Federal Court of Australia

Automotive Invest Pty Limited v Commissioner of Taxation [2023] FCAFC 129

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LOGAN J:

1 On 28 May 2016, a business operated by the appellant, Automotive Invest Pty Limited, opened its doors at premises in West Gosford in New South Wales. The business traded under the name, “Gosford Classic Car Museum”.

2 How, one might ask rhetorically, could the operation of a “museum” ever have given rise to a luxury car tax (LCT) and a related goods and services tax (GST) controversy between the appellant and the respondent Commissioner of Taxation?

3 In part, the answer is, as is now conceded by the Commissioner, that each of the motor vehicles in question (termed the assessed vehicles) and on display at the so-called “museum” was trading stock. Yet that fact alone, one might think, ought to lead, inexorably, to an absence of controversy.

4 Delving further into the facts, another part of the answer to the rhetorical question posed is that the appellant’s choice of name for its retail motor vehicle dealership and related method of promoting the sale of its trading stock is the source of the controversy. A further part of the answer is that the appellant’s adoption of its business name and related promotional stratagems proved conspicuously successful in the sale for reward of a diverse range of rare, unusual or “classic” motor vehicles. Yet another part of the answer is that some but never even remotely the predominant part of the income derived by the appellant in the operation of the business came from its charging and receiving an entry fee to those who sought to enter its premises in order to view and, if so disposed, purchase, its trading stock.

5 The learned primary judge referred from the outset, and then repeatedly thereafter, in his reasons for judgment to the business conducted by the appellant and the premises at West Gosford, as “the museum”. With respect, an at least potential risk with the adoption of that nomenclature may be its tendency to engender a pre-conceived characterisation of the, or even a, purpose of the use of the motor vehicles by the appellant, to the exclusion of an objective determination of purpose (or whether there is truly more than one purpose) of the use of the assessed vehicles on the whole of the evidence.

6 To adopt an analogy, to term an art retailing business and related premises a “gallery”, as opposed to an “art dealership”, may tend to engender a preconception that an independent purpose of the business, its related premises and the artworks found there is just to display the artworks to those visiting the premises, even though each and every one of those artworks is for sale. That preconception may be reinforced by the knowledge that only a minority of those visitors end up being purchasers.

7 The risk is that a characterisation of the purpose of the use of the artworks will be coloured by a nomenclature occasioned preconception, to the exclusion of what, objectively, the whole of the evidence truly reveals. It is just that, in the case of the use of the term “gallery”, the ordinary experience of life and related English usage at least diminishes that risk, because of a greater familiarity of encounter with businesses and premises which, although termed a “gallery”, are in fact retail art dealerships. That greater familiarity of encounter and related English usage would also make it an unremarkable conclusion that the only purpose of the use of the artworks on display at the “gallery” was to sell them, with everything else being subordinated or ancillary to that.

8 In my view, there is no denying the correctness of the appellant’s submission that, “[t]he label given to the business premises, whether it be ‘car yard’, ‘garage’, ‘dealership’, ‘shop’, ‘gallery’, ‘showroom’, or ‘museum’ is not a substitute for undertaking a proper analysis of the appellant’s activities.”

9 In the profession of arms, the risk in the development of military plans of a proper analysis of relevant factors being distorted by preconception is known as a risk of “situating the appreciation”. This entails, “leaping to a solution and then tailoring the logic to fit”: Martin Dunn, Redefining Strategic Strike: The Strike Role and The Australian Army Into the 21st Century, Australian Army Land Warfare Studies Centre, Working Paper No. 102, April 1999, p 45. Although this military analogy was not in terms used in the appellant’s submission, it exactly encapsulates its essence and the related, alleged error made by the primary judge. Indeed, as will be seen, adoption of the approach promoted by the appellant is dictated by longstanding, analogous authority concerning exclusivity of use based exemptions in rating and revenue law.

10 Before delving further into the facts and the authorities, it is desirable to set out the issues which were controversial in the original jurisdiction and the legislative context in which they arose. That task is facilitated by the care and precision with which the learned primary judge addressed that same subject. What follows on these subjects borrows heavily from his Honour’s reasons for judgment.

11 There were, and remain, two principal issues in dispute between the parties. These are whether:

(a) the applicant had “increasing luxury car tax adjustments” under s 15-30 and s 15-35 of the A New Tax System (Luxury Car Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (LCT Act); and

(b) the input tax credits which the applicant could claim were limited by s 69-10 of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (GST Act).

The LCT issue

12 The LCT issue arises in this way. If an entity can “quote” its Australian Business Number (ABN) when acquiring or importing a vehicle, it will not be subject to LCT. The system of quoting is designed to prevent LCT becoming payable until the vehicle is imported or sold at the retail level.

13 Where an entity was supplied with, or imported, a luxury motor vehicle and no LCT was payable, because the entity quoted for the supply, the entity will have an “increasing luxury car tax adjustment” if it later “use[s] the car for a purpose other than a *quotable purpose”: s 15-30(3) (supply); s 15-35(3) (importation).

14 The term “quotable purpose” means “a use of a *car for which you may *quote under section 9‑5”: s 27-1 of the LCT Act. Section 9-5(1) of the LCT Act provides for the circumstances in which an entity is entitled to quote:

You are entitled to *quote your *ABN in relation to a supply of a *luxury car or an *importation of a luxury car if, at the time of quoting, you have the intention of using the car for one of the following purposes, and for no other purpose:

(a) holding the car as trading stock, other than holding it for hire or lease; or …

15 The Commissioner does not now dispute that each of the motor vehicles in the group assessed, the La Ferrari motor vehicle now included, which were imported or acquired by the appellant before it commenced operations at Gosford on 28 May 2016, was trading stock. Further and in any event, the appellant did quote at the time of importation or acquisition in respect of these vehicles. That entitlement remains controversial in relation to the La Ferrari motor vehicle, because the Commissioner contends it was not then intended to be held solely as trading stock because it was intended for display in the “museum”. In respect of the La Ferrari motor vehicle, that is an additional reason why the Commissioner contends he was entitled to make an increasing adjustment (see especially, s 15-35(3)(b)(i)). Although that quote was effective, because an ABN was in fact quoted, such that LCT was not payable at the time of importation (s 7-10(3)(a) and s 9-20, LCT Act), that does not prevent the later assessment of an increasing adjustment (see especially, s 15-35(3)(b)(i)).

16 The principal issue in the appeal remains whether, as the primary judge found it has, the appellant has an increasing adjustment on the basis that, once the vehicles were placed in the Gosford premises, the appellant started to “use the car[s] for a purpose other than a *quotable purpose”: s 15-30(3); s 15-35(3)?

The GST issue

17 By reason of s 69-10 of the GST Act, if a taxpayer acquires or imports a vehicle, the value of which exceeds the “car limit”, and the taxpayer was not entitled to quote under the LCT Act, the input tax credit to which it is entitled is limited to 1/11 of the “car limit”.

18 The Commissioner contended, and the primary judge found, that this limitation on claiming input tax credits applied in relation to each vehicle acquired or imported by the appellant after 28 May 2016 in the relevant tax periods and to the La Ferrari.

19 The principal GST issue in relation to these vehicles is whether, when the appellant imported or acquired the relevant vehicle, it had the intention of using that vehicle for the purpose of holding it as trading stock “and for no other purpose”: s 9-5(1).

Outcome in the original jurisdiction

20 Although the LCT question concerned actual use and the GST question concerned intended future use, the parties were agreed in the original jurisdiction, and remained so on the appeal, that, on the facts of the present case, the LCT and GST questions fell to be answered in the same way. The learned primary judge accurately summarised (at [66]) the import of that agreement in apprehending that, “the central question can be summarised as whether the applicant used or intended to use each car for the purpose of holding the car as trading stock and for no other purpose”.

21 His Honour answered that question in this way:

The answer to the central question is that each car was not used for no other purpose than holding the car as trading stock. Each car was also used for the purpose of displaying the car, together with other cars, as exhibits in a museum, being operated commercially as a museum.

22 The appellant was controlled by Mr Anthony Denny, who gave evidence at trial. In [84] of his reasons for judgment, the primary judge found that:

(a) Mr Denny, and thus the appellant, “intended to trade cars through the ‘Gosford Classic Car Museum’”; and

(b) “they considered that the museum would assist in maximising the number of sales and the sale price”.

His Honour accepted Mr Denny’s evidence in this regard and considered it obvious in any event from the objective facts, “that he wanted to profit from the sale of cars and considered that the ‘museum concept’ would be the best way to achieve that objective”.

23 Notwithstanding these several findings, the primary judge was satisfied on the basis of the way in which the premises were titled and promoted, and by the charging of an entry fee, that the assessed motors vehicles were used for another purpose, which was as exhibits in a museum.

Grounds of Appeal

24 The appellant’s principal contention was that, having regard to the totality of the evidence but particularly in light of the several findings made, as noted, in [84] of the primary judge’s reasons for judgment, the number of sales and the sale price of the vehicles, the primary judge ought to have concluded that the appellant did not at any time use (or intend to use) those vehicles for “a purpose other than a quotable purpose” and thus that no increasing LCT adjustments “happened” in respect of those vehicles. On the appeal, neither party challenged the correctness of these findings.

25 The appellant also raised issues of statutory construction. It contended that the phrase “no other purpose” in s 9-5(1) of the LCT Act “meant “no alternative purpose” rather than “no additional purpose”. It also contended that purposes which are only subsidiary, consistent with, and incidental to, the “purpose of holding a car as trading stock” do not constitute a use of those cars for an “other purpose”. The appellant promoted a like construction and alternative construction of “other than” as it appears in s 15-30(3)(c) and s 15-35(3)(c) of the LCT Act.

26 Subject to the concession noted, the essence of the Commissioner’s submission was that the appeal should be dismissed, for the reasons given by the primary judge.

Resolution of Appeal

27 Given that this was not a case where the appellant had had a decreasing LCT adjustment under s 15-30(1) of the LCT Act, the appellant was correct in its submission that, materially, the increasing LCT adjustment for which s 15-30(3) of the LCT Act provides was predicated upon the appellant already having quoted for the supply of the vehicles. This necessarily follows from the text of s 15-30(3) of the LCT Act. Having regard to the text of s 15-30 and s 15-35 of the LCT Act, the appellant’s further submission that these sections apply in circumstances where there is a “change of use” is also correct. With the exception of the La Ferrari motor vehicle, a consequence of this was that the issue before the primary judge was never one of entitlement to quote but rather one of whether, quotation already having occurred, there was a change of use.

28 The presence of the description “A New Tax System” in the title of the LCT Act is something of a misnomer. The LCT Act is just a particular type of sales tax legislation. There is nothing “new” in Australia about a sales tax. A wholesale sales tax scheme was first imposed in Australia by a series of statutes enacted by the Parliament in the 1930’s. In contrast, the LCT Act envisages a single stage tax imposed at the retail sale level. As did the earlier sales tax scheme, the LCT Act uses a system of “quoting” to defer the taxing point. Consistent with that design, s 15-30(3)(c) and s 15-35(3)(c) apply where the taxpayer has quoted to defer LCT but used the car for a purpose other than a “quotable purpose”, with the result that the revenue would otherwise be deprived of LCT on the retail sale. That result is avoided by subjecting the taxpayer to an “increasing adjustment”. There is no other, presently relevant distinction to be drawn between s 15-30 and s 15-35 of the LCT Act. It is convenient therefore hereafter to focus on s 15-30.

29 What constitutes a “quotable purpose” is defined by s 27-1 of the LCT Act to be “a use of a * car for which you may * quote under section 9-5”. In turn, of the uses specified in s 9-5 of the LCT Act, the only one of present moment is that specified in s 9-5(1)(a) of the LCT Act, “holding the car as trading stock, other than holding it for hire or lease”. Each of the uses specified in s 9-5(1) of the LCT Act is governed by a chapeau in which refers to “using the car for one of the following purposes, and for no other purpose”.

30 The use of a comma to precede the conjunctive “and” in this chapeau offers an example of a serial, sometimes termed an Oxford or Harvard comma (Macquarie Dictionary, online edition). Such a comma is traditionally used where its absence might be a source of ambiguity. As used in s 9-5(1) of the LCT Act, its purpose is to emphasise that the list of uses specified in that subsection is exhaustive. However that may be, because this case is concerned with an alleged change of use, leading to an alleged increasing car tax adjustment, the qualification as to use found in s 9-5(1) is not directly relevant. Rather, s 9-5(1) of the LCT Act supplies a list of permissible uses and thus “quotable purposes” with the question, flowing from the text of s 15-30(3)(c), being whether, on the facts, there was a use “other than” the permissible?

31 As both the Oxford and Macquarie Dictionaries (online editions) confirm, the word “other” can, when used adjectively, mean “additional” or “further”. The appellants contended for such a meaning in s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act. However, that is not the context in which the word is used in s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act. There it is used in conjunction with “than” to add a qualification. Regard to these same dictionaries discloses that, as so used, “other than” carries the meaning “besides, except, apart from”. This is the meaning it has in s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act. That meaning makes s 15-30(3)(c) harmonious with the a like qualification, “you have only used the car for a quotable purpose”, found in s 15-30(1)(e) of the LCT Act in the criteria which occasion a decreasing LCT adjustment.

32 This preferred construction of s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act is, as the primary judge (at [68]) recognised, consistent with an observation made of that provision by Jessup J in Melbourne Car Shop Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (2010) 76 ATR 42, at [35], “[t]hat question is whether the car was ever used save for the purpose of being held as trading stock.” However, the construction of that provision was not the central issue in that case, which turned on a very particular view of the facts taken by his Honour. Indeed, and with respect, to acknowledge that consistency may conceal more than it reveals about the nature and extent of the “other than” qualification in s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act.

33 The appellant made reference to Deputy Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Ellis & Clark Ltd (1934) 52 CLR 85 and Brayson Motors Pty Ltd (in liq) v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1985) 156 CLR 651, at 659 in support of a submission that the Court should read down language of apparently general application in sales tax legislation so as to give effect to an evident and narrower statutory purpose. These cases are but examples of an evident statutory purpose informing the meaning to give the text of legislation where that text admits of constructional choices. In the present case, which is concerned with trading stock, all that identifying the overall purpose of the LCT Act as to impose a single stage tax at the retail sale level does is to underscore the fiscal integrity purpose of s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act. Construing “other than” in the way just indicated serves that fiscal integrity purpose in relation to a single stage, retail sales tax.

34 The appellant’s alternative construction of “other than” was that a use of a motor vehicle which was incidental to, and consistent with, the use of holding the vehicle as trading stock for sale or exchange in the ordinary course of trade was not an “other” purpose. The appellant submitted that the result of the construction adopted by the primary judge was to, in effect, advance the taxing point in circumstances where each assessed motor vehicles was always trading stock (and was in fact sold).

35 Accepting as I do that the purpose of the LCT Act is to impose a single stage sales tax at the retail sales level, a construction of its text which leads to the imposition of that tax while the motor vehicle concerned remains held as trading stock is incongruous. Further, given that “other than” appears in a fiscal integrity measure, it is difficult to see how that purpose is served by dictating an increasing adjustment while the motor vehicle concerned remains held as trading stock.

36 These considerations tell in favour of a construction of “other than” which excludes from the qualification it imposes uses which are merely incidental or subservient to a continuing use of a vehicle as trading stock.

37 The primary judge referred, at [88], to the following statement made by Windeyer J in Randwick Municipal Council v Rutledge (1959) 102 CLR 54 (Randwick Municipal Council v Rutledge), at 94:

The words “exclusively” and “solely” are familiar in fiscal and rating law. Where an exemption from rating depends upon the use of land exclusively for a particular stated purpose, then the use must be for that purpose only … The question arises, for example, when part of the subject land is used for the relevant purpose and another part for a different purpose … The presence of “exclusively”, “solely”, or “only” always adds emphasis; and is not to be disregarded … When such words are present, it is a question of fact whether the land is being used for any purpose outside the stipulated purpose … As Kitto J said in Lloyd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation, such words confine the use of the property to the purpose stipulated and prevent any use of it for any purpose, however minor in importance, which is collateral or independent, as distinguished from incidental to the stipulated use. Even without such words, an exemption from rating based upon use or occupation for a particular purpose or in a particular manner can only apply when the property is so used that it can properly be described as used for that purpose or in that manner, any other user being merely incidental, or at least not inconsistent with such main user.

[citations omitted]

38 Having so done, the primary judge stated, at [90], with reference to the last sentence in this passage, “[t]he last sentence of that passage, and the notion of a use being “merely incidental” and “not inconsistent” with the main use, is an observation concerning statutes which do not use language such as ‘exclusively’ or ‘solely’ or, to return to the present case, a statute which states that the use must be for holding as trading stock ‘and for no other purpose’.” With respect, that statement is true only if one reads this last sentence in isolation from all that precedes it. The whole point of the statement made by Windeyer J in Randwick Municipal Council v Rutledge is that, even where the words “exclusively” and “solely” are employed in a use exemption, mere incidental uses do not take the user outside the exemption.

39 Were there any doubt about the accuracy of this understanding of Sir Victor Windeyer’s statement in Randwick Municipal Council v Rutledge, and of the accuracy of his Honour’s summation of the effect of exemptions so qualified, this should be put to rest, by reference to a case principally relied upon by the appellant, Salvation Army (Vic) Property Trust v Fern Tree Gully Corp (1952) 85 CLR 159 (Fern Tree Gully Case). The Fern Tree Gully Case was concerned with the construction of a rating exemption where the exemption was dependent upon a use “exclusively” for charitable purposes. It offers a paradigm example of an approach to construction which allows that an ordained exclusivity of purpose of use is not transgressed by the presence of a use which is merely concomitant and incidental.

40 In the Fern Tree Gully Case, at 172, after a survey of the authorities, particularly Royal Choral Society v Commissioner of Inland Revenue [1943] 2 All ER 101, the principle discerned by Dixon CJ, Williams and Webb JJ was:

If the land is used for a dual purpose then it is not used exclusively for charitable purposes although one of the purposes is charitable. But if the use of the land for a charitable purpose produces a profitable by-product as a mere incident of that use the exclusiveness of the charitable purpose is not thereby destroyed.

Particularly instructive for present purposes is their Honours’ further observation, at 173:

There is no distinction in principle between selling the surplus proceeds of a charitable activity and making a charge for supplying a charitable activity such as an educational performance or meals and beds in a hostel for the needy, yet in the case of the Royal Choral Society it was held that the fact that the performance of plays produced a profit and in Municipal Council of Sydney v Salvation Army (N.S.W. Property Trust) the fact that a charge was made in some instances for beds and meals in a hostel did not destroy the exclusiveness of the charitable purpose.

[emphasis added]

41 To like effect in Fern Tree Gully Case to these passages are observations made by Fullagar J, at 185 – 186.

42 The recognition, in the passage from the Fern Tree Gully Case just quoted, with reference to Municipal Council of Sydney v Salvation Army (N.S.W. Property Trust) (1931) 31 SR (NSW) 585, that the fact that charges were on occasion made for meals and accommodation was not destructive of the continued, exclusive use of the land in question for charitable purposes is of particular significance by analogy for the resolution of the present case. It highlights the danger presented by compartmentalisation of evidence to the exclusion of what is revealed by the whole.

43 In the United Kingdom, later rating exemption case law is canvassed but to no different effect in the recently decided London Borough of Merton Council v Nuffield Health [2023] UKSC 18 (Nuffield Health). The facts of that case are instructive for present purposes. Nuffield Health was a registered charity established “to advance, promote and maintain health and healthcare of all descriptions and to prevent, relieve and cure sickness and ill health of any kind, all for the public benefit.” Among other things, it operated 112 fitness and wellbeing centres, including one at Merton Abbey. Its use of Merton Abbey proved controversial for rating exemption purposes. The facilities at Merton Abbey were primarily available to fee-paying Nuffield Health gym members. Nuffield Health acquired Merton Abbey on 1 August 2016, when it bought the business of Virgin Active. It applied to the London Borough of Merton Council for mandatory and discretionary rate relief. The application for mandatory relief was granted initially. However, following a visit by Council officers in November 2016, the Council withdrew the relief, because the membership fees were set at a level which excluded persons of modest means from enjoying the gym facilities. In the Council’s view, this meant that Merton Abbey was not being wholly or mainly used for charitable purposes (the relevant rating exemption category), because the requirement for public benefit was not satisfied. In the course of explaining why the Council’s appeal would be dismissed, Lord Briggs and Lord Sales SCJJ (with whom Lord Kitchin, Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt SCJJ agreed), stated, at [32]:

Finally, it is important to keep in mind the distinction between the fulfilment of the purposes of a charity and its lawful activities. The former is only a subset of the latter. A charity fulfils its purposes by doing what it was established to do, ie doing what it is there for. Those purposes must be exclusively charitable. In the present case that means, in a nutshell, promoting health. But most charities will also undertake incidental activities not directly concerned with the fulfilment of their purposes, but rather securing their continued existence, or their ability to survive and thrive in fulfilling their purposes. These activities may include head-office management, residential accommodation for staff, fund raising and the maintenance of an investment portfolio, any of which may include the occupation and use of real property: see Tudor on Charities, 11th ed, para 1-032.

[emphasis added]

44 The point of these several authorities, and the cases discussed in them, is that a purpose which is incidental, a means to an end, does not render a use other than an exempt use even where that exemption is conditioned upon the exempt use being exclusive or “wholly or mainly”.

45 The present case raises an important issue of principle concerning the construction of the LCT Act. When the retail sales tax purpose of the LCT Act and the integrity of revenue purpose of increasing adjustments are understood, there is every reason to construe “other than” in a like way to these charitable purpose exemption cases. So doing avoids, as I have already highlighted, the incongruity of LCT falling on trading stock available for sale and yet to be sold.

46 Adopting this approach to the construction of s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act, an analysis of the whole of the evidence discloses that the use of the assessed motor vehicles for display at a so-called “museum” was only ever a means to an end (and the same applies to the La Ferrari, even at the time of importation). The end was always their retail sale. To adopt the language of Fern Tree Gully Case, the admission fees were just a “by-product”, a “mere incident”. The appellant treated the revenue earned from car sales and admission fees as a single line item in its financial statements. In effect, the admission fees in part subsidised its retail sales operation.

47 The evidence disclosed that there were no permanent static displays; rather an always evolving offering of trading stock. Vehicles moved onto and off the display area according to maintenance requirements and their sales turnover.

48 When the appellant acquired the massive shed which had hitherto been a Bunnings Warehouse it adapted those premises for use to display its trading stock. The appellant was, after all, a licenced motor dealer.

49 Under local government zoning laws, the appellant could operate the premises as a car showroom but not as a museum in the strict sense. It sought and obtained the requisite local government approval to operate the premises in conformity with those zoning laws. Of course such local government approval is not necessarily determinative of singularity of use of the vehicles as trading stock. But it does indicate that, from the very outset, the appellant did not set out to conduct a “museum”.

50 On the evidence, the “museum concept” was the brainchild of Mr Denny. He had earlier acquired considerable experience and enjoyed great success abroad in the selling of large volumes of used motor vehicles. Mr Denny stated he had observed the marketing of vehicles at the Lincoln Hotel in Las Vegas: “A dealership had cordoned off a section of the hotel and used that section to house a collection of classic cars. The section was referred to as a ‘museum’, with the vehicles arranged to highlight the changing look of them at their different times of manufacture. However, despite the presentation all of the cars were for sale …” The primary judge did not gainsay Mr Denny’s inspiration for this “museum concept” for the sale of this boutique type of trading stock.

51 It is quite obvious on the evidence that Mr Denny caused the appellant to take up this idea on a grand scale. Moreover, it is clear to the point of demonstration that the implementation of this idea was in short order conspicuously successful in causing the retail sale of the appellant’s trading stock. In the first full taxation year of the operation of the appellant’s business, the year ended 30 June 2017, the appellant’s gross revenue in respect of the sale of its motor vehicles was $28.5 million. In contrast, and to compare like with like, its gross revenue in that same year from admission fees to its premises was $1.32 million. Over that year, the implementation of the “museum concept” by various promotional means occasioned over 100,000 persons to visit the appellant’s premises. The revenue relativities and these visitor numbers underscore the veracity of oral evidence which Mr Denny gave before the primary judge in which he stated: “[w]ithout visitors, you don’t have sales” and “[i]f you don’t have the funnel feeding into the machine, you don’t sell”. The “museum concept” was the way in which the appellant sought to, and did, bring potential buyers in touch with its trading stock.

52 Although acknowledging that he was a salesman and in fact sold cars, the primary judge (at [19]) apparently found the title “curator” given by the appellant to an employee (on the evidence, Mr Ken Grindrod) at the “museum” supportive of his conclusion that there was a use of the assessed motor vehicles “other than” as trading stock. Yet the evidence also showed that, via Mr Grindrod, the appellant sold many high value cars ranging from a Ferrari F40 (stock #1172) for $1,800,000 to an Aston Martin DB5 (stock #1740) for $1,560,000 to a Ferrari Testarossa (stock #1227) for $165,000. When one analyses the whole of the evidence, the title “curator” given to Mr Grindrod is just an aspect of the appellant’s overall promotional strategy for the retail sale of its boutique stock of motor vehicles. In reality, he was one of the appellant’s top car salesmen.

53 The position in relation to such a title is no different to the operator of a “fine art gallery” specialising in the sale of valuable, modern Australian art affording one of its staff the title of “Curator of Australian Art”. That person may have a great depth of knowledge of the life and works of, for example, Charles Blackman or Ray Crooke, some of whose works are on display and offered for sale at the gallery. One reason for that person’s employment may be because of that knowledge. Indeed, as part of its marketing strategy, the operator of the gallery may promote either generally or to a select clientele (or both) a lecture and related viewing at its premises by this “curator” on the life and works of such an artist. That may perhaps be in conjunction with a specially curated, retrospective exhibition of examples the artist’s work, with each of the displayed works being on sale. Perhaps fine wine and canapés are offered to attendees. None of this means that if, on viewing a displayed artwork, an attendee sits down with that employee in order to complete the sale of one of those displayed, this “Curator of Australian Art” is not in substance a salesman or that the “gallery” is not in substance a retail art dealership.

54 To focus, with respect, as did the primary judge, and in submissions the Commissioner, on aspects of promotional literature, staff titles and display in isolation is to fail to discriminate between an overarching end and its incidental means. This is exactly the same type of error made again and again by revenue and rating authorities, as revealed in the charitable purposes exemption cases. That is not to say that, as a matter of initial impression, engendered by both the name “museum” and the related “museum concept” measures, there is not a certain attraction in a conclusion that the motor vehicles were used (or intended to be used) other than as trading stock, only that such a conclusion does not survive the objective analysis of the whole of the facts and the related discounting, dictated by the true construction of s 15-30(3)(c) of the LCT Act, of incidental or subservient uses.

55 Given the way in which the parties accepted that both the LCT and GST issues in the case fell for resolution, what follows from the foregoing is that the appeal should be allowed, with costs.

I certify that the preceding fifty-five (55) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Logan. |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

WHEELAHAN AND HESPE JJ:

56 This appeal concerns the appellant’s liability to goods and services tax (GST) and luxury car tax for the tax periods from June 2016 to November 2017 in respect of 40 cars acquired by the appellant and displayed at the Gosford Classic Car Museum (the Museum), which was owned and operated by the appellant. The appellant’s liability turns on whether the appellant used the cars for a purpose other than a “quotable purpose” as defined in the A New Tax System (Luxury Car Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (LCT Act) and, in particular, whether the appellant used each of the cars for the purpose of holding the car as trading stock, other than holding it for hire or lease, and for no other purpose.

57 The Commissioner conceded that each of the cars was held by the appellant as trading stock. The issue is whether, by displaying the cars at the Museum, the cars were used “for no other purpose”.

Facts

58 The primary judge’s findings are set out at PJ [1] to [53]. The primary judge described the Museum in some detail.

59 On appeal, the appellant drew attention to the genesis of the Museum. The premises it occupied were formerly used as a Bunnings warehouse. In undertaking the modification of those premises, a consultant was retained in order to obtain necessary council approvals. In the Complying Development Certificate issued in July 2015 by the consultant, the scope of the works was described as “Adaptive Re-use – Change & Establishment of Use – Class 5, 6, 7 & 8 Former BBC Hardware Store to a Class 5, 6 & 7 Heritage & Prestige Motor Vehicle Display Showroom + Storage + Sales Yard & Related Sales & Hire Offices & Public Facilities”. A modification to the complying development certificate in October 2015 added a “Memorabilia Outlet Shop + Associated Client Café + Public Entry Facilities to Museum”. A further revision in May 2016 provided for a “Revised Memorabilia Outlet Shop” and “External AIR STREAM Client Café”.

60 The site of the Museum was zoned Industrial 1 which, under the Gosford Local Environment Plan 2014 (the Plan), meant it was zoned as General Industrial. Uses of the land permitted with consent included “Vehicle sales or hire premises”. The term “Vehicle sales or hire premises” was defined by the Plan to mean “a building or place used for the display, sale or hire of motor vehicles, caravans, boats, trailers, agricultural machinery and the like, whether or not accessories are sold or displayed there”. Prohibited uses of land zoned General Industrial included “Commercial premises” and “Information and education facilities”. The permitted use for “Vehicle sales or hire premises” was an exception to the prohibited uses.

61 A schedule to the appellant’s policy of industrial special risks insurance dated 23 January 2017 described the business conducted by the appellant as “[p]rincipally a Vintage Vehicle Museum, dealership, ancillery [sic] workshop including detailing, head office, Mobile Coffee Van (TP Operated), Storage of memorabilia & merchandise for sale in online store and any other activity incidental thereto”. In a subsequent renewal for the period 30 June 2017 to 31 December 2018, the schedule of insurance dated 9 February 2021 described the business as “[p]rincipally a Vintage Car Dealership, including showroom”. Mr Denny attributed the date on this schedule to the date it was likely printed.

62 Mr Denny controlled the appellant. Mr Denny had successfully operated a motor vehicle dealership business in Europe, comprising some 40 sales dealerships and selling primarily used vehicles. The dealerships used a range of marketing activities, which included using café lounges, cinemas or golf-practice driving ranges at dealerships.

63 In about 2013, Mr Denny came across what he “thought was a particularly clever and novel way of marketing vehicles at the Lincoln Hotel in Las Vegas”. A dealership had cordoned off a section of the hotel and used that section to house a collection of classic cars. The section was referred to as a “museum”, with the vehicles arranged to “highlight the changing look of them at their different times of manufacture”. Hanging above each row of the display were signs that read:

The Auto Collections. All of the automobiles you are currently viewing are “FOR SALE”. Please ask a sales representative for assistance THANK YOU.

64 Mr Denny considered that “there was a certain panache attached to buying a luxury vehicle from such a display” as it “gave the impression of each of the vehicles displayed having a greater provenance and value than they might otherwise have”. He formed the view that:

any potential purchaser looking at these vehicles, placed within premises containing a number of other distinguished vehicles, would be more likely to be immediately impressed with the vehicle and more willing to buy at a higher price.

It was his view that presenting the vehicles for sale “in what would be called a ‘museum’” would “differentiate [his] dealership from the rest of the market and achieve premium prices for the vehicles for sale”. He also “thought using the term ‘museum’ in the proposed business name would pique interest in the dealership both in Australia and, as importantly, overseas”.

65 The appellant was licensed in New South Wales as a motor vehicle dealer. Its licence disclosed its place of business as including the Museum premises address. As the holder of a motor dealer’s licence, it was an offence under the Motor Dealers and Repairers Act 2013 (NSW) s 48(1) for the appellant to offer or display a motor vehicle for sale at a place other than notified premises.

66 In around 2014, Mr Denny decided to move back to Australia to establish a “second hand motor vehicle dealership business primarily dealing in exclusive ‘high‑end’ classic and luxury cars”.

67 Between 22 May 2015 and 27 June 2020 the appellant sold over 800 vehicles with an average margin of $9,141. The Museum commenced operation on 28 May 2016. Both before and after the opening of the Museum, there were instances of cars being sold for prices in excess of $900,000.

68 Each of the cars the subject of the dispute was assigned a stock number (as were each of the other cars held by the appellant) and the appellant maintained books and records which recorded potential sale prices for the cars. Each car was treated by the appellant as trading stock in the appellant’s income tax returns and accounting records.

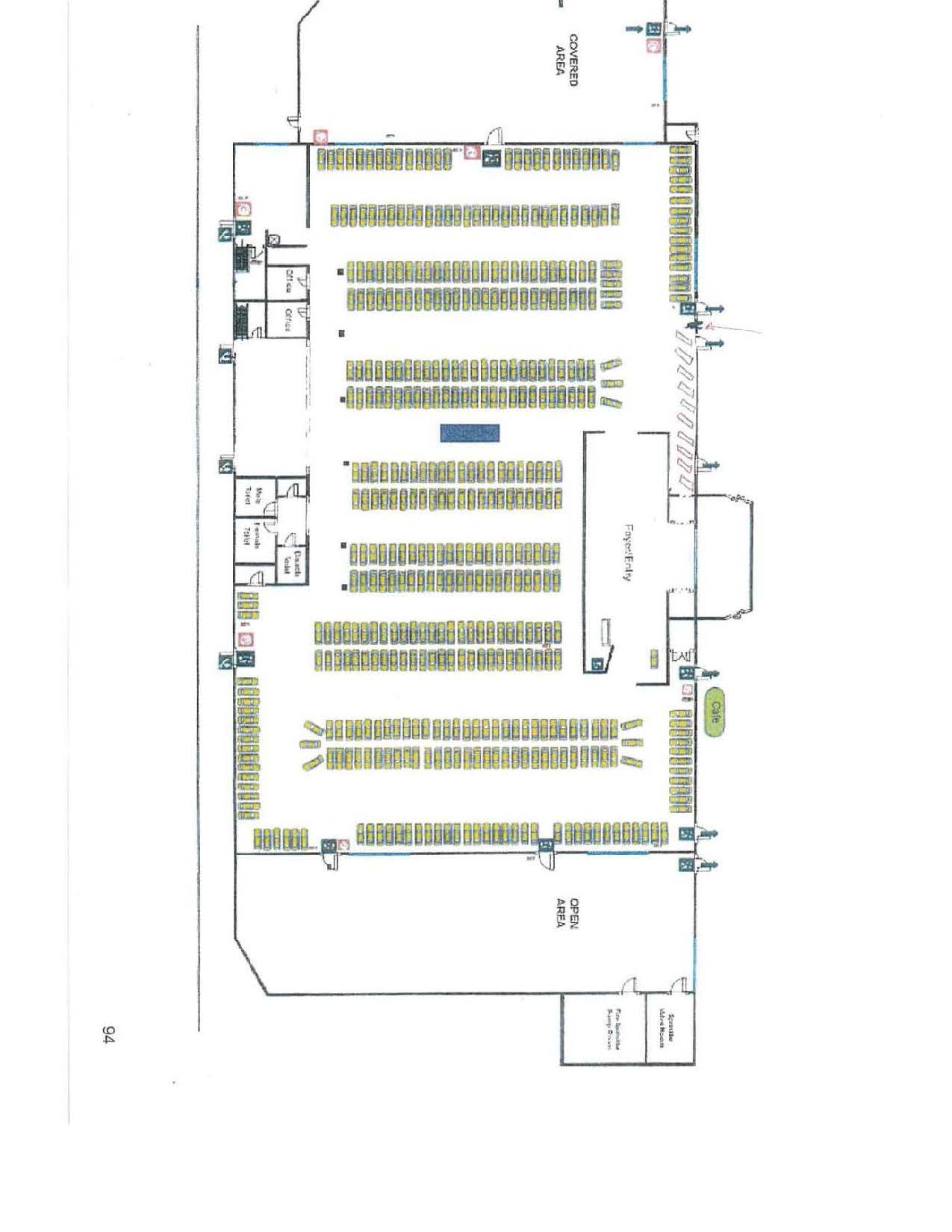

69 A floorplan of the Museum is reproduced as Annexure A.

70 Mr Denny’s oral evidence was that, by increasing visiting rates, he increased sales because “[w]ithout visitors, you don’t have sales” but, to avoid being a “typical used car dealer”, he refrained from describing the Museum as “a showroom with cars for sale”. The Museum was “about making money… It’s all about moving the metal, selling the cars”.

71 Under s 63 of the Motor Dealers and Repairers Act 2013 (NSW), it is an offence for a motor dealer to offer or display for sale a second hand motor vehicle unless a dealer’s notice (prescribed by regulation as a Form 5) is attached to the motor vehicle. Prior to 6 April 2017, there was a sign on at least some of the cars in the central area saying “cars are not for sale”: PJ [50]. There was a Form 5 on the back passenger seat or back window of each car in the main area of the Museum, not visible to visitors to the display: PJ [48]. The cars in the caged semi-outdoor area were signed as “for sale” with prices displayed on each car: PJ [50].

Statutory framework

Luxury car tax

72 Luxury car tax is a single stage tax that is imposed on supplies and importations of luxury cars. The tax is calculated on the value of the car that exceeds the luxury car tax threshold: LCT Act s 2-1.

73 There is a system of quoting which “is designed to prevent the tax becoming payable until the car is sold or imported at the retail level”: s 2-5.

74 Luxury car tax is payable on a taxable supply or taxable importation of a luxury car: ss 5-5 and 7-5. A taxable supply is not made if the recipient quotes for the supply of the car or if the car is more than two years old: s 5-10(2). In the case of a car that is imported, a car is more than two years old if the car was entered for home consumption more than two years before the time of supply: s 5-10(3)(b). A taxable importation is not made if the importer quotes for the importation of the car: s 7-10(3)(a).

75 Section 9-5 sets out the circumstances in which a person is entitled to quote in relation to a supply or importation of a luxury car. It relevantly provides:

9‑5 Quoting

(1) You are entitled to *quote your *ABN in relation to a supply of a *luxury car or an *importation of a luxury car if, at the time of quoting, you have the intention of using the car for one of the following purposes, and for no other purpose:

(a) holding the car as trading stock, other than holding it for hire or lease; …

…

(2) However, you are not entitled to *quote unless you are *registered.

76 If a person quotes in circumstances in which the person is not entitled to quote, the quote is nevertheless effective for the purposes of ss 5-10(2)(a) or 7-10(3)(a) unless s 9-25 applies: s 9‑20. Section 9‑25 applies if, at the time of the quote, the person to whom the quote is made has reasonable grounds for believing, amongst other things, that the person quoting was not entitled to quote in the particular circumstances.

77 However, the LCT Act provides for adjustments to be made if circumstances occur that mean that too much or too little luxury car tax was imposed. Section 15-30(3) relevantly provides:

15‑30 Changes of use—supplies of luxury cars

…

(3) You have an increasing luxury car tax adjustment if:

(a) you were supplied with a *luxury car; and

(b) …

(i) no luxury car tax was payable on the supply because you *quoted for the supply; …

(ii) … and

(c) you use the car for a purpose other than a *quotable purpose.

78 Section 15-35(3) relevantly provides:

15‑35 Changes of use—importing luxury cars

…

(3) You have an increasing luxury car tax adjustment if

(a) you *imported a *luxury car; and

(b) …

(i) no luxury car tax was payable on the importation because you *quoted for the importation; …

(ii) … and

(c) you used the car for a purpose other than a *quotable purpose.

79 “Quotable purpose” is defined in s 27-1 to mean “a use of a *car for which you may *quote under section 9-5”.

80 In the present case, the appellant was registered for the purposes of the LCT Act and quoted for the supply or importation of the 40 cars. The Commissioner did not contend that s 9-25 applied. Accordingly, no luxury car tax was payable on the supply or importation, irrespective of whether the appellant was entitled to quote. In so far as the LCT Act is concerned, the issue was whether the appellant had “increasing luxury car tax adjustments” under ss 15-30 and 15-35 of the LCT Act. The issue turns on whether each of the 40 cars was used for a purpose other than a “quotable purpose”.

GST Act

81 As the primary judge explained at PJ [60], s 69-10 of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (GST Act) limits the amount of input tax credits to which a person is entitled to no more than 1/11th of the luxury car tax “car limit”, in circumstances where the person is not entitled to quote for the purposes of the LCT Act in relation to the supply or importation. Section 69-10(1) of the GST Act provides:

69-10 Amounts of input tax credits for creditable acquisitions or creditable importations of certain cars

(1) If:

(a) you are entitled to an input tax credit for a *creditable acquisition or *creditable importation of a *car; and

(b) you are not, for the purposes of the A New Tax System (Luxury Car Tax) Act 1999, entitled to quote an *ABN in relation to the supply to which the creditable acquisition relates, or in relation to the importation, as the case requires; and

(c) the *GST inclusive market value of the car exceeds the *car limit for the *financial year in which you first used the car for any purpose;

the amount of the input tax credit on the acquisition or importation is the amount of GST payable on the supply or importation of the car up to 1/11 of that limit.

82 In so far as the GST Act is concerned, the issue is whether the amount of input tax credits which the appellant could claim was limited by s 69-10 of the GST Act. This issue turns on whether the appellant was entitled to quote under s 9-5 of the LCT Act.

The decision of the primary judge

83 Before the primary judge, the parties accepted that the LCT Act issue turned on whether, by being displayed in the Museum, each of the 40 cars was used for a purpose other than holding the car as trading stock, for the purposes of s 9-5(1). The parties also accepted that, on the facts of the present case, the GST issue was to be resolved on the same basis, notwithstanding that the GST issue was concerned with the entitlement to quote which is to be determined by the intended use at the time of quoting rather than actual use: PJ [66].

84 The primary judge concluded that each car was not used for no purpose other than holding the car as trading stock. Each car was also used for the purpose of displaying the car together with other cars, as exhibits in a museum, being operated commercially as a museum: PJ [67].

Appellant’s submissions

85 The appellant submitted that the primary judge erred in his conclusion both as a matter of statutory construction and as a finding of fact based on the evidence.

86 The appellant submitted that the primary judge erred (at PJ [68]) in construing the phrase “no other purpose” in s 9-5(1) as meaning “no additional purpose” rather than “no alternative purpose”. It was submitted that if “no other purpose” is construed “in the sense of “no alternative purpose” then, because the Commissioner had conceded that the cars were held as trading stock, it necessarily followed that the appellant must succeed. Any other purpose was necessarily additional, and not an alternative, to the purpose of holding the cars as trading stock.

87 The appellant submitted that the LCT Act should be construed, and even read down, so as to conform with its legislative purpose, which was to impose a tax on retail sales. The appellant relied on two cases involving wholesale sales tax to illustrate the way in which courts have construed taxation legislation in light of an ascertained legislative purpose, namely Brayson Motors Pty Ltd (in liq) v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1985] HCA 20; (1985) 156 CLR 651 (Brayson Motors) and Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Ellis & Clark Ltd (1934) 52 CLR 85. The appellant contended that the primary judge failed to construe the provision in accordance with the purpose of the LCT Act, which intended the tax to be imposed only on sales or imports at the retail level (relying on s 9-1 of the LCT Act). The appellant submitted that its construction of “no other purpose” was consistent with the general policy and purpose of the LCT Act.

88 The appellant further submitted that the phrase “no other purpose” should not be construed as extending to a purpose which was subsidiary to and not inconsistent with the purpose of holding a car as trading stock. The appellant submitted that the exclusion of “other than holding it for hire or lease” suggests that holding for hire or lease would not otherwise be a disqualifying “other purpose”.

89 The appellant contended that the primary judge failed to construe ss 15-30 and 15-35 in accordance with their headings which evidenced an intention that the sections apply only where there has been a “change of use”. Having accepted that the cars in issue were always trading stock, the appellant submitted that there was no change of use.

90 The appellant contended that the legislation applies to each vehicle individually and must be tested in that way. It was submitted that as a matter of fact, having regard to the totality of the evidence, the primary judge ought to have concluded that the appellant did not use each of the cars individually for a purpose other than a quotable purpose. It was not disputed that each of the cars was held as trading stock by the appellant at all times, and the primary judge had accepted that the appellant intended to trade the cars through the Museum and did so to assist in maximising the number of sales and the sale prices. The appellant’s display of each of the 40 cars was a display as trading stock. The appellant did not operate a museum stricto sensu having regard to the local planning laws. The “museum” concept was no more than an innovative way to market the stock to maximise profit. The fact that an entrance fee was charged did not, it was submitted, mean that the cars were held for a purpose other than a quotable purpose. Even if a visitor did not enter with the intention of purchasing a vehicle, each visitor was a potential spruiker.

91 It is noted that, although before the primary judge the Commissioner had disputed that a particular car — the La Ferrari — had not been held as trading stock, the Commissioner conceded that issue before the Full Court.

Consideration

92 The issue is whether each of the cars in dispute was used for a purpose other than for the quotable purpose of holding the car as trading stock, other than holding it for hire or lease, and for no other purpose. The operative terms of s 15-30 do not refer to a change in the use made of a car since the time of quotation or supply of the car but refer to use for a purpose other than a “quotable purpose” which in turn is defined to mean “a use … for which you may *quote under section 9-5”. The heading to s 15-30 does not inform the construction of s 9-5.

93 We do not accept the appellant’s construction of “and for no other purpose” as requiring the other purpose to be exclusive or alternative to the purpose of holding the cars as trading stock. That construction is not consistent with the ordinary reading of the phrase. It is not consistent with the use of the conjunctive “and”. Most importantly, it renders the phrase “and for no other purpose” otiose. The phrase “and for no other purpose” is to be read as “solely” or “only”. Such a reading is also consistent with paragraph 1.10 of the explanatory memorandum to the bill which became the LCT Act (A New Tax System (Luxury Car Tax) Bill 1999), and which relevantly provided:

Registered entities may quote in relation to the supply or importation of a luxury car. The quoting system is designed to avoid the tax becoming payable until the car is sold or imported at the retail level. Generally, a recipient is entitled to quote if the car supplied to them is expected to be held solely as trading stock.

(Emphasis added.)

94 The presence of the phrase “other than … for hire or lease” to qualify the concept of trading stock does not require the phrase “and for no other purpose” to be read otherwise than as “solely”. In respect of the exclusion, “other than … for hire or lease”, the explanatory memorandum stated (at [5.9]) that “luxury car tax is not payable if the registered recipient intends to use the car as trading stock unless it is held for hire or lease”. There is UK authority for the proposition that, if a taxpayer carries on a single trade of trading in and hiring out goods, profits from the sale of any of the goods are taxable in the same way as sales of stock in trade: Gloucester Railway Carriage and Wagon Company Ltd [1925] AC 469 at 474–475 (Lord Dunedin), cited in Spriggs v Commissioner of Taxation [2009] HCA 22; (2009) 239 CLR 1 at [60], fn 58 (French CJ, Gummow, Heydon, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ). It follows that as a matter of ordinary language or usage, and depending upon context, such goods are capable of being regarded as trading stock. The exclusionary words “other than … for hire or lease” in s 9-5(1)(a) have the effect of ensuring that goods held for such a hiring purpose would not be considered to be held as trading stock. Read against this background, the phrase “other than … for hire or lease” qualifies those vehicles which may be regarded as “trading stock” and therefore not subject to the tax.

95 The primary judge was correct (at PJ [72]–[75]) in distinguishing Brayson Motors. The LCT Act does not define a “retail” sale. The operative provisions of the LCT Act permit a deferral of tax in the circumstances that are identified by the text of s 9-5(1)(a). There is no basis for importing into that provision the idea of taxing only a “retail sale” when that is not a concept that is defined by or imported into the legislation.

96 In referring to “no other purpose”, s 9-5(1) does not by its terms distinguish between a dominant or main purpose, and a subsidiary purpose. As Windeyer J said in Council of the Municipality of Randwick v Rutledge (1959) 102 CLR 54 (Randwick) at 93–4:

The words “exclusively” and “solely” are familiar in fiscal and rating law. Where an exemption from rating depends upon the use of land exclusively for a particular stated purpose, then the use must be for that purpose only. The question arises, for example, when part of the subject land is used for the relevant purpose and another part for a different purpose. The presence of “exclusively”, “solely”, or “only” always adds emphasis; and is not to be disregarded. When such words are present, it is a question of fact whether the land is being used for any purpose outside the stipulated purpose. As Kitto J. said in Lloyd v. Federal Commissioner of Taxation, such words confine the use of the property to the purpose stipulated and prevent any use of it for any purpose, however minor in importance, which is collateral or independent, as distinguished from incidental to the stipulated use.

(Citations omitted.)

97 The language used by Kitto J in Lloyd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1955) 93 CLR 645 at 671, which Windeyer J cited in the above passage in Randwick, is instructive. See too Ryde Municipal Council v Macquarie University (1978) 139 CLR 633 at 646–7 (Stephen J).

98 The question that the statute invites here is whether holding the cars as trading stock was the only purpose for which the cars were used. As Windeyer J identified in Randwick, it is a question of fact whether the cars were being used for a purpose other than as trading stock, including uses that were incidents of use as trading stock.

99 The term “trading stock” is not defined in the LCT Act. It takes its ordinary meaning. Goods are held as trading stock if held by a trader for the purposes of sale or exchange in the ordinary course of trade: Commissioner of Taxation v Suttons Motors (Chullora) Wholesale Pty Ltd [1985] HCA 44; (1985) 157 CLR 277 at 281–2 (Gibbs CJ, Wilson, Deane and Dawson JJ). See too Melbourne Car Shop Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2010] FCA 373; (2010) 76 ATR 42 at 51 [23] (Jessup J); Stallion (NSW) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [2019] FCA 1306; 2019 ATC 20-707 at 22,036 [245] (Thawley J). The Commissioner conceded that all the cars were held for the purpose of resale and therefore were held as trading stock. The issue is only whether, in addition to being held as trading stock, they were held for some “other purpose”. Was the use of the cars as displays in the Museum a further or additional use to their being held as trading stock, or was the use of the cars as displays in the Museum no more than part of their being held as trading stock?

100 The question is not whether the use of each of the cars as part of a display at the Museum was a subsidiary or ancillary purpose, or collateral to the purpose of holding each car as trading stock. Rather, the question is whether the use of each of the cars as part of such a display was an incident of holding that car as trading stock, such that its display was part of its use as trading stock and was part of a singular purpose. The issue is therefore one of fact and degree.

101 It may readily be accepted that displaying an item for sale is an incident of holding that item as trading stock. An item of trading stock is not held for an additional purpose merely because it is displayed on a shop shelf or in a shop window, rather than held in the shop’s storage room. A car does not cease to be used solely as trading stock merely because it is displayed in a car dealership showroom. It may also be accepted that the mere deployment of a novel (as opposed to conventional) manner of displaying cars does not result in any particular car being held for a purpose other than as trading stock.

102 However, the nature of and manner in which the cars here were displayed went much further than simply displaying the cars as for sale in a showroom in a novel way to appeal to a niche market. The display of the cars achieved a commercial end in and of itself by attracting as many visitors as possible. The nature of the display was that of an exhibition marketed to visitors as a destination in and of itself. The entrance fee charged was more than nominal. Adults were charged $20 each and $12 for each child. Family tickets were $55. The primary judge rejected Mr Denny’s evidence that the charging of the admission fee was to discourage tyre kickers: PJ [80]. About one year after it opened, the Museum attracted its 100,000th visitor, and the display of the cars by the Museum generated in excess of $1.32 million in admission fees in its first full financial year of operation. Fees were also charged for external parties to stage events such as corporate functions at the Museum. Although the appellant sought to emphasise that the Museum operated at a loss, the evidence of such a loss was based entirely on a marked up notation by the in-house bookkeeper to a draft Australian Taxation Office (ATO) document which read “[f]or the nine months to 31 March 2017, income from admissions and merchandise sales totalled approximately $1.036m, with associated overheads and operational expenses totalling approximately $1.066m”. The “associated overheads” were not identified nor was their basis of allocation.

103 A Statement of Environmental Effects prepared in November 2017 for Mr Denny in support of a proposal for the further development of the site described the existing use of the site as:

The Gosford Classic Car Museum was established in 2016, and is one of the 5 largest privately-owned car museums in the world, and is the largest in Australia and the Southern Hemisphere. The museum houses over 400 rare and classic cars from Australia and across the world, with a value of approximately $70 million. The museum is a major attraction for the Central Coast, and attracts visitors from locally, within NSW, from interstate and internationally, with up to 2,500 visitors per week. Visitors are from all ages and backgrounds, and the Museum is particularly popular for car enthusiasts and their partners and families and also for car clubs.

The dominant existing use of the site is for the display of classic motor vehicles, and most vehicles in the museum are available for sale, and a dedicated area at the rear of the museum building is used for the sale of specific vehicles, and classic car auctions are also run from the site. Within the car museum building there is also a merchandise shop, café seating area, administration office, sales office and repairs and maintenance are carried out on the display cars. The car museum currently has 32 employees.

104 The proposal contemplated the construction of an additional building on the eastern side of the Museum building which was to include a dedicated “car showroom” which was described as:

The car showroom will display, and offer for sale, classic and high-end motor vehicles, including some vehicles currently on display in the museum. Most vehicles in the car museum are available for sale, and the showroom will offer a dedicated area for this to occur, and also for the sale of other luxury cars. The showroom will be located within the building on Levels 1 and 2, with an internal vehicle lift being provided to these floors. The showroom will be lit internally at night, and will be a feature of the building’s presentation to Manns Road. Car showrooms are a permitted use on the land.

105 As the primary judge found at PJ [10] and [12]–[14], the Museum was marketed as a tourist or visitor destination, and offered a shuttle service and parking for buses. The Museum patrons covered a wide demographic, including families with children, retirees and young people. The appellant promoted its Museum as a tourist attraction to the public generally, including through its website and by social media. It had marketing staff whose role was to promote the Museum and who invited media to attend with a view to promoting the Museum as a tourist attraction.

106 The Museum had an extensive memorabilia shop selling, amongst other things, the Museum’s own branded merchandise, and housed a diner. The appellant represented the exhibition of the collection to the public as a destination or place for “car lovers”. Patrons were encouraged to photograph themselves with some of the exhibits and publish the photographs on social media. People were encouraged to come and be seen with the collection of cars. That was the commercial end secured by the Museum.

107 Each of the cars formed part of a “curated collection”: PJ [17]. Mr Denny’s marketing strategy was to make the cars appear more appealing because they had been part of a curated collection. Up until around October 2016, the website did not state that the cars at the Museum were for sale: PJ [21]. Prior to the ATO raising questions in February 2017, there was no signage making it clear that the cars in the main display area of the Museum were for sale. The absence of such signage at that time was consistent with Mr Denny’s desire to create an impression that the Museum was not a car saleyard. Prior to April 2017, only the cars in the separate area at the eastern end of the site had signage making it clear the cars in that area were for sale: PJ [48]–[51]. That only some of the cars were clearly signed as for sale is also consistent with the representations made on the appellant’s website from around October 2016 that “[w]ith so many exceptional vehicles on the museum floor” there was stock that exceeded the appellant’s “direct needs” and these classic cars were available for purchase: PJ [22]–[23].

108 As the primary judge said at PJ [78], the statutory question is not why the appellant engaged in the activities it did. Motive is different from purpose. The motive for a person’s conduct is the person’s reason for engaging in it. By contrast, the purpose of a person’s conduct is the end that is sought to be accomplished by it: Commissioner of Taxation v Sharpcan Pty Ltd [2019] HCA 36; (2019) 269 CLR 370 at 400 [49] (Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Nettle and Gordon JJ), citing News Ltd v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Ltd [2003] HCA 45; (2003) 215 CLR 563 at 573 [18] (Gleeson CJ).

109 Mr Denny’s motive in having the appellant display the cars in the manner it did may well have been to “move the metal” and to secure as high a price as possible for the cars. Mr Denny realised his subjective intention of making the cars appear more desirable to potential purchasers of the cars by exhibiting each of the cars as part of a curated “museum” collection to be seen by as many people as possible. The rotating and continually changing exhibition was intended to draw patrons beyond those interested in, or potentially interested in, purchasing a vehicle in stock. The end sought to be accomplished by displaying each of the cars as part of a collection in premises advertised as a “museum” was to attract visitors to the collection, whether they be potential purchasers or not and irrespective of whether they personally were likely to promote to others the sale of the cars. The collection attracted up to 2,500 visitors per week, typically attracting between 1,000 and 2,000 visitors per week. By contrast, the Museum received 10 to 15 sales inquiries per week (PJ [43]), some from overseas customers via the internet. The visitors were not spruikers who would, in turn, promote to others the sale of the cars. The visitors were there as visitors to the display.

110 The purpose for which the cars were used is ascertained by an objective consideration of the totality of the facts and circumstances. Although, on their own, the provision of facilities such as a café or an outlet offering memorabilia do not and cannot determine the purpose for which each of the cars was used by the appellant, the existence of those facilities in conjunction with the charging of a real and not a token entrance fee, the engagement of employed and volunteer staff to provide guidance and information to visitors, and the marketing of the exhibited collection of cars as a tourist or visitor destination is not consistent with a conclusion that the cars were used for the purpose of being held as trading stock and for no other purpose. Whatever Mr Denny as the controlling mind of the appellant thought he was doing, or whatever character might be attributed to the use of the premises for local government purposes, and irrespective of whether the premises constituted a museum stricto sensu, the scale and nature of the appellant’s activities resulted in each of the cars being held as more than trading stock.

111 We would dismiss the appeal. Although it would have been preferable for the issue of the La Ferrari to have been conceded earlier, the issue in respect of the La Ferrari ultimately turns on the same point as that decided in relation to the other cars assessed. The primary judge’s order as to costs should not be disturbed.

I certify that the preceding fifty-six (56) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Wheelahan and Hespe. |

Associate:

Dated: 11 August 2023

ANNEXURE “A”