Federal Court of Australia

Do (Trustee), in the matter of Andrew Superannuation Fund v Sijabat [2023] FCAFC 6

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The declaration at 1 and the orders at 4 and 8 of the declarations and orders made by the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Div 2) on 29 April 2022 in proceeding CAG74/2019 (Orders) be set aside and in lieu thereof the following orders be made:

4. the applicant’s claim for a declaration that the payments made by or on behalf of or for the benefit of the first respondent, Tien Dung Do, also known as Tein Dung Do, totalling $437,767 during the financial year ending 30 June 2013 into the Andrew Superannuation Fund are void within the meaning of s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (applicant’s FY13 Claim) be dismissed;

4A. the second respondent, Do Construction Pty Ltd in its capacity as trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund, pay $32,159 (being the sum of the amounts in declarations 2 and 3 of the Orders) plus interest calculated from 28 August 2018 to 8 April 2022 to the applicant; and

8. in relation to the costs of the proceeding:

(a) the applicant is to pay the first and second respondents’ costs in relation to the applicant’s FY13 Claim as agreed or taxed; and

(b) the first and second respondents are to pay the applicant’s costs with respect to declarations 2 and 3 of the Orders and Order 4A as agreed or taxed.

3. The first respondents’ notice of contention filed on 17 June 2022 is dismissed.

4. The first respondent is to pay the appellant’s and second respondent’s costs of the appeal and of the notice of contention.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

ACD 21 of 2022 | ||

BETWEEN: | DO CONSTRUCTION PTY LTD IN ITS CAPACITY AS TRUSTEE OF THE ANDREW SUPERANNUATION FUND ACN 153 972 877 Appellant | |

AND: | MS LOUISA MENG LI SIJABAT AND NICK JIM COMBIS IN THEIR CAPACITY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL TRUSTEES FOR THE BANKRUPT ESTATE OF TIEN DUNG DO, ALSO KNOWN AS TEIN DUNG DO First Respondents MR TIEN DUNG DO ALSO KNOWN AS TEIN DUNG DO, IN HIS CAPACITY AS A FORMER JOINT TRUSTEE OF THE ANDREW SUPERANNUATION FUND Second Respondent | |

order made by: | MARKOVIC, HALLEY AND GOODMAN JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 13 february 2023 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The declaration at 1 and the orders at 4 and 8 of the declaration and orders made by the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Div 2) on 29 April 2022 in proceeding CAG74/2019 (Orders) be set aside and in lieu thereof the following orders be made:

4. the applicant’s claim for a declaration that the payments made by or on behalf of or for the benefit of the first respondent, Tien Dung Do, also known as Tein Dung Do, totalling $437,767 during the financial year ending 30 June 2013 into the Andrew Superannuation Fund are void within the meaning of s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (applicant’s FY13 Claim) be dismissed;

4A. the second respondent, Do Construction Pty Ltd in its capacity as trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund, pay $32,159 (being the sum of the amounts in declarations 2 and 3 of the Orders) plus interest calculated from 28 August 2018 to 8 April 2022 to the applicant; and

8. in relation to costs of the proceeding:

(a) the applicant is to pay the first and second respondents’ costs in relation to the applicant’s FY13 Claim as agreed or taxed; and

(b) the first and second respondents are to pay the applicant’s costs with respect to declarations 2 and 3 of the Orders and Order 4A as agreed or taxed.

3. The first respondents’ notice of contention filed on 17 June 2022 is dismissed.

4. The first respondents are to pay the appellant’s and second respondent’s costs of the appeal and of the notice of contention.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 On 29 April 2022 declarations and orders were made in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Div 2) including relevantly:

(1) declarations that payments made by or on behalf of, or for the benefit of, Tien Dung Do also known as Tein Dung Do totalling $437,767, $7,159 and $25,000 in the financial years ending 30 June 2013, 30 June 2014 and 30 June 2015 respectively into the Andrew Superannuation Fund are void as against Louisa Meng Li Sijabat in her capacity as joint and several trustee of Mr Do’s bankrupt estate (Trustee);

(2) an order that Do Construction Pty Ltd in its capacity as trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund pay the sum of $549,682.12 to the Trustee made up of the total of the payments the subject of the declarations referred to in (1) above and interest of $79,756.12 thereon (Payment Order); and

(3) an order that Mr Do and Do Construction pay the Trustee’s costs in relation to the declarations and the Payment Order made against them respectively (Costs Order).

2 The primary judge had earlier published reasons and made an order requiring the parties to bring in short minutes to give effect to his Honour’s reasons: see Sijabat in her capacity as joint and several trustee for the bankrupt estate of Do v Do in his capacity as a former joint trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund [2021] FedCFamC2G 353 (J).

3 Mr Do and Do Construction have each filed a notice of appeal from the declaration that the payment of $437,767 by or on behalf of Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund in the financial year ending 30 June 2013 is void against the Trustee, the Payment Order insofar as it relates to the sum of $437,767 and the Costs Order. The Trustee and Nick Jim Combis, who is also a joint and several trustee of Mr Do’s bankrupt estate (together Trustees) are named as first respondents to each of the appeals.

4 The Trustees have filed a notice of contention in each appeal in which they contend that the primary judge erred in finding that the payments made by or on behalf of Mr Do to the Andrew Superannuation Fund in the financial year ending 30 June 2013 did not have the main purpose of preventing the transferred property from becoming divisible among Mr Do’s creditors or hindering or delaying the process of making property available for division among his creditors as referred to in s 128B(1)(c) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth).

5 Before proceeding to consider the issues raised by the appeals we note three matters. First, while other claims were made by the Trustee in the proceeding before the primary judge, they are not the subject of the appeals or a cross appeal by the Trustee, to the extent she was unsuccessful in her claim in relation to a property situated at Gozzard Street, Gungahlin, ACT (Gozzard Street Property). Secondly, although each of Mr Do and Do Constructions filed separate appeals commencing separate proceedings, given those appeals arise from the same proceeding before, and orders made by, the primary judge and thus the commonality of issues, they were heard together. Finally, it seems that in his reasons the primary judge refers to the statement of claim filed on 12 January 2021, rather than the amended statement of claim dated June 2021 (ASOC) although that his Honour did so has no impact on the appeals.

background

6 On 18 June 2004 Gungahlin Market Place Dental Centre Pty Ltd entered into a lease with Tower 720 Pty Limited for the premises known as suite 1.6 Gungahlin Marketplace, ACT (Premises). Mr Do was the sole director of Gungahlin Dental and a guarantor of the lease for the Premises. It appears from further facts which are recited below that the lessor, at some point through an unexplained process, became Goongarline Properties Pty Ltd.

7 Mr Do gave unchallenged evidence that from February 2000 to the middle of 2007 he was employed by the Department of Defence and during that time made additional contributions via salary sacrifice to a superannuation fund.

8 In or about 2009 Mr Do met with this accountant who advised him to contribute as much as he could to his superannuation fund to obtain tax benefits and ensure savings for his retirement.

9 On 22 April 2009 A Trustful Builder Pty Ltd was incorporated with Mr Do as its sole director.

10 On or about 1 October 2009 the Andrew Superannuation Fund was established. From the time of its establishment until about 28 August 2012 Mr Do and his former wife, Van Thu Nguyen Trinh, the third respondent in the proceeding before the primary judge, were the trustees of the Andrew Superannuation Fund. Since 28 August 2012 Do Construction has been the trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund.

11 Mr Do gave the following evidence about the contributions he made to the Andrew Superannuation Fund from November 2009 to June 2015:

Date | Contribution |

24 November 2009 (Concessional contribution) | $7,155.95 |

1 February 2010 (Concessional contribution) | $10,000 |

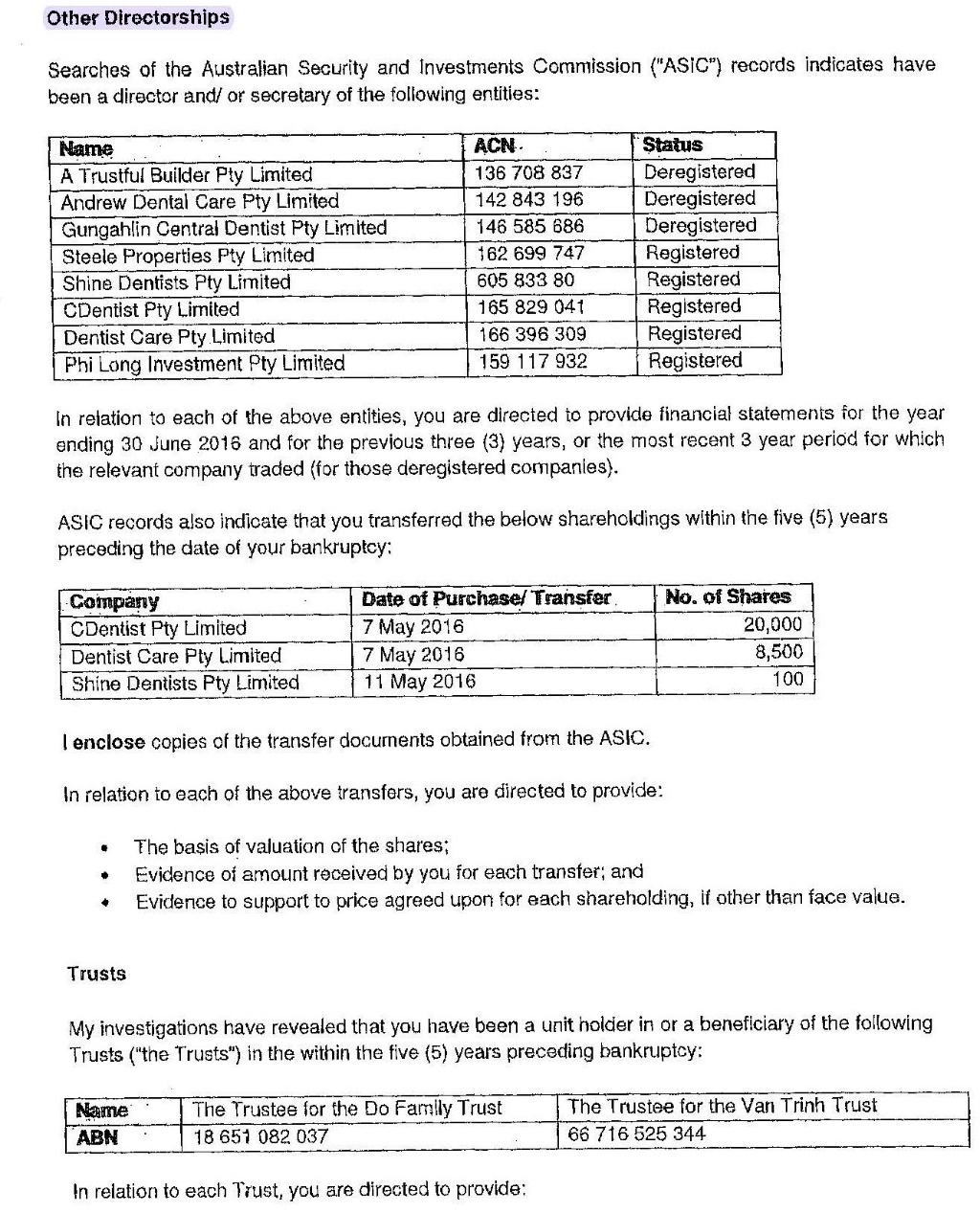

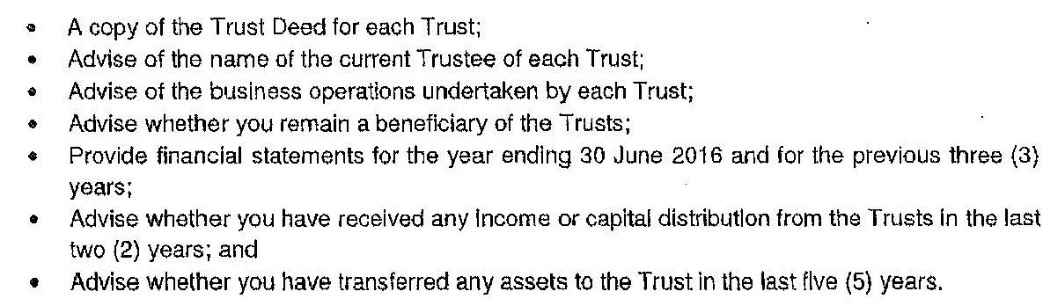

22 March 2010 (Concessional contribution) | $7,844.05 |

1 October 2009 (Non-concessional contribution) | $374 |

12 November 2009 (Non-concessional contribution) | $250 |

20 January 2010 (Non-concessional contribution) | $59,992.99 |

29 January 2010 (Non-concessional contribution) | $107,500 |

1 February 2010 (Non-concessional contribution) | $250 |

5 March 2010 (Non-concessional contribution) | $211,130 |

22 March 2010 (Non-concessional contribution) | $66,982.25 |

30 June 2010 (Non-concessional contribution) | $3,520.76 |

27 June 2011 (Concessional contribution) | $25,000 |

31 January 2013 (Concessional contribution) | $25,000 |

19 July 2012 (Non-concessional contribution) | $5,000 |

31 October 2012 (Non-concessional contribution) | $50,000 |

31 January 2013 (Non-concessional contribution) | $357,767 |

12 December 2013 (Concessional contribution) | $13.92 |

18 December 2013 (Concessional contribution) | $5,100 |

26 June 2014 (Concessional contribution) | $2,045 |

29 June 2015 (Concessional contribution) | $25,000 |

12 In mid-2010 Gungahlin Dental, the dental practice which was the tenant in the Premises, ceased trading.

13 On or about 24 October 2011 Trustful Builder was placed into liquidation.

14 On or about 27 October 2011 Do Construction was incorporated with Mr Do as its sole director.

15 In July and August 2012 the liquidator of Trustful Builder conducted public examinations of Mr Do. In the course of questioning, counsel for the liquidator of Trustful Builder indicated to Mr Do that the liquidator was considering taking action to recover funds from him. The following exchange took place:

Q: So for present purposes, Mr Do, I don’t think it's necessary for us to know everything about your personal life, but the liquidator really does want to know whether or not if he issues proceedings against you that he’s got a chance of recovery; that’s why we ask these questions; do you understand that?

A: Privilege. Yes.

Q: And do you understand that there are - and you’ve had this explained to you by other people, of course, Mr Do, that there are various possible claims against you the liquidator may press?

A: Privilege. I like to know what is the basis of the claims, you know, so we will prepare to substantiate in court; we’re happy to do that.

16 On 29 August 2012 orders were made by consent between Mr Do and Ms Trinh in the Family Court of Australia (now the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Div 1)), the effect of which was that Mr Do’s share in a property at 48 Elizabeth Jolley Crescent, Franklin, ACT was transferred to Ms Trinh and Ms Trinh’s interest in the Andrew Superannuation Fund was transferred to Mr Do. In addition, among other things, the orders provided for ownership of vehicles, entitlement to bank accounts and for Ms Trinh to make a one off payment to Mr Do of $80,000 for spousal maintenance.

17 On 28 November 2012 Paul Morgan, centre manager for “The Marketplace”, the centre in which the Premises were situated, informed Mr Do by email that:

There is currently a lease on foot through until the expiry date of 31 July 2014 (20 months remaining) which needs to be honoured under the current commercial terms.

Therefore, the Landlord is currently not prepared to discuss commercial terms past this point in time.

18 By letter dated 28 March 2013 from the corporate lawyer for Goongarline to Gungahlin Dental, among other things, Goongarline noted that (as written):

As you are aware, the Landlord is prepared to consider entering into a new lease of the Premises with a new party acceptable to the Landlord and, subject to satisfactory commercial terms being agreed in that regard, to negotiate with you for the early surrender of your lease However, pending such agreement being reached, I am instructed that the Landlord requires that you either

1. continue to pay the monthly gross rent owing under the lease as and when it falls due and, on expiry of the lease on 31 July 2014, to perform the make good and redecoration obligations required under the lease; or

2. make payment to the Landlord now of the full gross rent owing under the lease from 1 April 2013 to 31 July 2014 (calculated at $53,308.33 plus GST) together with a payment on account of the cost to the Landlord to make good and redecorate the Premises (subject to confirmation but estimated at approximately $20,000 plus GST), upon receipt of which the Landlord will accept a surrender of your lease.

The Landlord’s Property Portfolio Manager will be able to discuss these options with you in greater detail at the meeting at the Centre on Thursday, 4 April 2013.

The Landlord seeks to achieve a mutually acceptable outcome to the matter and looks forward to the opportunity to meet with you for discussions in that regard. However, it remains the case that the Landlord reserves all of its rights under the lease and will strenuously defend any claim asserted by you regarding the Landlord’s conduct to date. In that regard, please note that the Landlord has not accepted any repudiation of the lease and the Landlord considers the lease to remain on foot.

19 By email sent on 15 April 2013, Mr Do informed Mr Morgan that he had returned the keys for the Premises “last Friday”.

20 A letter dated 16 April 2013 to Gungahlin Dental from Goongarline’s corporate lawyer included:

I am instructed that, on Friday 12 April 2013, you delivered to the offices of the Centre Manager an envelope containing your keys for the Premises. ·

You are reminded that your Lease does not expire until 31 July 2014.

My client will not accept any early vacation of the Premises and requires that you continue to meet all obligations under your Lease: until the Lease Expiry Date, failing which my client will have recourse to the remedies available to it under the Lease.

I am also instructed that you are in arrears in the amount of $3,682.42 representing unpaid rent for the month of Apri1 2013.

Please ensure that payment of this amount is received by my client within seven (7) days of the date of this letter to avoid further action being taken by the Landlord.

A copy of this letter was also provided to Mr Do under cover of a letter also dated 16 April 2013 which provided:

Please find attach (sic) a copy of a letter sent to the Tenant of the above Premises pursuant to a Lease dated 18 June 2004, under which you have guaranteed the performance of the Lease by the Tenant.

21 By letter dated 21 June 2013 from Goongarline’s corporate lawyer, Goongarline informed Gungahlin Dental, among other things, that:

I am instructed that the Tenant has abandoned the subject Premises. Pursuant to section 115 of the Leases (Commercial and Retail) Act 2001 (ACT), the lease has therefore come to an end.

While the Landlord is taking steps to mitigate its losses, the Landlord reserves all of its rights against the Tenant to claim compensation for damage suffered as a result of the early termination of the Lease, including but not limited to loss of rental income for the balance of the Lease term.

In the meantime, please be advised that the Landlord has exercised its right under clause 26.2 of the Lease to call upon the bank guarantee held by the Landlord in relation to the Lease in order to apply those funds towards partial reduction of rental arrears currently owing. I am instructed that, following application of those funds, outstanding arrears remain in the sum of $3,624.25. Please ensure that payment of that amount is made to the Landlord within seven (7) days of the date of this letter to avoid the Landlord taking further action against you in respect of that outstanding sum.

Receipt of the outstanding amount is without prejudice to the Landlord’s ongoing claim for compensation.

(Emphasis in original.)

22 As can be seen from the evidence set out at [11] above, in the financial year ended 30 June 2013 payments totalling $437,767 were made by Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund (FY13 Transfers). It is these payments which are in issue in the appeals.

23 By letter dated 5 July 2013 Goongarline informed Gungahlin Dental, among other things, that it had drawn down and applied the bank guarantee against payment of arrears owing under the lease and that:

The Landlord is taking steps to mitigate its losses arising from the early termination of the Lease. However, arrears under the Lease will continue to accrue as damages and, as previously advised, the Landlord reserves all of its rights against the Tenant accordingly.

24 In a letter dated 3 November 2013 the liquidator of Trustful Builder alleged that Mr Do had breached his duty owed as a director to Trustful Builder.

25 On 23 December 2013 the liquidator of Trustful Builder commenced a proceeding against Mr Do in this Court.

26 In 2014 Goongarline commenced a proceeding in the Magistrates Court of the Australian Capital Territory against Mr Do pursuant to his guarantee of the obligations arising under the lease for the Premises (Guarantee Proceeding).

27 In the financial year ended 30 June 2014 payments totalling $7,159 were made by or on behalf of Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund.

28 On 2 October 2014 Mr Do entered into a deed of settlement and release with Trustful Builder and its liquidator which included:

(1) in the recitals that:

On 23 December 2013, the Company and the Liquidator (together “the Plaintiffs”) commenced proceedings against Tien Dung Do in the Federal Court of Australia, Australian Capital Territory Registry for recovery of money pursuant to sections 180, 181, 182, 588G, 588M and 1317H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (proceeding No. ACD 139/2013) (“the Proceeding”).

The Plaintiffs and Tien Dung Do agree to resolve any and all claims arising out of the Proceeding on the terms contained in this Deed (“the Claims”).

(Emphasis in original).

(2) in cl 2 that Mr Do, on execution of the deed of settlement, agreed to pay the “Settlement Sum” of $20,000;

(3) in cl 3 an acknowledgement by the Plaintiffs that Mr Do entered into the deed of settlement and agreed to pay the “Settlement Sum” on the basis of no admission of liability; and

(4) in cl 4 mutual releases.

29 In the financial year ended 30 June 2015 payments totalling $25,000 were made by or on behalf of Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund.

30 On 7 July 2015 the Magistrates Court made an order in Goongarline’s favour in the Guarantee Proceeding requiring Mr Do to pay $50,000.

31 On 13 May 2016 Goongarline served a bankruptcy notice on Mr Do with which he failed to comply.

32 On 27 July 2016 Goongarline filed a creditor’s petition in the Federal Circuit Court of Australia (now the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Div 2)). On 30 September 2016 a sequestration order was made and the Trustees were appointed as trustees of Mr Do’s bankrupt estate.

33 A creditor listing for Mr Do’s bankrupt estate dated 6 December 2016 lists total debt for unsecured creditors of $59,716.57 comprising the ACT Revenue Office, which claimed $9,716.57, and the landlord of the Premises, Goongarline, which claimed the balance.

the primary judge’s reasons

34 The proceeding before the primary judge was commenced by the Trustee. Mr Do in his capacity as a former joint trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund was the first respondent, Do Construction as the current trustee of the Andrew Superannuation Fund was the second respondent and Ms Trinh was the third respondent, although she took no active part in the proceeding: J [1]-[2].

35 As described by the primary judge at J [3]-[4] the Trustee sought:

(1) declaratory relief about certain payments made into the Andrew Superannuation Fund in the financial years ended 30 June 2013, 30 June 2014 and 30 June 2015 which they alleged were contrary to s 128B and s 128C of the Bankruptcy Act;

(2) declaratory relief in relation to certain payments made to Ms Trinh;

(3) declaratory relief in relation to the ownership of the Gozzard Street Property; and

(4) payment of specified sums from the Andrew Superannuation Fund to the bankrupt estate.

36 At J [8] the primary judge set out his conclusions that:

(1) the Trustee had not proved her case in relation to the Gozzard Street Property against Mr Do and accordingly that part of the claim should be dismissed with the Trustee to pay Mr Do’s costs; and

(2) the Trustee had established each of her other claims against Mr Do. They were the claims in relation to the payments made into the Andrew Superannuation Fund and the transfer to Ms Trinh. Accordingly Mr Do was to pay the Trustee’s costs of those claims.

37 Commencing at J [9], under the heading “Background”, the primary judge set out relevant factual background based on the Trustee’s statement of claim filed on 12 January 2021, rather than the ASOC. They were matters which his Honour said were largely admitted by Mr Do and Do Construction in their respective defences.

38 The primary judge then identified the claims against the respondents noting that they fell into two categories. The first category concerned the transfer of funds and undervalued transactions which were alleged to have had the purpose and intent to defeat creditors contrary to s 128B and s 128C of the Bankruptcy Act. His Honour observed that the transferees were either the Andrew Superannuation Fund or Ms Trinh. The second category concerned the purchase of the Gozzard Street Property in January 2010 which the Trustee alleged was impugned because as at the date of the Trustees’ appointment it vested in them.

39 There is no appeal by Mr Do or Do Construction from the primary judge’s orders and findings in relation to the transfers by Mr Do to Ms Trinh and to the Andrew Superannuation Fund in the financial years ended 30 June 2014 and 30 June 2015 and no appeal by the Trustees in relation to the order dismissing the claim concerning the Gozzard Street Property. Accordingly it is not necessary for us to set out his Honour’s findings in relation to those claims or otherwise to address them.

40 It is only the first category of claims identified by the primary judge (see [38] above), limited to transfers to the Andrew Superannuation Fund in the financial year ending 30 June 2013 (FY13), which is in issue in the appeals.

41 At J [15] the primary judge identified that there were four categories of impugned transfers to the Andrew Superannuation Fund alleged against Mr Do. They relevantly included that during FY13 payments were made by or on behalf of Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund, according to his Honour, for a total amount of $430,996.17. We note that in the ASOC the total amount which the Trustees claimed as payments made by or on behalf of Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund was $437,767, which is consistent with the evidence (see [11] above).

42 Next the primary judge summarised the evidence before him. His Honour did so first by reference to the Trustee’s affidavit and secondly by reference to Mr Do’s evidence. As to the latter it appears that summary was principally based on Mr Do’s cross examination with few references to the evidence given by him in his affidavit, making the summary of Mr Do’s evidence somewhat difficult to follow.

43 Ultimately, at J [85] the primary judge made the following observations and findings about Mr Do’s demeanour as a witness and about his evidence:

For my part, as stated earlier, it was regularly quite difficult to discern whether Mr Do was genuinely (a) misunderstanding relatively straight-forward questions that were put to him about his own financial affairs, (b) having difficulty recalling matters from some years ago, (c) feigning various, and to varying degrees of, lack of recollection of events and transactions involving significant amounts of money, or (d) otherwise undertaking some degree of obfuscation. It was very noticeable when being questioned by Counsel for the Trustee that his evidence was faltering, imprecise, lacking in recollection and remarkable for both his lack of apparent interest in his financial affairs and remarkable [apparent] lack of comprehension about quite straight-forward matters. Yet when questioned by his own Counsel and Counsel for the Second Respondent, his comprehension and apparent ease of recollection and response improved markedly. In short, I found Mr Do’s evidence to be not only difficult and unreasonably imprecise, it was also regularly lacking in basic credibility, particularly regarding his lack of recollection about significant amounts of money flowing through his various bank accounts.

44 Despite the primary judge’s findings about Mr Do’s evidence, his Honour made no particular findings, at least in that part of the reasons, about, relevantly, the FY13 Transfers.

45 At J [103] the primary judge turned to consider whether the Trustees had made out their claim in relation to the payments made by or on behalf of Mr Do into the Andrew Superannuation Fund during FY13 i.e. the FY13 Transfers. In doing so his Honour first reminded himself of the cautions set out in a number of cases to which he had referred earlier in his reasons and noted that it was “critical to do so because of the alarmingly problematic evidence of Mr Do, and the equally alarming lack of documents, other than a range of bank statements regarding the contents of which Mr Do professed a surprising, and concerning, lack of information and general knowledge”. His Honour observed that the issue of lack of records was directly relevant to s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act. After repeating his observations recorded at J [85] about Mr Do as a witness (see [43] above), at J [105] his Honour continued:

A further, complicating factor regarding the evidence was that no submission was made by the Trustee regarding the paucity of evidence from Mr Do’s accountant, upon whose advice regarding contributions to the superannuation funds Mr Do purported to rely and act. This lack of, and lack of reference to, potentially corroborating or supporting evidence, was surprising, and unexplained.

46 At J [106] the primary judge noted “the following as formal findings”:

(1) Mr Do acknowledged that the Premises were abandoned in June 2013 and that he had a potential liability as a guarantor of the lease for them. If Mr Do had such a concern or apprehension in 2013, it was difficult to see how he would not have had the same concern in 2010 when questions about the viability of the dental practice and the lease relating to it arose and were the subject of ongoing correspondence between Mr Do and Goongarline. The primary judge noted that in that correspondence the parties were looking for, and proposing, alternative means to resolve the difficulties with the Premises and the lease;

(2) he did not accept Mr Do’s contention that he did not know of, or have explained to him earlier, his potential liability under the guarantee for the lease of the Premises. His Honour had difficulty in accepting that Mr Do would not be “properly, prudently or reasonably precise and attentive to” important details in all of his dealings about his financial affairs. He found that Mr Do’s submission about his lack of awareness of the full effect of the guarantee to be “unsupportable”. His Honour found that it was even more implausible that Mr Do was unaware of, and or unconcerned about, the very large sums of money flowing through his bank accounts between July 2012 and 2015; and

(3) prior to 2012 Mr Do had a history of making regular payments into the Andrew Superannuation Fund, some of which were large. The primary judge referred to Mr Do’s contribution for the financial year ending 30 June 2010 in the sum of $450,000 noting that again the source and general provenance of this sum was opaque as it was in relation to the payments the subject of the Trustee’s claim.

47 The primary judge concluded (at J [109]) that, having regard to the strict terms of s 128B(1)(c) of the Bankruptcy Act and the requirement of clear, cogent or strict proof, he was unable to find that the requisite standard of proof to meet the requirements of that subsection had been met by the Trustee. His Honour continued:

… Put another way: just because large sums of money are involved, and just because various documents (other than bank statements) were not produced, does not, of itself, constitute the requisite intention relevantly to establish that Mr Do’s “main purpose” was to prevent the transferred property from becoming available or divisible for his creditors. This is especially so having regard to his history, for some years prior to the impugned transactions, of regularly contributing funds to his superannuation fund. This history would relevantly satisfy the terms of s.128B(3)(a) of the Act.

48 The primary judge then proceeded to consider the operation of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act and what his Honour referred to as the deeming provision in s 128B(2) of the Bankruptcy Act. It is his Honour’s analysis and application of the operation of those subsections that is in issue on the appeals. In relation to the applicability or otherwise of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act, at J [114]-[117] his Honour referred to three things that he said could be “stated with some confidence as follows”:

114 First, in the course of Mr Do’s cross examination (with relevant details set out earlier in these reasons), he consistently confirmed that he had no recollection about the provenance of the significant amounts deposited in his various accounts, or any documents regarding them. He did not know, and/or could not explain, where the funds came from or where they went. Nor did he have any recollection or knowledge of any documents relating to the disposal or dispersion of them.

115 Secondly, in earlier examinations of him, for example by the Trustee, and in earlier written notice/request given to him by the Trustee, Mr Do was put on notice of specific areas of interest and specific documents required regarding same. As the cross examination details in the current proceeding set out earlier in these reasons made plain, (a) Mr Do had no recollection (or knowledge) about any of the transactions he was taken to via reference to his bank statements, and (b) he had no recollection (or knowledge) about, and did not produce any documents in relation to, any of the said transactions, other than his bank statements.

116 It must follow from these earlier examinations and requests for information that Mr Do must have known the kinds of information and documents that were being sought by the Trustees. There was no evidence that, between any of these examinations or requests for information, Mr Do undertook any relevant inquiry either to obtain information and or documents that were so earnestly sought by the Trustee. As his own evidence at the hearing before this Court confirmed, he had neither knowledge of, nor documents that relevantly assisted either him, the Trustee, or the Court in relation to, any of the impugned transactions. Nor did Mr Do have any explanation why this was so. The documents and information sought must have been, at some stage, relevantly in his possession or knowledge. The most basic information regarding the impugned transactions was set out in his bank statements. His lack of information, lack of recollection, and lack of supporting documents regarding those transactions, left a gaping hole in his evidence, and to a significant degree in his credibility.

117 Thirdly, the subject of “record-keeping” in sub-section 128B(5) was clearly a vexed issue both factually and legally. Factually, as already noted, apart from his bank statements, Mr Do confirmed that he had no relevant records and had no recollection of any of the significant and other sums set out in the bank statements annexed to his Affidavit and upon which he asked many questions, regrettably, to little effect and even less illumination.

(Emphasis in original.)

49 The primary judge noted that there was no relevant authority about the operation of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act and the duty on a bankrupt to keep “such books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in relation to the business carried on by the transferor and as sufficiently disclose the transferor’s business, transactions and financial position, or … who has not preserved them”, as required by s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act.

50 At J [119] his Honour said:

Regarding “the business carried on by the transferor”, for current purposes, the range of companies, trusts and other interests in which Mr Do had a relevant interest, one need look no further than the list of such entities set out in Mr Combis’s letter to Mr Do dated 8th December 2018, which is Annexed at Tab 15 to Ms Sijabat’s trial Affidavit.

51 In the absence of any authority in relation to s 128B(5) the primary judge discerned general principles by analogy from the area of record keeping and financial records as applied by courts in matters involving corporations but noting that with any analogy “one must be careful to ensure that too strict an application from another area of discourse is not applied to the matter at hand”. In particular his Honour referred to s 286 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) which he noted provides basic requirements in relation to financial records and record-keeping. His Honour observed that “[t]hose records must: (a) correctly record and explain its transactions and financial position and performance; and which (b) would enable true and fair financial statements to be prepared and audited”: J [122]. At J [123] the primary judge observed that:

The accent on (i) correct records, (ii) explanation of transactions and (iii) the disclosure of the true financial position of the person or entity in question, are perhaps the most crucial principles relevant to the current matter.

(Emphasis in original.)

52 At J [125]-[127] the primary judge reasoned that:

125 In many ways, the situation here is somewhat easier simply because of the complete absence of relevant documents (or any other information, other than bank statements) regarding Mr Do’s significant transfers of funds. The deficits regularly referred to here made the clarification and determination of his “true financial position” almost impossible. The fault for this was completely the responsibility of Mr Do.

126 Finally, should it need to be recorded, the relevant assessment is, strictly speaking in the context of corporations and taxation law, an objective assessment of the requirements for the keeping of relevant financial records. In my view, the same objective standard should apply to individuals, which is also to say that a simple, subjective assessment (in this instance, by Mr Do) of his or her financial position is more likely than not to be either inaccurate, and/or unreliable. This must clearly be the case with Mr Do. Viewed objectively, his evidence was either or both inaccurate and or unreliable regarding his true financial position, especially since he provided no documents at all even after he was put on notice by the Trustee about what was required, and the importance of providing them.

127 In the light of the outline of principle to which I have referred in the paragraphs above, the lack of information – oral and documentary – must lead to Mr Do financially condemning himself. The glaring lacunae in his evidence in this regard, in my view, readily satisfies the requirements of the deeming provisions in s.128B(5) such that the rebuttable presumption of insolvency applies. Otherwise, and in addition to these reasons, I accept the Applicant’s submissions in this regard set out earlier in these reasons. Accordingly, the relief sought by the Trustee regarding the funds referred to regarding the financial year ended 30th June 2013 should be granted.

the appeals

53 As set out at [3] above, there are two appeals before the Court.

54 In his notice of appeal Mr Do raises the following grounds of appeal:

1. The trial judge erred in finding, as a matter of fact, at [127] of the judgment that the evidence established that, at the time of each of the transfers during the 2013 financial year, the appellant had not kept, or if kept, had not preserved such books and records as are usual and proper in relation to the business carried on by him during that year as sufficiently disclosed his business transactions and financial position in circumstances where:

(a) the Court made no finding as to what, if any, business was carried on by the appellant during that year; and

(b) the Court made no finding, in respect of any such business as was being carried on, as to the books and records which might usually and properly be kept or preserved by or in the course of such a business.

2. The trial judge erred, in deciding, at [126]-[127] of the judgment that the presumption under section 128B of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Act) had arisen, by taking into account an irrelevant consideration, namely a failure by the appellant to explain, by his oral or written evidence or by documents tendered by him, each of the transactions referred to in bank statements in respect of his personal bank accounts when such were not shown to have been accounts which were maintained in the course of or for the purpose of any business conducted by him.

3. The trial judge erred, at [127] of the judgment, in finding that, by reason of the finding that the books and records in respect of the 2013 financial year and which required by section 128B of the Act, had not been kept and preserved, it was to be presumed that the dispositions made during that year by the appellant to the second respondent were made with the main purpose specified in s 128B(1)(c) of the Act, without first determining whether the appellant had or had not rebutted the presumption of insolvency provided for by s128B(5) of the Act.

4. In the alternative to appeal ground 3, the trial judge failed to provide adequate reasons for finding that the rebuttable presumption in section 128B(5) of the Act had not been discharged.

5. The trial judge erred in failing to find that the rebuttable presumption in section 128B(5) of the Act had been discharged and that, at the time of each of the impugned dispositions during the 2013 financial year, Mr Do was not, nor was he about to become, insolvent.

55 In its notice of appeal Do Construction raises the following grounds of appeal:

Ground 1

1. The trial judge erred in finding, as a matter of fact (at [127] of the judgment dated 14 December 2021 (the Judgment)) that the evidence established that, at the time of each of the transfers during the 2013 financial year, by or on behalf of Mr. Tien Dung Do (Mr Do) (the first respondent below) had not kept, or if kept, had not preserved such books and records as are usual and proper in relation to the business carried on by him during that year as sufficiently disclosed his business transactions and financial position in circumstances where the Court made:

(a) no (or adequate) finding as to what, if any, business was carried on by Mr. Do during that year; and/or alternatively

(b) no finding in respect of any such business as was being carried on, as to the books and records which might usually and be properly kept or preserved by or in the course of such a business;

within the meaning of s 128B (5) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Act).

Particulars

The transfers made during the 2013 financial year are those the subject of the Declaration made at item 1 of the Orders (the 2013 transfers).

Ground 2

2. By reason of the matters set out in ground 1 above, the trial judge erred in law in concluding (at [127] of the Judgment) that a rebuttable presumption arose or applied by operation of s128B (5) of the Act, in respect of the 2013 transfers.

Ground 3

3. The trial judge erred in law, in concluding the presumption under section 128B(5) of the Act had arisen (at [127] of the Judgment), by taking into account an irrelevant consideration, namely the inability of Mr. Do to recollect or explain, by his evidence or documents tendered by him, each of the transactions referred to in bank statements in respect of personal bank accounts which were not shown to have been accounts which were maintained in the course of any business conducted by him.

Particulars

The irrelevant consideration primarily appears in [114] of the Judgment.

Ground 4

4. In the alternative, to appeal ground 2, in concluding that the presumption under section 128B (5) of the Act had arisen (at [127] of the Judgment), the trial judge erred in law in failing to consider whether the rebuttable presumption had been discharged, in that at the time of the 2013 transfers Mr Do was not, nor was he about to become, insolvent.

Particulars

The trial judge failed to consider or address the:

(i) unchallenged evidence of Mr. Do that he was solvent and the time of the 2013 transfers; and

(ii) evidence tendered by Mr. Do showing the source of the funds the subject of the 2013 transfers; and

(iii) submissions made to the effect of (a) and (b) above.

Ground 5

5. In the alternative to appeal ground 4, the trial judge erred in law in failing to provide any or adequate reasons for finding that the rebuttable presumption in section 128B (5) of the Act had not been discharged, in the circumstances particularised in ground 4 above.

56 Mr Do’s and Do Construction’s appeals essentially raise the same issues for determination. They are:

(1) whether the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act was established by the Trustee (Issue 1);

(2) assuming the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act was established, whether the primary judge failed to consider whether Mr Do had rebutted the presumption (Issue 2);

(3) if the primary judge had in fact made a finding at J [127] that Mr Do failed to discharge the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act, whether his Honour provided adequate reasons for reaching that conclusion (Issue 3); and

(4) whether the primary judge failed to consider whether the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act had been discharged and that at the time of the FY13 Transfers Mr Do was not, or was not about to, become insolvent (Issue 4).

57 We deal with each issue below.

Issue 1: the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act

58 Issue 1 is raised by grounds 1 and 2 of each of Mr Do’s notice of appeal and grounds 1, 2 and 3 of Do Construction’s notice of appeal. It raises for consideration the proper construction of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act and his Honour’s findings at J [126]-[127].

59 Before proceeding further it is convenient to set out s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act. It provides:

Superannuation contributions made to defeat creditors--contributor is a person who later becomes a bankrupt

Transfers that are void

(1) A transfer of property by a person who later becomes a bankrupt (the transferor) to another person (the transferee) is void against the trustee in the transferor’s bankruptcy if:

(a) the transfer is made by way of a contribution to an eligible superannuation plan; and

(b) the property would probably have become part of the transferor’s estate or would probably have been available to creditors if the property had not been transferred; and

(c) the transferor’s main purpose in making the transfer was:

(i) to prevent the transferred property from becoming divisible among the transferor’s creditors; or

(ii) to hinder or delay the process of making property available for division among the transferor’s creditors; and

(d) the transfer occurs on or after 28 July 2006.

Showing the transferor’s main purpose in making a transfer

(2) The transferor’s main purpose in making the transfer is taken to be the purpose described in paragraph (1)(c) if it can reasonably be inferred from all the circumstances that, at the time of the transfer, the transferor was, or was about to become, insolvent.

(3) In determining whether the transferor’s main purpose in making the transfer was the purpose described in paragraph (1)(c), regard must be had to:

(a) whether, during any period ending before the transfer, the transferor had established a pattern of making contributions to one or more eligible superannuation plans; and

(b) if so, whether the transfer, when considered in the light of that pattern, is out of character.

Other ways of showing the transferor’s main purpose in making a transfer

(4) Subsections (2) and (3) do not limit the ways of establishing the transferor’s main purpose in making a transfer.

Rebuttable presumption of insolvency

(5) For the purposes of this section, a rebuttable presumption arises that the transferor was, or was about to become, insolvent at the time of the transfer if it is established that the transferor:

(a) had not, in respect of that time, kept such books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in relation to the business carried on by the transferor and as sufficiently disclose the transferor’s business transactions and financial position; or

(b) having kept such books, accounts and records, has not preserved them.

...

Protection of successors in title

(6) This section does not affect the rights of a person who acquired property from the transferee in good faith and for at least the market value of the property.

Meaning of transfer of property and market value

(7) For the purposes of this section:

(a) transfer of property includes a payment of money; and

(b) a person who does something that results in another person becoming the owner of property that did not previously exist is taken to have transferred the property to the other person; and

(c) the market value of property transferred is its market value at the time of the transfer.

60 At J [126]-[127] (see [52] above) the primary judge found that in light of the lack of documentary evidence the “requirements of the deeming provisions in s 128B(5)” were satisfied “such that the rebuttable presumption of insolvency applies”.

The parties’ submissions

61 In summary, Mr Do and Do Construction submitted that the Trustees bore the onus of establishing to the Court’s satisfaction that the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act had been engaged. They contended that the cases in relation to s 286 of the Corporations Act, referred to by the primary judge, are of little assistance in construing s 128B(5). The former is not an analogue of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act as is evident from a comparison of the statutory text of the sections.

62 Mr Do and Do Construction submitted that before a debtor’s record keeping can, by reference to s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act, be found to be inadequate there needs to be a factual inquiry: first, to identify the debtor’s business; and secondly, to determine what records are usually and properly maintained in a business of that type. They contended that once the result of those factual inquiries are known, the debtor’s records can be judged against the statutory formula. Mr Do and Do Construction observed that the primary judge did not address any of that detail, at J [125]-[126] the primary judge applied a different test to that posited by the statute and the conclusion expressed at J [127] appears to have been reached by reversing the onus of proof.

63 Mr Do and Do Construction submitted that the primary judge failed to investigate the issues such as the factual and legal difference between the business carried on by the companies of which Mr Do was a director and/or shareholder and his own business, if any, at the relevant time nor was any finding made about that. They submitted that there was no attempt to establish what records are usually kept in respect of any business which the facts established Mr Do was conducting at the time. Do Construction also submitted that issues about Mr Do’s recollection were not relevant to making a finding as to whether the presumption applied.

64 Mr Do and Do Construction submitted that the correct conclusion was that s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act had not been engaged on the facts. Had it been, the result would have been the dismissal of the Trustees’ claim for the FY13 Transfers.

65 The Trustees submitted that, contrary to Mr Do and Do Construction’s contention, the primary judge identified Mr Do’s business at J [119] as his interests in various companies and trusts. They said that the primary judge considered concepts concerning books and records in other areas of the law concluding (at J [126]) that the relevant standard was to permit an objective assessment of a person’s financial position. The primary judge found that the lack of information did not permit the financial position to be ascertained. The primary judge said that there was no documentary information provided beyond bank statements, which did not satisfy s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act and, it followed, that the presumption was engaged. The Trustees submitted that the primary judge’s reasoning process was correct and that the way in which Mr Do and Do Construction now put their case is a departure from the way in which the case was put below.

66 The Trustees then made submissions about the proper construction of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act. They submitted that the concept of “business carried on by the transferor” in that section is not synonymous with carrying on a commercial enterprise and that the section must be capable of application to persons who are not doing so, such as the unemployed, retired or those engaged in unpaid domestic duties. They contended that the proper construction of the expression contemplates an enquiry into the nature of the activities engaged in by the transferor to be determined on a case by case basis.

67 While they accepted that s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act can be satisfied in the way posited by Mr Do and Do Construction, that is by identifying the “business” carried on, what books and records ought to have been kept, and pointing to a deficiency, the section does not necessarily require that approach. The Trustees identified at least two reasons why that was so.

68 First, the Trustees submitted that s 128B(5)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act refers to keeping not only such books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in relation to the business carried on but additionally refers to “and as sufficiently disclosed the transferor’s business transactions and financial position”. They said that the documents must sufficiently disclose the business transactions and financial position and if they do not do so the section is engaged. The Trustees submitted that conclusion could be reached irrespective of a positive finding of exactly what “business” the transferor was engaged in.

69 Secondly, the Trustees contended that if faced with a bankrupt who failed to provide documents or to explain his or her activities it would be an incorrect construction to say that the presumption could not be engaged. They submitted that would defeat the purpose of the section, which is obviously aimed at not permitting bankrupts to avoid the operation of s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act by failing to provide information. The Trustees said that therefore if a conclusion can be reached irrespective of what “business” was being carried on by the transferor that the books, accounts and records could not constitute those usually kept (as sufficiently disclose the business transactions and financial position), the presumption would be engaged.

70 The Trustees submitted that, in any event, on either Mr Do and Do Construction’s construction of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act, or their own, grounds 1 and 2 of the appeals would be rejected. In relation to the “business carried on” by Mr Do in FY13, they referred to the evidence at J [119] where the primary judge said that Mr Do was a director or secretary of nine companies, had an interest in the Do Family Trust and Van Trinh Family Trust and noted that one of the companies was his building company, albeit it was in liquidation, and another was Do Construction. They observed that Mr Do’s interest in trusts was reflected in his tax returns, noting particular matters in Mr Do’s tax return for FY13. The Trustees said these were matters going to the “business carried on” by Mr Do in FY13.

71 The Trustees submitted that Mr Do did not produce documents satisfactorily explaining the trust distributions, the interest earned by him or transactions which resulted in a capital gains tax liability. They contended that, on Mr Do and Do Construction’s construction, s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act is engaged on this evidence. The Trustees said that this conclusion is fortified because Mr Do’s “business”, as revealed at J [119] and by his tax returns, cannot be reconciled with the large sums transferred into and out of his bank account. The Trustees observed that Mr Do gave no evidence explaining the transactions, there was no reversal of any onus, as contended by Mr Do and Do Construction, and the issues were investigated. To that end the Trustees submitted that the cross examination investigated Mr Do’s dealings thoroughly, he could not explain the transactions and did not produce documents.

72 The Trustees submitted that therefore, on Mr Do and Do Construction’s construction, s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act is satisfied as one knows what Mr Do’s business was and the documents produced did not “pass muster”. The Trustees also submitted that on their construction s 128B(5) is even more readily satisfied as Mr Do was engaged in some sort of “business” as disclosed by his bank statements, but there were no documents kept by him that could explain what that was or his financial position.

73 The Trustees submitted that for the same reasons there was no error in the primary judge’s conclusion that the rebuttable presumption in s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act was engaged.

Consideration

74 The question to be resolved, namely whether the Trustees established the facts necessary for the rebuttable presumption to arise for the purposes of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act, requires a consideration of the proper construction of that section. The dispute that arises concerns: first, the meaning of the phrase “business carried on by the transferor” as used in subs 128B(5)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act; and secondly, who bears the onus of showing what books, accounts and records are usually kept in relation to the “business”.

75 As to the first issue, as is evident from the parties’ respective submissions, Mr Do and Do Construction contend for a narrow construction of s 128B(5)(a), while the Trustees contend for a broad construction. Mr Do and Do Constructions say the subsection is concerned with the commercial activity of the bankrupt at the relevant time while the Trustees say the subsection can be construed more broadly and can include activities such as those described at [66] above at the relevant time, even if the transferor was not carrying on a business.

76 The starting point for ascertaining the meaning of a statutory provision is the text, while at the same time regard should be had to context and purpose: see SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 262 CLR 362 at [14]. Focus on the text requires consideration of the natural and ordinary meaning of the words in the provision. But the text must also be considered in context which includes the statute as a whole. In our opinion when that is done, s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act is to be construed in the narrow way contended for by Mr Do and Do Construction. That is apparent both from the ordinary meaning of the text and a consideration of the provision in context.

77 The text of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act is set out at [59] above. While there may be some ambiguity about the meaning of the phrase “the business carried on by the transferor”, in our view, the natural meaning of the words supports the narrow construction. The subsection focuses on the business of the transferor. That is to be construed as the business, if any, carried on by the transferor at the time of the impugned transactions. The use of the definite article in s 128B(5) cannot carry with it any implication that the transferor must be carrying on a business. There is no indication in the text of s 128B(1), or the extrinsic materials, that superannuation contributions to defeat creditors by persons who later become bankrupt are only void if the transferor was carrying on a business at the time of the impugned transfer.

78 The books, accounts and records that are required to be kept are the books, accounts and records as are usual and proper for the business, if any, carried on by the transferor. The plain meaning of those words does not support a construction where “the business carried on by the transferor” could extend to activities carried on by a retiree, a person engaged in unpaid domestic duties or a person who may be engaged in full time employment but does not carry on the business, in terms of having ownership and/or control over its activities, in which he or she is employed. Those undertakings could not be classified as a “business”.

79 That construction is supported by a consideration of the context and purpose of the provision. To that end, it is informative first to have regard to the history of s 128B of the Bankruptcy Act. It was introduced into the Bankruptcy Act by the Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment (Superannuation Contributions) Act 2007 (Cth). The explanatory memorandum which accompanied the Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment (Superannuation Contributions) Bill 2006 (Cth) explained at [27] that “the new section 128B describes when a superannuation contribution made by the person who later becomes bankrupt is void against the bankruptcy trustee”. It was said to be based on existing s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act. At [30] the explanatory memorandum noted in relation to s 128B(5) that:

Subsection 128B(5) provides a rebuttable presumption of insolvency for the purposes of subsection 128B(2) where the transferor had not kept proper books and records relating to the time of the transfer. This is line with existing subsection 121(4A).

80 Amendments to s 120 and s 121 of the Bankruptcy Act had been made the previous year by the Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment (Anti-avoidance) Act 2006 (Cth) (2006 Bankruptcy Amendment Act). Those sections concern respectively undervalued transactions and transfers of property made to defeat creditors. The amendments made by the 2006 Bankruptcy Amendment Act to s 120 and s 121 introduced respectively s 120(3A) and s 121(4A). Section 121(4A) is identical to s 128B(5) and s 120(3A) is in largely identical terms to s 128B(5). The explanatory memorandum which accompanied the Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment (Anti-avoidance) Bill 2005 (Cth) provided in relation to the introduction of those subsections:

Rebuttable presumption of insolvency

8. A further proposed amendment will create a rebuttable presumption of insolvency for the purposes of sections 120 and 121 of the Act. A presumption will arise that the transferor was insolvent at the time of the transfer if it is established that the transferor had not, in respect of that time, kept proper ‘books, accounts and records’; or where, having kept the appropriate books, accounts and records in relation to that time, the transferor had failed to preserve them. A similar presumption will be introduced in relation to Division 4A of Part VI of the Act.

9. These amendments are proposed on the basis that it is usual commercial practice to keep these books and records. This removes the incentive to avoid making, hiding or destroying, records that would demonstrate insolvency. This amendment will overcome some of the difficulties faced by trustees when, for example, endeavouring to establish an intention on the bankrupt’s behalf to defeat the interests of creditors under section 121. The bankrupt will of course have the opportunity to rebut the presumption.

(Emphasis added.)

81 The explanatory memorandum, referring as it does to existing s 121(4A) of the Bankruptcy Act, supports the narrow construction. That is, the legislature expressly noted that s 121(4A) is concerned with usual commercial practice and it must follow, in the case of s 128B(5), that it is similarly concerned with usual commercial practice on the part of the transferor. That it does suggests that the purpose of s 128B(5) was to permit a finding that would lead to a rebuttable presumption of insolvency where the transferor had not followed usual commercial practice in maintaining books and records in relation to his or her business.

82 There are, as the primary judge observed, no authorities which have considered s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act nor it seems the construction of its analogues in s 120(3A) or s 121(4A).

83 The primary judge had regard to s 286 of the Corporations Act in construing the section. It relevantly provides:

(1) A company, registered scheme or disclosing entity must keep written financial records that:

(a) correctly record and explain its transactions and financial position and performance; and

(b) would enable true and fair financial statements to be prepared and audited.

The obligation to keep financial records of transactions extends to transactions undertaken as trustee.

The term “financial records” is defined in s 9 of the Corporations Act and includes, among other things, invoices, receipts, orders for the payment of money, bills of exchange, cheques, promissory notes and vouchers.

84 As can be seen, s 286 of the Corporations Act imposes on a company, or other specified entity, a positive obligation to maintain financial records to a particular standard. It is not an analogue of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act and decisions in relation to s 286 of the Corporations Act do not assist in the construction or application of s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act.

85 In the course of argument we were taken to s 270 of the Bankruptcy Act. That section relevantly provides:

(1) A person who has become a bankrupt after the commencement of this Act and:

(a) has not kept such books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in any business carried on by him or her and as sufficiently disclose his or her business transactions and financial position during any period while the business was being carried on within the period of 5 years immediately preceding the date on which he or she became a bankrupt; or

(b) having kept such books, accounts or records, has not preserved them;

commits an offence and is punishable, upon conviction:

(c) in the case of a person who has previously been either a bankrupt whose bankruptcy has not been annulled or a person whose affairs have been administered under a personal insolvency agreement, a deed of assignment or a deed of arrangement under this Act or the repealed Act or who has made a composition or arrangement with creditors under this Act or the repealed Act–by imprisonment for a period not exceeding 3 years; and

(d) in the case of any other person–by imprisonment for a period not exceeding 1 year.

…

(Emphasis added.)

86 As is evident, s 270 does not use the identical phrase to that found in s 128B(5) of “such books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in relation to the business carried on by the transferor”. But it bears some relationship to s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act in the requirement for the bankrupt to have kept “such books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in any business carried on by him or her” and which “sufficiently disclose his or her business transactions and financial position”. That is, like s 128B(5), s 270 focusses on financial records relating to any business carried on by the bankrupt.

87 Analogous provisions to s 270 of the Bankruptcy Act (found in UK bankruptcy legislation and the predecessor legislation to the Bankruptcy Act), which required a bankrupt to have kept such books and records as sufficiently disclose his or her business transactions and/or financial position, have been the subject of consideration, both as to their construction and what is required to prove a breach.

88 As to the question of the construction of those analogous provisions, the starting point is Ex parte Board of Trade; in Re Mutton (1887) 19 QBD 102. In that case, the question before the court was whether the bankrupt had omitted to keep books of account required by s 28 of the Bankruptcy Act 1883 (UK) (UK Bankruptcy Act 1883). That section relevantly provided

28. Discharge of bankrupt.

…

(2.) On the hearing of the application the Court shall take into consideration a report of the official receiver as to the bankrupt’s conduct and affairs, and may either grant or refuse an absolute order of discharge, or suspend the operation of the order for a specified time, or grant an order of discharge subject to any conditions with respect to any earnings or income which may afterwards become due to the bankrupt, or with respect to his after-acquired property:

Provided that the Court shall refuse the discharge in all cases where the bankrupt has committed any misdemeanor under this Act, or Part II. of the Debtors Act, 1869, or any amendment thereof, and shall, on proof of any of the facts herein-after mentioned, either refuse the order, or suspend the operation of the order for a specified time, or grant an order of discharge, subject to such conditions as aforesaid.

(3.) The facts herein-before referred to are—

(a.) That the bankrupt has omitted to keep such books of account as are usual and proper in the business carried on by him and as sufficiently disclose his business transactions and financial position within the three years immediately preceding his bankruptcy:

…

(Emphasis added.)

89 In Re Mutton the bankrupt was a hatter but had also acquired a parcel of land, adjacent to land he already owned, with the intention of selling the two parcels together. The appellant argued that the bankrupt ought to have entered the land transactions in his books. The contrary argument was that a person was only bound to keep books if he or she is carrying on a business in which it is usual to do so, in which case he or she is bound to keep the books which are usual in that particular business.

90 At 106-107, Lord Esher, M.R. (with whom Lopes L.J. agreed) said:

The first thing mentioned is the kind of books which he is to keep, – such books as are “usual and proper in the business carried on by him,” – and the following words shew the manner in which he is to keep those books. It would be of no use to insist that he should keep books if he might keep them in any way he liked, and therefore the section goes on to say, “and as sufficiently disclose his business transactions and financial position.” I cannot help thinking that all those words are joined together to describe the kind of books which he is to keep, and the manner in which he is to keep them under certain circumstances. If he is engaged in a business in which books are usually kept of a certain kind, he is to keep those usual books, but he is to keep them so as “sufficiently to disclose his business transactions and financial position.” It seems to me that the only reasonable way of reading those words is, as meaning his financial position as a man of business. If you dislocate the words “financial position” from the others, you would, as I have already said, be causing a revolution in the social life of England. It would come to this, that everybody in the kingdom must keep books which will “sufficiently disclose his financial position.” Before this statute no one ever heard of such a thing, nor was it even suggested until now that a person who is engaged in no business at all, that every man and woman over twenty-one years of age is to keep books which will shew his or her financial position. It seems to me that this would be a revolution, and I cannot agree that that is the meaning of the words. The statute, as I have often said, deals with business matters, and we must give a business meaning to it. In my opinion the meaning is, that a man in business must keep his books properly, but if his business is one in which it is not usual to keep any books, or if the man is not engaged in business, then he need not keep any books at all. If it means that a business man is to keep business books, it cannot mean that a man of business is to put down all his private concerns in his business books, where they would be out of place, and, if he is not to enter them in his business books, he is not bound to keep any other books.

91 A majority of the court in Re Mutton clearly favoured the narrow construction of s 28(3)(a) of the UK Bankruptcy Act 1883 which, like s 270 of the Bankruptcy Act, required that a person had kept books and accounts which disclosed his or her business transactions relating to the business which the person carried on.

92 In Re Lane (1909) 26 WN (NSW) 60 in determining whether the bankrupt in that case, Mr Lane, should be discharged from bankruptcy the court considered, among other things, whether he had “failed to keep such books and accounts as are usual or proper in the business carried on by him”. In relation to that issue the court applied Re Mutton and concluded that the bankrupt was not under an obligation to keep books. The court noted that Mr Lane was the salaried director of a limited liability company who held a large number of shares in the company and otherwise had some small private means. At 61 Salusbury R. observed:

The only transactions of a business nature that I am aware of are two in the course of three years: a speculation in jute goods and the barter of a motor car for some coal, by way of part payment. These two isolated transactions do not in my mind establish that he carried on business as a jute merchant or a dealer in motor cars, or of coal merchant.

93 Most recently, in Re Aarons; Ex parte the Bankrupt (1978) 33 FLR 2; 19 ALR 633 the bankrupt applied for discharge from bankruptcy. The official receiver opposed the grant of an order of discharge because, among other things, he contended that the bankrupt failed to keep proper books as required by s 150(6) of the Bankruptcy Act.

94 Section 150 of the Bankruptcy Act (now repealed) relevantly provided:

(5) The Court shall, if any of the matters specified in the next succeeding sub-section is established-

(a) refuse to make an order of discharge; or

(b) make an order of discharge but suspend the operation of the order as the Court thinks proper, either unconditionally or subject to conditions.

(6) The matters upon the establishment of which the Court may exercise the powers specified in the last preceding sub-section are as follows:

(a) that the bankrupt has omitted to keep and preserve such books, accounts or records as sufficiently disclose his business transactions and financial position within the period of five years immediately preceding the date on which he became a bankrupt;

…

95 At 5 of Re Aarons Riley J observed that:

Predecessors of s 150(6)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 had, like s. 270(1) and its predecessors. 209(g) of the Bankruptcy Act 1924, referred (with minor variations of verbiage) to the omission to keep such books “as are usual and proper in the business carried on by him and as sufficiently disclose his business transactions and financial position”: see Bankruptcy Act 1883 (Eng.), s. 28(3)(a); Bankruptcy Act, 1887 (N.S.W.), s. 38(a); Bankruptcy Act 1914 (Eng.), s. 26(3)(b); Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth), s. 119(7)(b). The words “as are usual and proper in the business carried on by him and” do not occur in s. 150(6)(a).

96 After referring to Re Mutton, at 5-6 his Honour continued:

The words “as are usual and proper in the business carried on by him and” were said by Matthew J. in the court below to be “the governing description” and they were so treated by Lord Esher M.R. in the passage I have just quoted from his judgment on appeal. Though they are absent from s. 150(6)(a), I think Lord Esher’s interpretation of the remaining words of the phrase is still valid. It is those words which “describe the kind of books” (etc.) which the bankrupt is to keep, and there has been no change in them such as to bring about the revolution of which Lord Esher spoke. In my opinion it is significant that the words are “his business transactions and financial position” and not “his business transactions and his financial position”, and they should be read as meaning “the transactions and financial position of his business”.

(Emphasis in original.)

97 It is apparent from these decisions that the phrase “books, accounts and records as are usual and proper in any business carried on by [a person who becomes a bankrupt] and as sufficiently disclose his or her business transactions and financial position” was given a narrow construction, similar to that propounded by Mr Do and Do Constructions. That is, the books and records that are to be kept are those in relation to any business maintained by the bankrupt, which was considered to be a commercial enterprise, and which sufficiently disclose the transactions and financial position of that business.

98 While s 128B(5) of the Bankruptcy Act is not in the same terms as the provisions considered by the courts in those decisions, it is sufficiently similar to give us comfort that the narrow construction which we favour is appropriate. The Trustees have not provided any compelling reason why we would depart from the narrow construction which has been favoured by courts for over 100 years in relation to similar provisions and we do not intend to do so, particularly having regard to the ordinary meaning of the provision, its context and purpose.

99 The related and second issue that arises for consideration is the question of who bears the onus of showing what books, accounts and records are usually kept in relation to the business conducted by the transferor and, relatedly, what is required to discharge that onus.

100 In Re Nancarrow, an Insolvent [1916] SALR 198, among other things, the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia considered the elements required to be proved in order to make out a breach of s 175 of the Insolvent Act 1886 (SA) which, among other things, provided that:

… if any insolvent shall have committed any of the offences in this section mentioned, the Court may, at the time of awarding a certificate to the insolvent, . . . by order, adjudge such insolvent to be imprisoned with or without hard labour, at the suit of the trustee as such judgment creditor as hereinafter mentioned, for any period not exceeding three years from the date of such order; and the messenger of the Court shall, upon receiving the warrant of the Court thereon, lodge the insolvent in gaol.

101 One of the offences included in the section was the failure within three years to keep such books of account as are usual and proper in the business carried on by the insolvent, and as sufficiently set forth his business transactions, and disclosed his financial position. The bankrupt or insolvent (as he was referred to by the court) appealed against two orders, one of which was that within three years prior to the filing of the petition upon which he was made a bankrupt, he failed to keep the books of account required by s 175 of the Insolvent Act in the business of a draper and hawker carried on by him. The bankrupt raised a number of grounds of appeal including, in relation to that determination, that there was no evidence about what books of account are usual in the business of a draper and hawker.

102 In relation to that contention at 213 Murray CJ said:

The effect of the word “usual”, as here used, I take to be as follows. Unless the business carried on by the insolvent is one in which it is usual to keep books, there can be no books which are “usual” in that business, and no offence can be committed either by keeping no books or by keeping books which do not contain the particulars mentioned in the Act. But if the business be one in which it is usual to keep books an offence is committed if no books are kept at all, or if books are kept which, even though they are the “usual” ones, do not sufficiently set forth the insolvent’s business transactions and disclose his financial position.

In this case the insolvent did keep books. He kept two, but as they merely shewed his sales on credit, and contained no record of his purchases on credit, or of his stock in hand, he was clearly guilty of the offence charged, provided his business were one in which it is usual to keep books.

103 His Honour noted that his view of the relevant legislation was in accordance with Re Mutton. He went on to observe that, although no witness was called to prove that it is usual to keep books in the business of a draper and hawker, it was a matter of common knowledge on which no evidence was required, at least in relation to a draper’s business and that, “speaking for [himself]”, his Honour “[could not] believe it possible for anyone to doubt that books are usually kept by a draper”: at 214-215.

104 At 219 Gordon J said that the onus was on the prosecution to prove three things in relation to the charge namely: