FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Friends of the Gelorup Corridor Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water [2023] FCAFC 139

Table of Corrections | |

22 February 2024 | [19] Replace “required to be permitted under the section (s 136(5)).” With “required or permitted to be under the section (s 136(5)).” |

ORDERS

FRIENDS OF THE GELORUP CORRIDOR INC Appellant | ||

AND: | MINISTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER First Respondent COMMISSIONER FOR MAIN ROADS Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. Subject to order 3, the appellant pay the costs of the respondents as agreed or assessed.

3. If any party wishes to seek a different order as to costs:

(a) that party is to file written submissions of no more than 5 pages in support of the order it seeks by 5 September 2023;

(b) each other party may file written submissions in response of no more than 5 pages by 19 September 2023;

(c) the issue of costs will be dealt with on the papers unless the Court considers that a further oral hearing is necessary; and

(d) the parties have liberty to apply to vary the dates in (a) and (b) above.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JACKSON AND KENNETT JJ:

INTRODUCTION

1 The locality of Gelorup is to the East of the Bussell Highway, a few minutes South of Bunbury in Western Australia. The Commissioner of Main Roads (Main Roads), a State Government entity responsible for constructing and maintaining roads, is currently engaged upon a project known as the Bunbury Outer Ring Road (the Ring Road), which is intended to allow traffic to bypass the urban area around Bunbury. The Ring Road is to connect the Forrest Highway near Australind, to the North of Bunbury, with the Bussell Highway South of Gelorup. Construction of the new road involves clearing areas of native vegetation in Gelorup.

2 On 19 September 2019, Main Roads referred part of the Ring Road project to the first respondent in these proceedings (the Minister) for consideration of whether it was a “controlled action” for the purposes of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (the EPBC Act). The “proposed action” that was referred was the “BORR Southern Section”, which was identified in the referral as “South Western Highway (near Bunbury Airport) to Bussell Highway”. It was described in the following way:

The Proposal includes the construction and operation of approximately 10.5 km of new freeway standard, dual carriageway southwest of South Western Highway to Bussell Highway and a 3 km regional distributor from Bussell Highway at Centenary Road southeast to a grade separated interchange at the western end of Lillydale Road. The Proposal includes associated bridges, interchanges, local road modifications and other infrastructure including, but not limited to, drainage basins, drains, culverts, lighting, noise barriers, fencing, landscaping, road safety barriers and signs. The area being referred by Main Roads covers approximately 300 hectares (ha) and is referred to as the Proposal Area. The Proposal Area connects the northern and central sections of [the Ring Road] (from Forrest Highway) to Bussell Highway.

3 It was noted that around 33 percent of the 300 ha “Proposal Area” was native vegetation. The reason for the referral was that the BORR Southern Section had been assessed as likely to have an impact on members of identified “listed species” and “threatened ecological communities” within the meaning of the EPBC Act. These were as follows.

(a) Banksia Woodlands of the Swan Coastal Plain (Banksia Woodlands) – up to 20.8 ha of this endangered ecological community was to be cleared.

(b) Tuart (Eucalyptus gomphocephala) woodlands and forests of the Swan Coastal Plain (Tuart Woodlands) – the extent of this critically endangered ecological community in the Proposal Area was still to be ascertained, but 28.6 ha of the Proposal Area had been assessed as representative of a similarly described community that was listed under State legislation.

(c) Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus latirostris), Baudin’s Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus baudinii) and Forest Red-tailed Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksia naso) (Cockatoo Species) – the proposed action involved clearing around 80 ha of suitable breeding and foraging habitat for these birds (which were listed as either endangered or vulnerable), including a number of known nesting trees and other trees identified as having suitable nesting hollows.

(d) Western Ringtail Possum – around 80 ha of habitat suitable for this critically endangered species would be lost, affecting the home ranges of 73 individuals that had been located in surveys.

4 On 7 February 2020 a delegate of the Minister decided that the proposed action was subject to certain “controlling provisions” in the EPBC Act and therefore required assessment under that Act. The assessment was to be by the method referred to as “preliminary documentation”.

5 Following the preparation of documentation by Main Roads and various consultative steps that do not need to be described for present purposes, on 17 May 2022 a departmental officer submitted a report to a delegate of the Minister, recommending approval of the proposed action subject to certain conditions (the Recommendation Report). On 29 June 2022 the delegate approved the proposed action (the Approval Decision). On 28 July 2022 a different delegate approved certain “management plans” which conditions of the approval decision required to be submitted.

6 The appellant, a community based, non-profit association run by volunteers, commenced proceedings on 5 August 2022. It sought an order quashing the Approval Decision and relief of an injunctive nature restraining the second respondent (the Commissioner of Main Roads) from undertaking or continuing any action in reliance on that decision. By this time Main Roads had begun work on the BORR Southern Section. An interim injunction restraining the continuation of that work was granted on 5 August 2022. On 9 August, the primary judge refused an application by the appellant to continue the injunction. Work was therefore able to resume.

7 A statement of reasons for the Approval Decision was provided by the delegate on 25 August 2022. (Although that document was furnished after the proceedings were commenced (indeed after an interlocutory judgment canvassing whether certain arguments were viable or not), no point appears to have been taken concerning its admissibility (cf, eg, Nezovic v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (No 2) [2003] FCA 1263; 133 FCR 190 at [46]-[59] (French J)). In his reasons for the judgment presently under appeal, the primary judge expressly treated the document produced on 25 August 2022 as evidence of the delegate’s reasons for making the Approval Decision: Friends of the Gelorup Corridor Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water (No 2) [2022] FCA 1554 at [6].

8 The primary judge heard the substantive application on 14 and 15 December 2022 and made orders on 22 December dismissing the proceeding (reserving liberty to the parties to make written submissions on costs). Those orders are the subject of the appeal.

9 At the time of hearing of the appeal, work on the project was continuing.

THE REGIME OF THE EPBC ACT

Prohibitions on actions having certain impacts without approval

10 Division 1 of Part 3 of the EPBC Act contains a series of prohibitions on undertaking any “action” that has, will have or is likely to have a “significant impact” on certain matters. Each prohibition is subject to identified exceptions, including where there is in force an approval of the action under Part 9 of the EPBC Act for the purposes of the relevant section (or a decision under Part 7 that the section is not a “controlling provision” for the relevant “action”). Related provisions create offences that correspond with the prohibitions and specify defences that correspond with the exceptions. The matters that are protected by these prohibitions are referred to as “matters of national environmental significance” (MNES). They are framed in such a way as to engage heads of Commonwealth legislative power, including the reach given to the external affairs power in s 51(xxix) of the Constitution by particular international conventions.

11 Relevantly for present purposes, s 18 prohibits (without approval) an “action” that will or is likely to have a “significant impact” on the following species and ecological communities (and s 18A creates corresponding offences):

(a) a “listed threatened species” included in the “critically endangered” category (s 18(2)) (which included the Western Ring-Tailed Possum);

(b) a “listed threatened species” included in the “endangered” category (s 18(3)) (which included Barnaby’s Black Cockatoo and Baudin’s Cockatoo);

(c) a “listed threatened species” included in the “vulnerable” category (s 18(4)) (which included the Forest Red-tailed Black Cockatoo);

(d) a “listed threatened ecological community” in the “critically endangered” category (s 18(5)) (which included Tuart Woodlands); and

(e) a “listed threatened ecological community” in the “endangered” category (s 18(6)) (which included Banksia Woodlands).

Controlled actions and assessment

12 Section 67 provides that a proposed “action” is a “controlled action” if, without approval, it would be prohibited by a provision of Part 3. That provision is a “controlling provision” for the action. Section 67A prohibits the taking of a controlled action without approval. A person proposing to take an action that the person thinks may be a controlled action must refer the proposal to the Minister for a decision on that issue (s 68(2)). Whether an action is “controlled” or not is therefore a matter for assessment by the Minister. Under s 75(1), the Minister must decide:

(a) whether the action that is the subject of a proposal referred to the Minister is a controlled action; and

(b) which provisions of Part 3 (if any) are controlling provisions for the action.

13 In making a decision under s 75(1) the Minister is required to consider all adverse impacts on the relevant MNES and not consider any beneficial impacts (s 75(2)). It will also be noted that the only question raised by the definition of “controlled action” in s 67 is whether there are actual or potential significant “impacts” on such a matter. The decision does not require any discretionary balancing of those impacts against other considerations. This occurs in the approval process.

14 The decision made on 7 February 2020 in the present case was a decision under s 75. It had the effect that the proposed action (being the BORR Southern Section) could not be undertaken without obtaining approval under Part 9. The “controlling provisions” specified were ss 18 and 18A.

15 When the Minister decides that a proposed action is a controlled action, s 87 (which is in Part 8) requires a decision to be made as to which of six possible “approaches” is to be used for the assessment of the “relevant impacts of [the] action”. The approach selected in the present case was “assessment on preliminary documentation under Division 4”. No issue arises here concerning the conduct of the assessment process and it is not necessary to summarise the provisions that govern it. It is sufficient to note that the process:

(a) includes a period for public comment, following which the proponent must provide certain documents to the Minister (s 95B); and

(b) culminates in the Secretary preparing and giving to the Minister a “recommendation report relating to the action” which contains recommendations on whether the taking of the action should be approved and, if approved, any conditions that should be imposed (s 95C(1)).

Approval of a proposed action

16 Part 9 of the EPBC Act governs the approval process. Under s 130(1), the Minister must “decide whether or not to approve” the taking of a controlled action for the purposes of each controlling provision (that is, each provision in Part 3 that the action would breach if taken without approval). The decision must be taken within a specified period (s 130(1A)), which for present purposes is within 40 days after the Minister receives the documents referred to in s 95B (s 130(1B)(c)), but can be extended (and was extended in the present case). However, the decision cannot be made until the Minister has received those documents and the Secretary’s recommendation report. This follows from s 133(1) and from s 136(2)(bc), which requires these documents to be taken into account in making the decision.

17 Section 133(1) contains an express power – which is probably at least implicit in s 130(1) – to “approve for the purposes of a controlling provision the taking of the action by a person”. That power can only be exercised after receiving the “assessment documentation” (which, if the action was assessed under Division 4 of Part 4, comprises the documents referred to in the previous paragraph: s 133(8)). Formal requirements for the approval are set out in s 133(2). It must be in writing and specify:

the action;

the person to whom approval is granted;

each provision of Part 3 for which it has effect;

the period for which it has effect; and

any conditions that are attached.

18 Section 136 sets out the matters that must be “considered”, and the “factors to be taken into account” in deciding whether to approve an action and what conditions to attach to an approval. (Additional requirements are imposed on certain categories of decisions by ss 137–140A but they are not relevant here.) Section 136 provides, relevantly, as follows:

136 General considerations

Mandatory considerations

(1) In deciding whether or not to approve the taking of an action, and what conditions to attach to an approval, the Minister must consider the following, so far as they are not inconsistent with any other requirement of this Subdivision:

(a) matters relevant to any matter protected by a provision of Part 3 that the Minister has decided is a controlling provision for the action;

(b) economic and social matters.

Factors to be taken into account

(2) In considering those matters, the Minister must take into account:

(a) the principles of ecologically sustainable development; and

(b) the assessment report (if any) relating to the action; and

…

(bc) if Division 4 of Part 8 (assessment on preliminary documentation) applies to the action:

(i) the documents given to the Minister under subsection 95B(1), or the statement given to the Minister under subsection 95B(3), as the case requires, relating to the action; and

(ii) the recommendation report relating to the action given to the Minister under section 95C; and

…

(e) any other information the Minister has on the relevant impacts of the action …; and

(f) any relevant comments given to the Minister in accordance with an invitation under section 131 or 131A; and

...

Person’s environmental history

(4) In deciding whether or not to approve the taking of an action by a person, and what conditions to attach to an approval, the Minister may consider whether the person is a suitable person to be granted an approval, having regard to:

(a) the person’s history in relation to environmental matters; and

…

Minister not to consider other matters

(5) In deciding whether or not to approve the taking of an action, and what conditions to attach to an approval, the Minister must not consider any matters that the Minister is not required or permitted by this Division to consider.

19 A number of points may be noted at this stage. First, the decision whether to approve an action is to be taken after receiving, and taking into account, the report and other documentation that comes out of the assessment process. Several of the available “approaches” to assessment, including the one employed here, include express provision for interested bodies and members of the public to be informed and make comments about the action. Secondly, in addition to considering that material, the Minister is required to consult other Ministers who have relevant responsibilities (s 131) and empowered to invite comments from the public at large (s 131A). The Minister must take into account any comments received (s 136(2)(f)). None of these sources of information or opinion is limited to the impacts of the proposed action on relevant MNES: that is, they may also properly engage with “economic and social factors” (see eg s 131(2)(a)) (noting that the issue for a recommendation report under s 95C is expressed broadly in terms of whether the action “should be approved”). Thirdly, the Minister may consider any other information in their possession about the “relevant impacts” of the action (s 136(2)(e)). Fourthly, the Minister may consider whether the proponent is a suitable person to be given approval, having regard to the proponent’s history (s 136(4)). Fifthly, the Minister must not “consider” matters other than those that are required or permitted to be under the section (s 136(5)).

20 As to the issues that can be considered, s 136(5) means that the only relevant environmental considerations are the impacts of the proposed action on matters protected by the relevant controlling provisions (s 136(1)(a)). That reflects the fact that the EPBC Act is tied to heads of Commonwealth legislative power and is not a general environmental protection statute. Noting that s 136(5) refers to “matters” (the term used in sub-s (1)), it is not clear whether it also limits the Minister’s sources of information. At least as to environmental impacts, s 136(2)(e) clearly allows the Minister to go beyond the contents of reports and comments that have been received.

21 One of the things that the Minister must “take into account” under s 136(2) is “the principles of ecologically sustainable development” (para (a)). These principles are identified by s 3A and include the principle often referred to as “the precautionary principle”, as follows:

3A Principles of ecologically sustainable development

The following principles are principles of ecologically sustainable development

…

(b) if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation.

…

22 The “precautionary principle” is also introduced by s 391, which sits on its own in Part 16. Sections 391(1) and (2) are as follows:

391 Minister must consider precautionary principle in making decisions

Taking account of precautionary principle

(1) The Minister must take account of the precautionary principle in making a decision listed in the table in subsection (3), to the extent he or she can do so consistently with the other provisions of this Act.

Precautionary principle

(2) The precautionary principle is that lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing a measure to prevent degradation of the environment where there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage.

23 Section 391(3) comprises a table listing 28 different kinds of decisions under the EPBC Act, including a decision under s 133 “whether or not to approve the taking of an action”.

24 The application of the precautionary principle in the present case, and the operation to be given in this context to the expressions “take into account” (s 136(2)) and “take account of” (s 391), need to be addressed in relation to the second ground of appeal considered below.

Conditions

25 The first ground of appeal concerns the imposition of conditions on an approval. Section 134(1A) of the EPBC Act identifies a condition to which all approvals under Part 9 are subject, but which need not be set out here. Sections 134(1) and (2) provide for the kinds of conditions that may be imposed, and s 134(3) provides examples. They are as follows (omitting unnecessary detail):

Generally

(1) The Minister may attach a condition to the approval of the action if he or she is satisfied that the condition is necessary or convenient for:

(a) protecting a matter protected by a provision of Part 3 for which the approval has effect (whether or not the protection is protection from the action); or

(b) repairing or mitigating damage to a matter protected by a provision of Part 3 for which the approval has effect (whether or not the damage has been, will be or is likely to be caused by the action).

Conditions to protect matters from the approved action

(2) The Minister may attach a condition to the approval of the action if he or she is satisfied that the condition is necessary or convenient for:

(a) protecting from the action any matter protected by a provision of Part 3 for which the approval has effect; or

(b) repairing or mitigating damage that may or will be, or has been, caused by the action to any matter protected by a provision of Part 3 for which the approval has effect.

This subsection does not limit subsection (1).

Examples of kinds of conditions that may be attached

(3) The conditions that may be attached to an approval include:

(aa) conditions requiring specified activities to be undertaken for:

(i) protecting a matter protected by a provision of Part 3 for which the approval has effect (whether or not the protection is protection from the action); or

(ii) repairing or mitigating damage to a matter protected by a provision of Part 3 for which the approval has effect (whether or not the damage may or will be, or has been, caused by the action); and

(ab) conditions requiring a specified financial contribution …; and

(a) conditions relating to any security to be given by the holder of the approval …; and

(b) conditions requiring the holder of the approval to insure against any specified liability of the holder to the Commonwealth …; and

…

(d) conditions requiring an environmental audit of the action to be carried out periodically by a person who can be regarded as being independent from any person whose taking of the action is approved; and

…

(f) conditions requiring specified environmental monitoring or testing to be carried out; and

…

This subsection does not limit the kinds of conditions that may be attached to an approval.

26 Sections 134(3A) to (3D) and (4A) make provision in relation to specific types of conditions referred to in s 134(3) and need not be set out. Sections 134(4) and (5) are as follows:

Considerations in deciding on condition

(4) In deciding whether to attach a condition to an approval, the Minister must consider:

(a) any relevant conditions that have been imposed, or the Minister considers are likely to be imposed, under a law of a State or self-governing Territory or another law of the Commonwealth on the taking of the action; and

(aa) information provided by the person proposing to take the action or by the designated proponent of the action; and

(b) the desirability of ensuring as far as practicable that the condition is a cost-effective means for the Commonwealth and a person taking the action to achieve the object of the condition.

…

Validity of decision

(5) A failure to consider information as required by paragraph (4)(aa) does not invalidate a decision about attaching a condition to the approval.

27 It will be recalled that s 136 is expressed to apply in deciding whether to approve the taking of an action and what conditions to apply to an approval. The factors listed in s 136(1) and the reports and other things listed in s 136(2) must therefore be considered, in addition to the considerations in s 134(4), in deciding what conditions should be imposed.

28 Section 136(1) also indicates that the decision as to what conditions should be imposed is at least very closely related to the decision whether approval should be given. Sections 134(1) and (2) reinforce that point: the conditions that may be imposed are those which the Minister thinks are “necessary or convenient” for protecting, or mitigating or repairing damage to, the matters protected by the particular controlling provisions that are in play. At least implicitly, if the Minister is not satisfied that approval of the proposed action as presented is appropriate, they must consider whether an approval subject to identified conditions is appropriate.

29 Conditions attached to an approval are given legal force by Divisions 2 and 3 of Part 9. Section 142 prohibits the contravention of a condition by the person whose taking of an action has been approved, with exposure to a civil penalty as the consequence. Because contravention of a condition also contravenes s 142, there is the potential for the Minister or an “interested person” to apply for and obtain an injunction under s 475 of the EPBC Act to restrain that breach. Sections 142A(1) and (3) and s 142B attach criminal sanctions to some contraventions of conditions.

30 Sections 144(1) and (2A) empower the Minister to suspend the effect of an approval in relation to a specified provision of Part 3 for a specified period in certain circumstances involving contravention of a condition, and ss 145(1) and (2B) provide power to revoke the approval altogether. An approval that has been suspended or revoked can be reinstated by the Minister, on application by the former approval holder, under s 145A.

31 Suspension and revocation are not provided for as automatic consequences of the contravention of a condition imposed under s 134, so that they are not “conditions” in the ordinary legal sense of things upon which the approval is conditioned. First, there must be an exercise of discretion by the Minister. Secondly, the discretion only arises if breach of the condition has led to a significant impact on the matter protected (ss 144(1)(a), 145(1)(a)), the approval would not have been granted without the condition being attached (ss 144(2A)(b)(i), 145(2B)(b)(i)) or the suspension or revocation is reasonably necessary to protect a matter protected by a relevant provision of Part 3 (ss 144(2A)(b)(ii), 145(2B)(b)(ii)).

THE ISSUES IN THE APPEAL

32 Under the heading “grounds of application”, the amended originating application filed in the proceedings below included 62 paragraphs purporting to set out the appellant’s complaints. These were clearly not separate grounds of review. This section of the document was a kind of hybrid between a pleading and written submissions. From the written submissions filed for the final hearing, the primary judge identified the following bases on which the approval decision was challenged (at [8]), each of which was advanced as a ground under either the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (the ADJR Act) or s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth):

(1) the conditions requiring the submission and approval of the management plans are invalid as they impermissibly defer the substantive evaluative task to be undertaken by the Minster’s delegate until after the approval was given;

(2) the conditions requiring the offset strategy and offset management plans are likewise invalid. They also lack any specificity or detail and consequently do not have the necessary certainty to be valid conditions;

(3) the Minister’s delegate did not lawfully consider the precautionary principle as required by the Act;

(4) the Minister’s delegate failed to consider lawfully the Commissioner’s [(Main Roads’)] environmental history or failed to make any necessary inquiry to enable the decision whether to approve to be made on a probative basis or both; and

(5) the decision to approve is inconsistent with a recovery plan for the western ringtail possum.

(Emphasis in original)

33 His Honour rejected each of these claims and consequently dismissed the application.

34 The notice of appeal advanced four grounds, only two of which were pressed. The issues before the Court on appeal are therefore relatively confined, albeit not simple. It is not necessary to summarise the whole of the reasoning of the delegate or the primary judge.

Ground two: conditions relating to the “offset strategy”

How the issue arises

35 Having considered the impacts of the proposed action on the Cockatoo Species and the management actions proposed by Main Roads to minimise those impacts, the Recommendation Report expressed the following conclusions at [60]–[61]:

Acceptability

60. The proposed avoidance and mitigation measures, supported by conditions to regulate the implementation of key measures …, will result in impacts from the proposed action on Black Cockatoos that the Department considers will be acceptable; however, the Department considers that the proposed action will also result in a residual significant impact that requires compensatory measures to be implemented by the proponent in order for the impact to be acceptable ….

Conclusion

61. The Department considers that, provided the proposed avoidance, mitigation and compensatory measures are implemented by the proponent, the impacts of the proposed action on Black Cockatoos are acceptable.

36 The effect of this passage was that, taking into account the avoidance and mitigation measures proposed by Main Roads to reduce the impact of the proposed action on the Cockatoo Species, there remained a “residual significant impact” that needed to be dealt with by “compensatory measures” in order for the impacts to be considered acceptable. Main Roads had proposed to provide specified areas of land by way of “offsets” (ie, areas of habitat that would be protected or improved) in order to compensate for that residual impact; however, the officers who prepared the Recommendation Report did not consider that Main Roads’ offset strategy had been shown to be sufficient. The report noted (at [50]–[51]):

50. The Department’s Post Approvals Section has reviewed the Offset Strategy provided by the proponent. The Department considers the proposed Offset Strategy does not meet the requirements of the EPBC Act Environmental Offsets Policy … in that it:

• Does not meet principles 1, 3, 4 and 5 concerning the delivery of a conservation outcome proportionate to the size and scale of the residual impacts on protected matters, the level of protection that applies to a protected matter, and the risks of the offset not succeeding.

• Does not meet principle 8 in that governance arrangements for the future offset are not clear.

• Does not meeting [sic] principle 9 in that the scientific basis for the proposed offsets is not fully justified.

51. The Department considers that the Offset Strategy will require further development to adequately resolve residual impacts of the type outlined in conservation advices, and does not, in its current form, provide a 100% direct offset for impacts to Black Cockatoos.

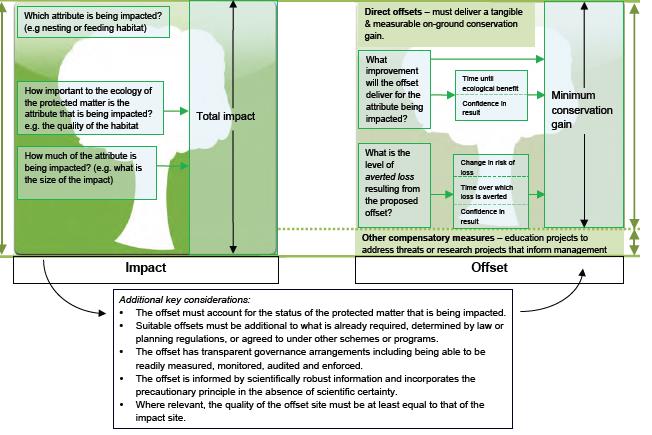

37 The Commonwealth’s “Environmental Offsets Policy” (the Offsets Policy) was in evidence. As the appellant submitted, it is a policy document: it does not erect binding rules and it envisages evaluative judgments based on scientific expertise and experience. However, that said, it provides a relatively detailed framework designed to bring rigour to decision-making about the utility of measures that are offered by proponents and claimed to “offset” environmental damage. It includes a detailed worksheet for calculating the “value” of proposed offsets based on various factors and calls for the inputs to that worksheet to be justified. It is evident that the departmental officers considered that Main Roads’ offset strategy did not have the degree of detail and rigorous justification demanded by the Offsets Policy and therefore could not be accepted as providing sufficient offsets to make the impacts of the proposed action acceptable.

38 Similar reasoning appears in the Recommendation Report in relation to the Western Ringtail Possum (at [92]-[93], [104]-[105]), Tuart Woodlands (at [121]–[124], [130]) and Banksia Woodlands (at [147]–[155], [162]).

39 The delegate agreed with the Department’s observations about Main Roads’ offset strategy in respect of the Cockatoo Species (at [90]–[91]). She then said (at [96]):

In light of the Offset Strategy not providing 100% direct offset for impacts to Black Cockatoos, I agreed to require the proponent to submit a revised Offset Strategy and Offset Management Plans which would identify suitable environmental offsets for Black Cockatoos. This would require the proponent to negotiate the quantum of offset they will provide to meet the Offsets Policy requirements, which includes the security and implementation of a 100% direct environmental offset for Black Cockatoos. The Department has taken this approach with similar Main Roads projects. Noting the proponent’s prior history in securing suitable offsets, I agreed that there was, and is, a high degree of confidence that the final offsets package, once negotiated by the proponent with relevant third parties and the Department, will provide a 100% environmental offset for Black Cockatoos.

40 This paragraph indicates an acceptance by the delegate that a strategy providing 100 percent offsets was needed in order to make the impacts of the proposed action on the Cockatoo Species acceptable, and an expectation that this could be achieved by requiring Main Roads to submit a revised strategy. The delegate therefore accepted the Department’s recommendation that she impose a condition requiring the offset strategy and any offset management plans be approved by the Minister and meet the requirements of the Offsets Policy to the satisfaction of the Minister (at [98]). She concluded that, if approved subject to this and other conditions, the proposed action “will not have an unacceptable impact on Black Cockatoos” (at [99]).

41 The delegate reasoned in the same way, and to the same conclusions, in relation to the Western Ringtail Possum (at [125], [130]–[131]), Banksia Woodlands (at [54]–[56]) and Tuart Woodlands (at [71]–[72]).

42 Consistently with this reasoning, the proposed action was approved for the purposes of ss 18 and 18A of the EPBC Act, subject to conditions. The conditions relevant to this issue are as follows (the offset conditions):

(a) Condition 14 requires the approval holder to submit an offset strategy to the Department within six months of commencing the action. It provides that within nine months of commencement of the action the offset strategy must meet the requirements of the Offsets Policy to the satisfaction of the Minister. It further provides that the approval holder must implement the offset strategy approved by the Minister.

(b) Condition 15 sets out matters that must be identified and described in the offset strategy.

(c) Condition 16 provides that, if the offset strategy has not been submitted for approval within the time allowed by condition 14, “all clearing and/or construction must cease immediately”. In that event, work may restart only after the strategy is submitted or with the Minister’s written agreement.

(d) Condition 17 provides that, if (more than six months after work has commenced) the Minister refuses to approve the offset strategy because they are not satisfied that it meets the requirements of the Offsets Policy, clearing and construction must cease immediately. In that event, work may restart only once the offset strategy is approved or otherwise with the Minister’s written agreement.

The issue

43 The essence of the appellant’s complaint is that conditions 14 to 17 make the approval bad in law, and liable to be set aside, because their effect is to postpone a significant aspect of the decision required by ss 130(1) and 133 to a later time. (A similar complaint is made in relation to conditions 18–21, which require development of “offset management plans”, but it was accepted that this raises the same issue.) In effect (the appellant would say), rather than decide whether it is appropriate to approve the BORR Southern Section, the delegate concluded that it might be appropriate – depending on a later decision – and the action could commence pending that later decision.

44 The way the appellant’s complaint has been put at a more detailed level has varied to some degree over time. This is understandable. Its legal character is, as counsel for the appellant accepted, not easy to articulate.

(a) In the amended originating application, the point occupied 26 paragraphs from [25]-[45]. The key point appears to have been that the conditions relating to offsets allowed destructive work to begin and proceed for several months before the “stop work” conditions became operative (at [31], [40]). Because the offset conditions involved “a critical aspect” of the approval, their effect was (it was said) to “defer actual, effective, lawful approval” of the action to a later time.

(b) The argument developed before the primary judge (and ultimately rejected) was summarised by his Honour as follows (at [39]):

(1) the delegate decided that there were residual significant impacts that required compensatory measures by way of offsets and that the direct offsets proposed by way of compensation by the Commissioner were insufficient;

(2) the conditions did not specify with any precision what was required by way of offsets;

(3) the Offsets Policy was itself a very general document which did not provide adequate direction as to what was required by way of offsets in order to satisfy the policy;

(4) in circumstances where the particular offset measures and requirements for management of the offsets had not been specified in the conditions it could not be said that the decision to approve was informed by an understanding on the part of the delegate of what the offsets would be and therefore the substantive evaluative task (which required a consideration as to whether the offsets were sufficiently compensatory) had not been undertaken; and

(5) the ultimate evaluation and decision to be made by the Minister as to whether the offsets are sufficient will take place outside (and after) the approval process specified in the Act because it will be undertaken when the Minister decides whether to approve the offsets policy and offset management plans of the Commissioner to be submitted under the offset conditions imposed in the present case.

(c) The notice of appeal puts the point in the following way, in the particulars to ground two:

(a) At [35], the learned trial judge correctly identified the delegate’s view of the deficiencies in the Offset Strategy submitted by the proponent.

(b) Contrary to his Honour’s conclusion at [43]-[44], this was not a case where the delegate had any, let alone a precise, understanding of the “improvements” or “adjustments” needed to the proponent’s Offset Strategy.

(c) The thrust of the decision was that the proponent would be required to identify, and then achieve, additional offsets substantially beyond that already proposed. These additional offsets had not until then been contemplated at all by the proponent, or the delegate, let alone with any particularity.

(d) Indeed, in relation to the Banksia Woodlands and Black Cockatoos protected matters, the proponent’s proposed Offset Strategy proposal was specifically rejected as providing adequate compensatory offset, and the proponent was essentially required to revisit the entirety of the Offset Strategy in that respect.

(d) In the appellant’s written submissions, the offset conditions were said to amount to a deferral of the substantive evaluative task required under the EPBC Act, by transferring evaluation of the quality of Main Roads’ proffered offsets into a regime that was not governed by the EPBC Act. The offset conditions were said to be so broad as to mean that the delegate had made a decision “without having formed a view as to precisely what must be done in order for the approval to be given”.

Consideration

45 An argument of a similar kind was put in Buzzacott v Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities [2013] FCAFC 111; 215 FCR 301 (Buzzacott), and rejected except as to one of the conditions of the approval in that case. Buzzacott concerned the approval granted under s 133 of the EPBC Act for a large uranium mine in South Australia, together with a rail line and infrastructure for electricity, water and gas, which was subject to a large number of conditions. As recorded by the Court at [138], the argument had two limbs: that where the content and effect of conditions depended on later determinations, the result was that the purported approval was “uncertain” either in the general law sense or for the purposes of s 5(2)(h) of the ADJR Act; and that, where conditions envisage significant aspects of the proposed action being designed, determined or assessed at a later stage, the result is that the purported approval decision amounts to a provisional or preliminary approval rather than an approval as envisaged in s 133. The argument was put by reference both to particular conditions and to the cumulative effect of a number of those conditions.

46 The Court analysed in some detail the conditions upon which that argument focused. As to the first way the argument was put, the Court determined that the conditions were neither individually nor collectively beyond the power in s 134, and “nor when taken collectively does the range of conditions suggest that the approval granted is invalid for lack of certainty” (at [223]).

47 As to the second way the argument was put, the Court again carefully analysed the conditions that had been put forward as examples of the asserted problem. In relation to two of these the Court held that, although the conditions called for various matters to be the subject of plans submitted for approval at later times, they were not themselves uncertain; they did not indicate a lack of the necessary consideration of impacts in the approval decision; and they did not have the effect that the approval power remained to be exercised (at [230], [264]). The Court also rejected the argument that an error of the kind asserted could arise from the “totality” of the conditions in circumstances where each individual condition did not disclose uncertainty (at [268]).

48 One condition (condition 71) was held to be unauthorised. Condition 71 required development of a detailed infrastructure plan if the proponent wished to construct the rail line or any other infrastructure along an alignment different from that which had been considered in the assessment process. Implicitly, it envisaged that these significant aspects of the proposed action might take a different form (and affect different areas of land) from what had been assessed. There was no limit on the alternative alignments that might be proposed, or (implicitly) the power of the Minister to approve them. Condition 71 was thus not authorised, and “invalid both under the ADJR Act and the general law” (at [253]). However, it was considered to be “not fundamental” to the approval and therefore severable (at [254]–[256]).

49 Northern Inland Council for the Environment Inc v Minister for the Environment [2013] FCA 1419; 218 FCR 491 (NICE) was heard before, but decided after, the judgment of the Full Court in Buzzacott. Cowdroy J did not refer to that judgment, but did refer to the judgment at first instance in Buzzacott. His Honour rejected an argument that a set of conditions requiring offsets were “uncertain”. The gist of the argument appears to have been that it could not be known whether the conditions were capable of being fulfilled; yet clearing of the relevant areas was allowed to begin before the offsets package had been verified (at [38]). It may be observed that that is really a complaint about the approval rather than the conditions, and “uncertainty” may not be the right label.

50 The conditions that were upheld in NICE are set out in the reasons of Cowdroy J at [34]. They required registration of legally binding conservation covenants over land comprising not less than a specified area and verified by independent review as being habitat of a certain quality. Counsel for the Minister submitted that those conditions were actually less certain than the conditions in issue here because, while specific amounts of land were identified, the parameters of the review required to verify their suitability and efficacy as offsets were not fixed. In the present case, on the other hand, compliance with the Offsets Policy will require express consideration, not only of the quality of habitat provided by proposed offset areas, but also of other factors such as the risk of degradation of those areas and the possibility that they might be preserved in any event (in which case they would not truly offset destruction of habitat elsewhere). The actual area ultimately required to achieve offsets in accordance with the Offsets Policy depends on the interplay of these factors. There is thus some force in this submission. However, we are not bound by the decision in NICE and, given the way in which the argument there appears to have been put, it is not of great assistance in resolving the present issue.

51 A somewhat similar issue had been canvassed in Lawyers for Forests Inc v Minister for Environment, Heritage and the Arts [2009] FCA 330; 165 LGERA 203 (Lawyers for Forests). It was argued there that certain conditions on an approval were ultra vires because, among other things, the power in s 134 could not be exercised without knowing with some degree of certainty what the environmental impacts of the proposed action were likely to be. The impugned conditions required collection of data and modelling in relation to the effects of effluent from a proposed pulp mill. How the invalidity of these conditions was said to assist the applicant in having the approval set aside is not explored in the reasons of Tracey J. The argument was rejected, principally because the evidence did not support it (at [22]). The impugned conditions were also upheld on appeal: [2009] FCAFC 114; 178 FCR 385. It was held at [47] of the Full Court’s reasons that the conditions did not have the vice of having been imposed in order to ascertain the environmental effects of the proposed action. That asserted vice may give a hint as to how the attack on the conditions was seen as assisting the appellant. However, again, that question (which is the point of interest here) was not explored.

52 Arguments of the kind raised here point to a tension between what appears (from the text of ss 130 and 133) to be a requirement for a yes or no answer to be given to a proposed action and the scope and complexity of some of the actions requiring approval under the EPBC Act. Attempting to break a large and long term project into smaller components, and seek approval under the EPBC Act for each component as it arises, has obvious problems. The imposition of conditions requiring monitoring, review and the submission of plans for approval – in effect providing for ongoing supervision of the proposed action as it unfolds – is a mechanism by which proponents and decision-makers seek to manage that tension.

53 The proposed action in Buzzacott is an example. It was a large open cut mining operation expected to operate for 40 years. One of the conditions imposed on the approval (discussed at [227]–[230]) required development and implementation of a “mine closure plan”. The particular steps that would be required at the end of the mine’s life to avoid or mitigate ongoing environmental effects were impossible to predict in an assessment and approval process undertaken before mining was even begun. If approval required matters of that kind to be ascertained beforehand and set out in objective, inflexible conditions, approval of a project of that scale would likely be impossible. That is clearly not the intention of the EPBC Act. Counsel for the appellant accepted, therefore, that Part 9 must contain some scope for a proposed action to be approved subject to conditions that allow for decisions to be made on particular issues at later times. Sections 134(3)(d) to (f) envisage conditions of that kind, in that they allow the imposition of requirements for auditing, monitoring and the development of plans (things which would be of limited relevance without additional provisions for the Minister to make decisions in response to the information provided).

54 A criticism made of the conditions in NICE was that the proposed action would be well under way, and impacts on the relevant MNES would have occurred, before it was even known whether the required offsets could be provided. A similar point was made in the amended originating application in this case. If the requirement to stop work under condition 17 or 18 comes into effect, it will only do so after some months of work and may do little or nothing to prevent impacts on the matters sought to be protected. If relevant areas of habitat or threatened ecological communities have already been destroyed or degraded it might be doubtful whether the Minister would refuse to allow work to start again. However, this was not ultimately put as a reason why the approval should be set aside, and it appears to us to be a point going to the merits of the decision rather than its compliance with legal requirements.

55 Three situations can be envisaged in which the indeterminacy of a condition, attached to a purported approval under s 133 of the EPBC Act, could lead to the approval being set aside on judicial review. For reasons which we will explain, none of those situations is present here.

56 First, the condition might be found to be beyond the power conferred by s 134 and inseverable from the approval decision. This may have been the intended end-point of the argument in Lawyers for Forests, referred to above. The appellant’s argument here was not put in this way. Such an argument can be expected to be hard to make out, given the breadth of s 134 and the availability of principles of severance.

57 Secondly, the effect of a condition may be that the scope or nature of the proposed action remains to be fixed at a later time, with the final form of the action to be approved by a decision-making process outside Part 9. To take an extreme example, a road authority might propose to build a freeway through an area that includes threatened ecological communities but provide no specificity about the proposed route. In practice, that would no doubt be dealt with by the proponent being urged to refine the proposal before any decision was made under s 75. In our view it could not properly be dealt with by granting approval under s 133, with a condition requiring the detailed route to be submitted later for approval by the Minister. A decision of that kind would provide no clarity as to what action was able to be undertaken without breaching s 18 of the EPBC Act.

58 Although members of the Court in Triabunna Investments Pty Ltd v Minister for Environment and Energy [2019] FCAFC 60; 270 FCR 267 noted that the scheme of the EPBC Act permits flexibility, including modification of a proposed action between referral and approval (at [43] (Flick J)) and some scope for judgment in how a “proposed action” is identified at the s 75 stage (at [191]–[193] (Mortimer J)), the proposed action must nevertheless have some degree of stability, as it is the subject of a sequence of decisions and assessments that the EPBC Act envisages as applying to the same subject-matter. At least when it is approved, the “action” needs to be identifiable because its boundaries are the boundaries of an exemption from one or more statutory prohibitions in Part 3.

59 Condition 71 in Buzzacott had the vice of rendering the scope of the proposed action unknowable, but the Court held that it could be severed and leave the approval standing. It appears to us that, if a condition of that kind could not be severed (which may well be the case if the condition is needed to define what is being approved), it would have the potential to result in a purported decision that did not perform the function of a decision under s 130(1). The decision would fail to perform the decisional function in that it would neither approve nor refuse to approve the proposed action, but instead purport to create a regime under which some amended version of the proposed action would be considered for approval later. It would encounter a problem of the kind identified in King Gee Clothing Co Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1945) 71 CLR 184 at 196-197 (Dixon J); and it would be inconsistent with the scheme of the EPBC Act, because the process leading to the later (determinative) decision would not be governed by Parts 8 and 9. A significant aspect of the appellant’s submissions was that the offset conditions in the present case resulted in a decision that had these flaws.

60 Clearly, in the light of what we have said above, there is some scope for the imposition of conditions that call for further assessment and approval of management plans or strategies for steps to be taken in connection with a proposed action. The appellant expressly accepted as much.

61 The circumstances in which a condition would be found to go too far in that respect need not be addressed further in this case, because the offset conditions do not create any indeterminacy in the scope of the “action” that is the subject of the approval decision. They do not countenance any alteration or revision of that action. Instead, they deal with compensatory measures that, the delegate has determined, need to occur in order to make the environmental impacts of the action acceptable. There is therefore no indeterminacy as to the scope of what has been approved, and no deferral of assessment of the proposed action.

62 Thirdly, there may be cases where the terms of a condition reveal irrationality in the reasoning leading to the decision. An argument along these lines can also be discerned in the appellant’s submissions in the appeal. (It is another possible destination of the argument in Lawyers for Forests, referred to above, had it been accepted.)

63 Sections 130, 133 and 134 of the EPBC Act, read together, impose a duty to make a decision of a particular kind. The decision must be either to approve the proposed action, approve it with conditions, or refuse to approve it. The choice between those three outcomes (and any decision about what conditions to impose) is, as counsel for the Minister submitted, discretionary. There is no specified criterion as to which the decision-maker must be satisfied. Rather, there is a requirement (imposed by s 136(1)) to consider two broadly-expressed and incommensurable sets of factors: the impacts of the proposed action on MNES; and “economic and social matters”. The decision is in that sense a political one, and power is therefore reposed in a Minister (although it can be delegated).

64 However, the prominence of impacts on MNES in s 136(1) and in the statutory scheme more generally means, in our view, that a necessary step in the decision-making process is an assessment of whether those impacts are acceptable in the light of the benefits that the proposed action may bring. If the decision-maker considers that the impacts are not acceptable, the next question for the decision-maker must be whether conditions can be devised that will result in the impacts being acceptable (by limiting or reducing those impacts or, possibly, by bringing about a benefit that offsets them) and what those conditions are. The parts of the delegate’s reasons set out above demonstrate that she was fundamentally concerned with whether the impacts of the proposed action were, or could be made, “acceptable”.

65 Because the power must be exercised according to the “rules of reason and justice”, each step in the decision-maker’s resolution of those questions needs to have a rational basis. Specifically, if it is the imposition of a condition that makes the difference between the impacts of the action being unacceptable and those impacts being acceptable, the delegate must have an understanding of what the condition will achieve and a rational basis for that understanding. Where the effect of the condition is indeterminate, because it leaves significant issues to be decided later, a consequence may be that there is no rational basis for concluding that the imposition of the condition will make the impacts of the action acceptable, and thus no proper foundation for concluding that approval is therefore appropriate. In such a case, the decision might well be found to be legally unreasonable in the sense discussed in Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v Li [2013] HCA 18; 249 CLR 332 at [64]-[72] (Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ) (and see Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v Stretton [2016] FCAFC 11; 237 FCR 1 at [2]-[13] (Allsop CJ), [50]-[62] (Griffiths J)).

66 In contrast to the second situation discussed above, whether an error of this kind has occurred depends on the decision-maker’s reasoning process rather than the terms and effect of the decision itself. The evidence of that process, including in this case the statement of reasons, therefore needs to be addressed.

67 The delegate’s reasoning, in relation to each of the species and ecological communities identified as being potentially affected, has been described at [37]-[39] above. It involves the following steps.

(a) The impacts of the BORR Southern Section are not acceptable unless conditions are imposed to avoid, mitigate or offset them.

(b) With conditions imposed so as to avoid or mitigate those impacts to the extent possible, the impacts remain unacceptable. The impacts would, however, be acceptable if sufficient offsets were provided.

(c) The offset strategy proposed by Main Roads is not sufficient.

(d) However, it is possible to be confident that Main Roads will develop and implement a sufficient offset strategy (measured by reference to the Offsets Policy) if a condition requires that to be done.

(e) Further conditions expressly requiring work to stop if a revised offset plan is not provided, or is not in an acceptable form, within specific time frames will help to ensure that a sufficient offset strategy is developed and implemented.

68 In our view, that process of reasoning is not irrational. It is true that the delegate did not know what the final offset strategy would look like. The discussion in the statement of reasons and the Recommendation Report do not allow any finding to be made about how much further work by Main Roads was thought to be needed and how much, if any, additional land it needed to offer. However, the delegate did have:

(a) a relatively detailed policy document by which the sufficiency of a revised offset plan could be measured;

(b) knowledge of a history of dealings with the particular proponent; and

(c) on the basis of these things, a “high degree of confidence” that a final offsets package would be arrived at which would “provide a 100% environmental offset”.

69 The flexibility provided for in the offset conditions therefore did not deprive the critical conclusion of the delegate – that, with those conditions in place, sufficient offsets would be achieved – of a rational foundation.

70 For these reasons, ground two is rejected.

Ground three: the precautionary principle

The issue

71 This ground takes issue with the primary judge’s rejection of what was described as claim three in the summary set out above: that the delegate did not consider the precautionary principle in the manner required by the EPBC Act.

72 The argument below and in this Court focused on the force that is given to the precautionary principle by s 391 of the EPBC Act. It must be borne in mind, however, that the principle is also brought to bear on an approval decision by s 136(2)(a) as part of the principles of sustainable development.

73 The delegate’s statement of reasons refers to the precautionary principle at two points:

(a) Clearing associated with the BORR Southern Section was estimated to affect between 49 and 72 individual Western Ringtail Possums. Main Roads expressed a belief that displaced possums were likely to move to other locations so that there would be no mortality. However, the delegate accepted departmental advice that an unknown proportion of the displaced possums was likely to “suffer mortality” (at [112]). The delegate went on to say that, in the light of the effects of clearing and the “lack of scientific certainty as to the effect on Western Ringtail Possum mortality”, “I accepted the Department’s advice that the precautionary principle applied and I took it into account in my decision, including by imposing the conditions discussed further below” (at [113]).

(b) Under a later heading “Other Relevant Matters”, the delegate said (at [156]):

In deciding whether or not to approve the taking of the proposed action, I took into account (amongst other matters) the principles of ecologically sustainable development as required under section 136(2)(a) of the EPBC Act, and the precautionary principle as required under section 391 of the EPBC Act. In particular, as discussed above, I accepted the Department’s recommendation that the principle applied to the Western Ringtail Possum.

74 The primary judge described the submission advanced below in this way (at [48]):

The claim made by [the appellant] concerning the precautionary principle was to the effect that the delegate only considered the principle when addressing the threat to the western ringtail possum if the proposed action was approved. This was said to be deficient because the [EPBC Act] required the precautionary principle to be considered as a factor that applied to each part of the delegate’s evaluation and that regard to the reasons demonstrated that there had been no such consideration by the delegate

75 His Honour considered the construction of s 391 of the EPBC Act and the case law on the precautionary principle in some detail at [52]-[64]. At [61] his Honour said:

Importantly for present purposes, the precautionary principle does not operate as a factor that will itself affect the outcome. Rather, it applies where there is a basis to conclude that there is a threat of serious or irreversible environmental damage and scientific uncertainty as to the nature and scope of the threat. In order for it to operate there must be material to be evaluated. The principle does not provide a basis for a decision in and of itself. It is properly seen as being directed to the quality of proof that is needed concerning a risk of environmental damage that might bear upon a particular decision. It operates in a similar manner to the direction to a jury to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt. It sets a standard as to the level of certainty on which a decision may be based.

76 Later, his Honour said (at [70]-[71]):

… what is said is that irrespective of the nature of the findings made by the delegate as to the likely risk of impact, the delegate was required to consider the application of the precautionary principle. The contention advanced was to the effect that the reasons as to the impact on each and every community and species under consideration should have included a consideration of the precautionary principle. However, for reasons that have been given, it was a matter for the delegate to consider whether there was the requisite threat and only if there was such a threat was the delegate to take account of the precautionary principle and then only by putting to one side the lack of full scientific certainty as a reason why the proposed action should not be approved.

As has been noted, s 391 operated as an evidentiary principle not as an articulation of a substantive mater to which the decision-maker was required to have regard. The precautionary principle itself could not be a reason why a decision might be made to refuse to give an approval. Rather, the precautionary principle could only be the basis upon which material that demonstrates the requisite threat may be used as a reason for a decision made in order to prevent degradation to the environment even though there is a lack of full scientific certainty that the damage is likely to occur.

77 Turning to the delegate’s reasons in the present case, his Honour said (at [76]):

Having regard to the form of the reasons and the manner in which they identified and engaged with serious threats I am unable to infer (as I was invited to by [the appellant]) that the delegate overlooked the possible application of the precautionary principle to aspects of the reasons that concerned impacts on species other than the western ringtail possum. Rather, the reasons as a whole indicate a considered view by the delegate as to where the precautionary principle might be appropriately applied and the application of the principle in that case where there was identified uncertainty as to the likely impact. In all other respects, the delegate approached the matter on the basis that the impacts had been established. No issue arose as to the certainty with which that conclusion may be reached, particularly no issue as to whether by reason of a lack of full scientific certainty the refusal of the approval should be ‘postponed’ (to use the language of the principle as stated in s 391(2)). Therefore, there was no occasion for any lack of scientific certainty to be used as a reason for allowing the approval in accordance with the precautionary principle

78 On appeal, the appellant drew attention to what was said to be a difference between his Honour’s approach and that adopted by Moshinsky J in Bob Brown Foundation Inc v Minister for the Environment (No 2) [2022] FCA 873 (Bob Brown Foundation) and submitted that the approach of Moshinsky J was to be preferred. What was said to follow was that there is a requirement to “consider” the precautionary principle in relation to each protected matter when making a decision under s 130. Thus, as to each issue of the four protected matters, the delegate was required to consider whether there was a relevant “threat” that brought the precautionary principle into play. It was submitted that the delegate had misunderstood the effect of the precautionary principle and that what purported to be an application of that principle to the position of the Western Ringtail Possum was, in fact, no more than the taking of a conservative approach to assessing the likelihood of an adverse environmental impact.

79 Bob Brown Foundation concerned a decision, purportedly made under s 75 of the EPBC Act, that proposed works preparatory to constructing a tailings dam in western Tasmania did not constitute a controlled action. That decision was reached on the express basis that the works would be carried out in a “particular manner” that involved measures to protect several identified species and one threatened ecological community. A decision reached on that basis needs to specify the “particular manner” (s 77A), which then has legal consequences as to how the relevant action can be carried out. The decision did not specify any measures in relation to another threatened species (the Masked Owl), even though material submitted by the proponent suggested possible impacts on that species. The decision was challenged on several grounds, including failure to comply with s 391 (which is expressed to apply to decisions under s 75).

80 At [19]-[32] Moshinsky J discussed the scope of the precautionary principle by reference to earlier authority – in particular, the two “preconditions” to its application (a “threat of serious or irreversible environmental damage” and “scientific uncertainty”) and their interaction. At [33] his Honour came to the requirement in s 391(1) to “take account” of the principle in making decisions of the relevant kind, and said (omitting citations):

In my view, the requirement to “take account” in s 391(1) is interchangeable with a requirement that a decision-maker “consider” a particular matter …. This requires the Minister to consider, at least, whether the first condition precedent is satisfied. The decision-maker must bring an active intellectual process to this matter …. If the first condition precedent is not satisfied, it is not necessary to consider the second condition precedent. If the first condition precedent is satisfied, it will be necessary to consider whether the second condition precedent is satisfied. If both conditions precedent are satisfied, this triggers the application of the precautionary principle and the concomitant need to take precautionary measures …. As already noted, however, the obligation to take account of the precautionary principle in making a decision listed in the table in s 391(3) is qualified by the words “to the extent he or she can do so consistently with the other provisions of this Act” in s 391(1).

81 Moshinsky J held that the delegate was required to consider, at least, whether the first condition precedent to the application of the principle was met, and to bring an active intellectual process to that matter. He found that the delegate had not done this, on the basis that the reasons did not “expressly refer” to that condition precedent in connection with the Masked Owl or make a finding in terms that corresponded with it (at [49]). His Honour also observed (at [52]) that it was difficult to accept that the delegate had in fact applied the precautionary principle in circumstances where consultants engaged by the proponent had recommended measures to protect the Masked Owl, but the delegate did not require the proposed action to be undertaken in accordance with these measures.

82 The primary judge, at [69], discerned some tension between the reasoning of Moshinsky J that led to his Honour’s conclusion at [49] of Bob Brown Foundation and reasoning of the Full Court in Queensland v Humane Society International (Australia) Inc [2019] FCAFC 163; 272 FCR 310 at [120]-[121]. Drawing on that reasoning, his Honour observed that it is not the precautionary principle itself that gives rise to an obligation to consider whether there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage. Rather, the principle comes into play where such threats exist, so as to require a decision-maker in such circumstances not to use a lack of scientific certainty as a reason not to take a measure to prevent that damage. That observation is correct. However, it does not deal with the content of the obligation under s 391 of the EPBC Act to “take account of” the principle. On that question, there is in our view a clear tension between the analysis of the primary judge at [52]-[64] and the reasoning of Moshinsky J.

Consideration

83 Without wishing to suggest that the decision in Bob Brown Foundation was wrong, we broadly agree with the approach of the primary judge to the question of how and in what circumstances the precautionary principle comes into play.

84 The formulation of the precautionary principle in ss 3A and 391 of the EPBC Act has been set out above. It is similar to the way the principle was formulated in the legislation applied in Telstra Corporation Ltd v Hornsby Shire Council [2006] NSWLEC 133; 67 NSWLR 256, where Preston CJ surveyed the background and operation of the principle, although (as Moshinsky J noted in Bob Brown Foundation) the two “conditions precedent” are set out in a different order.

85 It is noteworthy that the principle, as there expressed, applies to the resolution of a question concerning “postponing a measure to prevent degradation of the environment”. The Minister or a delegate deciding whether or not to approve a proposed action under s 133 (and what conditions if any to impose) does not face any question that fits within that description. Approval of an action that may have significant impacts on MNES cannot be described as “a measure to prevent degradation of the environment”. The controlling provisions in Part 3 do that work. Refusal of approval therefore does not “postpone” any measure; it leaves relevant protections in place. Conversely, the effect of an approval granted under s 133 is to relax one or more of the prohibitions in Part 3 and thereby allow some degree of adverse impact. Additionally, s 136 does not permit consideration of “degradation of the environment” as a general topic: the only environmental impacts to be considered are matters relevant to the matter protected by a controlling provision: s 136(1)(a), (5).

86 The imposition of conditions on an approval might be said to constitute a measure to prevent (or at least limit) “degradation of the environment”. However, a condition has that character only in the sense that it limits the effect to which an approval decision relaxes prohibitions in Part 3 (or offsets the consequences of such a relaxation). In substance, the grant of approval and the imposition of conditions form part of the same decision (which, as outlined in the previous paragraph, is not in any ordinary sense a decision about imposing or postponing a measure to prevent degradation). Additionally, a decision not to impose a condition would not amount to “postponing” a measure to prevent environmental degradation in any ordinary sense of that term, because conditions can only be imposed (or not) at the time of the approval decision. According to its terms, therefore, the precautionary principle as expressed in the EPBC Act has no direct application to a decision of the kind in issue here.

87 These observations call for some explanation of why the Parliament took the trouble to include s 133 in the list of provisions to which s 391 applies. That inclusion is misconceived if s 391 is concerned with the direct application of the precautionary principle. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill for the EPBC Act (which includes s 391 in relevantly identical terms to its current form) does not assist in this regard.

88 The explanation, in our view, lies in what is otherwise a rather curious form of words, requiring decision-makers to “take into account” the principles of ecologically sustainable development (s 136(2)(a)) and to “take account of” the precautionary principle (s 391). That form of words is curious because the principle is, as the primary judge explained in the passages set out at [75]-[76] above, with which we agree, a decisional rule concerning how evidence is to be acted upon rather than a relevant consideration in the sense of a factor to be given more or less weight in an evaluative or discretionary decision. A requirement expressed as a duty merely to “take into account” a rule of this kind is at first blush surprising because it seems unlikely that, in a decision to which the precautionary principle actually does apply, the Parliament intended to give the decision-maker a choice as to whether or not, or to what extent, to apply it.

89 The observation in Bob Brown Foundation at [33] that “take account” and “consider” are essentially interchangeable expressions is correct as far as it goes. However, the content of both expressions varies according to what it is that must be considered or taken account of. There is an important difference between the duty to take into account (or consider) relevant considerations (which requires those considerations to be weighed against other factors as part of a reasoning process) and the duty to consider (or take into account), for example, representations made by an affected person (which requires understanding of those representations and consideration of whether the points they make are relevant): see, eg, ECE21 v Minister for Home Affairs [2023] FCAFC 52 at [7]–[8] (the Court); Viane v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] FCAFC 116; 263 FCR 531 at [67]-[70] (Colvin J).

90 In s 136 of the EPBC Act, sub-s (1) requires the Minister to “consider” two sets of issues or factors (impacts on MNES and “economic and social matters”). Subsection (2) then requires the Minister, in performing that task, to “take into account” a range of things. Paragraphs (b)–(d) and (f)–(g) of sub-s (2) specify reports, notices and comments received under various provisions of the EPBC Act, while para (e) refers to other “information” that the Minister has. These are all sources of information or statements of opinion on matters that are probably (although not necessarily) relevant to the issues or factors with which the Minister has to grapple under s 136(1). The principles of ecologically sustainable development (which include the precautionary principle), referred to in s 136(2)(a), are the subject of the same command (“take into account”); however, they are overarching rules or principles for decision-making rather than sources of information or expressions of opinion. Section 391(1) uses a third formulation – “take account of” – which in most contexts is also interchangeable with “consider”. Like s 136(2)(a), what it directs attention to is a rule or principle of decision-making, rather than an issue or factor (cf s 136(1)) or a source of information or expression of somebody’s opinion (cf s 136(2)(b)-(g)). It requires a different kind of engagement from those provisions.

91 The effect of a statutory requirement to “apply” the precautionary principle would be relatively easily understood, at least where the decision is one to which the principle applies according to its terms. Reasoning which accepted the existence of a threat of serious or irreversible harm, but held back from imposing a measure to prevent that harm on the ground of a lack of scientific certainty, would infringe the requirement. The resulting decision would at least ordinarily be liable to be set aside. In a case where the principle according to its terms does no work (including where there is no proposed “measure to prevent degradation of the environment” under consideration), a requirement to “apply” the principle would, it seems, also have no work to do.