Federal Court of Australia

Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs v McQueen [2022] FCAFC 199

ORDERS

MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION, CITIZENSHIP AND MULTICULTURAL AFFAIRS Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal, to be fixed by way of a lump sum.

3. On or before 23 December 2022 the parties file proposed agreed orders as to an appropriate lump sum for the respondent’s costs.

4. In default of any agreement, the matter be referred to a Registrar for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 The appellant Minister appeals from orders of the primary judge made on 23 March 2022, setting aside the Minister’s decision not to revoke the mandatory cancellation of the resident return visa held by the respondent, Mr McQueen. The primary judge upheld one ground of judicial review advanced by Mr McQueen, in respect of the Minister’s decision. The primary judge’s orders and reasons are found at McQueen v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs (No 3) [2022] FCA 258.

2 For the reasons set out below we consider the primary judge’s orders are not affected by the errors, and are correct. The appeal must be dismissed.

3 The cancellation of Mr McQueen’s visa had occurred by operation of s 501(3A) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth). A delegate was satisfied of the preconditions in that provision and was therefore required to cancel Mr McQueen’s visa. The question of whether the visa cancellation should be revoked came before the Minister pursuant to s 501CA of the Migration Act. Section 501CA provides:

501CA Cancellation of visa—revocation of decision under subsection 501(3A) (person serving sentence of imprisonment)

(1) This section applies if the Minister makes a decision (the original decision) under subsection 501(3A) (person serving sentence of imprisonment) to cancel a visa that has been granted to a person.

(2) For the purposes of this section, relevant information is information (other than non‑disclosable information) that the Minister considers:

(a) would be the reason, or a part of the reason, for making the original decision; and

(b) is specifically about the person or another person and is not just about a class of persons of which the person or other person is a member.

(3) As soon as practicable after making the original decision, the Minister must:

(a) give the person, in the way that the Minister considers appropriate in the circumstances:

(i) a written notice that sets out the original decision; and

(ii) particulars of the relevant information; and

(b) invite the person to make representations to the Minister, within the period and in the manner ascertained in accordance with the regulations, about revocation of the original decision.

(4) The Minister may revoke the original decision if:

(a) the person makes representations in accordance with the invitation; and

(b) the Minister is satisfied:

(i) that the person passes the character test (as defined by section 501); or

(ii) that there is another reason why the original decision should be revoked.

(5) If the Minister revokes the original decision, the original decision is taken not to have been made.

(6) Any detention of the person that occurred during any part of the period:

(a) beginning when the original decision was made; and

(b) ending at the time of the revocation of the original decision;

is lawful and the person is not entitled to make any claim against the Commonwealth, an officer or any other person because of the detention.

(7) A decision not to exercise the power conferred by subsection (4) is not reviewable under Part 5 or 7.

Note: For notification of decisions under subsection (4) to not revoke, see section 501G.

4 Mr McQueen made representations to the Minister on 22 November 2019, seeking to persuade the Minister there was “another reason” why his visa cancellation should be revoked, it being common ground Mr McQueen did not pass the character test and therefore the Minister could not be satisfied this was a basis to revoke the visa cancellation. The evidence disclosed that no action was taken under s 501CA in relation to those representations for a long time. The primary judge described the circumstances at [2]:

On 11 December 2020, a senior advisor from the Minister’s office indicated that a decision should be prepared for the Minister’s consideration concerning the representations made by Mr McQueen. That was more than a year after Mr McQueen had made his representations and six months after he had completed his sentence and had commenced being held in immigration detention by reason of the cancellation of his visa.

5 We return below to the findings made by the primary judge about the factual circumstances of the Minister’s decision, none of which were impugned on appeal. On 14 April 2021, and a little more than 24 hours after he received the briefing materials about Mr McQueen’s circumstances and representations, the Minister made a decision not to revoke the visa cancellation.

6 The issue before the primary judge and on this appeal concerns how, given the particular factual circumstances that existed in relation to the Minister’s decision about Mr McQueen, the Minister could lawfully form the requisite state of satisfaction under s 501CA(4), and what was a permissible role in that decision of advice, recommendations and information provided to the Minister by Departmental officers. The issues included whether what had in fact occurred was that the Minister had “rubber stamped” the recommendation of his Departmental officers and had given no actual consideration himself to whether there was another reason to revoke Mr McQueen’s visa cancellation.

7 The primary judge upheld one of Mr McQueen’s grounds of judicial review, and rejected three others. The third and fourth grounds of judicial review were not pursued in the Notice of Contention on the appeal, but the first ground rejected by the primary judge was pursued. In respect of that first ground of judicial review, his Honour rejected the contention that the Minister had “rubber stamped” what had been prepared by his Department, and rejected the contention the Minister had impermissibly delegated the exercise of power under s 501CA(4) to his Departmental officers.

8 The primary judge accepted the second ground of review (or, part of it), and this is the subject matter of the Minister’s appeal. His Honour concluded that the Minister had not personally considered and therefore had not personally understood Mr McQueen’s representations because he had only read the summary of Mr McQueen’s representations provided to him in a departmental submission. The primary judge relied upon the Full Court’s reasons in Tickner v Chapman [1995] FCA 987; 57 FCR 451, and subsequent decisions applying the same approach, including Minister of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs v Douglas [1996] FCA 395; 67 FCR 40 and Carrascalao v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCAFC 107; 252 FCR 352. His Honour distinguished Minister for Aboriginal Affairs v Peko-Wallsend Limited [1986] HCA 40; 162 CLR 24, although he relied upon it in other parts of his reasoning.

9 From the authorities, the primary judge drew five essential propositions, which his Honour set out at [73] of his reasons. He concluded (at [85]):

It follows that the Minister was assisted by departmental officers in undertaking the statutory task in a manner that was not lawful. In doing so, he failed to undertake his deliberative task of forming a personal state of satisfaction by considering and understanding the representations. Instead, he acted on the basis of the summary of the content of those representations provided in the Submission.

10 The Minister raised two grounds of appeal:

(a) The primary judge erred in making the factual finding that the Minister relied upon the submission of his Departmental officers, without reading for himself Mr McQueen’s representations. The Minister contended the Court should find the Minister did read Mr McQueen’s representations and therefore performed the statutory task required of him under s 501CA(4). This ground was advanced accepting for the purposes of the ground (though not otherwise) the proposition that the Minister was required to consider for himself Mr McQueen’s representations, rather than rely on a summary of them from one of his officers.

(b) Alternatively to the first ground, the primary judge erred in concluding that it was not a lawful performance of the Minister’s task for him to do no more than consider the distillation of Mr McQueen’s representations in briefing material from his Departmental officers. The Minister contended this was sufficient for the Minister to have given “proper, genuine and realistic consideration” to the merits of Mr McQueen’s representations.

11 Mr McQueen filed a Notice of Contention on the appeal. The Notice raised the argument rejected by the primary judge in the first ground of judicial review; namely that the evidence disclosed a “de facto system” of delegated decision-making by Departmental officers, and this was what had occurred in relation to the Minister’s decision about Mr McQueen. He contended the decision was not the Minister’s decision at all, it was the decision of the officer who prepared the briefing material and the reasons signed by the Minister. Mr McQueen contended that the reasons were not the Minister’s reasons, and indeed the Minister was only invited to look at the proposed reasons after he had made a decision.

A further debate

12 Aside from these three core issues, as the parties’ arguments developed in writing and orally it became apparent there was a further debate between the parties. This concerned the approach the Full Court should take in considering the Minister’s appeal.

13 The Minister’s submissions were premised on the proposition that the appellate Court is in as good a position as the primary judge to determine matters of fact relevant to the Minister’s appeal. From this premise, the Minister submitted that Mr McQueen bore an onus on the appeal of “demonstrating that the Minister did not read for himself the Respondent’s representations”.

14 Mr McQueen submitted it is the Minister who must persuade this Court that the primary judge made an error in his findings of fact, in particular the finding about the Minister having not read the representations.

15 Once developed in oral argument, the debate subsided. In reply senior counsel for the Minister accepted that:

we have to demonstrate error in the ultimate finding, and we accept that.

16 Senior counsel then submitted this could be done in one of two ways:

It can be done by showing that the primary judge found that the respondent’s onus was discharged when your Honours conclude that it wasn’t, or it can be done by persuading your Honours that the finding opposite to the one that the primary judge made should be made. Either of those would involve a conclusion that the decision of the primary judge involved error. In any event, we have, in fact, descended to the level of identifying why each of the primary judge’s strands of reasoning was in error.

17 We accept that submission. It is plain that the Minister, as the moving party on the appeal, has the burden of persuading the Court that the orders made by the primary judge were affected by error. The appellate jurisdiction of this Court is exercised for the correction of error: Allesch v Maunz [2000] HCA 40; 203 CLR 172 at [23]; Campaigntrack Pty Ltd v Real Estate Tool Box Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 112; 402 ALR 576 at [8] and [282]. Where the appellate Court is satisfied error is established, then the Court is able, subject to such qualifications as those expressed in the authorities concerning the assessment of credibility and reliability of witnesses by a trial judge, to decide the issues in dispute between the parties, including what findings of fact should be made and what inferences should be drawn from the facts as found or agreed: Lee v Lee [2019] HCA 28; 266 CLR 129 at [55]-[56]; ABT17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2020] HCA 34; 269 CLR 439 at [62]; Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 261 FCR 301 at [3]; Jadwan Pty Ltd v Rae & Partners (A Firm) [2020] FCAFC 62; 278 FCR 1 at [410]-[411]; Le v Scott [2022] FCAFC 31 at [2]-[3], [31]-[32].

18 On a judicial review, where a primary judge needs to make findings of fact, in our respectful opinion error is usually likely to be proven on appeal by the second of the two alternatives nominated by senior counsel for the Minister – namely, by the appellant persuading the appellate Court that a different, or “opposite” finding of fact was the correct finding. A conclusion that such an error has been established may well implicitly involve acceptance by the appellate Court that the primary judge should not have found a judicial review applicant had discharged their burden of proof. The more direct way to express this is, as we have explained, to focus on appellate persuasion about the correctness of the findings made by the primary judge.

The Minister’s decision

19 It is not necessary to set out any detail about the Minister’s reasons for refusing to revoke the visa cancellation. The Minister adopted without alteration the draft reasons provided to him by his Departmental officers. However, just as before the primary judge, the legal arguments do not concern the Minister’s reasoning as such. Rather, they concern how the Minister made his decision.

20 The evidence about how the Minister made his decision not to revoke Mr McQueen’s visa cancellation had a number of specific features which should be mentioned. They were all canvassed in the primary judge’s reasons, and his Honour made certain factual findings about them. The Minister did not impugn any of those factual findings, save for one that was critical to the grounds of appeal, being the finding we have summarised at [8] above. Generally, the Minister impugned the primary judge’s characterisation and conclusion of what flowed from those factual findings.

21 The primary judge made the following findings, which are not challenged and can be reproduced from his reasons (at [3]-[8]):

More than four months later, the Minister was provided with a submission from an assistant secretary of his department dated 22 March 2021 (Submission). It attached four documents described as follows:

Attachment 1 Decision Page

Attachment 2 Index of Relevant Material for Mr MCQUEEN

Attachment 3 Statement of Reasons

Attachment 4 Relevant material

The first page of the Submission described its subject as the consideration of the revocation of Mr McQueen’s visa cancellation. It then described his ‘Location’ in the following terms:

Mr MCQUEEN is currently detained at Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre and has been in immigration detention since 12 June 2020. It is recommended that you make your decision during the business week, in view of the immediate effect of any revocation decision on liability for detention.

The reference to ‘liability for detention’ was not explained.

Also on the first page was a table headed ‘Recommendations’. It set out five numbered paragraphs, with options that could be selected. The first page concluded with provision for the signature of the Minister. The recommendations and options for selection were as follows:

1. note that on 13 November 2019 a departmental delegate cancelled the Class BB Subclass 155 Five Year Resident Return Visa of Mr MCQUEEN under s501(3A) of the Act (original decision), and Mr MCQUEEN applied for revocation of that decision under s50lCA of the Act. | noted/please discuss |

2. indicate whether you wish to consider this case personally or refer it to the departmental delegate. | consider personally/refer to departmental delegate |

3. if you decide to consider this case personally, record your decision on, and sign, the Decision Page at Attachment 1. | revoke/not revoke |

4. if you do not revoke the original decision to cancel Mr MCQUEEN’s visa and agree with the reasoning set out in the draft Statement of Reasons at Attachment 3, sign the statement with any amendments you consider necessary. | signed/not signed/ please discuss |

5. if you do not revoke the original decision to cancel Mr MCQUEEN’s visa he will remain in immigration detention until his removal from Australia. | noted/please discuss |

In answer to interrogatories administered by Mr McQueen, the Minister stated that to the best of his information and belief he received ‘the brief’ prepared by the Minister’s department (which I take to be the Submission and attachments) at Parliament House in Canberra on 13 April 2021 around 10.00 am. The Minister’s decision not to revoke the cancellation of Mr McQueen’s visa was made the next day. As to the time and place where the Minister made his decision the Minister said:

To the best of my knowledge, information and belief I made the decision not to revoke the mandatory cancellation of the Applicant’s visa under s 501CA of the Migration Act (Decision) inside my personal residence in North West Sydney at around 4:20pm on 14 April 2021.

Therefore, there was a window of 30 hours and 20 minutes within which the brief was first received by the Minister and the decision was made by him.

The Minister’s decision was recorded by circling the following options as to each of the five paragraphs in the Recommendations (as set out above):

(1) noted;

(2) consider personally;

(3) not revoke;

(4) signed;

(5) noted.

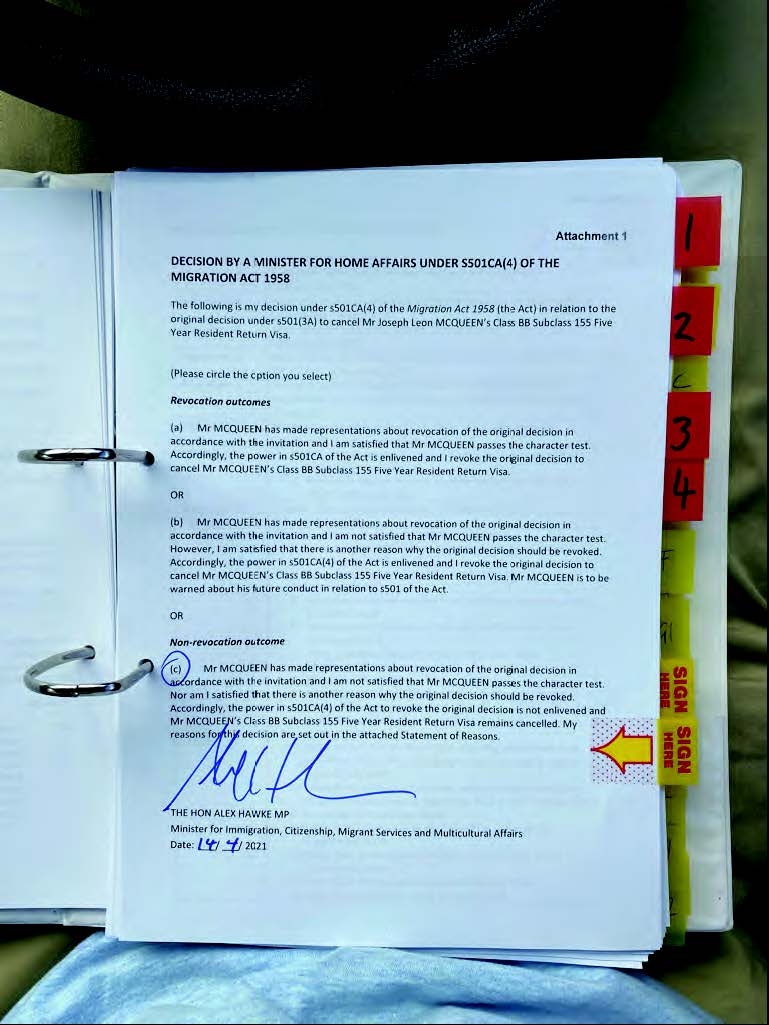

In addition, the Minister circled option (c) on Attachment 1 and signed and dated that page. Attachment 1 was expressed as follows:

DECISION BY A MINISTER FOR HOME AFFAIRS UNDR S501CA(4) OF THE MIGRATION ACT 1958

The following is my decision under s501CA of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (the Act) in relation to the original decision under s501(3A) to cancel Mr Joseph Leon MCQUEEN’s Class BB Subclass 155 Five Year Resident Return Visa.

(Please circle the option you select)

Revocation outcomes

(a) Mr MCQUEEN has made representations about revocation of the original decision in accordance with the invitation and I am satisfied that Mr MCQUEEN passes the character test. Accordingly, the power in s501CA of the Act is enlivened and I revoke the original decision to cancel Mr MCQUEEN’s Class BB Subclass 155 Five Year Resident Return Visa.

OR

(b) Mr MCQUEEN has made representations about revocation of the original decision in accordance with the invitation and I am not satisfied that Mr MCQUEEN passes the character test. However, I am satisfied that there is another reason why the original decision should be revoked. Accordingly, the power in s501CA(4) of the Act is enlivened and I revoke the original decision to cancel Mr MCQUEEN’s Class BB Subclass 155 Five Year Resident Return Visa. Mr MCQUEEN is to be warned about his future conduct in relation to s501 of the Act.

OR

Non-revocation outcome

(c) Mr MCQUEEN has made representations about revocation of the original decision in accordance with the invitation and I am not satisfied that Mr MCQUEEN passes the character test. Nor am I satisfied that there is another reason why the original decision should be revoked. Accordingly, the power in s501CA(4) of the Act to revoke the original decision is not enlivened and Mr MCQUEEN’s Class BB Subclass 155 Five Year Resident Return Visa remains cancelled. My reasons for this decision are set out in the attached Statement of Reasons.

22 In these reasons, the Departmental submission and its attachments will be described as the Departmental brief.

23 The document described as “Attachment 1” in the options presented to the Minister, as signed by the Minister with a specific option selected, was adduced before the primary judge. It was adduced in an unusual form: a photograph of a ring binder, resting on the lap of a person and beneath the steering wheel of a car, open at a document headed “Attachment 1”, with option (c) circled, and with a signature and a date.

24 It is this document which was adduced by the Minister before the primary judge to prove the Minister actually made a decision at all. Therefore, it is a significant document. There was no evidence to explain how or why this photograph was tendered as proof of the Minister’s decision. There was no evidence about why the photograph had been taken, nor by whom.

25 The primary judge found (at [9]):

I infer from the form of the Submission and its attachments and the location in the folder of Attachment 1 that the folder contained what was described by the Minister as the brief from his department comprising, at least, the Submission and the attachments. That is to say, the folder depicted in the photograph is the actual folder that was provided to the Minister.

26 This finding was not challenged on appeal, and is clearly correct.

27 The primary judge continued (at [11]-[12]):

No explanation was given by the Minister as to why the record of the Minister’s decision was produced to the Court in that manner. Nor was any explanation provided as to the circumstances in which the photograph was taken. Submissions were advanced for Mr McQueen to the effect that the photograph was taken in the garage of the Minister’s private residence in Sydney after he had driven from Canberra on 14 April 2021. It appeared to be common ground that the Minister had indeed driven from Canberra to his home in Sydney on that date. Even so, there is no basis to infer that the photograph was taken at the time the Minister made his decision or that it indicates that the decision was made whilst seated in the driver’s seat of a motor vehicle. I make no such finding.

I do infer that the photograph was taken for the purpose of communicating the making of the decision. This is supported by the fact that it depicts what appears to be the brief of materials provided to the Minister by his department and the fact that the photograph was produced to this Court by the Minister as the record of his decision. In the absence of any evidence on behalf of the Minister explaining its circumstances and taking account of the endorsement above the recommendation asking on 22 March 2021 for a decision ‘during the business week’, I also infer that the existence of the relevant record in that form indicates a degree of urgency (albeit belated) in the making of the decision that resulted in the transmission of the photographic record of the decision.

28 At [13], the primary judge found:

Nonetheless, Mr McQueen was notified of the decision to revoke the cancellation of his visa on 27 April 2021 almost two weeks after the decision was made.

29 The photograph also assumed some significance in the arguments on the Notice of Contention. It was contended to indicate some haste and lack of care in the making of the decision, and to support Mr McQueen’s submissions that the Minister did no more than “rubber stamp” a decision already made by his Departmental officers in the Departmental brief, given that only a set of reasons for refusing to revoke the cancellation decision was provided to the Minister.

30 While we place some weight on the photograph in the overall factual context of how the Minister made his decision and its probative value in relation to a sense of urgency with which we deal below, and while we accept the unusual nature of this evidence is material to the consideration of the appeal, it is not necessary to consider the Notice of Contention and therefore we express no view on the ‘rubber stamping’ contentions, and the relevance of the photograph to them.

The primary judge’s reasoning

31 In finding that the Minister did not personally consider Mr McQueen’s representations, the primary judge made the following findings at [79]-[80] of his reasons:

In the present case, the Minister was provided with the Submission which was some 12 pages in length. It attached all of the material that had been submitted by way of representations as well as factual material obtained by the department. It began with the five recommendations. At no point did the Submission indicate that the Minister was required to consider all of the attached material to form his own understanding of the representations and to undertake his own fact-finding based upon that personal consideration where necessary. On the contrary, for the following reasons, the form in which the Submission was expressed and provided to the Minister indicated that personal consideration of that kind was not required, namely:

(1) It provided on the front page for a response by circling options in response to the five ‘Recommendations’.

(2) It provided a very small space for ‘Minister’s Comments’.

(3) It presented in the body of the Submission a summary of the representations made thereby indicating that it was appropriate for the Minister to act upon that summary in forming the required state of satisfaction (being a course that the Minister could not lawfully follow for reasons that have been given).

(4) It invited the Minister to form and record his decision on the Decision Page which contained no suggestion that the Minister was required to personally consider and understand the submissions received.

(5) It was included in a folder of materials with ‘sign here’ tabs on the Decision Page and the signing page for the draft Statement of Reasons.

(6) It proposed a sequential approach by which the Minister recorded his decision on the Decision Page and then turned to the draft Statement of Reasons to see whether he agreed with those reasons when the statutory task required him to undertake his own deliberation based upon a personal consideration of the representations and all the materials, to then form his own reasons (including as to any necessary fact finding) and then consider whether those reasons were adequately expressed in the draft.

(7) Option (c) on the Decision Page (being the option selected by the Minister) did not include any statement to the effect that Minister had personally considered the representations and the factual material and made his own factual findings. It simply recited the fact that representations had been made and stated, relevantly, that the Minister was not satisfied that there was ‘another reason’ why the visa cancellation decision should be revoked.

Having regard to the way in which the Minister was briefed and the absence of any evidence from the Minister or any member of his department (despite the nature of the grounds advanced and the nature of the interrogatories administered), I find that the Minister followed the instruction he was given. He approached the matter on the basis that the Submission afforded a summary of the representations upon which he could lawfully act and that he should first form his view as to whether to make a decision personally, then (if he decided to act personally) he was to form the required state of satisfaction. Thereafter, if he decided not to revoke he should consider the draft Statement of Reasons to see whether they were in accord with his own. He considered those reasons and was satisfied that they accorded with his own view. As to the last step, there is no evidence to suggest that the Minister did not act on the basis of the express terms of the brief and I find that he signed the reasons after reading them and satisfying himself that they expressed his own reasons. I attach no significance to the fact that there were no draft reasons to support a decision to revoke the visa cancellation. Reasons were only required if a decision was made not to revoke.

32 His Honour also relied on the following matters set out at [84]-[85]:

As to the assistance provided by officers of the Minister’s department, I am reinforced in reaching my conclusions to the effect that the Minister acted upon the summary in the Submission by the fact that limited time was available to the Minister to make the decision together with the urgency with which he was asked to approach, and did approach, the task. These are matters which, in the absence of explanation, make it much less likely that the Minister personally read and considered the representations made to him.

No attempt was made by the Minister to justify the Submission as a complete and accurate summary of the representations of [sic] such that the consideration of the Submission may be equivalent to a personal consideration by the Minister of the representations themselves. In any event, the content of the Submission was not of that character. It was not possible to discern the full sense and content of the representations made without regard to the documents in which the representations were expressed. It follows that the Minister was assisted by departmental officers in undertaking the statutory task in a manner that was not lawful. In doing so, he failed to undertake his deliberative task of forming a personal state of satisfaction by considering and understanding the representations. Instead, he acted on the basis of the summary of the content of those representations provided in the Submission.

33 As to his Honour’s reasoning on what is now the Minister’s second ground of appeal, we describe that reasoning in our consideration of ground 2, where appropriate.

Resolution

34 Where necessary, we address the parties’ submissions on the appeal in resolving the grounds of appeal.

Ground 1 of the appeal: the primary judge’s fact finding was wrong

35 The Minister submitted the primary judge erred in two ways. First, the primary judge had overlooked the fact that the statement of reasons signed by the Minister on 14 April 2021 contained two express declarations that the Minister had considered Mr McQueen’s representations and supporting documents.

36 Paragraph 7 of the Minister’s reasons read:

7. I have considered the representations made by Mr MCQUEEN and the documents he has submitted in support of his representations.

37 Paragraph 11 read:

11. In undertaking this task, I considered Mr MCQUEEN’s representations and the documents he has submitted in support of his representations regarding why the original decision

38 The Minister took the Court to Maxwell v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016] FCA 47; 249 FCR 275 at [31] as an example of a case where the Court had relied on a statement in a Minister’s reasons that the Minister had considered “all evidence before [her]” to reject an argument that the Minister had not personally considered representations made to her. Here, the reasons of the primary judge did not explicitly address paragraphs 7 and 11 of the Minister’s statement of reasons.

39 The Minister submitted these paragraphs undermined the primary judge’s reliance (at [79(7)] of his Honour’s reasons) on the absence of a statement in the “Decision Page” of the Departmental brief that the Minister had considered Mr McQueen’s representations. These paragraphs were also contended to undermine his Honour’s reliance (at [79(4)]) on the absence of a suggestion in the Departmental brief that the Minister should consider those representations personally, and his Honour’s reliance (at [84]) on the absence of any affidavit evidence from the Minister (or evidence from a Departmental officer) about whether the Minister had personally considered Mr McQueen’s representations.

40 In relation to the latter point, the Minister submitted he had answered interrogatories directed by Mr McQueen to this topic, and also noted the “well known authorities on the limited circumstances in which an adverse inference will be drawn from a failure by a Minister personally to give evidence”, citing, by way of example, Chetcuti v Minister for Immigration [2019] FCAFC 112; 270 FCR 335 at [82]-[87], [93]-[95].

41 The second fact-finding error alleged by the Minister was that the matters referred to by the primary judge, especially at [79] of his Honour’s reasons, did not support a finding that the Minister had not personally considered Mr McQueen’s representations. The Minister submitted that the primary judge’s finding amounted to an inference that paragraphs 7 and 11 of his statement of reasons were untrue. He contended the primary judge needed a ‘powerful’ basis to draw such an inference, and there was none.

42 Specifically, and contrary to the primary judge’s reasons at [79], the Minister submitted that nothing in the Departmental brief indicated to the Minister that he was not required to consider Mr McQueen’s representations personally. Further, the Minister submitted, there was nothing in the Departmental brief or the context in which it was provided to the Minister to indicate that the Minister was required to make his decision urgently, such that the Minister was rushed into not considering the representations. Even if the decision was required to be made urgently, the Minister submitted there was no basis to conclude he had not read all of the relevant material for himself, given the primary judge’s finding (at [6], [75]-[77]) that there was adequate time for this between the Minister’s receipt of the brief and the making of the decision.

Our reasoning

43 As we explain below under the second ground of appeal, we consider the primary judge was correct to approach this matter on the basis that the Minister was required personally to consider Mr McQueen’s representations to him, and could not rely only on a summary produced to him by his officers in the Departmental brief.

44 The primary judge was correct to find that on the evidence it is more likely than not that the Minister had relied on the summary in the Departmental brief and had not considered Mr McQueen’s representations for himself. On judicial review, a ground like this does require the Court to draw inferences from the evidence as presented. The standard of proof is the balance of probabilities: is it more likely than not that the Minister did not personally consider the representations by the person whose visa has been cancelled? Inferences may be drawn from different aspects of the evidence. Depending on the facts in any given case, one piece of evidence may be sufficient. In other cases, there may be a series of findings and/or inferences drawn which, cumulatively, may persuade the Court to the requisite standard (or may not).

45 Here, the primary judge set out a series of features of the Departmental brief which he found indicated to the reader of that brief that personal consideration of Mr McQueen’s representations was not required. His Honour set those out at [79]. Then at [80] his Honour made findings that the Minister “followed the instruction he was given”. In other words, the findings turned on the way the Minister was briefed, which the primary judge had analysed at [79]. The seven factors in [79] of his Honour’s reasons were both findings of fact based on the uncontested state of the documentary evidence, and inferences drawn from that evidence.

46 As the Minister submitted, in assessing whether the primary judge’s reasoning is affected by error, in the circumstances of this appeal, this Court is in as good a position as the primary judge to assess the evidence.

47 In that context, we see the photograph as probative. We consider it is probative of some sense of urgency around the Minister’s decision making. We say “sense” of urgency because, objectively, there was no apparent need for a decision to be made in a little over a day. Mr McQueen’s representations had been made a long time before these events. The Departmental brief was cleared on 22 March 2021, a considerable time before the brief was put before the Minister. Mr McQueen was not notified of the Minister’s decision until some time after it was made. The Minister could have taken longer to consider the representations and make a decision. However, he did not. As the primary judge found at [6]:

… [T]here was a window of 30 hours and 20 minutes within which the brief was first received by the Minister and the decision was made by him.

48 The brief was received by the Minister around 10am at Parliament House in Canberra. The Minister has sworn the decision was made inside his personal residence in North West Sydney at around 4:20pm on 14 April 2021. We infer that substantial parts of those 30 hours or so are likely to have been occupied with, first, other parliamentary business in Canberra, second, travel to Sydney (it was accepted the Minister travelled by car) and, third, some time for the Minister to be not engaged in work, and to be sleeping, eating and otherwise attending to his personal and family life. Therefore the realistic “window” in which the Minister made a decision was substantially less than 30 hours.

49 For whatever reason, not disclosed on the evidence, there was a sufficient sense of urgency (on the Minister’s part, we infer) that proof of the making of the decision was sent by way of a photograph, indeed a photograph taken on a person’s lap, in a car. Those circumstances plainly indicate some sense of haste around communicating the making of the decision. The only reasonable inference to draw is that, for whatever reason, there was a sense of urgency or haste on the part of the Minister which necessitated sending a photograph of the page of the Departmental brief that indicated what his decision was.

50 The inference that there was a sense of urgency or haste around the making and communication of a decision is one factor that may support a finding that the Minister based his decision on the summary provided by his Departmental officers. By itself it would not be sufficient, but it is one factor. Of course in the particular circumstances of this matter, specifically where the Minister had elected to make the decision personally, had the Minister explained the circumstances in which the decision was made and the purpose of photographing the decision, it would not be necessary to draw such inferences.

51 Unlike the primary judge (see reasons at [12]), we do not infer any need for urgency or haste from the words at the top of the first page of the Departmental brief:

It is recommended that you make your decision during the business week, in view of the immediate effect of any revocation decision on liability for detention.

52 We accept the Minister’s submissions that this is a reference to the practicalities of ensuring a person is immediately released from immigration detention if their visa is restored. Although it may not be a lawful excuse for any delay in releasing such a person, it can be accepted that there may be less staff on duty over the weekends, or at night, both at the detention centre and within the Department, so that communication and release might be practically more complex. In our opinion, this sentence was simply cautious advice from the Department to the Minister to try to ensure that a decision favourable to Mr McQueen could practically result in his immediate release, as the law would have required.

53 Like the primary judge, we attach some significance to the fact that, in the body of the Departmental brief, before a summary of the representations made, appear the words:

The following representations have been made by or on behalf of Mr MCQUEEN in support of his request for revocation.

54 This is likely to encourage the reader to assume the summary is an acceptable substitute for a direct consideration of the representations themselves. As we explain, it is not a summary which in form replicates the way the representations themselves actually appear. Rather, it is a summary organised in a quite different way by Departmental officers.

55 The summary has a number of sub-headings, broadly following the topics set out in Ministerial Direction 79, and to which persons in the position of Mr McQueen have their attention drawn as part of the information and instructions given to them about making representations on revocation. On any view, what is written in this section of the Departmental brief is the author’s view of what should be drawn from the representations, by reference to the topics set out in Direction 79. It is a summary which extends just over seven pages. While the summary contains cross references to the source material of the representations themselves, objectively, a summary presented in this way encourages the reader to rely on it as giving a sufficient picture of Mr McQueen’s representations.

56 Like the primary judge, we find it is of some significance that, immediately after this summary, the Departmental brief invited the Minister to make a decision, and record it on the decision page by doing no more than circling one of the options presented to the Minister. These options were expressly outcome focussed, rather than reasoning focussed. The Minister was not expressly advised he should himself look through the attachments and at Mr McQueen’s representations. For the reasons we explain below, such an exercise is a qualitatively different exercise. Rather, the form of the Departmental brief encouraged the Minister to focus on an outcome, and adopt reasons that had been drafted for him, neither of which directed his personal attention to what Mr McQueen (or his supporters) had said to the Minister, bearing in mind the statute contemplates representations by a person affected to the Minister and the Minister had elected to consider the matter personally.

57 As the primary judge found at [79(5)], the “sign here” tabs, in what was otherwise quite a large folder of materials, were also objectively capable of encouraging the reader to sign off on an outcome based on the summary provided.

58 Further, and in our opinion importantly, the sequence of the Departmental brief was somewhat back to front. This is the point made by the primary judge at [79(6)], and we agree it is a factor to be given some weight. The Departmental brief as presented invited the Minister to record his decision – that is, the outcome, as a first step. This was achieved by the instruction on the very first page of the Departmental brief – “if you decide to consider this case personally, record your decision on, and sign, the Decision Page at Attachment 1”. The summary then followed this first page. Attachment 1 followed the summary. The Minister circled “not revoke” and signed the Decision page as evidenced by the photograph. It was only after all these steps that the Minister’s reasons, drafted by an officer or officers, appeared in the folder with a second “sign here” tab.

59 The fact that Option (c) on the Decision Page did not include any statement to the effect that Minister had personally considered the representations and the factual material and made his own factual findings (see the primary judge’s reasons at [79(7)]) contributes to the overwhelming impression the reader (here, the Minister) would have from the Departmental brief that all he needed to do was look at his officer’s summary. The declaration he signed off on did not suggest otherwise. That is the point of the primary judge’s emphasis, in [79], that:

the form in which the Submission was expressed and provided to the Minister indicated that personal consideration of that kind was not required.

60 We agree.

61 To these we would add the following factors:

(a) The Departmental brief is structured around the considerations in Direction 79, even though this Ministerial Direction under s 499 of the Migration Act is not binding on the Minister for the purposes of a decision made personally. Nevertheless, the officers having chosen that structure, what it does is present a “complete picture” to the Minister of the considerations he should take into account (by reference to the sub-headings under the main heading “Representations”) and the information under each consideration.

(b) There are no markings whatsoever on either the Departmental brief, or on the attachments to the brief. Such markings could have supported an inference that the Minister had given particular attention to some matters, and markings on the attachments could well support an inference that the Minister had looked at those attachments. The absence of markings, alone, would be insufficient to infer the Minister had not read the representations. Nevertheless, it is a further factor that has some probative value, albeit small.

(c) There was a large number of attachments to the Departmental brief; namely 80, comprising 230 pages. Some of these attachments were grouped together but are in fact separate documents. Not all of these were Mr McQueen’s representations, but most were. The primary judge made a finding based on his Honour’s own reading of the attachments that it would take a person in the Minister’s position, familiar with decision making of this kind, at least an hour to read through and consider the representations: see [76]. While the primary judge might have been intending to suggest that the task was therefore not an onerous one (bearing in mind the Minister’s arguments about being able to rely on a summary), in our opinion the size of the representations has other probative value. This decision was made within a relatively small window of time. The Minister appeared to have been sufficiently pressed for time to have a photo of his decision taken in a car and sent as proof he made a decision, instead of handing the folder to his staff or communicating the outcome in a regularised way. In these circumstances, we find it unlikely in the extreme that the Minister devoted any time, let alone a further hour on top of reading the Departmental brief, to considering the representations himself. The primary judge made a similar finding at [84] of his Honour’s reasons.

62 In reaching that conclusion, and with respect, we would not give the same emphasis to all of the factors set out by the primary judge at [79] of his Honour’s reasons. We do not consider that the small space for the Minister’s comments is indicative of a likelihood one way or the other in terms of the Minister examining the representations themselves. It is clear from the photograph that the Minister had a hard copy of the documents, and could have annotated them as he saw fit when considering them. He did not need the comment box. We find, in the circumstances, if the Minister needed to speak to one of his Departmental officers, it is unlikely he would have communicated with them using the comment box, and it is more likely (again given what the photograph might indicate) that he would have contacted them in another way.

63 As the Minister submitted, there are also two passages in the reasons drafted by Departmental officers and adopted by the Minister which tend against the primary judge’s findings. The first is at [7]:

I have considered the representations made by Mr MCQUEEN and the documents he has submitted in support of his representations

64 The second is at [10]-[11]:

As I am not satisfied that Mr MCQUEEN passes the character test, I have considered, in light of Mr MCQUEEN’s representations, whether I am satisfied that there is another reason why the original decision should be revoked.

In undertaking this task, I considered Mr MCQUEEN’s representations and the documents he has submitted in support of his representations regarding why the original decision should be revoked.

65 The Minister relies on what was said in Maxwell at [31], citing Ayoub v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] FCAFC 83; 231 FCR 513 at [49] (per Flick, Griffiths and Perry JJ). In Maxwell, Perry J said:

As to the second issue, it can be inferred from the evidence that the Minister adopted the draft reasons prepared by the Department: see by analogy in Javillonar v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (2001) 114 FCR 311 (Javillonar). In those circumstances, the fact that the Minister’s reasons were not prepared by the Minister personally is not relevant: Javillonar at [24]. In particular:

(1) The Department’s brief to the Minister contained all of the relevant material to the decision whether or not to cancel the applicant’s visa (see above at [14]).

(2) In making the cancellation decision, the Minister signed the following statement:

I have considered all relevant matters including an assessment of the character test as defined by s501(6) of the Migration Act 1958, and all evidence before me provided by, on behalf of, or in relation to Mr Raymond Wilson MAXWELL in connection with the possible cancellation of his Class BB Return (Residence) Subclass 155 (Five Year Resident Return) visa.

In so doing, the Minister confirmed that she had personally considered the issues paper and all of the material relied upon by the applicant. In any case, it can be inferred that the Minister considered all of the material before her: Ayoub v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 231 FCR 513 (Ayoub) at [49] (Flick, Griffiths and Perry JJ).

(3) The Minister made a decision consistent with the draft reasons prepared by the Department.

(4) By crossing-out the “non-cancellation outcomes” on the front page of the issues paper and signing the base of that page, the Minister expressed her intention to select the “Cancellation outcome” option which expressly adopted the draft reasons in stating that “[m]y reasons for this decision are set out in the attached Statement of Reasons” (emphasis added).

66 However, as the Full Court made plain in Folau v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCAFC 214; 256 FCR 455 at [91], the application of such an approach, and the drawing of any inference, will depend on the facts in each case. In Folau, the Full Court said at [89]-[90]:

One might reasonably ask why Parliament would provide the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection with a personal power to cancel a visa (as an alternative to having the decision made by a delegate), and oblige the Minister to give reasons for doing so, if Parliament understood or intended that in every case the Minister would adopt, without change, the draft reasons prepared by departmental officers. Such a practice has a tendency to undercut Parliament’s intention to provide a right to merits review where a visa cancellation decision is made by a delegate rather than by the Minister personally.

The power for the Minister to personally decide to cancel a visa pursuant to s 501(2), coupled with his obligation to provide reasons for the decision pursuant to s 501G, cannot mean that it is permissible to merely rubber stamp reasons prepared by the Department, and the Minister is required to do more than just review reasons prepared by somebody else. The Minister must engage in an active intellectual process (Carrascalao v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2017) 252 FCR 352 at [46] (Griffiths, White and Bromwich JJ)) and he must give proper, genuine and realistic consideration to the merits of the particular case: Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZJSS (2010) 243 CLR 164 at [29] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ). Before adopting any draft reasons as his own the Minister must decide that they accurately reflect his own reasons: W157/00A at [39].

67 However, in Folau at [92], the Full Court concluded, as a matter of fact:

In the present case the materials show that the Minister:

(a) was provided all the relevant materials to make a personal decision in relation to Mr Folau’s case;

(b) selected the option in the Submission which stated that he wished to consider Mr Folau’s case personally, and signed and dated it;

(c) selected the “cancellation outcome” in the pro forma decision which included statements that the Minister had decided to exercise his discretion to cancel Mr Folau’s visa and that “[m]y reasons for this decision are set out in the attached Statement of Reasons”, and signed and dated it; and

(d) signed and dated the draft reasons.

That provides a strong basis to conclude that the Minister gave proper consideration to the merits of Mr Folau’s case and after doing so adopted the draft reasons as his own reasons. While the admitted facts point to a contrary inference, they are insufficient to outweigh what are, in effect, express statements by the Minister that he personally made the decision for the reasons he signed and dated.

68 As the Minister pointed out, those same facts are present in the current case.

69 However, the finding of the primary judge impugned by ground 1 is not the same as the question whether the Minister “rubber stamped” reasons prepared by others, or did not genuinely adopt the drafted reasons as his own. Those matters arise on the Notice of Contention, which is not necessary to decide.

70 The primary judge’s finding was different. It was about whether the Minister had, personally, considered Mr McQueen’s representations rather than only considering his Department’s summary of them. In the context of that finding, and contrary to the Minister’s submissions, it is not necessary to find the Minister was “dishonest” in the two passages in his reasons extracted above. Indeed, it is likely that, in accordance with the instructions from his Departmental officers, the Minister was content to adopt those statements in the draft reasons because he had considered his Department’s summary of the representations. These passages in the reasons more likely than not indicate the Minister, like the author of the draft reasons, equated the Departmental summary with the representations themselves. These two passages do not affect our view that the primary judge was correct to find that the Minister had not personally read and considered Mr McQueen’s representations, but had relied on the summary provided to him.

71 In oral argument, senior counsel for the Minister submitted that it was “not the natural process” to make the finding made by the primary judge. We understood this to suggest there was or should be some presumption that the Minister did indeed directly look at Mr McQueen’s representations because they were part of the material given to him.

72 We do not accept that submission. This is an unusual and somewhat bizarre factual situation. There is nothing “natural” about the process disclosed by the evidence. In circumstances of no objective urgency or pressing expedition and after long Departmental delays, the Minister gives himself not much more than a 24 hour period in which to make a decision with profound effects for Mr McQueen’s life, a period during which the Minister drove (or was driven) from Canberra to Sydney and which included a period of time overnight, and where the Minister has sworn that he made his decision inside his residence in Sydney but then for some reason the proof of the decision is a photograph taken on the lap of a person in a car. If the process had been interrogated further, perhaps a clearer picture would have emerged. In these circumstances, there is no room for any presumptions or assertions about what is, or is not, a “natural” decision-making process.

73 The first ground of appeal must be rejected.

Ground 2 of the appeal: it was permissible for the Minister to read and consider only the summary by his officers

74 The Minister submitted that he was not required to consider personally or directly any of the actual documents submitted by Mr McQueen and comprising the representations. Rather, he was only required to consider the substance of those representations, and that could be achieved by considering and relying on the summary in the Departmental brief.

75 In support of this submission, the Minister referred to Peko-Wallsend at 30-31, Tickner at 464-465, 476-477 and 497, Tervonen v Minister for Justice and Customs (No 2) [2007] FCA 1684 at [28]-[29], Carrascalao at [61] and ERY19 v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs [2020] FCA 569 at [59].

76 The Minister submitted that the primary judge’s conclusion was not accompanied by any finding identifying any particular material error or deficiency in the brief. In the Minister’s submission, the Departmental brief was an accurate and fair summary of Mr McQueen’s representations and supporting materials. The Minister also submitted that the brief quoted the source material directly where appropriate and identified where in the documents themselves that information could be found.

77 The Minister contended his submissions were consistent with the plurality reasons in Plaintiff M1/2021 [2022] HCA 17; 400 ALR 417 at [23]-[27]. The plurality said at [23]-[24]:

It is, however, improbable that Parliament intended for that broad discretionary power to be restricted or confined by requiring the decision-maker to treat every statement within representations made by a former visa holder as a mandatory relevant consideration. But the decision-maker cannot ignore the representations. The question remains how the representations are to be considered.

Consistently with well-established authority in different statutory contexts, there can be no doubt that a decision-maker must read, identify, understand and evaluate the representations. Adopting and adapting what Kiefel J (as her Honour then was) said in Tickner v Chapman, the decision-maker must have regard to what is said in the representations, bring their mind to bear upon the facts stated in them and the arguments or opinions put forward, and appreciate who is making them. From that point, the decision-maker might sift them, attributing whatever weight or persuasive quality is thought appropriate. The weight to be afforded to the representations is a matter for the decision-maker. And the decision-maker is not obliged “to make actual findings of fact as an adjudication of all material claims” made by a former visa holder.

(Footnotes omitted.)

Our reasoning

78 The importance of the exercise of making representations to provide “another reason” why a person’s visa cancellation should be revoked should not be understated. Individuals in this situation are facing imminent removal from Australia and those in Mr McQueen’s position are deprived of their liberty. They have served the sentences imposed on them for their crimes and in that sense have paid the price the Australian justice system has demanded of them. Like Mr McQueen, they may have been in Australia a long time, and they may have established family connections here, so that the ripples of the effects of their removal are likely to be both widely and deeply felt.

79 Invariably, due to the preconditions in the mandatory cancellation provision, they are persons who have committed serious criminal offences, offences which Australian courts have decided justify a substantial term of imprisonment. They are persons who will on any view have a significant persuasive burden to advance “another reason” why their visa cancellation should be revoked so that they are able to remain lawfully in Australia.

80 In other words, the representations to which s 501CA(4) is directed are an exercise in persuasion, when the odds are already stacked against the individual affected. That is both the practical and the statutory context in which Parliament has imposed an obligation on a decision-maker to consider an individual’s representations. By conferring a power to revoke a visa cancellation made without reference to personal circumstances and without natural justice, Parliament has contemplated that a decision-maker can be persuaded to exercise the revocation power.

81 It is in that context that what was said by the High Court in Plaintiff M1 at [24] is to be understood. Their Honours recognised in this paragraph the exercise was a persuasive one and to that extent, the passage referred to by the Minister and set out above does not assist the Minister.

82 Where the primary repository of the power, the Minister, has a choice whether to exercise the power personally, or to delegate it, the election to exercise the power personally has consequences for the manner in which the power can be lawfully exercised by the Minister. The satisfaction about whether a person’s representations provide “another reason” to revoke the visa cancellation must be the Minister’s personal satisfaction about those representations, formed by having directly considered those representations, not another person’s summary of them. As the primary judge noted at [63] of his Honour’s reasons, this is all the more so since there is no right to merits review where the Minister makes the decision personally:

Plainly, where the Minister acts personally, it is the Minister who is to be accountable for the performance of the responsibility to consider the representations in order to undertake the particular deliberative task required by s 501CA (4).

83 We respectfully agree.

84 The authorities relied on by the Minister simply do not address the point now in issue. As the passages in Carrascalao at [61]-[62] indicate, in that case the Minister had been advised that he needed to look at some matters personally. Carrascalao was also concerned with a different issue of the adequacy of the time available to the Minister to consider the revocation request. Otherwise, the Full Court explained why it was permissible for a Minister to be assisted by Departmental summaries, and the contrary is not suggested here. Summaries provide a useful focus, but they do not relieve the repository of the power from the obligation to directly consider the representations made. So much is reinforced by the fact the Minister elected to consider the representations personally. It may be accepted that Ministers are under time pressures and it is appropriate for them to be assisted by their Departmental officers. However, once made, the choice to consider a matter personally carries with it the obligations to which we have referred.

85 In Tervonen at [28]-[29], Rares J made some broad statements of principle about the way a Minister might lawfully exercise a statutory power with the assistance of Departmental officers. His Honour made it clear that he considered these principles applied to a power that was required to be exercised personally by the Minister. We take that to mean, given his Honour was dealing with the power in s 16 of the Extradition Act 1988 (Cth), a power for which Parliament had provided no express power of delegation. As the Full Court did in Carrascalao, his Honour pointed out that material deficiencies or inaccuracies in, or a relevant consideration omitted from, any summary provided could vitiate the Minister’s exercise of power (referring to the example of Peko-Wallsend). In Tervonen, his Honour was dealing with a statutory power at the commencement of the Extradition Act process, not at the end of the process. The Extradition Act process provided a future right to a full hearing under s 19 on whether or not a person is an extraditable person. It then provided a right of a full de novo review in the Federal Court, and then a further separate decision by the Attorney-General under s 22 of the Extradition Act. His Honour was dealing with a power that was not delegable. In those circumstances, a court might more readily impute to Parliament an intention that the power conferred at Ministerial level did not depend for its lawful exercise on a Minister having to digest and understand the primary source material before them.

86 ERY19 dealt with a different statutory power in s 501 of the Migration Act, namely the power to refuse a protection visa application. It was also dealing with a different factual situation (reliance on an Interpol Red Notice where contrary information to the notice was available to the Department), and different errors alleged (legal unreasonableness). In that different context, the Court had occasion to refer to the dicta in Peko-Wallsend about the qualifications to the proposition that a Minister can rely on a summary of facts provided by Departmental officers. The re-statement by the Court of that dicta for another purpose does not cause us to alter our opinion about the different statutory context in the present appeal, and the correctness of the approach taken by the primary judge.

87 The power in s 501CA(4) is quite unlike the statutory power in Peko-Wallsend. Mason J summarised the power in Peko-Wallsend in this way (at 33):

In summary then, where the Commissioner has made a report under s. 50(1) (a) recommending a grant of land and the Minister is satisfied that the grant should be made, the Minister must recommend to the Governor-General that the land be granted to the Land Trust. Section 12(1) (a) empowers the Governor-General to execute a deed of grant of an estate in the land in accordance with the Minister’s recommendation.

88 In other words, the matter did not come before the Minister until there had been a full inquiry and recommendations by a Land Commissioner. In those circumstances, it is unsurprising that two of the five members of the Court expressly confirmed that the Minister could rely on his Departmental officers to prepare information for him to decide whether to make a recommendation. There may indeed be a number of powers reposed in Ministerial office holders where the effective conduct of the business of government either engages the principles set out in Carltona Ltd v Commissioners of Works [1943] 2 All ER 560 or, in a similar vein, suggests Parliament contemplated a power might be exercised on the basis of a summary of the relevant information being provided to a Minister. The nature and circumstances of the particular statutory power will be critical.

89 We accept that in Peko-Wallsend at 31, Gibbs CJ appears to assume it is legally permissible for a Minister to rely “entirely on a departmental summary”. His Honour’s statement cannot simply be picked up and applied at face value to every statutory power reposed in a Minister. In our respectful opinion, it is not applicable to the power presently under consideration. Especially so where, as here, Parliament has given the Minister a choice as to whether to exercise the power personally or delegate it, and has attached different consequences – in terms of merits review – depending on the choice made. A decision by the Minister personally to exercise the s 501CA(4) power deprives a person of a right to merits review (see s 501CA(7), and cf s 500(1) (ba)), deprives them of a hearing and of a fresh decision on possibly different material. It means the representations cannot be added to, or explained, or emphasised; they stand or fall as they are. Peko-Wallsend was not such a case. Nor was Tervonen.

90 Further, the statutory power in s 501CA(4) affects liberty. It also affects a person’s ability to remain lawfully in Australia. These are the most profound of consequences for an individual. The occasion for the exercise of the power is a “last resort” situation, where a person’s visa has already been cancelled, without notice or natural justice. Parliament had identified the satisfaction of the repository of the power as the condition upon which the revocation power should be exercised, and the only opportunity the affected individual has to persuade the Ministerial repository of the power to exercise it favourably is through the representations they have been invited to make.

91 We agree with the primary’s judge’s conclusion at [85] that:

It was not possible to discern the full sense and content of the representations made without regard to the documents in which the representations were expressed.

92 Returning finally to Tickner, and the passages relied upon by the Minister from the Full Court’s decision, it is appropriate to recall the factual and legal circumstances of that case. The power in issue arose under s 10 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth), which relevantly provided:

(1) Where the Minister:

(a) receives an application made orally or in writing by or on behalf of an Aboriginal or a group of Aboriginals seeking the preservation or protection of a specified area from injury or desecration;

(b) is satisfied:

(i) that the area is a significant Aboriginal area; and

(ii) that it is under threat of injury or desecration;

(c) has received a report under subsection (4) in relation to the area from a person nominated by him and has considered the report and any representations attached to the report; and

(d) has considered such other matters as he thinks relevant;

he may make a declaration in relation to the area.

93 Several matters should be noted. First the subject matter of the legislative scheme and the relevant power involves the protection of Aboriginal heritage, with the wide public interest and purposes considerations which inhere in such subject matter. Second, the occasion for the exercise of the power arises after a report has been prepared by a person nominated under s 10(1)(c) of the Heritage Protection Act, and that person has invited, received and then given “due consideration” to representations made by members of the public, and attached them to the report. In Tickner, 400 representations had been made by members of the public to the reporter, Professor Cheryl Saunders. The purpose of the notice and representations provisions was described by Black CJ in the following terms (at 456):

The legislative intention revealed by this scheme is that interested members of the public should have an effective opportunity to provide information and express opinion concerning the important issues involved in the consideration of an application under s 10(1). The intention is that the Minister should make an informed decision on all relevant questions, with input from interested persons: see Tickner v Bropho at 194. The Parliament no doubt intended that the “interested persons” would include those who might oppose the making of a declaration as well as those who might support it.

94 Third, the s 10 declaration power is not delegable: see Tickner at 462 and 476. It must be exercised personally by the Minister. On this point, at 462, Black CJ explained the difference between this legislative scheme and others considered in previous authorities, including Peko-Wallsend:

It is not surprising that the Minister should be required personally to participate in this way in a process that may lead to a declaration under s 10. The powers given to the Minister under the Act for the purposes of protecting Aboriginal heritage are capable of affecting very seriously the interests of third parties, and for this reason the Parliament has provided for decision-making at the highest level. It is this feature of the scheme of the Act - the explicit requirement that the Minister consider the representations - that removes the process under s 10 from the general rule that a Minister is not expected to do everything personally: see the observations of Brennan J in FAI Insurances Ltd v Winneke (1982) 151 CLR 342 at 416 adopting Lord Reid’s comments in Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40 at 72; cf O’Reilly v Commissioners of State Bank of Victoria (1983) 153 CLR 1 at 11-12 per Gibbs CJ. The express requirement that the Minister consider the representations also gives rise to a more precisely defined duty binding on the Minister than the Minister’s duty to consider matters in connection with satisfying himself or herself that a grant of land should be made under s 11 of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth): cf Minister for Aboriginal Affairs v Peko-Wallsend Ltd (1986) 162 CLR 24 at 30-31 per Gibbs CJ, at 37-39 per Mason J and at 63- 65 and 65-66 per Brennan J.

The requirement of substantial and non-delegable personal ministerial involvement is consistent with the evident intention of s 10, as I have described it earlier in these reasons, that interested persons will have an effective opportunity to provide information and to express opinion concerning important issues involved in the consideration of an application under s 10(1) and that the decision-maker, the Minister, shall make an informed decision on the questions in issue, having considered the representations of interested persons.

It must also be remembered that the obligation to consider, imposed separately upon both the reporter and the Minister, is an obligation to consider each representation. The degree of effort that the consideration of a particular representation may involve will of course vary according to its length, its content and its degree of relevance.

95 Fourth, despite the existence of a reporting function during which the representations had been considered by the reporter and were required to be “reflected” in the report, and a requirement for the Minister to consider the report, the Full Court held the Minister was required personally to consider the representations.

96 At 464, Black CJ made an observation which could equally be made of the Departmental brief, even though the latter could not be equated in any way with a report under s 10 of the Heritage Protection Act:

A report, written after due consideration of the representations by the reporter, might or might not, “reflect” them. In either event, the section makes it clear that the Minister must personally consider the representations and it is the representations that must be contemplated, not another document which is thought by someone else “adequately to reflect” the representations.

(Emphasis added.)

97 The Chief Justice then made (at 464) some observations about the assistance the Minister could have, in performing his task. These passages do not assist the Minister’s ground of appeal in this case, and tend against it.

This does not mean that the Minister is denied the assistance of a staff member in the process of considering the representations. A staff member might, for example, sort the representations into categories. He or she might put together all the representations that are in common form so that they can be considered together. In some cases, a summary of technical supporting material, such as legal and financial documents, might be provided and it would certainly be in order, in my view, for a competent staff member to assist the Minister by making sure that supporting technical documents were what they purported to be. I would not rule out the possibility of some representations being quite capable of effective summary, yet there would be other cases where nothing short of personal reading of a representation would constitute proper consideration of it.

Examples of the sort of representation that would need to be read personally may be found amongst the 400 or so representations forwarded with, and notionally attached to, Professor Saunders’ report. Some of these make important points by the use of photographs and the form of some representations conveys meaning in other ways. Such representations need to be seen to be “considered”.

(Emphasis added.)

98 These passages emphasise, first, the distinctions in fact and legislative scheme between the Heritage Protection Act and the power in s 501CA(4). In Tickner, the Minister had 400 representations to deal with; that is because the public at large had been invited to make representations. The subject matter of the proposed declaration was a matter of public interest. That factor alone would account for significant variations between the content of the representations and his Honour’s observation that some might be capable of “effective summary”. Second, the Chief Justice explains why some representations need to be “seen” to be considered, by references to photographs. In our opinion, the same reasoning applies to a number of the representations made on behalf of Mr McQueen, as we explain below. This is what the passage in bold illustrates; even with a broad power conferred for public purposes where hundreds of representations might be made, the Court construed the language of the statute as requiring the Minister personally to read the representations in order to “consider” them.

99 Burchett J made a similar point at 477.

Undoubtedly, he may receive the assistance of staff, but ultimately it is for him, in a case involving s 10, to fulfil the requirement expressed in the statute by the words “has considered the report and any representations attached to the report”.

…

Although he cannot delegate his function and duty under s 10, he can be assisted in ascertaining the facts and contentions contained in the material. But he must ascertain them. He cannot simply rely on an assessment of their worth made by others …

100 Complete reliance on a summary prepared by Departmental officers is an assessment of the worth of the representations by others.

101 We note that Kiefel J said at 407:

I have earlier said that the Minister may seek the assistance of his staff. A “consideration” of the representations does not in my view require him to personally read each representation. But it may be as well for him to do so, for if his staff are to convey what is contained within them they must do so in a way which provides a full account of what is in them. If they do not, the Minister will not have considered something he is obliged to, and in this respect the observations of Gibbs CJ in Peko-Wallsend at 30 as to what results are apposite. It may vitiate his decision.

102 A number of points may be made about her Honour’s observations. First, this was dicta, and went further than the other two members of the Court. Second, her Honour was careful to say “does not in my view require him to personally read each representation” (emphasis added). Taken in that way, her Honour appears to agree with Black CJ that how much of a representation, or representations, the Minister must actually read might be a question of fact and degree.