FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Stuart v State of South Australia [2023] FCAFC 131

ORDERS

AARON STUART and others named in the Schedule of Parties A Appellant | ||

AND: | STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA and others named in the Schedule of Parties A Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The following orders are set aside:

(a) paragraphs 2 and 3 of the orders made on 21 December 2021 in SAD 38/2013; and

(b) the orders and determination made on 23 December 2021 in SAD78/2013 and SAD220/2018.

2. In lieu thereof there be the following orders:

(a) the originating application in SAD78/2013 is dismissed.

(b) the originating application in SAD220/2018 is dismissed.

3. The appeal is otherwise dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

SAD 17 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | STATE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Appellant | |

AND: | DEAN AH CHEE and others named in the Schedule of Parties B Respondent | |

order made by: | RANGIAH, CHARLESWORTH AND O'BRYAN JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 August 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The following orders are set aside:

(a) paragraphs 2 and 3 of the orders made on 21 December 2021 in SAD 38/2013; and

(b) the orders and determination made on 23 December 2021 in SAD78/2013 and SAD220/2018.

3. In lieu thereof there be the following orders:

(a) the originating application in SAD78/2013 is dismissed.

(b) the originating application in SAD220/2018 is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RANGIAH AND CHARLESWORTH JJ

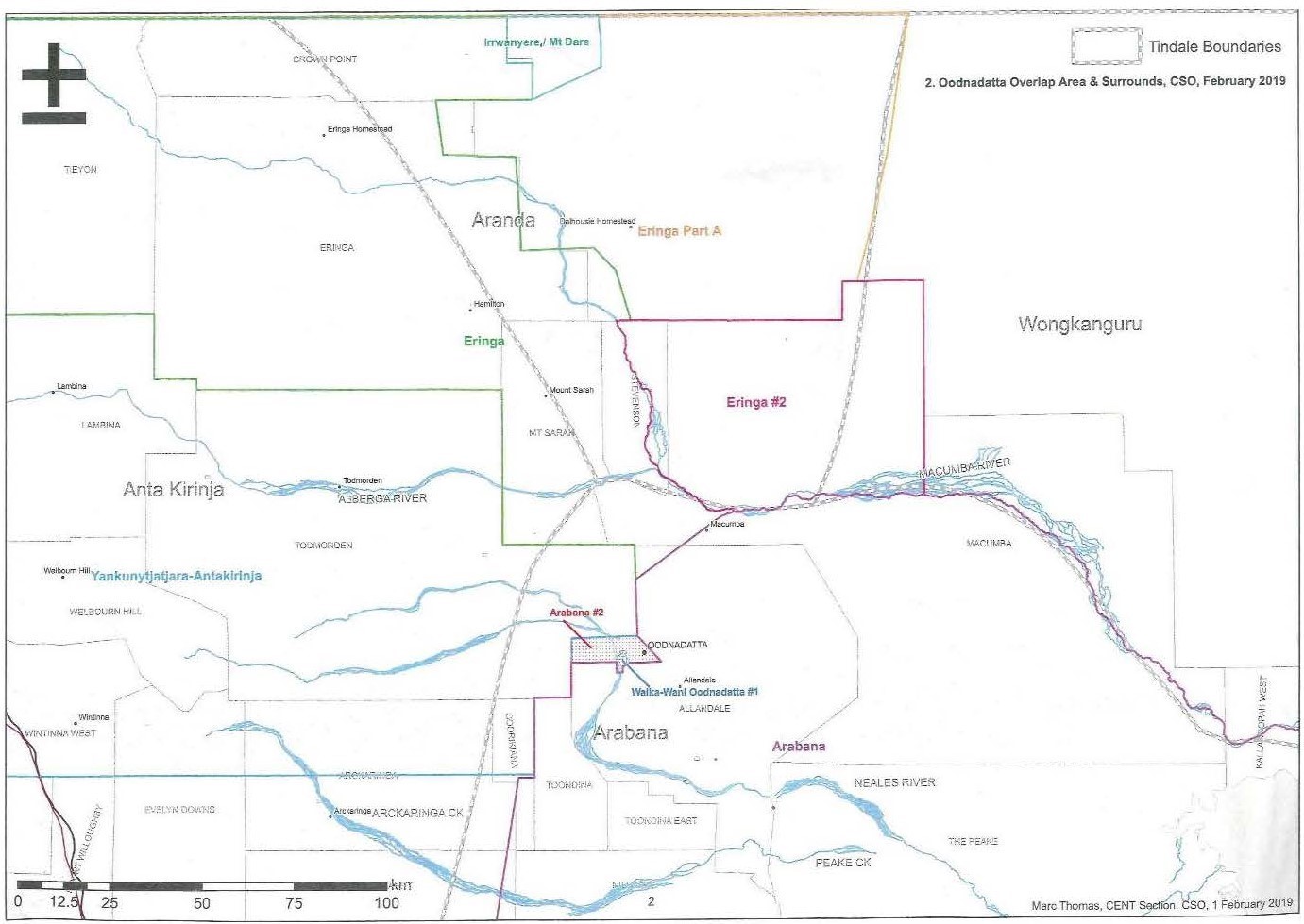

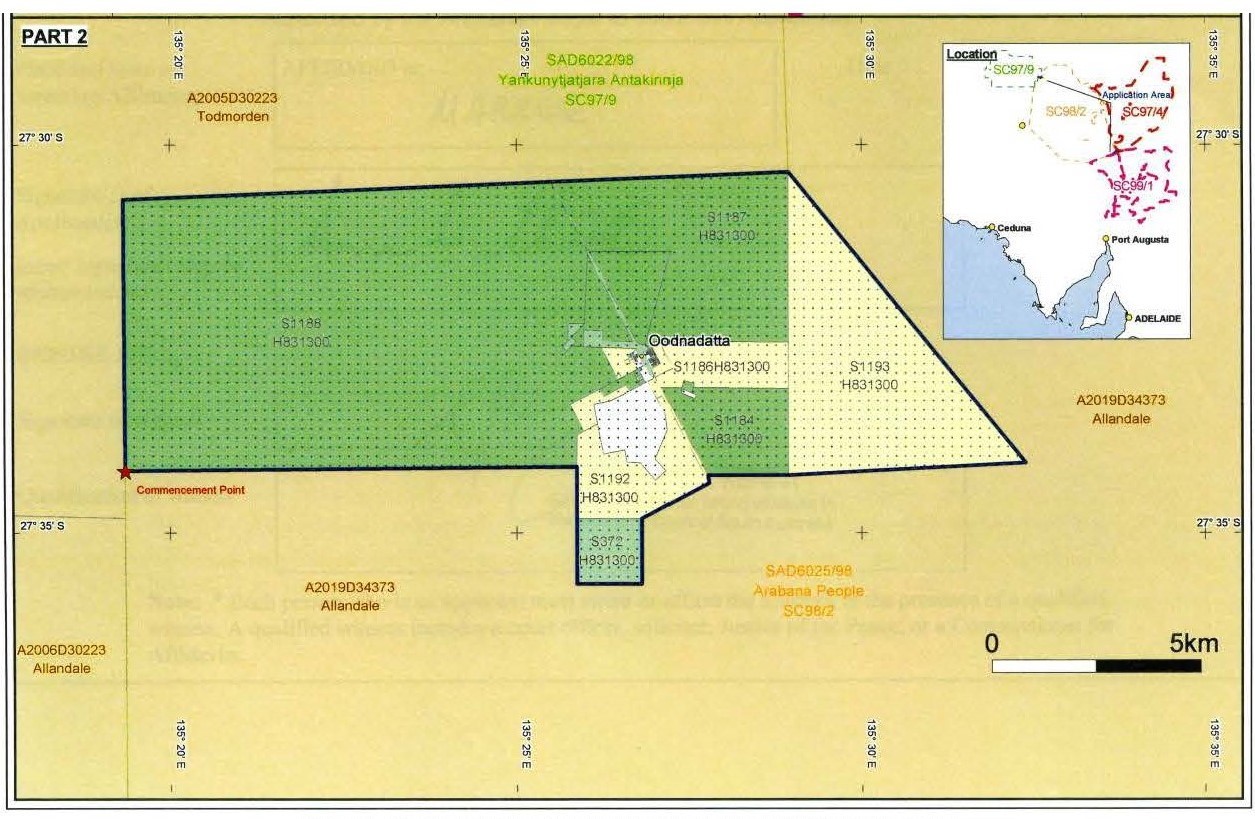

1 The appellants in these two appeals challenge orders resolving overlapping claims for determinations of native title. The claims relate to an area in the vicinity of the township of Oodnadatta in South Australia (Overlap Area).

2 The Overlap Area comprises about 150km2 of land situated about 160km south of the Northern Territory border.

3 The primary judge had before him three applications for a determination of native title, each made under s 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NT Act).

4 Action SAD 38/2013 was made on behalf of the Arabana people in respect of an area divided into parts named Part 1 and Part 2. The boundaries of Part 2 coincide with the boundaries of the Overlap Area. A determination of native title was previously made in respect of Part 1 in Stuart v South Australia (No 3) [2021] FCA 230. The primary judge referred to the claim relating to the Part 2 area as the Arabana Claim and we will do the same.

5 Actions SAD 78/2013 and SAD 220/2018 were two applications filed five years apart on behalf the Walka Wani people, a composite group including Lower Southern Arrernte people (LSA) and Yankunytjatjara/Antakirinja people (also known as Luritja), (YA). Those two actions may be referred to together as the Walka Wani Claim. The land and waters covered by them coincide with the boundaries of the Overlap Area.

6 In these reasons the Arabana people and the Walka Wani people may at times be referred to simply as the Arabana and the Walka Wani.

7 The primary judge made orders pursuant to s 67 of the NT Act providing for the Arabana Claim and the Walka Wani Claim to be heard and determined in the same proceeding.

8 By an order made on 21 December 2021 the primary judge dismissed the Arabana Claim and made further orders requiring the parties to the Walka Wani Claim to confer with a view to providing the Court with minutes of order to give effect to reasons his Honour published on that day: Stuart v State of South Australia (Oodnadatta Common Overlap Proceeding) (No 4) [2021] FCA 1620.

9 On 23 December 2021, the primary judge made a determination of native title in SAD 78/2013 and SAD 220/2018 in favour of the Walka Wani (Determination).

10 The Arabana appeal from the orders dismissing the Arabana Claim and from the Determination made in favour of the Walka Wani (Arabana Appeal).

11 The State of South Australia appeals only from the Determination (State Appeal). It does not seek to disturb the order dismissing the Arabana Claim and actively opposes the Arabana Appeal.

12 The Walka Wani defended both appeals.

13 For the reasons given below we have concluded that the grounds of appeal impugning the order dismissing the Arabana Claim should be rejected, and that the grounds impugning the Determination should be upheld. It follows from those conclusions that the State Appeal will succeed, and the Arabana Appeal will succeed only in part. The orders giving effect to the Determination will be set aside.

APPEAL FROM DISMISSAL OF THE ARABANA CLAIM

14 A determination of native title is a determination as to whether or not native title exists in a particular area and (relevantly) who the persons or each group of persons holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are, and the nature and extent of those rights in relation to the subject area: NT Act, s 225.

15 Section 223 of the NT Act defines the expression “native title” and “native title rights and interests” as follows:

Common law rights and interests

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

Hunting, gathering and fishing covered

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), rights and interests in that subsection includes hunting, gathering, or fishing, rights and interests.

16 The rights and interests to which s 223 of the NT Act refers are rights and interests having their origin in Aboriginal law and custom existing at the time of sovereignty. The reference in s 223(1)(a) and (b) to the word “traditional” must be understood accordingly. As the High Court explained in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422, (at [46]) the word “traditional”:

… conveys an understanding of the age of the traditions: the origins of the content of the law or custom concerned are to be found in the normative rules of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies that existed before the assertion of sovereignty by the British Crown. It is only those normative rules that are ‘traditional’ laws and customs.

17 Accordingly, the rights and interests that survived the assertion of sovereignty and acquisition of radical title by the British Crown are rights and interests in relation to land and waters owing their existence to the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Aboriginal people concerned: Yorta Yorta (at [37]). The High Court continued (at [50]):

To speak of rights and interests possessed under an identified body of laws and customs is, therefore, to speak of rights and interests that are the creatures of the laws and customs of a particular society that exists as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs. And if the society out of which the body of laws and customs arises ceases to exist as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs, those laws and customs cease to have continued existence and vitality. Their content may be known but if there is no society which acknowledges and observes them, it ceases to be useful, even meaningful, to speak of them as a body of laws and customs acknowledged and observed, or productive of existing rights or interests, whether in relation to land or waters or otherwise.

18 The High Court emphasised (at [33] – [35]) that all elements in s 223(1)(a), (b) and (c) must be given effect.

19 The “connection” referred to in s 223(1)(b) is one having its source in traditional laws and customs. As the Full Court observed in Bodney v Bennell (2008) 167 FCR 84, the concept of connection is multifaceted, the cases emphasising different aspects of it in different factual contexts (at [164]).

The Arabana case at trial

20 Questions of extinguishment aside, the onus was upon the Arabana to establish their claim to the civil standard of proof: Lake Torrens Overlap Proceedings (No 3) [2016] FCA 899, Mansfield J (at [92] – [98]).

21 By their originating application, the Arabana alleged that the present day claimants were descended from Aboriginal people who possessed native title rights and interests (NTRI) in the Overlap Area at sovereignty, and that those rights and interests were transmissible by descent in accordance with their laws and customs at the time of effective sovereignty (1872 – 1873) and therefore at sovereignty (1788). For the purposes of s 223(1)(b) and (c), they alleged that, by those same laws and customs, they presently have a connection with the Overlap Area and that the NTRI possessed by them were recognised by the common law of Australia.

Surrounding determinations

22 The Overlap Area and its wider surrounds are depicted in maps referred to by the primary judge as Map 1 and Map 3, now contained in Schedule A to these reasons. It is irregularly shaped and comprises the township of Oodnadatta, a surrounding area known as the Oodnadatta Common, the Oodnadatta airport and an area of land held by the Aboriginal Lands Trust under the Aboriginal Lands Trust Act 1966 (SA).

23 As can be seen from the maps, the Overlap Area is bounded by areas in respect of which determinations of native title have already been made.

24 Abutting its eastern and southern boundaries is a large area of land and waters subject to a determination made in 2012 by Finn J in Dodd v State of South Australia [2012] FCA 519. It will be referred to at times as the 2012 Arabana Determination. It relates to 68,823km2 of land including a place known as Hookeys Hole in the north, about which much evidence was given at trial because of its very close proximity to the southern boundary of the Overlap Area.

25 The description of the claim group in the Arabana Claim is identical to the description of the persons who hold the NTRI recognised in the 2012 Arabana Determination. At trial, the claimants asserted materially the same NTRI in the Overlap Area as those determined to exist by Finn J in Dodd.

26 Evidence before the primary judge included a map drawn by senior Arabana men (among others) in 1996 depicting the extent of Arabana country then asserted by them, which included the Overlap Area.

27 The proceeding culminating in the 2012 Arabana Determination did not include the Overlap Area. According to the Arabana, the omission is explained by a wish to facilitate an intended transfer of land to the Aboriginal Lands Trust for lease to the Dunjiba Community Council, which transfer never took place.

28 Abutting the northern and western boundaries of the Overlap Area is an area subject to a determination of native title made in 2006 in favour of the YA people: Yankunytjatjara/Antakirinja Native Title Claim Group v The State of South Australia [2006] FCA 1142. It will be referred to as the 2006 YA Determination.

29 Immediately to the north and east of the area subject to the 2006 YA Determination lie two areas subject to determinations in King on behalf of the Eringa Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia [2011] FCA 1386; 285 ALR 454 (Eringa No 1 Determination) and King on behalf of the Eringa Native Title Claim Group and the Eringa No 2 Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia [2011] FCA 1387 (Eringa No 2 Determination).

30 The Eringa No 1 Determination recognises the NTRI of members of the LSA and the YA peoples, a cohort that includes the same two groups that comprised the Walka Wani Claim group at first instance. The land subject to the Eringa No 1 Determination is approximately 25km north of the Overlap Area at its closest point. The Eringa No 2 Determination recognises the NTRI of the LSA, the YA and the Wangkangurru peoples and relates to land yet further to the north.

31 In advance of the trial, the Arabana filed an Amended Statement of Facts, Issues and Contentions (SFIC) by which they put forward the matters about which they would adduce evidence at trial. As to Arabana law and custom, the SFIC contained the following:

Arabana law and custom

35. The Arabana people acknowledge and observe a system of laws and customs under which they possess native title rights and interest in relation to the claimed areas.

36. That system of law and custom is both traditional and normative.

37. Central to those laws and customs are the traditional beliefs and practices of the Arabana people that connect them to their land, including the claimed area.

38. The Arabana use the term Ularaka to describe the body of knowledge custom and law often referred to as a ‘dreaming’.

39. Those Ularaka can be gender specific to particular sites, songs or simply stories of those sites and there are requirements about the telling or singing of that Ularaka. Members have responsibility for looking after the various Ularaka sites on their country.

40. This Ularaka is passed down in accordance with traditional law and custom from senior Arabana people to younger members in a manner consistent with Arabana law and custom.

41. The Ularaka relates to hundreds of sites within the broader Arabana country with particular significance relating to the Ularaka in relation to Kati Thanda, Lake Eyre, the Wabma Kadarbu Parks area, Lake Cadibarrawirracanna, sites on Finniss Springs station and Mound Spring sites.

42. In addition to Ularaka, Arabana people have strong spiritual beliefs firmly anchored in their laws and customs. They have a belief of a connection to their ancestral beings and other spiritual beings that they accept as being present in their life today. They believe that these spirits can impact on the present life of living people and that they must show respect to these ancestral beings. A failure to acknowledge and respect the ancestral beings can have serious consequences such as illness, mental distress, accident or misfortune.

32 The State admitted that the Arabana people continued to acknowledge and observe a system of laws and customs under which they possessed NTRI in the area subject to the 2012 Arabana Determination. However, it put the Arabana people to proof in respect of whether, by those traditional laws and customs the Arabana people held NTRI in the Overlap Area, and particularly on the matters pleaded at [36] and [37] in respect of connection. The State admitted the matters pleaded at [38] – [40], but only insofar as those paragraphs related to the area subject to the 2012 Arabana Determination.

The conclusions of the primary judge

33 The primary judge concluded that the Arabana apical ancestors had NTRI in the Overlap Area at effective sovereignty (at [410], [537], [842]). In their closing submissions at trial, all parties accepted that conclusion to have been an “inevitable” conclusion on the ethnographic, anthropological and linguistic evidence (at [842]). There is no challenge by any party to that finding on either appeal.

34 As to the significance of the surrounding determinations, the primary judge said:

54 It was common ground that each of the 2006 Yankunytjatjara/Antakarinja Determination and the 2012 Arabana Determination had ‘determined as a fundamental matter, once and for all’ that NTRI existed in the areas to which those determinations related and that the NTRI were held by the Yankunytjatjara/Antakarinja People and the Arabana People respectively. This means that each has been recognised as a society or communal group of people holding rights and interests possessed under traditional law acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by them having a connection with the respective determination areas. These determinations and these recognitions cannot be called into question in the present proceedings – see Lake Torrens Full Court at [198]-[202], [401].

55 The same may be said with respect to the Eringa No 1 and Eringa No 2 Determinations. As the State submitted, each of these four determinations is to be taken to have established conclusively that the identified Aboriginal peoples held NTRI, as described in the determinations, with respect to each determination area ‘at sovereignty and [have] at all times since then’, so that the Court should not attach any weight to evidence which is directly inconsistent with those determined facts: Lake Torrens Full Court at [198]-[201].

35 The primary judge had regard to a considerable body of historical evidence to the effect that there had been a progressive southward migration of the Arabana away from the Overlap Area (at [538] – [580]).

36 His Honour also had regard to the evidence of expert witnesses called by each party. Relevantly for these appeals, they were anthropologists Dr Scott Cane, Dr Belinda Liebelt and Mr Robert Graham (called by the Walka Wani), Dr Rodney Lucas (called by the Arabana), Dr Lee Sackett (called by the State), and an historian Mr Tom Gara (called by the State).

37 The Arabana called six lay witnesses. We will consider the relevant aspects of their evidence in the disposition of each argument on the appeal. The primary judge made the following observations by way of summary:

658 By way of brief summary of the evidence of the six Arabana witnesses, it can be said that none is presently a resident of Oodnadatta; two (Aaron Stuart and Leonie Warren) have lived there as permanent residents in the past, but the periods during which they did so were relatively short. For reasons which will become apparent, I think it probable that Aaron Stuart had had only one period of residence in Oodnadatta and that was attributable to him being stationed there as a Community Police Officer. With the exception of his involvement in a site clearance in 2004, Aaron Stuart does not seem otherwise to have been involved in the care of Arabana interests in the Overlap Area. The physical connections of the other witnesses to the Overlap Area have often occurred when they were passing through Oodnadatta (Sydney Strangways), when visiting relatives or friends, or when attending functions such as races and gymkhanas. There is, however, evidence of contemporary camping, hunting and gathering by Joanne and Leonie Warren, and to a lesser extent by Dr Arbon.

659 There is some, but by no means extensive, familiarity with Arabana law and culture, and some, but again not extensive, evidence of the passing on of that knowledge. There is relatively little evidence of actual protection of sites, of the teaching of law and culture in relation to particular sites or locations, of an intimate knowledge of the Overlap Area, and of attending to cultural responsibilities.

660 Aaron Stuart did know of the Arabana Ularaka and myths associated with Oodnadatta and I accept that he has been taught them by Laurie Stuart in particular. However, Aaron Stuart’s evidence did not convey a sense of being actually connected to the country through those Ularaka. Mr Strangways does know the Ularaka, but the knowledge by the other Arabana witnesses of them was limited.

38 His Honour set out the matters noted by Finn J in Dodd with respect to the continuing connection of the Arabana with the area to which that determination related (at [845]). He then made the following comments about the relevance of those matters to the resolution of the Arabana Claim in respect of the Overlap Area:

848 It is appropriate to commence by indicating my acceptance of the State’s submission that it is connection with the Overlap Area which must be established and not just connection with the wider region. However, that does not mean that one ignores the effect of the 2012 Arabana Determination. The Arabana obtained that Determination by satisfying the Court that, in contemporary Arabana law and custom, all Arabana country belongs to all Arabana generally. It is accordingly pertinent that the possession of NTRI under the traditional laws acknowledged and customs observed by the Arabana generally has been recognised.

849 Moreover, the Overlap Area is immediately adjacent to the area of the 2012 Arabana Determination and comprises a very small fraction of the overall area claimed by the Arabana as Arabana land. Its existence as a separate area is an artefact of colonial decisions (the proclamation of the town of Oodnadatta and the gazettal of the Common) which had no relationship with the bounds of Aboriginal country. This would make it natural for the Court to have regard to matters bearing on the Arabana connection in the larger area.

850 However, the same reasoning would apply, in substance, in relation to the claim of the Walka Wani, given the determinations over adjacent areas which they, or elements of them, have obtained.

39 The primary judge went on to observe that the Arabana had relied upon 10 matters that were said to establish the continuity of their connection with the Overlap Area in accordance with their traditional laws and customs. The first was reliance on the matters said to have been established by the 2012 Arabana Determination in respect of the adjacent area. On that subject, the primary judge said:

853 The Arabana relied on the matters established by the 2012 Arabana Determination in relation to the immediately adjacent land, including the finding that rights to Arabana country are held, under the Arabana system of law and custom, by Arabana society as a whole, with Arabana People and families having localised attachments, and that under Arabana rules, rights in land are based on filiation from known Arabana Persons.

854 I have accepted these matters but the requisite continuity of connection of the Arabana in the Overlap Area in accordance with traditional law and custom must be established by the evidence in these proceedings.

40 The primary judge went on to deal with the remaining nine matters in turn, many of which are now the subject of submissions on the Arabana Appeal, including evidence given by Arabana witnesses Mr Sydney Strangways and Mr Aaron Stuart. His Honour made further general observations about topics in respect of which he considered the evidence to be lacking, including:

912 Evidence of the matters to which Finn J referred in 2012 is lacking. There is a relative absence of knowledge of the Arabana normative rules relating to authority (several witnesses did not even claim [familiarity] with them); the evidence of the transition of Aboriginal law and custom to the younger members of the Arabana is limited (often, it seems, because they are not known); while Arabana place names are used, the Arabana moiety, kinship and totemic names are not; some of the Ularaka are not known, let alone passed on; and the continued engagement in traditional activities on the Overlap Area is not extensive.

913 There is of course a connection with the Overlap Area which arises from having been taught that it is Arabana country or from having been taught that one is Arabana and that Oodnadatta is Arabana country. It was connections of this kind which in the main were asserted by the Arabana witnesses. However, as indicated, the connection required by s 223 is a connection arising from the continuing acknowledgement of traditional laws and traditional customs observed by the claimant group.

914 It is the relative absence of acknowledgement of traditional law and observance of customs by which a connection by the Arabana to the Overlap Area is maintained which is, in my opinion, fatal to the Arabana claim.

41 In the result, the primary judge was not satisfied that the Arabana had established that, by their traditional laws and customs, they had a connection with the land or waters in the Overlap Area. His Honour expressed that ultimate conclusion (at [916]):

… I am not satisfied that the Arabana have established the maintenance of their connection with the Overlap Area in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by them. Their claim must be dismissed.

42 As a consequence, the question of whether the NTRI were recognised by the common law of Australia did not arise for consideration. Had the primary judge found the requisite connection in s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act to have been established, the recognition of the NTRI by the common law of Australia would not have been a contentious issue.

Issues arising on the appeal

43 By ground 1 of their Further Amended Notice of Appeal dated 9 May 2022 (Arabana NOA), the Arabana contend that the primary judge “erred in finding at [916] that the Arabana had not established the maintenance of their connection with the [Overlap Area] in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by them since effective sovereignty”. Nine Particulars to that ground are pressed.

44 Particulars 1, 2, 3, 4(a) and 4(b) allege that the primary judge misapplied s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act, including by finding that continuing connection required certain features to be proven or alternatively that the absence of those features weighed against a finding that connection had been maintained.

45 Particulars 4(c), 6, 8 and 9 impugn factual findings said to have been made other than in accordance with the evidence and established principle. They collectively assert that the primary judge erred in concluding that the evidence was insufficient to prove the Arabana Claim to the requisite standard.

46 Particulars 7 and 7A allege that the primary judge erred in failing to give effect to the “significance and probative force” of the 2012 Arabana Determination made by Finn J in Dodd.

47 Particular 5 is no longer pressed.

48 There is overlap between the three categories of alleged error. A central contention is that in concluding that the requisite connection in s 223(1)(b) was not proven, the primary judge asked himself the wrong question and so erred in concluding that the test for connection was not satisfied. More precisely, it is said that the primary judge erroneously emphasised the lack of evidence of connection manifested by the physical acknowledgement of traditional laws or physical observance of traditional customs occurring specifically within the geographical boundaries of the Overlap Area. It is submitted that the primary judge ought to have found that the 2012 Arabana Determination was sufficient in and of itself to compel the inference that the requisite connection with the Overlap Area existed and that that failure is a further manifestation of an erroneous construction or application of s 223(1)(b).

49 The Particulars otherwise raise allegations of error in factual findings, each of which must be considered independently as well as cumulatively.

The role of this Court

50 The appeals are by way of rehearing: Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), s 27. On such an appeal, the Court’s review of the primary judge’s findings of fact and inferences drawn from those facts are subject to the principles stated in Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118, Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 and more recently in Lee v Lee (2019) 266 CLR 129.

51 In Banjima People v Western Australia (2015) 231 FCR 456 it had been submitted that a trial judge in a native title proceeding had made findings that were against the weight of the evidence. The Full Court said that the contention confronted a fundamental difficulty (at [57]):

The primary judge heard substantial evidence on country. He alone saw the witnesses give their evidence and was able to weigh that evidence in the balance having seen the land to which the evidence referred as it was being given. He alone saw the performance of the anthropologists in concurrent session. The notion advanced by the State that the primary judge had no advantage compared to this Court in the weighing of the evidence overall is untenable. The State’s submissions fail to come to grips with the obvious significant advantage the primary judge enjoyed over this Court in respect of the overall weighing of the totality of the evidence, the need to establish error by the primary judge before appellate intervention could be justified, and the need to establish such error in circumstances such as the present by pointing to some finding contrary to ‘incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony’, ‘glaringly improbable’ or ‘contrary to compelling inferences’ (Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [28]-[29]).

52 The Full Court set out passages from the cases that reinforce over and again the need for appellate restraint in a proceeding of the present kind (at [58]). It is appropriate to repeat them here in full:

• Moses v Western Australia (2007) 160 FCR 148

[308] The difficulty faced by a party alleging an error in the fact finding process in a proceeding such as the present is formidable. The question whether the applicants for a native title determination have established the necessary degree of connection to land by traditional laws and customs is a matter of judgment involving an assessment of a wide array of evidence …

[309] Nevertheless, these circumstances, however challenging, do not alter the role of an appellate court, which was explained by Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ in Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [25] thus:

Within the constraints marked out by the nature of the appellate process, the appellate court is obliged to conduct a real review of the trial and, in cases where the trial was conducted before a judge sitting alone, of that judge’s reasons. Appellate courts are not excused from the task of ‘weighing conflicting evidence and drawing [their] own inferences and conclusions, though [they] should always bear in mind that [they have] neither seen nor heard the witnesses, and should make due allowance in this respect’ (Dearman v Dearman (1908) 7 CLR 549 at 564, citing The Glannibanta (1876) 1 PD 283 at 287).

In CSR Ltd v Della Maddalena (2006) 80 ALJR 458; 224 ALR 1 at [17], Kirby J (with whom Gleeson CJ agreed) explained some of the limitations on the appellate role inherent in the nature of the function as follows:

The ‘limitations’ introduced into the rehearing based on the record of the trial are those necessarily involved in that form of appellate procedure. Such limitations include those occasioned by the resolution of any conflicts at trial about witness credibility based on factors such as the demeanour or impression of witnesses; any disadvantages that may derive from considerations not adequately reflected in the recorded transcript of the trial; and matters arising from the advantages that a primary judge may enjoy in the opportunity to consider, and reflect upon, the entirety of the evidence as it is received at trial and to draw conclusions from the evidence, viewed as a whole.

(Footnotes omitted.)

• Western Australia v Ward (2000) 99 FCR 316

[222] In the course of presenting these submissions, the State has sought to challenge many specific findings on matters of detail as to the ancestry and connection of applicants and witnesses to parts of the claim area, and for this purpose the Court has been directed to short passages in the evidence of witnesses which appear to contradict particular findings. These aspects of the State’s submissions, in effect, invite the court to re-evaluate the mass of evidence received by the trial judge over the course of a very lengthy trial. Such a task would place an impossible burden on an appeal court. Numerous witnesses gave evidence at many sites of importance to the applicants …

• Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2001) 110 FCR 244

[202] His Honour’s finding that there was a period of time between 1788 and the date of the appellants’ claim during which the relevant community lost its character as a traditional Aboriginal community is not to be lightly disturbed on appeal to this Court. A finding that an indigenous community has lost its character as a traditional indigenous community involves the making of a judgment based on evidence touching on a multitude of factors. The hearing before his Honour was long and complex. As is mentioned in [95] above, evidence was taken from 201 witnesses and his Honour visited, and took evidence on, the claimed land on many occasions …

…

[204] Special difficulties which face an appeal court that is invited to re-evaluate evidence received by a trial judge in a case concerning a determination of native title were identified by Beaumont and von Doussa JJ in State of Western Australia v Ward at 377 [222]-[225]. It is likely that there were special difficulties in Ward that may not have been experienced in this case, or not experienced to the same extent. Nonetheless, considerable caution is appropriate before this Court infers that crucial evidence was not evaluated and necessary findings of fact were not made.

[205] In a case of this kind, the need for appellate caution adverted to by Lord Hoffmann in Biogen Inc v Medeva plc (1996) 36 IPR 438 at 452 is particularly strong. His Lordship there said:

The need for appellate caution in reversing the judge’s evaluation of the facts is based upon much more solid grounds than professional courtesy. It is because specific findings of fact, even by the most meticulous judge, are inherently an incomplete statement of the impression which was made upon him by the primary evidence. His expressed findings are always surrounded by a penumbra of imprecision as to emphasis, relative weight, minor qualification and nuance … of which time and language do not permit exact expression, but which may play an important part in the judge’s overall evaluation.

• Commonwealth v Yarmirr (1999) 101 FCR 171

[637] Although there may have been little dispute as to the facts as the primary facts were not in dispute, there is nevertheless a need for appellate caution before a different view is taken of the trial judge’s evaluation of the facts. As was said by Lord Hoffmann (with the agreement of all other members of the House of Lords) in Biogen Inc v Medeva Plc [1997] RPC 1 at 145 …

…

[639] In the present case there is the added difficulty that the trial judge’s evaluation of the facts is premised upon a plethora of factors which influenced his understanding and impressions of:

• the evidence given by the Aboriginal witnesses at various locations;

• the extensive documentary material;

• the relationship between that evidence and material and the sites to which they relate.

[640] The above matters resulted in the trial judge in the present case being in a situation of unique advantage over an appellate Court in his evaluation of the facts. In these circumstances the respondents have an onerous task in persuading the appellate court that the trial judge has ‘failed to use or palpably misused his advantage’: see Devries v Australian National Railways Commission (1993) 177 CLR 472 at 479 and State Rail Authority (NSW) v Earthline Constructions Pty Ltd (In liq) (1999) 73 ALJR 306 at 307; 160 ALR 588 at 589.

• Yorta Yorta (2002) 214 CLR 422

[63] … At least to the extent that the primary judge’s inquiry was directed to ascertaining what were the traditional laws and customs of the peoples of the area at the time of European settlement, the criticism is not open. The assessment of what is the most reliable evidence about that subject was quintessentially a matter for the primary judge who heard the evidence that was given, and questions of whether there could be later modification to the laws and customs identified do not intrude upon it. His assessment of some evidence as more useful or more reliable than other evidence is not shown to have been flawed …

(Emphasis in original.)

53 In the present case, the primary judge heard evidence from 20 Aboriginal witnesses in three separate tranches of evidence at Oodnadatta and at various locations on country in and around the Overlap Area between 30 September and 3 October 2019, in Alice Springs between 8 and 11 October 2019, and in Adelaide between 14 and 23 October 2019. The Court sat at Adelaide between 19 and 23 October 2020 to receive into evidence the expert reports, and to hear their concurrent oral evidence. The parties made final submissions on 11 and 12 March 2021. The trial was recorded in more than 3,500 pages of transcript.

54 The fact finding task involved the weighing of multiple considerations in determining whether the requisite connection in s 223(1)(b) was proven. That was an highly evaluative task. As the primary judge correctly observed, any distinction between the qualitative and quantitative nature of the evidence in the performance of the task was unhelpful and illusory.

55 The case is one in which the need for appellant restraint is apparent, although on both appeals it remains necessary to consider the application of the above principles to each particular allegation of error.

Significance of the 2012 Arabana Determination – Particulars 7 and 7A

56 By Particular 7A it is alleged that the primary judge erroneously negated the probative force of the 2012 Arabana Determination by wrongly concluding that inferences able to be drawn from it were equally able to be drawn in relation to the claim of the Walka Wani. There were three components to this argument.

57 First, it was submitted that there was a factual error in the conclusion that there existed a native title determination in favour of the Walka Wani in respect of any land or waters immediately adjacent to the Overlap Area. It is to be recalled that the 2006 YA Determination was not made in favour of the same persons who comprised the Walka Wani claim group: the Walka Wani comprising an amalgam of YA and LSA. It is correct to say that LSA do not hold NTRI in any immediately adjacent land or waters. As the Arabana correctly submitted, the nearest area in which the Walka Wani as a composite group hold NTRI is the land subject to the Eringa No 1 Determination, some 25 km to the north.

58 The reasons of the primary judge at [850] (extracted at [38] above) nonetheless disclose that he was alive to the circumstance that Walka Wani claim group did not wholly equate with the persons who hold native title by virtue of the neighbouring 2006 YA Determination. So much is apparent from the phrase “or elements of them”. His Honour’s reasoning may be fairly understood as recognising that some persons included in the Walka Wani claim group could point to the 2006 YA Determination as proof of a connection within the immediately adjacent area to which it related. The primary judge should not be understood as concluding that the inference of connection with respect to the adjacent area was an inference able to be drawn with respect to any persons included in the description of the Walka Wani who are not native title holders there. The first aspect of the argument is therefore rejected.

59 Secondly, the primary judge is said to have erred by equating the force of the inference that might be drawn in favour of the Arabana to that which might be drawn in favour of the Walka Wani by reference to the respective adjacent determinations.

60 We accept that the language at [850] implicitly suggests that each of the 2012 Arabana Determination and the 2006 YA Determination was at least capable of informing the question of connection in respect of each respective claim group in the same way and with the same force. To that extent the reasoning is incorrect, given the earlier finding that it was the Arabana and not the Walka Wani who had established that their apical ancestors were in occupation of the Overlap Area at the time of effective sovereignty and that, at that time, they held NTRI there in accordance with their traditional laws and customs. However, as will be explained, we do not consider that error to have resulted in error in the assessment of the case of the Arabana on the question of connection, having regard to the reasons for judgment as a whole.

61 Thirdly, it was submitted that by equating the inferences available to be drawn in favour of the Arabana and the Walka Wani by reference to the immediately adjacent determinations, the primary judge effectively negated the probative force of the 2012 Arabana Determination altogether and for that reason refused to draw the compelling inferences that naturally ought to have been drawn from it.

62 That argument is without merit. On a proper reading of the reasons as a whole, the primary judge made no finding inconsistent with the 2012 Arabana Determination and indeed made a number of findings concerning the Overlap Area by a process of inference from the facts and circumstances persisting on the larger area of adjacent land to the south. The primary judge:

(1) set out the traditional laws and customs of the Arabana by which rights and interest in land are possessed;

(2) set out (at [845]) the matters noted by Finn J in Dodd concerning the continuing connection of the Arabana in respect of the area subject to the 2012 Arabana Determination including:

(a) the continued observance of normative rules relating to authority, the transition of Arabana names and kinship terms;

(b) maintenance of knowledge of the traditional dreaming stories (Ularaka) and the normative rules related to them;

(c) the continued residence of Arabana people in the area; and

(d) the Arabana claimant knowledge of the area and their continued engagement in traditional activities including hunting and gathering for food;

(3) expressly stated that whilst connection with the wider region is insufficient to establish NTRI in the Overlap Area, that did not mean that the 2012 Arabana Determination should be ignored (at [848]);

(4) acknowledged that the 2012 Arabana Determination has been obtained “by satisfying the Court that, in contemporary Arabana law and custom, all Arabana country belongs to all Arabana generally” (at [848]);

(5) said that it was pertinent that the possession of NTRI under the traditional laws acknowledged and customs observed by the Arabana generally had been recognised (at [848]);

(6) observed that the Overlap Area comprised a very small fraction of the overall area that had been claimed by the Arabana as Arabana land (at [849]);

(7) recognised that its existence as a separate area was an artefact of colonial decisions (particularly the establishment of the township of Oodnadatta) which bore no relationship with the boundaries of Aboriginal country and that this would make it natural for the Court to have regard to matters bearing on the Arabana connection in the larger area (at [849]); and

(8) expressly accepted a number of matters upon which the Arabana relied arising out of the 2012 Arabana Determination, including the finding that rights to Arabana country are held, under the Arabana system of law and custom, by Arabana society as a whole, with Arabana people and families having localised attachments, and that under Arabana rules, rights in land are based on filiation from known Arabana persons (at [853] – [854]).

63 As discussed below, the primary judge went on to have regard to a number of matters affecting the immediately adjacent area and made an assessment of their relevance to the Overlap Area in the context of the evidence as a whole. In our view, the misstatement of the beneficial evidentiary value of the 2006 YA Determination to the Walka Wani Claim was not causative of error in his Honour’s nuanced and thorough assessment of all of the evidence bearing on the Arabana’s asserted maintenance of connection with the Overlap Area. It is plain that the primary judge did not draw the singular inference from the 2012 Arabana Determination now urged on this appeal. However, his Honour’s reasons for not drawing that inference were not related to his earlier statement equating the availability of any such inference with that available to be drawn in favour of the Walka Wani.

64 By Particular 7 it is alleged that in undertaking his assessment of the evidence, the primary judge “erred in failing to appreciate and give effect to the significance and probative force” of the 2012 Arabana Determination. That broader argument must be rejected in light of our findings with respect of the remaining Particulars.

65 In oral submissions the argument went further: it was said that the 2012 Arabana Determination was sufficient in and of itself to establish that the Arabana had maintained a connection with the Overlap Area in accordance with s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act and that the primary judge ought to have so found.

66 The submission that the 2012 Arabana Determination was sufficient evidence to establish the requisite connection with the Overlap Area was not advanced by the Arabana at any time in the course of the trial. Unsurprisingly, there is no discrete attention given to it in the reasons of the primary judge. The reasons reflect the manner in which the Arabana presented their case with respect to s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act at trial, that is, by reliance upon a multiplicity of factual matters that together were said to be sufficient to discharge their onus of proof. The 2012 Arabana Determination was but one of them.

67 Further still it was alleged that the conclusion of the primary judge with respect to the issues under s 223(1)(b) were precluded as a matter of law because they were said to be inconsistent with certain aspects of the 2012 Arabana Determination that were said to be legally binding. When pressed to identify which part of the reasons was affected by error of that kind, Counsel for the Arabana pointed to the following passages (together with [912] and [913] extracted earlier in these reasons):

907 Looked at more generally, a number of matters were absent from the Arabana evidence concerning connection. There is relatively little evidence of ritual associations with sites, or of ‘singing of country’, and no evidence of the storage of sacred objects on the Overlap Area. In the case of the Arabana witness with the most knowledge of original traditional law and custom (Mr Strangways), there is no evidence of him coming back to the Overlap Area to reconnect with it. His physical presence on the Overlap Area is confined to passage through it. He does not visit sites and it seems has not spent a night in Oodnadatta since the late 1950s or early 1960s. His acknowledgement of Arabana traditional law and observance of Arabana traditional custom in relation to the Overlap Area is now of a spiritual rather than practical kind.

908 The Court was not asked to hear gender restricted evidence from the Arabana and, even though Aaron Stuart had concerns about some of his evidence being heard by women, he did give evidence at one site without any objection to the presence of females and there was no evidence that gender specific division of knowledge is being taught within the Arabana People.

909 The Ularaka relating to the Overlap Area are not being taught to the younger generations. I note again that Aaron Stuart said that he had taught ‘a little bit, now and then’ to his own children. Leonie Warren acknowledged that she had not been taught any of the Ularaka relating to the Overlap Area and Joanne Warren was unsure about the details of several.

910 Much of this is explicable given the movement of the Arabana away from Oodnadatta to which I have referred earlier.

911 Section 223 requires not just that the traditional laws and customs be known but that rights in land in this case the Overlap Area, be possessed by the acknowledgement and observance respectively of those laws and customs. It is by that acknowledgement and observance that the connection with the Overlap Area must be shown. Knowledge of what used to be the case is insufficient. Mr Strangways plainly has knowledge of Arabana traditional law and custom, and he would acknowledge and observe Arabana law and custom in the Overlap Area. Aaron Stuart’s evidence showed some knowledge of Arabana traditional law and customs but relatively little by way of actual acknowledgement and observance of them giving rise to a connection with the Overlap Area.

(emphasis in original)

68 We do not otherwise consider the conclusions in those paragraphs to be contrary to any legal principle concerning the binding nature of the 2012 Arabana Determination. The relevant principles were briefly summarised by the primary judge at [54] (extracted at [34] above) by reference to what the Full Court said in Starkey v South Australia (2018) 261 FCR 183. As identified by Reeves J (with whom White J agreed at [401]), that statement of principle may be enlarged upon as follows:

(1) a native title determination is commonly described as a judgment in rem that is binding on all of the world: Starkey (at [198]), and see Wik Peoples v Queensland (1994) 49 FCR 1 (at 8); Dale v Western Australia (2011) 191 FCR 521 (at [92]);

(2) the particular matters of which a native title determination dispose once and for all are to be ascertained according to the provisions of the NT Act, particularly s 223(1) and s 225: Starkey (at [198]);

(3) section 225 requires that a determination of native title in relation to particular land and waters identify who holds the rights comprising the NTRI concerned, the nature and extent of those NTRI in relation to that area, the nature and extent of other interests in relation to that area, and the relationship between those two sets of rights: Starkey (at [199]);

(4) the NTRI referred to in s 225 are those defined by s 223(1): Starkey (at [200]);

(5) the traditional laws and customs from which those NTRI derive are fundamental to that definition: Starkey (at [200]);

(6) the NTRI recognised in a determination are those having their origin in the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the native title holders: Starkey (at [200]);

(7) accordingly, one of the most fundamental matters disposed of once and for all in a determination is that the NTRI possessed in the area covered by the determination are of a traditional nature, that is, they are NTRI having pre-sovereignty origins: Starkey (at [201]);

(8) in addition, to obtain a determination of native title the native title holders must establish that their connection with the area by those traditional laws and customs has been maintained: Starkey (at [202]); and

(9) accordingly, the determination recognises as a fundamental matter that the NTRI possessed in relation to the area have “that intrinsic continuity element”: Starkey (at [202]).

69 It is an abuse of process for a party to seek to re-litigate a fundamental matter expressly or necessarily encompassed within an earlier determination, and to do so may otherwise give rise to an issue estoppel: Dale (at [90] – [93]), CG v Western Australia (2016) 240 FCR 466 (at [46]). In addition, a party to a native title determination application cannot lead evidence that is inconsistent with a conclusion upon which an existing native title determination is based: Starkey (at [240]); Smirke on behalf of the Jurruru People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2020] FCA 1728 (at [612] – [613]).

70 However, it remains that the factual matters essential to a valid determination of native title are geographically specific, so that, for example, an existing determination of the nature of NTRI held by a group over one area will not preclude a party from contending for a rights of a different nature over an adjacent area of land. As the Full Court said in Fortescue Metals Group v Warrie (2019) 273 FCR 350 (at [112]):

The exercise of judicial power in Daniel/Moses created, to use the language in Tomlinson at [20], a ‘new charter by reference to which [the question of native title in the Daniel/Moses land and waters] is in future to be decided as between’ those who were parties to that claim, and a new charter in rem, in relation to that land and waters. That included a wide range of existing proprietary interest holders, as the Moses and Daniel determinations demonstrate, whose proprietary rights and interests were either adjusted, or preserved, upon the recognition of the Yindjibarndi People’s and the Ngarluma People’s native title in the Daniel/Moses land and waters. It also included a range of future proprietary interest holders who would be required to recognise the native title of the Yindjibarndi and Ngarluma Peoples, to the extent set out in the determination. However the ‘charter’ was as to that land and waters, and as to all existing and future interest holders in that land and waters. In terms of then existing proprietary interest holders, this did not include the appellant. The Daniel/Moses determinations ‘quelled’ the controversy about native title in relation to that land and waters. A determination under s 225 could not reach beyond the land and waters which were the subject of the claim, and any non-native title proprietary interests in that land and waters. Again, we do not accept this outcome has any automatic or inevitable impact on the claim to the Warrie land and waters, or on the myriad of (different) sets of persons who have, or may have in the future, proprietary interests in the Warrie claim area.

(emphasis in original)

71 An in rem order may otherwise serve as prima facie evidence of the facts that are essential to its validity: Harvey v The King [1901] AC 601 (at 611); Hill v Clifford [1907] 2 Ch 236 (at 244 – 245).

72 The authorities summarised above are based on two distinct bodies of principle. The first is concerned with the implications of a determination of native title being a judgment in rem as it affects rights and interests in land. In that respect it is enforceable against all of the world. The second is concerned with the conduct of litigation and the consequences of issues being raised (or not) by the parties and resolved (or not) by the Court in an earlier proceeding.

73 With respect to the principles concerning judgments in rem, it will be necessary to identify those facts that are essential to the validity of the 2012 Arabana Determination and those that are not. In the performance of that task, care should be taken to distinguish between the orders that together comprise the determination (and the factual preconditions to their validity) and other facts that might be referred to in the published reasons for making the orders.

74 A determination of native title may be made under s 13 and s 61 of the NT Act, as was the case at first instance. Alternatively, a determination of native title may be made by consent under s 87 or s 87A of the NT Act, as was the case with respect to all of the consent determinations surrounding the Overlap Area.

75 Reasons for judgment delivered after a contested trial of the issues arising on a native title claimant application will contain factual findings, based on evidence and established to the civil standard of proof. Those findings may supply factual detail as to how the elements of the definition of native title were fulfilled in the particular case and may give rise to an issue estoppel or found an argument as to abuse of process as against parties to that action. The persons comprising the Walka Wani claim group were not party to the proceeding culminating in the orders in Dodd constituting the 2012 Arabana Determination. Such persons are of course bound by the 2012 Arabana Determination by virtue of its characterisation as a judgment in rem. But it is not correct to treat all factual matters referred to in the reasons for judgment in Dodd as having the same character.

76 Determinations of native title made by consent are, of course, judgments in rem having the same force as those made after a contested trial. However, it does not follow that all factual matters referred to in the reasons accompanying a consent determination necessarily have the status of a finding that may give rise to an issue estoppel or an abuse of process, nor that they are “findings” essential to the validity of the judgment. The factual matters essential to the validity of a consent determination must be determined by reference to the NT Act itself.

77 A determination of native title must set out details of the matters mentioned in s 225 (which defines the expression “determination of native title”): NT Act, s 94A. Except in cases where the power under s 87 or s 87A is exercised, it is a precondition to the making of a determination that the Court be satisfied that all of the essential elements of a determination of native title are established on the evidence to the civil standard of proof. By contrast, the Court may make a determination of native title without conducting a hearing to resolve disputed questions of fact, if the criteria under s 87 or s 87A of the NT Act are met.

78 Section 87 applies if, at any stage of a proceeding after the end of a prescribed period the parties reach an agreement on the terms of the determination, the agreement is signed by all of the parties and the agreement is filed in the Court: NT Act, s 87(1). The purpose of the power in s 87 is to give effect to the parties’ agreement without the need to conduct a trial to resolve substantive factual questions. As North J explained in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474:

37 In this context, when the court is examining the appropriateness of an agreement, it is not required to examine whether the agreement is grounded on a factual basis which would satisfy the Court at a hearing of the application. The primary consideration of the Court is to determine whether there is an agreement and whether it was freely entered into on an informed basis: Nangkiriny v State of Western Australia (2002) 117 FCR 6; [2002] FCA 660; Ward v Western Australia [2006] FCA 1848. Insofar as this latter consideration applies to a State party, it will require the Court to be satisfied that the State party has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application: Munn v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109; [2001] FCA 1229. …

38 The power conferred by the Act on the Court to approve agreements is given in order to avoid lengthy hearings before the Court. The Act does not intend to substitute a trial, in effect, conducted by State parties for a trial before the Court. Thus, something significantly less than the material necessary to justify a judicial determination is sufficient to satisfy a State party of a credible basis for an application. The Act contemplates a more flexible process than is often undertaken in some cases. …

79 See also Nelson v Northern Territory (2010) 190 FCR 344 (at [8] – [13]).

80 It is not uncommon for reasons accompanying a consent determination to set out some of the materials to which the State party has referred in discharging its responsibilities and the factual matters referred to in those materials. The reasons of Finn J in Dodd are illustrative (at [5]):

I have had the benefit of joint submissions filed by the applicant and the State. As will be seen they demonstrate why the State is satisfied that the agreed determination is an appropriate and proper one. The submission itself provides considerable reassurance to the court in the present application. I will refer to the material it traverses at some length, beginning with a description of the Determination area itself which is of no little significance to Australians generally.

81 However, the factual matters informing the State party’s position are not matters about which the Court has conducted a trial. The reasons in such cases should not be understood to contain “findings” of a kind to which the principles relating to issue estoppel or abuse of process might readily apply, other than findings to the effect that the essential preconditions for the making of a consent determination are met. In the exercise of the powers conferred by s 87 and s 87A the Court does not concern itself with a factual enquiry as to how the elements of the definition of native title are satisfied. Rather, the Court’s role is to satisfy itself that the draft determination put forward by the parties is one that sets out the matters referred to in s 225 of the NT Act, as required by s 94A. It is neither necessary nor appropriate in that legal context to make findings about (for example) the content of Aboriginal law and custom under which NTRI are possessed, nor as to how the requisite connection under s 223(1)(b) has been maintained, nor as to intermural matters concerning relationships between particular native title holders vis a vis each other in relation to the land and waters.

82 Accordingly, when it is said on this appeal that the findings of the primary judge were impermissibly inconsistent with the 2012 Arabana Determination, it is necessary to identify precisely what is meant by the submission. It should not be presumed that Finn J in Dodd enquired into the facts asserted by the applicant party in its dealings with the State, nor that his Honour made factual findings on the balance of probabilities. To the extent that Finn J’s reasons for judgment are expressed in language suggesting that “findings” had been made by the Court, for the most part the findings were not essential to the resolution of the application before him and do not enliven the principles summarised above with respect to judgment in rem on issue estoppel.

83 It was further submitted that the primary judge’s conclusion that connection in accordance with s 223(1)(b) had not been established necessarily involved a denial or contradiction of fundamental matters established in Dodd because it involved a rejection of the contention that the Arabana continue to be a society defined by their acknowledging a normative system of laws and observance of customs having continuing vitality today. In written submissions the Arabana articulated the “essential elements” of their recognition of native title in Dodd in the this way (at [13]):

The determination of native title in Dodd determined that the Arabana People were a society that has continued to observe and acknowledge the pre-sovereignty laws and customs of the Arabana People, under which NTRI were and are still possessed and by which they have connection to the land and waters of the Arabana 1 Determination area. Moreover, it determined (implicitly or expressly) inter alia: the normative rules for membership of the Arabana People; that the laws and customs of the Arabana People, while different in some respects from the classical laws, are still properly characterised as being ‘tradition’ in the relative sense; that the members of the Arabana People are the descendants and/or successors of the Arabana People who at sovereignty held rights and interests to the area; that these laws and customs have been observed and acknowledged substantially uninterrupted since pre-sovereignty times by the Arabana People (including their forebears); and that the laws and customs are of a kind that are capable of and did generate rights and interests in the land, being rights and interests originally held by the at-sovereignty Arabana and now held by the current members of the Arabana People. These are all essential elements to the positive finding of native title in the Arabana 1 Determination.

84 It may be accepted that one of the matters disposed of once and for all by the 2012 Arabana Determination was that the NTRI described in that determination were of a traditional nature in the sense that they owed their existence to law and custom that existed pre-sovereignty and that had continued to be acknowledged and observed to the present day: Starkey (at [201]). Also decided once and for all was the fact that traditional laws and customs that gave rise to a connection in the determination area had continued to exist, substantially uninterrupted, since sovereignty: Starkey (at [202]). Those matters are essential for the validity of a determination of native title, whether made by consent or upon a contested trial. The reasons of the primary judge (at [54]) recorded a proper understanding of those matters.

85 As the High Court said in Yorta Yorta (at [50]) “if the society out of which the body of laws and customs arises ceases to exist as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs, those laws and customs cease to have continued existence and vitality”. The 2012 Arabana Determination recognises that the Arabana acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs, that is, laws and customs comprising a normative system.

86 The 2012 Arabana Determination recognised the essential fact that connection with the land and waters subject to that Determination has been maintained. All of that is accepted so far as it relates to the requirement of connection in s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act. All of it is geographically specific.

87 It was then submitted that the question of whether the Arabana have maintained a normative system that gives rise to NTRI since sovereignty was answered decisively in Dodd and that “there was nothing left to find” on that topic with respect to the Overlap Area. Again, that submission overstates the legal effect of the 2012 Arabana Determination.

88 The conclusion of the primary judge that the requisite connection with the Overlap Area had not been proven did not involve a denial that the Arabana are a group of Aboriginal people united in a body of traditional laws and customs that continues to have vitality today and that gives rise to NTRI in neighbouring land. The undeniable connection with the neighbouring land by those laws and customs did not constitute proof that the Arabana continued to maintain a connection with the Overlap Area by those same laws and customs. The primary judge had regard to the 2012 Arabana Determination as relevant, as identified earlier in these reasons. However, his Honour did not err in failing to find that it provided the complete answer to the disputed questions before him (noting that no such submission had been made).

89 It was then submitted that the failure of the primary judge adopted an erroneous “parcel by parcel” approach to the determination of NTRI in the Overlap Area. In that regard it was emphasised that the Overlap Area was but a small portion of a much larger region in respect of which the Arabana had claimed NTRI (and the only portion left to be determined) such that a parcel by parcel analysis was not called for. As we understand it, that argument was another way of asserting that the 2012 Arabana Determination was sufficient evidence in and of itself to compel the inference that the requisite connection had been maintained in the Overlap Area. It was also another way of saying that the primary judge erroneously confined his search for evidence of physical and tangible activities evidencing the acknowledgment of traditional laws or observance of traditional customs specifically within the boundaries of the Overlap Area. We do not accept either argument for reasons that will become clear in the disposition of the remaining Particulars.

90 The statement of the primary judge that it was necessary for the Arabana to adduce evidence going to the requirement for connection in the particular case was entirely orthodox and undoubtedly correct. If that constituted a “parcel by parcel” approach it may be because the Arabana commenced separate proceedings for native title over separate parcels of land, the Arabana Claim being one that was opposed by the State and tried by way of an adversarial process in which the rules of evidence applied. The Arabana were put to proof on all aspects of the Arabana Claim, so requiring that the test for connection be established with respect to the particular land and waters comprising the Overlap Area. Any failure to draw an inference of connection solely by reference to the matters determined conclusively in Dodd did not offend the principles stated in the authorities cautioning against a parcel by parcel approach.

91 The circumstances may be different in the case of a native title claimant application under the NT Act where there is no opposition in relation to any particular geographical aspect of it on the question of connection. In cases of that kind, for the purposes of s 223(1)(b), inferences concerning connection with respect to the whole of the claimed area may be readily drawn where they are reasonably available, and particularly where no defence case is erected against them. However, it is always open to a respondent in native title proceedings to defend the claim (including by reference to s 223(1)(b)) insofar as it relates to a part of the area to which the claim relates. When that occurs it is the duty of the trier of fact to consider the evidence as it relates to the discrete contested parcel.

92 Here, the primary judge had regard to a body of evidence that weighed against the inference of connection that might otherwise have been drawn by reference to the 2012 Arabana Determination. Critically, that evidence included historical circumstances supporting a finding that the Arabana had moved generally south and east from the Overlap Area progressively after sovereignty (at [539]). As discussed below, the primary judge was aware that physical dislocation from the relevant land and waters did not necessarily make proof of connection in accordance with s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act impossible, but it was nonetheless a significant factual consideration against which the evidence of connection adduced by the Arabana fell to be assessed.

93 Particulars 7 and 7A are accordingly rejected.

Asserted error in the application of s 223(1)(b) – Particulars 1 to 4(b)

94 These particulars are expressed as follows:

1) The primary Judge erred in failing to approach the assessment of Arabana connection for the purposes of section 223(1)(b) of the Native Title Act 1994 (Cth) (NTA) by identifying:

a. the content and nature of the Arabana claimants’ traditional laws and customs found to exist at effective sovereignty;

b. how, pursuant to those Arabana traditional laws and customs:

i. NTRI in land and waters arise; and

ii. how the Arabana connect to land and waters; and

c. whether connection in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed had subsequently ceased to exist.

2) In circumstances where the primary Judge correctly found that ‘the required connection with the land or waters is essentially spiritual’ (at [51]) and that the Arabana witness Sydney Strangways:

a. was ‘a singularly impressive witness, being honest, knowledgeable, articulate, insightful and responsive to the questions ... I have confidence in accepting his evidence’ (at [603]);

b. has, a ‘deep cultural knowledge of Arabana culture and law and gave several instances of compliance with it’ (at [622]);

c. is the oldest Arabana person alive and engages in a lot of teaching (at [619]);

and

d. has a spiritual acknowledgement and observance of Arabana traditional law and custom in relation to the Claim Area (at [907 and [911]);

the primary Judge misapplied the test for connection in failing to find that the spiritual acknowledgement and observance of Arabana traditional law and custom in the Claim Area was sufficient in context to establish continuing connection.

3) The primary Judge erred in finding that continuing connection to the Claim Area required the following features, when there was no evidence that those features were an essential component of Arabana traditional law and custom; or, in the alternative, erred in finding that the absence of those features was relevant to, and weighed against, the maintenance of continuing connection by the Arabana:

a. the absence of Arabana initiation ceremonies since at least 1958 (at [882] and [904]) and failed to have regard to the evidence that was given, and not challenged, about the reasons for cessation of those ceremonies consistent with traditional law and custom;

b. absence of ritual associations with sites and storage of sacred objects on the Claim Area (at (907]);

c. absence of uninterrupted residence, proof of occupation or possession of the Claim Area (see findings at [856], [857], [896] and [907]);

d. lack of recent enforcement of control of access by others to enter the Claim Area (at [896]);

e. that teaching of ularaka concerning the Claim Area must be to persons with a connection to the Claim Area (at [874]);

f. that some ularaka are not known or passed on by some witnesses (at [912]).

4) The primary Judge erred in finding that contemporary activities, namely the holding of funerals and sorry business (at [882] and [904]); attendance at social activities including races, gymkhanas, and bronco brandings (at [905]); hunting and gathering of food (at [871]); and residing in Oodnadatta (at [863]) were not conducted in accordance with traditional law and custom, and erred in:

a. failing to apply the majority in Member of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58 (Yorta Yorta) at [83] and accordingly consider whether any change to, or adaptation of Arabana traditional law and custom was nevertheless a continuation of the same body of traditional law and custom, adapted to modern circumstances;

b. making findings that were inconsistent with the findings of Finn J in the neighbouring Arabana Consent Determination in Dodd v State of South Australia [2012] FCA 519 (Arabana 1);

95 Common to all of the submissions on these grounds was a contention that the primary judge erroneously confined his analysis to a search for evidence of activities constituting acknowledgment of traditional laws and observance of traditional customs physically occurring in the Overlap Area and erroneously discounted or ignored evidence pertaining to the wider region of Arabana country. It is convenient to address that broader contention before turning to each of the Particulars.

96 The primary judge identified the test under s 223(1)(b) in terms that are not challenged as follows (at [51]):

Section 223(1)(b) requires expressly that the claimant group have a connection with the land or waters in question ‘by [the] laws and customs’, ie, by the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the group: WA v Ward at [64]; Starkey on behalf of the Kokatha People v South Australia [2018] FCAFC 36, (2018) 261 FCR 183 (Lake Torrens Full Court). This requires an identification of the content of the traditional laws and customs as they relate to the area in question and, secondly, the characterisation of the effect of those laws and customs as constituting a ‘connection’ of the peoples with the land or waters: ibid; Bodney v Bennell [2008] FCAFC 63; (2008) 167 FCR 84 at [165]. The required connection with the land or waters is essentially spiritual: WA v Ward at [14] (‘the spiritual or religious is translated into the legal’). Accordingly, s 223(1)(b) does not require that the connection be physical, although it may be of that kind: Western Australia v Graham (on behalf of the Ngadju People) [2013] FCAFC 143; (2013) 305 ALR 452 at [37]. See also Sampi v Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 at [1079]. Further, the required connection is not by the Aboriginal People’s rights and interests: it is by their laws and customs: Bodney v Bennell at [165]. An applicant must establish that the connection has, in reality, been substantially maintained since the time of sovereignty: Bodney v Bennell at [161], [179].

97 After concluding that the Overlap Area was Arabana country at sovereignty, the primary judge identified the principal issue as being whether the Arabana “have established that they have continued to possess the rights and interests in the Overlap Area under the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by them and have thereby maintained connection with the Overlap Area” (at [843]). That formulation of the issue appears to encompass the elements in both s 223(1)(a) and (b) of the NT Act. At trial it was referred to by the parties “in shorthand as being whether the Arabana have established continued connection with the Overlap Area”.

98 The primary judge again summarised the principles in the following terms (at [847]):

The principles recognised in the authorities relating to the assessment of continued connection include:

(a) connection involves the continuing internal and external assertion by the claimant group of its traditional relationship to the country defined by its laws and customs: Sampi at [1079]; Bodney v Bennell at [173];

(b) connection may be established by evidence of physical presence, but its absence is not fatal to the continuing connection: Bodney v Bennell at [171]-[174];

(c) non-physical forms of connection may include spiritual, cultural, social and utilisation connections: Yanner at [37]-[38]; Ward FC at [323]; Akiba FC at [172], [655];

(d) the assessment of connection requires, first, an identification of the content of the traditional laws and customs and, secondly, the characterisation of the effect of those laws and customs as constituting a ‘connection’ of the peoples with the land or waters in question: WA v Ward at [64];

(e) the connection need not be maintained in the same manner as it was at effective sovereignty. Account may be taken, amongst other things, of displacement and depopulation.

99 That statement of principle is in accordance with the authorities to which his Honour referred.

100 The primary judge again restated the question at [911], extracted at [67] above. Counsel for the Arabana submitted that the statement of the test in that passage is wrong because it does not accord with the statutory language in s 223(1)(b). It was submitted that the “rights must be possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by the Aboriginal people” (original emphasis) and that the rights “do not need to be possessed by the acknowledgement and observance of those laws and customs (whatever that might mean).” (original emphasis) It was submitted that the wrong emphasis introduced a geographic component to acts of acknowledgment and observance that is not a requirement of s 223(1)(b).

101 The language employed by the primary judge at [911] is not strictly in accordance with the language of s 223(1)(b) of the NT Act. That much of the Arabana’s submissions may be accepted.