Federal Court of Australia

SARB Management Group Pty Ltd T/A Database Consultants Australia v Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited [2024] FCAFC 6

ORDERS

SARB MANAGEMENT GROUP PTY LTD T/A DATABASE CONSULTANTS AUSTRALIA ACN 106 549 722 Appellant | ||

AND: | VEHICLE MONITORING SYSTEMS PTY LIMITED ACN 107 396 136 First Respondent CITY OF MELBOURNE Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 21 days, the parties confer and supply to the chambers of Justice Burley draft short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons.

2. Insofar as the parties are unable to agree to the terms of the draft short minutes of order referred to in order 1, the areas of disagreement should be set out in mark-up.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[1] | |

[7] | |

[10] | |

[10] | |

[12] | |

[36] | |

[37] | |

[37] | |

[38] | |

[49] | |

[52] | |

[66] | |

[66] | |

[69] | |

[74] | |

[77] | |

[86] | |

[86] | |

[87] | |

[87] | |

[97] | |

[99] | |

[112] | |

[120] | |

[137] |

THE COURT:

1 This appeal is the next stage in a lengthy arm wrestle between the parties concerning the rights to the intellectual property in systems for vehicle overstay detection in car parks. The hearing before the primary judge related to numerous issues concerning the construction, infringement and validity of two patents, both entitled “Method, apparatus and system for parking overstay detection”: Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd trading as Database Consultants Australia (No 8) [2023] FCA 182. However, the present appeal is of more limited scope.

2 The appellant, SARB Management Group Pty Ltd challenges first, the primary judge’s finding that claims 21, 30, 31 and 32 of Australian Patent No 2005243110 (first patent) are infringed by its vehicle overstay detection system known as Pinforce Version 3 and, secondly, the finding that the specification of the first patent and Australian Patent No 2011204924 (second patent) did not fail to disclose the best method known to the inventor in contravention of s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act). The first patent and second patent together are referred to as the patents.

3 The respondents are Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd (VMS) and the City of Melbourne. The City of Melbourne was a respondent to the proceedings below and, together with SARB, was found to have infringed various claims of the patents. It has not filed a Notice of Appeal and was excused from the hearing on the basis that it did not wish to be heard, save as to costs.

4 The grounds of appeal relied upon by SARB are that the primary judge erred in holding that:

(1) claim 21 of the first patent includes a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus (or DCA);

(2) claims 30, 31 and 32 of the first patent include a method, apparatus or system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus; and

(3) SARB had not established that the patents fail to describe the best method known to VMS of performing the invention at the time of filing applications for the patents.

(particulars omitted)

5 VMS has filed a Notice of Contention contending:

(1) in respect of the construction of claim 21 of the first patent: (a) it was open to the primary judge to find that there was no ambiguity in the text of claim 21; and (b) the primary judge ought to have accepted VMS’s construction of the final integer of claim 21 for the additional reason that the ordinary language used in the claim is broad and clear enough to include a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the DCA; and

(2) alternatively to the reasons for which the primary judge found in VMS’s favour on claim 21 (and accordingly on claims 30, 31 and 32), and to ground 1 above, the primary judge ought to have accepted VMS’s construction of claims 30, 31 and 32 of the first patent, regardless of whether VMS was correct about the construction of claim 21 of the first patent.

6 The relevant version of the Act and Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth) for the purpose of this proceeding is that in force prior to the amendments made to the Act by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) and the Intellectual Property Legislation Amendment (Raising the Bar) Regulations 2013 (No 1) (Cth).

7 The careful decision of the learned primary judge traversed many issues not the subject of the present appeal. His Honour concluded that two products made and sold by SARB, referred to as Pinforce Version 1 and Pinforce Version 2, infringed numerous claims of the patents. It is not necessary to refer to those findings further. In relation to a third product made and sold by SARB, Pinforce Version 3, his Honour declared that SARB had infringed claims 21 to 23 and 32 of the first patent and made orders dated 21 June 2023 (Orders) restraining further infringement. He ordered that SARB pay VMS’s costs of the application and cross-claim and made directions that there be an enquiry as to the quantum payable by reason of the infringements so found. Various of those Orders were stayed pending appeal.

8 For the reasons set out below, we have found that the primary judge erred in relation to his conclusions concerning claims 21 and 30 – 32 of the first patent but not in relation to his rejection of the challenge to the validity of the patents on the basis of VMS’s failure to describe the best method of performing the invention within s 40(2)(a) of the Act. We have rejected the arguments raised in the Notice of Contention.

9 The consequence is that it will be necessary to set aside some of the Orders made by the primary judge. Having regard to the outcome of the appeal, we consider that VMS should pay SARB’s costs of the appeal. We will direct that the parties confer and within 21 days supply to the chambers of the presiding judge draft short minutes giving effect to the reasons set out below, marked up to indicate any areas of disagreement.

10 The patents are both entitled “Method, apparatus and system for parking overstay detection”. Leaving aside the claims and the consistory clauses, the specification is materially the same in each. The priority date for both is 17 May 2004.

11 The parties proceeded, as the primary judge did, on the basis that for the purposes of the arguments before the Court, it is sufficient primarily to consider the language used in the first patent. Accordingly, it is to the terms of that patent that we refer below.

12 The first patent identifies the field of the invention as relating to parking violations and, more particularly, to the detection of vehicles that overstay a defined time interval in parking spaces.

13 In the section in the specification entitled “Background”, existing methods of detecting vehicles that have exceeded the time limit of a parking space are described. A traditional method of placing a chalk mark on the tyre of each of the vehicles in a specified zone and then returning at a later time to check if any of the vehicles with “chalked” tyres are still parked is described. The disadvantages said to be associated with that method are identified and then a statement is made that a need thus exists for a method, an apparatus and a system that overcomes, or at least ameliorates, one or more of the described disadvantages.

14 In the “Summary” section of the specification, three aspects of the invention are described in terms that, the primary judge found, and the parties agree, broadly correspond with claims 1, 11 and 21 respectively.

15 The first aspect concerns a method (page 2 lines 5 – 11):

According to an aspect of the present invention, there is provided a method performed by a subterraneous detection apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. The method comprises the steps of detecting presence of a vehicle in the parking space, processing and storing data relating to presence of the vehicle in the parking space, determining whether the vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in the parking space, and wirelessly transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

16 The second aspect concerns an apparatus (page 2 lines 13 – 21):

According to another aspect of the present invention, there is provided a battery-powered apparatus for a battery-powered apparatus for subterraneous installation for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. The apparatus comprises a detector adapted to detect presence of a vehicle in the parking space, a processor coupled to the detector for processing and storing data received from the detector and determining whether the vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in the parking space, a radio receiver coupled to the processor for receiving wake-up signals, and a radio transmitter coupled to the processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

17 The third aspect concerns a system (page 2 line 23 – page 3 line 2):

According to another aspect of the present invention, there is provided a system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces. The system comprises a plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses for identifying overstay of vehicles in respective parking spaces when subterraneously installed, and a data collection apparatus for wirelessly retrieving data from the plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses. The data collection apparatus comprises a radio transmitter for transmitting wake-up signals to ones of the plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses, a radio receiver for receiving data from woken-up ones of the plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses, a memory unit for storing data and instructions to be performed by a processing unit, and a processing unit coupled to the radio transmitter, the radio receiver and the memory unit. The processing unit is programmed to process the data received via the radio receiver and to indicate incidences of vehicle overstay to an operator. The data relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay in a respective parking space.

18 The specification continues (page 3 lines 4 – 20):

Repeated wireless wake-up of a detection apparatus is typically performed irregularly with respect to time depending on the presence of a data collection device. Wireless retrieval of data may be performed in response to wireless wake-up of a detection apparatus. Overstay of a vehicle in a parking space may be determined at the detection apparatus by processing data received from the detector.

The data collection apparatus may be portable and may retrieve the data from the detection apparatus whilst the data collection apparatus is located in a moving vehicle. Data relating to presence of a vehicle may comprise presence duration of the vehicle in the parking space, movements of the vehicle in and out of the parking space with corresponding time-stamp information, and/or an indication of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space. Vehicle presence detection may be performed by a magnetometer that detects changes in the earth’s magnetic field caused by presence or absence of a vehicle in the parking space. The detection apparatus may be encased in a self-contained, sealed housing for subterraneous installation in the parking space. The radio transmitter and/or radio receiver may operate in the ultra-high frequency (UHF) band and may jointly be practiced as a transceiver.

19 There follows a brief description of nine drawings which are identified as embodiments “by way of example only”. The “Detailed Description” then describes methods, apparatuses and systems for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces.

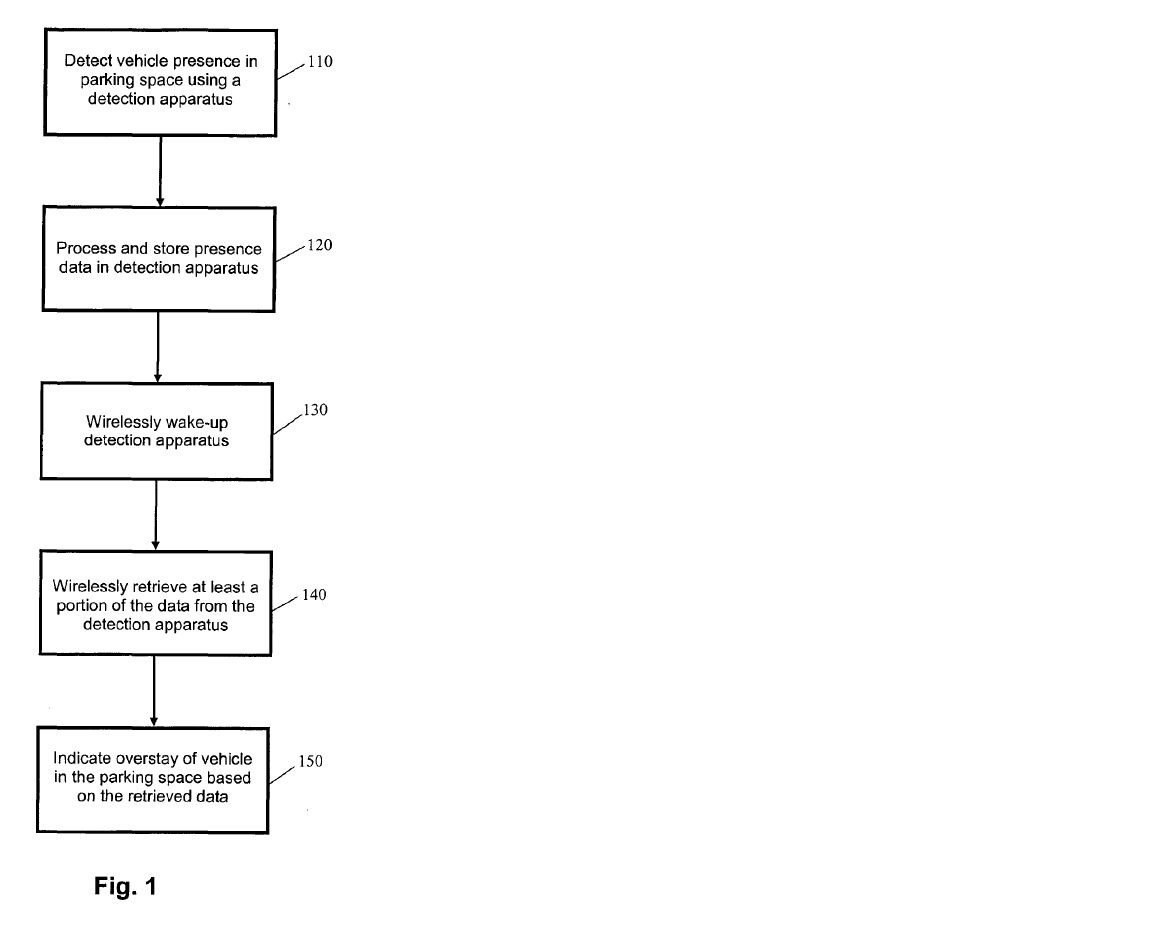

20 Figure 1 is identified as a flow diagram of a method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space:

21 It is described in the following terms (page 4 lines 12 – 18):

Fig. 1 is a flow diagram of a method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space. Presence of a vehicle in the parking space is detected using a detection apparatus in step 110. Data relating to presence of the vehicle is processed and stored in the detection apparatus at step 120. The detection apparatus is wirelessly woken-up at step 130 and at least a portion of the data is retrieved from the detection apparatus at step 140. Overstay of the vehicle in the parking space is indicated based on the retrieved data at step 150.

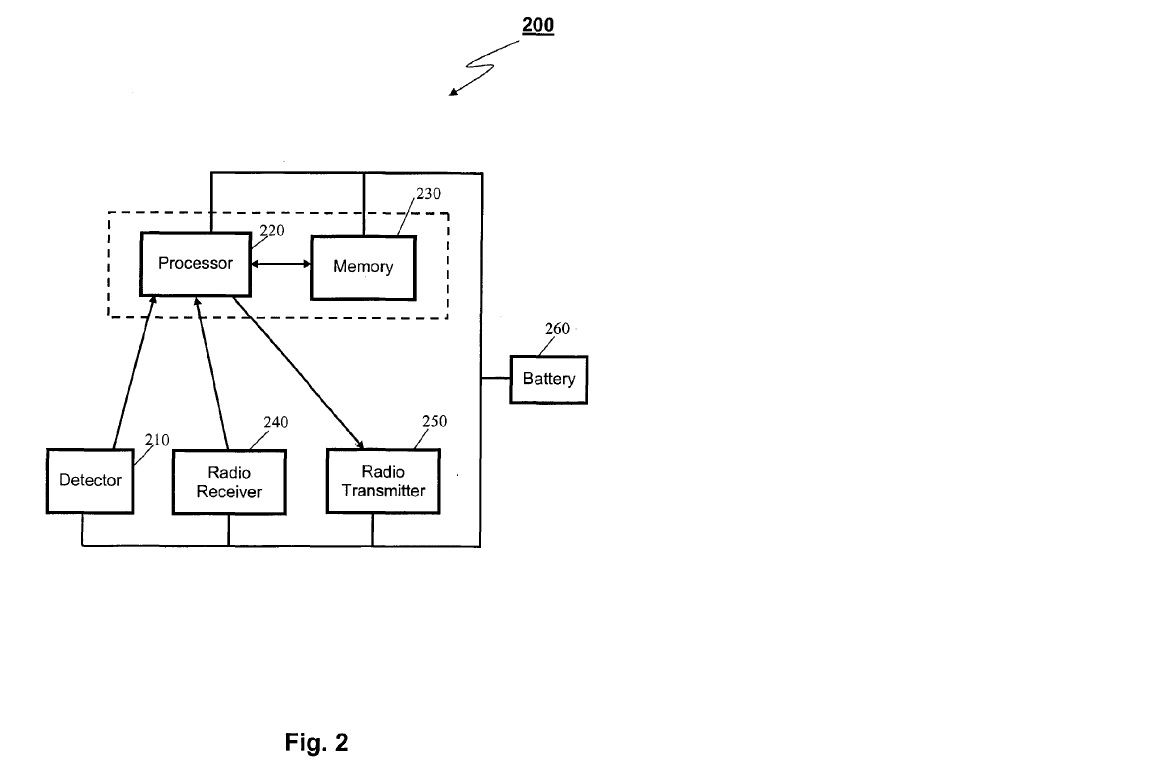

22 Figure 2 is identified as a block diagram of a detection apparatus 200 for monitoring presence of a vehicle in a parking space:

23 It is described over several pages of the patent. The description commences (page 4 lines 20 – 30):

Fig. 2 is a block diagram of an apparatus 200 for monitoring presence of a vehicle in a parking space. The apparatus comprises a detector 210 for detecting presence of a vehicle in the parking space, a processor 220 for processing data received from the detector 210, a memory 230 for storing data before and after processing, a radio receiver 240 for receiving a wake-up signal from a data collection apparatus located remotely from the parking space, a radio transmitter 250 for transmitting at least a portion of the data to the data collection apparatus, and a battery 260 for powering each of the detector 210, the processor 220, the memory 230, the radio receiver transmitter 240, and the radio transmitter 250. The processor 220 and the memory 230 may be integrated in a single device such as a microprocessor or microcontroller. The processor 220 is coupled to each of the detector 210, the memory 230, the radio receiver 240, and the radio transmitter 250.

24 After describing that in one particular embodiment, the detector 210 comprises a magnetometer of a certain type and noting that other sensing devices may be used, the specification identifies that the processor 220 may include a Texas instruments MSP430 16-bit microcontroller, or other microprocessors or microcontrollers of the type that the person skilled in the art would identify.

25 It is relevant to the ground of the appeal concerning best method to note that on page 5 at lines 22 – 30 the specification provides the following in relation to the radio receiver 240:

The radio receiver 240 and radio transmitter 250 are practised as a 433 MHz ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio transceiver for transmitting and receiving radio signals to and from a data collection apparatus, respectively. Various UHF transceivers may be practised such as the Micrel MICRF501 transceiver, which requires to be turned on for approximately 1ms before RF carrier energy can be detected. However, persons skilled in the art would readily understand that other types of transmitters, receivers or transceivers may be practised such as low frequency (LF) transceivers. Other UHF frequencies may also be practised such as in frequency bands commonly used for low powered devices, including 868 MHz, 915 MHz and 2.4 GHz.

26 The specification then describes a type of battery 260 that may be used.

27 The specification notes of the detection apparatus (or DA) 200 (page 6 lines 1 – 7):

The apparatus 200 generally operates in a low-power mode while detecting vehicle movements and presence in a corresponding parking space, which may be practised on a continuous or periodic (e.g., interrupt driven) basis to conserve battery life. Although the radio receiver 240 of the apparatus 200 consumes a small amount of power (relative to other radio receivers), the radio receiver 240 is only turned on for the shortest possible time duration at regular intervals to detect the presence of a data collection apparatus. At other times, the radio receiver 240 is turned off to conserve battery life.

28 The specification then notes details of the detection apparatus 200, which may be a cylindrical shape and buried in the centre of the parking space that is to be monitored. It goes on to describe aspects of the operation of the apparatus 200 in certain embodiments (page 6 line 28 – page 7 line 20):

In one embodiment, the apparatus 200 determines and maintains three primary types of information:

• Current Status

The current status of the parking space in terms of vehicle presence (i.e., present or not present) and the amount of time the space has remained in the present state.

• Historical Vehicle Movements

A record of each vehicle movement in the parking space including the date and time of the movement.

• Overstay Situation

Detected when a vehicle remains in said parking space for a duration longer than a defined time interval.

The apparatus 200 may optionally be programmed with information relating to the hours of operation and parking time limits that apply to an associated parking space based on the time of day and day of week. Decisions concerning overstay can thus be made by the apparatus 200 based on different time limits that may apply to the parking space at different times.

Information may also be downloaded to the apparatus 200 using a radio receiver in the apparatus 200. The same radio receiver as used for receiving wake-up signals or a separate radio receiver may be used for this purpose. The downloaded information may comprise, but is not limited to:

• application firmware for the apparatus 200,

• a table of operating hours and time limits (time of day and day of week) applicable to an associated parking space,

• operating parameters for the apparatus 200, and

• information for updating or synchronising the real-time clock with a more accurate real-time source.

29 In a passage that is important to the construction grounds of the appeal and the Notice of Contention, the patent specification provides at page 7 lines 21 – 23:

Alternatively, decisions relating to vehicle overstay can be made by a data collection apparatus that collects data from the apparatus 200 via a radio communication link rather than by the apparatus 200.

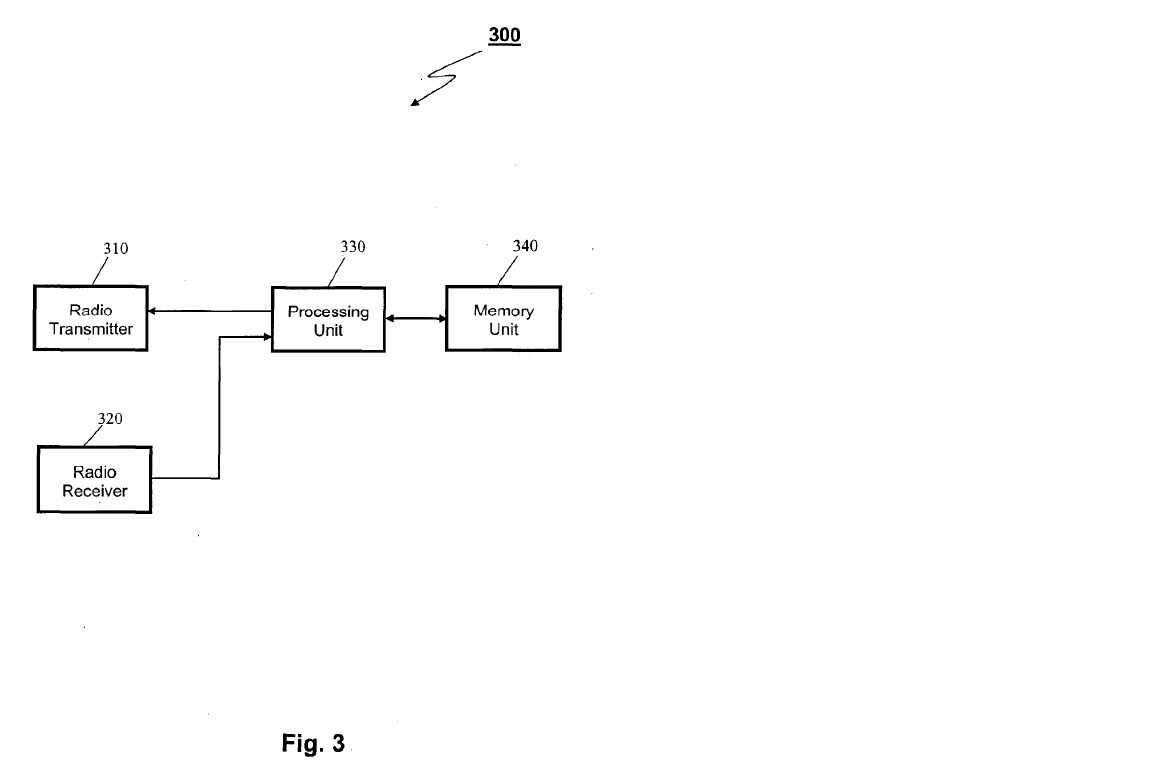

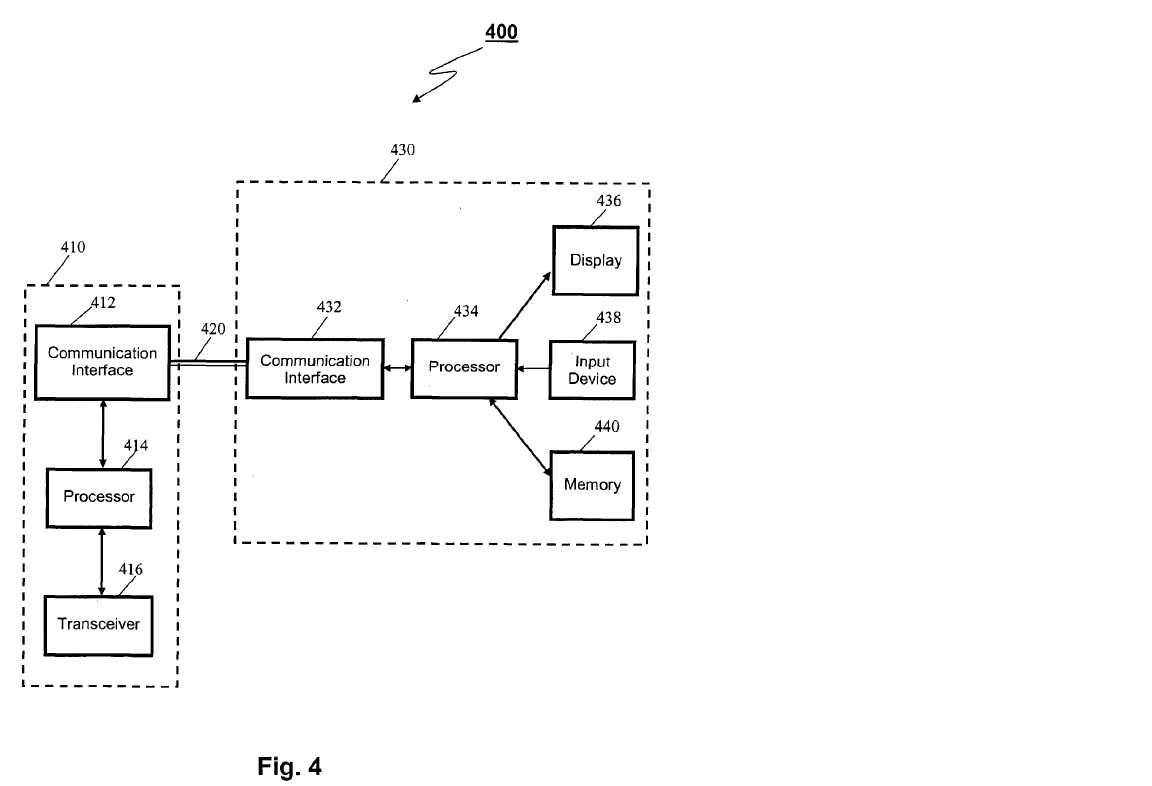

30 Figures 3 and 4 are block diagrams of a data collection apparatus for retrieving data from one or more detection apparatuses:

31 The description provides (page 9 lines 1 – 10):

The data collection apparatuses 300 and 400 typically provide the following functionality:

• Wake up all the monitoring units within an immediate vicinity or wake up individual monitoring units on a selectively addressable basis,

• Enquire if a vehicle presently parked has overstayed an allowed time limit,

• Enquire as to the current status of parking space, and

• Collect historical vehicle movement data.

A data collection apparatus may be enabled to collect all or only a limited subset of the information available from a monitoring apparatus.

32 The description provides that the data collection apparatuses 300 and 400 may be implemented as portable hand-held apparatuses for operation by an enforcement officer or as a vehicle-mounted apparatus (page 9 lines 10 – 20). In relation to its function, it provides that (page 9 lines 21 – 24):

A data collection apparatus transmits a wake-up signal (e.g., RF carrier followed by a defined message) and listens for valid responses from detection apparatuses. If no response is received from a detection apparatus, the data collection apparatus repeatedly transmits the wake-up signal.

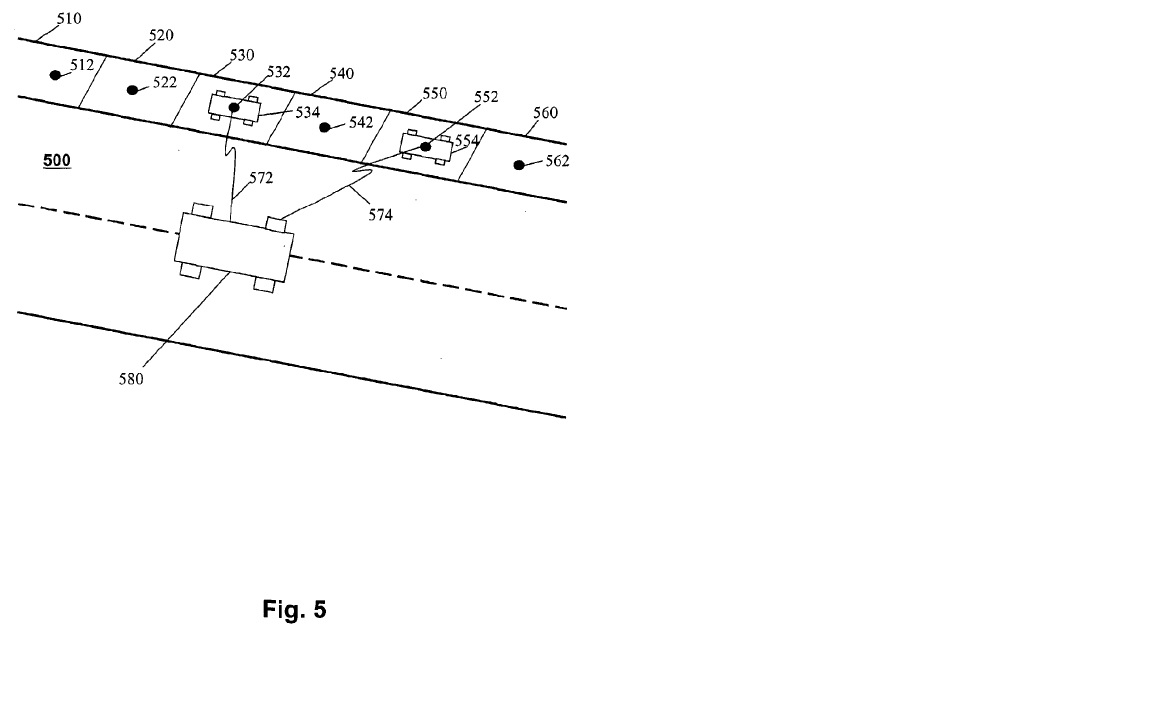

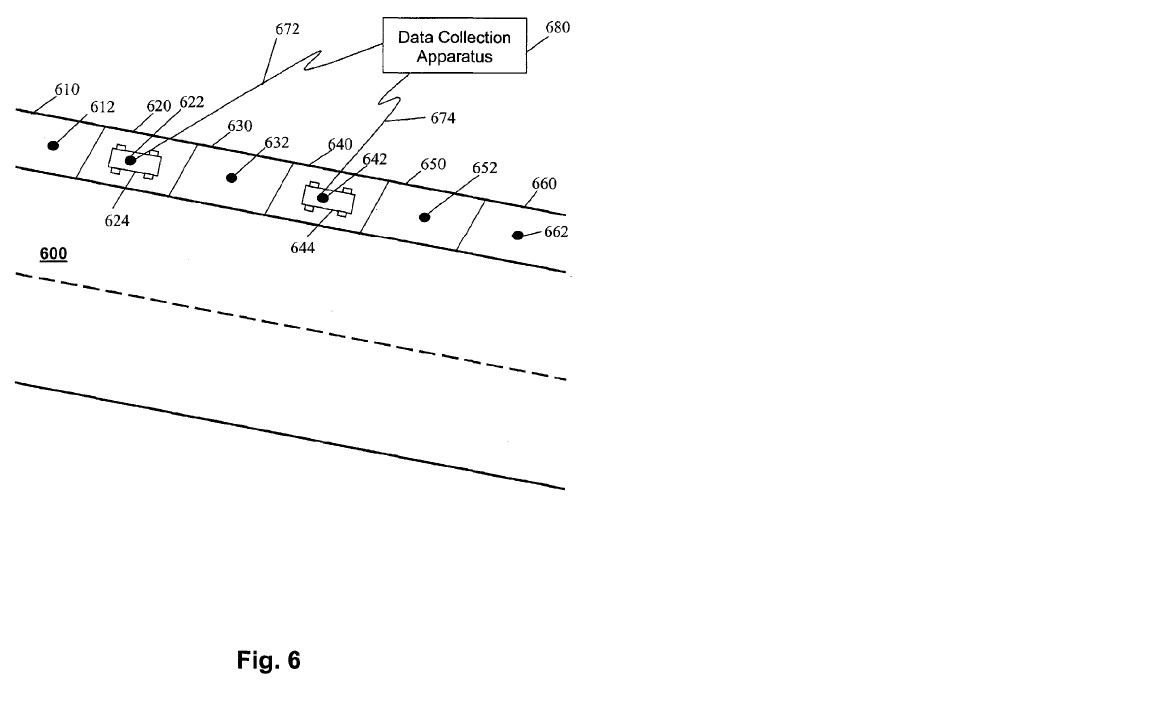

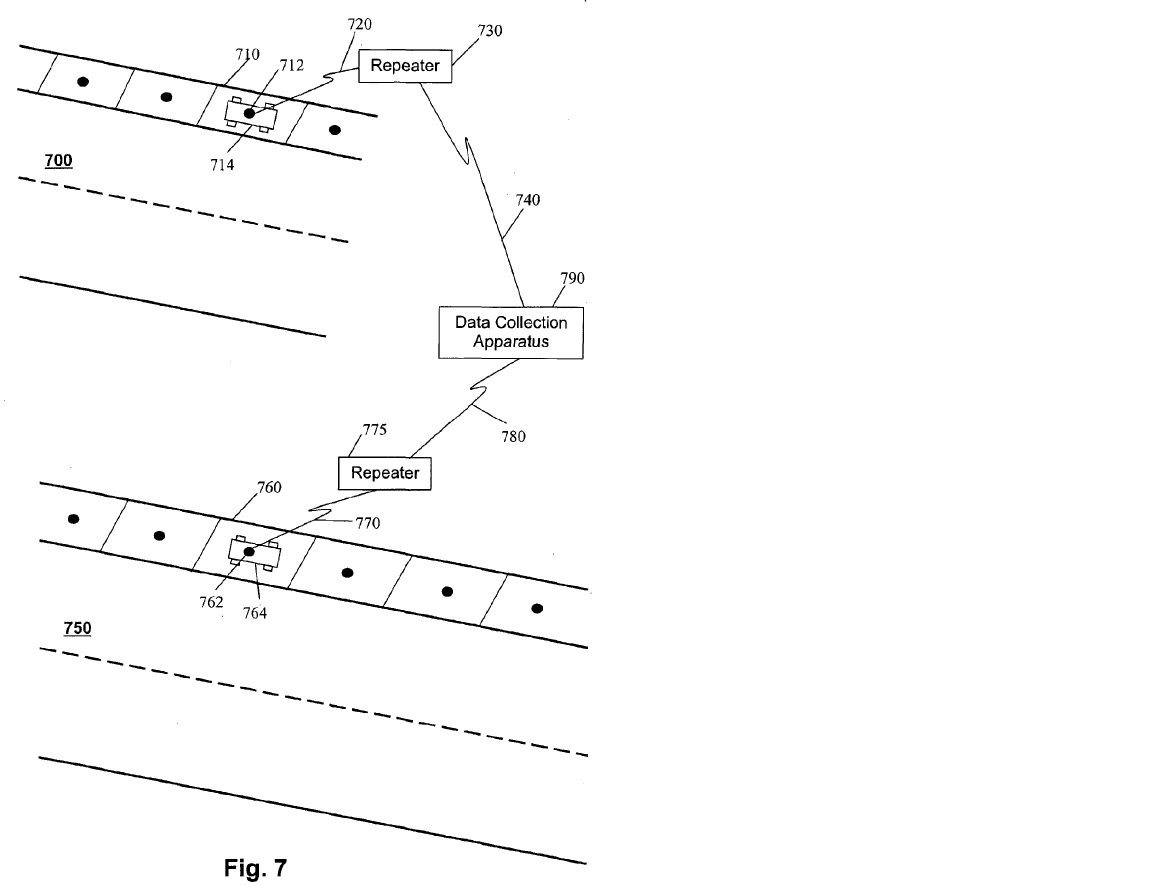

33 Figures 5, 6 and 7 are referred to as schematic diagrams of systems for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces:

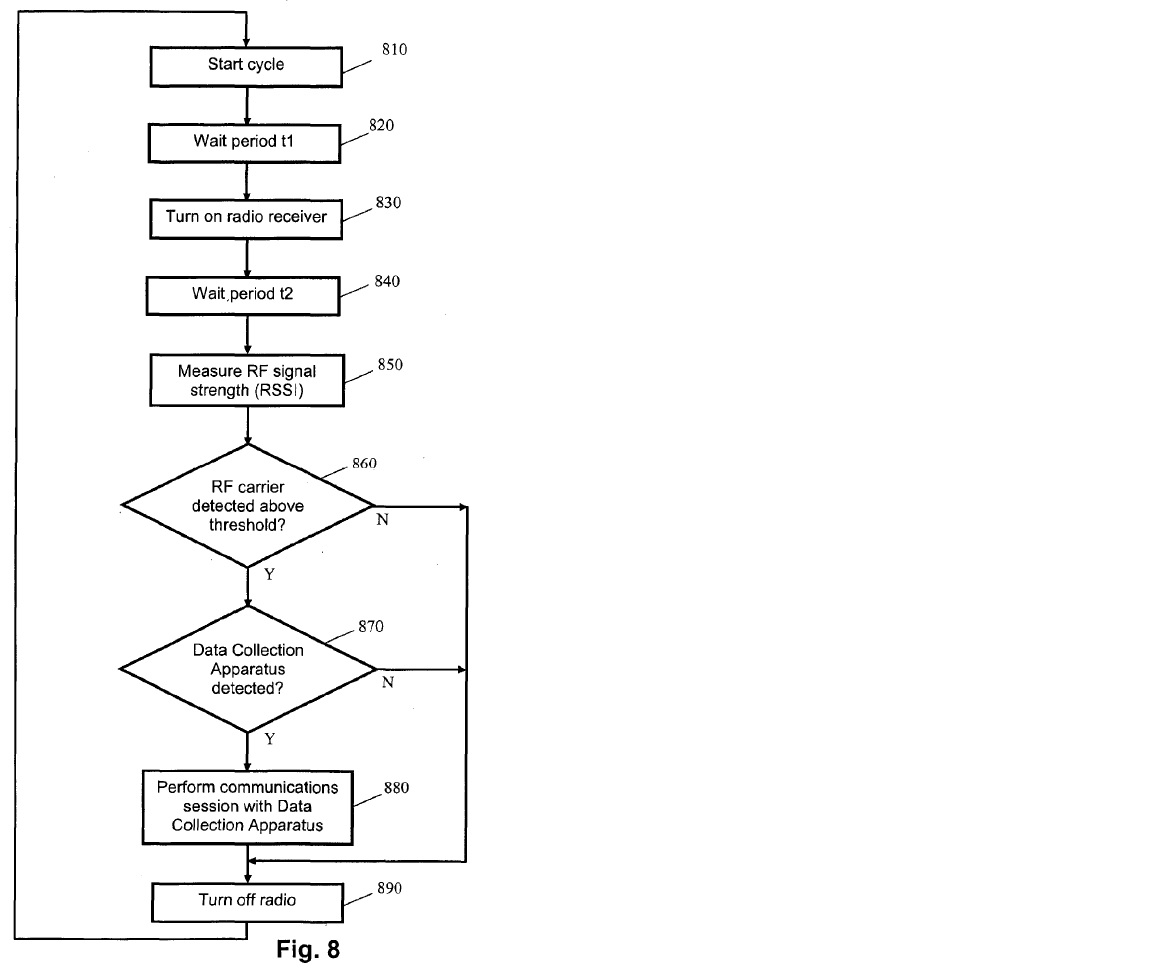

34 Figure 8 provides a flow diagram of a method of operating a detection apparatus:

35 It is described in the specification at page 11 lines 10 – 31 as follows:

Fig. 8 is a flow diagram of a method of operating a detection apparatus such the apparatus 200 in Fig. 2. A cycle of operation begins at step 810. After a wait period of duration t1 at step 820, the radio receiver is turned on at step 830. After a further wait period of duration t2 at step 840, for the radio receiver to stabilise, the received radio frequency signal strength (RSSI) is measured at step 850. At step 860, a determination is made whether the signal strength of a detected RF carrier is larger than a defined threshold. If an RF carrier of sufficient signal strength is detected (Y), a determination is made at step 870 whether the RF carrier relates to a data collection apparatus. If a data collection apparatus is detected (Y), a communications session between the detector apparatus and the data collection apparatus occurs at step 880. Such a session typically involves transmission and reception by both the detector apparatus and the data collection apparatus. The radio receiver and transmitter are turned off at step 890 and a new operation cycle begins at step 810.

If an RF carrier of sufficient signal strength is not detected (N), at step 860, the radio receiver is turned off at step 890 and a new operation cycle begins at step 810.

If a data collection apparatus is not detected (N), at step 870, the radio receiver is turned off at step 890 and a new operation cycle begins at step 810.

The duration t2 is determined according to the type of radio receiver used and is typically of the order of 1 millisecond. Setting the duration t1 to 250 milliseconds implies an on:off duty cycle of 1:250. A typical low-power receiver may consume 5 to 10mA in receiver mode and the average power consumption of the data collection apparatus detection process is thus 20 to 40 µA.

36 The claims most relevant to consideration of the issues on appeal are set out below. Integer numbers have been added for ease of reference.

1. [1] A method performed by a subterraneous detection apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said method comprising the steps of:

[2] detecting presence of a vehicle in said parking space;

[3] processing and storing data relating to presence of said vehicle in said parking space;

[4] determining whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space; and

[5] wirelessly transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space.

…

11. [1] A battery-powered apparatus for subterraneous installation for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said apparatus comprising:

[2] a detector adapted to detect presence of a vehicle in the parking space;

[3] a processor coupled to said detector, said processor adapted to process and store data received from said detector and [4] to determine whether said vehicle has overstayed a defined time duration in said parking space;

[5] a radio receiver coupled to said processor for receiving wake-up signals; and

[6] a radio transmitter coupled to said processor for transmitting data relating to identified instances of overstay of said vehicle in said parking space.

…

21. [1] A system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces, said system comprising:

[2] a plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses for identifying overstay of vehicles in respective parking spaces when subterraneously installed; and

[3] a data collection apparatus for wirelessly retrieving data from said plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses, said data collection apparatus comprising:

[4] a radio transmitter for transmitting wake-up signals to ones of said plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses;

[5] a radio receiver for receiving data from woken-up ones of said plurality of battery-powered detection apparatuses;

[6] a memory unit for storing data and instructions to be performed by a processing unit; and

[7] a processing unit coupled to said radio transmitter, said radio receiver and said memory unit;

[8] said processing unit programmed to process said data received via said radio receiver and to indicate incidences of vehicle overstay to an operator;

[9] said data relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay in a respective parking space.

…

30. A method performed by a subterraneous detection apparatus for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said method substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings.

31. A battery-powered apparatus for subterraneous installation for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space, said apparatus substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings.

32. A system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces, said system substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings.

37 SARB contends that the primary judge erred in construing claim 21 of the first patent to include a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus rather than solely by the detection apparatus.

3.2 The relevant reasoning of the primary judge

38 The primary judge commenced by providing a summary of the evidence given by the expert witnesses, Mr Spirovski, an electrical engineer who was called by VMS, and Mr Harcourt, who has qualifications in mechanical engineering and electronics and communication engineering, who was called by SARB. There was no challenge to the expertise of either witness. Both expert witnesses agreed that the system disclosed in the first patent was capable of determining overstay in the data collection apparatus. However, they disagreed as to whether claim 21 discloses that the data collection apparatus performs the overstay determination (at [99]).

39 The primary judge addressed the construction of claim 21 at [85] – [154] of his reasons.

40 As a starting point, his Honour considered the text of claim 21 and made the following central observations:

123 The chapeau in claim 21 provides that the claim is for a system for identifying overstay of vehicles in parking spaces. That is the purpose of the system. All other things being equal, a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the DA and a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the DCA both have that purpose. Relatedly, I reject the suggestion that where vehicle overstay is determined by the DCA, there is no longer a DA which has the purpose of identifying the overstay of vehicles. The DA would still be performing a key role in the objective or purpose of the system.

124 The system comprises a plurality of DAs and a DCA. The DCA comprises a number of pieces of hardware for various purposes and it includes a processing unit programmed to process data received by the radio receiver of the DCA from the DA and to indicate incidences of vehicle overstay to an operator. In this particular context, “indicate” means to “show or make known” (Macquarie Dictionary (6th ed), 2013). To provide an indication of incidences of vehicle overstay is a function of the DCA.

125 The “said data”, that is, the data received by the DCA from the DA is data that “relates to” identified instances of vehicle overstay in a respective parking space. In ordinary usage, “relates to” is a broad phrase which indicates an association or a connection between two or more things. In this case, the connection must be between the data received by the DCA from the DA and identified instances of vehicle overstay in a respective parking space. Data falling short of a vehicle overstay determination such as vehicle presence data and a record of vehicle movement in the parking space, including the date and time of movement, is data relating to vehicle overstay, but is it data relating to “identified” incidences of vehicle overstay? In my opinion, there is an ambiguity in the phrase between data which includes the identified instances of vehicle overstay, that is, the determination of vehicle overstay and data which may lead to the identification of instances of vehicle overstay. In those circumstances, it is appropriate to consider the rest of the specification in order to resolve the ambiguity.

41 The primary judge then turned to the body of the specification, noting the three aspects of the invention described in the consistory clauses, the first being a method performed by the detection apparatus as set out in claim 1, the second being an apparatus (specifically the detection apparatus) as set out in claim 11 and the third being a system as described in claim 21. His Honour observed that in the first and second aspects, vehicle overstay is determined by the detection apparatus (at [126]).

42 His Honour considered three passages in the specification relied upon by VMS to support its construction that the determination of vehicle overstay made by the data collection apparatus is within the terms of claim 21. The first is a passage on page 3 lines 7 – 8 which says:

Overstay of a vehicle in a parking space may be determined at the detection apparatus by processing data received from the detector.

43 He noted the reliance on the word “may” as indicating that the detection apparatus also may not determine overstay, allowing for the possibility that the data collection apparatus could perform that function, but considered that this was a fairly weak point (at [109] and [129]).

44 The second is a passage on page 3 lines 10 – 20. The passage at lines 10 – 15 is extracted below:

The data collection apparatus may be portable and may retrieve the data from the detection apparatus whilst the data collection apparatus is located in a moving vehicle. Data relating to presence of a vehicle may comprise presence duration of the vehicle in the parking space, movements of the vehicle in and out of the parking space with corresponding time-stamp information, and/or an indication of overstay of the vehicle in the parking space.

45 VMS relied on the words “and/or” and indicated that the “and” admitted the possibility that all three pieces of information may be part of the data, and the “or” means that only one or two pieces of information may be part of the data (at [110] and [131]). If it was only the first two pieces of information, the determination of vehicle overstay would have to be made by the data collection apparatus. The primary judge noted (at [111]) an alternative interpretation of the above passage submitted by SARB, namely that the detection apparatus may send only an indication of the overstay of the vehicle in the parking space and not the other information or it may send the first two types of information, but not the third because there is no overstay of the vehicle. He also accepted (at [134]) that nothing in the passage expressly indicates that vehicle overstay may be determined by the data collection apparatus.

46 The third is the passage on page 7 which is included within the passages describing Figure 2, which is a block diagram of a detection apparatus. Of particular relevance is page 7 lines 21 – 23, extracted below:

Alternatively, decisions relating to vehicle overstay can be made by a data collection apparatus that collects data from the apparatus 200 via a radio communication link rather than by the apparatus 200.

47 In relation to the passage at lines 21 – 23, the primary judge rejected Mr Harcourt’s view that the reference in the passage to “decisions relating to vehicle overstay” does not mean determinations of vehicle overstay, but instead, refers to decisions made subsequent to determinations of vehicle overstay, such as decisions made by the parking officer. He said:

137 The context of the passage is provided by the passage which immediately precedes it rather than the passage which follows it.

138 After describing the various components of the DA and how it may be installed in or on the parking space, there is a description of one embodiment of the DA in which the three pieces of data or information are referred to and in this embodiment, it is clear that the DA determines vehicle overstay. Instruction is given as to the determination of overstay where different time limits apply to a parking space based on the time of day and day of week and as to the information which may be downloaded to the DA.

139 The relevant passage then appears. I will come to the construction of the passage shortly, but first I make clear the reason(s) why regard can be had to it in the proper construction of claim 21.

140 Claim 21 refers to DAs and that permits reference to the description of a DA in the detailed description of a DA in connection with Fig 2. Further, or in the alternative, reference to the detailed description of a DA is permitted by Fig 1 which is a flow diagram of a method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space and which refers to a DA.

141 As to the construction of the passage, I consider that “decisions relating to vehicle overstay” means, in context, determinations of vehicle overstay. That, to my mind, is the natural reading of the passage in context, including the reference in an earlier passage to “In one embodiment” and the use of “alternatively” and “rather than”. It follows that I reject Mr Harcourt’s interpretation of the passage which, with respect, I consider somewhat artificial and strained.

48 The primary judge expressed his conclusions in relation to the construction of claim 21 as follows:

143 As to Fig 1, there was not a significant difference between the experts with Mr Spirovski saying that under the method identified in Fig 1, either the DA or the DCA could determine vehicle overstay and Mr Harcourt saying that, in the case of the method shown in Fig 1, there was no requirement that vehicle overstay be determined by the DA and determination of vehicle overstay by the DCA is not explicitly ruled out.

144 In my opinion, the ambiguity in claim 21 should be resolved in holding that it includes a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the DCA having regard to the passage on p 7 and, to a lesser extent, the other passages relied on by VMS and Mr Spirovski.

49 SARB contends that the primary judge’s reasoning reflects error in four main respects. First, it submits that the primary judge failed to understand the phrases “for identifying overstay of a vehicle” and “data relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay” in claim 21 consistently with their ordinary meaning and the same language used in claims 1 and 11. In those claims, the phrases point to the detection apparatus as the (sole) device that performs the function of identifying overstay of vehicles because it alone is assigned that role. Additionally, the use of past tense in the term “identified” indicates that instances of overstay must have already been identified by the detection apparatus by the time the data is retrieved by the data collection apparatus. It thus follows that the same phrases as they appear in claim 21 ought to be given the same meaning. Secondly, it submits that the primary judge erred in finding that there was ambiguity in the language of claim 21 and subsequently that regard was had to the remainder of the specification to resolve the ambiguity. Thirdly, the regard paid by the primary judge to the passage on page 7 lines 21 – 23 of the specification in his construction of claim 21 on the basis that the reference to detection apparatuses in claim 21 permitted reference to the description of a detection apparatus in the detailed description was in error. SARB submits that this is because coincidence of language does not permit the importation into the words of the claim additional words in the specification which are not in the claim or the deployment of such words to interpret the claim. Fourthly, SARB submits that the primary judge erred in his construction of that passage.

50 VMS defends the reasoning of the primary judge. It submits, among other things, that the language of claims 1 and 11 are not relevantly similar to claim 21 so as to oblige the primary judge to conclude that in claim 21 the detection apparatus was the only part of the system that detected vehicle overstay. It also submits that the primary judge did not impermissibly expand the boundaries of VMS’s monopoly by adding glosses drawn from other parts of the specification to the words of the claim, but instead legitimately referred to the balance of the specification to resolve an ambiguity in the language of the claim, citing Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588. VMS also submits that SARB’s construction ignores the requirement that the claims are to be construed through the eyes of the skilled addressee and in the present case, both experts agreed that the system disclosed in the first patent is capable of determining overstay in the data collection apparatus.

51 By its Notice of Contention, VMS submits that the primary judge’s construction of claim 21 is correct for alternative reasons. Those reasons are that it was open to the primary judge to find that there is no ambiguity in claim 21. VMS contends that:

(a) the phrase “relates to” in integer 9 of claim 21 operates to make the integer broad enough to include data which is a determination of vehicle overstay, as well as data which may lead to the identification of instances of vehicle overstay. The consequence is that the relevant data may either relate to instances of overstay that are identified by the detection apparatus before the data is retrieved by the data collection apparatus or relate to instances of overstay that are subsequently identified by the data collection apparatus processing the data it retrieves from the detection apparatus;

(b) the processing unit “programmed to process said data” in integer 8 of claim 21 is in the data collection apparatus and could be used to process the data to determine overstay; and

(c) claim 21 does not explicitly state that one or the other of the data collection apparatus or detection apparatus determines overstay, and instead only indicates that the components together comprise the system for identifying overstay.

52 The principles of claim construction are not relevantly in dispute and are conveniently set out in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 90; (2005) 222 ALR 155 at [67] (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) as follows:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331 at [81]; and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corp Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485-486; the Court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the Court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd, at 485–486.

53 As point (iv) in the summary in Jupiters makes clear, the claims are to be read in the context of the specification as a whole. However, balanced against that is the requirement that the body of a specification not be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another subject matter. Put another way, the correct approach to construction is to read the claims in the context of the specification, not merely when ambiguity exists in the claim, although integers not present in the claims cannot thereby be added: Fresenius Medical Care Australia Pty Ltd v Gambro Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 220; (2005) 224 ALR 168 at [44], [94] (Wilcox, Branson and Bennett JJ).

54 The primary judge found that there was ambiguity in claim 21 by reference to integer 9. In particular, whether the data received by the data collection apparatus from the detection apparatus that fell short of a vehicle overstay determination is “data relat[ing] to identified instances of vehicle overstay”. His Honour said at [125]:

…Data falling short of a vehicle overstay determination such as vehicle presence data and a record of vehicle movement in the parking space, including the date and time of movement, is data relating to vehicle overstay, but is it data relating to “identified” incidences of vehicle overstay? In my opinion, there is an ambiguity in the phrase between data which includes the identified instances of vehicle overstay, that is, the determination of vehicle overstay and data which may lead to the identification of instances of vehicle overstay. In those circumstances, it is appropriate to consider the rest of the specification in order to resolve the ambiguity.

55 He then turned to the specification and concluded that where the passage at page 7 lines 21 – 23 referred to “decisions relating to vehicle overstay” made in the data collection apparatus, it meant that the data collection apparatus made “determinations of vehicle overstay” (at [141]). His Honour went on (at [144]) to conclude that the ambiguity in claim 21 should be resolved by holding that it includes a system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus “having regard to the passage on p 7 and, to a lesser extent, the other passages relied on by VMS…”, being the two other passages on page 3 of the specification identified above.

56 In our respectful view, the difficulty with this reasoning is that it does not pay due regard to the language of claim 21.

57 Overall, the system identified in integer 1 is “for identifying overstay of vehicles”, indicating that the elements of the claim when combined perform that function. That purpose is repeated in the context of integer 2, where the detection apparatuses are also said to be “for identifying overstay of vehicles in respective parking spaces”. As a matter of construction, that purpose may be fulfilled if the detection apparatus records and transmits information capable of being used to identify overstay, such as the time when a vehicle arrived, the space where it is located, and the duration of its stay. The detection apparatus would be no less “for identifying overstay of vehicles in respective parking spaces” if it did not take the final step of processing that information to determine an instance of overstay.

58 Integer 3 refers to the data collection apparatus for retrieving data from the detection apparatuses. There is no doubt that the entirety of the data relating to identified instances of vehicle overstay is received by the data collection apparatus from the detection apparatus, as the primary judge observed at [125]. The data collection apparatus is to have a radio transmitter to transmit wake-up signals to detection apparatuses (integer 4), a radio receiver for receiving data from woken-up detection apparatuses (integer 5), a memory unit for storing data and instructions to be performed by a processing unit (integer 6) and a processing unit coupled with each of the radio transmitter, radio receiver and memory unit (integer 7).

59 Importantly, the processing unit must be programmed to “process said data received via said radio receiver and to indicate incidences of vehicle overstay to an operator” (integer 8). The fact that the unit is programmed to process received data from the detection apparatuses and also programmed to indicate incidences of vehicle overstay to an operator gives rise to a question: Is it by reason of the processing performed by the processing unit that incidences of vehicle overstay are determined (and then indicated to an operator) or is the processing unit only indicating – by communicating – incidences of overstay that have already been determined by the detection apparatus?

60 That question is resolved by moving on to read integer 9, which provides that “said data relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay in a respective parking space” (emphasis added). That is, the data that the processing unit referred to in integer 8 is programmed to process, being the data received from woken-up ones of the plurality of detection apparatuses, is data that relates to identified instances of vehicle overstay. As a matter of language, we understand this to mean first, that the detection apparatus will have already “identified” instances of vehicle overstay at the point that the data arrives at the processing unit. Secondly, the phrase “relates to” indicates that the “said data” not only consists of identified instances of overstay, but data that relates to it, such as details of current status, the amount of time the parking space has remained in the present state and records of vehicle movements. This is apparent, as we note below, from the use of that phrase in the body of the specification at pages 6 – 7 and also from the ordinary meaning of “relates to”, as noted by the primary judge at [125].

61 Accordingly, in our view, claim 21 identifies that it is the detection apparatus that supplies data on identified instances of vehicle overstay to the data collection apparatus.

62 We do not consider that the language of claim 1 or claim 11 provides a separate basis for the construction for which SARB contends. Claim 1 concerns the first aspect of the invention, being a method performed only by a subterraneous detection apparatus. Claim 11 is for a detection apparatus. Both identify in terms in integers 1(4) and 11(4) that it is the subterraneous detection apparatus that is to determine vehicle overstay. Claim 21 does not have an equivalent, express, integer to that effect. Nor does either claim 1 or claim 11 have the complexity of claim 21 arising from the fact that not only a detection apparatus but also a data collection apparatus is identified. We respectfully agree with the primary judge that the use of the phrases “for identifying overstay of a vehicle” and “data relating to identified instances of overstay” in those claims does not necessarily mean that it is the detection apparatus alone that determines vehicle overstay for the system of claim 21. The role of the data collection apparatus is to be determined having regard to the interaction between particular integers of claim 21, not by making assumptions on the basis of the differently worded earlier claims. Accordingly, whilst it is correct that where the same word or phrase is used in a claim(s) consistency should be maintained, that is subject to the practical qualification noted by the Full Court in Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC [2015] FCAFC 179; (2015) 240 FCR 85 at [85] (Kenny, Nicholas and Beach JJ) that if there is a good reason to depart from such consistency, then it is appropriate to do so. In the present case, the differences in structure and language between claims 1 and 11 on the one hand, and claim 21 on the other, serve to distinguish the points from that case.

63 We do not consider that the passage on page 7 lines 21 – 23 of the specification assists VMS. That passage appears in the context of an explanation of the embodiment of the invention described by reference to Figure 2, which depicts the detection apparatus. In that embodiment, the description from page 6 line 23 – page 7 line 20 identifies features of the detection apparatus that enable it to detect vehicle overstay. Those features include determining and maintaining information as to the current status of the parking space in terms of vehicle presence, a record of the time and date of vehicle movements and identification of an overstay situation when a vehicle remains for a duration longer than a defined interval (page 6 line 30 – page 7 line 5). The passage on page 7 lines 21 – 23, relied upon by the primary judge, follows that description of the embodiment and provides:

Alternatively, decisions relating to vehicle overstay can be made by a data collection apparatus that collects data from the apparatus 200 via a radio communication link rather than by the apparatus 200.

64 We do not consider that this passage is of significant assistance in resolving the question of the construction of claim 21. It merely contemplates, as an alternative embodiment, that the data collection apparatus may make decisions concerning vehicle overstay. Such a passage may provide fair basis for a claim including such an alternative (about which we make no comment), but it cannot supplant the language of the claim for identifying the scope of the monopoly. Nor do the two passages on page 3 of the specification (which the primary judge relied upon to a lesser extent) assist, other than providing general context for the claim.

65 Accordingly, in our view the primary judge erred in his construction of claim 21. Claim 21 does not encompass a system where vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus. For the reasons given, we would allow this aspect of the appeal and dismiss the contention raised by VMS.

66 SARB submits that the primary judge erred in holding that omnibus claims 30, 31 and 32 of the first patent include a method, apparatus or system in which vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus. Claims 30 – 32 are, in essence, claims for a method, apparatus and system (respectively) for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space “substantially as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown in the accompanying drawings”. Given that claims 30 and 31 reflect the first and second aspects of the invention (as reflected in claims 1 and 11, noted above), VMS accepts that these claims do not disclose a method or apparatus in which the data collection apparatus determines vehicle overstay. Claim 32 reflects the third aspect of the invention – a system (as is embodied in claim 21). SARB notes that the primary judge accepted that if claim 21 was infringed then by the same process of reasoning claim 32 would be infringed, but not otherwise. Accordingly, it contends that if it succeeds in relation to claim 21 (as it has), then the same results for claim 32.

67 VMS supports the decision of the primary judge in relation to claim 32 and in its Notice of Contention argues that for additional reasons, unrelated to the language of claim 21, the decision of the primary judge should be upheld even if his decision in relation to claim 21 is overturned. In this regard VMS submits that claim 32 ought not be construed as being limited to a system in which overstay is determined by a detection apparatus in circumstances where none of the figures shows overstay necessarily being determined by the detection apparatus.

68 The parties agree that the Orders of the primary judge erroneously include declarations of infringement of claims 30 and 31 whereas the only finding of infringement in the primary judge’s reasons concerned claim 32, to which the arguments on appeal are confined.

4.2 The relevant reasoning of the primary judge

69 The primary judge set out the relevant principles applicable to omnibus claims, which are not in dispute. After citing a passage in Raleigh Cycle Co Ltd v H Miller & Co Ltd [1948] 1 All ER 308; (1948) 65 RPC 141 at 157, 159–160, his Honour said:

148 GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare (UK) Ltd [2016] FCAFC 90; (2016) 120 IPR 406 (GlaxoSmithKline) provides an example of the construction process in relation to an omnibus claim and the limits depending on the terms of the specification of the expression “substantially as herein described”. An issue in that case was the construction of an omnibus claim which related to a liquid dispensing apparatus, “substantially as described with reference to the drawings and/or examples” (claim 9) and whether an alternative syringe fell within the terms of the claim. The Full Court said that when an omnibus claim is in issue, greater emphasis is generally placed by the words of the claim on the body of the specification to provide the necessary definition of the invention as required by s 40(2)(b) of the Act. In GlaxoSmithKline, the consistory statement for the first aspect of the invention found expression in an earlier claim (claim 1) and given that the specification made it clear that the example is of the first aspect of the invention, then it followed that the invention defined in claim 9 cannot be wider in scope than the invention defined in claim 1. The Court said in that case that the use of the word “substantially” in claim 9 in the expression “substantially as described with reference to the drawings and/or examples” does not extend the definition of the invention to the “substantial idea” disclosed by the specification and shown in the drawings.

149 Blanco White TA, Patents for Inventions (5th ed, Stevens & Sons, London, 1983) at 2–113 states that claims which are framed by reference to words, such as described or substantially as described, are construed by reference to the exact wording of the claim and the remainder of the specification, but there are a number of rules which are normally applicable. Those rules include the following: (1) the word “substantially” means “in substance” and for the most part is without effect. It does not broaden a claim such that an essential feature of the invention is replaced by something else. This means that as the essential features of the invention are identified by reference to the specification, the word “substantially” “can only rarely broaden the claim beyond what the consistory clause and the main claims specify”; (2) where claims of this type follow after broad claims, they are taken as attempts to claim the features of the (or a) preferred embodiment; and (3) the position is different where claims of this type are used, not merely to wind up after the broad claims, but among the broad claims and, in such cases, it cannot be presumed that the invention is meant to confine the invention to the features of the preferred embodiment.

70 The primary judge at [150] and [151] summarised the argument advanced by VMS to the effect that the omnibus claims included a method, apparatus or system (respectively for claims 30, 31 and 32) in which vehicle overstay was determined by the data collection apparatus. VMS’s argument was focused on claim 32, in respect of which it submitted that it was clear from Figure 1 and step 150 (which depicts a method where the final step is “indicate overstay of vehicle in the parking space based on the retrieved data”) that at that point the data collection apparatus is determining vehicle overstay. From there, VMS submitted that one goes to Figure 2 and the reference within the associated description to the alternative location of decisions or determinations as to vehicle overstay, which is the data collection apparatus. It submitted that in Figure 1 there is no step in the method that refers to the detection apparatus determining vehicle overstay and the reference at step 140 to wirelessly retrieving “at least a portion of the data from the detection apparatus” indicates that something less than an overstay determination may be made by the detection apparatus, with the determination step taking place by the data collection apparatus.

71 The primary judge noted at [152] that the submission advanced by SARB that: (a) claim 30 reflects the first aspect of the invention, a method, as does claim 1 (where the detection apparatus expressly determines vehicle overstay) and Figure 1; (b) claim 31 concerns an apparatus which reflects the second aspect of the invention, as does claim 11 (where the detection apparatus expressly determines vehicle overstay) and Figure 2; and (c) claim 32 is a system claim which reflects the third aspect of the invention, as does claim 21 and Figures 5, 6 and 7. SARB submitted that with respect to Figure 2, the passage on page 7 lines 21 – 23 relied on by VMS does not describe an embodiment, method or system of the invention and that Figure 2 does not show the data collection apparatus nor does any drawing or diagram show an alternative system where vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus.

72 The primary judge found in relation to Figure 1 that the experts relevantly agreed that under the method identified there, either the detection apparatus or the data collection apparatus could determine vehicle overstay (at [143]). In relation to Figure 2, the primary judge found that the detailed description does not show the determination of vehicle overstay by a data collection apparatus as Figure 2 is a representation of the detection apparatus (at [116]). However, his Honour found that the phrase “decisions relating to vehicle overstay” in the passage at page 7 lines 21 – 23, when understood in the context of the passage referring to an alternative embodiment, should be read to mean “determinations of vehicle overstay” by the data collection apparatus (at [141]). This was influential in the primary judge’s decision in concluding that claim 21 also included a system where determinations of vehicle overstay are made by the data collection apparatus.

73 The primary judge concluded:

154 In light of the relevant principles and the evidence, I am unable to see how VMS can succeed on the omnibus claims as an alternative argument. If it is correct about the construction of claim 21, then it is also correct about the omnibus claims. If VMS is not correct about claim 21, then the arguments which defeat its submission with respect to claim 21 also defeat its submission with respect to the omnibus claims.

74 SARB submits that the primary judge should have construed claim 21 consistently with the other independent claims to require that the detection apparatus determine overstay.

75 VMS submits first that the primary judge was correct in his construction of claim 21 and equally correct in finding that claim 32 also encompasses an embodiment where either the detection apparatus or data collection apparatus can make an overstay determination.

76 VMS submits in the alternative that the construction of claim 32 is not tethered to the construction in claim 21. It submits that claim 32 must be construed according to its own terms and that claim 32 should not be construed as limited to a system in which overstay is determined by the detection apparatus in circumstances where none of the figures show which device determines overstay. Instead, Figures 1 – 9 leave open the overstay being determined by either the detection apparatus or the data collection apparatus. In Figure 1, which is a “flow diagram of a method for identifying overstay of a vehicle in a parking space”, the data collection apparatus indicates overstay based on retrieved data stored in the detection apparatus, as the primary judge found at [93]. The specification provides in relation to Figure 1 that “at least a portion of the data is retrieved from the detection apparatus at step 140. Overstay of a vehicle in the parking space is indicated based on the retrieved data at step 150” (page 4 lines 16 – 18). Both experts considered that, in relation to Figure 1, there was no requirement that the detection apparatus determine overstay and that determination by the data collection apparatus was not explicitly ruled out, which the primary judge acknowledged at [117] and [143]. In respect of Figure 2, VMS contended that the description in Figure 2 included, on page 7, references to the alternative embodiment and that none of Figures 3 – 9 provide any indication of where overstay is determined. Accordingly, VMS submits that a system comprising detection apparatuses and a data collection apparatus in which either the detection apparatus or data collection apparatus determines overstay is a system substantially described in the specification and shown in the figures.

77 The primary judge concluded that for the same reasons that VMS succeeded in its argument in relation to claim 21, VMS should succeed on its construction of claim 32. The passage at [154] warrants close attention. Its basis lies in the reasoning in GlaxoSmithKline Australia Pty Ltd v Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare (UK) Ltd [2016] FCAFC 90; (2016) 120 IPR 406 at [69] – [74] (Allsop CJ, Yates and Robertson JJ) which his Honour summarised at [148] and which provides:

69 The principles of claim construction—including the construction of omnibus claims such as claim 9—are not controversial and need not be repeated in these reasons. It is sufficient to note for present purposes that, when an omnibus claim is in issue, greater attention is generally placed by the words of the claim on the body of the specification to provide the necessary definition of the invention as required by s 40(2)(b) of the Act. Typically of omnibus claims, claim 9 in the present case draws attention to “the drawings and/or examples”. These are to be found in that part of the specification that appears under the heading “Brief Description of the Drawings” to which we have referred at [15]-[22] above.

70 It is convenient at this point to note the following matters with respect to that description.

71 First, as the prefatory statement at p 13, lines 25-29 of the specification makes clear, the example and accompanying drawings are given to “better understand the various aspects of the invention”. As we have already noted (see [11] and [13] above), the invention is said to have two aspects—a particular apparatus (the first aspect) and a method using that apparatus (the second aspect).

72 Secondly, the drawings (represented by Figures 1 to 6) are of the one, preferred embodiment. This is made clear by the description of the drawings at p 13, line 31 to p 14, line 17 of the specification: see [15] above. Thus, only one example is given.

73 Thirdly, as the description of the drawings makes clear, the example given is that of the first aspect of the invention. This focuses attention on the description of the invention given by the consistory statement, which is to be found at p 3, line 30 to p 4, line 21 of the specification.

74 Thus, the example given does not represent, and should not be construed as, a departure from that which the specification has previously described as the first aspect of the invention. Properly understood, the example falls within the confines of that description.

(Emphasis added)

78 The short point is that the stream cannot rise above its source. As the italicised passage indicates, where there is a summary of the invention that articulates its scope, as the consistory clauses do in the present case, the description of embodiments of the invention as set out by reference to the drawings would not be construed to be broader than the summary.

79 The consequence, as the primary judge concludes, is that the construction of claim 21, which adopts equivalent language to the summary of the third aspect of the invention (at page 2 line 23 – page 3 line 2), is determinative of the dispute as to the scope of claim 32. If claim 21 is construed to include a system where vehicle overstay is only determined by the detection apparatus, then the embodiments of that invention would not be understood to identify an invention that was of a broader or different scope than the statement in the summary of the third aspect.

80 Unsurprisingly, VMS and SARB support this reasoning insofar as this Court on appeal agrees with their construction of claim 21.

81 In considering the breadth of an omnibus claim, such as claim 32, it is necessary to construe the whole of the specification. The language of claim 32 – “as herein described with reference to an embodiment shown” – compels that approach. Turning to the specification, after the three aspects of the invention are described, the drawings are introduced as being embodiments of the invention (page 3 line 23). The description of the drawings has been recited earlier in these reasons. Only in the description of Figure 2 is the device responsible for the determination of vehicle overstay identified, being the detection apparatus. The alternative embodiment on page 7 lines 21 – 23 refers to the data collection apparatus performing that task, but it is not shown in a drawing, as claim 32 requires. The rest of the figures are, as the primary judge found, either equivocal as to where vehicle overstay is determined or do not identify any apparatus. Moreover, the figures and descriptions that are identified as being for a “system” (being Figures 5, 6 and 7) are silent as to the part of the system that determines vehicle overstay.

82 The consequence is that the statement set out in the consistory clause representing the third aspect of the invention provides the basis for determining the broadest scope of claim 32. For the reasons given above, the third aspect, which is in equivalent language to claim 21, does not include within its scope a system where vehicle overstay is determined by the data collection apparatus. The outcome of this ground of appeal follows the outcome of the ground of appeal concerning the construction of claim 21.

83 In argument based on its Notice of Contention, VMS submits that there is no basis to understand that claim 32 is limited to a system in which overstay is determined by a detection apparatus in circumstances where none of the figures shows overstay necessarily being determined by the detection apparatus.

84 For the reasons given above, that approach tends to ignore the importance of considering the invention as a whole and as described in the specification, including the breadth of the summary of the invention. Once these matters are taken into consideration it is apparent that the argument based on the second paragraph in the Notice of Contention must fail.

85 Accordingly, we consider that this ground of the appeal is established. Ground 2 in the Notice of Contention must be dismissed.

86 SARB contends that the primary judge erred in holding that it had failed to establish that the patents fail to describe the best method known to VMS of performing the invention at the time of filing the applications.

5.2 The relevant reasoning of the primary judge

87 The primary judge addressed aspects of the evidence relating to this issue at [293] – [399], which evidence was also relevant to two other asserted invalidity issues.

88 It is necessary to set out this evidence in some detail as it received scant attention in SARB’s submissions on this appeal, and it is important because it underpins the primary judge’s findings.

89 The primary judge summarised SARB’s case with respect to the lack of best method ground at [293] as being “based on the failure to describe in the patents the [ASTRX2 transceiver] and an antenna”. Another aspect of SARB’s invalidity case was with respect to lack of entitlement based on the contribution of Mr Peter Crowhurst in relation to the antenna and his work in developing a functioning system.

90 In particular, the primary judge referred to evidence of Mr Fraser John Welch, the named inventor in both patents and executive director of VMS, whose evidence he accepted (at [296]). That evidence included the following facts, none of which are challenged on this appeal:

(1) Mr Welch identified the ASTRX2 transceiver in or about July or August 2003 (at [300]);

(2) on 19 December 2003, Mr Welch provided Mr Crowhurst with manufacturers’ information sheets about the ASTRX2 transceiver, which were described in the reasons as the Data Sheets (at [314]);

(3) Mr Crowhurst prepared schematics of the PCB (i.e. the printed circuit board) between December 2003 and January 2004 which included the ASTRX2 transceiver as a component (at [315] – [316]);

(4) further work was then performed which included further schematics being prepared (at [317] – [319]); and

(5) the provisional patent application relating to the period overstay detection system (POD System) was filed in May 2004 (at [320]).

91 Further evidence given by Mr Welch about the advantages of the ASTRX2 transceiver was summarised by the primary judge at [331] – [340] as follows:

(1) the ASTRX2 transceiver had the advantage that the receiver could turn itself on, rather than utilise an external device such as the microcontroller to turn the receiver on. That was because it had its own internal timer that was used to determine the wake-up period and those periods were predetermined. It did not require the external processor to do that and, as the external processor used more power, that meant that there is a power saving;

(2) one of the advantages of the ASTRX2 transceiver was that the period that it is awake and seeking to detect a signal is brief and that has the effect of saving power;

(3) in broad terms, two advantages of the ASTRX2 transceiver were that it did not stay awake for very long because it did not need to and it did not transmit data when it was unnecessary to do so;

(4) the ASTRX2 transceiver “ticked all the boxes as far as a transceiver component in the system was concerned”, and it was the lead candidate in the project as far as transceivers were concerned if it did what the manufacturer asserted; and

(5) the ASTRX2 transceiver was the best transceiver known to him and VMS for use in the communications component of the POD System.

92 The primary judge also referred to evidence given by Mr Crowhurst but decided not to place any significant weight on his evidence: see, generally, [347] and [361].

93 The primary judge then referred to the evidence of the independent experts.

94 The evidence of Mr Spirovski included the following:

378 Mr Spirovski was taken to the Data Sheets and taken through the Key Features and Product Description. …He agreed that the manufacturer was asserting in the Data Sheets that there is a meaningful saving in power in using the quick start oscillator in comparison with other devices.

379 …He agreed that because the ASTRX2 transceiver is able to wake itself up using its own internal timer, it does not require an external microcontroller or microprocessor to wake up the receiver and that this gives rise to a saving in power because the microcontroller consumes more power than the component in the receiver which is waking it up. He did say that a proper comparison could only be made if it is known what microprocessor is being used because, he observed, there are some extremely low power microprocessors. He said that one needed to look at the system as a whole to make such comparisons.

380 Mr Spirovski agreed that one of the attractive features of the ASTRX2 transceiver is that the transceiver could wake the receiver up to listen for incoming signals and it did not unnecessarily use extra power that would otherwise be required if the microcontroller woke the receiver up. He agreed that if the receiver can be woken up more quickly and it is able to turn itself off and wait for another predetermined signal, there is a saving in power consumption.

…

383 Mr Spirovski agreed that the designer of the system trying to match the output and input impedances of the transceiver with the impedance of the transmit and receive antennas must take account of manufacturing and temperature tolerances. There may be a variance between theoretical and actual impedances.

384 The trim function of the ASTRX2 transceiver which is designed to account for any variations due to manufacturing tolerances is an important feature of the device. It means that the designer can optimally match the circuitry of the transceiver with the antenna circuitry ...Mr Spirovski considered that the trim function was an advantageous feature, but not an absolutely necessary feature of transceiver chips…

…

386 Mr Spirovski was taken to the Micrel data sheet for the MICRF501 device (the Micrel transceiver). This is the device referred to by way of example in the specification of both patents. The Data Sheet is dated March 2003 and it describes a transceiver. Mr Spirovski agreed that the ASTRX2 transceiver had a much shorter start up time than the Micrel transceiver. He agreed that the Micrel transceiver relies on the microprocessor to wake up. He agreed that the Micrel transceiver does not operate its receiver in sniff mode and that it does not have an RSSI threshold which operates in the same way as the ASTRX2 transceiver. The ASTRX2 transceiver has a better start up oscillator. The Micrel transceiver does not have the trim function.

387 Mr Spirovski agreed that as a component, the ASTRX2 transceiver is a better transceiver in working the invention than the Micrel transceiver on the basis of power. However, Mr Spirovski considered that there are other considerations, such as cost, availability and lead times etc. Mr Spirovski considered that the trim function was a bonus and not absolutely necessary.

95 The evidence of Mr Harcourt included the following:

(1) in 2004, there would have been 20 to 30 options in terms of available transceivers (at [372]);

(2) there were a number of advantages of the ASTRX2 transceiver (at [385]);

(3) the ASTRX2 transceiver was the “better transceiver” (compared to the Micrel transceiver, which is the transceiver referred to in the specifications of the patents) (at [387] – [388]).

96 The primary judge referred to the wake-up scheme in the patents by reference to the evidence of Mr Spirovski as follows:

394 The First Patent contains a description of the flow diagram of a method of operating a DA (Fig 8), such as the apparatus shown in Fig 2. That description is set out above... There is a similar description of Fig 8 in the Second Patent (p 11 lines 10–132).

395 The wake-up scheme of the patents is disclosed in Figs 8 and 9 and the descriptions thereof. Mr Spirovski said, and I accept, that the scheme shown in Fig 8 may be performed in a number of ways. In the case of the use of a simple receiver, the steps 850, 860 and 870 may be performed by the processor, whereas in the case of an intelligent receiver (which may have an internal processor) those steps could be performed by the receiver. The term “wake-up” signal is not defined in the patents, save and except for a reference to what Mr Spirovski called the second aspect of a wake-up scheme, being the detection of an external apparatus for the purpose of communication. The reference is to a wake-up signal “(e.g., RF carrier followed by a defined message)” (First Patent p 9 lines 21–23). The first aspect of a wake-up scheme (according to Mr Spirovski) is a device which goes to sleep periodically. The ASTRX2 transceiver has the following features: (1) performs steps 810 to 860 shown in Fig 8; (2) can be programmed so that t2 (i.e., the wait period between turning on the receiver and the measurement of the RF signal strength (RSSI)) is consistent with the example value referred to in the patents; and (3) can be programmed so that t1 (the sniff interval) is consistent with the example value referred to in the patents.

396 In the context of questions about Fig 8, Mr Spirovski agreed that one implication of the wake-up signal is that there is a power-saving wake-up scheme which is part of the method, apparatus and system of the invention. He said that the second implication is that one is dealing with transient communications in the context of the First Patent. He agreed with the proposition that it is a very important feature of the invention in all its manifestations that power savings are achieved. He agreed that power saving is a critical consideration in the context of an in-ground unit that is powered by a battery.

5.2.2 The legal principles summarised

97 Section 40(2)(a) of the Act required that a complete specification must describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention. As found by the primary judge at [401], the obligation is to describe the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention as at the date of filing the application, which was 9 May 2005 (for the first patent) and 21 July 2011 (for the second patent).

98 At [403] – [412], the primary judge identified the relevant legal principles by reference to relevant authorities. No criticism is made by SARB of the legal principles identified by the primary judge, or any suggestion made that the primary judge did not apply those principles, and there was no debate in this appeal about what those principles were. We return to discuss the relevant authorities below.

99 The primary judge identified the particulars of SARB’s invalidity attack relating to best method (which is relevant to this appeal) at [402], including relevantly:

The specification does not include the best method known to VMS of communicating data from the subterraneous DA using a functioning wake-up scheme because they do not describe the ASTRX2.

100 After again identifying the case being advanced by SARB at [413], being referable to the non-disclosure of the ASTRX2 transceiver, the primary judge made a series of findings commencing at [414] and concluding at [436]. It is necessary to work through those findings to understand the conclusion, as one of the complaints by SARB in this appeal is that the primary judge did not address their contention relating to the ASTRX2 transceiver.

101 After referring to Figure 2 in the patents, the primary judge noted at [414] that: