Federal Court of Australia

Taylor v Nationwide News Pty Limited [2023] FCAFC 117

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent BRENDEN HILLS Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 25 July 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT

Introduction

1 The appellant sued Nationwide News Pty Ltd and its reporter, Mr Brenden Hills (together, the respondents) for defamation in respect of a “special report” published on 23 June 2019 in The Sunday Telegraph.

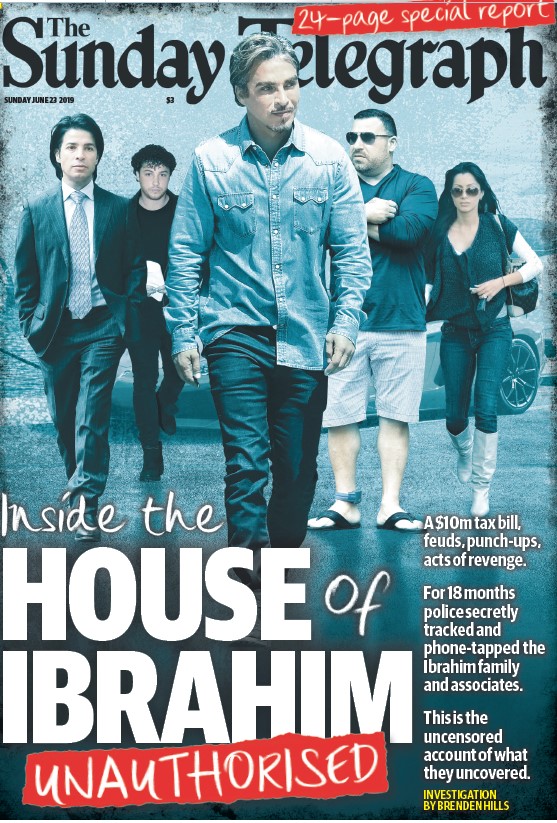

2 The appellant brought the proceeding under the surname “Taylor”. That is his mother’s surname. He swore an affidavit below in which he referred to himself as “Daniel Taylor aka Daniel Ibrahim” and “Daniel Taylor”. He also deposed that in 2007 he “adopted” his father’s surname (Ibrahim).

3 The appellant pleaded that the matter complained of contained three defamatory imputations, namely that he is a mobster; a member of the mafia; and a criminal involved in organised crime.

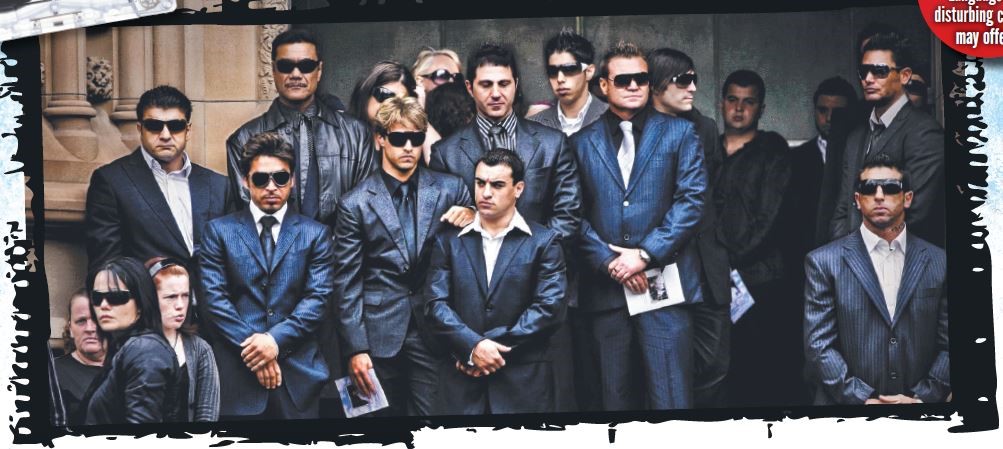

4 The primary judge found that none of the three imputations pleaded by the appellant was conveyed as a matter of fact, and dismissed the proceeding with costs. See Taylor v Nationwide News Limited [2022] FCA 149; (2022) 404 ALR 266.

5 The appellant now appeals, contending that the primary judge erred in failing to find that each pleaded imputation was conveyed, in substance because she adopted an incorrect approach to assessing how the ordinary reasonable reader of the report would have read it.

6 The appellant also contended that the primary judge was wrong to have concluded that there was no substantive difference between any of the three pleaded imputations. That issue was said to arise only if the first ground succeeded as to one or more imputation.

7 For the reasons set out below, we are of the view that there is no merit in the first ground of appeal; that the second ground does not arise; and that the appeal is therefore to be dismissed, with costs.

The matter complained of

8 The matter complained of constituted a series of so-called “articles” published under the banner “Inside the House of Ibrahim: Unauthorised” in a 24-page “special report” (the report). It was described as an “uncensored account” of the Ibrahim family. It was written by the second respondent.

9 The report was contained in a “wraparound.” That is to say, as the primary judge put it at [8], “the front page of the publication was also the front page of the newspaper and the last page of the publication the last page of the newspaper. This design would enable the uninterested reader to remove it easily and discard it and the interested reader to put it to one side and read it at his or her leisure”.

10 The articles were based, in considerable part, on the contents of recordings of intercepted telephone conversations, and other surveillance material, obtained as part of a covert police investigation, which were later tendered in proceedings in a New South Wales court, and made available to the respondents.

11 The report was also published online, and promoted on Facebook and Twitter.

12 Because a principal complaint made by the appellant is that the primary judge did not read the report as a whole, it is necessary to set out the contents of the report in these reasons in considerable detail.

13 This is a reproduction of the front page (the appellant is depicted at the rear of the montage, second from the left):

14 This is a reproduction of page 2. The appellant is described as “key player” number 5:

15 Page 3 is headed “A FAMILY AFFAIR”. Above that heading there appears this photograph, with a caption that reads: “THE ENTOURAGE: This photo taken at the 2009 funeral of Todd O’Connor at St Mary’s Cathedral showing John Ibrahim, his then bodyguard Tongan Sam and other associates became a signature image of the family and added to the mystique and notoriety of patriarch John”:

16 A subheading reads (in capital letters): “When Michael Ibrahim pleaded guilty to drug charges he lifted the lid on a collection of phone taps, photos and videos that give an extraordinary insight into a dark world, Brenden Hills reports”. The following text next appears:

FOR three decades, Sydney has regarded the House of Ibrahim with fear and fascination. Now, for the first time, we take you inside the private world of this complicated family thanks to an enormous cache of surveillance material tendered to a NSW court.

There are more than 880 phone calls and texts that were covertly recorded by police over more than a year revealing the truth about feuds, grudges and family lore, including the secret tunnel under patriarch John Ibrahim’s Eastern Suburbs mansion.

There are hundreds of police photos taken inside Ibrahim homes during police raids, and an even larger collection of surveillance photos taken by police tailing family members and associates through the city’s streets.

The material sheds new light on the family’s networks reaching beyond brothers John, Fadi, Michael and Sam to the far reaches of entertainment, night-life, property and crime. On their private calls, the brothers and their associate detail their rivalries and power struggles, as well as moments of “us against the world” camaraderie and black humour.

And, of course, there are fights over money. How did we come to this?

By 2015, the public fascination with the Ibrahim family was dying down.

John was stepping away from the nightclub game that made him rich, and moving into the less sexy property business. Fadi Ibrahim was struggling with the physical wounds of his 2009 shooting by an unknown assassin in his own driveway.

Memories were fading of 2010[’]s Underbelly: The Golden Mile television series which immortalised John’s rise to control the Kings Cross party scene.

Two things reinvigorated the public fascination.

The first, in July 2017, was the publication of John’s autobiography, a first-hand account of his acquisition of wealth and power, thumbing his nose at the police who’ve tried unsuccessfully for years to connect him with criminal activity.

Weeks after the book’s release, the second spike occurred: John’s house was raided and two of his brothers were arrested for various roles in what police allege was a massive drug and tobacco smuggling syndicate.

John was not charged and there is no suggestion he was involved in any criminal behaviour.

Michael Ibrahim has pleaded guilty and is in the process of negotiating what he will admit to in the operation that smuggled almost two tonnes of premium drugs to Australia and hundreds of thousands of illegal cigarettes.

When Michael pleaded guilty, a trove of documents, including intercepted phone calls, was tendered to court as part of the brief of evidence.

Fadi Ibrahim has pleaded not guilty to financing one [of] the tobacco shipments and is preparing to go to trial.

The syndicate was brought undone by the work of a single undercover cop who infiltrated their network of friends, family and alleged criminal cohorts.

Operating behind the scenes were an enormous team of police who tapped phones and spent months on stake-outs. In August 2017, police raided several Ibrahim properties in the execution of a series of arrests across three continents and began handing up their evidence to the criminal justice process. The result was this: an unprecedented look inside the House of Ibrahim.

PHONE TAPS, TAPE RECORDER STAR OF OLD FASHIONED STING

THE more than 860 tapped calls and texts from the phones of members of the Ibrahim clan were the second component of one of Australia’s most successful undercover stings. They complemented the work of one of Australia’s most daring undercover cops, who befriended Ibrahim confidante Ryan Watsford and then Michael Ibrahim.

While the undercover met his targets in person, a team of Australian Federal Police officers were listening in to the phone calls made by several of his targets. The Sunday Telegraph has written extensively about the undercover investigation.

Known as Operation Veyda, the investigation began in March 2016 and documents tendered to court said the initial targets were Michael and Watsford. When his work was done, this single agent – armed with nothing but the recording device – was responsible for the arrest of more than 20 people, including several Mr Bigs of the narcotics industry.

All up, the criminal syndicate allegedly conspired to import almost two tonnes of drugs and millions of black market cigarettes to Australia from the Middle East and Europe.

The undercover was so convincing, that Michael vouched for him with a high ranking bikie: “This guy ... he’s like a brother to me.”

The undercover was even invited to an Ibrahim family getaway in Thailand.

In August 2017, the undercover’s work was done and arrests made.

This liftout features the evidence you haven’t heard of or read before.

17 Pages 4 and 5 have two headings. The first is “MICK’S PICKS FROM THE EDITOR”. Mr Mick Carroll is the editor of The Sunday Telegraph. His “pick” was of the top five articles in the report, headed “The punch-up”, “Kyle’s front row seat to eyebrow waxing”, “I thought he was my friend”, “I’ve been Murph-ed” and “The secret tunnel”. The second heading is “The $10m tax bill splitting the brothers”. The article goes on to explain that John Ibrahim borrowed $10 million from his brother to pay a tax debt, which “caused tension between John and his younger brother Fadi …” The article is accompanied by photographs of John Ibrahim and his wife in bathing suits “on a luxury trip to Ibiza” and his “clifftop mansion at Dover Heights”, together with a smaller photograph of “police trying to smash open a safe on his pool deck during a raid”.

18 Pages 6 and 7 are headed “THE ENTOURAGE”. A banner above the headline reads “THE DARKER SIDE OF CELEBRITY”. The subheading reads (in capital letters): “While Sydney struggles to label the Ibrahim Family, the brothers have no doubt about their celebrity”. The article likens the lives of the Ibrahim family to the characters in a television series called “Entourage”, and is accompanied by an image of members of its cast.

19 Page 7 also contains a heading entitled “Colourful tinge to group in Ibrahim outer circle”, which asserts that the network outside the “Ibrahim clan” also contains a selection of “colourful characters”, including “Moses Obeid, the son of jailed former NSW politician Eddie Obeid, one-time jailed businessman Rodney Adler and construction identity George Alex”.

20 The appellant is the subject of the article that appears on page 8, headed “FATHER VERSUS SON”. The subheading reads: “I grabbed his face and smashed it into a wall”. The heading below that refers to the “strained” relationship between the appellant and his father and that they have “come to blows”. This is a reproduction of pages 8 and 9:

21 Because this is the only article that concerns (mainly) the appellant, and because the text of it is not easy to read in the image of it above, the relevant text is set out in Annexure A to these reasons.

22 Pages 10 and 11 are headed “THE NIGHT THAT CHANGED A FAMILY” and “Shooting left Fadi broken – DRUGS, PAIN, STRESS TAKE TOLL IN AFTERMATH OF DRIVE-BY”. The article tells of the effects of Fadi Ibrahim’s life after he was shot and badly injured whilst sitting in his sports car, with his wife. The article is accompanied by photographs taken on the night of the shooting.

23 Pages 12 and 13 are headed “THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT SHAYDA” and “‘Go to your sleazy joints. You make me sick’”. The subheading describes the gist of the article (in capital letters): “There are a number of unwritten rules for women who marry into the Ibrahim family. Raise the kids. Look after the house. Men wear the pants. And the big one: if you don’t earn the money, you keep your mouth shut. Fadi Ibrahim’s glamorous wife Shayda does not adhere to these rules. And it’s why she got into an all night texting brawl with Fadi’s younger brother, Michael, when she suspected the pair were up to no good while holidaying in Dubai.”

24 Pages 14 and 15 are headed “OPERATION PAYBACK” and “KYLE’S FRONT ROW SEAT AT WAXING”. The article commences:

IT’S an act of retribution with a twist. When police found two sets of eyebrows at John Ibrahim’s house, still on the wax strip that ripped them out, they lifted the lid on how the family takes care of business.

Secret recordings tendered to court have now revealed John ordered the waxing as a punishment for two of his hangers-on who stole money and that his radio DJ mate Kyle Sandilands showed up to the beauty salon for a laugh.

A young beautician struggles to keep her composure and a steady hand as she closes in on Ryan Watsford’s eyebrows with a pair of hot wax strips.

25 The “hangers-on” are identified in the article as “Ibrahim associate” Jaron Chester, and Ryan Watsford.

26 A photograph appears on page 15 of the beautician who is said to have performed the waxing, one Bridgette Lee, wearing a bathing suit. The caption reads that she is “a one-time girlfriend of John Ibrahim’s son Daniel”. The article also contains, among many other things, the following text:

Chester had a tougher time than Watsford. He was petrified leading up to the waxing and had a full blown panic attack as it was about to happen. “(Chester) was hyperventilating and he’s like, ‘Have you got any Valium’,” Ms Lee told Daniel in one of the secret recordings.

“I’m like, ‘How’s your anxiety?” and he’s, like, “My anxiety’s so bad.” Ms Lee said. “And he’s sweating. I go ... you need to chill the f..k out, like relax yourself, he’s pacing back and forwards. “Still sporting his drawn on eyebrows, Watsford returned to make sure Chester suffered the same fate and was “acting all tough”, Ms Lee said.

“Yeah. You’re all tough now cause I’ve just put your brows back on and you look like a dickhead,” Ms Lee said.

So why did Watsford and Chester steal the money?

According to a call intercepted by police on May 23, 2017, Chester used the money to cover a debt his parents owed in unpaid rent on their Bellevue Hill home to stave off eviction. It is unclear how Watsford used his portion. But Michael may have referenced it when he spoke to Chester that day.

“What I can’t deal with is prostitutes and getting on it,” Michael said. Michael was furious.

On May 21, 2017, Chester called a friend and said “I’m scared, Mick turned this afternoon”.

That day, Chester received a text from Daniel Ibrahim that said: “I’m coming to pick up yours and your mum’s car tomorrow. Have them ready.” Michael called John on May 22, 2017, and said he couldn’t get to sleep until 5am because he was “burning with anger”.

…

Ms Staltaro also said it’s “not John’s style”. “Mick’s got a sick sense of humour. He’s been in jail for a long time,” she said.

“He’s not as sensitive as we probably are. John is. Especially about appearance, John is.”

Ms Staltaro was scathing of John in an August 2, 2017, call with Chester who reported that Watford’s eyebrows had been waxed. “He’s a f..king idiot. He’s a f..kwit ... You’ve just turned me off … F..king disgusting,” she said.

“I can’t believe he brought Kyle with him. He’s a f..king idiot. I don’t even find it funny ... I don’t think Kyle would find something like that funny,” she said later in the call tendered to court.

Chester corrected her: “He was laughing.” In a recording tendered to the court, Michael and Daniel were laughing in a call as they both watched the footage of the waxing.

“He look like a cancer patient, Oompa ...,” Michael said.

Daniel said: “He’s a f..king cancer ... looks like he’s about to die. Cancer would probably be good for him. He’d lose some weight.” With Watsford and, Chester now without eyebrows, the saga appeared to be over.

27 Pages 16 and 17 are headed “THE STING REVEALED” and “He’s a cop? I thought he was a mate”. The article is about the arrest of Mr Watsford, and his interview with police in which it was revealed that the person he thought was “one of his close friends” and whom he had “brought … into the fold with the Ibrahim family” was in fact a police informer.

28 Pages 18 and 19 are headed “THEY CALL ME MURPH” and “IT’S NOT FAIR: THE COP THE BROTHERS FEAR”. A subheading reads (in capital letters): “He pulled them over, stopped them in the street, knocked their homes – this was a Bondi detective’s old-fashioned way of letting the Ibrahims know who really is the boss on the streets of the eastern suburbs”. “Murph”, it is explained, is Detective Joshua Murphy who, it is said, “us[ed] tactics made famous by US crimefighter Eliot Ness …”

29 Because the errors said to found ground 1 of the appeal include that the primary judge failed to consider, or adequately consider, the article at pages 18-19 and did not read the report as a whole, it is desirable to reproduce those pages:

30 The only reference to the appellant in those two pages is the following:

Det Murphy was also living rent free inside Daniel Ibrahim’s head. When AFP officers burst into Daniel’s apartment and arrested him in August 2017 over proceeds of crime charges he would later beat, Daniel’s first thought was Det Murphy.

“When they first came through I thought it was that dog Murphy,” Daniel told friend Nabih Hadid in a call on August 14, 2017. “And I was waiting to see that f...ing grub.

“I (said) ‘What do you c...s want?’” Daniel said. They go, ‘It’s the AFP, shut your mouth’.”

“My first thought was, ‘F... I’ve been bagging Jews in America too much on Facebook,” Daniel said.

31 Pages 20 and 21 are headed “A DANGEROUS FETISH”. The subheading is “WHEN THE FAMILY GOSSIP GIRL IS IN FULL FLIGHT”. The article relates to the “dangerous secret” of “[o]ne of western Sydney’s crime figures” who had a “fetish for sex with men who dress as women”. The article includes these statements:

History has not been kind to people in similar situations.

In 1992, New Jersey mobster John D’Amato was murdered after it emerged he was secretly gay. His body has never been found. He was rumoured to be the inspiration for gay mobster Vito Spatafore in the television show, The Sopranos, who was killed by fellow Mafia members after being outed.

For this reason, The Sunday Telegraph has chosen not to identify the crime figure.

The calls also give rare insight into the emotionally exhausting responsibilities Michael is forced to carry thanks to his apex position in the criminal world.

32 Pages 22 and 23 are headed “INSIDE THE HOUSES OF IBRAHIM - BOYS’ TOYS, $20K & THAT SECRET TUNNEL”. The article describes police raids on the homes of John, Fadi, and Michael Ibrahim, their mother Wahiba, and Mr Watsford. The article is accompanied by photographs taken by police during the raids, including “a stash of $20,000”, a “cabinet loaded with expensive colognes”, a 9mm pistol in the home of Wahiba Ibrahim, “[g]iant elephant tusks”, and “a secret tunnel”. It also includes references to “a manuscript for the classic Al Pacino movie, Scarface”, a violin case “[a]bove a book about the Mafia”, and “small bag of white powder”. The article also states: “John has not been charged and there is no suggestion he has engaged in criminal behaviour. Fadi has pleaded not guilty”.

33 Page 24 concludes with an offer of a “special digital package” that can be obtained by subscribing at dailytelegraph.com.au.

The pleaded imputations

34 The appellant alleged below, and maintained on appeal, that the report contained three defamatory imputations, namely that he is:

(a) a mobster;

(b) a member of the mafia; and

(c) a criminal involved in organised crime.

The primary judge’s reasons

35 After identifying the issues, describing the contents of the report, setting out in uncontroversial terms the legal principles governing the question of whether the matter complained of conveyed the pleaded imputations, and making some general observations, her Honour continued:

81 The portrait of Mr Taylor [in the report] is certainly unflattering. It does not paint him in a favourable light. And it is understandable that he would be unhappy about it. But the impression of him it creates is not that of a mafia figure, mobster or criminal engaged in organised crime. Rather, Mr Taylor comes across as Mr Hills described him, namely as a petulant young man with a sense of entitlement, who has a complicated and at times turbulent relationship with his father, a foul mouth, a fondness for wisecracks and a predilection for making jokes in poor taste. It is true that the publication discloses that he is close to his uncle, Michael, who is a notorious criminal, and that he was in contact with a prisoner with whom he was apparently on friendly terms. But Mr Taylor does not complain that the publication conveys the imputation that he is an associate of criminals. The pleaded imputations are materially different.

82 Mr Taylor submitted that the publication depicts the Ibrahim family as an organisation involved in nefarious activities, including serious crime. He contended that there are frequent references to “Mafia lore and the language of organised crime”. He pointed to the following matters:

• Michael Ibrahim is said to be “[v]ery well connected in [the] underworld” (p 2) and on the same page Mr Taylor, himself, is described as a “wiseguy”, “which the ordinary reasonable reader would recognise as a term for a member of the Mafia, used in well known films such as Goodfellas”.

• The article on pages 22–23 about the police raid on John Ibrahim’s Dover Heights house which describes some of his possessions, singling out for special mention “a manuscript for the classic Al Pacino movie, Scarface” and the observation that “[a]bove a book about the Mafia on the shelf is what appears to be a violin case”. The specific mention of the violin case was said to “plainly…evoke the classic image of the Prohibition-era American mobster carrying a Tommy gun concealed in a violin case”.

• “Operation payback”, the article on pp 14–15 discussing the “punishment” meted out to Mr Watsford and Mr Chester, which Mr Taylor submitted was likened to a “kneecapping” (but which was in fact said to be “a step away from [such] traditional Kings Cross-style punishments like a kneecapping”).

• The article on pp 18–19 in which Det Murphy is compared to the well-known American detective, Eliot Ness (“Think a Bondi version of Eliot Ness, the smartly dressed 1920s American Prohibition agent [who] took down Al Capone as a member of the squad known as The Untouchables before Kevin Costner immortalised him in the 1987 movie of the same name”). To emphasise the comparison, Mr Taylor noted that the article features an image of the actor, apparently a still from the film.

• The article on pp 20–21, entitled “The Outer Circle”, which referred to the sexual proclivities of a so-called Ibrahim associate, likening him to New Jersey mobster John D’Amato, who “was murdered after it emerged he was secretly gay”. Mr Taylor pointed to the reference in the article to Michael Ibrahim counselling this individual as one of the responsibilities he was “forced to carry thanks to his apex position in the criminal world”.

83 Mr Taylor submitted that this is “the milieu” in which he was identified. He contended that the references to Eliot Ness, Al Capone, The Untouchables, John D’Amato, The Sopranos, Scarface and the violin case are quite gratuitous and could only have been made in order to liken the Ibrahim family to the American mob.

84 There is force in many of these submissions.

85 I accept the submission that the Ibrahim family is depicted as an organisation involved in nefarious activities, including serious crime. The inclusion of the gratuitous references mentioned above does suggest that “the Ibrahim clan” (the expression used on pp 2, 3, 4, 7, 17, 18, 19, and 20) or the “Ibrahim family” (the term used on pp 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 22, and 23) operates like the American mob. Moreover, I am acutely aware that one can be damned by association.

86 But the question here is not whether the publication has the effect of diminishing Mr Taylor’s reputation because he is a member of the Ibrahim family but whether, because of that and the other matters upon which he relied, the publication implies that he, too, is a mobster, a member of the mafia, and/or a criminal involved in organised crime. Mr Smark argued that this was the effect of Mr Taylor’s inclusion as a “key player” in the montage on p 2. But the ordinary reasonably reader, having read the whole of the article, would recognise that the members of the Ibrahim family who are listed there are not all key figures in a criminal network. Read in context, “the key players” are those individuals who feature in the recorded conversations and the police officers who were involved in the investigation which led to the arrest of some of them.

87 The fact that another (or other) members of his family are or may be involved in organised crime does not mean that Mr Taylor is too. And I am not persuaded that the matter complained of suggests that he is. The ordinary reasonable reader would know that you cannot choose your relatives.

88 Neither the reports of the conversations with the prisoner (Hadid) nor those with his uncle Michael imply that he (Taylor) is involved in organised crime, even though it is a fair inference that his uncle was.

89 Unlike other members of the Ibrahim family, Mr Taylor is not said to be “awash with cash”. He is not said to have any of the trappings of wealth. Nor is he said to enjoy a life of luxury. If anything, the opposite is true. The publication implies that he lacked the resources to raise bail, that his Ibrahim family did not come to his aid, and that he relied on his struggling mother to help him out. It records that he was living in a flat owned by his father who was chasing him for rent. The report of the police raid on the homes of Ibrahim family members relates to searches of the homes of John, Fadi, Michael and their mother. It does not insinuate that any of the items mentioned in the article belonged to Mr Taylor. While the publication mentions that the police entered the apartment in which he was living to arrest him, it does not refer to a search of the apartment. Mr Taylor did not submit that the publication inferred that he procured Ms Lee to administer the punishment to Mr Watsford and Mr Chester and the article does not indicate that he was present when the punishment was administered. In all the references in the publication to the involvement of other members of the Ibrahim family in criminal conduct and the actions of police and law enforcement agencies, there is no suggestion that Mr Taylor was also involved apart from the three references to his arrest over his handling of the suitcase, all of which were accompanied by statements that he had been “cleared” of involvement or, in one instance, that he had “beat” the charges.

36 Her Honour then dealt with the appellant’s complaint that he had not been described, as Shayda Ibrahim, Mim Salvato, Margaret Staltaro, and John Ibrahim had been described, as someone who had not been charged and about whom there was “no suggestion” that they had participated in criminal activity. The appellant submitted that the omission of a disclaimer in the same terms in relation to Mr Taylor would suggest to the ordinary reasonable reader that, despite having been “cleared” by the legal system, Mr Taylor was nonetheless involved in criminal activity.

37 Having recorded the appellant’s submission that undue prominence was given to the statement that he had been arrested for “holding a suitcase containing more than $2 million in cash”, and that “the subsequent disclaimer that he had been cleared did not neutralise this imputation”, her Honour continued:

96 In the present case, I am not satisfied that the ordinary reasonable reader of the publication would come to the conclusion that Mr Taylor was a criminal involved in organised crime or if, contrary to my opinion there is a substantial difference between the three pleaded imputations, a gangster or a member of the mafia. While Mr Smark argued otherwise, I consider that, if such an impression might have been given by the report of the arrest and the charge, it is dispelled by the statements that accompany the report on the three occasions it appears. In other words, the antidote overcame the bane. The disclaimer recorded for Shayda Ibrahim and others was inapt in Mr Taylor’s case because, unlike them, he had been suspected of involvement in a criminal enterprise and he had been charged. The ordinary reasonable reader would recognise that. The ordinary reasonable reader would not conclude that, despite having been cleared of handling (or holding) the suitcase full of cash and “any involvement in the tobacco importation ring that snared his uncle Michael”, Mr Taylor was nonetheless guilty or involved. The publication does not insinuate that, despite the outcome of the committal proceeding, the reality was otherwise. Nor does the publication insinuate that Mr Taylor was involved in any other organised crime. I appreciate, of course that the reader is entitled to give some parts of the article more weight than other parts. But I am not persuaded that the publication gave such prominence to the reason Mr Taylor was arrested that the accompanying statement concerning the outcome of the committal would not have removed any impression to the contrary that might have arisen from the report of his arrest and the mention of the charge.

97 In advocating for a different conclusion, Mr Smark argued:

But it doesn’t cancel out. I mean, to use an extreme example, and I’m not suggesting this is that, but a person is not placed in the same position – this is the standard illustration of how bane and antidote is limited, by having an allegation of an invidious crime, like paedophilia, made against him or her and then having it published that the claim has been dropped. The person is still, in terms of what else might be believed about that person, significantly differently situated then as if the material had never been advanced.

And in the context of this matter, this is exactly it. Two million dollars in a suitcase. I mean, most people perhaps would be thinking, well, can you fit $2 million in a suitcase? It’s a very striking proposition. And the article doesn’t go on to say he didn’t, in fact, have $2 million in a suitcase. It simply says he was cleared of charges associated with that. Who has $2 million in a suitcase? It’s a remarkable proposition. It’s not suggested it was a case of mistaken identity or something of that kind.

98 I am not persuaded by this argument either. The ordinary reasonable reader considers the publication as a whole, the words alleged to be defamatory and their context, and “tries to strike a balance between the most extreme meaning that the words could have and the most innocent meaning”: John Fairfax Publications Pty Limited v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50; 77 ALJR 1657; 201 ALR 77 at [26] (Gleeson CJ). While the reference to the suitcase is striking (at least at first) when the publication as a whole is considered and the reference is read in that context, it does not overwhelm or otherwise defeat the effect of the statements that Mr Taylor was cleared. It is a long established principle that, if something disreputable is said of a person in one part of a publication but it is removed by the conclusion, “the bane and the antidote must be taken together”: Chalmers v Payne (1835) 2 Cr M & R 56 at 159.

99 The statements in the publication regarding the circumstances of Mr Taylor’s arrest and the reason he was charged are isolated and nothing is made of them. Importantly, none of the articles in which Mr Taylor is mentioned depicts him as a gangster, a mafia figure or a criminal involved in organised crime. Nor does the publication as a whole — whatever might be said or implied about other members of the Ibrahim family. It is true, as Mr Smark submitted, that the publication does not go so far as to state that Mr Taylor was unaware of the contents of the suitcase or that this was a case of mistaken identity. But in the face of the statements that he was cleared of involvement in the criminal enterprise, the ordinary reasonable reader would not jump to so scandalous a conclusion that he was nonetheless a criminal involved in organised crime, a gangster or a member of the mafia. After all, the article offers no reason to think that Mr Taylor had any knowledge of the contents of the suitcase and is silent about the circumstances in which he came into possession of it.

100 I reject the submission that the reference to Mr Taylor as John Ibrahim’s “wiseguy” son implies that he is a member of the Mafia or a mobster, as Mr Smark contended. Wiseguy (whether written as one word or two) is a colloquial term originating in the United States. The meaning Mr Taylor sought to give it is not universally accepted, certainly not in Australia. I, myself, was unaware of it before reading the submissions in this case. The Macquarie Dictionary does not indicate that it is an accepted meaning in Australian English. It defines the term, whether written as one word or two, to mean “a cocksure or impertinent person of either sex” (accessed 3 February 2022). That definition accords with the definition in the Oxford English Dictionary which is “an experienced or knowledgeable man; usually ironic or [derogatory]; a know-all, a wiseacre; someone who makes sarcastic or annoying remarks …” (accessed 3 February 2022). These definitions perfectly fit the portrayal of Mr Taylor in the matter complained of. Despite the references in the publication to gangsters and the mafia, I do not think that the ordinary reasonable reader of the publication would take the term “wiseguy” when used in connection with Mr Taylor to mean that Mr Taylor is a mobster or a member of the mafia. And Mr Taylor did not plead that the term has a special meaning conveyed to readers with knowledge of some extrinsic facts, such as the use of the term in Goodfellas.

101 Even if wiseguy could have such a meaning, in the context in which it is used to describe Mr Taylor, the ordinary reasonable reader would not interpret it this way. None of the other members of the Ibrahim family or their hangers-on were so described. It is obvious that the term was suggested by the text message sent to Mr Taylor by his father (“[a]ll you’re good for is a smart-arse comment”) reported on p 9. To paraphrase the respondents’ submission, the ordinary reasonable reader would understand it to be a reference to a person who makes “smart-arse comments” — a smart aleck, not a criminal. The “father versus son” article on pp 8–9 is replete with examples, such as Mr Taylor telling his father “the cheque’s in the mail” when he was chasing him for rent money; joking to his aunt (Michael’s wife), in reference to his uncles’ arrest in Dubai, that “at least Mick will lose some weight”; commenting that a photograph of his father on the balcony of his home reading his autobiography was “like getting caught having a wank to your own photo”; and telling his father that his autobiography would be a top seller in “Caltex”, this latter remark generating the text message referred to above.

102 I emphatically reject the submission that the report suggests that Mr Taylor was a prominent underworld figure. The submission was put this way:

On page 8, Taylor is described as being particularly close to Michael Ibrahim, whom the report describes as “Very well connected in the underworld” and holding an “apex position in the criminal world”, and as “trying to challenge his father’s alpha dog status”. All of this suggests that Taylor was prominent within that milieu, and that he was ambitious to rise higher.

103 This is a bridge too far. In no way does the publication suggest that Mr Taylor was a prominent figure in the “underworld” or the “criminal world”. Nor does it suggest that he had any aspirations to become part of it, let alone rise up in it. The submission takes the reference to the challenge to his father’s “alpha dog status” completely out of context.

38 Her Honour therefore found (at [104]) that she was not satisfied that any of the imputations were conveyed, and dismissed the appellant’s application with costs.

The grounds of appeal

39 The appellant’s grounds of appeal were that the primary judge erred:

(1) at [104] in finding that none of the defamatory imputations pleaded was carried by the matter complained of.

(2) at [76] in finding that the three defamatory imputations pleaded did not differ in substance from each other.

Ground 1

40 The appellant submitted that her Honour’s reasoning contained three errors, which in short form involved the propositions that she:

(a) failed to consider the article at pages 18-19;

(b) failed to construe the matter complained of as a whole; and

(c) erroneously applied the dictum of McHugh J in John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50; (2003) 77 ALJR 1657 at 1661-62 [26].

41 The respondent relied on written and oral submissions, which in substance adopted and relied upon the reasoning of the learned primary judge.

42 The errors alleged by the appellant said to constitute ground 1 overlap to a considerable degree, but we will deal with each of them separately, as the parties did in their submissions.

43 We take each of the alleged errors in turn.

Failure to consider the article at pages 18-19

44 The appellant submitted that in finding at [88] that the matter complained of did not specifically say or imply that the appellant was personally involved in crime, and at [99] that none of the articles in which Mr Taylor is mentioned depicts him as a gangster, a mafia figure or a criminal involved in organised crime, the primary judge “failed to consider, or adequately consider, the article at pages 18-19 of the matter complained of … which did carry such implications”.

45 The article at pages 18-19 is about Detective Murphy. He is said to be “the cop the brothers fear”, to have played a leading role in investigating members of the Ibrahim family, and to have “caused several of the Ibrahims’ ranks to up their anxiety medication” and “occupied a vast degree of their thoughtspace”. Accompanied by a large photo of Kevin Costner, who played Eliot Ness in the “The Untouchables”, Detective Murphy was said to be “a Bondi version” of the man who “took down Al Capone”. It was submitted that that comparison was “clearly tantamount to saying that the Ibrahims, in turn, are like the mafia or the American Mob”.

46 The appellant submitted that it is clear from the article that the appellant “is said to have been one of the Ibrahims who was worried about the possibility that he was being investigated by Detective Murphy”, which it was submitted, “in turn, imputes that he had some reason to be worried about being investigated”. It was said that “[t]he suggestion that the [a]ppellant was somehow expecting Detective Murphy to burst through his door, and that his mind turned immediately to this when his apartment was raided, implies a guilty mind on his part, in spite of (and implicitly undermining) the fact that he would later ‘beat’ the charge”.

47 It was submitted that the article thus “directly implicates” the appellant in what was described as “the analogy between the Ibrahims and the American Mob”.

48 The appellant complained that the primary judge only addressed the Detective Murphy article in two places: at [16(5)], where her Honour noted that the seven sentences commencing with “Det Murphy was also living rent free …” (quoted at paragraph [30] above) was one of those in which the appellant was directly named; and at [82], set out at paragraph [35] above. It was submitted that the primary judge “noted that the comparison between Detective Murphy and Ness was one of the ways in which the Ibrahim family was likened to a criminal organisation or the mafia, but she did not recognise” that the appellant “was associated with Detective Murphy (and by extension, the Eliot Ness/Al Capone analogy)” and that her Honour “seems to have regarded the reference as relevant only to the characterisation of the family, and … was under the misapprehension that there was no direct depiction of the [a]ppellant as a gangster, mafia figure or criminal involved in organised crime.”

49 In his oral submissions, Mr Smark SC who appeared with Mr NG Olson of counsel for the appellant, put the submission this way:

The whole context of the matter is that unless you’re substantially, up to a point, excluded … once you’re in the family in that way, you are in the mind of the ordinary reasonable reader branded as someone who’s in organised crime. So that means that far from being exculpatory, this is further context that shows that [the appellant] was travelling with, being treated by the police in the same way as and to be lumped with those other brothers who are explicitly said to be criminals.

50 As for the appellant’s anti-Semitic remark (“My first thought was, ‘F… I’ve been bagging Jews in America too much on Facebook”), counsel agreed that it was “a very off-colour comment, and it’s presented in a way [that] … doesn’t reflect well on him, but that it “doesn’t add to what we say at all, but it doesn’t cancel it out”.

51 In their written reply, counsel submitted that the ordinary reasonable reader would have regarded the appellant’s anti-Semitic remark as “a joke, albeit a joke in bad taste”.

Failure to construe matter complained of as a whole

52 The appellant submitted that her Honour’s “premise that the matter complained of needed to attribute criminality specifically” to the appellant was also erroneous, and that “[i]t plainly attributed such criminality to his family, and it drew no meaningful distinction between him and the rest of the family”.

53 The appellant said that that there was a single, unitary “matter” for the purposes of s 8 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW), and that the matter “had to be construed as a whole, taking into account all of its constituent parts, including not only the text, but also the editing and ‘get-up’ such as layout, graphics and headlines”, including particularly prominent features in the overall context, such as the design of the cover (citing John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50; (2003) 77 ALJR 1657 at 1661-62 [26] (McHugh J) and 1699 [187]-[188] (Callinan J)).

54 The appellant conceded that the primary judge acknowledged that the pleaded matter comprised the whole of the 24-page report at [8] and [28], but complained that “[i]n actually assessing it … she in fact tended not to read it as a whole, but rather to compartmentalise each of the constituent articles, focusing primarily on those which appeared to be ‘about’ the [a]ppellant and giving less attention to the others”.

55 The appellant submitted that the primary judge “singled out” direct references to the appellant, in particular at pages 8-9 (the “Father versus Son” article) “for special attention” and that in doing so, her Honour “detracted from the holistic analysis of the matter which was required by authority” and “caused her to distinguish artificially between the general portrayal of the Ibrahim family and the particular portrayal of the [a]ppellant, in a way which was not supported by the overall structure of the matter complained of”. Along the same lines, it was submitted that the singling out “caused her Honour to focus on the (supposed) lack of specific references attributing criminality to the [a]ppellant, while disregarding the impact which the general milieu of criminality in which he was identified (as her Honour accepted) must have had on the ordinary reasonable reader”, citing her Honour’s reasons at [87]-[89], [96], and [99].

56 The appellant submitted that the primary judge’s central finding that the ordinary reasonable reader “would recognise that the members of the Ibrahim family … are not all key figures in a criminal network” (at [86]) “begs a question”, citing Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 68 at [52] (Rares J) (“When a publisher uses general words to attribute disreputable conduct to a group of named individuals, if he, she or it seeks to persuade the ordinary reasonable reader to read them down to apply to only one of the group, the publisher will need to ‘pick his words very carefully’”). In their written reply, counsel for the appellant submitted that Rares J’s statement “is an instance of the well-established principle that the meaning of a piece of defamatory matter is shaped by its tone”. It was further submitted that cases support the proposition that “tone and context of the matter might well predispose [the ordinary reasonable reader] to draw sinister or scandalous inferences”, citing among other things Lord Devlin’s well known statement in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 at 285 (“[a] man who wants to talk at large about smoke may have to pick his words very carefully if he wants to exclude the suggestion that there is also a fire”).

57 The appellant submitted: “If, as her Honour accepted … the matter conveyed that the Ibrahim family is a criminal organisation comparable to the American Mob, what did it do to make the ordinary reasonable reader think that the [a]ppellant was not like the rest of his family?” The only reasonably open answer to that question was ‘nothing of substance’”.

58 The submission continued that “[t]he starting point of the analysis ought to have been the fact that the [a]ppellant was one of five people depicted on both the front and back covers of the matter complained of, marching entourage-style … behind John Ibrahim. On the second page, he is depicted as Number 5 in a gallery of ‘key players’, and the reader is told that he is ‘John Ibrahim’s wiseguy son’ and that he was ‘charged with handling a suitcase containing $2 million of cash but was cleared after a committal hearing’”. It was submitted that “[t]hese two facts alone” meant that the appellant “from the very outset, [was] extremely prominent in the overall structure and layout of the matter complained of”; that “[n]o meaningful distinction is made” between the appellant and his family; and that the ordinary reasonable reader “could only reasonably assume that someone so depicted on the cover was one of the most important and central figures in the ‘House of Ibrahim’”.

59 That submission further continued as follows:

Any suggestion that the [a]ppellant was portrayed as “just” one of the family, however, does not account for why he was given so much prominence that he was placed on the cover. It would have been easy for the ordinary reasonable reader to see why the others were featured on the cover. John Ibrahim was the patriarch. Michael Ibrahim was “Very well connected in the underworld” (page 2) and held an “apex position in the criminal world” (page 20). Fadi and Shayda Ibrahim were the victims of a drive-by shooting (pages 10-11), a trademark occurrence in the “underworld”. The [a]ppellant’s position in their company would be difficult for the reader to reconcile unless he or she inferred that the [a]ppellant was of comparable significance.

60 It was submitted that “[t]he implicit premise that the ordinary reasonable reader would not come to such a conclusion unless the matter specifically attributed criminality to the [a]ppellant was equally wrong”, and that the fact that “most of the publication has nothing to do with him” (at [15]) “did not mitigate the fact that he was placed on the front cover and named as a key player in the family”. It was submitted that, to the contrary, “the paucity of direct references to him simply meant that the reader was not given additional context to explain why he was displayed in the most prominent place of all” and that “[t]he ordinary reasonable reader could only have been left with the impression he or she would naturally have formed from the outset – that the [a]ppellant was at the core of this family, which is portrayed as a criminal organisation and likened to the mafia or the mob”.

61 The appellant also sought to contend that her Honour was wrong in the way she dealt at [100] with the description of him at page 2 of the report as “John Ibrahim’s wiseguy son.” Mr Smark put the submission this way:

And then he’s John Ibrahim’s wiseguy son. Now, we say, in the context of the matter as a whole where there’s all this talk about organised crime, references to the mafia, Al Capone, Scarface and so on … To call someone a wiseguy in the very place you introduce them is perilous course to take. It’s highly suggestive that he is – of his nature in this criminal organisation as a criminal.

62 It was submitted, in conclusion, that the ordinary reasonable reader would have concluded, looking at the matter complained of as a whole, that contrary to what her Honour said at [85], the appellant was “damned by association”.

Erroneous application of McHugh J’s dictum from Rivkin

63 The appellant also submitted that “[i]n discounting references to criminal charges against the appellant on the basis that they were offset by statements that he had been ‘cleared’”, her Honour “misread” McHugh J’s dictum in John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50; (2003) 77 ALJR 1657 at 1661-62 [26]. That paragraph of his Honour’s reasons is as follows:

However, although a reasonable reader may engage in some loose thinking, he or she is not a person avid for scandal. A reasonable reader considers the publication as a whole. Such a reader tries to strike a balance between the most extreme meaning that the words could have and the most innocent meaning. The reasonable reader considers the context as well as the words alleged to be defamatory. If in one part of the publication, something disreputable to the plaintiff is stated, but that is removed by the conclusion; the bane and antidote must be taken together. But this does not mean that the reasonable reader does or must give equal weight to every part of the publication. The emphasis that the publisher supplies by inserting conspicuous headlines, headings and captions is a legitimate matter that readers do and are entitled to take into account. Contrary statements in an article do not automatically negate the effect of other defamatory statements in the article.

(Internal quotations and footnotes omitted).

64 The submission about that paragraph involved these propositions:

(1) Her Honour erred at [96] in relying on the “bane and antidote” concept, because a statement that the appellant was “cleared” “is insufficient to overcome references to him being charged with handling proceeds of crime, in the context of a salacious and sensationalist publication which depicted his family as a criminal organisation like the Mob”.

(2) The statement that the appellant was “cleared” of charges “contains nothing like a ‘refutation’ of any imputation that [he] was involved in criminality generally” and “reads as a begrudging acknowledgment of what occurred on the public record, rather than as a true vindication”.

(3) The proposition that the ordinary reasonable reader strikes a balance between the most extreme available meaning and the most innocent is a misreading of what McHugh J said at 1661-62 [26];

(4) Although not expressly stated, the primary judge’s reasoning at [98] assumes that the ordinary reasonable reader “will tend to situate the meaning of a piece of matter in the middle ground of the range of available meanings”, and that this is to “misread” what McHugh J said at 1661-62 [26] because:

(a) his Honour said in that paragraph that the ordinary reasonable reader does not necessarily give equal weight to every part of the publication;

(b) features such as headlines, photographs, get up and headings may assume particular importance, and defamatory statements in one part of an article are not automatically negated by somewhat contrary statements in another part;

(c) while the reader is not avid for scandal, he or she might well be encouraged to indulge in scandal by the content and tone of the matter (citing Drummoyne Municipal Council v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1990) 21 NSWLR 135 at 137 (Gleeson CJ); Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 496 at [80] (Wigney J));

(d) the matter inclined decisively away from any “centre point” and towards the clear implication that the Ibrahims, including the appellant, were involved in serious criminality; and

(e) the primary judge erred in holding that a statement that the appellant was cleared of charges was sufficient to overcome the suggestion that he too was involved in criminal activity.

Consideration

Legal principles

65 There was no dispute on appeal about any question of legal principle.

66 The parties accepted that the approach to appellate review of a trial judge’s findings as to whether a publication conveys an imputation is that of a rehearing where the appeal court is in as good a position as the judge below was to determine the proper inference to be drawn from the objective evidence (here, the report). See Warren v Coombes (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 547 (Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ).

67 In that regard, we think that it should no longer be necessary for counsel to draw the court’s attention to the obiter dicta of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Victoria in Gatto v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2022] VSCA 66, that a factual finding by a trial judge whether a matter complained of conveyed an imputation is a discretionary judgment, in respect of which appellate review should proceed in accordance with the principles in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499. That statement of principle was obviously wrong, as judges of this court have said many times. See, by way of example, Bazzi v Dutton (2022) 289 FCR 1 at 7 [22]-[28] (Rares and Rangiah JJ) and 15 [53] (Wigney J); and V’landys v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2023] FCAFC 80 at [72] (Rares J, with whom Katzmann and O’Callaghan JJ agreed).

68 It was also common ground that the tribunal of fact evaluates a publication using the moral or social standards of the community to determine what it conveyed to the ordinary reasonable person. See Reader’s Digest Services Pty Ltd v Lamb (1982) 150 CLR 500 at 505-6 (Brennan J, with whom each of Gibbs CJ, Stephen J, Murphy J and Wilson J agreed).

69 In Trkulja v Google LLC (2018) 263 CLR 149 at 160-61 [32] Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ described the task of analysing the capacity of a publication to convey a defamatory imputation as an exercise in “generosity not parsimony”. Their Honours went on to explain:

The question is not what the allegedly defamatory words or images in fact say or depict but what a jury could reasonably think they convey to the ordinary reasonable person; and it is often a matter of first impression. The ordinary reasonable person is not a lawyer who examines the impugned publication over-zealously but someone who views the publication casually and is prone to a degree of loose thinking … He or she may be taken to read between the lines in the light of his general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs, but such a person also draws implications much more freely than a lawyer, especially derogatory implications, and takes into account emphasis given by conspicuous headlines or captions. Hence, … where words have been used which are imprecise, ambiguous or loose, a very wide latitude will be ascribed to the ordinary person to draw imputations adverse to the subject.

(Internal quotations and footnotes omitted).

70 Favell v Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 52; (2005) 79 ALJR 1716 was a case in which the question was whether the published article, which reported that a house owned by the appellants that was the subject of a controversial development application had been destroyed by fire, was capable of giving rise to the defamatory imputations alleged. It thus involved a question of law, but the following statements of principle from the joint judgment of Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Heydon JJ at 1719-20 [10]-[12] are applicable to the jury question before us, namely whether the pleaded imputations are conveyed in fact:

In determining what reasonable persons could understand the words complained of to mean, the Court must keep in mind the statement of Lord Reid in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [[1964] AC 234 at 258]:

The ordinary man does not live in an ivory tower and he is not inhibited by a knowledge of the rules of construction. So he can and does read between the lines in the light of his general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs.

Lord Devlin pointed out, in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [[1964] AC at 277], that whereas, for a lawyer, an implication in a text must be necessary as well as reasonable, ordinary readers draw implications much more freely, especially when they are derogatory. That is an important reminder for judges. In words apposite to the present case, his Lordship said: [[1964] AC at 285]

It is not ... correct to say as a matter of law that a statement of suspicion imputes guilt. It can be said as a matter of practice that it very often does so, because although suspicion of guilt is something different from proof of guilt, it is the broad impression conveyed by the libel that has to be considered and not the meaning of each word under analysis. A man who wants to talk at large about smoke may have to pick his words very carefully if he wants to exclude the suggestion that there is also a fire; but it can be done. One always gets back to the fundamental question: what is the meaning that the words convey to the ordinary man: you cannot make a rule about that. They can convey a meaning of suspicion short of guilt; but loose talk about suspicion can very easily convey the impression that it is a suspicion that is well founded.

A mere statement that a person is under investigation, or that a person has been charged, may not be enough to impute guilt. If, however, it is accompanied by an account of the suspicious circumstances that have aroused the interest of the authorities, and that points towards a likelihood of guilt, then the position may be otherwise. There is an overlap between providing information and entertainment, and the publishing of information coupled with a derogatory implication may fall into both categories. It may be that a bare, factual, report that a house has burned down is less entertaining than a report spiced with an account of a suspicious circumstance …

(Emphasis in original).

Failure to consider the article at pages 18-19

71 The gist of this contention was that the article at pages 18-19 carried the imputation that the appellant was a mobster, a member of the mafia or a criminal involved in organised crime, and that the learned primary judge failed to consider it, or did not adequately consider it.

72 The first and most obvious point to make about that contention is that her Honour obviously did consider the article at pages 18-19. She commenced by recording the appellant’s submission about it at dot point four of [82], as follows:

The article on pp 18–19 in which Det Murphy is compared to the well-known American detective, Eliot Ness (“Think a Bondi version of Eliot Ness, the smartly dressed 1920s American Prohibition agent [who] took down Al Capone as a member of the squad known as The Untouchables before Kevin Costner immortalised him in the 1987 movie of the same name”). To emphasise the comparison, Mr Taylor noted that the article features an image of the actor, apparently a still from the film.

73 Her Honour then went on to acknowledge at [83]-[84] that there was “force” in the submission that Mr Taylor was identified in various parts of the publication, including pages 18-19, as being part of “the milieu” of a family that was likened to the American mob. Her Honour also accepted at [85] that the Ibrahim family is depicted as an organisation involved in nefarious activities, including serious crime, and that she was “acutely aware that one can be damned by association”.

74 It is also clear that her Honour had regard to the article at pages 18-19 when she said at [89] that, unlike other members of the Ibrahim family, the appellant was not “awash with cash”. That was, as her Honour said, obvious from the fact that after he was arrested at his home – in circumstances described at page 18 – he lacked the resources to raise bail. Her Honour also referred specifically to the fact, also derived from pages 18-19, that when the police went to the appellant’s apartment to arrest him on a proceeds of crime charge, the article did not refer to a search of the apartment, and that other than the three references in the publication to his arrest (accompanied by statements that he had been “cleared”), “there is no suggestion” that the appellant was also involved in criminal conduct or the actions of the police.

75 So the suggestion that her Honour did not have regard to the article at pages 18-19 is unfounded.

76 In our view, it is also quite apparent that her Honour also did not fail “adequately” to consider it.

77 The only place in the article at pages 18-19 where there was any suggestion of any wrongdoing by the appellant was in the description of his arrest by Detective Murphy and the recitation of the appellant’s obscenities that he expressed to a friend when he described the circumstances of the arrest to him in the course of the phone-tapped call.

78 The ordinary reasonable reader was thus told why the appellant thought that the Australian Federal Police were coming after him – that is, because, as he put it, he had “been bagging Jews in America too much on Facebook”. As offensive as those words are, they had absolutely nothing to do with any concern on the appellant’s part that he was being investigated in relation to being a mobster, a member of the mafia or a criminal involved in organised crime. Even if, as the appellant submitted, the ordinary reasonable reader would have regarded the statement as “a joke” (a characterisation with which we emphatically disagree – there is nothing remotely humorous about it), it still indicates that the appellant had no concern that he was being investigated for organised crime.

79 Further, as Mr DR Sibtain of counsel, who appeared with Mr T Senior of counsel for the respondent, put it in his oral submission about the article at pages 18-19, and we agree:

[N]ow, if [Detective Murphy] was waging a one-cop campaign to make their lives hell, it’s not surprising that everyone in the family was aware of them, whether or not they were involved in criminality or otherwise …

…

… there’s no basis for concluding that [the appellant] … himself is a criminal involved, because the only allegation of criminality he is cleared of, and there is nothing else that ties him to any criminal conduct of the family of the kind that is otherwise described.

80 For all those reasons, in our view the primary judge did give sufficient weight to the article at pages 18-19.

Failure to construe matter complained of as a whole

81 Although he put the point in a number of different ways, the appellant’s complaint under this rubric, in substance, was that although the primary judge acknowledged at [8] and [28] that the pleaded matter comprised all of the report, her Honour in fact did not read it as a whole, because she “compartmentalise[d] each of the constituent articles, focusing primarily on those which appeared to be ‘about’ the [a]ppellant and giving less attention to the others”.

82 In our view, there is no merit in that submission. How else was her Honour to have read the report as a whole, as an ordinary reasonable reader would, and assess the imputations alleged to be conveyed, otherwise than by “focusing” on those parts of the articles that mentioned the appellant?

83 The complaint that her Honour “singled out” for “special attention” what were described as “direct references to the appellant” in the article at pages 8-9 and in doing so, “detracted from the holistic analysis of the matter” is also without merit. That article was, after all, entitled “Father versus Son”. That son was the appellant and the article was the only article in the report that was mainly concerned with the appellant, in a document that otherwise mostly had nothing to do with him. How could her Honour sensibly not have given it “special attention”?

84 We do not agree that “the ordinary reasonable reader would have concluded, looking at the matter complained of as a whole, that … the appellant was ‘damned by association’”.

85 In our view, the primary judge was correct to say that most of the matter complained of had nothing to do with the appellant. In our view, her Honour at [86]-[89] explained clearly and correctly, reading it as a whole, what the report did to make the ordinary reasonable reader think that the appellant was not like the rest of his family. It bears repeating, and we entirely agree with, what her Honour said at [89]:

Unlike other members of the Ibrahim family, Mr Taylor is not said to be “awash with cash”. He is not said to have any of the trappings of wealth. Nor is he said to enjoy a life of luxury. If anything, the opposite is true. The publication implies that he lacked the resources to raise bail, that his Ibrahim family did not come to his aid, and that he relied on his struggling mother to help him out. It records that he was living in a flat owned by his father who was chasing him for rent. The report of the police raid on the homes of Ibrahim family members relates to searches of the homes of John, Fadi, Michael and their mother. It does not insinuate that any of the items mentioned in the article belonged to Mr Taylor. While the publication mentions that the police entered the apartment in which he was living to arrest him, it does not refer to a search of the apartment. Mr Taylor did not submit that the publication inferred that he procured Ms Lee to administer the punishment to Mr Watsford and Mr Chester and the article does not indicate that he was present when the punishment was administered. In all the references in the publication to the involvement of other members of the Ibrahim family in criminal conduct and the actions of police and law enforcement agencies, there is no suggestion that Mr Taylor was also involved apart from the three references to his arrest over his handling of the suitcase, all of which were accompanied by statements that he had been “cleared” of involvement or, in one instance, that he had “beat” the charges.

86 Even if her Honour had found that the appellant was “damned by association” with alleged underworld figures, that would not have been enough. It is important to recall that the imputations alleged by the appellant are that he is a mobster, a member of the mafia and a criminal involved in organised crime, not that he associates with people of that kind.

87 We should also briefly mention the point repeated by the appellant on appeal in relation to his description at page 2 of the report as “John Ibrahim’s wiseguy son.” As her Honour said, the accepted meaning of “wiseguy” in Australian English is “a cocksure or impertinent person of either sex”, “an experienced or knowledgeable man; usually ironic or [derogatory]; a know-all, a wiseacre; someone who makes sarcastic or annoying remarks …” And as her Honour observed at [100], those definitions “perfectly fit the portrayal of [the appellant] in the matter complained of”, the meaning the appellant sought to give the term “is not universally accepted, certainly not in Australia”, and “the ordinary reasonable reader of the publication would [not] take the term … when used in connection with [the appellant] to mean that [he] is a mobster or a member of the mafia”. While the appellant asserted that it has another meaning suggestive of criminality, he did not submit that her Honour erred in these findings; he simply said that the other meaning was part of “the criminal context”.

88 In our view, contrary to the appellant’s submission, her Honour had regard to the context and the report as a whole, and correctly concluded that the ordinary reasonable reader of the publication would not come to the conclusion that Mr Taylor was a mobster, a member of the mafia or a criminal involved in organised crime, for the detailed reasons she gave.

Erroneous application of McHugh J’s dictum in Rivkin

89 The appellant’s contention that the learned primary judge “erroneously applied” what McHugh J said in John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50; (2003) 77 ALJR 1657 at 1661-62 [26] involved a number of different but related propositions.

90 They boil down to the contentions that her Honour erred in relying on the “bane and antidote” concept, because a statement that the appellant was “cleared” was insufficient; the notion that the ordinary reasonable reader strikes a balance between the most extreme available meaning and the most innocent was a “misreading” of that dictum; and that although she did not say so, her Honour is to be taken in some fashion or another to have assumed that the ordinary reasonable reader “will tend to situate the meaning of a piece of matter in the middle ground of the range of available meanings”.

91 In light of those criticisms, it is as well to set out [96] and [98] of her Honour’s reasons again:

96 In the present case, I am not satisfied that the ordinary reasonable reader of the publication would come to the conclusion that Mr Taylor was a criminal involved in organised crime or if, contrary to my opinion there is a substantial difference between the three pleaded imputations, a gangster or a member of the mafia. While Mr Smark argued otherwise, I consider that, if such an impression might have been given by the report of the arrest and the charge, it is dispelled by the statements that accompany the report on the three occasions it appears. In other words, the antidote overcame the bane. The disclaimer recorded for Shayda Ibrahim and others was inapt in Mr Taylor’s case because, unlike them, he had been suspected of involvement in a criminal enterprise and he had been charged. The ordinary reasonable reader would recognise that. The ordinary reasonable reader would not conclude that, despite having been cleared of handling (or holding) the suitcase full of cash and “any involvement in the tobacco importation ring that snared his uncle Michael”, Mr Taylor was nonetheless guilty or involved.

…

98 I am not persuaded by this argument either. The ordinary reasonable reader considers the publication as a whole, the words alleged to be defamatory and their context, and “tries to strike a balance between the most extreme meaning that the words could have and the most innocent meaning”: John Fairfax Publications Pty Limited v Rivkin [2003] HCA 50; 77 ALJR 1657; 201 ALR 77 at [26] (Gleeson CJ). While the reference to the suitcase is striking (at least at first) when the publication as a whole is considered and the reference is read in that context, it does not overwhelm or otherwise defeat the effect of the statements that Mr Taylor was cleared. It is a long established principle that, if something disreputable is said of a person in one part of a publication but it is removed by the conclusion, “the bane and the antidote must be taken together”: Chalmers v Payne (1835) 2 Cr M & R 56 at 159.

(Emphasis added).

92 In our view, there is no merit in any of the points raised by the appellant under the Rivkin rubric.

93 First, her Honour’s reference to the bane and the antidote needing to be taken together was obiter dictum. That is so because, as the emphasised words in [96] make clear, her Honour was not satisfied that the ordinary reasonable reader of the publication would come to the conclusion that Mr Taylor was a gangster, a mafia figure or a criminal involved in organised crime. So, on her Honour’s reasoning, with which we agree, the “bane and antidote” issue did not directly arise.

94 Secondly, and in any event, in our view her Honour correctly decided that when the report is considered as a whole, and the reference to the arrest and the charge is read in that context, it does not overwhelm or otherwise defeat the effect of the statements that Mr Taylor was “cleared”.

95 Thirdly, as the respondent submitted, her Honour “was not seeking to determine a centre point in a range of possible meanings … but was rather considering the emollient effect (if any) of the statement that the [a]ppellant was cleared against what [his] counsel … had characterised as the striking imagery of being charged with having $2 million in a suitcase, in the context of the matter complained of as a whole”.

96 Fourthly, as to the proposition that her Honour’s observation that “the ordinary reasonable reader strikes a balance between the most extreme available meaning and the most innocent is a misreading of that dictum” in Rivkin at 1661-62 [26], we disagree. Her Honour’s formulation at [98] (“The ordinary reasonable reader considers the publication as a whole, the words alleged to be defamatory and their context, and ‘tries to strike a balance between the most extreme meaning that the words could have and the most innocent meaning’”) was relevantly indistinguishable from McHugh J’s dictum.

97 But in any event, the relevant question is not to be resolved, as the appellant’s submission suggests it should be resolved, by reference to the single sentence of McHugh J’s dictum. The governing principle is reasonableness. As Rares J (with whom Katzmann and O’Callaghan JJ agreed) said in V’landys v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2023] FCAFC 80 at [108]:

The fact that the authorities, such as Trkulja [v Google LLC (2018)] 263 CLR 149 at 160-161 [32] and Lewis [1964] AC 234, contemplate that the ordinary reasonable reader, listener or viewer can draw defamatory meanings more easily than a lawyer and can do so after engaging in loose thinking, does not entail that in any particular case the tribunal of fact will come to the conclusion that an alleged imputation is conveyed. That is because the hypothetical person is reasonable and the tribunal of fact, in deciding what meaning or imputation a publication conveys, is not bound to select the most damaging, or any other in a range of, available meanings: Stocker [v Stocker] [2020] AC at 604 [34]-[35], 605 [37]-[38], 607 [50]. There (at 604 [35]) Lord Kerr endorsed the guidance that Sir Andrew Clarke MR had given in Jeynes v News Magazines Ltd [2008] EWCA Civ 130 at [14], including the statement that “the governing principle is reasonableness”. I agree.

(Emphasis added).

98 The appellant also referred, as he did below, to the disclaimer given in relation to each of Shayda Ibrahim, Mim Salvato, Margaret Staltaro, and John Ibrahim that they had not been charged and there was “no suggestion” that they had participated in criminal activity, and argued that the omission of a disclaimer in the same terms in relation to the appellant would suggest to the ordinary reasonable reader that, despite having been cleared by the legal system, the appellant was nonetheless involved in criminal activity.

99 We do not agree. Quite apart from anything else, as the presiding judge observed in the course of the hearing of the appeal, to say that someone has been “cleared” puts the matter higher than the position that the evidence suggested had in fact occurred, namely that the charges were either dismissed or withdrawn – and that an ordinary reasonable reader would understand that to say that someone is “cleared” is a positive statement that they were found not to have been involved in criminal activity.

100 The appellant also contended, albeit faintly, that her Honour erred in rejecting his submission that “the report suggests that Mr Taylor was a prominent underworld figure”. As her Honour said, that is “a bridge too far”, for the reasons she gave at [103].

101 It follows that ground 1 fails.

Ground 2

102 The second ground was that the primary judge was also wrong to have concluded in passing that there was no substantive difference between any of the three pleaded imputations. It was common ground that that issue only arises if ground 1 succeeded as to one or more imputation, which is not the case. Accordingly, we do not address the question, conformably with what Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ (Bell, Nettle, Gordon and Edelman JJ agreeing) said in Boensch v Pascoe (2019) 268 CLR 593 at 600-1 [7]-[8]. See too Massoud v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (2022) 109 NSWLR 468 at 480-82 [35]-[41] (Leeming JA, with whom Mitchelmore JA and Simpson AJA agreed)

Disposition

103 The appeal will accordingly be dismissed, with costs.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and three (103) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Wigney, O’Callaghan and Jackson. |

Associate:

Annexure A

FATHER VERSUS SON

I grabbed his and smashed it into a wall

IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY, JOHN IBRAHIM WROTE HE IS A PROUD DAD WHO TAUGHT HIS SON DANIEL HOW TO BE MAN, BUT MORE RECENTLY THEIR RELATIONSHIP IS STRAINED AND THE PAIR HAVE COME TO BLOWS, ACCORDING TO DANIEL

DANIEL Ibrahim was burning. The target of his anger was his father, John. It was August 11, 2017, and the 28-year-old had just been released from Surry Hills Police Centre on bail where he spent nights in a cell after being arrested for holding a suitcase containing more than $2 million in cash.

He has since been cleared of any involvement in the tobacco importation ring that snared his uncle Michael.

Back in 2017, he was relieved to be out, but still furious. His stint behind bars was extended because of the time it took his mother, Melissa Taylor, to raise more than $600,000 in bail money to secure his release.

For this, Daniel blamed John.

In telephone conversations tapped by police and tendered to court, Daniel was recorded telling friends that his father “left me in there” after refusing to help raise the bail money.

“(Mum) ... went ... to John (for help with the bail money) and John’s told her to get f...ed because ‘he’s not my problem’,” Daniel was recorded telling an “unknown male” on August 24, 2017.