Federal Court of Australia

Babet v Electoral Commissioner [2023] FCAFC 164

ORDERS

First Appellant CLIVE FREDERICK PALMER Second Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellants pay the respondent’s costs, to be taxed in default of agreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The hearing of this appeal from final orders of a judge of the Court that were made on 20 September 2023 was expedited and heard on 9 October 2023. After the conclusion of argument, the Court ordered that the appeal be dismissed and that the appellants pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal, with reasons to be published as quickly as the Court was able. These are the Court’s reasons.

Background

2 A writ was issued by the Governor-General to the Australian Electoral Commissioner appointing 14 October 2023 for the taking of votes in relation to a proposed law for the alteration of the Australian Constitution titled Constitution Alteration (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice) 2023. Under s 128 of the Constitution, voting is to be taken in such manner as the Parliament prescribes. For this purpose, the Parliament has enacted the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) (the RMP Act).

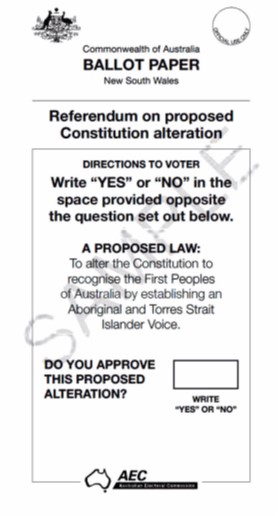

3 The form of ballot paper to be used in a referendum is prescribed by s 25 of the RMP Act, and must be in accordance with Form B of Schedule 1. The ballot paper for the upcoming referendum is in the following form:

4 Section 24 of the RMP Act provides that each elector shall indicate his or her vote in the following way:

24 Manner of voting

The voting at a referendum shall be by ballot and each elector shall indicate his or her vote:

(a) if the elector approves the proposed law—by writing the word “Yes” in the space provided on the ballot paper; or

(b) if the elector does not approve the proposed law—by writing the word “No” in the space so provided.

5 The results of a referendum are to be ascertained by scrutiny in accordance with Pt VI of the RMP Act. Section 90(1)(e)(iv) of the Act requires each Assisting Returning Officer to count the number of ballot papers with votes given in favour of the proposed law, the number of ballot papers with votes given not in favour of the proposed law, and the number of informal ballot papers.

6 Central to the arguments presented by the parties is s 93(1)(b) of the Act, which provides that “[a] ballot paper is informal if … it has no vote marked on it or the voter’s intention is not clear.”

7 Complementing s 93(1)(b) are s 93(8) and (9), which provide:

(8) Effect shall be given to a ballot paper of a voter according to the voter’s intention, so far as that intention is clear.

(9) For the purposes of subsection (8):

(a) a voter who writes the letter “Y” in the space provided on the ballot paper is presumed to have intended to approve the proposed law; and

(b) a voter who writes the letter “N” in the space provided on the ballot paper is presumed to have intended to not approve the proposed law.

The appeal

8 The appellants, Senator Babet and Mr Palmer, are Australian citizens whose names appear on a roll of electors maintained under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth), and each is entitled to vote in the referendum as an “elector” for the purposes of s 128 of the Constitution. In addition, Senator Babet, is a member of the Australian Senate who was elected for the State of Victoria in 2022, and was a member of the Senate when it passed the proposed law.

9 The appellants commenced a proceeding in this Court against the Electoral Commissioner seeking a declaration that, pursuant to s 93(8) of the RMP Act, effect shall be given to any ballot papers containing a cross (“✕”) written alone in the space provided, by treating such ballot papers as clearly demonstrating the voter’s intention that he or she does not approve the proposed law. In the alternative, the appellants sought a declaration that any ballot papers containing a tick (“✓”) written alone in the space provided do not clearly demonstrate the voter’s intention for the purpose of section 93(8) of the Act, and are to be treated as informal pursuant to s 93(1)(b). In addition, the appellants sought an order restraining the Electoral Commissioner from instructing scrutineers or any other officer than in accordance with the declarations sought.

10 The appellants submitted to the primary judge that the Court had jurisdiction to hear the matter and to make the orders that were sought pursuant to the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth), s 39B(1) and (1A)(c), which relevantly confer original jurisdiction in any matter in which an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth, and arising under any laws made by the Parliament. The appellants submitted that the power to grant the remedies that they sought was conferred by the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), s 21.

11 The primary judge dismissed the proceeding. His Honour did not decide what he described at J [43] as the “somewhat vexed issue” of whether the appellants had standing to seek relief, citing: Combet v The Commonwealth [2005] HCA 61; (2005) 224 CLR 494 (Combet) at [31] per Gleeson CJ; at [164] per Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ; Wilkie v Commonwealth [2017] HCA 40; (2017) 263 CLR 487 (Wilkie) at [56]–[57] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ; and Phong v Attorney-General (Cth) (2001) 114 FCR 75 (Phong) at [4] per Black CJ, at [43] per Beaumont J, and at [59], [70]–[71] per Hely J. His Honour addressed the underlying substance of the appellants’ claims, holding that a tick manifests a clear intention to vote in favour of the proposed law, but that a cross is inherently ambiguous as to the voter’s intention.

12 The issues that arise from the appellants’ grounds of appeal are as follows:

(1) did the primary judge err in refraining from deciding the question of standing (Ground 1);

(2) should the judge have found that the appellants, or either of them, had standing (Ground 2);

(3) was the judge in error in finding that a tick written alone would demonstrate a voter’s intention for the purposes of s 93(8) of the Act (Ground 3); and

(4) in the alternative, did the judge err in finding that a cross written alone would fail to demonstrate a voter’s intention for the purposes of s 93(8) of the Act (Ground 4)?

13 Issue (2) would have to be resolved in the appellants’ favour before the Court could make the orders that the appellants sought on appeal, which were as follows:

(a) A declaration that any ballot papers containing a tick (“✓”) written alone in the space provided do not clearly demonstrate the voter’s intention for the purpose of section 93(8) of the RMP Act, and are to be treated as informal pursuant to section 93(1)(b) of the RMP Act.

(b) Alternatively, a declaration that, pursuant to section 93(8) of the RMP Act, effect shall be given to any ballot papers containing a cross (“✕”) written alone in the space provided, by treating such ballot papers as clearly demonstrating the voter’s intention that he or she does not approve the proposed law.

(c) An order restraining the Respondent from instructing scrutineers or any other officer within the meaning of section 3 of the RMP Act other than in accordance with the declaration sought above.

14 We observe that the declarations sought on appeal inverted the order of the declarations that were sought below. The primary declaration sought on appeal was that a tick is to be treated as informal, and a declaration that a cross is to be treated as clearly demonstrating a voter’s intention was sought only in the alternative.

15 If, as the Commissioner submitted, the Court did not make the orders sought by the appellants on the ground that the underlying claims have not been established, an issue arises as to whether the Court must resolve issues (1) and (2) before it would have authority to dismiss the appeal.

Further background

16 The Commissioner has published several documents:

(a) a document titled Scrutineers Handbook: Federal Elections, By-elections, Referendums published in July 2023 (the Scrutineers Handbook);

(b) a document titled Ballot Paper Formality Guidelines: Federal elections, By-elections, Referendums dated 14 August 2023 (the Formality Guidelines);

(c) a document titled EPH, Election Procedures Handbook, Referendum (the Election Procedures Handbook); and

(d) a media release titled, Media advice; Referendum voting instructions dated 25 August 2023 (the AEC Media Release).

The Scrutineers Handbook

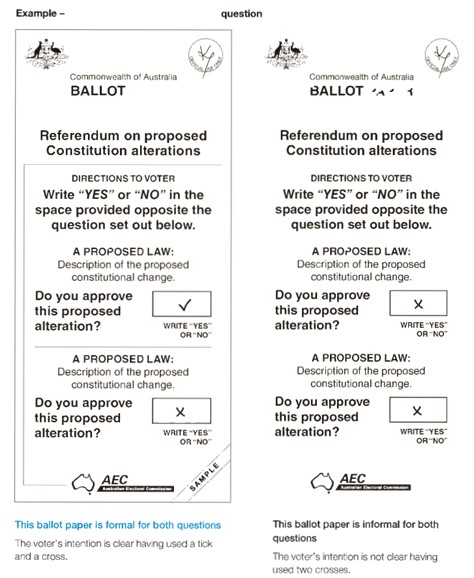

17 In an election for the Senate or the House of Representatives, scrutineers may be appointed by candidates for election: Commonwealth Electoral Act, s 217. In the case of referendums, scrutineers may be appointed by the Governor-General, the Governors of the States, the Chief Minister of the Australian Capital Territory, the Administrator of the Northern Territory, or their delegates, or by the registered officer of a registered political party: RMP Act, ss 27, 73CA, 89. The Scrutineers Handbook is a document of about 70 pages that states that its purpose is to help scrutineers “before, during and after polling day to be as effective as possible as a scrutineer”. The Handbook covers a wide range of topics relating to the appointment, role, rights, and conduct of scrutineers at elections and referendums. One section of the Scrutineers Handbook is titled Formality of votes. It states that a scrutineer has the right to challenge the admission or rejection of a ballot paper. There are many samples of formal and informal ballot papers that are set out under guidelines for elections for the House of Representatives and the Senate, and for referendums. None of the examples involves a ballot paper for a referendum with a single question where either a tick or a cross is placed in the box. There are, however, examples of formal and informal ballot papers where there is more than one question:

The Formality Guidelines

18 As with the Scrutineers Handbook, the Formality Guidelines relate to elections for the House of Representatives and the Senate, and also referendums. The Formality Guidelines are directed to those persons responsible for making decisions in relation to the counting of ballot papers. Like the Scrutineers Handbook, there are many examples of formal and informal ballot papers that are included as guidance. The two referendum ballot papers involving two questions that are set out above are also set out in the Formality Guidelines.

The Election Procedures Handbook

19 The Election Procedures Handbook is a document of over 100 pages that is directed to polling place liaison officers, officers-in-charge, and second-in-charge at static polling places. The handbook sets out five over-arching principles that must be considered when determining the formality of any ballot paper:

Principle one

Start from the assumption that the voter has intended to vote formally

The assumption needs to be made that a voter who has marked a ballot paper has done so with the intention to cast a formal vote.

Principle two

Establish the intention of the voter and give effect to this intention

When interpreting markings on the ballot paper, these must be considered in line with the intention of the voter.

Principle three

Err in favour of the franchise

In the situation where the voter has tried to submit a formal vote (i.e. the ballot paper is not blank or defaced), the concept of reasonableness should be applied to questions of formality and wherever possible be resolved in the voter’s favour.

Principle four

Only have regard to what is written on the ballot paper

The intention of the voter must be unmistakable, i.e. do not assume what the voter was trying to do if it’s not clear – only consider what is written on the ballot paper.

Principle five

The ballot paper should be construed as a whole

By considering the number in each box as one in a series, not as an isolated number, a poorly formed number may be recognisable as the one missing from the series.

20 The Election Procedures Handbook then addresses ticks and crosses written on ballot papers in response to the question whether the voter approves the proposed alteration to the Constitution, stating that ticks are capable of clearly demonstrating the voter’s intention, whereas a cross on its own may mean either “yes” or “no”:

The prescribed method of recording a vote in a referendum is to use the words ‘yes’ or ‘no’ written alone (i.e. without qualification). In all cases, however, ballot papers must be admitted where the voter’s intention is clear. Words, stamps, or stickers with the same meaning as ‘yes’ or ‘no’ (e.g. ‘definitely’ or ‘never’), an indication of either ‘Y’ or ‘N’, as well as ticks (✓) are all capable of clearly demonstrating the voter’s intention. A vote at a referendum will be informal if any of the following apply:

• no vote is marked on the ballot paper

• it has more than one vote mark on the ballot paper

• terms are used that convey indecision and uncertainty, such as ‘not sure’, or

• a cross (✕) is used on a referendum ballot paper which has only one question, since a cross on its own may mean either ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

The AEC Media Release

21 The AEC Media Release refers to legal advice that in answer to a single question on a ballot paper for a referendum a clear ‘tick’ should be counted as formal and a ‘cross’ should not:

Like an election, the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 includes ‘savings provisions’ – the ability to count a vote where the instructions have not been followed but the voter’s intention is clear.

• The AEC cannot ignore the law and cannot ignore savings provisions.

The law regarding formality in a referendum is long-standing and unchanged through many governments, Parliaments, and multiple referendums. Legal advice from the Australian Government Solicitor, provided on multiple occasions during the previous three decades, regarding the application of savings provisions to ‘ticks’ and ‘crosses’ has been consistent – for decades. This is not new, nor a new AEC determination of any kind for the 2023 referendum. The law regarding savings provisions and the principle around a voter’s intent has been in place for at least 30 years and 6 referendum questions.

The longstanding legal advice provides that a cross can be open to interpretation as to whether it denotes approval or disapproval: many people use it daily to indicate approval in checkboxes on forms. The legal advice provides that for a single referendum question, a clear ‘tick’ should be counted as formal and a ‘cross’ should not.

Other features of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth)

22 Other features of voting in referendums provided for by the RMP Act are as follows. Voting is generally to be undertaken in private, in a polling booth, and the elector is to fold the ballot paper to conceal the vote: s 35. Voting is compulsory for electors, and failure to vote without a valid and sufficient reason is a strict liability offence and may result in a penalty: s 45.

23 The validity of any referendum or of any return or statement showing the voting at a referendum may be disputed by the Commonwealth, by any State, by the Australian Capital Territory, or by the Northern Territory, by petition addressed to the High Court: s 100. The Electoral Commissioner may also petition to dispute the validity of a referendum: s 102. Section 103 provides for the jurisdiction and powers of the High Court:

103 Jurisdiction and powers of High Court

(1) The High Court has jurisdiction with respect to matters arising under this Part.

(2) Following the hearing of a petition in relation to a referendum, the High Court may:

(a) declare the referendum to be void;

(b) uphold the petition in whole or in part; or

(c) dismiss the petition.

(3) The High Court may exercise all or any of its powers under this section on such grounds as the Court in its discretion thinks just and sufficient.

(4) Without limiting the generality of this section, the High Court may exercise its powers to declare a referendum void on the ground that contraventions of this Act or the regulations were engaged in in connection with the referendum.

24 The High Court must make its decision on a petition as quickly as is reasonable in the circumstances (s 107AA) and can have regard to rejected ballot papers (s 107A), but, importantly, s 108(1) provides:

108 Immaterial errors not to invalidate referendum

(1) A referendum or a return or statement showing the voting at a referendum shall not be declared void on account of:

(a) any delay in relation to:

(i) the taking of the votes of the electors; or

(ii) the making of any statement or return; or

(b) the absence of any officer or any error of, or omission by, an officer;

that did not affect the result of the referendum.

25 Part XI of the RMP Act is titled “Miscellaneous”. Within Pt XI, s 139 confers jurisdiction on the Federal Court of Australia, on the application of the Electoral Commission, to grant an injunction in respect of actual or apprehended contraventions of the RMP Act or any other law of the Commonwealth in its application to referendums. However, s 139(10) provides that the powers conferred on the Federal Court by s 139 are in addition to, and not in derogation of, any other of its powers however conferred.

The appellants’ submissions

Standing (Grounds 1 and 2)

26 The appellants submitted that the primary judge had been in error in dismissing the proceeding without determining as the “first duty” of the Court the question of the appellants’ standing, which in the case of an application for declaratory and injunctive relief in federal jurisdiction is subsumed in the constitutional requirement that there be a matter: see, Hazeldell Ltd v The Commonwealth [1924] HCA 36; (1924) 34 CLR 442 (Hazeldell) at 446 per Isaacs ACJ. It was submitted that the question of jurisdiction had been fully contested below, and that the primary judge should have resolved that dispute before turning to the merits, lest the consideration of the merits amounted to no more than an advisory opinion. The appellants submitted that this Court should consider the question of standing first, and that in the event that it were held that the appellants did not have standing, to take the course of pragmatism suggested by the Hon Justice Leeming in his text, Authority to Decide (2nd Ed, 2020, Federation Press) at p 41, and deal with the merits in the alternative.

27 The appellants’ primary submission on standing was that they both have standing as electors within the meaning of s 128 of the Constitution and s 3 of the RMP Act, and that considerations bearing on the public interest weigh heavily in favour of recognising the standing of electors to seek relief clarifying the operation of laws governing the counting of votes at referendums. That is especially so given the central constitutional role of electors, and that electors do not have standing to petition the High Court and dispute the returns. The appellants noted by way of comparison that electors are given standing under s 355(c) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act to dispute an election result by a petition filed in the High Court. The significance of this was said to be threefold: (1) it assuages concerns about the opening of “floodgates” upon electors being recognised as having standing; (2) it is a statutory recognition that every elector has a real or sufficient interest in the outcome of voting; and (3) the principles of standing should be applied in a way that is coherent with the wider legal context, which includes the statutory standing given to electors in elections.

28 The appellants’ case was not advanced on the basis that they propose to vote in the referendum in any way other than consistently with what is required by s 24 of the RMP Act by writing “yes” or “no” on the ballot paper. Rather, it was submitted that as electors the appellants have an interest in the votes of all other electors being counted lawfully, so that their own voting power is not diluted by the votes of other electors which should be rejected as being informal instead being treated as formal. The appellants submitted that the questions that they have raised in the proceeding are concrete questions that arise from the Electoral Commissioner’s published position, that are not hypothetical, and are suitable for determination.

29 In the alternative, the appellants submitted that the first appellant, Senator Babet, has standing as a member of the Parliament that passed the proposed law that is the subject of the referendum, citing the dissenting judgments in Combet of McHugh J at [97] and Kirby J at [309] (see also [308]), the majority not addressing the issue.

The marking of a tick by a voter (Ground 3)

30 The primary declaration that the appellants sought on appeal was that a ballot paper with a sole tick placed in the box by a voter should be treated as informal, with the consequence that it is not to be counted as a vote in favour of the proposed law. The appellants submitted that a tick alone is not sufficiently certain to make a voter’s intention clear for the purposes of s 93(8) of the RMP Act. The appellants submitted that context is important because a tick is a symbol, rather than an English word, and could have a variety of different meanings to people across the voting population which is multiculturally and generationally diverse. It was submitted that in assessing whether a tick is a clear indication of voter intention, the starting point is to read the ballot paper as a whole. The appellants relied on the emphatic directions to voters in two places on the ballot paper to write “YES” or “NO”. It was also submitted that important context for understanding voter intention is the provisions of the RMP Act, and in particular the effect of s 45 by which voting is compulsory. The appellants relied on Kane v McClelland [1962] HCA 26; (1962) 111 CLR 518 (Kane v McClelland), to which we will return, to support a submission that voting intention would not be clear from the use of a sole tick if there are different hypotheses of plausible voter intention that are available, and that the ascertainment of voter intention by making a shrewd guess, or by drawing an inference, does not reach the level of clarity that is required, which is that the intention be unmistakeable or indisputable.

31 It was submitted that there were two other available explanations or hypotheses for the use of a tick in the specific context of the ballot paper in question. The first is that the voter did not read or understand the ballot paper, and that a tick might be understood as non-responsive. This hypothesis arises in circumstances where it was submitted that the ballot paper clearly states that “yes” or “no” should be written in response to the question. The second hypothesis is that in the context where voting is compulsory, the voter treated the exercise as a mere formality without wishing to indicate an intention one way or the other by “ticking the box”. For these reasons, it was submitted that a tick does not manifest an unmistakeable or indisputable intention.

The marking of a cross by a voter (Ground 4)

32 If the appellants’ submissions in relation to the use of a tick alone were accepted, then they did not pursue any relief in relation to the use of a cross alone. However, the appellants argued in the alternative that a cross written alone in the box provided on the ballot paper demonstrates a voter’s intention that he or she does not approve the proposed law, and that this is the only plausible explanation for the use of a cross.

An additional matter

33 The appellants submitted that the Electoral Commissioner’s position in relation to the use of ticks and crosses amounts to inconsistent treatment that creates a real risk of a perception that the Electoral Commissioner is favouring one political outcome over the other. It was submitted that it is fundamental to the legislative scheme that the Electoral Commissioner be, and appear to be, apolitical or non-partisan, and that by treating a tick written alone as a formal vote, but a cross written alone as informal, an appearance of partiality arises. It was submitted that this underscores the incorrectness of the reasoning and the result below. In support of this submission, the appellants cited Palmer v Australian Electoral Commission [2019] HCA 24; (2019) 269 CLR 196 (Palmer) at [66]–[67] per Gageler J. In argument, senior counsel for the appellants disclaimed any suggestion that the Electoral Commissioner, or any of his officers, were or are acting in a way that is actually biased.

34 It is convenient to address these submission immediately. Palmer involved a challenge to the practice of the Electoral Commission of publishing in elections for the House of Representatives indicative two-candidate preferred counts (referred to as TCP Information) for certain Divisions after polling in those Divisions had closed, but while polling remained open in other Divisions in other places in Australia. The publication of TCP Information was authorised by statute, but the challenge was to the timing of the publication. Amongst other things, the plaintiff had submitted that the publication of TCP Information prior to the close of polling in all Divisions gave rise to the Electoral Commission giving its imprimatur to particular candidates or outcomes.

35 The challenge in Palmer was held to lack a factual foundation because it was not demonstrated that the practice had any effect on electoral choices, and therefore there was nothing to support a finding that the publication of the TCP Information prior to polls closing across the nation distorted the voting system in any relevant way, and nor was it established that voting may be affected: see at [30], [36]–[37] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ. As a result of the absence of a factual foundation, the plurality found it unnecessary to address the plaintiff’s submissions that the Commission’s practice contravened an implied statutory limitation against partiality: see, at [51]. Gageler J, writing separately, addressed the question of partiality at [66]–[67]:

66 Fundamental to the scheme of the Electoral Act, and inherent in the Commission’s composition, was that the Commission be and appear to be apolitical or non-partisan. That character of political neutrality was inherent in the composition of the Commission, quite apart from being implicit in the nature of its functions. The Electoral Act required that the Commission consist of: a chairperson who was a Judge or former Judge of the Federal Court of Australia chosen from a list of names submitted to the Governor-General by the Chief Justice of that Court (60); an Electoral Commissioner, who was an Agency Head for the purpose of the Public Service Act 1999 (Cth) (61); and a non-judicial appointee holding an office of, or an office equivalent to that of, Agency Head within the meaning of that Act (62).

67 There would, in my opinion, have been an imminent departure from the scheme of the Electoral Act in that important respect were the timing of the proposed publication of the TCP Information by the Commission to have been likely to have favoured, or to have created an appearance of favouring, other candidates over the plaintiffs or other political parties over the United Australia Party. The difficulty for the plaintiffs was that neither effect was self-evident and neither effect was shown on the agreed facts or able to be found by any inference capable of being drawn from the academic writing on which the plaintiffs relied.

(Footnotes omitted.)

36 The central issues on this appeal are different. They are not concerned with a decision about which the Electoral Commissioner has a discretionary choice, as with the timing of publication TCP Information. Rather, the issues here concern the objective evaluation of handwritten marks on ballot papers and whether, against a statutory standard, a voter’s intention is clear. If the Electoral Commissioner’s guidance on this issue is correct, there is no room to question whether, by reference to objective standards such as those referred to in Isbester v Knox City Council [2015] HCA 20; (2015) 255 CLR 135 at [20]–[23] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane and Nettle JJ, at [58]–[59] per Gageler J, the fair-minded lay observer with requisite knowledge of the statutory framework might think that the Electoral Commissioner or his officers might not be acting with neutrality. And even if the Electoral Commissioner’s views were wrong, the Commissioner’s views are so clearly arguable that, without more, the appearance of neutrality is not brought into question.

37 It is also to be observed that the Electoral Commissioner has from time to time since at least 1988 received consistent legal advice from the Australian Government Solicitor with regard to how referendum ballots with only a tick or a cross in the box provided should be treated. The guidance included in the various documents canvassed above is based on that advice. There can therefore be no suggestion that the Electoral Commissioner has given that guidance only or particularly for the present referendum, or that he has given it other than on the basis of independent legal advice.

The respondent’s submissions

38 The respondent accepted that, subject to the question of standing, the Federal Court of Australia has jurisdiction to determine the matter pursuant to the Judiciary Act, s 39B. It was submitted that the jurisdiction of the Court is not displaced by the distinct jurisdiction conferred on the High Court by Pt VIII of the RMP Act in relation to disputed returns. It was further submitted that, all other things being established, there are no discretionary reasons militating against the Court making the primary or the alternative declaration sought by the appellants.

39 The respondent did not accept that the Court is required to determine the question of standing. It was submitted that because this is an appeal from orders and not reasons, issue (1), which concerns whether the primary judge was required to address standing, does not arise and that the question of standing arises only if the Court accepts the appellants’ arguments in relation to issues (3) or (4). It was submitted that this situation arises because a necessary step in finding error in the primary judge’s orders is to reverse one of the judge’s findings in relation to the writing of ticks or crosses on ballot papers. The respondent observed that there is somewhat of an inconsistency in the appellants’ position, which is that standing is an essential question to be determined, but that if it were determined adversely to the appellants, the merits of the underlying issues should nonetheless be addressed for pragmatic reasons.

40 In the event that it is necessary for the Court to determine the question of standing, then the respondent submitted that the appellants lack standing. It was submitted that, as the appellants did not seek declarations of personal rights or liabilities, they must establish an interest in that relief other than that which any other member of the public has in upholding the law generally, citing Unions NSW v New South Wales [2023] HCA 4; (2023) 407 ALR 277 (Unions NSW) at [22] per Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Gleeson and Jagot JJ. It was submitted that the appellants’ identity as electors did not give them a sufficient interest in the relief sought, as the appeal does not concern how the appellants’ own votes are to be counted but could affect only the franchise of other electors. The appellants’ interest as electors does not make them special, but is an interest shared with millions of others. The respondent characterised this interest as only “intellectual or emotional”, which is insufficient to found standing, citing Australian Conservation Foundation Inc v Commonwealth [1980] HCA 53; (1980) 146 CLR 493 (Australian Conservation Foundation) at 530 per Gibbs J (as his Honour then was). The respondent contrasted the position of the appellants with appointed scrutineers, whom it was submitted would have standing because they perform a special function under the RMP Act and who, unlike electors at large, do have a special interest in ensuring the proper conduct of the referendum. It was also submitted that a registered officer of a registered political party has standing, but that the appellants are not associated with any registered political party, it being an agreed fact that the United Australia Party, with which they had been associated, was deregistered as a political party on 8 September 2022.

41 The respondent submitted that the first appellant’s status as a senator who is a member of the Parliament that passed the proposed law gives him no special interest in the relief sought. The respondents characterised the relief sought by the first appellant as being concerned with the application of the RMP Act, which was passed in 1984 long before the first appellant became a senator, and not the Constitution Alteration (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice) 2023. It was further submitted that the first appellant’s role in the events leading to the referendum was complete in any case. It was submitted that once a writ for a referendum was issued under s 7 of the RMP Act, and proposed pamphlet arguments were forwarded to the respondent under s 11 for distribution, members of the Parliament do not enjoy any privileged position or power in respect of a referendum. As a consequence, it was submitted that the first appellant’s interest and role in the conduct of the referendum is now solely as an elector whose interest in ensuring the correct application of the law is no different from the interest that all other members of the community have. The respondent submitted that Combet, in respect of which the appellants relied on passages in the dissenting judgments of McHugh J and Kirby J, is distinguishable. It was submitted that Combet was concerned with a relevantly different context, given the special relationship of the legislature and the executive under s 83 of the Constitution in respect of appropriations.

42 As to issue (3), and whether a single tick inside the box on the ballot paper gives rise to a clear intent, the respondent submitted that the primary judge correctly found, at J [40]–[42], that a tick would manifest a clear intention to approve the proposed law. The respondent supported the primary judge’s reasoning at J [41] that a tick signifies assent or approval. It was submitted that in the context of the ballot paper that posed one question that requires a “Yes” or “No” answer, a tick is effectively a graphic synonym for “Yes”. As for the other explanations or hypotheses for the use of a tick on which the appellants relied, the respondent submitted that they are fanciful. It was submitted that a tick placed inside the box obviously engages with the question, and cannot be regarded as a non-response. As to the appellants’ submission that a tick inside the box does not convey a clear intent because it shows that the voter might have misunderstood the process, the respondent submitted in response that it would be irrational and objectively improbable for a voter to place a tick inside the box if the voter did not intend to convey a favourable response to the question posed.

43 Finally, as to issue (4), which concerns a single cross inside the box on the ballot paper, the respondent submitted that a cross in answer to the question on the ballot paper would be “inherently ambiguous”, as the primary judge held at J [39]. It was submitted that a cross falls short of indicating, in a clear, unmistakable, or indisputable way, the intention of the voter either to approve or not approve the proposed law. That is because while a cross may indicate disapproval, it is also commonly used to indicate approval, including in the voting context.

Grounds 1 and 2

The issue identified

44 This Court’s jurisdiction to hear an appeal from the judgment or, in this case, the order made by the primary judge, derives from s 24(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act and the Court’s powers on appeal include affirming the order appealed from or setting it aside and making such orders “as, in all the circumstances, it thinks fit” (s 28(1)(a), (b) and (c)).

45 The primary judge’s jurisdiction in this case is derived from s 39B of the Judiciary Act which in turn has its basis in s 77 of the Constitution. The primary judge’s jurisdiction was restricted to a “matter” of a type identified in s 39B. There was an issue before the primary judge as to whether the proceeding before him involved a matter within s 39B. In this case, the appellants sought declaratory and injunctive relief against an officer of the Commonwealth concerning the application of provisions of a law of the Parliament being the RMP Act. There can be no doubt that the Court below had jurisdiction over the subject matter of the proceeding (s 39B(1), (1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act; s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act) and the only issue was whether the other aspect of “matter” was satisfied.

46 Stating the matter broadly, and assuming the subject matter requirement is satisfied, for a matter to exist there must be an “immediate right, duty or liability to be established by the determination of the Court” (Re Judiciary and Navigation Acts (1921) 29 CLR 257 at 265; Fencott v Muller [1983] HCA 12; (1983) 152 CLR 570; Truth About Motorways Pty Ltd v Macquarie Infrastructure Investment Management Ltd [2000] HCA 11; (2000) 200 CLR 591). More recently, the plurality in Unions NSW described the relevant requirement in the following terms (at [15]):

Exceptional categories aside, there can be no “matter” within the meaning of Ch III of the Constitution unless “there is some immediate right, duty or liability to be established by the determination of the Court” in the administration of a law and unless the determination can result in the Court granting relief which both quells a controversy between parties and is available at the suit of the party seeking that relief. …

(Citations omitted.)

47 The parties in this case, and the primary judge, proceeded on the basis that the issue of whether the appellants’ proceedings involved a matter turned on whether the appellants had standing to seek declaratory (and injunctive) relief. The link between the two has been noted by the High Court on many occasions: Croome v State of Tasmania [1997] HCA 5; (1997) 191 CLR 119; Bateman’s Bay Local Aboriginal Land Council v Aboriginal Community Benefit Fund Pty Ltd [1998] HCA 49; (1998) 194 CLR 247 at 262 per Gaudron, Gummow and Kirby JJ. The approach of the parties and the primary judge was correct: Hobart International Airport Pty Ltd v Clarence City Council [2022] HCA 5; (2022) 96 ALJR 234 at [29]–[31] per Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gordon JJ; at [49] per Gageler and Gleeson JJ; at [79]–[80] per Edelman and Steward JJ.

48 The standing to seek declaratory (and injunctive) relief means some interest over and above a mere intellectual or emotional concern. In a well-known passage in Australian Conservation Foundation, Gibbs J said (at 530–531):

I would not deny that a person might have a special interest in the preservation of a particular environment. However, an interest, for present purposes, does not mean a mere intellectual or emotional concern. A person is not interested within the meaning of the rule, unless he is likely to gain some advantage, other than the satisfaction of righting a wrong, upholding a principle or winning a contest, if his action succeeds or to suffer some disadvantage, other than a sense of grievance or a debt for costs, if his action fails. A belief, however strongly felt, that the law generally, or a particular law, should be observed, or that conduct of a particular kind should be prevented, does not suffice to give its possessor locus standi. If that were not so, the rule requiring special interest would be meaningless. Any plaintiff who felt strongly enough to be bring an action could maintain it.

(See also another early example, Onus v Alcoa of Australia Ltd [1981] HCA 50; (1981) 149 CLR 27 (Onus v Alcoa of Australia).)

49 In the recent case of Unions NSW, the plurality addressed the issue of standing in some detail. The passage is a lengthy one, but, with respect, it bears repetition in full. The plurality said (at [22]):

But when a plaintiff seeks a declaration not of personal rights or liabilities – for example, a declaration of invalidity of a law for breach of the implied freedom of political communication, which is not a personal right – a plaintiff must establish an interest other than that which any other ordinary member of the public has in upholding the law generally. A person is not sufficiently interested “unless [they are] likely to gain some advantage, other than the satisfaction of righting a wrong, upholding a principle or winning a contest, if [their] action succeeds or to suffer some disadvantage, other than a sense of grievance or a debt for costs, if [their] action fails”. The test for a sufficient interest is broad and flexible, varying according to the nature and subject matter of the litigation. However, whether a plaintiff’s interest is sufficient is a question of degree, not a question of discretion. The plaintiff must show that “success in the action would confer on [them] ... a benefit or advantage greater than [that] conferred upon the ordinary member of the community; or ... relieve [them] of a detriment or disadvantage to which [they] would otherwise have been subject ... to an extent greater than the ordinary member of the community”. They must have more than a mere intellectual or emotional concern, and more than a belief, however strongly held, that the law or the Constitution should be upheld. As Croome demonstrates, a plaintiff may have a sufficient interest where their freedom of action is particularly affected by the impugned law. Other cases, such as Onus v Alcoa of Australia Ltd, demonstrate that the breadth of the categories of interest include economic, cultural and environmental interests.

(Citations omitted.)

50 In this case, the appellants claimed standing on the basis that they were electors qualified to vote for the election of the House of Representatives within s 128 of the Constitution. There was no dispute that they held that status. There was a dispute as to whether that was sufficient to confer standing. The first appellant also relied on the fact that he had been elected as a member of the Australian Senate.

51 As to the first basis for standing, the way in which the appellants put their case was that their respective interests as electors in the Referendum and the outcome thereof would be diluted if ticks were wrongfully admitted as “Yes” votes or if crosses were wrongfully treated as informal votes. Counsel for the appellants sought to draw an analogy between the appellants’ interest and a shareholder interested in the outcome of a meeting of members of the company. In the latter case, the effect of the shareholder’s vote may be diluted if votes are wrongfully admitted or excluded.

52 In this context, a point arose in this Court as to whether the treating of a cross as a formal “No” vote or as an informal vote would have any effect on the issue of whether the proposal which is the subject of the Referendum was approved. The Court was told by counsel for the respondent that for the purposes of determining whether a majority of electors has approved the proposed law under s 128 of the Constitution only formal votes are counted or considered by the respondent. The Court was also told that there had been no judicial consideration of the issue. Counsel for the appellants referred the Court to two articles addressing the issue: Handley KR, “Informal Votes at a Constitutional Referendum” (2011) FLR Vol 39 509; Orr G, “The conduct of referenda and plebiscites in Australia: a legal perspective” (2000) PLR Vol 11 117. This Court does not need to determine this issue because insofar as it may be relevant to standing, we are not determining that issue, and insofar as it may be relevant to utility, it is common ground before the primary judge and before this Court that a determination of the issues would be utile and resolve important questions.

53 The primary judge decided that he would not decide the issue of standing and he dismissed the proceeding on the merits. His Honour summarised the parties’ respective submissions on standing and he noted that those submissions were made in a context (as we have said) in which both parties accepted that there was utility in answering the issues raised on the merits and thereby resolving important questions (at J [25]). The primary judge said that the appellants’ argument as to standing raised unresolved issues of considerable public importance because of their constitutional implications. His Honour considered that the issue of standing was difficult, complex and raised important issues of principle that had not been fully explored in the limited time available (at J [47]). His Honour considered that he had a discretion to deal with the merits without resolving the issue of standing and he exercised that discretion in favour of doing so. In this context, his Honour referred to the authorities identified above (at [11]).

54 A Notice of Constitutional matter under s 78B of the Judiciary Act was served, but no Attorney-General sought to intervene.

Analysis

55 Grounds 1 and 2 of the Notice of appeal raised the issues of matter and standing. Ground 1 is to the effect that the primary judge erred in failing to decide whether the appellants’ claim gave rise to a “matter” within the meaning of Ch III of the Constitution and Ground 2 is to the effect that the primary judge erred in failing to find that the appellants had standing to seek the relief they claimed.

56 Ground 1 is not a complaint about how or on what basis a discretion not to consider the linked questions of standing and matter founding jurisdiction in favour of deciding a case on its merits was exercised. It is a contention to the effect that the primary judge failed to decide an issue which he was required or bound to decide, and indeed that was how the appellants presented the argument to this Court.

57 For his part, the respondent put an argument diametrically opposed to that of the appellants. He contended the primary judge had a discretion not to decide the standing or issue of jurisdiction which he exercised without error and that this Court’s approach should be to consider first issues relating to the merits and if persuaded that there is no error, then it should dismiss the appeal without deciding any issue with respect to standing or jurisdiction. If, and only if, the Court considers that the primary judge erred on the merits, should the Court go on to consider standing or jurisdiction and on that issue (so the respondent contended) the Court should hold that standing or jurisdiction is not made out. The oddity of the possible outcome (ie, the appellants “succeed” on the merits, but fail on standing or jurisdiction) was acknowledged by counsel for the respondent.

58 It is not necessary for this Court to consider the respondent’s argument as outlined above. We have concluded that the primary judge had a discretion not to consider the standing or jurisdiction issue once he had reached the conclusion he had on the merits and there was no error in the way in which he exercised the discretion. As we have reached the same conclusion as his Honour on the merits we do not need to decide the issue of standing or jurisdiction.

59 The question whether a court exercising federal jurisdiction, and in particular a court lower in the judicial hierarchy than the High Court, must always decide the question of jurisdiction even when it is otherwise satisfied that the claim would fail on a non-jurisdictional question has been the subject of learned extra curial debate. In chronological order, the progress of the debate is evident in Lim B, “The case for hypothetical jurisdiction: Postulating jurisdiction in unmeritorious civil proceedings” (2012) 86 ALJ 616; Leeming M Authority to Decide: The Law of Jurisdiction in Australia (The Federation Press, 2012) pp 35–44; Lim B, “Hypothetical jurisdiction: A reply to Justice Mark Leeming” (2013) 87 ALJ 680; Leeming M, “Hypothetical jurisdiction: A rejoinder” (2013) 87 ALJ 685; Leeming M Authority to Decide: The Law of Jurisdiction in Australia (2nd ed, The Federation Press, 2020) pp 37–42.

60 Putting that debate to one side, each of the authorities to which the primary judge referred, Combet, Wilkie and Phong, support the existence of a discretion to determine a proceeding on its merits without considering an issue of standing or jurisdiction. A clear statement of the discretion appears in Wilkie (at [57]):

Notwithstanding statements which have linked the need for standing to the need for a “matter” founding jurisdiction, the High Court has not in practice insisted on determining standing always as a threshold issue but has treated itself as having discretion in an appropriate case to proceed immediately to an examination of the merits. A notable instance of that occurring in a context not dissimilar to the present was Combet v The Commonwealth. There the Full Court, by majority, answered a question reserved for its opinion to the effect that the plaintiffs had not established a basis for any of the relief they sought, whilst stating that it was unnecessary to answer a preceding question reserved which asked whether the plaintiffs or either of them had standing to seek that relief. No argument was put that the approach taken by the majority in Combet was wrong or was unavailable to be taken in the Wilkie proceeding or the AME proceeding.

(Citations omitted.)

61 The discretion was described in the earlier cases (not involving constitutional issues) of Robinson v Western Australian Museum [1977] HCA 46; (1977) 138 CLR 283 at 302 per Gibbs J and Onus v Alcoa of Australia at 38 per Gibbs CJ. In the exercise of federal jurisdiction, the New South Wales Court of Appeal adopted the same approach in Barr (a pseudonym) v DPP (NSW) [2018] NSWCA 47; (2018) 97 NSWLR 246 at [42]–[48], [65]–[66], per Leeming JA, N Adams J agreeing.

62 The primary judge also referred to Ansett Australia Ground Staff Superannuation Fund Pty Ltd v Ansett Australia Ltd [2003] VSCA 117; (2003) 176 FLR 393 (Ansett Superannuation Fund) at 401 in support of a proposition (which he accepted and applied) that in considering whether to examine the merits of a particular question, the Court may take into account the practical need to resolve the issue. The primary judge called this in aid because he considered that there were practical reasons in this case for considering the merits, being a reference to the fact that there is a vigorous public debate on the merits and that both parties wanted a resolution of the debate on the merits (at J [45]–[46]). The decision in Ansett Superannuation Fund does provide support for the proposition that a Court may give weight to a practical need to resolve a present and genuine controversy about a future event which is likely to occur (at [15] per Ormiston JA with whom Callaway JA and Batt JA agreed at [27] and [34] respectively).

63 The appellants submitted that this Court did not have a discretion to decline to address its own jurisdiction and that means whether the appellants had standing and there was a “matter”. They submitted that, insofar as there was authority to the contrary, the authority was best considered a “small pool of inapposite cases” and a pool of cases restricted to a practice permitted, and only permitted, in the High Court. As we have previously indicated, the appellants made a number of submissions in support of this proposition and we turn to consider each of those submissions.

64 First, the appellants submitted that there is clear and unchallenged authority to the effect that the first duty of a Court, including a federal court, is to satisfy itself of its own jurisdiction (Hazeldell at 446 per Isaacs ACJ).

65 Secondly, the appellants relied heavily on the decision of the High Court in AZC20 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2023] HCA 26; (2023) 97 ALJR 674 (AZC20), a case in which the controversy over “some immediate right, duty or liability” evaporated due to circumstances between the trial and the appeal to the Full Court of this Court. The Full Court found that the controversy had been quelled, but went on to consider the merits of the appeals.

66 A majority of the High Court held that the Full Court had erred in considering the merits of the appeals in circumstances where there was no longer a “matter” within Ch III of the Constitution. Chief Justice Kiefel and Justices Gordon and Steward said (at [3]):

That is, the only issue in these appeals is whether the Full Court had jurisdiction to decide the appeals below. All courts have the duty and the authority to consider and decide whether a claim or application brought before the court is within its jurisdiction. As will be seen, the Full Court approached the question of whether it should hear the appeals as a matter of discretion, not jurisdiction. In allowing the appeals and overturning the orders of the primary judge, the Full Court in effect determined it did have jurisdiction and proceeded to exercise judicial power. It is well established that, as a superior court, the orders it made are valid until set aside, even if those orders were made in excess of jurisdiction. Those orders are subject to review and correction by this Court in its appellate jurisdiction under s 73 of the Constitution. As these reasons will explain, the Full Court did not have jurisdiction when it determined the appeals. Its orders should be set aside.

(Citations omitted.)

67 Their Honours said the Full Court erred approaching the question of whether it should hear the appeals as a matter of discretion, not jurisdiction, and in holding that it did have jurisdiction (see also Edelman J at [60]–[65]).

68 The circumstances in ACZ20 are quite different from the present case. In ACZ20, the High Court said that the Full Court erred in holding that it had jurisdiction in circumstances in which at the same time it held that the controversy between the parties had been quelled. That is a very different situation from one where, in a limited number of cases involving particular circumstances, the question is whether those circumstances mean that the Court can exercise a discretion to determine the merits against the moving party and refrain from deciding the issue of standing or jurisdiction. In ACZ20, the Full Court had exercised jurisdiction by allowing the appeal and setting aside the orders of the primary judge in circumstances where, as the High Court held, it did not have jurisdiction, as opposed to in the present case where whether or not the primary judge had, or this Court has, jurisdiction cannot change the result because the claim and the appeal in any event fail on the merits. Furthermore, there was no suggestion in AZC20 that the High Court was reversing the practice identified in relatively recent cases.

69 Thirdly, the appellants relied on the fact that in Wilkie (at [57]), the Court confined its observations to the practice in the High Court. It is true that the observations were made in that context, but equally there is nothing in the observations which exclude their application to other courts.

70 Fourthly, the appellants submitted that so far as cases can be found adverting to the constitutional objections to “hypothetical jurisdiction”, they are against, rather than in favour of, the practice. The first case they referred to is Bray v F Hoffman-La Roche [2003] FCAFC 153; (2003) 130 FCR 317 at [239] where Finkelstein J, writing separately from the other members of the Court although concurring in the result on jurisdiction, stated that “the court must satisfy itself that it has jurisdiction before it proceeds any further with the matter.” Neither his Honour nor the authorities that he cited considered whether that approach, which is doubtless correct as a general proposition, may be departed from in certain confined circumstances including such as the present. Nor did they consider what the appellants refer to as “constitutional objections” to that exception to the general rule.

71 The other case that the appellants referred to is Khatri v Price [1999] FCA 1289; (1999) 95 FCR 287 at [14] where Katz J discussed the “first duty” of an Australian court of limited jurisdiction to satisfy itself that it has the jurisdiction purportedly invoked in the case before it. His Honour explained that that duty has been generally understood as permitting the court concerned to exercise a discretion to postpone determining the question of its jurisdiction until after it has heard the whole case, provided that having done so it then “first” determines the question of jurisdiction. Inasmuch as his Honour observed that the approach of some American federal courts to exercise so-called “hypothetical jurisdiction” was rejected by the US Supreme Court in Steel Co v Citizens for a Better Environment 118 S Ct 1003 (1998) at 1016, his Honour can be understood as saying that that approach is not available in Australia. Nevertheless, Khatri v Price, as a first instance judgment of a single judge, cannot impugn the authority of Phong and Barr, let alone Combet and Wilkie. Also, his Honour did not discuss “constitutional objections” per se.

72 Finally, the appellants submitted that Phong is of very limited assistance because unlike the present case, the question of jurisdiction was partially uncontested and thus unargued, there was an overwhelming case for the discretionary refusal of relief and (so the appellants contend) so far as appears from the judgment, no party opposed the course of proceeding directly to the merits. It may be accepted that there are differences between this case and Phong, but none of the differences identified by the appellants (to the extent they exist) would appear to be relevant to the existence of a discretion as distinct from the manner of its exercise.

73 We do not see any difference in this respect between this Court and the High Court. Although it is true, as submitted by the appellants, that there may be reasons why such a practice is more suited to the High Court, there are also considerations that go the other way. In particular, the position of the High Court at the apex of the judicial hierarchy means that it is only the High Court that is in a position to determine the metes and bounds of its own jurisdiction. In contrast, all other courts are subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the High Court. The result is that it may be regarded as particularly inappropriate for the High Court to make a decision on the merits of a case without deciding jurisdiction, and thus potentially decide a case by dismissing it and thereby make law in the form of precedent when it lacks jurisdiction in the case. See Lim B, “The case for hypothetical jurisdiction: Postulating jurisdiction in unmeritorious civil proceedings” (2012) 86 ALJ 616 p 629. There is no compelling reason why, if the High Court can follow such a practice as the authorities establish that it can, this Court cannot do likewise.

74 The question of standing on the basis of status as electors is a difficult one with potentially wide-ranging ramifications if decided in favour of the appellants. If this Court is to consider the matter by examining whether the primary judge erred in the exercise of his discretion, we do not consider that he did as his Honour took into account relevant matters and the matters usually taken into account. If this Court is to address the matter afresh, we would reach the same conclusion as the primary judge. Although this Court has had the benefit of fuller argument on standing than the primary judge (it seems), the issue requires not only full argument, but also the opportunity for mature reflection. We do not have that opportunity because although we have already announced our decision, we also consider it important that we publish our reasons as quickly as possible and certainly before the day fixed for the majority of electors to vote.

75 The standing issue based on the first appellant’s status as a Senator in the Australian Senate appears in isolation to be easier to resolve. However, we consider that the grounds should not be fragmented and if dealt with, they should be dealt with together.

Grounds 3 and 4

76 The starting point is the statutory text. Paragraph 93(1)(b) and subs (8) of the RMP Act are complementary: a vote is informal if the elector’s intention is not clear; and effect is to be given to a ballot paper according to the voter’s intention, so far as that intention is clear. Although s 24 of the Act directs electors to write “Yes” or “No” in the space provided on the ballot paper, failure to do so does not of itself render the vote informal. Instead, by a combination of s 90(1)(iv) and s 93(8) votes are counted according to whether there is a clear intention to vote in favour or not in favour of the proposed law, and a ballot paper that expresses no clear intention is informal: s 93(1)(b). This construction is clear from the presence of s 93(9) which provides that a voter who writes “Y” is presumed to have intended to approve the proposed law, and that a voter who writes “N” is presumed to have intended not to approve the proposed law.

77 In Kane v McClelland, which we cited above, the High Court considered cognate but differently expressed provisions in the Commonwealth Electoral Act, and their application to preferential voting in a Senate election. Relevantly, s 133(2) of that Act, as then in force, provided:

(2) A ballot-paper shall not be informal for any reason other than the reasons specified in this section but shall be given effect to according to the voter’s intention so far as his intention is clear.

78 The Senate ballot papers directed electors to place consecutive numbers in the squares opposite the candidates’ names, but some ballot papers had not commenced with “1”, but with higher numbers, and others skipped numbers in the sequence. In addressing the application of s 133(2) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act to these ballot papers, Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Kitto, Taylor, Menzies, Windeyer and Owen JJ stated at 527:

Doubtless placing the first and consecutive number in the squares opposite the candidates’ names in the manner directed by s. 123 (1) (a) is to be expected and prima facie obedience to that direction must be looked for, but it is another thing to say that every deviation from its correct application spells informality or indeed that it is the only thing that is capable of sufficiently indicating the voter’s intention. But what is clear is that the intention must be indicated so that it is not left to inference, still less conjecture, that it is expressed or indicated in a way that leaves it indisputable. It is at this point that the petitioner’s case fails. It may be a shrewd guess that the voter who began his numerical sequence with the figures 3, 4, 5 or 6 and maintained it by the requisite number of figures to make 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 or 30, as the case may be, was led to begin the sequence by some error, mistake or trick of the mind which made the lowest figure equivalent to one. Hypotheses may be suggested that led the many voters who fell into some such error to take that course but no one can say with sufficient certainty that the lowest figure in a sequence which does not begin with one necessarily expresses the voter’s first preference. To state or investigate the imaginary hypotheses which may explain such errors is not to the point. It is enough to say that it is an inference and not a clear expression or “indication” of the voter’s intention.

79 The main points arising from the above passage, adapted to the present case, are: (1) writing “Yes” or “No” in the box on the ballot paper is not the only thing that is capable of sufficiently clearly indicating a voter’s intention; (2) the intention must be indicated so that it is not left to inference, still less conjecture; (3) the intention must be expressed in such a way that it is indisputable; (4) a shrewd guess as to voter intention is not a sufficient level of appreciation of a clear intention; and (5) the investigation of different hypotheses to explain what has been written is not to the point. All these points are subject to keeping in focus the text of, relevantly, s 93(8) of the RMP Act, which is concerned with giving effect to what is written on a ballot paper to the extent that the voter’s intention is clear.

80 Commencing first with a single tick written inside the box on the ballot paper, we do not accept the appellants’ submission that by use of a tick in this manner a voter’s intention would be unclear. In particular, we do not accept the two arguments that were put that a tick is reasonably open to an interpretation that the voter either misunderstood what he or she was doing, or that the voter merely “ticked the box” in compliance with the obligation to vote. We prefer the submissions of the respondent that a tick has an accepted symbolic meaning that is inherently affirmative, and that if a tick appears inside the box on the ballot paper in answer to the question posed, it would evidence a clear intention to vote in favour of the proposed law to the degree of satisfaction identified in Kane v McClelland. It is to be borne in mind that what s 93(8) invites is the ascertainment of whether there is a clear intention from what is written on the ballot paper, where the ballot paper should be read and construed as a whole: see, Mitchell v Bailey (No 2) [2008] FCA 692; (2008) 169 FCR 529 at [52] per Tracey J. The scrutiny of ballots is a practical exercise that should not invite strained speculation about the subjective thought processes of the voter, but is concerned with the manifestation of the voter’s intention to the extent that the intention is clear.

81 We have reached our view about the writing of a single tick within the box on the ballot paper that is the subject of this appeal after full consideration, and with the benefit of reviewing the primary judge’s reasons. Sackville J reached the same conclusion in Benwell v Gray, Electoral Commissioner [1999] FCA 1532 at [29] in relation to a challenge to the Electoral Commissioner’s guidelines in a Scrutineer’s Handbook that are extracted at [13] of the judgment and which provided, by way of an illustration, that a voter’s use of a tick inside a box would be a formal “Yes” vote in answer to a question in a referendum. While acknowledging that what Sackville J said on the issue was by way of obiter on an application for an interlocutory injunction that his Honour refused on the ground that the balance of convenience was clearly against the grant of relief, the decision provides support for the correctness of the primary judge’s decision in this case.

82 The fact that voting is compulsory, which is an element of the context emphasised by the appellants, does not assist their argument that the tick could plausibly represent the voter’s intention merely to satisfy the requirement to vote, rather than to express an affirmative response to the question posed. Because a tick is a well-recognised symbol of affirmation, as mentioned, the placing of a tick in the box cannot plausibly be construed as an intention merely to satisfy the minimum requirement of voting without answering the question. Objectively, the tick connotes an affirmative response irrespective of what subjective misapprehension the voter may be labouring under.

83 The point about the diverse electorate does not assist either. There is no reason to expect that Australian electors, irrespective of their generation or their cultural or linguistic background, would not know or understand the meaning conveyed by a tick just as well as they may know or understand the meaning of the word “yes”.

84 In relation to whether a cross manifests a clear intention to vote “not in favour of the proposed law” (see s 90(1)(e)(iv)), we do not accept the appellants’ submissions, and agree with the conclusions of the primary judge. Crosses have been used in a voting context to signify an affirmative response. For example, in South Australia, a tick or cross may be used on a State election ballot paper to indicate a first preference: Electoral Act 1985 (SA), s 76(3). In New South Wales, ballot papers are not informal if a cross or a tick is used instead of a “1”: Electoral Act 2017 (NSW), s 165(3)(d).

85 Re Gleghorn [1980] FCA 19 is a further example of crosses being accepted as indicative of a positive choice in an election context. The case concerned an inquiry under the Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 (Cth) into an election for the position of Assistant Federal Secretary of the Australian Journalists Association. There were two candidates for election and numbering two boxes “1” and “2” was the method of voting directed by the ballot paper, although under the rules of the Association preferential voting was optional and the use of numerals was not mandatory. In issue was a bundle of ballot papers where sole ticks or sole crosses were placed opposite one candidate’s name. Sweeney J held that either a tick or a cross indicated an intention to vote for the candidate:

The question is whether the use of a tick or a cross sufficiently indicates an intention to vote for that candidate. It may be said at once, that a cross is a not unusual way of indicating preference in a ballot. While a tick has, in this community, become a way of indicating approval in filling in forms, such as forms ordering goods or services, insurance proposal forms, passport applications and the like, I do not think any distinction could properly be drawn between ticks and crosses since they are both methods used to show approval or to indicate a view or preference.

86 The appellants submitted that the referendum ballot presents a binary choice to be indicated in a single box in which a cross can logically only represent a choice of one of the alternatives on offer, namely a negative choice. They distinguished everyday examples of the use of a cross to represent an affirmative answer as having more than one box, ie, a selection is made by putting a cross in one of the available boxes rather than in another. On that basis, they submitted that the fact that a cross in some everyday contexts can represent an affirmative selection is inapposite, or irrelevant, to determining what a cross in the box on the referendum ballot can represent.

87 We agree with the primary judge at J [39] that beyond the voting context, a cross may be used to select one of two or more choices and may also indicate a negative choice. It is also a matter of common experience that a cross inside a box is commonly used in daily life to indicate a positive selection or approval in the same way as a tick. The decisive point against the appellants is the significance of a cross inside the box in the context of the written inflexion of the question on the ballot paper, “Do you approve this proposed alteration?” There is real ambiguity as to whether a cross inside the box is a favourable or unfavourable response to this question. This has the consequence that the intention of a voter who completed the ballot paper in this way would not be clear, and would certainly not be clear to the degree required by s 93(8) of the RMP Act construed consistently with Kane v McClelland.

Conclusion

88 For the above reasons, the appeal was dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding eighty-eight (88) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Besanko, Wheelahan and Stewart. |

Associate: