Federal Court of Australia

Sino Group International Limited v Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 110

Table of Corrections | |

In order 3: ‘2021’ has been deleted and replaced with ‘2022’. | |

19 July 2023 | In paragraph 1, first sentence: ‘2021’ has been deleted and replaced with ‘2022’. |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 July 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The order of the primary judge on 2 June 2022 be set aside.

3. The deed of company arrangement executed on 28 March 2022 by the administrators of the first respondent, Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd, be terminated.

4. Costs be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 The appellants, Sino Group International Limited and Beijing Yingqidi Education and Technology Corporation Ltd (together, the Sino Creditors), appeal from that part of the judgment below in which their application, challenging a deed of company arrangement executed on 28 March 2022 by the Administrators of the first respondent, Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd (the DOCA), was dismissed. The second and third respondents, Gideon Rathner and Matthew Sweeny respectively, were appointed as the Administrators of Gymbaroo on 22 November 2021 pursuant to a resolution of directors under s 436A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act). The fourth respondent, Dr Janet Williams, was the DOCA proponent and is a director, shareholder and creditor of Gymbaroo. The Administrators are also the Deed Administrators.

2 On this appeal, Gymbaroo and the Administrators had the same legal representation. Dr Williams was separately represented. Her counsel wholly adopted and relied on the submissions made by Gymbaroo and the Administrators and otherwise made short submissions in relation to certain Deeds of Subordination and Forbearance that were entered into on the first day of the hearing below (the Subordination Deeds).

3 Relevantly, the primary judge dismissed the Sino Creditors’ application:

(a) To terminate the DOCA pursuant to s 445D of the Act; and

(b) To set aside the resolutions passed at the second creditors’ meeting in relation to the execution of the DOCA pursuant to s 75-41 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) 2016 (Cth) (IPS), being Schedule 2 to the Act.

See Sino Group International Limited v Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 630 (PJ) at [137] to [154] and [158] respectively. References by the primary judge to the “Insolvency Practice Rules (Corporations) 2016 (Cth)” or the “IPR” are to be read as references to the IPS, with the exception to the reference to “s 75-115” at PJ [109], which is a reference to the Insolvency Practice Rules (Corporations) 2016 (Cth) (IPR).

4 The appellant raises five grounds of appeal.

5 The first two grounds in substance allege that the primary judge erred in assessing the Sino Creditors’ application to set aside the DOCA by reference to the Administrators’ assessment of the Sino Creditors’ proof of debt for voting purposes at the second creditors’ meeting. They say that the primary judge should, instead, have considered how the Sino Creditors’ claim may be assessed for dividend purposes in the competing scenarios of the proposed DOCA or a winding up under s 554 of the Act. The appellants contend that the primary judge thereby ignored and overlooked the ultimate task on which the estimated return to creditors under the DOCA depended, which was to estimate the value of each element of the Sino Creditors’ damages claim in accordance with s 554A of the Act.

6 The third ground in substance alleges that the primary judge erred in not finding that information provided to creditors for the purpose of voting on the DOCA proposal was materially misleading. They say that, contrary to that information, the estimated return to Participating Creditors under the DOCA would not be 100 cents in the dollar once the Administrators and Deed Administrators’ costs were taken into account, amongst other things. Accordingly, the Sino Creditors contend the power to terminate the DOCA under s 445D(1)(a) and / or s 445D(1)(c) of the Act was enlivened and the primary judge erred in failing to consider whether to exercise the discretion to terminate the DOCA.

7 The fourth ground alleges that the primary judge erred:

(a) In failing to apply the correct test under s 445D(1) of the Act in respect of the interests of creditors, namely whether there would likely be a return to creditors on a winding up that is better than under the DOCA;

(b) By failing to draw the proper inference, namely that creditors would receive a better return on a winding up, from undisputed facts in relation to (1) an arms-length, non-binding offer to purchase the business received in response to an expression of interest campaign undertaken by the Administrators; and (2) the effect of the Subordination Deeds.

(c) By not finding that the grounds in s 445D(1)(f)(i) or (ii) of the Act were made out; and

(d) By not exercising the discretion under s 445D(1) to terminate the DOCA.

8 The fifth ground is directed to the primary judge’s alleged error in failing to exercise the discretion to set aside the DOCA under ss 75-41(3)(c) and 75-41(3)(d) of the IPS. In the proceedings below (at PJ [156]) and on the appeal, the parties accepted that this ground stands or falls with the fourth ground, there being a significant overlap and parity of consideration with s 445D(1)(f)(i) of the Act.

9 For the reasons which follow, we have concluded that the Sino Creditors have established error of the type identified in House v R (1936) 55 CLR 499 in relation to both grounds 3 and 4. Further, we consider it appropriate for this Court, being satisfied that the discretion under s 445D(1) was relevantly enlivened, to exercise that discretion to terminate the DOCA. In these circumstances, it is not necessary to determine grounds 1, 2 and 5.

10 The Sino Creditors also bring an application to lead further evidence on this appeal – that evidence is directly relevant to ground 3 of the appeal. For the reasons which follow, we are satisfied that the application to admit the further evidence should be allowed in part.

BACKGROUND

11 The primary judge noted that the parties were not in dispute as to much of the background facts following the appointment of the Administrators to Gymbaroo: PJ [15]. The following summary of the background facts which are presently relevant is largely drawn from the primary judge’s summary: PJ [16] to [26].

12 Gymbaroo provides neuro-developmental and sensorimotor movement programs for children from birth to five years old. Gymbaroo either franchises or licences (as applicable) the use of the programs and the brands in Australia and overseas. Gymbaroo is the registered owner of 31 different trade marks in Australia and holds trade marks, or has pending trade mark applications, in a number of overseas jurisdictions. For the 2018 to 2021 financial years, Gymbaroo had annual revenue of between $1.3 million to $1.7 million.

13 As at December 2021, Gymbaroo had 69 centres across Australia. Two of the centres were owned and operated by Gymbaroo and the balance of the centres were operated by Gymbaroo’s franchisees or licensees. Gymbaroo employed 10 staff members, including three employees in each of the two Gymbaroo-operated centres, and also engaged six contractors who assisted Gymbaroo in administration, education, IT, research and development and marketing.

14 The shareholders of Gymbaroo are members of the Sasse family. They are Bill Sasse, Peter Sasse, Dr Williams (who are siblings) and Harry Sasse (who is their father). Where it is necessary to distinguish between the male members the Sasse family we will refer to them by their first names. Bill, Peter and Dr Williams are each directors of Gymbaroo. Bill, Harry, Peter and Dr Williams are also creditors of Gymbaroo (the Related Party Creditors). The Related Party Creditors are referred to in the context of the DOCA as the Excluded Creditors.

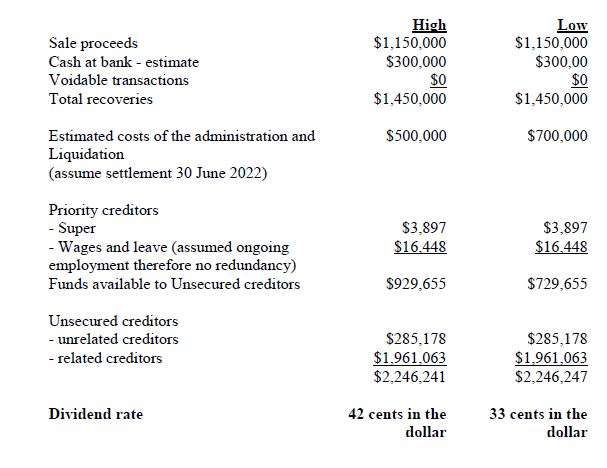

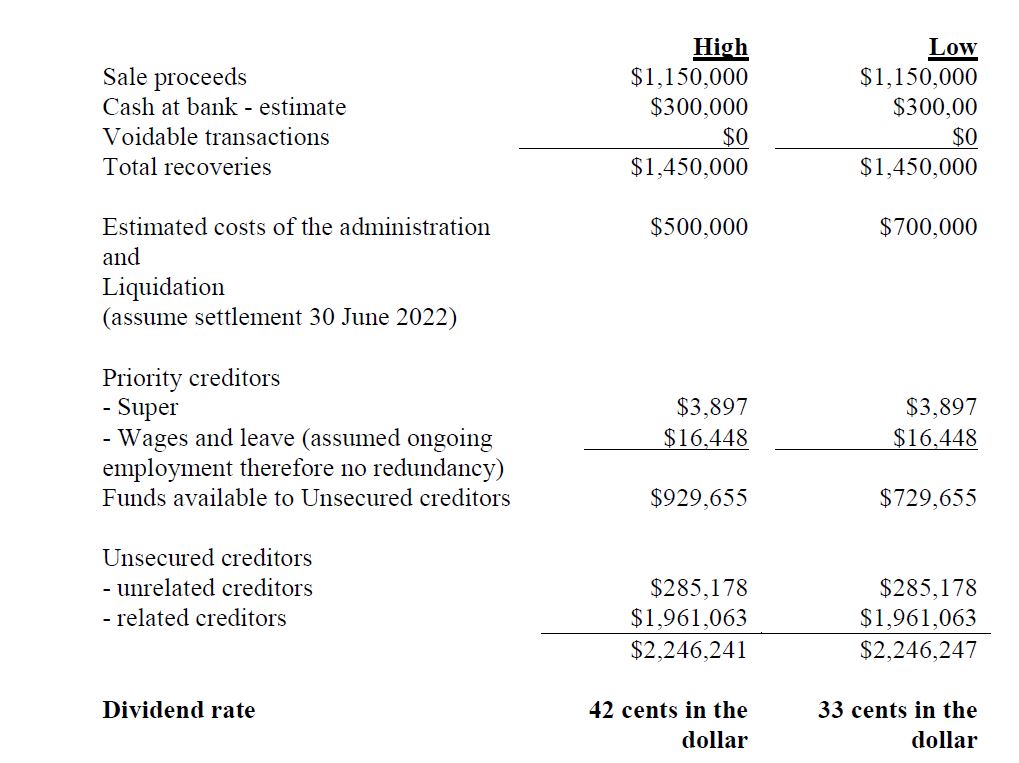

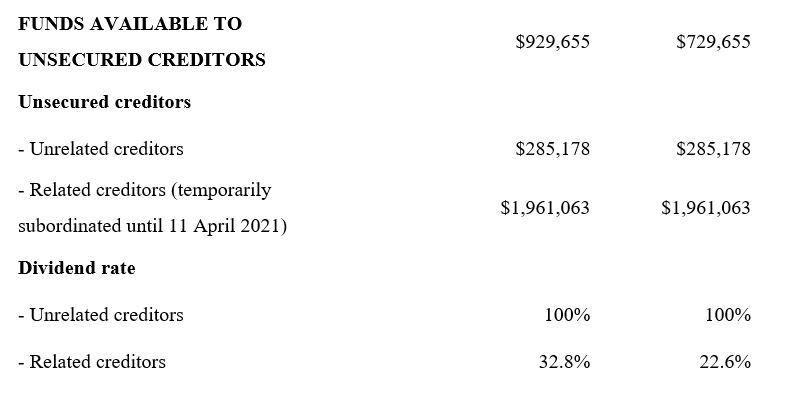

Arbitration between the Sino Creditors and Gymbaroo

15 Pursuant to a Master Licence Agreement dated 13 September 2013 (MLA), Sino is the master licensee for Gymbaroo in the territory of Greater China (as defined in Item 7 of Schedule 1 to the MLA).

16 The appointment of the Administrators on 22 November 2021 occurred against the background of an ongoing arbitral proceeding between the Sino Creditors and Gymbaroo, no. ARB 20/2018 pursuant to the Resolution Institute Arbitration Rules 2016 (Arbitration Proceeding). The Arbitration Proceeding commenced in 2018. The claim of the Sino Creditors against Gymbaroo arises out of an arbitration brought under the MLA. There were two Arbitrators involved in the Arbitration Proceeding.

17 On 14 December 2018, one of the Arbitrators issued an Interim Measures Award which restrained Gymbaroo from acting in breach of the MLA and from seeking to rebrand the Kindyroo business in China.

18 On 26 October 2020, one of the Arbitrators decided that Gymbaroo was liable to pay the Sino Creditors’ costs in respect of a series of failed applications by Gymbaroo to terminate the Arbitration Proceeding. These costs were fixed in the amount of $215,274.96.

19 On 11 January 2021, one of the Arbitrators issued a Partial Final Award in which it was determined, as a preliminary question, that Gymbaroo’s purported termination of the MLA on 6 January 2017 was not lawful and effective, including because Gymbaroo was in breach of essential terms of the MLA with respect to failing to provide induction training and operational visits.

20 On 14 September 2021, one of the Arbitrators made certain preservation orders to be in place either until further order, or the final determination of the Arbitration Proceeding. The orders preserved and maintained Gymbaroo’s assets and intellectual property, and provided that Gymabroo was to give Sino seven days’ written notice of any intention to enter into any sale agreement or other agreement, together with particulars of the proposed sale or dealing. On 22 September 2021, the Sino Creditors filed a Further Amended Statement of Claim in the Arbitration Proceeding which, amongst other things, alleged various breaches of the MLA by Gymbaroo for which damages were sought. Gymbaroo had cross-claimed against Sino in the Arbitration Proceeding, claiming approximately $1,096,823.

21 On 11 November 2021, the Sino Creditors filed submissions on the question of costs in relation to the determination of the preliminary question in the Arbitration Proceeding. The Sino Creditors claimed costs totalling $748,922.19 and also sought an order that Gymbaroo immediately pay the amount of $215,274.78 which had been fixed by the Arbitrator on 26 October 2020.

22 It was anticipated that the next phase of the Arbitration Proceeding would take place in early 2022.

Administrators appointed – 22 November 2021

23 On 22 November 2021, the directors of Gymbaroo resolved to appoint the Administrators under s 436A of the Act. That decision followed Harry’s decision to call up his loan to Gymbaroo of $684,947. Section 436A enables the directors of a company to appoint an administrator to the company if the directors think it is or will become insolvent. It forms part of Part 5.3A of the Act — Administration of a company’s affairs with a view to executing a DOCA.

24 As the time the directors of Gymbaroo resolved to appoint the Administrators, the Sino Creditors’ claim in respect of their costs on the liability phase of the Arbitration Proceeding had not been heard and determined and a timetable for the damages phase of the Arbitration had not been entered.

25 On 30 November 2021, the Sino Creditors lodged a proof of debt with the Administrators for $5,964,197.15 comprising: fixed legal costs of $215,274.96; the additional costs (not yet fixed) of $748,922.19; and an estimated damages claim in the sum of $5,000,000 for their alleged losses as a result of Gymbaroo’s breaches of the MLA: PJ [31].

First creditors’ meeting – 1 December 2021

26 On 1 December 2021, the Administrators held the first meeting of Gymbaroo’s creditors in accordance with s 436E of the Act.

27 At the first creditors’ meeting, the Administrators admitted the Sino Creditors to vote for $964,198.15 — comprising fixed costs of $215,274.96, additional costs (not yet fixed) of $748,922.19, and allowing the damages claim for $1 “as there is no calculation provided to determine its reasonableness”: PJ [32]. The Related Party Creditors were admitted to vote for $863,456: PJ [32].

28 On 1 February 2022, the Administrators caused an advertisement to be placed online seeking expressions of interest to acquire Gymbaroo’s business and intellectual property assets (EOI Campaign). The closing date for expressions of interest was midday on 21 February 2022.

29 As at 8 March 2022, the Administrators had received five non-binding indicative offers to buy Gymbaroo. This included one offer dated 7 March 2022 to purchase the assets of Gymbaroo for a cash price of $1.15 million to be settled by 30 June 2022 (the Indicative $1.15 million Offer). The offer provided for a $100,000 deposit to be paid upon the signing of the agreement, subject to due diligence, and the balance to be paid on settlement. As at the date of the commencement of the hearing before the primary judge, the Indicative $1.15 million Offer appeared to be open but the position appears to have changed by the time of closing submissions.

Administrators commence proceedings

30 On 8 December 2021, the Administrators commenced proceedings VID 732 of 2021 by which orders were sought under s 447A of the Act and s 90-15 of the IPS to the effect that they would be justified and acting reasonably in proceeding on the basis that the preservation orders made against Gymbaroo in the Arbitration Proceeding not be recognised or enforced against them as Administrators.

Sino Creditors bring application

31 In proceeding VID 732 of 2021, by interlocutory process filed on 14 January 2022, the Sino Creditors sought to have the Administrators removed pursuant to ss 447A and / or 447B(2) of the Act and / or s 90-15 of the IPS.

32 On 28 January 2022, the Court ordered that none of the parties to the Arbitration Proceeding were to take any further steps in the Arbitration Proceeding without leave of the Court.

33 The Sino Creditors’ interlocutory application was listed for hearing but adjourned on 28 January 2022 and 11 March 2022. On 11 March 2022, the hearing was further adjourned to 29 March 2022.

Administrators revise voting rights

34 On 11 March 2022, after the first meeting of creditors but prior to the second meeting of creditors which was scheduled to take place on 25 March 2022, the Sino Creditors were informed, by an affidavit affirmed by Mr Rathner on 9 March 2022, that the Administrators had revised their assessment of the competing creditors’ claims for the purpose of voting at the upcoming second creditors’ meeting by increasing the Related Party Creditors’ claims collectively to the sum of $1,961,062, and reducing the Sino Creditors’ claims to the sum of $161,647.

35 The Administrators’ rationale for the revised assessment was provided in the Administrators’ Report which was issued to creditors on 18 March 2022: PJ [35]. The reduced amount of the Sino Creditors’ claim for voting purposes was arrived at by:

(a) Including fixed costs of $215,274.96;

(b) Including additional costs (not yet fixed) in the reduced amount of $539,922 (a reduction based on applying the same discount as reflected in the fixing of the Sino Creditors’ first costs award);

(c) Including the claim for damages (said by the Sino Creditors to be approximately $5 million) for the nominal sum of $1 (said to be on the basis that no evidence had been provided to quantify the claim); and

(d) Setting off what was described as unpaid license fees plus interest due under the MLA in the sum of $593,621.

See PJ [36] to [37].

Convening of the second creditors’ meeting – 18 March 2022

36 In the intervening period, the second meeting of creditors of Gymbaroo was called. The Administrators’ Report was provided to creditors under cover of a letter from the Administrators in which they recommended that the creditors resolve that Gymbaroo enter into the DOCA. Annexed to that letter was a notice of meeting, the Administrators’ Report, the Administrators’ Remuneration Approval Report dated 18 March 2022 (Remuneration Report), and the DOCA.

37 The Administrators recommended the DOCA proposal to creditors on the basis that it provided an estimated dividend to Participating Creditors of 100 cents in the dollar as a result of the Related Party Creditors (referred to as the Excluded Creditors) agreeing not to participate: Administrators’ Report at page 29, PJ [29]. The Administrators contrasted this outcome with a winding up scenario where they estimated a dividend to creditors in the range of 33 to 42 cents in the dollar: Administrators’ Report at pages 28 to 29, PJ [29].

38 The primary judge noted that it is uncontroversial that the purpose of the Administrators’ Report was to permit creditors to make an informed choice as to what should happen to Gymbaroo: PJ [30].

Administrators’ Report

39 The relevant sections of the Administrators’ Report for present purposes are as follows.

40 The purpose of the Administrators’ Report was set out at page 1:

The purpose of this report is to provide creditors with sufficient information for them to make an informed decision about the future of the Company including:

• background information about the Company;

• the result of our investigations;

• the estimated returns to creditors;

• details of any proposed Deed of Company Arrangement; and

• the options available to creditors and our opinion on each of these options.

…

41 At pages 16 to 17 the Administrators said:

At a meeting of creditors to be held on 25 March 2022, creditors will be asked to make a decision by passing a resolution in respect of the options available to them. In this report, we have recommended to creditors that the Company execute a Deed of Company Arrangement and detail why this option is, in our opinion, in the best interests of creditors.

…

8.2.4 Contingent Liabilities - ROCAP $nil 28/2/2022 $539,992

As set out in Section 3 and 4 of this report relating to the arbitration with Sino, cost orders were made against the Company in favour of Sino in the amount of $215,274. This amount is included above at section 8.2.3.

In addition to the cost orders, Sino has made a costs claim of $748,922 relating to the determination of the preliminary question, resulting from the 11 January 2021 Partial Final Award (referred to at section 4).

In determining the costs order of $215,274, the Arbitrator applied the following methodology to Sino’s then claim for costs of $290,393:

• Sino Lawyers and Counsel: 70%

• Arbitrators fees and Disbursements: 85%

Applying the same methodology to Sino’s costs claim of $748,922 results in the assessment of Sino’s costs claim at $539,992.

For the purpose of estimating the contingent liability for the costs claim we have allowed $539,992.

In addition, Sino also claim damages of “Approximately $5,000,000 (Further details to be advised”). No evidence has been supplied to quantify or prove that claim.

In our view the damages claim is an unliquidated contingent claim and as such cannot be quantified by a just estimate. Accordingly, we assess the damages claim for a nominal value of $1.

…

42 At page 24, the Administrators said:

In view of all the above comments, it is our opinion that the Company likely became insolvent on or about the time of our appointment as administrators or would have become insolvent when the cost claim of Sino would have been determined and as a result of the related parties ceasing to provide financial support for the business.

We advise that should the Company be wound up, an action may be taken by the liquidator, creditors or ASIC against a director of the Company for insolvent trading. This action would include any directors of the Company at the date the Company is deemed to be insolvent. Any action would require a significant amount of work to be performed by the liquidator with no guarantee of success, or of a successful recovery from the directors.

…

43 At pages 26 to 27, the Administrators said:

11. Expression of Interest in the business and assets of the Company

On 1 February 2022 we advertised on seek.commercial.com.au seeking expressions of interest (EOI) in the business and assets of the Company.

We advertised on seekcommercial.com.au as it claims to be Australia's largest marketplace for selling businesses.

The advertising went for the period 1 February 2022 to 4 March 2022. It resulted in: - 2,348 search results - 134 views

In addition, direct approaches were made to the Company's competitors identified by the Directors and our review of the IBIS World industry report. We also approached all the Company's franchisees within Australia and overseas.

We received 5 offers. One offer for $1.15M stood out as worthy of further consideration.

We have received confirmation from the successful party that its offer remains open until 31 March 2022, being after creditors meeting scheduled to be held on 25 March 2022.

[Page 27]

Our assessment of this non-binding offer indicates a return to unsecured creditors between 33 cents to 42 cents in the dollar (see Winding up section 13 below).

44 At page 27, the Administrators then said the following in relation to the proposed DOCA:

12. Director’s Proposal for a Deed of Company Arrangement

One of the Directors, Janet Williams, has submitted a proposal for a Deed of Company Arrangement (“DOCA”). The proposed DOCA is attached. In summary, the proposed DOCA provides for:

A Deed Fund of $600,000 is to be created comprising: - Cash held by the Administrators: - Director’s contribution for the balance up to $600,000 | - estimated at $300,000 - estimated at $300,000 |

The Director’s contribution, if required, is to be paid in 2 instilments 50% within 7 days of the execution of the deed; and 50% by 30 May 2022

The related parties owed a total of $1,937,904 will not participate under the Deed.

The Participating Creditors are calculated to be:

Priority Superannuation owing | $3,897 |

As the Company will continue to trade the outstanding entitlements for leave will be paid in the ordinary course.

Unsecured Credit card ATO - running account balance Trade creditors Sino (after set off counter claim) | $13,539 $27,186 $82,806 $161,647 | $285,178 |

It is estimated that under the proposed DOCA, Participating Creditors will receive a dividend of 100 cents in the dollar.

Deed Fund Less estimated costs and administration fees Priority creditor - super Participating unsecured creditors Balance to be returned to the Company Priority | $600,000 $310,000 $3,897 $285,178 $1,925 |

Assumptions:

• cash at bank $300,000 is after payment outstanding administration trading obligations

• fees do not exceed $310,000 in best case scenario

• Sino claim admitted for estimated amount of $161,647. If Sino disputes the assessment of its claim, then legal fees and administration fees are likely to be higher

• no continuing or other litigation.

45 Immediately following that, at pages 27 to 28, the Administrators said the following about winding up:

13. Winding Up

Should creditors decide that the Company ought to be wound up, then it is likely that unsecured creditors will receive a dividend estimated at 33 to 42 cents in the dollar.

In this scenario it is assumed that the business is sold and approximately $1.15 million is recovered for the assets including the debtors.

Assumptions:

• no adjustment to indicative offer

• no adjustment for liabilities to be assumed by purchaser for

• deposit for new franchise $2,000

• gift vouchers $10,881

• purchaser takes over all employees and leases of premises

• cash at bank $300,000 is after payment outstanding administration trading obligations

• fees do not exceed $500,000 in best case scenario

• Sino claim admitted for estimated amount of $161,647. If Sino disputes the assessment of its claim, then legal fees and administration fees are likely to be higher

• no ongoing or other litigation.

46 At pages 28 to 29, the Administrators said the following about the interests of creditors:

14. Interests of Creditors

In forming our opinion on the options available to creditors we can only consider the commercial outcomes, that is which proposal is likely to provide for a better return for the Company’s creditors. Creditors may have other reasons and issues in considering their interests.

Creditors are required to decide whether:

i) the administration should come to an end; or ii) the Company should be wound up; or iii) the Company should execute a Deed of Company Arrangement.

i) It is our opinion that it is not in the interests of creditors that the administration of the Company come to an end as the Company is insolvent and will continue to be insolvent. It is also our opinion that if the administration comes to an end, then it is likely that one or more creditors may seek to windup the Company. Further the arbitration between the Company and Sino is likely to resume and the outcome of the matter will be unknown with the likelihood that the cash position of the Company may deteriorate further with further spending on legal costs. The financial position of the Company will not be resolved. It will continue to be insolvent.

ii) As stated above, in the event that the Company is wound up, then it is our view that the unsecured creditors are likely to receive only about 33 to 42 cents in the dollar as a dividend. Accordingly, it is our opinion that it is not in the creditors' interests for the Company to be wound up.

iii) In agreeing to the Deed of Company Arrangement, the fund available for disbursement to unsecured creditors will be greater than in a liquidation as a result of:

• The directors will procure a contribution to ensure the Deed Fund is $600,000.

• The excluded priority employees' claims will not participate for a dividend.

• The claims of the unsecured creditors will be further reduced by the agreement of the related entities not to participate for a dividend.

• The claims of the contingent creditors relating to leases of the premises are unlikely to crystallise.

• No redundancies will occur.

Accordingly, the claims of creditors entitled to participate for a dividend will be significantly lower. It is estimated that Participating Creditors will receive a dividend of 100 cents in the dollar.

It is our opinion that a Deed of Company Arrangement along the line of the Director's proposal is in the creditors' interests for the reasons set out above.

Administrators’ Remuneration Approval Report

47 In the Remuneration Report, creditors were relevantly requested to approve remuneration of: $306,787.70 for the voluntary administration; $180,738.25 if a DOCA were accepted; or $399,501.95 if the company were liquidated. The Remuneration Report also included the following:

In this remuneration approval report, the estimate for our fees under an administration and Deed of Company Arrangement scenario reflects a total higher estimate of $487,525.95 excluding GST than what has been estimated at a cap of $310,000 excluding GST in the report to creditors dated 18 March 2022. The capped amount is based on no further court matters. At this time we cannot confirm if there will be any further court matters in relation to Sino under a Deed of Company Arrangement scenario.

If there is significant litigation, court involvement and legal proceedings, the capped estimate of $310,000 excluding GST will no longer apply and we will have to seek higher fees than what has been estimated in our report to creditors under a Deed of Company Arrangement scenario. This is reflected accordingly in the resolutions we are seeking approval from the creditors on a worse case (sic) scenario.

48 In this way, the Remuneration Report sought approval from creditors of remuneration based on an estimate of potential costs of at least $487,525.95 ($306,787.70 plus $180,738.25) in the DOCA scenario – on a “worse case scenario”. That is approximately $180,000 more than the “best case” scenario referred to in the Administrators’ Report which underpinned the headline comparator for the DOCA of 100 cents in the dollar.

Second creditors’ meeting – 25 March 2022

49 The second creditors’ meeting was held on 25 March 2022, at which time the resolution to approve entry into the DOCA was approved by majority in number and in votes.

50 The minutes of the second meeting record that the Administrators admitted Sino Creditors’ claims for voting purposes at the second creditors’ meeting in the sum $161,647. The Related Party Creditors were collectively admitted to vote in the total sum of $1,937,904. The remaining unrelated creditors were collectively admitted to vote in the total sum of $50,189.

51 On the resolution that Gymbaroo execute the DOCA, all creditors, except the Sino Creditors, voted in favour. However, had the votes of the Related Party Creditors been excluded, the resolution would not have passed by either of the requisite majorities.

The DOCA

52 On 28 March 2022, Gymbaroo and the Administrators executed the DOCA.

53 The DOCA relevantly includes the following provisions:

(1) A Deed Fund of $600,000 is to be established by the Deed Administrators [cl 1.1, cl 4.1].

(2) The Deed Fund shall comprise the Company Funds and the Deed Contribution [cl 1.1].

(3) The term ‘Company Funds’ is defined as follows [cl 1.1]:

Company Funds the amount of money held in the Administration Bank Account as at the Effective Date (including but not limited to monies received from trade debtors of the Company prior to the Effective Date) after allowing for all unpaid liabilities and obligations of the Company during the Administration Period

(4) Effective Date means the date of execution of the Deed [cl 1.1].

(5) Deed Contribution is defined as follows [cl 1.1]:

Deed Contribution the amount calculated in accordance with the following formula:

Deed Contribution = Deed Fund – Company Funds

(6) The Proponent must procure payment of the Deed Contribution to the Deed Administrators as follows [cl 3.1]:

(a) 50% of the Deed Contribution within 7 days of the Effective Date; and

(b) 50% of the Deed Contribution on or before 30 May 2022.

(7) Payments out of the Deed Fund are in the following order [cl 4.1]:

(a) firstly, to the Administrators in respect of the Administrators' Remuneration and Expenses;

(b) secondly, to the Deed Administrators in respect of the Deed Administrators' Remuneration and Expenses;

(c) thirdly, in the order specified in Section 556 of the Act as though the Company were being wound up and there were no Claims by any Secured Creditor; and

(d) fourthly, in full and final settlement of the proved Claims of all Participating Creditors and if more than one on a pari passu basis.

(8) Participating Creditors will be entitled to payment of that portion of the Creditor’s Claim as the Deed Administrators determine that they are able to pay [cl 4.3].

(9) Participating Creditors means all Creditors other than the Excluded Creditors [cl 1.1].

(10) The Excluded Creditors are William (Bill) Sasse, Peter Sasse, Janet Williams and Harry Sasse [cl 1.1], who are all related parties of the Company.

(11) The Deed Administrators will determine and make payments of Claims to Participating Creditors on the same basis as in a winding-up [cl 4.5].

(12) Claim is defined as follows [cl 1.1]:

Claim a debt payable by, and all claims against, the Company (present or future, certain or contingent, ascertained or sounding only in damages) and being a debt or claim the circumstances giving rise to which occurred on or before the Appointment Date and which would be admissible to prove against the Company in accordance with Division 6 of Part 5.6 of the Act if the Company were to be wound up

(13) All Participating Creditors [but not Excluded Creditors] must accept their entitlements (if any) under this Deed in full satisfaction and complete discharge of all Claims and will, if called upon to do so, execute and deliver to the Company such forms of release as the Deed Administrators may require [cl 2.3].

(14) Upon termination of the Deed pursuant to cl 7:

(a) the Company will be forever released from all Claims of Participating Creditors [but not Excluded Creditors]; and

(b) all Claims of Participating Creditors [but not Excluded Creditors] will be discharged and extinguished forever [cl 2.4].

(15) Termination under cl 7 of the Deed includes if there is an unremedied breach by the Proponent [cl 7.1(c)] whose obligation is to procure the Deed Contribution [cl 3.1].

(16) Subject to s 444D of the Act, the Deed may be pleaded by the Company against any Participating Creditor as a bar to any Claim that is released, discharged and extinguished under this Deed.

Sino Creditors commence separate proceedings

54 On 29 March 2022, the day after the DOCA was executed, the Sino Creditors commenced proceedings VID 153 of 2022 in which they sought orders terminating the DOCA under s 445D and / or 445G of the Act, or alternatively under s 75-41 of the IPS. The application was listed for hearing before the primary judge on 11 April 2022. In their application, one of the grounds upon which Sino relied was that Gymbaroo would remain insolvent even after completion of the DOCA due to the debts owed to the Related Party Creditors. For this reason, it was contended by the Sino Creditors that the DOCA should be terminated and Gymbaroo should be wound up.

The Subordination Deeds

55 On 11 April 2022, which, as mentioned, was the first day of the hearing of the Sino Creditors’ application to terminate the DOCA, each of the Related Party Creditors executed Subordination Deeds. By these deeds, the Related Party Creditors agreed that the debts due to each of them from Gymbaroo would not be repayable for three years and that they would not prove or claim repayment of their debts in the event Gymbaroo became insolvent in the intervening period. The Subordination Deeds were not conditional on a continuation of the DOCA and were executed in the face of an extant application to terminate the DOCA. The Subordination Deed to which Harry was a party was executed by Dr Williams pursuant to a power of attorney.

56 The circumstances in which the Subordination Deeds came to be executed during the hearing of the Sino Creditors’ application were not explained in the evidence before the primary judge. Although not in evidence on the appeal, Dr Williams’ counsel submitted that:

…The deeds were entered into in response to criticisms raised in opening address at the trial that the DOCA offended notions of commercial morality and public policy on the basis that the DOCA didn’t extinguish my client and her three siblings’ related debt. And it was put against my client that if she could in effect or one of her siblings could in effect tip the company into insolvency by calling up a related debt after the DOCA was effectuated.

So in order to neutralise that concern, the deeds were, indeed, prepared after court that day and produced the next day to take that concern off the table as the potential for one of the related parties to put the company into liquidation after the DOCA was effectuated. That was the reason why it was done and that was the reason why there was no evidence about it because it was all done so terribly quickly. But that’s the extent of the circumstances surrounding the creation of the deeds. …

57 In each Subordination Deed it is recited that the Related Party Creditor has agreed “at the request of [Gymbaroo]” to subordinate his or her debts to the claims of the unrelated creditors and to forbear calling upon his or her loan. Harry, whose decision to call up his loan triggered the appointment of the Administrators under s 436A of the Act, was one of those that executed a Subordination Deed, albeit by his attorney, Dr Williams, who was also the Deed Proponent. Given the timing of the Subordination Deeds being executed and introduced into evidence, it does not appear that either Dr Williams or Mr Rathner was cross-examined on the circumstances in which the deeds came to be executed. There is no explanation for Gymbaroo’s apparent decision to request the Related Party Creditors to enter into the Subordination Deeds other than to defeat the Sino Creditors’ application to terminate the DOCA in so far as it was based on the submission that the DOCA was contrary to public policy.

LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK AND APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES

58 At trial, there was no dispute as to the statutory framework and relevant principles to be applied: PJ [105]. The primary judge summarised the statutory framework and principles relevant to the present appeal at PJ [106] to [127]. For present purposes, noting that grounds 3 and 4 are determinative of this appeal, it is only necessary to address the principles in respect of s 445D(1)(a), (c) and (f) of the Act.

Section 445D - Court termination of a deed of company arrangement

59 The Court has power to terminate a deed of company arrangement under s 445D of the Act which relevantly provides:

445D When Court may terminate deed

(1) The Court may make an order terminating a deed of company arrangement if satisfied that:

(a) information about the company’s business, property, affairs or financial circumstances that:

(i) was false or misleading; and

(ii) can reasonably be expected to have been material to creditors of the company in deciding whether to vote in favour of the resolution that the company execute the deed;

was given to the administrator of the company or to such creditors; or

…

(c) there was an omission from such a document and the omission can reasonably be expected to have been material to such creditors in so deciding; or

…

(f) the deed or a provision of it is, an act or omission done or made under the deed was, or an act or omission proposed to be so done or made would be:

(i) oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against, one or more such creditors; or

(ii) contrary to the interests of the creditors of the company as a whole; or

...

(2) An order may be made on the application of:

(a) a creditor of the company; or

...

60 The materiality test in s 445D(1)(a)(ii) is incorporated by reference in s 445D(1)(c).

61 In the present case, the relevant document for the purpose of s 445D(1)(a) and (c) is the Administrator’s Report. Such a report must be provided to creditors before the second creditors’ meeting. It was not in dispute that the purpose of an administrator’s report is to permit creditors to make an informed choice as to what should happen to the company: DSG Holdings Australia Pty Ltd v Helenic Pty Ltd (2014) 86 NSWLR 293, [90] Leeming JA, Meagher JA and Bergin CJ in Eq agreeing.

Sections 445D(1)(a) and (c) – false or misleading information

62 The following principles, drawn from the authorities, apply to s 445D(1)(a) and (c) of the Act and are relevant in the present context:

(1) The test for whether information is false or misleading or contains a material omission is determined objectively.

(2) The inquiry is directed to the adequacy of the information presented to creditors to enable their decision-making, not to the intention or conduct of any person who provides the information.

(3) It is the objective quality of the information that is assessed, not whether anyone was in fact mislead.

(4) The inquiry is directed to the information available at the date of the hearing and is not limited to the information available at the time the information was produced.

(5) Estimates as to recoverability may be misleading in circumstances where no qualifying information or doubt is expressed as to the recoverability of the certain amounts, notwithstanding that a creditor may appreciate that the information is merely an estimate or prediction.

(6) Estimates of liability that are not close to the actual liability later revealed may be false or misleading for the purposes of s 445D(1)(a).

(7) Where an estimate of a liability is represented to be “likely to arise in the future” and that figure ultimately proves to be far too low, the estimate may be false or misleading where based on an incorrect and material particular or by reason of an omission of a material particular.

(8) An omission which can reasonably be expected to have been material to creditors in deciding to vote in favour of execution of a DOCA may justify terminating a DOCA under s 445D(1)(c).

(9) Section 445D(1)(c) is to be understood in the context of an administrator’s statutory and other duties to make investigations and inquiries.

(10) Sections 445D(1)(a) and (c) each require that the information or omission is of a kind that can reasonably be expected to have been material to creditors in deciding whether to vote in favour of executing a DOCA.

(11) In the context of s 445D(1)(a), “material” means something which was relevant and did affect, or might have affected, the outcome (being the decision to execute the DOCA). By extension, in the context of s 445D(1)(c), “material” means something which was relevant and might have affected the outcome.

(12) The information or omission need not reasonably be expected to be material to all creditors, but it must affect a sufficient number.

(13) The test of materiality is objective.

(14) In deciding whether the materiality test is satisfied, all the information about the company’s business, property, affairs or financial circumstances that has been found to be false or misleading, or to have been omitted, should be considered collectively.

See further discussion in Bidald Consulting Pty Ltd v Miles Special Builders Pty Ltd [2006] NSWSC 1235; (2006) 226 ALR 510 at [147], [150] to [152], [162], [165] to [169], [176]; Bovis Lend Lease v Wily [2003] NSWSC 467 at [324], [345]; Mondello Farms Pty Ltd v Annatom Pty Ltd (subject to a deed of company arrangement) [2007] SASC 296; 64 ACSR 91 at [97] to [101]; Adelaide Brighton Cement Limited, in the matter of Concrete Supply Pty Ltd v Concrete Supply Pty Ltd (subject to a deed of company arrangement) (No 4) [2019] FCA 1846 at [1197] to [1198].

Section 445D(1)(f)(i) – oppression, unfair discrimination or unfair prejudice

63 Section 445D(1)(f)(i) will be satisfied if the DOCA, or a provision of it, is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against, one or more creditors.

64 The principles applicable to s 445D(1)(f)(i) were summarised by McKerracher J at first instance in Decon Australia Pty Ltd v TFM Epping Land Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 32 at [202] to [203] (approved by the Full Court in Decon Australia Pty Ltd v TFM Epping Land Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 54 at [168]):

202 In respect of s 445D(1)(f)(i) of the Corporations Act, and whether the DOCA is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial to, or unfairly discriminatory against, one or more creditors, the following propositions of law are applicable to the current circumstances:

(a) Part 5.3A of the Corporations Act assumes that the creditors are best placed to judge their interests so a setting-aside will not be ordered lightly: University of Sydney v Australian Photonics Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 412; (2005) 53 ACSR 579 at [34];

(b) the mere fact that a creditor is prejudiced by the operation of the deed is not a sufficient reason to terminate a deed. The mere existence of the deed procedure usually means that some creditors will gain something and some creditors will lose something out of the arrangement: Fleet Broadband (at [57] and the authorities cited therein);

(c) the test under s 445D(1)(f)(i) is not merely discrimination or prejudice, but unfair discrimination or unfair prejudice. Some degree of discrimination is not necessarily unfair. Thus, it is clear that a DOCA may provide for differential dividends among creditors: Hamilton v National Australia Bank Ltd (1996) 66 FCR 12 (at 38E). Part 5.3A does not require a pari passu distribution. What is required is a better return to creditors than an immediate winding up. That object is met if some creditors are better off than in a winding up and none are worse off under the DOCA than they would be under a winding up: Fleet Broadband (at [62]); and

(d) when deciding whether a deed unfairly prejudices or discriminates against a creditor or group of creditors, consideration must be given to what those purportedly prejudiced creditors would receive, or would be likely to receive, on a winding up, and the reasonableness of any conclusions reached by the administrator on that question: Lam Soon Australia Pty Ltd v Molit (No 55) Pty Ltd (1996) 70 FCR 34 (at 50); TNT Building (at [43]).

203 In respect of determining what is unfairly discriminatory:

(a) there must be reasonable grounds for differentiation between creditors of an equal class (for example, ordinary unsecured creditors) that accord with the object and spirit of Pt 5.3A: Lam Soon (at 46-48). Circumstances may exist where certain creditors must be paid in full to ensure their continued support for the company to allow it to continue to trade: Employers’ Mutual Indemnity (Workers’ Compensation) Ltd v JST Transport Services Pty Ltd (1997) 72 FCR 450 per Branson J (at 464-465 applying Lam Soon);

(b) there will be circumstances when ordinary commercial common sense will demand, in the case of priority creditors, a loss of priority and, in the case of unsecured creditors, some degree of discrimination: Commonwealth v Rocklea Spinning Mills Pty Ltd (2005) 145 FCR 220 per Finkelstein J (at [25]);

(c) where a deed proposes to preserve the company to achieve the objects of Pt 5.3A of the Corporations Act, there should be no expectation of equal treatment of unsecured creditors where such treatment would defeat that purpose: Rocklea per Finkelstein J (at [30]).

(d) ultimately, if there is no prima facie evidence of misfeasance, concealment or a materially inadequate preliminary examination, and the DOCA offers both real financial benefits credibly estimated on preliminary investigation to exceed those available on liquidation, and indirect or collateral benefits from the survival of the company’s business; and no worthwhile avenues for further recovery in liquidation are identified, a major creditor’s curiosity or preference for further exploration of speculative claims is unlikely to render termination of the DOCA in the interests of the creditors as a whole: Mediterranean Olives (at [195]).

65 The question of whether the creditors bound by a DOCA will be “better off” in a winding up is significant to the question of whether the deed involves relevant unfairness: TNT Building Trades Pty Ltd v Benelong Developments Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) [2012] NSWSC 766 at [43]. The question of fairness requires the Court to consider the whole circumstances of a case and evaluate whether there is overall unfairness in the proposal: Hagenvale Pty Ltd v Depela Pty Ltd And Another (1995) 17 ACSR 139 at 151.

Section 445D(1)(f)(ii) – contrary to interests of the creditors as a whole

66 Section 445D(1)(f)(ii) will be satisfied if the deed, or a provision of it, is contrary to the interests of the creditors of the company as a whole. Although there are two limbs to s 445D(1)(f), the subsection is often considered in combination as there are overlapping factors relevant to a consideration of each limb. In TiVo, Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd (subject to deed of company arrangement) [2014] FCA 789, Gordon J, then a judge of this Court, said at [54]:

54 In deciding whether a DOCA is oppressive, unfairly prejudicial and/or unfairly discriminatory, and/or contrary to the interests of the creditors as a whole, the courts have regard to factors including:

1. the object of Pt 5.3A;

2. the interests of other creditors, the company and the public;

3. the comparable position of the creditor on a winding-up, compared with their position under the deed; and

4. other relevant facts such as the relative position of all creditors under the deed (ie whether they are better off), the existence of a collateral benefit to the shareholders and the whole of the effect of the deed.

…

67 For the purpose of s 445D(1)(f)(ii), it is not necessary to establish, on the balance of probabilities, that if the company is placed in liquidation the creditors will receive a better return. It is sufficient that there is a not unrealistic prospect that there may be a better return to creditors on a winding up than under the deed — that there is a serious case for the recovery of assets in a liquidation that would result in a better return to creditors: Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa Products Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 848; (2016) 115 ACSR 322 at [93] to [94].

68 The question of whether there is a “not unrealistic prospect” of a better recovery in a liquidation is relevant to the question of whether a deed is in “the best interests of the creditors of the company as a whole”, assessed in light of all the circumstances: Shafston Avenue Construction Pty Ltd v McCann [2020] FCAFC 85 at [91]; Decon at [165]. There are numerous other factors that the Court may take into account in determining the extent to which a deed is or is not in the best interests of the creditors of the company as a whole: Shafston Avenue Construction at [91].

Role of the Administrator

69 In the context of applications to terminate a DOCA made under s 445D(1), the administrator is the appropriate person to perform the function of contradictor. However, that is subject to the proviso that it is proper in the circumstances for the administrator to make an active defence: Sydney Land Corporation Pty Ltd v Kalon Pty Ltd (1997) 142 FLR 188 at 189; Cresvale Far East v Cresvale Securities (No 2) [2001] NSWSC 791 at [77]. Where it is appropriate to make an active defence, the administrator stands in a similar position to a liquidator who is defending an “appeal” from a decision to reject a proof of debt of a putative creditor. In such a case, the liquidator is in the role of an adversary, cast in the role of defending the assets available for distribution, but while adversarial, the liquidator is nonetheless “required to act fairly in conducting the litigation”: Tanning Research Laboratories Inc v O’Brien (1990) 169 CLR 332 at 340 to 341.

70 Where, as here, the administrator undertakes an active defence of an application to terminate a DOCA, the Court is entitled to assume that the administrator has formed the view that to do so is consistent with the administrator’s duty to act independently and impartially in the administration of that company’s affairs. Further, the Court is entitled to assume and expect that the administrator will conduct the defence fairly. It is incumbent upon administrators to ensure that information within their knowledge that is relevant to the Court reaching a just outcome is brought to the attention of the Court. If that is not through direct tender of evidence of that information, then it must be by disclosure of that information to the party seeking to challenge the deed of company arrangement. Consistently with the duty to act fairly and impartially discussed in Bovis Lend Lease v Wily at [123] to [141], the submissions advanced by an administrator on an application such as this must be balanced, accurate and not one-sided.

Principles relevant to exercising the discretion

71 There are many factors that the Court will take into account when considering if the discretion to terminate a DOCA, once enlivened, should be exercised. Many of the relevant factors in the authorities relate to the interests of creditors as a whole on the one hand, and the public interest on the other. Public interest may be understood as whether the continuation of the DOCA is conducive or detrimental to commercial morality and to the interests of the public at large. The Court must carefully balance the interests of creditors with the public interest in considering whether it is appropriate to exercise the discretion to terminate a DOCA.

72 The following non-exhaustive list of factors, drawn from the authorities, are relevant to the exercise of the Court’s discretion:

(1) Whether the creditors voted to enter into a DOCA, noting that creditors are generally taken to be in a better position to judge what is in their best interests than the Court;

(2) Whether the vote is carried by the votes of related creditors whose interests are not aligned with the unrelated creditors;

(3) Whether the information base upon which the creditors voted was materially flawed whether because it was false, misleading or otherwise omitted information;

(4) The degree to which false, misleading or omitted information had, or is likely to have had, an influence on the manner in which creditors voted;

(5) Whether creditors would be better off under a DOCA or in a liquidation;

(6) Whether the dividend under a DOCA is likely to be insignificant;

(7) Whether the continuation of the DOCA would have the effect of eroding commercial morality or public confidence in financial systems; and

(8) Whether the effect of the DOCA, once implemented, would be to permit an insolvent company to continue to trade, contrary to the public interest.

See further discussion in Bidald at [208], [273] to [276], [282], [286] to [292]; Re Sales Express Pty Ltd [2014] NSWSC 460 at [20] to [28]; Fleet Broadband Holdings Pty Ltd v Paradox Digital Pty Ltd [2005] WASC 261 at [62]; TNT Building at [43]; TiVo at [60] to [62]; Commissioner of Taxation v Comcorp Australia Ltd and others (1996) 70 FCR 356 at 400; Greek Orthodox Community of Oakleigh and District Inc v Pizzey Noble Pty Ltd (admin apptd) and others (1997) 23 ACSR 274 at 282.

73 The list of factors relevant to the Court’s exercise of the discretion is not closed. As s 445D(1) involves a discretion that must be exercised judicially, any factor that is relevant to the exercise of the discretion, having regard to the purpose of Part 5.3A of the Act, may be taken into account. There are many factors that the Court will take into account when considering if the discretion to terminate a DOCA, once enlivened, should be exercised. Some of the relevant factors are the same or similar to those which are taken into account in determining if the deed or a provision of it is oppressive, unfairly discriminatory, unfairly prejudicial or contrary to the interest of the company’s creditors as a whole under s 445D(1)(f) of the Act.

Balancing the competing interests

74 As mentioned, there is a balance to be struck between the interests of the creditors, on the one hand, and the interests of the public, on the other. In TiVo, Gordon J said at [60] to [62]:

60 The Court’s power under s 445D(1) is discretionary. There is some authority that the ‘primary consideration’ is the interest of creditors: Bidald Consulting Pty Ltd v Miles Special Builders Pty Ltd (2005) 226 ALR 510 at [272]. What is clear is that the discretion is to be exercised having regard not only to the interests of creditors as a whole but also the public interest: Emanuele v Australian Securities Commission (1995) 63 FCR 54 at 69-70; Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Portinex Pty Ltd (subject to deed of company arrangement); Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Silindale Pty Ltd (subject to deed of company arrangement); Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Dalvale Pty Ltd (subject to deed of company arrangement) (2000) 34 ACSR 391 at [105] and Bidald at [287]. ‘Public interest’ includes, in this context, whether the continuation of the DOCA is conducive or detrimental to commercial morality and to the interests of the public at large: Emanuele at 69 citing Re Data Homes Pty Ltd (in liq) and the Companies Act [1972] 2 NSWLR 22 at 26. The Court has a duty with regard to the commercial morality of the country. That duty is longstanding and exists in relation to schemes of arrangement (Re Alabama, New Orleans, Texas and Pacific Junction Railway Co [1891] 1 Ch 213 at 229-230 and 239 and Re Mascot Home Furnishers Pty Ltd (in liq); Re Spaceline Industries (Australia) Pty Ltd (in liq) [1970] VR 593 at 596), the bankruptcy of an individual (see Re Telescriptor Syndicate Ltd [1903] 2 Ch 174 at 180-1, Re Flatau [1893] 2 QB 219 at 223 and Re Zero Population Growth (Formerly David Roy Hughes) (unreported, Federal Court of Australia, Burchett J, 30 May 1990) at pg 4), the winding up of a company (Re Denistone Real Estate Pty Ltd and Companies Act [1970] 2 NSWR 327 at 329; Re Data Homes at 26 and Keay AR, McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation, (3rd ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2013) [17-007]) and deeds of company administration (Emanuele at 69).

61 Two statements in Re Hester (1889) 22 QBD 632 are worth restating. At 639 Lord Esher MR stated:

[The Court] will consider not only whether what is proposed is for the benefit of the creditors, but also whether it is conducive or detrimental to commercial morality and to the interests of the public at large ...

And at 641 Lord Justice Fry stated:

It is an idle notion that the Court is bound by the consents of the creditors. The Court has far larger and more important duties to perform than merely to consider whether the creditors have consented to the rescinding of the order. We are bound in the exercise of our discretion in such a matter, and I think I might almost say in all matters under this Act, to take a wider view. We are not only bound to regard the interests of the creditors themselves, who are sometimes careless of their best interests, but we have a duty with regard to the commercial morality of the country.

62 In Re Flatau at 222-223, Lord Esher MR referred to his judgment in Re Hester in these terms:

‘The cases are clear that the Court is not bound by the consent of all the creditors. Although the consent of all the creditors has been obtained, the Court will still consider whether what they have agreed to’ (that is, all the creditors) ‘is for the benefit of the creditors as a whole, ‘that is, for their benefit, although they have consented. The Court will protect them against their own carelessness and folly, because we know perfectly well that over and over again the creditors of a debtor are quite willing to write off their debts as bad, to write off the whole thing, and let the debtor begin again, and incur fresh debts. …

Although the context was different, the statements by the Master of the Rolls and Lord Justice Fry are equally applicable to the exercise of the discretion under s 445D(1).

REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

75 It is sufficient in the context of the present appeal to focus on those parts of the primary judgment that are relevant to grounds 3 and 4 of the appeal.

Application under s 445D(1)(a) and (c) – relevant to ground 3

76 The Sino Creditors submitted that the Administrators’ Report was materially misleading in three ways. The primary judge summarised the Sino Creditors’ contentions based on s 445D(1)(a) of the Act as follows (PJ [136] to [139]).

77 First, the Administrators’ Report substantially underestimated the Sino Creditors’ claim against Gymbaroo and, thereby, overestimated the return that the other unrelated creditors would receive under the DOCA — full payment, as opposed to payment of a small portion only, of the other unrelated creditors’ claims: PJ [137]. The primary judge concluded that the Sino Creditors’ contention was premised on the substantiation of their damages claim against Gymbaroo, a premise which the primary judge did not accept: PJ [137].

78 Secondly, the costs of the administration or winding up were underestimated and, as a result, the Administrators’ Report overestimated the return to creditors and was misleading in this sense: PJ [138]. The primary judge rejected this contention because his Honour found that the Administrators’ Report stated the assumptions which underpinned the Administrators’ estimate of the return in both scenarios: PJ [138]. The primary judge referred to page 28 of the Administrators’ Report and expressly referred to the Administrators’ assumptions as including that (1) fees would not exceed $500,000 “in a best case scenario”; and (2) there be “no ongoing or other litigation”: PJ at [138]. The assumptions to which the primary judge referred were made in the context of the winding up scenario; the relevant part of page 28 is extracted at paragraph [45] above. The primary judge noted that it was expressly stated that “if the Sino Creditors disputed the assessment of their claim, legal fees and disbursements were likely to be higher”. This appears at page 27 of the Administrators’ Report as one of the assumptions for the DOCA proposal; the relevant part of page 27 is extracted at paragraph [44] above. On this basis, the primary judge concluded that the Administrators’ Report was not misleading as to the estimated return to creditors under both scenarios once the costs of administration were taken into account: PJ [138].

79 Thirdly, the estimated realisation on the sale of Gymbaroo’s business was underestimated and, thereby, the likely return which all creditors would receive in a winding up of Gymbaroo was also underestimated: PJ [139]. The primary judge rejected the Sino Creditors’ submission, finding that the Sino Creditors had failed to substantiate their claim that the Administrators’ Report understated the likely value on realisation of Gymbaroo’s business: at PJ [139].

Application under s 445D(1)(f)(i) or (ii) – relevant to ground 4

80 In addressing the Sino Creditors’ application under s 445D(1)(f) of the Act, the primary judge said that the Sino Creditors’ principal complaint was that the DOCA extinguished the Sino Creditors’ claim, but preserved the Related Party Creditors’ debts. The primary judge concluded that extinguishment of the Sino Creditors’ claims was not unfairly discriminatory against them for the following reasons (PJ [146] to [148]):

146 The submission ignores the evidence that the related parties had entered into a deed of subordination and forbearance on 11 April 2022, which provided for the related party debts to be subordinated to the debts of the unsubordinated creditors for a period of three years, to 11 April 2025. As a consequence, the Company and Dr Williams agree not to prove or claim its debts in competition with any unsubordinated creditor in the event of the Company’s insolvency or liquidation.

147 For the reasons already given, I do not accept that the Sino Creditors have established that they have a ‘very substantial damages claim against the Company’.

148 I also reject this claim that the DOCA is unfairly discriminatory or unfairly prejudicial to the interests of the Sino Creditors. Under the terms of the DOCA, the related party creditors agree not to participate in the distribution so that the dividend available to Participating Creditors is increased. Further, as a consequence of the operation of the deed of subordination, the related party creditors agree, as outlined above, to subordinate their debt to the debts of the unsubordinated for a period of three years. I am satisfied on the evidence that the non-participation of the related party creditors increases the pool of funds available to Participating Creditors. The evidence is that under the terms of the DOCA, on the basis of the proofs as assessed by the Administrators, unsecured creditors stand to receive an estimated 100 cents in the dollar. I have found the Sino Creditors have not established that they have a substantial damages claim against the Company and that Mr Rathner was justified in admitting the Sino Creditors’ damages claim for $1. I have also found that the quantum of the Sino Creditors’ alleged damages claim rises no higher than mere assertion. The Sino Creditors did not establish on the evidence that they will be worse off under a DOCA than in an immediate liquidation of the Company. Accordingly, I find that the DOCA is not unfairly discriminatory or unfairly prejudicial to the Sino Creditors.

(emphasis added)

81 It is evident from the last passage quoted from the primary judge’s reasons (PJ [148]) and in other parts of his reasons (PJ [142]) that the primary judge accepted the Administrators’ submission to the effect that “under the DOCA, unrelated creditors stood to receive an estimated 100 cents in the dollar”. In reaching the conclusions expressed at PJ [148], the primary judge accepted and gave weight to the submissions the Administrators made concerning the estimated returns to unrelated creditors set out in an aide memoire that was handed up in the proceedings below. We will return to the aide memoire in considering the fourth ground.

Application under s 75-41 of the IPS

82 It is necessary to address one aspect of the primary judge’s reasons in relation to the Sino Creditors’ application under s 75-41 of the IPS in the context of the fourth ground. It will be recalled that the primary judge’s rejection of the claim under s 75-41 of the IPS is challenged by the fifth ground. It is relevant to the fourth ground because the respondents submit that it can be inferred, based on the primary judge’s reasoning in relation to the claim under s 75-41 of the IPS, that even if the primary judge was satisfied that the discretion under s 445D(1) was enlivened (which his Honour was not), his Honour would in any event have declined to exercise the discretion to terminate the DOCA. The respondents rely on the following portion of the primary judge’s reasons in relation to s 75-41 (PJ [157] to [158]):

157 The Sino Creditors accept that there is a significant overlap and parity of consideration between s 75-41 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule and the question of whether a DOCA is oppressive or unfairly prejudicial or discriminatory for the purpose of s 445D(1)(f)(i) of the Act. The Sino Creditors rely upon the same matters that they relied upon under s 445D to submit that the Court ought exercise its discretion to set aside the DOCA resolution.

158 For the same reasons that I rejected terminating the DOCA under s 445D as variously stated in my Reasons above, I will not exercise my discretion under s 75-41 of the IPR to set aside the DOCA resolution.

83 The Sino Creditors contend that the primary judge did not proceed to consider whether to exercise the discretion to terminate the DOCA under s 445D because, not being satisfied that the conditions in s 445D(1) were established, the discretion was not enlivened. The primary judge did not state, in terms, that he had declined to exercise the discretion. The respondents submit that on a fair reading of the primary judge’s reasons it is open to conclude that, had any of the s 445D(1) grounds been established, the primary judge would have declined to exercise the discretion on the s 445D application. The respondents rely on the primary judge’s statement at PJ [158] that for “the same reasons that I rejected terminating the DOCA under s 445D as variously stated in my Reasons above, I will not exercise my discretion under s 75-41 of the IPR (sic) to set aside the DOCA resolution”. We reject the respondents’ submissions.

84 It is tolerably clear that the primary judge did not proceed to the second stage of considering whether to exercise the discretion under s 445D and to conclude, as the respondents urge, that had the primary judge been satisfied that the discretion was enlivened, he would have declined to exercise it, invites speculation. What the primary judge would have done if he reached the requisite state of satisfaction as to the discretion being enlivened would depend on the jurisdictional facts found. For the reasons given at [87] to [88] below, if House v R error is established such that the discretion is enlivened then it falls to this Court to exercise the discretion on the basis of the jurisdictional facts which are established.

GROUNDS OF APPEAL

85 The grounds of appeal are summarised above. It is sufficient for present purposes to extract in full only grounds 3 and 4:

3. Further, the primary judge:

(a) erred in not finding ([J] at [137] – [139]) that:

(i) information about the Company’s business, property, affairs or financial circumstances that was false or misleading, and can reasonably be expected to have been material to creditors of the Company in deciding whether to vote in favour of the resolution that it execute the DOCA, was given to those creditors within the meaning of section 445D(1)(a) of the Act; and/or

(ii) there was an omission from the Administrators’ report to creditors accompanying the notice of the meeting (Annexure GIR-33 to Rathner 6) (Report) that can reasonably be expected to have been material to such creditors in so deciding within the meaning of section 445D(1)(c) of the Act; and

(b) should have found that such false or misleading information was given to creditors, and/or there was such an omission from the Report, in that the estimated return to participating creditors under the DOCA would not be 100 cents in the dollar once the following were taken into account:

(i) the value of the Sino Creditors’ damages claim against the Company for breaches of the master licence agreement ([J] at [137]); and/or

(ii) the likely Administrators’ and Deed Administrators’ costs ([J] at [138], [148]).

4. Further, the primary judge:

(a) erred in failing to apply the correct test under section 445D(1) of the Act in respect of the interests of creditors, namely, whether there would likely be a return to the Company’s creditors on a winding up that is better than under the DOCA; and

(b) should have found that the DOCA was contrary to the interests of the Company’s creditors as a whole under section 445D(1) of the Act and/or within the meaning of s 445D(1)(f)(i) or (ii) of the Act on the basis that there would likely be a return to the Company’s creditors on a winding up that is better than under the DOCA in circumstances where ([J] at [148]):

(i) the Administrators had received a $1.15 million arms-length offer for the Company’s assets (including trade debtors) in a short time frame following an expression of interest campaign ([J] at [153]) and relied on a valuation of the Company prepared by its accountants for $1 million (not including trade debtors) as at 30 June 2021 based upon estimated maintainable EBITDA of $400,000 per annum with an earnings multiple of 2.5 times (Annexure GIR-20 to Rathner 4); and

(ii) the related parties had entered into a deed of subordination and forbearance on 11 April 2022 (after the first day of trial) which provided for their debts to be subordinated to all other debts of the Company for a period of three years, to 11 April 2025, and the related parties would not prove or claim for their subordinated debts in competition with any other creditors of the Company in the event of the Company’s insolvency or liquidation ([J] at [146]).

86 If either or both of the third and fourth grounds succeed, such that the Court concludes that the primary judge erred in finding that the conditions in s 445D(1) were not met and the discretion to terminate the DOCA was in fact enlivened, then it will be necessary for this Court to decide whether the discretion should be exercised to terminate the DOCA.

LEGAL PRINCIPLES: APPELLATE REVIEW OF DECISIONS UNDER S 445D

87 Appellate review of a decision made under s 445D of the Act is confined by the principles in House v R. In Decon Australia Pty Ltd v TFM Epping Land Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 54 at [144] to [147], the Full Court said:

APPELLATE REVIEW UNDER S 445D(1)

144 Section 445D involves a two stage process. The first stage is to determine whether one of the grounds referred to in sub-s (1) has been established and, if it has, the second stage is to decide whether to exercise the discretion to terminate the DOCA based on that ground. See Britax Childcare Pty Ltd v Infa Products Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 848; (2016) 115 ACSR 322 (Burley J) at 342 [90]; Shafston Avenue Construction Pty Ltd v McCann [2019] FCA 1426; (2019) 138 ACSR 299 at 336 [130] (Reeves J). In this case, as is tolerably clear from his Honour’s reasons, he found that none of the s 445D(1) grounds relied upon by Decon was established, so he did not proceed to the second stage.

145 In determining whether it is satisfied of any of the criteria set out in s 445D(1), a court makes an objective evaluation of the relevant circumstances viewed as a whole. Accordingly, appellate review of a decision made under that provision is confined by the principles in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 504–505 in respect of discretionary decisions, viz:

The manner in which an appeal against an exercise of discretion should be determined is governed by established principles. It is not enough that the judges composing the appellate court consider that, if they had been in the position of the primary judge, they would have taken a different course. It must appear that some error has been made in exercising the discretion. If the judge acts upon a wrong principle, if he allows extraneous or irrelevant matters to guide or affect him, if he mistakes the facts, if he does not take into account some material consideration, then his determination should be reviewed and the appellate court may exercise its own discretion in substitution for his if it has the materials for doing so. It may not appear how the primary judge has reached the result embodied in his order, but, if upon the facts it is unreasonable or plainly unjust, the appellate court may infer that in some way there has been a failure properly to exercise the discretion which the law reposes in the court of first instance. In such a case, although the nature of the error may not be discoverable, the exercise of the discretion is reviewed on the ground that a substantial wrong has in fact occurred.

146 As the Full Court said in Wilmar Sugar Australia Ltd v Mackay Sugar Ltd [2017] FCAFC 40; (2017) 345 ALR 174 at 189 [46] in the context of s 232 of the Act (oppressive conduct), ‘it is the character of the decision, involving as it does the weighing of potentially competing considerations and an overall contextual evaluation of the effect of the conduct, which requires the same approach to appeals as in [House v R]’.

147 As Mason CJ and Deane and McHugh JJ explained in Singer v Berghouse (1994) 181 CLR 201 at 212 (quoting Kirby P in Golosky v Golosky [1993] NSWCA 111) an appeal from a decision on a jurisdictional question of this type should be governed by the principles that regulate appeals from decisions made in the exercise of a discretion because:

[u]nless appellate courts show restraint in disturbing the evaluative determinations of primary decision makers they will inevitably invite appeals to a different evaluation which, objectively speaking, may be no better than the first. Second opinions in such cases would be bought at the cost of diminishing the finality of litigation in a troublesome area and, sometimes at least, with a burden of costs upon the estate which should not be encouraged.

88 This is an appeal by way of rehearing: s 27, Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act). If House v R error is established, this Court is in as good a position as the primary judge to determine the proper inferences to be drawn from undisputed facts or the facts as established and, after giving due respect and weight to the conclusions of the primary judge, if the conclusion is considered wrong, this Court should not shrink from giving effect to it: Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [25]; Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; (2001) 117 FCR 424 at [28].

CONSIDERATION

Ground 3

89 The third ground asserts that the primary judge erred in not finding that the Administrators’ Report was materially misleading or omitted material information within the meaning of ss 445D(1)(a) and 445D(1)(c) of the Act where it estimated that unrelated creditors would receive a return of 100 cents in the dollar. It is alleged that this material is misleading because it failed to take into account the true value of the Sino Creditors’ claims for breach of the MLA and / or the likely Administrators’ costs of the administration and administering the DOCA. It is sufficient to address the latter of the two particulars which is directed to the likely costs of the DOCA and how this impacted the headline comparator of 100 cents in the dollar.

90 The Administrators’ Report states that the estimated return of 100 cents in the dollar in the DOCA scenario is based on certain assumptions. These include that the Sino Creditors do not dispute the assessment of their claims and that there is no continuing or other litigation. Further, that the Administrators’ “fees do not exceed $310,000 in a best case scenario” (page 27, Administrators’ Report). Although identifying assumptions upon which the estimate is based, the statement: “It is estimated that under the proposed DOCA, Participating Creditors will receive a dividend of 100 cents in the dollar” is not qualified. There is no statement of the relative probability of the best case scenario eventuating, or the risk that it may not eventuate. Further, in relation to the DOCA, there is no comparison between a best case and a worst case scenario. The report gives the reader the impression that the Administrators considered that the best case scenario was the most likely outcome if the DOCA proposal was accepted.