Federal Court of Australia

Jusand Nominees Pty Ltd v Rattlejack Innovations Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 178

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | RATTLEJACK INNOVATIONS PTY LTD First Respondent PAN AUSTRALIS PTY LTD Second Respondent MURRAY ENGINEERING PTY LTD Third Respondent LEIGH SUTTON Fourth Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The Appellant pay the Respondents’ costs of the appeal as taxed, assessed or agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

Introduction

1 This appeal concerns a patent for an invention used in the mining industry. Although there were several patents in dispute at trial, by the time of the appeal the debate between the parties had narrowed to one patent, Australian Innovation Patent No. 2019100556 (‘556 Patent’), which is entitled ‘Safety System and Method for Protecting Against a Hazard of Drill Rod Failure in a Drilled Rock Bore’ (‘Safety System’). Further, the debate between them about that patent had narrowed to Claim 1 of that patent which is in these terms:

A safety system for protecting against a hazard of drill rod failure in a drilled rock bore above horizontal, and especially a hazard posed by a broken drill rod section within the bore, comprising:

an anchor member configured to be fixed in a proximal end region of the bore adjacent to a rock-face; and

an impact reduction member for reducing an impact of the broken drill rod section striking the anchor member in the proximal end region of the bore, wherein the impact reduction member is configured to be located in the proximal end region of the drilled bore and to extend within the bore above the anchor member to be impacted or struck directly by the broken drill rod section falling within the bore.

2 The relevant question before the trial judge was whether the First Respondent’s product, the SafetySpear, infringed Claim 1. The First Respondent cross-claimed contending that the patent was invalid and seeking its revocation. The trial judge concluded that the SafetySpear did not infringe Claim 1, that the patent was invalid and that it should be revoked. From the orders giving effect to those conclusions the Appellant now appeals. There are three sets of issues: first, the proper construction of Claim 1; secondly, whether the SafetySpear infringes Claim 1 properly construed; and thirdly, whether the patent is invalid. In relation to validity the issues are whether the specification of the patent discloses the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art (i.e. the requirement of s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (‘the Act’)) and whether Claim 1 is supported by matter disclosed in the specification (i.e. the requirement of s 40(3)). For the reasons which follow the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

The Construction Issues (Grounds 1-5)

3 Claim 1 of the 556 Patent is set out above. There are two debates between the parties about the proper construction of Claim 1. These are the meanings of the expressions ‘anchor member’ and ‘configured to be fixed in the proximal end region of the bore’. In relation to the first, the Appellant claims that the anchor member referred to in Claim 1 is capable of moving down the bore hole when struck by the broken drill rod section. The trial judge rejected this argument and concluded that the anchor member could only move by a de minimis amount on impact. As to the second, the Appellant submits that ‘configured to be fixed in the proximal end region of the bore’ meant that the Safety System is suitable to be installed at the end of the bore closest to the bore opening and can, therefore, be inserted some distance into the bore. The trial judge rejected this concluding that the expression required the Safety System to be installed flush with the rock face although it might be inserted some 10-15 cm up the bore to find purchase in solid rock not compromised by the blasting process used to excavate the corridor beneath the bore. I will deal with the issues in that order.

‘Anchor member’ (Grounds 1-3)

4 The primary judge held that an anchor member: (a) was required to stop the movement of the Safety System relative to the rock when impacted by a falling broken drill rod section; and (b) once struck should not move by more than a de minimis distance in the order of 1-5 mm.

General approach to interpretation

5 The experts agreed that the term ‘anchor’ did not have a technical or special meaning in the mining industry and the parties agree therefore that it bears its ordinary meaning. About its ordinary meaning they are, however, in dispute. The Appellant submits that the ordinary meaning of ‘anchor’ encompasses a denotation where an object can retard the movement of something else and, at the same time, can move (for example, a ship dragging its anchor). The Respondents submit that an anchor is necessarily fixed (for example, where a ship’s anchor drags, it is not really operating successfully as an anchor).

6 The parties adopt the same interpretative methodology used by the primary judge. They begin first with the ordinary meaning of the word ‘anchor’ as revealed by various dictionary definitions and then bring to account the various contextual implications which can be drawn from the terms of the 556 Patent. The disagreement between them lies, therefore, only in the application of that otherwise agreed methodology. On the question of application they differ both as to what can be gleaned from the dictionary definitions and as to what may be implied from the terms of the 556 Patent.

Dictionary definitions

7 Dealing first with the dictionary debate, the Appellant submits that an ordinary meaning of ‘anchor’ is a ‘device…for checking motion’ (citing the Macquarie Dictionary noun definition (2)) and that to ‘check’ means to ‘slow or bring to a stop’ (citing the Merriam-Webster Dictionary) or to ‘stop or slow the progress of’ (citing the Oxford Languages Dictionary). It followed that the meaning of anchor could encompass a thing which slowed the progress of another thing.

8 The Respondents submit that this does not assist the Appellant because the question is not whether the anchor member retards the downward motion of the falling drill rod section but rather whether, in doing so, the anchor member is itself permitted to move. There is some force in this submission. However, whilst not fully articulated by the Appellant, it is nevertheless implicit in its submission that where an anchor is used to slow or halt the progress of another thing, the anchor may itself move. If this were not its position, its case would make no sense since its argument is that the anchor member in Claim 1 is permitted to move down the bore hole after the Safety System is struck by the falling drill rod section.

9 The difference between the parties on the question of the denotation of ‘anchor’ therefore turns on this question: can something which moves whilst retarding the motion of something else ever be considered an anchor? The relevant primary non-specialist definitions of ‘anchor’ from the Macquarie Dictionary were set out at [106] of the trial judge’s reasons (‘J’) in these terms:

anchor

noun 1. a device for holding boats, vessels, floating bridges, etc., in place.

2. any similar device for holding fast or checking motion.

...

–verb (t) 11. to hold fast by an anchor.

12. to fix or fasten; affix firmly.

...

–verb (i) ...

16. to keep hold or be firmly fixed.

10 The Respondents submit that ‘the plain meaning of the definition as a whole’ entailed that whatever else an anchor might be it was not something which moved. In essence, this is a contention that something will not be operating successfully as an anchor if it moves whilst retarding the motion of something else; i.e. in the example of the ship dragging its anchor above, the anchor is not working as it should. I would accept that the anchor referred to in the noun definition in (1) is a device which is fixed and does not move. If an anchor is holding a boat in place, it is not moving. Correspondingly, I would accept that the similar devices referred to in the first part of the noun definition in (2) (devices ‘for holding fast’) are also fixed for the same reason.

11 However, I do not accept that the similar devices referred to in the second part of the noun definition in (2) (devices ‘for…checking motion’) are necessarily fixed. The reference to ‘checking motion’ cannot be a reference to ‘holding fast’ since otherwise it would be otiose. Thus, the checking motion referred to in noun definition (2) is a reference to the retardation of motion rather than its instantaneous cessation. In reaching that conclusion it is not necessary to resort to the definition of the word ‘check’.

12 Once that be accepted, I see no particular reason why the anchor must remain stationary when it retards the motion of something else. Where ‘anchor’ is used figuratively it seems reasonably clear that the contemplated retardation wrought by the figurative anchor may involve it moving to some extent. Thus in Australian English the phrase ‘to hit the anchors’ apparently means, inter alia, to apply the brakes: Rowe KP, Dictionary of Australian Analogies, Similes, & Idioms (2nd ed, Trafford, 2018). By this one does not mean that the car immediately stops. And if that be so it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the figurative anchor must, to some extent, be dragging someway behind. ‘To cast anchor’ is said to mean ‘to throw out the anchor in order to bring the vessel to a standstill’: Room A, Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase & Fable (16th ed, Cassell & Co, 1999). But until the vessel is brought to a standstill, it seems inevitable that the anchor drags even if not for very long. So too, it is within the legitimate realms of judicial notice to observe that in commercial litigation the expression ‘to throw out the anchors’ is sometimes used to connote a strategy of slowing down the progress of a matter towards a final hearing by the artful deployment of interlocutory disputation.

13 Whilst accepting that very often anchors, both actual and figurative, are fixed, I nevertheless do not accept that as a matter of ordinary English this is by any means inevitable, particularly where the anchor is used to retard rather than to tether or to fix. I would therefore reject the Respondents’ submission that the Appellant’s approach to the meaning of ‘anchor’ undermines ‘the plain meaning of the definition as a whole’. It is in any event doubtful that it is sound to attempt to determine from the meaning of a series of different dictionary definitions of the same word some core or essential meaning. It is certainly not possible in the case of contronyms such as ‘cleave’ (to split apart or to hold close) or ‘dust’ (to remove dust or to cover something in fine powder). Nor is it feasible in the case of less exotic words such as ‘hedge’ (a way of avoiding financial loss or a fence formed from shrubs) or ‘bar’ (a place of libation or a collective noun for advocates) although in that latter example some common thread may perhaps be perceived. In any event, as I have endeavoured to explain, as a matter of ordinary parlance a retardant anchor can move.

14 Thus the word ‘anchor’ is in fact capable of bearing the competing meanings for which the Appellant and the Respondents respectively contend. I would agree that the Respondents’ meaning is probably the more common but this is not sufficient to exclude the Appellant’s approach which, it seems to me, is nevertheless one which is extant.

15 Since ‘anchor’ may bear both meanings it becomes necessary then to determine which meaning it bears in Claim 1.

The implications about the meaning of the word ‘anchor’ which can be drawn from the terms of the 556 Patent

16 Both parties proceeded on the basis that it was legitimate to use the terms of the specification of the patent to resolve this ambiguity and the primary judge approached the matter in the same way. This is consistent with authority: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 (‘Décor’) at 400 per Sheppard J (‘…if an expression is…ambiguous, it is permissible to resort to the body of the specification to define or clarify the meaning of the words used in the claim’); Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly and Company [2005] FCAFC 224; 225 ALR 416 (French and Lindgren JJ citing Décor at [249] and, at [260], concluding that if a term were ambiguous ‘it would be permissible to look to those words in the body of the specification to resolve the ambiguity’); Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 at [44] (‘It is legitimate, however, to refer to the rest of the specification to…resolve ambiguities in the construction of the claims.’).

17 The primary judge analysed the terms of the specification and came to the conclusion that the anchor member referred to in Claim 1 could not move more than a de minimis amount of 1-5 mm. The Appellant takes issue with the following five textual considerations which led the primary judge to this conclusion:

(1) The specification contains no reference to the anchor member moving although it contains many references to the impact reduction member moving.

(2) At a number of points, the specification refers to the anchor member as being able to ‘readily withstand’ the impact loading caused by the falling drill bit which the primary judge did not think carried a connotation that the anchor member could substantially move.

(3) The Safety System in Figure 3 is shown to be working ‘flush with the rock face’. Her Honour reasoned that if this were so then, should the anchor member be permitted any substantial degree of movement, the Safety System might fall out of the bore hole which would be contrary to its stated purpose.

(4) At two places the specification referred to the anchor member being fixed in a manner similar to that known for a ‘“split-set” type of rock anchor’. The Appellant submitted that the primary judge concluded that this supported a construction of ‘anchor member’ which did not countenance substantial movement once struck by the falling drill bit.

(5) The trial judge construed the patent as requiring that a single device be suitable for every conceivable use of the Safety System.

18 I deal with these in turn below.

(a) The absence of references in the specification to the anchor member moving

19 The Appellant accepts that the anchor member depicted in Figures 2 and 3 does not move by more than a de minimis amount when struck by the falling drill rod section. However, it submits that this is not so in the case of the invention depicted in Figure 4. All of the references relied upon by the trial judge to conclude that the anchor member could not move by more than a de minimis amount were concerned with the invention depicted in Figures 2 and 3 and, so the argument went, her Honour had failed to attend to the fact that the anchor member in the invention in Figure 4 could, in fact, travel down the bore hole. That fact was said to teach powerfully that the anchor member could move by more than a de minimis amount.

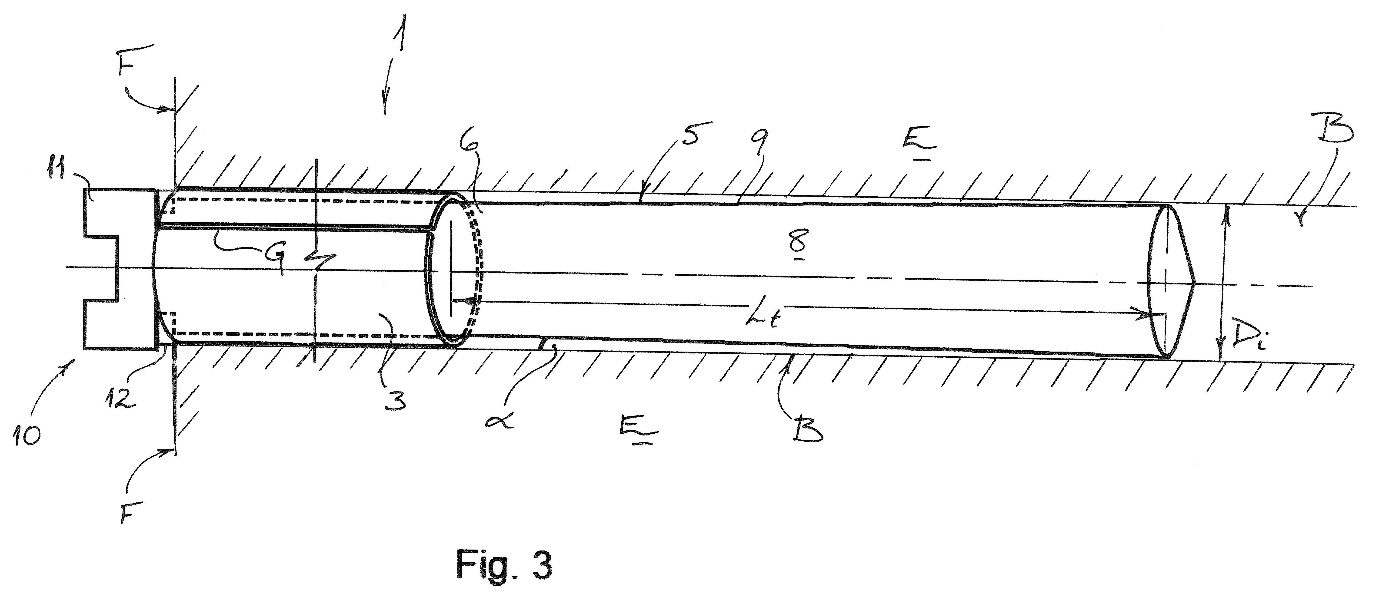

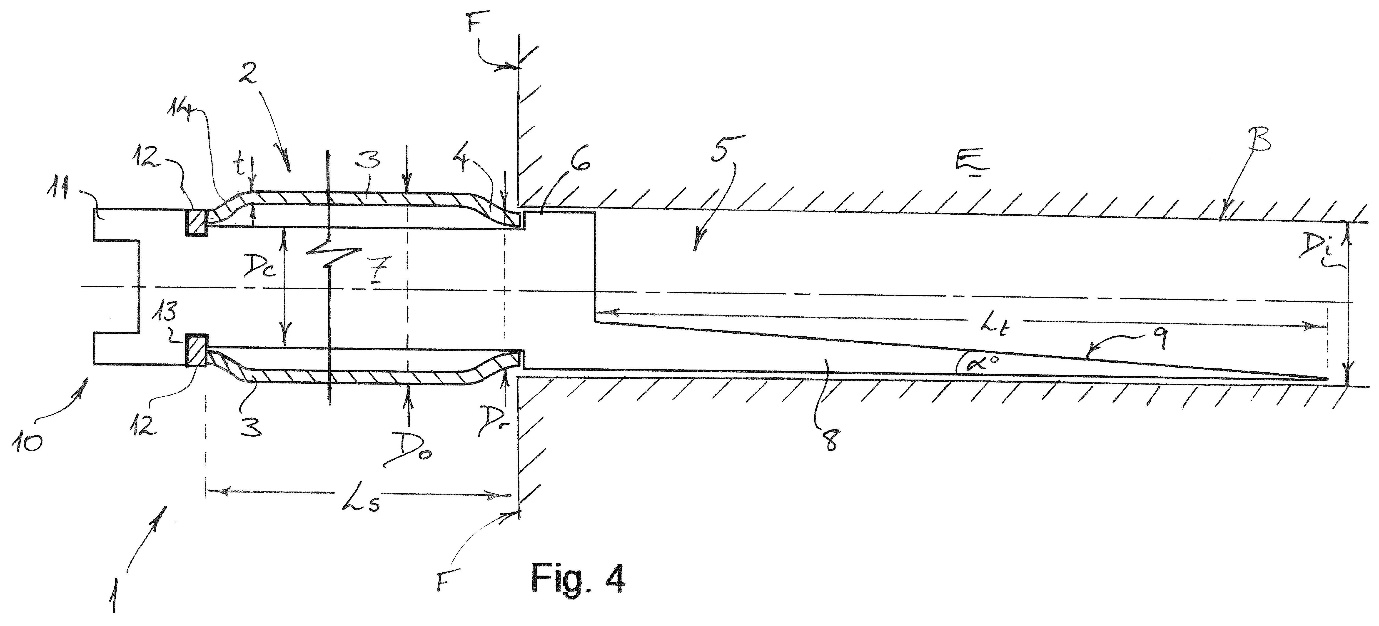

20 To grasp the Appellant’s point about this it is necessary to detour through the differences between the embodiment depicted in Figures 2 and 3 and the embodiment depicted in Figure 4. The first embodiment is depicted in two different positions, one with the anchor member located outside the bore but with the impact reduction member within the bore (Figure 2) and the other with the anchor member fully inserted into the bore hole (Figure 3). The second embodiment is depicted only with the impact reduction member fully inserted into the bore hole and the anchor member outside the bore (Figure 4). The notational references for all three figures are largely the same. Figures 2, 3 and 4 are as follows:

21 For present purposes it is to be noted that the detailed description of the embodiments in the specification explains that:

(a) the impact reduction member is numbered ‘5’;

(b) the anchor member is numbered ‘2’;

(c) the anchor member consists of a ‘split’ tube formed from a round steel tube or pipe which is numbered ‘3’;

(d) the split in the tube is a gap which extends longitudinally along the tube and is only illustrated at ‘G’ in Figure 3;

(e) the diameter of the split tube (‘Do’) is larger than the diameter of the bore hole (‘Di’);

(f) however, the diameter of the split tube at the front end of the anchor member (‘Dr’) is smaller than that of the bore hole (‘Di’) which permits it to be inserted into the bore hole;

(g) when the part of the split tube which is wider than the diameter of the bore hole reaches the bore hole it is able to contract as it is forced in (because of the presence of the gap or slit at ‘G’), thus enabling it to maintain a friction fit inside the bore;

(h) the difference between Figures 2 and 3 demonstrates how the predominantly wider split tube is forced into place in the narrower bore hole; and

(i) in each figure the impact reduction member has a taper of α° although it will be seen that the nature of what is tapered is quite different as between the two embodiments.

22 In the case of the embodiment in Figures 2 and 3, the central idea is that when the falling drill rod section hits the impact reduction member (in both figures travelling from the right) it drives the impact reduction member into the anchor member. The deeper into the anchor member the tapered impact reduction member travels the greater its girth becomes and the more outward pressure it exerts on the steel tube of the anchor member. This, at first, retards and, then, ultimately stops the movement of the impact reduction member.

23 It is not in dispute that on and shortly after impact, the anchor member in the embodiments depicted in Figures 2 and 3 would move by no more than a few millimetres. In these embodiments, there is significant movement of the impact reduction member relative to the anchor member so as to achieve a ‘gradual or extended transfer of impact loading’ to the anchor member: 556 Patent at p 10 line 27 to p 11 line 12.

24 By contrast, the embodiment in Figure 4 works in a different way. In this embodiment, it will be seen that the impact reduction member is different to the impact reduction member in the embodiment in Figures 2 and 3. Whilst both impact reduction members may be said to be tapered, their retardant action differs. In Figure 4, the retardant action of the tapered impact reduction member derives from its interaction with the falling drill rod section which is forced into contact with the bore wall the further down the tapered impact reduction member it travels. In this embodiment, the anchor and impact reduction members do not move relative to each other. In the embodiment in Figures 2 and 3, by contrast, the retardant action of the impact reduction member derives from its movement relative to, and consequent interaction with, the anchor member.

25 The debate between the parties about the Figure 4 embodiment is whether the anchor member in Claim 1 provides braking action by itself travelling down the bore hole. A proposition which sounds as though it answers this question but which does not is that the anchor member, in the event that it did travel down the bore, would provide braking action in the course of doing so. The debate between the parties concerns how the anchor member in Claim 1, properly construed, in fact operates. This deceptively similar proposition is, by contrast, a theoretical statement about what would happen if the anchor member in Claim 1 did in fact travel down the bore hole. It takes as its point of departure an assumption that the anchor member in Claim 1 does, in fact, travel down the bore and, hence, assumes the answer to the question under consideration. Here the important point is that proof that an anchor member driven down a bore hole provides braking action through frictional force is not proof that this is, in fact, what the anchor member in Claim 1, properly construed, is intended to do. A sofa tied to the back of a car will operate to retard its forward progress but this tells one nothing about the sofa’s intended purpose.

26 There was evidence of this theoretical kind that an anchor member, if driven down the bore hole, would provide frictional braking force. At trial the Appellant called Mr Davison, an expert in mining engineering, and he gave evidence to this effect at [109] of his affidavit (‘…it remains the case that any movement of the safety system will have the effect of absorbing the kinetic energy from the falling drill rod’). The Respondents called Dr Fuller, a geotechnical engineer who is also an expert in mining engineering. He accepted that if the anchor member in Claim 1 was not required to keep the Safety System in place when struck by a falling drill rod section, the effect of its movement down the bore hole would be to brake the motion of the falling drill rod section (I discuss this evidence in more detail below). However, neither Mr Davison’s nor Dr Fuller’s evidence to this effect is evidence that the anchor member in Claim 1 is intended to retard the motion of the falling drill bit by travelling down the bore hole.

27 On the actual question between the parties of whether the anchor member in Claim 1 could, when struck by the falling drill rod section, travel down the bore hole and thereby provide braking action, there was also evidence. The Appellant submits that this evidence showed that the anchor member in Claim 1 could travel down the bore hole once struck by a falling drill rod section and thereby contribute to slowing the falling drill bit by the generation of frictional force between the anchor member and the bore wall. For the following reasons, I do not accept that the evidence established this proposition. It comprised two different portions of testimonial evidence.

28 The first portion consisted of evidence from Mr Davison at [42] of his affidavit that the anchor member performed ‘the role of locating and holding the safety system in position in the bore until such time as it may be struck by a falling drill rod section’. If accepted, this evidence left open the possibility that after the Safety System was struck by a falling drill rod section the anchor member ceased to hold the Safety System in place. If read that way, one might extract from it that from that point on (i.e. during the impact event) the anchor member might travel down the bore hole and thereby generate frictional force. It is not entirely clear to me that Mr Davison really did go so far as to say this but, in any event, it is not necessary to determine whether he did so because Mr Davison himself abandoned any such contention.

29 This he did in the Joint Expert Report at p 2 where he indicated for the purposes of clarity that he did not mean in [42] of his affidavit that the holding function of the anchor member was performed ‘only until such time as it may be struck by a falling drill rod section’; that is to say, the holding function of the anchor member continued after the Safety System was struck by the falling drill rod section. As such, Mr Davison’s evidence did not establish that the anchor member in Claim 1 slowed the falling drill rod section by travelling down the bore and generating frictional force.

30 The second portion of testimonial evidence relied upon by the Appellant came from Dr Fuller. Dr Fuller’s evidence was that the anchor member in Claim 1 did not travel down the bore hole. In his third affidavit at [8], Dr Fuller said, in response to Mr Davison’s statement at [42] to which I have just referred, that ‘To the contrary, the specifications of each of the Patents disclose to me that the purpose of the anchor member is to hold the safety system in place both before and during the impact from a falling drill rod section.’

31 However, Dr Fuller was cross-examined about this and the Appellant submits that in his cross-examination he conceded the anchor member in Claim 1 could retard the motion of the falling drill rod section by moving down the bore hole during the impact event.

32 The cross-examination took this course: first, the cross-examiner, Mr Smith, endeavoured to have Dr Fuller agree that a feasible mode of operation for the Figure 4 embodiment was one which involved the anchor member in a degree of ‘downhole movement’ which Dr Fuller rejected (‘No, I don’t agree’): T214.24-214.28.

33 Secondly, Mr Smith then embarked on a series of questions about the alleged infringing product, the SafetySpear. Here it is useful to know that the SafetySpear has three plastic rings which do indeed retard the movement of the falling drill bit by travelling down the bore. The nub of the debate between counsel and Dr Fuller concerned Mr Smith’s suggestion that since the SafetySpear had the same purpose as the Figure 4 embodiment it was logical that the anchor member in Figure 4 could also travel down the bore. Cutting out some unnecessary detail, Dr Fuller declined to go down this path with Mr Smith on the basis that it wrongly assumed that the three rings in the SafetySpear were anchor members within the meaning of Claim 1 which, in his view, they could not be since they moved when the anchor member in Claim 1 could not: T215.10-215.23.

34 Thirdly, Mr Smith then suggested that Dr Fuller was basing his understanding of the Figure 4 embodiment on his interpretation of the word ‘anchor’, a proposition with which Dr Fuller agreed at T215.31.

35 Fourthly, Mr Smith then sought to elicit what Dr Fuller’s understanding of the Figure 4 embodiment would be if the word ‘anchor’ were omitted from the 556 Patent. This elicited an objection from Mr Cordiner who appeared for the Respondents at trial. The debate occupies a page or so of the transcript. The primary judge expressed the view that Mr Smith’s question did not appear to be particularly relevant but permitted it anyway: T217.11-217.12. The question was then asked again. There was a further objection which, after some back and forth, was withdrawn and the final form of the question was put at T218.22-218.26 in these terms:

MR SMITH: And what I’m suggesting to you is, putting the word “anchor” to one side and just considering how that might work in practice, that a sensible mode of operation for [the Figure 4 embodiment] is that it might resist that falling drill rod by slowing it down to a stop, including by the lower section moving down through the bore with frictional resistance.

36 Before committing himself to answering this question Dr Fuller indicated a desire to know where the anchor member was located in the bore; in particular, whether it was flush with the rock face or whether it was further up the bore hole. His concern was that if it was installed at the rock face then any downward movement would reduce its ‘capacity’ (T218.33-218.35) by which it may be assumed he meant that the anchor member would, to some extent, no longer be in the bore and hence would have reduced frictional resistance (or, one imagines, if it went far enough, none apart from that afforded by the air through which it would then be falling). Mr Smith adjusted his question to overcome this point by inviting Dr Fuller to assume that the anchor member was located two metres within the bore.

37 Dr Fuller then accepted that in this case the anchor member would act to slow down the falling drill rod section. Dr Fuller’s full answer was at T219.5-219.6 and included a caveat:

DR FULLER: Yes, it would slow it down. But whether it would slow it down sufficiently to stop it, I don’t know.

38 Thus Mr Smith was successful in winning from Dr Fuller the concession that if the patent did not contain the word ‘anchor’ and if the not-the-anchor member were inserted two metres into the bore, it was possible that the not-the-anchor member would slow down the falling drill rod section by travelling down the bore although whether it would slow the drill rod section sufficiently so as to stop it was not known. As I have observed above, this evidence demonstrated that if the anchor member did travel down the bore after it had been struck it would generate frictional force with the bore wall and retard the downward motion of the descending drill rod section. But, as I have also indicated above, that was not the question to which the case gave rise which was instead whether the anchor member in Claim 1 was intended to travel down the bore hole or remain fixed in place.

39 Thus, I do not accept that there was any evidence from Mr Davison or Dr Fuller on that question. Necessarily, I reject the Appellant’s allied contention that the trial judge had overlooked this non-existent evidence. The primary judge referred to this debate, such as it was, at J [113]-[114]:

113 Second, Jusand criticised Dr Fuller’s reasoning which it said was based on the particular embodiment shown in Figure 2. According to Jusand, Dr Fuller read down the disclosure in the Patents to fit with his assumed meaning of the word “anchor”. Jusand submitted that Dr Fuller read the Patents with an assumption that the patentee intended to exclude from the scope of its monopoly embodiments that Dr Fuller recognised in cross-examination would feasibly work so as to achieve the object of the Patents.

114 In cross-examination Dr Fuller agreed that down-hole movement of an anchor member would absorb energy. When Dr Fuller was asked to consider the embodiment shown in Figure 4, he understood that it did not rely on the same principle shown in the Figure 2 embodiment, and that it relied solely on its frictional engagement with the bore walls. It would therefore have a more constant capacity to resist downward movement.

40 It is true her Honour did not refer to the detail of the cross-examination set out above but the reasons show that her Honour was perfectly aware that the Appellant was putting a case on the Figure 4 embodiment. Whilst it is true that her Honour did not refer to the concession that Mr Smith had won from Dr Fuller this is because that concession did not relate to what the anchor member in Claim 1 meant but to the theoretical (and, as the Respondents correctly submitted, irrelevant) question of whether an anchor member driven down a bore hole generates frictional force with the bore wall and hence retards the falling drill rod section.

41 Another way of seeing why this is so is to observe that what Dr Fuller accepted, with a caveat, was that if the word ‘anchor’ did not appear in Claim 1 then he would accept that the anchor member in Figure 4 could operate to break the falling drill rod section by travelling down the bore hole. For this evidence to be of any use, it was necessary for the hypothesis on which the evidence rested to be made good. That hypothesis was that Claim 1 did not use the word ‘anchor’. That hypothesis could never have been made good. Whilst I well understand on pragmatic grounds why the primary judge permitted this line of questioning to proceed, there was never any possibility that it was relevant since there was never any possibility that Claim 1 did not have the word ‘anchor’ in it. Her Honour’s presentment that this evidence was probably not relevant at T217.11 was therefore correct.

42 Turning then to the principal complaint into which this debate feeds, the Appellant submits that the trial judge erred in referring to parts of the specification which were notable in their failure to refer to any movement of the anchor member and contrasting those with the frequent references to the movement of the impact reduction member. The Appellant argues that the parts of the specification referred to by the primary judge were all parts which concerned the embodiment in Figures 2 and 3.

43 However, as will shortly appear, the primary judge explicitly relied upon parts of the specification dealing with Figure 4 to reach the conclusion that the anchor member could not move. The analysis began at J [125] with the observation that ‘No movement of the anchor member relative to the rock-face or the bore is described in the context of the functioning of the embodiments in Figures 3 and 4.’ Her Honour then referred to a part of the specification which said:

In [the Figure 4] embodiment, however, the impact reduction member 5 is not configured for any significant movement relative to the plug member 2 upon impact by the falling broken drill rod section S. Rather, as the falling broken drill rod section S initially impacts or contacts the surface 9 of the tapered portion 8, the drill rod section S is gradually deflected towards and into contact with the opposite inner wall of the bore B. This contact generates friction which acts to brake the falling object and dissipate the impact. Again, therefore, the tapered portion 8 acts to cause gradual or extended transfer of impact loading from the drill rod section S to the anchor member 2. In particular, by extending the stopping distance for the falling drill rod section S (i.e. the distance travelled by the drill rod section S after initial impact) via the tapered portion 8, the impact force is again reduced significantly, such that the friction fit or interference fit of the anchor member 2 within the bore B can readily withstand the impact loading.

44 The trial judge referred to this passage at J [128] as part of her Honour’s discussion of why the anchor member could not move. What is striking about the final sentence is its reference to the ‘friction fit or interference fit’ of the anchor member in the Figure 4 configuration which her Honour explicitly mentioned at J [128]. Thus, the contention that the trial judge overlooked the Figure 4 embodiment in concluding that the anchor member did not move is not correct.

45 The highest one can put the Appellant’s case is its submission that the patent contains no express direction that the anchor member cannot move. However, as the trial judge was astute to observe, it just as equally lacks any suggestion that the anchor member should move: J [125]. And, in relation to the Figure 4 embodiment, the references to the ‘friction fit or interference fit’ of the anchor member are slim pickings indeed for a contention that the anchor member was intended to operate by travelling down the bore hole.

46 The next step in the argument was that her Honour had failed to bring to account the evidence that the embodiment in Figure 4 could travel down the bore. However, this was the evidence of Mr Davison and Dr Fuller to which I have referred and, as I have explained, was evidence of the theoretical retardant effect of the anchor member if driven down the bore hole rather than evidence that this was what the anchor member in Claim 1 was intended to do.

47 There is also the point made by the trial judge that the anchor member was to be ‘fixed’ when installed: J [145]. The Appellant’s riposte to this is that it does not entail that the anchor member must remain fixed once struck by the falling drill rod section. However, there was no evidence for this view. As I have explained above, Dr Fuller denied it and whilst Mr Davison had initially suggested that the anchor member’s fixation purpose ceased once the impact event began he retreated from this in the Joint Expert Report.

48 Next the Appellant submitted that the primary judge found at J [98] that the person skilled in the art would understand that the two components of the Safety System operate together to absorb the energy of the falling drill rod section. What her Honour said at J [98] was this:

In the context of the Patent, the person skilled in the art at the priority date would understand:

• The hazard posed by the falling broken drill rod is extreme and potentially fatal;

• The only way identified in the Patents to protect against the hazard is to stop the broken drill rod section from leaving the bore hole;

• The safety system of the Patents must stop the drill rod section falling from the bore each time;

• The impact force from a falling drill rod section, which is primarily a function of drill rod section size, weight, drop length and bore angle, is substantial, in the order of up to possibly hundreds of tonnes;

• A different safety system may be required for bores of different diameters;

• Stopping the falling drill rod section will involve absorbing the energy of and decelerating the falling drill rod section; and

• The one safety system will need to work for the all the potential forces up to the maximum possible impact force potentially experienced in a bore hole; i.e. whether the drill rod falls from a short distance or from the far end of the bore hole.

49 This is an overall description of how the Safety System works and does not descend into the detail of which component does what. In particular, it does not say that the anchor member is intended to generate frictional force by travelling down the bore. As such, it does not advance the Appellant’s submission.

50 Thus there is nothing in the Appellant’s submission that the person skilled in the art would understand that the anchor member described in the Figure 4 embodiment would decelerate a falling drill rod section as the anchor member moved downwardly against the frictional resistance of the bore wall. It follows that the Appellant is not correct to submit that the Figure 4 embodiment taught powerfully that the anchor member could travel down the bore. To the contrary, as the Respondents correctly submitted, this is precisely what it does not show.

(b) Significance of the words ‘readily withstand’

51 At p 10 line 27 to p 11 line 12 of the 556 Patent this passage appears:

In this embodiment, the impact reduction member 5 is configured for movement relative to the plug member 2 upon impact by the falling broken drill rod section S. That is, the body 6 of the impact reduction member 5 is configured for movement into an interior of the plug member 2 if impacted or struck by the drill rod section S. In this way, the outer surface 9 of the tapered portion 8 of the body 6 contacts and bears against an inner surface of the split tube 3. As an initial impact by the broken drill rod section S drives the elongate body 6 downwards into the split tube 3, the slight taper of the tapered portion 8 exerts an outward force on the split tube 3 and thus enhances or increases engagement between the bore B and the tube 3. The tapered portion 8 thereby acts to effect a gradual or extended transfer of impact loading from the broken drill rod section S to the plug member 2. In particular, by extending the stopping distance for the falling drill rod section S (i.e. the distance travelled by the drill rod section S after initial impact) via the tapered portion 8, the impact force is reduced significantly, such that the friction fit or interference fit of the anchor member or plug member 2 within the bore B can readily withstand the impact loading. In this way, the safety system 1 of this embodiment can effectively and reliably protect workers and/or equipment in the cavity C from the hazard of broken drill rod sections S falling from a bore B drilled above horizontal.

52 The equivalent passage in relation to the Figure 4 embodiment at p 12 line 29 to p 13 line 9 is set out above and contains a relevantly identical reference to the anchor member being able to ‘readily withstand the impact loading’ from the falling drill rod section.

53 The Appellant submits that the primary judge was wrong to conclude the phrase ‘readily withstand’ was inconsistent with the notion that the anchor member could move substantially down the bore hole. Rather, it submits that in the context of the Safety System it is clear that the phrase refers not to the anchor member absorbing the impact loading from the falling drill bit but to the fact that the Safety System provides protection from the hazard of drill rod sections falling from the bore.

54 The trial judge examined this issue at J [127]-[129]. Her Honour noted that in both embodiments the impact reduction member was said to reduce the impact force of the falling drill bit such that the friction fit or interference fit of the anchor member could thereby ‘readily withstand the impact loading’. At J [129] the trial judge observed that ‘withstanding does not connote substantial movement’.

55 This observation is, with respect, plainly correct. A building does not ‘withstand’ cyclonic winds by falling over once buffeted by them but, rather, by staying upright. So too, it is difficult to see how the anchor member can be said to ‘withstand’ the depredations of the falling drill rod section if its first reaction is to slide down the bore hole the moment it is struck. The Appellant’s answer to this was that ‘readily withstand’ referred not to the anchor member but was instead to be understood ‘in the context’ that the Safety System provided protection from the hazard of drill rod sections falling from the bore. The use here of the expression ‘in the context’ is a retreat into the dim language of vagueness. By its vagueness the submission impermissibly evades committing itself to the identity of the object which does the act of readily withstanding. When the vagueness is dispelled, the problem with the submission is that the sentences at p 11 line 9 and p 13 line 9 explicitly identify what readily withstands the impact. It is the friction fit or interference fit of the anchor member. I therefore reject the submission.

(c) The significance of whether the Safety System needed to work whilst flush with the rock face

56 Part of the trial judge’s reasons for concluding that the anchor member could not move more than a de minimis distance once struck concerned an observation her Honour made at J [131] that the invention depicted in Figure 3 needed to work whilst flush with the rock face (‘If there was any more than de minimis movement in that example, it is possible that the safety system would fall from the bore hole.’). That statement was made in the course of her Honour’s consideration of the meaning of ‘anchor member’. In another part of the reasons, her Honour dealt with the meaning of ‘a proximal end region of the bore adjacent to a rock-face’; the discussion of which began at J [151]. The Appellant relies on a passage in that discussion appearing at J [178] which, so it submits, shows that the trial judge was wrong to approach the construction of ‘anchor member’ on the basis that the Figure 3 embodiment had to be installed flush with the rock face. Why? Because when considering what was meant by ‘a proximal end region of the bore adjacent to a rock-face’ her Honour had accepted that the Safety System (and hence the anchor member) did not need to be installed flush with the rock face.

57 The passage the Appellant relies upon is at J [178]:

Figure 3 of the Patent shows the installation of an embodiment of the safety system with its base at the rock-face. I agree with Rattlejack that the safety system of the invention as illustrated in Figure 3 is installed “flush” with the rock-face. I also agree that the safety system of the invention must work in the installed position illustrated in Figure 3. However, the claims are not limited to the embodiments and the specification describes friable rock at the bore entry point and the need to insert the safety system into more competent rock. In that situation the base of the safety system will not be, and nor do the claims require it to be, flush or substantially flush with the rock-face.

58 The reference to ‘competent rock’ requires explanation. This the trial judge had provided at J [169]-[170]:

169 Dr Fuller’s evidence was that the first 10 to 15 cm of rock in the bore (ie the rock that constitutes the collar and the initial short length of the bore) can be damaged during the process of blasting to create the tunnel. The strength of that rock can be reduced, so in order to act as an anchor, Dr Fuller considered that the anchor member of this system would need to be at least partly in rock above the blast damage zone.

170 Mr Davison’s evidence was to similar effect: that the quality of the rock at the lowest end of the bore hole may be compromised and unstable because of the blasting to create the stope, the natural quality or stability of the rock and/or the stresses and strains at the rock-face. Furthermore, in the joint report Mr Davison agreed that there might be bad ground conditions at the “rock-face/mine opening interface”. I assume from his earlier evidence and the context of his comment in the joint report that Mr Davison’s reference to “mine” opening meant the opening of the bore hole at the rock-face. Mr Davison did not give an estimate of the length that the damaged rock might extend up the bore hole.

59 Thus the point was that the blasting process may make the first 10-15 cm of rock unreliable for anchoring purposes. As her Honour observed at J [172] the specification contemplated this situation at p 12 lines 3-6:

This may be particularly useful where the rock at the rock face F is friable or crumbing, because it enables the safety system 1 to be driven deeper into the bore B beyond the rock face F where it can be soundly founded in competent rock.

60 Returning then to J [178], contrary to the Appellant’s submission, her Honour did not accept that the embodiment in Figure 3 was to be installed other than flush with rock face. On the other hand, the trial judge accepted that the Safety System could be installed some way up the bore hole to avoid the problem of friable rock (noting that the embodiment in Figure 3 is a particular example of the Safety System). The immediate point of J [178] was to reject the Appellant’s contention that ‘a proximal end region of the bore adjacent to a rock-face’ merely identified in which half of the bore the Safety System was to be installed (the proximal as opposed to the distal end, as Mr Caine put it). But there is no doubt that J [178] proceeded on the basis that the anchor member was to be fixed because her Honour accepted the Respondents’ submission that ‘the safety system…must work in the installed position illustrated in Figure 3’.

61 Returning then to the suggested tension between J [131] and [178], I do not accept that there is any tension. The discussion at J [131] concerns the Figure 3 embodiment whereas the critical statement at J [178] upon which the Appellant now relies is about the meaning of the claims. Both paragraphs recognise that the Figure 3 embodiment works flush with the rock face but her Honour’s point at J [178] is that this is not a requirement of the claims and that the passage at p 12 lines 3-6 shows that the invention as claimed does not need to be inserted so that it is flush with the rock face.

62 Further, J [131] is also clear that the claims of the patent do not require the invention to be installed flush with the rock face (‘The embodiment of the invention shown installed in Figure 3 needs to work while flush with the rock-face, even if it is not required to be installed there.’). The critical idea which appears at both J [131] and [178] is that the Safety System must not, under any circumstance, fall out of the bore hole. At J [131] so much is explicit for it is there stated that any more than de minimis movement of the anchor member would mean that it was ‘possible that the safety system would fall from the bore hole’. At J [178] it is implicit in the statement that the Safety System ‘must work in the installed position illustrated in Figure 3’.

63 Once that is accepted, there is no tension between J [131] and [178] and the suggested error in the trial judge’s approach to the meaning of ‘anchor member’ does not arise. The invention depicted at Figure 3 is installed flush with the rock face. But the invention itself is not so limited. Friable rock may require it to be installed further up the bore. But the fact that the invention at Figure 3 is installed flush with the rock face demonstrates that the anchor member referred to in the claims cannot move by more than a de minimis amount. If it did, it would fall out of the bore hole and the Safety System would not be a safety system at all. The nature of the anchor member does not vary depending on how far into the bore hole the Safety System is inserted for there is no conceivable peg in the language of Claim 1 for such a differential operation. Consequently, if the anchor member does not move in the form of the invention in Figure 3, it does not move when the Safety System is inserted further into the bore hole.

(d) ‘Fixed’ like a ‘rock anchor’

64 The trial judge relied on references in the 556 Patent to the anchor member being ‘fixed’ in the bore like a ‘“split-set” type rock anchor’ to support the conclusion that the anchor member does not move substantially. There are two such references in the patent. The first is at p 4 lines 2-5:

In this way, the anchor member or plug member comprising the split tube can be fixed in the proximal end region of the bore adjacent the rock-face in a friction fit or an interference fit, in a manner similar to that known for a “split-set” type of rock anchor.

65 The second reference is at p 9 line 32 to p 10 line 3:

In this way, the plug member 2 comprised of the split tube 3 can be fixed in the proximal end region E of the bore B adjacent the rock-face F in a friction fit, in a manner similar to that known for a “split-set” type of rock anchor.

66 The trial judge concluded at J [129] that the first passage also ‘supported[ed] a construction where the anchor member does not move substantially’. The Appellant submitted that the trial judge had erred in thinking that the reference to the anchor being fixed in a manner similar to that known for a ‘split-set’ type of rock anchor threw any light on whether the anchor member, once struck by the falling drill bit, could move. On this view, the statement at p 4 lines 2-5 was concerned not with the behaviour of the anchor member after impact but rather with the manner in which the Safety System was installed in the first place.

67 This submission cannot survive the findings at J [137]-[138]:

137 Mr Davison’s initial construction would have the anchor member functioning as an anchor only until it is hit by falling drill rods, at which point it could cease to operate as an anchor and instead slide down the bore. There is nothing in the Patents to support that construction.

138 However, in the joint report, Mr Davison clarified his position. He did not mean that the anchor member held the safety system in place only until such time as it may be struck. He agreed that the anchor member may move by “a few millimetres or more”.

68 Thus the patent provides no warrant for reading ‘anchor member’ as importing different behaviours before and after the descent of the falling drill rod section (as indeed Mr Davison accepted in the Joint Expert Report). The Appellant then submitted that there was no evidence at trial that a ‘rock anchor’ would not move at all when subjected to a sudden load. This is true, however, the trial judge did not say that a rock anchor could not move. Her Honour’s reasoning about rock anchors was not concerned with their peripatetic qualities but rather with whether the word ‘anchor’ was known and used in the mining industry. That this is so is clear from J [143]-[144] where her Honour referred to evidence from Mr Davison concerning a patent he had filed in relation to a ‘split-set anchor’:

143 Mr Davison referred to “split-set anchors” and “a split-set (rock anchor) product” in his written evidence. The term “anchor” is also used by Mr Davison in the specifications of the patents and patent applications for his inventions relating to rock bolts.

144 One example of Mr Davison’s “developments and innovations” relates to a grouted friction stabiliser which uses grout to improve the frictional performance of “split-set anchors” by a factor of about four. That invention is the subject of Australian Patent no. 2014295889 which is entitled “A grouted friction bolt”.

69 It will be seen that the discussion about the split-set anchor fed into her Honour’s consideration of what the word ‘anchor’ meant at J [145]. Mr Davison’s evidence about the split-set anchor was at [17] of his first affidavit and was in these terms:

In the course of my work I have also been responsible for a number of developments and innovations, including several that have been the subject of patent applications and granted patents. A list of the Australian versions of those applications and granted patents is Annexure GRD-3 to my affidavit. Those innovations include a grouted friction stabiliser, which uses grout to improve the frictional performance of split-set anchors by a factor of about four. That product has been commercialised by Gazmick Pty Ltd, of which I am a director. Gazmick licenses its patents to manufacturers who supply the products to mines.

70 GRD-3 was not included in the appeal papers and neither party took the Court to it. What the trial judge then did with Mr Davison’s evidence about rock anchors appears at J [148] which, with respect, is expressed with some care:

Whilst the safety system described and claimed in the Patents is taken to be new and innovative, it is not a new invention of the kind where the patentee is struggling to find the words to adequately describe the concepts involved. The term “anchor” is known and used in the mining industry in the context of fixings. The specification itself makes reference to the friction fit of the anchor member or plug member in the bore being in a manner similar to that known for a “split-set” type rock anchor. In choosing to describe the safety system, the patentee chose to describe the lower member as an “anchor member”, not a braking or checking or restraining member. If the patentee intended to claim a safety system that was held in place until it was struck by a falling drill rod and then moved down the bore hole to eventually stop the broken drill rod from falling out of the hole, there were more apt words available than “anchor”.

71 The trial judge’s conclusion was not that rock anchors could not move. Rather it was that the word ‘anchor’ was known and used in the industry in the context of fixings. That statement is consistent with the evidence of Mr Davison who had himself filed a patent using the expression. Thus, whilst it may be accepted that there was no evidence about whether rock anchors did or did not move, this was not the use to which her Honour put the evidence. Her Honour’s point at J [148] was that the patentee had chosen to use the word ‘anchor’ and that the use in the industry of that word as relating to fixings made it inapt to describe an invention that had a twofold operation; that is to say, an operation where it first fixed the Safety System in place and then, once struck by the falling drill rod section, moved down the bore hole. As such, I do not accept that her Honour erred in the manner suggested by the Appellant.

(e) Suitable for every use

72 The Appellant submitted that in weighing the competing constructions of a patent claim, it is proper to look through the tutored eye of the person skilled in the art and to construe the claim with ‘a generous measure of common sense’: Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue-Gentian LLC [2015] FCAFC 179; 240 FCR 85 at [36] per Kenny and Beach JJ. Thus the person skilled in the art would know that the purpose of the specification is to describe and demarcate the invention. So much may be accepted.

73 Next the Appellant submitted that a common sense approach would include an understanding of the circumstances in which the Safety System would be used and the implications of those circumstances. In that regard, the patent was silent on the conditions under which the claimed movement of the anchor member should be assessed. This was said to recognise the practical reality that the circumstances in which the Safety System would be used could vary greatly. For example, how the Safety System operated in a 5 m bore hole which was closer to the horizontal than it was to the vertical was obviously very different to how it might operate in a bore hole consisting of a vertical shaft of 60 m where the impact force would be very considerable.

74 This mattered because the person skilled in the art would also recognise that the patentee would not have intended to have defined the Safety System in such a way as to exclude commercially useful products. In the example of the vertical 60 m bore hole, it might well be commercially useful to permit the anchor member to move by more than a de minimis amount.

75 I do not accept this submission. As the trial judge correctly observed in the last bullet point of J [98] (set out above) the Safety System needed to work ‘for all the potential forces up to the maximum possible impact force potentially experienced in a bore hole; i.e. whether the drill rod falls from a short distance or from the far end of the bore hole’. The Appellant criticised this statement by submitting that it amounted to a statement that the patent was to be construed as requiring that a single Safety System product should be suitable for every conceivable use.

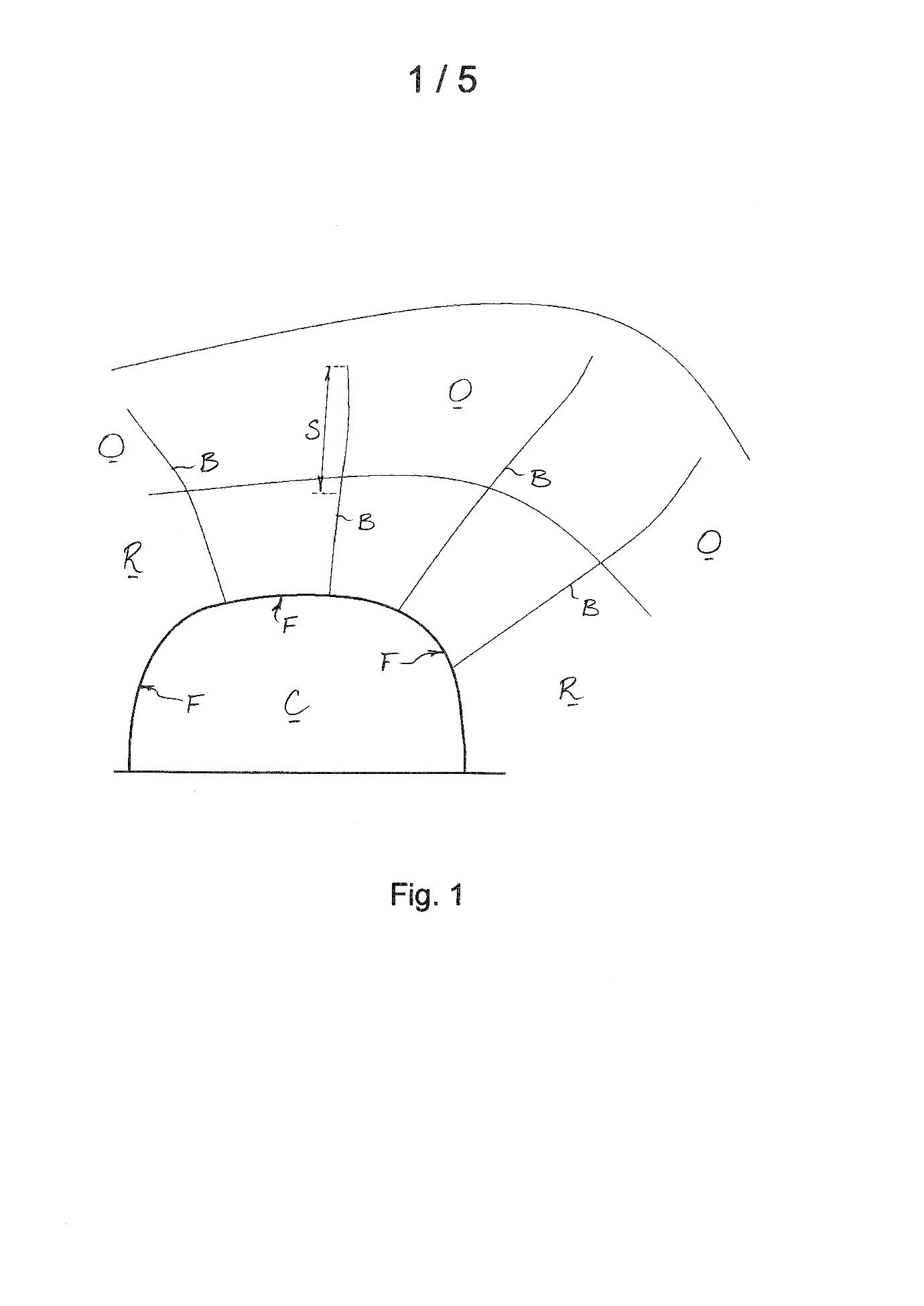

76 The trial judge made no such error. The terms of the patent itself demonstrate that the Safety System was intended to be used in bores of variable lengths and at varying angles from the horizontal. Under the heading ‘Detailed Description of the Embodiments’ the patent referred to Figure 1:

77 At p 8 line 31 to p 9 line 12 this explanation of the bore B is given:

When drilling the multiple bores B upwards into the rock strata R towards the ore body O, the individual bores drilled are often tens of metres long (e.g. in the range of 20 to 60 metres) and the drill rods (not shown) which extend over that length may have a diameter of about 80 millimetres. As the composition and properties of the rock strata R typically varies through its depth, and in any case in comparison to the composition and properties of the ore deposit O, the drill rods are subjected to varying and unpredictable loading during the drilling of each bore B. Failure or breakage of a drill rod is not uncommon when multiple bores B are being drilled to lay the explosive charges above the cavity C. Thus, a section S of drill rod, which may, for example, be 20 or 30 metres long with a mass in the range of 100 kg to 500 kg, may be left in the bore B extending above the cavity C presenting a major hazard to personnel and/or equipment in the cavity C, as this massive broken drill rod section S could unexpectedly fall out of the bore B.

78 It is clear from Figure 1 and this passage that: first, the invention is intended to be used in bores between 20 m and 60 m long and with drill rod sections weighing up to 500 kg; and secondly, that the bore holes will be of varying angles from the horizontal. Thus it is not correct to say that by reasoning that the person skilled in the art would understand that the one Safety System had to work for all the potential forces up to the maximum impact force potentially experienced in the bore hole (as her Honour did in the last bullet point at J [98]) her Honour had thereby construed the patent as requiring that the Safety System be suitable for every conceivable use. Rather, the trial judge simply construed the patent as requiring that the Safety System be suitable for the purposes which the patent itself contemplated. The suggested error was not made by the trial judge.

Conclusions on Grounds 1-3

79 All of the challenges to the trial judge’s reasoning on the meaning of ‘anchor member’ fail. Grounds 1-3 should be rejected.

‘Configured to be fixed in a proximal end region of the bore’ (Grounds 4 and 5)

80 There are two debates between the parties in relation to these grounds. First, how far into the bore does the ‘proximal end region of the bore’ extend? The trial judge concluded that this meant ‘at or near the rock-face’ and that it extended ‘a short distance into the bore’: J [181]. The Appellant takes issue with this and submits that the proximal end region of the bore merely means the end of the bore closest to the bore opening. The second debate concerns the word ‘configured’. The trial judge found that ‘configured’ meant that ‘the anchor member was ‘put together, arranged or constructed so it is suitable for the purpose of being fixed in the proximal end of the bore’: J [175]. The Appellant submits that this conclusion does not entail that the device had, in fact, to be fixed in that location and that the trial judge had erred in concluding otherwise. I deal with these two issues in turn.

The meaning of ‘proximal end region of the bore’

81 According to Claim 1, the anchor member must be ‘configured to be’ fixed in ‘a proximal end region of the bore adjacent to a rock-face’. The Appellant and the Respondents agree that ‘proximal end region’ is not a term of art. There are four areas of debate between the parties as to the meaning of the phrase.

82 First, the Appellant submits that the ‘proximal end region’ is the end of the bore closest to the bore opening. Mr Caine for the Appellant submitted that the ‘proximal end’ was to be contrasted with the ‘distal end’ which is the end furthest from the bore opening: T31.35. Thus, the work done by the words ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ is to confirm that the proximal end of the bore is being discussed. I did not apprehend the Appellant to submit that the bore was to be considered as consisting of two halves, one being the proximal half and the other being the distal half. Rather, the point was that the bore had two ends and that ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ reinforced which end Claim 1 was talking about.

83 If read this way ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ does not say precisely where the anchor member is to be configured to be fixed but rather only for which end of the bore it is to be so configured . It would be possible on this view for the anchor member to be configured to be fixed some way up the bore but not next to the rock face so long as the place where it was configured to be fixed could still be said to be in the proximal end region of the bore. If the Appellant be correct about this, the effect of this construction is to deprive the word ‘adjacent’ in the expression ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ of its ordinary meaning of ‘next to’.

84 I do not accept that ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ operates in this manner. The language of the claim identifies that the anchor member is to be configured to be fixed at the ‘proximal end region of the bore’. Consequently, on the Appellant’s construction, ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ merely tells one something which one already knows: i.e. that the device is not to be inserted at the distal end of the bore. If the claim said that the anchor member was to be configured to be fixed at ‘an end region of the bore’ rather than at the ‘proximal end region of the bore’ then perhaps there might be something to the point. Even then, however, the Appellant would confront the difficulty identified by the Respondents that it is not possible for the anchor member to be configured to be fixed at the distal end because this is inevitably where the broken drill bit is situated. The point of the device is to absorb the force of a falling drill bit. If the device were installed snug against the broken drill bit then it could never fall and the impact reduction member would never have any impact to absorb. As such, the Appellant cannot be correct that the work to be done by the words ‘adjacent to a rock-face’ is merely to confirm the end of the bore in which the anchor member is to be fixed. I reject the argument.

85 Secondly, the Appellant submits that the patent does not teach that the ‘proximal end region’ is of any specific length. In each of Figures 2, 3 and 4 the proximal end region is denoted by the letter ‘E’ and is not specified to be of any particular length. I do not think that anything useful, at least from the Appellant’s perspective, can be obtained from these figures. In all three figures, it is true that the proximal end region of the bore is indicated by the letter ‘E’ without any accompanying explanation of what size precisely that region might be. However, I am unable to glean from Figures 2, 3 and 4 anything which suggests that the invention may be inserted a significant distance up the bore hole. They simply do not address that topic. Further, there is force in the Respondents’ contention that these figures illustrate the invention inserted (or in the case of Figures 2 and 4, partially inserted) into the bore in a zone which is necessarily the proximal end region. Insofar as Figure 3 is concerned the situation for the Appellant is no better. As Ms St John for the Respondents correctly submitted, Figure 3 shows the device inserted flush with the rock face. Whilst Figure 3 does not necessarily mean that the device must always be inserted flush with the rock face (as Ms St John recognised), it is meagre material for an argument that the proximal end region of the bore can extend substantially up the bore. I therefore reject the Appellant’s submission.

86 Thirdly, the Appellant submits that the specification accepted at p 12 lines 1-6 that where the rock face was friable or crumbling the invention could be driven deeper into the bore beyond the rock face. The relevant passage is as follows:

This configuration enables the anchor member 2 and the impact reduction member 5 of the safety system 1 to be driven into the drilled bore B beyond the rock face F. This may be particularly useful where the rock at the rock face F is friable or crumbing, because it enables the safety system 1 to be driven deeper into the bore B beyond the rock face F where it can be soundly founded in competent rock.

87 The trial judge unexceptionally accepted that this was so at J [172]. The Appellant submits, however, that the patent does not set any limit on how far it may in fact be necessary to drive the anchor member beyond the rock face in order to find competent rock. The Appellant also submitted that there was no suggestion of such a limit in the evidence.

88 This submission does not withstand scrutiny. Whilst it is true that the patent does not give a limit to how far the anchor member may be inserted into the bore, the trial judge nevertheless found at J [68] that it was part of the common general knowledge that the first 10-15 cm of rock could be damaged in the blasting process involved in the excavation of the mine corridor beneath the ore body. Her Honour reached this conclusion having accepted Dr Fuller’s evidence to this effect at J [169]. For his part, Mr Davison did not place an estimate on how far the friable rock might extend into the bore but he did accept that such a region nevertheless existed: J [170].

89 As the Respondents correctly submit, there was, therefore, unchallenged evidence about how far up the bore blast-damaged rock extended. Thus, whilst it is true that the patent is silent on how far it may be necessary to drive the anchor member into the bore to overcome the problem of blast-damaged rock, it was common general knowledge that such rock extended no more than 10-15 cm. As such, the fact that the device might be driven an unspecified distance into the bore to overcome the problem of blast-damaged rock provides no warrant for reading the patent as if it permitted the device to be driven further into the bore than would be necessary for that purpose. I would therefore reject the Appellant’s submission.

90 Fourthly, the Respondents submit that the Appellant’s construction does not answer the question which the trial judge necessarily had to answer which was how far up the bore the proximal end region extends. The trial judge asked this question at J [166] and answered that it meant ‘at or the near the rock-face’ and that it extended ‘a short distance into the bore’: J [181]. The Appellant does not cavil with the question which the trial judge posed herself but only with the answer her Honour gave. The Appellant submits that her Honour should have answered the question by saying that the proximal end region of the bore was the ‘lower region of the bore’. I agree with the Respondents’ submission that this formulation does not answer the question. Rather, it exchanges the words used in the claim with words which are not in the claim. I therefore accept this criticism of the Appellant’s construction.

91 Drawing these matters together, I detect no error in the trial judge’s conclusion at J [181] that the anchor member had to be at or near the rock face and could be located a short distance into the bore. It seems to me to have been a common-sense conclusion. The device was required to be located adjacent to the rock face. Adjacent means ‘next to’. There was a possibility that there might be friable rock due to blast damage at the rock face. In that case, the device could be inserted further until hard rock was found which could secure the anchor member. But the person skilled in the art would understand that the friable rock would extend no more than 10-15 cm up the bore. This aspect of Grounds 4 and 5 should therefore be rejected.

The meaning of ‘configured’

92 The Appellant next submits that the trial judge correctly concluded that ‘configured’ meant ‘put together, arranged or constructed’ so as to be suitable for the purpose of being fixed in the proximal end region of the bore: J [175]. Being thus configured did not, however, require the conclusion that this was, in fact, where the device was to be fixed in the bore. The Appellant therefore submitted that the trial judge erred in concluding at J [181] that the device was to be located ‘at or near the rock-face’ which encompassed ‘a short distance into the bore’. What the trial judge said at J [181] was this:

I consider that the skilled reader would understand the totality of the phrase to mean that the anchor member is configured to be fixed at the collar end of the bore, at or near the rock-face. The safety system would be located entirely within the rock part of the bore, with no part extending out into the shotcrete or mine chamber. This would encompass the anchor member being placed a short distance into the bore to be situated beyond the friable rock (if any) so as to be fixed in the competent rock.

93 The Appellant’s contention, as I understood it, relates to the second and third sentences of this passage. The question is whether one reads these sentences as throwing light on the configuration discussed in the first sentence or, instead, as statements about how the device is to be used. I think the former reading is to be preferred. It is clear that Claim 1 does not require the device to be inserted at any particular location. Rather, it requires that the anchor member be ‘configured’ to be fixed in the proximal end region of the bore adjacent to the rock face. It would be surprising if the trial judge had decided to add a requirement to Claim 1 that plainly is not there. The second and third sentences are expressed in the subjunctive mood which is quite inconsistent with the idea that her Honour was, in fact, making a statement about where the device was to be installed. The better reading of the paragraph is that her Honour set out the suitability requirement in the first sentence and that the second and third sentences are to be seen as matters going to that configuration. I therefore do not accept the Appellant’s submission about J [181].

Conclusions on Grounds 4 and 5

94 In those circumstances Grounds 4 and 5 should be dismissed. In the Respondents’ written submissions a point was taken about the wording of Ground 4. On the first day of the appeal leave was granted to file a further amended notice of appeal which overcame this problem. It is not necessary therefore to deal any further with that point.

Infringement (Grounds 7-14)

95 The SafetySpear is a large blue plug-like object made from steel and hard nylon. The instructions which accompany it suggest that it is to be installed in a bore for the purpose of preventing the egress of falling drill rod sections. The SafetySpear looks like this:

96 The Appellant claimed at trial that the SafetySpear infringed Claim 1 of the patent.

97 The first issue on infringement is whether the SafetySpear has an anchor member within Claim 1 and is comprised in Grounds 7-10. It will be observed that the SafetySpear has three plastic expansion rings along it. The Appellant claimed that the shaft of the SafetySpear was an impact reduction member (which is not in dispute) and that the plastic rings were an anchor member within the meaning of Claim 1. The debate about this concerns whether the Appellant had proved that the plastic rings travelled down the bore hole by no more than a de minimis amount when the SafetySpear was struck by a falling drill rod section. The trial judge concluded that it had not been demonstrated that the SafetySpear included a Claim 1 anchor member largely, although not entirely, because there was no experimental evidence before the Court about how the SafetySpear behaved when struck by a falling drill rod section.

98 The second infringement issue is whether the SafetySpear was ‘configured to be fixed in a proximal end region of the bore adjacent to a rock-face’ and is comprised in Grounds 11-14. The debate about this concerned how far up the bore hole the SafetySpear was suitable to be inserted and, in particular, whether it was suitable to be installed adjacent to the rock face. This issue was intertwined with the anchor member issue inasmuch as it involved the Respondents’ contention that the SafetySpear’s braking action was derived from interaction between the three plastic rings and the bore wall as the rings expanded upon the SafetySpear being driven down the bore by the force of the falling drill rod section. On this view of the SafetySpear, it travelled by more than a de minimis amount when struck by the falling drill rod section and, if this were so, installation at or near the rock face would cause it to fall out of the bore, defeating its purpose. The trial judge concluded that the Appellant had not proven that the SafetySpear was suitable to be installed adjacent to the rock face.

Whether the SafetySpear included an ‘anchor member’ (Grounds 7-10)

99 The SafetySpear includes three expansion rings which, putting the matter neutrally at this stage, operate to check the movement of the SafetySpear down the bore when struck by a falling broken drill rod section. Having correctly rejected the Appellant’s construction of the phrase ‘anchor member’ in Claim 1, the issue on infringement before the trial judge became whether these three expansion rings constituted such an anchor member. On the correct construction of that term this then devolved, as the trial judge correctly apprehended, to a factual inquiry into whether the SafetySpear moved by more than a de minimis amount of about 5 mm when struck by a falling broken drill bit. The evidence about this was scant. There was no direct evidence about how the SafetySpear actually operated and neither expert conducted any tests upon it.

100 Instead, both experts gave evidence about how they thought the SafetySpear would behave if struck by a falling drill rod section but their evidence turned on their respective inspections of the SafetySpear and their ruminations about it. Both Dr Fuller and Mr Davison agreed that the SafetySpear could move down the bore when it was struck by a falling drill rod section but they disagreed on the extent of this movement.

101 In addition to this evidence, there was evidence of some drop tests which had been conducted on a prototype of the SafetySpear in August 2020. These tests were conducted at the Carosue Dam mine by the operator of that mine, a firm associated with the Third Respondent: J [191]-[192], [201]. Leaving to one side for now what this actually means, the prototype SafetySpear passed the drop tests and subsequently the mine operator was provided with 200 of the SafetySpears which are the subject of the infringement proceeding (not being the prototype SafetySpear which was the subject of the drop tests). The person who conducted the drop tests was a project manager called Mr Spencer. Mr Spencer provided a report to the mine operator describing what the drop tests showed.

102 The trial judge concluded that the Appellant had not proven that the SafetySpear travelled by no more than 5 mm down the bore when struck by a falling drill rod section. The Appellant takes issue with three aspects of this conclusion.

First issue: the adequacy of the trial judge’s treatment of Mr Spencer’s evidence

103 The Appellant submitted that there was evidence that the SafetySpear did not move down the bore when struck by a falling drill bit. It consisted of the evidence about the August 2020 drop tests. The trial judge did not accept that this evidence showed that the SafetySpear did not move when struck by a falling drill bit: J [218]. The Appellant took issue with this conclusion. It submitted that the trial judge had decided not to accept this evidence because it was based solely on two blurry photographs. The Appellant submits that this was erroneous because there was evidence about the drop tests beyond the two blurry photographs.

104 This was Mr Spencer’s evidence about what he observed during the drop tests. Relevantly, Mr Spencer had said in his report that the SafetySpear had not budged from its original position other than very marginally. He also explained that the photographs in his report did not show the position as clearly as he had observed it.

105 There are two problems with this. First, it is not correct that the trial judge said that the test results were based solely on two blurry photos. In fact, the trial judge explicitly referred to Mr Spencer’s statements ‘to the effect that the SafetySpear had not moved during the trial’ at J [210] and to his statement that ‘the prototype had not moved substantially or budged during the drop test’ at J [215]. In the same passage the trial judge discounted this evidence because it was ‘only a rough estimation, made from where [Mr Spencer] stood below the bore hole watching the test without the benefit of any measurements other than comparing the approximate distance of a painted line on a stick from the shotcrete covered ceiling of the mine’.