Federal Court of Australia

Ixom Operations Pty Ltd v Blue One Shipping SA [2023] FCAFC 25

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent LS-NIKKO COPPER INC Second Respondent CS MARINE CO LTD | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 A critical question that invariably arises for a shipper or consignee when suing on a bill of lading contract is: “Who is the carrier?” That question can arise in different contexts. First, the question is often put as: “Is it a charterer’s bill, or is it an owner’s bill?” – ie, is the charterer or the owner the contractual carrier? That question most obviously arises in circumstances where the vessel is time-chartered or voyage-chartered. It must therefore be ascertained whether the time or voyage charterer is the carrier under the bill of lading contract, or whether the “owner” is the carrier. Secondly, once it is ascertained that the bill of lading is an “owner’s bill”, then the question becomes whether the vessel was demise-chartered at the relevant time. That is because if it was demise-chartered, then in signing the bill of lading for “owners” the Master or other agent would have been employed by and would have signed the bill of lading for the demise charterer (ie, the disponent owner), and not the registered owner.

2 The present case presents as an example of the second scenario. That is, there was never any suggestion that the bill of lading was a “charterer’s bill” in the sense that it was issued by or on behalf of a time or voyage charterer. The bill of lading was on its face signed by the Master and could only be understood to be, in the first sense identified above, an “owner’s bill”. However, the vessel was demise-chartered with the consequence that the Master signed the bill for the demise charterer as carrier and not for the registered owner. Not knowing or appreciating that, the solicitor acting for the consignee erroneously issued proceedings against the registered owner and not against the demise charterer. By the time he became aware of that error, a time bar had intervened to prevent suit against the demise charterer. To avoid that consequence, the consignee pleaded various estoppels and a misleading and deceptive conduct case which were decided as separate questions before any other questions of liability.

3 After a trial lasting several days, the consignee’s pleaded estoppels and misleading and deceptive conduct case were rejected by the primary judge: Ixom Operations Pty Ltd v Blue One Shipping SA [2022] FCA 1101 (J). In consequence, the proceeding was dismissed with costs.

4 The consignee appealed from the primary judge’s orders. At the conclusion of the hearing of the appeal, we dismissed the appeal with costs. Our reasons for making those orders follow.

Background

5 At all relevant times, the registered owner of the motor tanker CS Onsan was Blue One Shipping SA of Panama and the vessel was demise-chartered to CS Marine Co Ltd of Korea. CS Marine voyage-chartered the vessel to Trammo Navigation Pte Ltd on an amended ASBATANKVOY tanker voyage charterparty form for the carriage of a cargo of sulphuric acid from Onsan, Korea, to Gladstone, Queensland.

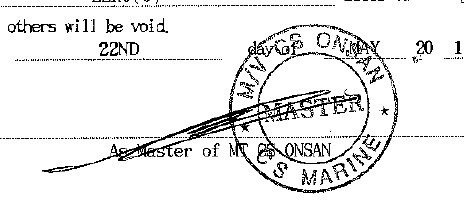

6 Trammo had sold the cargo of sulphuric acid on CFR (cost and freight) terms to Ixom Operations Pty Ltd in Australia. A non-negotiable tanker bill of lading dated 22 May 2017 was issued to Trammo as shipper. It named Ixom as consignee. It was signed by the Master of the vessel and stamped with the Master’s seal reflecting “M/V CS ONSAN – CS MARINE”:

7 One might have thought that that made it abundantly clear that the Master signed the bill of lading on behalf of an entity called, or trading by the name of, “CS Marine”. Ex facie the bill of lading, the entity going by the name CS Marine was unambiguously the carrier.

8 After the vessel arrived at Gladstone on 6 June 2017, Ixom complained that the cargo was contaminated. That in turn gave rise to the following events.

Solicitors were appointed

9 Mr Tulloch, of the solicitors’ firm Colin Biggers & Paisley, was appointed by and acted for Ixom.

10 Mr Hunt, of the solicitors’ firm Mills Oakley, was appointed and acted for Vero Insurance, Ixom’s cargo insurer. As will be seen, after Vero paid Ixom’s claim for its insured losses, Mr Hunt took over the pursuit of any claim for cargo damage in Ixom’s name under subrogated rights.

11 Mr Hockaday, of the solicitors’ firm Thynne + Macartney, was appointed and acted for Blue One and CS Marine on the instructions of The Japan Ship Owners’ Mutual Protection & Indemnity Association (Japan P&I) with which both Blue One and CS Marine were entered as members.

The inter-solicitor correspondence

12 Shortly after being appointed, Mr Tulloch noted that the voyage charterparty named CS Marine as “Owner” and that the bill of lading was signed by the Master under the seal of CS Marine. As Mr Tulloch did not know whether the vessel was demise-chartered, in writing to the vessel’s agent in Gladstone on 15 June 2017 he demanded security for Ixom from the “owners/demise charterers” of the vessel. (J[51]-[53].)

13 On 16 June 2017, Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday had a conversation in which the latter said that he acted for “owners”. Later that day, in an email to Mr Tulloch, Mr Hockaday confirmed that he acted on behalf of “vessel interests”. (J[54], [56].)

14 On 20 June 2017, Mr Hockaday said in an email to Mr Tulloch that “CS Marine Co Ltd, the demise charterer of the vessel”, undertook to give 24 hours’ notice of any intended departure of the vessel from Gladstone. Attached to the email was a signed letter of undertaking on the letterhead of CS Marine which stated that “CS Marine Co Ltd, on behalf of the owners and demise charterers of the vessel ‘CS Onsan’” gave the undertaking. (J[60]-[62].)

15 On 21 June 2017, Mr Tulloch put a proposal to Mr Hockaday’s “clients” by which Mr Tulloch sought security for any claim for cargo damage from, and agreement with regard to the conditions of discharge of the cargo with, “the vessel owner/demise charterer” (J[65]). On the same day, Mr Hockaday wrote that his “client” was prepared to provide the requested security and agree to the conditions of discharge and attached draft wording of a letter of undertaking (LOU) by Japan P&I. An LOU in the terms of the draft by Japan P&I dated 22 June 2017 was subsequently provided and accepted (J[70]). The LOU gave an undertaking “on behalf of the owners or demise charterers of the Vessel” to Ixom “as the consignee of the above bill of lading” (J[67]).

16 Although he had previously been in contact with Mr Tulloch, Mr Hunt first wrote to Mr Hockaday on 7 July 2017. At that time, Mr Hunt had a copy of the bill of lading, but not the voyage charterparty (J[72]). As mentioned, the bill of lading indicated that CS Marine was the carrier.

17 On 21 July 2017, Mr Hunt wrote to Mr Hockaday requesting security for the claim in relation to contamination of cargo, but Mr Hockaday referred him to Mr Tulloch because security had already been provided. Mr Hunt was then furnished by Mr Tulloch with a copy of the Japan P&I LOU which mentioned both the owner and demise charterer. (J[74]-[75].)

18 It was at all times common ground that the Australian Hague Visby Rules in Sch 1A to the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act 1991 (Cth) applied to any claim under the bill of lading. That had the result that, by Art 3(6), “the carrier and the ship” would be discharged from all liability whatsoever in respect of the goods unless suit was brought within one year of their delivery or the date when they should have been delivered. That is to say, unless a relevant extension of time was given, any claim against the carrier (which is defined by Art 1(1)(a) as including the owner or the charterer who enters into a contract of carriage with the shipper) or the ship had to be brought by commencing suit before about 6 June 2018.

19 On 22 May 2018, Mr Hunt wrote to Mr Tulloch noting that the claim would become time-barred as early as 6 June 2018 in the absence of a time extension from “owners/carriers”. He asked Mr Tulloch to ask “owners/carriers lawyers” for a three-month extension. At that time, Mr Tulloch still considered that the carrier was CS Marine but he said that he did not know whether CS Marine was the registered owner or a demise charterer (J[78]-[79]). That was despite having been told by Mr Hockaday in writing on 20 June 2017 that CS Marine was the demise charterer (see [14] above).

20 On 23 May 2018, Mr Tulloch wrote to Mr Hockaday saying that he was concerned about the approaching time bar and asked that Mr Hockaday “confirm that owners are prepared to grant a three month extension of the time bar for claims for damage and/or demurrage under the [referenced] bill of lading” (emphasis added). (J[81].)

21 On 25 May 2018, after having obtained instructions from CS Marine (through its insurance broker Aon) and Japan P&I, Mr Hockaday replied advising that “our client” agrees to provide an extension of the limitation period to 31 August 2018 “for any claims for damage and/or demurrage under the said bill of lading”. (J[83]-[87].)

22 Over the following weeks, Vero decided to indemnify Ixom and instructed Mr Hunt to pursue its subrogated rights against the carrier. Mr Tulloch dropped out of the discussions with Mr Hockaday. (J[89].)

23 Further extensions of time were sought from time to time by Mr Hunt and granted by Mr Hockaday on the same terms as the 25 May 2018 extension, with the final extension being until 28 November 2020 (J[90]-[106]). Suit accordingly had to be brought before that date.

24 Along the way, on 22 October 2019, accepting a request from Mr Hunt, Mr Hockaday confirmed that “we, owners (CS Marine) and its insurer (Japan P&I)” agreed to provide an undertaking to keep certain information confidential and not to disclose it except in the context of Mr Hunt’s client’s claim. That was consequently an indication directly to Mr Hunt that the relevant carrier party was CS Marine. (J[101]-[102].)

The proceeding below

25 On 26 November 2020 – two days before the latest extension expired – Mr Hunt commenced a proceeding in the name of Ixom as plaintiff against Blue One as the first defendant for damages in the sum of $1,751,709 plus interest and costs. Another party was named as second defendant, but there was never any service on it and it played no further role in the proceeding. (J[108].)

26 Ixom pleaded claims in contract based on the bill of lading, and in bailment and negligence. The claims could not therefore succeed unless Blue One was the contractual carrier (in the case of the claim on the bill of lading contract) or the person in possession and control of the vessel (in the case of the bailment and negligence claims). Since it was neither, the claims were doomed to fail.

27 Blue One filed a defence on 2 February 2021 in which it denied that it was the carrier under the bill of lading and named CS Marine as the carrier and demise charterer. Although Ixom thereafter joined CS Marine as third defendant, that was long after the last extension of time had expired, giving CS Marine a complete defence to the claim against it.

28 To get around CS Marine’s time-bar defence, Ixom pleaded six different estoppels in reply to the defences which were ultimately apparently reduced to three. They were identified by the primary judge to be as follows, noting that no point is taken in the appeal in relation to the primary judge’s framing of the different estoppels.

29 Ixom pleaded a first estoppel, namely that by the exchange of correspondence on 23 and 25 May 2018 between the solicitors, Blue One and CS Marine purported to give an extension of the limitation period in a misleading way by representing that Blue One, as owner, was a party to the bill of lading contract. Ixom pleaded that Blue One knew that the plaintiff was relying on the 25 May 2018 email and that the plaintiff assumed and understood that Blue One was a party to the bill of lading contract. On that basis, it was said that the defendants are estopped from denying that that is so. (J[42].)

30 Ixom pleaded a second estoppel, namely that the plaintiff was induced to rely on an assumption that Blue One was the carrier under the bill of lading contract, which assumption was created by the 25 May 2018 email because it purported to give an extension of the limitation period without referring to the demise charterer. Ixom pleaded that in reliance on that mutual assumption, the plaintiff did not seek an extension of time from, or commence proceedings against, CS Marine. On that basis, it was said that Blue One is estopped from denying that it was and is a party to the bill of lading contract. (J[43].)

31 Ixom pleaded a third estoppel, namely that the 25 May 2018 email misrepresented the parties to the bill of lading contract because it purported to give an extension of the limitation period by the registered owner only without referring to the demise charterer. It is said that the plaintiff relied on that representation in not seeking an extension of time from, or commencing proceedings against, the demise charterer, and that it would be unconscionable for the defendants to depart from the representation. On that basis it is said that the defendants are estopped from denying that Blue One is a party to the bill of lading contract. (J[44].) It is to be observed that that is a straight-forward estoppel by representation that does not depend on establishing any induced or mutual assumption as to a state of affairs.

32 Ixom also pleaded that Blue One and CS Marine engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Mr Hockaday’s email on 25 May 2018 that agreed to the first extension of time, and in the subsequent extensions of time. It pleaded that the email misrepresented that Blue One, as the vessel owner, was a party to the bill of lading contract and that the consent of Blue One was sufficient to provide an extension to the time bar, as a result of which Ixom did not seek an extension from CS Marine. (J[45].)

33 Arising from those pleaded cases, and putting to one side the contributory negligence case pleaded by Blue One and CS Marine in response to the ACL claim, three separate questions were framed for determination at the initial trial. They were whether any representation in Mr Hockaday’s email of 25 May 2018 gave rise to:

(1) an estoppel preventing Blue One from denying that it is a party to the bill of lading contract;

(2) an estoppel preventing CS Marine relying on the time bar in Art 3(6) of the Australian Rules; or

(3) liability to compensate Ixom by reason of Blue One having engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

34 As mentioned, the primary judge answered each of those questions in the negative. It is to be observed that the second question could never have been affirmatively answered because none of the three identified estoppels go to that question; none of them say that CS Marine is estopped from relying on the time bar. They are all directed at estopping Blue One from denying that it is a carrier under the bill of lading contract.

The primary judge’s reasons

35 The primary judge referred to the uses by Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday of the different terms “owners”, “vessel interests” and “owners/demise charterers” in their early communications, as identified above at [12]-[15], and found that both Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday understood that Mr Hockaday acted for both the registered owner of the vessel and also for the bareboat charterer (J[141]). Also, from 20 June 2017 when Mr Hockaday referred to CS Marine as demise charterer of the vessel (see [14] above), Mr Tulloch (and thereby Ixom) was aware that Mr Hockaday represented both the registered owner and CS Marine as demise charterer (J[142]).

36 The primary judge found that the meaning of a particular reference to “owner” will be context-driven and can mean the registered owner or a demise charterer. His Honour found that that was known to both Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday and that it would be understood by a reasonable recipient of the relevant communications between the parties. (J[140].)

37 With respect to Mr Tulloch’s request for security for the claim in June 2017 and Mr Hockaday’s response to that request (referred to at [15] above), the primary judge found that they had a mutual understanding that they were endeavouring to ensure that an interim agreement was reached to protect, respectively, Ixom’s position insofar as it had any claim in respect of the consignment against the carrier under the bill of lading, and the vessel interests’ position in securing the discharge of the cargo so that the vessel could meet its next fixture. His Honour found that that position had not changed by 25 May 2018. (J[141].)

38 Given that finding, and other aspects of the context referred to, the primary judge concluded that Mr Tulloch’s request for an extension of time from “owners” on 23 May 2018 conveyed, at a minimum, that an extension was sought from “the party who could meaningfully grant an extension of the potential claims identified, being the disponent owner of the vessel who was the carrier under the contract evidenced by the bill of lading” (J[145]). His Honour found that Mr Tulloch knew at that time that Mr Hockaday acted for both the registered owner and CS Marine, and that Mr Tulloch’s request for an extension of time was intended to be, and was, a broad request to protect Ixom’s interests “consistent with communications that passed between the parties in June 2017” (J[146]).

39 His Honour found that objectively, viewed in the light of the previous communications, Mr Hockaday by his email on 25 May 2018 communicated that the extension sought from the registered owner and CS Marine was being granted (J[148]). His Honour found that both parties proceeded on the basis that Mr Hockaday’s two clients provided their agreement to that which would maintain the status quo by ensuring that such claim as Ixom sought to bring in respect of the consignment would not be time-barred (J[149]).

40 In respect of the first estoppel, the primary judge rejected the contention that the 25 May 2018 email represented that the registered owner was a party to the bill of lading contract. Instead, his Honour found that to a reasonable reader, in context, the 25 May 2018 email represented no more than whichever of Mr Hockaday’s clients was legally able to grant an extension of the time bar had done so. It was found that a reasonable recipient of the 25 May 2018 email would have understood it to mean that Ixom got what it sought, namely an extension of the limitation period for any claims for damages and/or demurrage under the bill of lading, whether such claims were to be made against the registered owner or CS Marine. (J[150]-[151].)

41 To interpolate, it is to be observed that the primary judge found that the extension was granted by both Blue One and CS Marine to maintain the status quo (J[148]-[149]), and that the 25 May 2018 email did no more than to represent that whichever of Blue One or CS Marine was legally able to grant an extension of time bar had done so (J[150]). That is to say, the agreement (contract) to extend time was between Ixom on the one side and both Blue One and CS Marine on the other, with both of the latter granting an extension. However, insofar as any representation was made about the identity of the carrier by the terms of what was agreed taken in context, it was no more than that whichever one of Blue One or CS Marine was the carrier, it granted an extension. The notion that there was a representation that a party was the carrier when in truth it was not was rejected.

42 The primary judge noted, and apparently accepted, Mr Hunt’s evidence that when he received a copy of the correspondence of 23 and 25 May 2018 between Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday he understood that an extension of time had been requested from and granted by only the registered owner of the vessel. His Honour noted that that was different from Mr Tulloch’s understanding and that Mr Hunt did not at that time have a copy of all that had passed between Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday, including a copy of the voyage charterparty; Mr Hunt’s view was not formed in the context of the earlier communications that had passed between the parties. At that time, Mr Hunt considered that it was Mr Tulloch’s role to seek a time extension from the appropriate party, that it was inappropriate for him to become involved in that and that he did not seek to place himself in Mr Tulloch’s position. (J[152]-[154].)

43 The primary judge rejected the contention that the defendants knew that Ixom’s representatives were operating under an incorrect assumption in seeking an extension from Blue One, being the wrong party. His Honour offered a number of reasons for that conclusion, including that Mr Hockaday said that he did not have that understanding, which his Honour accepted, and that there was nothing to support an inference that anyone else on behalf of the defendants had that understanding. (J[156]-[168].)

44 The primary judge rejected the second estoppel on the basis that the 25 May 2018 email did not purport to give an extension of the limitation period by Blue One alone, and there was no mutual assumption to that effect (J[169]).

45 The primary judge rejected the third estoppel on the bases that the 25 May 2018 email did not misrepresent the parties to the bill of lading contract, the 23 May 2018 email did not expressly or impliedly seek clarification as to the identity of the carrier under the bill of lading, and no unconscionability as pleaded arose (J[170]).

46 The primary judge rejected the ACL claim on the basis that none of the pleaded misrepresentations had been established. His Honour rejected the contention that by the 25 May 2018 email the defendants represented that Blue One was a party to the bill of lading contract (J[172]).

The grounds of appeal

47 Ixom puts its grounds of appeal as follows:

1. That the primary judge was in error in concluding that the Thynne Macartney email of 25 May 2018 granted an extension by both CS Marine and Blue One Shipping for claims under the contract of carriage evidenced by the bill of lading dated 22 May 2017.

2. That the primary judge was in error in concluding that Blue One Shipping was not estopped from denying that it was a party to the contract of carriage evidenced by the bill of lading dated 22 May 2017, either because:

a. The email of 25 May 2018 conveyed the representation that Blue One Shipping alone, as ‘owner’, was giving, and was able to give, the extension, in which case there was a representation that Blue One Shipping was party to the contract of carriage; or

b. Alternatively, as the primary judge found, the email of 25 May 2018 conveyed the representation that both Blue One Shipping and CS Marine were giving, and were able to give, the extension, in which case there was a representation that Blue One Shipping was one of two carrier-side parties to the contract of carriage.

3. That the primary judge was in error in concluding that CS Marine was not estopped from relying on Article 3 rule 6 of the Australian Amended Hague Visby Rules.

4. That the primary judge was in error in finding that the Thynne Macartney email of 25 May 2018 granting an extension for claims under the bill of lading, and later extensions given up to 28 November 2020, was not conduct which may mislead and deceive the appellant contrary to s.18 of the Australian Consumer Law.

48 It is to be observed that grounds of appeal 1, 3 and 4 are addressed at the level of errors of ultimate conclusion by the primary judge and fail to identify any specific errors with regard to why the ultimate conclusions are wrong. In that respect, they do not satisfy the requirement of r 36.01(2)(c) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that the notice of appeal “specifically” identify the grounds of appeal. Also, none of the grounds of appeal identify any purported factual error by the primary judge.

49 Ixom, by its notice of appeal, sought orders that:

(1) Blue One is estopped from denying that it was and is a party to the bill of lading contract;

(2) CS Marine is estopped from relying on Art 3(6) of the Australian Rules; and

(3) Blue One and/or CS Marine engaged in conduct in contravention of s 18 of the ACL in the manner identified at [32] above.

50 As with the second separate question reserved to be answered by the primary judge (at [33(2)] above), there is no possibility that CS Marine could be estopped from relying on a time bar because no estoppel is directed to that issue.

Ixom’s submissions

51 Ixom advanced no submissions in support of appeal ground 1, ie, that the agreement to extend time was not made by both Blue One and CS Marine. Ixom’s submissions only addressed representations (ie, estoppels) and misleading and deceptive conduct. Its submissions on ground 1 proceeded on the assumption that ground 1 covered questions of representation and estoppel, rather than the agreement to extend time.

52 Ixom accepted that the factual findings with respect to the first and second estoppels, which it does not challenge, mean that it cannot challenge on appeal his Honour’s findings that neither of those estoppels is available to it. It therefore confines the appeal to the third estoppel and the ACL claim. It submits that the 25 May 2018 email conveyed a representation that Blue One (as registered owner) granted the extension of time and was therefore a party to the contract of carriage. It is said that that is a simple estoppel by representation not requiring proof of any state of mind on the part of the representor. Ixom submits that the primary judge failed to deal with that estoppel adequately in dismissing it at J[170].

53 In particular, Ixom relies on Pacol Ltd v Trade Line Ltd (The “Henrik Sif”) [1982] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 456 and Air Tahiti Nui Pty Ltd v McKenzie [2009] NSWCA 429; 77 NSWLR 299 and Handley KR, Estoppel by Conduct and Election (2nd ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2016) at [2–017] for the proposition that by granting an extension of time, Blue One represented that it was the carrier.

54 With respect to the primary judge’s conclusion that the 25 May 2018 email conveyed that both Blue One and CS Marine granted the extension of time, Ixom submits that that carries with it the representation that both those parties can give such an extension, ie, that both parties are persons to whom Art 3(6) applies. In that regard, Ixom relies on The “Stolt Loyalty” [1993] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 281 at 287-288, Air Tahiti at [29] and The Starsin [2001] EWCA Civ 56; [2001] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 437 at [70]–[71] for the proposition that there could have been more than one carrier.

55 It is to be noted that whether the extension of time, as a matter of contract or representation, was on behalf of Blue One only or both Blue One and CS Marine is not central to the appeal. The central point in the appeal is Ixom’s contention that by granting an extension of time (on its own or together with CS Marine), Blue One represented to Ixom, or otherwise misled and deceived Ixom into believing, through Mr Hunt, that Blue One was the/a carrier under the bill of lading contract. That is the point to be grappled with.

56 One of the obstacles to Ixom on that point is the primary judge’s finding that Mr Tulloch, to whom on behalf of Ixom the representation was addressed, was not misled by the 25 May 2018 email into believing that the vessel owner was the/a carrier. The primary judge found that Mr Tulloch had the understanding that the extension was sought from and granted by whoever the carrier was in order to maintain the status quo, it being unnecessary to decide at that time who the carrier was.

57 Ixom makes two submissions to avoid that obstacle. First, it submits that those findings are factually incorrect, principally because Mr Tulloch gave evidence that at that time he had forgotten having been told that there was a demise charterer. Secondly, it submits that it is Mr Hunt’s understanding, and not Mr Tulloch’s, that is relevant because it is Mr Hunt who acted on the representation by not suing CS Marine.

58 With regard to its submission that the primary judge made errors in his factual findings, Ixom applied for leave during the hearing of the appeal to amend its notice of appeal by adding a ground expressed as follows:

The primary judge was in error in finding that Mr Tulloch understood that Thynne + Macartney also acted for CS Marine when he asked for and obtained the extension of time on 23 and 25 May 2018 and that it was an error to rely on communications to Mr Tulloch in 2017 which Mr Tulloch had forgotten.

Consideration

59 The problem at the heart of Ixom’s case is its reliance on the subjective understanding, and recollection, of Mr Tulloch and Mr Hunt as informing the construction and nature of what was represented by the relevant emails. That approach is incorrect.

60 A representation must be clear and unambiguous in order to found an estoppel: Legione v Hateley [1983] HCA 11; 152 CLR 406 at 435-6 per Mason and Deane JJ. That requires that the representation be of such a nature that it would have misled any reasonable person in the position of the person to whom it is addressed and that the representee was in fact misled by it: Western Australian Insurance Co Ltd v Dayton [1924] HCA 58; 35 CLR 355 at 375 per Isaacs ACJ, citing Low v Bouverie [1891] 3 Ch 82. Identifying the content of a representation is an objective task that is informed by the context in which the alleged representation takes place as well as the “known characteristics of the actual representee”: MCI WorldCom International Inc v Primus Telecommunications Inc [2004] EWCA Civ 957; [2004] 2 All ER (Comm) 833 at [30] per Mance LJ (Ward LJ and Sir Martin Nourse agreeing). Contrary to Ixom’s submissions in reliance on this passage, the “known characteristics of the actual representee” do not, and cannot, include the subjective understanding, belief or memory of the representee unknown to the representor; “known” here must mean known to the representor, not subsequently known to the court.

61 The purpose underlying the common law principle of estoppel by representation (a form of estoppel in pais) is to avoid or prevent the representee suffering a detriment if the representor were allowed to depart from the assumption conveyed by the representation on which the representee acted: Grundt v Great Boulder Pty Gold Mines Ltd [1937] HCA 58; 59 CLR 641 at 674 per Dixon J. That is why the representation must be so clear and unambiguous that a reasonable person in the position of the parties would have understood it in the sense that, subjectively, the representee asserts that he or she did. It is only if a reasonable person in the representee’s position could have understood the clear and unambiguous representation in the sense that the representee claims that the law will hold the representor bound to adhere to the assumption. Thus, the sense in which a representation is actually understood by the representee is only relevant to the question whether the representation induced the representee to act upon it. That point was made in Krakowski v Eurolynx Properties Ltd [1995] HCA 68; 183 CLR 563 at 576-577 per Brennan, Deane, Gaudron and McHugh JJ in the context of a fraudulent representation, but it applies equally in the case of an estoppel by representation where there is no suggestion of fraud. That is to say, the representee’s subjective state of mind goes to the question of whether they were misled, not to the content of the representation. It is therefore not to the point what Mr Tulloch or Mr Hunt actually understood or remembered in determining what, if any, representation was made by the exchange of emails separate from the terms of the contract that was thereby concluded.

62 In any event, insofar as Ixom sought to challenge the primary judge’s findings regarding Mr Tulloch’s understanding, it is quite clear that those findings are correct. Mr Tulloch’s evidence includes the following:

(1) Before preparing his request for an extension of time on 23 May 2018, he reviewed the bill of lading and the voyage charterparty. It will be recalled that those documents identified that CS Marine was the “owner” (ie, disponent owner) which voyage-chartered the vessel to Trammo and that the Master signed the bill of lading on behalf of CS Marine.

(2) At that time, he considered that CS Marine was likely to be the contracting carrier under the bill of lading.

(3) Also at that time, he did not know whether CS Marine was the registered owner, and used the terminology “owners” in his correspondence to refer to the carrier under the bill of lading contract.

(4) He was satisfied on receipt of the email of 25 May 2018 that he had obtained from the contracting carrier (whom he thought was likely to be CS Marine) an extension of time to bring any claim under the contract of carriage.

(5) Whether CS Marine or the vessel’s owner was the party liable under the bill of lading was not something that particularly concerned him at that time – it was an issue that ultimately needed to be resolved if proceedings were commenced but in his view he had been granted an extension of time by the carrier under the bill of lading.

(6) He was seeking an extension of time from the carrier under bill of lading, but had no recollection at that time of having been told that CS Marine was the demise charterer.

63 In the light of that evidence, there is no foundation at all to the submission that Mr Tulloch understood that he had secured an extension of time only from the registered owner which was the carrier. Even though he had forgotten that he had been told that CS Marine was the demise charterer, he still did not understand that he had been given an extension of time only from the registered owner or that the registered owner was the carrier. Ixom’s case in that regard must fail, making it unnecessary to consider its application to amend the notice of appeal.

64 Turning then to the contention that it is Mr Hunt’s understanding of the representation that is relevant, rather than Mr Tulloch’s, on the primary judge’s findings Mr Hunt’s (mis)understanding was not “known”, and could not have been expected to be known, to Mr Hockaday. It is therefore irrelevant to the question of what was represented.

65 Mr Hunt’s actual (mis)understanding, as explained, does not go to the content of the representation or any role that Mr Hockaday or CS Marine played in making it but to Mr Hunt’s reliance on his understanding. It was unreasonable for him to construe the representation as being a representation that only the registered owner had granted an extension (and thus that it was the carrier) in circumstances where he failed to ascertain the proper context in which the representation was made by obtaining copies of the prior communications between Mr Tulloch and Mr Hockaday.

66 But more to the point, Ixom submits that it (through Mr Hunt) understood the 23 and 25 May 2018 emails to say not only that the extension was granted only by the registered owner, but that the registered owner was the carrier. It is immediately to be observed that that is an implication that it is said that Mr Hunt drew and not something that was stated clearly and unambiguously. Further, in circumstances where he had in his possession the other relevant contractual documents, namely the bill of lading on which he intended to sue, the LOU and the agreement to keep information confidential, all of which gave clear indications to the contrary, that understanding was unreasonable and could not be expected to be the understanding of a reasonable representee. As mentioned, the bill of lading indicated that “CS Marine” was the carrier, and the confidentiality agreement, which Mr Hunt had himself struck, recorded “owners” to be CS Marine. The LOU spoke of both the registered owner and the demise charterer and it was given by Japan P&I, which explains the reference in Mr Hockaday’s email of 25 May 2018 to “our client” (in the singular) agreeing to the extension of time.

67 There is therefore no sense in which the exchange of correspondence on 23 and 25 May 2018 by which an extension of time was agreed, judged objectively according to the impact that what was said may be expected to have on a reasonable representee in the position and with the known characteristics of the actual representee, could be reasonably understood to say that the registered owner was the contractual carrier. Nor was Mr Hunt’s understanding of it reasonable.

68 Turning now to the authorities on which Ixom relies in its contention that there is some principle of law that necessitates that implication, neither The Henrik Sif nor Air Tahiti assist. In each case, unlike in the present case, the plaintiff had assumed that one entity was the relevant party liable under a contract of carriage and the defendant’s conduct served to only encourage that assumption and induce the plaintiff into believing that the entity was a proper party. The findings in each case were based upon the defendant’s conduct construed in the particular circumstances, and from which representations were conveyed that the relevant defendant was the proper party: see The Henrik Sif at 463-466 and Air Tahiti at [88]-[91]. Neither case purports to assert any legal principle that a person who agrees to extend a time-bar to bring proceedings for breach of contract necessarily represents that they are a party to the contract. Indeed, even a cursory review of those cases reveals that their factual circumstances are very different.

69 The passage in Handley at [2–017] referred to by Ixom deals with representations made by the exercise or assertion of rights. It cites Grundt at 676 where Dixon J explained that a person may be required to abide an assumption “because he has exercised against the other party rights which would exist only if the assumption were correct”. Neither that case, nor any other cases in the passage, support the proposition contended for by Ixom. That is because there is nothing in granting an extension of time to bring a claim in the circumstances of the present case which makes any representation as to the identity of the carrier. Indeed, as found by the primary judge, the extension of time was sought and granted in order to preserve the status quo and avoid the need at that time to identify the carrier. There was no assertion or reliance on any right by Blue One in granting the extension, and in doing so it did not mislead; for a prospective defendant to agree to extend time is not to assert or rely on a right, it is to disclaim any such reliance for the agreed period of time.

70 Finally, there is the contention by Ixom that by both Blue One and CS Marine granting the extension they represented that they were both carriers under the bill of lading. That contention fails for the same reason as already dealt with on the hypothesis that the extension was given only for the registered owner. Further, just because it is theoretically possible to have two contractual carriers on the same contract of carriage does not mean that that representation was made in the present case. It is such an unusual, and only really a theoretical, possibility that there could have been no representation to that effect, and Mr Hunt did not say that he understood there to be one. Aside from anything else, there is no evidence of reliance on it.

71 With regard to the authorities relied on by Ixom, Air Tahiti at [29] does no more than refer to the discussion by Rix LJ in The Starsin at [70]-[76]. There it was said that although the possibility of both the charterer and the owner being liable on a bill of lading had been recognised, no case had so decided. In any event, the basis of that hypothesised liability was not that both were carriers; rather it was on the basis of an owner issuing bills of lading as agent for the charterer (which is common under a time charter but is hard to image under a demise charter) but doing so without identifying the charterer. In those circumstances, the owner could become liable on the bills of lading as agent for an undisclosed principal. That circumstance is far removed from the present and offers no support to Ixom’s case.

72 The academic commentary relied on by Ixom for the proposition that both the owner and the charterer can, as a legal possibility, together have obligations to the bill of lading holder as carrier are based on United States cases in its unique statutory context and deal with the time charterer and the owner (or demise charterer), not the demise charterer and the owner. See Davies M and Dickey A, Shipping Law (4th ed, LawBook, 2016) at [12.810] and Rose F and Reynolds FMB, Carver on Bills of Lading (5th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2022) at [4-033].

73 Ixom also relies on a passage in The Stolt Loyalty at first instance. In that case, the facts were remarkably similar to the present in that the plaintiff sought and was granted an extension of time from “owners” even though in prior correspondence it had been made aware that there was a demise charterer that was almost certainly the carrier and the proper defendant. As in the present case, it was held by Clarke J that the extension of time was given by both the demise charterer and the owner. There were a number of considerations that led to that conclusion including the common usage of the word “owners” as covering both demise charterer and owner and because it would have made no commercial sense for the plaintiff to have sought an extension of time only from the registered owner in circumstances where it had information which showed that the likely proper defendant was the demise charterer (at 286-288).

74 Because of that conclusion, it was unnecessary to consider the plaintiff’s alternative estoppel claims which would have arisen only if the defendants’ contention that the extension of time had been given only by the registered owner had been upheld. The claimed estoppels were, first, that the demise charterer was estopped from relying on the time bar and, second, that the registered owner was estopped from denying that it was the proper defendant. The critical difference between that case and the present is that there the plaintiff commenced proceedings against both the demise charterer and the registered owner but was met with the defence that the claim against the demise charterer was out of time because the extension had been granted only on behalf of the owner.

75 Clarke J nevertheless considered the first estoppel claim in case he was found to be wrong on the construction of “owners”. The estoppel case therefore proceeded on the premise, which his Lordship had rejected, that “owners” (in the telex exchanges construed objectively in their context and against surrounding circumstances – at 284 and 288) had conveyed that only the registered owners had granted an extension of time (at 288). The reason why Clarke J would have upheld the case was that the P&I Club that granted the extension of time was “virtually certain” that the plaintiff’s solicitor, in seeking an extension from “owners”, had made a mistake and overlooked the existence of the demise charterer and framed its response deliberately in such a way as to maintain the plaintiff’s solicitor’s error; the relevant person at the Club “decided to take advantage of that mistake” (at 289). Not only is that element lacking in the present case, the plaintiff in that case had also commenced proceedings against the demise charterer within the time extension granted, on the hypothesis there under consideration, only by the registered owner.

76 In relation to the second estoppel, which only arose for determination if the demise charterer had not been found to have granted an extension and was not estopped from relying on the time bar, Clarke J would have held that the registered owner was not estopped from denying that it was the proper party to be sued. That is essentially because the owner did not represent that it was a party to the bill of lading contract, notwithstanding that only it had granted an extension of time (at 291). That conclusion is therefore against Ixom’s case.

77 The appeal against the decision of Clarke J on the contractual point was dismissed: The Stolt Loyalty [1995] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 598 (CA) (Hoffmann LJ, Hirst and Glidewell LLJ agreeing). The estoppel claims were not considered. There is nothing in Hoffmann LJ’s judgment that supports Ixom’s case. Indeed, it is hard to understand why Ixom sought to rely on The Stolt Loyalty in support of its case when in truth that case is against it. Also, there is nothing in the passage that it specifically refers to (ie, 287-288 at first instance) in support of its contention that there can be two carriers that deals with that question.

78 Finally, there is the misleading and deceptive conduct claim. It rests on the contention that the 25 May 2018 email represented that the registered owner was the carrier. That has already been disposed of. The primary judge was correct to dismiss that claim.

Conclusion

79 For those reasons, the appeal was without merit and was dismissed with costs.

I certify that the preceding seventy-nine (79) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Rares, Sarah C Derrington and Stewart. |

Associate: