Federal Court of Australia

Veale v Coleman [2024] FCAFC 83

Table of Corrections | |

Order 3 of the Orders made on 20 June 2024 amended from “The appellant is to pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.” to “The respondent is to pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal.” |

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is allowed.

2. Set aside Order 1 of the Orders made by the primary judge on 29 August 2023 and the Order made by the primary judge on 13 October 2023 and in lieu thereof order that:

(a) The originating application filed by the applicant on 12 April 2023 is dismissed.

(b) The applicant is to pay the respondent’s costs of the originating application.

3. The respondent is to pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

THE COURT:

1 The appellant, Andrew William Veale, is a creditor of the respondent, David Coleman. On 23 March 2023, on the application of Mr Veale, bankruptcy notice BN 259365 (Bankruptcy Notice) was issued and subsequently served on Mr Coleman. Mr Coleman applied to have the Bankruptcy Notice set aside and on 29 August 2023 an order to that effect was made: see Coleman v Veale [2023] FCA 1023 (Coleman v Veale or PJ). On 13 October 2023 the Court made a further order requiring Mr Veale to pay 85% of Mr Coleman’s costs of the proceeding: see Coleman v Veale (No 2) [2023] FCA 1219.

2 Mr Veale now appeals from those orders. He raises 10 grounds of appeal in his notice of appeal filed on 27 September 2023 which, taken together, essentially raise two issues: whether the primary judge erred in finding that the Bankruptcy Notice did not comply with reg 12 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth); and, if there was any such non-compliance, whether the primary judge erred in failing to find that, pursuant to s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth), the Bankruptcy Notice was not invalidated because any defect or irregularity as found was formal and did not give rise to substantial injustice that could not be remedied by an order of the Court.

3 Before proceeding further, we note that to avoid confusion, notwithstanding that the Regulations are internally divided by “section”, we will use the description “regulation” or “reg” to describe individual sections of the Regulations and reserve the descriptor “section” to describe sections of the Bankruptcy Act.

4 Mr Coleman has filed a notice of contention in which he contends: first, that the primary judge erred in inferring that the Australian Financial Security Authority’s (AFSA) Online Services Portal (AFSA Online Portal) was the only means of generating a bankruptcy notice; and secondly, in relation to s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act, that the Bankruptcy Notice was invalid because it could reasonably have misled the debtor as to what was necessary to comply with it.

Application to serve fresh evidence on appeal

5 By interlocutory application, Mr Veale seeks leave to rely on fresh evidence on the appeal in the form of an affidavit of Robert Bennett, his solicitor. The additional evidence goes to ground 2 of the notice of appeal by which Mr Veale contends that the primary judge erred in his construction of reg 12(3) of the Regulations.

6 In his affidavit Mr Bennett proposes to give both additional evidence, that is, evidence that could have been led before the primary judge and new evidence in relation to events that postdate the decision under appeal.

7 Section 27 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) permits the Court to receive further evidence on appeal including by affidavit. In Northern Land Council v Quall (No 3) [2021] FCAFC 2 at [16] a Full Court of this Court (Griffiths, Mortimer (as her Honour then was) and White JJ), drawing on a number of authorities, summarised the principles which apply to an application made under s 27 of the FCA Act as follows:

(1) The discretion conferred by s 27 is unfettered, save that it must be exercised judicially and according to principle.

(2) The power to receive further evidence is remedial and its primary purpose is to empower the Court to receive further evidence to ensure that proceedings do not miscarry.

(3) The power is not constrained by common law rules that govern the grant of new trials on the ground of discovery of “fresh evidence”.

(4) The following two considerations will normally be relevant to the exercise of the discretion:

(i) the further evidence is such that, had it been adduced at trial, the result would very probably have been different; and

(ii) the party seeking to adduce the evidence demonstrates that it was unaware of the evidence and could not have been, with reasonable diligence, made aware of the evidence;

(5) The interests of third parties and the public at large may outweigh a party’s interest in the finality of litigation. For example, a greater willingness to receive further evidence on appeal has been apparent in bankruptcy matters which affect the interests of creditors generally.

8 The additional evidence that Mr Veale seeks to rely on is to the effect that at the relevant time the AFSA Online Portal was the only means by which a creditor could apply for the issue of a bankruptcy notice. The primary judge was prepared to infer, if necessary, that was the case: at PJ [54]. By his notice of contention Mr Coleman seeks to challenge the drawing of that inference. Mr Bennett undertook investigations after the primary judge delivered his reasons and, we infer in response to ground 1 of the notice of contention, in relation to that issue.

9 The evidence goes further. Mr Bennett also expresses the view that at the time of the issue of the Bankruptcy Notice, given the AFSA Online Portal is the only way to apply for the issue of a bankruptcy notice, the limitations of that portal and the effect of the combination of findings in Coleman v Gannaway [2023] FCA 224 and in Coleman v Veale, it was not possible to issue a bankruptcy notice in Australia for a judgment in a foreign currency without breaching reg 12 of the Regulations.

10 We would not allow Mr Veale to rely on this additional evidence on the appeal. Mr Veale has not demonstrated that, had it been adduced at trial, the evidence would probably have led to a different result. Indeed, given the primary judge’s reasoning and the fact that his Honour was in any event prepared to draw an inference to the same effect, it is unlikely that it would have done so. Further, Mr Veale has not demonstrated that he was not aware of the evidence or that he could not, with further diligence, have obtained it.

11 The new evidence, which was not available at the time of the hearing, is directed to establishing that there have been changes to the AFSA Online Portal since Coleman v Veale in that the “RBA exchange rate field in the bankruptcy notice (Notes [sic] A) now displays the rate to 5 decimal places”. Based on Mr Bennett’s attempts to generate a bankruptcy notice after this change was implemented, every bankruptcy notice which includes a currency conversion will now display a rate to five decimal places regardless of the number of decimal places entered into the RBA exchange rate dialogue box on the AFSA Online Portal.

12 Again, we are not persuaded to admit this evidence. While it could not have been adduced at trial, it bears no direct relevance to the matters in issue on the appeal.

Background

13 The background to the issue of the Bankruptcy Notice is not controversial. The primary judge succinctly summarised it at PJ [2]-[5] as follows:

2 On 28 June 2021 the respondent succeeded in obtaining a judgment against the applicant, in the District Court of the Republic of Singapore, in the amount of USD 150,000 plus interest at 5.33 percent per annum from the date of the writ of summons (which was 25 January 2018) to the date of payment (the Singapore trial judgment). The applicant appealed. The High Court of Singapore dismissed the appeal on 18 January 2022 (the Singapore appeal judgment). In doing so, the appellate court ordered that the costs of the proceedings be fixed at SGD 15,000 and ordered the release to the respondent of an amount of SGD 3,000 which the applicant had been ordered to pay as security for costs.

3 These two judgments were registered by the Supreme Court of New South Wales on 16 August 2022 (the NSW judgment). The NSW judgment is for the following amounts:

(a) USD 186,471.25, being the principal amount of the Singapore trial judgment plus accrued interest;

(b) AUD 12,396.64, being the AUD equivalent of the SGD 12,000 remaining to be paid by way of costs under the Singapore appeal judgment; and

(c) AUD 7,964.18, being the respondent’s costs of applying for registration.

4 The respondent obtained the issue of a bankruptcy notice in respect of the NSW judgment on 20 February 2023. That notice was set aside by this Court, by consent, on 21 March 2023. It has no further relevance, except that the respondent was ordered to pay the applicant’s costs fixed in the sum of $3,700 (the costs order).

5 On 21 March 2023 the respondent’s solicitor made a fresh application to the Official Receiver for the issue of a bankruptcy notice to the applicant. The notice with which the Court is presently concerned was issued, in response to that application, on 23 March 2023.

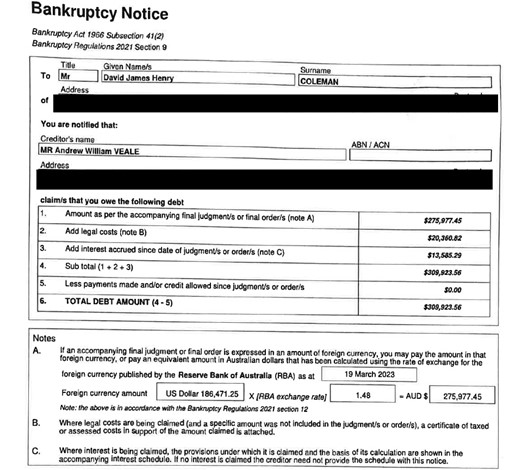

14 The first page of the Bankruptcy Notice (with addresses redacted) is reproduced below:

15 The “accompanying final judgment/s or final order/s” referred to at item 1 was for USD$186,471.25.

16 For the purposes of this appeal, the salient part of the Bankruptcy Notice is Note A and in particular the information included as to:

(1) the “as at” date of “the rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA)” which is stated to be “19 March 2023”; and

(2) the numerical values in the fields for “[RBA exchange rate]” and “AUD$” in the following calculation:

Foreign currency amount US Dollar 186,471.25 X [RBA exchange rate] 1.48 = AUD $275,977.45

17 The selection of these numerical values by Mr Bennett when applying for the issue of the Bankruptcy Notice was informed by what was then the recent decision in Gannaway. That case also concerned a bankruptcy notice addressed to Mr Coleman. Mr Bennett considered the decision in Gannaway at the time he completed the application for the Bankruptcy Notice on behalf of Mr Veale. We return to Gannaway below.

18 At this point we pause to note that:

(1) the numerical values inserted into the calculation in Note A resulted in a calculation that was mathematically correct: 186,471.25 x 1.48 = 275,977.45;

(2) the RBA does not publish an exchange rate for the conversion of foreign currency into Australian dollars. It does publish an exchange rate (expressed to a maximum of four decimal points) for the conversion of Australian dollars into designated foreign currencies. It only publishes those rates on weekdays, not weekends;

(3) an applicant for the issue of a bankruptcy notice in respect of a judgment expressed in a foreign currency is required, for the purpose of converting the foreign currency into Australian dollars, to use the RBA rate published two business days before the application for the notice is lodged: reg 12(3);

(4) the date that was two business days before the application was made for the Bankruptcy Notice was Friday, 17 March 2023. The RBA rate for the conversion of Australian dollars into US dollars on 17 March 2023 was 0.6714;

(5) as at Sunday, 19 March 2023, the then last published RBA rate for the conversion of Australian dollars into US dollars was that published on Friday, 17 March 2023, namely 0.6714;

(6) as explained by Mr Bennett:

(a) the exchange rate used in the Bankruptcy Notice was derived by:

(i) dividing 1 by the relevant exchange rate, 0.6714, which equals, when expressed to four decimal places, 1.4894; and

(ii) rounding that quotient to two decimal places to give a conversion rate of 1.48. Mr Bennett observed that 1.4894 when rounded to two decimal places would usually yield 1.49 because 0.0094 would be rounded up to 0.01 but that if the rate of 1.49 was used, the Bankruptcy Notice would overstate the amount of the debt. Accordingly, Mr Bennett rounded down to 1.48; and

(b) he used two decimal places for the currency conversion to avoid any discrepancy between the calculated figure and the numbers appearing in the calculation in Note A of the Bankruptcy Notice because he understood that to be the correct method based on Gannaway;

(7) Mr Bennett’s approach resulted in the Australian currency “equivalent” of the judgment obtained in a foreign currency being understated on the Bankruptcy Notice; and

(8) subject to its validity, the effect of the Bankruptcy Notice was to reserve to Mr Coleman the choice of whether to comply by payment of either:

(a) the final judgment or final order in the sum of USD186,471.25; or

(b) the amount in Australian dollars nominated by Mr Veale as the equivalent, namely $275,977.45 which was in fact understated.

19 The final matter of background is to note that the primary judge’s decision was informed by considerations of comity. Notwithstanding that the primary judge recognised the obvious injustice of finding that the Bankruptcy Notice was invalid, his Honour considered himself as being “driven to conclude that the defects in compliance with [reg] 12(2) in the present case lead to the invalidity of the notice” essentially as a matter of comity: PJ [59]-[60]. In that regard, the primary judge followed the decision in Parianos v Lymlind Pty Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 191 (Sackville J) as had Jackman J in Gannaway. Parianos was concerned with reg 4.04 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 1996 (Cth) (repealed) (1996 Regulations), which is the predecessor regulation to what is now reg 12.

20 Relevantly, the decision in Parianos extended the principle articulated by the High Court in Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd v Crowl (1988)165 CLR 71. In Kleinwort Benson the High Court held that a bankruptcy notice is a nullity if it fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Bankruptcy Act, or if it could reasonably mislead a debtor as to what is necessary to comply with the notice. In such cases the notice is a nullity whether or not the debtor in fact is misled: at 79 to 80 (Mason CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ). In Parianos the creditors did not submit that a distinction should be drawn between a requirement made essential as to the validity of a bankruptcy notice by the Bankruptcy Act and one rendered essential by a valid regulation made pursuant to the Bankruptcy Act. Justice Sackville opined that there would be “no sensible basis for drawing such a distinction, since the requirements for a bankruptcy notice can be and often are stated in regulations”: at [15]. Accordingly, in Parianos the question that fell to be determined was whether the regulation in question, reg 4.04 of the 1996 Regulations, stated an essential requirement for a bankruptcy notice and if so, whether the notice in that case failed to comply with that requirement.

21 The primary judge and Jackman J in Gannaway did not regard Parianos as capable of being distinguished on the basis of the current formulation of the relevant regulation: Gannaway [33]; PJ [58]. While the primary judge observed that he had some reservations about the reasoning in Parianos, he followed Parianos because it had stood as authority for more than 20 years and he did not think it was plainly wrong: PJ [59]. While it is correct that Parianos is over 20 years old, the parties did not refer to any intermediate appellate authority in which it had been relevantly applied. Similarly, our own research has not revealed any such authority.

22 We address the relevance of Parianos to this appeal in some detail below. It is sufficient for present purposes to note that this Court is not constrained by the considerations of comity that the primary judge faced: see Herzfeld PD and Prince T, Interpretation (2nd ed, Thomson Reuters, 2020) at [33.380]-[33.390]. Indeed, even if it is accepted that Parianos is not capable of being distinguished by reason of the wording in the current iteration of the Regulations, in circumstances where there is no decision on point from an intermediate court of appeal, this Court need not be satisfied that the decision in Parianos is plainly wrong in order to depart from it.

Legislative regime and some principles

Bankruptcy notices

23 Section 41 of the Bankruptcy Act concerns bankruptcy notices. It relevantly provides:

(1) An Official Receiver may issue a bankruptcy notice on the application of a creditor who has obtained against a debtor:

(a) a final judgment or final order that:

(i) is of the kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g); and

(ii) is for an amount of at least the statutory minimum; or

(b) 2 or more final judgments or final orders that:

(i) are of the kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g); and

(ii) taken together are for an amount of at least the statutory minimum.

(2) The notice must be in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations.

Section 5 of the Bankruptcy Act provides that unless a greater amount is prescribed the statutory minimum is $5,000. A final judgment or final order of the kind described in s 40(1)(g) of the Bankruptcy Act is “a judgment or order the execution of which has not been stayed”.

24 In Adams v Lambert (2006) 228 CLR 409 the High Court, in the context of considering whether the requirement to state the provision under which interest is being claimed is an essential requirement for the purposes of s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act (see below), said at [14]:

The requirement in question is established by three levels of prescription. Section 41(2) of the Act states that a bankruptcy notice must be in the form prescribed by the regulations. Regulation 4.02 states that, for the purposes of s 41(2), the form set out in Form 1 is prescribed. Note 2 to the Schedule in Form 1 states that a document attached to the notice must state the provisions under which interest is being claimed. The use of the word “must” is significant, but it should be kept in perspective. A prescription as to a form to be followed will normally be expressed in language of obligation rather than of permission. That is the idea of a form. Such a prescription raises the question to be considered in the present case; it does not answer it.

25 Division 1 of Pt 4 of the Regulations concerns bankruptcy notices and relevantly includes:

8 Application for bankruptcy notice

(1) This section sets out the requirements for an application to the Official Receiver for a bankruptcy notice by a person who has obtained against a debtor one, or 2 or more, final judgments or final orders of a kind described in paragraph 40(1)(g) of the Act.

…

(2) The application must be in the approved form.

…

9 Form of bankruptcy notice

(1) For the purposes of subsection 41(2) of the Act, the form of bankruptcy notice set out in Schedule 1 is prescribed.

(2) A bankruptcy notice must follow that form in respect of its format (for example, bold or italic typeface, underlining and notes).

(3) Subsection (2) does not limit section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901.

…

12 Judgment or order in foreign currency

(1) This section applies in relation to a bankruptcy notice issued by the Official Receiver in relation to a debtor if the notice includes a final judgment, or final order, that is expressed in an amount of foreign currency (whether or not the judgment or order is also expressed in an amount of Australian currency).

(2) The bankruptcy notice must include the following:

(a) a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay:

(i) the amount of foreign currency; or

(ii) the equivalent amount of Australian currency;

(b) the conversion calculation for the equivalent amount of Australian currency;

(c) a statement to the effect that the conversion of the amount of foreign currency into the equivalent amount of Australian currency has been made in accordance with this section.

(3) For the purposes of subparagraph (2)(a)(ii), the equivalent amount of Australian currency is the amount worked out using the rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the Reserve Bank of Australia in relation to the day that is 2 business days before the day on which the application for the notice is made.

Note: The Reserve Bank of Australia exchange rates could in 2021 be viewed on the Reserve Bank of Australia’s website (http://www.rba.gov.au).

26 The form of bankruptcy notice prescribed in Sch 1 to the Regulations is three pages long, the first page of which is in the form set out at [14] above.

27 Section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) is titled “Compliance with forms” and provides:

Where an Act prescribes a form, then strict compliance with the form is not required and substantial compliance is sufficient.

Formal defect or irregularity

28 Section 306 of the Bankruptcy Act concerns the effect of a formal defect or irregularity on a proceeding under the Bankruptcy Act. It relevantly provides:

(1) Proceedings under this Act are not invalidated by a formal defect or an irregularity, unless the court before which the objection on that ground is made is of opinion that substantial injustice has been caused by the defect or irregularity and that the injustice cannot be remedied by an order of that court.

29 It is well established that the issue of a bankruptcy notice is a “proceeding” under the Bankruptcy Act: Kleinwort Benson at 77 (Mason CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ).

30 The construction and operation of s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act was considered in Adams v Lambert. An earlier decision of an enlarged Full Court was overruled in Adams v Lambert: Australian Steel Co (Operations) Pty Ltd v Lewis (2000) 109 FCR 33 (Black CJ, Heerey, Sundberg JJ, Lee and Gyles JJ dissenting). Section 306 is predicated on the possibility of some failure to comply with a statutory requirement that produces a “formal defect or an irregularity”. In the event of such a failure, it must be asked whether the defect or irregularity is a formal defect or irregularity within the purview of s 306. If it is, then it is next necessary to consider whether substantial injustice has been caused by the defect or irregularity, and if so, whether the injustice cannot be remedied by an order of the court. These questions are separate and distinct with the latter only arising if the former is answered in the affirmative: see Adams v Lambert at [18].

31 As to what answers the requisite description of being “a formal defect or irregularity”, the High Court in Adams v Lambert made a number of observations at [25] to [34] in the context of overruling the decision of the Full Court in Lewis.

32 The following principles may be distilled:

(1) whether a particular defect or irregularity is a “formal defect or irregularity” is a question of statutory construction to be determined in the ordinary way having regard to the text of s 306, the relevant purpose(s) of the Bankruptcy Act and its context when read with other provisions;

(2) a defect or irregularity cannot be a formal defect or irregularity if it:

(a) fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Bankruptcy Act; or

(b) could reasonably mislead a debtor as to what is necessary to comply with the bankruptcy notice; and

(3) whether a requirement is made essential by the Bankruptcy Act is to be ascertained by a process of statutory construction of the relevant requirement. In this regard:

(a) the use of imperative terms such as “must” is not conclusive as to whether a requirement, especially as to form, is essential;

(b) questions which may be relevant, depending on the case, include:

(i) on the true construction of the Bankruptcy Act, having regard to legislative purpose and an evaluation of the significance or importance of the degree and/or kind of error or deficiency in the circumstances of the case, is the requirement which has been breached properly described as being essential; and

(ii) is it the purpose of the legislation that any slip with the breached requirement should invalidate the notice, particularly if the slip could not have misled the recipient of the notice as to what is required to comply with its requirements.

The decision in Gannaway

33 Given its relevance to the issues before the primary judge and on this appeal, it is convenient to summarise the decision in Gannaway. As mentioned, the respondent in the present appeal, Mr Coleman, was the applicant in Gannaway.

34 Mr Gannaway, the creditor and applicant for the bankruptcy notice, obtained judgment in the High Court of the Republic of Singapore against Mr Coleman for two amounts, one expressed in Singapore dollars (SGD) and the other expressed in US dollars (collectively, Singaporean Judgment). The Supreme Court of New South Wales registered the Singaporean Judgment in two parts: the first concerned that part expressed in SGD; and the second concerned that part expressed in US dollars.

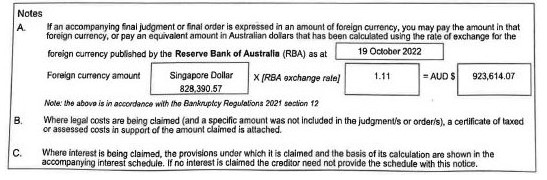

35 The bankruptcy notice issued at Mr Gannaway’s request, which was based on the registered judgment, sought payment of that part of the Singaporean Judgment expressed as SGD 825,000 and interest on that amount of SGD 3,390.57 making a total of SGD 828,390.57. Note A to the bankruptcy notice issued at Mr Gannaway’s request appeared as follows:

36 Mr Coleman applied to set aside the bankruptcy notice.

37 At [7] Jackman J observed in relation to the calculation included in Note A of the bankruptcy notice “that $828,390.57 x 1.11 does not equal $923,614.07. Rather, it equals $919,513.53”. At [12]-[13] his Honour said in relation to that calculation:

12 The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) published an exchange rate for AUD:SGD on 19 October 2022 to four decimal places, being 0.8969. It is common ground between the parties that the RBA did not publish an exchange rate of SGD:AUD. Mr David calculated the exchange rate for SGD:AUD by applying the inverse of 1AUD:0.8969SGD, which yields a figure of 1.11495, rounded down from 1.114951499609767 which is the quotient of 1 divided by 0.8969. Mr David’s evidence is that five decimal places was the maximum number of decimal places that the AFSA website allowed to be entered.

13 As indicated above, Mr David entered on the AFSA website the exchange rate of 1.11495, and the website then automatically converted the SGD828,390.57 into the AUD amount of $923,614.07. That arithmetic was correct. However, despite the multiplier actually used being 1.11495, when the Bankruptcy Notice was issued, the multiplier appeared as 1.11. That would appear to be the result of a flaw in the AFSA website, in that the website allowed Mr David to enter five decimal places, but the output of the entries made on the website only referred to the first two of those decimal places.

38 At [30] Jackman J held that the error in calculation in Note A was a non-compliance with reg 12(2)(b) of the Regulations. That was because the bankruptcy notice referred to the multiplier as 1.11 rather than the calculation which was performed using 1.11495 and therefore the stated product, AUD 923,614.07, was wrong as a matter of arithmetic, based on the figures in Note A. That was so despite the fact that it was the product of the calculation in fact performed. In his Honour’s view it followed that Note A to the bankruptcy notice did not set out the conversion calculation which was actually performed nor, as a result of the calculation expressed in Note A, the “equivalent” amount of Australian currency.

39 At [31] Jackman J considered whether the non-compliance with reg 12(2)(b) was a formal defect or irregularity for the purposes of s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act. In doing so at [32]-[33] his Honour referred to the decision in Parianos stating:

32 As Sackville J pointed out in Parianos v Lymlind Pty Ltd, above, at [13], that passage makes clear that a Bankruptcy Notice is a nullity if it fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Act, whether or not the notice could reasonably mislead a debtor. His Honour also said at [15] that there was no basis for drawing a distinction between a requirement made essential to the validity of a Bankruptcy Notice by the Act, and one rendered essential by a valid regulation made pursuant to the Act. Sackville J also held at [16] that the language of the then regulation strongly suggested that it was intended to create requirements essential to the validity of a Bankruptcy Notice, pointing out the emphatic language in which the regulation is expressed, including the repeated use of the word “must”.

33 I do not think that Parianos can be distinguished on the basis of the way in which the applicable regulation is now expressed. While the regulation which was the subject of Parianos provided that a Bankruptcy Notice must set out the applicable rate of exchange, whereas the current regulation leaves that as a matter to be dealt with in filling out Schedule 1 as prescribed by reg 9, which is itself expressly subject to s 25C of the Acts Interpretations Act 1901 (Cth), reg 12 as currently drafted maintains the use of the imperative and mandatory word “must”. It does so not merely in the context of prescribing a form, being the context which arose in Adams v Lambert, above, at [14] and [29]. On an ordinary and natural reading of reg 12(2)(b), the Bankruptcy Notice must include the conversion calculation for the equivalent amount of Australian currency, and in my view that imposes an essential requirement of the regulation.

40 Justice Jackman then considered reg 8 of the Regulations but found (at [34]) that it did not provide any support for the respondent’s position because: it was not clear on the evidence “whether the use of the [AFSA Online Portal] is the only such approved form”; whether or not that was the case, the problem that had emerged did not concern the requirement that the application must be in the approved form but was that the output of the approved form did not reflect what had actually been entered because it shortened the multiplier to 1.11; and accordingly there was no conflict to be resolved between reg 8(2) and reg 12(2)(b) of the Regulations. His Honour went on to observe that the problem was not a textual inconsistency but a factual issue arising from a defect in the AFSA Online Portal which, based on the evidence, may not be the only approved form, and concluded at [34] that:

If there were a conflict between the prescription of a form under reg 8(2) and the substantive requirements of reg 12(2)(b), then the latter would prevail, consistently with the reasoning in Adams v Lambert, above, at [14] and [29].

41 While it was not strictly necessary to do so, given the conclusion that reg 12(2)(b) of the Regulations imposed an essential requirement, Jackman J considered whether the conversion calculation included in Note A could have reasonably misled a debtor as to what was necessary to comply with the notice. His Honour concluded that it could, stating at [35] that:

A person who receives a Bankruptcy Notice containing an arithmetical error in one of the critical calculations going towards the figure which is stated to be required to be paid, could reasonably be in two minds as to what is required. One possibility is that the aggregate figure demanded is to be paid, irrespective of the arithmetical error inherent in its calculation. Another possibility is that the creditor would accept payment on the basis that clear arithmetical errors in the bankruptcy notice should be treated as having been corrected, and the correct figure would be accepted as meeting the demand. That is routinely the case in everyday commerce where invoices contain an arithmetical error.

The primary judge’s reasons

42 Before the primary judge Mr Coleman raised two grounds, only the second of which is relevant to this appeal. By that ground Mr Coleman alleged that the Bankruptcy Notice did not comply with regs 12(2)(a)(ii) and (b) of the Regulations.

43 The alleged non-compliance was in connection with two aspects of Note A on page 1 of the Bankruptcy Notice. In particular, the Bankruptcy Notice failed to comply with:

(1) reg 12(2)(a)(ii) because it did not contain a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as that term is defined by reg 12(3). That was because the Bankruptcy Notice refers to an exchange rate published by the RBA “as at 19 March 2023” which was a Sunday and was two calendar days, rather than business days, before the application for the Bankruptcy Notice was lodged. No RBA rate was published on 19 March 2023. The last day on which the RBA published a rate of exchange before 19 March 2023 was Friday, 17 March 2023 (date issue); and

(2) reg 12(2)(b) because the “conversion calculation”, which used “1.48” as the “RBA exchange rate” was not a calculation for “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined in that subsection (exchange rate issue).

44 The primary judge considered reg 12 of the Regulations in the context of the arguments put by Mr Coleman at PJ [45]-[46]:

45 As to the first argument, what is required by s 12(2)(a) is a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay either the amount of the judgment as expressed in foreign currency or the equivalent amount of Australian currency. A statement in those terms (without further elaboration of what “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” is) would meet the requirement. However, the text of Note A does not take that approach. It says that the debtor must pay either the foreign currency amount or “an equivalent amount in Australian dollars that has been calculated” in the manner that the Note sets out. If the product of that calculation is not “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined by s 12(3), it will follow that the Note fails to set out the alternatives identified by s 12(2)(a).

46 As to the second argument, what is required by s 12(2)(b) is a setting out of the conversion calculation “for the equivalent amount of Australian currency”. The calculation that is set out must be one that leads to “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined.

45 At PJ [47] his Honour observed that important to both arguments was whether the calculation in Note A of the Bankruptcy Notice aligned with reg 12(3) of the Regulations.

46 In relation to the date issue, the primary judge said at PJ [48]:

The first problem with the calculation set out in the notice is that it refers to an exchange rate published by the RBA “as at 19 March 2023”. That day was a Sunday and was two calendar days, rather than business days, before the application for the notice was made. The exchange rate that Mr Bennett, the respondent’s solicitor, actually used to make the calculation was that published by the RBA on Friday 17 March 2023, which was the correct rate for the purposes of s 12(3). However, because the incorrect date was inserted into the form, the notice failed to set out a calculation of “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” as defined by s 12(3).

47 The primary judge then considered the exchange rate issue. As his Honour explained (at PJ [49]) because the RBA does not publish rates for converting foreign currency into Australian dollars it is necessary, when calculating the Australian dollar equivalent of a judgment obtained in a foreign currency, to use the inverse of the published rate which is expressed to four decimal points. After referring to the discussion of the exchange rate issue in Gannaway at [39], the primary judge noted (at PJ [50]) that it was not necessary for him to express a concluded view as to how many decimal places should be used when undertaking the calculation to adopt a foreign currency exchange rate which is not expressly published by the RBA.

48 In resolving the exchange rate issue, at PJ [51]-[55] his Honour said:

51 In converting an amount expressed in US dollars into Australian dollars, it was necessary for Mr Bennett to find the relevant exchange rate published by the RBA and then multiply the relevant US dollar amount by the inverse of that rate. The published rate was 0.6714. Unimpeded by the demands of a prescribed form, a sensible person would simply divide the US dollar amount (186,471.25) by 0.6714, using their mobile phone or a pocket calculator, and obtain an answer of $277,734.96. However, the form used in the present case (which is the online form on the AFSA website) requires the foreign currency amount to be multiplied by the relevant exchange rate and therefore demands that the inverse of the RBA rate be set out in decimal form. That immediately introduces inaccuracy or confusion (or both), because expressing the inverse of the RBA rate in decimal form is highly likely to require rounding. The problem is exacerbated because the form only allows a figure with two decimal places to be inserted in the relevant space.

52 In Gannaway, the creditor’s solicitor derived a multiplier of 1.11495 from the published RBA rate, which he applied to the relevant foreign currency amount. His calculation was not criticised, and he had inserted the product of that calculation in the space provided for the “AUD” amount in Note A. However, being limited to two decimal places in expressing the relevant rate, he inserted “1.11” in that space. Jackman J said (at [30]):

In my opinion, the error in Note A in the Bankruptcy Notice constitutes a non-compliance with reg 12(2)(b), which requires that the bankruptcy notice “must” include “the conversion calculation for the equivalent amount of Australian currency”. The bankruptcy notice referred to the multiplier as being 1.11, rather than the calculation which was actually performed using 1.11495. Accordingly, the stated product AUD923,614.07 was wrong as a matter of arithmetic, based on the figures that were adopted in Note A, even though it was in fact the product which was produced by the calculation that was in fact performed. Accordingly, Note A did not set out the conversion calculation which was actually performed, and nor did it set out, as a result of the calculation expressed in Note A, the “equivalent” amount of Australian currency.

53 Mr Bennett, the respondent’s solicitor in the present case, was aware of what had been said in Gannaway and attempted to accommodate it. He calculated the inverse of 0.6714, to four decimal places, as 1.4894. With Gannaway in mind, he sought to avoid setting out a calculation that was wrong on its face, and therefore rounded the inverse figure to two decimal places before performing the calculation. If rounded in a conventional manner, the multiplier would be 1.49, which would overstate the amount due. He therefore rounded the multiplier down to 1.48, which produced an Australian dollar amount of $275,977.45. The calculation thus expressed is correct, but the answer understates “the equivalent in Australian currency” by (by my calculation) $1,757.51.

54 In Gannaway at [38] Jackman J expressed sympathy for the respondent, whose solicitor had diligently sought to comply with the statutory requirements. The same can be said here. Mr Bennett did the best that could be done, in the light of the reasoning in Gannaway, to comply with the requirements of s 12(2) while using the AFSA website. The evidence in Gannaway did not show whether AFSA’s online portal was the only means available to apply for a bankruptcy notice. Here, it is possible to infer from Mr Bennett’s affidavit that that is the case, and if necessary I would do so. However, the dictates of the website cannot override the requirements of s 12 or avoid the consequences of their breach.

55 Section 12(3) defines “the equivalent amount of Australian currency” in a way that means that, for any foreign currency amount on any given day, there is a single correct answer (at least if the RBA publishes an exchange rate for that currency). The “rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the Reserve Bank of Australia” means the rate published on the relevant day, expressed to however many decimal places the RBA expresses it. Dividing the relevant amount by that number (or multiplying by its inverse, which is the same thing) can as a matter of arithmetic produce only one answer, which is then to be rounded to the nearest cent. There is no scope for discretion or judgment in the process. Rounding the inverse of the published rate to two (or any particular number of) decimal places before doing the calculation produces, except in the exceedingly rare cases where the rounding makes no difference, an answer that is not “the equivalent amount of Australian currency”. The consequence, for reasons set out above, is that the notice in the present case did not comply with ss 12(2)(a) or (b).

49 Having reached that conclusion, the primary judge considered whether the non-compliance with reg 12 of the Regulations was a “formal defect or irregularity” for the purposes of s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act. His Honour said at PJ [57]-[59]:

57 The actual decision in [Kleinwort Benson]was that an understatement of the interest due on the judgment debt (by some $23,000) was a formal defect which attracted s 306(1). Because the notice was clear as to what had to be done to comply with it, it was not capable of misleading and therefore not a nullity (at 80–81). However it appears to have been a necessary step in this reasoning that interest on a judgment debt need not be included in a bankruptcy notice (see at 77), so that an accurate statement of the interest was not “a requirement made essential by the Act”.

58 The formulation in [Kleinwort Benson]at 79–80 was extended in Parianos v Lymlind Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 684; 93 FCR 191 (Parianos) at [15] (Sackville J) to a requirement “rendered essential by a valid regulation made pursuant to [the Act]”. The regulation in question in that case, held to have erected “essential” requirements (at [16]–[19]), was a predecessor of s 12. Jackman J accordingly regarded Parianos as indistinguishable in Gannaway, a conclusion with which I agree.

59 For my own part, I have some reservations concerning the reasoning in Parianos. Arguably, the regulation making power that sustains s 12 and sustained its predecessors is s 315(1)(a) (matters “required or permitted by this Act to be prescribed”), in combination with s 41(2) (which requires a notice to be “in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations”). There is something to be said for the view that non-compliance with a requirement as to the “form” of a bankruptcy notice constitutes a defect or irregularity that is “formal” (the term used in s 306(1)) and, consequently, should be regarded as invalidating a bankruptcy notice only if it leads to substantial injustice. That would have the potential to avoid the obvious injustice of invalidation of a bankruptcy notice in a case such as the present, where the Australian dollar amount sought by the notice is understated to the advantage of the debtor and what must be done in order to comply with the notice is tolerably clear. However, Parianos has stood as authority for more than 20 years and I do not think it can be said to be plainly wrong (cf, eg, N & M Martin Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2020] FCA 1186 at [43]–[46] (Steward J)).

50 The primary judge concluded (at PJ [60]) that because of the defects in compliance with reg 12(2) of the Regulations the Bankruptcy Notice was invalid.

Consideration

51 As set out above, the notice of appeal raises two principal questions: whether the primary judge erred in finding that the Bankruptcy Notice did not comply with reg 12 of the Regulations; and if the Bankruptcy Notice did not comply with reg 12, whether the primary judge erred in failing to find that the non-compliance was saved by s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act. We address each question below.

Did the Bankruptcy Notice fail to comply with reg 12 of the Regulations?

The date issue – ground 1

52 By ground 1 of the notice of appeal Mr Veale contends that the primary judge erred in his construction of reg 12(2)(a)(ii) and reg 12(3) of the Regulations in finding that the Bankruptcy Notice did not comply with the Regulations because the incorrect date was inserted into the application for the Bankruptcy Notice, despite the fact that the exchange rate used was the rate for the correct date and did not affect the correctness of the calculation.

53 Mr Veale submits that the insertion of the wrong date in the Bankruptcy Notice did not amount to a failure to comply with reg 12 of the Regulations because there is no requirement in reg 12 to include the exchange rate date in fact used to undertake the calculation. Regulation 12(2)(a) requires a bankruptcy notice to include a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay the amount of foreign currency or “the equivalent amount of foreign currency” which is defined in reg 12(3) as an amount which is worked out in the way specified in that subsection.

54 Mr Veale contends that, apart from using the prescribed form which includes Note A, all that is required by reg 12(2)(a)(ii) is that the amount in Australian currency be included, and that the amount be correct, as calculated in accordance with reg 12(3). Mr Veale says that in this case: the correct foreign exchange rate was used, i.e. the rate as at Friday, 17 March 2023, which was two business days before the application; and the total amount calculated using that rate was correct. Accordingly, there was no breach of reg 12(2)(a) of the Regulations.

55 Mr Veale also submits that there was no breach of reg 12(2)(b) of the Regulations because the conversion calculation was set out in accordance with the prescribed form and the date did not affect the correctness of the conversion calculation.

56 Regulation 12 of the Regulations (see [25] above) applies where a final judgment or order is expressed in foreign currency.

57 Regulation 12(2)(a) requires a bankruptcy notice to include a statement to the effect that the debtor must pay the amount of foreign currency (subreg (a)(i)) or the equivalent amount of Australian currency (subreg (a)(ii)). Regulation 12(2)(b) requires that a bankruptcy notice must include the conversion calculation for the equivalent amount of Australian currency.

58 Regulation 12(3) of the Regulations provides that for the purposes of reg 12(2)(a)(ii) the “equivalent amount of Australian currency” is “the amount worked out using the rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the [RBA] in relation to the day that is 2 business days before the day on which the application for the notice is made”. In contrast to the specific reference in reg 12(3) to use of the rate published on “the day” that is two business days before the day the application is made, Note A of the prescribed form provides for insertion of an “as at” date in respect of the rate used. The use in Note A of an “as at” date instead of the date “on” which the rate was in fact published may perhaps introduce an element of ambiguity. There is no such ambiguity in reg 12(3) itself. The requirement is clear that the rate to be used is that published on the day that was two business days before the application is made to AFSA.

59 The date that was two business days before the application for the Bankruptcy Notice was made was 17 March 2023. But for the purposes of the conversion calculation in Note A of the Bankruptcy Notice, the “as at” date was expressed to be “19 March 2023”. That gave rise to two issues: first 19 March 2023 was two days (as opposed to business days) before the application for the Bankruptcy Notice was made; and secondly, it was not the date on which the applicable rate was published. The currency conversion rate that was used was the rate published by the RBA on 17 March 2023. 19 March 2023 was not a date that had any bearing on any information required to be included in the Bankruptcy Notice by the Bankruptcy Act or the Regulations.

60 Contrary to Mr Veale’s submissions, reg 12(2)(a)(ii) of the Regulations must do more than simply set out the dollar amount for the equivalent amount of Australian currency. It must inform a recipient of a bankruptcy notice of the basis for the figures used in the conversion calculation which itself must be included in the notice by reason of reg 12(2)(b) of the Regulations. That is, the prescribed inclusion of the “equivalent amount of Australian currency” and the use of the related conversion calculation carried out in accordance with reg 12(3) of the Regulations must inform the recipient of the bankruptcy notice of the integers used to arrive at the equivalent amount of Australian currency. This includes the date for the rate of exchange in fact used. Put another way, as reg 12(3) requires the creditor to use “the rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the [RBA] in relation to the day that is 2 business days before the day on which the application for the notice is made”, the applicable date of conversion is to be disclosed in the bankruptcy notice for the purpose of properly informing the debtor of how the conversion amount was in fact calculated. The date on which the creditor applies to AFSA for the issue of a bankruptcy notice is not disclosed in the notice itself.

61 That construction of reg 12 is consistent with its purpose which includes identification of the means by which the equivalent amount of Australian currency has been calculated so that if a debtor choses to pay the debt claimed in Australian currency, he or she knows the amount to be paid and how it has been calculated: see Parianos at [19]. While Mr Veale submits that Parianos should not be followed, he does not challenge the identified purpose of the similar regulation in the 1996 Regulations.

62 It follows that ground 1 is not made out.

The exchange rate issue – grounds 2 and 3

63 By grounds 2 and 3 of the notice of appeal Mr Veale contends that the primary judge erred in his construction of reg 12(3) of the Regulations by finding that applying a foreign exchange multiplier rounded down to two decimal places does not comply with the requirements of reg 12(3) and, as a result, does not comply with regs 12(2)(a) or (b).

64 The primary judge’s reasoning in relation to the calculation included in Note A to the Bankruptcy Notice is set out at PJ [51]-[55] (see [48] above). As described by the primary judge, Mr Bennett rounded the rate he calculated and, in turn, applied to calculate the equivalent amount of Australian currency, to two decimal places and rounded the figure of 1.4894 rendered by his calculation down, rather than up as convention would dictate. Having taken these steps the calculation included in Note A of the Bankruptcy Notice was, as the primary judge observed, mathematically correct but it understated “the equivalent in Australian currency”, by his Honour’s calculation, by $1,757.51.

65 Mr Coleman submits that to draft a bankruptcy notice that is compliant with regs 12(2)(a) and (b) of the Regulations Mr Veale simply needed to convert the US dollar amount to Australian dollars using the exchange rate provided for by reg 12(3) being the “rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the [RBA] in relation to the date that is 2 business days before the day on which the application for the notice is made”.

66 Noting that it was common ground that two business days before the day on which the application for the Bankruptcy Notice was made was 17 March 2023 and on that day the RBA’s published rate for exchange of Australian dollars to US dollars was 0.6714, Mr Coleman submits that to convert from US dollars to Australian dollars Mr Veale needed to divide 1 by 0.6714 and round to 4 decimal places, the number of decimal places used in the rate published by the RBA, giving a rate of 1.4894. However, Mr Veale did not use this rate. He used an incorrect rate of 1.48. Thus Mr Coleman contends the Bankruptcy Notice did not correctly state the “equivalent amount of Australian currency” as required by regs 12(2)(a) and (b) of the Regulations and as the primary judge found at PJ [55].

67 Regulation 12 of the Regulations refers to “the rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the [RBA]”. The form of bankruptcy notice specified in Sch 1 to the Regulations envisages that the “RBA exchange rate” is multiplied by the foreign currency amount to obtain the relevant amount in Australian dollars. The Regulations therefore envisage that the equivalent amount of Australian currency is calculated by multiplying the foreign currency amount with a rate published by the RBA. However, as is apparent, the RBA does not publish rates for converting foreign currency into Australian dollars. Rather, it is necessary to calculate the rate to be included in the form of bankruptcy notice by dividing 1 by the rate published by the RBA as at the date which is two business days before the date of the application for the bankruptcy notice.

68 Mr Bennett undertook that process. Having done so he rounded the result to two decimal places, rounding down to 1.48, although the conventional method of rounding would have required him to round up to 1.49. Mr Bennett included the figure 1.48 in Note A to the Bankruptcy Notice and used that rate to calculate the equivalent amount of Australian currency. Note A set out the calculation which was in fact performed.

69 Mr Bennett rounded the result of his currency rate calculation to two decimal places for two related reasons: the decision in Gannaway; and the limitations of the form of bankruptcy notice.

70 As set out above, in Gannaway Jackman J found that the “equivalent amount of Australian currency” claimed in the bankruptcy notice in issue there was wrong as a matter of arithmetic based on the figures that were included in Note A. Accordingly, his Honour found that Note A did not set out the conversion calculation in fact performed: Gannaway at [30]. Mr Bennett, aware of the decision in Gannaway, calculated the equivalent amount of Australian currency by using and including in Note A to the Bankruptcy Notice a conversion rate rounded to two decimal places.

71 Mr Bennett’s evidence before the primary judge was that “the bankruptcy notice portal on the [AFSA Online Portal] only shows 2 decimal places on the bankruptcy notice” and that he “used 2 decimal places because this is the maximum number of decimal places which appears on a bankruptcy notice once it is published”. Mr Bennett explained that if he “entered a number with 4 decimal places into the [AFSA Online Portal], the calculation for currency conversion would have used 4 decimal places for the calculation, but the bankruptcy notice would appear to have only 2 decimal places, and there would be a difference between the rate appearing on the bankruptcy notice and the actual rate used”. Mr Bennett implicitly explained how the problem in Gannaway arose and expressly sought to avoid it in the case of the Bankruptcy Notice. Despite those efforts, the primary judge concluded that the Bankruptcy Notice did not comply with regs 12(2)(a) and (b) of the Regulations. However, for the reasons that follow we have reached a different conclusion.

72 First, contrary to Mr Coleman’s submission, there was evidence before the primary judge that the maximum number of decimal places displayed in a bankruptcy notice generated via the AFSA Online Portal was two (see [71] above). The primary judge was prepared to infer that the AFSA Online Portal was the only way to apply for the issue of a bankruptcy notice. By ground 1 of his notice of contention Mr Coleman challenges that inferential finding. He contends that there was no evidence that it was impossible to apply for a bankruptcy notice without using the AFSA Online Portal and that the primary judge should have refused to draw the inference sought by Mr Veale, consistent with the course taken in Gannaway at [14].

73 In his evidence relied on before the primary judge, Mr Bennett described in some detail the method by which he applied for issue of the Bankruptcy Notice. Taking Mr Bennett’s evidence as a whole and having regard to the scheme in the Bankruptcy Act for the issue of a bankruptcy notice the inference drawn by the primary judge was available. Mr Bennett was not required to give evidence as to what was not possible for the primary judge to draw the inference that he did.

74 Secondly, reg 12(3) of the Regulations assumes that the RBA publishes “the rate of exchange for the foreign currency” and the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice (see s 41 of the Bankruptcy Act, reg 9 and Sch 1 to the Regulations) requires the rate published by the RBA to be used as a multiplier to calculate the equivalent amount of Australian currency. But the RBA does not publish a rate in the form assumed by the Regulations or the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice. Unsurprisingly, it only publishes rates for converting Australian dollars into foreign currency. Thus, while reg 12(3) of the Regulations refers to “the rate” published by the RBA on the relevant day, there is no such rate.

75 The primary judge reasoned, by reference to reg 12(3) of the Regulations, that for any foreign currency amount on any given day there is a single correct answer and that the “rate of exchange for the foreign currency published by the [RBA]” means the rate published on the relevant day “expressed to however many decimal places the RBA expresses it”. His Honour considered that the relevant foreign currency amount should be divided by that number or multiplied by its inverse and the result of that calculation then rounded to the nearest cent. The rounding exercise should not occur before the calculation is carried out because, except in very rare cases, doing so will produce an answer that is not “the equivalent amount of Australian currency”: PJ [55].

76 Considering reg 12(3) of the Regulations in isolation, his Honour’s reasoning has some force. However, rounding is practically required by the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice. At the time the Bankruptcy Notice was issued, the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice permitted the inclusion in Note A of the applicable rate rounded to two decimal places. The rounding of the applicable exchange rate in Note A and its use as the multiplier for calculation of the equivalent amount of Australian currency was recognised in Gannaway.

77 The general principles relating to the interpretation of Acts of Parliament are equally applicable to the interpretation of subordinate legislation, such as the Regulations presently in issue: Collector of Customs v Agfa-Gevaert Ltd (1996) 186 CLR 389 at 398 (the Court) referring to King Gee Clothing Co Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1945) 71 CLR 184, 195 (Dixon J). The starting point for ascertaining the meaning of a statutory provision is the text, whilst at the same time regard is had to context and purpose. Context should be considered at the first stage and in its widest sense: SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 262 CLR 362 at [14] (Kiefel CJ, Nettle and Gordon JJ). As recognised in Australian Tea Tree Oil Research Institute v Industry Research & Development Board (2002) 124 FCR 316 at [37] (Stone J), in some cases, subordinate legislation may be construed with an eye to practical considerations to avoid an unreasonable result in favour of a reasonably practical one. This principle derives from Gill v Donald Humberstone & Co Ltd (1963) 1 WLR 929, 933-934 (Lord Reid, with whom Lords Evershed and Hodson agreed); see discussion in Herzfeld and Prince at [14.50]. This principle has been cited in many different contexts including in the context of construing the Bankruptcy Act and Regulations: GE Commercial Australasia Pty Ltd v Tinkler (2016) 247 FCR 257 (Gleeson J). Herzfeld and Prince observe that rather than being a different approach to the interpretation of subordinate legislation, this may also be understood as an application of the general approach to the interpretation of statutes that unreasonable results are to be avoided: Herzfeld and Prince at [14.50] citing Maritime Services Board of New South Wales v Posiden Navigation Inc [1982] 1 NSWLR 72, 86 (Yeldham J). See also Melbourne Pathology Pty Ltd v Minister for Human Services and Health (1996) 40 ALD 565, 580-581 (Sundberg J).

78 Section 41 of the Bankruptcy Act requires bankruptcy notices issued by the Official Receiver to be in accordance with the form prescribed by the Regulations and reg 8(2) of the Regulations requires that an application to the Official Receiver for the issue of a bankruptcy notice by a debtor who has obtained one or more judgments or final orders of a kind described in s 40(1)(g) of the Bankruptcy Act must be in the approved form. Regulation 9(1) of the Regulations provides that the form of bankruptcy notice set out in Sch 1 is prescribed for the purposes of s 41(2) of the Bankruptcy Act. At the relevant time, the bankruptcy notice in the prescribed form as issued by AFSA permitted the inclusion of a rate to be used for the conversion of foreign currency to Australian dollars rounded to two decimal places.

79 Regulation 12(3) of the Regulations is to be considered in context and interpreted subject to the limitations imposed by reg 9(1). To do otherwise introduces uncertainty which we apprehend the legislature did not intend and would make the ability to apply for the issue of a bankruptcy notice for a judgment in a foreign currency very difficult, if not impossible. Issues would regularly arise about the rate of exchange used for a conversion calculation and the rate of exchange included in a bankruptcy notice. In some cases, they may be different. Gannaway was such an example.

80 Contrary to Mr Coleman’s submission, this construction of reg 12 of the Regulations does not introduce a “near enough is good enough approach” nor does it render the drafter’s choice in reg 12(3) redundant. As required by reg 12(3) the rate of exchange published by the RBA must still be the starting point. It is that rate which is used to calculate the rate to be included in the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice. That is, 1 is divided by the rate published by the RBA on the given date, the result of that calculation is then rounded to the number of decimal places permitted on the face of the form of the bankruptcy notice as issued by AFSA to give the conversion rate. It is that rate which is applied for the purpose of calculating the equivalent amount of Australian currency. At the time Mr Bennett lodged the electronic form on behalf of Mr Veale the conversion rate published on the face of the bankruptcy notices issued by AFSA was limited to two decimal places. Although it was not necessary for the purpose of this appeal to admit the new evidence on which Mr Veale sought to rely, in the interest of providing some future guidance, we note that it appears that AFSA’s practice has changed since the events giving rise to this appeal and the conversion rate multiplier in Note A of bankruptcy notices now displays to 5 decimal places. If that had been the case in this appeal, then the rounding exercise required to result in substantial compliance would have required rounding to 5 decimal places.

81 The construction we have arrived at is supported by the evident purpose of reg 12 of the Regulations. That purpose is, as was the case with its predecessor, reg 4.04 of the 1996 Regulations, to: inform the debtor that he or she has an option to pay the judgment debt in the foreign currency or in a specified amount of Australian currency which is the equivalent of the foreign currency; and identify the precise means by which the specified amount of Australian currency was calculated and thus notify the debtor of the exact amount of Australian currency to be paid if the debtor exercises the option to pay in Australian dollars: see Parianos at [18]. As to the latter Sackville J said:

…The means chosen to identify the exchange rate recognises the obvious fact that exchange rates may vary, not merely from day to day, but from hour to hour or even by the minute or second. For this reason, a clearly identified and readily ascertainable rate of exchange is nominated for the purpose of undertaking the calculation required by reg 4.04.

82 The inclusion in Note A and use in calculating the equivalent amount of Australian currency of an exchange rate which is derived from the rate published by the RBA and rounded to the number of decimal places permitted by the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice identifies the precise means by which the specified amount of Australian currency was calculated. The debtor has a choice. He or she may pay that amount or may pay the judgment debt in the foreign currency amount. No doubt the debtor will choose the method which is most favourable to him or her recognising that exchange rates may vary “not merely from day to day, but from hour to hour or even by the minute or second”: see Parianos at [18].

83 This construction is also supported by the text of reg 12(3) when construed in accordance with its statutory context and purpose. Regulation 12(3) requires that the rate published by the RBA be “used” in working out the relevant AUD equivalent. The construction at which we have arrived requires that the relevant published RBA rate is used as the starting point in working out the AUD equivalent. To construe reg 12(3) in this way is consistent with the principles articulated at [77] and avoids an unreasonable result in favour of a reasonably practical one: cf PJ [55].

84 Grounds 2 and 3 are made out.

Substantial compliance – ground 4

85 In the alternative to ground 1, Mr Veale contends that the primary judge erred in relation to the date issue in failing to consider reg 9(3) of the Regulations and s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act and the interpretation of those sections in the context of s 41(2) of the Bankruptcy Act. He submits that those sections only required substantial, not strict, compliance with the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice.

86 Mr Veale submits that an anterior question to considering whether any failure to comply with the form of bankruptcy notice is a formal defect or irregularity for the purposes of s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act is whether the failure is a defect or irregularity at all, having regard to the substantial compliance test.

87 Mr Coleman submits that Mr Veale faces two fundamental problems in establishing this ground. First, he never alleged that the Bankruptcy Notice was defective because of non-compliance with reg 9. He alleged that the Bankruptcy Notice was defective because of non-compliance with reg 12. The requirements of reg 12 are not matters of form but govern how the debt is to be calculated in Australian currency and the information that is to be given to the debtor about that calculation (ie matters of substance), which is distinct from governing how that information is to be presented (ie matters of form). Accordingly, s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act does not arise in this case. Secondly, even if s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act is applied, it would not assist Mr Veale. If Mr Veale breached reg 12 by calculating the amount of Australian currency incorrectly and misrepresenting the date at which the chosen rate of exchange was prevailing, the Bankruptcy Notice did not substantially comply with the requirements of reg 12. He submits that the idea that a numerical amount or time could be described as “in substance” compliant with a requirement to include a different amount or time is a nonsense.

88 Farrugia v Farrugia (2009) 99 FCR 16 concerned an application to set aside a bankruptcy notice. Two categories of attack were made on the bankruptcy notice in that case, only the second of which is relevant to the question raised by this ground of appeal. That was the attack in relation to the form and content of the bankruptcy notice. In particular, there had been a failure to depict the statement “This Bankruptcy Notice is an important document. You should get legal advice if you are unsure of what to do after you have read it” in bold typeface. That statement appeared in regular typeface.

89 In resolving at what stage consideration should be given to the question of substantial compliance, Katz J said at [71]:

Finally, when there are differences between a bankruptcy notice and the form, but, despite those differences, the notice complies substantially with the form, then it cannot be said that that notice contains any potentially invalidating "defect" or "irregularity" within the meaning of s 306(1) of the Act, so that that provision is simply irrelevant in the circumstances. On the other hand, if the notice does not comply substantially with the form, then s 306(1) of the Act will be relevant.

90 At [72]-[73] Katz J referred to the decision in Meekin v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [1999] FCA 682 and observed that in Meekin Moore J made no reference to s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act, he inferred, “because he considered that provision to be irrelevant in the circumstances, he having held, in effect, that the bankruptcy notice which he was considering substantially complied with the form”. At [74]-[76] Katz J continued:

74 So far as I am able to tell, Moore J’s decision in Meekin is the only one in which the issue of the “format” of a bankruptcy notice, so far at least as concerns the typeface used in it, has arisen since the enactment of reg 4.02(2) of the Regulations. However, for the sake of completeness, I should refer to other decisions of single Judges of this Court in which reg 4.02(2) and (3) of the Regulations have been discussed in obiter.

75 Before Meekin, in Bank of Melbourne v Hannan (1997) 78 FCR 249, Northrop J set out the substance of reg 4.02(2) and (3) of the Regulations and then said (at 252): “Thus despite the use of the word ‘must’ in reg 4.02(2) strict compliance with Form 1 is not required.”

76 After Meekin, in Bendigo Bank Limited v Williams (1999) 168 ALR 175, Goldberg J, although without referring to Meekin, distinguished (at [15]) between the format of Form 1 of Sch 1 to the Regulations and its “content ... otherwise than in relation to its format” and concluded (at [16]) that, in relation to its format, strict compliance with Form 1 was not required.

91 At [78]-[79] his Honour concluded:

78 Since I adhere to the view that I should follow a decision of another single Judge of this Court unless satisfied that that decision was plainly wrong and since, further, although Moore J's approach in Meekin differs from the one which I have set out above, I am not satisfied that his decision was plainly wrong, I have decided that I should follow his decision in the present case. I am comforted in doing so by my belief that his approach and the one which I have set out above lead to the same result. That is that, where a bankruptcy notice differs from the prescribed form only in format, one asks oneself in the first instance whether those differences mean that the notice does not comply substantially with the form. If the answer to that question is in the negative, then the notice is not liable to be set aside on the ground of those differences.

79 In the circumstances, I intend to resolve the issue presently under consideration by first asking myself that question. Only if I conclude that the answer to that question is in the affirmative will I consider s 306(1) of the Act. …

92 In Fuller v Alford (2017) 252 FCR 168 Perry J considered whether, notwithstanding failure to include the level of the building specified in the address for service and payment in a bankruptcy notice, there was substantial compliance with the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice. At [81]-[82] her Honour said:

81 Section 41(2) of the Act provides that “[t]he [bankruptcy] notice must be in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations”, and not that the notice must be “in” the prescribed form. As such, s 41(2) “lays down a requirement of substantial, rather than strict compliance” with the prescribed form in terms of format or layout, as well as content: Farrugia v Farrugia (2000) 99 FCR 16 at [64] and [67] (Katz J).

82 Regulation 4.02(1) prescribes Form 1 as the bankruptcy notice for the purposes of s 41(2) of the Act. While reg 4.02(2) provides a bankruptcy notice must follow Form 1 in respect of its format, reg 4.02(3) provides that subreg (2) is not to be taken as expressing an intention contrary to s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth). Accordingly reg 4.02, does not exclude s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act, reinforcing that strict compliance with the form prescribed is not required and substantial compliance is sufficient in line with s 41(2) of the Bankruptcy Act: see the note to subreg (3) and Australian Steel Company (Operations) Pty Ltd v Lewis (2000) 109 FCR 33 (Lewis) at [88] (Lee J (whose approach in dissent was upheld in Adams)).

93 As is apparent, strict compliance with the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice is not required. Substantial compliance is sufficient. In our view for the reasons that follow the Bankruptcy Notice substantially complies with the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice despite the misdescription of the date for the applicable conversion rate.

94 First, reg 12 requires a bankruptcy notice to include a statement that the debtor must pay the amount of foreign currency or the equivalent amount of Australian currency, the conversion calculation for the latter and a statement that the conversion calculation was carried out in accordance with the requirements of reg 12. The inclusion of the date for the exchange rate applied in undertaking the conversion calculation is not a requirement of reg 12. It is a requirement of the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice.

95 Secondly, in any event, the Bankruptcy Notice met the requirements of reg 12 insofar as it included:

(1) a statement to the effect that Mr Coleman must pay the judgment debt in US dollars or the equivalent Australian dollar amount;

(2) the conversion calculation for the equivalent Australian dollar amount; and

(3) a statement that the conversion calculation was made in accordance with reg 12.

96 Thirdly, the non-compliance with the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice was not by way of omission of a fact such as the failure to include a complete address for payment of the amount claimed in the notice. A date for the conversion rate was included but it was incorrect. It was not the date that was two business days before the application for the Bankruptcy Notice was made and was not the date used by Mr Veale to undertake the prescribed calculation. However, the inclusion of the wrong date did not affect the correctness of the figures used in the calculation, the calculation of the equivalent amount of Australian currency or the final amount in the Bankruptcy Notice. Those matters were all correctly stated.

97 Ground 4 is made out.

Is the Bankruptcy Notice saved by s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act?

98 In the event that we are wrong in our conclusion that there was substantial compliance with the prescribed form of bankruptcy notice, we consider grounds 5 to 10 of the notice of appeal. They concern the primary judge’s finding that the non-compliance as found by his Honour was not a formal defect or irregularity within the meaning of s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act. While expressing some doubt, the primary judge followed Parianos and thus found that reg 12 of the Regulations provided for “essential” requirements in a bankruptcy notice. His Honour agreed with the conclusion reached in Gannaway at [32]-[33] that Parianos was indistinguishable and, although expressing some reservations about the reasoning, did not think that Parianos could be said to be plainly wrong.

99 Mr Veale alleges that the primary judge erred in finding that any non-compliance was not a formal defect or irregularity within the meaning of s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act (ground 5, notice of appeal) and in a number of other specified ways (see below) in applying the relevant principles to the facts of this case.

100 Before turning to consider the questions raised, it is convenient to set out a summary of principal authorities which have considered s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act and of Parianos.

The relevant authorities

101 We commence with Kleinwort Benson. In that case the creditor, Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd, served bankruptcy notices in identical terms on three debtors claiming in each $1,399,085.81 plus interest at the rate of 19.5% per annum from 3 July 1986 which, as at 30 September 1986, was calculated to be $43,352.49. The bankruptcy notices claimed a total of $1,442,438.30 as due by the debtors to Kleinwort Benson “under a final judgment obtained by it against you in the Supreme Court of New South Wales”. In fact the bankruptcy notices understated the amount of interest due as at 30 September 1986 by approximately $23,000. The debtors challenged the validity of the bankruptcy notices on the basis of that understatement.

102 A majority of the High Court (Mason CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ) noted (at 76-77) that s 41 of the Bankruptcy Act sets out the essential requirements of a bankruptcy notice and that misstatement of the amount due to a creditor is not necessarily fatal to its validity, referring to subs 41(5) and (6) which concern overstatement of the amount due. The majority also noted (at 77) that no specific provision is made in relation to understatement of a debt but referred to s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act. Their Honours identified three questions that arose in relation to the validity of the bankruptcy notices in issue: were they defective or irregular; if so, was the defect or irregularity substantive or formal; and if formal only, had the defect occasioned substantial and irremediable injustice.

103 As to the first of those questions, were the bankruptcy notices defective or irregular, the majority accepted that a bankruptcy notice which misstates the amount due to the creditor is defective or irregular: at 77. On the question of interest, the majority noted that interest may, but need not be, included in a bankruptcy notice but, if included, it must be calculated: at 77-78. Their Honours continued (at 78):