sold through GRBA’s House stores). The MyHouse stores consisted of a network of 26 stores in New South Wales and one in Victoria which closed shortly before the acquisition. After the acquisition, one MyHouse store re-opened in Victoria and two new stores were opened in Queensland (J [133]).

18 In May 2021, GRBA began operating a new soft homewares business selling products for the bedroom and bathroom using the House B&B mark. The Doncaster store in Victoria, which was opened on 14 May 2021, is depicted as follows at J [163]:

Other examples of the use made of the House B&B mark by GRBA are reproduced in J [125] and in Annexure B to these reasons.

19 At J [515] her Honour reproduced the following images juxtaposing a GRBA HOUSE Bed & Bath store and a BBNT store located in the same shopping centre at Chadstone in Victoria:

20 The primary judge found that, partly as a result of shopping centres tending to group like stores together, specialty soft homeware retailers like Adairs, Sheridan and BBNT are often clustered together in “precincts” in shopping centres. As a result, House B&B is in close proximity to BBNT in many shopping centres, such as Doncaster where the first House B&B store was opened (J [78]).

Use of “bed” and “bath” as category or navigational descriptors

21 At J [92] the primary judge referred to evidence of substantial use by third party sellers of soft homewares in Australia of “bed” and “bath” as navigational or category descriptors both inside their physical stores and on their online stores. Her Honour referred to various examples of such use including by Big W, David Jones, Myer, Freedom, Kmart, Temple & Webster and Spotlight. However, her Honour also noted that in each of these examples the words “bed” and “bath” function as a navigational aid on websites or a general category descriptor inside shops, which are seen by consumers after they enter the physical store or the website. Her Honour noted that none of the examples in evidence used the words “bed” and “bath” on store exteriors or external store branding, and none involved the use of the words “bed” or “bath” as a trade mark. Her Honour also noted that GRBA accepted that no retailer in Australia other than BBNT had used “bed” or “bath” in its name until GRBA commenced to do so (J [94]).

22 With regard to both the BBNT mark and the House B&B mark, the primary judge did not consider that the words “bed” and “bath” as used in those marks perform a purely descriptive function. Her Honour observed that BBNT and GRBA sell bed and bath related products, but not beds or baths. She considered the words as used in the relevant marks to be “more allusive than directly descriptive” (J [431]).

23 The primary judge noted that the parties accepted that the relevant class of consumer shopping for soft homewares is the general public or the “ordinary reasonable consumer” (J [82]).

24 Evidence was given by various BBNT store employees relating to the alleged tendency of consumers to shorten the name BBNT and to instances of alleged customer confusion. Her Honour considered that this evidence should be treated with some caution. She characterised the evidence of the store employees as “essentially survey evidence” but “of a very low quality” because it was not randomised or representative and had been in effect “handpicked” by BBNT (J [113]). Having referred to various authorities concerned with the utility of such evidence, her Honour went on to conclude that the evidence should be given some weight as it showed that a reasonable number of consumers tended to shorten BBNT to “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” but that this evidence was not “conclusive of establishing that tendency” (J [114]). Her Honour also considered other evidence of the alleged tendency to shorten the BBNT name which she gave either very little, or no, weight (J [115] – [119]).

25 Her Honour concluded at J [120]:

Even if I was wholly satisfied that consumers have a tendency to shorten the BBNT name, I do not consider that, in any event, BBNT has established that it has any independent reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” alone.

Her Honour added at J [124]:

I therefore consider that, although consumers may have a tendency to occasionally shorten the BBNT name in informal settings such as in store or on the phone, BBNT has not established that it has a reputation, in any formal or institutional sense, in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” alone.

26 Later in her reasons, her Honour referred in some detail to the store employees’ evidence of customer confusion, including that of Ms Natalie Anna Erdossy (assistant store manager, Chadstone), Ms Honor Bettina van der Plight (store manager, Doncaster) and Mr Mitchell John Andrew Tabe (assistant store manager, Doncaster). In the course of evaluating this evidence, her Honour referred to what she described as its indirect nature and said at J [333] that “[t]he starting point is that indirect evidence of alleged confusion should be given little or no weight, particularly where no explanation has been given for the failure to call direct evidence”. Her Honour also quoted (at J [271]) State Government Insurance Corporation v Government Insurance Office of New South Wales (GIO) (1991) 28 FCR 511 at 529 per French J, where his Honour observed that “if the inference is open, independently of such testimonial evidence, that the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, then it may be that the evidence of consumers that they have been misled can strengthen that inference”. Her Honour concluded at J [340]:

I consider that the confusion evidence is admissible, but I give it limited weight. I accept that the evidence alone is not sufficient to establish deceptive similarity, misleading and deceptive conduct, or passing off. Although there are evident issues with the reliability and cogency of some of the evidence, there are examples of consumers, or other members of the public, confusing House B&B with BBNT and thinking there was some association between the two stores. Therefore, as I discuss below with respect to the ACL claim, the confusion evidence has a role in so far as it confirms other inferences available from the evidence that GRBA’s conduct caused confusion among the ordinary and reasonable consumer.

27 Later in her reasons, in the context of the ACL claims, the primary judge returned to what she referred to as “the alleged confusion evidence”. She reiterated at J [521] that she gave this evidence very little weight, but went on to say that the examples of confusion described by Ms Erdossy, Ms van der Plight and Mr Tabe strengthened the inference she had independently drawn that GRBA’s conduct was misleading or deceptive.

28 Each side called evidence from marketing experts. BBNT’s expert, Professor O’Sullivan, and GRBA’s expert, Associate Professor Nyilasy, hold academic positions. The experts agreed that consumers are generally aware of the practice of brand extension. The experts disagreed about what GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark would be likely to convey to consumers and, in particular, whether it would lead them to conclude, as Professor O’Sullivan contended, that the House B&B mark represented a collaboration between GRBA’s House and BBNT, that BBNT had been acquired by House (or vice versa), or that the business carried on under the House B&B mark was an extension of BBNT.

29 The primary judge did not consider it necessary to resolve the conflict between the expert witnesses. Her Honour correctly observed that expert evidence is of limited assistance in determining whether consumers are likely to be misled, and the question is ultimately a matter for the Court’s impression (J [258]) citing Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd v .au Domain Administration Ltd (2004) 139 FCR 215; [2004] FCAFC 247.

30 The primary judge made findings with regard to GRBA’s intention in adopting the House B&B mark, and what her Honour characterised as GRBA’s “wilful blindness as to the prospect of confusion arising from the adoption of a name that appropriated two words from one of its largest, if not the largest, competitor” (J [234]).

31 Her Honour was critical of evidence given by Mr Steven Lew, the founder and Executive Chairman of GRBA, and Ms Meghan McGann, GRBA’s Head of Brand and Media. Some of Ms McGann’s evidence was described by her Honour as “frankly unbelievable”.

32 The primary judge’s findings regarding the adoption of the House B&B mark appear in section 4 of her reasons on liability, and include the following:

GRBA initially planned to open over 50 MyHouse stores, and the set-up costs of the new soft homewares stores was substantial. Mr Bernard Bartholomew Caruana, GRBA’s Store Development Manager, was instructed by Mr Lew to design a new fit out for the MyHouse stores. Mr Lew was looking for a fit out that was “more modern and consistent with how GRBA fitted out its other retail stores, but appropriate for a store that sold ‘soft’ furnishings”. On 28 April 2021, Mr Caruana emailed Mr Lew and Ms McGann three layout options that he had prepared for the MyHouse store in Doncaster.

On 3 May 2021, before the first MyHouse store was scheduled to open on 14 May 2021 in Doncaster, Ms McGann queried during a telephone call with Mr Lew whether it was “too late to consider rebranding and calling this a HOUSE branded store”. Mr Lew’s initial reaction was that this was “a good idea”, as it would “allow GRBA to leverage off the goodwill associated with the HOUSE brand”. Mr Lew also considered that if the new store were branded House, GRBA could use the House customer database and potentially negotiate better leases with shopping centres and it would give customers more confidence in this new store as they were familiar with the House brand and, after only a year of trading, there was little awareness of the MyHouse brand outside New South Wales.

Later that day, Ms McGann sent an email to Mr Lew stating:

Thanks for calling

We WILL make this work and more than that — SOAR.

Just on our chat

Something to mull over

SHE KNOWS WHAT WE DO WELL

WE OFFER EXCELLENT PRODUCT WITH A GREAT VALUE PRICE TAG

WHY DOES A [ROBINS KITCHEN] AND A [HOUSE] IN THE SAME CENTRE ALWAYS FAVOUR HOUSE IN SALES? — SHE KNOWS AND TRUSTS THE BRAND.

We have all this BRAND LOYALTY TO LEVERAGE

Just something to think about? Not 100% there myself but there is something in it??

Before we roll out too many MYHOUSE — One could be [HOUSE] — we could try?

Aim to always open in the SAME centre so can push them either which way for deals — double our audience.

Will have Bed bath and table running scared.

HOUSE bed & bath.

HOUSE BATH AND BED

HOUSE BEDWORKS

(Emphasis added.)

(The primary judge referred to this email as “the running scared email” or the “3 May 2021 email”, the latter of which is adopted in these reasons.)

On 6 May 2021, Mr Lew decided to proceed with the House B&B mark as his preferred option out of several “logo concepts”. Later that day, following a request from Mr Lew’s executive assistant to “fast track the registration of the HB&B logo in Australia in class 35 only”, Mr Stephen Kenmar, GRBA’s corporate lawyer, lodged a Headstart application with IP Australia for the House B&B mark. The Headstart application, according to Mr Lew’s evidence as recounted by the primary judge, “gives a picture within around five days of whether there are any marks cited against the mark”.

In an email to Mr Lew also sent on 6 May 2021, Ms McGann stated “we need to do due diligence”. She set out a number of queries (in bold) to which Mr Lew responded shortly afterwards by filling in his answers. The question and answers included the following:

1. CHECK WITH LEGAL?

HOUSE Bed & Bath

BEING FAST TRACKED ….. NOT A BIG CONCERN FROM LAWYERS.

Check we can proceed — no objections

Send logo off to register

(Emphasis original.)

GRBA applied for registration of the House B&B mark on 12 May 2021. The application was accepted but subsequently opposed by BBNT. On 13 May 2021 the new signage was installed at the Doncaster store which opened the next day.

33 The 3 May 2021 and 6 May 2021 emails and, in particular, Ms McGann’s statement “[w]ill have Bed bath and table running scared” received considerable attention in the cross-examination of Ms McGann and Mr Lew. They were also given considerable attention in BBNT’s submissions in this Court.

34 When asked why she said in her email of 6 May that it was necessary to “check with legal”, Ms McGann said that she was not sure whether there were any legal implications with the name change on the lease that GRBA had signed for the Doncaster store and whether GRBA could change its lease agreement with the centre. She also said that she suggested they check with legal because “it is protocol in our company to check with Legal on almost everything we do in terms of brand, regardless of what the brand is”. The primary judge did not consider Ms McGann’s answers to be credible.

35 It is apparent that the primary judge was also unimpressed by Mr Lew as a witness. Her Honour was critical of Mr Lew’s evidence concerning his awareness of BBNT and his assertion that it never occurred to him to check with lawyers whether there might be a problem with the use of the House B&B mark apart from checking to see whether it could be registered. Some of Mr Lew’s evidence was described by her Honour as “particularly telling”. Her Honour said at J [186]-[187]:

[186] The resistance of Mr Lew to acknowledge his awareness of BBNT was particularly telling when he was asked whether he perceived any similarity between the store names BED BATH N’ TABLE and House BED & BATH, to which he answered “no” …

[187] In the circumstances, it would be extraordinary to think that Mr Lew, with his considerable experience as a retailer, did not have this awareness firmly in mind when selecting the words “BED & BATH” for the new store name. This was not disclosed in the evidence in chief and actively denied in cross-examination.

36 The primary judge said that GRBA’s conduct was in the realm of “wilful blindness”. Her Honour said at J [242]:

… The evidence showed that, at best, GRBA had an extremely cavalier attitude to intellectual property where its only form of due diligence in launching a new brand was to see whether it could get its own trade mark, rather than checking whether it generally had the freedom to operate. At worst and, in my view, more plausibly, Mr Lew was wilfully blind to the similarities between the name and logo of House B&B and GRBA’s key competitor BBNT as he perceived that there was a commercial benefit in using part of a well-known brand name in the new soft homewares store, a name that, in Mr Lew’s words, “rolls off the tongue”. Mr Lew and GRBA therefore proceeded with launching House B&B without going through any of their usual forms of due diligence, or even waiting for the results of the Headstart application, and without any regard for the potential for confusion that may arise as a result of the adoption of the House B&B name.

37 At J [469] the primary judge described what she referred to as Mr Lew’s “astonishing level of blindness to the possibility of confusion”. Ultimately, however, the primary judge stopped short of finding that GRBA adopted the House B&B mark with the intention of using it to deceive customers. Her Honour said at J [422]:

I consider that the evidence in this case falls short of demonstrating a commercially dishonest intention on the part of GRBA to appropriate part of BBNT’s trade or reputation. As explained above, I consider that GRBA’s conduct is more in the nature of a wilful blindness to any potential for confusion. This has relevance in the ACL context, but I do not consider it relevant to the consideration of whether the two marks are deceptively similar.

38 In the context of the ACL claim, her Honour observed at J [511] and [536]:

[511] It is also highly relevant that when it adopted the House B&B mark, GRBA was aware of the existence of BBNT and its reputation in the soft homewares sector, as both had been operating in the broader homewares sector for around 40 years. When combined with a surprising lack of legal advice and the fierce determination not to change the name of the store when the prospect of confusion was first brought to GRBA’s attention, GRBA’s attitude to the possibility of confusion of House B&B with BBNT can only be described as one of wilful blindness. Although GRBA’s wilful blindness may not amount to an intention to deceive consumers, it provides a similarly “reliable and expert opinion on the question of whether [GRBA’s conduct] is in fact likely to deceive”: see [Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 (“Australian Woollen Mills”)] at 657 (per Dixon and McTiernan JJ).

[536] … [A]lthough GRBA may have not set out with an intention to deceive or confuse consumers, it was wilfully blind as to the prospect of confusion arising from the adoption of a name that appropriated two words from one of its largest competitors. GRBA was simply unable to undermine the obvious inference that was open that GRBA borrowed the words “bed” and “bath” from BBNT’s name in order to attract customers from BBNT, and that such borrowing was “fitted for [that] purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse” consumers: Australian Woollen Mills at 657 (per Dixon and McTiernan JJ); [Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 234 FCR 549] at [117] (per Weinberg and Dowsett JJ).

39 It is apparent from these paragraphs that the primary judge stopped short of making a finding of dishonest intention to appropriate any part of BBNT’s trade or reputation or to deceive or cause confusion, finding that GRBA’s conduct was more in the nature of “wilful blindness to any potential for confusion”, a conclusion that her Honour considered relevant to the ACL claim, but (paradoxically) not to the claim of deceptive similarity under the TMA.

40 At J [393] the primary judge found that, in the context of the mark as a whole, the words “BED & BATH” are “merely used to designate a sub-brand of the well-known brand House”. Her Honour observed at J [395] that this was consistent with Ms McGann’s stated intention for the House B&B brand to distinguish those stores from the traditional House stores.

41 The primary judge also referred to the broader context in which GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark occurred. Her Honour identified twelve facts upon which she relied to support her finding that GRBA had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct at J [509]-[510]:

[509] The relevant broader context in which the conduct is to be judged includes the following (as at May 2021):

(a) BBNT had acquired an extensive reputation in the BBNT marks in Australia which had been accumulated over 40 years of use in the soft homewares market.

(b) The BBNT mark, despite containing ordinary English words, had become factually distinctive of BBNT as a result of over 40 years of use in Australia.

(c) BBNT had around 167 stores in Australia.

(d) The BBNT stores commonly had large front windows through which could be seen one or two made up beds in “Hamptons style” and frosted glass window decals with the BBNT mark. This style was similar to stores of other soft homewares retailers such as Adairs.

(e) Soft homewares retailers are often co-located in close proximity in shopping centres.

(f) GRBA had, over 40 years, acquired an extensive reputation in the brand House and its hard homewares stores in Australia.

(g) House stores had a particular “discount” look…and sold kitchenware products.

(h) GRBA had around 140 House stores in Australia.

(i) No retailers in Australia other than BBNT used the words “bed” and “bath” in their store name or external signage. BBNT therefore has had over 40 years of “unique” use.

(j) Soft homewares retailers use “bed” and “bath” as category descriptors inside their retail stores (as opposed to on external signage), particularly department stores.

(k) Soft homewares products range in price from a few dollars (face washer or coaster) to a few hundred dollars (quilt covers).

[510] The relevant immediate context includes the prominent use of “House” in the House B&B mark and the use of that mark on a soft homewares style shopfront. Also relevant is the appearance of House B&B stores. They are different to the typical House store with which consumers are familiar, with its cluttered appearance and discount signage. House B&B stores adopt the “Hamptons style” look of the other soft homeware retailers. The supposed differentiators pointed to by GRBA — the portrait orientation of the sheet sets and the presence of a linen press — are not readily observable to the customer outside the store.

42 The primary judge said at J [516] that the reasonable consumer would not see the words “bed” and “bath” in the House B&B store name primarily as category descriptors. Her Honour found that consumers were familiar with the use of those words as category descriptors inside stores, but not on the exterior of stores. Nor would consumers recognise a House B&B store as a House store of the kind with which they were familiar.

43 The primary judge’s ultimate conclusion in relation to the ACL claim appears between J [518] to [522]. Her Honour found at J [518]-[519]:

[518] I consider that when the conduct is viewed as a whole, in the immediate and broader contexts identified above, the reasonable consumer coming across a House B&B store for the first time would question whether there was some kind of association between the two well-known brands; that perhaps House had merged with BBNT or taken it over.

[519] Whilst the effect of the conduct may dissipate over time as consumers learn that there is no association between House B&B and BBNT, and that House B&B is actually a House sub-brand, there are likely to be consumers who have been enticed into the House B&B store in the belief that it has some association with BBNT. I consider that any confusion that may arise is more than “merely transitory or ephemeral” or “likely to be readily or quickly dispelled” (see [State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 2) (2021) 164 IPR 420] at [713] and [716] (per Beach J)) but rather may have, on occasion, led a consumer to purchase products from House B&B in the mistaken belief that it was a BBNT, or BBNT-related, store.

44 Her Honour then referred to “the alleged confusion evidence” which she said she gave “very little weight” but which nevertheless “strengthen[ed] the inference [she had] independently reached that GRBA’s conduct was misleading or deceptive” (J [521]).

45 The primary judge’s ultimate conclusion appears at J [522]. There, her Honour states that she was satisfied that, by adopting the name House B&B and launching the first House B&B store in May 2021 at Doncaster shopping centre, GRBA engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct contrary to s 18(1) of the ACL and made false and misleading representations that House B&B stores were somehow associated or affiliated with BBNT contrary to s 29(1)(g) and (h) of the ACL. It was common ground before the primary judge that, should that be the conclusion, BBNT’s claim for passing off would also succeed.

THIS COURT’S APPROACH TO THE PRIMARY JUDGE’S FINDINGS

46 Before considering the grounds of appeal, it is necessary to refer to the general principles relating to appellate review of a finding of misleading and deceptive conduct and passing off based on the use of a name or get-up which resembles that in which the applicant for relief has an established reputation.

47 There is no doubt that many of the primary judge’s findings were concerned with matters in respect of which a trial judge’s views carry significant weight. These include the primary judge’s finding that the House B&B mark was not deceptively similar to the BBNT mark (which is challenged by BBNT in its cross-appeal) and the finding that the use of the House B&B mark by GRBA was likely to mislead reasonable consumers into the erroneous belief that there was some association between the stores operated by GRBA under the House B&B mark and BBNT.

48 One area in which the primary judge’s findings will be treated with deference is where they comprise findings of fact likely to have been affected by impressions about the credibility of witnesses formed by the trial judge after seeing and hearing their evidence: see Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118; [2003] HCA 22 at [25]-[29], Lee v Lee (2019) 266 CLR 129; [2009] HCA 28 at [55]. These include “… findings of secondary facts which are based on a combination of impressions and other inferences from primary facts”.

49 GRBA does not challenge the adverse credit findings made by the primary judge in relation to GRBA’s witnesses, Ms McGann and Mr Lew. However, it does challenge the primary judge’s finding that GRBA engaged in misleading conduct, which is a finding that was influenced by those credit findings and, in particular, her Honour’s “wilful blindness” finding.

50 The approach the appellate court takes to a challenge to such findings was considered in some detail in Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd (2001) 117 FCR 424; [2001] FCA 1833 (“Branir”) which was later applied in Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd (2018) 261 FCR 301; [2018] FCAFC 93 (“Aldi”). In Branir Allsop J (with whom Drummond and Mansfield JJ agreed) said at [28]-[29]:

[28] … From Warren v Coombes [(1979) 142 CLR 531], the passages of Menzies J and Walsh J in Edwards v Noble [(1971) 125 CLR 296], from the other authority cited by the majority in Warren v Coombes and from more recent decisions of the High Court flow a number of relevant propositions. First, the appeal court must make up its own mind on the facts. Secondly, that task can only be done in the light of, and taking into account and weighing, the judgment appealed from. In this process, the advantages of the trial judge may reside in the credibility of witnesses, in which case departure is only justified in circumstances described in Abalos v Australian Postal Commission [(1990) 171 CLR 167]; Devries v Australian National Railways Commission [(1993) 177 CLR 472] and [State Rail Authority (NSW) v Earthline Constructions Pty Ltd (1999) 73 ALJR 306]. The advantages of the trial judge may be more subtle and imprecise, yet real, not giving rise to a protection of the nature accorded credibility findings, but, nevertheless, being highly relevant to the assessment of the weight to be accorded the views of the trial judge. Thirdly, while the appeal court has a duty to make up its own mind, it does not deal with the case as if trying it at first instance. Rather, in its examination of the material, it accords proper weight to the trial judge’s views. Fourthly, in that process of considering the facts for itself and giving weight to the views of, and advantages held by, the trial judge, if a choice arises between conclusions equally open and finely balanced and where there is, or can be, no preponderance of view, the conclusion of error is not necessarily arrived at merely because of a preference of view of the appeal court for some fact or facts contrary to the view reached by the trial judge.

[29] The degree of tolerance for any such divergence in any particular case will often be a product of the perceived advantage enjoyed by the trial judge. Sometimes, where matters of impression and judgment are concerned, giving ‘‘full weight’’ or ‘‘particular weight’’ to the views of the trial judge might be seen to shade into a degree of tolerance of divergence of views … In such cases the personal impression or conception of the trial judge may be one not fully able to be expressed or reasoned … However, as Hill J said in Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) v Chubb Australia Ltd (1995) 56 FCR 557 at 573 ‘‘giving full weight’’ to the view appealed from should not be taken too far. The appeal court must come to the view that the trial judge was wrong in order to interfere. Even if the question is one of impression or judgment, a sufficiently clear difference of opinion may necessitate that conclusion.

(Some citations omitted.)

51 In Aldi the Full Court disapproved of a “plainly and obviously wrong” test which had been applied in a number of cases decided after Branir. Justice Perram identified what his Honour referred to as the “indeterminate area” separating conclusions on questions of law from conclusions on questions of fact, or mixed fact and law, where the credibility of witnesses is involved. His Honour said at [49]:

… When an appellate court comes to review such conclusions it must be guided not by whether it disagrees with the finding (which would be decisive were a question of law involved) but by whether it detects error in the finding. On the one hand, error may appear syllogistically where it is apparent that the conclusion which has been reached has involved some false step; for example, where some relevant matter has been overlooked or some extraneous consideration taken into account which ought not to have been. But error, on the other hand, may also appear without any such explicitly erroneous reasoning. The result may be such as simply to bespeak error. Allsop J said in such cases an error may be manifest where the appellate court has a sufficiently clear difference of opinion: Branir at [29].

52 Leaving aside the correction of errors of law and errors in fact finding where the credibility of witnesses is involved, the deference to be given to a trial judge’s findings will vary depending on the relative advantages enjoyed by the trial judge when compared with the appellate court. How extensive the difference(s) of opinion between the trial judge and the Full Court must be before appellate intervention is justified will depend on the extent of the advantage(s) that the trial judge has over the appellate court in any given case: Aldi at [53]. However, if after making due allowance for the advantages enjoyed by the trial judge, the appellate court is of the view that the judgment under appeal is wrong, then it should give effect to its own view.

53 Leaving aside the grounds of appeal directed to costs, there were eight appeal grounds pressed by GRBA. Appeal ground 8 is solely concerned with the primary judge’s admission into evidence and evaluation of the alleged confusion evidence. Appeal grounds 1 to 7, which were the primary focus of the parties’ submissions, were as follows:

(1) The primary judge erred in holding that the use by GRBA of the House B&B mark contravened s 18 and ss 29(1)(g) and 29(1)(h) of the ACL and constituted passing off.

(2) Having correctly held that BBNT does not have any independent reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” alone, including because:

(a) there had been “substantial” and “common” third party use of “bed” and “bath” (including as a composite phrase) as navigational or category descriptors; and

(b) it is the composite phrase “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” which indicates a commercial connection with BBNT, and not simply “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”,

the primary judge erred in holding that “[i]t is the reputation of BBNT” that “is crucial in leading to a conclusion that GRBA engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in circumstances where the House B&B mark was not found to be deceptively similar to the BBNT mark”.

(3) Having correctly held that there are “substantial and crucial differences” and “significant differences” between the House B&B mark and BBNT mark, including that:

(a) it is “the composite arrangement of three descriptive words, punctuated by an “N”, which renders the BBNT [mark] distinctive” and that arrangement is “entirely absent” from the House B&B mark;

(b) the “N’ TABLE” conjunction in the BBNT mark is “visually and phonetically unusual”, “unique to BBNT” and a “key feature of the BBNT [mark]”; and

(c) GRBA enjoyed a substantial reputation in the brand “House” which is the “significant visual and aural part” at the start of the House B&B mark and the “dominant visual cue” of that mark,

the primary judge should have held that the use by GRBA of the House B&B mark did not contravene the ACL or involve passing off.

(4) The primary judge erred:

(a) In finding that the words “BED” and “BATH” were “more allusive than purely descriptive”;

(b) granting BBNT a de facto monopoly in the descriptive words “BED” and “BATH”, contrary to Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 229-230,

despite holding that

(i) there had been “substantial use” of the words “bed” and “bath” as navigational or category descriptors, including to navigate customers to bedroom or bathroom products;

(ii) the words “bed” and “bath” are commonly used inside soft homewares shops or larger department style stores which sell soft homewares, and on websites, as category or navigational descriptors; and

(iii) the words “bed” and “bath” (and “table”) are each “three well understood English words” which are each “descriptive”.

(5) Having correctly held that:

(a) it was “common for speciality retail linen stores to have similar store designs”; and

(b) the appearance of the BBNT stores was “not unique to BBNT”, “much like other soft homewares stores” and “typical for a soft homewares store”,

the primary judge erred in giving improper weight to:

(i) the “similarities in store get up” of the House Bed & Bath stores and the BBNT stores; and

(ii) the difference in appearance of the House Bed & Bath stores and the traditional House stores.

(6) The primary judge having correctly held that:

(a) GRBA did not have “a commercially dishonest intention” to “appropriate part of BBNT’s trade or reputation”; and

(b) her findings that GRBA’s conduct was in the nature of “wilful blindness” was not a matter which was relevant to the assessment of the alleged deceptive similarity between the BBNT mark and House B&B mark,

erroneously relied upon Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 (“Australian Woollen Mills”) at 657 to hold that GRBA’s wilful blindness provided a “highly relevant” expert opinion on the question of whether GRBA’s conduct was likely to deceive.

(7) The primary judge erred in holding, contrary to established authority, that BBNT had contravened the ACL because its conduct would cause consumers “to wonder” or “would question” whether there was an association between House B&B and BBNT.

54 An issue arose during the hearing about the scope of the notice of appeal and whether it was open to GRBA to challenge the primary judge’s finding that GRBA engaged in misleading conduct by its use of the House B&B mark independently of the alleged errors attributed to the primary judge in grounds 2 to 8 of the notice of appeal. BBNT submitted that it was not open to GRBA to contend that the ultimate result arrived at by the primary judge was wrong in the absence of GRBA establishing that her Honour’s reasoning was also erroneous in the manner identified in one or more of grounds 2 to 8. The effect of BBNT’s submission, if accepted, would be to preclude GRBA from submitting that the ultimate result itself bespeaks error: cf. Aldi at [49].

55 BBNT submitted that GRBA should not be permitted to challenge the correctness of the primary judge’s finding of misleading conduct independently of grounds 2 to 8. Senior Counsel for BBNT, Mr Golvan KC, accepted that there was nothing put by GRBA in support of its appeal that took him by surprise. However, he referred us to correspondence exchanged between the parties’ solicitors some months prior to the hearing of the appeal in which BBNT argued that GRBA’s appeal against the primary judge’s findings should be confined to those findings expressly identified in the notice of appeal. Nowhere in that correspondence did GRBA agree that its appeal should be limited to grounds 2 to 8 or that it was not open to GRBA under ground 1 to rely on a sufficiently clear difference of opinion in accordance with what was said in Aldi at [49] and Branir at [29].

56 A challenge to the primary judge’s finding that GRBA engaged in misleading conduct based on a clear difference of opinion as to the correctness of that finding is in our opinion open to GRBA under ground 1. We do not accept that BBNT is prejudiced by this approach. The particular findings challenged by GRBA during the hearing of the appeal are in our view adequately identified in the notice of appeal. Moreover, the arguments raised by GRBA in the appeal in support of ground 1 do not raise any matter which took GRBA by surprise or which was not fully addressed in the parties’ submissions.

57 While appeal ground 1 challenges the finding of misleading conduct generally, other grounds identify specific findings which GRBA says should have led the primary judge to reject the ACL and passing off claims. They include: substantial descriptive use of “bed and bath” as a composite phrase by other traders (grounds 2a and 4b); the extent of BBNT’s reputation in the BBNT mark (ground 2b); the visual and phonetic difference between the BBNT mark and the House B&B mark (grounds 3a and b); GRBA’s substantial reputation in the brand “House” (ground 3c); and the absence of any commercially dishonest intention on the part of GRBA to appropriate BBNT’s trade or reputation (ground 6a). GRBA also relies on the primary judge’s findings, in the context of trade mark infringement, that the House B&B mark was not deceptively similar to the BBNT mark and the finding that BBNT did not have any independent reputation in the words “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. These are all matters to which GRBA draws attention in support of its submission that the evidence before the primary judge did not justify her finding that GRBA had by its use of the House B&B mark engaged in conduct likely to mislead or deceive.

58 In its submissions BBNT relied on the scale of its reputation which was said to give it a unique place in the market for soft homewares. BBNT referred to the primary judge’s finding that no other retailer had used the words “bed” and “bath” in their store name or external signage and that BBNT had over 40 years of “unique” use. In oral submissions, Mr Golvan KC suggested that his client’s failure to establish that GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark constituted trade mark infringement, but success in persuading the primary judge that such use was likely to mislead or deceive, could be explained by her Honour’s findings with respect to BBNT’s reputation which was a matter irrelevant to trade mark infringement. His submission is borne out by the primary judge’s own observations in J [536] where her Honour explained that the reputation of BBNT was crucial to her finding that GRBA had engaged in misleading conduct but not trade mark infringement.

59 With regard to the substantial reputation which GRBA enjoyed in the “House” brand, BBNT submitted that GRBA had no reputation in relation to soft homewares and that the existing House stores had a completely different and cluttered appearance. BBNT submitted that:

The presence of the House mark did not tell against deception rather, as the Primary Judge found, a reasonable consumer coming across a House B&B store for the first time would question whether there was some kind of association between the two well-known brands; that perhaps House had merged with BBNT or taken it over and may have “led a consumer to purchase products from House B&B in the mistaken belief that it was a BBNT, or BBNT-related, store”. That finding is predicated on a legitimate understanding of the presence of the House mark as trading in a different market sector. It also accords with the findings in relation to cross-promotion and sub-branding.

(Footnotes omitted.)

60 BBNT placed emphasis on what it submitted was the use made by consumers of “BED & BATH” as a shortened form of BBNT’s brand name. It submitted that the shortening of well-known brand names is part of ordinary parlance and is especially apt, and much used, in the context of Australian English. BBNT relied on the primary judge’s finding at J [114] that a reasonable number of consumers have a tendency to shorten BBNT to “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”.

61 BBNT also placed emphasis on the primary judge’s finding of “wilful blindness”, which BBNT submitted suggested a conscious decision not to inquire about what it submitted was “the plainly inappropriate nature of the brand selection by Ms McGann”. It also pointed to the primary judge’s discussion of Ms McGann’s evidence in J [468] where her Honour found (in the context of the s 122(b)(i) defence) that Ms McGann “had an intention to divert trade away from BBNT”. BBNT emphasised (correctly) that GRBA did not challenge any of the primary judge’s findings relating to intention including, in particular, the finding at J [242] that Mr Lew was wilfully blind to the similarities between the House B&B mark and the BBNT mark as he perceived there was a commercial benefit in using part of a well-known brand name for GRBA’s new soft homewares stores.

62 As to store appearances, BBNT submitted that the primary judge considered store front appearances correctly in circumstances where those findings were used to dismiss the supposed “differentiators” in store fronts identified by GRBA. It argued that the similar “Hamptons style” store front, whilst not unique to the category, was a matter to be taken into account in distinguishing GRBA’s existing hard homewares House stores, which had a very different appearance.

63 In support of the primary judge’s ultimate conclusion, BBNT also relied on her Honour’s evaluation of the alleged confusion evidence, which she found at J [520] showed that some consumers were “caused to wonder” and did question whether there was an association between House B&B and BBNT.

64 For reasons which we will develop in the context of the cross-appeal, we consider that the primary judge’s finding that the House B&B mark was not deceptively similar to the BBNT mark was plainly correct.

65 Having found that the House B&B mark was not deceptively similar to the BBNT mark, the primary judge went on to find not merely that the GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark was likely to cause confusion but that it was also likely to mislead or deceive. In our opinion the evidence did not justify the primary judge’s finding that GRBA had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct. Before explaining why, we will briefly refer to the legal principles relevant to this topic.

66 First, it is necessary to identify the relevant conduct and the person or class of persons to whom the relevant conduct is directed: Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45; [2000] HCA 12 (“Campomar”) at [103]. In the present case the relevant conduct consists of operating one or more soft homewares retail stores under, and by reference to, the House B&B mark. The relevant class comprises ordinary or reasonable members of the class of prospective purchasers of soft homewares.

67 Secondly, the question whether the relevant conduct gave rise to a contravention of the ACL is to be assessed at the date the relevant conduct first occurred: Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (“Taco Bell”) at 196 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ. In this case that date is 14 May 2021, being the date GRBA’s Doncaster store opened using the House B&B signage.

68 Thirdly, the respondent’s conduct must be considered against the background of the immediate and broader context in which it occurred, including relevant surrounding facts and circumstances: Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (2023) 277 CLR 186; [2023] HCA 8 (“Self Care”) at [82]. In the present case these will include the strength of BBNT’s reputation in the BBNT mark.

69 Fourthly, whether or not conduct is likely to mislead or deceive is an objective question which the Court must determine for itself: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ. Conduct will be likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility that the relevant person or class of persons will be misled or deceived: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87.

70 Fifthly, while in some cases conduct may be misleading or deceptive without conveying a misleading or deceptive representation, in cases involving what is said to amount to conduct in the nature of passing off, it is necessary for the applicant to show that the respondent’s use of the impugned name or get-up is likely to convey to ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class a false or misleading representation that the respondent’s products or services are associated in some way with the applicant or its product or services: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ, cf. Henjo Investments Pty Ltd v Collins Marrickville Pty Ltd (No 1) (1988) 39 FCR 546 at 555 per Lockhart J (with whom Burchett and Foster JJ agreed). This is how BBNT’s case based on ss 18 and 29 of the ACL was pleaded.

71 Sixthly, conduct may be misleading or deceptive even though the respondent did not intend to mislead or deceive, and even though the respondent acted honestly and reasonably: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435; [2013] HCA 1 (“Google”) at [9]. However, proof that the respondent intended to mislead may provide some evidence that it was likely to have done so. As the Full Court said in Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 570; [2016] FCAFC 104 (“Verrocchi”) at [103]:

… proof of a subjective intention to mislead (in the sense that the respondents’ get-up is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival) may be some evidence that in a borderline case the respondents’ conduct is likely to mislead or deceive (see Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Company Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 657 per Dixon and McTiernan JJ and Sydneywide Distributors Pty Ltd v Red Bull Australia Pty Ltd (2002) 234 FCR 549 at [62] per Weinberg and Dowsett JJ).

The Full Court also referred at [104] to the distinction between an intention to copy and an intention to deceive. The Australian Woollen Mills inference may only be drawn if an intention to deceive is established.

72 Seventhly, evidence that members of the relevant class have been actually misled or confused is not essential but it may be given considerable weight. However, not all such evidence is persuasive. As observed by Nicholas J (with whom Dowsett J agreed) in Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc [2012] FCAFC 159; 294 ALR 661 at [137]:

It is well established that evidence of actual confusion may be highly persuasive. But as with other evidence, in assessing what weight should be given to it, the court must evaluate the quality of the evidence by reference to its internal features, the other evidence and the court’s own knowledge of human affairs…

Various factors may affect the weight to be given to what is said to be evidence of actual deception or confusion. These include: the way in which the evidence has been collected and presented (which may make it impossible to know whether any relevant misconception is attributable to the respondent’s conduct) and whether the evidence is likely to be representative of the thinking of ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class.

73 Eighthly, conduct which causes confusion is not necessarily co-extensive with misleading or deceptive conduct: Google at [8], Campomar at [106]. Moreover, as Stephen J observed in Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 229:

There is a price to be paid for the advantages flowing from the possession of an eloquently descriptive trade name. Because it is descriptive it is equally applicable to any business of a like kind, its very descriptiveness ensures that it is not distinctive of any particular business and hence its application to other like businesses will not ordinarily mislead the public. In cases of passing off, where it is the wrongful appropriation of the reputation of another or that of his goods that is in question, a plaintiff which uses descriptive words in its trade name will find that quite small differences in a competitor’s trade name will render the latter immune from action (Office Cleaning Services Ltd. v. Westminster Window and General Cleaners Ltd. (36), per Lord Simonds). As his Lordship said (37), the possibility of blunders by members of the public will always be present when names consist of descriptive words—“So long as descriptive words are used by two traders as part of their respective trade names, it is possible that some members of the public will be confused whatever the differentiating words may be.” The risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words and might even deter others from pursuing the occupation which the words describe.

(Footnotes omitted.)

Justice Stephen considered the trade names in issue in that case to be “eloquently descriptive”. Chief Justice Barwick referred to them at 221 as merely descriptive of the businesses carried on by the parties.

74 Ninthly, the distinction between descriptive names and invented names is not black and white. As Hill J explained in Equity Access Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation (1989) 16 IPR 431 at 448:

The reality is that there is a continuum with at the extremes purely descriptive names at the one end, completely invented names at the other and in between, names that contain ordinary English words that are in some way or other at least partly descriptive. The further along the continuum towards the fancy name one goes, the easier it will be for a plaintiff to establish that the words used are descriptive of the plaintiff's business. The closer along the continuum one moves towards a merely descriptive name the more a plaintiff will need to show that the name has obtained a secondary meaning, equating it with the products of the plaintiff (if the name admits of this - a purely descriptive name probably will not) and the easier it will be to see a small difference in names as adequate to avoid confusion.

A descriptive name may become distinctive of a particular trader’s business. In BM Auto Sales Pty Ltd v Budget Rent A Car System Pty Ltd (1976) 12 ALR 363 the name “Budget Rent A Car” was held to be sufficiently distinctive of the respondent’s business to support a claim for passing off. However, in the case of descriptive words, the applicant for relief must establish that those words have become distinctively associated with the applicant’s product for the relevant misrepresentation to be conveyed. If the respondent has not used the same words as those used by the applicant, but has instead used something similar, then “small differences may suffice to negative the likelihood of deception”: Telmak Teleproducts (Aust) Pty Ltd v Coles Myer Ltd (1988) 84 ALR 437 at 444 per Gummow J citing Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Windsor & General Cleaners Ltd (1946) 63 RPC 39.

75 The primary judge considered that the different outcomes for the trade mark case and the misleading conduct case arose due to the reputation of BBNT, which she described as “crucial” in leading to the conclusion that BBNT had engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct (J [536]). But that does not explain why BBNT’s reputation in the BBNT mark led her Honour to find that GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark would be likely to mislead or deceive the ordinary and reasonable consumer, even though the marks were not deceptively similar.

76 The findings with respect to BBNT’s reputation in the BBNT mark are referred to above. They include the fact that no other retailer had used the words “bed” and “bath” in their store names or external signage for over 40 years. However, it does not follow that those words alone were distinctive of BBNT. Nor does it follow that their use by another trader in the name of a soft homewares store would be likely to lead ordinary and reasonable consumers into thinking that it was associated in some way with the stores that operated under the “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” name.

77 The primary judge found at J [120] that BBNT had not established that it had any independent reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” alone. That finding was not challenged. It is a significant finding because it confirms that it is the use of the composite phrase “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” or “BED BATH AND TABLE”, not “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”, that would indicate the existence of a commercial association between the business operating under that name and another business using a different name which also included the words “BED & BATH”.

78 In its submissions BBNT contended that the finding at J [120] was directed to “a secondary (alternative) case on reputation advanced by BBNT” in which BBNT alleged that it has a separate reputation in “BED BATH”. BBNT also drew attention to J [124], in which her Honour found that BBNT had failed to establish reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” in any formal or institutional sense but acknowledged that consumers “may have a tendency to occasionally shorten the BBNT name in informal settings”. Neither of those points diminishes the significance of her Honour’s clear finding at J [120]. That finding was supported by the Google Analytics data to which her Honour referred. That showed that, when customers searched for BBNT or specific BBNT stores online, they did so using the BBNT name as a whole rather than some truncated version of the BBNT name (J [99]-[110]). Her Honour gave that evidence more weight (at J [123]) than the evidence of BBNT store witnesses, which was relied on by BBNT to show that its stores were known to at least some customers as “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. We agree with the primary judge’s assessment that the evidence of the store witnesses was of “very low quality”.

79 In our opinion the primary judge erred when considering the ACL claim by not giving effect to her own finding that BBNT had no independent reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. That finding is in our view inconsistent with the primary judge’s conclusion that the use by GRBA of the House B&B mark as the name of a soft homewares store was likely to lead ordinary and reasonable consumers to believe that the store was associated in some way with stores operated under the BBNT name. Further, even if it is accepted that such use may cause ordinary and reasonable consumers to wonder if there is any such association (which we consider unlikely), that would not be sufficient to justify a finding that GRBA had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct likely to mislead or deceive.

80 We accept that BBNT’s mark is not purely descriptive. As the primary judge noted, BBNT does not sell beds, baths or tables. That said, the name is partly descriptive in that it conveys that the products on sale in the stores trading under the BBNT mark are related in some way to beds, baths and tables. At the relevant date, “bed” and “bath” were widely used as categories or navigational descriptions by other sellers of soft homewares, albeit not in their trading name, as a trade mark, or on any external signage. By the relevant date there were large numbers of well-known retail outlets using the phrase “Bed & Bath” (either capitalised or uncapitalised) to describe the nature of the goods offered for sale within particular departments. Mr Dempsey accepted in cross-examination that “bed” and “bath” were commonly used descriptively to navigate customers to bedroom or bathroom products, and that BBNT had itself used those words as navigational aids and category descriptors on its website.

81 For a consumer to be misled into thinking there was some association between BBNT stores operated under the BBNT mark and GRBA stores operated under the House B&B mark, that person would have to either confuse the two marks (i.e., by mistaking one for the other) or, despite recognising the differences between them (including the presence of “House” in the House B&B mark and its absence from the BBNT mark), draw the inference from the presence of either “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” in the two marks that there was some association between the businesses using them.

82 As to the first possibility, we regard the differences between the two marks as substantial and obvious to anyone but the most careless observer. The fact that the BBNT mark is very well-known has little, if any, bearing on that matter. In our opinion the ordinary and reasonable consumer would be very unlikely to confuse the two marks irrespective of whether they knew of BBNT.

83 BBNT’s expert, Professor O’Sullivan, was of the opinion that GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark would be likely to convey to consumers that a soft homewares store operated under that name was the product of some collaboration between BBNT and GRBA’s House brand, that BBNT had been acquired by the House brand (or vice versa), or that House B&B was an extension of BBNT. Professor O’Sullivan’s reasoning assumes, however, contrary to the unchallenged finding of the primary judge, that BBNT has an independent reputation in the words “BED” and “BATH”, or a combination of the two, when used in relation to the business of soft homewares retailing.

84 The primary judge said at J [516] that the reasonable consumer would not see the words “bed” and “bath” in the House B&B store name “primarily as category descriptors”. Her Honour observed that consumers are familiar with those words when used as category descriptors inside stores but not on the outside of stores, except at the entrance to BBNT stores where the BBNT name appears. It is true that “bed” and “bath” are not used purely as category descriptors in the House B&B mark. This is because they form part of a trade mark and function when placed next to the word “House” as a trade mark. But that does not mean that the ordinary consumer would not also understand “BED & BATH” to be describing the nature of the products on sale in the store. The fact that those words had not previously been used as part of a brand name or on the outside of a store except by BBNT does not make it likely that the ordinary and reasonable consumer would think that no other trader could do so without being associated in some way with BBNT. In any event, even if ordinary reasonable consumers associate the words “BED & BATH” with BBNT, we do not think they would be misled into thinking that the two businesses are associated given the significant differences between the two names. The ordinary and reasonable consumer would do no more than infer that both businesses were engaged in the supply of soft homewares for bedrooms and bathrooms.

85 In seeking to uphold the primary judge’s conclusion, Mr Golvan KC placed considerable weight on the findings made by the primary judge with respect to GRBA’s intention. We will say more about this shortly in the context of BBNT’s notice of contention, but it is important to recognise that the primary judge stopped short of finding that GRBA had a commercially dishonest intention or an intention to mislead or deceive.

86 We do not consider either Mr Lew’s or Ms McGann’s intentions provide any real assistance in determining whether GRBA engaged in conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive. Taken at its highest, the primary judge’s finding with respect to Mr Lew’s state of mind amounts to a finding that Mr Lew knew that some confusion would occur: The Queen v Crabbe (1985) 156 CLR 464 at 470-471. However, knowing that some confusion will occur is not necessarily the same as intending that it occur. As we have previously mentioned, the use of trade names that consist of or include descriptive words frequently gives rise to confusion. It does not follow that a person using a descriptive name intends (in the sense of wishes) confusion to occur.

87 Although the primary judge found that Mr Lew was wilfully blind to the prospect of confusion, she did not find that he intended to mislead or deceive or, for that matter, that he intended to cause confusion. As the Full Court observed in Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235 385 ALR 514 at [67]-[68] (Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ) in the context of trade mark infringement:

[67] Despite the absence of a need for any defendant to have formed an intention to deceive or cause confusion, it may nevertheless be a relevant factor to take into account in the evaluation of deceptive similarity that the defendant did have that intention, as Dixon and McTiernan JJ explained in Australian Woollen Mills at 657.

[68] However, the role of intention in the analysis should not be overstated. It is but one factor for the court to take into account in its evaluation. As the majority held in Australian Woollen Mills at 658, in the end it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether or not there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the impugned mark should be restrained. That proposition may be demonstrated by noting that regardless of the mala fides of an alleged infringer, unless the impugned trade mark sufficiently resembles the registered owner’s mark, there cannot be a finding of deceptive similarity. To consider otherwise would be for the tail to wag the dog.

We refer also to what the Full Court said in Verrocchi at [103] which we referred to at [71] above. Picking up what the Full Court said there, in our opinion this is not a borderline case.

88 In the present case the primary judge considered that Mr Lew’s wilful blindness to the risk of confusion constituted reliable and expert opinion on the objective question whether GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark was likely to mislead or deceive ordinary and reasonable consumers. Given the limitations of her Honour’s findings, we do not think Mr Lew’s subjective state of mind was capable of providing any reliable evidence on the objective question.

89 GRBA submitted that there are statements in the primary judge’s reasons that conflate conduct that merely causes a person to wonder whether there is any relevant association between two traders and conduct that conveys a false representation that such an association exists: see, in particular, J [518] and [520]. BBNT submitted that her Honour’s reliance on the possibility of confusion was merely a “step along the way” to her finding of misleading conduct, and that it is apparent from a reading of her Honour’s judgment as a whole that she applied the correct test when considering the ACL claim. While there is some force in that submission, we do not think her Honour’s findings with respect to wilful blindness to the risk of confusion (based on Mr Lew’s evidence) and actual confusion (based on evidence which her Honour said she gave “very little weight”) were sufficient to establish (considered alone or in conjunction with other evidence) that GRBA’s use of the House B&B mark was likely to mislead or deceive ordinary and reasonable consumers.

90 BBNT contended that the primary judge erred in failing to give sufficient weight to the tendency of consumers to truncate, shorten or abbreviate store or other names recognised in London Lubricants (1920) Limited’s Application (1925) 42 RPC 264 at 279 and the fact that at least some consumers have a tendency to shorten “BED BATH ‘N’ TABLE” to “BED BATH”. The evidence directed to that matter included the Google Analytics data and the evidence of BBNT’s store employees. In support of its contention BBNT relied on her Honour’s finding in relation to that evidence including at J [114], together with the evidence of Professor O’Sullivan as summarised by her Honour at J [248]-[256].

91 The primary judge said at J [123] that the Google Analytics data showed that when internet users searched for BBNT they overwhelmingly did so by searching for the BBNT name as a whole. Her Honour gave that evidence more weight than the evidence of the store employees. It was open to her Honour to give the Google Analytics evidence greater weight than the store employees’ evidence for the reasons she gave, and with which we agree.

92 The primary judge said at J [114] that the store employees’ evidence showed that a reasonable number of consumers have a tendency to shorten BBNT to “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. That conclusion must be read in the context of J [120]-[124] .

93 As GRBA submitted, “what mattered was not the meagre evidence of truncation in informal settings”, but whether ordinary and reasonable consumers would expect BBNT itself to use a shortened form of its name. Her Honour rightly accepted the evidence of Associate Professor Nyilasy (at J [121]) that the mere fact that consumers might contract the BBNT name in those kinds of situations does not mean that consumers will expect the shortened form to be “institutionally applied” and used as a badge of origin unless there has been institutional use of the contraction. Here, as her Honour observed at J [122], the evidence showed that there was no institutional use of any contraction of the BBNT name:

In this case, the evidence was clear that BBNT had not made any institutional use of “BED BATH”. To the contrary, BBNT strictly followed its brand guidelines at all times, which required use of the brand only as a composite whole. Mr Dempsey accepted that BBNT had not contracted its brand to “BED BATH” in any advertising or promotion prior to May 2021. He agreed that BBNT used the BBNT mark in full (not contracted) on social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and on its online store. Further, in its history of brand extensions and sub-brands, BBNT has always used the whole of the BBNT name in unaltered form, in combination with the dark green colour background. In so doing, BBNT has further reinforced to consumers that it is the composite phrase “BED BATH N’ TABLE” which indicates a commercial connection with BBNT, and not simply “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”.

94 After referring to the Google analytics data (at J [123]), her Honour concluded (at J [124]) that “although consumers may have a tendency to occasionally shorten the BBNT name in informal settings such as in store or on the phone”, BBNT had not established that it had a reputation in “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH” in any “formal or institutional sense”. At J [438] her Honour reiterated that she was not satisfied that BBNT is recognised by consumers simply as “BED BATH”. Casual use by some consumers of the words “BED BATH” to refer to BBNT in telephone and in-store conversations has little, if any, probative value when determining whether or not the ordinary and reasonable consumer would be led to believe that there was a commercial association of some kind between BBNT and GRBA based on the latter’s use of the House B&B mark.

95 In any event, there was no finding that ordinary and reasonable consumers shorten the House B&B name to “BED BATH” or “BED & BATH”. In the absence of any finding to that effect, we do not consider any tendency to shorten the BBNT name carries any weight when assessing whether the use by GRBA of the House B&B name is likely to mislead or deceive ordinary and reasonable consumers.

96 BBNT also contended that the primary judge gave insufficient weight to “the fact” that Mr Lew accepted “that the public knew BBNT by reference to the words ‘bed’ and ‘bath’”, a proposition apparently put to her by BBNT and which her Honour apparently adopted at J [178].

97 We do not accept that contention. GRBA submitted that Mr Lew’s evidence was equivocal. In fact, her Honour overstated, if not misstated, the putative concession, as the trial transcript reveals (at T495). There, when it was put to Mr Lew that “the public knows [BBNT] by reference to the words ‘bed’ and ‘bath’”, he replied:

They may very well know the words “bed” and “bath” from Bed Bath ‘N’ Table, but if they walked into any other store – or many other stores that sold soft furnishings for the bedroom and bathroom or most of the competitors …, then they would see the words “bed” and “bath” and, particularly, online, the words “bed” and “bath” or “bedroom” and “bathroom” are used extensively.

(Emphasis added.)