Federal Court of Australia

Century Legend Pty Ltd v Ripani [2022] FCAFC 191

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent NINA RIPANI Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 November 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave is granted to the appellant to amend the notice of appeal in the form of the document provided to the Court on 8 August 2022.

2. The appeal is allowed.

3. The orders made in proceeding VID 266 of 2020 on 18 March and 13 April 2022 are set aside.

4. Pursuant to ss 28(1)(f) and 30 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) there be a new trial of the proceeding:

(a) limited to the issue of whether the respondents continued to rely on the misleading or deceptive conduct of the appellant within the period April 2017 to the date the contract of sale became unconditional in August 2017, and if resolved in favour of the respondents, the relief that should be granted; and

(b) on the basis that:

(i) the parties are bound by each other finding of fact and determination made by the primary judge, save for the findings and determinations relevant to (a);

(ii) the parties may adduce such evidence and may make such submissions in accordance with such case management orders as the judge who hears the new trial thinks fit; and

(iii) all questions of costs of the trial before the primary judge are to be determined by the judge who hears the new trial.

5. The orders made by Beach J on 28 March 2022 are dissolved.

6. Within 7 days the parties are to provide written submissions of no more than 5 pages on the question of the costs of the appeal.

7. Subject to any further order of the Court, the costs of the appeal will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC AND MCEVOY JJ:

1 We have had the advantage of reading the reasons in draft prepared by McElwaine J. We are grateful to his Honour for the clear outline of the relevant facts, and his comprehensive consideration of the issues raised by the appeal. We agree with the conclusion his Honour has reached that the appellant should have leave to amend the appeal grounds, that the primary judge erred in the conclusion expressed at paragraph [215] of the primary judgment that the evidence of Ms Kate Hart should be rejected as reconstructed and unreliable, and that the primary judge’s conclusion in this respect cannot stand. We also agree with McElwaine J that as this conclusion was a fundamental part of the liability finding it follows that ground one of the appeal must succeed, the appeal must be allowed, and the orders made by the primary judge on 18 March and 13 April 2022 must be set aside.

2 We also agree with his Honour that appeal grounds two, three and four do not succeed.

3 Notwithstanding the complexities which will undoubtedly attend a new trial of the proceeding limited to the issue upon which ground one succeeds, we agree with McElwaine J that there is no practicable alternative and, accordingly, with the orders his Honour would make for the conduct of that trial. We agree also with the orders his Honour would make dissolving the orders made by Beach J on 28 March 2022, and in relation to the costs of the appeal.

I certify that the preceding three (3) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Markovic and McEvoy. |

Associate:

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MCELWAINE J:

4 This case illustrates the inherent risk for a vendor in the marketing of an “off-the-plan” apartment development where the ability to construct a building does not ultimately match the pre-development promotional material, despite the inclusion of disclaimer and exclusion clauses in the formal contract of sale.

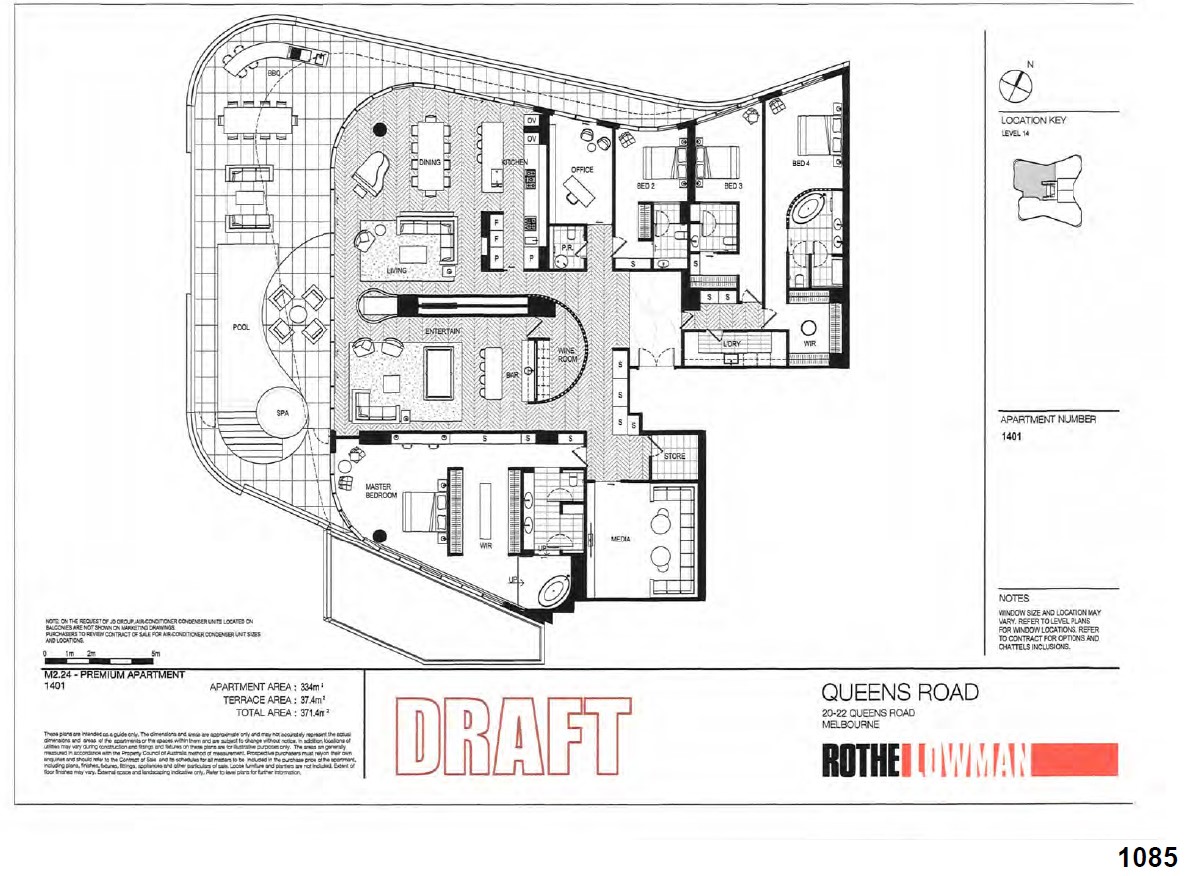

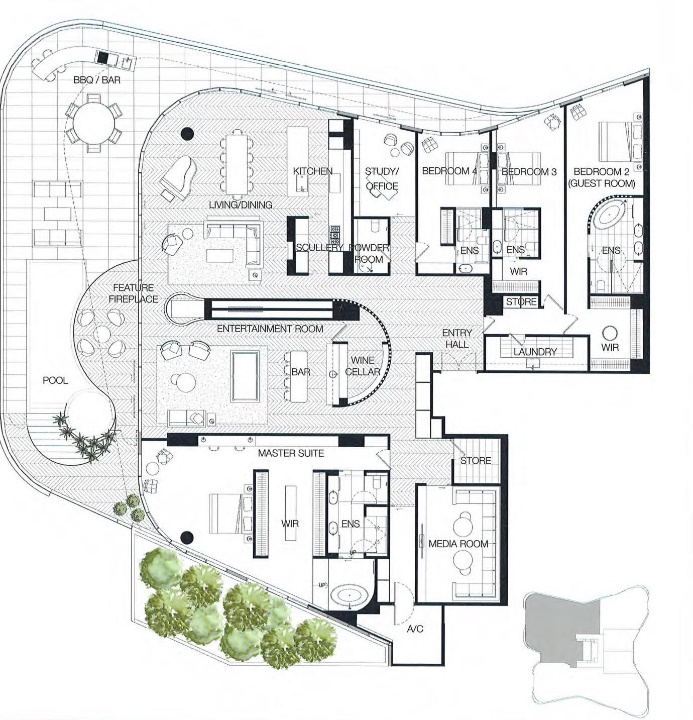

5 On 1 April 2017, Mr Walter and Mrs Nina Ripani (the respondents) signed a conditional contract to purchase apartment 1401 at a price of $9.58 million in an apartment complex to be developed at 20-22 Queens Road, Melbourne to be known as the Victoriana (the contract and the development respectively). Century Legend Pty Ltd (Century or the appellant) was the developer and is the vendor. It traded as the JD Group. The contract became unconditional upon provision of a bank guarantee and approval of a floor plan on 29 August 2017. Completion of the development was achieved in August 2021. The respondents did not complete the contracted purchase for the reason that on 22 April 2020 they commenced proceedings in this Court and sought relief to the effect that the contract be declared void ab initio pursuant to s 243 of the Australian Consumer Law being schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (the ACL) in consequence of misleading and deceptive conduct by the vendor and its agents contrary to s 18 of the ACL. They also sought rescission of the contract in equity together with consequential damages.

6 The primary judge conducted a trial of the proceeding on various dates between January and April 2021. For reasons published on 18 March 2022, his Honour upheld the claim, ordered that the contract “be rescinded”, awarded costs in favour of the respondents and made consequential orders for the assessment of damages: Ripani v Century Legend Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 242 (PJ). Subsequently, on 13 April 2022, his Honour awarded damages to the respondents in the agreed amount of $118,500.

7 On 24 March 2022, Century filed a notice of appeal from the whole of the orders of the primary judge and on 28 March 2022, Beach J made orders staying certain orders pending the hearing and determination of the appeal. Thereafter, the appellant on 11 July 2022 sought leave to rely upon amended grounds of appeal together with leave to adduce new evidence. At the hearing of the appeal, we refused leave to adduce new evidence (and consequentially refused leave to rely on ground five of the proposed amended appeal grounds) for the brief reason that we were not satisfied that the evidence could not have been adduced at the trial; reserved for later publication our more detailed reasons why; heard argument upon the extant and proposed appeal grounds and reserved our decision on the application to amend the appeal grounds.

8 For the detailed reasons that follow, I would grant leave to amend the appeal grounds, uphold ground one and order that there be a new trial limited to the issue upon which ground one succeeds on the basis that the parties remain bound by each other finding of fact and determination of the primary judge.

The conduct complained of

9 In 2016, Century prepared promotional materials to be used in marketing the development, including scale models and a hard-bound brochure containing various images, known as “renders”, of the anticipated appearance of the development once constructed. It also engaged a firm of real estate agents, CBRE, to assist in the marketing of the development and to establish a display suite located at the Queens Road site. Mr Kevin Tran was employed by CBRE.

10 Central to the dispute between the parties is the following render, described as the “hero render” in the primary judgment:

(the render)

11 What is obvious is that the render depicts the proposed western aspect of apartment 1401, and specifically it is to be noticed that it depicts a large free span opening between an external terrace and the internal living spaces with no variation in height between the outdoor and indoor floor levels. The render was used to market both apartment 1401 specifically and the development more generally and was used prominently in promotional and marketing material. It bears the small notation: Artist Impression.

12 The render is not scaled or dimensioned. It was not provided with a locational map from which one might be able to accurately assess the point within the proposed development from which it was constructed. No detail was provided as to the camera lens or the angle of view. No representation was made to the respondents as to the width of the opening depicted in the render when it was first shown to them. The respondents gave evidence, which the primary judge accepted, that they assumed the width to be in the order of 12m, which was the length subsequently discussed at a meeting with a firm of quantity surveyors. Importantly however, the respondents did not plead a claim to the effect that any particular representation was made about the opening width. They did however plead that when they discussed the render with Mr Tran during a visit to a display suite, he told them that the render was of apartment 1401 and they could expect that the apartment would conform to it when built.

13 In their amended statement of claim, the respondents contended that the render conveyed representations that were misleading or deceptive within the meaning of s 18 of the ACL, and sought orders in the nature of rescission of the contract, either under ss 237 and 243(a) of the ACL or, alternatively, in equity. Specifically, the claim pleaded that the render and the statement of Mr Tran conveyed the following representations about the proposed form of apartment 1401:

(a) a large open plan space and a large rooftop terrace both at the same level with a raised concrete and glass swimming pool and a retracted glass three stack window panel system with the resultant defect that the outside and the inside formed a seamless single space (flow-through design);

(c) that the inside and outside of the apartment would flow seamlessly into one another;

(d) when constructed, the apartment would accord with the render and in particular would include the flow-through design;

(e) the flow-through design was in accordance with architectural designs prepared by the commissioned architects;

(f) the building design shown in the render accorded with the design for construction of the building prepared by a reasonably skilled and competent architect; and

(g) the building design shown in the render was achievable given existing building methods.

14 Ultimately, it was not in dispute before the primary judge that for technical reasons related to wind loadings and compliance with Australian standards, the maximum width of the opening that could be achieved for apartment 1401 was approximately 3.4m. Nor was it in dispute that Century knew that it was not possible to construct apartment 1401 with a large free span opening as depicted in the render: it had been informed of that fact by its appointed architect in October 2016 (then Carr Design) and, indeed, was told that the render was “misleading” to that extent. The subsequently appointed firm of architects, Rothelowman, repeated that warning in June 2017. A Ms Kate Hart, who was employed by Rothelowman, had the primary dealings with the respondents in the development of their bespoke requirements for the apartment. She and the respondents also dealt with Mr Jierong (Peter) Hu, an employee of Century.

How did the primary judge proceed?

15 The primary judge considered that the respondents’ claim for relief turned upon three questions as follows (at PJ [9]-[10]):

…First, did the render convey the representations as alleged by them, essentially that there would be a free span opening and seamless transition between the internal living areas of the apartment and the terrace? Second, did the Ripanis rely upon any representations conveyed by the render at the time they entered into the contract to purchase the apartment? Third, would the Ripanis have entered into the contract to purchase apartment 14.01 had they not believed at the time that the apartment would be constructed in conformity with the image depicted in the render?

Leaving aside the effect of disclaimers and certain contractual exclusion clauses, to which I shall refer below, if the answers to each of the first and second questions is yes, and the answer to the third question is no, in my view the Ripanis are entitled to an order in the nature of rescission of the contract of sale pursuant to ss 237 and 243(a) of the ACL, or, alternatively, to an order in equity that the contract of sale be rescinded.

16 On the first question, his Honour rejected Century’s defence that the render did not convey any meaningful representation and found that it in substance conveyed the principal representation alleged by the respondents. He further found that there was no reasonable basis for making the representations, given that Century knew it was impossible to construct apartment 1401 in a way that would resemble the render: PJ [12]. To that extent, although unnecessary to establish the statutory claim, his Honour found that Century deliberately engaged in misleading conduct.

17 Although his Honour accepted that the render did not contain any notation specifying the width or height of the opening between the living areas and the terrace, he found that “does not mean the render was inapt at, and much less incapable of, conveying the representations about which the Ripanis complain”, nor was it “by no means meaningless or incapable of being reasonably relied upon by prospective purchasers because it did not specify any dimensions of the free span opening”: PJ [30].

18 His Honour also found that a representation was made to the respondents by Mr Tran who told them, “in effect, that apartment 14.01 would be constructed as depicted in the render, with an expansive opening onto the terrace from the internal living areas” which he referred to as an “artist’s impression” but did not otherwise qualify that the impression conveyed was misleading and deceptive: PJ [32]. Mr Tran’s statements therefore “effectively reiterated, or corroborated, the representations conveyed by the render”: PJ [37].

19 The primary judge emphasised the “circumstances” in which the render was shown to the respondents at PJ [39]:

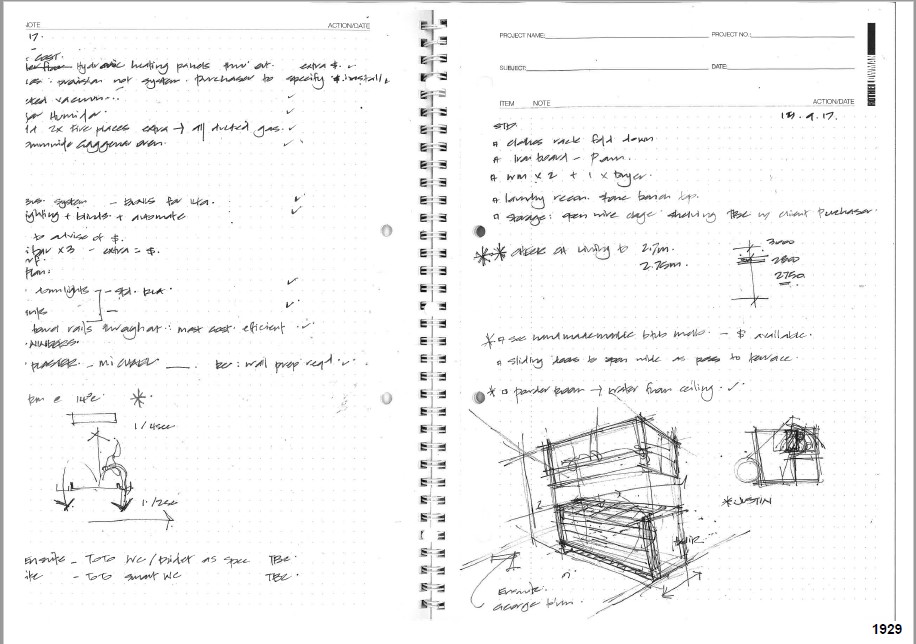

But the Ripanis did not see the render on a billboard and it was apartment 14.01 in particular which caught their attention, precisely because they were attracted to the seamless transition between the internal living areas and the outside terrace. The Ripanis saw the ‘hero render’ featured prominently on the wall of the display suite at the Victoriana and were told, in effect, that it depicted what they could expect apartment 14.01 to be like in relation to the free span opening between the living areas and the terrace, though it was an ‘artist’s impression’. It is in this context that the render was shown to the Ripanis and a copy of the marketing materials given to them.

20 On the question of reliance, which is now central to this appeal, his Honour rejected evidence from Ms Kate Hart, who at the time was employed by Rothelowman as an interior designer and senior associate, that on one or more occasions between May and June 2017, she told the respondents that an opening as depicted in the render was not achievable and that the likely width would be between 3m and 4m.

21 His Honour rejected the specific defence that the contract contained disclaimer and exclusion clauses that, in the particular circumstances, operated to preclude a finding of reliance upon the misleading and deceptive conduct or to erase its effect. He also found that despite the contract being subject to satisfactory approval of a floor plan, which approval was forthcoming, and attachment of the approved floor plan to the contract, from which it was apparent that the opening depicted in the render would not be constructed, the respondents were entitled to and did continue to rely upon the representation conveyed by the render. These findings are important to the appeal grounds and for that reason, I extend my introductory analysis as follows.

22 The contract was signed by the respondents on 1 April 2017, and was subject to satisfaction of a number of special conditions including a handwritten condition numbered 43 which read:

Subject to satisfactory of floor plan within 21 days (sic)

(special condition 43)

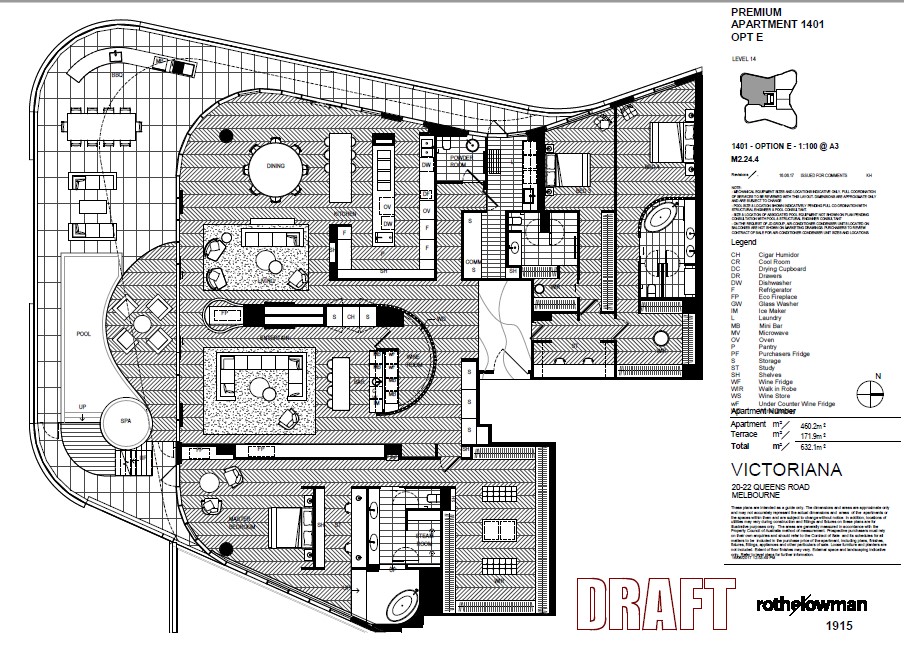

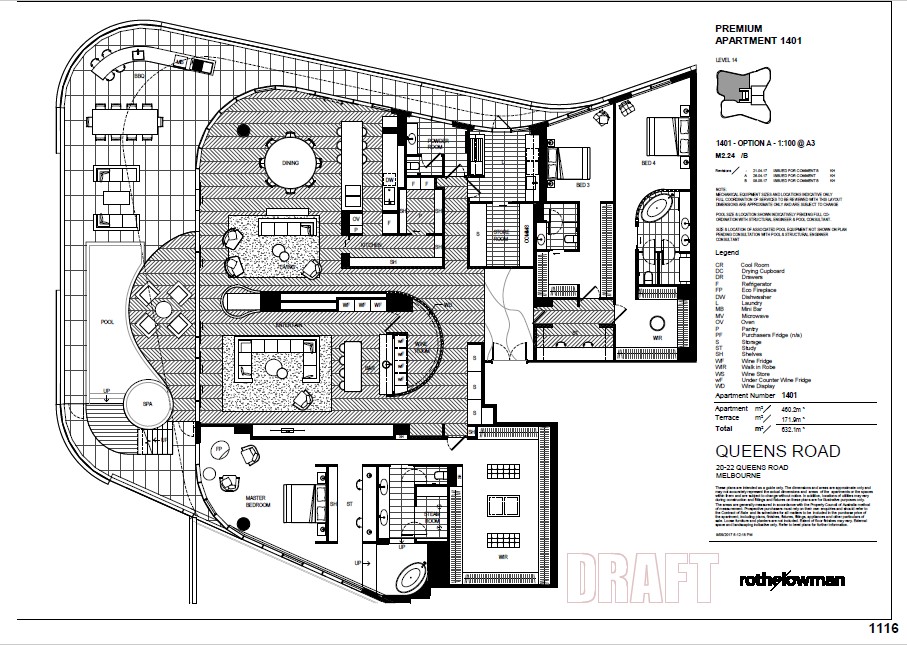

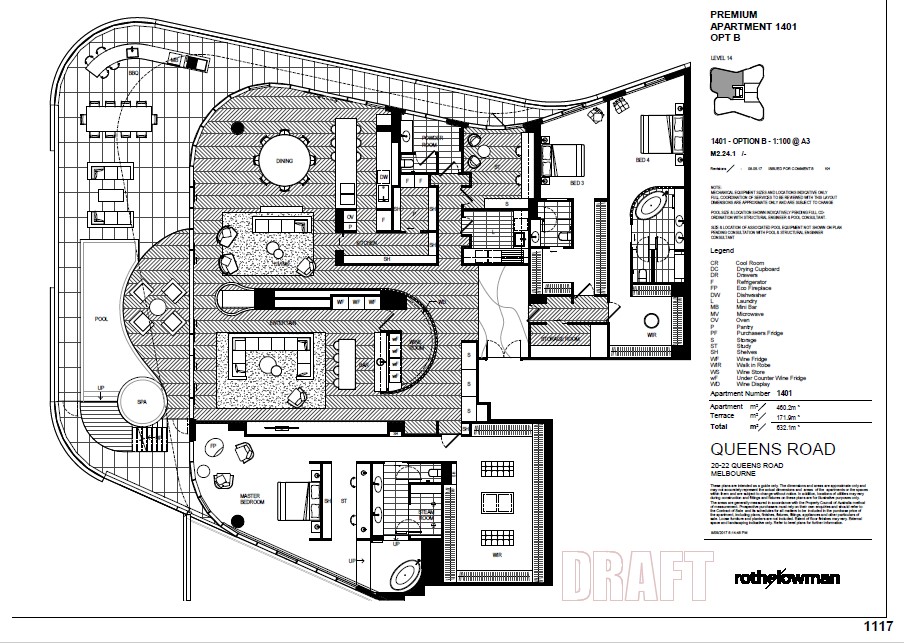

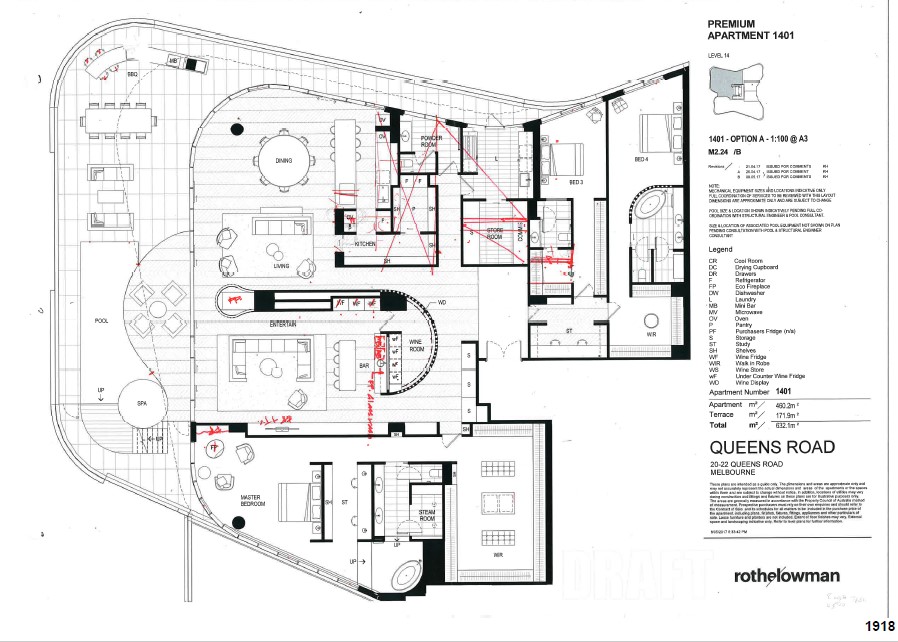

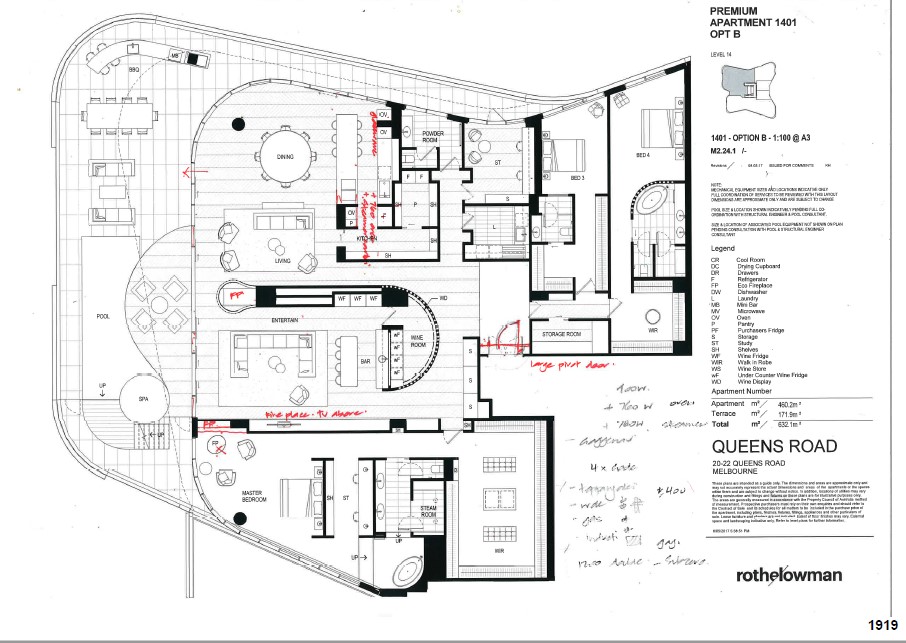

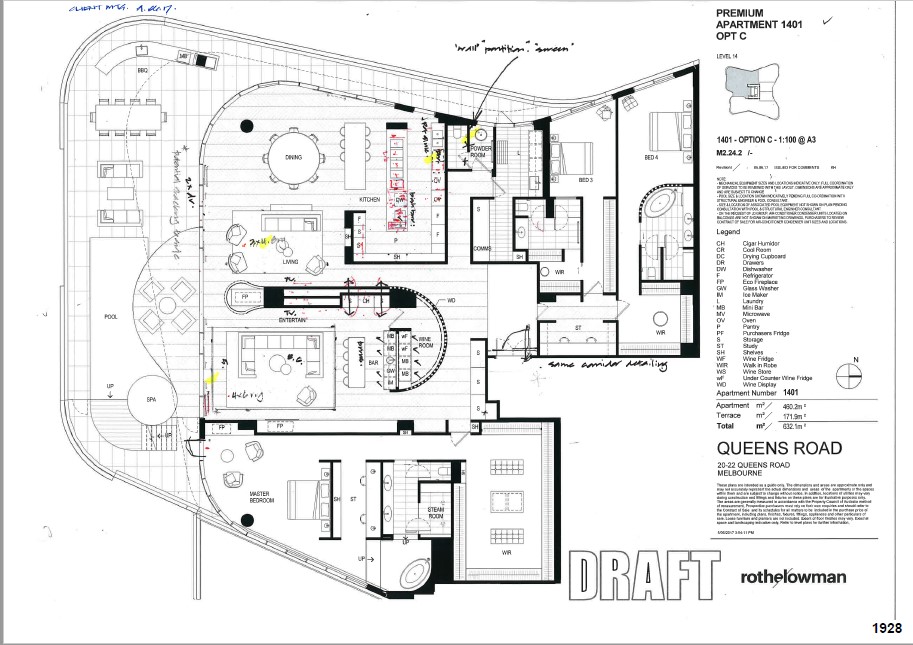

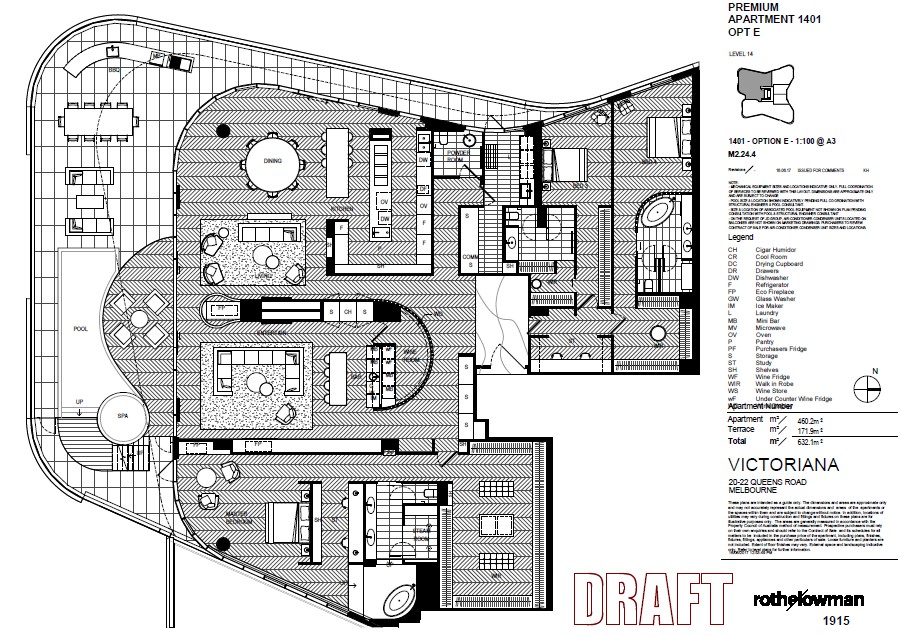

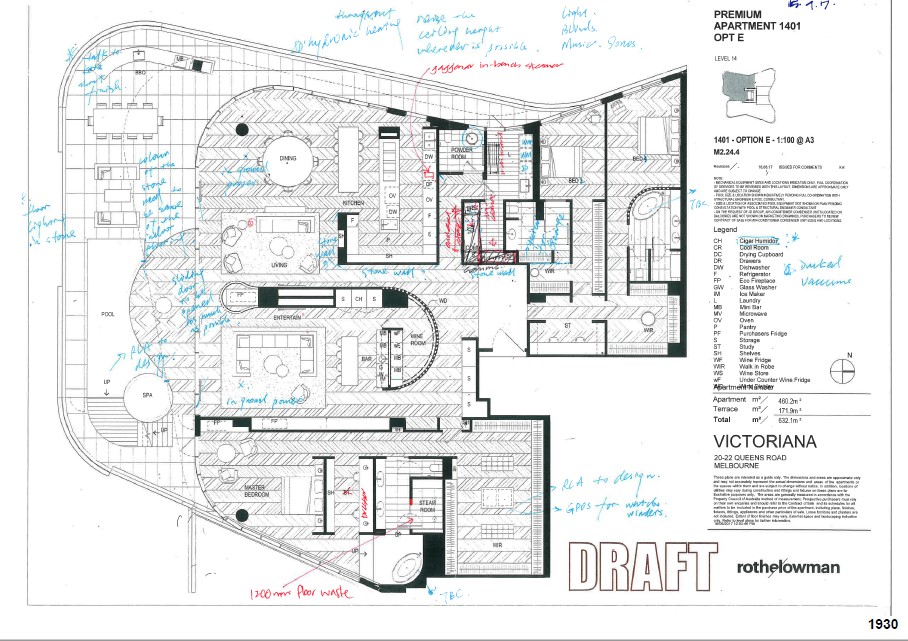

23 There was also attached to the contract a floor plan of apartment 1401 prepared by Rothelowman marked “draft” dated 16 June 2017 and with the title: “Premium Apartment 1401 OPT E” as follows:

24 Although somewhat difficult to read at the scale reproduced in this judgment (on the hearing of the appeal we were provided with A3 versions of all relevant plans), it is clear from a careful perusal of that plan that the glass doors proposed on the western side of the apartment to separate the internal and external living areas are not shown as providing for an unobstructed flow-through design. Rather, a stackable door system is provided with fixed vertical members, known as mullions, which are spaced at intervals between 1m at the narrowest point of opening and extending to approximately 3.6m at the widest point, opposite the fireplace.

25 The primary judge found that the contract did not become binding upon the parties until 29 August 2017, which is the date that the respondents provided a bank guarantee in lieu of the required deposit in the amount of $944,000, which guarantee Century accepted. Further, his Honour found that special condition 43 was not satisfied within the 21 day stipulated period. Rather, between 6 April and 9 June 2017, there were several meetings between the respondents and representatives of Century and Rothelowman. Various iterations of a floor plan with a proposed interior fit out were presented, discussed and developed before special condition 43 was met. The primary judge did not make a precise finding as to when the requested satisfaction was conveyed or by what mechanism: ultimately he inferred that when the respondents provided the bank guarantee, they must be taken to have approved of the Option E floor plan. However, it is to be noted that there was in evidence before the primary judge an email of 20 July 2017, from the respondents’ then solicitors to Mr Ripani which attached the email of 28 June 2017, and requested confirmation as to whether the respondents were satisfied with the Option E floor plan. There was no evidence of their response, if any. In any event, it was common ground at the trial that by providing the bank guarantee for the deposit, the respondents signified approval of the Option E floor plan.

26 Considerable time was spent at the trial on the issue whether the respondents, in consequence of that approval, must have then understood that the width of the flow-through design depicted in the render would not be constructed in accordance with the approved floor plan. Century sought to make out a case that the effect that any misleading representation conveyed by the render was expunged by the date that the contract became binding upon the parties or that the respondents did not rely upon the render in deciding to approve the floor plan and with it to proceed with the contract. The primary judge resolved this issue adversely to Century in that his Honour accepted the evidence of the respondents that their focus in approving the floor plan was upon the internal bespoke details of the apartment, that they did not understand the detail conveyed by the Option E plan and that they continued to believe in the truth of the representations conveyed by the render.

27 Century led evidence from Ms Hart as to several meetings and email exchanges with the respondents between April and June 2017. She gave evidence to the effect that she had informed the respondents that the width of the opening between the internal and external areas of the apartment, with the doors open as depicted in the render, could not be achieved. Specifically, she gave evidence that she told them that “we couldn’t have just one large expansive opening” and that the maximum width that was achievable was in the order of 3m to 4m. This evidence was the subject of significant challenge in cross-examination. As acknowledged by the primary judge: “If Ms Hart’s evidence were accepted, her statements to the Ripanis would have had the effect of curing the misleading representations conveyed by the render”: PJ [139]. The respondents disputed that they had been informed of these facts by Ms Hart. Ultimately, the primary judge preferred their evidence and rejected the evidence of Ms Hart as a reconstruction as well as unreliable: PJ [215].

28 Finally, the primary judge accepted the evidence of the respondents that if they had known the true position about the proposed flow-through design, they would not have entered into the contract. His Honour reasoned that this was, relevantly, detriment in that the respondents were induced to enter into the contract on the basis of a misleading render: PJ [227]. Further, the difference between the 3.4m opening as constructed and the opening depicted in the render was sufficiently material to found the exercise of the discretion to grant the following relief:

1. The contract of sale for the purchase by the Applicants of apartment 14.01 at 20-21 Queens Road, Melbourne, made on or about 29 August 2017, be rescinded.

2. By no later than 4:00pm on 25 March 2022, the Respondent return to the Applicants the bank guarantee provided on behalf of the Applicants by the Bank of Melbourne on 29 August 2017 in lieu of a deposit.

3. The Respondent pay damages and pre- judgment interest to the Applicants in an amount to be determined in accordance with paragraph 4 of these orders.

4. By no later than 4:00pm on 25 March 2022, the parties file:

a. an agreed minute of the sums payable for damages and pre-judgment interest in accordance with these reasons for judgment; or

b. failing agreement, the parties are to file separate minutes and submissions, limited to four pages, concerning their respective calculations of damages and pre-judgment interest payable in accordance with these reasons.

5. The Respondent pay the Applicants’ costs of and incidental to the proceeding, to be agreed and in default of agreement assessed on a standard basis.

29 Subsequently, orders three and four were resolved on 13 April 2022 when the primary judge ordered as follows:

1. Further to paragraph 3 of the orders of Justice Anastassiou dated 18 March 2021, the Respondent pay damages and pre-judgment interest to the Applicants in the agreed amount of $118,500.

2. The Applicants pay the Respondent’s costs of and incidental to the case management hearing on 6 April 2022.

30 A further issue agitated at the trial concerned a proposed height differentiation between the indoor and outdoor areas: a step down, not shown in the render. Eventually this issue evaporated when a representative of the builder, Mr De Mooy, gave evidence that a level surface had been constructed.

The appeal by century

31 As finally pressed, the grounds of appeal are:

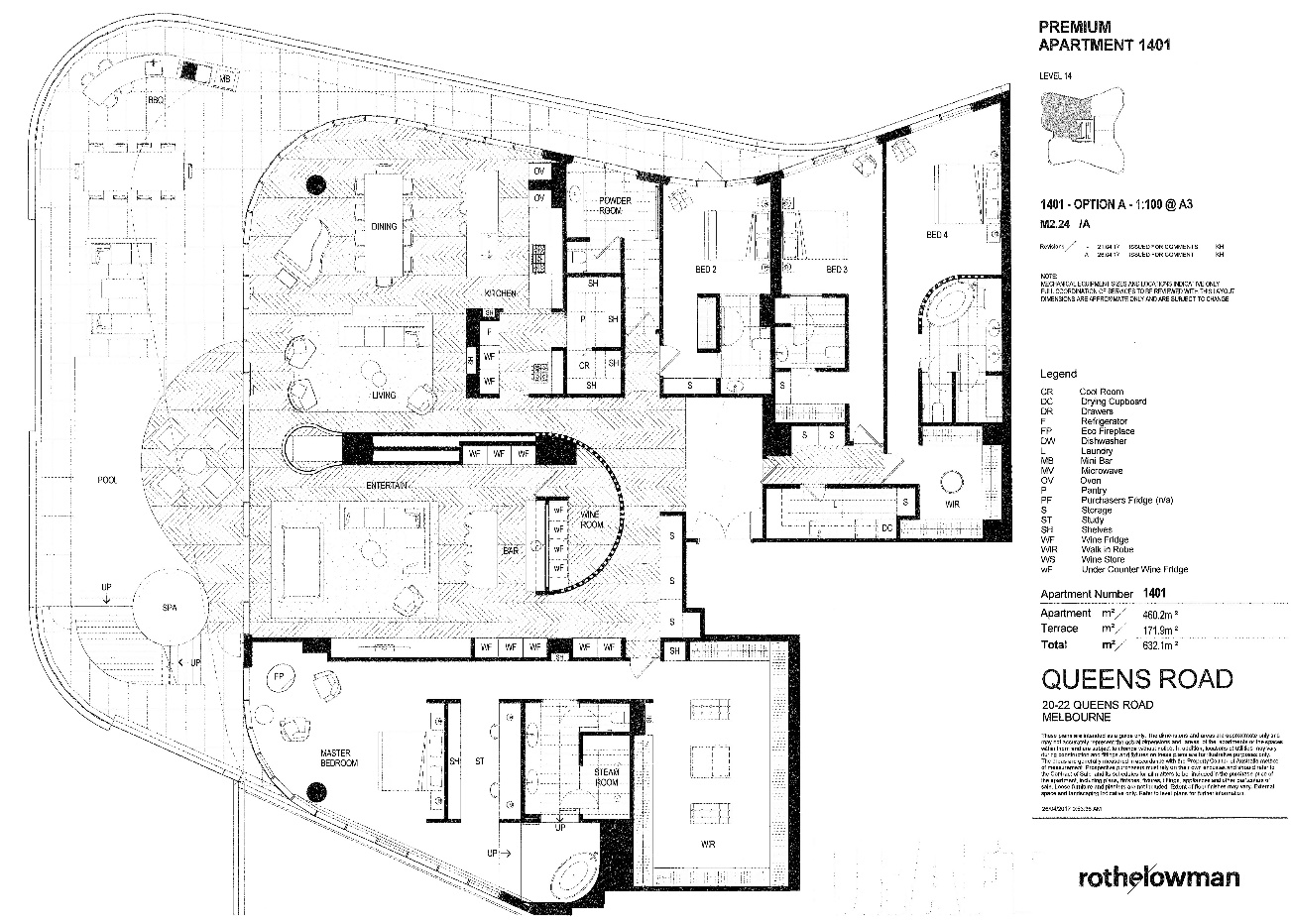

1. The primary judge erred in rejecting the evidence of Kate Hart to the effect that she informed the Respondents (Ripanis) in around June 2017, prior to the contract of sale with respect to Apartment 1401 (Contract) being entered into, that the opening for Apartment 14.01 could not be constructed in accordance with what was depicted in the render at Annexure I to the reasons for judgment, in circumstances where the corroborating documentary evidence, including in particular the annotated Option C floor plan at Annexure VI to the reasons for judgment, and the Option E floor plan at Annexure VII to the reasons for judgment that the Ripanis were satisfied with, made it glaringly improbable that Ms Hart’s evidence was a reconstruction (J [180] – J [221]).

2. The primary judge erred in finding that the exclusion clauses in the Contract were ineffective in negating any misleading or deceptive conduct or misrepresentation on the basis that the exclusion clauses were not sufficiently specific or explicit vis-à-vis the depiction of Apartment 1401 or, alternatively, on the basis that the exclusion clauses were “boilerplate” provisions (J [89]-[90]).

3. The primary judge erred in concluding that the Ripanis were entitled to statutory rescission pursuant to s 243(a) of the Australian Consumer Law in circumstances where:

(a) it was not open on the evidence for the primary judge to be satisfied that the Ripanis had suffered economic loss with respect to Apartment 1401 (J [233]);

(b) it was not open on the evidence for the primary judge to be satisfied that the Ripanis had suffered any other manifestation of other loss (J [226] – J [227]);

(c) the primary judge failed to subject the expert valuation evidence of Mr Anthony Rohan to critical evaluation (J [234]); and

(d) the primary judge erred by inferring that the value of Apartment 1401 was less than the Ripanis paid for it merely because Century Legend did not lead any contrary valuation evidence (J [235]) which was a wrong application of the rule in Jones v Dunkel which cannot be used to fill evidentiary gaps or convert conjecture into inference.

(e) alternatively, the primary judge erred in the exercise of discretion to grant statutory rescission pursuant to ss 237 and 243(a) of the Australian Consumer Law because it was not practically just in the circumstances to order rescission and the remedy was disproportionate to any loss or detriment.

4. The primary judge erred the exercise of discretion by concluding that the Ripanis were entitled to equitable rescission because it was not practically just in the circumstances to order rescission and the remedy was disproportionate to any loss or detriment.

Leave to adduce further evidence and ground five

32 At the hearing before us, the appellant sought leave to file an alternative version of the proposed amended notice of appeal which contained a proposed ground five as follows:

5. The primary judge erred by finding that the marketing render was misrepresentative when any difference between the artist’s impression and what was built was immaterial: J [32], J [98].

33 This ground may be shortly addressed. As explained in submissions, properly understood it turns upon the separate application that was made to adduce new evidence on the appeal by reference to the appellant’s interlocutory application of 11 July 2022 and the affidavit of Timothy Burgess affirmed that day.

34 Mr Burgess is a professional photographer. He was provided with a copy of the render and was engaged to attend the completed development for the purpose of taking photographs which, in his words, “attempt to best replicate that image using traditional photography, and further photographs that give some context to my efforts”. He took several photographs on 11 July 2022 (which he erroneously records as 11 June 2022 at paragraph [7] of his affidavit), explaining his methodology:

The photographs attached to this affidavit were taken between 1.30 to 2:50 pm on 11 June 2022, which was a bright sunny day with a low winter sun. It was very difficult to take photographs of rooms with windows in these conditions. The contrast is at its most extreme with significant glare. As a result, I could not match the light outside with the inside of the room and recreate the light conditions which are balanced in the render. I have therefore somewhat adjusted the light settings as between the outside and inside to obtain a more consistent lighting effect. This was to ensure that there is consistency of lighting across the whole of the image, and consistency between my images.

35 The attached images commence with the render followed by eight photographs which variously depict images of the completed apartment 1401 viewed internally and externally and with the doors on the western side fully open. Some of those images appear to be taken at a location reasonably approximate to that which is depicted in the render, although there are significant differences; in particular, due to the bespoke form of the internal fit out and a rearrangement of the form of the swimming pool.

36 Leave to adduce this evidence was opposed by senior counsel for the respondents. In argument before us, senior counsel for the appellant accepted that at least by 2 December 2020 (notably before commencement of the trial before the primary judge) the development was sufficiently progressed such that photographic evidence could then have been obtained to depict the actual form of the proposed door configuration on the western side and that it would have been open to the appellant to engage an expert to prepare a montage of the apartment as constructed and one with the door configuration as depicted in the render by way of direct comparison. Senior counsel accepted that “theoretically, that could have been done”. It is also a matter of common experience, which senior counsel was unable to comment upon, that in development proposals montages are frequently prepared, with a degree of accuracy, in order to give a realistic impression of that which is proposed to be constructed. Accordingly, senior counsel accepted that steps could have been taken by the appellant to engage an appropriately qualified expert to produce evidence of this type for use at the trial.

37 For the respondents, it was submitted that leave should be refused as the case at trial was not run on the basis that the central representation conveyed by the render was true and the evidence was capable of being produced during the course of the trial (or at any time prior to the delivery of judgment upon an application to reopen).

38 The exchange that I have summarised explains why we refused leave to adduce the putative new evidence upon the hearing of the appeal, with the consequence that ground five fell away. Section 27 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) confers a discretion to receive further evidence upon an appeal and is not couched in the language of fresh evidence. However, ordinarily in order to obtain a favourable exercise of the discretion it must be demonstrated that the applicant was unaware of the evidence at the time of the trial and could not with reasonable diligence have obtained it and, further, that had the evidence been adduced at the trial it is unlikely that other evidence would have been adduced by the opposing party in order to meet it. It should also be reasonably clear that the evidence, if received, would likely affect the result. For these propositions see generally: Moore v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship (2007) 161 FCR 236; [2007] FCAFC 134 at [5]-[7], Gyles, Graham and Tracey JJ. I accept that these are not immutable tests that guide the exercise of the discretion in every case, but what is clear is that they are important considerations in this case.

39 The new evidence sought to be adduced could, with reasonable diligence, have been obtained by engaging an appropriately qualified expert to prepare accurate montages for the purposes of the trial. No satisfactory explanation for the failure by the appellant to do so was offered. The fact that the development was still in the construction stage at the time of the trial does not answer why, with reference to the then form of the architectural drawings approved for construction, comparative montages could not have been prepared. Further, the evidence sought to be introduced from Mr Burgess is, on its face, contestable: he does not provide an analysis which locates the point at which each photograph was taken, nor as to the camera lens angle employed. Inevitably, had we resolved to receive this evidence, it would then have been necessary to adjourn the hearing of the appeal (perhaps for a lengthy period) in order to afford to the respondents a fair opportunity of examining the evidence and, if thought fit, to engage their own expert with the consequence that this Court most likely would have been required to resolve a disputed question of fact which ought to have been (and with reasonable diligence should have been) resolved by the primary judge. Finally, the appellant did not address the consistency of its application with the overarching purpose of civil practice and procedure as provided for at ss 37M and 37N of the FCA Act.

40 It is for these reasons that we refused the application to adduce further evidence and leave to rely on ground five.

41 I address the remaining appeal grounds seriatim.

Ground one: rejection of the evidence of Ms Hart

42 This ground invites this Court to overturn the rejection by the primary judge of the evidence of Ms Hart, which was in part based on his assessment of her demeanour and his acceptance of the evidence of the respondents as credible. At PJ [215]-[216] his Honour summarised his assessment and findings as follows:

In relation to Ms Hart’s demeanour as a witness, I found her to be vague and evasive in relation to the critical questions concerning the circumstances in which she claims to have orally informed the Ripanis of the inaccuracy of the render. That is not a criticism of Ms Hart in relation to her understandable uncertainty of recollection about particular meetings or discussions relative to others. Rather, it is her uncertainty about the impetus for the critical changes to the floor plans, which I have described at length, that is more significant in reaching the conclusion that Ms Hart’s evidence was reconstructed and unreliable, notwithstanding her ostensible positon as a disinterested witness.

The Ripanis, on the other hand, gave evidence that revealed a straightforward and plausible course of events. They were attracted to apartment 14.01 because of the appeal of the free span opening. They were told by Mr Tran that the render depicted apartment 14.01 and they had no reason to doubt that statement. They did not believe, or contend in this proceeding, that they expected the apartment to look identical to the render. They understood that there was a degree of interpretation in the render. But equally, they took from the render what it conveyed; specifically, a free span opening effectively the width of the internal living areas.

43 At issue is the evidence of Ms Hart that in June 2017, and perhaps earlier in May 2017, before the contract became unconditional by reason of the approval by the respondents of the Option E floor plan, she explained to the respondents that the doors on the western side of the apartment could not be constructed with an opening as wide as depicted in the render. The precise evidence that she gave, and the circumstances which led to it being adduced, were examined by the primary judge and summarised as follows in his reasons:

160 Century Legend submitted that Ms Hart’s was (sic) evidence was, in effect, that during subsequent meetings in May and June 2017, she explained to the Ripanis the position of the doors on the western façade and told the Ripanis there would not be a single opening onto the terrace. In particular, Century Legend submitted that the Court should accept the following aspects of Ms Hart’s evidence:

(1) that during meetings with the Ripanis prior to them entering into the contract of sale, Ms Hart pointed to, and annotated, various floor plan to show the Ripanis where the openings would be between the internal living area and external terrace;

(2) that in a meeting with the Ripanis on a date she could not recall in May 2017, she specifically told the Ripanis that it was not possible to have a single large opening along the western façade because of the wind loading;

(3) that in that same meeting in May 2017, she also said there had to be a series of smaller openings, but there would be a large opening centred on the fireplace allowing for access to the external terrace; and

(4) that in a meeting on 9 June 2017, she discussed the size of the openings between the interior and exterior with the Ripanis and mentioned, by reference to the glazing mullions, that the opening would be approximately 3 to 4 metres.

Ms Hart says these matters are reflected in annotated versions of the Option B floor plan (see Annexure V) and Option C floor plan (see Annexure VI).

161 In substance, Ms Hart’s evidence was that she explained to the Ripanis that it was “impossible” to have any wider opening than had been indicated by the floor plans and that the Ripanis were “disappointed” upon being informed of this.

…

172 As I have said above, Century Legend’s defence, as pleaded and opened, proceeded on the tacit assumption that there was no discussion of the opening in pre-contractual meetings such that it would have disabused the Ripanis of any misapprehension created by the render. It was not opened that Ms Hart told the Ripanis that what was depicted by the render could not be constructed. Rather, until Century Legend’s defence developed and altered as a result of Ms Hart’s evidence, not previously mentioned, the gravamen of Century Legend’s defence was that it was discernible from the various iterations of the floor plans, discussed at meetings between the Ripanis and Ms Hart, that the free span opening depicted in the render would not be built. This original defence as to causation is still pressed, notwithstanding that if Ms Hart’s evidence were accepted there would hardly be any need to decide whether scrutiny of the floor plans disabused the Ripanis of any misapprehension about what the render represents.

…

174 Ms Hart’s evidence is relevant to Century Legend’s original defence but only tangentially. The discussions between Ms Hart and the Ripanis about the floor plan and fit out were relevant as occasions when it may be expected the Ripanis considered the floor plans, including the depiction of the internal living areas and the terrace. Thus, as opened, Ms Hart was to give, in effect, only contextual evidence relevant to the question of reliance by the Ripanis. However, as I have said, on the second day of Mrs Ripanis cross-examination, it was suggested to her, for the first time, that Ms Hart had explained by reference to two iterations of the floor plan (Option B and Option C, see Annexure V and Annexure VI, respectively) that the free span opening depicted in the render could not be constructed. Century Legend submits that Ms Hart thereby corrected any misunderstanding the Ripanis may have had concerning the expanse of the free span opening.

44 His Honour then proceeded to undertake an analysis of the evidence of Ms Hart, the contemporaneous circumstances and a number of objective criteria which led to the rejection of her evidence at PJ [180]-[221]. He did not find her to be a dishonest witness. His Honour did not simply make a finding that the evidence of Ms Hart was reconstructed and unreliable by reference to her demeanour. Rather, what is clear from the structure and the analysis at PJ [180]-[214], when read with the specific demeanour finding at PJ [215], is that the ultimate rejection of her evidence at PJ [221] is founded on three sequential steps. The first is inconsistency with identified objective circumstances. The second, the reconstruction, evasive and unreliability finding at PJ [215] which expressly turns on her uncertain evidence about the impetus for “the critical” alterations to the floor plans in iterations marked as Options A and B. And third, acceptance of the contrary evidence of the respondents.

45 The reconstruction and unreliability findings are not exclusively or substantially anchored by the demeanour exhibited by Ms Hart when giving evidence and in this regard I bear in mind the “important distinction between the credit and the demeanour of a witness. A court can determine that a witness lacks credit but may do so on a basis that wholly excludes the witness’ demeanour”: Prouten v Chapman [2021] NSWCA 207(Prouten) at [10], Meagher and Leeming JJA.

46 Thus, it is important to understand in this case that if the primary judge erred in his fact-finding in a way which affected his demeanour conclusion, or the reconstruction and unreliability findings were not materially informed by his Honour’s assessment of the demeanour of Ms Hart, then the duty of this Court in the conduct of the review function pursuant to s 24 of the FCA Act is to make its own findings of fact and to reason accordingly. Although Brereton JA dissented in the result in Prouten, in part I regard his Honour’s synthesis of the issue in that case at [107]-[108] as apposite to the present:

It does not appear to me that his Honour’s findings of credit, at least so far as they concerned the appellant, were significantly informed by demeanour – or, in the words of Lee, by impressions about the credibility and reliability of witnesses formed by the trial judge as a result of seeing and hearing them give their evidence. Rather, they were based on perceived inconsistencies between her evidence and her prior statements. The judgment was not expressly based on demeanour, and while the judge had the advantage of seeing and hearing the witnesses, he did not expressly refer to any observations derived from it. His conclusion adverse to the plaintiff’s credibility was based on the perceived inconsistency of her account with two contemporaneous documents; it was founded on the content of her evidence, rather than on the manner in which it was given.

In those circumstances, the strictures in cases such as Masson do not apply, and this Court is in as good a position as his Honour to draw the relevant conclusions. In that context, the question is not whether his Honour’s conclusions were glaringly improbable or contrary to incontrovertible evidence, but whether they were incorrect. For the reasons just given, I am satisfied that, notwithstanding that there had to be reservations about the reliability of the appellant, the weight of the contemporaneous evidence was such that it ought to have been concluded, on balance of probabilities, that the accident occurred in the manner described by her.

47 The reference to “Lee”, is Lee v Lee (2019) 266 CLR 129 [2019] HCA 28 at [55], Bell, Gageler, Nettle and Edelman JJ. And the reference to “Masson”, is Queensland v Masson (2020) 94 ALJR 785; [2020] HCA 28 at [119] per Nettle and Gordon JJ the full text of which is:

A good deal has been said by this Court about the propriety of an appellate court setting aside a trial judge's finding of fact based on the credibility of a witness For present purposes, it is enough to repeat the observations of Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ in Fox v Percy that, at least where the trial judge's decision might be affected by his or her impression about the credibility of the witness, whom the trial judge sees and hears but the appellate court does not, the appellate court must respect the attendant advantages of the trial judge. If, making proper allowance for such advantages, the appellate court concludes that an error has been shown, it is authorised and obliged to discharge its appellate duties in accordance with the statute conferring appellate jurisdiction. In particular cases, it may be demonstrated that the trial judge's conclusions are erroneous, despite being based upon or said to be based upon an assessment of credibility. That will be so where the trial judge's findings of fact are contrary to “incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony”, “glaringly improbable”, or “contrary to compelling inferences”. But where, as here, that is not so, it is no justification for appellate intervention that the appellate court might consider that the trial judge did not give sufficient weight to matters that the appellate court considers assist the plaintiff's case. In this matter, it was not open to the Court of Appeal to reject the primary judge's analysis of Mr Peters' oral evidence.

(Footnotes omitted.)

48 As I have explained, the primary judge did not simply reject the evidence of Ms Hart based on his assessment of her demeanour. Accordingly, whilst his Honour enjoyed the advantage of hearing all of the evidence sequentially and of observing how each witness presented in the witness box, including nuances in expression not recorded in the transcript, ground one is not simply answered, as submitted by senior counsel for the respondents, by the general proposition that we must “be persuaded that his Honour has palpably misused the advantage that he obtained in seeing the witness give evidence and be cross-examined”. That said, however, I accept that we must give due consideration to that advantage and exercise caution when considering the extent to which the reconstruction and unreliability finding does turn on his Honour’s assessment of demeanour.

49 I turn next to the analysis undertaken by the primary judge, adopting the order that I have set out.

The objective circumstances considered by the primary judge

Knowledge

50 The first, and “arguably most significant” is the finding at PJ [181] that Ms Hart knew throughout 2017 that the render was misleading in appearance when she dealt with the respondents. She unambiguously said so in an email to Century dated 23 June 2017:

We feel that it is extremely important that JD Group make Purchasers aware of the actual internal/external transition and break-up in glazing that will be achieved, as this is not accurately shown in the JD Group commissioned marketing renders. It needs to be reiterated that the marketing renders are ‘artist’s impression’ only and not actual building images.

51 The primary judge was then critical of Ms Hart for the fact that she did not state in that email that she had informed the respondents of that fact at a meeting on 9 June 2017. He reasoned why at PJ [184]:

…She does not say that she has informed the Ripanis of the inaccuracy of the render. Though it is not necessarily the case, I consider that had Ms Hart informed the Ripanis as she claims to have, it is likely she would have said so in her email to Century Legend. And this is where the controversy concerning the render, and Ms Hart believing that Carr Design effectively resigned because of it, again becomes relevant. Given the background I have described above, it is likely on the balance of probabilities that if Ms Hart had said what she claims to have said, she would have recorded having done so in her email to Century Legend. Yet, on the contrary, she informs Century Legend’s representatives that it is their responsibility to disabuse purchasers of the incorrect impression created by a render it commissioned.

52 At PJ [185]-[187] his Honour referenced other occasions in 2017, 2018 and 2019 when Ms Hart did not record in writing the advice that she said was given to the respondents in June 2017. It is not contested in this appeal that Ms Hart knew that the render was inaccurate, indeed misleading, from at least early 2017 and that at no point did she state that fact in writing to the respondents.

Contemporaneous notes

53 The second objective circumstance that his Honour relied upon is the absence of any express reference in any contemporaneous document to the advice that Ms Hart said that she conveyed to the respondents. At PJ [188] he reasoned in part that:

…Given the context I have described, I would expect that as a matter of common professional practice, if not self-protection, that had Ms Hart said what she claims to have said, she would have been astute to have made some contemporaneous record of what she had said; and thereafter, whenever the context made it appropriate, that she would have reminded Century Legend, and the Ripanis if need be, of what she had said about the render in meetings during May and June 2017. That is all the more so given Ms Hart’s evidence that she appreciated the render was a “potential timebomb” and that in due course she might find herself sitting in a witness box giving evidence about her communications with the purchasers of apartments. But Ms Hart did not make any contemporaneous note which recorded, in terms, or even alluded to, what she says she told the Ripanis. I have referred above to her correspondence that does not assert that she had already told the Ripanis apartment 14.01 could not be constructed in accordance with the render.

54 To this the primary judge added at PJ [189] the evidence of Ms Hart (which he considered incorrect) that she discussed the Option B floor plan with the respondents on 26 May 2017, which is after it had been rejected by them on 10 May 2017 and at PJ [190] her failure to produce a sketch in her file note made on 15 September 2017 in order to explain to the respondents in three-dimensional form the opening to the terrace that could be constructed. At PJ [192]-[194], the primary judge rejected a submission that he should accept Ms Hart as a witness of the truth by reason of the fact that she was a disinterested party. That fact did not attract significant weight in his Honour’s reasoning in that he remained critical of, and placed more weight upon, her failure to make contemporaneous notes of advice given to the respondents, which in his view was contrary to standard professional practice or common sense. Although his Honour noted the absence of cross-examination of any apparent motive of Ms Hart, nonetheless he concluded at PJ [194] that there is “a relevant and plausible motivation which emerges” from her evidence being intrusion upon the commercial relationship between the appellant and the respondents which he characterised as:

…As Ms Hart said in her email of 23 June 2017, it was Century Legend’s responsibility to inform purchasers, here the Ripanis, that the render did not accurately reflect what was to be constructed. For Ms Hart to have then taken it upon herself to disabuse the Ripanis of the impression created by the render would, on her own assessment of who was responsible for correcting the impression, have been to intrude on the commercial relationship between her client, Century Legend, and its purchasers, the Ripanis. Ms Hart’s email dated 23 June 2017 suggests to the contrary that she was respectful of the commercial relationship between Century Legend and the Ripanis, though she did urge that Century Legend correct the impression created by the render. It therefore seems unlikely to me that Ms Hart would say something to the Ripanis which objectively carried the risk that it may have caused the Ripanis to not proceed with the purchase. This inference is fortified by the fact that Mr Perkins also told Century Legend that it should be transparent with potential purchasers.

A change in Ms Hart’s evidence

55 The third factor referenced by his Honour at PJ [195]-[214] focused upon the late and “highly material change” in the evidence that Ms Hart was to give, though, and with respect to his Honour, his reasoning strays beyond that factor. In short, procedural directions were made for the filing and service of witness outlines prior to the commencement of the trial. There were two relevant outlines from Ms Hart: one dated 23 October 2020 and the other 20 November 2020. Those outlines did not foreshadow evidence by Ms Hart to the effect that she explained to the respondents in May and June 2017 that the terrace door opening as depicted in the render could not be achieved and that the maximum opening would be in the order of 3m to 4m. The defence relied upon by the appellant made no mention of these facts. Senior counsel for the appellant did not open the case on that basis. The point did not first emerge until part way through the cross-examination of Mrs Ripani on 8 February 2021, but even then it was not directly put to either of the respondents that Ms Hart told them that the maximum achievable opening was limited to between 3m and 4m.

56 By way of explanation, Ms Hart said in evidence that due to the various lockdowns imposed in Melbourne in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, she had not been able to access hard copy documents at her office and that her first available opportunity to do so was in January 2021, when she managed to locate an original file for the development of apartment 1401 which contained within it original versions of the various floor plans with her handwritten annotations. The discovery of those documents assisted her memory as to what was discussed with the respondents at meetings in May and June 2017.

57 Despite that evidence, the primary judge found it unreliable for several reasons. One, that Ms Hart amended the Option B floor plan in May 2017 without discussing the changes with the respondents and that she was mistaken in her evidence that this version of the floor plan was discussed at a meeting on 3 May 2017 (because it was not created until 8 May 2017) and was also mistaken in her evidence that it was discussed at a meeting on 26 May 2017 (because by 10 May 2017 it was redundant). Another, is that Ms Hart was also mistaken in her evidence as to the provenance of the Option A floor plan which she emailed to Mr Hu on 26 April 2017. In evidence, she said that the alterations depicted on that version were made on the instruction of the respondents. On closer questioning, she accepted that her evidence as to that was speculative and that she could not actually recall whether those changes were discussed with the respondents. Her evidence as to that was also inconsistent with the fact that she accepted that the only meeting prior to the preparation of that plan was one that occurred on 7 April 2017, at which she further accepted there was no discussion about the location or width of the opening to the terrace.

58 His Honour applied similar logic to the Option C floor plan that he accepted was produced and discussed at the meeting between Ms Hart and the respondents on 9 June 2017. At PJ [211]-[212] he reasoned:

Returning to the annotated Option C floor plan, and to the markings Ms Hart says she made on that plan during a meeting on 9 June 2017, I observe that Ms Hart had previously effected changes to the door positioning and the opening size without consulting with the Ripanis. As I have said, Ms Hart concedes that she amended the Option a floor plan at her own initiative on 26 April 2017, recalling there was no discussion of the opening at the meeting on 7 April 2017. It seems to me that Ms Hart must have done this before there was any occasion to discuss such changes with the Ripanis.

This reveals that, at least on one occasion, it was Ms Hart who initiated the changes to the floor plans in relation to the opening onto the terrace. The changes she made, had they been drawn to the attention of the Ripanis, would have revealed that the opening as marked on Option A and later iterations, including Option C, are at least potentially consistent with what might be constructed. Option C allows for a larger opening centred on the fireplace, rather than having what is depicted more faintly on the Rothelowman concept drawing; namely, two smaller door openings to the south-west and north-west. That, of course, would be entirely inconsistent with the representations conveyed by the render.

59 Finally, his Honour regarded as significant in his assessment of the objective circumstances that which he described as the consistent conduct of Ms Hart which he summarised at PJ [214]:

I note, however, that other than the explanation given by Ms Hart to the effect that she had disabused the Ripanis of the impression created by the render, Ms Hart’s conduct is entirely consistent. She told Century Legend that it was its responsibility to alert purchasers to the inaccuracy of the render which it had commissioned. She made no contemporaneous note of her advice to the Ripanis. She did not say, at any time during the post-contractual period, that she had previously disabused the Ripanis of the misapprehension caused by the render either in meetings or in correspondence. The evidence was instead raised for the first time in the course of Mrs Ripanis’ cross-examination.

Uncertain and unreliable evidence

60 Informed by this analysis, his Honour next proceeded to make the adverse demeanour finding at PJ [215]. He did not criticise Ms Hart’s “understandable uncertainty of recollection about particular meetings or discussions relative to others” which is important in that the credit finding does not turn on her evidence as to whether the terrace door width was discussed in a meeting in May 2017 as well as in the critical meeting of 9 June 2017, about which senior counsel for the respondents made much in cross-examination and subsequent submissions. Thus, this “understandable uncertainty” does not found the finding that her evidence “was reconstructed and unreliable”. What is decisive in the reasoning is Ms Hart’s “uncertainty about the impetus for the critical changes to the floor plans”.

61 What did his Honour mean by that? At PJ [189], [198] and [199] findings are made about the Option B floor plans dated 8 May 2017 as annotated by Ms Hart. Self-evidently, that plan was not discussed at the meeting of 3 May 2017 and could not have been annotated in the presence of the respondents to reflect a discussion with them. As to the subsequent meeting held on 26 May 2017, his Honour found it “theoretically possible” that it could have been discussed on that day, but unlikely in that Mr Ripani had emailed Ms Hart on 10 April 2017 expressing a preference for the Option A floor plan. From those findings the primary judge concluded that Ms Hart “made changes to the doorways and openings on the Option B floor plan in the absence of any discussion with the Ripanis about the matter”: PJ [198].

62 At PJ [204]-[208] his Honour made findings about the evolution of the Option A floor plan which was first issued on 21 April 2017. Ms Hart emailed that plan to Mr Hu and Mr Tran on 26 April 2017. It differed from the concept plan that Ms Hart had emailed to the respondents on 10 April 2017 in that the door arrangement on the western façade depicted a wider sliding opening opposite the fireplace than shown on the concept plan. In evidence in chief, Ms Hart first stated that those changes were directed by the respondents in language redolent of reconstruction: “it would have been in our discussion”, which was objected to. His Honour then reminded Ms Hart of the need to confine her evidence to her actual recollection to which her response was that she could not recall if a conversation about the openings occurred in the meeting of 7 April 2017 adding (T 506):

…The next plan that we sent out, which was Option A revision A, does show the openings as indicated, centred on the fireplace, south of that from the entertaining, and north of that within the dining area. I can’t recall whether we had informed the Ripanis or discussed with the Ripanis in the initial meeting, or whether those changes were made on our behalf as a – the development of the plan.

63 His Honour concluded that this evidence was “self-evidently speculative” and affected the reliability of Ms Hart’s “recollection of events and to the risk of reconstruction on her part”, which his Honour noted was one of a number of instances of apparent reconstruction by her: PJ [207]. His Honour further concluded at PJ [208] that properly understood Ms Hart contradicted herself in her evidence about the provenance of the Option A floor plan.

Acceptance of the evidence of the Respondents

64 The third and least complex step in his Honour’s reasoning is that he accepted the evidence of the respondents that they were not disabused of their understanding of the representation conveyed by the render until, at the earliest, October 2018. This finding turns on acceptance of almost all of their evidence commencing with why they were attracted to apartment 1401 in the first place; the expectation that they formed based on their understanding of the render; that they would not have entered into the contract but for the representation conveyed by the render and that they would not have paid the deposit, by procuring the bank guarantee and, by implication, would not have approved of the Option E floor plan had they known the true position. In his Honour’s summary as to why he preferred their evidence at PJ [216]-[221], he accepted the evidence of the respondents to the effect that they did not have discussions with Ms Hart as described in her evidence.

65 As I will explain, my analysis of this aspect of his Honour’s reasoning requires a detailed understanding of all of the relevant evidence that was given at the trial, which I address in dealing with the submissions relied upon by each party.

The submissions for and against ground one

66 The crux of the submission pressed by senior counsel for the appellant is that his Honour did not find Ms Hart to be a dishonest witness: only that her evidence was reconstructed (at PJ [215]) and that we should conclude upon our review of all of the evidence that this finding is glaringly improbable. Senior counsel developed a number of arguments to specifically address the central point of this ground, which conveniently may be grouped as follows.

67 First, that we should be careful in our deference to the advantage enjoyed by the primary judge by reason of the significant delay between the conclusion of the trial on 8 April 2021 and delivery of judgment on 18 March 2022. The primary judge did not acknowledge the delay or explain its cause. It is a matter of common experience that in a busy court there are many and varied reasons for delay in the delivery of judgments: they may be internal, such as the need to hear and decide more urgent cases or, as here, external in that most of the trial was conducted when Melbourne was subject to lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as a general proposition, the fact of long delay rather than the cause, may “weaken a trial judge’s advantage” with the consequence that “delay must be taken into account when reviewing findings made by a trial judge after a significant delay from the time when the relevant evidence was given”: Expectation Pty Ltd v PRD Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 140 FCR 17; [2004] FCAFC 149 at [70], Carr, Emmett and Gyles JJ. Beyond the framing of that submission, counsel did not interrogate how the delay in this case must be taken to have infected the credibility assessment of the primary judge, nor did counsel address the subsequent passages from that case at [71]-[73]:

In the normal course, statements made by a trial judge of a general assertive character can be accepted as encompassing a detailed consideration of the evidence. However, where there is significant delay, such statements should be treated with some reserve. After a significant delay, a more comprehensive statement of the relevant evidence than would normally be required should be provided by the trial judge in order to make manifest, to the parties and the public, that the delay has not affected the decision.

In cases not affected by delay, an appellate court is entitled to assume that the mere failure to refer to evidence does not mean that it has been overlooked or that other forms of error have occurred. However, where there is significant delay, no favourable assumptions can be made. In such circumstances, it is up to the trial judge to put beyond question any suggestion that he or she has lost an understanding of the issues. Where there is significant delay, it is incumbent upon a trial judge to inform the parties of the reasons why the evidence of a particular witness has been rejected. It is necessary for the trial judge to say why he or she prefers the evidence of one witness over the evidence of other witnesses (Hadid v Redpath (2001) 35 MVR 152 at [34] and [53]).

Of course, where the trial judge, notwithstanding significant delay, demonstrates by his or her reasons that full consideration has been given to all of the evidence, the parties and the public may be satisfied that the delay has not affected the decision. More specifically, if the reasons demonstrate that the delay has not weakened the trial judge’s advantage, confidence will be maintained in the decision. For example, it would be open to a trial judge to explain in the course of giving reasons that contemporaneous notes were made of impressions formed as evidence was given by witnesses of importance (see R v Maxwell (unreported, New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal, Spigelman CJ, Sperling and Hidden JJ, 23 December 1998)).

68 Here, although the primary judge formulated detailed reasons for his rejection of the evidence of Ms Hart, the delay in the publication of reasons, in my view, necessitates a comprehensive review of all of the evidence relevant to the his Honour’s assessment of her demeanour.

69 The second submission as developed is that Ms Hart gave clear, credible and compelling evidence that she explained to the respondents on 9 June 2017, by reference to the annotated and dated version of the Option C floor plan, the proposed location of the doors on the western façade that there would be three individual openings and that it was wrong for the primary judge to focus on the provenance and development of Options A and B, which distracted his Honour from focusing on the most important evidence of Ms Hart.

70 Pausing there, the argument is not that the rejection of the evidence of Ms Hart by the primary judge was erroneous as contrary to incontrovertible facts or uncontested testimony as understood by reference to the joint reasons of Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ in Fox v Percy (2003) 214 CLR 118; [2003] HCA 22 (Fox) at [28]. Although the appellant’s written case in a single sentence is framed as attacking the reconstruction conclusion at PJ [215] on the basis that “it is glaringly improbable that Ms Hart’s evidence was a reconstruction”, the balance of the submission asserts specific error in several respects which led the primary judge to that conclusion. And that is how the arguments were developed orally. Accordingly, this appeal is not one within that category of “some, quite rare, cases, [wherein] although the facts fall short of being ‘incontrovertible’, an appellate conclusion may be reached that the decision at trial is ‘glaringly improbable’ or ‘contrary to compelling inferences’”: Fox at [29].

71 Thus, senior counsel for the appellant developed five discrete points, though there is a degree of overlap: (1) Ms Hart’s evidence was not speculative; (2) her evidence is corroborated by a contemporaneous record; (3) there is an explanation for her failure to refer to the advice given to the respondents; (4) she explained the reason for the lateness of her evidence; and (5) the evidence of the respondents should not have been preferred.

72 In contrast, and in broad summary, senior counsel for the respondents submits that properly understood, this ground is a challenge to the assessment of the credibility of the evidence given by Ms Hart and that it is not open to this Court to reach a different conclusion “because [it] thinks that the probabilities of the case are against, even strongly against” the relevant finding of fact and the rejection of the evidence of Ms Hart must stand “unless it can be shown that the trial judge ‘has failed to use or has palpably misused his advantage’ or has acted on evidence which was ‘inconsistent with facts incontrovertibly established by the evidence’ or which was ‘glaringly improbable’”: Devries v Australian National Railways Commission (1993) 177 CLR 472 at 479, Brennan, Gaudron and McHugh JJ.

73 In developing that submission, senior counsel relied upon the following matters:

(1) the stark contradiction between the evidence of Ms Hart and that of the respondents;

(2) the omission of any reference to the critical evidence in either of the outline witness statements of Ms Hart;

(3) the fact that Ms Hart only “remembered” her evidence during the course of the trial, and by reference to documents recently located;

(4) Ms Hart’s account is not supported by the objective evidence;

(5) the Option C floor plan is not a contemporaneous record that corroborates the evidence of Ms Hart;

(6) Ms Hart altered the door configuration shown on the floor plans on at least one occasion and without reference to the respondents;

(7) Ms Hart’s evidence was not corroborated by Mr Hu or Mr De Mooy; and

(8) in all of the circumstances the primary judge was correct to conclude that Ms Hart’s evidence was the result of a process of reconstruction by reference to certain documents.

74 To understand these arguments it is necessary to essay the evidence of Ms Hart and its context in some detail.

The evidence of Ms Hart and the sequence of meetings

75 I commence with a meeting between Ms Hart, Mr Hu and the respondents on 7 April 2017. Mr Ripani gave evidence in chief that he attended that meeting with the hard copy promotional book that he had earlier received upon his first attendance at the display suite in January 2017. His evidence was not given sequentially. Prior to the meeting, he and Mrs Ripani had prepared a handwritten list of matters to be discussed, which he transmitted by email to Mr Tran on 4 April 2017. His covering email in part reads:

As per our phone conversation. This is a rough on the briefs we would like to discuss with the Architect. You have seen our apartment and you can understand what we are looking for with this new one. We are keen to sit in with the Architect to have something discussed and drawn up.

Please advise when we will be able to meet.

Also as discussed with the comment included on the signed contract, the 21 one (sic) day cooling off period should be effective once we have had the drawings done and all confirmed.

76 The attached handwritten note under the title “Brief” lists as the first item: “inside/outside to blend seamlessly. Same colour finish inside to outside. Timber and stone”. This note is evidence that the respondents intended to discuss the façade opening at the meeting.

77 Returning to the meeting, Mr Ripani said in evidence (from T 386):

…---Well, I had the hard copy book with me. I had opened it up to the page of the render, and I expressed how much we loved the open space, the door opening, and the whole flow-through from the living to the outdoor area. We really like that, but we weren’t really keen on the interior design, and we would like to do something that was more us.

And did you give any sort of description about what might be necessary to make the interior of the apartment more you?--- Well, we just said we weren’t overly thrilled with what was put forward, and Kate had said that Rothelowman had some of their own interior designs, which she had actually brought out to have a look at.

Before I take you to that, was anything said to you when you raise the fact that you really love the open design, to suggest that might be---?--- Nothing was ever raised.

--- not part of the design of the apartment? Sorry?--- Nothing was ever raised.

78 The witness was then taken to the draft Rothelowman plan, confirmed that he recognised it and stated that it was presented by Ms Hart at the meeting. His evidence was that she said this was a plan that he and the respondents could look at, and they did. They expressed the view that they liked that plan more than the earlier concept plan. His evidence continued (from T 387):

Do you recall anything further about what was discussed amongst the people that were at that first meeting before it came to an end on the first occasion?--- Not really. We had made a number of comments about the floor plan and Kate was going to have a look at it and come back with a revised drawing.

…

From memory, it was simply whether you could recall whether anything else was discussed before that meeting came to an end apart from the one – matters that you’ve referred – you’ve told His Honour about?…Nothing else was discussed.

By the end of the first meeting, what was your belief as to what the apartment that you are purchasing, what its appearance would be where the interior meets the exterior along the terrace by the pool?--- Well, our understanding was that we were going to have---

Ms Costello: Objection.

Mr Stuckey: no, not we, what was your---?--- Sorry. Sorry.

--- Personal understanding, Mr Ripani?--- My – my understanding was that we were now focusing on the interior, because everything else was a given.

All right. And when you say it was given look, what did you think that was?--- The large, open door….

Was anything said in the course of that meeting when Ms Hart produced that Rothelowman plan to describe what sort of wall or barrier was drawn in that plan? Was that the subject of discussion, about what was shown in the plan between the terrace and the interior of the apartment?--- Absolutely not.

79 The meeting of 7 April 2017 occurred on a Friday. The following Monday, 10 April 2017, Mr Ripani emailed Ms Hart and said:

Good morning Kate.

It was really nice to meet you last Friday, Nina and I were quite excited about your floorplans that you had drawn up as an option to the ones we had seen. We look forward to seeing some revisions based on our discussions to your floor plans.

For now are you able to forward us your initial drawings you had done as Nina and I would love to look at them thoroughly.

Also when you have a chance could you please call as I would like to discuss the curved wall in the main living area.

Please advise,

Thanks again for your time on Friday it was really good,

80 Ms Hart replied to the respondents by email later on 10 April 2017. She attached a draft floor plan for apartment 1401, which is undated and is not designated by an alphabetical option letter:

81 Her email contains no relevant observations, apart from the fact that the attachments were floor plans for apartments 1401 and 1417. The plan for 1401 (when viewed in A3 format) clearly depicts two sliding doors with fixed mullions on the western façade between the pool and outdoor living area and the internal living and entertainment areas. This plan includes the relatively prominent note that: “Window size and location may vary. Refer to level plans for window locations”. Just what was meant by level plans was not explored in the evidence and no finding of meaning was made by the primary judge.

82 Mr Ripani responded by email on 11 April 2017, commencing with the sentence: “Thanks for the floor plans” and continued:

However, what we really wanted was not just the floor plan for Apartment 1401 but a copy of all the coloured images that you had drawn up for 1401. It was the coloured images of the Bar area, the walk in Cellar and so on.

I’m assuming its a big file but are you able to send it as a zip file or can you down load (sic) it onto a USB that I could collect if this is not a problem… Nina and I want to go over all the drawing (sic) you had for level 1401.

Also with regards to 1401 we want to talk to you about this wall that divides the two areas in the living room.

83 Ms Hart responded on 12 April 2017 and attached the Design Development Presentation for apartment 1401 as “presented to you last Friday”. That document is in concept form. It briefly describes the design approach, the location, the derivation of the building form and includes concept floor plans. She added that: “please note that the images and design are all work (sic) in progress and not final, resolved images”. The attachments included four versions of the concept plan for apartment 1401, each of which clearly depicts the intended door openings with mullions on the western façade together with sliding doors which are pellucid in illustrating that with the doors open, the maximum width was much less than as depicted in the render and that only two sliding doors were proposed. As an example there is this plan:

84 Mr Ripani replied to Ms Hart later that day by email as follows:

Hi Kate,

Exactly what I was asking for… Got it and downloaded it… Awesome… Thank you…

We are looking forward to seeing your revised drawings based on our discussions…

We will look at the small study in relation to the pool as well.

Also can we discuss the curved wall early next week as this Thursday might be a little difficult for me. I’m pretty much free any time next week.

We have to get you to Prima at some stage as well.

Thanks again and talk soon,

Cheers,

85 To this Ms Hart replied by email: “Yes we are looking into the variations to the planning as discussed last Friday. We will aim to have something back to you by Tuesday, Wednesday of next week”. That timeframe was not achieved by Ms Hart. Rather, on 26 April 2017 she emailed Mr Hu a revised floor plan Option A for apartment 1401 “for further client comment”. Mr Tran forwarded that email to Mr Ripani later that day. Of the Option A plan, Mr Ripani said in evidence (T 391):

Now, did you personally look at that plan when it was received from Kevin Tran in April 2017?--- Yes, I did.

And did you – what about it, did you note, if anything?--- Items that we had discussed at the time to be actioned were done, so – in particular the chevron flooring that runs outside.

86 This evidence indicates that the respondents gave studied consideration to the Design Development Presentation. Mr Ripani confirmed as much when questioned about the differences between the plans in the Design Development Presentation and the draft Rothelowman plan (from T 390):

Did you notice whether there were any changes about that plan from the earlier one you had been shown?--- Yes. The chevron flooring we – Kate had suggested that we take the chevron flooring pattern to the outside, so that when all the doors are open you had that seamless flow-through effect. So that was one of the main…

Let me ask you firstly, when was – when did Kate Hart say that?--- At the meeting.

That’s the first meeting?--- Yes.

And did she use those words, that you’re – to the best of your recollection, did she use those words?--- To the best of my recollection.

His Honour: So chevron, describing what might also be described as herringbone pattern, is that it?--- Yes.

87 On 26 April 2017, Mr Tran emailed the respondents and attached the Option A, revision A floor plan for the apartment dated 26 April 2017. That plan clearly depicts an alteration to the proposed glass door arrangement with fixed mullions on the western façade with an opening opposite the fireplace formed by sliding doors at significantly less width than the render:

88 The alteration to the proposed doors is that on this plan three sliding doors are depicted, with the widest opposite the fireplace. That plan is drawn to a scale of 1:100 at A3 size which allows one to accurately determine that opening width at 3.6m.