Federal Court of Australia

Target Australia Pty Ltd v Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association [2023] FCAFC 66

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | SHOP, DISTRIBUTIVE AND ALLIED EMPLOYEES' ASSOCIATION Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | SHOP, DISTRIBUTIVE AND ALLIED EMPLOYEES' ASSOCIATION Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The cross-appeal be dismissed.

3. There be no order as to costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMBERG J:

1 This is an appeal from two judgments of a judge of this Court (primary judge) published as Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Target Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1038 (First Judgment) and Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Target Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 1422 (Second Judgment). Both the Appellant’s (Target) appeal and the Respondent/Cross-Appellant’s (SDA) cross-appeal concern the meaning of the phrase “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 of the Target Australia Retail Agreement 2012 (2012 Agreement), which at all relevant times provided that (emphasis added):

A team member going on Annual Leave shall be paid in addition to their ordinary time earnings for the period of leave a loading of 17.5% prior to the commencement of such leave.

2 The question in the appeal is whether the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is an intended reference to what the employee (ie the “team member going on Annual leave”) would have earned if the employee had not taken leave, calculated as if only the “ordinary hourly rate” prescribed by the 2012 Agreement applied (Target’s construction) or, instead, is an intended reference to the entirety of what would have been earned by the employee for working their ordinary hours of work (SDA’s construction).

3 The cross-appeal raises whether the word “earnings” in the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is an intended reference to the remuneration of the employee payable under the 2012 Agreement (Target’s construction) or, instead, a reference to all remuneration earned by the employee in the period in question, irrespective of its source and including ‘over-award’ earnings payable under the employee’s contract of employment (SDA’s construction).

THE APPEAL

4 By orders made on 16 November 2021, the primary judge made the following declaration:

1. For an employee going on annual leave, ‘ordinary time earnings’ in cl 7.2.10 of the Target Australia Retail Agreement 2012 (Agreement) includes:

(a) payment for ordinary hours worked in accordance with the classification rates under cl 5.1 of the Agreement; and

(b) payment of any applicable penalties in accordance with cl 6.1.3 of the Agreement.

2. For an employee going on annual leave, ‘ordinary time earnings’ in cl 7.2.10 of the Agreement does not include:

(a) any allowances payable pursuant to cl 5.2 of the Agreement; and

(b) any entitlements payable by reason of additional hours worked by way of overtime in accordance with cl 6.5 or in accordance with cl 4.2.4 of the Agreement.

5 By its Notice of Appeal, Target contended that the primary judge erred by concluding that the phrase “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 of the 2012 Agreement includes payment of any applicable penalties in accordance with cl 6.1.3. Target contended that the primary judge should have concluded that the phrase “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 is confined to payment for ordinary hours worked in accordance with the classification rates under cl 5.1 of the 2012 Agreement. Target seeks that the orders made by the primary judge be set aside and, in lieu thereof, that the Court declare that:

a. for an employee going on annual leave, “ordinary time earnings” in clause 7.2.10 of the Agreement includes payment for ordinary hours worked in accordance with the classification rates under cl 5.1 of the Agreement.

b. for an employee going on annual leave, “ordinary time earnings” in clause 7.2.10 of the Agreement does not include:

i. payment of any applicable penalties in accordance with cl 6.1.3 of the Agreement;

ii. any allowances payable pursuant to cl 5.2 of the Agreement; and

iii. any entitlements payable by reason of additional hours worked by way of overtime in accordance with cl 6.5 or in accordance with cl 4.2.4 of the Agreement.

6 The declaration made by the primary judge in paragraph 2(a) of the orders made on 16 November 2021 dealing with allowances is not in dispute. The remainder of the declarations made are in dispute and are essentially based upon the primary judge’s acceptance of what I have called the SDA’s construction of the phrase “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 of the 2012 Agreement.

7 For the reasons that follow, I agree with the SDA’s construction and reject Target’s construction of that phrase.

Applicable principles for construing enterprise agreements

8 The applicable principles for construing an enterprise agreement were largely not in dispute. The relevant principles were set out by the Full Court in WorkPac Pty Ltd v Skene (2018) 264 FCR 536 at [197] (Tracey, Bromberg and Rangiah JJ) as follows:

The starting point for interpretation of an enterprise agreement is the ordinary meaning of the words, read as a whole and in context: City of Wanneroo v Holmes (1989) 30 IR 362 (Holmes) at 378 (French J). The interpretation “turns on the language of the particular agreement, understood in the light of its industrial context and purpose”: Amcor Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2005) 222 CLR 241 (Amcor) at [2] (Gleeson CJ and McHugh J). The words are not to be interpreted in a vacuum divorced from industrial realities (Holmes at 378); rather, industrial agreements are made for various industries in the light of the customs and working conditions of each, and they are frequently couched in terms intelligible to the parties but without the careful attention to form and draftsmanship that one expects to find in an Act of Parliament (Holmes at 378-379, citing George A Bond & Company Ltd (in liq) v McKenzie [1929] AR (NSW) 498 at 503 (Street J)). To similar effect, it has been said that the framers of such documents were likely of a “practical bent of mind” and may well have been more concerned with expressing an intention in a way likely to be understood in the relevant industry rather than with legal niceties and jargon, so that a purposive approach to interpretation is appropriate and a narrow or pedantic approach is misplaced: see Kucks v CSR Ltd (1996) 66 IR 182 at 184 (Madgwick J); Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Woolworths SA Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 67 at [16 (Marshall, Tracey and Flick JJ); Amcor at [96] (Kirby J).

9 These principles have been cited with approval by the Full Court of this Court on numerous occasions: see Qube Logistics (Rail) Pty Ltd v Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union (2021) 308 IR 39 at [32] (Bromberg, Katzmann and O’Callaghan JJ); King v Melbourne Vicentre Swimming Club Inc (2021) 308 IR 171 at [42] (Collier, Katzmann and Jackson JJ); Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Hay Point Services Pty Ltd (2018) 363 ALR 101 at [8] (Reeves, Bromberg and O’Callaghan JJ). There are other contextual considerations that should be borne in mind when the meaning of an enterprise agreement is being considered which are discussed at [54]-[56].

Common uses of the expressions “ordinary time”, “ordinary hours” and “ordinary rate” in industrial agreements

10 The critical constructional question is what kind of “earnings” are intended to be captured by the phrase “ordinary time earnings”. The adjectival phrase “ordinary time”, or its equivalent “ordinary hours”, is a term often used in industrial instruments in a manner consistent with the SDA’s construction to reflect what Allsop CJ in Bluescope Steel (AIS) Pty Ltd v Australian Workers’ Union (2019) 270 FCR 359 at [38] said was the “long-recognised distinction between ordinary hours of work and overtime”. His Honour (with whom Rangiah J agreed at [357]) relevantly said this:

The context is the payment of salaries and wages in the workplace. In that context, the word “ordinary” and the phrase “ordinary hours” have assumed different meanings depending on context and circumstance. There are circumstances and contexts where the word and phrase can be seen to refer to regular, normal, customary or usual hours; and there are circumstances or contexts where the word and phrase can be seen to refer to the hours of work referred to in applicable industrial instruments as standard hours to be paid at ordinary rates, as opposed to additional hours (even if required, usual, regular, normal or customary) and paid at a special or higher rate. As such, the word and phrase can be seen to reflect the long-recognised distinction between ordinary hours of work and overtime: cf Thompson v Roche Bros Pty Ltd [2004] WASCA 110 at [31].

11 As that passage acknowledges, the meaning of the word “ordinary” when qualifying the word “hours” (or “time”) will usually depend on the context in which it has been used. “Ordinary hours” can be a reference to the hours of work of a particular employee, which are either contracted for, or prescribed by, the applicable award or industrial instrument. Thus, for full-time employees, an award may provide for the working of a 40-hour week in exchange for the weekly rate of pay. In that context, it would be appropriate to refer to the prescribed hours as the “ordinary hours”. Similarly, a part-time employee may be contracted to work 15 hours per week. Again, it would be appropriate to refer to the hours set by the contract as the employee’s ordinary hours of work. The expression “ordinary hours” is used in that way, for instance, in s 20 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act). That use of the expression is also consistent with the way it is used in relation to the National Employment Standards (NES) provided for by Pt 2-2 of the FW Act, as was explained in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008 (Cth): see the discussion by Bromberg J in Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Qantas Airways Ltd (2020) 282 FCR 130 at [163]-[165].

12 Reflecting on what Allsop CJ in Bluescope Steel referred to as the “long-recognised distinction between ordinary hours of work and overtime”, when the expression “ordinary hours” or “ordinary time” is used to refer to the hours of an employee, the reference will usually be an intended reference to the standard hours of work of the employee prescribed by the industrial instrument or the contract, as distinct from the extra hours that an employee may either be required to work or may volunteer to work as overtime.

13 Where an employee regularly works additional regular hours, beyond what I have referred to as the prescribed ordinary hours, the total hours worked may, in some contexts, also be referred to as the usual or ordinary hours of the employee. It is primarily for that reason that sometimes ambiguity arises as to what is meant by the phrase “ordinary hours” of the employee.

14 Another way in which the phrase “ordinary hours” or “ordinary time” can be used is to refer to the ordinary hours of the workplace. In many, perhaps most, workplaces, the ordinary hours of the employees of a workplace will reflect the ordinary hours of the workplace. Thus, in a workplace where the ordinary hours of each of the employees are 9.00 am to 5.00 pm Monday to Friday, it would be appropriate to refer to the ordinary hours of the workplace as 9.00 am to 5.00 pm on weekdays. However, awards and industrial instruments will commonly provide for the ordinary (ie non-overtime) hours of an employee to be worked within a span of hours. Thus, an employee’s ordinary Monday to Friday eight-hour work day may be rostered within a span of hours of, say, 7.00 am to 6.00 pm Mondays to Fridays. It is common (though not always the case) for an employee’s ordinary hours of work, which are worked within the span of hours set for the workplace, to be paid for at the employee’s ordinary rate of pay, rather than at a penalty rate paid in recognition of the unsociable nature of the hours in which the work is performed. In a context like that, the span of hours set by the industrial instrument can be appropriately referred to as “ordinary hours”, meaning the ordinary or standard hours of the workplace in which the ordinary hours of its employees will commonly be worked.

15 As just alluded to, the word “ordinary” can be, and often is, used in industrial instruments in association with rates of pay to describe what is also called the “base” rate of pay payable to the employee for working ordinary hours. In that context, the “ordinary” or “base” rate will usually be a rate of pay free of any penalty rate or monetary allowance.

16 Those observations made by reference to common experience are not controversial. They are intended to do no more than broadly identify the particular industrial contexts in which it would be generally appropriate to use the expressions “ordinary hours” or “ordinary time” and “ordinary rate” or “base rate” to communicate an intended meaning.

The construction of “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10

The natural and ordinary meaning of “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10

17 To my understanding, it is not controversial that if the words “ordinary time” in the expression “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 are directed purely to describing the nature of the time or hours of work, they are an intended reference to the ordinary hours or ordinary time of the employee rather than the ordinary hours or ordinary time of the workplace. That is because the context of cl 7.2.10 very strongly suggests that the expression is addressed to the ordinary hours of the employee. The clause is focused upon the employee’s circumstances. It is dealing with a payment to be made to the employee, referrable to what the employee would have earned in the period of the employee’s absence on annual leave, in circumstances where the amount that the employee would have earned if the employee was not absent on leave cannot be ascertained without reference to the employee’s hours of work. Further, cl 7.2.2, dealing with an employee’s entitlement to paid annual leave, states that the entitlement accrues “according to the team member’s ordinary hours of work”. Further still, where the 2012 Agreement seeks to refer to the ordinary hours of the workplace, it does so using the phrase “span of ordinary hours” (see cl 1.7.12 and cl 4.2.4).

18 On the basis that the expression has been used to refer to the hours of the employee and, in the context provided by cl 7.2.10, I would regard the phrase “ordinary time earnings” as communicating that the employee be paid the earnings which would have been earned for working the ordinary hours of the employee (as opposed to the ordinary hours of the workplace) that the employee would have worked if the employee had not been absent on annual leave. On that view, the word “ordinary” is identifying which category of time or working hours is being referred to. The word “ordinary” connotes normal hours but, nuanced by its customary industrial usage, it does not mean the usual hours worked by an employee. Rather, it means the standard hours worked by the employee as distinct from the additional hours worked, in other words, the non-overtime hours of an employee. That view and that construction of the phrase is consistent with the SDA’s construction.

19 On the appeal, Target contended that the words “ordinary time” in the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is an intended reference to the earnings generated by those hours worked that only attract the “ordinary hourly rate of pay” payable under the 2012 Agreement and not those hours which attract a penalty rate of any kind. The term “ordinary hourly rate of pay” is given its content by cl 5.1.6(6) of the 2012 Agreement which, when read in context, provides that the “ordinary hourly rate of pay” is to be calculated by dividing the weekly rate appropriate for a full-time employee by 38 being, as I shall explain, the ordinary (ie non-overtime) number of hours for a full-time employee prescribed by the Agreement.

20 By its oral reply, Target essentially resiled from that formulation of its construction, implicitly recognising that it could not be correct because, so formulated, the construction would lead to absurd results. It is clear that “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 could not have been intended to mean the earnings for the hours that would have been worked by the employee which do not attract any penalty rate. The absurdity that would result is that an employee whose rostered hours fell entirely within “Span 2” hours (a term I later explain) would receive no annual leave payment at all because each of those hours “attract” a penalty rate, namely, the rate specified in cl 6.1.3.

21 By its oral reply, Target sought to adjust the formulation for which it contended. It contended that the “ordinary time earnings” of an employee captured by cl 7.2.10 are any earnings from the working of the employee’s ordinary time in “Span 1” hours (again, a term I later explain) as well as the earnings from the working of ordinary hours in Span 2 hours, but excluding any penalty payable in respect of the ordinary hours worked in Span 2. On that view, and consistently with the thrust of the submission initially put, Target contends that “ordinary time earnings” means the ordinary or base rate earnings (as distinct from penalty rate earnings) that would have been earned by the employee working the employee’s ordinary hours. Or, in other words, the earnings that would have been earned by the employee working his or her ordinary hours but excluding any penalty earnings.

22 There are a number of problems with that construction. The first is that it is not supported by the text of cl 7.2.10 and in particular the phrase “ordinary time earnings”. The construction is based upon paid annual leave comprising only those earnings which are paid at the employee’s ordinary rate of pay. If that were the intent of cl 7.2.10, the description of what is to be paid would have been more naturally expressed as “ordinary rate earnings” and not “ordinary time earnings” or, alternatively, as “ordinary time earnings excluding penalties” which, as I later explain, is the formulation adopted by other clauses in the 2012 Agreement.

23 In essence, Target’s construction alters the adjectival phrase which qualifies the word “earnings” from “ordinary time” to “ordinary rate”.

24 To justify its construction, Target relied on the observations made in Scott v Sun Alliance Australia Limited (1993) 178 CLR 1 at 5 where Mason CJ, Brennan, Dawson, Toohey and McHugh JJ said:

The expression “ordinary time rate of pay” is well known in the industrial relations field in Australia and New Zealand. It and similar terms have long been used in legislation. Unless the context otherwise requires, “ordinary time rate of pay” means the rate of pay for the standard or ordinary hours of work in contrast to the overtime or penalty rate of pay for hours of work other than the standard or ordinary hours.

25 At 7-8 their Honours continued:

In some contexts, “ordinary time” may mean “regular, normal, customary, usual” time. Thus in Kezich v Leighton Contractors Pty Ltd, this Court held that the words “the ordinary hours he would have worked, if he were not incapacitated for work as a result of the injury” in cl. 2 of the Schedule to the Workers' Compensation Act 1912 (W.A.) referred to the hours during which it was usual for the employee to work. In that case, Gibbs J. considered that it was not legitimate to construe the statute by reference to the meaning which the words bore in industrial awards and agreements. However, in this case, unlike Kezich the relevant expression “ordinary time rate of pay” has an established and special meaning in the context of employment and industrial relations. Accordingly, it is that meaning which the words must bear in s 69(1)(a) in their application to employment governed by an industrial award or agreement. In such an award or agreement, the expression “ordinary time” cannot mean the customary or usual hours of work.

26 Target also relied on Kucks v CSR Ltd (1996) 66 IR 182, where Madgwick J also considered the phrase “ordinary time rate of pay”. His Honour said at 185:

The genesis of the main argument for the applicant is that, prima facie, “ordinary” means “usual”, and usually Mr Kucks’ rate of pay included his shift allowance. However terms like “ordinary rate of pay” and “standard hours” have well-known meanings in the sphere of industrial relations in this country, as is shown by what was said, admittedly in a different context, in Scott v Sun Alliance Australia Ltd (1993) 178 CLR 1.

27 Target accepted that those authorities considered the phrase “ordinary time rate of pay” as opposed to “ordinary time earnings”. However, it submitted that their focus on the meaning to be given to the words “ordinary time” — namely “the standard or ordinary hours of work” in contrast to hours that, whilst “usually” worked, attract overtime or penalty rates — is consistent with the construction for which Target contends.

28 What was in essence being contended by Target was that the word “ordinary” or the phrase “ordinary time” carried a customary association with the base (non-penalty) rate of pay of an employee. On that basis, Target contended that the word “ordinary” or the words “ordinary time”, when used in the phrase “ordinary time earnings”, are to be understood in the same way as the word “ordinary” is used in the expression “ordinary hourly rate of pay” in cl 5.1.6(6) of the 2012 Agreement. That is, as a reference to “base” rather than a reference to “normal” or “usual”. As I understand it, what was essentially being contended is that the use of the word “ordinary” in both the expression “ordinary time earnings” and “ordinary hourly rate of pay” suggests their equivalence of meaning because of the historical industrial association of “ordinary” with “base” and because it would be strange if the parties to the 2012 Agreement “intended that ‘ordinary’ means ‘standard’ or ‘base’ for the purposes of the definition of ‘ordinary hourly rate of pay’ and ‘normal’ or ‘usual’ for the purposes of determining ‘ordinary time earnings’”.

29 Target’s submission is unpersuasive. I accept that the word “ordinary” or the phrase “ordinary time”, when used in association with “rate of pay”, can have a particular meaning in a particular industrial context so that “ordinary” does not connote “usual”. However, that does not support the proposition that when, in a different industrial context, “ordinary” is used in association with “earnings”, the word “ordinary” connotes “base” so as to result in the words “ordinary time earnings” communicating “base rate earnings”.

30 The natural meaning of “ordinary time earnings”, in relation to a period of work provided by an employee in exchange for remuneration, is the total remuneration earned by the employee when working ordinary time. In that expression, the work of the words “ordinary time” is not to identify a particular rate of pay but simply to identify the particular work — ie ordinary hours of work or ordinary time work — in order that the phrase “ordinary time earnings” captures whatever remuneration is paid in exchange for the performance of that work. That natural meaning is not displaced by reference to the fact that, generally, the expression “ordinary time rate of pay” does not mean an employee’s “usual” rate of pay. Nor is it displaced by the fact that it is generally the case that, where “ordinary” is associated with “rate of pay”, the composite expression is commonly intended to mean an employee’s base rate of pay.

31 Nor would it be strange, if the natural meaning of “ordinary time earnings” is the correct meaning, for the 2012 Agreement to have used the word “ordinary” in the expression “ordinary hourly rate of pay” in cl 5.1.6(6) and then used the word “ordinary” in the expression “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10. The word ordinary is but an adjective. It may take its colour from the context of its use. However, that does not mean that it would be inconsistent to use the adjective for a second time, but in a different context, where it can take on a different colour.

32 It is, I think, notable that where the 2012 Agreement sought to provide paid leave, but confine it to ordinary rate earnings, it has done so expressly and in different language to that employed by cl 7.2.10. It is also notable that, where the Agreement appears to intend to refer to an employee’s base rate of pay and uses the word “ordinary” to do so, it does so by using the word “ordinary” as an adjective which describes the noun “rate”.

33 Thus, in relation to personal/carer’s leave, cl 7.3.6 provides that paid personal/carer’s leave “will be at the team member’s ordinary time earnings for the hours normally rostered to work, excluding any penalties” (emphasis added). The same formulation is again used in cl 7.3.11 dealing with paid carer’s leave and cl 7.6.8 dealing with paid compassionate leave. A further example is to be found in cl 7.11 dealing with natural disaster leave where “up to 3 days’ paid leave per year … [is] paid at the ordinary time earnings rate” (emphasis added).

34 In contrast, the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is used elsewhere in relation to paid leave in a manner consistent with the SDA’s construction of that phrase. Thus, cl 7.9.2 dealing with Defence Force Services Leave provides:

During such leave, team members who are required to attend full-time training shall be paid an amount equal to the difference between the payment received in respect of their attendance at camp and the amount of ordinary time earnings they would have received for working ordinary time during that period. (Emphasis added)

35 Looking then beyond clauses that deal with paid leave, there are numerous examples of the 2012 Agreement using the word “ordinary” in association with the word “rate” in expressions like “ordinary time rate” or “ordinary hourly rate” or “ordinary hourly rate of pay” or similar where the Agreement seeks to specify that a payment is to be confined to, or a penalty or other rate is to be calculated by reference only to, the base rate of pay of the employee (see cll 4.2.8, 4.3.7, 4.7.4, 4.7.10(a), 5.1.6(6), 6.1.2, 6.1.3, 6.1.4 and 7.13.18(b)).

36 I also note that the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is used by cl 5.4.2 dealing with superannuation (later reproduced at [89]). The phrase is there defined.

37 Although not necessary to the primary judge’s acceptance of the SDA’s construction of the phrase “ordinary time earnings”, the primary judge regarded the definition of the phrase in cl 5.4.2 as not necessarily confined in its application to that clause but nonetheless found that the definition cannot be simply “adopted and transposed” to cl 7.2.10: Second Judgment at [14]. I agree that the definition of “ordinary time earnings” provided in cl 5.4.2 is not applicable to cl 7.2.10. As I explain in more detail below at [86]-[99], the location of the definition, among other reasons, strongly suggests an intent that it be confined to the clause in which it appears. However, accepting its confined application and recognising that a defined meaning may not necessarily be intended to reflect the ordinary meaning of a word or phrase, the definition of “ordinary time earnings” provided in cl 5.4.2 is of some relevance in that it is largely consistent with the SDA’s construction of what “ordinary time earnings” means. I would, however, regard its relevance as marginal and unnecessary for reaching the ultimate conclusions that I have.

Contextual indicators that support the SDA’s construction

38 There are further informative contextual considerations provided by other clauses of the 2012 Agreement and the structure of that Agreement. It is not, however, necessary or convenient to set out here the text of all of those clauses. The primary judge in her reasons at [26]-[55] either sets out the terms of those clauses that may be thought to be of any relevance or provides a sufficient outline of them.

39 It is convenient, however, to set out the terms of cl 6.1 dealing with “Hours of Work”:

6.1 Hours of Work

6.1.1 Subject to the savings provisions contained within this Agreement, team members may be rostered to work on any day of the week, at any time.

6.1.2 A team member shall be paid the ordinary hourly rate for work rostered between the span of hours listed below:

Day Time of Starting Time of Finishing

Monday to Friday 5.00 a.m midnight

Saturday 5.00 a.m 8.00 p.m

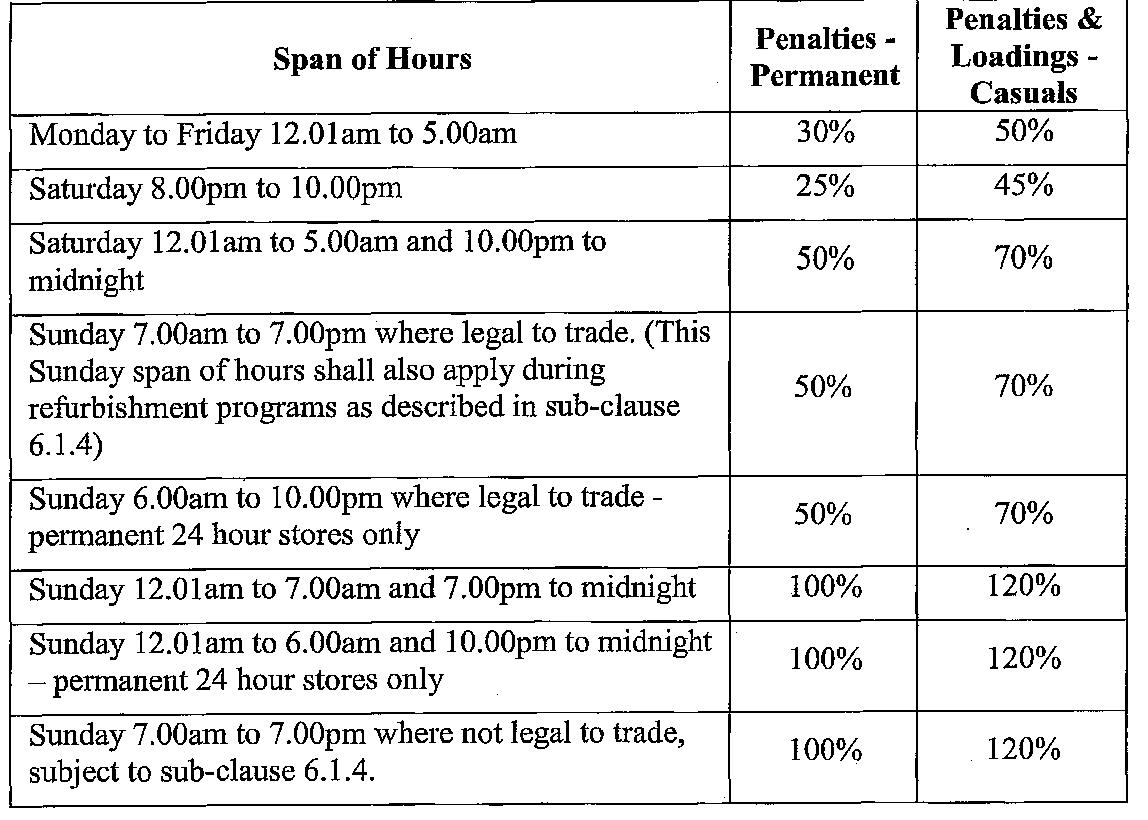

6.1.3 Work rostered outside the span of hours listed in sub-clause 6.1.2, shall be paid the penalties set out in this sub-clause, in addition to the team member’s ordinary hourly rate of pay.

6.1.4 In stores where it is not legal to trade on a Sunday, a team member may be rostered as part of their ordinary hours between 7.00am to 7.00pm on a Sunday during store refurbishments, and shall be paid the ordinary hourly rate plus 50% for permanent team members, and the ordinary hourly rate plus 70% for casuals, in the following circumstances:

a) refurbishment shall mean a major capital expenditure and will not cover relays and other minor work in a store;

b) the Company must give one month's written notice to the appropriate Branch of the Union;

c) this provision shall apply for no more than a set 13 week period for a store;

d) work will be voluntary for all team members; and

e) this provision can only apply to one refurbishment program per store during the life of this Agreement.

Where a team member is entitled to overtime or flex up rates in accordance with clauses 6.5 and 4.2.4 respectively, they shall be paid those higher rates.

40 It will be noticed that cl 6.1.2 sets out a span of hours and cl 6.1.3 sets out various spans of hours, each of which comprises hours of work beyond the span of hours set by cl 6.1.2, and provides the applicable penalty rates for each such span. For ease of reference, the primary judge described the cl 6.1.2 span of hours as Span 1 and the cl 6.1.3 spans of hours as Span 2. I have and will adopt the same description. It is also necessary or at least helpful to the reader to understand (if this has not already been understood) that the nub of the dispute between the parties is as to whether, or as to the extent to which, the earnings specified in cl 6.1.3 in relation to an employee rostered to work Span 2 hours are captured by the phrase “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10.

41 The 2012 Agreement provides for employees to be employed as full-time, part-time or casual employees. A full-time employee is employed “by the week to work 152 hours over a 4 week cycle” (cl 4.1.1) or, in other words, employed to work a 38-hour week which may be averaged across a 4-week cycle. Other hours may also be worked by a full-time employee as overtime. Clause 6.5 dealing with overtime provides that an employee may be required to “work reasonable overtime at appropriate overtime rates”. Those rates are then set out, including for where a full-time employee is required to work before or after the employee’s rostered shift, and also where the employee either works in excess of 48 hours in any week or in excess of 152 hours in any 4-week cycle. Those arrangements prescribe the employee’s standard number of hours and recognise a dichotomy between the ordinary (ie non-overtime) hours of the employee and those additional hours that may be worked as overtime. Similar arrangements are made in relation to part-time employees which also demonstrate a dichotomy between a part-time employee’s ordinary, contracted hours and the additional hours that may be worked as overtime (see cl 6.5.2(c) and (i)). That dichotomy (for both full and part-time employees) reflects the “long-recognised distinction between ordinary hours of work and overtime” referred to by Allsop CJ in Bluescope Steel. It is a dichotomy which is reflected in various clauses beyond cl 7.2.10 where the phrase “ordinary hours” or “ordinary time”, in reference to the hours of work of an employee, are utilised (see cll 1.11(g), 4.3.1, 6.2.8, 6.2.9 and 7.13.18(b)).

42 Furthermore, the 2012 Agreement contemplates that full-time and part-time employees have regular weekly rosters which roster their ordinary hours (see cll 6.2.14-6.2.17). Clause 6.1.1 provides that an employee “may be rostered to work on any day of the week, at any time”. It is abundantly clear that an employee may be rostered to work ordinary hours of work in Span 1 or Span 2 hours or a combination thereof. The better view is that the Agreement only regards Span 1 hours as the ordinary hours of work of the workplace. For that reason, the working of an employee’s ordinary hours of work within the span of hours which are the ordinary hours of the workplace is paid for at the base rate, or what cl 6.1.2 calls the “ordinary hourly rate”. That position is consistent with what is commonly provided for by industrial instruments and is supportive of the construction I prefer.

43 The fact that an employee may be required to work their ordinary hours outside the span of the ordinary hours of the workplace (ie in Span 2) is what makes the 2012 Agreement unusual in comparison to what is more commonly found in industrial instruments. The more common (but not universal) position is that all of an employee’s ordinary hours are worked within the span of ordinary hours of the workplace and therefore paid for at the base or ordinary rate of pay. So much may be discerned from the research referred to by the primary judge at [146] of the First Judgment.

44 That unusual feature of the 2012 Agreement also serves to undermine Target’s construction in so far as it is based on the asserted customary association between “ordinary hours” and “ordinary rate of pay”. Target fails to acknowledge that that association is only applicable in the more usual case where all of an employee’s ordinary hours are worked within the span of ordinary hours of the workplace.

Further contentions relied upon by Target that must be rejected

45 Lastly, there is little or no substance in seven further matters raised by Target said to support its construction.

46 First, Target contended that the SDA’s construction did not reflect the intended operation of cl 7.2.10 because it would result in different treatment in relation to annual leave as between casual employees, on the one hand, and full-time and part-time employees, on the other. It was said that, unlike permanent employees, casuals working Span 2 hours would not have factored into their entitlements, so far as they related to annual leave, the unsociable nature of working Span 2 hours. That contention was premised on the idea that part of the 20% loading paid to casual employees is to compensate them for having no entitlement to annual leave. The suggestion here being that if the unsociable nature of Span 2 hours was intended by the Agreement to have been re-recognised for annual leave purposes it might have been expected that, on the SDA’s construction, a casual working Span 2 hours would receive an uplift on the 20% casual loading.

47 Second, Target pointed to the terms of the Target Australia Pty Ltd Award 1994 (1994 Award), which was in place at the time a clause like cl 7.2.10 was first included in the predecessor industrial agreement to the 2012 Agreement, namely, the Target Australia Pty Ltd Retail Agreement 1997 (1997 Agreement). The 1994 Award provision was cast in broad terms and the fact that the 1997 Agreement clause did not adopt the broad language of the Award was said by Target to be suggestive of the narrow scope intended for cl 7.2.10.

48 Third, Target pointed to what it suggested was a curiosity. On the SDA’s construction, an employee can accrue annual leave by working Span 1 hours but, in circumstances where that employee is moved into working Span 2 hours shortly before taking annual leave, the employee would receive paid annual leave based on Span 2 earnings.

49 Fourth, Target contended that the historical rationale for the payment of a 17.5% annual leave loading, as adopted by the framers of the 2012 Agreement, was to compensate employees for the penalty earnings (excluding penalties for overtime work) they would have earned had the employee not been absent on leave. The suggestion was that, on the SDA’s construction, there would be double compensation provided to the employees.

50 Fifth, Target sought to suggest that the SDA’s construction would put the 2012 Agreement’s provision of paid annual leave (cl 7.2.10) in tension with the provisions for personal/carer’s leave (cl 7.3.6), paid carer’s leave (cl 7.3.11) and compassionate leave (cl 7.6.8) because the payment for these other forms of leave are purely based on ordinary rate earnings and, on the SDA’s construction, the payment for annual leave is not. Target went further to say that if it was intended that persons taking annual leave were to receive payment for rostered penalties, but those on personal/carer’s leave, paid carer’s leave and compassionate leave were not, it would be expected that this would be made clear, given that annual leave is treated the same way as the other forms of leave in the NES provided for by the FW Act.

51 Sixth, Target contended that, on the SDA’s construction, the combined effect of cl 7.2.16 and cl 7.3.6 is that if an employee suffers an injury or illness whilst on annual leave their leave is recredited and the period of illness is treated as personal/carer's leave and paid at a rate that excludes any penalties. Although Target is entitled to recoup the annual leave loading pursuant to cl 7.2.16, it is not entitled to recoup any payments made that reflect the penalties payable under cl 6.1.3. This leads to the curious result that the employee is in a better position if they fall ill or are injured whilst on annual leave than if they had fallen ill or were injured whilst working. Target considers that the parties cannot have intended this result and therefore the SDA’s construction should be rejected.

52 Seventh, Target contended that the SDA’s construction involves the payment of a penalty on a penalty because the 17.5% annual leave loading is applied to “ordinary time earnings” which already encompasses the penalties provided in cl 6.1.3. It was contended that, as industrial instruments rarely provided for a penalty on a penalty, this construction cannot have been intended in the absence of plain words to this effect.

53 Before addressing some matters peculiar to one or other of the seven issues raised by Target, there are some responses applicable to all.

54 Enterprise agreements are made through the collective bargaining processes facilitated by Pt 2-4 of the FW Act. It must be assumed that the general objective of employees in such a bargaining process is to increase their wages and improve other entitlements. The general objective of the employer is likely to be to reduce employment costs or at least to resist an overall increase in employment costs. For that reason, industrial bargaining will often involve a competition between disparate interests and, in circumstances where the economic power of the bargaining parties is not in equilibrium, the resulting agreement may more likely reflect the inequality of bargaining strength than industrial fairness. Further, an enterprise agreement will likely reflect the compromises made in the bargaining process: see Reeves v MaxiTRANS Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 188 IR 297 at [19] (Ryan J). There will often be horse trading where some new entitlements will be traded for the removal of old entitlements, or some increase or decrease in an existing entitlement will be agreed to on the basis of an offset made elsewhere. Or perhaps one claim will not be pursued in order that another is achieved.

55 It is not to be expected that an industrial bargaining process will always produce an agreement where each entitlement provided will be either objectively reasonable or rational and in harmony with other entitlements, or based on some objectively discernible purpose that may have explained the reason for its adoption in a predecessor agreement made under a different bargaining process: see Shop Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Woolworths Limited (2006) 151 FCR 513 at [26] (Gray ACJ) (SDA v Woolworths). That is not to say that industrial sensibility may not provide a guide to intent, particularly where one construction of a provision would not further the industrial interests of either the employer or its employees. But it is to say that the reality of industrial bargaining must be taken into account in the search for intent. It must be recognised that industrial bargaining is driven far more by competing self-interests and economic power than by an attempt to rationally balance the legitimate interest of both the employer and employees in the way that arbitral awards are made or in the way in which it is assumed legislation like the FW Act is made.

56 Further, even if the exercise of construing an enterprise agreement was far more like construing the meaning of a statute, a mere inconvenience or the mere existence of tension as between entitlements would not displace the ordinary or natural meaning of the text. In the absence of an absurdity, or at least a very seriously anomalous result, a departure from the plain text of the enterprise agreement would not be justified: see Cooper Brookes (Wollongong) Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1981) 147 CLR 297 at 320-321 (Mason and Wilson JJ); CIC Insurance Limited v Bankstown Football Club Limited (1997) 187 CLR 384 at 408 (Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gummow JJ); Ganter v Whalland (2001) 54 NSWLR 122 at [38] (Campbell J).

57 The first matter relied upon by Target in relation to the asserted disparity between the position of casuals and permanent employees is explicable for a range of potential reasons, including because casuals are not entitled to annual leave. That alone may provide a rational reason for the differentiation in treatment suggested by Target. But, even if it were the case that a rational reason is not available, the so-called disparity may simply be a product of the employees giving greater priority in the bargaining process for the 2012 Agreement to the position of permanent employees than to that of casuals. In any event, what is suggested here is, at best, nothing more than a mere inconvenience rather than a seriously anomalous result.

58 The second matter relied upon by Target in relation to the terms of the underlying award is also not sustainable. It may be accepted that the terms of the underlying award provision provided a contextual starting point. Clause 12.1.7 of the 1994 Award relevantly provided an entitlement to be paid “the amount of wages [an employee] would have received in respect of the period of Annual Leave”. That suggests that the employee’s usual earnings were payable under the award. For present purposes, it may be accepted (as Target submitted) that the terms of the predecessor agreement to the 2012 Agreement provided for a narrower entitlement. But the fact of the change to a narrower entitlement is not informative of whether the narrowed entitlement was intended to be confined to “ordinary time earnings” as construed by the SDA, or the narrower “ordinary rate earnings” formulation for which Target contended.

59 The third matter Target pointed to was the supposed curiosity that an employee could accrue annual leave on Span 1 earnings but receive payment for annual leave on Span 2 earnings. If that is a curiosity, it is a curiosity likely to apply in a whole range of circumstances. For instance, a level 1 employee will accrue annual leave at a level 1 classification rate but, if promoted to level 2 shortly before taking annual leave, will be paid annual leave at the higher level 2 classification rate of pay (see cl 5.1.1). That is no curiosity. It is simply the result of the payment for annual leave being based on the earnings that the employee would have earned but for the absence on leave, rather than what the employee earned whilst accruing leave.

60 The fourth matter relied upon seeks to ascribe a purpose to the substantive payment of annual leave by reference to what is said to be the purpose of the 17.5% annual leave loading. As the primary judge said at [148] of the First Judgment, that purpose was said by the SDA to be nothing other than compensation for the loss of overtime earnings, whereas the position of Target was that the purpose extended beyond compensation for lost overtime to the loss of any other benefit the employee would have otherwise received, including penalties. The primary judge determined that, historically, there had been different approaches taken by industrial instruments as to the purpose of the annual leave loading. Target has neither challenged that finding or shown why I should regard it as erroneous.

61 In any event, the better view is that, whatever may have been its original purpose and even if it could be said that the purpose was generally consistent across industrial awards, with the advent of enterprise bargaining the original purpose should probably best now be regarded as consigned to history. So much is supported by the following observations made in Creighton B and Stewart A, Labour Law (5th ed, Federation Press, 2010) at 397 where the learned authors said this:

The original purpose of the leave loading was to compensate employees for the notional loss of overtime earnings during periods of leave. It subsequently spread to most sectors of the workforce, including those areas where there was normally no payment in respect of overtime. It is a benefit that has been traded away in many areas and, ironically, is now most common in non-overtime areas such as tertiary education.

The authors’ observation that annual leave loading is now a benefit that may be traded away did not appear to be in contest. As the primary judge said at [148] of the First Judgment, each of the SDA and Target relied on the extract but for different purposes. I am not satisfied that anything can be drawn from the existence of the 17.5% annual leave loading beyond the proposition apparently put by Target itself to the primary judge (albeit made in the alternative) as follows:

Leave loading can simply be viewed as a benefit bargained for and voted upon and subsequently approved by the Fair Work Commission as a term of the Agreement.

62 The fifth matter raised by Target sought to suggest a tension on the SDA’s construction between the different amounts payable for personal/carer’s leave, paid carer’s leave and compassionate leave as compared to annual leave. But again, there is no necessary irrationality or inconsistency. What was agreed to in relation to these other forms of leave may simply reflect different priorities to those which motivated the parties to agree to the entitlement to annual leave. The explicit exclusion of penalties for these other forms of leave, but not annual leave, clearly reflect an intention to treat annual leave differently. There is therefore no basis for concluding that the differential must be based on some irrationality or inconsistency. In any event, if there is irrationality or inconsistency, it would not constitute a serious anomaly.

63 As to Target’s sixth contention, the SDA submitted that it was based on misconstruing the reference in cl 7.2.16 to the period of illness or injury being “paid as ordinary time” as referring to the payment principle in cl 7.3.6 rather than as a shorthand reference to “ordinary time earnings”, as the SDA contended. That contention may well have merit but I need not determine it as, in any event, the curiosity asserted by Target that an employee would be in a better position if the employee falls ill or is injured whilst on annual leave is simply not right. If Target’s construction of cl 7.2.16 and cl 7.3.6 is correct, an employee is only entitled to be paid ordinary rate earnings for a day initially taken as annual leave but which, because of the employee’s illness or injury is effectively re-designated as personal/carer’s leave. In such a situation, there may have been an overpayment because paid annual leave may have included penalties paid under cl 6.1.3. However, the employee would not be in a “better position” because Target would be entitled to recoup any such overpayment. That is the case irrespective of whether Target can recoup those payments by way of making deductions from future earnings. I note in this respect that Target’s capacity to make deductions from future earnings is governed by s 324 of the FW Act and not the 2012 Agreement. In any event, even if this was a curiosity, it is not a serious anomaly.

64 The seventh matter raised by Target also must be rejected. The authorities relied upon by Target do not clearly support its contention that it is unusual for an industrial instrument to provide for a penalty on a penalty and, in any event, these authorities indicate that which is otherwise obvious — that it is open to parties to an agreement to agree to provide penalties on a penalty: see 4 yearly review of modern awards – Overtime for casuals [2020] FWCFB 5636 at [23]-[25] (Hatcher VP, Catanzariti VP and Bull DP); Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v SCT Logistics [2013] FWC 1186 at [16]-[17] (Commissioner Williams). Even if it is correct that industrial instruments rarely provide for a penalty on a penalty, the unusual nature of the 2012 Agreement, which requires the working of an employee’s ordinary time outside the ordinary span of hours of the workplace, may well explain why a penalty upon a penalty was agreed to here. In any event, as discussed above, the search for rationality and consistency with what might otherwise be provided in other industrial instruments is not the right approach when one is construing an enterprise agreement.

Conclusion

65 For those reasons, appeal grounds 1 and 2(a)-(d) must be rejected.

Target’s past payment practices

66 By ground 2(e) of its Notice of Appeal, Target contended that the primary judge erred in construing the phrase “ordinary time earnings” because her Honour failed to give any or sufficient weight to the fact that:

a clause in identical terms to clause 7.2.10 has been in the enterprise agreements entered into by the Appellant since 1997. Those predecessor clauses have been applied in a way that is consistent with the construction contended for by [Target] in this proceeding.

67 What Target meant by the phrase “applied in a way that is consistent with the construction contended for” was explained in its submissions by reference to Target’s past practice of providing paid annual leave to its employees under predecessor agreements. Target contended that all predecessor agreements entered into by Target since 1997 have included a clause identical to cl 7.2.10 in the 2012 Agreement (predecessor clauses). Target contended that it was an agreed fact, recorded at [64] of the First Judgment, that Target paid its employees annual leave due under the predecessor clauses in a manner consistent with its construction of cl 7.2.10. Namely, that the payment for annual leave was calculated by reference only to the ordinary hourly rate of pay payable to a full-time or part-time employee.

68 This ground of appeal, as well as the initial submissions made by Target, wrongly suggested (or wrongly stated) that the agreed fact as to Target’s past payment practice dated back to 1997. Target ultimately accepted during the hearing that the predecessor agreements in respect of which the past payment practice was agreed are those set out at [58] of the First Judgment. At the earliest, those predecessor agreements date back to 14 August 2006 in relation to two agreements dealing with regional Queensland and, at the latest, the predecessor agreements date back to 3 June 2009 in relation to the Target Retail Agreement 2008.

69 It is apparent from what the primary judge said at [65], [82] and [156] of the First Judgment, that Target relied upon its past payment practice to support its argument that there was a ‘common understanding’ as to how clause 7.2.10 of the 2012 Agreement would operate. Target argued that the past payment practice, as well as other conduct it relied upon, established the common understanding of the parties to the 2012 Agreement that “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 meant earnings calculated by reference only to the employee’s ordinary hourly rate of pay.

70 Over the objection of the SDA, the primary judge held at [159] of the First Judgment that the evidence sought to be relied upon by Target, including the past payment practice, was admissible. Her Honour at [171] to [180] then surveyed many of the authorities which have considered the concept of a ‘common understanding’ as a principle in the aide of the construction of industrial instruments. The following observations made at [31] of SDA v Woolworths by Gray ACJ were quoted by the primary judge at [173] of the First Judgment and are instructive as to the principle in question and also as to the approach ultimately taken by her Honour:

There is authority that, if a provision has appeared in a series of agreements between the same parties, and if they can be shown to have conducted themselves according to a common understanding of the meaning of that provision, then it can be taken that they have agreed that the term should continue to have the commonly understood meaning in the current agreement. See Merchant Service Guild of Australia v Sydney Steam Collier Owners and Coal Stevedores Assn (1958) 1 FLR 248 at 251 per Spicer CJ, 254 per Dunphy J and 257 per Morgan J, and Printing and Kindred Industries Union v Davies Bros Ltd (1986) 18 IR 444 at 452-453. It is necessary to take great care in the application of this limited principle, to avoid infringing the general principle that the conduct of parties to an agreement cannot be taken into account in construing the agreement. For the limited principle to operate, there must be clear evidence that the parties have acted upon a common understanding as to the meaning of the relevant provision and not for other reasons, such as common inadvertence as to its true meaning. See Australian Liquor, Hospitality and Miscellaneous Workers Union v Prestige Property Services Pty Ltd [2006] FCA 11; (2006) 149 FCR 209 at [44].

71 A further authority referred to, and of significance to the primary judge’s approach, was Sheehan v Thiess Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1762 where, as the primary judge stated at [180] of the First Judgment, Colvin J had noted that the industrial agreement there in issue:

was the type of agreement intended to apply to parties who are not participants in the process and that it may not be appropriate for surrounding circumstances to be brought to account unless they rise to the level of matters that would be notorious or known to those intended to be bound by the instrument who did not participate in the negotiations or dealings by which the terms were formulated.

72 Although not referred to by the primary judge (as the decision was handed down after the First Judgment), the observations made by Wheelahan J in Australian Rail, Tram and Bus Industry Union v KDR Victoria Pty Ltd t/as Yarra Trams [2021] FCA 1377 at [63] about the ‘common understanding’ principle should also be borne in mind (citations omitted):

great care … must be taken in drawing upon a suggested common understanding as an aid to construction … The reasons for caution before regard may be had to a suggested common understanding commence from the premise that it is the instrument itself that is to be construed, and any recourse to industrial practices said to amount to a common understanding are no more than part of the context in which the text of the instrument is to be construed. Industrial practices do not take the place of the terms of the instrument. There is also the need to maintain coherence with other principles, including that: (1) usually, recourse to extrinsic matters cannot displace the clear meaning of text; (2) the subjective understanding of individuals is rarely relevant to objective meaning; (3) this is also the case in relation to collective agreements where surrounding circumstances might have to rise to the level of being notorious or known by those intended to be bound by the instrument … and (4) parties cannot by words or conduct contract out of, or waive the terms of an enterprise agreement, which has statutory force …

73 Having considered the evidence and the relevant authorities, the primary judge concluded at [181] that “I do not consider the evidence supports a finding of an objective common intention as to the construction of cl 7.2.10” and, specifically in relation to the past payment practice relied upon by Target, said this at [182] (emphasis added):

The history or pattern of payment by Target is insufficient to justify any particular construction. It is not known whether anyone had previously complained about the calculation of their annual leave entitlement; whether the representatives at the bargaining meetings had knowledge of Target's practice of payment; nor is it known whether any failure to complain may have resulted from inadvertence or a misplaced understanding of the scope of the clause. If it were sufficient to refer to past practices, the terms of an industrial agreement could be put to the side, and any new employee would be significantly disadvantaged in seeking to understand the entitlements of their employment.

74 Further, the primary judge relevantly said at [193] and [194] of the First Judgment (emphasis added):

In summary, no consensus, agreement or admission as to the meaning of ‘ordinary time earnings’ or annual leave entitlements is disclosed. As was made clear in Shop Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association v Woolworths Limited [2006] FCA 616; 151 FCR 513 at [31], the search is for clear evidence that the parties have acted on a common intention. The subjective views of those present at the meetings do not inform the construction of the Agreement in circumstances where neither the meaning of cl 7.2.10 nor the history of Target’s payment practices could properly be described as notorious facts. There may have been one or several reasons for the Association's representatives to refrain from a further contest as to the annual leave claim, ranging from inadvertence to a deliberate decision based on broader industrial interests, to an absence of recognition of the particular terms of cl 7.2.10. These are not matters of common understanding. Additionally, Target’s reference to excluding penalties from the ambit of ordinary time earnings for other leave entitlements also indicates an absence of any clear common understanding of the meaning of that expression when used in the Agreement. There is no evidence of the information or explanation that was put to the employees at the time of the vote on the Agreement. It must also be recalled that whatever the terms of the Agreement, they were imposed upon employees covered by the Agreement. Further, having regard to all of these matters, I do not consider this to be the type of rare exception referred to in Health Services Union v Ballarat Health Service at [79] such that the Association should not be permitted to resile from whatever its particular representatives subjectively intended or expected by their reference to 'drop' in the 2012 negotiations. The nature of the negotiations does not disclose the clarity of any intervening event such as that described by Tracey J in Transport Workers Union of Australia v Linfox at [92].

The evidence of prior payment practices and the bargaining process was relevant to understanding the background facts known to both parties, but it does not evidence any common understanding. It does not assist in construing cl 7.2.10.

75 This ground of appeal as pleaded is, in-part, based on an asserted failure by the primary judge to have regard to Target’s past payment practices. In support of this ground of appeal, Target contended “that regard can be had to the way that [Target] applied the predecessors to cl 7.2.10” in order to provide context or background for construing the agreement, seemingly suggesting that the primary judge had refused or failed to have regard to that fact. However, that contention is unsustainable because, as is apparent from the reasons of the primary judge extracted above, the primary judge did have regard to the evidence in question.

76 In so far as Target’s ground of appeal seeks to assert that insufficient regard was given by the primary judge to the past payment practice, Target’s contentions did not say how or why the regard that was given was insufficient. Instead, what was in essence contended was that the evidence of the past payment practice should have necessarily led the primary judge to find that the persons who made the 2012 Agreement understood that cl 7.2.10 would be “applied in the same way” as the predecessor provisions. Although not put as such by Target, in truth this argument sought to directly challenge the factual findings made in support of the primary judge’s conclusion that the evidence did not establish a common understanding of the kind that Target suggested should have been found to have existed. As Senior Counsel for Target ultimately conceded during the hearing, Target was here contesting factual findings made by the primary, including those made at [182] (extracted above). It was also conceded that those findings were not the subject of challenge in Target’s Notice of Appeal.

77 I consider that the challenge sought to be made by Target to the factual findings made by the primary judge or, alternatively, to the failure by the primary judge to make factual findings of the kind that Target essentially says should have been made, travels beyond Target’s grounds of appeal. However, and in any event, even if I had given leave for Target to agitate the kind of challenge that, in truth, it sought to make, Target has failed to establish why the relevant factual inferences made by the primary judge were erroneous or why the primary judge erred in not making the factual inferences as to the existence of a common understanding of the kind that Target contended for.

78 Target submitted that the employees who voted to approve the 2012 Agreement “should be taken to have understood” that cl 7.2.10 would be applied in the same way as the predecessor provisions. At its core, Target’s contention amounted to little more than the submission that, having accepted the existence of the past payment practice, the primary judge erred by not necessarily inferring from that fact alone that the common understanding it contended for was held by the persons who made the 2012 Agreement. I do not accept, as the primary judge implicitly did not accept, that the second fact necessarily flows from the first. Further, Target’s contentions do not engage with what the primary judge found at [182] of the First Judgment about the insufficiency of the evidence, including that it was not known whether “the representatives at the bargaining meetings had knowledge of Target’s practice of payment”. Nor do they engage with her Honour’s findings at [193] of the First Judgment, including that there was no evidence of the information or explanation that was put to the employees at the time of the vote on the 2012 Agreement or that the history of Target’s payment practices could not be properly described as “notorious facts”.

79 Accordingly, this ground of appeal must be rejected.

Conclusion

80 For those reasons, the appeal should be dismissed.

THE CROSS-APPEAL

81 As noted at [3] above, the only issue on the cross-appeal is what is meant by the word “earnings” in the expression “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10. The question raised is whether “earnings” means the ordinary time remuneration provided for by the 2012 Agreement or, alternatively, the remuneration earned for working ordinary hours howsoever sourced, including from a contract of employment that provides for ‘over-award’ entitlements. The primary judge found that “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 only includes remuneration of the employee payable under the 2012 Agreement.

82 By its Notice of Cross-Appeal, the SDA contended that the primary judge erred in this conclusion. The SDA submitted that the primary judge should have found that “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 includes “any over-award payment”. The SDA seeks that the orders by the primary judge be set side aside and, in lieu thereof, the Court declare that:

For an employee going on annual leave, ‘ordinary time earnings’ in clause 7.2.10 of the Target Australia Retail Agreement 2012 (Agreement) includes:

…

iii. any applicable over-award payments comprising part of the employee’s remuneration for ordinary hours of work which:

1. are fixed by the employee’s contract of employment or other agreement or arrangement extraneous to the terms of the Agreement;

2. exceed the employee’s entitlements to remuneration for ordinary hours of work under the Agreement; and

3. would have been received by the employee in respect of the ordinary time which they would have worked had they not been on leave during the relevant period.

83 On the cross-appeal, the SDA relied principally upon the following two contentions to support their construction of cl 7.2.10:

(a) That the definition of “ordinary time earnings” in cl 5.4.2 of the 2012 Agreement is entirely “adopted and transposed to cl 7.2.10” save with respect to the casual loading; and

(b) That the purpose of paid annual leave is to fully, rather than partially, reflect the income that would be earned by the employee working ordinary hours if the employee was not on leave.

84 The constructional exercise should begin by recognising that the 2012 Agreement provides for ordinary time earnings as the discussion above has demonstrated. There are also provisions requiring the payment of allowances and penalty payments (cl 5.2 and cl 6.1.3). Although the term “wages” is not defined in the 2012 Agreement, all of those entitlements are what the Agreement must contemplate to be the wages the periodical payment of which is regulated by cl 5.3 and, in respect of annual leave, by cl 7.2.11 which requires that “wages in respect of the period of Annual Leave” be paid at the commencement of that leave. There is no textual suggestion that when the 2012 Agreement is dealing with any aspect of the obligation imposed on Target to pay an employee (such as the references in cl 6.1.2 or cl 6.1.3 to what an employee “shall be paid”) or the obligations imposed as to how and when an employee shall be paid “wages”, that the agreement is directing its attention to monies payable under a different instrument. That observation is consistent with what may be expected. Namely, it may be expected that, unless a contrary intention is stated or is apparent from the permissible contextual considerations that may assist the constructional exercise, an instrument dealing with how particular obligations are to be discharged will confine itself to the obligations it imposes rather than those that may be imposed by another instrument.

85 Consistently with such an expectation, it is pertinent to note that in cl 5.5.2 of the 2012 Agreement, which deals with salary sacrificing arrangements that may be made between Target and an employee, “the wages payable in accordance with the [2012] Agreement” are dealt with distinctly from “[s]uperannuation or any other benefit agreed to by [Target]”.

The definition in cl 5.4.2

86 As an express statement of a contrary intention, the SDA relied on cl 5.4.2 to support its construction that “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 encompasses over-award payments. Relying upon the primary judge’s reasons at [121], [129] and [132] of the First Judgment, the SDA contended that the definition of “ordinary time earnings” in cl 5.4.2 is not limited in its application to that clause and applies to that phrase where used elsewhere in the 2012 Agreement (except to the extent that it refers to the casual loading). Clause 5.4.2, which is set out below at [89], relevantly provides that “‘[o]rdinary time earnings’ shall include … any over-award payment”. The SDA submitted that, given the general application of the definition in cl 5.2.4, “ordinary time earnings” in cl 7.2.10 also includes over-award payments for the purposes of calculating annual leave. It was not in dispute that the phrase ‘over-award payments’ encompasses payments to an employee beyond those required by the 2012 Agreement and extends to additional amounts payable under an employee’s contract of employment.

87 The SDA’s construction must be rejected, not least because the reliance that the SDA placed on the primary judge’s reasons in the First Judgment significantly downplay or even overlook her Honour’s observations in the reasons in the Second Judgment which make it sufficiently clear that her Honour did not regard the definition of “ordinary time earnings” in cl 5.4.2 as of general application. In particular, her Honour said at [14] of the Second Judgment that the definition in cl 5.2.4 “cannot simply be adopted in the case of cl 7.2.10 … without any qualifications that the context may require”.

88 Target submitted that the SDA’s reliance upon cl 5.4.2 was misplaced because the location of the definition in a clause dealing exclusively with superannuation (an entitlement with a distinct origin and purpose) and its reference to a casual loading, make it ill adapted to be applied to annual leave.

89 Clause 5.4.2 is found in Pt 5 of the Agreement titled “Wages and Related Matters”. Clause 5.4.2 sits under a subheading titled “Superannuation”. The clauses under that subheading deal exclusively with Target’s obligation to pay superannuation to employees. Clause 5.4 provides (emphasis added):

5.4 Superannuation

5.4.1 The Company shall contribute monthly to REST on behalf of each eligible team member 9% of ordinary time earnings or such percentage of ordinary time earnings as required by legislation.

5.4.2 The Company shall contribute monthly to REST on behalf of each eligible team member 9% of ordinary time earnings or such percentage of ordinary time earnings as required by legislation.

An eligible team member is one who:

(i) Earns $450 or more in ordinary time earnings in any month; and

(ii) In the case of a team member aged below 18 years, works at least 30 hours per week.

“Ordinary time earnings” shall include the classification rate; any over-award payment; casual loadings; penalty rates; shift loadings and work related allowances that form part of the weekly rate of pay (for example, supervisory allowances).

“Ordinary time earnings” shall not include overtime; payment made to reimburse expenses (for example meal allowance or laundry allowance) or disability allowances.

5.4.3 The Company shall provide each team member, upon commencement of employment, with the appropriate membership application form(s) of REST and shall forward the completed form(s) to REST within 14 days of the team member returning completed forms to the Company.

5.4.4 (i) A team member may make personal contributions to REST in addition to those made by the Company.

(ii) A team member who wishes to make such additional contributions must authorise the Company in writing to pay into the Fund, from the team member's wages, a specified amount in accordance with the REST Trust Deed and Rules.

(iii) Upon receipt of written authorisation from the team member, the Company shall commence making monthly payments into the Fund on behalf of the team member following receipt of the authorisation.

(iv) A team member may vary his or her additional contributions by a written authorisation and the Company shall alter the additional contributions within 14 days of receipt of the authorisation.

(v) Additional team member contributions to REST requested under this sub-clause shall be expressed in whole dollars.

(vi) The ability to opt in and out of the fund as provided within the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (as amended) and the applicable regulations shall not apply.

5.4.5 An existing team member at the commencement of this Agreement who was eligible for superannuation contributions paid under the Coles Myer Occupational Superannuation Award [Print K25l7] shall continue to receive such contributions.

90 As can be seen, the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is used three times in cl 5.4.2 before being defined. It is not used again in cl 5.4. It seems clear, on its face, that the definition is directed towards those immediately preceding uses in cl 5.4.2, which all deal with an employee’s eligibility to be paid superannuation. There is no sense from cl 5.4 as a whole that the definition in cl 5.4.2 is intended to apply other than in relation to the immediately preceding uses of that phrase. There is also no express indication in cl 5.4 that the definition is intended to apply to other uses of that phrase elsewhere in the 2012 Agreement. Rather, the contrary indication is suggested by its location; not in a general definition section or dictionary clause but in a clause dealing exclusively with superannuation,

91 I acknowledge that there is also no express indication that the definition in cl 5.4.2 is not intended to apply outside of cl 5.4. This distinguishes the definition in cl 5.4.2 from other definitions in parts of the 2012 Agreement that expressly state that they only apply to certain clauses: for example, cl 7.13.12 (non working days) provides “[f]or the purpose of sub-clause 7.13.11 (a) (b), and (c), ‘day’ shall mean…” and cl 5.6.1 (supported wage) provides that certain definitions apply “in the context of this clause”. However, that, at best, is a minor inconsistency.

92 The locational indicators which, in my view, strongly tend against the SDA’s view that the definition is of general application, are supported by two further matters.

93 First, the first iteration of cl 7.2.10 in a predecessor agreement is cl 7.2.8 of the 1997 Agreement. Those two clauses are in identical terms. In the 1997 Agreement, there was no definition provided anywhere for the expression “ordinary time earnings”. That phrase was defined in the Coles Myer Occupational Superannuation Award 1992 and Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) (SGA Act), both of which were referred to by cl 5.3 in the 1997 Agreement dealing with superannuation. However, there can be no suggestion that the 1997 Agreement ‘picked-up’ the definition in one of these other instruments and then applied it generally, including in relation to cl 7.2.8.

94 There is no reason to suppose that the ordinary meaning of the expression “ordinary time earnings” as used in cl 7.2.8 of the 1997 Agreement, un-displaced as it was by any contrary indication provided by a definition, was sought to be altered when that clause was eventually replaced with cl 7.2.10 of the 2012 Agreement. If that had been intended, it is unlikely that identical language would have been used in the 2012 Agreement and that a definition would have been placed in cl 5.4.2 of that Agreement with no indication (indeed, it has the contrary indication) that it was intended to have general application.

95 Second, the reference to casual loading in cl 5.4.2 makes it ill adapted to operate as a general definition for “ordinary time earnings” in the 2012 Agreement. The phrase “ordinary time earnings” is used 16 times in the 2012 Agreement. It is used in clauses that deal with termination of employment (cl 4.6), annual leave (cl 7.2), personal/carer’s leave (cl 7.3), compassionate leave (cl 7.6), defence service leave (cl 7.9), natural disaster leave (7.11), public holidays (cl 7.13) and transport allowance (cl 8.1). It is uncontroversial that casual employees are not entitled to paid forms of leave, both generally and in the context of the 2012 Agreement (see cl 4.3.8). The 2012 Agreement also explicitly excludes casuals from payment for public holidays not worked (cl 4.3.8) and from the entitlement to receive notice, or payment in lieu of notice, for termination (cl 4.6.2). Every use of the phrase “ordinary time earnings” outside of cl 5.4, save with respect to the transport allowance, is in relation to an entitlement that is denied to casual employees. This is a strong indication that the definition in cl 5.4.2 was not intended to apply across the Agreement because the nature of the definition of “ordinary time earnings” is antithetical to the other uses of the phrase in the Agreement.

96 I acknowledge, however, that it is possible to read cl 5.4.2 as containing an implicit limitation with respect to casuals so it reads (emphasis added in bold):

“Ordinary time earnings” shall include the classification rate; any over-award payment; casual loadings (as may be applicable); penalty rates; shift loadings and work related allowances that form part of the weekly rate of pay (for example, supervisory allowances).

This construction would, to an extent, alleviate the concern that the definition is ill adapted to its application across the 2012 Agreement, particularly to clauses that deal with paid leave. However, such an implication is not supported by either the text or the context in which the definition is found. To the contrary, both the text and the context stand firmly against any such implication. Furthermore, the SDA made no attempt to justify the applicability of a broad definition of “earnings” to each of the 16 occasions where the phrase “ordinary time earnings” is used across multiple subject matters.