FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Gomeroi People v Santos NSW Pty Ltd and Santos NSW (Narrabri Gas) Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 26

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | SANTOS NSW PTY LTD AND SANTOS NSW (NARRABRI GAS) PTY LTD (FORMERLY KNOWN AS ENERGYAUSTRALIA NARRABRI GAS PTY LTD) First Respondent STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 6 March 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. On or before 4 pm on 13 March 2024, the parties file any agreed proposed orders to give effect to these reasons, including any agreed proposed orders as to costs.

3. In the absence of any agreement as to appropriate orders, on or before 4 pm on 20 March 2024 the parties file and serve any written submissions (limited to 5 pages) on an appropriate form of order including any proposed costs orders.

4. Any proposed orders or any submissions in accordance with orders 2 and 3 of these orders will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER CJ:

1 This appeal from the National Native Title Tribunal on questions of law was heard by a bench of three judges in the Court’s original jurisdiction, pursuant to a direction made by then Chief Justice Allsop under s 20(1A) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) on 10 March 2023. This appeal concerns the future act process under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), and a determination made by the Tribunal on 19 December 2022 that the grants of four petroleum production lease applications to the first respondent, Santos NSW Pty Ltd and Santos NSW (Narrabri Gas) Pty Ltd (formerly known as EnergyAustralia Narrabri Gas Pty Ltd), may be done, subject, in each case, to one condition (which is not material to the issues in dispute before this Court): see Santos NSW Pty Ltd v Gomeroi People [2022] NNTTA 74. The production lease applications lie entirely within the Narrabri gas project area, and within country claimed by the Gomeroi People.

2 The Tribunal’s determination appears at [1041] of its reasons:

The National Native Title Tribunal determines that the proposed future acts, pursuant to the Petroleum (Onshore) Act 1991 (NSW), being the grants of Petroleum Production Lease Application Numbers 13, 14, 15 and 16 may be done, subject, in each case, to a condition, pursuant to s 38(1)(c) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), such condition being that Santos NSW Pty Ltd and Santos NSW (Narrabri Gas) Pty Ltd (formerly known as EnergyAustralia Narrabri Gas Pty Ltd) take all necessary steps to ensure that the Additional Research Program, identified in para 5.7 of the Narrabri Gas Project Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Management Plan dated 21 February 2022, be implemented and completed prior to the commencement of Phase 2 of the Narrabri Gas Project, pursuant to the Development Consent granted by the Independent Planning Commission of New South Wales on 30 September 2020.

3 For the reasons set out below, the appeal will be allowed on the basis of one question of law.

BACKGROUND

4 An application for a determination of native title was filed in this Court on behalf of the Gomeroi People on 20 December 2011. The claim was registered on 20 January 2012, giving the registered native title claimant, which I shall call the Gomeroi applicant in these reasons, a “right to negotiate” under the NTA in respect of certain future acts, as defined in the NTA, proposed to occur on the country covered by their claimant application. The NTA confers the right to negotiate on the “registered native title claimant”, being a person or group of persons whose names appear on the Register of Native Title Claims as the applicant: see NTA s 23, read with ss 29 and 30. It is well-established that the right to negotiate is a valuable right that may be exercised before the validity of an accepted claim has been determined: see Fejo v Northern Territory [1998] HCA 58; 195 CLR 96 at [25] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ).

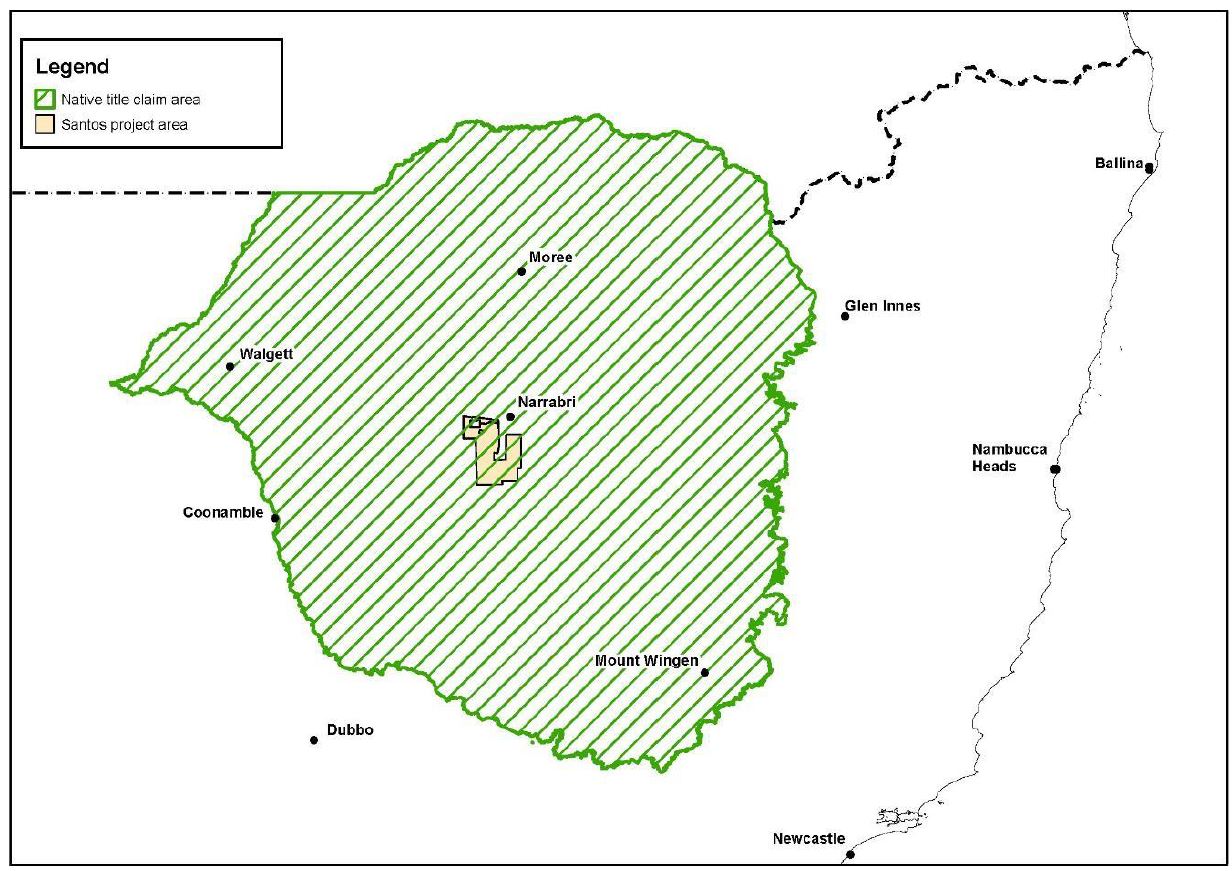

5 The Gomeroi People’s claim area is located in NSW, and covers in excess of 100,000 square km. It extends to the Queensland–New South Wales border, eastwards up to the western slopes of the New England Tableland, south to the Hunter and Goulburn Rivers and west to the Castlereagh, Barwon and Macquarie Rivers.

6 The future act process, as it applied to Santos’ production leases on country claimed by the Gomeroi People, was set out by the Tribunal in its helpful and concise Determination Summary, which I respectfully adopt:

Santos NSW (Eastern) Pty Ltd and associated companies propose to conduct a gas extraction operation, described as the Narrabri Gas Project. It concerns an area of 95,000ha within the claim area and located to the south and west of Narrabri. On 1 May 2014, Santos NSW Pty Ltd (“Santos”) lodged four petroleum production lease applications, covering an area of about 92,400ha, lying entirely within the Narrabri Gas Project area. On 30 September 2020, the Independent Planning Commission of New South Wales granted development consent for the Narrabri Gas Project, subject to 134 conditions. The decision was upheld by the Land and Environment Court of New South Wales. The relevant Commonwealth Minister has also granted the necessary approval.

Where a State or Territory government proposes to grant certain types of mining tenement, s 29 of the Native Title Act requires that it give public notice of such intention. On 28 May 2014, the State gave such notice concerning the petroleum production lease applications. Thereafter, the Gomeroi applicant, Santos and the State were obliged to negotiate in good faith, with a view to obtaining the Gomeroi applicant’s agreement to the proposed grants. See s 31(1) of the Native Title Act. Notwithstanding the development consent, negotiations concerning the proposed grants continued until 5 May 2021 when Santos applied to the National Native Title Tribunal for a determination that the proposed grants be made, notwithstanding the fact that the parties had not reached agreement. Negotiations continued after that date.

The Gomeroi applicant now asserts that Santos did not negotiate in good faith. If that were the case, the Tribunal could not determine that the proposed grants be made. See s 36(2) of the Native Title Act. The Gomeroi applicant made numerous assertions concerning Santos’s participation in the negotiations. However the Tribunal concluded that it had not demonstrated absence of good faith. The Tribunal was therefore obliged to decide whether the proposed grants should be made, having regard to the criteria identified in s 39 of the Native Title Act.

7 A map which shows both the Gomeroi claim area and the Narrabri gas project was attached to the Tribunal’s determination, and is attached as an annexure to the Court’s reasons.

8 There was no debate before the Tribunal nor on the appeal that the grant of the production leases to Santos fell within the future act provisions of the NTA.

9 Several of the questions of law raised by the Gomeroi applicant turn on Santos’ conduct during negotiations, and whether Santos negotiated in “good faith”. Relevantly to the appeal, s 31 of the NTA is the source of the statutory obligation to negotiate in good faith. The “negotiation parties” referred to in s 31 are defined in the NTA in s 30A:

30A Negotiation parties

Each of the following is a negotiation party:

(a) the Government party;

(b) any native title party;

(c) any grantee party.

10 Section 31 provides:

31 Normal negotiation procedure

(1) Unless the notice includes a statement that the Government party considers the act attracts the expedited procedure:

(a) the Government party must give all native title parties an opportunity to make submissions to it, in writing or orally, regarding the act; and

(b) the negotiation parties must negotiate in good faith with a view to obtaining the agreement of each of the native title parties to:

(i) the doing of the act; or

(ii) the doing of the act subject to conditions to be complied with by any of the parties.

Note: The native title parties are set out in paragraphs 29(2)(a) and (b) and section 30. If they include a registered native title claimant, the agreement will bind all of the persons in the native title claim group concerned: see subsection 41(2).

Government party does not need to participate in negotiations

(1A) Despite paragraph (1)(b), the Government party does not need to negotiate about matters that the Government party determines do not affect the Government party if the other negotiation parties give written consent.

(1B) However, the Government party must be a party to the agreement.

Registered native title claimants

(1C) The requirement that a native title party that is a registered native title claimant be a party to the agreement is satisfied if:

(a) a majority of the persons who comprise the registered native title claimant are parties to the agreement, unless paragraph (b) applies; or

(b) if conditions under section 251BA on the authority of the registered native title claimant provide for the persons who must become a party to the agreement—those persons are parties to the agreement.

(1D) The persons in the majority must notify the other persons who comprise the registered native title claimant within a reasonable period after becoming parties to the agreement as mentioned in paragraph (1C)(a). A failure to comply with this subsection does not invalidate the agreement.

Negotiation in good faith

(2) If any of the negotiation parties refuses or fails to negotiate as mentioned in paragraph (1)(b) about matters unrelated to the effect of the act on the registered native title rights and interests of the native title parties, this does not mean that the negotiation party has not negotiated in good faith for the purposes of that paragraph.

Arbitral body to assist in negotiations

(3) If any of the negotiation parties requests the arbitral body to do so, the arbitral body must mediate among the parties to assist in obtaining their agreement.

Information obtained in providing assistance not to be used or disclosed in other contexts

(4) If the NNTT is the arbitral body, it must not use or disclose information to which it has had access only because it provided assistance under subsection (3) for any purpose other than:

(a) providing that assistance; or

(b) establishing whether a negotiation party has negotiated in good faith as mentioned in paragraph (1)(b);

without the prior consent of the person who provided the NNTT with the information.

11 Section 33 provides:

33 Negotiations to include certain things

Profits, income etc.

(1) Without limiting the scope of any negotiations, they may, if relevant, include the possibility of including a condition that has the effect that native title parties are to be entitled to payments worked out by reference to:

(a) the amount of profits made; or

(b) any income derived; or

(c) any things produced;

by any grantee party as a result of doing anything in relation to the land or waters concerned after the act is done.

Existing rights, interests and use

(2) Without limiting the scope of any negotiations, the nature and extent of the following may be taken into account:

(a) existing non‑native title rights and interests in relation to the land or waters concerned;

(b) existing use of the land or waters concerned by persons other than native title parties;

(c) the practical effect of the exercise of those existing rights and interests, and that existing use, on the exercise of any native title rights and interests in relation to the land or waters concerned.

12 The premise of these provisions is that the NTA gives a registered native title claimant group or rights holding group a “right to negotiate”, but no right to veto the doing of a future act. Hence why the legislative scheme focuses on the process of negotiation. While there has been little express judicial commentary on the absence of a right of veto, the extrinsic material at the time these provisions were enacted made the legislative intention clear: see Western Australia v Manado [2020] HCA 9; 270 CLR 81 at [70] (Edelman J). The Tribunal has recognised this reality; see for example Minister for Lands (WA) v Buurabalayji Thalanyji Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC [2014] NNTTA 85 at [184] (President Webb).

13 Where no agreement has been reached, and at least six months have passed since the notification of the future act, s 35 provides for any negotiation party to apply to “the arbitral body” for a determination under the NTA. Relevantly, by s 27(2), the Tribunal was the arbitral body for the purposes of the grant of the production leases.

14 Section 36(2) constrains the Tribunal’s power, relevantly, from making a determination if a negotiation party (such as the Gomeroi applicant) satisfies it that another negotiation party (such as Santos), other than a native title party, did not “negotiate in good faith” as s 31 requires.

15 Section 38(1) sets out the kinds of determination that the Tribunal could make in the present circumstances. They were:

(a) a determination that the act must not be done;

(b) a determination that the act may be done;

(c) a determination that the act may be done subject to conditions to be complied with by any of the parties.

16 A number of mandatory considerations are prescribed for the Tribunal to take into account in making its determination. They are set out in s 39(1):

(1) In making its determination, the arbitral body must take into account the following:

(a) the effect of the act on:

(i) the enjoyment by the native title parties of their registered native title rights and interests; and

(ii) the way of life, culture and traditions of any of those parties; and

(iii) the development of the social, cultural and economic structures of any of those parties; and

(iv) the freedom of access by any of those parties to the land or waters concerned and their freedom to carry out rites, ceremonies or other activities of cultural significance on the land or waters in accordance with their traditions; and

(v) any area or site, on the land or waters concerned, of particular significance to the native title parties in accordance with their traditions;

(b) the interests, proposals, opinions or wishes of the native title parties in relation to the management, use or control of land or waters in relation to which there are registered native title rights and interests, of the native title parties, that will be affected by the act;

(c) the economic or other significance of the act to Australia, the State or Territory concerned, the area in which the land or waters concerned are located and Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders who live in that area;

(e) any public interest in the doing of the act;

(f) any other matter that the arbitral body considers relevant.

17 Therefore, in addition to the constraint on the Tribunal’s powers in s 36(2), by s 38 the Tribunal had a power to determine that the future act must not be done. At [37] of the determination, the Tribunal saw this bifurcation in the legislative scheme between its function in reaching a state of satisfaction about good faith negotiations and its function under s 38(1) (including consideration of the criteria in s 39(1)) as justifying separate consideration by it of these topics. I return to the role of s 36(2) below.

THE TRIBUNAL’S DETERMINATION

18 Following the approach taken by the Tribunal, I will first summarise the Tribunal’s reasoning on the absence of good faith allegation made by the Gomeroi applicant against Santos. In turn, this reasoning gives rise to the matters raised under questions of law 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6.

19 Next, I will summarise the Tribunal’s reasoning on the s 39(1) criteria, especially s 39(1)(c), (e) and (f). In turn, this reasoning gives rise to the matters raised under question of law 3.

Good faith

20 At [105]-[108], the Tribunal set out the legal principles it considered applicable to its evaluation of the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions about the absence of good faith shown by Santos in its negotiations. Where appropriate, it did so by reference to the parties’ respective contentions. This part of its reasons was not directly challenged by the Gomeroi applicant; rather, the challenges related to the later parts of the Tribunal’s reasoning where it applied these principles to the evidence. In written submissions in reply and in oral argument, senior counsel for the Gomeroi applicant clarified that there was no challenge to the Tribunal’s articulation of legal principle; rather only to its application. It is at this point that, in a number of ways, the Gomeroi applicant alleges the Tribunal failed to perform its task, or misunderstood the nature of the inquiry it was required to make into Santos’ alleged absence of good faith.

21 The Tribunal did not accept the Gomeroi applicant’s division of negotiations into distinct periods, finding that division to be arbitrary (see [109]), but did at least appear to accept that there may be factual matters arising during each “period” that it was being asked to assess, and therefore structured its determination by an examination of the evidence from each period nominated by the Gomeroi applicant. At [112] the Tribunal rejected the contention that the good faith obligation commenced at some time prior to notification pursuant to s 29 of the NTA, although it accepted at a factual level that events prior to notification might be relevant. On appeal there was no challenge to that finding, nor to the Tribunal’s ultimate factual finding that the events prior to 28 May 2014 (the notification day) provided “no substantial basis for the assertion that Santos’s conduct fell short of negotiation in good faith”: at [147].

22 In passages which featured in Santos’ submissions, and which are important in terms of understanding the Tribunal’s approach on the good faith contention, the Tribunal stated at [114]-[115]:

The Gomeroi applicant asserts that Santos’s conduct during each negotiation period demonstrates an absence of negotiation in good faith. However it is not sufficient for the Gomeroi applicant simply to identify conduct of which it disapproves. There may be circumstances in which conduct, in itself, demonstrates absence of good faith. However, in the present case, absence of good faith will depend on the availability of the inference that Santos was no longer seeking to reach agreement with the Gomeroi applicant and the State, as to the proposed grants. Section 31(1) does not require continuous negotiation in good faith from a date, arbitrarily chosen by one party, and continuing until the obligation is terminated by operation of the Native Title Act. The question posed by s 31(1)(b) is whether there has been negotiation in good faith, with a view to obtaining the agreement of the relevant native title party.

The fact that a negotiation party finds another party’s conduct to be offensive, or simply annoying, does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that the latter is not negotiating in good faith. There are many ways to negotiate. Methods may reflect the personality and/or professional and life experience of each negotiator. Methods may also reflect a negotiator’s perceptions of the respective strengths and weaknesses of the parties. Negotiation may be in good faith, even if a party drives a hard bargain, perhaps reflecting perceptions as to such strengths and weaknesses. Section 31(1)(b) does not focus on “good faith”. Rather, it focusses on negotiation in good faith, “with a view to obtaining the agreement” of the Gomeroi applicant, to the doing of the relevant acts. That purpose informs the scope of the duty to negotiate in good faith.

23 In these reasons, it is not necessary to traverse in detail the Tribunal’s careful fact finding on the good faith arguments. Where necessary I refer to the fact finding in consideration of the questions of law on the appeal. The Tribunal considered various periods of negotiations with, during each period, a differently constituted Gomeroi applicant. From [148]-[178] the Tribunal set out its finding for the period 2013-2017 (referring to the constitution of the Gomeroi applicant following orders of this Court on 13 August 2013 made pursuant to s 66B of the NTA) concluding (at [178]) that on the evidence:

Setting aside the delay between early 2015 and July 2016, it seems most unlikely that Santos was, for a period of 18 months, from July 2016 until December 2017, participating in an elaborate farce. The evidence suggests that it was trying to maximize the prospects of reaching agreement with the Gomeroi applicant, however constituted. I see no basis for concluding that Santos was negotiating other than in good faith, with a view to obtaining the Gomeroi applicant’s agreement to the proposed grants. However, given the limitations imposed by the native title claim group upon the Gomeroi applicant (2013-2017), resolution was always subject to its approval.

24 The Tribunal then considered the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions about the period 2017-2022 (referring to the constitution of the Gomeroi applicant following orders of this Court on 7 December 2017 made pursuant to s 66B of the NTA). The Tribunal traced the course of negotiations during this period, including whether during the latter part of this period, there was in fact a negotiation under s 31(1) or whether negotiations about proposed conditions that might attach to a s 38 determination were outside the good faith obligation. The Tribunal also describes an offer made by Santos on 29 March 2021, which had been rejected by the Gomeroi applicant but which remained Santos’ principal offer, to avoid a determination under s 38 of the NTA. The Tribunal also considered and rejected the Gomeroi applicant’s contention that by filing a s 35 application on 5 May 2021, Santos acted unreasonably, and that this was evidence of lack of good faith. In its fact finding in this section the Tribunal also makes findings about delays on the part of the Gomeroi applicant during the negotiations and its conduct in arranging and conducting claim group meetings. By [265], the Tribunal has rejected all of the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions about the 2017-2022 period.

25 The Tribunal then turns to set out five propositions, said to focus primarily “on the period between 7 December 2017 and 5 May 2021, although the propositions may have wider connotations” (at [266]). These propositions, and the Tribunal’s reasoning about them, featured in the parties’ submissions on the appeal.

26 The five propositions were (at [266]):

(a) Santos’s offer of compensation was below market value;

(b) Santos did not engage with an expert;

(c) Santos adopted a fixed position on compensation;

(d) Santos failed to provide important information; and

(e) Santos’s use of the future act determination application “lever” comprised an attempt by Santos to take advantage of its stronger bargaining position.

27 Having set these out, the Tribunal commented (at [267]):

The propositions, at least at face value, offer a more coherent approach to the question of negotiation in good faith than does the piecemeal approach adopted elsewhere in the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions.

28 The Tribunal (at [268]-[271]) described each of the propositions in the following way, which was not challenged on appeal:

The first proposition relates primarily to the valuation evidence of Mr Kuo ning Ho, a chartered accountant who provided a report concerning the production levy and royalty payments. The second proposition is concerned primarily with the valuation report of Mr Murray Meaton, which report was dated April 2017. In the third proposition the Gomeroi applicant seems to assert that Santos:

• knowingly failed to make a “reasonable” offer;

• adopted a rigid, non-negotiable position in relation to the “unfair” offer of compensation; and

• took advantage of its superior bargaining position.

It is not clear whether this complaint is about the overall package offered by Santos, or the offer of the production levy. In para 163 of the contentions the Gomeroi applicant asserts that Santos has substantial experience in making agreements. The purpose of such assertion seems to be to demonstrate Santos’s experience in negotiating agreements of the kind sought with the Gomeroi applicant. This proposition seems to have been advanced in order to demonstrate that Santos was obliged to make a “fair” offer rather than bargain in its own interests. It is unclear whether paras 164-168 are concerned with compensation or the production levy.

The fourth proposition is that Santos delayed in responding to, and then declined, the Gomeroi applicant’s request for information and further expert advice. I have dealt with these matters elsewhere in this determination and so will be able briefly to dispose of this proposition.

The fifth proposition relates to Santos’s s 35 application, made on 5 May 2021. I have also dealt with this matter in some detail. I need not further address it at length.

29 From [272], the Tribunal deals with a number of matters it describes as “Preliminary Issue[s]”. This includes the relationship, if any, between negotiations under s 31 and an award of compensation, the evidence of Mr Kuo ning Ho who was an expert witness relied on by the Gomeroi applicant in the inquiry before the Tribunal and the expert report of Mr Murray Meaton to the Gomeroi People, which was annexed to the affidavit of Mr MacLeod in the inquiry before the Tribunal. The Tribunal also deals with the use of the term “markets” by Mr Ho and Mr Meaton. One of the key disputes between the Gomeroi applicant and Santos, in terms of whether Santos negotiated in good faith, concerned the adequacy of part of Santos’ offer by reference to a production levy, or royalties from the Narrabri gas project.

30 The Tribunal also gives detailed consideration to Mr Meaton’s report, finding (at [331]) that contrary to the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions, the evidence strongly suggests that there was extensive discussion between Santos and Mr Meaton, over a considerable period of time. The Tribunal then concludes:

There is no basis for asserting that Santos should have abandoned its own negotiating position in favour of Mr Meaton’s. To treat Santos’s refusal as demonstrating absence of good faith would unjustifiably undermine its ability to negotiate freely, pursuant to s 31(1).

31 The Tribunal then identifies what it describes as a number of weaknesses in Mr Meaton’s report, and rejects the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions about lack of good faith based on Santos’ attitude to Mr Meaton’s views.

32 From [338], the Tribunal considers the evidence of both Mr Meaton and Mr Ho, Santos’ approach to their opinions, and the parties’ contentions about how their respective assessments of the value of Santos’ offers can or cannot demonstrate lack of good faith by Santos. In substance, the Tribunal does not accept the views propounded by Mr Ho and Mr Meaton provided any basis for the Gomeroi applicant’s assertion that the offers made by Santos were so inadequate that they demonstrated a lack of good faith.

33 At [342], the Tribunal considers the evidence of Mr Haydn Kreicbergs, one of Santos’ employees, relating to five other projects in which Santos did not pay a royalty. The Tribunal’s reliance on Mr Kreicbergs’ evidence also forms part of the questions of law on the appeal. At [345], in a passage of some importance to the good faith questions of law on the appeal, the Tribunal found:

At para 5 of the submissions, apparently concerning Mr Kreicbergs’ cross-examination, the Gomeroi applicant asserts that Santos knew that its offer was under value, and failed to expose its methodology for testing in this inquiry, knowing that it, “would not stand such scrutiny.” The proposition seems to be based on some variation of the decision in Jones v Dunkel, asserting that the Tribunal might infer that such evidence was not led because it would not have been helpful. The submission is misconceived. It assumes that there was an obligation upon Santos to make an offer which fell within a particular range. There is no basis for that proposition. The parties were negotiating, not valuing. There was no obligation to make a “reasonable” offer. The obligation was to negotiate in good faith and, of course, it was the overall package which was the relevant consideration. I do not accept the proposition that Santos “knew” that its offer was “under value”. To the extent that the Gomeroi applicant asserts that such knowledge is based upon Mr Meaton’s evidence, I reject the contention. To the extent that the Gomeroi applicant relies upon Mr Ho’s evidence in order to establish such knowledge, I shall presently demonstrate my reasons for rejecting his evidence.

34 At [348], the Tribunal returned to one of the weaknesses it identified throughout its reasoning in the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions; namely the absence in the parties’ negotiation of any connection between the competing monetary calculations and the impact of the grant of the production leases on native title rights and interests:

However neither the Gomeroi applicant nor Santos paid much regard, if any, to the impact of the proposed grants on native title rights and interests, let alone to any additional value representing non-economic or cultural loss. The issue seems to have been raised for the first time in Mr Kreicbergs’ cross-examination. In those circumstances, I see no basis for concluding that Santos’s failure to deal with the issue should lead me to conclude that it failed to negotiate in good faith. Quite apart from anything else, the negotiations were more about maximizing or minimizing the production levy or royalty payments, than about valuing either impact on native title rights and interests, or non-economic loss. In those circumstances, the decision in Northern Territory v Griffiths has no relevance to the current consideration as to good faith.

35 It was this view that led, it would appear, the Tribunal to conclude (at [352]) that the parties were not negotiating about compensation under the NTA, and were rather:

simply seeking to divide up the proceeds of the project, although it may be that an agreed sum, however calculated, may have been paid and accepted in discharge of any compensation entitlement. The parties were at liberty to negotiate on that basis. However it is difficult to see how such open-ended negotiation could be used to discredit the position adopted by Santos. Although lip service has been paid to compensation, there is no objective evidence that the negotiations were conducted on that basis.

36 The Tribunal in substance repeated this finding at [409], during its consideration of Mr Ho’s evidence.

37 From [353], the Tribunal considered in detail the evidence of Mr Ho, who is a chartered accountant, and whom the Tribunal described as having:

provided expert reports for the purposes of litigation in a range of compensation matters, including the quantification of damages, and the valuation of assets. He appears to have been engaged in many different mining and native title matters. He is referred to by NTSCORP in his instructions as the “Economist”, although I do not understand him to claim that qualification. The matter is of no consequence.

38 There was no challenge to this description by the Tribunal. However, the Tribunal’s treatment of Mr Ho’s evidence featured in some of the good faith questions of law.

39 After a detailed consideration of Mr Ho’s evidence, his cross-examination and the parties’ contentions, the Tribunal concluded at [448]-[449] that there were four primary reasons for rejecting Mr Ho’s evidence:

There are four primary reasons for rejecting Mr Ho’s evidence. First, Mr Ho has not demonstrated the basis of his assertion as to the comparability of the comparable projects and associated agreements with the Narrabri Gas Project and the Proposed Terms. As a result, neither Santos, nor the State, nor the Tribunal can assess such alleged comparability, and therefore the relevance and correctness of Mr Ho’s opinions. Second, there is no demonstrated justification for comparing the production levy (separately from the overall offer made in the Proposed Terms) and with incomplete knowledge of the comparable projects and associated agreements. Third, estimates and assumptions which form the basis of conclusions reached in ch 15 of the report are incorrect, as demonstrated above. Fourth, in his discussion of economic principles, Mr Ho stresses the importance of voluntary negotiation. See paras 7.5-7.8, 7.10-7.11 and 7.13 of his report. In his cross-examination, at ts 242, ll 29-38, he describes the right to veto as being “pivotal” in the context of a “free transaction”. However, at ts 243, ll 40-44, he asserts that whilst the Land Rights Act allows a veto, the Native Title Act does not. Whether his view as to the Land Rights Act is correct does not matter. The point is that the Native Title Act, “allows no such veto”. As a result, Mr Ho’s discussion of economic principles in ch 7 of his report seems to be irrelevant for present purposes, given that he there discusses:

• “an agreement reached on the same basis as any transaction, at a given price, that is satisfactory for both the buyer and the seller”;

• fair value within a free market;

• that “a transaction is a voluntary exchange, and the laws of supply and demand provide the sole basis for economic transactions when the participant’s decision to participate is totally voluntary, without coercion or conditions”; and

• “an asset’s sale price agreed upon by a willing buyer and seller, assuming both parties are knowledgeable and enter the transaction freely”.

Clearly, these asserted concepts have no relevance to s 31(1) negotiations, given the requirement to negotiate in good faith, the absence of a right of veto and the role of the Tribunal.

40 The Tribunal then adds at [450] that Mr Kreicbergs’ evidence, which it accepts, “puts the matter” of any allegation that Santos knew it was making an “under value offer” beyond doubt, in terms of rendering such a suggestion untenable:

I do not understand his evidence to be challenged. It constitutes a coherent explanation of other transactions in which Santos has been involved. In my view, in light of such evidence, there is no basis upon which it can be asserted that Santos ought to have known about, and acted upon opinions such as those allegedly held by Mr Meaton and Mr Ho.

41 From [451], the Tribunal returns to the Gomeroi applicant’s contention, as it describes it, that in order to negotiate in good faith, Santos had to make an offer that was objectively reasonable. The Tribunal rejected this contention (at [452]):

Nor is there necessarily an obligation to make a “reasonable offer”. The Gomeroi applicant’s assertions reflect a misunderstanding of the negotiation process. If an offer had to be “reasonable”, the parties to negotiation would not be able to identify a realistic starting point for negotiations. Further, “reasonableness” generally bespeaks an objective standard against which particular conduct may be assessed. Section 31(1) does not require conduct which is objectively reasonable. It requires only negotiation in good faith.

42 From this paragraph to [459], the Tribunal rejects other contentions of the Gomeroi applicant along the same lines. Then from [460], the Tribunal deals with the contentions about Santos’ alleged failures to provide information required for the negotiations. It finds nothing unreasonable in Santos’ conduct. From [463], the Tribunal also finds nothing unreasonable or demonstrative of a lack of good faith in Santos making a s 35 application at the time it did.

43 Accordingly, from [465], the Tribunal rejects the contention that any of the five propositions, or the evidence said to support them, proves a lack of good faith by Santos.

44 From [468], the Tribunal deals with a supplementary submission, based on alleged contraventions of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). The contentions concerned a NSW government document entitled “Agreed Principles of Land Access”, dated 28 March 2014. Santos’ approach to this policy was said by the Gomeroi applicant to recognise a right of veto in non-native title proprietary interest holders over access to their land by Santos for the purposes of the Narrabri gas project, in comparison to the absence of such a veto for the Gomeroi applicant: see [474] of the Tribunal’s reasons for a summary of the argument.

45 The Tribunal rejected these contentions, and the questions of law do not impugn those conclusions. Therefore it is unnecessary to summarise the Tribunal’s reasoning on this matter.

46 From [488]-[537] the Tribunal deals with some supplementary submissions made by the parties about the good faith arguments. It is unnecessary to summarise the Tribunal’s reasoning in these passages as it is not substantively impugned in any of the arguments on the questions of law. Suffice to say nothing in the supplementary submissions changed the Tribunal’s view of the correct conclusion on good faith.

47 From [549]-[561], the Tribunal summarises its reasoning on the good faith arguments, concluding (at [561]) that there is:

no basis for finding that at any time since the notification day, or before that day, Santos failed to negotiate in good faith, with a view to obtaining the Gomeroi applicant’s agreement to the proposed grants.

48 Having therefore found that the Tribunal’s powers are not constrained by s 36(2), the Tribunal turns to the s 39 criteria.

Section 39(1) criteria

49 The Tribunal frames its task in the following way (at [562]):

The question pursuant to s 39 is whether, I consider the proposed grants should be made, or should not be made, or should be made subject to conditions. Whilst the good faith question was a matter of fact, the answer being either “yes” or “no”, the s 39 question is of a somewhat difficult kind. It is a matter of judgement. I must assess the factors listed in s 39, and then decide the preferable outcome, having regard to those factors.

50 Before describing the remainder of the Tribunal’s reasoning on the s 39(1) criteria, it is important, for the purposes of question of law 3, to set out what the Tribunal said towards the end of the “good faith” section of its reasoning.

51 From [538], the Tribunal addresses the Gomeroi applicant’s submissions about whether it should adopt the decision of the Independent Planning Commission of NSW relating to the effects of the Narrabri gas project on emissions, or whether it should prefer the evidence of Professor William Steffen, an expert witness relied on by the Gomeroi applicant in the inquiry before the Tribunal. At [542], the Tribunal held:

It is not practicable for this Tribunal to second-guess specialist bodies such as the Independent Planning Commission, save to the extent that there may be specific impact upon native title rights and interests. There may be circumstances in which such a decision should be considered in light of new information or changing scientific views. However, for a non-scientific Tribunal, to take such a step is necessarily the exception rather than the rule. I am not persuaded that the state of the evidence is such that I should depart from the decision of the Independent Planning Commission. That Commission, and this Tribunal, have functions which require the balancing of interests. There are, and will continue to be, differences of opinion about this project, however the matter may be decided. In my view, and for the reasons discussed elsewhere in this determination, the balancing exercise carried out by the Independent Planning Commission is more likely to assist the Tribunal in performing its function than is Professor Steffen’s narrower views, although they are no doubt well informed.

52 The views expressed in these passages inform the Tribunal’s approach to the s 39(1) criteria.

53 From [563]-[693], the Tribunal then proceeds to summarise the evidence relevant to each of the criteria in s 39(1). It is not necessary to set out or describe those summaries, and where necessary I return to this section of the Tribunal’s reasons when considering question of law 3. From [694], the Tribunal sets out the contentions of the Gomeroi applicant on various aspects of s 39(1). It is not necessary to summarise them here, aside from the Tribunal’s recitation of the contentions on the “public interest”. At [769]-[771] the Tribunal summarises those contentions as follows:

The Gomeroi applicant contends that the Tribunal should make a determination that the act must not be done, for the reason that it is, “against the public interest”. At para 267 of its contentions, the Gomeroi applicant states:

If the Project proceeds, a substantial quantity of greenhouse gas … emissions will be emitted. It follows that the grant of the PPLs will not only not assist with meeting the temperature targets in the Paris Accord, but will contribute to higher temperatures than the target and the more extreme impacts of climate change.

At para 268, the Gomeroi applicant submits that there is a public interest in:

(a) seeking to mitigate and prevent the worst likely effects of global warming, which has consequences at global, national and local levels, and

(b) the preservation and continuity of the culture and society that underpins the Gomeroi People’s tradition law [sic] and custom.

The only matters of public interest, referred to by the Gomeroi applicant, concern climate change, and the preservation and continuity of the Gomeroi people’s culture and society. These matters will be dealt with elsewhere in this determination.

54 The Tribunal then turns to a number of other contentions made by the Gomeroi applicant, and its conclusions on them, which it is not necessary to canvass as they do not arise on the appeal. From [805]-[965], the Tribunal summarises and considers Santos’ contentions in response and the State’s contentions. Again it is not necessary to descend into any description of these passages. The Tribunal summarises the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions in relation to “public interest” from [947]-[960]. At [966]-[967], the Tribunal briefly summarises the State’s contentions.

55 From [968], the Tribunal sets out its reasoning on the s 39(1)(e) and (f) criteria, under the heading “Consideration”.

56 The Tribunal’s overall approach is encapsulated at [968]-[969]:

In the present case, the Gomeroi applicant asserts that I should, “make a fresh and independent decision”, in effect asking that I review evidence underpinning the decision of the Independent Planning Commission, and then adopt the evidence of Professor Steffen. It is difficult to see any justification for the contention that I should simply disregard processes to which the Narrabri Gas Project has been subject, at both State and Federal levels, particularly having regard to Parliament’s view as set out in the explanatory memorandum concerning the 1998 Act. It would be a big step to set aside the outcome of such statutory processes in order to adopt the views of an individual scientist, or even the views of international agencies having no particular standing in Australia or in New South Wales.

It is surprising that Professor Steffen should have given his evidence on the assumption that the Narrabri Gas Project would involve hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”. One might reasonably have expected that he would have been appropriately briefed on such matters. It is disturbing that he should dismiss the view of the Independent Planning Commission that there would be “expected emissions advantages” in using coal seam gas rather than coal. He appears to have dismissed the Commission’s views concerning the utility of such advantages on the basis of his view that, “the science is absolutely clear”, impliedly suggesting that the Commission had chosen to ignore the “absolutely clear” science. The conclusions reached by a statutory body such as the Independent Planning Commission cannot be simply dismissed upon the basis of an assertion by one scientist and sources upon which he or she has chosen to rely. It is unlikely that the Tribunal could perform that function, or was ever intended to do so.

57 The reasoning at [970] is material to question of law 3:

It is fair to say, as Santos does, that Professor Steffen did not address the matters identified in s 39(1)(a) of the Native Title Act, including the more limited considerations relating to environmental matters, subsequent to the 1998 Act, namely particular environmental concerns having particular effect on native title. In effect, he identifies expectations as to future climate change over the Eastern Australian States, to the west of the Great Dividing Range, from the Darling Downs in Queensland to the Central West of New South Wales. I accept, for present purposes, that such prediction is reasonably open in all the circumstances. However I am presently concerned with the effect of the proposed grants on the Santos project area. There is no identified “particular environmental concern” having “particular effect” on native title, presumably, in this case, the Gomeroi applicant’s native title. There is concern about worldwide climate change, predicted to affect a large part of Eastern Australia. There is nothing “particular” about either the environmental concern, or its effect on such native title. Indeed, the Gomeroi applicant has mounted no such argument. These are world-wide concerns, to be resolved by governments.

58 The Tribunal then states at [974]-[975]:

It seems to me that s 39(1)(f) provides a sufficient basis for taking into consideration the fact that there has been a rigorous examination of a proposed project by a relevant authority. However s 146 of the Native Title Act also provides a basis for reliance upon reports, findings, decisions, determinations, or judgments of the various courts, persons or bodies identified in s 146(a).

Santos contends that the Tribunal’s role is to consider the factors set out in s 39, and not to reassess the Narrabri Gas Project. It does not follow that the Tribunal should simply rely upon views expressed by other tribunals. Nor may they be ignored.

59 From [976], including by reference to Santos’ submissions, the Tribunal explains why it considers it appropriate to rely on the State level assessments and the statement of reasons for decision of the IPC on 30 September 2020. At [987], in a passage material to question of law 3, the Tribunal finds:

I accept that greenhouse gas emissions may lead to environmental harm. However, in my view, since the 1998 Act, it has not been appropriate to consider environmental (or ecological) matters, save to the extent that such concerns may have a particular effect on native title. That matter should be considered pursuant to s 39(1)(f) and subject to the Tribunal’s view as to relevance. In any event, the matter has been extensively considered by the relevant State agencies and appropriate approvals given. There are conflicting views concerning climate change and knowledge is rapidly expanding. Nonetheless a decision has been made by the relevant authority. The Gomeroi applicant seeks to avoid that decision by referring to Professor Steffen’s views. He seeks to dismiss the approvals by referring to additional information including a further report from a United Nations agency. It does not follow that I should simply dismiss the decisions of State agencies. The Tribunal’s concern is with any particular effect on native title. It cannot be said, in this case, that there is any particular effect upon native title which must be considered. The problem is world-wide.

60 From [995] the Tribunal continues on to consider the matters in s 39(2), but this aspect of its reasoning is not impugned on the appeal, and therefore need not be set out.

61 From [1001], the Tribunal sets out its conclusions on s 39, working through each of the criteria in s 39(1). At [1014]-[1016], the Tribunal refers to s 39(1)(c) and (1)(e), finding they may be considered together:

Sections 39(1)(c) and 39(1)(e) may be considered together. There can be no doubt that there is a demand for gas from the Narrabri Gas Project. It seems unlikely that either the State or Santos would otherwise have devoted undoubtedly substantial resources to the project. The proposed grants are of economic significance to Australia, the State and the region, as well as Aboriginal people. Whilst there may be some degree of risk associated with the project, there can be little doubt that the State and Santos have made substantial efforts to minimize the risk. One cannot simply dismiss scientific and engineering experience. Nor is it practicable for the Tribunal to second-guess State agencies in the performance of their prescribed functions, even when faced with Professor’s Steffen’s undoubted expertise, and the information provided by international agencies. In a democracy experts advise, but governments make final decisions and accept political responsibility for the consequences of such decisions.

Aspects of the public interest may be in conflict. Whilst the development of gas resources may be in the public interest, possibly adverse consequences may not be in the public interest. In the present case, the risk of escaping gas and contribution to climate change are factors for consideration, as is, particularly, the public interest in the preservation of Aboriginal culture and society.

The 1998 Act removed the consideration of environmental considerations from the s 39 decision-making process, save when there is a particular effect on native title. There is no apparent matter having such particular effect in this case. Whilst there may be a public interest in the consequences of exploiting gas reserves, there is no doubt that the State, in particular, and the Commonwealth have acted in accordance with State and Commonwealth law.

62 At [1017], the Tribunal deals with s 39(1)(f):

As to s 39(1)(f), I have dealt with the contentions concerning the desirability of a voluntary regime protecting cultural heritage values. I have also discussed the significance of climate change which is discussed in connection with ss 39(1)(c), (e) and (f). As to that matter, even if one takes the approach taken by Santos and the State, rather than that which I prefer, having regard to the 1998 Act and the explanatory memorandum, it is difficult to attach much weight to the public interest, beyond that attributed to it in any consideration of s 39(1)(c). Section 39(1)(f) is of no relevance, given that there is no suggestion of particular environmental concerns producing particular effects on native title.

63 These passages are material to question of law 3.

64 From [1019]-[1024], the Tribunal circles back to the s 39(1) criteria in a more general way, making a series of observations which are also material to question of law 3:

In assessing the s 39 criteria, significant weight must be given to s 39(1)(a)(i). The failure by the Gomeroi applicant to address the effect upon the enjoyment of its native title rights and interests is of some importance. The matters identified in ss 39(1)(a)(ii) and (iii) are closely associated with such enjoyment. The Gomeroi applicant’s failure to distinguish, between the native title claim area and the Pilliga on one hand, and the Narrabri Gas Project area and the Santos project area on the other, is also of considerable importance.

Concerning s 39(1)(a)(iv) Mr Kumarage places great weight upon access as being essential to the exercise of native title rights and interests and associated matters. However any difficulties in access are restricted to the Narrabri Gas Project area, including the Santos project area. In those locations, there may be some limitations on access, as the result of fencing for purposes of safety and security. However the extent of such fencing will be limited. As to s 39(1)(a)(v), there is very little, if any evidence as to the existence of areas or sites of particular significance.

Concerning s 39(1)(b), the Gomeroi has, in the end, taken a hard line in its participation in the s 31(1) negotiation process. Its current position is that there should either be a determination that the proposed grants not be made, or a determination on terms of which it approves. Such an approach makes negotiation difficult. However it also demonstrates that whatever the Gomeroi applicant’s preference might previously have been, it will no longer agree to the proposed grants.

As to the economic and other significance of the Narrabri Gas Project, Santos has identified the considerable worth of the project to the Narrabri area, the State and the Commonwealth. The Gomeroi applicant chose to base its opposition primarily upon climate change, and by its reference to unclear assertions concerning the “involuntary” nature of the development consent process. Given the extensive consideration of the climate change issue by the State, it is obvious that any decision reached by the State or its agencies should be respected. There is no reasonable basis upon which the Tribunal could justify any preference for Professor Steffen’s evidence and the views of United Nations agencies over the State’s decision. Whilst there is, no doubt, a public interest in climate change, the intentions underlying the 1998 amendments are clear.

As to the Gomeroi applicant’s concern with the non-voluntary nature of the development consent process, such concern seems to be focussed upon the operation of the Aboriginal Heritage Management Plan. The State required that such plan be incorporated into the development consent. Pursuant to the Plan, the Gomeroi applicant is represented on the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Advisory Group and the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Working Group. It has clear opportunities to express its views. It may be that the Gomeroi applicant’s concerns relate to the representation of other Aboriginal groups on those bodies.

I accept that the Gomeroi applicant has genuine concerns about the recognition and protection of its native title rights and interests, and the associated matters identified in s 39. It is unfortunate that the parties have been unable to agree. I attribute such failure, at least in part, to confusing expert evidence. In any event, the Tribunal must now resolve the matter. There can be little doubt that there is a significant public interest in the responsible exploitation of gas reserves. Substantial resources have been expended by the State and by Santos in ensuring such responsible exploitation. Whilst I understand the Gomeroi applicant’s concern, I consider that, having regard to the matters set out above, its concerns are outweighed by the public interest.

65 From [1025] the Tribunal deals with the imposition of conditions, which is a section of its determination that is not relevant to the questions of law on the appeal.

66 The Tribunal’s actual determination appears at [1041] of its reasons, and I have referred to it at [2] above.

QUESTIONS OF LAW

67 As the respondents pointed out, there was not always a clear correlation between how the questions of law in the further amended notice of appeal from a tribunal were expressed, and the Gomeroi applicant’s submissions in writing and orally. Nevertheless, in my view both respondents were well able to deal with (and did deal with) how the case was advanced at the appeal hearing. If anything, all this meant was that some contentions that might have appeared in the further amended notice of appeal were not advanced in written or oral submissions. I have proceeded on the basis of how matters were advanced in written and oral submissions. It is those contentions which the respondents addressed. The Court can assume counsel for the Gomeroi applicant made some forensic choices about how to advance the questions of law, given there was a degree of overlap on the five questions that addressed the good faith requirement.

68 I set out first my reasons for concluding I should not accept the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions on the five questions of law relating to the good faith requirement. Lastly, I deal with question of law 3, which concerns a different kind of alleged error.

Question 1: Good faith

69 The further amended notice of appeal puts question 1, and the accompanying grounds, as follows:

1 Did the Tribunal apply the wrong test for good faith or, alternatively, incorrectly apply the test correctly identified?

Grounds

The Tribunal erred:

(a) in finding (at [410] and [450]) that an offeror must actually know (or ought to have known) that its offer is under-value only at the time of making it, and actually know information about comparable projects and associated agreements (at [411] and [459]);

(b) in finding (at [454] – [459]) that whether an offer is reasonable must only be assessed subjectively from the perspective of the offeror;

in that those findings are inconsistent with authority.

70 In its reply submissions, and orally, the Gomeroi applicant conceded that the Tribunal had identified the correct test for good faith. Instead, it contends this question focuses on the application of the test to the evidence before the Tribunal.

Ground (a)

71 The Gomeroi applicant submits that the Tribunal erroneously only considered Santos’ knowledge at the time it made its first offer to the Gomeroi applicant, rather than considering good faith “in the context of the negotiations as a whole”: Western Australia v Taylor [1996] NNTTA 34; 134 FLR 211 at 218-224, 237 (Member Sumner).

72 In oral submissions, Santos contended that s 31(1) of the NTA does not require conduct that is objectively reasonable but requires negotiation in good faith assessed objectively. Santos contended that the Tribunal considered Santos’ conduct extensively and applied the correct test to the whole of Santos’ conduct, including the conduct in which the Gomeroi applicant complains.

Ground (b)

73 Relying on Brownley v State of Western Australia (No 1) [1999] FCA 1139; 95 FCR 152 at [34]-[35] (Lee J), the Gomeroi applicant also contends that the Tribunal erred in its approach to considering the reasonableness of the offer made by Santos, and in its focus only on the subjective intention of Santos.

74 The Gomeroi applicant submits that the Tribunal failed to consider that Santos had knowledge of Mr Ho and Mr Meaton’s reports in assessing Santos’ knowledge. It submits that these reports were relevant to an assessment of whether Santos “turn[ed] a blind eye”, because Santos knew its offer was outside the range set out in both the reports of Mr Ho and Mr Meaton. The Gomeroi applicant contends that a failure to inquire while holding such knowledge could, and should, support an inference that Santos was not negotiating in good faith, citing International Alpaca Management Pty Ltd v Ensor [1995] FCA 1054; 133 ALR 561 at 596-597 (Beaumont and Carr JJ), cited by Lee J in Brownley at [27].

75 In oral argument, senior counsel clarified that the Gomeroi applicant’s position was that the Tribunal focused too much on its assessment of the expert reports and whether Santos’ offer was in fact “fair value”, rather than looking at the question of whether Santos responded appropriately to the information available to it, especially in not engaging with the opinions of the experts retained by the Gomeroi applicant, and as a result whether it had not acted in good faith.

Question 1: Resolution

76 After the concession by senior counsel that the Tribunal correctly articulated the approach to whether a party has negotiated in good faith, it follows that whether a party such as Santos negotiated in good faith with the Gomeroi applicant with a view to obtaining the group’s agreement to the grant of the production leases (with or without conditions) and therefore Santos undertaking the Narrabri gas project was a question of fact: see Walley v Western Australia [1999] FCA 3; 87 FCR 565 at [11] (Carr J).

77 Subject to the observations I make below at [95] – [97], there was no real dispute between the parties about some of the indicia of acting in good faith, and not acting in good faith, and how a party’s conduct should be assessed. The Gomeroi applicant accepts that an assessment about whether a party has negotiated in good faith pursuant to s 31 of the NTA requires consideration of the conduct as a whole. In Strickland v Minister for Lands for Western Australia [1998] FCA 868; 85 FCR 303 at 321, R D Nicholson J stated:

What is required is the court or Tribunal apply the test of “negotiating in good faith”, in accordance with the common understandings encompassing subjective and objective elements, to the total conduct constituting the negotiations. All those circumstances must be considered against the legal requirements of the phrase “negotiating in good faith”.

78 The Gomeroi applicant also accepts, consistently with established authority, that the question of good faith is directed to a party’s state of mind, and requires an assessment about whether the party is honestly, legitimately and fairly negotiating towards an agreed outcome. Correctly, the Gomeroi applicant contended that this may well involve an assessment of how a party has objectively behaved, as an indicator of the party’s state of mind. However, senior counsel agreed that the inquiry was directed at whether a party was acting honestly, with an open mind, willing to listen and without any ulterior motive. See generally FMG Pilbara Pty Ltd v Cox [2009] FCAFC 49; 175 FCR 141; Charles v Sheffield Resources [2017] FCAFC 218; 257 FCR 29.

79 Again correctly, the Gomeroi applicant pointed to authorities that emphasised that acting in good faith, and acting honestly, did not permit a negotiating party to shut its eyes to the obvious, or deliberately refrain from asking questions in case information comes to their attention that they might prefer not to know: see generally, International Alpaca at 596, and also the extract in International Alpaca at 596 from Royal Brunei Airlines Sdn Bhd v Tan [1995] 2 AC 378 at 389:

these subjective characteristics of honesty do not mean that individuals are free to set their own standards of honesty in particular circumstances. The standard of what constitutes honest conduct is not subjective. Honesty is not an optional scale, with higher or lower values according to the moral standards of each individual…

Nor does an honest person … deliberately close his eyes and ears, or deliberately not ask questions, lest he learn something he would rather not know, and then proceed regardless.

80 Finally, in terms of general approach to the issues before the Tribunal and now raised in the questions of law, it can be accepted, as the Gomeroi applicant put to the Tribunal in its Contentions to the Tribunal at [43], that:

the right to negotiate subsists to a large extent in the statutory duty imposed upon the negotiation parties to negotiate for at least the statutory period, in relation to at least the statutory matters, in good faith. Failure to do so will mean that the Tribunal may not make a s [38] determination.

(Footnotes omitted.)

81 In other words, satisfying the requirement to negotiate in good faith for the minimum statutory period is a constraint on the Tribunal’s powers in s 38 arising. On current authority, if the point is taken by a negotiation party and the Tribunal is satisfied that there has not been a good faith negotiation as required by s 31(1)(b), the Tribunal cannot make a determination under s 38. See generally Cox at [11]. For an example of the Tribunal considering arguments about good faith first, and reaching a conclusion that there was a lack of good faith, and therefore not proceeding with a s 38 inquiry, see Pathfinder Exploration Pty Ltd v Malarngowem Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC [2022] NNTTA 52.

82 I do not accept the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions in question 1. While the Tribunal certainly adverted (at [410]) to the time frame over which the question of Santos’ good faith negotiations should be assessed, the Tribunal did not limit itself to a consideration of whether Santos acted in good faith in making its offer in 2017. To the contrary, as the description above of the Tribunal’s reasoning demonstrates, the Tribunal carefully considered each of the stages of negotiations as articulated by the Gomeroi applicant in the way it put its case to the Tribunal, and considered good faith at each stage, and then, at the conclusion of its reasons, globally.

83 The difficulty confronting the Gomeroi applicant is that the Tribunal was not persuaded on the evidence before it that Santos knew (or even ought to have known, recalling the authorities above) that its offer as a whole, including the production levy component, was unfair, unrealistic or so far below comparable negotiation outcomes that it could be described as an offer not made in good faith.

84 The Tribunal found at [450]:

There is also a broader question as to the relevance of the valuation evidence to the question of Santos’s good faith. The Gomeroi applicant’s contention is that Mr Ho’s evidence and, to a lesser extent, that of Mr Meaton, in some way justify an inference that Santos deliberately made an offer which it knew was so “under value” as to demonstrate absence of good faith. In effect, the Gomeroi applicant asserts that the views attested to by Mr Meaton and by Mr Ho were reflective of the relevant state of knowledge (presumably that of Santos or, perhaps, the public) at all relevant times. There is no evidence to that effect. Even without Mr Kreicbergs’ evidence of Santos’s other transactions, I would have concluded that the Gomeroi applicant’s valuation evidence lacked probative value. However, Mr Kreicbergs’ evidence puts the matter beyond doubt. See his affidavit at paras 87-93 and exhibit HK-14. I do not understand his evidence to be challenged. It constitutes a coherent explanation of other transactions in which Santos has been involved. In my view, in light of such evidence, there is no basis upon which it can be asserted that Santos ought to have known about, and acted upon opinions such as those allegedly held by Mr Meaton and Mr Ho.

85 Mr Kreicbergs was at the relevant time the Manager Cultural Heritage, Aboriginal Engagement & Land for Santos. His evidence set out a table of what he described as “the evolution of Santos' offers to the Gomeroi Applicant”.

86 Mr Kreicbergs deposes (at [88] of his affidavit):

Each of the offers made to the Native Title Party during the course of the negotiations was the highest ever made for an onshore gas project in Australia in Santos' history at the relevant time. The total monetary amount payable to the Gomeroi Applicant is estimated to be approximately $36 - $50 million over the life of the Project. Although it is only possible at this stage to provide an estimate of the total monetary amount payable, even if the actual total monetary amount were at the bottom end of the range, it would be the highest amount paid to a native title group in Santos' history.

87 On appeal, the Tribunal’s statement at [343] of the determination that this evidence was not challenged was not said to be incorrect.

88 Mr Kreicbergs then set out another table, clearly intended to address the evidence of Mr Ho and the report of Mr Meaton, in which he described the summarised benefits in other agreements with native title groups that he considered were “relevant” to the offers made to the Gomeroi applicant. These were a narrower group of agreements than the ones relied on by Mr Ho and Mr Meaton, but Mr Kreicbergs justified why he had narrowed the group down. Mr Kreicbergs also deposed that Santos negotiates with native title groups in Queensland by using a “mature benchmark”, and that “a royalty payment in Queensland is unusual and does not fit into the normal benchmark for Santos”. He also deposed (at [93] of his affidavit), that outside Santos’ own agreements, he was not:

aware of any other agreements made between other resource companies and native title groups as they are confidential and not publicly available.

89 It is true that the Gomeroi applicant’s case was that information about such other agreements was available, through the evidence of Mr Ho and the report of Mr Meaton, and Santos and Mr Kreicbergs were ignoring this. However, the strength of that contention depended upon how reliable and persuasive the evidence of the Gomeroi applicant’s experts was to the Tribunal, and whether the alleged comparisons were objectively justifiable. Obviously, there was not a complete failure by Santos to take the material produced by Mr Meaton and Mr Ho into account because Mr Meaton’s report had been given to Santos in or around May 2017 and Mr Ho’s report would have been considered by Santos as part of the proceedings before the Tribunal. Santos had considered both reports and rejected the conclusions expressed in them. Santos did not agree with the relevance of the material to the terms of its offer; and considered its offer to be within reasonable bounds. As the Tribunal found (at [345], [452], [458] and [459]), as a negotiation party, Santos did not have to agree to other terms or agree to change its offer in order to act in good faith.

90 Mr Kreicbergs’ affidavit evidence (from [95]-[100]) also explained the rationale behind the differences in Santos’ offers to non-native title party landowners and native title party landowners, and explained why a wider range of benefits were included in agreements with a native title party.

91 Again, the Tribunal assessed this evidence and was not persuaded by the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions that there was a lack of honesty or fair dealing in Santos’ approach. Contrary to the Gomeroi applicant’s submissions, it is clear from the Tribunal’s reasons that it assessed Santos’ position for good faith well beyond the time its offer was first made.

92 Mr Kreicbergs’ evidence also explains the Tribunal’s finding at [411] that there was:

no evidence from which it could be inferred that Santos was aware of the information concerning the comparable projects and associated agreements, upon which Mr Ho’s evidence is based. In those circumstances, I cannot infer that Santos failed to negotiate in good faith.

93 The factual finding in paragraph [411] was not impugned as part of any argument on the questions of law. Even if it was implicitly challenged on appeal, the Court was not taken to any evidence or cross-examination of Mr Kreicbergs that could support a finding that the Tribunal erred in making this finding and drawing the inference it did. However, the bigger point is that on this issue of the approach taken by Santos, especially to what it would offer in light of its other engagement with landholders, the Tribunal was simply not persuaded that Santos’ conduct in light of the evidence of Mr Ho and the report of Mr Meaton demonstrated a lack of good faith, and was instead persuaded by the evidence of Mr Kreicbergs.

94 The Gomeroi applicant’s submissions on question 1 have not persuaded me that there was any error in the Tribunal’s approach, in terms of either a failure to look at Santos’ negotiating positions over the relevant period in a ‘global’ way, or in terms of the Tribunal’s approach to the reasonableness issue, to which I now turn.

95 It can be accepted that, in some circumstances, in performing its function under s 38, including whether it is precluded from making any determination by reason of s 36(2), read with s 37(a), the Tribunal may need to make some kind of assessment about whether the position adopted by a negotiation party said not to have acted in good faith involved an offer that was objectively reasonable. In Walley at [14]-[15] Carr J referred to the observations of R D Nicholson J in Strickland where his Honour had said that for the Tribunal to assess whether an offer was a reasonable offer requires “a further and unnecessary level of complexity and application to the interpretation of the words of s 31(1)(b)”. Carr J expressed a “reservation” to R D Nicholson J’s proposition, observing (at [15]):

if a Tribunal, as part of the overall assessment of whether the Government party has negotiated in good faith, finds it useful to consider whether any particular offer (or all offers for that matter) appears (or appear) to be reasonable, then it is open to the Tribunal to engage in that exercise. But that is not to say that it will always be obliged to do so. Much will depend on the circumstances of the particular matter. The Tribunal will be engaged on a factual assessment of the Government party’s conduct and, in some cases, the reasonableness or unreasonableness of its proposals or offers may be relevant. In other cases there may be a difference between making reasonable offers and being reasonable in negotiating in good faith. As the Tribunal noted in Strickland (WF 97/4) the Tribunal is engaged at that stage of its proceedings in deciding a preliminary issue of good faith. In that context, concepts of reasonableness would not exclude the Government party from giving priority to interests of State and not agreeing to proposed concessions.

96 I respectfully agree with Carr J’s observations. They are not inconsistent with the observations of R D Nicholson J, whose attention was primarily directed to ensuring a Tribunal did not become bogged down in its own assessment of whether an offer was “reasonable”, and thus diverting its focus from the good faith constraint. The Tribunal is after all doing no more at the good faith constraint stage than assessing the course of a negotiation, and measuring it objectively against a standard of honesty, open mindedness and willingness to listen. The fact of the making of a patently unreasonable offer in particular circumstances might be one indicia of a lack of honesty and fair dealing. It might indicate an ulterior motive. Or it may not. All will depend on the evidence and the circumstances.

97 In the present circumstances, in my opinion all the Tribunal did at [410] was to explain why, on the evidence, it did not assess Santos’ conduct in the offer(s) made as involving a position so inherently unreasonable as to indicate an ulterior motive, a lack of honesty or an unwillingness to deal fairly and with an open mind with the Gomeroi applicant.

98 Question 1 should be answered against the Gomeroi applicant’s contentions.

Question 2: the meaning of “payment” and “compensation”

99 Paragraph [2] of the further amended notice of appeal states:

2 On a proper construction of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the Act) is a “payment” in Division 3 of Part 2 of the Act synonymous with “compensation” in Division 5 of Part 2 of the Act?

Grounds

The Tribunal erred in finding that:

(a) payment agreed pursuant to the right to negotiate is compensation within the meaning of s.53 of the Act (at [279]);

(b) the “production levy” was a payment proposed to be made by way of compensation for “effect” or “impact” on native title (at [273], [279], [429]-[431]); and

(c) by reference to s.31 (2) of the Act, that negotiations for payment under the right to negotiate were not the subject of the requirement for negotiation in good faith under s.31(1)(b) of the Act unless the negotiations related to compensation for the anticipated “effect” of a proposed future act on native title rights and interests (at [273]) or “impairment” or “impact” on native title (at [277], [279], [329], [347]-[348], [409], [419], [429], [430], [431], [439], [444], [465] and [518]) because no such limitation forms part of the Right to Negotiate and in particular s.33(1) of the Act;

because those findings are neither consistent with the Act, nor available on the evidence that was before the Tribunal.

100 As the question reveals, this is a challenge to a number of paragraphs of the Tribunal’s determination. However, it was not suggested that as between these paragraphs the Tribunal took any internally different or inconsistent approach and so they can generally be considered together.

101 The question, senior counsel submitted, is whether the statutory term “payment” in s 33(1) is synonymous with the statutory term “compensation” in Division 5 of Part 2 of the NTA. The Gomeroi applicant submits that the two terms are not synonymous but the Tribunal treated them as if they were, in substance requiring that a payment referred to in s 33(1) must have a connection to an impact or effect on native title rights and interests. Senior counsel used, as an example of the alleged error, paragraph [279] of the Tribunal’s determination:

The negotiation prescribed by s 31(1) of the Native Title Act does not involve concepts such as “fair value” or a “free market”. Nor is there any indication as to the subject matter of any valuation exercise. The section requires that the parties negotiate in good faith with a view to reaching agreement as to the proposed grants. No doubt, such negotiation is likely to involve consideration of financial aspects, but there is no indication as to the nature of such aspects, or as to how they may be calculated. Given the frequent references to compensation in the evidence, it would seem that any financial aspect would be compensation for impairment of native title, a matter which was considered by the High Court in Northern Territory v Griffiths. However, as far as one can see, there has been no attempt to compare the extent of any impairment of the Gomeroi people’s native title rights and interests with the extent of any impairment in the various comparable projects which have been taken into account in the reports of either Mr Meaton, Mr Ho, or both.

(Emphasis added.)