Federal Court of Australia

Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 44

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD (ACN 000 095 607) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

The application for leave to appeal filed on 4 March 2022 be dismissed.

Unless the question of costs is agreed:

(a) within 14 days of the date of these orders, the parties file and serve written submissions on costs, limited to 3 pages;

(b) within a further 7 days, the parties file and serve any responding written submissions on costs limited to 2 pages; and

(c) the question of costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 145 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | ENERGY BEVERAGES LLC Applicant | |

AND: | CANTARELLA BROS PTY LTD (ACN 000 095 607) Respondent | |

order made by: | YATES, STEWART AND ROFE jJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 MARCH 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave to appeal be granted.

2. The draft notice of appeal filed with the applicant’s application for leave to appeal stand as the notice of appeal.

3. The appeal be allowed.

4. Orders 1 and 2 made on 18 February 2022 in proceeding NSD 1858 of 2019 be set aside.

5. Unless agreed:

(d) within 14 days of the date of these orders, the parties file and serve written submissions on the further orders to be made in this appeal (including as to costs), limited to 3 pages;

(e) within a further 7 days, the parties file and serve any responding written submissions limited to 2 pages; and

(f) subject to further order, the question of the further orders to be made (including as to costs) be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The applicant, Energy Beverages LLC (EB), applies for leave to appeal from judgments given on 18 February 2022 in respect of two appeals from decisions of delegates of the Registrar of Trade Marks in opposition proceedings. The appeals were heard in the original jurisdiction of the Court. They culminated in reasons for judgment of the primary judge published as: Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 113 (J).

2 In the first opposition, the respondent, Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (Cantarella), applied for the removal of Trade Mark No. 1345404 from the Register of Trade Marks on the ground of non-use under s 92(4)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act). The trade mark comprises the word “motherland” (the MOTHERLAND mark). It is registered in Class 32 for:

Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices.

3 EB is registered as the owner of the mark.

4 Cantarella’s case was that the mark should be removed because EB had not used it in the period 12 January 2016 to 12 January 2019 (the non-use period). The delegate was satisfied that the mark had not been used in that period, and directed that it be removed from the Register.

5 In the second opposition, EB opposed Cantarella’s application (Trade Mark Application No. 1819816) to register the word “mothersky” (the MOTHERSKY mark) for goods in Class 30 (coffee, coffee beans and chocolate) and services in Class 41 (coffee roasting and coffee grinding). Cantarella’s application originally included coffee beverages and chocolate beverages in Class 30, but it deleted these goods from its specification after EB filed its opposition. EB relied on the grounds provided by ss 44, 60 and 42(b) of the Act. The delegate was not satisfied that EB had established these grounds of opposition, and directed that the application proceed to registration.

6 EB appealed from each decision. The primary judge dismissed each appeal, with costs. We will refer to the appeals before the primary judge as, respectively, the MOTHERLAND appeal and the MOTHERSKY appeal. We will refer to the applications for leave to appeal before us as, respectively, the MOTHERLAND leave application and the MOTHERSKY leave application (together, the leave applications).

7 Except with leave, an appeal does not lie to the Full Court of this Court against a judgment or order of a single judge of the Court in the exercise of the Court’s jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from decisions or directions of the Registrar: s 195(2) of the Act.

8 On 4 March 2022, EB filed the MOTHERLAND leave application (NSD 144 of 2022) and the MOTHERSKY leave application (NSD 145 of 2022). Each application is supported by an affidavit made on 4 March 2022 by Miriam Zanker, the principal lawyer having conduct of the leave applications on behalf of EB.

9 On 23 May 2022, orders were made that the leave applications be heard together and be listed before a Full Court for hearing immediately prior to or concurrently with any appeals.

The Applications for leave to appeal

10 In Decor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1991) 33 FCR 397 at 398 – 399, the Full Court endorsed a litmus test for the granting of leave to appeal which has been applied consistently by this Court over many years. The test involves a two-stage inquiry: (a) whether, in all the circumstances, the decision below is attended with sufficient doubt to warrant it being considered by a Full Court; and (b) whether substantial injustice would result if leave were refused, supposing the decision to be wrong. The two inquiries bear upon each other.

11 The Full Court in Decor considered this approach to be appropriate for the general run of cases in which leave to appeal from an interlocutory decision is sought. The decisions in this case are not interlocutory decisions, but the approach in Decor remains appropriate, at least as a starting point for considering whether leave should be granted in respect of the present applications: see, for example, Primary Health Care Ltd v Commonwealth [2017] FCAFC 174; 260 FCR 359 at [206].

12 Applications for leave to appeal under s 195(2) of the Act (as well as applications for leave to appeal under s 158(2) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth)) from decisions in opposition proceedings arise in circumstances where there have already been two hearings involving the determination of facts—the opposition hearing before the Registrar’s delegate and the “appeal” before a judge of the Court. The nature of the “appeal” to this Court was described in Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks [2014] FCA 1304; 227 FCR 511 at [22] – [24] as follows:

22 Although styled an “appeal”, this proceeding involves the exercise of the original jurisdiction of the court: Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365 at [32]. The court is to determine judicially whether the application should succeed on its merits, not whether the Registrar has lawfully discharged her duties: Jafferjee v Scarlett (1937) 57 CLR 115 at 126.

23 What is required in that regard is a hearing de novo in which the court approaches the matter “afresh and without undue concern as to the ratio decidendi of the Registrar”: Rowntree PLC v Rollbits Pty Ltd (1988) 90 FLR 398 at 403. That said, weight should be given to the Registrar’s opinion as “a skilled and experienced person”: Jafferjee at 126. On some occasions, it has been said that “due weight” should be given to the Registrar’s opinion: Eclipse Sleep Products Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (1957) 99 CLR 300 at 308. On other occasions, it has been said that “great weight” (Eclipse at 321; Registrar of Trade Marks v Muller (1980) 144 CLR 37 at 41) or “very considerable importance” (Joseph Bancroft & Sons Company v Registrar of Trade Marks (1957) 99 CLR 453 at 457) should be given to the Registrar’s opinion.

24 I do not think that, by using these varying expressions, the cases intend to convey different notions of deference. Nevertheless, the degree to which weight should be given to the Registrar’s opinion will, no doubt, depend on the circumstances of each case and the particular question involved. For example, in the present case, both parties accepted that the weight to be given to the Registrar’s opinion may be affected by the fact that evidence has been adduced in the appeal which was not before the delegate.

13 So far as the MOTHERLAND leave application is concerned, EB has been unsuccessful in two contested hearings, where the facts have been fully examined, in establishing that MOTHERLAND was used as a trade mark in the relevant non-use period. This leave application is, in substance, an invitation to the Full Court to embark on yet a further examination of the facts to come to a finding contrary to the finding of the Registrar’s delegate and the finding of the primary judge. It has been said that, in such a case, it would be rare to grant leave to appeal in the absence of a clear prima facie case of error on the part of the primary judge: Woolworths Ltd v BP plc [2006] FCAFC 52; 150 FCR 134 at [54] – [55]; see, relatedly, Pfizer Corp v Commissioner of Patents [2006] FCAFC 190; 155 FCR 578 at [12].

14 For the reasons we express below, we are not persuaded that clear prima facie error on the part of the primary judge has been established. Indeed, we are satisfied that the primary judge was correct in concluding at J[25(b)] that EB had not demonstrated that it used the MOTHERLAND mark in relation to goods covered by its registration in the relevant non-use period. We therefore refuse the MOTHERLAND leave application.

15 So far as the MOTHERSKY leave application is concerned, EB has also been unsuccessful, in two contested hearings, in respect of its opposition to the registration of MOTHERSKY as a trade mark. We are persuaded, however, that EB has established clear prima facie error on the part of the primary judge insofar as its opposition is based on s 44(1) of the Act. Further, the error involves an issue which the Registrar’s delegate did not overtly consider or determine—namely, whether, for the purposes of s 44(1) of the Act, the goods for which the MOTHERSKY mark are sought to be registered in Class 30 are “similar” goods to the goods for which “blocking” marks were registered. For that reason, we will grant leave to appeal in the MOTHERSKY leave application and proceed to determine the appeal on the basis of the draft notice of appeal and the submissions that have been made.

The parties

EB

16 EB, through its wholly-owned subsidiary, Energy Beverages Australia Pty Ltd (EB Australia), supplies energy drinks under its MOTHER and MOTHER-derivative trade marks. It acquired the MOTHER brand in June 2015 from The Coca-Cola Company (TCCC).

17 In early 2007, TCCC launched the MOTHER energy drink in Australia. In December 2015, EB incorporated EB Australia to oversee the distribution of MOTHER energy drinks in Australia and to carry out marketing and promotion activities.

18 MOTHER energy drinks are distributed throughout Australia to various trade channels including supermarkets, retail chains (such as Target and Kmart), convenience stores and service stations, restaurants, bars and pubs, liquor outlets, vending machines, universities and TAFEs, cinemas, and foodservice and independent stores, such as food courts, general stores, bakeries and pharmacies. MOTHER energy drinks are also available on tap in some pubs in metropolitan cities.

19 The MOTHER brand is promoted by using the word MOTHER in conjunction with other words, for example: MOTHER BIG SHOT; MOTHER LEMON BITE; MOTHER LOW CARB; MOTHER FROSTY BERRY; MOTHER SUGAR FREE; MOTHER BIG CHILL; MOTHER GREEN STORM; MOTHER SURGE ORANGE; MOTHER REVIVE; MOTHER KICKED APPLE; MOTHER PASSION; MOTHER TROPICAL BLAST; and MOTHER EPIC SWELL.

20 In addition to product names, EB promotes the MOTHER brand using taglines and slogans, for example: MOTHER 100% NATURAL ENERGY; MOTHER: A FORCE OF NATURE; MOTHER OF AN ENERGY KICK; MOTHER OF AN ENERGY HIT; MOTHERLAND; MOTHERLAND IT’S A RUSH; MOTHER MAIDENS; MOTHER MADE ME DO IT; MOTHER SAYS …; and MOTHER OF A FESTIVAL.

21 The image that EB seeks to convey through its advertising, marketing, and promotional activities, is that the MOTHER energy drink is “a high-energy and rebellious product”, as illustrated by the following taglines which it adopts to emphasise the contents of its products that give energy to the consumer: HIGH CAFFEINE CONTENT; NATURAL CAFFEINE; ACAI: GUARANA: CAFFEINE: GINSENG; and LEMON LIME FLAVOUR WITH CAFFEINE, TEA & YERBA MATE.

22 Since 2007, the MOTHER brand has been the subject of extensive advertising, marketing and promotion. This has included television commercials, radio advertisements, sponsorship of events, print advertisements, point-of-sale material, outdoor advertising (such as on billboards, bus stops and on buses) and promotional campaigns (including partnerships, competitions and giveaways, often in association with radio broadcasters, popular websites or video games).

23 EB’s promotional strategy since 2015 is focused heavily on sponsorship, advertising by its website and other social media pages, in-store promotions, and point-of-sale materials.

24 EB’s MOTHER Facebook page has been in operation since 2008. As at May 2020, it had over 120,000 followers. The page is locally controlled in Australia.

25 EB’s MOTHER YouTube page was launched in 2008. The videos posted to this account regularly receive over 10,000 (and in some cases, 100,000) views.

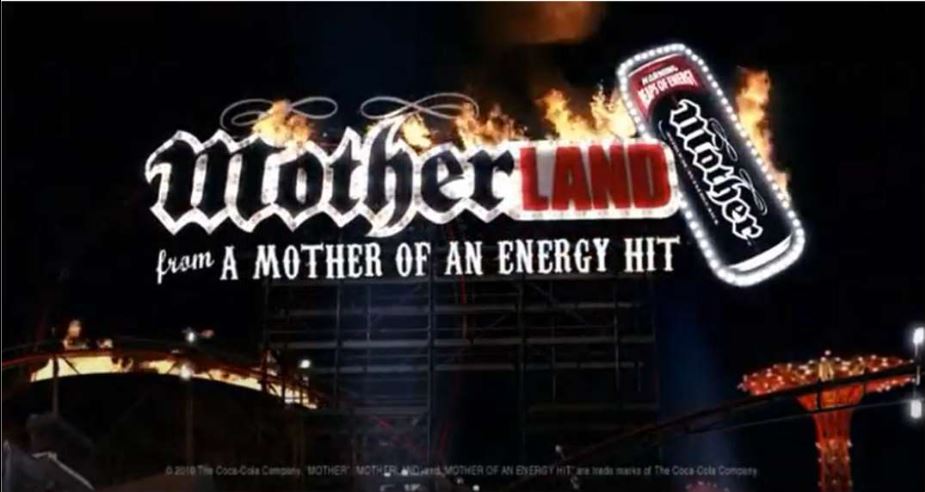

26 EB’s promotional activities have included the use of MOTHERLAND to refer to a fictional fantasyland tailored to MOTHER-drinking consumers. In 2010 and 2011, TCCC ran an advertising campaign (the MOTHERLAND campaign) which included the MOTHERLAND commercial. The commercial was broadcast in various iterations on free-to-air television. A version of the commercial was posted on the MOTHER YouTube and Facebook pages.

27 The MOTHERLAND campaign also involved other forms of advertising, including: print advertisements; online advertising on various websites; social media advertising, including numerous references to MOTHERLAND in posts and user comments on the MOTHER Facebook page, and in sponsored posts; downloadable “wallpapers”; point-of-sale material; and competitions and cross-promotions (including in partnership with 2DayFM and Triple M) to win $5000 and visit “Motherland”.

28 The following is a screenshot from the MOTHERLAND commercial:

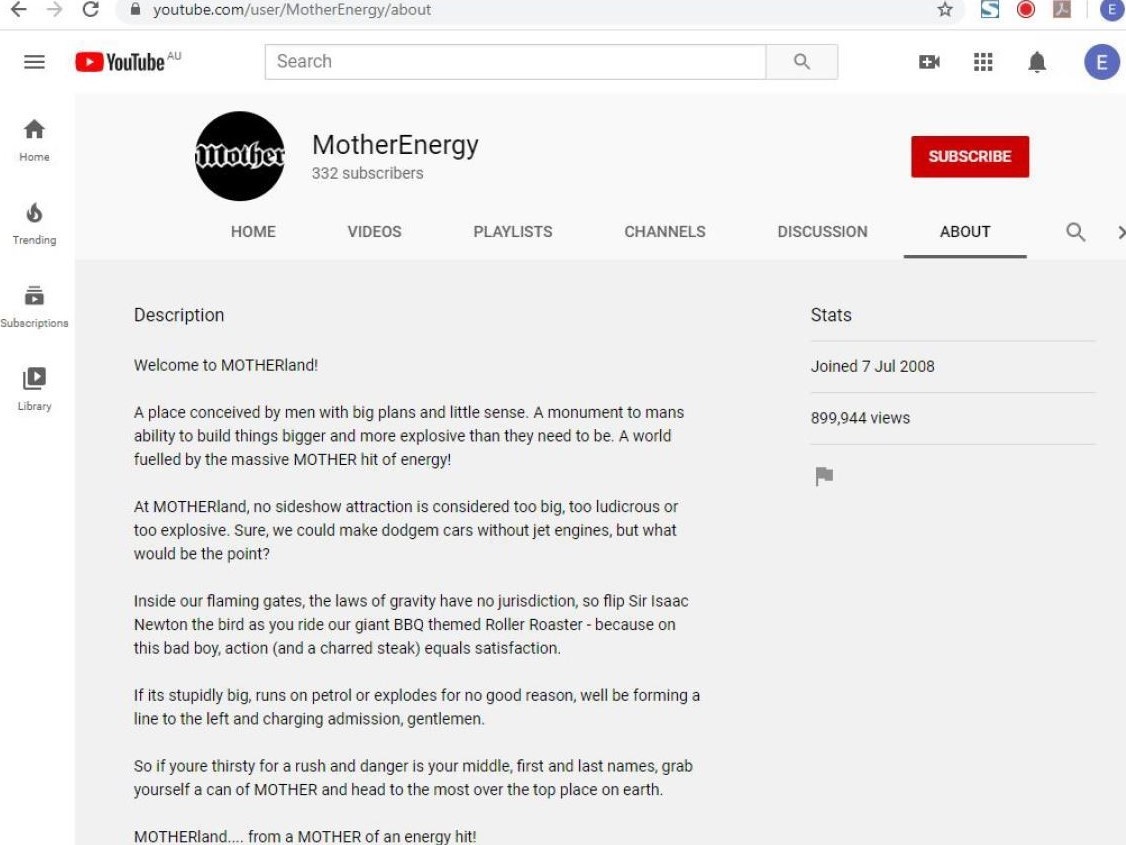

29 As at 11 March 2020, the phrase “Welcome to MOTHERland!” was in the description that appears in the “About” tab of the MOTHER YouTube page.

Cantarella

30 Cantarella is a supplier of so-called “pure coffee” in various forms in Australia under a number of brands. It sells its coffee to cafes and restaurants, major supermarket chains, and wholesale and retail grocery stores, among other establishments.

31 The Cantarella business was founded in 1947. Cantarella first began to import raw coffee beans into Australia in 1958 for the purpose of roasting, grinding and packaging coffee products sold under the trade mark VITTORIA.

32 The mark MOTHERSKY was suggested by two contractors who had been engaged by Cantarella to work on developing a boutique coffee brand with an Australian focus. One of the contractors was a member of a band that had a blog called “motherskyrecords” that showed posts as early as 2010. The band subsequently released a single under the “Mother Sky Records” label.

The MOTHERLAND leave application

The primary judge’s decision

33 Relevantly to the present application, s 92 of the Act provides:

(1) … a person may apply to the Registrar to have a trade mark that is or may be registered removed from the Register.

(2) The application:

(a) …;

(b) may be made in respect of any or all of the goods and/or services in respect of which the trade mark may be, or is, registered.

(3) ...

(4) An application under subsection (1) … (non-use application) may be made on either or both of the following grounds, and on no other grounds:

(a) …;

(b) that the trade mark has remained registered for a continuous period of 3 years ending one month before the day on which the non-use application is filed, and, at no time during that period, the person who was then the registered owner:

(i) used the trade mark in Australia; or

(ii) used the trade mark in good faith in Australia;

in relation to the goods and/or services to which the application relates.

(5) ...

34 In the MOTHERLAND appeal, EB contended that the MOTHERLAND mark had been used in the non-use period. It relied on: (a) the MOTHERLAND commercial posted on the MOTHER YouTube and Facebook pages; (b) the textual use of “Welcome to MOTHERland!” in the description that appears in the “About” tab of the MOTHER YouTube page; and (c) certain historical posts made by TCCC on the MOTHER Facebook page.

35 EB contended that the MOTHERLAND commercial was accessible for viewing on the MOTHER YouTube page in around May 2020 and on the MOTHER Facebook page in April 2021. It contended that it could be readily inferred that the commercial was also available throughout the non-use period.

36 EB contended that MOTHERLAND was used in the commercial as a trade mark in relation to the MOTHER energy drink, in the same way as MOTHER, itself, was used as a trade mark. Although MOTHERLAND describes the fictional theme park upon which the MOTHERLAND advertising campaign was based, EB contended that MOTHERLAND, as used in the commercial, also had a secondary brand association. Viewers would see the word MOTHERLAND as having the character of a MOTHER brand, indicating a connection in the course of trade between MOTHERLAND and MOTHER energy drinks.

37 The primary judge found that the MOTHERLAND commercial was, in the delegate’s words, “a passive historical snapshot of a marketing campaign” that EB was “no longer actively promoting or using to sell its goods to Australian consumers”. His Honour found that MOTHERLAND was used in the commercial to describe a fictional theme park, as part of a marketing strategy. His Honour was not satisfied that it was being used as a trade mark in relation to the registered goods. His Honour said that the construct of a MOTHERLAND theme park was being used to promote MOTHER-branded energy drinks, as manifested by the use of the word MOTHER rendered in distinct black gothic script and twirls, in contrast with the red script for LAND, juxtaposed with the can of Mother energy drink, as illustrated in the following depiction:

38 His Honour said (at J[203] – [204]):

203 Consistently with the reasoning of the High Court in Gallo at [69], the MOTHER mark is being used in the MOTHERLAND commercial as a badge of origin to distinguish the energy drinks of the owner, TCCC and then EB, from energy drinks produced by other manufacturers. The incorporation of the MOTHER mark, with its distinctive gothic script and twirls, in the word “Motherland” as depicted in the video emphasises that the MOTHER mark is being used as the trade mark in the video. There is no separate or additional use of the MOTHERLAND mark as a trade mark to distinguish MOTHER energy drinks from other energy drinks. The “Motherland” construct emphasises the adventurous and rebellious brand pillars of MOTHER energy drinks but the branding and badge of origin is firmly entrenched as the distinctive MOTHER mark.

204 On no view were TCCC and EB promoting the sale of tickets to a theme park called “Motherland” nor promoting the sale of any “Motherland” products by posting, and then not taking down, the MOTHERLAND commercial on social media websites.

39 The primary judge found that there were additional hurdles facing EB in establishing use of MOTHERLAND as a trade mark for the purposes of s 92(4)(b) of the Act.

40 First, the MOTHERLAND commercial had been uploaded to YouTube and Facebook in 2011, approximately five years before the commencement of the non-use period. The primary judge said that it was not apparent how the continued presence of the commercial on these platforms was, alone, sufficient to establish genuine, commercial use by EB many years after a concerted advertising campaign in 2011.

41 Secondly, the evidence did not disclose how a person could actually view the MOTHERLAND commercial on these platforms.

42 Having found that MOTHERLAND had not been used as a trade mark during the relevant non-use period, the primary judge considered whether the Court’s discretion should be exercised in favour of retaining its registration as a trade mark on the Register. The primary judge was not persuaded that EB’s contentions, in support of the mark remaining on the Register, were compelling or, indeed, persuasive.

EB’s submissions

43 Ground 1 of EB’s draft notice of appeal concerns the primary judge’s findings on whether MOTHERLAND had been used as a trade mark. This ground focuses on the primary judge’s finding that, in the MOTHERLAND commercial, MOTHERLAND was not being used as a trade mark in relation to energy drinks. It also raises the question of whether the primary judge erred by failing to consider, and to find, trade mark use of MOTHERLAND in posts on the MOTHER Facebook page (examples extracted below) and in text in the “About” tab on the MOTHER YouTube page (extracted below) (the social media posts).

44 All the posts on which EB relies in this regard were made well before the commencement of the non-use period.

45 As to this proposed ground, EB submits that the primary judge erred in finding that MOTHERLAND was not being used as a trade mark in relation to energy drinks in the MOTHERLAND commercial. EB submits that the primary judge’s reference at J[203] to “the MOTHER mark being used as the trade mark” indicates that he appears to have proceeded on the basis that only one trade mark at a time can be used in relation to particular goods. EB submits that the use of MOTHER in the MOTHERLAND commercial, as a trade mark in relation to energy drinks, does not mean that MOTHERLAND was not also being used as a trade mark in relation to those goods. EB submits that use as a trade mark in relation to goods for the purposes of s 17 does not require the mark to appear on the goods or packaging themselves. It submits that both marks were used as trade marks in relation to energy drinks.

46 EB submits that the primary judge was correct to find that the MOTHERLAND commercial was promoting MOTHER branded energy drinks (at J[202]) and in finding that the “Motherland” construct emphasised the adventurous and rebellious brand pillars of MOTHER energy drinks (at J[203]). EB submits that the primary judge was also correct to find that the MOTHERLAND commercial was not promoting the sale of tickets to a theme park called “Motherland” (at J[204]). EB submits that these findings compel a conclusion that MOTHERLAND was being used as a trade mark in relation to energy drinks. It was not descriptive of the goods being promoted. Rather, it was performing a branding function in addition to, and in combination with, MOTHER, such as to indicate a connection in the course of trade between the energy drinks being promoted, and the company providing them.

47 EB submits that the same findings should have been made by the primary judge in respect of the posts on the MOTHER Facebook page and the textual content on the MOTHER YouTube page.

48 Ground 2 of EB’s draft notice of appeal concerns the primary judge’s finding that MOTHERLAND had not been used as a trade mark during the non-use period.

49 As to this proposed ground, EB submits that the posting, in 2018, of an emoji (a smiley face) in response to the MOTHERLAND commercial hosted by the MOTHER Facebook page, and the posting, in the same year, of a comment on the MOTHER YouTube page in response to the MOTHERLAND commercial, shows that the MOTHERLAND content on Facebook and YouTube remained available, and was viewed, in the non-use period.

50 EB also submits that the evidence shows that, as at 30 March 2021, the MOTHERLAND commercial remained available to be viewed on the MOTHER YouTube and Facebook pages. In this connection, videos posted to a Facebook page or on YouTube remain unless they are removed or hidden by the user or the administrator. Further, the phrase “Welcome to MOTHERland!” in the description that appears in the “About” tab of the MOTHER YouTube page remained at least until 11 March 2020.

51 Thus, EB submits that MOTHERLAND was used online in relation to MOTHER branded energy drinks for the purpose of promoting those drinks and that these online uses remained available to be viewed and, in EB’s submission, were viewed in the non-use period, during which time MOTHER branded energy drinks were on the Australian market for sale. EB submits that these online uses of MOTHERLAND were ordinary and genuine uses of that trade mark in the course of trade. Moreover, EB contends that, even if no one had seen these online uses in the non-use period, there was still use of MOTHERLAND as a trade mark, as the online uses were targeted to an Australian audience and remained accessible during that period.

52 EB submits that the primary judge erred in finding that there was an absence of evidence as to how a person could view the MOTHERLAND commercial online. It submits that there was evidence before the primary judge to show that a viewer could navigate to the commercial. EB submits that, in any event, such evidence was not relevant. Obscurity as to the means of accessing the MOTHERLAND commercial and social media posts does not mean the trade mark use of MOTHERLAND has not been established.

53 EB submits that the primary judge erred in taking into account whether any viewing of the MOTHERLAND commercial was in the course of trade when, in its submission, the relevant conduct was “placing and maintaining the mark online”, which was done for the purpose of promoting commercially available goods. This use was, therefore, in the course of trade.

54 Ground 3 of EB’s draft notice of appeal concerns the primary judge’s discretion under s 101(3) of the Act not to remove MOTHERLAND from the Register for drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks and sports drinks (which it called “the protected goods”), on the basis that the protected goods are very similar to “energy drinks”.

55 In oral submissions, Ms Ryan KC noted that the exercise of discretion sought by EB on the proposed appeal to the Full Court was narrower than that sought in the MOTHERLAND appeal before the primary judge. She explained that Ground 3 is only enlivened if EB succeeds on Grounds 1 and 2, with the consequence that the registration of MOTHERLAND for energy drinks will remain on the Register. Given his findings as to non-use, the primary judge did not have to consider the narrower exercise of discretion under s 101(3) of the Act in the MOTHERLAND appeal.

56 As to this ground, EB submits that if it is successful in maintaining the registration of MOTHERLAND for energy drinks, the discretion should be exercised to maintain the registration for the protected goods as well. EB submits that the consideration whether to exercise the discretion would take into account matters at the time of hearing the appeal from the primary judge’s judgment, rather than at the priority date.

57 EB contends that the primary judge was correct to group carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, and sports drinks in the same category in terms of taste and flavour, and the manner of their presentation for sale and consumption. EB submits that any use of MOTHER and MOTHER-derivative marks in relation to these goods “would only point to EB” and that the use of a similar “MOTHER …” mark, by a third-party in relation to these goods, would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

58 EB submits that there is no evidence that the public would be deceived or confused if MOTHERLAND were to remain on the register in respect of the protected goods, and not merely for energy drinks. Thus, EB argues, the public interest favours the registration of MOTHERLAND in respect of these goods.

59 EB submits, further, that it is concerned to protect its reputation in MOTHER branded energy drinks, including from the use of MOTHER-derived marks. It submits that Cantarella’s interests will not be prejudiced if MOTHERLAND remains registered for these additional goods, if it remains registered for energy drinks in any event. EB submits that it has never abandoned MOTHERLAND as a trade mark and its intention to use that mark is supported by the new application for registration it has made.

Consideration

60 We are not persuaded that the primary judge erred in concluding that MOTHERLAND was not used as a trade mark in the MOTHERLAND commercial and social media posts. Nor are we persuaded that the primary judge erred in concluding that the MOTHERLAND commercial did not constitute actual trade mark use in the relevant non-use period.

61 The principles concerning trade mark use are well settled. The primary judge set out a summary of those principles at J[160] taken from the Full Court in Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v Nestlé Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117; 272 ALR 487 at [19]:

…

(1) Use as a trade mark is use of the mark as a “badge of origin”, a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else: Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 at [19] (Coca-Cola); E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 265 ALR 645 at [43] (Lion Nathan).

(2) A mark may contain descriptive elements but still be a “badge of origin”: Johnson & Johnson Aust Pty Ltd v Sterling Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (1991) 30 FCR 326 at 347–8; 101 ALR 700 at 723; 21 IPR 1 at 24 (Johnson & Johnson); Pepsico Australia Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Co Pty Ltd (1996) 135 ALR 192; 33 IPR 161; Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading GmbH (2001) 190 ALR 185; 54 IPR 344; [2001] FCA 1874 at [60] (Aldi Stores).

(3) The appropriate question to ask is whether the impugned words would appear to consumers as possessing the character of the brand: Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 422; [1963] ALR 634 at 636; 1B IPR 523 at 532 (Shell Co).

(4) The purpose and nature of the impugned use is the relevant inquiry in answering the question whether the use complained of is use “as a trade mark”: Johnson & Johnson at FCR 347; ALR 723; IPR 24 per Gummow J; Shell Co at CLR 422; ALR 636; IPR 532.

(5) Consideration of the totality of the packaging, including the way in which the words are displayed in relation to the goods and the existence of a label of a clear and dominant brand, are relevant in determining the purpose and nature (or “context”) of the impugned words: Johnson & Johnson at FCR 347; ALR 723; IPR 24; Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar (2002) 56 IPR 182; [2002] FCA 390 (Anheuser-Busch).

(6) In determining the nature and purpose of the impugned words, the court must ask what a person looking at the label would see and take from it: Anheuser-Busch at [186] and the authorities there cited.

…

62 As we have noted, EB submits that the primary judge erred at J[203] by holding that only one trade mark at a time can be used in relation to particular goods. This submission mischaracterises the primary judge’s conclusion. His Honour made no such finding. After careful consideration of the MOTHERLAND commercial, the primary judge concluded that the only sign being used as a badge of origin in the advertisement was the MOTHER mark. His reference to the MOTHER mark being used as “the trade mark” in the video is consistent with his conclusion and not demonstrative of any error.

63 Moreover, there is a clear indication in the primary judge’s reasons that he was aware that more than one mark may be used to indicate a connection in the course of trade. Principles (5) and (6) above, which the primary judge extracted from the Full Court’s summary in Nature’s Blend, are derived from Allsop J’s (as his Honour then was) reasons in Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar [2002] FCA 390; 56 IPR 182.

64 As Allsop J observed at [185] of Anheuser, in relation to the use of word marks on a label, the task in assessing whether a mark is used as a trade mark is to examine the way the marks are used in their context, including the totality of the packaging, to assess their nature and purpose in order to see whether they are used to distinguish the goods from the goods of others. The usage of a mark may fulfil more than one purpose. A mark may have a role in identifying a geographical location, and also a trade mark or branding or distinguishing role. It depends on context: Anheuser at [189].

65 The primary judge did not err in concluding that, in the context of the MOTHERLAND commercial, MOTHER is the only mark being used as a trade mark. MOTHERLAND is used in the commercial as the name of an invented or mythical place, a fictional theme park. Cantarella submitted, and we accept, that, as a place name, there is little difference between MOTHER “land”, and MOTHER “showroom”, “factory” or “playground”.

66 In the commercial, MOTHERLAND is displayed on a sign over the entry to the fictional theme park. Attached to the sign at the right hand side is a black can of MOTHER energy drink, with the gothic script MOTHER mark clearly displayed. People attending the fictional theme park are shown drinking from cans of MOTHER energy drink on which the gothic script MOTHER mark is displayed front and centre for the viewer.

67 The depiction of MOTHERLAND in the commercial with the prominent MOTHER in the well-known gothic script representation in contradistinction to LAND, appended in plain red font, emphasises the use of the distinctive gothic script MOTHER mark as the only mark possessing the character of a brand. MOTHERLAND was the name of the fictional theme park, and no more.

68 The presence of the dominant gothic script MOTHER mark each time MOTHERLAND appears in the commercial, including as the central part of the mark itself, is part of the context relevant to the assessment of the role of MOTHERLAND: Anheuser at [191]. The focus on the well-known gothic script MOTHER, including as part of MOTHERLAND, supports the conclusion that the gothic script MOTHER is the only mark being used to distinguish the MOTHER energy drinks in the commercial from the energy drinks of others.

69 EB sought to portray MOTHERLAND as a slogan, akin to the examples given by Bennett J at [16] in Unilever Australia Ltd v Societe Des Produits Nestlé SA [2006] FCA 782; 154 FCR 165: “Good on you mum Tip Top’s the one!”. This does not assist EB. First, “land” in MOTHERLAND is not a slogan. Second, there is no separate test or different treatment of slogans when considering whether there is trade mark usage: Unilever at [15].

70 The same conclusion can be made in relation to the use of MOTHERLAND in the social media posts. In each of the Facebook posts, MOTHERLAND is used as the name of a fictional theme park: for example, “Welcome to MOTHERLAND!”, “Did you know the ZOO Weekly girls crashed the filming of MotherLand?” or “What’s your favourite ride in MotherLand?”.

71 In the header of each of the Facebook posts there is a profile picture comprising a circle containing the distinctive MOTHER mark in gothic script on a red background, next to a reference to MOTHER ENERGY DRINK (the page name). Where there is a still from the MOTHERLAND commercial included in the posts, the gothic script MOTHER is prominent both in the MOTHERLAND heading but also in the can displayed next to the entry sign.

72 As with the commercial, there is no example of MOTHERLAND in the social media posts that is not closely associated with the well-known gothic script MOTHER mark.

73 Above the text on the YouTube “About” tab there is a profile picture comprising a black circle with the gothic script MOTHER outlined in white against the black background. Next to the circle is the account name “MotherEnergy”. The use of MOTHERLAND as the name of the fictional theme park continues here. “Welcome to MOTHERland!” introduces a description of the fictional theme park, which is described as being a “place conceived by men with big plans and little sense”. The world is said to be “fuelled by the massive MOTHER hit of energy”. The reader is told to “grab yourself a can of MOTHER and head to the most over the top place on earth”.

74 In none of the social media posts is MOTHERLAND being used as a trade mark to distinguish the MOTHER energy drinks from those of other traders. In each example that task is being performed by the well-known gothic script MOTHER mark alone.

75 As we agree with the primary judge’s conclusion that MOTHERLAND was not used as a trade mark in the MOTHERLAND commercial or social media posts, proposed Ground 2 in EB’s draft notice of appeal simply does not arise for consideration. This is because, as advanced in the present application, proposed Ground 2 relies on these uses of MOTHERLAND. Our resolution of proposed Ground 1 adversely to EB means that proposed Ground 2 fails at the outset.

76 There is, however, another fundamental difficulty with proposed Ground 2. Accepting that the commercial remained on the two sites in the non-use period, there was no evidence before the primary judge that any person, in Australia, accessed the commercial from those sites. Under existing authority, which has not been challenged in the present application, the mere uploading of trade mark content on a website outside Australia is not sufficient to constitute use of the trade mark in Australia: Ward Group Pty Ltd v Brodie & Stone plc [2005] FCA 471; 143 FCR 479; Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 664; 186 FCR 519; Christian v Societe Des Produits Nestle SA (No 2) [2015] FCAFC 153; 327 ALR 630. The fact that an emoji was posted on the Facebook page, and that a comment was made on the YouTube page, in the non-use period, does not address, still less answer, the fundamental question of whether there was trade mark use of MOTHERLAND in Australia in respect of the registered goods in the non-use period. The making of the post, and the comment, was evidence of no more than the continuing presence of the commercial on the respective sites—a matter on which the primary judge was satisfied in any event.

77 Both these obstacles to proposed Ground 2 succeeding are insurmountable. For this reason, we do not propose to address the subsidiary issues raised in the particulars to proposed Ground 2 and in EB’s submissions.

78 Further, given our conclusions on proposed Grounds 1 and 2, and EB’s concession referred to above, proposed Ground 3 in the draft notice of appeal is not enlivened.

The MOTHERSKY leave application

The primary judge’s decision

79 EB’s opposition to registration of the MOTHERSKY mark was based on three grounds.

80 First, EB contended that MOTHERSKY should not be registered on the basis of s 44(1) of the Act which provides:

(1) Subject to subsections (3) and (4), an application for the registration of a trade mark (applicant’s trade mark) in respect of goods (applicant’s goods) must be rejected if:

(a) the applicant's trade mark is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to:

(i) a trade mark registered by another person in respect of similar goods or closely related services; or

(ii) a trade mark whose registration in respect of similar goods or closely related services is being sought by another person; and

(b) the priority date for the registration of the applicant's trade mark in respect of the applicant's goods is not earlier than the priority date for the registration of the other trade mark in respect of the similar goods or closely related services.

Note 1: For deceptively similar see section 10.

Note 2: For similar goods see subsection 14(1).

Note 3: For priority date see section 12.

Note 4: The regulations may provide that an application must also be rejected if the trade mark is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, a protected international trade mark or a trade mark for which there is a request to extend international registration to Australia: see Part 17A.

81 EB contended that MOTHERSKY was deceptively similar to its earlier registered marks MOTHER (Trade Mark Nos. 1230388 (the 388 mark) and 1364858 (the 858 mark)), MOTHERLAND, and MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE (Trade Mark No. 1408011 (the 011 mark)). In the present appeal, EB does not contend that the primary judge erred in the conclusion he reached on the application of s 44(1) taking into account the 858 mark. It also does not contest the findings that the primary judge made in respect of the 011 mark. Its appeal is limited to a comparison between MOTHERSKY, and the 388 mark (MOTHER) and the MOTHERLAND mark. The 388 mark is registered for the following goods in Class 32:

Non-alcoholic beverages; drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; fruit drinks and juices; syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages including syrups, concentrates and powders for making mineral and aerated waters, carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, sports drinks, fruit drinks and juices.

82 This is the same as the specification for the MOTHERLAND registration.

83 The primary judge found that the goods covered by Cantarella’s application for registration of MOTHERSKY (coffee, coffee beans and chocolate), which was made on 11 January 2017 (the MOTHERSKY application) and the goods covered by the cited registrations, were not “similar goods” for the purposes of s 44(1). In this connection, s 14(1) of the Act provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, goods are similar to other goods:

(a) if they are the same as the other goods; or

(b) if they are of the same description as that of the other goods.

84 The primary judge treated the question before him as whether the goods of the MOTHERSKY application and the goods of the cited registrations were goods “of the same description”, having regard to the principles of trade mark law. So far as the 388 mark and the MOTHERLAND mark are concerned, the primary judge focused on “carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks” and “non-alcoholic beverages”, and the syrups, concentrates and powders for making them. His Honour referred to these as the first category goods. His Honour also identified a second category of goods, but his Honour’s analysis in respect of these goods is not relevant to EB’s proposed appeal.

85 As to the first category goods, the primary judge found that, at a significant level of abstraction, these goods and, at least, “coffee”, could both be characterised as “non-alcoholic beverages”. However, his Honour reasoned that this characterisation ignored the fundamentally different taste and flavour of carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks, the manner in which they are presented for sale and consumed, and the differences in form, function and origin between syrups, concentrates and powders, and coffee beans, ground coffee and coffee in capsule form. The primary judge did not accept that the evidence directed at distribution channels and to the extension by Cantarella and its competitors of their “coffee” marks to other products was determinative.

86 As to the question of trade mark comparison, the primary judge found that the impression hypothetically recalled of the cited registrations was not sufficient to give rise to a resemblance between MOTHERSKY and those marks, such as would be likely to deceive or cause confusion. The primary judge, at J[320] – [330], gave detailed reasons for coming to that conclusion.

87 The primary judge found that there were material visual and aural differences between MOTHERSKY and the cited marks, as well as differences in what the marks connote.

88 The primary judge reasoned that the word “mother” was retained in the registration of MOTHER as an established and well-known word. On the other hand, MOTHERSKY was not an established and well-known word.

89 The primary judge reasoned that the differences between MOTHERSKY and the cited marks were more pronounced than other marks that have been found to be deceptively similar, notwithstanding that the differences between them would be readily apparent to a consumer.

90 The primary judge was satisfied that the overwhelming emphasis and impression conveyed by the cited marks was on the word “mother” as a single, easily recognisable word with an established meaning. The primary judge found that, unlike the cited marks, MOTHERSKY comprises a single invented word, where “mother” is absorbed within the mark and the emphasis, and impression conveyed, is not on the word “mother”.

91 The primary judge found that, for each of the cited marks, the emphasis, aurally, was on “mother”, whereas for MOTHERSKY the emphasis was more on the second syllable. The primary judge found, further, that MOTHERSKY did not exhibit a strong phonetic similarity with the cited marks, such that consumers of ordinary memory and intelligence, with an imperfect recollection, might consider the marks to be related.

92 The primary judge found that the word “mother” is a commonly used word. When it is combined with other words that are descriptive of services or goods, it conveys distinct and different meanings. For example, the addition of the words “loaded iced coffee” in the MOTHER LOADED ICED COFFEE mark acted as a qualifier or variant to “mother”, and described a specific type of product. However, the primary judge did not think that the addition of “sky” in MOTHERSKY acted as a qualifier or variant to “mother”. MOTHERSKY did not describe a specific type of product or bear any relationship, in his Honour’s view, to the other MOTHER-derivatives in EB’s stable of trade marks.

93 Further, the primary judge did not accept that there were any “obvious conceptual synergies” between MOTHERLAND and MOTHERSKY. The primary judge reasoned that MOTHERLAND evokes an impression of a native country or homeland, neither of which meanings are conveyed by MOTHERSKY. MOTHERSKY was a highly distinctive novel word with no established meaning.

94 Before the primary judge, EB also based its opposition on the grounds provided by ss 42(b) and 60 of the Act – the second and third of the three grounds referred to. In the present application, EB does not seek to challenge the primary judge’s adverse finding in relation to the application of s 42(b). However, EB does contend that the primary judge erred in his findings in relation to the application of the ground under s 60.

95 Section 60 of the Act provides:

The registration of a trade mark in respect of particular goods or services may be opposed on the ground that:

(a) another trade mark had, before the priority date for the registration of the first-mentioned trade mark in respect of those goods or services, acquired a reputation in Australia; and

(b) because of the reputation of that other trade mark, the use of the first-mentioned trade mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

Note: For priority date see section 12.

96 Earlier in his reasons, the primary judge gave detailed consideration to the evidence before him, and reached a number of broad conclusions. At J[146] – [148], the primary judge said:

146 As explained above, EB approached the market issue by seeking to establish the existence of what it described as a “material interface” between first, energy drinks and other products, including coffee, and second, between “pure coffee” and other products.

147 The effect of this approach was to introduce into the evaluation a very broad range of beverage products that sat between the MOTHER energy drinks sold by EB and the MOTHERSKY pure coffee products sold by Cantarella. These products included RTD beverages such as iced coffee, iced tea and cold brew coffee products sold in cans. The introduction of these “intermediate products” ultimately had a tendency to distract from, rather than assist in, the determination of the likelihood of deception or confusion and the extent of the reputation that EB had established in its MOTHER marks.

148 At times in the course of its submissions Cantarella sought to distinguish between “pure coffee” and “instant coffee”, but the principal distinction drawn by Cantarella and the subject of the most attention by the parties was the distinction between “pure coffee” and what might be described as “coffee flavoured milk” and other coffee flavoured RTD beverages. EB’s expansive taxonomical approach was to include such RTD products within the concept of coffee.

97 The primary judge found that the evidence before him provided only limited support for the “material interface” for which EB contended.

98 In this connection, the primary judge found, firstly, that the need for product innovation to remain competitive in the energy drink market could not itself give rise to an expectation on the part of consumers that EB could be expected to diversify its product offering to include MOTHER coffee beans and ground coffee. Rather, consumers could expect diversification in the presentation, packaging and flavour of energy drinks, rather than a diversification into products outside the ready-to-drink (RTD) range of product offerings.

99 The primary judge found, secondly, that the evidence relied upon by EB to establish that energy drink companies considered coffee drink companies to be direct competitors included certain SEC filings. However, those findings did not suggest that energy drink companies identified their competitors as extending to pure coffee suppliers. Further, the primary judge cautioned that the competitive landscape in Australia cannot be assumed to be materially the same as in the United States of America.

100 At J[156] – [157], the primary judge said:

156 I address below the specific market and reputational issues raised by EB and Cantarella in the course of addressing the matters relied upon by EB in these appeals. In summary, for the reasons that I develop below in the course of addressing the matters relied upon by EB in these appeals, I am not satisfied that energy drink companies “often” position themselves as a direct alternative to coffee. Nor am I satisfied that the fact that some coffee beverage manufacturers, other than Cantarella, may file for trade mark coverage for “energy drinks” is of any particular significance to the question of whether the use of the MOTHERSKY mark by Cantarella is likely to lead to consumers being deceived or confused.

157 It is sufficient to make the following general observations at this point. First, I am satisfied that the markets for coffee and RTD products, such as iced coffee, iced tea and cold brewed coffee sold in cans, are different. Second, I am not persuaded that there is any material interface between energy drinks and coffee or significant overlap between the marketing and sale of energy drinks and coffee. Third, I am not satisfied that the evidence adduced in the appeals establishes that the market in which energy drinks is supplied, at least in Australia, extends to other RTD products such as iced coffee, iced tea and cold brewed coffee sold in cans.

101 For the purposes of s 60 of the Act, the primary judge accepted Cantarella’s contention that EB’s reputation in the MOTHER mark was “deep but narrowly focused”.

102 Based on the evidence before him, the primary judge also accepted the delegate’s summation that:

[T]he evidence only shows use on energy drinks; this is not a situation where the Opponent uses its trade marks (or parts of the trade marks) on other beverages or foodstuffs which might induce a consumer into believing that the Opponent has expanded into chocolate or coffee. The strength of the Opponent’s reputation in the Mother Trade Marks in relation to energy drinks reduces the likelihood of confusion or deception from the use of the Trade Mark on, or in relation to, the Applicant’s Goods and Services to something less than ‘real and tangible’.

103 The primary judge made a number of findings in relation to the reputation in MOTHER as a trade mark, and the likelihood of deception or confusion resulting from potential use of the MOTHERSKY mark:

(a) The primary judge accepted that EB’s MOTHER mark had acquired an extensive reputation in Australia in relation to energy drinks at the priority date of the MOTHERSKY application.

(b) The primary judge did not accept that any similarities between prompts and taglines used in relation to energy drinks by EB and coffee companies in promoting or marketing their products would give rise to any real or tangible danger of confusion. As to this the primary judge said at J[353]:

At a general level, both energy drinks and coffee might be thought to be stimulants. Energy drinks may typically contain at least some quantity of caffeine; coffee may, at times, be marketed as some form of “wake up” or “pick up”; and both may be sold through the same distribution channels. However, caffeine cannot simply be equated with coffee and references to the presence of caffeine in both coffee and energy drinks cannot in my view give rise to any real or tangible danger of confusion in the minds of consumers.

(c) The primary judge found that EB’s reputation included the use of MOTHER in combination with other words, taglines and slogans, but only in the context of the sale of energy drinks. The sublines or variants of the original MOTHER branded energy drink served to differentiate flavours and perceived attributes of those drinks, but in each case the word MOTHER remained a prominent brand and was used without any prefix or suffix.

(d) The depiction of the MOTHER mark with its stylised gothic print on EB’s energy drinks and in its promotional and advertising material was fundamental to the use of the MOTHER mark as a trade mark.

(e) To the extent that Cantarella and other coffee companies had expanded the use of their brands to products other than coffee, these products did not give rise to the likelihood of deception or confusion because they were different products in different markets. EB’s reputation in the MOTHER brand was one acquired exclusively for energy drinks. EB had not sought to expand the use of MOTHER to products other than energy drinks.

(f) MOTHERSKY shares the element “mother” but only as part of a composite invented word with no established meaning. Although the notional use of that mark would include ways in which the “mother” element is emphasised, the primary judge was not satisfied that there was any reasonable basis for that concern. To date, Cantarella had not done so and the primary judge was satisfied that there would be no commercial rationale for it to do so.

(g) The primary judge recognised that any assessment of the notional use of MOTHERSKY as a trade mark must take into account the full range of use in relation to “coffee”. The primary judge concluded, however, that there was a fundamental distinction between “coffee” and “energy drinks” that is not materially diminished by the existence of RTD and pre-packaged coffee beverages such as iced coffee, cold brew coffee, and “coffee-in-a-can” products.

(h) The primary judge found that the sale of energy drinks and coffee being sold through common distribution channels was of little probative value. Supermarkets, retail outlets and convenience stores offer a broad range of products for sale to consumers. The more relevant enquiry was how the products are displayed for sale, their brand image, the means by which they are promoted and advertised for sale, and to whom they are marketed. The primary judge found on the evidence before him that coffee and energy drinks are displayed for sale in different ways and generally in different areas of supermarkets and convenience stores.

(i) The primary judge found that the marketing and promotion of energy drinks and coffee is fundamentally different. They have different brand images and are promoted and marketed to different classes of consumers in different ways.

(j) The primary judge found that the extent of EB’s success in creating such a powerful reputation in the MOTHER marks in connection with energy drinks reduces the likelihood of confusion or deception from the use of the MOTHERSKY mark in relation to Cantarella’s goods and services to something less than real or tangible.

104 For these reasons, the primary judge was not satisfied that EB had established that the use of the MOTHERSKY mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion due to the reputation of the MOTHER marks.

EB’s submissions

105 Ground 1 of EB’s notice of appeal is directed to the “blocking” effect of the 388 mark and the MOTHERLAND mark at the priority date of the MOTHERSKY application and, in particular, whether the primary judge erred in failing to find that, at that date, the goods covered by the registration of the 388 mark and the MOTHERLAND mark were “similar goods” as “coffee”. As we have noted, the MOTHERSKY application included goods in Class 30, being “coffee, coffee beans and chocolate”. As we have also noted, the description of the goods in the specifications of the 388 mark includes “Non-alcoholic beverages; … carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks; …”. Because we have concluded that leave to appeal in the MOTHERLAND leave application with respect to the removal of the MOTHERLAND mark from the register should be refused, it is only necessary for us to consider the specification of the 388 mark in dealing with this ground: see [174] – [177] below. We will refer to the registration of the 388 mark as the “blocking” registration.

106 A finding in favour of EB on this ground of appeal is not sufficient to make out EB’s opposition to registration of the MOTHERSKY mark under s 44(1) of the Act. In light of the way in which this appeal to the Full Court was conducted, opposition on that ground can only succeed if EB also succeeds on Ground 2 of its appeal, which challenges the primary judge’s finding that MOTHERSKY is not deceptively similar to MOTHER.

107 As to Ground 1, EB submits that, having found that coffee is a non-alcoholic beverage, the primary judge should have found that “coffee” in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application is a similar good to the “non-alcoholic beverages” covered by the specification of the “blocking” registration. This, EB contends, is enough to dispose of this ground of appeal in its favour. However, EB goes further to challenge other aspects of the primary judge’s reasoning on this question.

108 The primary judge construed the reference to “coffee” in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application as meaning coffee in the form of coffee beans, ground coffee, and coffee in capsule form for grinding, roasting or brewing to produce a cup of coffee for consumption (which, in the evidence, Cantarella referred to as “pure coffee”): J[310]. The primary judge also treated “coffee” in the specification as covering the resultant beverage (see at J[314]) even though, as we have noted, Cantarella deleted “coffee beverages” (as well as “chocolate beverages”) from the specification of the MOTHERSKY application after EB filed its opposition.

109 In the course of oral address in the present application, lead counsel for Cantarella, Mr Bannon SC, said that the parties proceeded below on the basis that, in the specification, “coffee” meant “coffee in its input form and coffee when made into a beverage, which fits the description of coffee”. This submission begs the question of what beverage “fits the description of coffee”? The primary judge construed the specification as including “coffee” as a beverage, although he did not treat the reference to “coffee” as extending to coffee beverages in a RTD form, such as iced coffee and cold-brewed coffee sold in cans and bottles—products which the primary judge described as “intermediate products”: see J[147].

110 EB does not challenge the construction of “coffee” in the MOTHERSKY application as including “coffee” as a beverage. However, it contends that, in undertaking his analysis of this question, the primary judge should have treated “coffee”, as a beverage, in all its RTD forms.

111 EB also draws attention to the more specific goods for which the 388 mark is registered—namely, “drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters”, and (as did the primary judge in his first category goods) “carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks”, all of which EB described as “a sub-set of non-alcoholic beverages”.

112 EB submits that the primary judge had an “improperly narrow view” of the nature of “coffee” in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application which distorted his Honour’s consideration of “uses” and “trade channels” when considering whether the goods in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application were “similar” goods to the goods for which the 388 mark was registered. EB submits that this error appears to have been caused because, in his analysis, the primary judge focused on the actual use of the various marks, not their notional use (as his Honour was required to do). EB submits that the primary judge should have considered the “full spectrum of coffee”—from pure coffee to pre-packaged RTD cold-brewed coffee and iced coffee. EB submits that, from this viewpoint, “coffee” and “non-alcoholic beverages”, and “coffee” and “drinking waters, flavoured waters, mineral and aerated waters; carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks”, are “similar goods” within the meaning of s 44(1) of the Act.

113 As we have foreshadowed, Ground 2 of the appeal is directed to the issue of trade mark comparison and whether, as a trade mark in respect of the nominated goods, MOTHERSKY is deceptively similar to MOTHER.

114 As to this ground, EB contends that the primary judge’s assessment of the question of deceptive similarity was coloured by his findings in respect of the (lack of) similarity between the goods of the MOTHERSKY application and the goods covered by the “blocking” registration—it being recalled that the primary judge was not satisfied that the goods claimed as “coffee” in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application were the same as, or of the same description as, the goods of the “blocking” registration.

115 EB also contends that the primary judge erred by failing to have regard, or at least failing to have sufficient regard, to the principle that the test for deceptive similarity concerns confusion as to the source of goods, not whether the goods themselves might be confused.

116 EB contends further that the primary judge failed to have regard to the essential features of the 388 mark (MOTHER), and otherwise erred in various respects in carrying out his trade mark comparison, including by misapplying the doctrine of imperfect recollection by considering, at J[319], the hypothetical recollection of MOTHERSKY as a mark.

117 EB also argues that the primary judge erred by taking into account the manner in which Cantarella had actually used the MOTHERSKY mark to reach the conclusion, at J[330], that there was no basis for concern that, at some time in the future, Cantarella might seek to place emphasis on the “mother” component of MOTHERSKY.

118 Ground 3 of the appeal is also directed to the issue of trade mark comparison—specifically whether, as a trade mark in respect of the nominated goods, MOTHERSKY is deceptively similar to MOTHERLAND. However, once again, because we have concluded that leave to appeal in the MOTHERLAND leave application should be refused, it is not necessary for us to summarise EB’s submissions with respect to this ground.

119 Ground 4 of the appeal concerns s 60 of the Act, which provides that the registration of a trade mark (here, MOTHERSKY) in respect of particular goods or services (here, “coffee”, which includes “coffee” beverages) may be opposed because of the reputation acquired by another mark (here, MOTHER) before the priority date of the opposed mark.

120 EB submits that the prior reputation of the other mark need not be specific to the goods or services for which the opposed mark is sought to be registered. Further, the use to which s 60 is directed is the notional use of the opposed mark in light of the prior reputation of the other mark: Qantas Airways Ltd v Edwards [2016] FCA 729; 338 ALR 134 at [143] and [178]. Plainly, having regard to the construction of “coffee” adopted by the parties, the notional use of the MOTHERSKY mark includes its use in respect of “coffee” beverages.

121 EB submits that the evidence establishes that, by January 2017, coffee- and tea-flavoured energy drinks were available in Australia, the energy drink trade mark “V” had been used for an iced coffee beverage since 2010, and “pure coffee” brands had begun to sell RTD iced coffee and cold pressed coffee in bottles and cans (for example, the Campos Coffee “Iced Latte” and “Dark City Cold Press” coffee products). EB specifically submits that the evidence establishes that energy drink companies were positioning their products as a direct alternative to coffee, and coffee companies were “spruiking” the stimulant function of caffeine and promoting RTD beverages with similar themes and slogans to energy drink companies.

122 EB directs attention to the primary judge’s finding (at J[350]) that EB’s reputation in MOTHER was “deep but narrowly focussed”. It submits that, in reaching this finding, the primary judge did not account for aspects of EB’s reputation as illuminated by the market circumstances referred to above. EB also points to its reputation for innovation, the combining of MOTHER with other words and taglines, the association of MOTHER with caffeine, the marking of MOTHER’s stimulant function, and the marketing of the “mother” concept independently of the gothic script logo version.

123 EB submits that, when these aspects of the MOTHER mark’s reputation are properly given context in the beverage market, “there is a clear risk that consumers confronted with an RTD coffee-in-a-can product under the MOTHERSKY … trade mark might have cause to wonder whether it emanated from EB”.

124 EB submits that the primary judge’s approach to s 60 of the Act was “constrained by his concentration on the ‘pure coffee’ market”, which did not factor in the full range of “coffee” when considering the question of notional use.

Consideration

Ground 1

125 Ground 1 of the appeal raises the threshold question of whether s 44(1) of the Act applies as a ground of opposition because the goods of the MOTHERSKY application are “similar goods” to the goods covered by the “blocking” registration. In order to answer this question, it is necessary to construe the specification of the MOTHERSKY application and the specification of the “blocking” registration.

126 As noted above, both parties advance a construction of “coffee” in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application that includes “coffee” as a beverage. They disagree, however, on what “coffee”, as a beverage, encompasses.

127 There is a real question as to whether “coffee”, as used in the MOTHERSKY application, means or includes “coffee” as a beverage. Nevertheless, Cantarella was content to deal with this ground of opposition as if it did. We will proceed accordingly.

128 If, in the specification of the MOTHERSKY application, the word “coffee” means or includes “coffee” as a beverage—as distinct from the plant-based product that is “coffee”, or roasted coffee that is supplied in bean or ground form (which Cantarella described in its evidence as “pure coffee”)—there is nothing in the specification, so construed, which would limit the meaning of “coffee” to any particular coffee beverage or to any particular kind or type of coffee beverage. For example, there is nothing to limit “coffee” to black coffee as opposed to white coffee or coffee made with milk. There is nothing to limit “coffee” to coffee that does not include some additive such as, for example, a flavoured syrup. Further, there is nothing to limit “coffee” to a hot beverage or a freshly-brewed beverage as opposed to a cold or iced beverage. Further still, there is nothing to limit “coffee” to coffee produced by a particular process or prepared in a particular way, or to coffee packaged and promoted in a particular way. There are many permutations of what constitutes “coffee” as a beverage. Thus, coffee beverages cover a range of goods.

129 In oral address, Cantarella adhered to its position that “coffee” in the MOTHERSKY application includes coffee beverages, although it did not accept that “coffee” would include coffee flavoured milk. There may well be a penumbra of uncertainty as to when a coffee flavoured beverage is not “coffee”. But, in order to determine Ground 1 (and, indeed, Ground 2 of this appeal), it is not necessary to explore the outer limits of what constitutes “coffee” as a beverage.

130 As to the specification of the “blocking” registration, it is convenient to focus on the broadest claim that is made—namely, to “non-alcoholic beverages”. This claim is very broad indeed. It is a standalone claim whose construction is not limited to the more particular descriptions of goods for which registration was sought. These more particular descriptions are for specific types of non-alcoholic beverages and also for goods that are not “non-alcoholic beverages” but syrups, concentrates and powders for making beverages, including syrups, concentrates and powders for making specific beverages. The claim to “non-alcoholic beverages” is not limited to particular non-alcoholic beverages or to particular types or kinds of non-alcoholic beverages. The only qualification is that the beverages be “non-alcoholic”.

131 “Coffee” as a beverage, without alcohol, is a non-alcoholic beverage. But Cantarella contends that coffee beverages are not Class 32 goods (the class for non-alcoholic beverages)—thereby suggesting that “coffee” as a beverage cannot be included in the scope of the “blocking” registration, where all the goods relevant to this ground of appeal have been nominated in Class 32.

132 Although for administrative purposes coffee beverages fall to Class 30, it does not follow that a claim to “non-alcoholic beverages” nominated in Class 32 in the specification of the “blocking” registration cannot, as a matter of description, include coffee beverages where such goods are part of a single, broad claim to all non-alcoholic beverages. In any event, the classification of goods and services according to classes is primarily a matter of convenience in administration (for example, in facilitating searches). The nomination of a class for particular goods is not decisive as to the scope of a given registration: Re Australian Wine Importers Ltd (1889) 41 Ch D 278 at 291; Reckitt & Coleman (Australia) Ltd v Boden [1945] HCA 12; 70 CLR 84 at 90; Nikken Wellness Pty Ltd v van Voorst [2003] FCA 816 at [43] – [44]. The question is whether, from a business and commercial point of view, the description “non-alcoholic beverages”, as used in the specification of the “blocking” registration, would be understood as including non-alcoholic coffee beverages. Appreciating the possible permutations discussed above, “coffee” as a beverage would be understood as being a good that falls within the description “non-alcoholic beverages”.

133 It is at this point that the specification of the MOTHERSKY application intersects with the specification of the “blocking” registration to claim the same goods. Cantarella submits that EB did not contend before the primary judge that non-alcoholic beverages and “coffee” as a beverage are the same goods. But EB’s written submissions below referred to the evidence as establishing “significant overlap” between “coffee” in the MOTHERKSY application and “non-alcoholic beverages” and, in oral submissions, the point was put directly that the description “non-alcoholic beverages” “cover[s] most coffee and chocolate beverages, and also for energy drinks”. Plainly, at J[314], the primary judge did consider whether “coffee” as a beverage is a “non-alcoholic beverage”. In doing so, his Honour impliedly rejected the proposition that “coffee” as a beverage is the same good as a “non-alcoholic beverage” for the purposes of this ground of opposition.

134 The primary judge did not elucidate his understanding of “coffee” as a beverage at J[314] beyond expressing the conclusion that “coffee” could be distinguished from carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks by the “fundamentally different taste and flavour” of carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks and sports drinks, and the manner in which those goods are presented for sale and consumed. This indicates that his Honour had a somewhat confined view as to what “coffee”, as a beverage, comprises, in a trade sense.

135 There was a significant body of evidence adduced by the parties that was directed to the trade channels for, and the promotion and supply of, so-called “pure coffee”, and the trade channels for, and the promotion and supply of, coffee beverages, energy drinks, sports drinks, and other non-alcoholic beverages. Much of the evidence adduced by EB related to products that were observed on supermarket shelves or were promoted by websites or social media platforms after the priority date of the MOTHERSKY application (11 January 2017). It is important to note this fact because Cantarella’s entitlement to registration of MOTHERSKY as a trade mark on the basis of the MOTHERSKY application must be determined as at the priority date. Even so, the evidence shows that there were a number of coffee beverage products being promoted and supplied in Australia well before the priority date.

136 For example, Food & Beverage magazine for 6 June 2008 included an article entitled “Non-Alcoholic Beverages Award Finalists”. The article identified the finalists as: “Bickford’s Ice Tea Cordials”; “Bickford’s Milkshake Mixes”; “Ice Break Loaded”; “Mandailing Estate single origin coffee and Mandailing Estate Kopi Luwak”; “Mango, Peach & More Nudie Crushie”; and “Pauls All Natural and Phoenix Organic Drinks Range”. The range of products is as noteworthy as is their description as “Non-Alcoholic Beverages”.

137 In the magazine, the “Ice Break Loaded” product is described as:

A line extension to the successful Ice Break brand that taps directly into the ‘energy’ component inherent in the brand’s current framework. This real iced coffee with a hit of guarana provides consumers with an energy drink option that can be easily consumed in the morning to provide an immediate energy boost, sustained increase in energy levels and a full feeling in the stomach to get through to the next meal.

138 There was evidence before the primary judge of the “Ice Break” coffee products (to which the above quote refers) that were promoted in Australia before the priority date of the MOTHERSKY application. For example, the Ice Break website as at 4 October 2016 depicted two varieties of the product: “Regular Strength” and “Extra Shot”. Both varieties were described on the webpage as “Real Coffee” and were compared with “other” coffee.

139 At that time, the website also referred to a product described as “Ice Break Refuel”:

Refuel with a coffee kick to the face. Ice Break Refuel has the coffee kick that will get you up & a protein punch to keep you going!

140 The inclusion of the Mandailing coffee products as one of the “Non-Alcoholic Beverages Award Finalists” in Food & Beverage magazine is particularly important because it evidences a clear trade connection between (in Cantarella’s parlance) “pure coffee” and non-alcoholic beverages. The Mandailing coffee products were described in the article in Food & Beverage magazine in these terms:

The Estate coffee is grown from 170 year old trees which are found in the depths of the Sumatran jungle. The trees are extremely low-yielding, and are some of the last remains of the original Dutch plantations which were ground by the Dutch East Indies trading (sic) Company in Sumatra. The Kopi Luwak is the unique coffee which is made from the skat of the civet cat. These coffee beans are the rarest in the world and the coffee is the most perfectly processed and smoothest-tasting coffee on earth.

141 The “V” Iced Coffee Double Espresso + Guarana Energy product was promoted in Australia from at least 2010 alongside the range of “V” Energy Drinks. The product was an iced coffee energy product.

142 An entry on the “V” Energy Facebook page for 15 October 2010 states:

… Has anyone tried it yet? Just arrived in petrol and convenience stores is V’s NEW product V Iced Coffee, it has the great taste of iced coffee with the added kick of V Guarana Energy. …

143 The Campos Coffee “Dark City Cold Press” coffee product was promoted in Australia from at least January 2015. A post on the Campos Coffee Facebook page on 23 January 2015 states:

It’s never too hot for a coffee, but for a seasonal change try one of our cold press brews made with our Dark City blend, bottled with milk or without. Grab a four pack from any of our flagship stores for Australia Day!

144 The Campos Coffee “Iced Latte” coffee product was promoted in Australia from at least November 2015. A post on the Campos Coffee Facebook page on 7 November 2015 states:

Have you tried our #icedlatte yet? Made using our Dark City blend and fresh from-the-farm milk, it’s available in all our flagship stores… right now. #camposcoffee

145 The “Dare Double Espresso” iced coffee product was promoted in Australia from at least May 2010.

146 The “Barista Bros” iced coffee product was promoted in Australia from at least April 2014. The packaging of the product stated that it is made with “100% Arabica Coffee”.