FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2024] FCAFC 128

ORDERS

AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LIMITED Appellant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 2 OCTOBER 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is dismissed.

2. The appellant is to pay the respondent’s costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 I have had the considerable advantage of reading the draft reasons of each of Lee and Button JJ.

2 The appellant’s, Australian and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (ANZ), Notice of Appeal filed on 14 December 2023 raises four grounds:

(1) I agree that ground 1 should be dismissed for the reasons given by Lee J;

(2) as to grounds 2 and 3 which allege that the primary judge erred in finding that certain information was material for the purposes of s 677 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth):

(a) I agree with Button J that the information referred to at [2(d)(i) and (ii)] of the Notice of Appeal does not disclose any error in the primary judge’s conclusion as to the materiality of the “pleaded information” (as defined in the reasons of Button J at [122] below);

(b) I agree with Lee J that the balance of the further information relied on by ANZ at [2(d)(iii) and (iv)] of the Notice of Appeal also does not have any bearing on the primary judge’s conclusion as to the materiality of the pleaded information;

(c) it follows that those grounds should be dismissed; and

(3) I agree that ground 4 should be dismissed for the reasons given by Button J.

3 Accordingly, the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding three (3) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |

Associate:

Dated: 2 October 2024

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION AND THE PROCEEDING BELOW

4 The procedural and factual background of this appeal are set out fully in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (No 2) [2023] FCA 1217 (primary judgment or J) (at [19]–[288]) and for present purposes, it suffices to note the following.

5 On Thursday, 6 August 2015, the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ) undertook a fully underwritten institutional share placement to raise $2.5 billion. The placement was underwritten by three investment banks (Underwriters) being: Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Ltd; Deutsche Bank AG; and JP Morgan Australia Ltd.

6 ANZ’s shares were placed in a trading halt at 8:38am. The placement was announced to the market at 8:44am. The Underwriters carried out a book-build process throughout the course of that day and kept ANZ informed of progress from time to time during the day.

7 At 8:35pm, the Underwriters emailed a draft allocation list to ANZ showing the book was “covered” to 103%, and proposed that approximately $754 million of the shares not be allocated to investors (and hence would need to be taken up by the Underwriters). ANZ approved the proposed allocation with the consequence that the amount to be taken up by the Underwriters was increased to approximately $790 million worth of the shares (which amounted to about 31% of the placement).

8 At 7:30am on the following day, 7 August 2015, ANZ announced that it had completed the placement and had raised new equity capital of $2.5 billion but did not disclose, in the announcement or at any time before the recommencement of trading in ANZ shares on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) at 10:00am, that the Underwriters were to take up a significant proportion of the placement shares, being a value between $754 million and $790 million.

9 The primary judge dealt with a contention of ASIC that ANZ breached its continuous disclosure obligations by not disclosing to the market (either on the night of 6 August or before the recommencement of trading in ANZ shares on 7 August), either: (a) that the Underwriters were to acquire between approximately $754 million and $790 million worth of the shares; or (b) that the Underwriters were to acquire a significant proportion of the shares.

10 As we will see, under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) and the ASX Listing Rules (Listing Rules), listed entities have an obligation to disclose immediately information concerning the listed entity that is not generally available and that a reasonable person would expect, if generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of the entity’s securities (subject to certain exceptions). A reasonable person is taken to expect information to have a material effect on the price or value of securities where the information would or would be likely to influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of those securities.

11 It follows ASIC’s allegation brought with it the necessity to identify information of which ANZ was aware that was not generally available; and that this information was material within the meaning of the norms regulating the disclosure of material information to the market.

12 The primary judge accepted ASIC’s case that the pleaded information was not generally available and was material, having:

(1) rejected an argument of ANZ that the information was generally available because, following a review of the evidence, his Honour held it could not be deduced, concluded or inferred on the basis of information that was readily observable or publicly disseminated that the Underwriters were to take up a significant proportion of the placement shares (at J [416]–[427]); and

(2) accepted the argument of ASIC that the information it identified was material because, if the information had been disclosed, persons who commonly invest in securities would have held an expectation that the Underwriters would promptly dispose of allocated or acquired placement shares, and accordingly, place downward pressure on ANZ’s share price (at J [436]–[447]); in doing so, his Honour did not accept an argument of ANZ that it was necessary to have regard to further or contextual information for the purposes of assessing materiality, because some of the so-called contextual material relied upon by ANZ did not fully nor accurately reflect the facts, and other material did not affect meaningfully the assessment of materiality (at J [455]–[463]).

13 The primary judge later made a declaration that ANZ contravened s 674(2) of the Corporations Act on 7 August 2015, prior to the recommencement of trading in ANZ shares, by failing to notify the ASX either that shares in ANZ: (a) with a value of between approximately $754 million and $790 million; or (b) representing a significant proportion of the shares the subject of a $2.5 billion share placement, were to be acquired by underwriters of the share placement. His Honour also ordered ANZ pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty of $900,000, in respect of the contravention of s 674(2): Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (No 3) [2023] FCA 1565.

B THE APPEAL

14 The notice of appeal, in effect, raises four questions:

(1) Did the primary judge err in finding the pleaded information fell within s 677 of the Corporations Act by failing to construe and apply correctly the words “persons who commonly invest in securities”? (Ground 1)

(2) Did the primary judge err in finding the pleaded information was material within the (deemed) meaning of s 677 of the Corporations Act by failing properly to consider additional context which would render it immaterial? (Ground 2)

(3) Closely related to Ground 2, did the primary judge err in failing to have proper regard to what ANZ knew and understood, when assessing the materiality of the pleaded information? (Ground 3)

(4) Did the primary judge err in finding that the pleaded information was “information concerning it [the entity]” within the meaning of Listing Rule 3.1? (Ground 4)

15 There was no independent ground of appeal relating to penalty.

C STRUCTURE OF THESE REASONS

16 I have had the benefit of reading, in draft, the reasons of Button J as to Grounds 2 and 3. Although I agree with aspects of her Honour’s analysis of those grounds, I respectfully come to a different conclusion as to one determinative aspect of those grounds.

17 I deal below with Ground 1 and my reasons for why I would reject the attempt, by Grounds 2 and 3, to impugn the primary judge’s finding on materiality having regard to further contextual material, of which ANZ says it was aware.

18 I also agree with the conclusion of Button J that there is no substance in Ground 4. I deal with this ground briefly below.

D APPPLICABLE LEGAL PRINCIPLES AS TO DISCLOSURE

19 I will commence, however, by providing an overview of the regulatory scheme relating to disclosure. It is worth commencing in this way because this case is a good example of the necessity to avoid overcomplication and glosses in considering and explaining the requirements of the continuous disclosure regime.

20 In Section H of my reasons in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GetSwift Limited (Liability Hearing) [2021] FCA 1384 (at [1065]–[1104]), I set out, in considerable detail, the relevant law relating to obligations of continuous disclosure. Some of what follows has been taken from part of that judgment.

D.1 Background and Rationale

21 The necessity for a company to take steps to prevent a false market from being created in relation to its shares has a long genesis. As long ago as the late nineteenth century, a company requesting admission to the official list of the Sydney Stock Exchange was required to agree to the condition that it must give prompt notification of all calls, dividends, alteration of capital or other material information. This established the principle and the contractual obligation that a listed company must release material information to the market on an ongoing basis and as such was a forerunner of the continuous disclosure requirement: see Coffey, J “Enforcement of Continuous Disclosure in the Australian Stock Market” (2007) 20 Australian Journal of Corporations Law 301; a more comprehensive historical survey of the continuous disclosure obligations is canvassed in Golding, G and Kalfus, N “The Continuous Evolution of Australia’s Continuous Disclosure Laws” (2004) 22 Company and Securities Law Journal 385.

22 The listing rules were refined over time and an earlier version of Listing Rule 3.1, discussed below, required a listed entity immediately to notify any information that would be likely to affect materially the price of its securities or is necessary to avoid the establishment of a “false market”.

23 In November 1991, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs released a report in which the Attorney-General recommended that a regime of “continuous disclosure” by listed companies should be “introduced, implemented and enforced through the ASX Listing Rules”: House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Corporate Practices and the Rights of Shareholders (Report, Commonwealth of Australia, 1991) (at 106–107).

24 The original statutory provision enforcing continuous disclosure by listed companies was introduced in 1994, being s 1001A of the Corporations Law. This provision mandated compliance with a revised Listing Rule 3.1 which had removed the “false market” test and imposed a rule in substantially the same form as is presently relevant.

25 The rationale of the continuous disclosure regime is apparent. It is usefully described in Part 8 of the Department of Treasury, CLERP Paper No. 9: Proposals for Reform – Corporate Disclosure (Report, Department of Treasury, 2002) (at [8.2]):

The primary rationale for continuous disclosure is to enhance confident and informed participation by investors in secondary securities markets … Continuous disclosure of materially price sensitive information should ensure that the price of securities reflects their underlying economic value. It should also reduce the volatility of securities prices, since investors will have access to more information about a disclosing entity’s performance and prospects and this information can be more rapidly factored into the price of the entity’s securities.

26 Put simply, as was noted in National Australia Bank Limited v Pathway Investments Pty Ltd [2012] VSCA 168; (2012) 265 FLR 247 (at 260 [61] per Bell AJA, with whom Bongiorno JA and Harper JA agreed), the purpose of the continuous disclosure provisions:

… ‘is to ensure an informed market in listed securities’ and that ‘all participants in [that] market ... have equal access to all the information which is relevant to, or more accurately, likely to, influence decisions to buy or sell those securities’.

D.2 The Relevant Provisions

27 At the times material to this case, s 674 of the Corporations Act was in the following terms:

674 Continuous disclosure—listed disclosing entity bound by a disclosure requirement in market listing rules

Obligation to disclose in accordance with listing rules

(1) Subsection (2) applies to a listed disclosing entity if provisions of the listing rules of a listing market in relation to that entity require the entity to notify the market operator of information about specified events or matters as they arise for the purpose of the operator making that information available to participants in the market.

(2) If:

(a) this subsection applies to a listed disclosing entity; and

(b) the entity has information that those provisions require the entity to notify to the market operator; and

(c) that information:

(i) is not generally available; and

(ii) is information that a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of ED securities of the entity;

the entity must notify the market operator of that information in accordance with those provisions.

28 Listing Rule 3.1 relevantly provided as follows:

3.1 Once an entity is or becomes aware of any information concerning it that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of the entity’s securities, the entity must immediately tell ASX that information.

29 It follows from the terms of Listing Rule 3.1, that to establish a contravention of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act, ASIC was required to demonstrate facts which make out what can be conveniently described as four elements or “requirements”:

(1) there existed “information”;

(2) the entity had that information and was aware of it;

(3) the information was not “generally available”; and

(4) a reasonable person would expect that information, if it were generally available, to have a “material effect” on the price or value of the entity’s shares.

D.3 Information

30 The first requirement is that there must be something constituting “information”.

31 Listing Rule 19.12 relevantly defines “information” as including “matters of supposition and other matters that are insufficiently definite to warrant disclosure to the market” and “matters relating to the intentions, or likely intentions, of a person”. The question of whether there is information can sometimes be a matter of some controversy, partly because the elucidation of its reach “will, invariably, be assisted by analysis against specific factual circumstances”: Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) [2016] FCAFC 60; (2016) 245 FCR 402 (Grant-Taylor (FC)) (at 418–419 [94] per Allsop CJ, Gilmour and Beach JJ).

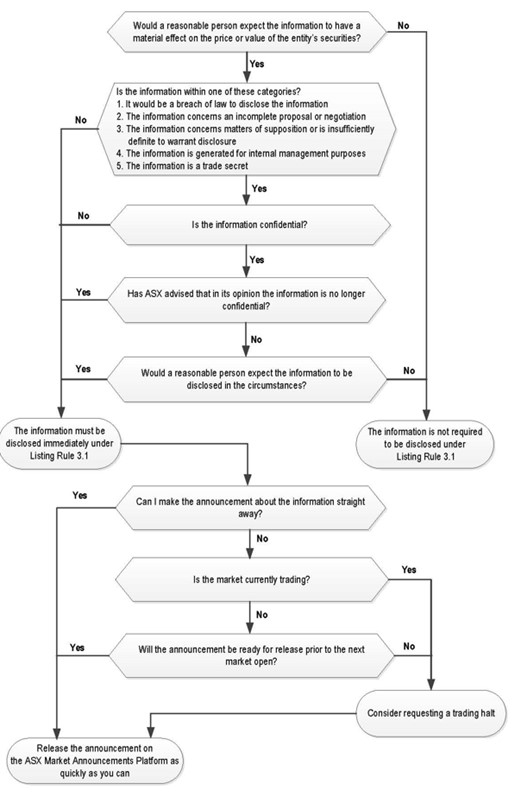

32 The ASX has published Guidance Note 8 to assist listed entities to understand and comply with their obligations under the Listing Rules and provides a flow chart of the continuous disclosure process (Guidance Note 8 (at 5 [2]), reproduced at [111] below). Guidance Note 8 does not have statutory force, but the ASX states in the note that it reflects the ASX’s position as to how the law is intended to operate. In a note subjoined to Listing Rule 3.1, the ASX sets out examples of the types of information that it considers would require disclosure if that information is material. As the ASX indicates in Guidance Note 8, this list of examples is not exhaustive and there are many other examples of information that potentially could be market sensitive.

33 Obviously enough, as will be discussed further below, given the nature of the obligation, when considering whether an entity has been compliant, it is necessary to identify the relevant information said to be the subject of the disclosure obligation with some precision (although having said this, the obligation is concerned with matters of substance over form).

D.4 Awareness of Information

34 The second requirement is that the entity has information: Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 418–419 [94]). It must also be established that the entity was “aware” of the information, in the sense that an officer of the entity has, or ought reasonably to have, come into possession of the information in the course of the performance of their duties as an officer: Masters v Lombe (Liquidator); In the Matter of Babcock & Brown Limited (in liq) [2019] FCA 1720 (at [273]–[274] per Foster J); citing Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 434 [185]).

35 Two defined terms used in Listing Rule 3.1 are important in understanding this requirement.

36 First, the definition of “aware” is defined by Listing Rule 19.12 in the following terms:

[A]n entity becomes aware of information if, and as soon as, an officer of the entity … has, or ought reasonably to have, come into possession of the information in the course of the performance of their duties as an officer of that entity.

37 Secondly, s 9 of the Corporations Act defines “officer” in the following terms (which applies to the Listing Rules pursuant to Listing Rule 19.3(a)):

officer of a corporation means:

(a) a director or secretary of the corporation; or

(b) a person:

(i) who makes, or participates in making, decisions that affect the whole, or a substantial part, of the business of the corporation; or

(ii) who has the capacity to affect significantly the corporation’s financial standing; or

(iii) in accordance with whose instructions or wishes the directors of the corporation are accustomed to act …

38 As can be seen, by reason of the definition of “aware”, s 674(2) operates by reference to the material information of which an officer of the entity has, or ought reasonably to have, come into possession. All such information amounts to information of which the entity is aware. It follows that the information of which an officer ought reasonably to have come into possession includes opinions the officer ought to have held by reason of facts known to the officer.

D.5 General Availability of Information

39 The third requirement is that the information must not be generally available. Sections 676(2) and (3) of the Corporations Act describe when information is taken to be generally available for the purposes of s 674:

676 When information is generally available

…

(2) Information is generally available if:

(a) it consists of readily observable matter; or

(b) without limiting the generality of paragraph (a), both of the following subparagraphs apply:

(i) it has been made known in a manner that would, or would be likely to, bring it to the attention of persons who commonly invest in securities of a kind whose price or value might be affected by the information; and

(ii) since it was so made known, a reasonable period for it to be disseminated among such persons has elapsed.

(3) Information is also generally available if it consists of deductions, conclusions or inferences made or drawn from either or both of the following:

(a) information referred to in paragraph (2)(a);

(b) information made known as mentioned in subparagraph (2)(b)(i).

40 The phrase “readily observable matter” is not defined in the Corporations Act. The requirement is a question of fact to be determined on an objective and hypothetical basis. Information, of course, may be readily observable even if no one has observed it. The test of whether material is readily observable is not whether the matter was observed but whether it “could have been observed readily, meaning easily or without difficulty”: see Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 424 [119]). As Jacobson J noted in Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Ltd (No 4) [2007] FCA 963; (2007) 160 FCR 35 (at 106 [546]) “observability does not depend on proof that persons actually perceived the information; the test is objective and hypothetical”.

D.6 Materiality

41 The fourth requirement, which is of decisive importance in this appeal, is provided for by s 674(2)(c)(ii) of the Corporations Act.

42 For the purposes of s 674, s 677 relevantly provides that a reasonable person will be taken to expect information to have a “material effect” on the price or value of securities if that information “would, or would be likely to, influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of” the securities.

43 As was explained in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vocation (in liq) [2019] FCA 807; (2019) 371 ALR 155 (at 281–282 [516] per Nicholas J), s 677 is in the nature of a deeming provision, which describes a sufficient, but not a necessary foundation for establishing the materiality requirement under s 674(2)(c)(ii).

44 In Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 420 [96]), the Full Court said:

What is meant by “material effect” in s 674(2)(c)(ii)? As stated earlier, s 677 illuminates this concept and also identifies the genus of the class of “persons who commonly invest in securities”. It refers to the concept of whether “the information would, or would be likely to, influence [such] persons … in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of ” the relevant shares. The concept of “materiality” in terms of its capacity to influence a person whether to acquire or dispose of shares must refer to information which is non-trivial at least. It is insufficient that the information “may” or “might” influence a decision: it is “would” or “would be likely” that is required to be shown: TSC Industries Inc v Northway Inc 426 US 438 (1976). Materiality may also then depend upon a balancing of both the indicated probability that the event will occur and the anticipated magnitude of the event on the company’s affairs (Basic Inc v Levinson 485 US 224 (1988) at 238 and 239; see also TSC v Northway). Finally, the accounting treatment of “materiality” may not be irrelevant if the information is of a financial nature that ought to be disclosed in the company’s accounts. But accounting materiality does have a different, albeit not completely unrelated, focus.

45 It follows that “the objective question of materiality posed by ss 674 and 675 by reference to the hypothetical reasonable person in turn has regard to what information would or would be likely to influence a hypothetical class of persons namely ‘persons who commonly invest in securities’”: Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 423 [116]).

46 In Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Limited (In Liquidation) [2015] FCA 149; (2015) 104 ACSR 195, Perram J noted (at 209 [64]):

What s 677 poses is an objective test to be applied at the time it is alleged the disclosure should have occurred. This involves a survey of all of the available material including, because they are part of the factual matrix, the views of the company and individual investors while accepting, of course, that those views cannot by themselves be determinative [citations follow]. … Despite this ex ante approach, it is nevertheless permissible to examine how the market subsequently behaved when the information was disclosed as a device for confirming the correctness of a conclusion already reached.

(Citations omitted, emphasis added)

47 The correctness of this observation was not questioned on appeal in Grant-Taylor (FC). The Full Court turned to the interplay between Listing Rule 3.1 and ss 674(2) and 677, putting beyond doubt that: (a) materiality is a question which is looked at ex-ante and depends upon a balancing of both the indicated probability that a relevant event will occur and the anticipated magnitude of the event on the company’s affairs; and (b) the class of “persons who commonly invest in securities” to whom the Court ought have regard in determining materiality (by assessing whether those persons would have been influenced in their investment decisions by the release of the alleged material information) includes not just sophisticated investors, but small, infrequent and unsophisticated investors: Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 419–420 [95]–[96], 426 [131]).

48 Hence although the considerations evaluated by a company and its reasons for withholding certain information from the market may be relevant, they are not determinative: James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010) 274 ALR 85 (at 195 [527] per Spigelman CJ, Beazley and Giles JJA). Of course, given the test is objective, the fact officers of an entity may themselves reasonably believe that information would not be expected to have a material effect does not answer the question of whether the material was required to be disclosed: Vocation (at 281 [515]; citing James Hardie (at 195 [527], 199 [546])).

49 Further, s 677 differs in its focus from the treatment of materiality in accounting, in that the accounting treatment of materiality has less relevance where the information is not financial information of a type that is required to be disclosed in a company’s accounts: Vocation (at 282 [518]); citing Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 420 [96]). I will return to this concept below.

50 To satisfy the “materiality” requirement imposed by s 674(2)(c)(ii), the information must be “non-trivial” and rise beyond information which “may” or “might” influence a decision by investors and it must be shown that the information “would” or “would be likely” to influence a decision: Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 420 [96]).

51 The relevant “influence” is that which bears upon common investors. This was explained in Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (No 5) [2009] FCA 1586; (2009) 264 ALR 201 (at 309 [521] per Gilmour J):

The relevant influence is that bearing upon common investors, relevantly, “deciding whether to acquire or dispose of” [the relevant securities]. Influence which is productive of mere consideration but no decision either way is not the relevant statutory influence. This is so because the primary question under s 674(2) is whether the information is such that a reasonable person would expect it to have a material effect on “the price or value” of [the relevant securities]. Information which would or would likely influence common investors merely to consider whether to buy or sell [the relevant securities] but not decide to buy or sell could never be expected to have a material effect on the price or value of those securities.

(Emphasis added)

52 Determining whether information (had it been generally available) would be expected by a reasonable person to have a material effect on the price or value of a company’s securities is a matter which can be addressed by expert evidence: James Hardie (at 139 [228]). Such evidence may aid the Court in determining the predictive exercise that the sections require. This is not to say that expert evidence will always be useful. After all, the assessment of materiality upon an ex-ante approach involves a matter of judgment, informed by commercial common sense: see Gilmour J in Fortescue (at 307 [511]).

53 Evidence of the actual effect of the information disclosed on the share price may be relevant in determining whether s 674(2) of the Corporations Act has been contravened. As was explained by Perram J in Grant-Taylor in the extract above (at [46]), such evidence may constitute what amounts to a cross or reality “check” as to the reasonableness of an ex-ante judgment about a different hypothetical disclosure: Fortescue (at 301 [477] per Gilmour J).

D.7 Specificity of Information and “Context”

54 As can be seen, fundamental to assessing compliance with any obligation to disclose is identification of the “news” said to constitute the relevant information. Given the importance of contextual information to the disposition of this appeal, it is important to understand the role of contextual facts and opinions and how they fit into a principled analysis of whether there has been a breach of the continuous disclosure obligations.

55 In this regard, it is important to remember that this is a regulatory proceeding and not a securities class action. It follows that we are presently concerned with the identification of contravening conduct – not issues of causation or loss that might flow from any proven contravention.

56 In Vocation (at 294–295 [566]), Nicholas J, in another regulatory proceeding, explained that information may need to be considered in its “broader context” to determine whether it satisfies the statutory test of materiality, including “whether there is additional information beyond what is alleged not to have been disclosed and what impact it would have on the assessment of the information that the plaintiff alleges should have been disclosed”, citing James Hardie and Jubilee Mines NL v Riley [2009] WASCA 62; (2009) 40 WAR 299. It is trite that the materiality of information must have regard to all the relevant circumstances, including any matters of context bearing upon materiality.

57 It has been said, more than once, that a contravention of s 674(2) of the Corporations Act must be pleaded precisely and the moving party must “identify the case it seeks to make … clearly and distinctly”: Cruickshank v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 128; (2022) 292 FCR 627 (at 659 [120] per Allsop CJ, Jackson and Anderson JJ); see also TPT Patrol Pty Ltd, as trustee for Amies Superannuation Fund v Myer Holdings Limited [2019] FCA 1747; (2019) 140 ACSR 38 (at 229–230 [1121] per Beach J); Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited [2018] FCA 659 (at [24] per Yates J). These observations must be understood as directed to the function of a pleading, which is to state with sufficient clarity the case that must be met, hence serving to ensure the basic requirement of procedural fairness that a party should have the opportunity of meeting the case against it and, incidentally, to define the issues for decision: Banque Commerciale SA, En Liquidation v Akhil Holdings Limited (1990) 169 CLR 279 (at 286 per Mason CJ and Gaudron J).

58 However, it is important not to elide different stages of the relevant inquiry. The applicant is required to plead and hence identify the information that it alleges: (a) existed; (b) the entity “had”, and of which, it was “aware”; (c) was not “generally available”; and (d) a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a “material effect” on the price or value of the entity’s shares. The pleaded information either had these cumulative characteristics or it did not. That is the end of the liability inquiry subject to any affirmative defences.

59 I am conscious that there are cases such as Jubilee Mines where observations have been made (at 322 [87]–[88] per Martin CJ, McLure JA and Le Miere AJA agreeing) that: (a) the “information” must also include all contextual matters of fact and opinion necessary in order to prevent the disclosing company making a misleading disclosure; and (b) to define the “information” narrowly by taking it outside of its broader factual and commercial/corporate context, then gauge whether that information has the deemed material effect by reference to the common investor who assesses the information in the context of publicly available information, is inconsistent with the purpose of the disclosure regime, which is a fully informed market: see also Grant-Taylor (at 211–212 [73]–[74]); Bert v Red 5 Limited [2016] QSC 302; (2016) 349 ALR 210 (at 249 [205] per Applegarth J); and Zonia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (No 5) [2024] FCA 477 (at [568] per Yates J).

60 But such observations should not be decontextualised. Of course, in assessing ex-ante, whether information is market sensitive and requires disclosure, the information needs to be looked at in context, rather than in isolation, against the backdrop of: (a) the circumstances affecting the entity at the time; (b) any external information that is publicly available at the time; and (c) any previous information the entity has provided to the market. This is a point made in Guidance Note 8 (at 12–13 [4.3]).

61 Additionally, considering whether other contextual facts or news existed that would have been required to be disclosed contemporaneously with any disclosure of the pleaded information (to ensure disclosure of the pleaded information would not be misleading) may have some use as an analytical tool to test the relevance of those contextual facts and opinions to the materiality of the pleaded information. But it is for the party alleging the contravention to define the information said to have required disclosure.

62 As the primary judge recognised, when it comes to any contextual material, such material is directly relevant to the assessment of materiality of the pleaded information. That is, it may be other facts are present (such as those identified by ANZ in this case) which necessitate the conclusion that the pleaded information, found to exist, was not material. The contextual material does not directly bear upon the anterior question as to whether the pleaded information existed.

63 When it comes to questions of causation and loss (not relevant in this regulatory proceeding but necessary for recovery of loss in a securities class action), attention is directed to the “but for” world. It is at this step, logically subsequent to the establishment of contravening conduct, that attention must be directed to the mode by which the pleaded information would, in the counterfactual world, have been disclosed – including the assessment of any confounding information or other contextual material that may have been disclosed to the market but for the contravening conduct.

64 At the risk of repetition, any notion it is necessary to consider whether the pleaded information was information that was “appropriate” to be disclosed in its pleaded form is incorrect to the extent that such consideration goes beyond an assessment as to whether the pleaded information was, or was not, material (cf Zonia Holdings (No 5) (at [568])).

65 A further point should be made about context or the possibility of further information.

66 Once an entity is aware of material information, it must announce the extent of that information immediately. An entity cannot adopt a “wait and see” approach in the hope of obtaining some greater qualitative or quantitative specificity. The obligation to disclose material information cannot be deferred while an entity awaits further detail or additional matters, which might be said to be in some way “contextual”, if this additional material would not change the substance of the material information known (that is, the reason why the information was objectively material in the first place). This is also a point also made in Guidance Note 8, which correctly notes that the “question is each case is whether the entity is going about this process [of disclosure] as quickly as it can in the circumstances and not deferring, postponing or putting it off to a later time” (at 14–15 [4.5]).

67 Commonly, a company may be required to undertake an investigation or take additional steps to identify the entirety of the news it may need, or wish, to announce. But there is a logical and often practical difference in ascertaining whether information is material and assessing the extent of materiality. Once an entity’s officers are aware of material information that is otherwise disclosable, the obligation is extant – even if a supplemental disclosure may be required when investigations or other steps are completed, and which may assist in ascertaining a more precise impact of the fact or opinion disclosed on the price or value of the company’s shares.

E GROUND 1

E.1 ANZ’s Argument

68 As noted above, the primary judge found that the pleaded information fell within s 677 of the Corporations Act. The ANZ contends this was in error because the “persons who commonly invest in securities” within the meaning of that provision are persons who are influenced in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of securities based on company fundamentals, and the pleaded information in this case was not relevant to the value of ANZ’s shares.

69 At trial, ASIC did not prove the pleaded information was relevant to the value of ANZ’s securities. Although ASIC had initially sought to prove that disclosure of the pleaded information would have had a price effect (apparently directed to the elements of s 1317G on the issue of relief) the evidence admitted at trial did not establish a quantifiable impact on ANZ shares (at J [370]–[372]).

70 ANZ asserts that by finding that persons who commonly invest in securities would decide whether to acquire or dispose of ANZ shares on the basis of information which was “irrelevant to value (and which had no established price effect)”, the primary judge failed to grapple with, and did not follow, the judgment in Vocation (at 291 [552]–[553]) and misconstrued the statutory test.

71 In Vocation, Nicholas J considered the meaning of the statutory concept by observing that the use of the word “invest” rather than purchase or acquire in s 677 suggests that the hypothetical reasonable person referred to in that section will be someone who makes an assessment as to whether to buy or sell securities on the basis of a company’s earnings or potential earnings and the potential return the investment offers after making an allowance for risk. His Honour dismissed the relevance of “knowledge of the investing behaviour of speculators and day traders who seek to profit on the back of rumour or momentum rather than company fundamentals” (at 291 [553]). ANZ further submits this reasoning was approved by Anderson J in McFarlane as Trustee for the S McFarlane Superannuation Fund v Insignia Financial Ltd [2023] FCA 1628 (at [147(13)]).

72 Consistently with this approach, Guidance Note 8 states that the ASX interprets the reference to persons who commonly “invest in” securities in s 677 as a reference to “persons who commonly buy and hold securities for a period of time, based on their view of the inherent value of the security” and as not including persons “who trade into and out of securities without reference to their inherent value” (Guidance Note 8 (at 9–10 [4.2])).

73 It is further supported by the distinction in language, in s 677 itself, between investing (on the one hand) and acquiring or disposing (on the other). The section, it is submitted, would have a quite different meaning if it referred to “persons who commonly buy or sell securities in deciding whether to buy or sell”. Persons who “invest in” securities describes persons who are buying, not selling. It connotes a purpose which is different from a goal of trying to exploit short term price fluctuations (which entails “buying and selling”).

74 The use of the word “whether”, rather than “when”, in the phrase “whether to acquire or dispose of the ED securities” is said to be a further indication that the statutory test is concerned with the making of investment decisions rather than the mere timing of decisions as to purchases and sales with a view to short-term price fluctuations.

75 This position is contended to be consistent with the objectives of the law. The continuous disclosure provisions seek to ensure that the prices of securities reflect their underlying economic value and, it is to the extent that a disclosure would occasion a difference between market price from true value, that it would involve a result that is contrary to the law’s object and intended operation.

76 Put another way, ANZ argues the primary judge appeared to hold that “persons who commonly invest in securities” should be taken to include persons who would trade on information that was irrelevant to value (and which had no demonstrable effect upon price) (at J [443]–[447]). ANZ submits that having regard to the statutory text, the object of the law, and the authorities, the primary judge ought to have concluded that the class of persons the subject of the statutory test would not trade on information of that nature. ANZ notes that the only persons that ASIC identified as investing based upon non-value relevant information were index funds, speculators and chartists (at J [338]).

77 ANZ further submits that to the extent the primary judge did rely upon the inclusion of the words “price or value” in s 677 (at J [444]) to support his Honour’s conclusion, this is said to be misconceived. Section 677 does not purport to derive any meaning from the words “price or value”; rather its purpose is to provide for when “a reasonable person would be taken to expect information to have a material effect on the price or value of ED securities”. The concept of “price or value” thus forms part of what is being deemed, not the elements that give rise to the deeming. To allow the meaning of “price or value” to affect the test would amount to circular reasoning.

E.2 Consideration

78 ANZ’s argument overcomplicates the statutory regime and does not withstand close analysis. The contention the materiality test requires the information to have an established economic value effect is a gloss. Relatedly, there no necessity to prove that a change in the price of securities occurred to establish liability.

79 As can be seen from the above (at [29]), s 674(2) relevantly conditions the obligation for a listed disclosing entity bound by a disclosure requirement in market listing rules to disclose if it is aware of the relevant information and it: (a) is not generally available; and (b) is information that a reasonable person would expect, if it were generally available, to have a material effect on the price or value of ED securities of the entity.

80 Section 677 then provides that the expression “to have a material effect on the price or value” of the entity’s securities, be given an expansive meaning. Specifically, s 677 states that a reasonable person would be taken to expect information to have a material effect on the price or value of the securities if:

the information would, or would be likely to, influence persons who commonly invest in securities in deciding whether to acquire or dispose of the [entity’s securities].

81 Both the purpose and the effect of this provision is evident: the “deeming” provision applies to satisfy the requirements of Listing Rule 3.1: Grant-Taylor (FC) (at 419–420 [95]); Jubilee Mines (at 309 [34], 315–317 [54]–[62]). Provided other requirements of disclosure are present, it is relevantly sufficient (and necessary) if the information would be likely to influence the investment decisions of potential investors. There is no other relevant requirement, but the notion of “influence” reflects the fact that the obligation is conditioned upon materiality, as the relevant information must be of a particular character, that is, it would, or be likely to, influence persons who commonly invest in securities to decide to acquire or dispose of an entity’s securities (and not merely be an immaterial factor in making such a decision).

82 As explained above, those responsible for disclosure are required to engage in a predictive and hypothetical analysis. There is a need for an entity’s officers to put themselves into the shoes of persons who commonly invest in securities and form a hypothetical view as to whether the information would have influenced their decision to acquire or dispose of the entity’s securities.

83 This will be easy in some circumstances – where the information, if disclosed, is likely to be plainly price and value positive or negative because it squarely goes to the present value of future cash flows – but at the margins, the ex-ante assessment may be more difficult.

84 Any inquiry into compliance with the obligation involves a question of fact: and its focus is on the time at which it is alleged that the disclosure should have occurred and involves a survey of all the relevant material. As I have explained above, evidence as to ex-post price effect of disclosure of the information in the real world may be of assistance to test the cogency of the ex-ante analysis, but it is only a tool to the extent the circumstances are such that a subsequent event, in the circumstances of the case, can rationally (directly or indirectly) bear upon the ex-ante assessment.

85 As the Full Court observed in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd [2011] FCAFC 19; (2011) 190 FCR 364 (Fortescue (FC)) (at 424–425 [188] per Keane CJ, Emmett and Finkelstein JJ agreeing), the test of “likely to influence” in s 677(1) “is not a high threshold” (an observation not disapproved on appeal in Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; (2012) 247 CLR 486).

86 In the end, as noted above, the resolution of the question of materiality is a matter of judgment, informed by commercial commonsense and it demands appreciation of any relevant broader context, investor experience and intuitive realism: GetSwift (at [1101], [1165], [1240] and [1259]). To erect some test based on fundamental value is as erroneous as adopting a rigid numerical formula based upon a percentage of price movement in the share price upon any corrective disclosure. Notably, in applying a statutory test which does not include an expansive provision such as s 677, Courts in the United States have nonetheless also rejected “bright line” approaches. As reaffirmed by Sotomayor J (on behalf of a unanimous Supreme Court) in Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 563 U.S. 27 (2011), materiality is satisfied when there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available” (see also Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1988) (at 231–232 per Blackmun J, Brennan, Marshall, Stevens, White and O’Connor JJ agreeing). Like in the United States, “[a]ny approach that designates a single fact or occurrence as always determinative of an inherently fact-specific finding such as materiality must necessarily be overinclusive or underinclusive”: Basic, Inc. v. Levinson (at 236).

87 At the risk of repetition, ASIC’s allegation of contravention did not require it to establish, or the Court to find, an actual effect on the price or value of ANZ’s shares by reason of the failure to disclose the pleaded information and, in particular, the terms of s 677 do not mandate an inquiry as to whether any change in the price of securities has occurred: see Fortescue (FC) (at 424–425 [188]).

88 This approach makes sense when one has regard to ANZ’s argument that ASIC was required to prove the pleaded information was relevant to the fundamental value of ANZ’s shares. Although an objective of the disclosure regime is to align the price of securities with their underlying fundamental value, a moment’s thought reveals that this alignment is not always present.

89 As ASIC correctly submits, the primary purpose of continuous disclosure is to ensure the existence of an informed market for financial products. Disclosing entities are required to disclose materially price sensitive information on a continuous basis to all categories of investors. The continuous disclosure regime does not give companies a right to withhold information because the company’s officers form the opinion that disclosure might cause a misalignment between price and what those officers perceive, at any one time, to be the value of the company’s securities.

90 Any notion that s 677 only has an operation whereby the relevant information could only have a relevant impact upon fundamental value is not only acontextual (giving insufficient attention to the alternative concept of “price”) but, when one has regards to purpose, makes little practical sense when one considers the way the market operates in the real world and the forensic realities in sometimes proving changes in the fundamental value of a share.

91 It is unnecessary to get into the weeds of economic theory, but the fundamental value of a security is the expected risk-adjusted present value of all free cash flows. But, as was noted during oral argument, one cannot ignore the evidence that a market can misprice securities and there are well-known empirical limitations that demonstrate some limitation in the efficient market hypothesis (at least in its strong or semi-strong form). Indeed, it is trite that a perceived discrepancy between market price and estimated intrinsic or fundamental value of a share is the measure of opportunity for those engaged in making investment decisions based upon fundamental analysis.

92 A further complication, evident in this case, is where an alleged contravener never makes what is said to be a “corrective disclosure”. The conduct of an event study seeking to determine any departure of a share price from “true” value – including for use as a cross-check as to materiality – may have utility in some cases but it will be unnecessary in others. Notably, in the present case, the primary judge concluded that the absence of any corrective disclosure was one factor relevant to his Honour’s determination that the expert evidence of Mr Holzwarth, called by ANZ, was not to be accorded significant weight (at J [309], [321] and [331]–[333]).

93 There is no circularity of reasoning in recognising, as the primary judge did (at J [445]), that prices can sometimes diverge from value. Moreover, as the primary judge noted (at J [444]), the words “price or value” not only appear in each of s 674(2)(c)(ii) and s 677, but also in Listing Rule 3.1 and, as his Honour noted (at J [381] and [444]), they appear in the Introduction to the Listing Rules, as part of the statement of the principles upon which the Listing Rules are based, and the “natural way to read [price or value] is as alternatives”.

94 On proper examination, nothing said by Nicholas J in Vocation is inconsistent with the above. His Honour (at [552] and [553]) was dealing with an argument that the evidence of ASIC’s expert, given in relation to the investing behaviour of institutional investors, was incapable of providing a sufficient basis from which to draw a conclusion in relation to the behaviour of the broader class of “persons who commonly invest in securities”. Nicholas J rejected that submission. But his Honour was not addressing the matters upon which ANZ relies. Further, as ASIC submits, in circumstances where Nicholas J – like the primary judge here – noted and purported to apply the statements of the Full Court in Grant-Taylor (FC) as to the meaning of the expression “persons who commonly invest in securities”, it would be wrong to construe his Honour’s observations in such a way that one effectively excludes from the class those persons for whom price is a relevant consideration.

95 There is a danger in putting a gloss on the phrase “persons who commonly invest in securities” in s 677. Although the use of the word “invest” rather than “purchase” or “acquire” suggests that the hypothetical reasonable person excludes “irrational” purchasers, this reflects that persons who commonly invest in securities are likely to act rationally, and is consistent with the notion that inconsequential information, irrelevant to a company’s financial position, is unlikely to change investors’ collective valuation and is not information that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect.

E.3 Conclusion on Ground 1

96 The approach of the primary judge to the construction and application of s 677 was in accordance with authority. In particular, his Honour did not fall into error in the way he applied the principles explained by the Full Court in Grant-Taylor (FC).

F GROUNDS 2 AND 3

97 As has been explained by Button J, Grounds 2 and 3 attack the primary judge’s finding on materiality having regard to what are said to be four pieces of “further information”, of which ANZ says it was aware.

98 These specifics of the further information and the relevant evidence is helpfully set out, in detail, in Button J’s reasons. As to the information referred to in paragraphs 2(d)(i) and (ii) of the notice of appeal, I agree with Button J that there was no error in his Honour’s conclusion that these matters had any bearing on the materiality of the pleaded information.

99 I will describe the balance of the further information relied upon by ANZ as the contextual material.

100 It is sufficient for present purposes to note that the primary judge accurately captured the contextual material (at J [453(e)–(f)]) as follows:

ANZ submits that the “information” (within the meaning of the ASX Listing Rules) that ANZ had (in the sense of being aware of it) was:

...

(e) that the Joint Lead Managers’ intentions in the aftermarket were not to be short-term sellers, which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this; and

(f) that the Joint Lead Managers had entered into hedges to manage their risk from acquiring Placement shares, which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this.

101 Button J explains the pleaded information was found to be material based on the prompt seller inference, that is, that receipt of that information would lead those who commonly invest in securities to expect that the Underwriters would promptly dispose of the shares and, in so doing, put downward pressure on the share price. More specifically, the primary judge found “if the pleaded information had been disclosed, persons who commonly invest in securities would have held an expectation that the Underwriters would promptly dispose of allocated or acquired Placement shares, and in so doing place downward pressure on ANZ’s share price” (at J [436]). In reaching this conclusion, his Honour placed some significance on Mr Pratt’s testimony that “market participants would expect the Underwriters to sell down their positions in the short to medium term” (at J [438]).

102 However, ANZ’s contention is that when viewed in the light of the contextual material, the “prompt seller inference” would not arise, as the Underwriters would not sell the issued shares promptly and disclosure of the pleaded information would have been misleading.

103 The primary judge then explained that although the way in which ANZ captured the Underwriters’ intentions was broadly correct, their positions as to selling were “expressed in very general terms and were still the subject of further consideration” (at J [459]). His Honour explained this conclusion by noting (at J [459]–[461]):

(a) … one of the purposes of the calls on the morning of 7 August 2015 was for Mr Moscati to confirm with the Joint Lead Managers that the Joint Lead Managers would not quickly dispose of their shares in a way that might affect an otherwise orderly after-market in ANZ shares.

(b) The general tenor of the separate calls with each of the Joint Lead Managers on the morning of 7 August 2015 (before 10.00 am) was that they would “do the right thing” in the sense that they would manage the situation appropriately and would not sell down their positions in ANZ shares quickly or in a way that would create a disorderly market. The Joint Lead Managers did not present any detail as to how and when they would sell down their shares.

(c) During the conference call that commenced at 10.00 am on 7 August 2015 (which took place after the relevant times) the Joint Lead Managers stated that they would not sell down their positions that day and that they would give further consideration as to how to manage the situation and come back to ANZ with more detail the next day.

(Emphasis added)

104 It followed, according to the primary judge, that the contextual information did not affect the materiality of the pleaded information.

105 I respectfully agree with Button J that the general assurances given by senior personnel in the Underwriters were subjectively credible to those to whom they were conveyed but, in my respectful view, this is insufficient to demonstrate error in his Honour’s conclusion that those assurances, expressed in “very general terms” and which were “subject of further consideration”, meant that the pleaded information was not material.

106 As I have explained, the test is a wholly objective one. Although the subjective views of ANZ are not to the point, it is worth remarking that the mere fact that assurances were sought by senior officers of ANZ demonstrates that there was a real and abiding concern for reassurance. Irrespective of the views held within ANZ following the general and preliminary assurances made, it was open for his Honour to conclude, on the evidence, that if the pleaded information had been disclosed, persons who commonly invest in securities would have held an expectation that the Underwriters would promptly dispose of allocated or acquired placement shares, and in so doing, place downward pressure on ANZ’s share price. No doubt that when disclosing the pleaded information further material going to the opinion of ANZ officers as to risk could have been accurately conveyed to the market – one can also assume that these opinions could (or even would) have affected the extent of the market reaction to the disclosure of the pleaded information, but this is not to the point when one is assessing whether the failure to disclose the pleaded information amounted to contravening conduct. Put another way, there was no error in his Honour concluding the disclosure of the pleaded information would have been viewed by the hypothetical investor as having altered the total mix of information available in such a way as would be expected to have a “material effect” on the price or value of ANZ shares.

107 His Honour’s findings provided a sufficient basis for establishing materiality. I do not consider there is any substance in Grounds 2 and 3.

G GROUND 4

108 As noted above, I agree with Button J’s rejection of Ground 4. Her Honour has explained the ground and set out ANZ’s submissions.

109 The approach of the primary judge was entirely orthodox. His Honour concluded the words “concerning it” have their ordinary (and broad) natural meaning, and that this unsurprising approach to the text was likely to further the object of the continuous disclosure regime (and was also consistent with the examples provided by the ASX illustrating the operation of Listing Rule 3.1).

110 ANZ’s contention that his Honour’s construction of what was meant by “concerning it” would lead to listed entities being routinely required to disclose the trading intentions of shareholders is not only belied by the everyday experience of the operation of the continuous disclosure regime but does not bear analysis. The only reason why disclosure was required to the ASX was because Listing Rule 3.1 was engaged and the exceptions to Listing Rule 3.1A were not.

111 As Button J notes, the continuous disclosure regime is carefully drafted and calibrated. The operation of the regime (leaving aside Listing Rule 3.1B) is well set out by the overview provided in Guidance Note 8 (at [2]):

112 When taken together, Listing Rules 3.1, 3.1A and 3.1B constitute an integrated whole which reflects an intention to strike what the market operator regards as “an appropriate balance between the interests of the market in receiving information that will affect the price or value of, or which is needed to correct or prevent a false market in, an entity’s securities at the earliest reasonable time, and the interests of the entity in not having to disclose information prematurely or where it would clearly be inappropriate to do so”: see Guidance Note 8 (at [3]).

113 ANZ’s attempt to introduce a gloss to achieve a “balance” by creating an artificial demarcation between information that may concern the subjective intentions of shareholders with information concerning the entity, is misconceived.

H CONCLUSION AND ORDERS

114 It follows that all the questions I identified above (at [14]) should be answered in the negative and no error has been established.

115 The appeal ought to be dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and twelve (112) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

Dated: 2 October 2024

BUTTON J:

116 The background is set out in the reasons of Lee J and in the primary judge’s reasons on liability (LJ). It need not be rehearsed here.

GROUND 1

117 I have had the benefit of a draft of Lee J’s reasons. I agree that there is no merit in ground 1, for the reasons his Honour gives.

GROUNDS 2 AND 3

118 Grounds 2 and 3 impugn the primary judge’s finding on materiality having regard to four pieces of “further information”, of which ANZ says it was aware. ANZ contended that, once the pleaded information is viewed in light of those pieces of further information, the pleaded information is shown not to be material and is also shown to itself be misleading, as disclosure of the pleaded information alone would convey a false or misleading impression.

119 The four pieces of further information raised by the Notice of Appeal (in paragraph 2(d)) are as follows:

(i) the book was fully covered (LJ [290]), which ANZ understood to be the case (LJ [128]);

(ii) at least one reason, communicated to ANZ, for the Underwriters recommending that they allocate approximately $754 million of the shares to themselves was to avoid a situation in which the shares were allocated to certain hedge funds who might sell their allocated shares quickly and thereby create a disorderly market (LJ [295]);

(iii) the Underwriters had communicated to ANZ that they would not sell down their position quickly or in a way that would create a disorderly after-market (LJ [181], [101]) and were in no rush to sell any shares they acquired (LJ [131]); and

(iv) ANZ’s understanding was that the Underwriters would not quickly dispose of their shares in a way that might affect an otherwise orderly after-market in ANZ shares and that they had the capacity to achieve this (LJ [101], [165], [441(a)]).

120 The primary judge structured his reasons by first addressing the materiality of the pleaded information, and then considering whether any of the contextual information relied on by ANZ — the key elements of which constitute the further information relied on in the appeal — revealed the pleaded information not to be material, either individually or in combination with one another. The primary judge identified that his reasons took that staged approach, and said the approach was consistent with the structure of ANZ’s submissions (LJ [430]). While ANZ was somewhat critical of the staged approach on appeal, it did not refute that the approach taken by the primary judge accorded with the way it presented its case in submissions. I need say nothing more about that particular matter save to say that I see no error in his Honour’s approach.

121 The information that ASIC contended ought to have been disclosed was put in two alternate ways. These were set out by the primary judge as follows (LJ [8]):

(a) that, of the $2.5 billion of ANZ shares offered in the Placement, shares with a value between approximately $754 million and $790 million were to be acquired by the Underwriters (the Underwriter Acquisition Information); or alternatively

(b) that a significant proportion of the shares the subject of the Placement were to be acquired by the Underwriters (the Significant Proportion Information).

122 The primary judge used the term “the pleaded information” to refer to the Underwriter Acquisition Information and the Significant Proportion Information together (LJ [396]).

123 The primary judge accepted ASIC’s contention on materiality as follows (LJ [436]):

I accept ASIC’s contention that, if the pleaded information had been disclosed, persons who commonly invest in securities would have held an expectation that the Underwriters would promptly dispose of allocated or acquired Placement shares, and in so doing place downward pressure on ANZ’s share price.

124 Two things should be observed. First, it is clear from the terms in which the primary judge expressed this finding, that materiality was established by reference to s 677 (rather than directly under s 674(2)(c)(ii)). Secondly, the pleaded information was found to be material on the basis that receipt of that information would lead those who commonly invest in securities to expect that the Underwriters would promptly dispose of the shares and, in so doing, put downward pressure on the share price. This inference was referred to in argument as the prompt seller inference.

125 On the appeal, ANZ did not challenge the primary judge’s finding that, taken alone, disclosure of the pleaded information would give rise to the prompt seller inference and would be material on that basis. Rather, the burden of ANZ’s argument on grounds 2 and 3 was that, when the pleaded information is viewed in the context of the further information — being information that ANZ had — the prompt seller inference would not arise, as the further information reveals that the Underwriters did not intend to dispose of the placement shares promptly. More than that, ANZ contended that, as the further information reveals that the Underwriters would not sell the placement shares promptly, disclosure of the pleaded information alone would be misleading or materially incomplete.

126 The primary judge summarised ANZ’s submissions on the “information” ANZ submitted it had (in the sense of being aware of it) in the reasons (LJ [453]). On appeal, ANZ accepted that the primary judge had accurately captured its submissions in the following paragraphs of the judgment (LJ [453]):

ANZ submits that the “information” (within the meaning of the ASX Listing Rules) that ANZ had (in the sense of being aware of it) was:

(a) that the Joint Lead Managers had recommended to ANZ, and it had accepted, that they should acquire a significant proportion of the Placement shares, and hence that the Joint Lead Managers were to acquire a significant proportion of the Placement Shares (which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this). This is the pleaded information on which ASIC’s claim is based;

(b) that the Joint Lead Managers were to acquire a significant proportion of the Placement shares because they recommended scaling-back certain hedge fund investors. ANZ was aware of this because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this. Indeed, ANZ only had the information in paragraph (a) (and on which ASIC focuses) by reason of it being given the information in paragraph (b) and ANZ accepting the Joint Lead Managers’ recommendation that they take up a portion of the Placement shares in the context of ANZ being informed of the other matters below;

(c) that a substantial reason for the Joint Lead Managers recommending scaling-back hedge funds was that if not scaled-back they might deal with their shares in such a way as to create a disorderly, or volatile, after-market for ANZ shares;

(d) that the book was covered, which ANZ was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this;

(e) that the Joint Lead Managers’ intentions in the aftermarket were not to be short-term sellers, which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this; and

(f) that the Joint Lead Managers had entered into hedges to manage their risk from acquiring Placement shares, which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this.

127 In addressing the significance of the further information, the primary judge first confirmed the applicable principles. His Honour accepted (LJ [455]) that the applicable principles were as stated by Nicholas J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vocation Ltd (2019) 371 ALR 155; [2019] FCA 807 (Vocation) at [566], being a passage quoted earlier in his Honour’s reasons. In the paragraph of Vocation adopted by the primary judge, Nicholas J said (Vocation at [566], quoted LJ [448]):

Properly understood, Jubilee is authority for the proposition that information that is alleged by a plaintiff to be material, may need to be considered in its broader context for the purpose of determining whether it satisfies the relevant statutory test of materiality. For that reason it will often be necessary to consider whether there is additional information beyond what is alleged not to have been disclosed and what impact it would have on the assessment of the information that the plaintiff alleges should have been disclosed.

128 The primary judge also referred (LJ [448]) to the importance of considering the totality of relevant information as having been established and discussed in a number of cases: citing Jubilee Mines NL v Riley (2009) 40 WAR 299; [2009] WASCA 62 at [87]–[90] (Martin CJ, Le Miere AJA agreeing at [199]), [161]–[162] (McLure JA); Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) (2015) 322 ALR 723; [2015] FCA 149 at [96]–[101] (Perram J); Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Ltd (in liq) (2016) 245 FCR 402; [2016] FCAFC 60 (Grant-Taylor) at [149] (Allsop CJ, Gilmour and Beach JJ); Bert v Red 5 Ltd (2016) 349 ALR 210; [2016] QSC 302 at [19], [117], [210]–[211] (Applegarth J). See also Australian Securities and Investments Commission v GetSwift Ltd (Liability Hearing) [2021] FCA 1384 at [1102] (Lee J); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Wilson (No 3) [2023] FCA 1009 at [148] (Jackson J).

129 As the primary judge observed, the principles concerning contextual, or further, information have been established in a number of cases. They are not controversial. What is controversial is the application of those principles to the facts as found.

130 The primary judge addressed, separately, each item of further information referred to in LJ [453(b)–(f)], albeit not in the same order as the items of further information are raised in the Notice of Appeal.

131 I will address the items of information in the following order: first the Underwriters’ intentions and ANZ’s knowledge of those intentions, which constituted the focus on appeal; next, the book coverage; and finally, the reasons for the Underwriters’ intentions.

The Underwriters’ intentions

132 The third and fourth pieces of information that are the subject of grounds 2 and 3 of the Notice of Appeal concern the Underwriters’ intentions, and ANZ’s knowledge of those intentions. Those two items of information, as set out in the Notice of Appeal, are as follows:

(iii) the JLMs had communicated to ANZ that they would not sell down their position quickly or in a way that would create a disorderly after-market (LJ[181], [101]) and were in no rush to sell any shares they acquired (LJ[131]); and

(iv) ANZ’s understanding was that the JLMs would not quickly dispose of their shares in a way that might affect an otherwise orderly after-market in ANZ shares and that they had the capacity to achieve this (LJ[101], [165], [441(a)]).

133 These items of information were also raised before the primary judge, although cast in slightly different terms (LJ [453(e)–(f)]):

(e) that the Joint Lead Managers’ intentions in the aftermarket were not to be short-term sellers, which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this; and

(f) that the Joint Lead Managers had entered into hedges to manage their risk from acquiring Placement shares, which it was aware of because the Joint Lead Managers had told ANZ this.

134 Given that the contraventions alleged and found relate to the failure to disclose the pleaded information before the market opened, it is the intentions of the Underwriters and communications regarding those intentions before the market opened that are relevant to this ground. That is important given that communications between ANZ and the Underwriters included a conference call at about 10.00am on 7 August 2015. Counsel for ANZ was clear that it was interactions prior to the market opening that were relied on as founding the contextual information comprising the Underwriters’ intentions and ANZ’s knowledge of those intentions. The exclusion of events at and after 10.00am is important because, as will be explained, some of the primary judge’s findings were stated in terms that include the call at about 10.00am, but others do not.

The factual narrative concerning the Underwriters’ intentions and communications with ANZ

135 To properly understand the primary judge’s findings regarding the Underwriters’ intentions and ANZ’s knowledge of those intentions — which findings were not challenged on the appeal — it is necessary to say something about the course of events in respect of which those findings were made.

136 ANZ’s shares entered a trading halt at 8.38am on 6 August 2015. At 8.44am that morning, ANZ issued a media release in relation to the placement. The media release noted that ANZ was announcing a fully underwritten institutional share placement to raise $2.5 billion, It identified the underwriters as Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Ltd (Citi), Deutsche Bank AG, Sydney Branch (Deutsche) and JP Morgan Australia Ltd (JPM). The book build commenced soon after the media release was issued at 8.44am.

137 The progress of the book build, the recommendation that placement shares be issued to the Underwriters, and interactions between ANZ and the Underwriters were covered in detail by the primary judge in his reasons.

138 The events included the following:

(1) Shortly after 2.34pm on 6 August 2015 there was a conference call between the Underwriters and ANZ at which ANZ was told, in substance, that the demand from long term investors was limited. This was reflected in a note Mr Needham (ANZ’s Head of Capital and Structured Funding) made during the call: “Long only funds not there”. This was negative news from ANZ’s point of view (LJ [92]–[94]).

(2) There was a further conference call with the Underwriters later during the afternoon of 6 August 2015. ANZ’s CFO, Shayne Elliot, Mr Needham and Mr Moscati (ANZ’s Group Treasurer) participated in the call (LJ [95]). Again, it was clear that the book build was not going well. The options identified were to reprice the share issue, or for only $1.5 to $1.8 billion of stock being issued to those on the book and for the Underwriters to “own it”, meaning to take the balance of the stock (LJ [98]). The Underwriters told ANZ that they were making that recommendation due to the number and size of the hedge fund bids in the book, and because there was a risk that over-allocating to the hedge funds could cause an unorderly after-market due to the risk of many of those hedge funds being short-term holders of the shares (LJ [100], [130]).

(3) The primary judge accepted Mr Needham’s evidence that it was his understanding that it was preferable for the Underwriters to hold stock rather than over-allocating to hedge funds because the Underwriters were large, well-capitalised financial institutions who were paid to take on risk under the Underwriting Agreement, and who had the ability to manage that risk “such that they did not need to promptly dispose of any stock allocated to them or to dispose of it in a way that could affect the share price” (LJ [101], emphasis added).

(4) Around 4.47pm on 6 August 2015, ANZ’s draft post-completion announcement was amended to remove a reference to the placement being significantly oversubscribed and well-supported by institutional investors (LJ [104]–[105]).

(5) There were a number of calls between the Underwriters as the book closure time of 6.00pm approached. To summarise, those calls included references to orders being placed in excess of true demand because bidders expected to be scaled back. Those involved in the calls drew a distinction between what was the formally allocable amount, and what could be allocated, in the sense of the amount that hedge funds and others were accustomed to receiving. Concerns were expressed that if the hedge funds were allocated stock in excess of their underlying demand, they may create a disorderly aftermarket (LJ [106]–[109]).

(6) The book-build closed at 6.00pm on 6 August 2015 (LJ [110]).

(7) At 8.35pm on 6 August 2015, Citi sent ANZ (copying representatives of JPM and Deutsche) a Draft Allocation List. That document set out that there was 103% coverage of the $2.5 billion to be raised, but also included a “Total Allocated” figure of $1,745,030,819 and a “Left to Allocate” figure of $754,969,181, being the dollar value of the placement shares that would be taken up by the Underwriters (LJ [111]–[116]).

(8) There was a conference call between the Underwriters and ANZ shortly after 8.35pm on 6 August 2015. Mr Needham took notes of the meeting. During the call, ANZ was told that interest from some segments of the market had gone backwards since the last update. One note made by Mr Needham was “Whole trade 10 days only”. Mr Needham’s recollection was that this was a comment made by the Underwriters to the effect that, in their view, if the sale of any shares allocated to them was undertaken over about 10 trading days, “it would not affect an otherwise orderly market for ANZ shares” (LJ [123]). ANZ was also told that long-only funds were largely still not coming in (LJ [124]).

(9) The primary judge summarised Mr Needham’s evidence about the call, including the following (LJ [125(c) and (e)]):