Federal Court of Australia

Seven Network (Operations) Limited v 7-Eleven Inc [2024] FCAFC 65

ORDERS

SEVEN NETWORK (OPERATIONS) LIMITED Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of this order the parties must file a minute of consent orders, or competing minutes if necessary:

(a) proposing orders to determine the appeal (save in relation to the costs of the appeal and of the proceeding below); and

(b) programming written submissions in relation to the costs of the appeal and of the proceeding below.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[9] | |

[15] | |

[27] | |

[29] | |

[33] | |

[39] | |

3.5 The discretion for the mark not to be removed from the Register | [40] |

[56] | |

[61] | |

[76] | |

[76] | |

[76] | |

[79] | |

6.2 Category 2 - the promotion and sale of goods and services for others (grounds 7 and 8) | [95] |

[95] | |

[99] | |

6.3 Categories 3 and 4 - retail and wholesale services, and the bringing together of a variety of goods (grounds 9 and 10) | [109] |

[109] | |

[110] | |

7 THE EXERCISE OF DISCRETION (Ground 11, Notice of Contention) | [117] |

[117] | |

[119] | |

[124] | |

[128] | |

[129] | |

[144] | |

[145] | |

7.4.4 Fragmentation of ownership between the Defended and the Undefended Goods and Services | [149] |

[152] | |

[155] | |

[160] | |

[172] | |

THE COURT:

1 This application for leave to appeal and appeal concerns the validity of registered trade mark no. 1540574 for the word 7NOW (7NOW mark) in the context of the non-use provisions in Part 9 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). The 7NOW mark is registered in classes 9, 35, 38 and 41 of the Trade Marks Register and has a filing date of 13 February 2013. It is owned by the present applicant, Seven Network (Operations) Limited.

2 The contest concerns the limited question of whether the goods and services underlined below, in respect of which the 7NOW mark has been registered, should be removed from the Register for non-use:

Class 35: Advertising including advertising services provided by television and in the nature of dissemination of advertising for others via online global electronic communication networks; rental of advertising space including online; promotional services; the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests; retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet; the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels; television commercials and production of television commercials; including the provision of all the aforesaid services via broadcasts, television, radio, cable, direct satellite, electronic communication networks, computer networks, global computer network related telecommunication and communication services, broadband access services, wireless application protocol, text message services, telephone and cellular telephone; information and advisory services relating to all the aforementioned

Class 38: Broadcasting services, including television broadcasting, interactive broadcasting services, broadcasting of electronic programming guides, free-to-air and subscription television broadcasting services and radio broadcasting services; datacasting; telecommunications and communication services, including interactive telecommunications and communication services; transmission of cable television and interactive audio and video services; personalised and interactive television transmission and programming services; streaming of audio and video material on the Internet; information and advisory services relating to all the aforementioned

Class 41: Entertainment services including those provided by, or in relation to, television, television broadcasting, television programmes and interactive television programmes, sporting events; pay and subscription television services in this class; entertainment services in the nature of producing, distributing and disseminating programs and information; online television entertainment and information services including digital recording of television programs for delayed, interactive and personalised viewing; online provision of television program listings and suggested viewing guides; personalised and interactive entertainment services in the nature of providing personalised television programming and interactive television programming and games; production of films, shows and television programs including interactive programs; news and news reporter services; providing on-line electronic publications; providing digital music, videos and television clips online; including the provision of all the aforesaid services via broadcasts, television, radio, cable, direct satellite and electronic communication networks, including computer networks, global computer network related telecommunication and communication services, broadband access services, wireless application protocol, text message services, telephones and cellular telephones; information and advisory services relating to all the aforementioned

3 The underlined portions above were defined by the primary judge as the Defended Goods and Services and the balance of the goods and services were defined as the Undefended Goods and Services. The Court adopts those definitions here.

4 In July 2019, the respondent, 7-Eleven Inc, filed an application under s 92(1) of the Trade Marks Act to remove the 7NOW mark on the ground mentioned in s 92(4)(b), namely that Seven had not used the 7NOW mark during the three years between 10 June 2016 and 10 June 2019 (non-use period). A delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks held that the 7NOW mark should be removed in its entirety from the Register, not being satisfied that Seven had used the 7NOW mark during the non-use period in relation to any of the above goods and services, and declining to exercise the discretion in s 101(3) of the Trade Marks Act not to remove the mark: Seven Network (Operations) Limited v 7-Eleven Inc [2021] ATMO 58; (2021) 164 IPR 370.

5 Seven appealed from the decision of the delegate pursuant to s 104 of the Trade Marks Act. The primary judge allowed the appeal in part by consent in relation to the Undefended Goods and Services and dismissed it insofar as Seven sought to secure registration in respect of the Defended Goods and Services; Seven Network (Operations) Limited v 7-Eleven Inc [2023] FCA 608. Hence the dispute before us concerns only the Defended Goods and Services.

6 On 14 June 2023, the primary judge made orders for the specification for the 7NOW mark to be amended to remove the Defended Goods and Services. Seven now seeks leave to appeal from that part of the decision. Leave to appeal from a decision made under s 104 is required pursuant to s 195(2) of the Trade Marks Act. The orders of the primary judge removing the Defended Goods and Services from the Register have been stayed, pending the outcome of this application for leave and any appeal.

7 By way of background it may be noted that on 23 March 2020, 7-Eleven filed trade mark application nos. 2077255 and. 2077257 for the word mark 7NOW and the composite mark  respectively in relation to services in class 35 being: 'retail convenience stores; online retail convenience store services for a wide variety of consumer goods featuring home delivery service and in-store pickup'. 7-Eleven uses the mark overseas in relation to a food and alcohol delivery and pick-up service, including via a '7NOW App'. It proposes to offer a similarly branded service in Australia if it succeeds in its application for registration.

respectively in relation to services in class 35 being: 'retail convenience stores; online retail convenience store services for a wide variety of consumer goods featuring home delivery service and in-store pickup'. 7-Eleven uses the mark overseas in relation to a food and alcohol delivery and pick-up service, including via a '7NOW App'. It proposes to offer a similarly branded service in Australia if it succeeds in its application for registration.

8 For the reasons given below, we consider that Seven has demonstrated use of the trade mark during the non-use period, but only in relation to the promotion of goods for others in Category 2 (as defined below). As a result, we would grant leave to appeal and would allow the appeal in part. That being so, we re-exercise the s 101(3) discretion, but not in Seven's favour. As a consequence, the outcome is that the mark should be removed from the Register in respect of Categories 1, 3 and 4 of the Defended Goods and Services and in respect of Category 2 in relation to the sale of goods and services for others.

9 Leave to appeal is required by s 195(2) of the Trade Marks Act. Seven's application for leave is accompanied by affidavits affirmed by Rebekah Gay, the principal lawyer having conduct of the leave applications on behalf of Seven.

10 The test for the granting of leave to appeal involves a two-stage enquiry: (a) whether, in all the circumstances, the decision below is attended with sufficient doubt to warrant it being reconsidered by a Full Court; and (b) whether substantial injustice would result if leave were refused, supposing the decision to be wrong. The two enquiries bear upon each other: Decor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc [1991] FCA 655; (1991) 33 FCR 397 at 398-399.

11 Seven submitted that substantial injustice would result if leave to appeal were refused, supposing the decision of the primary judge to be wrong. Seven particularly emphasised that if the 7NOW mark were to be removed from the Register in relation to the Defended Goods and Services, that would irrevocably extinguish Seven's rights. It also submitted that if the primary judge's orders stand, that is likely to lead to the mark being split between two different traders in relation to similar goods and services, which is likely to confuse consumers and so undermine the integrity of the Register.

12 This case concerns draft grounds of appeal that contend that the primary judge erred in making evaluative findings as to whether or not a standalone website created for 7NOW that displayed its own content, defined as the 7NOW website, involved the use of the 7NOW mark in the requisite sense. In the present case the question of the grant of leave to appeal is closely tied to the substantive question of the likely prospects of the appeal.

13 In RB (Hygiene Home) Australia Pty Ltd v Henkel Australia Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 10 at [12] the Full Court (Nicholas, Burley and Hespe JJ) noted that where evaluative findings are made on the basis of facts not in dispute (as is the case here), the appellate court stands in the same position as the trial court in its ability to draw the inference. However, before it embarks on that process, the appellate court must be satisfied that an error has occurred: see Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 at [47]-[48] (Perram J, Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreeing). In deciding the proper inference to be drawn, the appellate court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the trial judge, but once it has reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it: Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 551. As Perram J explained in Aldi Foods at [49] (emphasis in original):

What kinds of case lie in this indeterminate area? Warren v Coombes provides part of the answer: the drawing of inferences from facts already found. But there are other examples, too: does certain packaging convey a representation; is a word capable of distinguishing one trader's goods from another? There are also some legal standards which are so amorphous in nature that it will be difficult to say with any certainty whether a given fact lies within or without the standard. Examples will include concepts such as unconscionability and oppressive conduct. Whilst the question of whether a given set of facts could fall within such a standard is a question of law (Vetter v Lake Macquarie City Council [2001] HCA 12; 202 CLR 439 at 450 [24]) the question of whether a particular set of facts does do so is a question of fact. It is for that reason that such questions are sometimes referred to as, perhaps confusingly, mixed questions of fact and law. Each of these kinds of standard involves an element of evaluation (just as the drawing of an inference does). When an appellate court comes to review such conclusions it must be guided not by whether it disagrees with the finding (which would be decisive were a question of law involved) but by whether it detects error in the finding. On the one hand, error may appear syllogistically where it is apparent that the conclusion which has been reached has involved some false step; for example, where some relevant matter has been overlooked or some extraneous consideration taken into account which ought not to have been. But error, on the other hand, may also appear without any such explicitly erroneous reasoning. The result may be such as simply to bespeak error. Allsop J said in such cases an error may be manifest where the appellate court has a sufficiently clear difference of opinion: Branir at 437-438 [29].

14 In the view we have taken, as set out below, the primary judge's decision was, with respect, attended by error in relation to Category 2. It would cause injustice to Seven if that aspect of the decision were enabled to stand. In addition, as explained further below, that conclusion necessitates that this Court re-exercise the discretion under s 101(3) in relation to the other three categories of goods and services and the remaining part of the Category 2 services, although in the result we consider that none of those categories should remain on the Register. For all those reasons, leave to appeal will be granted and the appeal allowed in part.

15 Seven obtained registration of the 7NOW mark on 7 August 2013. The primary judge divided the Defended Goods and Services by reference to the following categories ([21]):

Category 1: computer software (in class 9);

Category 2: the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of online promotional material and promotional contests (in class 35);

Category 3: retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet (in class 35); and

Category 4: the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels (in class 35).

16 The primary judge summarised the issues before him as being whether Seven had discharged its onus of proving that it had used the 7NOW mark in respect of the Defended Goods and Services during the non-use period and, if not, whether the Court should exercise the discretion under s 101 of the Trade Marks Act to remove the mark in relation to those goods and services.

17 His Honour then noted that the use claimed may be defined by reference to two different uses. The first was from 24 July 2018 to 1 April 2019 during which persons entering the URL 7now.com.au were redirected to a 7plus.com.au domain. However, this use is not relied upon on appeal and need not be mentioned further.

18 The second period of use was from 1 April 2019 until 10 June 2019 (the latter date being the end of the non-use period) during which those who used the 7now.com.au domain landed on the 7NOW website. That website is still operating. Seven relies on its use of the word 7NOW on the 7NOW website during the period from 1 April 2019 to 10 June 2019 in its application for leave to appeal and any appeal (the 7NOW website period).

19 The primary judge found that during the 7NOW website period, the user traffic to the website totalled 157. The first occasion on which there was any traffic was 16 May 2019, when eight users visited the site. Traffic on the website during that period peaked on 8 June 2019 with 11 users. The evidence did not indicate whether the majority of traffic was generated by Seven itself, for example, staff checking the content of the website. 7-Eleven made a submission in passing that there was no finding that any visitors were Australian, and that this was an evidentiary hole that precluded any finding of trade mark use. But that submission was neither put to the primary judge nor determined by him, and nor was it the subject of a notice of contention. 7-Eleven cannot rely on it now.

20 The primary judge found that the 7NOW website promotes television content that is available to users through Seven's online platforms and allows users to access that content directly from the 7NOW website. Specifically, at the time of its launch on 1 April 2019, the 7NOW website promoted and provided links to various websites, including the 7plus website; online streaming portals for Seven's channels (7, 7MATE, 7TWO and 7FLIX); the website for Seven's news service, 7NEWS; and the web pages (within the 7plus website) of some of Seven's most popular television programs, such as Home and Away, House Rules, My Kitchen Rules, Sunrise, Sunday Night, Andrew Denton's Interview, and The Morning Show.

21 The primary judge accepted that, during the 7NOW website period, the following banner (the 7NOW banner) was featured across the top of the 7NOW web page:

22 He also accepted that the content of the 7NOW website, which could be viewed in full by scrolling down, was represented in the two screenshots set out below, noting that the red crossings-out of five of the tiles and two lines of writing on the bottom of the second screenshot represent those which were not included in the version used from 2 April 2019. Nothing in the present appeal turns on those excisions:

23 Each of the graphic squares is a tile on which a user could click to be taken to a different website.

24 A composite depiction of the web page that comprises the 7NOW website, based on the above images, appeared as an annexure to Seven's outline of written submissions on the appeal, and 7-Eleven also relied on it. That annexure is annexed to these reasons.

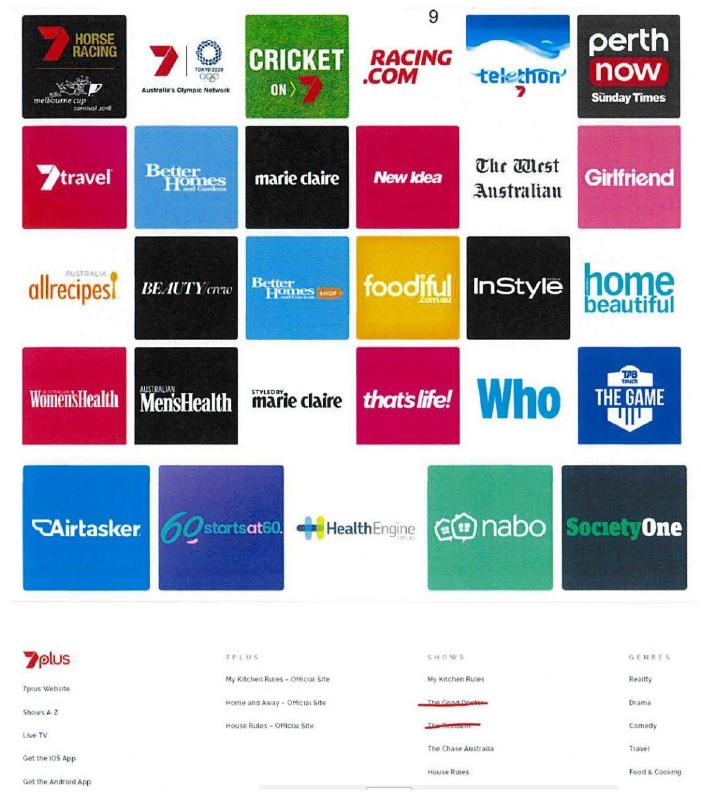

25 It is convenient to note at this stage that the 7NOW website includes 48 tiles (excluding those removed on 2 April 2019) which may be clicked on to be redirected to other websites. At the end of the page are four columns containing small and poorly readable writing. For ease of reference, the columns contained the following content from 2 April 2019:

7PLUS | 7PLUS | SHOWS | GENRES |

7plus Website | My Kitchen Rules- Official Site | My Kitchen Rules | Reality |

Shows A-Z | Home and Away - Official Site | Drama | |

Live TV | House Rules - Official Site | Comedy | |

Get the iOS App | The Chase Australia | Travel | |

Get the Android App | House Rules | Food & Cooking |

26 The primary judge addressed the non-use allegations by reference to the four categories of Defended Goods and Services that he had identified.

27 In relation to the 7NOW website period, the primary judge first addressed Category 1 of the Defended Goods and Services, being 'computer software'. His Honour found that, taking the whole context into account, the viewer of the 7NOW website would see the banner at the top of the page and understand that it was on a website, the address of which included '7now'. The viewer would see the various tiles on the website and would not fail to notice that many of them were associated with Seven.

[96] At the bottom of the page, after the tiles, the viewer would see the 7PLUS mark in the following part of the screen:

…

[97] The viewer would see a number of links provided under the 7PLUS mark in the first column: first, to the '7plus Website', then to 'Shows A-Z', then to 'Live TV' then to the 'Get iOS App' and 'Get the Android App'. The viewer would understand that there was a '7plus Website', at which one was likely to be able to access 7PLUS's 'Shows A-Z' and 'Live TV'. The viewer would understand that there was an iOS and Android App associated with 7PLUS which was likely to facilitate access to these things.

[98] The viewer would see the various links provided in the other columns. Thus, in the second column, under the heading '7PLUS', the viewer would see links to the official websites of 'My Kitchen Rules', 'Home and Away' and 'House Rules' and consider that these were offerings of 7PLUS. The viewer would understand the matters at the bottom of the screen as being trade offerings of 7PLUS.

[99] The viewer would not also consider that the 7NOW Mark was being used to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the 7PLUS App and 7NOW. Of course, although the submissions tended to overlook this, the words '7PLUS App' do not appear at all on the 7NOW website. Rather, there is a reference to getting an app under the 7PLUS logo in the first column. I accept that the typical consumer would think that there was a commercial connection between the businesses of 7NOW and 7PLUS, but the typical consumer would: (a) presume the businesses to be separate and distinct; and (b) not understand that the 7NOW Mark was being used to distinguish the 7PLUS App (which is not directly named on the page) as an offering of 7NOW or as being co-offered by 7NOW together with 7PLUS. Nor would the consumer understand that the 7NOW Mark was being used to indicate the origin of the service of the supply of the 7PLUS App as opposed to the origin of the 7PLUS App itself.

[100] It follows that I do not consider that there was use as a trade mark in relation to this category.

29 Category 2 services are for 'the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of online promotional material and promotional contests'.

30 Seven submitted before the primary judge that the 7NOW website promotes and advertises other publications and businesses in which Seven West Media Limited (the ultimate holding company of the Seven Group) holds a commercial interest, being businesses which are nevertheless independent from Seven. Examples Seven gave were the publications The West Australian and Perth Now and the websites 60 Starts at 60, Society One and HealthEngine. Seven submitted that the advertising of these other businesses on the 7NOW website was within Category 2. 7-Eleven submitted in response that whilst Seven may be providing a promotional service to those businesses, no evidence was adduced as to how that service is offered and that it was not sensible to describe a visitor to the 7NOW website as being provided with a promotional service within Category 2.

31 In considering this category, the primary judge observed that a viewer who clicked on the tiles '60 Starts at 60', 'Society One', 'HealthEngine' or 'AirTasker' would be taken to the respective websites operated by each of those businesses. Each of those websites contained material which promoted the various goods and services of the businesses and allowed purchases of various goods and services. However, a typical viewer of the 7NOW website would not understand that the 7NOW mark was being used in the promotion of any of those goods or services. Rather, they would understand that the 7NOW website contained links to various businesses, many associated with Seven, in particular, those with the number '7'.

32 The primary judge continued:

[109] The present case is different to the position of an obviously unrelated entity including advertisements, such as a newspaper providing advertisements for goods and services of third parties. It is different because, at least in relation to most tiles, a commercial affiliation is likely to be inferred. Nevertheless, the typical viewer would not consider that the 7NOW Mark was used to indicate a trading connection between 7NOW and the goods and services offered by those other businesses.

[110] Further, the typical viewer would not consider on the basis of what the consumer observed on the website that 7NOW was engaged in the business of 'the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests'. Promotional and advertising services are services in which one party promotes or advertises the goods or services of another party. The consumer is not the recipient of promotional or advertising services. The typical consumer would assume that 7NOW was affiliated in some way with other Seven entities and that Seven was promoting its own business interests. This is not and would not have been understood as 7NOW being engaged in promotional or advertising activities.

33 Categories 3 and 4 services are, respectively, 'retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet' and 'the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels'.

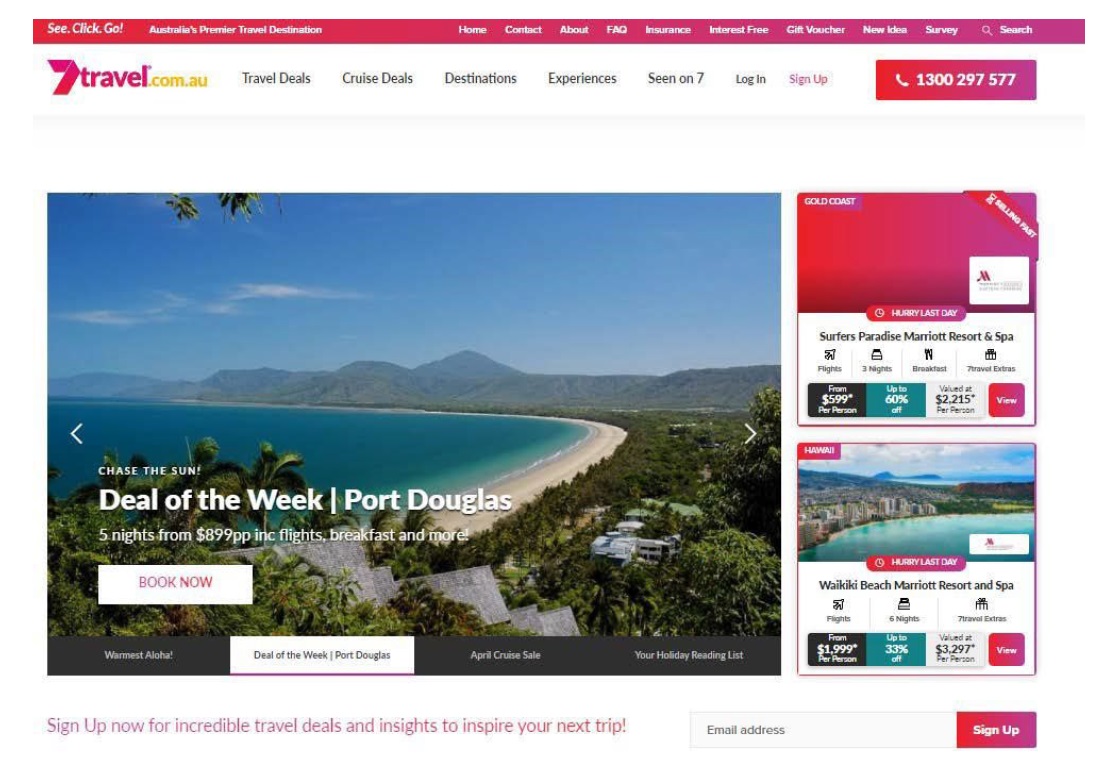

34 The primary judge noted that the tiles for '7travel' and 'Better Homes and Gardens' clicked through to websites through which the user could acquire goods and services. The '7travel' tile took the user to the 7travel website at the URL www.7travel.com.au, a website his Honour described as an e-commerce platform that offered consumers a range of travel products supplied by companies with which Seven had entered into marketing partnerships. A screenshot reproduced in the primary judgment promoted a package holiday in Port Douglas with a 'BOOK NOW' button as follows:

35 Similarly, the 'Better Homes and Gardens' tile took the user to the Better Homes and Gardens Shop website at the URL www.bghshop.com.au, on which, it appears from a screenshot, the user could shop for various homewares, gardening and art supplies:

36 While the screenshots for these sites were taken outside the 7NOW website period, the primary judge appeared to accept that they were relevant to that period.

37 The primary judge noted that there was also a tile on the 7NOW website linking to a page within the 7plus website at which the user could view Seven's The Morning Show. That programme included product promotion segments or 'advertorials' which called on the viewer to telephone a number or visit a website to order a product. The products appear to have been all products of third parties, such as the Cancer Council or Sony Music.

38 In relation to the Categories 3 and 4 services, the primary judge held at [118]:

The services offered on the linked e-commerce platforms were not offered on the 7NOW website and the typical consumer would not have understood those services as being offered by reference to the 7NOW Mark. The 7NOW Mark was not used on the 7TRAVEL website or the Better Homes and Gardens Shop website. The connection or association must therefore derive from the use of the 7NOW Mark on the website which contains the relevant link. The typical consumer would not have understood the services offered on the websites to which they navigated from the 7NOW website as being services relevantly connected with and provided by 7NOW as opposed to services offered by businesses with some affiliation with 7NOW.

3.4 Conclusion as to trade mark use

39 The primary judge concluded at [119] that the 7NOW mark had not been used as a trade mark in relation to any of Categories 1, 2, 3 or 4 during the non-use period.

3.5 The discretion for the mark not to be removed from the Register

40 The primary judge then turned to the exercise of discretion under s 101(3) of the Trade Marks Act. There is no dispute on appeal as to the principles to be applied in the exercise of the discretion, or that the primary judge correctly referred to PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 128; (2021) 285 FCR 598 at [153] as setting out the principles applicable.

41 His Honour noted that Seven had submitted that there were several reasons why the discretion should be exercised to allow the 7NOW mark to remain on the Register.

42 The first was that Seven had been using the 7NOW mark in relation to the Defended Goods and Services after the end of the non-use period, and in relation to goods and services which were similar or closely related to the Defended Goods and Services. The primary judge rejected that submission.

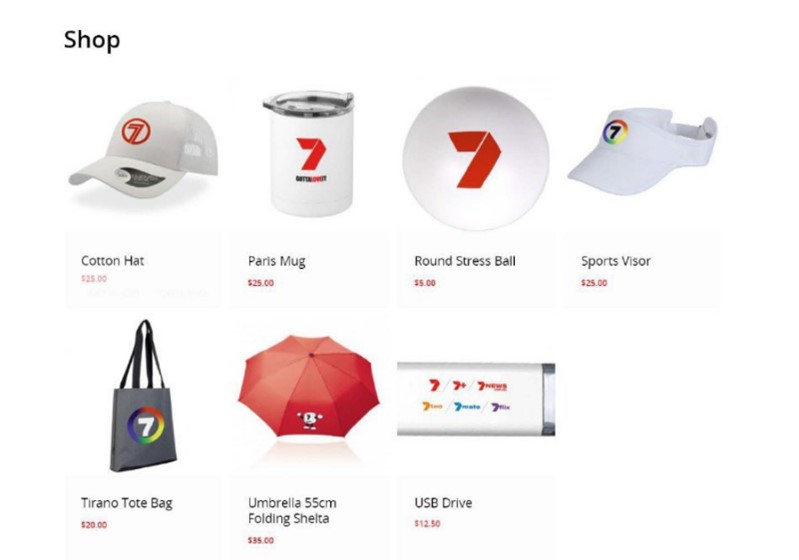

43 Seven relied on the fact that in August 2021 it had launched an 'online retailing outlet' in the form of a merchandise store operating through a third-party platform, Liquid Promotions, available at seven.liquidpromotions.com.au. After this online store was launched, the 7NOW website was updated to include a '7Merch' tile. The primary judge found that by clicking on the '7Merch' tile, the user was directed to the store at seven.liquidpromotions.com.au, which sells merchandise, including the following:

44 The primary judge found (and it is not challenged on appeal) that nowhere is the 7NOW mark depicted on any of the merchandise sold. His Honour also noted that the USB drive depicted contains firmware, which is a type of software (a point relevant to Category 1). The various uses of the combination of the number '7' with a word or symbol are referred to in the primary judgment as the 7-formative marks and include 7+, 7NEWS.com.au, 7MATE, 7FLIX and 7TWO as set out on the USB drive. They also include 7BRAVO, 7FOOD NETWORK and 7PLUS.

45 The primary judge considered (at [131]) that this use after the non-use period did not involve use of 7NOW as a trade mark, for the same reasons articulated in relation to each of the categories during the non-use period. His Honour reached the same conclusion regarding the '7Merch' tile. By clicking on this tile, the user was taken to a retail store operated through a third-party platform, Liquid Promotions, which sells merchandise bearing the marks CHANNEL 7 and 7. There was no apparent connection between the domain name liquidpromotions.com.au, or the content of the web page on which a user lands, and 7NOW. A consumer purchasing goods through this platform would understand those goods to be sold by Liquid Promotions.

46 The primary judge also noted that beyond contending that it had used the 7NOW mark during the non-use period, Seven had not sought to explain any non-use.

47 The second argument advanced by Seven was that the removal of the 7NOW mark would 'seriously prejudice Seven's private interests' because the 7NOW mark was part of Seven's 'significant portfolio of 7-formative marks, in which it enjoys a very substantial and exclusive reputation', noting that it had used 7-formative marks for many years.

48 Seven submitted that its core service, and ultimate commercial purpose of its broadcasting activities, is advertising, being a service in class 35. It referred to operations in the fields of each of the Defended Goods and Services, under the 7-formative marks, including the use of 7PLUS and others in relation to apps, and the provision of services within Categories 2, 3 and 4 under a number of different 7-formative marks such as 7TRAVEL, 7SHOP, 7STORE, 7RED, 7REDIQ, 7REWARDS and 7CONNECT. Seven submitted that it offers goods and services by reference to its 7-formative marks on a significant scale.

49 The primary judge considered that the risk of prejudice to Seven if the Defended Goods and Services were not registered was overstated, noting that if 7NOW was removed in relation to those goods and services Seven could continue to use that mark in the same way that it already was using it. There was no evidence of any different future use planned by Seven. Nor, his Honour found, was there substantial prejudice to the other 7-formative marks or the use of them. The primary judge found ([144]-[146]):

… I address confusion below, but ultimately I do not accept that there would be any substantial confusion. Accepting that Seven has acquired a reputation in Australia in certain 7-formative marks (as has 7-Eleven), that reputation is in broadcasting and entertainment and through those, advertising for third parties. It has not acquired a reputation in 7NOW.

I am not satisfied that any of the 7-formative marks have acquired a reputation in connection with the Defended Goods and Services. In reaching that conclusion, I have not overlooked the fact that Seven operated a single retail outlet in Martin Place in Sydney from 2005 to 2011, which was branded '7STORE'.

As discussed further below, the use of 7NOW by another entity in connection with retailing services is unlikely to cause confusion or damage Seven's private interests.

50 The third argument advanced by Seven was that removal of the 7NOW mark would be against the public interest because use of the 7NOW mark by another trader (and particularly 7-Eleven) in connection with any of the Defended Goods and Services, while Seven continues to use the 7NOW mark in relation to the Undefended Goods and Services, is likely to give rise to confusion as to whether those goods and services are being offered, or are approved, by Seven. This again turned on the argument concerning the 7-formative marks. The primary judge noted the submission advanced by Seven that a number of traders in the broadcasting industry combine their core branding with the term 'now', such as Nine Network operating a website at the URL www.9now.com.au, which allows users to access certain digital channels operated by Nine Network including 9HD, 9GEM, 9GO! and others. Seven further submitted that the 7-formative marks, in conjunction with the use in the media industry of the term 'now', means that consumers are likely to see the 7NOW mark as indicating that goods and services, including the Defended Goods or Services, emanate from Seven. Seven submitted that removal of the 7NOW mark for the Defended Goods and Services might result in third parties, particularly 7-Eleven, achieving registration of the 7NOW mark or a similar mark in relation to similar services and that use of that mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion, comparing the current intended use by 7-Eleven of the composite mark  with the use by Seven of the 7NOW mark as a banner on the 7NOW website.

with the use by Seven of the 7NOW mark as a banner on the 7NOW website.

51 In rejecting this argument, the primary judge relevantly found ([154]-[155]):

As mentioned, there was no substantial evidence that Seven had any reputation in Australia in the 7NOW Mark as opposed to in its other 7-formative marks. The only probative evidence on the topic concerned website traffic which revealed that visitor numbers to the 7now.com.au website during the non-use period was 157 visitors and beyond the non-use period 6,769 visitors. It was not clear why people accessed the page. There was no suggestion that the 7NOW Mark was promoted in any way or that it was planned to promote it.

It can be accepted that if the 7NOW Mark were used in the context of broadcasting services, then a consumer would assume a connection with Seven. But, if a consumer saw the 7NOW Mark in connection with the sale of food or goods typically found in convenience stores, I do not think any confusion would arise. Of course, one needs to consider the notional use across the full range of potential uses contemplated by the registration for the particular specification. In the absence of any demonstrated reputation in the 7NOW Mark at all, I do not consider there to be a risk of confusion of such a degree as to warrant exercising the discretion under s 101(3).

52 The fourth reason Seven gave for the exercise of the discretion in its favour was that the Court ought to avoid drawing 'fine distinctions' between goods and services resulting in 'fragmented ownership' of the same mark by different owners in respect of similar goods or services. It cited McHattan v Australian Specialised Vehicle Systems Pty Ltd (1996) 34 IPR 537 at 544 (Drummond J); TiVo Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 252 at [498] (Dodds-Streeton J); and Sensis Pty Ltd v Senses Direct Mail and Fulfillment Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 719; (2019) 141 IPR 463 at [130] (Davies J). The fragmentation was said to be demonstrated by reference to the entirety of the goods and services listed in classes 9, 35, 38 and 41 (as set out at [2] above).

53 The primary judge considered each of the cases cited by Seven and set out the following:

[161] In Sensis, Davies J referred at [130] to McHattan and to Tivo at [498], stating:

The discretion under s 101(3) is broad: Lodestar at [35]. The relevant question is whether it is reasonable not to remove the trade mark from the Register, although the trade mark has not been used during the statutory period: Lodestar at [28]. A relevant factor is whether the removal of the mark would lead to deception or confusion as a result of fragmented ownership of the same, or a very similar mark in respect of very similar goods or services: Tivo Inc at [498], citing McHattan v Australian Specialised Vehicle Systems Pty Ltd (1996) 34 IPR 537 at 544 (Drummond J).

[162] Her Honour decided not to exclude a range of services relating to direct mail from a description of services relating to advertising and marketing services: at [1], [119]. Her Honour found at [148] that:

I find therefore that the applicant's other directory advertising services, data services and services in the general field of digital marketing are properly regarded as 'services of the same description' as the respondent's services.

[163] The discretion was informed by the closeness of the services, a finding of convergence and the extent of the applicant's reputation in its SENSIS mark and a conclusion that 'consumers will have come to know, and expect, that businesses supplying direct mail marketing services are also likely to provide broader types of direct marketing services, both digital and creative': Sensis at [151].

54 The primary judge then concluded in relation to this argument:

[164] 7-Eleven's applications are targeted. By way of example, its application filed on 23 March 2020 for the words 7NOW is for:

Class 35: Retail convenience stores; online retail convenience store services for a wide variety of consumer goods featuring home delivery service and in-store pickup

[165] 7-Eleven also filed two more applications, each on 14 November 2022. One is for the word 7NOW. The specification is for:

Class 9: Computer software and application software enabling consumers to purchase and arrange delivery of items purchased from a retail convenience store via a global computer network

Class 39: Delivery of items purchased from a retail convenience store via a global computer network

[166] The second is for the words 7NOW and for three images, similar to the image referred to at [149] above. The specification is for:

Class 9: Computer software and application software enabling consumers to purchase and arrange delivery of items purchased from a retail convenience store via a global computer network

Class 39: Delivery of items purchased from a retail convenience store via a global computer network

[167] In my view, the circumstances in McHattan, TiVo and Sensis are quite different to the present circumstances. I do not conclude that there is a risk of confusion through what Seven has referred to as 'fragmentation'.

55 Finally, the primary judge took into account the submission advanced by 7-Eleven that it was contrary to the public interest to allow one trader to monopolise a single digit as a trade mark, this being at least implicitly the case where Seven relied on its use of a range of 7-formative marks to justify the exercise of a discretion to support its exclusive right to any 7-formative mark, including for goods and services outside its core broadcasting services.

4. THE PROPOSED GROUNDS OF APPEAL AND NOTICE OF CONTENTION

56 Seven's draft notice of appeal raises four primary contentions (leave to rely on an amended draft notice of appeal was given at the hearing of the application).

57 First, in relation to Category 1 (computer software), Seven contends that the primary judge ought to have found that the use of the 7NOW banner which provided viewers with links to the 7plus app was use of the 7NOW mark in relation to Category 1 goods. Seven contends that the primary judge erred in concluding that consumers would presume that the businesses of 7NOW and 7PLUS are separate and distinct, and that the typical consumer would not understand the 7NOW mark was being used to distinguish the 7plus app as an offering of 7NOW or being co-offered by 7NOW together with 7PLUS. Seven claims that his Honour ought to have found that the 7NOW mark was being used to indicate that the same trader, namely Seven, is the origin of both. It says that his Honour erred by distinguishing between the 7NOW mark being used to indicate the origin of the service of the supply of the 7plus app and the 7NOW mark being used to indicate the origin of the 7plus app.

58 Secondly, in relation to Category 2, Seven contends that the primary judge erred in finding that Seven had not used the 7NOW mark in relation to promotional or advertising services during the non-use period, and by extension that Seven had not used the 7NOW mark in relation to 'the promotion and sale of goods and services for others, including through the distribution of on-line promotional material' (that is, Category 2). His Honour is said to have erred in finding that a commercial affiliation was likely to be inferred between Seven and the other businesses identified on the 7NOW website; in taking into account whether the typical viewer would consider that the 7NOW mark was used to indicate a trading connection between 7NOW and the goods and services offered by the other businesses identified on the 7NOW website; and in finding that the typical consumer looking at the 7NOW website would understand that 7NOW was used by Seven in promoting its own business interests.

59 Thirdly, Seven contends that the primary judge erred in finding that the 7NOW mark was not used in relation to Categories 3 and 4 (retail and wholesale services, and the bringing together of a variety of goods) because his Honour erred in considering whether consumers would have understood the services offered on the 7travel and Better Homes and Gardens Shop websites as services offered by businesses with an affiliation with 7NOW, as distinct from services connected with and provided by 7NOW. His Honour is also said to have erred in failing to consider at all whether Seven had used the 7NOW mark in relation to Category 4 services; Seven asserts that his Honour should have found that providing links to the 7travel and Better Homes and Gardens Shop websites constituted use of the mark in relation to 'the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television home shopping channels'.

60 Fourthly, Seven contends that for a number of reasons, the primary judge erred in relation to the exercise of the discretion under s 101 of the Trade Marks Act, and provides a list of errors that the primary judge is said to have made. In its proposed Notice of Contention, 7-Eleven raises some additional points relevant to this issue. For reasons connected with the disposition of grounds concerning non-use, it will be necessary to re-exercise the discretion in any event. Seven's and 7-Eleven's arguments will be addressed below in the context of the re-exercise of the discretion.

5. THE LAW CONCERNING TRADE MARK USE

61 Section 92(1) of the Trade Marks Act provides that a person may apply to the Registrar of Trade Marks to have a registered trade mark removed from the Register. The application may be made in respect of any or all of the goods or services in respect of which the mark is registered: s 92(2)(b).

62 The relevant ground on which 7-Eleven relied when it made the application to remove the 7NOW mark was the one found in s 92(4)(b): that at no time during a continuous period of three years ending one month before the day on which the non-use application was filed did the registered owner, Seven, use the trade mark, or use the trade mark in good faith, in Australia in relation to the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

63 If an application on that ground is made, the burden of proving use during the relevant period falls on the person opposing the application, that is, on Seven: s 100(1)(c).

64 A trade mark 'is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person': s 17. 'Distinguishing goods of a registered owner from the goods of others and indicating a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the registered owner are essential characteristics of a trade mark': E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Limited [2010] HCA 15; (2010) 241 CLR 144 at [42] (French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ, Heydon J agreeing).

65 Thus, the 'registered mark serves to indicate, if not the actual origin of the goods or services, nor their quality as such, the origin of that quality in a particular business, whether known or unknown by name': Johnson & Johnson Australia Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 348 (Gummow J). What must be ascertained is whether the sign used indicates origin of goods in the user of the sign (whoever that may be): see Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8 at [60].

66 Use of a trade mark in relation to goods means use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods, and similarly use of a trade mark in relation to services means use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services: s 7(4) and s 7(5). While the words 'in relation to' are of broad import at a general level, their breadth ultimately depends on their statutory context and purpose: Halal Certification Authority Pty Limited v Flujo Sanguineo Holdings Pty Limited [2023] FCAFC 175; (2023) 300 FCR 478 at [91]-[92]. In the present context, the necessary relation can be established by use of the mark in marketing, such as on a website: Self Care at [23].

67 The concept of use of a sign as a trade mark is central to the operation of the Trade Marks Act: Self Care at [7]. To establish that it has used the trade mark in connection with particular goods or services, Seven needed to establish that the mark was used as a trade mark in connection with those goods or services: Gallo at [32]-[33]. There is a distinction, not always easy to apply, between use of the sign as a trade mark and the matter addressed in the preceding paragraph, namely use of the sign in relation to goods or services: see Self Care at [23]. Seven needed to establish use of 7NOW in both respects in connection with the Defended Goods and Services.

68 For the purposes of Australian law, the classic statement as to when a sign is used as a trade mark is found in the judgment of Kitto J (Dixon CJ, Taylor and Owen JJ agreeing) in Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 425 (emphasis added):

With the aid of the definition of 'trade mark' in s. 6 of the [1955 Trade Marks] Act, the adverbial expression ['as a trade mark'] may be expanded so that the question becomes whether, in the setting in which the particular pictures referred to were presented, they would have appeared to the television viewer as possessing the character of devices, or brands, which the appellant was using or proposing to use in relation to petrol for the purpose of indicating, or so as to indicate, a connexion in the course of trade between the petrol and the appellant. Did they appear to be thrown on to the screen as being marks for distinguishing Shell petrol from other petrol in the course of trade?

The words emphasised above draw attention to the importance, in establishing trade mark use, of the link between the trade mark in question and particular goods or services.

69 An alternative formulation of the 'fundamental question' was provided by Gummow J (in an infringement context) in Johnson & Johnson at 347-348, paraphrasing Williams J in Mark Foys Ltd v Davies Co-op and Co Ltd (the Tub Happy case) [1956] HCA 41; (1956) 95 CLR 190 at 205:

whether those to whom the user is directed are being invited to purchase the goods (or services) of the defendants which are to be distinguished from the goods of other traders 'partly because' (emphasis supplied) they are described by the words in question.

70 Yet another way of putting it is that 'use "as a trade mark" is use of the mark as a "badge of origin" in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods': Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; (1999) 96 FCR 107 at [19] (Black CJ, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ); approved in Gallo at [43].

71 Context is all-important when considering such questions: Shell at 422; Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Limited v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; (2018) 259 FCR 514 at [56] (Nicholas, Yates and Beach JJ); RB (Hygiene Home) at [53]. The context includes the relevant trade and the way in which the mark has been displayed in relation to the goods (or services): Johnson & Johnson at 347; Self Care at [24].

72 Therefore, each case in this field will depend on its own particular facts. Nevertheless, it is instructive that in Shell, Kitto J went on to make clear that the question was not answered simply by pointing out that the allegedly infringing figure in that case had been used to represent Shell petrol. The allegedly infringing use had been in a film which, undoubtedly, was intended to promote Shell petrol. But that was not enough for it to be used as a trade mark. Kitto J found that the only purpose of the film was to convey 'a particular message about the qualities of Shell petrol' (at 425). His Honour went on to say at 425:

This fact makes it, I think, quite certain that no viewer would ever pick out any of the individual scenes in which the [oil drop] man resembles the respondent's trade marks, whether those scenes be few or many, and say to himself: 'There I see something that the Shell people are showing me as being a mark by which I may know that any petrol in relation to which I see it used is theirs.'

See also Johnson & Johnson at 343 (Burchett J).

73 The enquiry is an objective one without reference to the subjective trading intentions of the user of the mark: Gallo at [33]; Self Care at [24]. But as the above extract from Shell shows, that does not rule out considering how the mark would appear to have been used to a hypothetical (presumably reasonable) consumer: see also Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Company Pty Ltd (1996) 33 IPR 161 at 182 (Sackville J, Lockhart J agreeing). The Court must ask what a person looking at the relevant material would see and take from it: Anheuser-Busch, Inc v Budějovický Budvar, Národní Podnik [2002] FCA 390; (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [186] (Allsop J). After all, the relevant context includes how the words used would present themselves to persons who read them and form a view about what they connote: Self Care at [24].

74 Consistently with these principles, and purely by way of example, in Johnson & Johnson (at 351), Gummow J posed the question as:

whether, in the setting on the package on which 'Caplets' is depicted, it appears to possess the character of a word which Johnson & Johnson is using in relation to its paracetamol product, for the purpose of indicating or so as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between Johnson & Johnson and the contents of the package. Does Caplets appear as a mark for distinguishing a Johnson & Johnson product from other pain-killing products in the course of trade?

75 In the infringement context in which that question was asked, matters such as the relative lack of prominence of the use of the word 'caplets' on Johnson & Johnson's Tylenol packaging meant that the question was answered in the negative. But in the same case, the more prominent use of 'CAPLETS' on Sterling Pharmaceutical's Panadeine and Panadol packaging, together with other matters, meant that Sterling successfully resisted a non-use case by establishing that it had used 'CAPLETS' as a trade mark (at 343-344). Again, context is all-important.

6. WHETHER SEVEN HAS ESTABLISHED ERROR

6.1 Category 1 - computer software (grounds 1-6)

76 Seven submits that the 7NOW mark would appear to consumers as possessing the character of a brand which the website proprietor was using to indicate a connection in the course of trade between it and the goods and services promoted and offered on the website. More particularly, it submits that the promoted and offered goods included computer software, being the 7plus app, which is promoted by the text '7plus' in a tile at the top of the web page and also in the columns at the bottom of the web page, including by the links 'Get the iOS app' and 'Get the Android app' as they appear on the page.

77 Seven submits that the fact that both the 7PLUS and the 7NOW marks appear on the web page does not preclude the 7NOW mark from being used in relation to the app, because both marks are used to distinguish computer software. Nor, Seven submits, does it matter that users who clicked on links to download the 7plus app were taken elsewhere to download the software, because the use of 7NOW as a trade mark was already complete by then: it was used to promote and offer the software.

78 Seven also submits that the primary judge applied the wrong test by considering whether consumers would think that there was a 'commercial connection' between the businesses of 7NOW and 7PLUS, rather than considering whether the use of 7NOW would lead consumers to think there was a connection in the course of trade between the person who applied that mark and the computer software. Seven submits that his Honour further erred by finding that consumers would not understand that the 7NOW mark was being used to indicate the origin of the service of the supply of the 7plus app as opposed to the origin of the 7plus app itself.

6.1.2 Consideration of Category 1

79 The first step in Seven's submission is that Seven had established that during the 7NOW website period it offered computer software, namely the 7plus app, including by way of links at the bottom of the 7NOW web page. That is not contentious and may be accepted.

80 The second step in Seven's submission, which is contentious, is that the use of 7NOW in distinctive lettering and colour in a prominent banner on the 7NOW website was the use of a sign by Seven in the course of trade to promote 'the offerings on the webpage'. One such offering was the 7plus app, available via the links to the iOS and Android app stores. Seven submitted that it necessarily followed that the 7NOW mark was being used in connection with computer software.

81 Seven seeks to reinforce the connection between the use of the 7NOW mark and the offering of the software by pointing to the following features of the website:

(1) to consumers, the 7NOW mark would appear to possess the character of a brand which the website proprietor was using to indicate a connection in the course of trade between it and the goods and services promoted and offered on the 7NOW website;

(2) both 7NOW and 7PLUS use the distinctive red stylised '7' logo and users would have understood that the marks were related, and both being used as a badge of origin in relation to the app; and

(3) there is a '7plus' tile immediately below the 7NOW banner, reinforcing the connection between the two.

82 However, it is not enough to say generally that the 7NOW mark is used to promote 'the offerings on the website' and then to point out that the app is offered on the website. The use of the mark, and the offering of the app, must be assessed in all their context to see the nature and the extent of the connection between the two.

83 Doing that leads us to reject Seven's submissions and conclude that Seven has not established error on the part of the primary judge.

84 In this regard one must consider the overall context of the use alleged. The sole appearance of the 7NOW mark on the website is in a red banner running along the top of the array of tiles which comprise the bulk of the website: see Annexure A. The size of the mark as displayed is relatively small, and the banner is reasonably narrow, compared to the scale of the tiles themselves. But the fact that it is at the top increases its relative prominence. The 7NOW mark itself is the combination of a numeral and an ordinary English word, and it is presented on the website with a stylised '7' and the graphic presentation of the word 'now'. These features would suggest to the consumer, should they come across the website, that it is a trade mark. However, the question of relevance is whether the 7NOW mark is used in respect of computer software.

85 Beneath the banner is a series of 48 tiles that we have extracted above at [22], arranged in the grid pattern visible in Annexure A. Some tiles bear what were described by the primary judge as 7-formative marks, including '7plus', '7mate', '7food' and others with the number '7' as a prefix. Other tiles bear the names of what consumers may understand to be references to television shows, for example, 'Home and Away Official Site' and 'Cricket on 7'. The primary judge found that the typical viewer would understand that the 7NOW website contained links to various businesses, accessible by clicking on the relevant tile, and that they would understand that many of the businesses represented by a tile were commercially related to Seven; in particular, they would assume that every tile with the number '7' in it was commercially related in some way to Seven. These findings were made in the context of his Honour's consideration of Category 2 but are equally applicable to Category 1. However, for some of the businesses, in particular those in the bottom row, it is not apparent that they are related to Seven and the primary judge made no finding that consumers would recognise any such connection.

86 Beneath the array of tiles is the set of links reproduced in the lower part of the website, set out for clarity at [28] above. It is not helpful to give a further description of these, save to note that they are much smaller than the tiles, separated from them by white space, and visually distinct from them, in that they mostly consist of plain text and contain only one graphic element: the 7PLUS logo in the top left hand corner.

87 The primary judge found that the viewer would not consider that the 7NOW mark was being used to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the 7plus app and 7NOW. His Honour, in our respectful view, correctly noted that there was in fact no use of the words '7plus app' on the 7NOW website, meaning that there was no reference at all to the very computer software relied upon by Seven in support of its case. Rather, it was necessary for the consumer first to arrive at the 7NOW website, secondly to perceive and read the words underneath the 7PLUS logo on the bottom of the page, and thirdly to click on the words beneath that logo to come to the iOS or Android app. Only then would the use in connection with computer software be revealed.

88 The relevant finding of the primary judge at [99] was that the consumer would not understand that the 7NOW mark was being used to distinguish the 7plus app. In our view it was entirely within the scope of the primary judge's evaluative findings to conclude that a consumer would not consider that the 7NOW mark was being used as a badge of origin for that computer software.

89 Rather, in our view, the user is likely to infer from the positioning of the banner across the top of the (more prominent) grid of tiles that 7NOW is the name of a service that has something to do with bringing together, aggregating, presenting and promoting the collection of channels, programmes, news and magazine offerings and commercial websites which the grid contains.

90 Seven submitted that the primary judge erred in taking into account that the typical consumer would not understand that the 7NOW mark was being used to distinguish the 7plus app 'as an offering of 7NOW or as being co-offered by 7NOW together with 7PLUS'. But while it is true, as Seven submits, that the use of 7PLUS as a badge of origin for the app is not necessarily determinative of whether 7NOW was also used as a mark in relation to the app (see for example Anheuser-Busch at [191]), it remains relevant to the overall evaluative task to consider the manner in which one mark is used in relation to others: Self Care at [25]. This is plainly what the primary judge did in forming his conclusion. We detect no error in that respect.

91 Seven submitted that the 'consumer's understanding of the identity of the user or supplier is irrelevant'. That is so: see Johnson & Johnson at 348. But we do not consider that the submission fairly characterises the primary judge's meaning in the impugned passage. His Honour's focus was on whether the consumer would perceive the mark as being used to distinguish the app from computer software supplied by others, either as an offering of whoever was using the 7NOW mark, or as a joint offering of that user and whoever is the user of the 7PLUS mark. It was not on whether the consumer would ascertain the particular identity of the supplier. Thus, when Seven goes on to refer to the fact (unknown to users of the website) that both the 7NOW and 7PLUS marks were in fact owned by Seven, that too is irrelevant to the present enquiry.

92 We similarly do not accept another submission by Seven about the same passage, that the primary judge erroneously applied, as a test of use as a trade mark, whether or not a typical consumer would think there was a commercial connection between the businesses of 7NOW and 7PLUS. Reading the primary judgment at [99] as a whole, it is apparent that his Honour was simply acknowledging the apparent commercial connection between the two marks, but at the same time finding that the connection was not such as to lead the typical consumer to infer that the 7plus app was being offered by the 7NOW business (whatever its identity), either exclusively or along with 7PLUS.

93 Seven also challenged the finding of the primary judge at [99] that the consumer would not 'understand that the 7NOW mark was being used to indicate the origin of the service of the supply of the 7PLUS App as opposed to the origin of the 7PLUS App itself' (emphasis in original). Seven submits that his Honour took that into account as weighing against a finding of trade mark use. We do not agree that this had any separate or additional weight that influenced the primary judge's evaluative finding. Rather, his Honour was merely excluding the possibility that the consumer would perceive that the 7NOW mark had been applied as a badge of origin of the goods, either by the developer of the app or by a person who was supplying the app.

94 Accordingly, we reject grounds 1 to 6.

6.2 Category 2 - the promotion and sale of goods and services for others (grounds 7 and 8)

95 Seven submits that the primary judge erred in relation to Category 2. According to Seven, the whole purpose of the 7NOW website is to promote goods and services, including the goods and services of others. Seven refers in particular to the tiles on the bottom row of the grid, such as 'AirTasker', '60 starts at 60' and so on. The goods and services that were offered on the websites linked to those tiles were, Seven says, being promoted under the 7NOW banner that runs across the top of the web page. That, it submits, is the use of the 7NOW mark in connection with the service of the promotion of the goods and services of others.

96 7-Eleven submits that the proximity or relationship of the sign to each relevant good and service required particular attention and that it must be such as to show that the sign is being used to indicate its trade origin. It observes that the 7NOW mark is used only once on the website and that the website provides no information about the 7NOW mark, nor any factual context to inform a hypothetical visitor about it. The site did not directly offer any goods or services, merely presenting a directory of click-through tiles that a visitor might select to be directed to other websites. The tiles had no accompanying text. To the extent that a visitor had any clear expectation as to the service that they would be offered or provided if they clicked on a tile, that expectation can only have been informed by their familiarity with the trade mark used on the tile itself, where each tile presented a clear and dominant trade mark referable to any service that the visitor expected to receive or be offered.

97 Accordingly, 7-Eleven submits, the 7NOW mark was not presented in a manner that indicated the trade origin of any good or service. The website is simply a list of the availability of a range of other websites that were available 'now' in connection with the Seven business. A consumer would not have understood the 7NOW mark to indicate the trade origin of a directory service because they would not understand directory services to be the sort of service for which they needed to consider issues of commercial origin, it being purely informational.

98 Furthermore, 7-Eleven submits that the Category 2 services are for 'promotion and sale of goods and services for others …'. The 7NOW website is not a vehicle for performing or delivering such a service. To the extent that Seven offers a service of promoting goods and services of others, it does so through other trade marks (being 7RED and 7REDiQ), which were not offered on the 7NOW website. Furthermore, 7-Eleven contends that the service required is for the promotion and sale of goods and services for others. Nowhere is this evident on the website.

6.2.2 Consideration of Category 2

99 Category 2 is 'the promotion and sale of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests'.

100 The primary judge rejected Seven's submissions on the basis that the typical viewer of the 7NOW website would not understand that the 7NOW mark was being used in the promotion of the goods or services of the sites identified as examples, being 60 Starts at 60, Society One, HealthEngine or AirTasker. His Honour found (at [108]-[109]) that the typical viewer would understand that the 7NOW website contained links to various businesses, that many of those businesses (but not all) were commercially related to Seven (especially those with a '7' in their names) and that the typical viewer would not consider that the 7NOW mark was used to indicate a trading connection between 7NOW and the goods and services offered by those other businesses.

101 However, in our respectful view, the learned primary judge mistook the nature of the Category 2 services. They are not the services of others but rather the service of promoting and selling goods and services for others. We understand the words 'for others' to mean 'for and on their behalf'. One aspect of such a service will include the promotion of services for others by reference to their trade marks.

102 Once it is appreciated that Category 2 poses a connection between the use of the 7NOW mark and the service of promoting the goods and services of others, it becomes apparent that the inference that consumers are likely to make - that 7NOW is the badge of origin of a service that brings together, aggregates, presents and promotes the offerings of others - is sufficient to establish both use as a trade mark, and use in relation to that relevant service.

103 That being so, it matters not that users may perceive a connection between whoever affixed 7NOW to the website and whoever is offering at least some, even most, of the goods and services that can be obtained by clicking on the various tiles. That perception would not be sufficient to conclude that all the services and goods that can be obtained by clicking on the tiles are being offered by the same entity that is identified with the 7NOW mark.

104 We do not accept 7-Eleven's submission that even to the extent that the 7NOW website was offering 'directory services', the use of the 7NOW sign was not presented in a way that indicated the trade origin of those services. 7-Eleven submitted that this was because 'a visitor would not understand directory services to be the sort of service for which they needed to consider issues of commercial origin'. However, the relevant question is whether it was apparent that a service was being provided (it was) and whether the mark was used in such a way that the user of the website would understand it to indicate the origin of the service in the course of trade (it was). It is no answer to say, as 7-Eleven did, that the visitor 'would have understood it to be a mere directory page that had been given the label or page heading "7NOW"'. It is tolerably clear that '7NOW' is the name of that directory service, and that it is given that name at least 'partly' so that the service could be distinguished from similar services provided by others: cf. Johnson & Johnson at 347-348.

105 7-Eleven also submitted that the 7NOW website was not even a vehicle for performing or delivering the service of the promotion and sale of goods and services for others 'as it merely displays a grid of icons linking to other websites'. But 7-Eleven does not explain how a grid of those icons - bringing to the consumer's attention the services and goods offered on the linked websites and making it easier for the consumer to acquire those services and goods - does not serve to promote those services and goods.

106 In our view, the connection shown on the website between the 7NOW mark, which has the character of a brand, and the actual performance of those promotional services is sufficient to mean that it has been used as a trade mark in relation to those services. It does not matter that, as 7-Eleven submitted, Seven also offers promotional services through distinct trade marks (7RED and 7REDiQ). Those marks are nowhere to be seen on the 7NOW website, which makes the use of 7NOW as a trade mark clear enough on its own.

107 7-Eleven also points out that the category refers to the 'promotion and sale of goods and services for others'. We accept the submission of 7-Eleven that there is no evidence that the 7NOW website, as distinct from the linked websites, was a means of delivering the service of selling goods and services of others under or by reference to the 7NOW mark.

108 Accordingly, we are satisfied that Seven has demonstrated error on the part of the primary judge in respect of Category 2 insofar as it concerns the promotion of goods and services for others, but not in relation to the sale of such goods and services. Grounds 7 and 8 should be upheld in part.

6.3 Categories 3 and 4 - retail and wholesale services, and the bringing together of a variety of goods (grounds 9 and 10)

109 Seven submits that the primary judge erred in concluding that there was no evidence of use within Categories 3 and 4. It submits that the services in those categories were supplied on the websites to which users would be taken if they clicked on the tiles on the 7NOW website, such as the '7travel' tile from where, as the primary judge found, users could receive retail services from 7TRAVEL. Seven submits that it promoted those services on the 7NOW website by displaying the tiles to users: the 7NOW was used in that promotion because it was prominently displayed in the banner across the top of the website and in the domain name.

6.3.2 Consideration of Categories 3 and 4

110 Category 3 is:

retail and wholesale services including retail trading via television programmes and by telephone and electronic means including the Internet

Category 4 is:

the bringing together, for the benefit of others, of a variety of goods enabling customers to conveniently view and purchase those goods including by mail order, telecommunications, website or television shopping channels

111 Seven's argument in relation to these categories is that it supplied the services described on the websites to which the user would be taken if they clicked on certain tiles on the 7NOW website, for example '7travel'. The primary judge found that the 7travel website and the Better Homes and Gardens Shop website (both of which are represented in tiles on the 7NOW website) supply retail services. Once again, according to Seven it promoted those services on the 7NOW website by displaying the tiles to users. The 7NOW mark, Seven said, was used in the promotion of those services because of its presence in the banner across the top of the tiles.

112 In assessing these submissions it is important to keep in mind the whole context of the use of the mark, and also the goods and services covered by Categories 3 and 4. The 7NOW mark is used in a banner that is associated with a number of tiles that link to different sites that offer different things: some are entertainment, sport, news or magazine offerings; some are sites evidently associated with Seven that effectively sell services to consumers, for example 7travel; some are apparently third party sites that offer services, for example AirTasker.

113 The primary judge accepted that the 7travel website may be characterised as an 'e-commerce platform' in that if one accesses that website by clicking on the '7travel' tile on the 7NOW website, one would be able to book travel services. However, his Honour also found (at [118]) that the typical consumer would not have understood those services as being offered by reference to the 7NOW mark.

114 In our respectful view, that finding is unimpeachable. It is not sufficient for the establishment of trade mark use to contend, as Seven does, that it supplied the relevant services on the websites to which users would be taken if they clicked on the tiles. The use relied upon by Seven was the display of the 7NOW website per se. Contrary to the contention advanced by Seven, the mere display on that website of a tile with '7travel' on it (to continue with the example) was not a use of the 7NOW mark in relation to 'retail services' that were accessed after clicking on that tile and being taken to another site.

115 Contrary to Seven's submission, we do not consider that the primary judge erred in finding it relevant that the typical consumer would not have understood the services offered on the websites to which they navigated as being provided by 7NOW. The focal point of the primary judge's consideration was the nature of the services being provided under the 7NOW mark. It was not possible to discern from the 7NOW website that services of the type falling within either Categories 3 or 4 were made available by the provider of that website.

116 Accordingly, grounds of appeal 9 and 10 must be dismissed.

7. THE EXERCISE OF DISCRETION (Ground 11, Notice of Contention)

117 We have in section 6.2 above found that Seven has established trade mark use of the 7NOW mark in respect of a portion of the Category 2 services, being services for 'the promotion of goods and services for others including through the distribution of on-line promotional material and promotional contests', though not for the sale of those goods and services. Accordingly, the registration of the 7NOW mark will remain on the Register in relation to those services.

118 Leaving that to one side, Seven contends that this Court on appeal should find, in the exercise of its discretion, that the Category 1, 3 and 4 goods and services and the balance of the Category 2 services ought also to remain on the Register. 7-Eleven submits that the primary judge did not err in the exercise of the discretion. It supports the primary judge's conclusion by reference to its Notice of Contention where it contends that, in addition to the reasons given, the discretion to permit the 7NOW mark to remain (in respect of the Defended Goods and Services) ought to have been refused because of Seven's conduct in relation to trade mark applications filed by 7-Eleven and subsequently by Seven for 7 SELECT, 7 FRESH and 7 CONNECT.

119 A threshold question arises as to whether the discretion of the primary judge miscarried such that this Court should intervene. It is not sufficient for the purposes of an appeal from a discretionary judgment for this Court to conclude that it would have exercised the relevant discretion differently had it been in the position of the primary judge. As Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ explained in House v The King [1936] HCA 40; (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 505: