FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Fisher v Commonwealth of Australia [2023] FCAFC 106

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent MINISTER FOR GOVERNMENT SERVICES Second Respondent MINISTER FOR FAMILIES AND SOCIAL SERVICES Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The questions of law in the amended special case set out in Annexure B of the orders of the docket judge dated 9 December 2022 be answered as follows:

(1) Do the Applicant and each of the represented persons have the same interest in the proceeding, save for the relief set out in paragraph 2 of the amended originating application?

Answer: Yes.

(2) Do:

a. the Applicant; and, or alternatively

b. the represented persons,

enjoy the right to apply for and receive the age pension “to a more limited extent” (within the meaning of that expression in s 10 of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)) than non-Indigenous men born on or between 1 January 1957 and 31 December 1957, by reason of:

c. ss 23(5A) and 43 of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth); or

d. alternatively, s 3 and Schedule 11, item 1, of the Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Pension Reform and Other 2009 Budget Measures) Act 2009 (Cth) (as it applied to item 5 of the table in s 23(5A) of the Social Security Act)?

Answer: No.

(3) If the answer to Question 2 is yes, does s 10 of the Racial Discrimination Act operate such that the “pension age” for:

a. the Applicant; and, or alternatively

b. the represented persons,

for the purposes of item 5 of the Table appearing in s 23(5A) of the Social Security Act, and for the purposes of s 43 of the Social Security Act, is:

c. 64 years of age?

d. Any other age less than 67 years of age?

Answer: Does not arise.

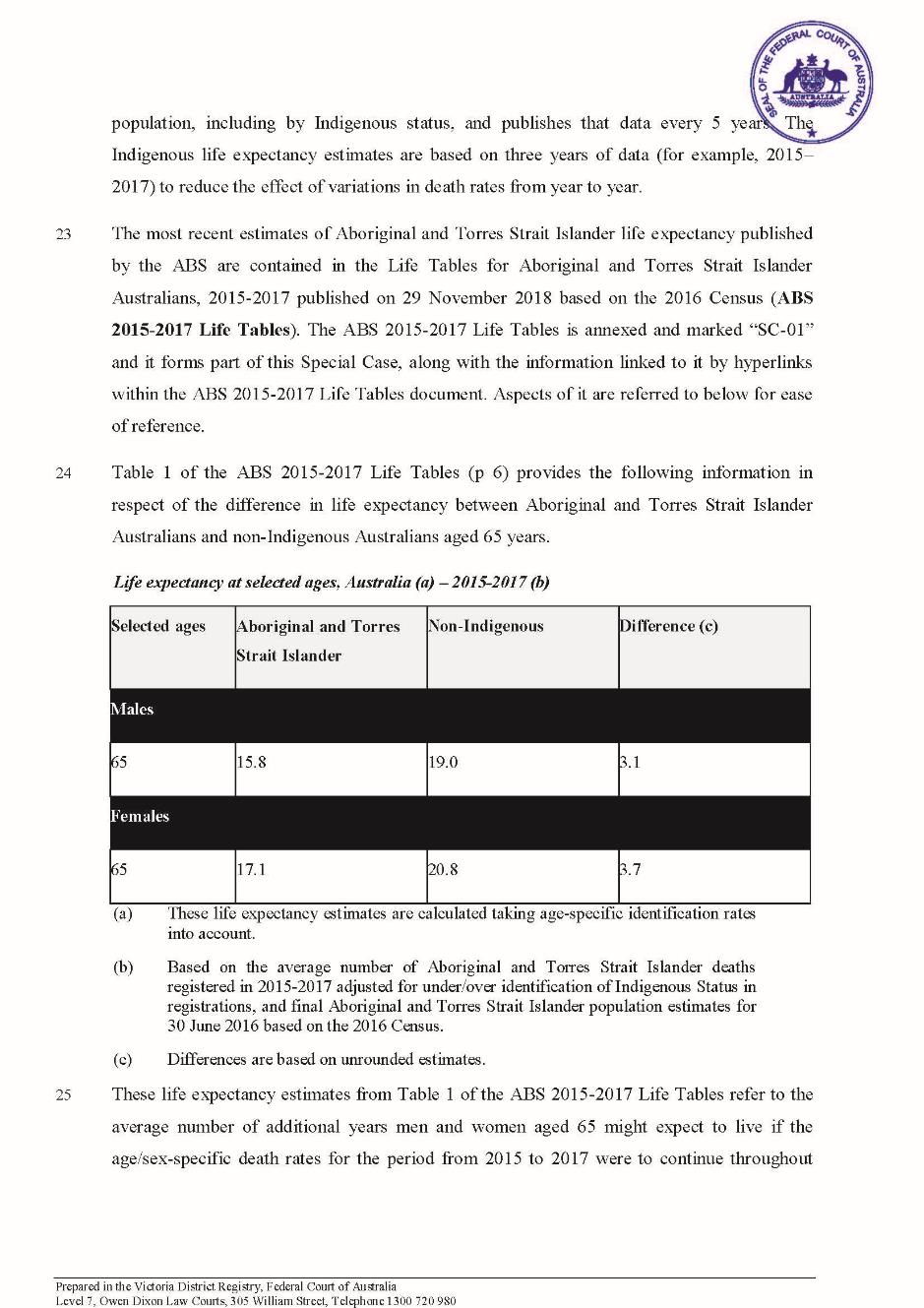

2. Within 35 days, each party file and serve a short written submission on any further orders that they contend should be made by the Full Court.

3. Subject to order 2, the proceeding otherwise be referred back to a docket judge for case management.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 INTRODUCTION

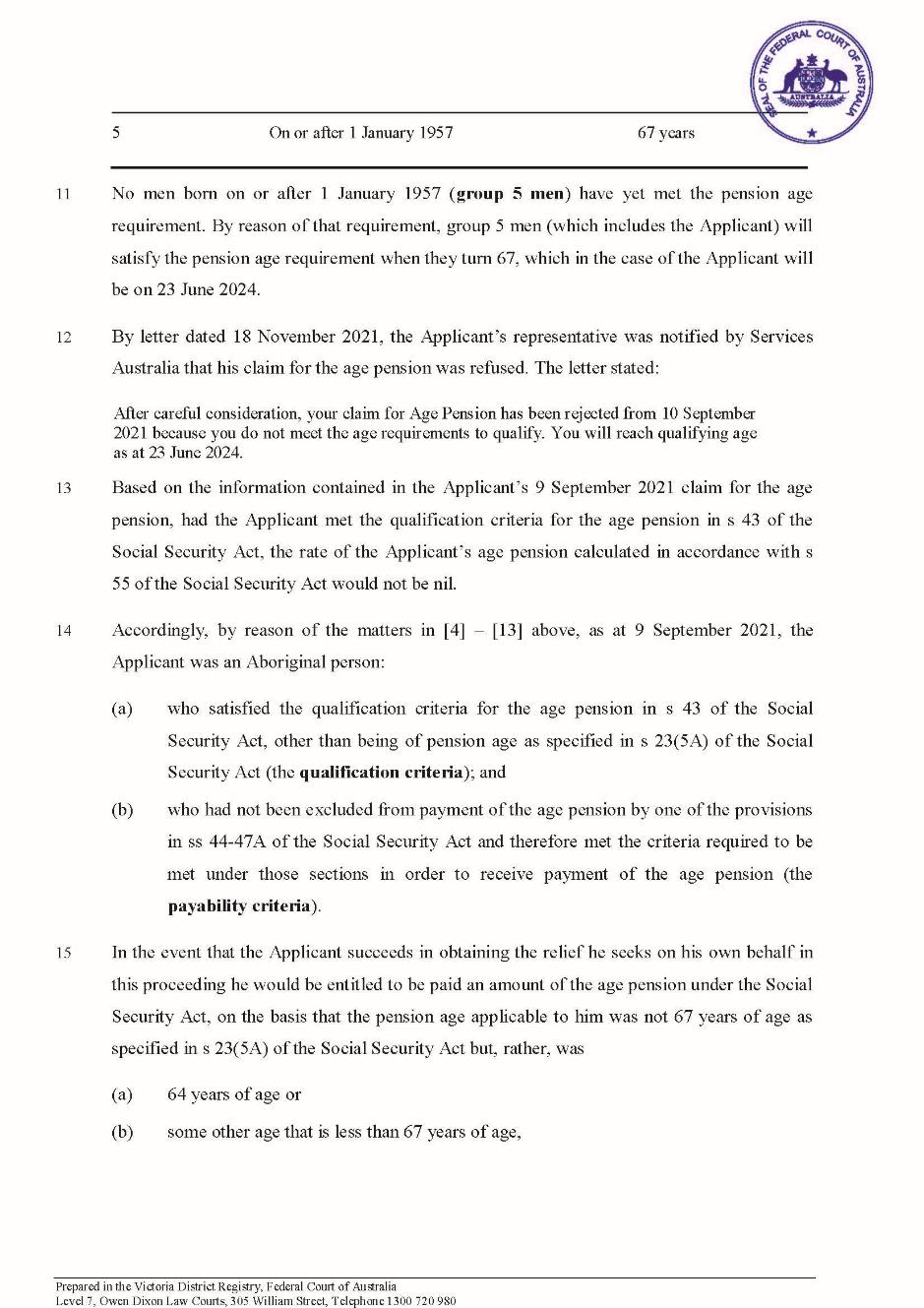

1 The applicant is an Aboriginal man who was born on 23 June 1957 and is now 66 years old.

2 Pursuant to s 43(1) of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth) (SSA), a person qualifies to receive the age pension when they reach the “pension age”, if one of four defined circumstances is present. The applicant meets the criterion in s 43(1)(a), having been resident in Australia for more than 10 years.

3 The “pension age” is defined by s 23(1) of the SSA. For a man born after 1 January 1957 it is 67 years. Accordingly, if the SSA is applied according to its terms, the applicant will qualify to receive the age pension on 23 June 2024. Whether a pension actually becomes “payable” to him will depend, under s 44, on whether his “pension rate” is greater than nil. Under s 55, the pension rate is worked out using either Pension Rate Calculator A (which appears at the end of s 1064) or Pension Rate Calculator B (which appears at the end of s 1065).

4 The applicant lodged a claim for the age pension on 9 September 2021. It was refused and no pension has been paid to him. He argues that, despite the terms of the provisions relating to the “pension age” in the SSA, he is entitled to be treated as meeting the qualification criteria for the age pension. This result is said to flow from the shorter life expectancy that Aboriginal men have, compared to other men in Australia, and the application of s 10(1) of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (RDA). Put shortly, he says that s 10(1) requires that Aboriginal people, if they otherwise meet the relevant criteria in the SSA, receive the age pension for the same duration as other people. In broad terms, that is said to mean that an Aboriginal man born in 1957 qualified for the age pension when he reached 64 years of age. The applicant seeks declarations and an injunction to vindicate that position.

5 The proceeding is currently constituted as a representative proceeding under r 9.21 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) and some of the issues between the parties relate to whether it should continue to be constituted in that way. Again in broad terms, the represented persons are Indigenous (that is, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) men who turned 65 in 2022 and who, if the applicable pension age is 64 rather than 67, meet the qualification and payability criteria and are thus entitled to receive a pension. (Aboriginal women are not included in the group of represented persons; however, if the applicant’s argument is upheld, it will be able to be relied on to some degree by them as well. The pension age for women in the relevant age group is the same (67 years) but the relevant life expectancy statistics are not the same.)

6 On 9 December 2022, pursuant to r 38.01 of the Rules, Mortimer J (as her Honour then was) referred an amended special case for the consideration of the Full Court (the special case). The special case states the following questions of law:

Question 1

Do the Applicant and each of the represented persons have the same interest in the proceeding, save for the relief set out in paragraph 2 of the amended originating application?

Question 2

Do:

(a) the Applicant; and, or alternatively

(b) the represented persons,

enjoy the right to apply for and receive the age pension “to a more limited extent” (within the meaning of that expression in s 10 of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)) than non-Indigenous men born on or between 1 January 1957 and 31 December 1957, by reason of:

(c) ss 23(5A) and 43 of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth); or

(d) alternatively, s 3 and Schedule 11, item 1, of the Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Pension Reform and Other 2009 Budget Measures) Act 2009 (Cth) (as it applied to item 5 of the table in s 23(5A) of the Social Security Act)?

Question 3

If the answer to Question 2 is yes, does s 10 of the Racial Discrimination Act operate such that the “pension age” for:

(a) the Applicant; and, or alternatively

(b) the represented persons,

for the purposes of item 5 of the Table appearing in s 23(5A) of the Social Security Act, and for the purposes of s 43 of the Social Security Act, is:

(c) 64 years of age?

(d) any other age less than 67 years of age?

7 The special case sets out over the course of 98 paragraphs the facts which the parties have agreed for the purpose of deciding these questions. A significant body of documentary material is annexed. The key points are these:

(a) According to life tables compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics based on data for 2015 to 2017, an Indigenous man aged 65 had a remaining life expectancy of 15.8 years. A non-Indigenous man of the same age had a life expectancy of 19.0 years (special case at [24]).

(b) From 2006 to 2018, mortality rates for Indigenous people improved at a similar rate to mortality rates for non-Indigenous people, so that the gap in life expectancy has not narrowed (at [26]).

(c) “The reason for the shorter life expectancies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians is … that they experience greater adverse health outcomes compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Those outcomes are shaped by a range of interconnected structural, social and cultural determinants of health, including the historical and ongoing consequences of colonisation. As such, the gap in life expectancy between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and their non-Indigenous counterparts is a function of race.” (At [29]).

8 The gap in life expectancy arising from the figures in [7(a)] above is the one that is of direct relevance to the resolution of this proceeding. It is worth noting, however, that this reflects the statistical expectations for men who have survived all of the risks associated with life and reached the age of 65. As reflected in the same tables, life expectancy at birth was 71.6 years for an Indigenous male and 80.2 years for a non-Indigenous male. That reflects greater rates of mortality for Indigenous males at all stages of life.

9 The expression “a function of race” is somewhat imprecise and needs elaboration. As the succeeding paragraphs of the special case explain, Indigenous Australians suffer to a greater degree than others from a range of physical and mental health problems which contribute to mortality rates and thus life expectancy. The facts agreed by the parties do not suggest that these disparities arise from something inherent in Indigenous people or their cultures that make them inherently likely to live shorter lives than other people. Rather, to the extent that underlying causes are identified, those causes are connected to the ongoing effects of colonisation, dispossession, destruction of cultural bonds, poor access to services and racist policies. Thus, the gap in life expectancy is “a function of race” in the sense that it is (so far as the facts disclose) the product of disadvantages suffered by Indigenous Australians which, in turn, flow from their treatment by governments and by more powerful or fortunate Australians.

10 These facts, which the Australian government accepts for the purposes of the proceeding to be true, are a matter of grave concern for a society that values equality of opportunity. For that reason, as well as to give proper context to the short summary above, the statement of agreed facts contained in the special case is extracted (without its own annexure marked SC-01) and included as an annexure to these reasons.

2 SECTION 10 OF THE RDA

11 The key provisions of Pt II of the RDA are as follows:

9 Racial discrimination to be unlawful

(1) It is unlawful for a person to do any act involving a distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of any human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

(1A) Where:

(a) a person requires another person to comply with a term, condition or requirement which is not reasonable having regard to the circumstances of the case; and

(b) the other person does not or cannot comply with the term, condition or requirement; and

(c) the requirement to comply has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, by persons of the same race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin as the other person, of any human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life;

the act of requiring such compliance is to be treated, for the purposes of this Part, as an act involving a distinction based on, or an act done by reason of, the other person’s race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin.

(2) A reference in this section to a human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life includes any right of a kind referred to in Article 5 of the Convention.

…

10 Rights to equality before the law

(1) If, by reason of, or of a provision of, a law of the Commonwealth or of a State or Territory, persons of a particular race, colour or national or ethnic origin do not enjoy a right that is enjoyed by persons of another race, colour or national or ethnic origin, or enjoy a right to a more limited extent than persons of another race, colour or national or ethnic origin, then, notwithstanding anything in that law, persons of the first‑mentioned race, colour or national or ethnic origin shall, by force of this section, enjoy that right to the same extent as persons of that other race, colour or national or ethnic origin.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to a right includes a reference to a right of a kind referred to in Article 5 of the Convention.

…

12 Sections 9 and 10 are qualified by s 8, which is (relevantly) as follows:

(1) This Part does not apply to, or in relation to the application of, special measures to which paragraph 4 of Article 1 of the Convention applies except measures in relation to which subsection 10(1) applies by virtue of subsection 10(3).

…

13 The Convention, referred to in these provisions, is the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature 21 December 1965, 660 UNTS 195 (entered into force 4 January 1969) (the Convention), the text of which is contained in the Schedule to the RDA. Its key provisions are as follows.

(a) Paragraph 1 of art 1 defines the concept of “racial discrimination” to mean:

In this Convention, the term “racial discrimination” shall mean any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

(b) Paragraph 4 of art 1 (which forms the basis for s 8 of the RDA) provides:

Special measures taken for the sole purpose of securing adequate advancement of certain racial or ethnic groups or individuals requiring such protection as may be necessary in order to ensure such groups or individuals equal enjoyment or exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms shall not be deemed racial discrimination, provided, however, that such measures do not, as a consequence, lead to the maintenance of separate rights for different racial groups and that they shall not be continued after the objectives for which they were taken have been achieved.

(c) By art 2, the States Parties condemn racial discrimination and undertake to pursue a policy of eliminating it. Relevantly for present purposes, para 1(c) of art 2 provides:

Each State Party shall take effective measures to review governmental, national and local policies, and to amend, rescind or nullify any laws and regulations which have the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination wherever it exists;

…

(d) In art 5, the States Parties undertake to do two things: to prohibit and eliminate “racial discrimination in all its forms” (the basis for s 9 of the RDA); and (relevantly to s 10):

… to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, to equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of the following rights:

(a) The right to equal treatment before the tribunals and all other organs administering justice;

(b) The right to security of person and protection by the State against violence or bodily harm, whether inflicted by government officials or by any individual, group or institution;

(c) Political rights, in particular the rights to participate in elections – to vote and to stand for election – on the basis of universal and equal suffrage, to take part in the Government as well as in the conduct of public affairs at any level and to have equal access to public service;

(d) Other civil rights, in particular:

(i) The right to freedom of movement and residence within the border of the State;

(ii) The right to leave any country, including one’s own, and to return to one’s country;

(iii) The right to nationality;

(iv) The right to marriage and choice of spouse;

(v) The right to own property alone as well as in association with others;

(vi) The right to inherit;

(vii) The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion;

(viii) The right to freedom of opinion and expression;

(ix) The right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association;

(e) Economic, social and cultural rights, in particular:

(i) The rights to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work, to protection against unemployment, to equal pay for equal work, to just and favourable remuneration;

(ii) The right to form and join trade unions;

(iii) The right to housing;

(iv) The right to public health, medical care, social security and social services;

(v) The right to education and training;

(vi) The right to equal participation in cultural activities;

(f) The right of access to any place or service intended for use by the general public such as transport, hotels, restaurants, cafes, theatres and parks.

2.1 Section 10: Introductory observations

14 Section 10 of the RDA differs from s 9 in two important ways. First, while s 9 prohibits conduct, s 10 is directed at the operation of laws. Section 10 therefore cannot be contravened in the way that s 9 can. Secondly, while s 9 is expressly based on the concept of discrimination (including what is often referred to as indirect discrimination, which is the subject of s 9(1A)), s 10 is not. The latter section is expressed to apply where there is an unequal enjoyment, as between members of different races, of a relevant “right”. That does not mean that concepts of discrimination are irrelevant, however. Section 10 sits alongside s 9 in a statutory regime squarely directed at that phenomenon. Both provisions use as the touchstone for their operation the impairment of the enjoyment of basic or fundamental human rights, in circumstances where that impairment is connected, directly or indirectly, to race: see Mabo v Queensland [1988] HCA 69; 166 CLR 186 at 216–217 (Brennan, Toohey and Gaudron JJ) (Mabo No 1).

15 Section 10, applying as it does to a law of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory, can have different effects in different circumstances.

(a) Where a law of a State limits or partially abrogates a pre-existing domestic law right in a way that leads to the unequal enjoyment of a human right as between members of different races, it is inconsistent with s 10 and is therefore rendered inoperative (in whole or in part) by s 109 of the Constitution (eg Gerhardy v Brown [1985] HCA 11; 159 CLR 70 at 98–99 (Mason J) (Gerhardy); Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28; 213 CLR 1 at [107]–[108] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ) (Ward)). The same consequence occurs in respect of a law enacted by a Territory legislature, by force of provisions of Territory self-government legislation that give Commonwealth Acts primacy (see, eg, Bara v Blackwell [2022] NTCCA 17 at [20] (Bara)).

(b) If a law of the Commonwealth enacted after 1975 is said to abrogate or restrict a right inconsistently with s 10, issues will arise as to whether it thereby effects an implied partial repeal (cf, eg, Ward at [99]).

(c) On the other hand, where a law (of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory) confers or expands a right which gives effect to a relevant human right, but omits to do so universally, s 10(1) has the effect of extending or augmenting that conferral to the extent necessary to eliminate the inequality of its enjoyment between people of different races. In Gerhardy at 98 (in a passage adopted by the majority in Ward at [106]) Mason J said:

If racial discrimination arises under or by virtue of State law because the relevant State law merely omits to make enjoyment of the right universal, i.e. by failing to confer it on persons of a particular race, then s. 10 operates to confer the right on persons of that particular race.

16 It is the third area of s 10’s operation that is engaged here, if the applicant’s submissions are accepted.

17 In very broad terms, the applicant submits that s 10(1) is engaged whenever a law confers a right in a way that results in members of different races enjoying the relevant human right to different extents. That includes the case where a law applies a neutral criterion but, because members of a particular race find themselves in different circumstances to other members of the community, they do not meet or are less likely to meet that criterion. The Commonwealth submits that such a far-reaching operation cannot have been intended and that s 10 applies in a more limited way: when the law is expressly framed so as to apply distinctly or differentially to members of a particular race; or when the law is facially neutral but, when seen in context, is found to target members of a particular race.

18 Before turning to the issues of construction that arise, five general points should be made about s 10(1).

19 The first general point is that the purpose of the RDA — and in particular the substantive provisions in Pt II — is to implement the Convention. Its provisions are to be construed accordingly. To the extent that the language of the RDA permits, it is to be construed so as to be consistent with the Convention: Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) ss 15AA and 15AB; Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v QAAH of 2004 [2006] HCA 53; 231 CLR 1 at [34]. It must be borne in mind, however, that it is the RDA that forms part of the law of Australia and not the Convention itself (see, eg, Maloney v the Queen [2013] HCA 28; 252 CLR 168 at [174] (Kiefel J) (Maloney); Dietrich v The Queen [1992] HCA 57; 177 CLR 292 at 305 (Mason CJ and McHugh J), 359–360 (Toohey J)).

20 No question concerning the validity of the RDA arises in this case. However, it is useful to note the basis upon which the Act has been regarded as within the Commonwealth’s legislative power, as it has some relevance for the task of construction. Sections 9 and 12 of the RDA were upheld as valid enactments under s 51(xxix) of the Constitution (the external affairs power) in Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen [1982] HCA 27; 153 CLR 168 (Koowarta). As described more recently in Maloney at [61] (Hayne J), the holding in Koowarta is that the RDA is a valid enactment because it implements Australia’s obligations under the Convention. This observation emphasises the need for provisions of the RDA to be construed consistently with the Convention.

21 Although the Preamble to the RDA suggests an attempt to rely on “all relevant powers of the Parliament”, including s 51(xxvi) and s 51(xxvii) of the Constitution (“the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws” and “immigration and emigration”), the attempt to rely on the races power as an additional foundation seems to have been unsuccessful (Koowarta at 187 (Gibbs CJ), 211 (Stephen J), 244–245 (Wilson J), 261–262 (Brennan J)). It does not appear to have affected the understanding, reflected in the authorities, that the purpose of the RDA is to implement the Convention. Section 10 itself has been described as intending to comply with or implement art 2.1(c), art 5 or both: see Gerhardy at 95 (Mason J); Viskauskas v Niland [1982] HCA 15; 153 CLR 280 at 294 (Gibbs CJ, Mason, Murphy, Wilson and Brennan JJ); Mabo No 1 at 217 (Brennan, Toohey and Gaudron JJ); Maloney at [10] (French CJ), [161] (Kiefel J), [201] (Bell J), [303] (Gageler J).

22 The second general point is that s 10(1) is a remedial statute directed, at a fundamental level, to the protection of human dignity. It is therefore “not to be given a legalistic or narrow interpretation” (Mabo No 1 at 230 (Deane J); Western Australia v Commonwealth (Native Title Act Case) [1995] HCA 47; 183 CLR 373, 437 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ) (Native Title Act Case)). Issues concerning the effect of laws and the equal or unequal enjoyment of relevant rights should therefore be approached as matters of substance rather than form (Maloney at [38] (French CJ), [65], [84] (Hayne J (Crennan J agreeing at [112])), [148] (Kiefel J), [204] (Bell J), [343(a)] (Gageler J)).

23 The third general point (which flows from the first point) is that the “rights” of which s 10(1) speaks are fundamental human rights. Section 10(2) directs attention to the rights listed in art 5 of the Convention. The list of rights in art 5 is introduced by the word “notably” and is therefore itself non-exhaustive. The field of operation of the Convention is identified by art 1(1), which refers to the enjoyment or exercise on an equal footing of “human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life”.

24 Despite the non-exhaustive terms of s 10(2), the “rights” to which s 10 relates have been understood to comprise human rights of the kind referred to in the Convention (eg Mabo No 1 at 216–217 (Brennan, Toohey and Gaudron JJ); Maloney at [9] (French CJ), [63] (Hayne J), [145] (Kiefel J), [300] (Gageler J)). The constitutional underpinning of the RDA and its adherence to the task of implementing the Convention indicate that the expression “right” should be taken to refer to the human rights with which the Convention is concerned, not to particular legal rights existing from time to time under domestic law.

25 The fourth general point is that “race” is a complex and in some ways problematic concept. Section 10, like the Convention, seeks to minimise such complexities by referring to “race, colour or national or ethnic origin”. While concepts of racial discrimination are well understood, identification of a particular community as a “race”, let alone who is or is not a member of it, can sometimes be fraught. However, in the context of s 10, the term is “not to be given a pedantic or narrow meaning” (Mabo No 1 at 230 (Deane J)). There is no dispute in the present case that Aboriginal Australians constitute a “race” for relevant purposes or that the applicant, and the represented persons, are members of that race. In what follows, therefore, it is possible to refer in a general way to people of a “race” without going into the complexity attending that terminology.

26 The fifth general point — albeit an obvious one — is that the ordinary canons of statutory construction apply. Effect must be given to the text enacted by Parliament, while all relevant aspects of context and accepted constructional rules must be considered in ascertaining its meaning. The section should be read as a whole, as a single enactment; the meaning of particular words or phrases can only be understood in their interaction with the rest of the section. And the section should be read together with other provisions of the RDA so as to operate, to the extent possible, in harmony with them.

27 Before going to the cases in more detail, it should be noted that the present case raises issues concerning the operation of s 10 that have received very little attention beyond the short statement by Mason J in Gerhardy set out above at [15] (and its endorsement in Ward). Arguments based on s 10 have succeeded in only a small number of cases, and all of these have involved State laws that abrogated or restricted pre-existing rights. The result was invalidity, subject to s 8. Courts have not yet had to deal in detail with questions as to how s 10 operates in the case of a statute that gives effect to a human right by creating or conferring rights under Australian law, but does so in a way that leads to unequal enjoyment of the relevant human right. These questions give rise to some complexity, which we discuss later in these reasons.

28 It is also appropriate to observe that, where the impugned law is a law of the Commonwealth made after the RDA, the issues cannot be avoided by concluding that the law is in conflict with s 10 and thus effects a partial repeal. The Commonwealth properly did not advance any submission of this kind. In truth there is no conflict, because (according to Gerhardy and Ward) s 10 confers rights in addition to, rather than in conflict with, the impugned law.

2.2 Section 10: “by reason of … a law”

29 Significant energy was expended in the Commonwealth’s submissions in attempting to construe the phrase “by reason of … a law” in s 10(1). We found this exercise unpersuasive, not only because the section must be read as a whole (cf, in relation to s 9, Wotton v Queensland (No 5) [2016] FCA 1457; 352 ALR 146 at [530] (Mortimer J)). Where the relevant human right is not capable of enjoyment except as a result of the conferral by an Australian statute of particular legal rights (as is the case here), it seems to us impossible as a matter of ordinary English to say that any unequal enjoyment of that human right does not occur “by reason of” that statute. The unequal enjoyment is necessarily a consequence of the choices that the Parliament made in designing the way in which rights would be conferred.

30 Cases such as Aurukun Shire Council v Chief Executive Officer, Office of Liquor Gaming and Racing [2010] QCA 37; [2012] 1 Qd R 1 (Aurukun), Munkara v Bencsevich [2018] NTCA 4 (Munkara) and Bara (which are discussed below) therefore have little if anything to say about this aspect of the present case. These cases involved laws that, to the extent they affected the enjoyment of human rights, were restrictive of pre-existing rights. In each case the impugned law was facially neutral and it was held that, to the extent that it affected Aboriginal persons to a greater extent than other members of the community, that was a result of social conditions or individual conduct rather than “by reason of” the law. Arguments were put in the present case as to whether these decisions could stand with the reasons of members of the High Court in Maloney. Regardless of the answer to that question, the reasoning in those cases does not support the conclusion that the unequal enjoyment of a right created by a statute does not occur “by reason of” that statute.

31 It also follows from what we have said above that we respectfully doubt the correctness of the reasoning of Goldberg and Hely JJ in Sahak v Minister for Immigration [2002] FCAFC 215; 123 FCR 514 (Sahak) at [49]. Sahak (which is also discussed below) concerned the limitation period imposed by a provision of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act) for making an application for judicial review in this Court. The provision was part of a regime conferring, and regulating access to, review rights. To the extent that those rights were enjoyed to a lesser degree by members of particular races (which was said to be the case because English was not their first language), we doubt whether that could properly be said not to be a consequence of how the review regime was designed, including as it did a relatively short and non-extendable limitation period.

32 The Commonwealth submitted that s 10(1) is engaged only where the law in question either is expressed to apply differentially on the basis of race (including by reference to rights or interests that attach to members of a race, such as native title) or is found to have adopted a facially neutral criterion as a conscious proxy for race. In light of s 10(1)’s concern with substance rather than form, and the need to give its terms a generous and non-technical construction, we do not think that the phrase “by reason of … a law” can be narrowed in that way. Internationally and in Australia, it has long been recognised that discrimination can sometimes be found in the equal treatment of that which is unequal: eg Gerhardy at 129 (Brennan J). Thus, where a legislative choice is made to apply a neutral criterion that has an unequal practical effect, it is no answer to say that such an effect does not occur by reason of the law.

2.3 Section 10: Unequal enjoyment of rights

33 A more useful (but also more complicated) question is what, in context, is meant by the reference to persons of a particular race not “enjoying” a right enjoyed by others or “enjoying” it “to a more limited extent”. These expressions lie at the heart of s 10(1) and their meaning, to a large extent, defines its reach. Is there unequal “enjoyment” of a human right, as between members of a particular race and other persons, if Australian law gives force to that right by way of racially neutral criteria but it can be shown (including by statistical analysis) to be in fact less accessible, or of less utility, to members of that race than to others? Or is the concept (as the Commonwealth submitted) limited to cases where the human right is conferred or limited in a discriminatory way, whether expressly or by adoption of some apparently neutral criterion as a proxy for race?

34 While accepting that s 10 was concerned with matters of substance rather than form, the Commonwealth emphasised that decisions of the High Court have so far found s 10 to be engaged only where the law in question singled out people of a particular race, either by expressly applying to those persons (or rights attaching to those persons) or by being, despite a facially neutral criterion, targeted at those persons.

(a) Gerhardy concerned a provision in South Australian legislation which prohibited any non-Pitjantjatjara person from entering a large tract of the State without permission. ‘Pitjantjatjara’ was defined to mean a person who is a member of particular groups and has traditional ownership rights in the land. The provision was held to be a “special measure” under s 8(1) of the RDA, but five Justices held that s 10(1) would otherwise have applied. The criterion of traditional ownership was regarded as distinguishing on the basis of race.

(b) Mabo No 1 concerned a provision of Queensland law which vested the Murray Islands in the State to the exclusion of all other rights, interests and claims. The only rights and interests thereby extinguished were those which the Meriam people claimed to hold (and were subsequently found to hold in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1 (Mabo (No 2)) under traditional law as recognised by the common law. Four Justices held that s 10(1) was engaged.

(c) In the Native Title Act Case, Western Australian statutory provisions that extinguished native title and replaced it with statutory rights were held to engage s 10(1). The new statutory rights had less protection against extinguishment and compulsory acquisition than other property rights. The majority observed that a State law purporting to authorise appropriation of property “characteristically held by persons of a particular race”, for additional purposes or on less stringent conditions than apply to the appropriation of property generally, is inconsistent with s 10(1) (at 437).

(d) Reference was also made to Ward, where the reasons of Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ referred to the earlier cases concerning native title and s 10(1) (at [117]–[121]). However, Ward was decided after the commencement of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA) and extensive amendments to that Act in 1998. The issues for decision in Ward concerned the extent to which, under the NTA, certain dealings in land were to be understood as extinguishing native title.

(e) Maloney concerned a Queensland law that prohibited the possession of alcohol in public places in Palm Island (part of the State of Queensland). The majority held that the law engaged s 10(1), but that it was a special measure within s 8(1) and therefore not inconsistent with the RDA. Maloney was characterised by the Commonwealth as a case about a facially neutral criterion chosen deliberately to achieve an outcome based on race.

2.3.1 Maloney

35 The Commonwealth’s characterisation of Maloney is correct as far as it goes, but ultimately unhelpful.

(a) It is correct because the criterion applied by the Queensland law was purely geographic: all residents of Palm Island (including a small number of non-Aboriginal persons) were affected by it in the same way; while persons of all races, in places to which the law did not apply, were unaffected by it. Simple comparisons of that kind were rejected as a basis for decision (at [77] (Hayne J), [200] (Bell J)). Instead, members of the majority on the s 10(1) point emphasised that the population of Palm Island was “overwhelmingly” Aboriginal (at [34] (French CJ), [84] (Hayne J, Crennan J agreeing), [362] (Gageler J)), or said that it did not matter that a small number of non-Aboriginal persons was affected by the law in the same way (at [200] (Bell J), [363] (Gageler J)). Bell and Gageler JJ regarded the law as “targeting” an Aboriginal community (at [202] (Bell J), [362] (Gageler J)), while Hayne J described the mischief at which the law was directed as “the evil of alcohol-fuelled violence in [Indigenous] communities” (at [58]). Thus, in our view, the explanation for the majority’s conclusion that the impugned law in Maloney engaged s 10(1) appears to be that their Honours were prepared to look beyond both its text and its immediate operation, and find that geography was being used as a device to impose restrictions directed at Aboriginal persons.

(b) This understanding of Maloney is nonetheless unhelpful because the authority of a decision of the High Court is not limited to its ratio decidendi. The aspects of the reasoning noted in the previous paragraph show that the impugned law in Maloney was different to the provisions in question in this case, but they are not inconsistent with the provisions in question in this case also engaging s 10(1). The significance of Maloney for present purposes lies not in what it did or did not decide, but in the “seriously considered dicta” of members of the Court concerning the proper understanding of s 10(1) (see Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 22; 230 CLR 89 at [134] (Farah Constructions)).

36 The following aspects of the reasoning in Maloney bear upon the present question.

37 French CJ noted at [11] that s 10 does not apply only to a law that makes a distinction expressly based on race. He said that it is directed to “the discriminatory operation and effect of the legislation” (footnotes omitted).

38 Hayne J (with whom Crennan J agreed) said, at [67]–[68]:

It will be recalled that the RDA is directed to the prohibition and elimination of racial discrimination. These are very general objects and the relevant provisions of the RDA are expressed in very general terms. Section 10 is especially broad. It is directed to the operation of the laws of the Commonwealth and of the States and Territories. It may be contrasted with s 9(1), which makes it unlawful, but not an offence, for a person “to do any act involving a distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of any human right or fundamental freedom in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life”. Whatever the scope of s 9(1), it is sufficient to notice that it contains elements which s 10(1) does not.

In many, perhaps most, cases it will be accurate to describe a law which is found to engage s 10 as a racially discriminatory law. Given the objects of the RDA, that is unsurprising. Care is needed, however, to ensure that this statement of conclusion is not used in a way that inadvertently narrows or confines the operation of s 10. To do so would be contrary to the large objects which the RDA evidently pursues and the generality of the words which it uses … If the law is not a special measure within the meaning of s 8(1), the conclusion that persons of a particular race enjoy a right to a more limited extent than persons of another race is necessary and sufficient to engage s 10.

(Footnotes omitted.)

39 Bell J referred at [200] to earlier decisions in which it had been noted that s 10 does not refer to discrimination or associated concepts, and that it is directed to “the enjoyment of rights by some but not by others, or to a more limited extent by others”. At [201] her Honour said:

Section 10 implements the obligations assumed under Arts 2(1)(c) and 5 of the Convention. In summary, these are the obligations to nullify laws having the effect of creating or perpetuating racial discrimination and to guarantee equality before the law. Equality before the law is the counterpart of the elimination of racial discrimination. Section 10(1) is to be interpreted in the light of these related purposes. A law creates or perpetuates racial discrimination when it applies any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.

40 At [203]–[204] Bell J dealt with submissions concerning the unintended and anomalous consequences s 10(1) could have if it is understood to apply in cases of unequal enjoyment regardless of whether the law has a legitimate non-discriminatory purpose. The example was given of a planning law requiring buildings in a coastal locality to meet specifications suitable for withstanding extreme weather events. It was suggested that, given a broad reading, s 10 would invalidate that law if the majority of building owners in the relevant location were members of a particular race. Her Honour, having referred to statements in Ward emphasising that s 10(1) is concerned with substance rather than form, suggested that the hypothesised planning law might “not engage s 10(1) because, construed in its context, any limitation on the enjoyment of the right of the building owners would have no connection to race”. No such issue arose in Maloney and it was therefore “not appropriate to determine the extent of the connection with race that is required to validly engage s 10(1)”.

41 Gageler J at [306] described the joint reasons in Ward as having emphasised that:

… s 10 of the RDA is not confined to laws whose purpose can be identified as discriminatory nor to laws that can be said to be aimed at a racial characteristic or to make a distinction based on race and that fulfilment of the condition for the application of s 10 turns rather on the effect of a law on the relative “enjoyment” of a “right” by persons of different races.

(Footnotes omitted.)

42 At [329] his Honour referred to two textual components for the application of s 10. The first was that there exists “a state of affairs in which persons of one race either do not enjoy a human right that is enjoyed by persons of another race or enjoy a human right ‘to a more limited extent’ than persons of another race”. The second was that this was “by reason of” a Commonwealth, State of Territory law. The first component, his Honour said (at [330]), required “no more than that ‘persons’ of one race enjoy a human right ‘to a more limited extent’ than ‘persons’ of another race”.

43 At [331] Gageler J noted that the reference to “persons” in s 10(1) connoted “groups not individuals”. His Honour went on to observe that, nevertheless, it was not necessary for such a group to comprise all members of one or other race. However, the reference to s 10(1)’s concern with groups rather than individuals suggests another point: that questions as to relative “enjoyment” of human rights may in some cases turn on analysis of a group’s circumstances or experience in the realm of the social sciences rather than specific impacts on the enjoyment of rights that can be proved in relation to all members of the group or in relation to the individual applicant.

44 At [333] Gageler J made the following important point:

Persons of one race can enjoy a human right “to a more limited extent” than persons of another race without suffering impairment or infringement of that human right. That proposition can be illustrated by an example adapted from one given by the European Court of Human Rights concerning the requirement of Art 14 of the European Convention that “enjoyment” of the rights and freedoms set forth in that Convention be secured “without discrimination”. A State may well not infringe the human right “to education and training” referred to in Art 5(e)(v) of the Convention by failing to establish a particular kind of educational institution. But if a State establishes an educational institution of a particular kind, the State must ensure that the education the institution provides is available equally to persons of all races. A State law cannot, consistently with s 10 of the RDA, arbitrarily bar the admission of persons of a particular race.

(Footnotes omitted.)

45 His Honour observed at [335] that a difference in the extent of enjoyment of a human right was “a question of degree”, to be answered in the light of the principles and objectives of the Convention.

Construed against the background of those principles and objectives, persons of one race will enjoy a human right “to a more limited extent” than persons of another race where a difference in their relative enjoyment of a human right is of such a degree as to be inconsistent with persons of those two races being afforded equal dignity and respect. The relevant indignity or want of respect lies in the difference in the levels of enjoyment of a human right by persons of the two races rather than in the absolute level of enjoyment by persons of the disadvantaged race. The significance of a difference can be affected by contextual factors, which may include racial targeting or presumptions about the characteristics of racial groups just as they may include ignorance or lack of consideration of the characteristics of racial groups.

46 At [339]–[348] the analysis of Gageler J introduces concepts of proportionality and justification for differential treatment. Some of this reasoning appears to suggest a further condition for the application of s 10(1), namely that the law (so far as it gives rise to different treatment) is not justified by being shown to adopt criteria that are applied in support of a legitimate aim and reasonably necessary to the achievement of that aim (eg at [343]). However, it appears from [347] that this reasoning is looking forward to his Honour’s analysis of special measures under art 1(4) of the Convention and s 8(1) of the RDA.

47 These statements are consistent with the view that s 10(1) is concerned with the practical effect of laws. They are firmly against any limitation on its operation based on whether, in enacting the impugned law, the legislature has set out to make distinctions based on race.

48 That said, it is not clear that the observations of the majority support the position of the applicant in the present case. Care must be taken, of course, because their Honours did not have before them issues of the kind that arise here. For the most part, their observations on s 10(1) are at a fairly high level of generality. The following points suggest that at least some of the majority Justices might not have embraced a submission of the kind being put by the applicant here.

(a) The hypothetical example of a planning law, discussed by Bell J at [203]–[204], is somewhat closer to the present case. In the example, the law would affect only (or predominantly) members of a particular race because of the composition of the class of persons who owned property in the relevant location. As noted above, her Honour suggested (without elaborating) that, in context, the limitation on the enjoyment of rights might not engage s 10(1) on the basis that it “would have no connection to race”. This suggests that s 10(1) is not necessarily engaged by any law that affects the enjoyment of rights by people of different races in different ways.

(b) Gageler J at [335] suggested that not every disparity in the extent of enjoyment of a human right would engage s 10(1). The difference would need to be “of such a degree as to be inconsistent with persons of those two races being accorded equal dignity and respect”, and the significance of the difference could be affected by contextual factors. That suggests that, in the case of a law of the kind presently under discussion (conferring an entitlement on the basis of criteria that pay no regard to race), more would need to be shown than that members of one race are less likely to meet its criteria than members of another race.

2.3.2 Intermediate appellate court decisions

49 The Commonwealth also relied on several decisions of intermediate appellate courts. The applicant submitted that, to the extent that these decisions supported the Commonwealth’s position, they were inconsistent with Maloney and should not be followed.

50 We have come to the view that none of these cases is directly on point, so that no question arises as to whether they should be followed. We therefore do not need to express concluded views as to whether any of these cases was (as the applicant submitted) wrongly decided. However, it is useful to say something about two preliminary matters before discussing the cases: the relationship between intermediate appellate decisions and “seriously considered dicta” of the High Court; and the position of a Full Court of this Court constituted (in the original jurisdiction) to determine separate questions.

51 The view has occasionally been expressed that, as a matter of precedent, a decision by a Full Court exercising the original jurisdiction of the Court carries no more weight than three (or five, as the case may be) single judge decisions to the same effect: see the cases cited in Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs v FAK19 [2021] FCAFC 153; 287 FCR 181 at [31] (Allsop CJ) (FAK19). However, in FAK19 the Chief Justice doubted the correctness of that view, given the text and structure of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) and the importance of Full Court authority in the operation of the system it creates: at [32]. The issue did not need to be decided in FAK19. The point did arise, however, in Pitman v Commissioner of Taxation [2021] FCAFC 230; 289 FCR 287 (Pitman), where the Full Court exercising original jurisdiction (in an “appeal” from the Administrative Appeals Tribunal) was invited to depart from a decision of an earlier Full Court exercising the same jurisdiction. Davies J (at [10]) regarded that step as not open unless the earlier decision was “plainly wrong”, and quoted from other parts of Allsop CJ’s reasons in FAK19. Allsop CJ (at [3]) agreed and said:

… for all the reasons set out in FAK19 at [14]–[29], in particular the reasons directed to the text and structure of the [FCA Act], Full Court decisions in the original jurisdiction (often sat for the purpose of expressing a view on a legal or constructional question) should not be viewed somehow as of lesser authority than Full Court decisions in the appellate jurisdiction.

52 The other member of the Court in Pitman, Bromwich J, regarded the earlier decision as clearly correct, but would otherwise not have departed from it for the reasons given by Allsop CJ and Davies J (at [34]).

53 The issue that now arises is different, but related: should a Full Court exercising the original jurisdiction consider itself bound by a decision of an earlier Full Court exercising appellate jurisdiction, or another intermediate appellate court in the integrated judicial system of Australia?

54 Unlike issues concerning the status to be afforded within the Court to existing judgments of the Court, the question is not solely one of practice (cf FAK19 at [24], [32]). It concerns, in part, consistency of approach as between different courts in the Australian judicial system. That is a topic upon which the High Court has expressed views (in Farah Constructions at [135] and earlier in Australian Securities Commission v Marlborough Gold Mines Ltd [1993] HCA 15; 177 CLR 485, 492). However, the position arrived at by the High Court appears to be that even a single judge is not strictly bound by a decision of an intermediate appellate court in another jurisdiction and may depart from it if persuaded that it is plainly wrong (see CAL No 14 Pty Ltd v Motor Accidents Board [2009] HCA 47; 239 CLR 390 at [49]–[50]). The fact that we are now exercising original rather than appellate jurisdiction may therefore not matter. If that is not correct, and a single judge is constrained in this regard to a greater extent than an appellate court, we would nevertheless conclude that a Full Court of this Court exercising original jurisdiction is in essentially the same position as a Full Court exercising appellate jurisdiction. That conclusion is supported by the consideration that under s 24 of the FCA Act a decision of a single judge can be the subject of an appeal to the Full Court, where existing intermediate appellate authority can be canvassed and departed from if it is plainly wrong, whereas a decision of the Full Court (including one exercising original jurisdiction) cannot: the only avenue of appeal in that case is to the High Court, subject to a grant of special leave. Statements of principle in the cases are to be approached on this basis; and the decisions, if not distinguishable, are to be followed unless plainly wrong.

55 An aspect of the “plainly wrong” question in relation to intermediate appellate decisions is whether they can be reconciled with High Court authority. Another way of putting the point is that, as was noted in Hill v Zuda Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 21; 96 ALJR 540 at [25]–[26], an intermediate appellate court should follow “seriously considered dicta” of the High Court; while a decision of another intermediate appellate court on the interpretation of Commonwealth legislation can properly be departed from if it is considered to be “plainly wrong”. In other words, institutional respect between courts of equivalent status gives way, in the event of conflict, to the authoritative status of seriously considered dicta of the High Court. To the extent that a decision of another intermediate appellate court (or this Court) cannot be reconciled with the view of the majority in Maloney concerning the scope of s 10(1), therefore, that decision must be regarded as wrongly decided and therefore not to be followed.

56 With these principles in mind, we turn to the authorities relied on by the Commonwealth. As noted earlier, we have come to the view that these cases are distinguishable and we therefore do not need to express concluded views as to whether they are to be followed, on the one hand, or “plainly wrong” on the other.

57 In Melkman v Commissioner of Taxation (1988) 20 FCR 331 the appellant sought to claim the benefit of a provision of the tax law which exempted a pension paid by a State of the Federal Republic of Germany by way of compensation to victims of Nazi persecution. The appellant was receiving a pension of that character paid by the Netherlands. His attempt to rely on s 10(1) was found at 336–337 to face at least two problems. One was that the human rights referred to in art 5 that he invoked (those found in paras (d)(iii) and (e)(iv)) were considered not to involve exemption from taxation. Another was that the law did not draw any distinction, express or otherwise, between persons of different races. This second point might now require further scrutiny in light of Maloney, because the German pensions to which the exemption applied were payable (in general at least) only to people of German national origin. By exempting those pensions but not others from tax, the exemption provision arguably granted an exemption that was only available to members of a particular race (although there would be a significant issue as to how the relevant “race” was to be identified, for the purpose of working out who were the persons of “another race” entitled to the same benefit by force of s 10(1)). However, this observation does not cast any doubt on the other significant barrier that the appellant’s argument faced: the need to prove that the particular human rights to which he referred were enjoyed to a lesser extent by members of one or more races, as a result of a small number of members of a particular race having access to a tax exemption.

58 Nguyen v Refugee Review Tribunal (1997) 74 FCR 311 (Nguyen) involved a Vietnamese man whose application to the (then) Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT), for review of a decision by an officer not to grant him refugee status, had been filed outside the applicable limitation period. The RRT had no power to grant an extension of time and concluded that it had no jurisdiction to conduct a review. The appellant argued that, because notice of the primary decision had been sent in English, he was less able to enjoy the right to be notified than a person of another race who could understand English, and s 10(1) therefore applied. So far as can be deduced from the report, his argument seems to have been that s 10(1) gave him an entitlement to be notified in his own language; that had not occurred, and therefore time had not started to run.

59 Tamberlin J held that provision of a notice in the de facto official language of Australia could not be said to be discriminatory in form or effect any more than the printing of legislation and judicial decisions in English was discriminatory (at 319). In the alternative, his Honour reasoned that any lessening of the appellant’s enjoyment of the right to be notified arose from his circumstances (ie that he did not understand English) and not as a result of the terms or effect of the legislation. Sundberg J reasoned at 326–327 that the legislation did not give the members of any race a right to receive notice in their own language. Rather, notification was given in English (which, his Honour found, was implicitly required by the legislation) because that was Australia’s official language. Alternatively, if the argument was that the appellant enjoyed the right to “notification” to a lesser extent than a person who could read English, his Honour regarded that argument as unsound because having the notice brought to one’s attention or understanding it was not a component of the requirement for notice under the Migration Act (at 327). Marshall J (at 331) reasoned along similar lines to Sundberg J.

60 The reasoning of Tamberlin J in Nguyen appears to us to be open to question because of its focus on discrimination (a concept s 10(1) does not employ, at least directly) and the suggestion that any lesser enjoyment of a right was the consequence of the appellant’s circumstances rather than the law. The second aspect is problematic for the reason we have indicated above (at [29]-[31]), and also because the circumstance of the appellant that led to his lesser enjoyment (lack of comprehension of English) was, at least prima facie, related to his race. The same problem arises in the present case, where the reduced life expectancy of Aboriginal men compared to their non-Aboriginal contemporaries is expressly agreed to be a “function” of their race. If lesser enjoyment of a human right by members of the Aboriginal race could be said not to arise “by reason of” the law that gives local expression to that right, on the footing that lesser enjoyment is a consequence of factors arising from their Aboriginality, s 10(1) would be readily circumvented. However, these criticisms do not affect the reasoning of Sundberg and Marshall JJ or the correctness of the actual decision. The practice (widespread if not universal among nation states) of conducting government business in one or two official languages clearly raises special issues, which do not arise in this case. The proper understanding of the relationship between an official language and art 5 of the Convention (and with s 10(1)) may be found in the proper identification of the relevant human right (a point that received little attention in Nguyen) and close attention to what is meant by the enjoyment — and the relative enjoyment — of that human right. Nguyen has not been shown to be wrongly decided, but we do not think it assists greatly in resolving the present case.

61 Sahak concerned applications for judicial review of decisions by the RRT, lodged out of time by applicants who were unable to read and write in English. The focus was s 478 of the Migration Act, which imposed a time limit for an application invoking the statutory review jurisdiction of the Federal Court under s 476. The appellants had both filed review applications outside the permitted period, which the Court had no power to extend. They argued that, as a result of s 478, persons of Syrian and Afghan national origin enjoyed the right to equality before the law, including access to the Court, to a more limited extent than persons of a national origin which had an attribute or characteristic of English as a first language; and that therefore, by force of s 10(1), the time limit did not apply to them. Goldberg and Hely JJ observed at [45] that the discrimination or disadvantage arising from the practical operation of the time limit was not racial discrimination, because a person whose national origin was Afghan or Syrian was able to take advantage of the relevant right to the same extent as anybody else if they had a sufficient understanding of English or if they had access to friends or professional interpreters.

62 Their Honours then said, at [48]:

The fact that an applicant who wishes to review the decision of a Tribunal requires the services of an interpreter in order to prepare and file an application for review does not mean that the right to apply for the review is lessened. Similarly, a person who speaks English but who does not understand how to complete the application due to circumstances, such as physical infirmity, a lack of literacy or a lack of education, does not have his or her right to apply for review lessened by the time limit in s 478 compared to the right of a literate, educated, healthy, English-speaking applicant. Any difficulty such persons confront in completing and filing applications for review within the time limit prescribed by s 478 is due to personal characteristics and not due to a circumstance which is dictated by their race, colour, or national or ethnic origin.

63 Their Honours went on at [49] to conclude that there was no nexus or causal connection between the provisions of s 478 and the manner in which the appellants enjoyed their right of access to the Court as compared with the manner in which English-speaking applicants enjoyed that right. Section 478 operated uniformly and, in their Honours’ view, did not have a differential or discriminatory impact.

64 We have expressed doubts about this last aspect of the reasoning above. Part 8 of the Migration Act, as in force at the relevant time, created a right to seek judicial review of certain migration decisions in the Federal Court in addition to the constitutionally entrenched jurisdiction of the High Court under s 75 of the Constitution. Part of the manner in which that right was conferred was that it could only be exercised by making an application within a strict time limit. To the extent that the right was enjoyed to a lesser extent by members of one race compared to members of another, and that lesser enjoyment arose from the more onerous application of the time limit upon people whose first language was not English, it is hard to see how that lesser enjoyment did not have a nexus or causal connection with the provisions of s 478.

65 However, the result in Sahak can be explained on the basis of what their Honours said at [48], which echoes the reasoning in Nguyen. It can also (and perhaps more persuasively) be explained on the alternative basis set out in the reasons of North J (at [3]–[4]). If the relevant human right is understood as the right to seek judicial review of an adverse decision, and regard is had to the jurisdiction of the High Court under s 75(v) of the Constitution (which, unlike the jurisdiction of the Federal Court under Pt 8 of the Migration Act, was not limited to specified grounds), it could not be said that the right was not enjoyed or enjoyed to a lesser extent by the appellants than by other persons.

66 Jones v Public Trustee of Qld [2004] QCA 269; 209 ALR 106 (Jones) concerned provisions in the Succession Act 1981 (Qld) (Succession Act) specifying the persons who could pursue proceedings in the Supreme Court concerning an estate that had been administered on intestacy. The appellant claimed the right to pursue such proceedings on the basis that he was the most senior elder of the Dalungdalee people, to which the deceased had belonged. That was not a sufficient interest under the provisions of the Succession Act. It was argued that the relevant provisions were inconsistent with s 10(1), on the basis that they conflicted with Aboriginal traditional or customary law. However, McPherson JA (with whom Williams and Jerrard JJA agreed) held that the content of any such traditional rights had not been proved. His Honour also observed (at [19]) that the provisions of the Succession Act made no distinction between peoples of any race or origin and applied equally to all people including Aboriginal people. In the light of Maloney, the latter proposition might well not be sufficient to dispose of the case. However, it may be doubted whether “the right to inherit” (referred to in art 5(d) of the Convention) is enjoyed to a lesser extent by the people of any race in a situation where the same rules apply in relation to any person who dies intestate. The case is, rather, one where the State has chosen to apply the same rules to everyone rather than create different intestacy regimes for people of different racial or cultural backgrounds. In the end, we do not think Jones assists in the resolution of the present issues.

67 In Vanstone v Clark [2005] FCAFC 189; 147 FCR 299 (Vanstone), the respondent was the Chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). He sought judicial review of a decision by the appellant (as the responsible Minister) to suspend him from office under a provision of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989 (Cth) (ATSIC Act). The decision depended on a determination made (purportedly) under another section of the ATSIC Act, providing that conviction for certain offences was to be taken to constitute “misbehaviour” for the purposes of that Act. At first instance, the determination (and thus the decision) was held invalid on several grounds, one of which was that its effect was to hold office-holders of ATSIC to a higher standard than holders of comparable offices under other legislation. Section 10 was said to require the determination to be read down to overcome that effect (Clark v Vanstone [2004] FCA 1105; 211 ALR 412 at [109]–[115]). In the Full Court, the other statutory offices referred to by the primary judge were regarded as not comparable (Vanstone at [201] (Weinberg J (Black CJ agreeing))), and the determination did not operate in a discriminatory way between Indigenous and non-Indigenous holders of offices under the ATSIC Act (at [200]). There was thus no inconsistency of treatment based upon race.

68 Queensland Construction Materials Pty Ltd v Redland City Council [2010] QCA 182; 271 ALR 624 (Queensland Construction Materials) concerned a provision in Queensland planning law entitling the owners of neighbouring properties to be given notice of, and object to, a proposed development. “Owner” was relevantly defined to include a person entitled to receive rent from the property (or who would be so entitled if the property were leased). Parties who claimed to hold native title in certain land contended that, by virtue of s 10(1), they were entitled to be given notice. Chesterman JA and Applegarth J held that, even if native title was established, s 10(1) would not operate so as to put the claimants in the same position as holders of other interests in land. Their Honours held that the distinction made by the relevant provisions was based not on race but upon different proprietary interests in land. If the claimants were able to establish a right to exclusive possession and a right to receive rent for the land, they would relevantly be “owners”; otherwise, along with holders of various kinds of non-native title rights other than freehold and leasehold, they would not be.

69 An application for special leave to appeal to the High Court in Queensland Construction Materials was refused on the papers: [2011] HCASL 131. It is not clear whether the issue referred to in the previous paragraph was raised in the application.

70 In R v Woods [2010] NTSC 69; 246 FLR 4 (Woods), the defendants were two Aboriginal men charged with murder. They challenged the array of jurors on several bases, including that provisions in the Northern Territory legislation excluded persons who had been in custody in the previous seven years from jury service and required the service of summons by ordinary post. These provisions were said to result in a disproportionately low number of Aboriginal people on jury panels, because of their over-representation in the prison population and because many had no postal address. This, it was argued, engaged s 10(1) because the defendants, compared to non-Aboriginal persons, had less chance of being tried by a jury including people of the same race as them. The argument was rejected by the Full Court, holding that the right to trial by jury did not include any requirement as to the racial mix of the jury panel. Rather, in their Honours’ view, random selection of jury members was an important element of trial by jury (at [58]). The Court went on to say, at [59]:

To impose some overriding requirement to the effect that a jury, once randomly selected in this way, has to be racially balanced or proportionate would be the antithesis of an impartially selected jury, not to mention the enormous practical difficulties that would be associated with attempting to meet such a requirement, particularly as it is not an easy matter to identify who is, or is not, a member of a particular racial group.

71 Factually, Woods is close to the present case. The impugned law was part of the statutory regime giving effect under municipal law to one of the fundamental human rights whose equal enjoyment is mandated by the Convention. Its facially neutral criteria were said to operate differently as between Aboriginal people and others, because of social facts concerning the life experiences of Aboriginal people that resulted in different probabilities as to how relevant rights would be enjoyed. The resolution of the case lay in analysing the relevant human right and what was involved in its equal or unequal enjoyment. In our view, the reasoning in Woods is not overtaken by anything that was said in Maloney.

72 Aurukun is a case that might well be approached differently following Maloney, although that does not mean it was wrongly decided. It concerned amendments to the Liquor Act 1992 (Qld) (Liquor Act) which provided that a local government entity could no longer hold a liquor licence. The only local government entities that held liquor licences were Indigenous local governments.

73 Keane JA held that s 10(1) was not engaged on the basis that neither the right to use a local government facility to purchase alcohol nor the right to use a local supplier was a human right or fundamental freedom of the kind with which s 10 was concerned (at [155]); the provisions were not in breach of s 10 because they served a legitimate and non-discriminatory goal (protecting women and children in Indigenous communities from domestic violence) (at [166]–[170]); and the law did not result in a different level of enjoyment of the right to have access to a local supplier of alcohol (the practical effect of the law being that nobody in Queensland could acquire alcohol from their local government) (at [178]–[179]). Alternatively, his Honour would have held that the law was a special measure within s 8 of the RDA. Philippides J held, as to the rights of individuals, that the provisions were not inconsistent with equal treatment before the law because they applied everywhere in Queensland (at [262]) and other means of obtaining alcohol were not precluded (at [275]–[276]); and that, so far as there was interference with the property rights of the local councils, those rights were not absolute and could be modified to achieve a legitimate and non-discriminatory public purpose (at [266]–[271]). McMurdo P held that s 10(1) was engaged, but that the provisions were a special measure.

74 An application for special leave to appeal from the decision in Aurukun was dismissed on the basis that an appeal would have insufficient prospects of success. Refusal of special leave has no status as precedent (North Ganalanja Aboriginal Corporation v Queensland [1996] HCA 2; 185 CLR 595, 643 (McHugh J)), although in some circumstances the reasons given can be persuasive (Algama v Minister for Immigration [2001] FCA 1884; 115 FCR 253 at [62] (Whitlam and Katz JJ, French J agreeing)). The short oral reasons delivered by Hayne J indicate that the High Court was not persuaded that the applicants had significant prospects of identifying a fundamental right or freedom that was infringed (Transcript of Proceedings, Aurukun Shire Council v CEO, Liquor Gaming & Racing in Dept of Treasury [2010] HCATrans 293), and therefore do not involve any endorsement of the reasoning in the Court of Appeal concerning the practical effect of the provisions. (The provisions considered in Aurukun, while they amended the Liquor Act, were part of an Act called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities (Justice Land, and Other Matters) and Other Acts Amendment Act 2008 (Qld) which was plainly directed at Indigenous communities. There is every reason to think that, if these provisions had affected the enjoyment of a fundamental human right of the kind referred to in art 5 of the Convention, the Court as constituted in Maloney would have regarded them as engaging s 10(1); although the provisions might well also have been regarded as a special measure.)

75 Munkara is the first of the intermediate appellate decisions to which we were referred that post-dates Maloney. Section 6 of the Alcohol Protection Orders Act 2013 (NT) (APO Act) provided police with powers to issue alcohol protection orders. These orders could be issued if a person was charged with a “qualifying offence” and the issuing officer believed that the person was affected by alcohol at the time. The effect of an order was to prohibit the person from possessing or consuming alcohol or (with certain exceptions) being on licensed premises. Evidence showed that Aboriginal people were vastly more likely to be issued with alcohol protection orders than other people in the Territory. The appellant argued that s 6 engaged s 10(1) of the RDA and was therefore invalid. He also argued that the provisions for seeking reconsideration of an order engaged s 10(1) because the very short time limits in ss 9 and 11, together with other formalities, created particular difficulties for Aboriginal people given their low levels of literacy in English. The time limits were said to be of no effect for this reason. Although the statute was racially neutral in its terms, the appellant argued (relying on Maloney) that its “legal and practical operation” was to disadvantage Aboriginal people in their enjoyment of the right to own property (ie alcohol) and their right of access to licensed premises (including hotels, restaurants, cafes and some supermarkets).

76 The reasoning of the Court of Appeal on the s 10 issues is to be found in the reasons of Blokland J. Kelly J agreed with that reasoning (at [15]) and Barr J agreed with Kelly J on all of the issues in the appeal.

77 In relation to s 6, Blokland J said at [99]:

The primary judge was correct in holding that any adverse effect suffered by Aboriginal persons as a result of the imposition of an alcohol protection order is not as a result of the law itself but as a result of the person committing a qualifying offence whilst affected by alcohol. The situation is clearly distinguishable from the circumstances considered in Maloney because in that case, the Queensland legislative and regulatory scheme was directed at the largely Aboriginal population of one community, Palm Island, the residents of which were almost all Indigenous persons. They suffered disadvantage without any wrongdoing or qualifying conduct on their part. Under the Act the subject of this appeal, the law does not have effect unless and until a person commits a qualifying offence and a police officer reasonably believes that a person was affected by alcohol at the time of offending. Criminal offending in circumstances where the offender is affected by alcohol triggers the operation of the Act.

78 Her Honour’s response to the argument that alcohol consumption (and therefore exposure to orders under the APO Act) was causally related to race was as follows (at [102]):

That contention is rejected. It adds nothing to the bare statement of the statistics, i.e. that Aboriginal people form about 27 percent of the population and have received over 90 percent of the alcohol protection orders. It could also be said that “serious domestic violence and race are interrelated concepts when it comes to Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory” because the statistics are much the same. Put that way, the concept is simplistic and offensive. The appellant’s submission ignores the reality of deprivation and disadvantage that are the real matters referred to by the High Court in [Bugmy v The Queen [2013] HCA 37; 249 CLR 571] and are well acknowledged to be important factors associated with criminal behaviour and alcohol and substance abuse. Further, it ignores the fact that most Aboriginal people do not abuse alcohol and that many non-Aboriginal people do.

79 However, what her Honour described as the “main point” (at [103]–[104]) was that, unlike the law considered in Maloney, the APO Act did not deprive anyone of the right to possess alcohol or enter licensed premises. Instead, its effect was “to place consequences on people’s behaviour, namely in the first instance committing a qualifying offence while affected by alcohol”. If s 10(1) was engaged because members of a particular race were disproportionately likely to engage in the relevant behaviour, the same would be true of any offence-creating provision in the Criminal Code where members of a particular race are more likely than other people to be imprisoned (and thereby deprived of liberty) for committing the relevant offence.

80 As to the challenge to the time limits on reconsideration requests, Blokland J held that the reasoning in Sahak was not contrary to established authority concerning s 10(1) (including Maloney) (at [118]) and not clearly wrong (at [119]).