Federal Court of Australia

Rakman International Pty Limited v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 202

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed in part.

2. Order 4 made by the primary judge in Proceeding NSD 1589 of 2018 (the Patent Proceeding) be set aside and, in lieu thereof:

(a) the applicants/cross-respondents pay the respondents’/cross-claimant’s costs of the Patent Proceeding (including the cross-claim) on a party/party basis subject to any order made pursuant to subpara (b) below;

(b) the Patent Proceeding be remitted to the Primary Judge for the purpose of determining whether the costs payable to the respondents/cross-claimant pursuant to subpara (a) above should be reduced on account of matters that were either abandoned or decided against them and, if so, by what proportion.

3. The appeal be otherwise dismissed.

4. The costs of the appeal and cross-appeal be paid as follows:

(a) the appellants pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal;

(b) the cross-appellant pay the cross-respondents’ costs of the cross-appeal and the notice of contention.

5. The time for any application to the High Court for special leave to appeal from these Orders is to commence on 5 February 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[1] | |

1.2 The grounds of appeal, cross-appeal and Notice of Contention | [6] |

[9] | |

[10] | |

[11] | |

[17] | |

[18] | |

[26] | |

[27] | |

[38] | |

[38] | |

[40] | |

[43] | |

[67] | |

[67] | |

[75] | |

[77] | |

5 INNOVATIVE STEP / NOVELTY: Ground 3 of the appeal and ground 2 of the Notice of Contention | [102] |

[102] | |

[106] | |

[119] | |

[119] | |

[124] | |

[125] | |

[146] | |

[181] |

THE COURT:

1 This appeal challenges findings of the primary judge as to the invalidity of claims 1 – 5 of innovation patent No 2017101778 entitled A Firestopping Device and Associated Method (Patent), findings that the appellants sent letters in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (ACL claim) and orders as to costs. Two decisions of the primary judge are relevant: Rakman International Pty Limited v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 464 (judgment) and Rakman International Pty Ltd v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCA 1113 (costs judgment).

2 The appellants, Rakman International Pty Ltd and Trafalgar Group Pty Ltd, are respectively the patentee and exclusive licensee of the patent. The respondents are Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd and its sole director, Mark Prior.

3 In the judgment, the primary judge determined:

(1) A patent case (NSD 1589 of 2018) concerning a claim for the infringement, and a cross-claim contending for invalidity, of the Patent which has a priority date of 12 February 2016 (patent proceeding). The primary judge found that although the appellants had established infringement of the five claims of the Patent, the cross-claim for the invalidity of the patent should succeed on the basis that claims 1, 2, 3 and 4 are invalid on the ground that they are not novel and that claim 5 is invalid for want of innovative step. The consequence was that the infringement case failed. In relation to the cross-claim, his Honour also found that letters sent by Trafalgar (all in substantially the same form and referred to collectively as the Trafalgar Letter) contained representations that were misleading or deceptive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL but rejected a contention that the patentee had made unjustifiable threats in breach of s 128(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth).

(2) An appeal by Boss from a decision of the delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks dismissing its opposition to the registration of Trade Mark Application No 1736748 (748 application) filed by Trafalgar for the word FIREBOX (first trade mark appeal) (NSD 641 of 2019). The primary judge found that the appeal should be allowed and that the 798 application should be refused.

(3) An appeal by Trafalgar from a decision of the delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks upholding an opposition by Boss to the registration of Trade Mark Application No 1812214 (214 application) filed by Trafalgar for a composite mark including the word FYREBOX (second trade mark appeal) (NSD 1242 of 2019). The primary judge found that the appeal should be dismissed.

4 In the costs judgment, the primary judge found that the appellants should pay indemnity costs following their rejection of offers that had been made in the patent proceeding and also in each of the first and second trade mark appeals.

5 It was necessary for the appellants to seek leave to appeal because in the course of the management of the case the issues of liability for patent infringement were separated from those concerning quantum. Separation of quantum and liability is a familiar and convenient course in many intellectual property cases and it is generally appropriate for leave to be granted in such circumstances; Airco Fasteners Pty Ltd v Illinois Tool Works Inc [2023] FCAFC 7; (2023) 170 IPR 225 at [2]. Leave was granted at the outset of the hearing.

1.2 The grounds of appeal, cross-appeal and Notice of Contention

6 The appellants rely on the following grounds of appeal (particulars omitted):

(1) That the primary judge erred in finding at [486] that the Trafalgar Letter issued by Trafalgar to Boss’ customers in September 2018 was misleading and deceptive in breach of s 18 ACL.

(2) That the primary judge erred in finding at [495] that Boss had lost the opportunity to supply the “BOSS FyreBox Multi Service Cable & Pipe Transit” (Fyrebox device) to potential customers and had suffered loss and damage.

(3) That the primary judge erred in finding at [339] that claim 5 of the patent did not involve an innovative step.

7 Grounds 4 – 7 concern the question of costs, which are addressed separately in Section 6 below.

8 The first respondent, Boss, contends:

(1) in its cross-appeal, that the primary judge erred in finding at [499] that the Trafalgar Letter did not contain a threat that engaged s 128(1) of the Patents Act; and

(2) in its Notice of Contention, that the orders for the revocation of the patent should be affirmed on the ground that claim 5 is not novel and also on the ground that if the claims of the patent had been valid, Boss would not have infringed any of them.

9 In determining an appeal from a decision involving an evaluative process such as the appeal from the judgment in the patent proceeding, an appellate court should be careful to distinguish between findings of error and disagreements in evaluation. As noted by Perram J in Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 (Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreeing):

[49] ... [The court] must be guided not by whether it disagrees with the finding (which would be decisive were a question of law involved) but by whether it detects error in the finding. On the one hand, error may appear syllogistically where it is apparent that the conclusion which has been reached has involved some false step; for example, where some relevant matter has been overlooked or some extraneous consideration taken into account which ought not to have been. But error, on the other hand, may also appear without any such explicitly erroneous reasoning. The result may be such as simply to bespeak error. Allsop J said in such cases an error may be manifest where the appellate court has a sufficiently clear difference of opinion: Branir at 437-438 [29].

[50] There may seem an element of circularity in this, but the sufficiently clear difference of opinion bespeaks not merely that the appellate court has a different view to the trial judge but that the trial judge’s view is wrong even having regard to the advantages enjoyed by the trial judge and even given the subject matter: Branir at 435-436 [24].

See also Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 104; 247 FCR 570 (Nicholas, Murphy and Beach JJ) at [45] – [47]; Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235 (Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ) at [8].

10 In this section, we summarise the reasoning of the primary judge insofar as it concerns the issues before the Court on appeal.

11 The primary judge noted that the specification describes the invention as relating to the field of passive fire protection, with embodiments of the invention finding application in the construction of buildings such as residential apartment buildings and the like. His Honour noted that the claimed invention in essence is a method of constructing a barrier, typically a wall, and routing services such as electrical cables and water pipes through the wall deploying an element referred to in the specification as a “firestopping device” which is commonly referred to as a “transit” or “fire transit”. The firestopping device is fastened to an external object, typically a soffit, and the barrier is constructed around the firestopping device. His Honour observed that it was this feature that was said to distinguish the method of the invention from prior art methods.

12 The part of the patent entitled “Background Art” includes the following, which his Honour quoted:

In a typical prior art method for constructing a residential apartment building the walls are constructed prior to installation of the services such as electrical cables, water pipes, etc. In this prior art method, a hole is made in the wall for each of the services, which typically must be separated by a standard separation distance, such as 200 mm for example. This separation distance requires significantly larger overall areas for services, which severely limits the design options for construction. Additionally, the typical prior art method often requires ladders and the like to be set up and moved repeatedly. Each of the individual holes through which the services extend must then be separately sealed in a fire rated fashion, which can be time consuming and expensive.

13 The specification then has a heading “Summary of the Invention” which provides consistory statements for claims 1, 2 and 3. His Honour found it convenient to set out all of the claims, which we do below:

1. A method of constructing a barrier having at least one service routed there through, the method including the steps of:

providing a firestopping device including: a first portion formed from a metallic material or a thermally insulative material having formations for fastening of the first portion to an external object; and a second portion formed from a metallic material or a thermally insulative material being separable from the first portion and being mateable to the first portion such that the first and second portions, when mated together, define the firestopping device; wherein the firestopping device has a first opening at a first end, a second opening at a second end and an internal volume intermediate the first and second ends, the internal volume and each of the openings being sized such that at least one service may extend through the firestopping device, and wherein an intumescent material is housed within the internal volume, the intumescent material being responsive to heat so as to swell within the internal volume;

fastening the first portion to an external object at a position that straddles the proposed positioning of the barrier;

positioning at least one service such that it is adjacent to, or in alignment with, the first portion;

positioning the second portion around the at least one service;

mating the first and second portions to each other such that the at least one service extends through the firestopping device; and

constructing the barrier around the firestopping device.

2. A method according to claim 1 wherein the first and second portions of the firestopping device are mateable to each other by at least one mechanical fastener without the use of any tools.

3. A method according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the first portion of the firestopping device is a planar panel defining a pair of opposite sides each having a side wall extending therefrom.

4. A method according to any one of the preceding claims wherein the second portion of the firestopping device is U-shaped so as to define a base connected to a pair of opposed side walls.

5. A method according to any one of the preceding claims further including the step of marking a line on the external object so as to depict the proposed centre line of the barrier.

14 The specification provides 19 figures which are addressed in the section entitled “Detailed Description of Preferred Embodiments of the Invention”. His Honour described the embodiments by reference to the first, which was the most extensively described in the specification. It is of a firestopping device comprised of two separate portions which are mated. These portions are referred to as the first portion and the second portion. The separability of the two portions allows the firestopping device to be used in the method that is claimed.

15 The first portion is a planar panel with a pair of opposing side walls. It is provided with holes to facilitate the fastening of this portion to an external object. The specification explains:

… In typical implementations the object to which the first portion 2 is likely to be fastened is an overhead concrete slab, although other possibilities include wooden frame structures, walls, floors, service shafts, etc. Fasteners, in the form of bolts, screws, or the like, extend through the holes 3 so as to fasten into the concrete slab, thereby securing the first portion 2 in place.

16 His Honour went on:

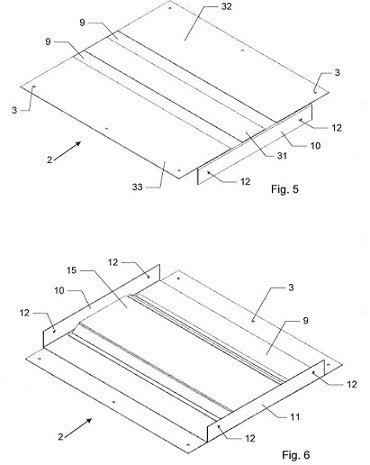

[43] The first portion is illustrated in Figures 5 and 6. Figure 5 is an upper perspective view, and Figure 6 is a lower perspective view, of the first portion:

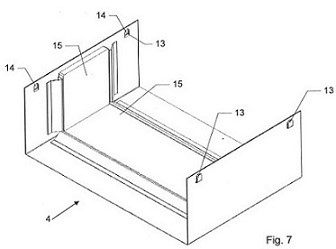

[44] The second portion is described as U-shaped, so as to define a base with a pair of opposing side walls. The second portion is illustrated in Figure 7, which is an upper perspective view of that portion:

[45] The specification describes features of the first portion and the second portion that provide means by which the two portions can be mated to provide the firestopping device. It is not necessary to dwell on these particular features. They do not feature prominently in the claims. Claim 2, for example, merely requires that the two portions are “mateable” to each other by at least one mechanical fastener, without the use of tools.

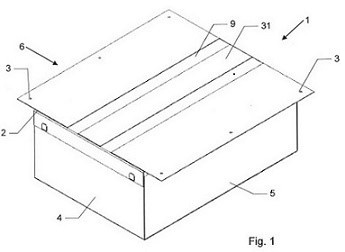

[46] The first embodiment of the firestopping device is illustrated by Figure 1, which is an upper perspective view of the device:

[47] The specification states that, in this particular embodiment, the second portion forms the base and “the majority” of the side walls of the firestopping device. This statement acknowledges that, in this particular embodiment, the side walls of the first portion also define, in part, the side walls of the device. Indeed, as I have noted, the first portion is described as a planar panel with a pair of opposing side walls. Figure 6 shows the opposing side walls by indices 10 and 11.

[48] The specification continues:

... in other embodiments the second portion mates with the first portion so as to form one of the sides and/or the top of the firestopping device.

[49] This statement discloses that, in other embodiments, the opposing side walls of the first portion provide the side walls of the firestopping device, with the second portion providing one wall of the device, including by acting as a “top” for the device.

[50] The specification continues by explaining that, in the described embodiment, the firestopping device has openings (shown by indices 5 and 6 in Figure 1) and an intermediate, internal volume through which at least one service (not illustrated) extends.

[51] The specification describes the placement of intumescent material within and outside the device to resist the passage of fire and smoke.

[52] The specification then describes a method of constructing a barrier:

Either of the above-described embodiments of the firestopping device 1 or 19 may be used in a method of construction of a barrier having at least one service routed there through. For the sake of providing an example, we shall assume that the barrier is a wall. The method commences with the marking of a line 27 on the concrete ceiling 28, which depicts the proposed centre line of the wall. The installer then fastens the first portion 2 to the ceiling 28 at a position that straddles the proposed positioning of the wall. More specifically, the first portion 2 is bolted onto the ceiling such that its intumescent material 15 is centred over, and extends parallel to, the centre line of the proposed wall, as shown in figure 13. Hence the positioning of the first portion 2 on the ceiling 28 provides a visual guide as to where the services are to penetrate through the proposed wall.

Next the installer positions the services (not illustrated) such that they are adjacent to, or in alignment with, the first portion 2. More specifically, the services are typically suspended by fastening devices such as clips, clamps, etc., approximately 50 mm below the ceiling so as to extend below the first portion 2 and generally perpendicular to the intumescent material 15 of the first portion 2. Typically, the installer will be supported by a lifting mechanism, such as a scissor lift or the like, whilst running the services. This process doesn't require the threading of the services through a prior art style of firestopping device, which helps ease of running the services and minimises the potential for the services to be damaged by the firestopping device. It is also time efficient and therefore has the potential to yield cost savings for the construction of the building. It also has the potential to assist project managers to coordinate the activities of various tradesmen and sub-contractors.

The reduction in required space for the firestopping of these services allows for significantly more flexibility in design, and the application of a multi-service firestopping device provides an "all-in-one" solution, allowing easier certification and compliance procedures.

Once the services have been run, the second portion 4 is positioned around the services. That is, the side walls 7 and 8 of the second portion 4 are positioned on either side of the services, with the base 17 of the second portion 4 below the services. The second portion 4 is then slid upwards so as to mate the first and second portions 2 and 4 to each other as shown in figure 14. Hence, the services now extend through the firestopping device 1.

It is now possible to construct the wall 30, as illustrated in figure 15, around the firestopping device 1 using standard barrier building techniques. For example, the wall installer may now attach wall engaging formations, in the form of a head track, to the ceiling 28 and to the exterior of the second portion 4, to which a barrier material, such as plaster board for example, may be attached. Additionally, or alternatively, wooden frame work may be constructed, to which a barrier material, such as plaster board for example, may be attached. Alternatively, formwork may be positioned to allow the pouring of a concrete wall. These processes may be assisted with the use of the second embodiment of the firestopping device 19, as illustrated in figures 16 to 19, to which the wall engaging formations in the form of channels 20 are pre-installed.

The resulting wall 30 has the firestopping device 1, and the services (not illustrated), extending there through. A number of services may extend together through the firestopping device without requiring the approx. 200 mm separation between each of them that is applicable to some prior art techniques.

[53] The specification describes the application of sealant around the inner perimeters of the first and second openings, and the placement of graphite impregnated foam and, optionally, thermally insulative wrap around the services, externally to the device.

(Emphasis added.)

17 After addressing the construction of various contentious words in the claims, the primary judge addressed the legal principles relevant to the disputed issues of patent validity, none of which are disputed on appeal.

18 His Honour then addressed the lack of novelty arguments, noting that the novelty challenge relied on disclosures made at two meetings, considered separately, which he defined as the Speedpanel meeting and the Seltor meeting ([126]). These meetings concerned the promotion of devices described as the Pass-It Version 1, Pass-It Version 2 and Pass-It with butterfly screws. Only the Seltor meeting is relevant to the appeal.

19 His Honour explained that Seltor Gruppen AS is one of the oldest construction firms in Norway and that Mr Ramunddal is its chief executive officer ([173]). It had purchased mastic and mortar products, used to stop fire passing through penetrations for pipes and cables in fire resistant walls, from Boss since about 2008 to about 2015. The Seltor meeting took place in September 2015 between Mr Ramunddal, Mr Alex Knutson – who was from a subsidiary company of Seltor – and Mr Prior, who is the director and company secretary of Boss.

20 At the meeting, Mr Prior gave Mr Ramunddal and Mr Knutson two samples of the Pass-It, which he called the “Fyrebox” ([177]). The primary judge records his findings as follows:

[178] Mr Prior says that, at the Seltor meeting, he described the function and features of the “Fyrebox” and how it could be installed during the construction of a building. The substance of his evidence is that he disclosed the following matters:

(a) The “Fyrebox” is installed after the position of the walls is marked out.

(b) The “Fyrebox” is installed in a position that straddles the wall.

(c) The wall can be built after the “box goes up”. The pipes and cables can be installed at any time, so that “scheduling issues” are solved.

(d) The intumescent material is in white plastic sleeves inside the “Fyrebox”.

(e) To install the “Fyrebox”, it is first pulled apart and the top part is mounted to the slab with masonry fixings.

(f) The other part of the box then slides into the top part and is attached to the top part using the screws provided or a wing nut (which can be provided).

(g) The services can then be run through the “Fyrebox” or the wall can be built.

(h) If the services are run through the “Fyrebox” before the wall is built, it is possible to remove the lower part to “fit the services through” and then reattach it. It is also possible to install the services after the lower part is attached.

(i) Fire resistant brushes are provided at each end of the “Fyrebox”. These will be fire resistant for the first 10 minutes of the fire, after which the intumescent material will have activated. The brushes will be burnt away.

[179] Mr Ramunddal’s evidence is consistent with Mr Prior’s evidence. Mr Ramunddal said that, at the meeting, Mr Prior described the following features of the “Fire Box”:

(a) It replaced traditional mortars and mastics to stop fire passing through penetrations for pipes and cables in fire resistant walls.

(b) It had a two-part steel case.

(c) The steel case had “four wings of steel” on the upper part, in which four holes were provided to allow that part to be attached to an upper concrete “deck”.

(d) The lower part could be connected to the upper part by either “normal” screws or wing screws.

(e) Brushes are provided to stop dust and other particles getting into the device.

(f) Sachets, containing “expanding fire resistant material” were attached to the inside of the steel frame. This material would expand and close the whole box in the event of a fire.

(g) The “Fire Box” was installed before the rest of the wall is put in place by removing the lower part and fixing the upper part to the concrete deck using the four wings of steel.

(h) The lower part could be attached to the upper part before the pipes and cables are installed or it can be attached after the pipes and cables are installed.

(i) If the lower part is attached to the upper part before the pipes and cables are installed, it is necessary for the plumbers and electricians to pull the pipes and cables through the brushes.

(j) If the lower part is attached to the upper part after the pipes and cables are installed, it is necessary for the plumbers and electricians to line up the pipes and cables with the pre-installed upper part.

(k) Once the lower part is attached to the upper part, the rest of the wall can be built around the completed “Fire Box”.

21 Photographs that Mr Ramunddal took of the Fire Box samples were tendered in evidence, which, his Honour explained, shows two samples of the Pass-It Version 2 that were provided at the meeting with what appeared to be a copy of the Firestopit product data sheet (PDS) which depicts the Pass-It product ([141]). The samples were tendered, as was the Firestopit PDS ([181], [182]).

22 At trial, the appellants advanced what the primary judge described as a wide-ranging attack on the veracity of the evidence of Mr Prior and Mr Ramunddal, which his Honour considered in detail and rejected at [184] – [219], concluding at [220] that he was satisfied that the Seltor meeting took place substantially as described by Mr Prior and Mr Ramunddal, that Mr Prior brought two samples of Pass-It Version 2 to the meeting and also a copy of the Firestopit PDS. None of these findings are challenged on appeal.

23 The primary judge was satisfied that at the Seltor meeting, Mr Prior disclosed all the features of the method of claim 1 with reference to the Pass-It Version 2 and all of the additional features in claims 2 and 4 ([223]).

24 In relation to claim 3, the primary judge accepted that the additional integer, where the first portion of the firestopping device is a planar panel defining a pair of opposite sides each having a side wall extending therefrom, was disclosed. In this regard, his Honour read the expression “side wall” to encompass the structure and geometry of short flanges, which he considered was clear from the disclosure of the specification; at [231]. That finding is also not challenged on appeal.

25 In relation to claim 5, his Honour said:

[233] Boss submitted that, at the Seltor meeting, the additional feature of the method claimed in claim 5 was disclosed—the step of marking a line on the external object so as to depict the proposed centre line of the barrier. Boss relied on the opinions expressed by Mr Page and Mr Hunter on this matter in Joint Report Part B.

[234] Trafalgar’s written closing submissions did not address this claim specifically. However, Trafalgar did dispute that Mr Prior gave detailed instructions about the use of the Pass-It Version 2, as Mr Prior and Mr Ramunddal had described. In this context, Trafalgar raised the unlikelihood that Mr Prior gave any instruction about the marking of a centre line.

[235] I do not accept that the additional step of claim 5 was disclosed at the Seltor meeting—at least with the sufficient clarity to amount to an anticipation. Importantly, Mr Ramunddal’s recollection does not include any statement being made that reflects this step. The highest that Mr Prior’s evidence rises in this regard is that he disclosed that, after the walls are “marked out”, the device is installed in a position that would straddle the wall. Even if I were to accept this evidence, it falls short of Mr Prior disclosing the step of marking the centre line of the “barrier”, and it is not a disclosure of marking such a line on the external object to which the firestopping device is to be attached.

26 In relation to lack of innovative step, the primary judge’s reasoning insofar as concerns claim 5 is as follows:

[332] Boss’s challenge to validity based on a lack of innovative step, as advanced in its closing submissions, focussed on the publication of the Firestopit PDS and claims 1 and 5 of the patent. However, its case on lack of innovative step was not confined to the disclosures of the Firestopit PDS or those claims. Boss also placed reliance on the prior art information on which it relied in its case on lack of novelty, and on other claims. It contended that if, contrary to its case on invalidity based on lack of novelty, the prior art information on which it relied did not disclose the essential features of the claims, then the invention, so far as claimed, only varied only in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention.

[333] Boss’s written submissions continued:

For example, the specific geometry attributed to each portion in claims 3 and 4 makes no substantial contribution to the working of the invention. All that matters is that there is a first portion fixed to the external object and a second portion position around the services. A comparison between Pass-It Version 1 and Pass-It Version 2 demonstrates the point. If the Court finds that claim 3 or 4 is not anticipated because the claimed geometry is not disclosed, those claims would lack an innovative step.

[334] This is as far as Boss’s case on lack of innovative step was developed with reference to the prior art information relied on for lack of novelty.

…

[337] The Court should not be left in this position. It is the task of the party relying on a lack of innovative step to identify each and every variance between the prior art information and the invention as claimed, and to articulate, by reference to the evidence, why that variance does not make a substantial contribution to the working of the invention as claimed. This is the task imposed by s 7(4) of the Patents Act.

[338] That said, the outcome of Boss’s challenge to the validity of the patent, based on a lack of innovative step, can be found, most directly, in my findings in relation to the disclosures made at the Seltor meeting. I have found that all the features of the method claimed in claims 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the patent were disclosed at that meeting. It follows that, with respect to the prior art information constituted by the disclosures at the Seltor meeting, only the additional, but undisclosed, step in claim 5—the step of marking a line on the external object to depict the proposed centre line of the barrier (integer 5.2)—now stands to be assessed as to whether that variance does or does not make a substantial contribution to the working of the invention.

[339] It should be appreciated at the outset that there is no requirement in the claims that the firestopping device be centred. Claim 1 merely requires the step of positioning the first portion of the firestopping device so that it straddles the proposed positioning of the barrier. “Straddling” the proposed positioning of the barrier is not the same as centring the device on a particular line. “Straddling” may or may not involve centring the device. Claim 5 itself does not require the step of centring the device. It simply stipulates the step of marking the centre line of the boundary on the external object to which the first portion of the firestopping device is to be fastened. I am satisfied that this step does not make a substantial contribution to the working of the invention. It is, truly, a trivial addition to the method that is otherwise described and claimed. But even if claim 5 were to be construed as requiring the step of centring the device on the centre line that is marked, that step would also be a trivial addition to the method that is described and claimed. Therefore, although the invention claimed in claim 5 is novel, it does not involve an innovative step based on the disclosures made at the Seltor meeting and is, accordingly, invalid on that ground.

2.3 Unjustifiable threats and contravention of s 18 ACL

27 The primary judge considered the issues of the unjustifiable threats and contravention of s 18 of the ACL under the same heading, given that both claims stemmed from the sending of the Trafalgar Letter.

28 At [473], the primary judge observed that in September 2018, Trafalgar sent letters to participants in the building industry informing them of its claimed patent rights. As the letters were substantially in the same form, the primary judge set out in full the terms of one letter, sent on 7 September 2018 to John Groom at Hutchinson Builders, as a representative example. Mr Groom was the person at Hutchinson Builders who was responsible for fire compliance matters:

Dear John

Notice of patent rights- Innovation Patent No. 2017101778

You may be aware that Trafalgar committed substantial investment in developing its innovative FIREBOX range of passive fire protection products.

Given the innovative nature of these products, Trafalgar applied for patent protection, and has had granted and certified a patent for the method of constructing a fire barrier using a product with the features of the FYREBOX Slab-Mounted product.

Trafalgar became aware of the supply of product by BOSS Fire & Safety Pty Ltd, which BOSS calls the BOSS FyreBox Multi Service Cable & Pipe Transit. It is our firm belief that when the BOSS product is used to construct a fire barrier during building that use of the BOSS product will be use of the method protected by the claims of Trafalgar's patent.

Therefore supply of the BOSS product is a supply which infringes our patent rights.

Also, the use of the method of construction protected by the Trafalgar patent (eg by installation of the Boss product on Hutchinson Builders sites) will also infringe our patent rights.

Trafalgar sought to address these concerns with BOSS last month, but to no avail.

On 30 August, Trafalgar issued Federal Court proceedings against BOSS, alleging that BOSS has and will continue to infringe the patent by supply of the BOSS product.

We are seeking an injunction restraining further supply of the BOSS product, as well as compensation for the past supply of the product.

This letter is intended to provide you with information regarding the Trafalgar patent and we stress that Trafalgar is not intending to assert its patent rights against your use of the method protected by the Trafalgar patent. Rather we are addressing the infringement at the point of supply of infringing products by our Court action against BOSS.

If you would like any further information on this matter, please feel free to contact me.

29 The trial judge noted at [474] that the letter was on Trafalgar letterhead and signed by Mr Rakic as Managing Director of the Trafalgar Group.

30 At [478], the primary judge noted that there were a number of things to be said about the Trafalgar Letters. It is useful to set his Honour’s comments out in full.

[479] First, the letter contains a statement, expressed as a firm belief, that, when the Fyrebox device is used to construct a fire barrier, then that use of the device will be the use of the method claimed in the patent.

[480] This statement is a headline statement. It is, to say the least, misleading. It is simply not the case that each and every use of the Fyrebox device to construct a fire barrier is a use of the patent method. The Fyrebox device can be used to construct a fire barrier in numerous ways that do not take the steps of the claimed method. If it were necessary to decide the point, I do not accept that Trafalgar was ignorant of that fact at the time it sent the letter. The fact that the statement is unqualified is important. No reference is made in the letter to, for example, using the device in a particular way, such as in accordance with the Fyrebox installation instructions. It is a generalised, unqualified, and incorrect assertion as to the extent of Trafalgar’s patent rights. The statement is no less misleading because it is couched in terms of Trafalgar’s “firm belief”. Indeed, the expression of that “firmness” would only have served to reinforce, in the mind of a recipient, the correctness of the assertion being made.

[481] Secondly, the headline statement is followed by the statement:

Therefore, supply of the BOSS product is a supply which infringes our patent rights.

[482] This statement is expressed as an unqualified conclusion, and would be understood as such. It is based on the headline statement. It is equally misleading. To start with, the conclusion does not follow from the premise, for the reasons I have given. Further, and importantly, the findings I have made above on the validity of the claims of the patent mean that the unqualified statement of infringement that Trafalgar made in its letter is false because, as events have transpired, Trafalgar does not, and did not, have the rights it asserted.

[483] I do not accept that Trafalgar’s use of “alleging” in the Trafalgar letter would have been taken as conveying that the lawfulness of Boss’s conduct was, realistically, contestable and that Trafalgar’s claims against Boss existed only in the realm of mere allegation, as Trafalgar’s closing submissions seem to suggest. Trafalgar also took the trouble to state that its patent had been “granted and certified”. In all likelihood, the reference to the patent having been “certified” would have conveyed to the recipients that there could be no doubt about the legitimacy of Trafalgar’s assertion of patent rights.

[484] Thirdly, the Trafalgar letter makes this statement:

Also, the use of the method of construction protected by the Trafalgar patent (eg by installation of the Boss product on Hutchinson Builders sites) will also infringe our patent rights.

[485] This statement is directed, unequivocally, to the use of the Fyrebox device in accordance with the method of the patent. As events have transpired, this statement is also false, given my findings on the validity of the claims of the patent. But, importantly, it is, according to its own terms, a separate, additional, and different statement to the headline statement. It serves to highlight that, in making the headline statement, Trafalgar was asserting rights of a breadth it never had.

31 At [486], the primary judge found that Boss had established that, by sending the Trafalgar Letter – which was undoubtedly sent in the course of trade or commerce – Trafalgar had engaged in conduct that contravened s 18(1) of the ACL.

32 At [487], the primary judge observed that he was in no doubt that Trafalgar sent the letter to warn off those whom it regarded as likely purchasers, or influencers of purchasers, of the Fyrebox device so that those persons would not purchase, or recommend the purchase of, the product or have any dealings with Boss in respect of that product. The primary judge continued:

The letter states that Trafalgar was seeking relief to restrain further supply of the Fyrebox device. This was a clear and intended signal to likely purchasers and other recipients that any dealings with Boss in respect of the Fyrebox device would be in jeopardy and at a real risk of interruption by the action that Trafalgar was taking against Boss. It was also a clear signal that such dealings would likely be viewed unfavourably by Trafalgar in future dealings by the recipients with it.

33 The primary judge considered that the Trafalgar Letter had its intended effect and had resulted in a loss to Boss. He observed that an example was provided by the events that followed the sending of the Trafalgar Letter to Hutchinson Builders. At [492], the primary judge set out Mr Groom’s response to receiving the Trafalgar Letter:

I’ve spoken to our legal team and we don’t want to get involved in any legal issues with you or Trafalgar. The letter says we could get sued if we use your box. We’d prefer to stay away from it, as it could have additional costs for Hutchinsons.

34 At [495], the primary judge stated that he was satisfied that, as a result of Trafalgar sending the Trafalgar Letter, Boss has lost the opportunity to supply the Fyrebox device to potential customers. He observed that “[i]nstantiations of that lost opportunity are provided by Boss’s dealings with Hutchinson Builders and USG Boral. Boss has thereby suffered loss and damage.”

35 The primary judge then turned to the issue of whether by sending the Trafalgar Letter, Trafalgar has made unjustified threats that would engage s 128(1) of the Patents Act, concluding, at [499], that he was not persuaded that it had.

36 His Honour observed that the question was to be considered objectively. So considered, he found that the Trafalgar Letter was sufficiently clear that Boss was the subject of Trafalgar’s complaint, not Boss’ customers. In reaching his conclusion, the primary judge acknowledged both that Mr Groom had interpreted the letter as a threat that Hutchinson might be sued, and that recipients of the letter might be warned off:

As I have said, the Trafalgar letter was a clear and intended signal to likely purchasers and others that any dealings by them with Boss in respect of the Fyrebox device would be in jeopardy and at real risk of interruption by the action that Trafalgar was taking against Boss. It was also a clear signal that such dealings would likely be viewed unfavourably by Trafalgar in future dealings with it.

37 Ultimately, the primary judge found at [500] that the Trafalgar Letter stopped short of threatening legal proceedings against the recipients themselves.

3. THE ACL CLAIM: Appeal grounds 1 and 2

38 In ground 1, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding that the Trafalgar Letter, issued by Trafalgar in materially the same form to a number of Boss customers, was misleading and deceptive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL. The particulars appended to this ground provide that the primary judge erred: in construing the letter; in finding that various statements were unqualified and misleading when they were couched in terms of Trafalgar’s “firm belief”; in failing to find that the letter conveyed a belief on reasonable grounds on the part of its author that the supply and use of the Fyrebox device infringed the patent; in finding that the letter conveyed the representation that “each and every” use of the Fyrebox device amounted to an infringement (at [480]); in finding that Trafalgar was not ignorant that, at the time the letter was sent, the Fyrebox could be used in numerous non-infringing ways; and in finding that at the time that the Trafalgar Letter was sent the unqualified statement of infringement in the letter was false, because the patent was found to be invalid (at [483]).

39 In ground 2, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred at [495] in finding that Boss had lost the opportunity to supply the Fyrebox device to potential customers and thereby suffered loss and damage.

40 In relation to ground 1, the appellants rely on the authorities concerning the distinction between expressions of fact and expressions of opinion, citing Inn Leisure Industries (Prov liq app) v D F McCloy Pty Ltd (No 1) (1991) 28 FCR 151 at 167 (French J); Cary v Freehills; [2013] FCA 954; (2013) 303 ALR 445 at [295] (Kenny J); Sealed Air Australia Pty Ltd v Aus-Lid Enterprises Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 29; (2020) 375 ALR 324 at [312]–[313] (Kenny J). See also TCT Group Pty Ltd v Polaris IP Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1493; (2022) 170 IPR 313 at [393] (Burley J); Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd v Ninox Television Ltd [2005] FCA 1404; (2005) 67 IPR 46 at [97]-[99] (Tamberlin J). They contend that legal letters, such as letters of demand, have been found to amount to expressions of opinion that are not found to be misleading if assertions are later found to be inaccurate and that the position in the present case is analogous, citing GM Global Technology Operations LLC v SSS Auto Parts Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 97; (2019) 139 IPR 199 at [592] (Burley J). The appellants also contend that the primary judge erred by relying on three sentences in the Trafalgar Letter to conclude that it contravened s 18(1) which diverted attention away from the letter as a whole and in context, including those parts of the letter that referred to assertions in terms of allegations presently before the Court, that Trafalgar had been unable to resolve its “concerns” with Boss, and that Trafalgar had no intention of taking any legal action against the recipient of the letter.

41 The respondents advance a number of reasons why ground 1 should fail. First, the case advanced on appeal based on the genuine belief of the author of the letter is not available on the pleading. As pleaded and at trial, the case advanced by the appellant in answer to the ACL claim was that the representations were true, because the patent was infringed. If it turned out that the patent was not valid, then the representation case would follow that result. It submits that if the point were permitted to be raised for the first time on appeal, Boss will suffer significant prejudice. Secondly, in any event, the court’s task is to examine what the impugned statements conveyed to their audience, citing Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; (2012) 247 CLR 486 at [33], [36], [38], [45] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Kiefel JJ). Even if the “own opinion” case was open, a misstatement in an opinion will not in every case be immune from a finding under s 18 of the ACL if the content of the letter as a whole is misleading or deceptive. In the present case, factual statements were made that would not qualify as opinion, objectively viewed. Thirdly, considered as a whole, the findings of the primary judge correctly characterised the representations. Fourthly, in any event, Trafalgar knew that there was no adequate factual basis for the representation that the use of the Fyrebox in constructing a fire barrier would infringe the patent and there were no reasonable grounds for Trafalgar to contend that all uses of the Fyrebox device infringed the patent. The primary judge’s findings support that conclusion.

42 In relation to ground 2, the appellants submit that the evidence before the Court summarised by the primary judge at [488] – [494] was insufficient to establish the finding at [495] that, as a result of Trafalgar sending the letter, Boss lost the opportunity to supply the Fyrebox device. The respondents defend the reasoning of the primary judge.

43 In relation to ground 1, it is first necessary to make some observations as to how the ACL case was advanced before the primary judge.

44 In its statement of cross-claim, Boss alleged at [14] that five representations were made in the Trafalgar Letter. The first, at [14.1], was that the supply of the Fyrebox device infringed the patent. Another, at [14.2], was that “any method of installation of the [FyreBox device] will infringe the 778 patent”. Another, at [14.4], was that the patent is valid.

45 At [15], the cross-claim relevantly said:

15 Each of the Trafalgar Representations is false, in that:

15.1 Supply of the [Fyrebox device] does not infringe the 778 patent;

15.2 Not all methods of installing the [Fyrebox device] infringe the 778 patent.

….

15.4 The 778 patent is invalid.

46 In its defence to the cross-claim, Trafalgar admitted in response to [14.2] that it made a representation “that the installation of the [FyreBox device] will infringe the 778 patent” and pleaded in response to [14.4] that “this alleged representation was correct at the time it was made as the 778 patent was then valid and subsisting”. In responding to [15] of the cross-claim, Trafalgar denied the allegations that the representations were false, pleading, in answer to [15.1] and [15.2] “…that the claims 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the 778 patent have been infringed by the cross-claimant” as set out in infringement case and, in response to [15.4] denying that the 778 patent is invalid.

47 It is apparent that, on its pleaded case, the appellants admitted that the Trafalgar Letter represented, as a matter of fact, the allegations made in [14.1], [14.2] and [14.4]. The appellants properly accepted as much in oral submissions. It is also apparent that the respondents prosecuted their ACL claim on the basis that the representations alleged were statements of fact. No application was made to withdraw the admissions made in the defence to cross-claim. Rule 16.03 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) requires that a party must plead a fact if failure to plead it may take another by surprise. It was not any part of the respondents’ case to negative a case of genuinely held belief or reasonable basis. Had it been part of the appellants’ case, then it ought to have pleaded it.

48 However, that is not the end of the matter. The appellants’ answer to the respondents’ challenge was that the respondents acquiesced in a departure from the appellants’ pleaded case and that it was therefore open to the primary judge to decide the case based on the arguments that they had put in closing submissions. In this regard, their written closing submissions at trial, at page 67 of 69 pages, made the point now made on appeal. It was encapsulated in [199]:

When read as a whole, including the above quoted statements, the letter would be understood to be a statement of firm belief on the part of Trafalgar that supply and use of the Boss Device infringes the Patent, and not a statement of fact. There can be no suggestion that the “firm belief” expressed in the letter is not genuinely held by its author and is not based on reasonable grounds. A truthful statement of opinion and belief as to legal assertions, expressed as it was by a non-lawyer and in circumstances where the letter makes plain that the allegations are presently before the Court, is not misleading and deceptive, even if the belief is ultimately determined by the Court to be incorrect. (see also by analogy GM Global Technology Operations LLC v SSS Auto Parts Pty Ltd (2019) 371 ALR 1 at [706]; Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd v Ninox Television Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 46 at [98]; Darmorgold Pty Ltd v Blindware Pty Ltd (2017) 354 ALR 1 at [399]-[400]).

(Emphasis in original. Footnotes omitted).

49 These submissions were handed up in court on the final day of the hearing, after the respondent’s closing oral submissions in chief had been delivered in relation to the ACL case. The oral submissions made on the subject were limited to the following:

We’ve teased it out a bit more from what we understood to be the assertions against us, but in the end, one can see in paragraph 198 we make reference to -emphasising in words there words such as “alleging”, “it is our firm belief” we say, in those circumstances the letter can’t constitute misleading or deceptive conduct.

50 The well-known statement of Issacs and Rich JJ in Gould v Mount Oxide Mines Ltd (In Liq) [1916] HCA 81; (1916) 22 CLR 490 at 517 (Griffith CJ, Isaacs and Rich JJ) provides the legal framework for consideration of this issue:

Undoubtedly, as a general rule of fair play, and one resting on the fundamental principle that no man ought to be put to loss without having a proper opportunity of meeting the case against him, pleadings should state with sufficient clearness the case of the party whose averments they are. That is their function. Their function is discharged when the case is presented with reasonable clearness. Any want of clearness can be cured by amendment or particulars. But pleadings are only a means to an end, and if the parties in fighting their legal battles choose to restrict, them, or to enlarge them, or to disregard them and meet each other on issues fairly fought out, it is impossible for either of them to hark back to the pleadings and treat them as governing the area of contest.

51 In Vale v Sutherland [2009] HCA 26; (2009) 237 CLR 638 at [41] (Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan, and Kiefel JJ), the High Court cited with approval the following statement by Dawson J in Banque Commerciale SA (in liq) v Akhil Holdings Ltd [1990] HCA 11; (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 296-297 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ):

But modern pleadings have never imposed so rigid a framework that if evidence which raises fresh issues is admitted without objection at trial, the case is to be decided upon a basis which does not embrace the real controversy between the parties … cases are determined on the evidence, not the pleadings.

See also Betfair Pty Ltd v Racing New South Wales and Another [2010] FCAFC 133; (2010) 189 FCR 356 at [51] (Keane CJ, Lander and Buchanan JJ).

52 We are not satisfied that the conduct of the case by the appellants falls within the category of cases that would permit them to depart from their pleadings. No notice was given during opening submissions that they intended to resile from their admission that the relevant representations made were representations of fact. No leave was sought to withdraw their admissions. In the circumstances we have described above, it was not sufficient to hand up in closing written submissions an argument that is contrary to the pleaded position and briefly refer to it in a single sentence, without drawing attention to the fact that it represents a change of position. Nor do we think, with respect, that the respondents should bear responsibility for reviewing their opponent’s written submissions after the conclusion of the hearing to check to see if there were any un-pleaded changes to the case advanced in them. One consequence of the “hand up when you stand up” approach to closing written submissions is that some obligation falls to the party speaking to those submissions to identify such issues and identify any material departures from the pleaded case. The respondents were entitled to notice of this change prior to the evidence so that they could have regard to it in cross-examining the author of the letter. As it happens, they were not afforded a fair opportunity to argue that the case was not open to the appellants.

53 Accordingly, we would dismiss ground 1 on that basis.

54 We would separately dismiss ground 1 on a further basis.

55 The relevant findings of the primary judge were as follows:

(1) That the Trafalgar Letter contains a statement of firm belief that when the Fyrebox device is used to construct a fire barrier, then that use of the device will be the use of the method claimed (at [479]).

(2) That is a misleading statement because it is not the case that every use of the device is a use of the patented method. The Fyrebox device can be used to construct a fire barrier in numerous ways that do not take the steps of the method. Trafalgar was aware of that fact at the time it sent the letter ([480]).

(3) The statement is misleading, notwithstanding that it is couched in terms of Trafalgar’s “firm belief”, the word “firmness” only serving to reinforce in the mind of the recipient the correctness of the assertion made ([480]).

(4) Moreover, the statement in the letter “[t]herefore, supply of the BOSS product is a supply which infringes our patent rights” is expressed as an unqualified conclusion, which would be understood as such. It does not follow the premise (of infringement in all circumstances of use). Furthermore, given the findings going to invalidity of the claims, the unqualified statement of infringement is also false because, Trafalgar did not have the rights it asserted ([482]).

(5) The same may be said of the allegations that the use of the method by the installation of the Fyrebox product on Hutchinson Builders sites which was made two sentences later and represented a separate statement by Trafalgar, asserting rights of a breadth it never had ([485]).

(6) The reference two sentences later to Trafalgar “alleging” infringement against the respondents by supplying the Fyrebox device does not change the position. It would not be taken to convey that the lawfulness of Boss’ conduct was merely contestable and subsisted in the realm of mere allegation. Having regard to the references to the patent being “granted and certified”, recipients would have understood that it was said that there could be no doubt as to the legitimacy of Trafalgar’s assertion of rights ([483]).

56 It is apparent from the foregoing that the primary judge had regard to the submissions advanced by the appellants and rejected them. In our respectful view, he cannot be criticised for doing so having regard to the manner in which the case was advanced. His Honour formed the view that the recipient of the Trafalgar Letter would not consider it to be an expression of contestable opinion, but an assertion of rights. Moreover, the characterisation of rights in the Trafalgar Letter was incorrect for two reasons. First, because the appellants’ claim overreached the scope of rights conferred by the patent insofar as it stated that any use of the Fyrebox would infringe when there were uses that would not infringe the method claims. Secondly, because in any event the patent was invalid and could not be infringed. Further, the primary judge rejected the proposition that any belief on the part of Trafalgar as to the first proposition was genuinely held, holding that Trafalgar was aware of the overreach.

57 We see no error in the primary judge’s reasoning in this respect. Accordingly, for that reason too, we would dismiss ground 1.

58 Ground 2 concerns the finding that Boss had suffered loss and damage. In this regard, the primary judge found that the Trafalgar Letter was sent to “warn off” likely purchasers, or influencers of purchasers of the Fyrebox device, so that they would not purchase, or recommend the purchase of the product or have any dealings with Boss in respect of that product (at [487]). That finding is not challenged on appeal. The primary judge concluded that the evidence available supported the view that the letter achieved its intended effect.

59 The primary judge provided an example by reference to the events following the sending of the letter to Hutchinson Builders ([488] – [493]): In early 2018, Boss promoted the Fyrebox device to Hutchinson, which expressed interest in using it in a large building project. Meetings took place with Hutchinson throughout 2018 and also with USG Boral, the supplier of a wall system to Hutchinson on this project. By August 2018, negotiations had reached an advanced state. Boss had worked with USG Boral to obtain fire testing of the device with USG Boral’s wall system. An initial approval report was issued on 21 August 2018 and USG Boral had expressed an interest in supplying the Fyrebox as part of its own branded product offering. However, in September 2018, after receipt of the Trafalgar Letter by Hutchinson and USG Boral, negotiations between Hutchinson, USG Boral and Boss came to an abrupt end. When the National Sales Manager of Boss, Mr Bacon, expressed to Mr Groom, the person at Hutchinson with responsibility for fire compliance matters, his hope that the Trafalgar Letter would not impact the project, his response was to say:

I’ve spoken to our legal team and we don’t want to get involved in any legal issues with you or Trafalgar. The letter says we could get sued if we use your box. We’d prefer to stay away from it, as it could have additional costs for Hutchinsons.

60 The primary judge records that Mr Groom expressed disappointment at that outcome because Hutchinson had spent $30,000 on re-design work to accommodate the Fyrebox device. Boss had also lost contact with USG Boral.

61 Against the background of these findings, the primary judge was satisfied that, as a result of Trafalgar sending the letter, Boss has lost the opportunity to supply the Fyrebox to potential customers.

62 The appellants criticise these findings on the basis that other evidence might suggest an absence of causal connection. They submit that the respondents did not lead any evidence from Boral or Hutchinson that they had ceased commercial discussions as a result of the Trafalgar Letter and refer to evidence of Mr Bacon who confirmed that between February and 21 August 2018 he had no communications with Hutchinson and note that there was no evidence that Boss had any communications with Boral after July 2018 in relation to the device. They also submit that there was evidence that throughout the dealings with Hutchinson, there were adverse fire test reports and “performance issues” with the device of concern to Hutchinson, and that Mr Bacon accepted that it was possible that Hutchinson was considering the use of other devices, which was not taken into account by the primary judge.

63 We do not consider that these criticisms reveal appealable error on the part of the primary judge. The question before him was whether the respondent had established that it had suffered, and continues to suffer, loss and damage as a result of the contravention of the ACL. As pleaded, the respondents contended that, for the purposes of satisfying the requirement of damage under s 18, its loss included the loss of opportunity to sell the Fyrebox device. The quantum of any loss is to be determined at a separate hearing. An enquiry as to damages is to be held at the next phase of hearing.

64 The obligation on the respondents at this stage is to demonstrate that some loss or damage was sustained by showing that the contravening conduct caused the loss of an opportunity which had some value, not being a negligible value, ascertained by reference to the degree of probabilities or possibilities; Sellars v Adelaide Petroleum NL [1994] HCA 4; (1994) 179 CLR 332 at 355 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ).

65 The primary judge was satisfied, particularly on the basis of the conversation with Mr Groom, that there was a sufficient causal nexus between the Trafalgar Letter and the cessation of negotiations to indicate that such loss could be found. The value of that loss need not be established to make out the cause of action. We do not accept that, by not referring the evidence advanced by the appellants to which attention has been drawn on appeal, the primary judge did not take that evidence into account. Nor do we accept that the conclusion drawn by the primary judge was not open to him on the evidence available.

66 Accordingly, ground 2 must be dismissed.

4. UNJUSTIFIED THREATS: Cross-appeal ground 1

67 Boss is critical of the primary judge’s reasons in finding, at [499], that the Trafalgar Letter did not make a threat that engaged s 128(1) of the Patents Act, in three respects. None of which were said to involve an error of principle.

68 First, by finding on the text of the Trafalgar Letter that there was no relevant threat made. Referring to the decisions in U & I Global Trading (Australia) Pty Ltd v Tasman-Warajay Pty Ltd [1995] FCA 794; (1995) 60 FCR 26 at 31, CQMS Pty Ltd v Bradken Resources Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 847; (2016) 120 IPR 44 at [170] and [186] and Liberation Developments Pty Ltd v Lomax Group Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1180; (2019) 144 IPR 413 at [147] – [149], Boss submits that a threat does not need to be express.

69 Boss submits that Trafalgar’s personalised allegation of infringement by customers: “the use of the method of construction protected by the Trafalgar patent (e.g. by installation of the Boss product on Hutchinson Builders sites) will also infringe our patent rights”, in the context of litigation against a supplier, would inevitably raise in the recipient’s mind, their own potential liability for their separate infringement.

70 The statement at the end of the Trafalgar Letter that “Trafalgar [was] not intending to assert its patent rights” against the recipient’s use, rather than a more certain “we will not assert our rights against you” would not dispel the impression in recipient’s minds that Trafalgar considers customers to be infringing its method. Boss submits that that impression is reinforced by the wording:

“Trafalgar is not intending to assert its patent rights against your use of the method protected by the Trafalgar patent. Rather we are addressing the infringement at the point of supply…”. (Boss’ emphasis)

71 Secondly, by giving insufficient weight to the evidence about how customers in fact interpreted the letter. In oral submissions, Boss drew attention to the fact that each Trafalgar Letter was personally addressed to its intended recipient, and, at least in the exemplar letter, mentioned the particular construction site relevant to that recipient.

72 Mr Rakic, the director and company secretary of Trafalgar, accepted in cross examination that in writing the letter his purpose was to discourage builders and sub-contractors from using the Fyrebox, and that he had hoped, in sending the letter to surveyors and certifiers, that they would consider informing builders that there might be a problem with the Fyrebox, and would discourage industry participants from using the product.

73 Boss submits that Mr Rakic’s familiarity with the fire protection industry and the participants in it enabled him to tailor the letter to its recipients and gave him a good understanding as to how those recipients would read and understand it. Mr Rakic conceded that he could see how a person might think that the reason the letter referred to the use of the Fyrebox on builders’ sites was to sow a seed of fear in builders that they might be dragged into legal trouble. That was relevant evidence as to formulating the reaction of the hypothetical recipient of the Trafalgar Letter. Whilst the primary judge made reference to the evidence of Mr Groom’s response to receiving the Trafalgar Letter: “the letter says we could get sued if we use your box”, Boss submits that the primary judge erred by giving that evidence insufficient weight.

74 Thirdly, by not applying the reasoning in CQMS in circumstances where the Trafalgar Letter was very similar to a communication in that case which was found by Dowsett J to be a threat.

75 Trafalgar emphasises the words of s 128 and submits that, considered objectively, the language of the Trafalgar Letter does not communicate any threat to commence proceedings of any kind against any person other than the manufacturer of the Boss Fyrebox. Quite the opposite. Trafalgar highlights the final part of the Trafalgar Letter which it submits could not have been clearer in stressing that Trafalgar had no intention of bringing infringement proceedings against the recipient of the letter:

This letter is intended to provide you with information regarding the Trafalgar patent and we stress that Trafalgar is not intending to assert its patent rights against your use of the method protected by the Trafalgar patent. Rather we are addressing the infringement at the point of supply of infringing products by our Court action against BOSS.

76 Trafalgar submits that the correspondence in CQMS is distinguishable from the Trafalgar Letter and observes that Dowsett J’s comments about the letter in CQMS have not been adopted in later decisions, including those of Damorgold Pty Ltd v Blindware Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1552; (2017) 354 ALR 1 and Liberation Developments.

77 Section 128(1) of the Patents Act provides:

128 Application for relief from unjustified threats

(1) Where a person, by means of circulars, advertisements or otherwise, threatens a person with infringement proceedings, or other similar proceedings, a person aggrieved may apply to a prescribed court, or to another court having jurisdiction to hear and determine the application, for:

(a) a declaration that the threats are unjustifiable; and

(b) an injunction against the continuance of the threats; and

(c) the recovery of any damages sustained by the applicant as a result of the threats.

78 Section 131 of the Patents Act provides:

131 Notification of patent not a threat

The mere notification of the existence of a patent, or an application for a patent, does not constitute a threat of proceedings for the purposes of section 128.

79 At [208] – [211] of her reasons for judgment in JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 1474; (2005) 67 IPR 68, Crennan J identified the following propositions arising from s 128:

(a) The threat must be made in Australia, in that it must be received in Australia and relate to an Australian patent or design: for an example in the context of a patent, see Townsend Controls Pty Ltd v Gilead (1989) 16 IPR 469 at 474.

(b) A threat arises where the language, by direct words or implication, conveys to a reasonable person in the position of the recipient that the author of the letter intends to bring infringement proceedings against the person said to be threatened: U & I Global at 31.

(c) A threat may arise without a direct reference to infringement proceedings: Lido Manufacturing Co Pty Ltd v Meyers & Leslie Pty Ltd (1964) 5 FLR 443 at 450-451.

(d) However, a communication merely notifying a person of the existence of a patent or a patent application, together with a statement that any suggestion that the recipient is entitled to replicate the invention is not maintainable, or a communication seeking confirmation that no improper or wrongful use or infringement of the patent has come to the recipient’s attention is not a threat: see s 131: Australian Steel Co (Operations) Pty Ltd v Steel Foundations Ltd [2003] FCA 374; (2003) 58 IPR 69 at [17].

(e) Once a threat has been established, it is prima facie unjustifiable unless the person making the threat establishes that it was justified. The court may grant the relief applied for unless the person threatening infringement proceedings establishes that the relevant conduct infringes or would infringe a valid claim of a patent: s 129.

(f) A threat can be made by means of a letter from a legal representative: Sydney Cellulose Pty Ltd v Ceil Comfort Home Insulation Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1350; (2001) 53 IPR 359 at 374.

80 Whether a communication amounts to a threat to commence infringement proceedings against the person said to be threatened for the purposes of s 128 is determined objectively. In U & I Global at 31, Cooper J accepted that the test is whether the language would convey to any reasonable person that the author of the letter intended to bring proceedings for infringement against the person said to be threatened and that it is not necessary that there be direct words that action would be taken. Cooper J relied upon the observations of McLelland CJ in equity, to that effect, in Lido Manufacturing at 450 – 451. We agree.

81 The conclusion of whether a document amounts to a threat of patent infringement proceedings is essentially one of fact; Occupational and Medical Innovations Limited v Retractable Technologies Inc [2007] FCA 1364; (2007) 73 IPR 312 at [9] citing Brain v Ingeldew Brown Bennison & Garrett (A Firm) (No. 1) [1996] FSR 341 at 349 where the Court of Appeal observed:

It is a jury-type decision to be decided against the appropriate matrix of fact. Thus a letter or a statement may on its face seem innocuous, but when placed in context it could be a threat of proceedings. The contrary is less likely but could happen.

82 Although each case is specific to its own factual matrix, both parties sought to highlight similarities and differences with the wording of the Trafalgar Letter to the letters considered in the authorities to which the primary judge had regard to advance their case.

83 In JMVB, three letters were sent by the patentee’s solicitors to dealers of the respondent’s campervans. Each of the letters contained paragraphs which essentially said:

If your client does not agree to the demands contained in the first two abovementioned paragraphs [which required the recipient of the letter to immediately cease distributing, offering for sale or selling the allegedly infringing campervan] within the time specified our client will commence proceedings against your client forthwith.

Should the latter information and declarations not be provided by [a particular date] our client reserves the right to commence legal proceedings against your client immediately after that date.

84 At [211] – [212] Crennan J was satisfied that the letters amounted to threats, noting that the conditional reservation of rights was a threat to sue for infringement on a future occasion. However, her Honour was not persuaded that the threats were unjustified in the circumstances as the only threats made were contained in solicitors’ letters sent prior to commencement of the action.

85 In Occupational and Medical Innovations, two letters sent by the US attorneys acting for the respondent to the applicant were claimed to constitute unjustified threats. Only the first was found to constitute an unjustified threat. The first set out in full in the reasons at [3] was a personally addressed and individually tailored letter, which stated that the sender “is prepared to take any legal action necessary to protect its patented and unpatented technology”. That letter made no attempt to identify any relevant patent but demonstrated that the recipient was in the same industry as the sender, with potentially competing products. The respondent led evidence which it said was relevant to the applicant’s understanding of the letter in the normal course of business, in particular that the applicant did not yet have a product on the market, which would make the applicant less likely to construe the letter a threat.

86 At [16] Dowsett J rejected the respondent’s attempt to narrow the operation of s 128 to cases in which there are already competing products in the market place. At [19] Dowsett J found:

The reference to the respondent’s patent rights clearly raises the possibility of infringement, suggesting that it holds a relevant patent. One would infer that the letter was dealing with conduct or potential conduct by the applicant, at least some of which would occur in Australia. A further available (and probable) inference is that if, as it implied, the respondent had a relevant patent, it was enforceable in Australia, and therefore probably an Australian patent.

87 Dowsett J observed at [20] that s 128 is, at least in part, designed to discourage allegations of infringement based on construction of a patent which is too wide, noting that over-generalization will often be an element of an unjustified threat. At [23] Dowsett J held the first letter to constitute an implied threat:

I am satisfied that a recipient in the position of the applicant would have understood the letter to threaten enforcement or similar proceedings in Australia, pursuant to an Australian patent held by the respondent, in connection with the import into Australia and/or other exploitation in Australia of retractable needles manufactured in China. I do not accept that the absence of any reference in the applicant’s letters to such threats detracts significantly from that construction.

88 The Trafalgar Letter contained overgeneralised assertions of infringement. The primary judge held that in making the headline statement, Trafalgar was asserting rights of a breadth it never had. Mr Rakman conceded that he knew when he sent the Trafalgar Letter that not all methods of installation of the Fyrebox Device would infringe the Patent.

89 In CQMS, which Boss identified as being the closest in circumstances to the present case, the respondents sought relief in respect of a series of letters said to constitute unjustified threats following Dowsett J’s finding there had been no patent infringement. The series of letters comprised the following (set out at [158]):

i. Letter from the [applicants’] patent attorneys, Fisher Adams Kelly, to the [respondents], dated 30 September 2013, which alleged the infringement of:

a. claims 1, 10 and 20 of the 400 Patent and “many claims dependent thereon”, which are not specified in the letter; and

b. claims 1, 3 and 5 of the 615 Patent and “many claims dependent thereon”, which are not specified in the letter.

ii. Letters from the [applicants’] legal representatives, Thomsons Lawyers, to the [respondents’] legal representatives, Jones Day, dated 18 and 23 October 2013.

iii. Emails from the [applicants] dated 6 or 7 November 2013 and 8 September 2014 to the [respondents’] customers and potential customers that the [respondents’] products infringe the 400 Patent and the 615 Patent.

90 Boss submitted that the Trafalgar Letter was similar to one in the series, the email to “customers” sent on 6 November 2013 (the CQMS email), which was found by Dowsett J at [170] to be a threat of future action against customers; persons who could be expected to purchase products from the applicants or the respondents. Boss highlighted the following passage from the email, which took the form of a general notice to customers, the terms of which were set out in CQMS at [168]:

CQMS Razer commences court proceedings against Braden for patent infringement

CQMS Razer Pty Ltd, and its related entity CQMS Pty Ltd (CQMS), have today filed patent infringement proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia against Bradken Resources Pty Limited and Bradken Limited (BKN).

CQMS is the owner of a number of patents relating to ground engaging tools (GET) and manufactures steel engineered wear parts for the mining industry, including GET.

BKN, also manufactures a variety of engineered steel products for the mining industry, has recently introduced a range of GET branded Penetrator Max into the mining sector.

CQMS believes some of these products infringe two of its patents.

After issuing a letter and attempting to resolve the dispute, CQMS commenced the proceedings against BKN alleging that:

Certain Penetrator Max products directly infringe CQMS’ registered patents. Specifically, the system that the relevant products use to affix the GET to mining machines, infringes the patents;

By selling certain components of the Penetrator Max products to its customers to be used as GET, BKN has infringed, and authorised the infringement of, the patents. However, CQMS’ dispute is with BKN not with the customers who use the GET.

CQMS has taken this action as a last resort as it believes it is necessary to protect its intellectual property rights.

The proceedings are scheduled for a first directions hearing in the Federal Court of Australia (Queensland Division) on 13 December 2013.

(Bold in original, italic emphasis added.)