FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

University of Sydney v National Tertiary Education Industry Union [2024] FCAFC 57

File number: | NSD 1129 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | PERRAM, LEE AND KENNETT JJ |

Date of judgment: | 17 May 2024 |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – university – right to intellectual freedom – appeal of remitter judgments – where primary judgment appealed to Full Court – where Full Court allowed appeal and remitted matters to primary judge for hearing and determination – alleged contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) – whether open to appellant to raise issue of onus of proof where issue had not been substantively raised before primary judge, in the first appeal or on remittal – whether primary judge erred by proceeding on basis that appellant bore onus of proof – whether onus of proof discharged – whether primary judge gave adequate reasons – whether second respondent’s comments constituted exercises of intellectual freedom – whether second respondent committed “serious misconduct” by disobeying lawful directions in making the comments that were alleged exercises of intellectual freedom |

Legislation: | Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ss 50, 340, 539, 545, 570 University of Sydney Act 1989 (NSW) s 6 |

Cases cited: | Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority v Arnica Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCA 815; 293 FCR 533 Avel Pty Ltd v Multicoin Amusements Pty Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 88 Coulton v Holcombe (1986) 162 CLR 1 Fair Work Ombudsman v National Union of Workers [2019] FCA 1826 House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 Iyer v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2000] FCA 1788 James Cook University v Ridd [2020] FCAFC 123; 278 FCR 566 National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2020] FCA 1709; 302 IR 272 National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2021] FCAFC 159; 309 IR 159 National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2022] FCA 1265; 318 IR 460 National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2023] FCA 537 National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney (No 2) [2021] FCAFC 184 Ridd v James Cook University [2021] HCA 32; 274 CLR 495 Russell v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2023] FCA 1223 Tomlinson v Ramsey Food Processing Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 28; 256 CLR 507 Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Ltd v Marmara [2014] FCAFC 84; 222 FCR 152 Vines v Djordjevitch (1955) 91 CLR 512 Water Board v Moustakas (1988) 180 CLR 491 |

Division: | Fair Work Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Employment and Industrial Relations |

Number of paragraphs: | 256 |

Dates of hearing: | 15–16 August 2023 |

Counsel for the Appellant: | JT Gleeson SC with S Hartford Davis and K Bones |

Solicitor for the Appellant: | Ashurst |

Counsel for the Respondents: | B Walker SC with S Kelly |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Hall Payne Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 1129 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY Appellant | |

AND: | NATIONAL TERTIARY EDUCATION UNION First Respondent TIM ANDERSON Second Respondent | |

order made by: | PERRAM, LEE AND KENNETT JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 May 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to the Appellant to file a Further Amended Notice of Appeal in the form handed up on 16 August 2023.

2. The appeal be allowed.

3. Orders 1, 3, 5 and 7 made on 22 November 2022 and Orders 1 and 2 made on 5 June 2023 be set aside and in place thereof it be ordered that:

(a) The Applicants’ application be dismissed.

4. If any party wishes to seek an order as to costs:

(a) that party is to file, within 7 days, written submissions on costs of no more than 5 pages together with any evidence on which it wishes to rely;

(b) any other party may file, within a further 7 days, written submissions in response of no more than 5 pages together with any evidence on which it wishes to rely; and

(c) the question of costs will be decided on the papers, unless the Court is of the view that an oral hearing is required.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

PERRAM J:

1 I have had the advantage of reading in draft the reasons of Kennett J. I gratefully adopt his Honour’s recitation of the facts and arguments and express my general and respectful agreement with his Honour’s reasons save for one matter. This is whether the Union parties discharged their onus of proof in relation to cl 317. I do not think that they did. This divergence from the reasons of Kennett J leads to a different outcome for the appeal to which I will return at the end of these reasons. I have adopted in these reasons the defined terms used by Kennett J.

2 In FCAFC 1, the Full Court held at [187]-[188] that cll 315-317 constituted a complete statement of the intellectual freedom provided for by the 2018 Agreement. I agree with Kennett J that one consequence of that interpretation is that cl 317 is not an exception or proviso to the intellectual freedom protected by cl 315 but rather an essential part of that freedom. It follows that, even if one considers the question of where the onus lay through the provisions of the 2018 Agreement, it was for the Union parties to prove that Dr Anderson’s various comments had complied with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards referred to in cl 317. Although initially disputed in written submissions, this proposition was accepted by Senior Counsel for the Union parties, Mr Walker SC, in oral argument: T60.22-27.

3 So understood, the Union parties’ case that Dr Anderson had exercised the intellectual freedom within cl 315 must be taken to have entailed the positive assertion that he had acted in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards referred to in cl 317: see FCAFC 1 at [154]. On remitter, the trial judge found that Dr Anderson’s various communications fell within the intellectual freedom in cl 315 but his Honour gave little attention to cl 317. By ground 1 of the appeal, it was alleged that this was because his Honour erroneously assumed that the onus lay upon the University parties to prove that Dr Anderson had failed to comply with some standard in cl 317. As extracted in Kennett J’s reasons, the trial judge had sought unsuccessfully to elicit from Senior Counsel for the University parties an identification of the standards with which Dr Anderson had failed to comply. In that circumstance, it is argued by the University that the trial judge gave little further thought to cl 317 since it appeared to his Honour to be a case advanced by the University parties which had, during the cut and thrust of closing submissions, come to nothing: see FCA 2 at [23], [30], [38], [49] and [53].

4 The Union parties submitted, first, that the University should not be allowed to raise the issue of onus on appeal having not done so before the primary judge; and second, that in any event there was no error in his Honour’s disposition of the cl 317 issue in relation to each of Dr Anderson’s comments. I will deal with each of these in turn.

5 On the first, neither party made any submissions to the trial judge about which of them bore the onus of proving Dr Anderson’s compliance with cl 317. As I have explained, the correct position was that the Union parties bore that onus. The question which then arises is whether the University should be permitted to raise the issue of onus where it failed to do so before the trial judge. Ordinarily, the answer to this question would be no: see, e.g., Water Board v Moustakas (1988) 180 CLR 491 at 497 per Mason CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Dawson JJ. However, the unusual and chequered history of this proceeding includes the fact that the first Full Court remitted the matter to the trial judge to be dealt with on the evidence as it stood so that neither party was afforded an opportunity to lead any further evidence: FCAFC 2 at order 3(b) and [12]. Thus, even if the University parties had submitted to the trial judge (as they should have) that the onus of proof in relation to cl 317 rested on the Union parties, that submission could not have been met by further evidence and the evidentiary position would have been precisely as it is now. The failure of the University parties to raise the onus of proof issue does not therefore cause the Union parties evidentiary prejudice.

6 Whilst there may be a costs prejudice to the Union parties inasmuch as this appeal may not have been necessary had the onus point been raised at the remitted trial, this is not self-evident. In particular, regardless of the result of the remitted trial, an appeal by one or both sets of parties was likely. This is not a case therefore where the failure of a party to raise a point is likely to have resulted in the prolongation of litigation. Given the belligerent attitudes of these parties, the combustible subject matter of their dispute and the grinding manner in which the litigation has been conducted, it is unlikely that there are any savings which have been lost by reason of the University parties’ failure to raise the question of onus at the remitted trial.

7 In my view, therefore, it is open to the University to raise the question of the onus of proof on appeal and, like Kennett J, I would uphold its submissions about where that onus lay.

8 Mr Walker’s second submission was that there was no error in the primary judge’s approach to cl 317 and that his Honour’s disposition of the issue must be understood in the context of the joinder of issue between the parties or lack thereof given the University parties’ failure to identify standards with which Dr Anderson had failed to comply. This submission took as its point of departure the Full Court’s observations in FCAFC 1 at [128] (‘as a matter of forensic logic, the [Union parties] having pleaded exercise of the right in accordance with cl 315, it was for the [University parties] to plead that any such exercise had to [be in] accordance with cl 317’) and [198] (‘The [Union parties] were entitled to…plead an exercise of the right in accordance with cl 315 and leave it to the University [parties] to rely on cl 317…[and] were also entitled to allege (as they did), in response to the University [parties’] case, that the exercise of the rights did in fact satisfy cl 317.’). The corollary of these observations was said by the Union parties to be that it was for the University parties to identify the standards contemplated by cl 317 and the manner in which Dr Anderson’s comments transgressed them. The Union parties submit that even if they bore the onus of proof in relation to cl 317, it was still necessary for the University parties to identify the standards from which it was said that Dr Anderson had impermissibly departed. As I have already noted, at the remitted trial the primary judge asked Senior Counsel for the University parties to identify the standards relied upon in relation to cl 317 and Senior Counsel did not identify any such standard. Since the University parties never identified a standard with which they alleged Dr Anderson failed to comply, it follows on this view that whilst the Union Parties bore the onus under cl 317, that onus had no content where the University failed to identify a standard and was therefore discharged by the Union Parties doing nothing.

9 One apparent advantage of this conclusion is that it gives cl 317 a procedurally fair operation. If the University parties had in mind making an ultimate submission that Dr Anderson had failed to comply with, for example, an obscure code of conduct for university lecturers, it might be somewhat unfair for them not to have forewarned the Union parties prior to the close of the evidence that they were going to make such a submission. In particular, keeping their tinder dry in this fashion might deny the Union parties a fair opportunity to meet the argument by leading evidence about it.

10 On the other hand, it would be curious if a party bearing the onus of proof is not obliged to do anything to discharge that onus until such time as the party not bearing the onus points out what the first party needs to prove. In this case, if correct, that view leads to the unusual outcome that the party bearing the onus discharges it without proving anything.

11 With some hesitation, I have respectfully come to the view that I do not agree with Kennett J on this aspect of the appeal. This is for two reasons. First, whilst I see the force of the procedural fairness point, ultimately I have come to the view that it is not sound. If the University parties had raised in their closing submission some legal or ethical standard with which, without notice to the Union parties, it was now alleged that Dr Anderson had not complied, this would be procedurally unfair. However, in that event, the solution would be to grant the Union parties the right to re-open their case to deal with the point. Although the Full Court had remitted the matter to the trial judge to be dealt with on the evidence already adduced I do not think that the Union parties could have been shut out from leading evidence if the University had, in its closing submissions, identified a standard with which it was said Dr Anderson had not complied.

12 Secondly, cl 317 is part of the total statement of the intellectual freedom erected and protected by cll 315-317. Whilst it may be accepted in principle that issues in dispute in civil litigation must be considered in light of the joinder of issue between parties, that proposition does not detract from the fact that a party bearing an onus must present a case which enables the Court to feel actual persuasion of the relevant fact. Here it was for the Union parties to prove that the conduct of Dr Anderson was in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards referred to in cl 317. I would respectfully observe that concluding that this burden has no content unless the opposing party first identifies a standard is apt to sap the salience of this burden. No doubt the intellectual freedom referred to in cl 315 is a fine and proper thing but it is cut from the same cloth as the notions of academic responsibility in cl 317. Those who would drape themselves in the former cannot avoid the garb of the latter. In this case, this was not an issue which skulked in the blurry littoral of the freedom. Rather, when all is said and done, the fact is that Dr Anderson had juxtaposed a Nazi swastika with the flag of the State of Israel.

13 Dr Anderson advanced in this Court a series of engaging observations designed to demonstrate that not every use of the Nazi swastika is necessarily outside the notions of academic responsibility referred to in cl 317. For example, in a history course about the rise of the Nazis in Germany it would be difficult to see that the symbol could be avoided.

14 However, thought experiments of this kind needed to be brought down to the realities of this litigation. Having waded into the briar patch which is the situation in Palestine it was Dr Anderson who juxtaposed the Nazi swastika with the flag of the State of Israel. Accepting as I do that it may in an appropriate case be consistent with the standards referred to in cl 317 to use a Nazi swastika in the work of a university academic, it was for Dr Anderson to engage in the forensic gymnastics of explaining how his at least incendiary conduct could be characterised as being consistent with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards referred to in cl 317. This he did not do.

15 In my view and with respect, it follows that the primary judge misplaced the onus in relation to cl 317 on the University parties. It is tolerably clear from FCA 2 at [23], [30], [38], [49] and [53] that his Honour, having dispensed with the University parties’ ineffectual case in relation to cl 317, did not turn his mind to whether the Union parties’ case positively satisfied him that Dr Anderson’s comments met the highest ethical, professional and legal standards. If his Honour did so turn his mind and was so satisfied, I would accept that he did not provide adequate reasons in this regard as alleged in ground 3 of the appeal. On either view, the primary judge erred in his consideration of whether Dr Anderson’s comments constituted an exercise of the intellectual freedom.

16 Nothing said by the Full Court in FCAFC 1 at [128] and [198] is inconsistent with this conclusion. Their Honours were not considering there the question of where the onus of proof lay in relation to cl 317. And it does not follow from their observation that it was forensically logical in this case for the University parties to plead Dr Anderson’s non-compliance with the cl 317 standards that the University parties assumed any legal or evidentiary burden in relation to that issue.

17 The parties were ad idem that this Court should determine the outcome of the case rather than remit the case for yet another rehearing. Whilst I would ordinarily regard remitter as the appropriate order in this case, the tortured procedural history of the matter makes it appropriate for this Court to reach a view on what the correct outcome is.

18 The University submitted that Dr Anderson’s comments fell short of the highest ethical, professional and legal standards because they were variously intemperate ad hominem attacks, not in pursuit of academic excellence, and not in compliance with lawful and reasonable directions. It was said by Senior Counsel for the University, Mr Gleeson SC, that each of these arguments had been raised by the University parties in written submissions on remitter even if they were not developed in oral argument. In response, the Union parties argued that these points were effectively abandoned by the University parties at the remitted trial in the exchange between its Senior Counsel and the primary judge extracted in the reasons of Kennett J and that the University should not now be allowed to raise for the first time arguments which seek to give content to the cl 317 standards. In any event, the Union parties submitted, the University’s arguments did not suffice to take Dr Anderson’s comments outside the scope of cll 315-317.

19 As will shortly become apparent, it is unnecessary for me to resolve these issues. For present purposes, I am prepared to assume in the Union parties’ favour that these arguments were either not raised or abandoned by the University parties below and that this Court should disregard them.

20 On appeal, the Union parties did not point to a positive case run by them before the primary judge in relation to cl 317. A review of the written submissions and transcript of oral argument from the remitted trial reveals that the reason for this is that no such positive case was advanced because the Union parties were labouring under the misapprehension that it was the University parties which bore the onus of proving Dr Anderson’s non-compliance with cl 317. The Union parties did not address the cl 317 standards in their written submissions in chief on remitter, a fact which was pointed out by the University parties at [53] of their written submissions (‘The [Union parties’ submissions] do not address the application of the highest ethical, professional and legal standards under cl 317 (cl 256)’). That this was a deliberate forensic choice by the Union parties is made clear by [8]-[10] of their submissions in reply:

8. As to paragraphs [37]-[41] of the [University parties’ submissions]:

(a) the content of the “highest ethical, professional and legal standards” must be assessed by reference to the circumstances of any given case;

(b) the identification of those standards cannot involve a process that impairs the right created by cl 315 (such as reliance on University policies that impair the right);

(c) it falls to the [University parties] to identify the standards that it says should have been, but were not, complied with; and

(d) the opinion of Professor Garton (see [University parties’ submissions] [45]-[46]) is irrelevant to the question of what standards apply, and the content of those standards.

9. Forensically, the [University parties] have the burden of demonstrating that Dr Anderson failed to comply with cl 317. To discharge that burden, they must identify the relevant standards that apply by operation of cl 317 and explain how they have not been met. They have not done so. However it can be observed that:

(a) the standards to which cl 317 refers must be connected to the exercise of intellectual freedom (so much follows from the wording of cl 317) and there must, therefore, be a direct connection between the relevant standard and the exercise of that freedom;

(b) legal standards reflect the requirement to exercise intellectual freedom within the bounds of the law, as in force from time to time;

(c) ethical standards reflect the bounds within which academics conduct their work and include, for example, the ethical standards set out in the terms of research grants;

(d) professional standards are not a reference to general standards of civility but reflect the standards relating to the profession (such as evidence-based research, peer reviews, scholarly reviews, governance models and the like).

10. The [University parties] have not identified with any precision the standards they say were applicable to Dr Anderson, nor how he failed to comply with them.

21 The Union parties therefore did not advance a positive case that sought to identify the standards applicable as a result of cl 317 and to demonstrate that Dr Anderson had complied with such standards. In those circumstances and given that the Union parties bore the onus in relation to cl 317, I cannot be satisfied that Dr Anderson’s comments met the highest ethical, professional and legal standards. This of course does not entail a positive finding that Dr Anderson’s comments did not meet those standards. Rather, given the paucity of evidence on this topic from at least the Union parties, I am unable to determine the issue one way or the other. It follows that I cannot be satisfied that Dr Anderson’s comments were exercises of the intellectual freedom enshrined in the 2013 Agreement and 2018 Agreement (as relevant). It also follows that I am not satisfied that Dr Anderson’s comments did not constitute misconduct or serious misconduct on the basis that they were exercises of the intellectual freedom.

22 The only question then remaining is whether it has been shown by the Union parties that Dr Anderson’s fifth comments did not constitute serious misconduct for some other reason such that his termination by the University was in breach of cl 384. For the reasons explained by the Full Court in FCAFC 1 at [220], equivalent questions do not arise in respect of the first and final warnings (and the comments to which they relate) because by the terms of cl 384(d) the taking of disciplinary action other than termination depends on the reasonable satisfaction of the University’s that the staff member had engaged in misconduct, rather than such misconduct having occurred in fact. It was not argued by the Union parties that Professor Garton was not reasonably satisfied that the first, second, third and fourth comments constituted misconduct: FCA 1 at [147]-[148].

23 The Union parties submitted on remitter that the fifth comments did not constitute serious misconduct even if, as I have found, it has not been demonstrated they were not an exercise of the intellectual freedom. This submission relied on the following dictum from Allsop CJ at [17] in FCAFC 1:

If it be the case that what has occurred can be characterised as the exercise or attempted exercise of the freedom or one of the rights, but one that was not in accordance with the standards required by cl 317, the question of any Misconduct would have to be assessed by reference to the failure to exercise the freedom or rights in accordance with the highest standards. The departure from those standards would be the conduct from which any judgment of Misconduct is to be made. The above enquiry should not be approached mechanically by concluding that the freedom or right in cl 315 was not validly exercised under cl 317 and so the conduct can be judged simply by reference to the Code of Conduct, ignoring otherwise cll 315 and 317. If the conduct is properly characterised as an exercise or attempted exercise of the freedom or right, but not at the highest standards, the vice of the conduct is in the departure from those standards, which may or may not be Misconduct, Serious or otherwise.

The Union parties argued that in making the fifth comments Dr Anderson was intending to exercise his intellectual freedom in accordance with the standards required by cll 315-317 and that any breach of those standards was not deliberate. Accordingly, it was said that the vice of Dr Anderson’s conduct did not rise to the level of serious misconduct and that the University’s power to terminate was not enlivened.

24 I do not accept this submission for three reasons. First, I do not read Allsop CJ’s remarks as intended to limit the assessment of misconduct or serious misconduct in cases such as these to the extent to which conduct has fallen below the cl 317 standards. Rather, that is but one factor in considering whether conduct constitutes misconduct or serious misconduct. Secondly, even if Allsop CJ’s remarks are to be read in that way, it is an essential premise of the Union parties’ submission that there be identified standards from which Dr Anderson’s departure can be assessed. As I have explained, no such standards were identified by the Union parties so it is not possible meaningfully to assess the extent to which the fifth comments have fallen below them. Thirdly, it must be brought to account that each of Dr Anderson’s comments have not been found to have been exercises of the intellectual freedom. The consequence of that conclusion is that the first and final warnings were properly issued by the University such that the second and fourth comments were made in breach of lawful directions. Considered in that light, the University’s submission that the fifth comments constituted repeated and deliberate defiance by Dr Anderson of lawful and reasonable directions is persuasive. For these reasons, I reject the submission that the fifth comments did not constitute serious misconduct. It follows that the Union parties’ attack on the termination of Dr Anderson’s employment must fail.

25 I would make the following orders:

(1) Leave be granted to the Appellant to file a Further Amended Notice of Appeal in the form handed up on 16 August 2023.

(2) The appeal be allowed.

(3) Orders 1, 3, 5 and 7 made on 22 November 2022 and Orders 1 and 2 made on 5 June 2023 be set aside and in place thereof it be ordered that:

(a) The Applicants’ application be dismissed.

(4) If any party wishes to seek an order as to costs:

(a) that party is to file, within 7 days, written submissions on costs of no more than 5 pages together with any evidence on which it wishes to rely;

(b) any other party may file, within a further 7 days, written submissions in response of no more than 5 pages together with any evidence on which it wishes to rely; and

(c) the question of costs will be decided on the papers, unless the Court is of the view that an oral hearing is required.

I certify that the preceding twenty-five (25) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

Associate:

Dated: 17 May 2024

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION

26 I have had the benefit of reading the draft reasons of Perram J and Kennett J. I will adopt the defined terms in Kennett J’s judgment and gratefully adopt the outline of facts; the detailing of the procedural history (including the nature of the case advanced on remitter); and the description of the issues in the present appeal.

27 As would be evident from Kennett J’s reasons, this case has been a procedural mess. The lack of clarity in the pleadings and the submissions below has caused much confusion, and the primary judge did not receive the assistance his Honour was entitled to expect from the University parties below.

28 Subject to what follows, I generally agree with Kennett J but, to the extent I disagree, such disagreement is determinative. This is because I agree with Perram J’s conclusion, so far as it goes, that the Union parties failed to discharge their onus of proof. Accordingly, I agree that the appeal should succeed, and the orders proposed by Perram J ought to be made.

29 My reasons for reaching that conclusion follow.

30 In FCA 1, the primary judge dismissed the proceeding. In doing so, his Honour made the point (at [133]) that cl 315 contains requirements which must be satisfied before conduct could constitute the exercise of intellectual freedom and the clause contains what might be referred to as limitations. Hence the “right” is to engage in the “free and responsible pursuit of all aspects of knowledge and culture”. If the pursuit of knowledge in a particular case was not “responsible”, the pursuit would not fall within cl 315(a).

31 It followed, as the Full Court accepted, there are “in-built qualifications” (FCAFC 1 (at [256])) on the right of intellectual freedom imbedded in both cl 315 itself as well as within cl 317. This qualified right was the right that the Union parties, in their case in chief, were asserting was being exercised at relevant times by Dr Anderson. It necessarily followed that the Union parties bore the onus and hence were obliged to prove that Dr Anderson exercised the right of intellectual freedom in a way which was both “responsible” (cl 315), and in accordance with the “highest ethical, professional and legal standards” (cl 317): FCAFC 1 (at [7], [128] and [269]). This reflects the fact that the University only contravened s 50 of the FW Act if Dr Anderson’s exercise of the right, as a matter of objective fact, was in accordance with the in-built qualifications: FCAFC 1 (at [154] and [269]). This was the position irrespective as to what “forensic logic” or procedural fairness required by way of pleading to put the opposing party on notice of the real issues at the hearing: FCAFC 1 (at [182]).

32 As Kennett J has explained, the difficulty that arose in this case is that despite submitting in writing that Dr Anderson’s comments did not meet the necessary standard and the primary judge making it plain he would need each departure from the standard to be articulated and explained, the University parties below did not respond by engaging in this task. This placed the primary judge in an unenviable position, and while it rendered explicable why his Honour expressed himself in the way he did about the “failure to establish a breach by Dr Anderson”, it did have the effect, in my respectful opinion, of diverting attention away from considering whether the Union parties established that the third and fifth comments could possibly be characterised as constituting a responsible exercise of intellectual freedom in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

B THE THIRD AND FIFTH COMMENTS IN CONTEXT

33 The full details are set out in Kennett J’s reasons, but it is worth outlining some important contextual facts relevant to the third and fifth comments.

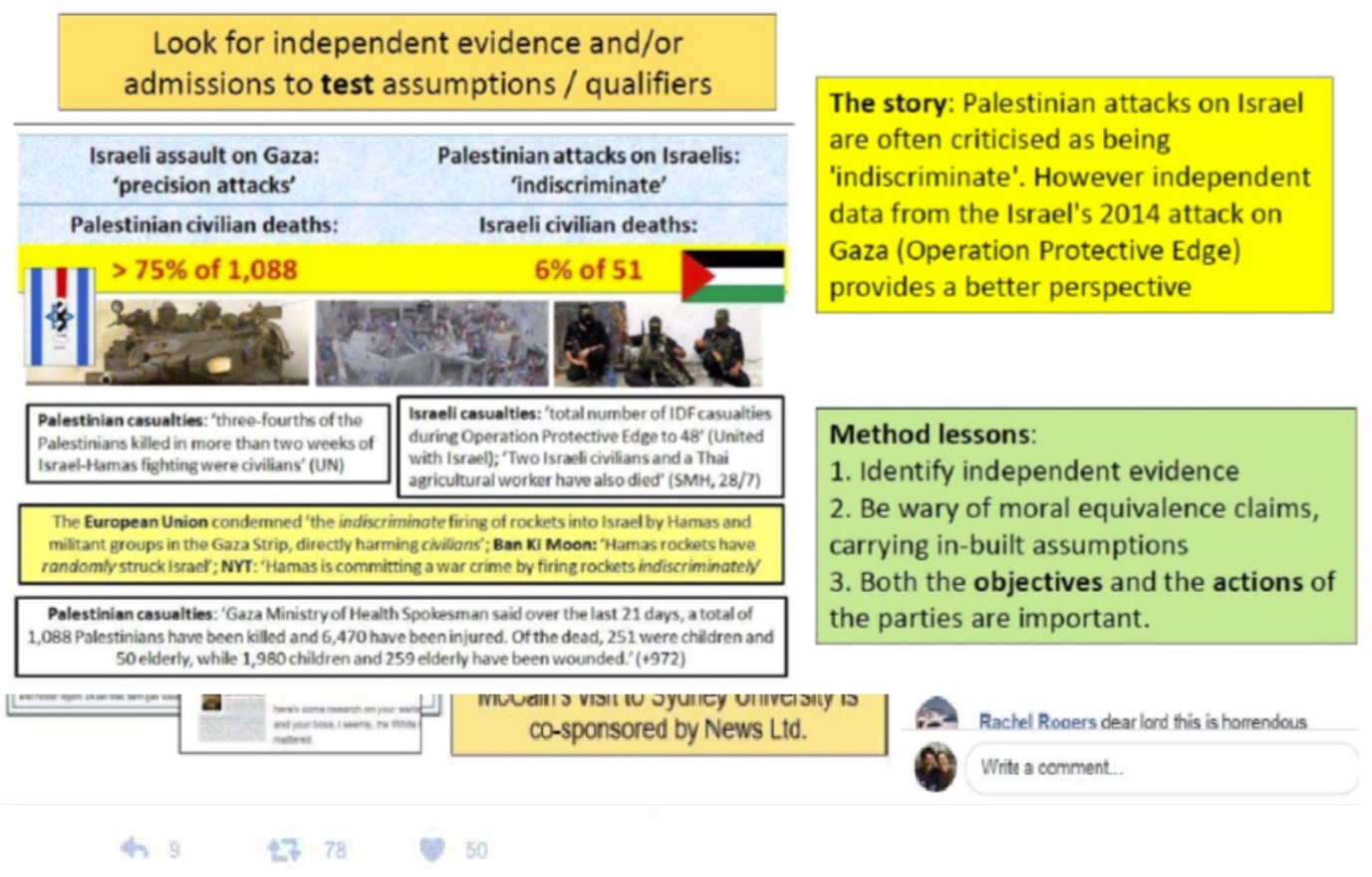

34 The third comments involved the posting to a Facebook account of a PowerPoint presentation entitled “Reading Contemporary Controversies” at a seminar for the “Centre for Counter Hegemonic Studies”: FCA 1 (at [41]). One slide, with the heading “Look for independent evidence and/or admissions to test assumptions / qualifiers” (emphasis in original), made various assertions, which are unnecessary to detail, but included a superimposed graphic of the national flag of the State of Israel rent down the middle exposing the swastika.

35 In his affidavit, Dr Anderson described the image of the desecrated flag as “an evocative image consistent with my published view that Zionist racial ideology and racialised violence … was reminiscent of the murderous, racialised pogroms of Nazi Germany”. He also gave evidence that the slide was “version two” of an infographic he had prepared in 2015 and claimed that in adapting it for use in 2018, the swastika “had become barely visible and not central to the meaning of the graphic, so I forgot about it”: FCA 2 (at [45]).

36 By August 2018, Dr Anderson had posted to his Facebook account the lunch photograph (featuring one of those photographed wearing a jacket with a patch bearing an emblem of Ansar Allah, a group active in the central parts of Yemen (FCA 1 (at [220])) with the following offensively antisemitic slogans in Arabic: “Death to Israel”, “Curse the Jews” and “Victory to all Islam”) which, following adverse publicity, was followed by the fourth comments and the University directing him to remove the lunch photograph and his comments from his Facebook page. He did not do so. Instead, he sent an email stating that he “never respond[s] favourably to secret demands and threats”: FCA 1 (at [49]).

37 On 10 August 2018, the University sent Dr Anderson a letter raising allegations concerning the lunch photograph, the fourth comments and his refusal to comply with the direction to remove the comments. Dr Anderson doubled down and then, on 19 October 2018, he received the final warning, advising of the outcome of the earlier misconduct allegation and stating (FCA 1 (at [69])):

It is of significant concern to me that you have repeated conduct in respect of which you received a formal warning.

I am satisfied that Allegations 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 are substantiated and Allegation 5 is partially substantiated, and that your breaches of the Code of Conduct - Staff and Affiliates (Code of Conduct) and Public Comment Policy amount to Misconduct.

I am satisfied that throughout this process, you were afforded a reasonable opportunity to respond to the allegations.

This letter constitutes a final warning that you must appropriately discharge your obligations pursuant to your contract of employment with the University, the Enterprise Agreement, the Code of Conduct and the Public Comment Policy going forward.

I specifically remind you of the requirement to exercise good and ethical judgment in any public comment, demonstrate professionalism (including in public comment) and exercise appropriate restraint. I also remind you of your obligations to act fairly and reasonably, and treat all relevant persons, including staff and members of the public, with respect, impartiality, courtesy and sensitivity.

Should any further incidents of this nature occur, the University will rely upon the 2 August 2017 letter, and this final warning letter to determine any appropriate further Disciplinary Action, up to and potentially including the termination of your employment …

(Emphasis in original)

38 The final warning also addressed a new issue, namely posts of which the University had become aware. The letter stated (FCA 1 (at [70])):

[T]he University is aware of other posts made on social media accounts in your name which raise serious concerns about your willingness to comply with your employment obligations. In particular, I refer to a Facebook Post of a presentation in a “Reading Controversies” Seminar delivered for the Centre for Counter Hegemonic Studies. This post was made on 23 April 2018 and shows a cropped Swastika superimposed over the Israeli flag (see Annexure C to this letter).

Given the period of time which had elapsed from when you had made the post and when it was referred to the University, a decision was made not to include it in the allegations. In the circumstances, the University will not raise this post with you formally. However, in my view, a reasonable person would regard the superimposition of a cropped Swastika over the Israeli flag as offensive.

Please immediately add a disclaimer in any medium in which this post appears that the presentation is not connected in any way with the University of Sydney and remove any references to the University of Sydney from the relevant posts.

You must also make it clear in any future posts relating to the Centre for Counter Hegemonic Studies that it is not associated with, or endorsed by, the University of Sydney in any way, consistent with guideline (e) of the Public Comment Policy.

I have separately written to the NTEU in relation to the matters that they have raised on your behalf. I confirm that you are able to confirm the fact of the allegations, but not the substance of them. I also confirm that you are required to keep confidential the contents of this letter, including on social media. …

39 This direction required Dr Anderson to “add a disclaimer in any medium in which this post appears that the presentation is not connected in any way with the University of Sydney and remove any references to the University of Sydney from the relevant posts” (disaffiliation direction).

40 On 19 or 20 October 2018, in defiance of the disaffiliation direction, Dr Anderson reposted the slides to his Facebook and Twitter accounts: FCA 1 (at [76]–[78]), being the fifth comments, without disclaimer or disaffiliation: FCA 1 (at [267]). On 26 October, Professor Garton wrote to Dr Anderson raising further allegations of potential misconduct, to which Dr Anderson responded by email on the same day asserting that he rejected the University’s position as detailed in the final warning and that he did not intend to respond further: FCA 1 (at [79]–[83]).

41 On 3 December 2018, Professor Garton notified Dr Anderson by letter that the allegations contained in the 26 October letter were substantiated and were regarded as constituting serious misconduct. Consequently, Professor Garton suspended Dr Anderson from duty and proposed to terminate his employment: FCA 1 (at [88]). The response of Dr Anderson was again defiant, publishing posts on his Facebook and Twitter accounts on 4 and 5 December 2018 concerning his suspension, including part of the text of Professor Garton’s letter (despite a direction that he refrain from posting University letters on social media): FCA 1 (at [89]).

42 On 11 February 2019, the University terminated Dr Anderson’s employment, taking into account the two written warnings, including the final warning, which do not refer to the third comments: FCA 2 (at [66]).

C THE REASONING BELOW AS TO THE THIRD AND FIFTH COMMENTS

43 As to the third comments, while accepting the slide would be “offensive to many people”, the primary judge found their making constituted the exercise intellectual freedom: FCA 2 (at [49]–[50]). His Honour found, however, that it did not rise to the level of constituting harassment, vilification or intimidation: FCA 2 (at [49]). It was by this path of reasoning that the primary judge found the “University did not establish any breach of any standard which might have engaged cl 317 of the 2018 Agreement”: FCA 2 (at [49]).

44 As to the fifth comments, his Honour had initially found that the fifth comments constituted an “assertion of an unfettered right to exercise what [Dr Anderson] considered to be intellectual freedom” and conveyed that Dr Anderson “could post such material if he wanted and the University had no right or entitlement to prevent him from doing so”: FCA 1 (at [255]). His Honour also found in circumstances where Dr Anderson had refused to follow lawful directions (and where it would be reasonable to infer that he would continue to refuse to follow lawful directions), it was reasonably open for Professor Garton to conclude that the making of the fifth comments was such as to constitute “serious misconduct”: FCA 1 (at [268]).

45 In FCAFC 1, it was then held (at [285]–[287]) that given the way the case had been pleaded and run, the primary judge was required to determine the basis on which the University in fact terminated Dr Anderson’s employment such that if it was correct the University terminated Dr Anderson’s employment without notice on the basis of conduct which constituted the exercise of the right in accordance with the in-built qualifications, the decision to terminate necessarily miscarried.

46 On remittal, despite what the primary judge had initially found in FCA 1, his Honour considered himself constrained to conclude that the fifth comments did constitute an exercise of academic freedom. It is worth setting out his Honour’s reasoning in this regard (FCA 2 (at [52]–[53])):

[52] I have set out earlier what the plurality stated [in FCAFC 1] at [266]. It is repeated for convenience:

[I]f: (a) an exercise of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315 and 317 cannot be misconduct at all (which is the case), and (b) posting the PowerPoint presentation initially was an exercise of that right in accordance with cll 315 and 317 (an issue of fact the Court must determine for itself on the remittal), then:

(1) Dr Anderson would be acting lawfully in wanting to “express his view that he had a right to post material of that kind if he wished” and would be right to insist he had the right to do so “without censure”. His self-described “assertion of my intellectual freedom” would be lawful. Contrary to J [256], these factors would not indicate that the conduct was not an exercise of the right of intellectual freedom;

(2) also contrary to J [256], it was not necessary for Dr Anderson to prove or explain what course he was teaching at the time that made it relevant to re-post the PowerPoint presentation. The right of intellectual freedom is not confined to public comments about the content of courses being taught or taught at the time of the public comment; and

(3) if Dr Anderson intended the re-posting of the PowerPoint presentation to be “an assertion of an unfettered right to exercise what he considered to be intellectual freedom” and was being “deliberately provocative” in conveying that Dr Anderson “could post such material if he wanted and the University had no right or entitlement to prevent him from doing so”, he would have been correct and entitled to make that point to the University by the re-posting of the material.

[53] Given that (a) and (b) in the chapeau of [266] are both satisfied, it necessarily follows that the conclusions of the plurality in (1), (2) and (3) are applicable and that Dr Anderson was acting lawfully when he re-posted the Gaza Graphic as a means of asserting his right to intellectual freedom. The University did not establish any breach by Dr Anderson of a standard which might engage cl 317 of the 2018 Agreement.

(Emphasis added)

47 Hence it can be seen the primary judge’s finding (FCA 2 (at [49])) that the initial posting of the image (by the third comments) was an exercise of academic freedom in accordance with the in-built qualifications, informed by his Honour’s separate conclusion as to the fifth comments. In any event, his Honour again reasoned that the “University did not establish any breach by Dr Anderson of a standard which might engage cl 317 of the 2018 Agreement”: FCA 2 (at [53]).

D ONUS AND THE THIRD AND FIFTH COMMENTS

48 As noted above, because of the way in which the University parties advanced their submissions, it is unsurprising his Honour was not directed to the need to make a determination as to whether the Union parties had discharged their onus of establishing Dr Anderson had, with regard to these comments, exercised the right of intellectual freedom in a way which was both “responsible” (cl 315) and in accordance with the “highest ethical, professional and legal standards” (cl 317): FCAFC 1 (at [7], [128] and [269]).

49 These qualifications must be given both context and content. Assessment as to what is responsible, like what is reasonable, is open-textured and value-laden; they are standards predicated on “fact-value complexes, not on mere facts”: see Russell v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2023] FCA 1223 (at [325]), quoting a former Challis Professor of Jurisprudence and International Law at the University, Professor Julius Stone.

50 The assessment and evaluation of whether conduct is of a nature that is consistent with the exercise of the right as qualified is necessarily informed by the objects and functions of the intellectual community constituted by the University. Section 6 of the University of Sydney Act 1989 (NSW) relevantly provides:

6 Object and functions of University

(1) The object of the University is the promotion, within the limits of the University’s resources, of scholarship, research, free inquiry, the interaction of research and teaching, and academic excellence.

(2) The University has the following principal functions for the promotion of its object—

(a) the provision of facilities for education and research of university standard,

(b) the encouragement of the dissemination, advancement, development and application of knowledge informed by free inquiry,

(c) the provision of courses of study or instruction across a range of fields, and the carrying out of research, to meet the needs of the community,

(d) the participation in public discourse,

(e) the conferring of degrees, including those of Bachelor, Master and Doctor, and the awarding of diplomas, certificates and other awards,

(f) the provision of teaching and learning that engage with advanced knowledge and inquiry,

(g) the development of governance, procedural rules, admission policies, financial arrangements and quality assurance processes that are underpinned by the values and goals referred to in the functions set out in this subsection, and that are sufficient to ensure the integrity of the University's academic programs.

(Emphasis added)

51 As the University parties correctly submit, for present purposes, it is sufficient to observe that:

(1) a “responsible” exercise of the right requires at least that public debate be about issues and ideas, rather than ad hominem and intemperate attacks;

(2) highest professional standards are those which pursue “academic excellence” and include, at a minimum, evidence-based analysis applying the scientific method; and

(3) highest legal standards require at least that there be compliance with lawful and reasonable directions.

52 When regard is had to the in-built qualifications and one gives them content (including by reference to the objects and functions of the University), I confess I am unable to see how the making of the third and fifth comments could be characterised as being responsible and consistent with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

53 As to the third comments, I am conscious the primary judge directed himself to considering the observations of Jagot and Rangiah JJ and noted (FCA 2 (at [41])):

[41] … the plurality of the Full Court observed at [267] that it is the Israeli flag superimposed with the swastika which is the issue. The Full Court observed that “[e]verything else in the PowerPoint presentation involves the expression of a legitimate view, open to debate, about the relative morality of the actions of Israel and Palestinian people”. The plurality said:

[267] Consider the PowerPoint presentation in more detail. It is the Israeli flag superimposed with the swastika which is the issue. Everything else in the PowerPoint presentation involves the expression of a legitimate view, open to debate, about the relative morality of the actions of Israel and Palestinian people. Dr Anderson is making a public comment asserting that the concept of moral equivalence between Israel and Palestinian people who attack Israel is false, in part, because of an asserted higher number of deaths of civilian Palestinians in Gaza from purportedly “precision attacks” by Israel compared to an asserted far lower number of deaths of people in Israel from purportedly “indiscriminate” attacks by Palestinians. He is including Israel within a long history of colonial exploitation by one political entity over another weaker entity or people. It does not matter whether this comparison may be considered by some or many people to be offensive or insensitive or wrong. As discussed, offence and insensitivity cannot be relevant criteria for deciding if conduct does or does not constitute the exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315 and 317.

[268] What then of the swastika superimposed over the Israeli flag? That is deeply offensive and insensitive to Jewish people and to Israel. It may involve an assertion of the very kind of false moral equivalence (comparing Israel to Nazi Germany) against which Dr Anderson is advocating in the PowerPoint presentation. Again, however, the relevant issue cannot be the level of offence which the conduct generates or the insensitivity which it involves. The issue is only whether the conduct involves the exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315 and 317. Whether this part of the PowerPoint presentation operates to take the otherwise legitimate expressions of intellectual freedom elsewhere in the PowerPoint presentation outside of the scope of cll 315 and 317 is a question of fact which must be determined on the whole of the evidence. For example, did the evidence support an inference that the superimposition of the swastika over the flag of Israel was a form of racial vilification intended to incite hatred of Jewish people? That is a matter which may only be determined on the whole of the evidence as part of the remittal of the matter.

[269] Accordingly, the primary judge was required to decide, as a matter of objective fact by reference to the evidence of all the relevant circumstances, whether each or any of the instances of Dr Anderson’s impugned conduct (excluding the lunch photo) constituted an exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315-317 of the 2018 agreement (or, if applicable, the equivalent provisions of the 2013 agreement). This included consideration of whether the conduct did or did not involve harassment, vilification or intimidation or the upholding of the principle and practice of intellectual freedom in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

(Emphasis added)

54 Although I accept that the “relevant issue [that is, the only issue] cannot be the level of offence which the conduct generates or the insensitivity”, the level of offence can, of course, be relevant to the objective characterisation of the comments. For my part, the posting of this image, which is self-evidently offensive (and obviously disturbing to a section of the University community) could not amount to an exercise of intellectual freedom which was both “responsible” (cl 315) and in accordance with the “highest … standards” (cl 317) – a fortiori where Dr Anderson conceded the offensive image was not even important nor “central to the meaning of the graphic” and was so peripheral to whatever point he was seeking to make that Dr Anderson “forgot” about the image.

55 For completeness, I should note that given the way the case was advanced by the University below, senior counsel accepted it was not open on appeal for the University to advance the case that the superimposition of the swastika over the flag of the State of Israel was a form of vilification in that it was apt to incite hatred toward, revulsion of, or serious contempt for, a group of people (whatever be the underlying merits of that argument) (T5.15).

56 As to the fifth comments, in the event the third comments are not an exercise of the right in accordance with cll 315 and 317, the foundation for his Honour considering himself constrained by what was said in FCAFC 1 (at [266]) falls away.

57 The making of the fifth comments constituted a wilful defiance of the disaffiliation direction, which direction was lawful and reasonable. Any suggestion the disaffiliation direction was unlawful or unreasonable on the basis that it conflicted with the exercise of academic freedom not only presupposes that in making the fifth comments, Dr Anderson was exercising such freedom reasonably (which he was not) but, moreover, that it was not open for the University to disclaim the attribution of Dr Anderson’s views to the University. As the University points out, this is acknowledged in the report by the Hon R S French, Report of the Independent Review of Freedom of Speech in Australian Higher Education Providers (Report, 19 March 2019) (at 126): “[s]o far as extra-mural speech by academic staff is concerned, a university or other higher education provider is entitled to ask that they disclaim any attribution of their views to the university”.

58 In summary, in making the third and fifth comments, Dr Anderson was not exercising the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with the 2018 Agreement. In any event, by reason of the lack of assistance given to the primary judge by the University parties below, I agree with Perram J that error is established because his Honour did not turn his mind to whether Dr Anderson’s case positively satisfied him that the comments were made in a manner consistent with the in-built qualifications (FCAFC 1 (at [256])) on the right of intellectual freedom imbedded within cll 315 and 317.

E PROPOSED ORDERS

59 Subject to the above, I agree with the reasons of Perram J and the orders proposed by his Honour.

I certify that the preceding thirty-four (34) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

Dated: 17 May 2024

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

KENNETT J:

INTRODUCTION

60 The respondents in this appeal, the National Tertiary Education Industry Union (NTEU) and Dr Tim Anderson (the Union parties), filed an originating application on 15 April 2019 seeking:

(a) declarations that the present appellant, the University of Sydney (the University), and Professor Stephen Garton (the appellant in a related appeal (NSD 1130 of 2022)), (together the University parties), along with Professor Annamarie Jagose, had contravened provisions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the FW Act);

(b) an order for reinstatement of Dr Anderson;

(c) an order for compensation to be paid to Dr Anderson; and

(d) pecuniary penalties.

61 The primary judge delivered judgment on 26 November 2020, dismissing the proceeding: [2020] FCA 1709; 302 IR 272 (FCA 1).

62 The Union parties appealed. The Full Court published reasons on 31 August 2021 ([2021] FCAFC 159; 309 IR 159) (FCAFC 1), followed by further reasons and orders on 21 October 2021 ([2021] FCAFC 184) (FCAFC 2). It made orders joining Professors Jagose and Garton as respondents and dismissed the proceeding as against the former. It otherwise remitted the matter to the primary judge, to be determined on the basis of the existing evidence.

63 The primary judge held a further day of hearing on 28 June 2022 and published reasons on 27 October 2022 (FCA 2), followed by orders giving effect to those reasons on 22 November 2022 (FCA 3). His Honour held that the University parties had contravened various provisions of the FW Act and made declarations accordingly.

64 Each of the judgments and reasons mentioned so far is discussed in more detail below.

65 Following another day of hearing, the primary judge published reasons on the remaining questions of relief on 29 May 2023 ([2023] FCA 537) and then made final orders, giving effect to those reasons, on 5 June 2023 (FCA 4). His Honour dismissed the claims for damages and pecuniary penalties, ordered reinstatement of Dr Anderson (with some consequential orders) and stayed the reinstatement order pending the outcome of this appeal.

66 The University filed a notice of appeal from the orders in FCA 3 on 4 July 2023. The notice of appeal was later amended so as to challenge FCA 4 as well. Professor Garton also appealed against FCA 3.

67 The Union parties reached an agreement with Professor Garton and proposed at the commencement of the hearing that his appeal should be allowed. In response to concerns expressed by the Court as to whether an appeal could be allowed solely on the basis of the parties’ consent, it was agreed that the matter should be remitted to a single judge who could, in the original jurisdiction, make consent orders giving effect to the parties’ agreement. The matter was remitted and consent orders were made on 5 September. Shortly afterwards Professor Garton’s appeal was dismissed as moot. Accordingly, only the University’s appeal remains before the Court.

OUTLINE OF THE FACTS

68 Dr Anderson commenced employment at the University in 1998 and was appointed to an ongoing Associate Lectureship in the Political Economy Group, within the Department of Economics, in January 1999. He became a Lecturer in 2000 and a Senior Lecturer in 2008. The issues in the proceeding arise out of certain comments that he made on social media platforms between April 2017 and October 2018.

69 The University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2013-2017 (the 2013 Agreement) had come into effect on 16 January 2014. A later agreement, the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2018-2021 (the 2018 Agreement) commenced on 27 April 2018. The relevant provisions of these agreements were the same.

The first comments: April – May 2017

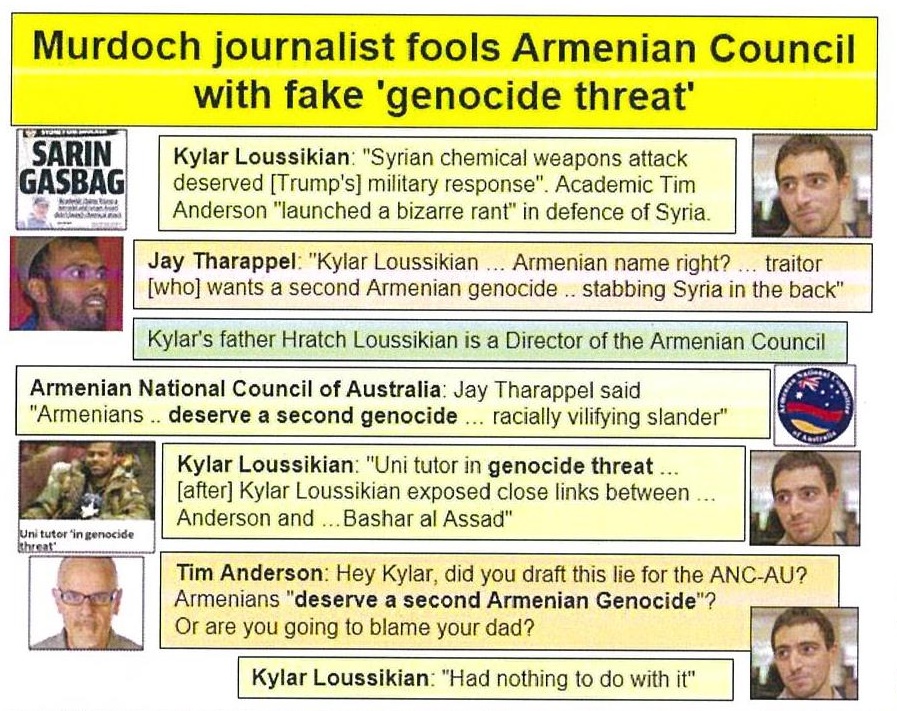

70 On 8 April 2017 Dr Anderson tweeted a picture of the then United States President, Donald Trump, and his two predecessors, Presidents Obama and George W Bush, with the words “Masterminds of Middle East terrorism”. This followed a missile attack on a place in Syria the previous day, ordered in response to what was reported as a gas attack that had occurred in that country. The Daily Telegraph (the Telegraph), a tabloid newspaper, published a story on its front page on 11 April 2017, under the headline “Sarin Gasbag”, criticising Dr Anderson in relation to his views on this subject. The story appeared under the byline of Kylar Loussikian.

71 Mr Jay Tharappel, then a PhD student supervised by Dr Anderson and a tutor in courses that Dr Anderson taught, made comments on Twitter (as the social media platform ‘X’ was then known) about Mr Loussikian: “Armenian name right? … traitor [who] wants a second Armenian genocide … stabbing Syria in the back”. The logic of this critique does not need to be explored. The Telegraph responded with two articles: “Sydney University tutor investigated after racially-charged attack on Daily Telegraph reporter of Armenian descent” (11 April 2017) and “Assad situation for Uni loonies” (12 April 2017). The latter article included comments critical of Mr Tharappel’s position from the Armenian National Council of Australia.

72 A further article appeared in the Telegraph on 20 April 2017, written by journalist Rick Morton, headed “Assad defender condemns diggers for Syria airstrike murder”. This article took issue with comments by Dr Anderson about an air strike in Syria in which Australian Air Force personnel had been involved with the US Air Force.

73 On 4 May 2017, Dr Anderson tweeted “Murdoch press fabricates ‘genocide threat’ story in attempt to intimidate anti-war academics”, with the following graphic attached:

74 To a comment on this tweet suggesting “maybe English is not their first language”, Dr Anderson responded “Kylar is fluent in lying english”. He added the 4 May tweet to his Facebook page the next day.

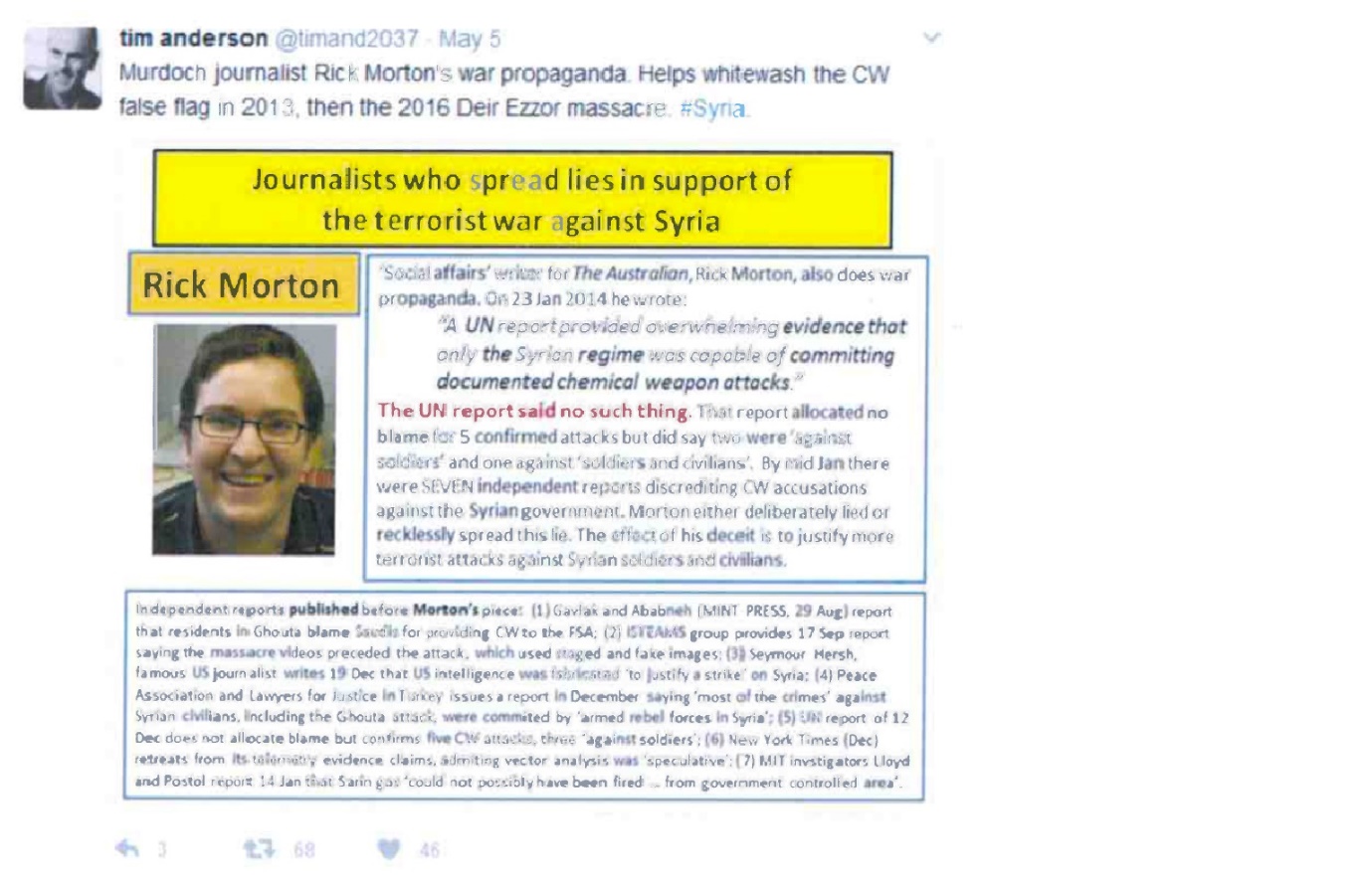

75 Dr Anderson was active on Twitter on 5 May 2017. First, he published a graphic comparing Mr Tharappel’s comments with claims in the Telegraph article on 12 May. Next, he published the following in relation to Mr Morton:

76 There then occurred an exchange of messages between Dr Anderson and Mr Morton, which Dr Anderson sought to capture in the following tweet:

77 Mr Morton responded “Tim, you’ll be hearing from the lawyers”, to which Dr Anderson’s reply was “Yellow journalist Rick Morton runs off crying to his lawyers, when the tables are turned”. Dr Anderson returned to the theme the next day, tweeting:

Covering up a real massacre with lies: “condemns diggers”, “Australians should be considered murderers”. Great work Rick Morton.

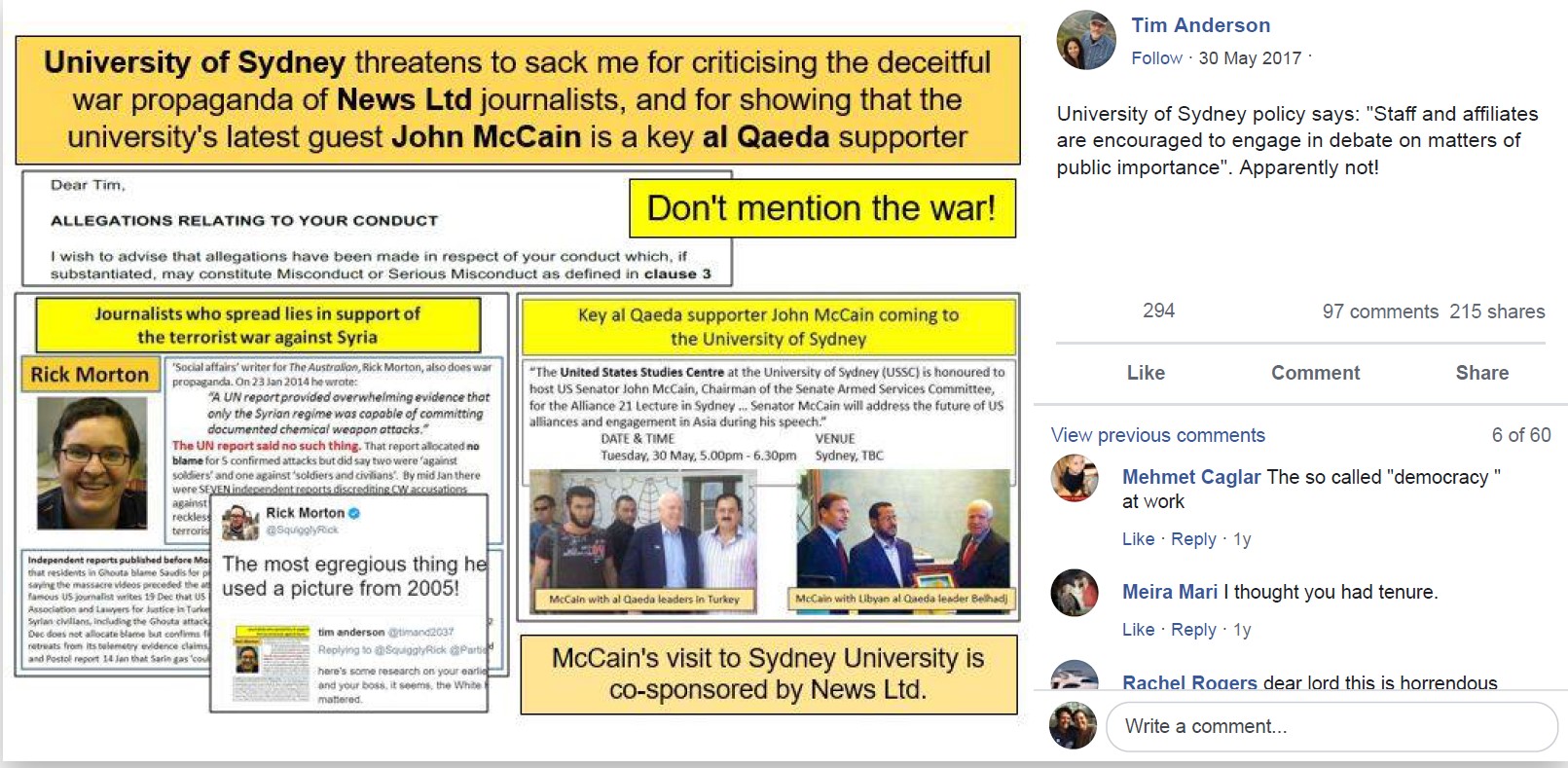

78 On 10 May 2017 Dr Anderson took up a different topic: a proposed visit by US Senator John McCain to the United States Studies Centre at the University. He tweeted the following:

79 The tweets and posts on 4, 5, 6 and 10 May 2017 are the “first comments”.

Disciplinary proceedings and the second comments: May – August 2017

80 On 30 May 2017, Dr Anderson received a letter from Professor Jagose containing allegations that his conduct in making the first comments constituted a breach of the University’s Code of Conduct – Staff and Affiliates and Public Comment Policy. The letter said that, if substantiated, the allegations could amount to misconduct or serious misconduct and disciplinary action could be taken pursuant to the 2013 Agreement, potentially including termination of his employment. It outlined Dr Anderson’s opportunity to respond. The letter also said that the matters raised in it were confidential and “directed” Dr Anderson not to disclose or communicate its contents (or the allegations or information relating to them) to anyone except his family, support person or professional adviser.

81 Dr Anderson’s response to this direction, which came on the same day, was to defy it by publishing the following on Facebook and Twitter (the second comments):

82 He also:

(a) sent an email to colleagues in the Department of Political Economy on 31 May 2017 headed “Anti-war academic gagged at Sydney Uni”, including extracts from Professor Jagose’s letter and alleging collusion with the Telegraph; and

(b) sent an email to Professor Jagose on 6 June 2017 alleging bias and asking her to step aside.

83 One result of these actions was a letter to Dr Anderson from Professor Garton, dated 26 June 2017, containing further allegations against him in relation to his comments on Professor Jagose and the disciplinary process.

84 Dr Anderson responded to both sets of allegations, in writing, on 5 July 2017. On 2 August 2017 Professor Garton issued him with a written warning (the first warning).

The third comments: April 2018

85 On 21 April 2018 Dr Anderson gave a PowerPoint presentation during a seminar entitled “Reading Controversies”. It included a slide referred to as the Gaza graphic, which he adapted from a presentation he had prepared in 2015. On 23 April 2018 he posted the Gaza graphic to his Facebook account, as follows (the third comments):

86 It seems that the 21 April 2018 seminar was organised by or for the Centre for Counter Hegemonic Studies (CCHS), an international grouping of academics with which Dr Anderson was affiliated. The post to Dr Anderson’s Facebook page including the Gaza graphic referred to the CCHS and also identified Dr Anderson as affiliated with the University (including in that Dr Anderson’s Facebook Account featured references to employment at the CCHS and University under the heading “About Tim Anderson”).

87 Although it is not easy to see in the reproduction above, the Gaza graphic includes an image of the Israeli flag in which the middle of the flag is ripped downwards to reveal part of the flag of Nazi Germany including the swastika. Dr Anderson gave evidence that this particular image was retained from the earlier (2015) version of the graphic and had become barely visible, so that he “forgot about it”. He described the altered Israeli flag in his affidavit as “an evocative image consistent with my published view that Zionist racial ideology and racialized violence … was reminiscent of the murderous, racialized pogroms of Nazi Germany.”

The fourth comments and further disciplinary proceedings: July – August 2018

88 On 22 July 2018 Dr Anderson posted on his Facebook account a photograph taken at a lunch in Beijing (the lunch photograph). The photograph shows five people sitting at a table in a restaurant. It is unremarkable except that one of the people (Mr Tharappel) is wearing a shirt featuring a shoulder patch with a rectangular emblem and some Arabic script. The emblem is that of Ansar Allah, an Islamist group based in Yemen. The Arabic script includes words which translate into English as “Death to Israel”, “Curse the Jews” and “Victory to all Islam”.

89 A video news story concerning the lunch photograph by a Channel 7 reporter was published by 7NEWS Sydney on 2 August 2018. On 3 August 2018 Dr Anderson posted on Facebook and Twitter a link to the item, including the following comment (the fourth comments):

Colonial media promotes ignorance, apartheid and war. Channel 7’s Bryan Seymour accuses Indian Australian student of “racism” for siding with #Yemen and other Arab states against #ApartheidIsrael. Also lies about those in solidarity with #Korea #DPRK.

90 Later on 3 August, the University sent Dr Anderson a letter directing him to remove the lunch photograph and his comments from his Facebook page. He did not do so. Instead, he sent Professor Jagose an email stating that he “never respond[s] favourably to secret demands and threats”.

91 On 10 August 2018, the University sent Dr Anderson a letter from Professor Jagose raising allegations concerning the lunch photograph, the fourth comments and his refusal to comply with the direction to remove those comments. Dr Anderson responded to these allegations in writing on 22 August 2018.

The final warning, the fifth comments, suspension and termination: October 2018 – February 2019

92 On 19 October 2018, Dr Anderson was notified by Professor Garton that the allegations arising from the lunch photograph had been substantiated and issued with what was described as a “final warning” (the final warning). The letter included:

This letter constitutes a final warning that you must appropriately discharge your obligations pursuant to your contract of employment with the University, the Enterprise Agreement, the Code of Conduct and the Public Comment Policy going forward.

I specifically remind you of the requirement to exercise good and ethical judgment in any public comment, demonstrate professionalism (including in public comment) and exercise appropriate restraint. I also remind you of your obligations to act fairly and reasonably, and treat all relevant persons, including staff and members of the public with respect, impartiality, courtesy and sensitivity.

(Emphasis in original.)

93 Referring to the third comments, the letter said (the disaffiliation direction):

Please immediately add a disclaimer in any medium in which this post appears that the presentation is not connected in any way with the University of Sydney and remove any references to the University of Sydney from the relevant posts.

You must also make it clear in any future posts relating to the Centre for Counter Hegemonic Studies that it is not associated with, or endorsed by, the University of Sydney in any way, consistent with guideline (e) of the Public Comment Policy.

94 On 19 or 20 October 2018, Dr Anderson published another post on his Facebook and Twitter accounts including the Gaza graphic, still containing the small image of the altered Israeli flag (the fifth comments). He included a comment:

Revision: how to read the colonial media, and untangle false claims of “moral equivalence”. The colonial violence of #Apartheid #Israel neither morally nor proportionately equates with the resistance of #Palestine.

95 Dr Anderson also added as a comment to the Facebook post a link to an article on the website of the CCHS. That website said that Dr Anderson was the Director of the CCHS and that he was from the University of Sydney.

96 On 26 October 2018 Professor Garton wrote to Dr Anderson raising further allegations of potential misconduct.

97 On 26 or 27 October 2018 Dr Anderson sent an email to Professor Garton and others. He said that he rejected the University’s letter of 19 October and did not intend to respond further to the letter of 26 October.

98 On 3 December 2018 Professor Garton notified Dr Anderson by letter that the allegations contained in the 26 October letter were substantiated and regarded as constituting serious misconduct, he was suspended from duty and the University proposed to terminate his employment.

99 Dr Anderson published posts on his Facebook and Twitter accounts on 4 and 5 December 2018 concerning his suspension, including part of the text of Professor Garton’s letter. Professor Garton wrote to Dr Anderson about these posts on 7 December 2018. He described those posts, among other things, as “inappropriate and contrary to my previous statements that you are not to post University letters on social media”. He directed Dr Anderson “to specifically not post this letter on social media or disclose its contents more broadly”.

100 On 11 February 2019, Professor Garton sent Dr Anderson a letter terminating his employment (the termination).

THE PROCEEDINGS

101 In view of the arguments developed in the appeal, it is necessary to describe the course of the proceedings up to this point in some detail.

Relevant legal framework

102 Section 50 of the FW Act, which is a civil penalty provision, provides that a person must not contravene a provision of an enterprise agreement. It was not in doubt that the 2013 Agreement and the 2018 Agreement “applied to” the University, and therefore imposed obligations on it (cf ss 51–52). The Union parties were entitled to apply for orders in relation to a contravention of s 50 by the University in connection with the employment of the former: s 539(2), item 4. The orders that can be made if a breach of a civil penalty provision is established include an order awarding compensation and an order for reinstatement: s 545(2).

103 As noted earlier, the 2018 Agreement came into effect in April 2018, just after the making of the third comments. However, the litigation has been conducted on the basis that the relevant provisions of the 2013 and 2018 Agreements were the same. In what follows, reference is therefore made only to the provisions of the 2018 Agreement.

104 Clause 3 of the 2018 Agreement defined “misconduct” and “serious misconduct” in the following way (omitting the examples):

Misconduct means conduct or behaviour of a kind which is unsatisfactory. Examples of conduct or behaviour which may constitute Misconduct include:

(a) a breach of a Code of Conduct (as defined in this clause); or

(b) a refusal or failure to carry out a lawful and reasonable instruction.

…

Serious Misconduct means:

(a) serious misbehaviour of a kind that constitutes a serious impediment to the carrying out of a staff member’s duties or to other staff carrying out their duties; or

(b) a serious dereliction of duties.

105 Clause 3 also defined “Codes of Conduct” to include the University’s Code of Conduct – Staff and Affiliates and Research Code of Conduct as amended from time to time (the Code of Conduct).

106 Clause 13 provided that the agreement was “a closed and comprehensive agreement” which displaced any other awards and agreements. Clause 14 provided that policies, guidelines, procedures and Codes of Conduct did not form part of the agreement. However, cl 306 provided:

306 Staff must comply with the Codes of Conduct (as defined in clause 3).

107 Clauses 315 to 317 of the 2018 Agreement dealt with intellectual freedom, as follows:

315 The Parties are committed to the protection and promotion of intellectual freedom, including the rights of:

(a) Academic staff to engage in the free and responsible pursuit of all aspects of knowledge and culture through independent research, and to the dissemination of the outcomes of research in discussion, in teaching, as publications and creative works and in public debate; and

(b) Academic, Professional and English language teaching staff to:

(i) participate in the representative institutions of governance within the University in accordance with the statutes, rules and terms of reference of the institutions;

(ii) express opinions about the operation of the University and higher education policy in general;

(iii) participate in professional and representative bodies, including Unions, and to engage in community service without fear of harassment, intimidation or unfair treatment in their employment; and

(iv) express unpopular or controversial views, provided that in doing so staff must not engage in harassment, vilification or intimidation.

316 The Parties will encourage and support transparency in the pursuit of intellectual freedom within its governing and administrative bodies, including through the ability to make protected disclosures in accordance with relevant legislation.

317 The Parties will uphold the principle and practice of intellectual freedom in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

108 Clauses 254–256 of the 2013 Agreement, which are referred to in some of the material that I quote below, are the direct equivalents of cll 315–317 and were framed in identical terms.

109 Disciplinary sanctions for misconduct and serious misconduct were provided for in cl 384, as follows:

MISCONDUCT AND SERIOUS MISCONDUCT

384 Where a staff member’s Supervisor or a relevant Delegate becomes aware of allegations that the staff member may have engaged in Misconduct or Serious Misconduct:

(a) The Supervisor or relevant Delegate may undertake or arrange such preliminary investigations or enquiries as they consider necessary to determine an appropriate course of action to deal with the matter;

(b) The Supervisor or relevant Delegate may, in the case of a less serious matters [sic], seek to resolve the matter directly with the staff member concerned through guidance, counselling, warning, mediation or another form of dispute resolution;

(c) In cases other than those which are dealt with under clause 384(b), the staff member will be provided with allegations in sufficient detail to ensure that they have a reasonable opportunity to respond. The staff member will be given ten days to respond to the allegations.

(i) If the staff member admits the allegations in full, the relevant Delegate may take Disciplinary Action.

(ii) In other cases the relevant Delegate may:

(A) proceed to deal with the matter under clause 384(d); or

(B) if the Delegate considers it appropriate to do so, appoint an Investigator to investigate the allegations and report to the relevant Delegate on their findings of fact and any other matters requested by the relevant Delegate. The Investigator will determine the procedure to be followed in conducting the investigation, subject to the requirement that such procedure must allow the staff member concerned with a reasonable opportunity to respond to the allegations against them, including any new matters, or variations to the initial allegations resulting from the investigation process. The Investigator will provide a written report to the relevant Delegate and a copy to the staff member.

(d) Where the relevant Delegate is satisfied that a staff member has engaged in Misconduct or Serious Misconduct, the relevant Delegate may take Disciplinary Action against the staff member, provided that:

(i) before taking Disciplinary Action the relevant Delegate must be satisfied the staff member has been given a reasonable opportunity to respond to the allegations against them;

(ii) in any case of Disciplinary Action other than counselling, a direction to participate in mediation or an alternative form of dispute resolution or a written warning, the staff member must be given notice of the proposed Disciplinary Action and an opportunity to have the allegations examined by a Review Committee in accordance with clause 460. A request for a review must be made within five working days of receipt of notice of the proposed Disciplinary Action; and

(iii) a staff member’s employment may be terminated only if they have engaged in Serious Misconduct, as defined in clause 3 of this Agreement …

110 The Code of Conduct, in Part 1, set out “principles”, which included the following.

The Code reflects, and is intended both to advance the object of the University, namely the promotion of scholarship, research, free inquiry, the interaction of research and teaching, and academic excellence, as well as to secure the observance of its values of:

• responsibility and service through leadership in the community;

…

• integrity, professionalism and collegiality in our staff; and

...

These values must inform the conduct of staff and affiliates in upholding and advancing:

• freedom to pursue critical and open inquiry in a responsible manner;

• recognition of the importance of ideas and ideals;

• tolerance, honesty, respect, and ethical behaviour; and

…

111 Part 4 of the Code of Conduct was headed “Personal and Professional Behaviour” and provided, relevantly, as follows.

In performing their University duties and functions, the behaviour and conduct of staff and affiliates must be informed by the University’s object and its values and the principles enunciated in Part 1 above. All staff and affiliates must:

…

• exercise their best professional and ethical judgement and carry out their duties and functions with integrity and objectivity;

…

• act fairly and reasonably, and treat students, staff, affiliates, visitors to the University and members of the public with respect, impartiality, courtesy and sensitivity;

…

• comply with all applicable legislation, industrial instruments, professional codes of conduct or practice and University policies, including …

112 Part 9 of the Code of Conduct, which was headed “Public Comment”, provided as follows:

Staff and affiliates are encouraged to engage in debate on matters of public importance.

However, staff and affiliates who make public comment or representations and, in doing so, identify themselves as staff or affiliates of the University must comply with the University’s Public Comment Policy.

113 The University’s Public Comment Policy provided, in part, as follows:

a) The University encourages academic staff to participate in public debate and be available to the media for comment in their field of expertise.