Federal Court of Australia

Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited v Williams [2023] FCAFC 50

ORDERS

TOYOTA MOTOR CORPORATION AUSTRALIA LIMITED (ACN 009 686 097) Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent DIRECT CLAIM SERVICES QLD PTY LTD (ACN 167 519 968) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. Paragraphs 1 to 5 of the orders made by the primary judge on 16 May 2022 be set aside.

3. The matter be remitted for re-assessment of reduction in value damages under ss 271(1) and 272(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), and damages for excess GST under ss 271(1) and 272(1)(b) of the ACL, in accordance with the reasons of the Full Court.

4. Within 14 days, each party file a written submission on consequential orders and costs.

5. Within 28 days, each party file any responding written submission on consequential orders and costs.

6. Subject to further order, the issues of consequential orders and costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[26] | |

[32] | |

Ground 1: can s 54 liability be determined on a common basis? | [32] |

[32] | |

[34] | |

[39] | |

[42] | |

[52] | |

[52] | |

[53] | |

[56] | |

[66] | |

[66] | |

[69] | |

[72] | |

[87] | |

Sections 271 and 272 and general principles concerning damages | [97] |

The notion of reduction in value in relation to consumer goods | [108] |

The proper conceptual approach in the circumstances of this case | [120] |

[137] | |

[137] | |

[143] | |

[144] | |

[145] | |

[146] | |

[148] | |

[151] | |

Market expertise as a basis for assessing reduction in value | [152] |

[162] | |

[166] | |

[219] | |

[222] | |

[250] | |

[252] | |

[253] | |

[264] | |

[270] | |

Conclusion on the extent to which the market became informed | [272] |

[273] | |

Proposition (1): Alleged error in using ‘willingness to pay’ evidence (ground 5) | [274] |

[287] | |

[292] | |

[298] | |

[302] | |

[303] | |

[317] |

THE COURT:

1 Between 1 October 2015 and 23 April 2020 (referred to as the relevant period), 264,170 Toyota motor vehicles in the Prado, Fortuner and HiLux ranges and fitted one of two particular models of diesel combustion engine were supplied to consumers in Australia. Each of the vehicles was supplied with a diesel exhaust after-treatment system (DPF system). The DPF system was defective because it was not designed to function effectively during all reasonably expected conditions of normal operation and use of the vehicle.

2 The appellant, Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Pty Ltd, is the “manufacturer” of the vehicles for the purpose of s 7(1)(e) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). Toyota also marketed the vehicles in Australia, and in doing so made representations about the quality and characteristics of those vehicles and the DPF system to prospective consumers.

3 The respondents in the appeal, Mr Williams and Direct Claim Services Qld Pty Ltd (DCS), are the cited applicants in a representative proceeding against Toyota arising from the supply of the vehicles with the defect. Mr Williams is the sole director of DCS through which he conducts his business as a motor vehicle accidents assessor. DCS acquired a Prado during the relevant period and paid the associated tax, financing and fuel costs. The Prado suffered problems associated with the defective DPF system. The parties accept that DCS is the proper claimant in respect of the vehicle which may be referred to as Mr Williams’s Prado.

4 The group members whom Mr Williams and DCS represent are consumers who, during the relevant period: (1) acquired a relevant vehicle from a dealer or other retailer (including a used car dealer) other than by auction or for the purpose of re-supply, and (2) those who acquired a relevant vehicle from such a consumer other than for the purpose of re-supply.

5 The claims made by DCS on its own behalf, and by both Mr Williams and DCS on behalf of group members, are, in summary, that:

(1) the relevant vehicles as supplied were not of “acceptable quality” and therefore failed to comply with the consumer guarantee in s 54 of the ACL; and

(2) Toyota made misleading representations and omissions about the vehicles, in contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(a) and (g), and 33 of the ACL.

6 Relief is sought in the representative proceeding under Pt 5-4, Div 2 of the ACL, which provides for remedies relating to the acceptable quality guarantee (including an action for damages against manufacturers of goods), and Pt 5-2, Div 3 of the ACL, which provides for an action for damages (relevantly because of a contravention of the general protections in Ch 2 of the ACL).

7 More particularly, “damages” are sought by Mr Williams and DCS for themselves and on behalf of group members pursuant to:

(1) ACL s 272(1)(a), for “any reduction in the value of the [relevant vehicles], resulting from the failure to comply with the guarantee”, calculated pursuant to the statutory formula prescribed in that provision;

(2) ACL s 272(1)(b), for “any loss or damage suffered by the [group member] because of the failure to comply with the guarantee … if it was reasonably foreseeable that the [group member] would suffer such loss or damage as a result of such a failure”, which was said to include excess taxes, excess financing costs, excess fuel costs and costs incurred in having the relevant vehicle serviced or repaired on account of the defect; and

(3) ACL s 236, for loss and damage suffered “because of” Toyota’s conduct in contravention of ACL ss 18, 29 and 33.

8 The initial trial of the representative proceeding was relevantly limited to, in summary, the following issues:

(1) whether there was a failure to comply with the s 54 acceptable quality guarantee and whether that could be determined on a common basis;

(2) whether there was a contravention of ss 18, 29 and/or 33 and whether that could be determined on a common basis;

(3) whether, if there was a finding of a failure to comply with the s 54 acceptable quality guarantee on a common basis, there could be a quantification of s 272(1)(a) damages, i.e., reduction in value damages, on a common basis – the respondents sought an award of aggregate damages, whether in the form of a total aggregate amount or a specified formula applicable to each group member, for any reduction in value resulting from the failure of the vehicles to comply with the consumer guarantee;

(4) whether group members had suffered damages in paying excess GST on the purchase of their vehicles and whether such damages pursuant to s 272(1)(b) could be awarded on a common basis – again, the applicants sought an award of aggregate damages; and

(5) what damages were suffered by DCS.

9 To be clear, because any damages available under ACL s 272(1)(b) (other than for excess GST) would depend on the particular circumstances of each group member, the claims for an assessment of such damages for all group members other than DCS was not to be determined at the initial trial. It was recognised that those claims would have to be determined on an individual basis. Also, other than for DCS, no damages could be determined under ACL s 236 in respect of any breaches of ss 18, 29 and 33 because questions of reliance, causation and damage would have to be determined on an individual basis.

10 Following the adoption of two reports of a referee and the parties’ agreement on a detailed statement of facts, the primary judge made a number of factual findings about the alleged defect in the vehicles: Williams v Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited (Initial Trial) [2022] FCA 344 (J). Save where indicated, none of these is challenged in the appeal. For present purposes they can be summarised as follows.

11 The diesel combustion engines in the vehicles generate pollutant emissions. The DPF system is designed to capture and convert the pollutant emissions into carbon dioxide and water vapour through a combination of filtration, combustion (i.e., oxidation) and chemical reactions. The DPF system is necessary because the vehicles are required to comply with national emissions standards.

12 The DPF system has two core components, the diesel particulate filter (DPF) and the diesel oxidation catalyst (DOC), which sit together in the DPF assembly. The DPF is designed to capture diesel particulate matter in the exhaust gas prior to its release, and to store it. The DPFs have a finite capacity to capture and store particulate matter. The particulate matter captured by and stored in the DPF must therefore be burned off periodically in a process called regeneration. Regeneration requires the exhaust temperatures to increase to the level required for the particulate matter to oxidise.

13 The referee described the core defect to be that the DPF system was not designed to function effectively during all reasonably expected conditions of normal operation and use in the Australian market. In particular, under certain conditions deposits and/or coking of the DOC prevented the DPF from effective automatic or manual regeneration.

14 When regeneration does not occur, or is ineffective, the DPF becomes blocked with particulate matter, and the vehicle experiences a range of problems. These include excessive white smoke and foul-smelling exhaust gas during regeneration and/or indications from the engine’s on-board diagnostic system that the DPF is “full”. The defect was inherent in the design of the DPF system. The design defect comprised both mechanical defects and defective control logic and associated software calibrations.

15 A key occurrence which caused the core defect to manifest was the exposure of the vehicle to regular continuous driving at approximately 100 km/h, referred to as the high-speed driving pattern. The effects of the core defect, when experienced, included excessive white smoke and foul-smelling exhaust gas being emitted from the vehicle’s exhaust during regeneration, and DPF notifications displaying on an excessive number of occasions or for an excessive period of time.

16 From February 2016, Toyota was aware that some relevant vehicles were being presented to dealers by customers who reported concerns with, among other things, the emission of excessive white smoke during regeneration and the illumination of DPF notifications.

17 Toyota attempted a series of countermeasures to fix the problem. Ultimately, only one such countermeasure was effective. It was introduced from May 2020 (the 2020 field fix). The 2020 field fix was effective and will continue to be effective in remedying the core defect and its consequences in all the vehicles. From June 2020, i.e., a month or so after the end of the relevant period, all new vehicles of the relevant type were supplied with the countermeasure which prevented the core defect from manifesting.

18 If a relevant vehicle was exposed to the high-speed driving pattern, it would experience one or more of the following consequences by reason of the core defect (referred to as the defect consequences):

(1) damage to the DOC;

(2) the flow of unoxidised fuel through the DPF and the emission of white smoke from the vehicle’s exhaust during and immediately following regeneration;

(3) the emission of excessive white smoke and foul-smelling exhaust from the vehicle’s exhaust during regeneration;

(4) partial or complete blockage of the DPF;

(5) the emission of foul-smelling exhaust from the exhaust pipe when the engine was on during and immediately following automatic regeneration;

(6) the need to have the vehicle inspected, serviced and/or repaired by a service engineer for the purpose of cleaning, repairing or replacing the DPF or DPF system (or components thereof);

(7) the need to have the vehicle inspected, serviced and/or repaired more regularly than would be required absent the core defect;

(8) the need to program the engine control module (ECM) more often than would be required absent the core defect;

(9) the display of DPF notifications on an excessive number of occasions and/or for an excessive period of time;

(10) blockage of the fifth fuel injector in the relevant vehicles (the additional injector) due to carbon deposits on its tip;

(11) the additional injector causing deposits to form on the face of the DOC, causing white smoke; and

(12) an increase in fuel consumption and decrease in fuel economy.

19 The primary judge found that although the defect consequences had not actually manifested in all of the relevant vehicles, they all had the propensity to suffer those consequences if exposed to the identified high-speed driving pattern. On that basis, his Honour found that all of the vehicles suffered from the defect.

20 In the initial trial the applicants did not seek relief under ACL s 272(1)(a) on behalf of those group members who received the 2020 field fix (referred to as the 2020 field fix group members). That was because in respect of those group members there was a live issue, to be resolved at a later date, as to the application of s 271(6). That section provides that an affected person is not entitled to commence an action to recover damages under s 272(1)(a) if they had, in accordance with an express warranty given or made by the manufacturer, required the manufacturer to remedy a failure to comply with a guarantee by repairing or replacing the goods, unless the manufacturer refused or failed to remedy the failure or failed to remedy the failure within a reasonable time.

21 Also, the claims to reduction in value damages by any group member who bought and/or sold a relevant vehicle on the secondary market (referred to as partial period group members), were excluded from assessment in the initial trial. That was because of the complexity of determining how an award in respect of a particular vehicle might be allocated between different group members who owned the vehicle at different times during the relevant period.

22 In summary, the primary judge found as follows:

(1) all the relevant vehicles, even those in respect of which the defect had not manifested, were supplied in breach of the acceptable quality guarantee, which issue can and should be decided on a common basis;

(2) on a common basis, Toyota made representations with regard to the vehicles being free of defects which were misleading, deceptive and false within the meaning of ACL ss 18, 29 and 33, but given that questions of reliance and causation still have to be determined on an individual basis it is not possible at the stage of the initial trial to deal with any damages resulting from the contravention of those sections;

(3) the failure to comply with the guarantee of acceptable quality resulted in a reduction in value of all relevant vehicles of 17.5%, meaning that their true value was 82.5% of their average retail price, and that should be decided on a common basis;

(4) group members:

(a) who had not opted out;

(b) whose vehicle had not previously been supplied to a consumer;

(c) whose vehicle had not received the 2020 field fix prior to 15 May 2022 (i.e., 2020 field fix group members were excluded);

(d) who had not disposed of their vehicle during the relevant period (i.e., partial period group members were excluded); and

(e) whose vehicle had not been returned, after the relevant period, to Toyota or a dealer in exchange for a replacement vehicle or as part of a redress program conducted by Toyota,

are entitled to recover reduction in value damages;

(5) how reduction in value damages should be assessed or distributed in respect of the vehicles excluded from the reduction in value damages referred to above should be left for later determination;

(6) damages be awarded to each group member who had not opted out for excess GST paid by the group member in connection with acquiring any vehicle to which the group member’s claim relates in an amount equal to 10% of the amount calculated as set out in (3) above; and

(7) there be judgment for DCS for its damages in the sum of $18,401.76.

23 The notice of appeal identifies 16 grounds of appeal, of which the last was not pressed. The remaining 15 grounds of appeal can be grouped and summarised as follows:

(1) Grounds 1 to 3 challenge the primary judge’s findings on liability, and in particular contend that the primary judge erred in finding that ACL s 54 had been contravened in respect of all the relevant vehicles because such a finding depends on the circumstances of supply specific to each group member, and that the defect was a defect in the DPF system and not in the vehicle.

(2) Grounds 4, 8 and 9 contend that the primary judge incorrectly construed and applied the statutory test under ACL ss 271(1) and 272(1)(a), in particular by finding that reduction in value damages must be determined with reference to the date of supply of the relevant vehicle and not with reference to the date on which any loss crystallises, and in particular without reference to the availability of the 2020 field fix. These grounds of appeal concern the primary judge’s construction of the relevant provisions and his conceptual approach to reduction in value damages.

(3) The remaining grounds concern the primary judge’s approach to the assessment of the reduction in value of the relevant vehicles. They deal with the evidence in support of the primary judge’s finding that there was a reduction in value of all relevant vehicles of 17.5%.

24 After outlining the statutory scheme, the balance of these reasons will be structured around these three groups of appeal grounds.

25 For the reasons that follow, we have concluded that the appeal fails in relation to the liability issues, but that it succeeds on the question of the proper construction and conceptual approach to the assessment of reduction in value damages, and in relation to the primary judge’s assessment of the reduction in value damages.

26 The specifics of ACL ss 18, 29 and 30 are not pertinent to the issues raised by the appeal. In broad outline, those sections prohibit conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive, or which is false, regarding, amongst other things, the nature, quality and characteristics of goods supplied in trade and commerce.

27 Part 3-2, Div 1 (the consumer guarantees, including s 54) and Pt 5-4 (the remedy provisions, including ss 271 and 272) were introduced when the ACL was first enacted in 2010: see Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth). The explanatory memorandum to that Bill indicates that the Pt 3-2, Div 1 provisions were couched in terms broadly similar to the Consumer Guarantees Act 1993 (NZ): see the explanatory memorandum at [7.9].

28 Insofar as the acceptable quality guarantee claim is concerned, s 54 provides for one of several guarantees relating to the supply of goods (in ACL Pt 3-2, Div 1, Sub-div A). Relevantly for present purposes, s 54 provides as follows:

54 Guarantee as to acceptable quality

(1) If:

(a) a person supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to a consumer; and

(b) the supply does not occur by way of sale by auction;

there is a guarantee that the goods are of acceptable quality.

(2) Goods are of acceptable quality if they are as:

(a) fit for all the purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied; and

(b) acceptable in appearance and finish; and

(c) free from defects; and

(d) safe; and

(e) durable;

as a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods), would regard as acceptable having regard to the matters in subsection (3).

(3) The matters for the purposes of subsection (2) are:

(a) the nature of the goods; and

(b) the price of the goods (if relevant); and

(c) any statements made about the goods on any packaging or label on the goods; and

(d) any representation made about the goods by the supplier or manufacturer of the goods; and

(e) any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods.

29 Sections 271 and 272 are relevantly in the following terms:

271 Action for damages against manufacturers of goods

(1) If:

(a) the guarantee under section 54 applies to a supply of goods to a consumer; and

(b) the guarantee is not complied with;

an affected person in relation to the goods may, by action against the manufacturer of the goods, recover damages from the manufacturer.

…

(6) If an affected person in relation to goods has, in accordance with an express warranty given or made by the manufacturer of the goods, required the manufacturer to remedy a failure to comply with a guarantee referred to in subsection (1), (3) or (5):

(a) by repairing the goods; or

(b) by replacing the goods with goods of an identical type;

then, despite that subsection, the affected person is not entitled to commence an action under that subsection to recover damages of a kind referred to in section 272(1)(a) unless the manufacturer has refused or failed to remedy the failure, or has failed to remedy the failure within a reasonable time.

…

272 Damages that may be recovered by action against manufacturers of goods

(1) In an action for damages under this Division, an affected person in relation to goods is entitled to recover damages for:

(a) any reduction in the value of the goods, resulting from the failure to comply with the guarantee to which the action relates, below whichever of the following prices is lower:

(i) the price paid or payable by the consumer for the goods;

(ii) the average retail price of the goods at the time of supply; and

(b) any loss or damage suffered by the affected person because of the failure to comply with the guarantee to which the action relates if it was reasonably foreseeable that the affected person would suffer such loss or damage as a result of such a failure.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1)(b), the cost of inspecting and repairing the goods to the manufacturer is taken to be a reasonably foreseeable loss suffered by the affected person as a result of the failure to comply with the guarantee.

(3) Subsection (1)(b) does not apply to loss or damage suffered through a reduction in the value of the goods.

30 Section 271(1) provides that an “affected person” in relation to the goods may recover damages from the “manufacturer”. “Affected person” in relation to goods is defined in s 2 as meaning a consumer who acquires the goods, or a person who acquires the goods from the consumer (other than for the purpose of re-supply), or a person who derives title to the goods through or under the consumer. It is by the operation of this definition that purchasers of relevant vehicles from other consumers are also group members.

31 Section 7 deals with the meaning of “manufacturer”. As mentioned, it is uncontroversial that Toyota is a manufacturer within the meaning of s 7(1)(e), i.e., a person who imports goods into Australia who is not themselves the manufacturer of the goods and, at the time of importation, the manufacturer of the goods does not have a place of business in Australia.

Ground 1: can s 54 liability be determined on a common basis?

32 By appeal ground 1, Toyota contends that the primary judge erred in finding that he could determine whether s 54 had been breached with respect to each and every group member on a common basis. Toyota contends that the primary judge should have found that whether s 54 has been contravened in the context of the supply of a vehicle is not capable of being determined as a common question because it depends on the circumstances of supply specific to each group member.

33 At the heart of this ground of appeal is s 54(3)(c)-(e) which provides that among the matters to which regard must be had in determining whether the goods are of acceptable quality are any statements made about the goods on any packaging or label on the goods, any representation made about the goods by the supplier or manufacturer of the goods and any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods. Toyota contends that those mandatory considerations direct attention to the particular circumstances of “the” supply in each case, and those circumstances could differ from one incident of supply to the next.

34 The primary judge first considered the factors identified in s 54(2) and concluded on the basis of them that the relevant vehicles did not comply with the guarantee as to acceptable quality (J[189]). His Honour then turned to the s 54(3) matters.

35 With reference to s 54(3)(d) and the statement of agreed facts, his Honour found that Toyota marketed all of the relevant vehicles throughout the relevant period as non-defective, good quality, reliable and durable vehicles that were suitable for all conditions of normal operation and use in the Australian market. Further, Toyota marketed the relevant vehicles as having a DPF system that was non-defective, of good quality, reliable, durable, without a propensity to fail and was sufficient to prevent the DPF from becoming partially or completely blocked (J[191]).

36 Although noting a “superficial attraction” to Toyota’s submission that the Court cannot determine the question of acceptable quality on a common basis because it is required to inquire into the individual circumstances of each instance of supply, his Honour identified two reasons pointing against that conclusion (J[208]).

37 First, his Honour identified that the relevant inquiry is objective, to be assessed by reference to the reasonable consumer who is taken to be “fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods)”: s 54(2) (J[209]).

38 Secondly, his Honour reasoned that in circumstances where: (1) it is alleged that the goods are not of acceptable quality by reason of a common characteristic of the goods; and (2) there is no evidence of some material difference between characteristics such as the price of the goods, the packaging or labelling of the goods, representations made about the goods by the manufacturer or supplier of the goods, or the circumstances relating to the supply of the goods, nothing in s 54 prevents the Court from assessing the quality of the goods, having regard to the matters in s 54(3), on a common basis. His Honour noted that Toyota led no evidence of, or pleaded, any material difference that is capable of bearing upon the question of whether a reasonable consumer would regard a relevant vehicle as being of acceptable quality (J[210]).

39 Toyota submits that there is a heterogeneity of group members, including individuals who made a one-off purchase and fleet purchasers who bought scores of relevant vehicles over the relevant period. It submits that in any particular case a purchaser may have been provided with specific information about Toyota’s warranty scheme and the fact that any defects are covered by that scheme, or a fleet purchaser may have been content to purchase its 500th vehicle with the knowledge that the DPF system defect in the previous 499 vehicles had not caused it any real difficulty. With reference to Owners – Strata Plan No 87231 v 3A Composites GmbH (No 5) [2020] FCA 1576; 148 ACSR 445 at [28]-[30], it submits that it is necessary to focus on the circumstances of each specific supply.

40 With regard to the primary judge placing some reliance on the fact that Toyota had not led evidence of any “material difference” between the supply of different vehicles with reference to the characteristics referred to in s 54(2)(d)-(e), Toyota submits that the primary judge was in error because there was such evidence and because it reflects an incorrect approach to the determination of common questions. In the latter regard, Toyota submits that it is simply not realistic, and would defeat the purpose of a representative proceeding, to expect Toyota to adduce evidence about the individual circumstances of the purchase of a quarter of a million vehicles.

41 Toyota emphasises that this ground of appeal is not merely a question of statutory construction. It accepts that it is not a consequence of s 54 that a breach of the acceptable quality guarantee can never be decided on a common basis. It says that it is the statutory requirement that the relevant circumstances of “the supply” must be considered, taken together with the circumstances of this case – in particular, the very substantial number of supplies over a long period of time to consumers in potentially very different circumstances who may be subject to different information and who might have different levels of tolerance for any defect – that has the result that breach of s 54 cannot be decided on a common basis in this case.

42 There can be no doubt that the assessment of whether goods are of acceptable quality within the meaning of s 54(2) is to be conducted objectively, not subjectively. That arises inescapably from the statutory inquiry being whether “a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods)” would regard the quality of the goods as acceptable. Thus, the inquiry is made with reference to a hypothetical reasonable consumer and not with reference to the particular individual consumer to whom the goods are supplied in any particular case.

43 Consideration of the matters in s 54(3), each of which is required to be considered by the injunction in s 54(2), is necessarily also undertaken from the perspective of a hypothetical reasonable consumer. That means that any idiosyncratic subjective understanding of the state and condition of the goods in issue or any idiosyncratic attitude to what is or is not acceptable, is irrelevant to the assessment required by s 54(2). As the primary judge correctly recognised, “the statutory test does not operate by reference to what a particular individual consumer knew or subjectively believed about the condition of the goods” (J[209]). Since, by the wording of s 54(3), the hypothetical reasonable consumer is taken to be fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods including any hidden defects of the goods, it is equally of no moment whether one or other consumer amongst the group members was aware to one degree or another about the defect in the vehicles.

44 It also bears emphasising that by s 54(3)(e), it is “any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods” that must be considered. There are two implications from that wording. First, it is only circumstances relating to the supply of the goods that are relevant to the question at hand, namely whether a hypothetical reasonable consumer as described in s 54(2) would regard the goods to be of acceptable quality, that are required to be considered. Thus, it is not anything said, done or known at or about the time of supply that must be considered. Secondly, from the word “other”, the matters for consideration set out in s 54(3)(a)-(d) are subject to the same relevance requirement.

45 In those circumstances, the examples provided by Toyota do not advance the argument. The first, which postulates a purchaser having been provided with specific information about Toyota’s warranty scheme and the fact that any defects were covered by the scheme, is not a circumstance relevant to whether a reasonable consumer who had knowledge of the defect would regard the vehicle as being of acceptable quality. That is because during the relevant period there was no fix for the defect, so the postulated information cannot be a statement to the effect that the defect would be fixed under the warranty. It can only be some broader statement about the warranty which is not relevant.

46 The second example, being the fleet-owner purchaser who was indifferent to the defect, is not relevant because, as explained, the idiosyncratic attitude of what is or is not acceptable is not to the point. The inquiry is objective.

47 The principal difficulty with Toyota’s argument on this ground of appeal is that it allows for a situation where two identical vehicles are subject to different conclusions with regard to their being of acceptable quality based on what the particular purchaser in each case knew or did not know, or cared about or did not care about. That form of subjectivity is exactly what s 54 eschews.

48 With regard to the authorities, it is to be noted, as it was by the primary judge (J[207]), that in several cases the question of acceptable quality has been decided on a common basis: Medtel Pty Ltd v Courtney [2003] FCAFC 151; 130 FCR 18; Ethicon Sàrl v Gill [2021] FCAFC 29; 288 FCR 338; Capic v Ford Motor Company of Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 715; 154 ACSR 235. As acknowledged by the primary judge (J[201]-[202]), there are also cases in which the question of acceptable quality has been held not to be susceptible to determination on a common basis. Owners – Strata Plan, particularly relied on by Toyota, is one. Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Ltd v Peterson [2011] FCAFC 128; 196 FCR 145 is another. It is not necessary to consider those cases in detail because even accepting that on the facts of those cases there may have been circumstances particular to an individual group member that was relevant to the question at hand, that has not been shown to be the case in the present matter.

49 That takes us to the outstanding matter to consider, which is Toyota’s submission that the primary judge was wrong to have held that the onus lay on Toyota to adduce evidence of any relevant circumstances peculiar to one or other group member in order to establish a foundation for its argument that the question of acceptable quality cannot be decided on a common basis. His Honour identified that Toyota had not pleaded or otherwise raised any relevant, material difference between the circumstances of any given instance of supply of a relevant vehicle capable of bearing upon the question of whether a reasonable consumer would regard the vehicle as acceptable (J[211]). Toyota does not cavil with that characterisation of how the case was run. Clearly enough, the issue of whether the relevant vehicles were of acceptable quality could and should be determined on a common basis was one of the issues squarely identified by the parties as arising for determination at the initial trial, and it was identified by the primary judge as such (J[199]).

50 As submitted on behalf of the respondents, if Toyota wished to demonstrate through evidence, as opposed to mere speculation, that there was a sound basis in fact for the Court to refrain from determining the issue on a common basis, it could and should have led relevant evidence. As identified by the primary judge (J[193]), that need not have been of the circumstances of every one of the quarter of a million supplies; evidence of materially different relevant circumstances of even one supply may have been sufficient, but not even that was done. In the absence of that, and in light of the compelling generalised evidence in support of a finding that the vehicles were not of acceptable quality (canvassed at J[15], [32]-[86], [173]-[198]), there was no error in the primary judge’s approach to, and conclusion on, the question of commonality.

51 It follows that ground 1 fails.

Grounds 2 and 3: was there a defect in the vehicles?

The substance of grounds 2 and 3

52 By these grounds of appeal, Toyota contends that the primary judge erred in finding that there was no distinction between a defect in the DPF system and a defect in the vehicles. It is said that the primary judge erred in his treatment of the evidence on this question. It is also said that a consequence of the primary judge’s error on this question is that the primary judge erred in concluding that Toyota had made representations about the vehicles in contravention of ACL ss 18, 29 and 33, i.e., the representations about the vehicles were not in contravention of those provisions because there was nothing wrong with the vehicles – the problem was with the DPF system.

The primary judge’s reasoning

53 The primary judge reasoned that Toyota’s efforts to divorce issues with the DPF system from the relevant vehicles is entirely superficial. The DPF system is in the vehicles in order to ensure that the vehicles comply with Australian emissions rules, and is therefore a critically important component of the vehicles, the proper functioning of which is likely to be of concern to a reasonable consumer. His Honour found that even though the vehicles could still be driven from A to B, the consequences of the core defect are such as to substantially interfere with the normal use and operation of the vehicles (J[80], [81]).

54 His Honour identified the warning notifications to the driver in the event of the DPF becoming full or blocked, directing the driver to take the vehicle to an authorised dealership, failing which if the vehicle continued to be operated it would go into “limp mode”. Also, his Honour reasoned that plumes of dense white smoke being emitted from the vehicle are not conducive to a safe driving environment. His Honour also referenced tens of thousands of customer complaints that illustrate the obvious point that the defect consequences are not trivial and have a significant impact upon consumers’ use and enjoyment of the vehicles (J[81]-[85]).

55 Finally, the primary judge reasoned that Toyota’s attempt to downplay the significance of the core defect is inconsistent with its contemporaneous conduct and internal communications. Those showed that Toyota had significant concerns about how the problems experienced by the vehicles would impact on Toyota’s brand and reputation, and it apprehended that the issues with the vehicles were of a serious nature and materially affected consumers’ use and enjoyment of them (J[86]).

Consideration

56 Toyota submits that the primary judge’s “key error” was to hold that although the DPF system was in the vehicles to ensure compliance with emissions rules, it “does not matter” whether the respondents sought to prove that the vehicles in fact failed to comply with those rules. The answer to that is that his Honour’s finding about the reason for the DPF system being in the vehicles is about the DPF system being “a critically important component” of the vehicles, and hence a defect in the DPF system is properly regarded as a defect in the vehicles. Because of the need for the vehicles to comply with emissions rules for them to be supplied in Australia, and that the DPF system was designed to ensure such compliance, the DPF system is an inherent and incorporated component of the vehicle – it is not an accessory. It can have a defect of such a nature as to render the vehicles not of acceptable quality within the meaning of s 54 whether or not the defect affected the vehicles’ compliance with the emissions rules.

57 As the respondents submit, complex goods such as motor vehicles are manufactured from innumerable components. It is conceptually flawed, and would render s 54 essentially inoperative in respect of most consumer goods, if a failure of a component could not as a matter of construction be regarded as a defect in the vehicle. The question has to be approached by asking whether the defect is such as to cause the relevant goods to be of an unacceptable quality within the meaning of s 54. It cannot be directed at the level of individual components which were not supplied separately or individually but rather form an inherent part of the goods as a whole.

58 The statutory standard embodied in s 54 accommodates the situation of minor defects in goods through the element of degree, which is the appropriate way to analyse a scenario where the defect affects only minor component parts such that it would be of limited significance to the hypothetical reasonable consumer. The present case is far removed from that. As mentioned, the presence of the defect in the DPF system in the vehicles meant that a vehicle could not be exposed to regular highway driving without malfunctioning and triggering serious consequences. It is hard to conceive of a scenario in which the hypothetical reasonable consumer would not regard such consequences as unacceptable.

59 Toyota submits that the evidence does not support the primary judge’s finding that the core defect “substantially interfered” with the normal use and operation of the vehicles. That is because the consequence of the defect, if it manifested, was that the vehicle would provide warnings that it required “unscheduled maintenance” and it was only if the user did not have that maintenance undertaken that the vehicle would go into limp mode. On that basis, Toyota submits that the vehicle going into limp mode is a consequence that is remote from the occurrence of the defect in the DPF system which means that it is not a defect in the vehicle that a reasonable consumer is likely to regard as unacceptable.

60 Toyota’s focus on the limp mode ignores the myriad other defect consequences found by the referee and agreed by the parties which, when they manifest, substantially interfere with the use and enjoyment of the vehicle. These include the defect consequences identified above at [18].

61 Next, Toyota submits that the primary judge erred (at J[84]) in relying on Mr Williams’s evidence about white smoke being “dangerous” when the respondents had not mounted any case that the defect gave rise to any safety issue and Mr Williams could not provide expert evidence of that nature. However, although his Honour referred to Mr Williams’s evidence that white smoke entering the cabin of the vehicle was “dangerous”, the finding was that “plumes of dense white smoke are hardly conducive to a safe driving environment”. There is no error in that finding – the primary judge was plainly in a position to make that assessment based on the evidence that was adduced. In any event, his Honour recorded that he placed “minimal weight on this factor” in reaching his conclusion on the s 54 question.

62 Toyota submits that the primary judge was wrong (at J[85]) to rely on “tens of thousands of customer complaints” and Mr Williams’s evidence to conclude that the consequences of the defect in the DPF system were “not trivial”. Although accepting that tens of thousands of customers had difficulties with the consequences of the defect and they made complaints or had repairs carried out under Toyota’s warranty program, Toyota submits that without analysing each complaint or warranty claim individually it is not possible to conclude that they all related to vehicles with the DPF system defect. For example, it is said that a large number of complaints related to the fact that the DPF system was not able to automatically regenerate if the vehicle is driven consistently at low speeds or for short trips – which was not a design defect. Also, some white smoke was a consequence of the ordinary operation of the DPF system. Toyota submits that it is not possible to disentangle which customer complaints or warranty repairs were carried out because of the low-speed driving pattern or the vehicle’s ordinary operation.

63 As submitted on behalf of the respondents, the primary judge relied on the customer complaints as probative of the fact that, when vehicles experience issues consistent with the defect consequences (for example, the emission of excessive white smoke, malodorous exhaust and irregular servicing), those issues tend to impact significantly on the owners’ use and enjoyment of the vehicles (J[183]). The probative value of the evidence was not dependent on proof that the issues the subject of the customer complaints were caused by the defect in the DPF system. Rather, it was sufficient that the issues complained of were consistent with the defect consequences, regardless of the cause.

64 Also, it was not necessary for the primary judge to review each of the tens of thousands of customer complaints, the records of which were produced on discovery by Toyota, to conclude that the defect consequences impact significantly on the owners’ use and enjoyment of the vehicles. If Toyota’s contention had been that the complaints did not arise from the defect in the DPF system, as it apparently contends on appeal, then it was open to it to analyse the records of the complaints and identify complaints that it says were unrelated to the core defect or inconsistent with the defect consequences. It failed to do that.

65 There is no error in the primary judge’s findings and reasoning to the conclusion that the defect in the DPF system amounted to a defect in the vehicles which rendered the vehicles of unacceptable quality and their supply to thus be in contravention of the acceptable quality guarantee in s 54. Grounds 2 and 3 in the appeal accordingly fail.

Issues concerning construction and conceptual approach

66 In this section of these reasons, we deal with grounds 4, 8 and 9 of the notice of appeal, which challenge the primary judge’s construction of ss 271 and 272 and his conceptual approach to reduction in value damages.

67 Broadly, by these grounds, Toyota raises the following contentions:

(1) that the primary judge erred in applying the test under ss 271(1) and 272(1)(a) by finding that damages for any reduction in value must be assessed by reference to the time of supply, rather than by reference to the date on which any loss crystallises (including by reference to any later events) (ground 4);

(2) because the primary judge did not assess damages by reference to the date on which any loss crystallises, his Honour erred in not taking into account certain evidence demonstrating that affected persons had not suffered any damage (the matters relied on by Toyota include the referee’s finding that the 2020 field fix was effective) (ground 8); and

(3) in light of these errors, the primary judge erred by failing to take into account matters relevant to the assessment of damages for any reduction in value in the relevant vehicles, including the secondary market data analysed by Mr Stockton, the existence of the 2020 field fix, whether and to what extent and when the defect consequences manifested in a relevant vehicle, the resale value of the relevant vehicles compared to comparable vehicles and whether group members had sold their vehicles and the prices achieved for any such sales (ground 9).

68 Evidentiary issues raised by these grounds, such as issues relating to the secondary market data analysed by Mr Stockton, are considered later in these reasons under the third group of appeal grounds.

The nature of the damages claim at the initial trial

69 As we have noted, Mr Williams and DCS as representative applicants sought aggregate damages for reduction in value resulting from the failure by Toyota to comply with the consumer guarantee. However, no such award was sought in respect of those group members who had taken advantage of the 2020 field fix. Further, the proper approach to those group members who bought and/or sold a relevant vehicle on the secondary market (i.e., partial period group members), including whether an award of damages for reduction in value could be made in their favour on an aggregate basis, was reserved for later consideration.

70 Accordingly, when it came to aggregate damages, the focus of the primary judge was on the claim for reduction in value made in respect of those group members who had bought their vehicle from a Toyota dealer and who still owned the vehicle when the 2020 field fix was made available at no cost (the relevant cohort).

71 The claim by the representative applicants that an assessment could be made that covered all group members in the relevant cohort was founded on the premise that, for all of them, the reduction in value was the same. For reasons that have been given, to the extent that the premise was based upon the proposition that the relevant value was to be determined objectively and not by reference to the particular sensibilities of individual owners when it came to the defect and its consequences, the premise was correct. However, there remain issues in the appeal as to whether, on the correct conceptual approach, the objective assessment of damages for reduction in value is the same for all members of the relevant cohort and, if so, whether the primary judge was correct in concluding that a loss of 17.5% of the relevant retail price had been proven.

The primary judge’s construction and conceptual approach

72 The primary judge reasoned by the following steps in determining what his Honour described as “reduction in value damages”.

73 First, the primary judge conceptualised “reduction in value” as the price that would need to have been offered in order to sell all of the relevant vehicles assuming that the buyers were aware of the defect: J[273]-[276].

74 Secondly, the primary judge considered whether (a) the willingness to pay of the marginal consumer; or (b) the repair cost to remedy the defect may be used as a measure of the “reduction in value”. His Honour reached the following conclusion at J[297]:

To my mind, it is erroneous to shoehorn any conception of “reduction in value” as only being able to be derived by comparison to market value. Concepts such as repair cost and [willingness to pay] are useful indicators in ascertaining any reduction in value.

The reference to the “marginal consumer” is to the last buyer who had to be persuaded to enter the market to buy a vehicle in order to clear the available supply. The price had to be low enough for that buyer to be willing to pay for the vehicle. Inherent in the concept is the notion that many buyers may have been willing to pay a higher price but the market price needs to be set at a level that is low enough for a buyer to be found for each of the defective vehicles.

75 In the course of reasoning to that conclusion, his Honour dealt with criticisms as to the use of the notion of the consumer’s willingness to pay to ascertain the “reduction in value”. He did so in the following way at J[295]:

The criticism that a consumer still recovers damages notwithstanding that the level of their reduced individual [willingness to pay] may exceed the level at which a supplier wishes to supply is somewhat of a false issue. The reduction in value loss arises because the vehicle’s true value at the time of purchase (which is objectively assessed) was less than the purchase price, not because the individual consumer’s true [willingness to pay] was less than the purchase price. In this regard, Mr Boedeker calculated the reduced [willingness to pay] for the marginal consumer, which approximates the price decrease that would have been required in order for [Toyota] to sell the same number of Relevant Vehicles with the defect disclosed. This represents the true value, because it is the price that would need to have prevailed in the marketplace in order for the same volume of vehicles to have been sold in the light of market knowledge of the [defect].

76 It can be seen that the evidence as to willingness to pay was viewed by the primary judge as a means by which to ascertain the price at which the defective vehicles would need to have been offered in order to clear the market.

77 Thirdly, the primary judge accepted the contention advanced by the representative applicants to the effect that the reduction in value was to be assessed by reference to the time at which the vehicle was supplied without reference to events which occurred subsequently (but that information which bears upon the assessment of the value of the goods at the time of supply can be taken into account): J[299]-[301].

78 Significantly, this aspect of the reasoning was part of the foundation for his Honour’s conclusion that reduction in value damages could be assessed for all members of the relevant cohort on a common basis. In that regard, his Honour observed at J[325]:

The reduction in value damages sought by group members are referable to that common propensity inherent in the Relevant Vehicles on the date of supply. This fortifies the view that this loss also can be assessed on a common basis, because it is based on a propensity common to all the Relevant Vehicles at the time of acquisition.

79 Fourthly, as to the relevance of evidence concerning matters which occurred after the date of purchase, his Honour concluded that such evidence could be adduced to demonstrate “what in fact the nature of the defect was” and to demonstrate the extent of any fall in the market price for the vehicles at a time when the market became fully informed of the defect because that evidence “may provide information relevant to assessing the true value at the time of acquisition”: J[328].

80 However, the focus upon the need to demonstrate evidentiary significance for establishing the factual position as at the date of purchase led his Honour to disregard the availability of the 2020 field fix in assessing damages. As to the lack of relevance of that fact to assessing the reduction in value damages, his Honour reasoned as follows at J[328]:

… if a repair became available four years after the date of acquisition and was implemented more than a reasonable time after being requested, this would not be relevant to the true value at the time of acquisition. The repair was not expected at the time of acquisition, so it is an extraneous event, irrelevant to the true value at that time.

81 It may be noted that the references to the repair becoming available four years after acquisition and the repair not being implemented within a reasonable time after being requested, reflect the terms of evidence given by Mr Williams as to his own experience. It does not reflect the position for all members of the relevant cohort some of whom bought their vehicle just before the 2020 field fix was available and may have been able to secure a prompt repair. Of significance for present purposes is the fact that the reasoning by the primary judge treated the possibility of repair as an extraneous event throughout the whole of the period when members of the relevant cohort purchased their vehicles. The primary judge approached all members of the relevant cohort on the same basis without any allowance for the different circumstances that may have pertained to them as time went on. Nor did his Honour make any allowance for the prospective restoration of value that was made possible by the availability of the 2020 field fix at no cost to the owner of the vehicle.

82 His Honour’s approach meant that a consumer may recover reduction in value damages on the basis that the vehicle as purchased was defective as well as ultimately receive the benefit of the 2020 field fix (at no further cost) thereby restoring the value at that point in time. The submissions for Toyota concerning the grounds relating to the assessment of damages emphasised this apparently anomalous outcome.

83 Although the primary judge’s approach to assessment of the reduction in value of the relevant vehicles is the subject of the third group of appeal grounds (considered later in these reasons), it is convenient to outline his Honour’s approach to, and conclusions about, assessment at this stage. The primary judge began the quantification task by emphasising statements in the authorities to the effect that undertaking a valuation process does not admit of a single precise answer especially where it is being undertaken on the basis of a hypothetical: J[340]. His Honour referred to authority to the effect that it is a “commonsense endeavour” to be undertaken as a matter of judgment based upon the available evidence rather than as an arithmetical exercise: J[342]-[343], see also J[391]-[392]. No issue arises in the appeal as to this approach in terms of legal principle. Rather, the contentions advanced by Toyota (by the third group of appeal grounds) concern the extent to which there was sufficient (or any) material upon which to base such an assessment.

84 Ultimately, after a critical consideration of the expert evidence exposing the deficiencies in the various approaches adopted by the experts, his Honour reached his conclusion as to quantification in the following way: J[393]:

The applicants advocate for a reduction in value of 25 per cent. There is always a difficulty in settling upon a pin-point figure in cases of this type. Doing so, although necessary, tends to lend a patina of precision to what in truth is an evaluative and imprecise exercise upon which, at least at the margins, reasonable minds may differ. I am inclined, however, to consider the figure fastened upon by the applicants as being simply too high. My reasons for this conclusion have been addressed in relation to my findings as to the expert evidence, which has led me to conclude that although the evidence of Mr Boedeker and Mr Cuthbert has some force, a number of the criticisms directed to its accuracy and reliability also have merit. But the conclusion that a reduction in value must still be a figure of significance not only aligns with common sense, but more specifically, my perception of the evidence of Mr Williams and the effect of the Defect Consequences more generally, as borne out by the customer complaints (as to which see [183]). Doing the best I can, a reduction in value in the range of 15 per cent to 20 per cent is appropriate having regard to all the evidence. Given the need to land on an exact figure, I should settle in the middle of this range, that is, a reduction of 17.5 per cent.

85 The above conclusion was said by the primary judge to be reached by giving weight “to the entirety of the expert evidence and the submissions advanced by the parties in respect of that evidence”: J[392]. It was expressed as a form of evaluative synthesis of the evidence recognising its problems and shortcomings to derive a single value. It was reached in circumstances where the expert evidence adduced by Toyota was in the form of criticisms of the evidence led in support of the claim rather than in the form of providing any real analysis as to a different methodology: J[394]. In short, Toyota’s case before the primary judge was that it maintained that no loss had been demonstrated. It did not present expert evidence as to an appropriate value that might be determined if the Court was of the view that there was a relevant reduction in value.

86 As has been noted, for all group members in the relevant cohort, his Honour made orders to give effect to his assessment that the reduction in value was 17.5%.

The parties’ submissions on appeal

87 Toyota challenges the primary judge’s construction of ss 271(1) and 272(1)(a) and his conceptual approach to reduction in value damages. Toyota submits that the correct conclusion is that the time of assessment is when such damage crystallises, for example, upon a sale of the vehicle. Toyota submits that, in the absence of a sale, damages are to be assessed at the time of the trial, based on all the available information at that point.

88 Toyota emphasises that, in May 2020, it developed a field fix (namely, the 2020 field fix), which was wholly effective in remedying the defect and was available, free of charge, to everyone who had purchased the vehicles in the relevant period. Toyota submits that, despite this, the primary judge found that purchasers of the vehicles who continued to hold the vehicles at the end of the relevant period remain entitled to damages equal to a 17.5% reduction in the applicable price of the vehicles.

89 Toyota submits that, in order to calculate the “damages” for reduction in value, s 272(1)(a) requires the reduction in value to be calculated at the time that any damage to the affected person crystallises. Toyota makes the following submissions:

(1) First, the overarching enquiry required by s 272(1) is whether the consumer has suffered loss or damage for which they should be awarded “damages”. If s 272(1)(a) was intended to operate by reference to the value of the vehicle at the time of purchase only, the section could easily have said so. It does not. Rather, it directs attention, in the chapeau, to whether damages should be awarded (implicitly, for loss or damage).

(2) Secondly, s 272(1)(a) provides for calculation of “any reduction” in value. Unlike the latter parts of the subsection, the reduction in value is not linked to any particular time period.

(3) Thirdly, as identified by the reference to “damages” in both ss 271 and 272, the purpose of the section is an award of damages. Accordingly, the compensatory principle applies: see HTW Valuers (Central Qld) Pty Ltd v Astonland Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 54; 217 CLR 640 at [63]-[65]. Damages should be assessed so as to compensate the injured party for the wrong done. The primary judge recognised this fundamental principle but did not apply it. Requiring reduction in value to be assessed, in every case, at the time of purchase does not reflect that principle. It pays no attention to whether the consumer has suffered any damage in any real sense.

(4) Fourthly, the affected person must suffer a reduction in the value of the goods “resulting from the failure to comply with the guarantee”. This also indicates a notion of actual loss or damage by reference to the failure to comply, rather than a hypothetical calculation at the time of purchase, regardless of circumstances.

(5) Fifthly, s 271(6) expressly contemplates that events subsequent to the supply of the goods must be taken into account and does not require those events to be within any particular time after the purchase of the goods: it contemplates the manufacturer repairing the goods within a “reasonable time” of being requested to do so. There is nothing in either s 271 or 272 to suggest that consideration of later events is limited to s 271(6).

(6) Sixthly, s 272(3) provides that s 272(1)(b) does not apply to loss or damage suffered through a reduction in the value of the goods. The emphasis is on loss or damage “suffered through” a reduction in value, which is a further indication that the purpose of the section is to compensate for actual loss or damage.

90 The respondents support the approach adopted by the primary judge. The respondents submit that Toyota’s construction is wrong, and the primary judge was right to reject it. The respondents submit that it is contrary to the statutory text, context and purpose.

91 The respondents submit that: much of Toyota’s argument implicitly treats motor vehicles as if they are financial assets like shares or income producing assets like a shopping centre, the value of which may be ascertained by the trading value of the asset from time to time; the value of durable consumer goods like motor vehicles is substantially different, and the impaired expected functional utility of a new vehicle has an impact on value that does not depend upon some subsequent event, such as resale, to “crystallise” the loss; nor is the resale value of a vehicle on the second-hand market a direct proxy for the diminished value at the time of the original supply; it is at most a potential source of useful data; this has implications for the proper construction of s 272(1)(a), appreciating that the provision should be construed in a way that serves the remedial purposes of the ACL (see Henville v Walker [2001] HCA 52; 206 CLR 459 at [135]); if that subsection were construed as focusing on the time when the goods are resold, or on what the goods could be sold for in a relevant market at the time of trial, it would treat all “goods” to which the section applies as mere financial assets whose value derives solely from the fact they can be resold for a price; however, such a construction is impossible to reconcile with the context of a consumer law provision concerned with the supply of goods to consumers.

92 The respondents make submissions about the consumer-protection purpose of the ACL. The respondents submit that: the particular goods to which an action under ss 271(1) and 272 applies are goods acquired as a “consumer” (see ACL s 54(1)(a)); these are defined relevantly by ACL s 3 as goods that are of a kind “ordinarily acquired for personal, domestic or household use or consumption” and not those acquired for re-supply; the relevant Part of the ACL expressly does not apply to financial services or financial products (see s 131A(1) of the CCA); the “goods” to which s 272(1)(a) applies are therefore consumer goods the value of which principally derives not from their resale value, but from their expected use or enjoyment by the consumer; it cannot even be said that consumer goods are routinely resold; it is improbable in this context that the legislature intended the reference to the “value” of goods in s 272 to be tied to an actual or notional resale value of goods in the second-hand market.

93 The respondents submit that: informed by this purpose and context, it is plain that the ability to recover reduction in value damages under s 272(1)(a) for non-compliance with the guarantee of acceptable quality is directed to the problem of consumers bargaining for non-defective goods but receiving instead defective goods which, by reason of their true nature and condition, have lower expected use and enjoyment; such a consumer has overpaid at the point of supply, because they received a good worth less than they bargained for; this constitutes an immediate loss (see HTW Valuers at [33]); the ACL confers statutory redress for that loss.

94 The respondents submit that the primary judge gave six cogent reasons for construing s 272(1)(a) as requiring reduction in value to be assessed at the time of supply (J[301]-[325]). The respondents submit that all of them were correct. The respondents’ submissions include the following:

(1) Paragraph (a) of s 272(1) is a composite provision that calls for a comparison between the lower of the prices mentioned in s 272(1)(a)(i) and (ii), which are prices necessarily pertaining to the time of supply, and the value of the goods. It plainly indicates an “apples with apples” comparison that necessarily requires the reduced value arising from non-compliance with the guarantee to be assessed at the same time as the comparator prices. This is also logical because it means reduction in value is assessed at the same time as non-compliance with s 54.

(2) By directing attention to the reduction in value below the purchase price or average retail price, s 272(1)(a) reflects a legislative intention to compensate the consumer for having purchased goods for more than they were worth and to compensate the overpayment. “Reduction” in this context is not used to describe a process of reduction in value occurring over time. It is a reference to the true value of the defective goods being less than, and thus a reduction from, the wrongly assumed value reflected in the purchase price (whether actual or averaged). This is reinforced by the contrast with s 272(1)(b), which provides for recovery of reasonably foreseeable loss or damage after supply. Toyota wrongly submits in response that the loss in value at the time of supply due to the defect is “entirely theoretical”. This is to ignore the fundamental consumer protection object of the CCA, and the fact that s 272(1)(a) applies to consumer goods whose value lies principally in their expected use and enjoyment. Once it is appreciated that the loss is having acquired goods at an artificially inflated price, there is no basis to describe the loss at the time of supply as being merely “theoretical”. It is also erroneous to say that no loss has “crystallised”. It is the overpayment at the time of supply that causes immediate loss: HTW Valuers at [33].

(3) By reading the reduction in value as a matter to be assessed at the time of supply, s 271(1)(a) can be read harmoniously with s 271(6). Toyota submits there is no lack of harmony on its construction, because s 271(6) expressly contemplates that events subsequent to the supply of the goods must be taken into account. However, no such contextual indication arises from s 271(6). That subsection does not “take into account” subsequent events (like a repair) in assessing whether there was a reduction in value. Section 271(6) simply denies relief altogether when a repair is provided within a reasonable time of a request under an express warranty. If Toyota’s construction were adopted, s 271(6) would be otiose, because on its view of s 272, a repair (or even the mere availability of a repair) reduces any reduction in value to nil, regardless of whether or not it was provided within a reasonable time.

(4) The primary judge’s approach was consistent with the decisions in Capic and Vautin v By Winddown, Inc (formerly Bertram Yachts) (No 4) [2018] FCA 426; 362 ALR 702. Although the Full Court is not bound by those decisions, they illuminate why the time of supply is the correct reference point. Both decisions make clear that s 272(1)(a) connects reduction in value with failure to comply with the guarantee, which arises from the inherent propensity for adverse consequences that existed at the time of supply: Capic at [884]; Vautin at [292].

95 While the appeal was reserved, the Court wrote to the parties seeking submissions on a possible alternative approach to reduction in value damages that had not been the subject of submissions at the hearing. The Court’s letter stated in part:

Grounds 4, 8 and 9 of the notice of appeal raise an issue as to whether the primary judge erred in his construction or approach to the assessment of damages for reduction in value under s 272(1)(a) of the ACL. … For present purposes, it is assumed that grounds 1 to 3 of the notice of appeal are not made out. It is also assumed that upon a proper construction of s 272 of the ACL, in any action for damages under the provision, the Court may assess the reduction in value at the time of supply or at some other appropriate time but, in any case, for the purpose of ensuring that any award of damages fairly compensates the claimant, the Court may assess the quantum of damages to be awarded having regard to the known circumstances at the time when the assessment is being undertaken.

If the Court were to form the view that, in the circumstances of the case, in order to fairly compensate the relevant group members (that is, the group members covered by the primary judge’s aggregate damages award) for any reduction in value resulting from the failure to comply with the acceptable quality guarantee, it is appropriate to have regard not only to any reduction in value at the time of supply, but also to subsequent events, a possible approach to the assessment of damages is as follows. As this possible approach was not the subject of submissions at the hearing, the Court wishes to raise it with the parties and give them the opportunity to make submissions about it.

The approach involves taking into account not only any reduction in the value of the vehicle at the time of supply, but also the availability of the 2020 field fix, the period of time that the consumer owned the vehicle before the fix became available, and the effective life of the vehicle. The approach is as follows:

(a) First, calculate any reduction in the value of the vehicle as at the time of supply (in dollars) on the basis of a percentage reduction in value applicable to all relevant vehicles. The percentage assumes that the defect will remain in place for the whole of the effective life of the vehicle.

(b) Second, calculate the period of time (in months) that the group member held the vehicle before the 2020 field fix became available (i.e. the period of months from the date of supply to May 2020).

(c) Third, determine the effective life of the defective vehicle (in months). This may be able to be determined on a general basis for all relevant vehicles, or all relevant vehicles of a particular type.

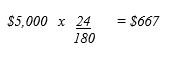

On this approach, any damages to be awarded for reduction in value under s 272(1)(a) would be:

The approach can be illustrated by the following example. Assume that the price paid or payable by the consumer for the vehicle (and the average retail price of the vehicle) is $50,000. Assume that the percentage reduction in value for all relevant vehicles (assuming the defect remains in place for the whole of the effective life is the vehicle) is 10% and that, accordingly, the reduction in the value of the vehicle as at the time of supply is $5,000. Assume that the consumer purchased the vehicle in May 2018, and thus held the vehicle for 24 months before the 2020 field fix became available. Assume that the effective life of the defective vehicle is 15 years (i.e. 180 months). The damages under s 272(1)(a) would be:

While the above formula would need to be applied on a case-by-case basis to each relevant vehicle, additional individual circumstances (such as whether and the extent to which the defect consequences were experienced) would not be taken into account for the purposes of assessing damages for reduction in value.

96 The parties filed submissions, and responding submissions, in relation to the possible approach set out in the letter from the Court. Ultimately, as set out later in these reasons, we do not adopt the possible approach set out in the letter. We have concluded that matters of that kind should be considered on remitter (see below).

Sections 271 and 272 and general principles concerning damages

97 Sections 271 and 272 create a right of action for damages against the manufacturer where there has been a failure to comply with (relevantly) the acceptable quality guarantee. It is uncontroversial that the word “damages” in ss 271 and 272 is used in the sense of statutory compensation. It is implicit in the notion of compensation that the claimant needs to establish that they have suffered loss or damage. Section 272(1)(a) provides for compensation for a particular kind of loss or damage, namely a reduction in the value of the goods. That s 272(1)(a) is dealing with a particular kind of loss or damage is apparent from s 272(3), which provides that s 272(1)(b) “does not apply to loss or damage suffered through a reduction in the value of the goods”; that is, loss or damage of the kind covered by s 272(1)(a).

98 The text and structure of s 272(1)(a) indicate that, at least generally, the point in time for assessing damages for any reduction in the value of the goods is the time of supply. The provision refers to a reduction in the value of the goods (resulting from the failure to comply with the consumer guarantee) below the lower of “the price paid or payable by the consumer for the goods” and “the average retail price of the goods at the time of supply”. Each of those integers is a price referable to the time of supply.

99 However, as already noted, the use of the word “damages” makes clear that the provision is concerned with compensation for loss or damage. It is necessary, therefore, for the Court to assess whether or not the applicant has suffered loss or damage (resulting from the failure to comply with the consumer guarantee). This may require, depending on the circumstances of the case, a departure from the time of supply or an adjustment to avoid over-compensation. We do not consider that the explicit and implicit references to the time of supply in s 272(1)(a)(i) and (ii) require the assessment of damages to be based on the time of supply in all cases. The overarching consideration is that the amount of compensation for any reduction in value be appropriate.

100 In that regard, we observe that the separate provision concerning reduction in value damages and the references to “price paid or payable” and “average retail price” were included to protect manufacturers. The evident purpose is to ensure that manufacturers do not have to compensate consumers for amounts paid by way of a higher retail margin to the supplier when compared to the average retail margin. Otherwise, s 272(1)(a) and (b) broadly reflect, as may be expected, the statutory rights of action to recover compensation or damages against the supplier of goods (if the failure to comply with a consumer guarantee cannot be remedied or is a major failure): see s 259(3)(b) and (4). In both instances, the statutory rights of action are to recover compensation or damages, that is, compensation for actual damage suffered. Therefore, the statutory language should not be seen as requiring an assessment as at the time of purchase irrespective of the particular circumstances (though in most cases that will be the appropriate approach). In the case of a claim against a manufacturer, assessment of reduction in value damages may still be undertaken by reference to the price paid (or the average retail price) at the time of supply, but taking into account subsequent events if considered appropriate. The references to the price paid or payable and the average retail price do not preclude such an approach. An assessment at a later time may be a more appropriate way to reflect the actual damage resulting from the value differential between the price paid (or average retail price) and the value of the goods.

101 Further, the authorities on statutory remedy provisions establish that it is wrong to approach such provisions by beginning with general law analogies (such as damages for breach of contract). For example, in Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 3; 216 CLR 388, in the context of remedies under Pt VI of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ stated at [44]: