FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Thompson v Lane (Trustee) [2023] FCAFC 32

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | MORGAN LANE AS TRUSTEE OF THE BANKRUPT ESTATE OF EMMA NARELLE CATHRYN THOMPSON First Respondent BODY CORPORATE FOR ARILA LODGE CTS 14237 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal is dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

CHARLESWORTH J:

1 On 1 July 2020 the appellant was made bankrupt by force of s 55(4A) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) upon the acceptance by the Official Receiver of her debtor’s petition. Some nine months later, the appellant applied to this Court for an order under s 153B(1) of the Act annulling her bankruptcy. The primary judge dismissed the application: Thompson v Lane (Trustee) (No 3) [2022] FCA 128. This is an appeal from that judgment.

2 The appeal should be dismissed for the reasons given below.

THE BANKRUPTCY ACT

3 Section 55(1) of the Act provides that a debtor may present to the Official Receiver a petition against herself. A petition so presented must be rejected by the Official Receiver for any one of the reasons specified in s 55(2A), none of which apply here. The Official Receiver otherwise has a discretion to reject a debtor’s petition in the circumstances specified in ss 55(3) or 55(3AA). Section 55(3AA) provides:

(3AA) The Official Receiver may reject a debtor's petition (the current petition) if:

(a) it appears from the information in the statement of affairs (and any additional information supplied by the debtor) that, if the debtor did not become a bankrupt, the debtor would be likely (either immediately or within a reasonable time) to be able to pay all the debts specified in the statement of affairs; and

(b) at least one of the following applies:

(i) it appears from the information in the statement of affairs (and any additional information supplied by the debtor) that the debtor is unwilling to pay one or more debts to a particular creditor or creditors, or is unwilling to pay creditors in general;

(ii) before the current petition was presented, the debtor previously became a bankrupt on a debtor's petition at least 3 times, or at least once in the period of 5 years before presentation of the current petition.

4 The power to reject a debtor’s petition in the circumstances there specified reflects the centrality of solvency in the bankruptcy jurisdiction.

5 A person is solvent if, and only if, the person is able to pay all the person’s debts as and when they became due and payable: Act, s 5(2).

6 As Deane J said in Re Sarina; Ex parte Wollondilly Shire Council (1980) 30 ALR 266 at 269, in the context of a bankruptcy resulting from a creditor’s petition:

It does not appear to me that it is possible to devine any policy underlying the provisions of the Act to the effect that a creditor should be entitled to make a recalcitrant debtor bankrupt even though the debtor satisfies the court that he is plainly solvent and able to pay his debts. It seems to me that it may well be that the legislative intent was to leave a creditor, in those circumstances, to the ordinary remedies by way of execution and garnishee.

7 It follows that an order should not be made under s 52(2) on a creditor’s petition against the estate of someone who refuses to pay debt if that person discharges the onus of proving that he or she is solvent.

8 The Full Court in Culleton v Balwyn Nominees Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 8 confirmed that Bankruptcy is not a variety of inter partes litigation dealing only with the private rights and obligations of the debtor and creditor, nor is a creditor’s petition to be utilised as a form of judgment execution. Rather (at [40]:

It is directed to the estate of a person who is insolvent. In that sense it has as a public interest, through the general body of creditors and potential creditors of the debtor and prospective bankrupt, and through what is referred to as the change of status of the person who becomes a bankrupt. That status is changed because of the provisions of the Act which inhibit conduct and affect rights and obligations of the bankrupt, including making the bankrupt susceptible to criminal punishment for what would otherwise be innocent conduct.

9 In Clyne v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 154 CLR 589 a creditor’s petition brought by the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation was pending when the debtor was made bankrupt on his own petition. The power to make a sequestration order on the Commissioner’s petition could no longer be exercised because, as Gibbs CJ, Murphy, Brennan and Dawson JJ explained (at 594-5), the effect of the bankruptcy was that the bankrupt was no longer obliged to pay his creditors:

… since the debtor was already bankrupt when the petition came to be heard, the remedies against the person and property formerly available to the Deputy Commissioner had been taken away and there was substituted a right to prove against the estate which had become vested in Mr. Andrew as trustee: see In re Thomas; Ex parte Commissioners of Woods and Forests (21). At that time the Deputy Commissioner "was not a mere creditor. [He] was a creditor whose claim was in proof. [His] claim was no longer a mere right of action for a debt. [He] could no longer have maintained an action as for a debt. The debt had been, at any rate provisionally, merged in an equitable execution ...": see In re Higginson & Dean; Ex parte Attorney-General (22); Ex parte Trustee of the Property of Cork (23); and In re Cole; Ex parte Richards (24). Amounts which were owed by a debtor at the date of the bankruptcy may, notwithstanding his bankruptcy, still be described as debts, and the Act refers to them as such: see, e.g., ss. 58(3), 84(1), 85(1), 86(1), 153(1), 154(1)(b). They are "debts" from which the bankrupt is not released until he is discharged from bankruptcy: s. 153. However, in our opinion, they are no longer debts "still owing" within the meaning of s. 52(l)(c). Although, as was rightly observed in the Federal Court, one dictionary meaning of "owing" is "that is yet to be paid", the word connotes a sense of obligation to make the payment. The effect of the bankruptcy however is that the debtor is no longer obliged to pay his creditors; indeed he is disabled from doing so. If he offered payment they could not safely accept it; their right is a right of proof against the estate.

Annulment

10 Sub-section 153A(1) of the Act provides that if the trustee of a bankrupt estate is satisfied that all of the bankrupt’s debts have been paid in full, the bankruptcy is annulled, by force of that subsection, on the date on which the last such payment was made. No Court order is necessary to bring about annulment in those circumstances.

11 A bankruptcy may also be annulled by an order of this Court under s 153B(1) of the Act. It relevantly provides:

Annulment by Court

(1) If the Court is satisfied that a sequestration order ought not to have been made or, in the case of a debtor's petition, that the petition ought not to have been presented or ought not to have been accepted by the Official Receiver, the Court may make an order annulling the bankruptcy.

(2) In the case of a debtor's petition, the order may be made whether or not the bankrupt was insolvent when the petition was presented.

12 As can be seen, the power to make an order under s 153B of the Act is discretionary. However, in the case of a debtor’s petition, the discretion may not be exercised unless one of the two preconditions for its exercise is fulfilled. It is for that reason that exercise of the power is said to involve a two-step process. In the case of a bankruptcy brought about by a debtor’s petition the Court must first be satisfied either that the petition ought not to have been presented by the debtor or that it ought not have accepted by the Official Receiver in order for the discretion to be enlivened. It is only then that the discretionary power may be exercised.

13 The two-step process was described by the Full Court of Carr, Finn and Sundberg JJ in Heinrich v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2003] FCAFC 315 in the similar context of a bankruptcy created by a sequestration order on a creditor’s petition (at [20]):

The Court must first consider whether the sequestration order ought not to have been made. If it so finds, then the Court must consider whether, in the exercise of its discretion, the bankruptcy should be annulled: Re Deriu (1970) 16 FLR 420. Later evidence of previously unknown facts may disclose matters which show that the sequestration order ought not to have been made. That is, the Court is entitled to consider not only the case as disclosed at the time when the sequestration order was made, but also those facts now known then to have existed. The Court excludes those facts which have occurred since the order was made. Later evidence of previously unknown facts may disclose matters which show that the sequestration order ought not to have been made: Re Frank; Ex parte Piliszky (1987) 16 FCR 396; Stankiewicz v Plata [2000] FCA 1185 at [19]; Re Williams (1968) 13 FLR 10 at 23; Re Ditfort; Ex parte Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1988) 19 FCR 347.

14 In Beaman v Bond (2017) 254 FCR 480 McKerracher J said that in exercising the discretion to annul, the Court is to have regard not only to the interests of the parties but to the interests of the public, and that neither is paramount over the other (at [79]), Gilmore and Charlesworth JJ agreeing).

15 It is well established that a bankruptcy brought about by a creditor’s petition may be annulled if the applicant establishes that the creditor’s petition was presented in circumstances amounting to an abuse of process, including because it was utilised as a form of judgment execution against a recalcitrant yet solvent debtor: Shaw v Yarranova (2017) 252 FCR 267.

16 The presentation of a debtor’s petition may constitute an abuse of process if it is brought for the purpose of frustrating a creditor’s ability to obtain a sequestration order or for the purpose of putting property beyond the reach of the trustee by reason of different relation back dates: Clyne at 598.

17 As s 153B(2) of the Act makes plain, in the case of a bankruptcy brought about by a debtor’s petition, an annulment order may be made whether or not the bankrupt was insolvent at the time when the petition was presented. Cases decided before the introduction of s 153B(2) should be applied with caution. Solvency will nonetheless remain an important issue informing the question of whether the provisions of the Act have been invoked by the debtor for an improper purpose. In addition, the circumstance that a debtor was insolvent at time of the presentation of the petition may be a critical factor in determining the question of whether the petition ought not to have been presented and may also be an important factor in the exercise of the discretion to annul.

18 To show that the debtor’s petition ought not to have been presented it will not usually be sufficient for an applicant debtor to show that in retrospect, and given better advice, he or she might have pursued options other than bankruptcy: Re Official Trustee [1999] FCA 1755 at [15].

The effect of an annulment order

19 Section 154 of the Act prescribes the effect of an annulment order made under s 153B. Relevantly:

(1) acts done by the trustee or any person acting under the trustee’s authority are taken to have been validly done (s 154(1)(a));

(2) the property of the former bankrupt still vested in the trustee may be applied in payment of the trustee’s costs, charges and expenses associated with the administration of the former bankrupt’s estate (s 154(1)(b)); and

(3) subject to exceptions, the remainder (if any) of the property of the former bankrupt still vested in the trustee reverts to the bankrupt (s154(1)(c)).

20 Except as provided for in s 154, the annulment has the effect that the bankruptcy will be treated as never having taken place and the debtor is therefore put back in the position he or she would have been in had the bankruptcy never occurred: Re Coyle at 77. It must follow that the rights and obligations vis a vis the debtor and his or her creditor are revived or restored, except to the extent provided for in s 154 of the Act. Accordingly, an annulment may bring about a circumstance where creditors are left to pursue a recalcitrant but solvent debtor.

REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE

21 At first instance it was not disputed that at the time that the appellant presented her debtor’s petition, a creditor’s petition had been presented by Body Corporate for Arila Lodge CTS 14237 (BCAL) (now the second respondent on this appeal) and was pending before the then-named Federal Circuit Court of Australia. The creditor’s petition was founded on a bankruptcy notice specifying a debt in the amount of $80,266.85. Upon the appellant becoming bankrupt on her own petition, BCAL’s creditor’s petition was dismissed. The costs of those proceedings were ordered to be paid from the appellant’s bankrupt estate with the same priority as if a sequestration order had been made on it.

22 As on this appeal, the trustee of the bankrupt estate, Mr Morgan Lane, abided the event at first instance. Mr Lane nonetheless participated in the proceedings, including by providing a report to the primary judge and expressing an opinion as to the appellant’s solvency.

23 The primary judge observed that there was little authority concerning the annulment of a bankruptcy grounded in the acceptance of a debtor’s petition, but considered that it was possible to derive relevant considerations by reference to s 55 and s 153B of the Act. He observed (correctly) that s 153B(2) provided for an annulment order to be made in the Court’s discretion whether or not the debtor was solvent at the time of the presentation of his or her petition (at [10], [19]).

24 The primary judge cautioned himself against uncritically applying cases concerning annulment of a bankruptcy created by sequestration order on a creditor’s petition, or applying principles deriving from such cases too mechanically (at [10]).

25 The primary judge identified (again correctly) that the question of annulment involved a two-step process (at [7]) and that the onus of proving that the bankruptcy should be annulled fell on the appellant (at [8]).

26 The primary judge emphasised that a bankrupt carries a heavy burden to make full disclosure of his or her financial affairs (citing Re Papps; Ex parte Tapp (1987) 87 FCR 524 at 531). His Honour said (at [12]):

This does not, of course, mean that the standard of proof applicable to facts in an annulment application is anything other than the ordinary, civil standard of proof on the balance of probabilities: s 34A, Bankruptcy Act. What it does mean is that an applicant must be completely candid. An apparent absence of candour, especially where it suggests that an applicant’s true present financial position may not be one of solvency, or may be much worse than asserted, may well offer a basis upon which to exercise a discretion so as not to annul a subsisting bankruptcy.

27 The primary judge identified a number of considerations arising from the terms of s 55 of the Act the inform that question of whether a debtor’s petition ought not to have been presented or accepted. The correctness of that summary is not challenged on this appeal and is here set out in full:

14 Regard to s 55 of the Bankruptcy Act discloses a number of bases upon which a debtor’s petition ought not to be presented:

(a) flowing from s 55(2)(b), if it is not accompanied by a statement of affairs completed by the debtor;

(b) flowing from s 55(2A), the debtor has no relevant connection with Australia at the time when the petition was presented, the relevant connections being that the debtor:

(i) was personally present or ordinarily resident in Australia; or

(ii) had a dwelling-house or place of business in Australia; or

(iii) was carrying on business in Australia, either personally or by means of an agent or manager; or

(iv) was a member of a firm or partnership carrying on business in Australia by means of a partner or partners or of an agent or manager.

(c) flowing from s 55(5A), the debtor is a party (as debtor) to a debt agreement and has not been given permission by the Court to present a debtor's petition;

(d) flowing from s 55(6), the debtor has executed a personal insolvency agreement and has not received the leave of the Court to present a petition against himself or herself unless:

(i) the agreement has been set aside; or

(ii) the agreement has been terminated; or

(iii) all the obligations that the agreement created have been discharged.

(e) flowing from s 55(6A), a stay under a proclaimed law is applicable to the debtor and the debtor has not received the leave of the Court to present a petition against himself or herself.

15 Regard to s 55 of the Bankruptcy Act also discloses a number of bases upon which the Official Receiver is empowered not to accept a debtor’s petition:

(a) flowing from s 55(2), the debtor has no relevant Australian connection (as detailed above);

(b) flowing from s 55(3):

(i) the petition does not comply substantially with the approved form; or

(ii) the petition is not accompanied by a statement of affairs; or

(iii) the Official Receiver thinks that the statement of affairs accompanying the petition is inadequate.

(c) flowing from s 55(3AA), it appears to the Official Receiver from the information in the statement of affairs (and any additional information supplied by the debtor) that, if the debtor did not become a bankrupt, the debtor would be likely (either immediately or within a reasonable time) to be able to pay all the debts specified in the statement of affairs and either or each of the following is applicable:

(i) it appears from the information in the statement of affairs (and any additional information supplied by the debtor) that the debtor is unwilling to pay one or more debts to a particular creditor or creditors, or is unwilling to pay creditors in general;

(ii) before the current petition was presented, the debtor previously became a bankrupt on a debtor's petition at least 3 times, or at least once in the period of 5 years before presentation of the current petition.

28 The primary judge discussed the meaning of “solvency” and “insolvency” before turning to consider the “bankruptcy form” completed by the appellant. His Honour said that the form raised more questions than it answered. He observed that the appellant had stated that:

(1) she had been unemployed for 7 years and that her only source of income in the last 12 months and anticipated following 12 months were government pensions and allowances of about $1,100.00 per fortnight;

(2) she had five unsecured creditors with estimated debts totalling $505,500.00 (including a claim asserted by BCAL in the amount of $400,000.00). All but $500.00 was “disputed” by the appellant;

(3) she had an interest of unspecified value in her father’s estate;

(4) she owned a house in Hawthorne and a unit in Toowong (in the complex of which BCAL was the body corporate), with a combined value of $3.5m; and

(5) the Hawthorne house was subject to a mortgage to Suncorp Bank connected with a $2 m debt which she disputed.

29 The primary judge referred to the change of the appellant’s status brought about by bankruptcy. His Honour said that Ms Thompson’s assertion on the face of the forms that she was insolvent because of legal action did not provide a reason in of itself for the Official Receiver to accept her petition (at [32]). His Honour observed:

Her declared income and non-realty assets were, with respect, modest but so, too, was her only undisputed debt. Further, even allowing for a dispute as to the amount of the estimated secured debt, there was an apparent surplus of more than $1 million in her net realty asset position. In turn, that surplus was more than enough, if realised, to meet the declared disputed debts. On the face of the “Bankruptcy Form”, Ms Thompson may well have been insolvent but that position was not clear. Given what was declared, Ms Thompson’s case may just possibly have been one where, within a reasonable time she could have paid her debts and where she was unwilling to pay debts to particular creditors. Potentially then, the case was one where it may have been possible for an Official Receiver, pursuant to s 55(3AA) and as a matter of discretion, to reject Ms Thompson’s petition.

30 The primary judge nonetheless concluded (at [33]) that the Official Receiver was not obliged under s 55(3AB) to reject the petition under s 55(3AA). His Honour said that it was not a case where a debtor’s petition “ought not to have been accepted” within the meaning of s 153B because:

The standard posited by that section is not met where, as a matter of discretion, a petition might not be accepted by an Official Receiver but where there is no obligation to exercise that discretion.

31 Importantly for present purposes, the primary judge said that the case was not one which turned on whether or not the debtor’s petition ought not to have been presented or accepted, even though the appellant had those raised those issues on her application ( at [36]). The real issue, his Honour said, was whether the appellant’s bankruptcy should be annulled in the exercise of the Court’s discretion (at [36]). The primary judge said that an important question in that regard was “whether or not she is, having regard to the test as explained above, solvent?”.

32 On the question of solvency, the primary judge accepted the opinion of the trustee that the appellant was “not solvent” and rejected the arguments of the appellant as to why he should not act on it. The main focus of the “solvency” enquiry was not so much the financial position of the appellant at the time of presenting the debtor’s petition, but the sufficiency of the property vested in the trustee to discharge all of the appellant’s liabilities. In respect of the ‘debt’ side of that equation, his Honour’s starting point was the total amount of claims specified in proofs of debt received by the trustee (none of which had been admitted by the trustee). They totalled $1,332,934.00. Of that amount, $820,479.00 was claimed by “BCAL C/- Grace Lawyers”.

33 The property of the bankrupt estate was held to include a recovered amount of $930.00. Save for that amount, the primary judge said at [39] that the “bankrupt estate is presently without funds”.

34 As to the Hawthorne property, the primary judge held that Suncorp Bank had entered into possession of the property prior to the presentation of the debtor’s petition. The property had been sold by 19 December 2020 and settlement on the sale had occurred on 18 January 2021. The trustee estimated that “at least $368,750” was payable to the appellant’s bankrupt estate after discharge of the debt owed to Suncorp Bank and its recovery costs. The settlement statement indicated that that very amount had been paid by Suncorp Bank to the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation. However, as no proof of any taxation debt had been lodged, the trustee had assumed the sum to be a recoverable asset and the primary judge took the amount into account in considering the property available to discharge liabilities (at [43]).

35 The primary judge addressed submissions of the appellant to the effect that the Hawthorne property had been sold at an undervalue, given that a government assessment had valued the unimproved land at $3,500,00.00. His Honour said that the valuation raised “an interrogative note ... in terms of whether Suncorp Bank discharged its duties as mortgagor [sic] in possession” (at [46]), but the remedy in that respect was an action for damages that had vested in the trustee. The primary judge did not consider the realisation of the Hawthorne property would support a conclusion that the appellant “was solvent either at 26 June 2020 or at present”.

36 The primary judge concluded that the evidence did not indicate the appellant’s claimed interest in her father’s estate had any value, adding that the executor of the deceased estate had lodged a proof of debt in the amount of $186,221.00 said to be owed by the appellant to the estate, and the appellant’s evidence had not shown that amount to be excessive.

37 As to the Toowong unit, the primary judge held that it was subject to debts (estimated by the trustee at $412, 605.97) that could be enforced against any purchaser, making it difficult to sell unless they were first discharged (at [55]). The primary judge concluded that a sale of the unit after discharge of those debts would net $332,394.03 and that the value of the real property assets was (at most) $681,144.03, which fell “dramatically short” of the trustee’s preliminary assessment of the other debts, let alone the trustee’s costs of administering the bankrupt estate (at [58]).

38 The trustee’s claimed costs and expenses were $192.455.71. The primary judge said that the appellant “had made no proposal, as part of her annulment application” as to how the trustee’s expenses might be settled, either in whole or in part”, and that the costs of the administration were in part a reflection of the lapse of time between the presentation of the debtor’s petition and the commencement of the annulment application (at [60]).

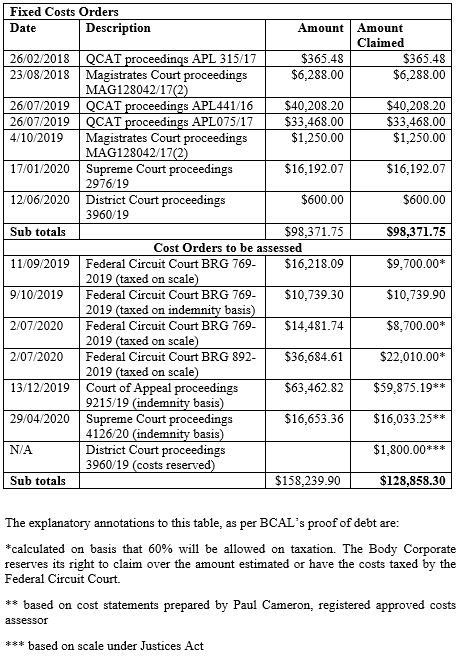

39 The primary judge went on to discuss aspects of the proof of debt lodged by BCAL, $128,858.30 of which included amounts owing pursuant to fixed costs orders or cost orders that were yet to be assessed. His Honour traced some of the litigious history resulting in BCAL’s claims, which had their genesis in a dispute about a water leak in the Toowong block of units for which the appellant was alleged to be responsible. The primary judge applied, by analogy, the same principles guiding the Court’s power to make a sequestration order in cases where judgment debts are in issue (at [70]). His Honour continued:

71 Annulment does not affect sales and dispositions of property and payments duly made and acts done, by the bankrupt’s trustee, or any person acting under the authority of the trustee or the Court, before the annulment: s 154(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. Further, a trustee is entitled to be reimbursed in respect of costs of administration out of property which on bankruptcy vested in the trustee: s 154(1)(b) and s 154(2). Subject to this and to other exceptions in s 154 not presently relevant, the effect of annulment is that the remainder (if any) of the property of the former bankrupt still vested in the trustee reverts to the bankrupt: s 154(1)(c) of the Bankruptcy Act.

72 Thus, deciding whether or not to annul a bankruptcy may also affect the rights and interests of each of a bankrupt’s creditors in being paid their debts in full. If a person remains in bankruptcy, the rights of unsecured creditors (or secured creditors with a deficiency) become rights to prove in the bankruptcy and to receive such distribution as may be payable to them from the property of the bankrupt in accordance with the Bankruptcy Act. Annulment could therefore bring with it for creditors a right to have payment in full. One reason for annulment might be that in truth and reality there is no particular debt or debts such that a person is not presently and never was insolvent.

40 His Honour rejected the appellant’s arguments as to the costs orders, including because her arguments were or could have been raised in the litigation to which they related (at [65], [77]), the outcomes were not the result of fraud, collusion or miscarriage of justice (at [74]) and because her assertion that BCAL had not been authorised to commence the litigation was without merit (at [78] - [79]).

41 As to the larger part of the BCAL proof of debt that was not founded in any fixed cost order, the primary judge said that the trustee had engaged a costs assessor to advise him in relation to its claim, but was yet to receive a report (at [80]) and the appellant’s onus of proofing that the proof was excessive “as part of demonstrating solvency” had not been discharged.

42 The primary judge referred to the appellant’s evidence that on 5 December 2019 she had received an email from a financial institution confirming that she had been approved for a loan in an amount that exceeded the amount specified in BCAL’s creditor’s petition (still pending at that time). His Honour said that the email was not an unconditional loan of funds and concluded, on the basis of evidence of the trustee, that no loan approval had been given. It would not be sufficient, his Honour said, for the appellant “to demonstrate present insolvency” to prove that she would have been able (had she chosen) to pay the debt demanded in the bankruptcy notice from borrowed funds.

43 The primary judge concluded that at the time that she presented her debtor’s petition, the appellant had already defaulted on borrowings from Suncorp Bank, she was the subject of multiple costs orders of which even the fixed components were unpaid, that “she was greatly in arrears in amounts owed to BCAL”, and that her income was insufficient to pay those debts. His Honour continued (at [84]):

Even on a generous assessment of the equity she had in the Hawthorne Property and even assuming, also generously, that each of that property and the Toowong Unit might then have been sold within a reasonable time thereafter, the proceeds of the sale would have been insufficient to meet her debts. She has certainly not proved otherwise. Even accepting, in light of s 153B(2) that an annulment order might be made even though she was insolvent when her debtor’s petition was presented, neither has she proved that the position is any better at present. Ms Thompson has not proved that she is presently solvent. The evidence before the Court, such as it is, confirms [the trustee’s] opinion that she is not solvent. Given this, I am not persuaded that her bankruptcy should be annulled.

44 The primary judge said that the appellant’s failure to prove “present insolvency” and her failure to make any proposal for the payment of any part of the trustee’s costs of administration provided reasons in themselves not to annul her bankruptcy. Again, his Honour’s reference to “present insolvency” equated to an assessment of whether there was sufficient property to be realised within by the trustee with the context of an ongoing bankruptcy to fully discharge the proofs of debts that had been lodged.

45 The primary judge took into account other factors, including that the annulment application had not been made promptly. In conclusion, his Honour said (at [86]):

Another factor is [the trustee’s evidence] that, despite numerous requests of her by him to comply with s 77 of the Bankruptcy Act regarding the provision of her books and records, Ms Thompson has failed to do so, though acknowledging that she holds books and records. I accept [the trustee’s] evidence on this subject. Ms Thompson’s stance, evident in her evidence and submissions, has been to request that [the trustee] advise her as to what documents “we require her to provide”. This inverts the requirements of the Bankruptcy Act and, in any event, [the trustee] has made it plain enough what he requires of her. In my view, this is an additional reason why her bankruptcy ought not to be annulled. There is a public interest, given this conduct, in her remaining subject to the restrictions and duties imposed on a bankrupt by the Bankruptcy Act. Her case is one were her estate should continue to be administered in insolvency. There is no public interest, and certainly no interest of creditors, served by the annulment of her bankruptcy.

THIS APPEAL

46 I have had the benefit of reading the reasons of Downes J in draft. The matters raised on the appeal by the appellant are conveniently summarised by her Honour.

47 The contention that the primary judge failed to comply with the rules of procedural fairness should be rejected for the reasons given by Downes J.

48 As explained earlier in these reasons, the power to annul the appellant’s bankruptcy was discretionary. However, the discretion in the appellant’s case was not enlivened unless either of the two alternative pre-conditions were met. The primary judge held that it had not been established that the Official Receiver ought not to have accepted the petition for reasons based on his Honour’s preferred construction of the s 153B(1) of the Act. The appellant did not address that aspect of the reasons of the primary judge and so has not established that the reasoning was affected by appealable error. In the absence of submissions on the question it is unnecessary to express a view as to whether the legal basis for that finding was correct.

49 I am unable to identify a positive finding of the part of the primary judge that the alternative pre-condition to the exercise of the power was fulfilled. The reasons at [36] proceed from an assumption that the appellant’s bankruptcy may be annulled in the Court’s discretion whether or not the Court was positively satisfied that the petition ought not to have been presented or that the petition ought not to be accepted. In my view, that approach was erroneous. However, identification of that error does not justify the grant of relief on this appeal.

50 At the hearing of the appeal the appellant presented arguments as to why the debtor’s petition “ought not to have been presented” within the meaning of s 153B(1) of the Bankruptcy Act. At first instance (as on this appeal) it was necessary for the appellant to establish the fulfilment of that condition because if that was not done, it must follow that neither precondition to the exercise of the power existed, and the discretion to make an order annulling her bankruptcy was not enlivened.

51 The primary judge correctly identified that proof of solvency at the time of the presentation of the debtor’s petition would not of itself be sufficient to justify the annulment. Actual solvency at the time of the presentation of the debtor’s petition is a relevant matter in determining whether the debtor’s petition ought not to have been presented, including because it may indicate that the Act had been utilised for a purpose other than that identified in the authorities discussed at the outset of these reasons. Questions would then arise as to whether an annulment brought about wrongly by the debtor should be ordered on the application of the debtor herself.

52 I agree with the conclusion of Downes J that the primary judge did not err in his conclusion that the appellant was indeed insolvent at the time that she presented the debtor’s petition. I also agree with her Honour’s reasons for rejecting the other bases put forward by the appellant to support the contention that the petition ought not to have been presented. I specifically reject the contention that any one of the other respondents wrongly induced the appellant to petition for her own bankruptcy.

53 It follows that the preconditions for an annulment order have not been shown to exist.

54 It cannot assist the appellant to show that the primary judge erred in the exercise of a discretion he did not have. Demonstration of such an error would not be sufficient to empower this Court in its appellate jurisdiction to make an order under s 153B of the Act annulling the bankruptcy. That is a sufficient basis to dismiss the appeal.

55 It is appropriate to make some further observations about the appellant’s submissions concerning her financial position and the reasons of the primary judge on that topic.

56 The primary judge undertook a detailed enquiry into the “present solvency” of the appellant. In the course of doing so, he concluded that the appellant had not put forward a proposal to meet the trustee’s expenses of administering her estate. Those two considerations were said by the primary judge to be a sufficient basis not to annul the bankruptcy (at [86]).

57 The expression “present solvency” (as the primary judge employed it) is not an apt expression in the context of an annulment application made under s 153B of the Act. That is because the concept of solvency depends not only upon the existence of liabilities in the nature of debts, but upon the time at which the debts are due and payable by the debtor and the capacity of the debtor to pay at that point in time. Upon and by virtue of a bankruptcy, the bankrupt has no liability to pay his or her debts at all. The rights of creditors with respect to the debts are converted to a right to lodge a proof of debt and to share in the rateable distribution of the bankrupt’s property in accordance with the provisions of the Act. It is not correct to speak of debts forming the subject of creditors’ proofs within the bankruptcy regime as being debts that are presently due and payable, let alone debts that are due and payable by the bankrupt.

58 It was of course appropriate and necessary for the primary judge to consider the financial position the appellant would be in if the bankruptcy were to be annulled. But that question must be answered in the context of s 154 of the Act, particularly on the footing that the appellant would then be in the same position vis a vis her creditors as if the bankruptcy had not occurred at all.

59 That is not to diminish the importance of the question of whether the appellant would be solvent immediately upon an annulment. The appellant herself raised that question at first instance and it formed a significant part of her submissions on the appeal. However, the approach adopted by the primary judge to resolve that question to my mind was incorrect. The effects of s 154 of the Act were not properly considered and his Honour proceeded from the assumption that all of the debts subject to the lodged proofs would be immediately due and payable upon the annulment.

60 To the extent that the primary judge assessed “present solvency” by reference to the lodged proofs of debt, none of the proofs had been formally admitted by the trustee and the full extent of the appellant’s liabilities had not in fact been ascertained by him. Importantly, the dates on which many of them might otherwise be due and payable in the event of an annulment was not the subject of findings that properly took into account the legal consequence of an annulment under s 154 of the Act. A good part of the debt claimed to be owed to BCAL (not in the nature of judgment debt) falls within that category.

61 The primary judge placed significant weight on the circumstance that the appellant had not positively put forward a proposal for the payment of the trustee’s expenses in administering the appellant’s bankrupt estate. However, on the facts as found by the primary judge the surplus from the sale of the Hawthorne property (in an amount exceeding $348,000.00) had vested in the trustee. In the event of an annulment order, s 154(1)(b) of the Act would operate to ensure that the trustee’s expenses and remuneration would be paid in priority from that property. The remainder of the vested property would then vest in the appellant by the operation of s 154(1)(c) and would be available to her to pay any debts then due. On any view of the found facts, the remainder was sufficient to pay the debt specified in the bankruptcy notice (as well as BCAL’s costs referable to the creditor’s petition) such that if a further notice was issued in respect of the same claimed debts, it was not at all clear that the appellant would be unable to pay them should the bankruptcy be annulled. In accordance with the authorities, whether the appellant would have been willing to pay them was not to the point. She could not be made bankrupt on the basis that she was a recalcitrant but solvent debtor.

62 Were it not for our conclusion that the power to annul the appellant’s bankruptcy was not enlivened, I would have been minded (given the self-represented status of the appellant) to invite further submissions as to whether the grounds of appeal established a proper basis for remittal of the annulment application for determination on a proper understanding of the law, particularly s 154 of the Act.

63 The primary judge was otherwise correct to find that the appellant had not complied with her obligations under the Act to produce books and records to the trustee. However, I do not consider that that finding was identified by his Honour as a sufficient basis in and of itself to warrant the dismissal of her originating application. The reasons, particularly at [86], are not expressed in that way.

64 There should be an order dismissing the appeal with costs.

I certify that the preceding sixty-four (64) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Charlesworth. |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

DOWNES J:

OVERVIEW

65 This is an appeal from the dismissal of an application to annul the appellant’s bankruptcy pursuant to s 153B Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth): Thompson v Lane (Trustee) (No 3) [2022] FCA 128 (J).

66 The appellant’s bankruptcy commenced on 1 July 2020 after the appellant completed a debtor’s petition on 26 June 2020 (which included a form which was described by the primary judge as the bankruptcy form), which was then lodged. The appellant declared in that form that she had been unemployed for seven years and that she was a student. In this regard, it is relevant to observe that, since 2013, the appellant has been awarded a Bachelor of Laws, Graduate Diploma in Legal Practice and Masters in Legal Practice, and is currently a PhD candidate.

67 The appellant is the former registered proprietor of real property located at Hawthorne, Queensland which had been mortgaged to Suncorp Bank as security for a loan to the appellant. In her oral submissions to the primary judge, the appellant stated that she “didn’t make repayments at times because I have been unemployed”. Suncorp Bank took possession of the Hawthorne property prior to the appellant’s bankruptcy, selling it at public auction.

68 In 2014, the appellant acquired a unit in a residential complex called Arila Lodge located in Toowong, Queensland, and has resided in that unit since at least 2016. There is a body corporate for a community titles scheme relating to that complex. The body corporate is the second respondent to this appeal.

69 Between 2016 and 2020, the appellant and body corporate engaged in litigation which related to various claims concerning damage caused by a water leak from the appellant’s unit, windows in the appellant’s unit, unpaid contributions and a dog in the appellant’s unit. The litigation involved proceedings before an adjudicator appointed under the Body Corporate and Community Management Act 1997 (Qld), the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal, the Magistrates Court of Queensland, the District Court of Queensland, the Supreme Court of Queensland and the (then) Federal Circuit Court. This litigation has resulted in numerous costs orders being made in favour of the body corporate, including in fixed sums, which were not paid by the appellant. As a result, the body corporate filed a creditor’s petition.

70 Before the creditor’s petition came on for hearing, the appellant became bankrupt. The trustee in bankruptcy, Mr Morgan Lane, is the first respondent. Mr Lane was appointed on 1 July 2020.

71 During the period of her litigation against the body corporate up to and including the date on which she lodged her debtor’s petition, the appellant was represented by different law firms. Mr Lane has received proofs of debt from some of these firms, which contain claims for unpaid legal fees in the total sum of approximately $297,000.

72 After his appointment, the appellant advised Mr Lane that she is an admitted lawyer and offered to act on his behalf in her bankrupt estate. She also advised him that she was admitted to practice in another jurisdiction and that she could “sign the roll” in Queensland. Mr Lane did not take up the offer.

73 The administration is without funds apart from the amount of $930, and Mr Lane has received proofs of debt totalling $1,146,213. This total does not include two further costs orders made against the appellant in the Federal Circuit Court.

74 As at 27 August 2021, Mr Lane had incurred costs and outlays which totalled $192,455.71 in administering the bankrupt estate of the appellant, and had only been reimbursed $691.24 of that sum.

75 Between at least December 2020 and 8 April 2021, Mr Lane issued requests to the appellant seeking that she provide to him all books that are in her possession that relate to her examinable affairs as required by s 77(1)(a) Bankruptcy Act. The appellant has not complied with those requests.

76 On 14 April 2021, being shortly after Mr Lane’s last request for the books made on 8 April 2021, the appellant filed the annulment application which came before the primary judge, who dismissed it on 18 February 2022.

77 For the reasons which follow, the appeal should be dismissed, with costs.

THE APPEAL

78 The notice of appeal which was filed by the appellant contained several pages of alleged “errors of fact and errors of law”. These were, in substance, identification of grounds of appeal as well as submissions about those grounds. For that reason, the appellant was relieved of the obligation to file written submissions prior to the hearing.

79 During the hearing of the appeal and by Order dated 4 August 2022, the appellant was granted leave to file supplementary submissions on or before 1 September 2022 comprising:

(1) a copy of her notice of appeal containing cross-references to any materials before the primary judge in QUD113/2021 relied upon in support of each ground;

(2) if the appellant so wished, a copy of the transcript of the argument [in the hearing of the appeal] cross-referenced to any material before the primary judge upon which she relies upon in support; and

(3) a copy of Exhibit MFI-A1 cross-referenced to the materials before the primary judge upon which she relies.

80 By Order dated 5 December 2022, the appellant was permitted to file the supplementary submissions, notwithstanding that they had not been filed by 1 September 2022.

81 Pursuant to the Order dated 5 December 2022, the appellant lodged an affidavit on 7 December 2022 (which was accepted for filing on 8 December 2022). The appellant’s supplementary submissions, which were 61 pages in length, were an annexure to that affidavit. By the appellant’s affidavit, the appellant attested that the supplementary submissions comply with the requirements of the Order dated 4 August 2022.

82 However, upon review, it was apparent that the supplementary submissions were not confined to addressing the matters identified in the Order dated 4 August 2022. Relevantly, they sought to raise additional errors not contained in the notice of appeal and they referred to facts which were not supported by evidence which had been before the primary judge.

83 In addition, an affidavit which had not been before the primary judge at the hearing below (without exhibits) was also attached to the supplementary submissions.

84 I have had regard to the supplementary submissions to the extent that they do the things identified in the Order dated 4 August 2022, but not otherwise.

85 Further, I have not had regard to any evidence which was not before the primary judge in relation to the decision which is the subject of this appeal. In particular, I have not had regard to evidence which the appellant sought to have admitted after the hearing before the primary judge, and the rejection of which was the subject of a separate decision by the primary judge delivered on 17 December 2021, more than a year ago and from which no appeal was brought. This decision is referred to by the primary judge at [83] J:

Ms Thompson also sought, after judgment had been reserved, to re-open proceedings so as to lead further evidence, notably evidence of superannuation balances in respect of superannuation funds not listed by her in her Bankruptcy Form and not earlier disclosed to Mr Lane. All of this evidence could have been adduced by her at trial with ordinary diligence and attention to the responsibilities of a party to proceedings in this Court. For reasons separately delivered, I dismissed this application.

86 Generally, I observe that the task of the Court in this appeal is the same as that identified by the Full Court in Shaw v Yarranova Pty Ltd (2017) 252 FCR 267; [2017] FCAFC 88 (North, Perry and Charlesworth JJ), which was also an appeal from the dismissal of an application under s 153B Bankruptcy Act to annul a bankruptcy. That task was stated by the Full Court at [11]–[13] to be as follows:

This appeal is in the nature of a rehearing: Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Jia Legeng (2001) 205 CLR 507 at [75] (Gleeson CJ and Gummow J). The task of the Court on such an appeal is the correction of error: CDJ v VAJ (No 1) (1998) 197 CLR 172 at [111]. The demonstration of error in any given case depends not only upon the evidence but also on the nature of the findings or conclusions made by the primary judge.

The demonstration of error affecting findings or conclusions involving elements of fact, degree, opinion or judgment will ordinarily be more difficult to demonstrate than errors affecting conclusions about matters in respect of which there can be only one correct answer: Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd (2001) 117 FCR 424 at [24]–[25] (Allsop J). Where error affecting the exercise of a discretionary power is alleged, the Court on appeal will not interfere unless the error falls within the principles stated by the High Court in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 (House v The King) at 504–505 (Dixon, Evatt and McTiernan JJ) …

The cumulative effect of these principles is that the appeal is not an occasion for [the appellant] to re-agitate arguments that were rejected in the sequestration proceedings, or other proceedings in which he has been unsuccessful against the respondents, so as to have this Court determine the issues afresh in his favour. Rather, he must demonstrate appealable error affecting the decision of the primary judge not to annul his bankruptcy in accordance with the principles we have stated.

WHETHER APPELLANT DEMONSTRATED THAT DEBTOR’S PETITION OUGHT NOT TO HAVE BEEN PRESENTED OR ACCEPTED

87 To enliven the discretion conferred on the Court to annul a voluntary bankruptcy, s 153B Bankruptcy Act requires the Court to be satisfied that the petition ought not to have been presented or ought not to have been accepted by the Official Receiver: see Beaman v Bond (2017) 254 FCR 480; [2017] FCAFC 142 (McKerracher J, Gilmour and Charlesworth JJ agreeing) at [38].

88 To meet this threshold issue, the notice of appeal refers to a meeting on 1 June 2020 at which Mr Lane was informed to the effect that the appellant had “capacity to pay the amount on the Creditor’s Petition” but that she was “unwilling” to sell the residential unit and the Hawthorne property, and “unwilling” to pay the body corporate and other creditors associated with legal proceedings commenced by the body corporate. The appellant therefore relies on the fact of her solvency at the time that she presented her petition as well as the fact that she was unwilling (and disclosed to Mr Lane that she was unwilling) to pay certain claimed debts.

89 For the reasons given below, I do not accept that the primary judge erred in deciding that the appellant was insolvent when she lodged her petition. As a result, her willingness to pay her debts (whether disclosed to Mr Lane or otherwise) is irrelevant to the inquiry as to whether her petition ought not to have been presented or accepted. That is because, whether she was willing or not, the appellant was not able to pay all her debts, as and when they became due and payable, and so was not solvent: see s 5(2) Bankruptcy Act.

90 The appellant also complained that Mr Lane (an accountant and registered bankruptcy trustee) did not give her advice about other options on 26 June 2020, being the date that the appellant completed the bankruptcy form. However, the appellant did not identify what advice ought to have been given by Mr Lane (but was not) nor did she establish by her evidence what she would have done (if anything) had such advice been given.

91 By his affidavit evidence below, Mr Lane stated that he was introduced to the appellant by her solicitor, Mr Charles Londy. Mr Lane said that at a meeting with the appellant and her friend on 1 June 2020, they discussed bankruptcy and its consequences and effect. He said that at a further meeting with the appellant and her friend on 26 June 2020, he again discussed bankruptcy and what happens upon going bankrupt. Mr Lane said that, at that second meeting, the appellant advised that she wanted to lodge her own bankruptcy petition rather than be bankrupted on the creditor’s petition of the body corporate.

92 At the hearing before the primary judge, Mr Lane gave evidence that what the appellant told him was that she had no money and she was not able to pay the debt (being the debt claimed in the creditor’s petition). Later in his evidence, Mr Lane also referred to the fact that, according to the statement of affairs, the appellant had no assets other than a sum in a bank account which was around $2,000 and the two properties. Mr Lane gave evidence that, as at 1 July 2020, the appellant did not have the liquid resources to pay her creditors.

93 Mr Lane also gave evidence that the appellant had a solicitor representing her at the time (which was the case). Indeed, by her supplementary submissions, the appellant submitted that she “completed her debtor’s petition in reliance upon legal advice” of her solicitor. That she received such legal advice was also referred to in her affidavit evidence before the primary judge.

94 In summary, then, at the time of lodging the debtor’s petition, the appellant was not solvent, the consequences and effect of bankruptcy were explained to her by a registered bankruptcy trustee before the petition was lodged, there was nothing to indicate to the trustee that the appellant was able to pay her debts as and when they fell due, and the appellant was legally represented and lodged the debtor’s petition in reliance upon legal advice of her solicitor. Such circumstances do not warrant a conclusion that the debtor’s petition ought not to have been presented within the meaning of s 153B Bankruptcy Act.

95 For these reasons, this aspect of the appeal must fail.

96 As to whether the appellant has established that the debtor’s petition ought not to have been accepted by the Official Receiver, the primary judge stated at [33]–[34] J that:

… [B]y s 55(3AB), the Bankruptcy Act expressly provides that an “Official Receiver is not required to consider in each case whether there is a discretion to reject under subsection (3AA)”. Further, s 55(4) provides that the “Official Receiver must accept a debtor’s petition, unless the Official Receiver rejects it under this section or is directed by the Court to reject it”. There were no features of the “Bankruptcy Form” which obliged an Official Receiver not to accept it, only some features which, as a matter of discretion, might have warranted rejection as a matter of discretion, or at least the seeking of further particulars from Ms Thompson. Given s 55(3AB) and however much there may be cause for dismay in relation to what this case has revealed in relation to contemporary debtor’s petition law and practice, I do not consider this to be a case where a debtor’s petition “ought not to have been accepted” in terms of s 153B. The standard posited by that section is not met where, as a matter of discretion, a petition might not be accepted by an Official Receiver but where there is no obligation to exercise that discretion.

There are no features of the Bankruptcy Form which precluded Ms Thompson from presenting the debtor’s petition nor which obliged the Official Receiver not to accept it. It was apparent on the face of the Bankruptcy Form that Ms Thompson had the requisite Australian association. There was an accompanying statement of affairs.

97 The appellant did not make any submissions about why there was an error in the primary judge’s reasons, and no error was otherwise demonstrated. This aspect of the appeal must also fail.

98 The consequence of these conclusions is that the primary judge’s discretion to annul the bankruptcy did not arise. For this reason alone, the appeal should be dismissed.

WHETHER APPELLANT MADE FULL DISCLOSURE OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS

99 It is well-established that an applicant who seeks an annulment of his or her bankruptcy pursuant to s 153B Bankruptcy Act carries a heavy burden. It is incumbent on such an applicant to place before the Court all relevant material with respect to his or her financial affairs so that the Court may be properly informed and may make a judgment that is based on the actual circumstances of the applicant. Whether an applicant has done this is a relevant factor when determining whether to exercise the discretion: see Francis v Eggleston Mitchell Lawyers Pty Ltd (2014) 12 ABC(NS) 25; [2014] FCAFC 18 (Rares, Flick and Bromberg JJ) at [16] in which the Full Court cited the decision of Tracey J in Alfio Peter Bulic v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Limited (2007) 5 ABC(NS) 122; [2007] FCA 307 at [12]; see also [11(b)] and [12] J.

100 As the primary judge observed at [12] J (which is not challenged by the appellant):

… [A]n applicant must be completely candid. An apparent absence of candour, especially where it suggests that an applicant’s true present financial position may not be one of solvency, or may be much worse than asserted, may well offer a basis upon which to exercise a discretion so as not to annul a subsisting bankruptcy.

101 One of the reasons given by the primary judge for refusing to make the annulment order was the appellant’s non-compliance with s 77 Bankruptcy Act, stating at [86] J that:

… Another factor is Mr Lane’s report in his affidavit that, despite numerous requests of her by him to comply with s 77 of the Bankruptcy Act regarding the provision of her books and records, Ms Thompson has failed to do so, though acknowledging that she holds books and records. I accept Mr Lane’s evidence on this subject. Ms Thompson’s stance, evident in her evidence and submissions, has been to request that Mr Lane advise her as to what documents “we require her to provide”. This inverts the requirements of the Bankruptcy Act and, in any event, Mr Lane has made it plain enough what he requires of her. In my view, this is an additional reason why her bankruptcy ought not to be annulled. There is a public interest, given this conduct, in her remaining subject to the restrictions and duties imposed on a bankrupt by the Bankruptcy Act. Her case is one were [sic] her estate should continue to be administered in insolvency. There is no public interest, and certainly no interest of creditors, served by the annulment of her bankruptcy.

(emphasis added)

102 As to this reason, the appellant’s stated position in her notice of appeal was this:

Par [86] is apparently further confirmation of errors of fact/errors of law noting that absent exhibited evidence, of Morgan Lane’s “numerous requests” or of making his requirements “plain enough”; and evidence of the Applicant’s numerous emails sent to Morgan Lane that have been unanswered; Logan J. has apparently relied upon Morgan Lane’s false/misleading allegations.

In fact, the Appellant/Applicant has identified in numerous emails sent to Morgan Lane that she has not operated a business, has no “books and records” pertaining to the operation of a business (noting same is the usual definition of “books and records” pertaining to s.77 of the Bankruptcy Act), and has genuinely and sincerely asked Morgan Lane to identify what “books and records” he wishes her to provide; noting that the Applicant owns hundreds of fiction and nonfiction books and apparently Morgan Lane does not require her to provide same.

And despite the Bankruptcy Act providing that Morgan Lane must answer the Applicant’s questions, he has failed to answer the Applicant’s genuine, sincere and reasonable questions about what “books and records” he requires the Applicant to provide.

The Appellant/Applicant’s true belief is that there would be as much public interest in the truth of the actions of BCAL, Grace Lawyers and Morgan Lane (not only pertaining to the Appellant/Applicant’s bankrupt estate and lot 3 at Arila Lodge but also pertaining to other litigation commenced against lot owners, other body corporate actions and bankrupt estates) if the public was aware of same.

(emphasis original)

103 In summary, the appellant’s complaint therefore appears to be that the primary judge did not have a proper basis on the evidence to conclude that she had failed to comply with s 77 Bankruptcy Act. The appellant did not submit that such failure, if established, was not relevant to the exercise of discretion under s 153B. Indeed, it is plain that such a matter is relevant having regard to the appellant’s obligation to place before the Court all relevant material with respect to her financial affairs.

104 It is therefore necessary to consider the obligations which the appellant bears pursuant to s 77 Bankruptcy Act and the evidence which was before the primary judge.

105 Section 77 relevantly provides as follows:

(1) A bankrupt shall, unless excused by the trustee or prevented by illness or other sufficient cause:

(a) forthwith after becoming a bankrupt, give to the trustee:

(i) all books … that are in the possession of the bankrupt and relate to any of his or her examinable affairs …

106 Section 5(1) defines “books” as follows:

books includes any account, deed, paper, writing or document and any record of information however compiled, recorded or stored, whether in writing, on microfilm, by electronic process or otherwise.

107 Section 5(1) defines “examinable affairs” as follows:

examinable affairs, in relation to a person, means:

(a) the person’s dealings, transactions, property and affairs; and

(b) the financial affairs of an associated entity of the person, in so far as they are, or appear to be, relevant to the person or to any of his or her conduct, dealings, transactions, property and affairs.

108 Mr Lane gave the following evidence in his affidavit filed 6 May 2021:

Despite numerous requests of the Applicant to comply with Section 77 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 regarding the provision of her books and records, the Applicant has failed to do so, though acknowledging that she holds books and records. Rather the Applicant has requested that I am to advise the Applicant as to what documents “we require her to provide” …

109 Contrary to the notice of appeal, Mr Lane’s affidavit annexed copies of some of the requests made of the appellant.

110 On 27 January 2021, Mr Lane sent an email to the appellant in these terms:

In relation to your attached document, you state: “**All documents referenced and any additional information required can be provided upon request.” Sorry, however I find that statement astounding, because we have asked you on numerous occasions, to provide to this office all the books and records that you have in your possession and you have failed to do so.

So again, and so that there can be no doubt about my position and that of the law; please provide to this office all the books and records in your possession, not just the records that you want to provide, because Section 77(1)(a) of the Act clearly states: Duties of bankrupt as to discovery etc. of property

(1) A bankrupt shall, unless excused by the trustee (and you are not excused) or prevented by illness or other sufficient cause:

(a) forthwith after becoming a bankrupt, give to the trustee:

(i) all books (including books of an associated entity of the bankrupt) that are in the possession of the bankrupt and relate to any of his or her examinable affairs;

(emphasis omitted)

111 On 7 April 2021, Mr Lane sent an email to the appellant which included this statement:

As for your compliance with the Bankruptcy Act, I note you have continued to fail to deliver up all your books and records. I attach a notice issued to you in this regard on 28 October 2020, almost 6 months ago. I suggest to assist in the administration, you comply with this request.

112 On 8 April 2021, the appellant sent an email to Mr Lane which included this statement:

…

3. And can you please confirm what steps you would take if I provided “all your books and records”. Noting that pertaining to “all your books and records” I have previously identified that my understanding (based on legal advice) is that the legal obligation pertains to “books and records” of business(es) I have operated, of which there is none. If you are aware of a relevant legal determination of same then can you please provide it to me.

4. Additionally, noting that I have emailed to you multiple documents explaining the actions of the Body Corporate for Arila Lodge and others who have filed Proof of Debt Claims and the apparent invalidity of same, and have offered to provide any legal documents you require. To date I have received no response from you pertaining to any legal documents you require.

…

113 That same day, Mr Lane wrote to the appellant in these terms:

In relation to the provision of your books and records it is an obligation that is imposed upon you under the Act. As to your understanding, which you say is based on legal advice, I beg to differ as has been previously explained to you (refer my emails of 22/12/20, 23/12/20 and 27/1/21). Sorry you have to comply with the requirements of the Act, it is you that needs to provide written advice as to the alternative.

In your words, you “have offered to provide any legal documents you require”, with respect it is not for you to offer and as advised to you on 27/1/21 in response to your email of 25/1/21, it is your duty to comply with the Act and simply provide.

114 Less than a week later, on 14 April 2021, the appellant filed the annulment application.

115 Although Mr Lane was cross-examined at the hearing before the primary judge, there was no suggestion made to him, and no submission was made by the appellant, that she had provided all books in her possession to Mr Lane which related to her examinable affairs within the meaning of the Bankruptcy Act. Nor did the appellant establish or submit that the position had been rectified through her evidence such that all such books had been provided as required.

116 To the contrary, in this appeal, the appellant seeks to maintain the position adopted by her in correspondence that, as she did not operate a business, she is not required to provide any books, and that, in any event, the onus is upon Mr Lane to identify the books which he requires to be delivered. Such a position is wrong when one has regard to the legislation, including the definitions of “books” and “examinable affairs”. Further, s 77 places the onus on a bankrupt to act as stipulated, and there is no requirement for a trustee in bankruptcy to identify or request particular books from the bankrupt.

117 Contrary to the position of the appellant, there was therefore no error by the primary judge in accepting the evidence of Mr Lane and finding that the appellant had failed to provide the books which she was required to provide to him pursuant to s 77 Bankruptcy Act.

118 Further, the obligation placed upon a bankrupt by s 77(1)(a) is a significant and serious one, as s 265 Bankruptcy Act makes plain. In this regard, the observations of Sheppard J in Re Bond; Ex parte Ramsay [1994] FCA 1052; (1994) 54 FCR 394 at 401 are apposite:

… The provisions of s 77 and the other provisions of Part V of the Act are designed to enable the Trustee to make the fullest investigation into a bankrupt’s property, dealings and affairs. At least so far as bankrupts are concerned, the essence is a requirement that they cooperate. Co-operation can and will be compelled in appropriate cases. If this were not the case, bankrupts could make a laughing stock of their obligations. Thus unwilling and uncooperative bankrupts must produce documents and answer questions against their will. That is their obligation. If they fail in that obligation they expose themselves to the risk of being found in contempt of court or in breach of the criminal law. To require Mr Bond to sign the consent here in question is, in my opinion, an ordinary and commonplace incident of his overall obligation to co-operate with his Trustee. He is required to do many things that he is probably unwilling to do. This is but one of them …

119 The conduct of the bankrupt is a relevant consideration in determining whether an order annulling a bankruptcy should be made, as is whether an annulment will be conducive of or detrimental to commercial morality and the interests of the public: Shaw at [112].

120 For these reasons, I agree with the primary judge that there is a public interest, given her conduct, in the appellant remaining subject to the restrictions and duties imposed on a bankrupt by the Bankruptcy Act and that her estate should continue to be administered in insolvency. I also agree that there is no public interest served by the annulment of the appellant’s bankruptcy.

121 The primary judge was therefore justified in treating the appellant’s non-compliance with s 77 Bankruptcy Act as providing an additional reason why the appellant’s bankruptcy ought not to be annulled.

122 Importantly, it was in the context of the appellant’s non-compliance with her statutory obligations that the primary judge considered the appellant’s central contention in support of annulment, being that she was solvent when the debtor’s petition was presented and that she would be able to pay her debts as and when they fell due if her bankruptcy was annulled.

123 In circumstances where the appellant failed to deliver books to Mr Lane in compliance with s 77 Bankruptcy Act, and Mr Lane could therefore only opine to the appellant’s financial position based on the information known to him (which was incomplete), the appellant failed to present her complete financial position to the Court.

124 In these circumstances, the primary judge was not properly informed and was therefore unable to make a judgment that was based on the actual circumstances of the appellant.

125 For these reasons, the appellant did not discharge the heavy burden which was imposed on her as referred to by the Full Court in Francis. This provides a second reason in and of itself to dismiss the appeal.

WHETHER APPELLANT DEMONSTRATED SOLVENCY

126 This aspect of my reasons proceeds on the assumption that the appellant placed before the primary judge all relevant material with respect to her financial affairs.

127 The central argument by the appellant before the primary judge was that she was solvent when she presented her debtor’s petition, and that (in effect) she would be solvent if the bankruptcy was annulled. This argument was relied upon by the appellant for the purposes of seeking a finding that the debtor’s petition should not have been presented or accepted (at least in part) as well as to support the exercise of discretion in favour of annulment.

128 As part of consideration of this central argument, the primary judge set out ss 5(2) and 5(3) Bankruptcy Act at [20] J and stated at [82] J that, “in terms of determining solvency, monies which a debtor might readily command by way of loan funds in order to meet debts are to be taken into account”.

129 At [71] – [72] J, the primary judge also made the following observations:

Annulment does not affect sales and dispositions of property and payments duly made and acts done, by the bankrupt’s trustee, or any person acting under the authority of the trustee or the Court, before the annulment: s 154(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. Further, a trustee is entitled to be reimbursed in respect of costs of administration out of property which on bankruptcy vested in the trustee: s 154(1)(b) and s 154(2). Subject to this and to other exceptions in s 154 not presently relevant, the effect of annulment is that the remainder (if any) of the property of the former bankrupt still vested in the trustee reverts to the bankrupt: s 154(1)(c) of the Bankruptcy Act.

Thus, deciding whether or not to annul a bankruptcy may also affect the rights and interests of each of a bankrupt’s creditors in being paid their debts in full. If a person remains in bankruptcy, the rights of unsecured creditors (or secured creditors with a deficiency) become rights to prove in the bankruptcy and to receive such distribution as may be payable to them from the property of the bankrupt in accordance with the Bankruptcy Act. Annulment could therefore bring with it for creditors a right to have payment in full. One reason for annulment might be that in truth and reality there is no particular debt or debts such that a person is not presently and never was insolvent.

130 At the hearing before the primary judge and in order to demonstrate her solvency, the appellant produced a summary table, which was accepted for filing on 1 September 2021.

131 Having regard to the grounds of appeal, the appellant failed to establish any error in the primary judge’s rejection of her central argument. This is for the following reasons.

Evidence before the primary judge

132 Mr Lane’s evidence before the primary judge was as follows (in summary):

(1) the administration is to-date without funds, apart from a refund received in the amount of $930.00;

(2) Mr Lane has received proofs of debt totalling $1,146,213 from creditors, with the largest being the body corporate in the amount of $820,479;

(3) no determination has been made concerning the proofs of debt because no dividend has been gained;

(4) Mr Lane has received copies of orders of the Federal Circuit Court whereby it was ordered that the body corporate’s costs in two proceedings (including the proceedings pursuant to its creditor’s petition) be paid with the same priority as if a sequestration order had been made against the appellant;

(5) the mortgagee of the Hawthorne property has sold that property by public auction. On the best information available to Mr Lane, he estimates that there may be surplus proceeds from the Hawthorne property for the benefit of the administration of at least $348,750.00;

(6) Mr Lane has obtained desktop appraisals of the Arila Lodge unit which is estimated to be valued between $645,000 and $760,000. The body corporate has made a claim that the outstanding levies, penalty interest and recovery costs totalling $549,711.49 are amounts owing on the unit to be paid at settlement of the sale of the unit, which has a similar effect to that of a secured debt;

(7) Mr Lane has not identified any other avenues of recovery for the benefit of the bankrupt estate;

(8) Mr Lane has not seen and the appellant has not produced any evidence that the Hawthorne and Toowong properties were readily realisable as at the date of her bankruptcy and nor has he seen any evidence that the appellant had any liquid funds available to pay her debts at that time. In his opinion, the appellant was insolvent as at 1 July 2020;

(9) Mr Lane has incurred costs and outlays totalling $192,455.71 and has only been reimbursed $691.24 of that sum. This figure does not include the legal costs associated with appearing at first instance and in this appeal;

(10) based on the information currently available to Mr Lane and his inquiries to date, the bankrupt estate is not solvent with the value of creditor claims exceeding the estimated recoveries in the administration;

(11) Mr Lane estimated that the likely return to unsecured creditors would be between $0.17 and $0.4241 in the dollar.

133 No expert evidence was adduced by the appellant to contradict Mr Lane’s evidence. Under cross-examination below, Mr Lane maintained the position that, based on the figures currently available, he was not satisfied that the appellant’s bankrupt estate was solvent.

134 The primary judge agreed. At [84] J, his Honour stated:

On the evidence, by the time when she signed her Bankruptcy Form on 26 June 2020 and when, shortly thereafter, the debtor’s petition portion thereof was accepted by an Official Receiver, Ms Thompson had already defaulted on borrowings from Suncorp Bank such that it had entered into possession of the Hawthorne Property. She was by then subject to multiple costs orders even the fixed components of which were, in the main, unpaid and she was greatly in arrears in amounts owed to BCAL. Her income was insufficient to meet even those debts. She was unable within any reasonable time, or even on the evidence at all, to borrow funds even to meet the amount specified in the bankruptcy notice. Even on a generous assessment of the equity she had in the Hawthorne Property and even assuming, also generously, that each of that property and the Toowong Unit might then have been sold within a reasonable time thereafter, the proceeds of sale would have been insufficient to meet her debts. She has certainly not proved otherwise. Even accepting, in light of s 153B(2) that an annulment order might be made even though she was insolvent when her debtor’s petition was presented, neither has she proved that the position is any better at present. …

135 For the following reasons and by reference to the grounds of appeal, the appellant failed to demonstrate error by the primary judge in relation to these findings.

Errors alleged by appellant

136 The appellant asserts that the primary judge erred in relying on and accepting Mr Lane’s evidence as to solvency.

137 In relation to the debts claimed by creditors, the following specific errors are alleged in the notice of appeal:

(1) the primary judge erred in refusing to go behind the costs orders made in various proceedings between the appellant and the body corporate. As part of this complaint, it is contended to the effect that the primary judge erred as a matter of law in relation to certain findings in [78]–[79] J;