Federal Court of Australia

Swancom Pty Ltd v The Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 157

ORDERS

SWANCOM PTY LTD (ACN 161 447 605) Appellant | ||

AND: | THE JAZZ CORNER HOTEL PTY LTD (ACN 615 168 968) First Respondent BIRD’S BASEMENT PTY LTD (ACN 607 922 609) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal, to be assessed in the absence of agreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 408 of 2021 | ||

BETWEEN: | THE JAZZ CORNER HOTEL PTY LTD (ACN 615 168 968) Appellant | |

AND: | SWANCOM PTY LTD (ACN 161 447 605) Respondent | |

order made by: | YATES, ABRAHAM AND ROFE JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 13 september 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal, to be assessed in the absence of agreement.

[Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.]

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 This matter involves an appeal from the primary judge’s orders dismissing claims for trade mark infringement: Swancom Pty Ltd v The Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 328 (Primary Judgment or J) (the first appeal), and an appeal from the primary judge’s orders as to costs: Swancom Pty Ltd v The Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 729 (the Costs Decision or CD) (the second appeal).

2 The proceeding below concerned two live music venues located in Melbourne, one in the inner city suburb of Richmond and the other in the central business district of Melbourne, and the right to use trade marks which include the words “corner” and “corner hotel”.

3 Since 1995, the appellant in the first appeal, Swancom Pty Ltd (Swancom), has been the owner and operator of a live music and hospitality venue located at 57 Swan Street, Richmond, Victoria. The venue occupies a block that fronts (on three sides) each of Swan Street, Stewart Street and Botherambo Street, and thus sits at the junction of two street corners. The venue has been called the Corner Hotel for a long time (and prior to its ownership by Swancom).

4 Swancom is the registered owner of four registered trade marks which were the marks in suit in the infringement action:

(a) Trade Mark No 1388154 for CORNER HOTEL (with a filing date of 11 October 2010) registered in respect of services in classes 41 and 43;

(b) Trade Mark No 1442211 for CORNER (with a filing date of 10 August 2011) registered in respect of services in classes 41 and 43;

(c) Trade Mark No 1669900 for THE CORNER (with a filing date of 20 January 2015) registered in respect of services in classes 41 and 43; and

(d) Trade Mark No 1623364 for CORNER PRESENTS (with a filing date of 16 May 2014) registered in respect of services in class 41.

5 At the outset of the appeal hearing, Swancom’s senior counsel noted that Swancom no longer pressed an infringement case on the basis of the CORNER PRESENTS mark. The appeal was limited to marks (a) to (c), which we will refer to as the Swancom marks.

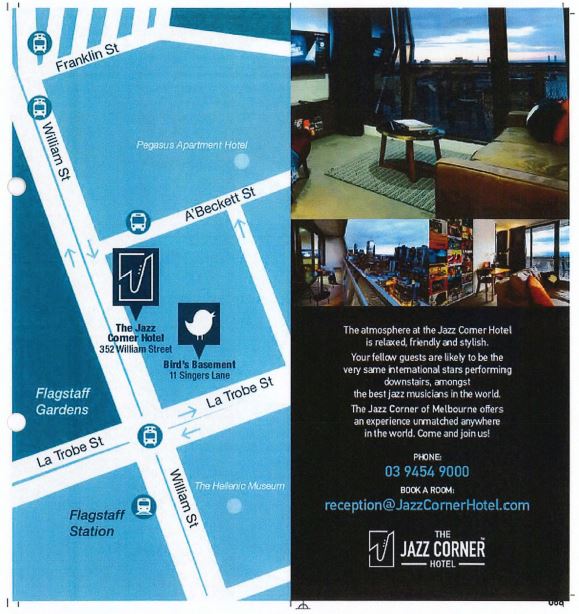

6 The first respondent in the proceeding below, The Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd (JCHPL), the second respondent, Bird’s Basement Pty Ltd (BBPL), and the third respondent, Saint Thomas Pty Ltd (STPL), conduct business from premises that occupy the block at 330-360 William Street, Melbourne. That building is next door to a smaller building that is on the north-east corner of the intersection of William and La Trobe Streets. Thus, the building at 330-360 William Street (which the primary judge referred to as the William Street building) is close to the corner of William and La Trobe Streets, but not actually on the corner. There are other business occupants of the William Street building, including Oaks Apartments which provides accommodation services.

7 JCHPL, BBPL and STPL conduct three distinct but related businesses within the William Street building:

(a) JCHPL conducts a hotel business called “The Jazz Corner Hotel”, which has the street address 352 William Street, Melbourne;

(b) BBPL operates a jazz music venue called “Bird’s Basement” which is located in the basement of the building and which has its primary street entrance at 11 Singers Lane, Melbourne, which is at the rear of the building; and

(c) STPL operates a café business called the “The Jazz Corner Café” within the building.

8 Swancom sued JCHPL, BBPL and STPL for trade mark infringement pursuant to s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act). It alleged that each had infringed the Swancom marks by using, without the licence or authority of Swancom, the following trade marks (which the primary judge referred to as the Jazz Corner marks):

(a) THE JAZZ CORNER OF MELBOURNE and JAZZ CORNER OF MELBOURNE (Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks);

(b) THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD and JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD (Jazz Corner of the World marks);

(c) THE JAZZ CORNER HOTEL, JAZZ CORNER HOTEL and JAZZCORNERHOTEL (Jazz Corner Hotel marks); and

(d) THE JAZZ CORNER CAFÉ, JAZZ CORNER CAFÉ and THEJAZZCNRCAFE (Jazz Corner Café marks),

in Australia, in relation to the following services:

(a) services of organising, conducting, providing and providing information in relation to live music performances (live music services); and

(b) ticket booking and reservation services for live music performances (booking services).

9 JCHPL, BBPL, STPL, and Albert Dadon (a director of those companies) cross-claimed in the proceeding below pursuant to s 88(1)(a) of the Act. The cross-claimants relied on two principal grounds to seek rectification of the Register by cancellation of the Swancom marks in respect of the registered services in class 41:

(a) first, relying on ss 88(2)(a) and 41 of the Act, the cross-claimants alleged that the Swancom marks were not capable of distinguishing Swancom’s services; and

(b) second, relying on s 88(2)(c) of the Act, the cross-claimants alleged that the use of the Swancom marks was likely to deceive or cause confusion.

10 Swancom denied the allegations and, in the alternative, contended that the Court should exercise its discretion not to cancel the Swancom marks.

11 The trial was limited to the issues of trade mark validity, infringement, injunctive relief, and declaratory relief. The issue of pecuniary relief was to be heard and determined separately.

12 The primary judge found that:

(a) JCHPL had used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services provided at Bird’s Basement: J[214];

(b) BBPL had not used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services: J[215];

(c) JCHPL and BBPL had used the Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks as a trade mark in relation to each and all of the businesses conducted from the William Street building, including the jazz club: J[219];

(d) STPL had not used the Jazz Corner Café marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services provided at Bird’s Basement: J[216]; and

(e) JCHPL, BBPL and STPL had not used the Jazz Corner of the World marks as a trade mark: J[221].

13 Ultimately, the primary judge dismissed the infringement case on the basis that none of the relevant Jazz Corner marks were deceptively similar to the Swancom marks. At J[255], the primary judge said:

255 … I conclude that the risk of an ordinary member of the public being confused about whether the live music services promoted by the use of the Jazz Corner marks have an association with the Corner Hotel (or the Swancom marks more generally) to be remote (a mere possibility). For that reason, I conclude that the relevant Jazz Corner marks are not likely to deceive or cause confusion and, therefore, are not deceptively similar to the Swancom marks.

14 In dismissing the cross-claim (aside from limiting the breadth of the class 41 registrations of the CORNER and THE CORNER marks), the primary judge held that: (a) the Swancom marks were capable of distinguishing Swancom’s professional live music services in respect of which they were registered from the live music services of other persons, based on their acquired distinctiveness at the time of their respective filing dates; and (b) at the time of filing the application for rectification, the use of the Swancom marks was not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

15 Subsequent to handing down the primary judgment, the primary judge heard argument regarding the breadth of the services in respect of which the CORNER and THE CORNER marks were registered in class 41, and as to costs. In the Costs Decision, the primary judge ordered that: the registered services be narrowed to match those specified for the CORNER HOTEL mark; the cross-claim be otherwise dismissed; and JCHPL pay Swancom’s costs of the cross-claim.

16 In the first appeal, Swancom challenges the primary judge’s finding as to deceptive similarity in the context of infringement, primarily on the basis that, in conducting the comparison required by s 120(1), his Honour failed to take into account his finding that the Swancom marks had acquired distinctiveness at their respective filing dates for the purposes of s 41 of the Act (Grounds 1 to 4).

17 Swancom also challenges the primary judge’s findings that JCHPL and BBPL had not used (THE) JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD as a trade mark (Grounds 5 and 6), and that BBPL had not used (THE) JAZZ CORNER HOTEL as a trade mark in respect of professional live music services (Ground 7).

18 JCHPL and BBL have filed a notice of contention supporting the primary judge’s findings as to non-infringement and contending that the primary judge ought to have also found that:

(a) (THE) JAZZ CORNER HOTEL was not used by JCHPL as a trade mark in relation to the provision of live music services; and

(b) (THE) JAZZ CORNER OF MELBOURNE was not used by JCHPL or BBPL as a trade mark in relation to the provision of the live music services.

19 In the second appeal, JCHPL challenges the primary judge’s orders that it pay Swancom’s costs of the cross-claim.

20 For the reasons set out below, we consider that both appeals should be dismissed.

The primary judge’s findings

Factual distinctiveness of the Swancom marks: s 88(2)(a) of the Act

21 As we have noted, in its cross-claim, JCHPL sought rectification of the Register on two grounds, the first relying on the ground of opposition in s 41 of the Act.

22 The form of s 41 prior to its amendment by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (RTB) was the applicable form for the CORNER and CORNER HOTEL marks. The form of s 41 post the RTB amendments applied to the THE CORNER mark. The primary judge noted at J[127] that the respondents’ submissions were made on the basis that the relevant principles governing the issue of capability to distinguish were not altered by the RTB amendments to s 41. The primary judge proceeded on that basis. There was no challenge to that approach on appeal.

23 The primary judge held at J[162] that it was not necessary to reach a concluded view on whether the CORNER HOTEL mark was not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish Swancom’s registered services from the services of other persons (pre-RTB s 41(6)(a)), or was to some extent, but not sufficiently, inherently adapted to distinguish Swancom’s registered services (pre-RTB s 41(5)(a)). His Honour found at J[155], [159] and [162] that Swancom’s use of the CORNER HOTEL mark alone, prior to filing, had resulted in that mark in fact distinguishing Swancom’s live music services (as per the pre-RTB s 41(6)(a)). The primary judge also held at J[163] that similar conclusions applied in respect of the CORNER and THE CORNER marks.

24 The Corner Hotel premises include the usual facilities associated with a public hotel. It houses a front bar, a rooftop bar and restaurant and a number of other function rooms and other areas, as well as a live music area, known as the “bandroom”, which can accommodate 750 to 800 patrons. The bandroom also has a bar serving drinks to customers during performances. The Corner Hotel does not provide accommodation services.

25 At J[61] and [62] the primary judge stated:

61 Overall, I am satisfied on the evidence that the Corner Hotel has a strong reputation in Melbourne and beyond as a venue for professional live music performances with the following characteristics:

(a) the venue is located in Richmond;

(b) the venue is medium size (for about 800 people);

(c) the venue is in a hotel setting where patrons usually stand to watch and listen to the performance and alcoholic drinks can be purchased during the performance; and

(d) the styles of music performed at the venue are within the wide spectrum of popular musical genres that emerged from the twentieth century, from the roots of folk, blues and jazz music through to rock music in all its forms.

62 I am satisfied that that reputation existed as at the filing date for the earliest Swancom mark, but also that the reputation has continued to grow in the years subsequent to the filing date.

26 At J[63], the primary judge found that the following business activities were intrinsic to the conduct of a business providing a venue for professional live music performances:

• Booking bands and artists to perform on specific dates;

• Marketing and promoting the performance of the bands and artists on the given dates;

• Selling tickets to the performances; and

• Operating the venue for the performances, including providing all necessary sound equipment and personnel, safety and security personnel, bar staff and cleaning staff.

27 At J[65] the primary judge took judicial notice of the fact that, in Australia, hotels or, more colloquially, “pubs” (a business licensed to serve alcoholic drinks on the premises) are often located on street corners. He accepted as a fact that hotels often occupy a street corner and observed at J[66] that it “is therefore unsurprising that the evidence showed that the word ‘corner’ has been applied to hotels as a business name in Australia since the 19th century”.

28 The primary judge also took judicial notice of the fact that, in Australia, hotels often provide entertainment to patrons including the viewing of live sporting events and live music (at J[69]). He noted that there is a significant difference between a hotel providing entertainment to patrons in the form of a solo artist playing the guitar or piano, which entertainment is typically provided free of charge to patrons to attract their custom (for food and beverages), and a hotel conducting a professional live music venue where patrons attend to view the musical performance and must purchase a ticket to attend.

29 The primary judge considered that the services offered by Swancom could be characterised as professional live music services, which were to be contrasted with the provision of live music free of charge by hotels in order to attract sales of drinks and food.

30 Notwithstanding the primary judge’s finding that it was not necessary for him to reach a concluded view as to whether, or to what extent, the Swancom marks were inherently adapted to distinguish Swancom’s registered services (given his findings on acquired (factual) distinctiveness), there are aspects of his Honour’s analysis of that question which remain relevant to the issues to be decided in the first appeal.

31 At J[151], the primary judge found that the phrase “corner hotel” had a clear primary meaning to consumers of hotel services, and a secondary, colloquial connotation:

151 The phrase “corner hotel” has a clear primary meaning to consumers of hotel services. The words describe a hotel located on a street corner. I also accept JCHPL’s submission that the words carry a secondary, colloquial, connotation of a hotel that is “round the corner”, meaning that the hotel is local or readily accessible. Each of those meanings refers to a characteristic of hotel services. A hotel is a venue at which a range of services are provided, principally alcoholic drinks served on the premises, prepared meals and, to a lesser extent, accommodation. The location of the venue is an important characteristic of the services that are provided. There is a limit to the distance that consumers will travel to visit a hotel to consume drinks and have a meal. The words “corner hotel” therefore describe a characteristic of the services provided at hotels. The words are apt to describe the location of a hotel in a primary sense as being located on a street corner and, in a secondary sense, as being “local” or accessible. The evidence shows that a significant number of hotel businesses have chosen that name for their business. I infer that they have done so for the ordinary signification of the words in both the primary and secondary sense.

32 At J[152], the primary judge found that the phrase “corner hotel” is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish ordinary hotel services (alcoholic drinks served on the premises, prepared meals and, to a lesser extent, accommodation). He considered that it was questionable whether any amount of use of that phrase would render it capable of distinguishing such services. However, the primary judge noted that the cross-claimants made no challenge to the Swancom marks in so far as they were registered in respect of services in class 43. The cross-claimants only challenged the marks in so far as they were registered in respect of services in class 41.

33 At J[153] and [154], the primary judge rejected Swancom’s submission that the words “corner hotel” have no signification in respect of the class 41 services: live music, ticket booking and related services. His Honour observed at J[154]:

154 The words have the same meaning as discussed above in respect of hotel services – a hotel that is located on a street corner and which might be regarded as “local” or “accessible”. That meaning has some signification for persons who wish to attend a live music performance, conveying that the performance is in a hotel (so located) and, as such, the audience size is limited to the hotel capacity (typically, fewer than 1,000), patrons are likely to stand when watching the performance and will be able to consume alcoholic drinks.

34 However, as we have recorded, the primary judge then found at J[155] and [159], based on the evidence of use of the mark before the filing date, that the CORNER HOTEL mark was, at its filing date, capable of distinguishing Swancom’s services from the services of other persons. This conclusion related to the services in class 41 for which the CORNER HOTEL mark was registered:

Organising, conducting, providing and providing information in relation to entertainment and cultural activities, being live music performances; providing facilities for live music performances; ticket booking and reservation services for entertainment and cultural activities being live music performances; publication services relating to these services; provision of all such services over a global computer network.

35 At J[156], the primary judge observed that the evidence of use of the CORNER HOTEL mark was supported by the opinions of the industry witnesses, none of whom was aware of another live or recorded music venue trading under the names “The Corner”, “The Corner Hotel”, or a name incorporating the word “corner’.

36 At J[163], the primary judge reached the same conclusion with respect to the CORNER and THE CORNER marks.

Use likely to deceive or cause confusion: s 88(2)(c) of the Act

37 The second ground on which the cross-claimants sought rectification of the Register was cancellation of the Swancom marks pursuant to s 88(2)(c) of the Act. That section provides for cancellation on the basis that, because of the circumstances applying at the time when the application for rectification is filed, the use of the trade mark is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

38 At J[175], the primary judge held that use of the Swancom marks was not likely to deceive or cause confusion at the date on which the application for rectification was filed. He also observed that use of the word “corner” in the name of a local business such as a hotel, café or bar is common and descriptive, and there was no real or tangible likelihood of the entertainment services provided by such a business being confused with the services provided by Swancom.

Infringement: s 120(1) of the Act

39 Swancom’s infringement case relied solely on s 120(1) of the Act. Section 120(1) provides that a person infringes a trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered. It was not suggested that any of the Jazz Corner marks were substantially identical to the Swancom marks.

Use in relation to services in respect of which the Swancom marks are registered

40 As we have noted, the primary judge found (at J[214]) that JCHPL had used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services provided at Bird’s Basement (at J[219]), and that JCHPL and BBPL had used the Jazz Club of Melbourne marks as a trade mark in relation to each and all of the businesses conducted from the William Street building, including the jazz club.

Deceptive similarity

41 Before commencing his consideration of whether the Jazz Corner marks were deceptively similar to the Swancom marks for the purposes of s 120(1), the primary judge began with s 10 of the Act. Section 10 provides that a trade mark is taken to be “deceptively similar” to another trade mark if it “so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion”.

42 The primary judge then summarised (at J[224] – [229]) a number of well-known principles of trade mark comparison, noting that the relevant comparison is between the marks themselves and that, in considering deceptive similarity, the comparison is not a side-by-side comparison. His Honour noted that the comparison does not involve an inquiry into the reputation of the marks, such as might be undertaken in a passing off action or in a proceeding in which misleading or deceptive conduct is alleged. His Honour also noted, however, that, in assessing the likelihood of deception or confusion, it is still relevant to consider the relevant trade or business, the way in which the particular goods or services are supplied, and the character of the probable acquirers of the goods or services.

43 In light of the way in which Swancom advances its appeal, we note that, at J[236], the primary judge recorded Swancom’s submission that the reputation of the Swancom marks was irrelevant to the inquiry in circumstances where those marks cannot be said to have a degree of widespread notoriety: CA Henschke v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1539 at [52] – [53] per Ryan, Branson and Lehane JJ and Australian Meat Group v JBS Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 268 FCR 623 at [41] – [42] per Allsop CJ, Besanko and Yates JJ.

44 At J[244], the primary judge took as the starting point for his analysis, his finding that both JCHPL (in respect of the Jazz Corner Hotel and Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks) and BBPL (in respect of the Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks) had used those marks as trade marks in relation to live music services. As we have noted, this finding is challenged in the notice of contention.

45 At J[245], the primary judge observed that there was an obvious similarity between the Swancom marks and the relevant Jazz Corner marks. All the Swancom marks and the relevant Jazz Corner marks have the word “corner” in common. The CORNER HOTEL mark and the Jazz Corner Hotel marks have two words in common. The primary judge said:

245 While the similarity between the marks must give rise to some prospect of confusion, the question is whether there is a real or tangible risk of such confusion as opposed to a mere possibility. That question is not answered simply by observing the degree of similarity (in the sense of the number of common words in the marks), but by considering the effect of the similarity. Attention must be given to the impression produced by the entirety of the marks, recognising that one word or feature of a mark can be more striking and memorable than another.

46 At J[246], the primary judge noted that the primary issue in dispute was the effect or impression on the ordinary consumer of the inclusion of the word “jazz” in the Jazz Corner marks. Neither party challenged that the ordinary consumer was the appropriate prospective consumer for the assessment of deceptive similarity. There was no suggestion that the relevant services were part of a specialised market.

47 The primary judge observed that the parties approached the question of deceptive similarity from opposite directions. Swancom contended that the striking or memorable feature of the marks was the word “corner”, largely on the basis that that word is distinctive in the context of live music services. Swancom submitted that the word “jazz” is wholly descriptive in that context. JCHPL, BBPL and STPL contended that the words “corner” and “hotel” were ordinary words with descriptive meanings which are in common use in the hotel and hospitality industries. The word “jazz” was a more memorable word, even if it was descriptive of a style of music. The primary judge accepted the latter contentions.

48 Grounds 1 to 4 of Swancom’s appeal focus on the primary judge’s reasoning at J[247] – [251] as to why he accepted these contentions:

247 As discussed earlier, the words “corner hotel” have a clear primary meaning to consumers of hotel services, being a hotel located on a street corner, and a secondary, colloquial connotation of a hotel that is local or readily accessible. Those meanings also have some signification for persons who wish to attend a live music performance, conveying that the performance is in a hotel (so located) and patrons are likely to stand when watching the performance and will be able to consume alcoholic drinks. The word “corner” on its own conveys the same meaning, namely a location on a street corner and which might be regarded as “local” or “accessible”. Such a meaning would be conveyed in connection with many businesses, including particularly hospitality businesses. The word has some signification in respect of professional live music services, although it can be accepted that the meaning is less direct than in respect of the words “corner hotel”.

248 Significantly, the evidence shows widespread use of the word “corner” in relation to hotel and hospitality businesses. The word “hotel” is also, of course, used ubiquitously in the hotel industry. It is well-established, and accepted by Swancom, that if it can be shown that elements of a trade mark are in common use in the trade, then those elements will be discounted to some extent in comparing the two marks for the purposes of deceptive similarity, on the basis that consumers will tend to focus on the more distinctive aspects of the mark: Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 127 per Gummow J. Relying on observations by Foster J in Alcon Inc v Bausch & Lomb (Australia) Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 1299; 83 IPR 210 at [74], Swancom submitted that regard can only be had to usage in the relevant trade, here live music services, and not usage in other areas of trade (for example hotel and hospitality services more broadly). I reject that submission. The observations of Foster J were made in the context of s 24 of the TMA and the question of distinctiveness of a registered trade mark. In MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd (1998) 90 FCR 236 (MID), which concerned the trade mark “Chifley Tower” registered in respect of property management services, the Full Court considered it relevant to the question of deceptive similarity that the word “Chifley” was familiar as the name of a former Prime Minister and its use in geographical and other contexts (such as suburbs, shopping arcades and a restaurant). In concluding that the respondent would not infringe the registered trade mark by using the name “Chifley” on hotels, the Full Court concluded that an ordinary member of the public “should be credited with a general knowledge that there are several such applications” of the use of the name Chifley (at 246)

249 The evidence with respect to the trade usage of the names “Corner Hotel” and “Corner” is set out earlier and need not be reproduced. It is sufficient to note that, from the earliest days of European settlement of Australia to the present day, hotels have been named the “Corner Hotel”. The evidence also identified a number of other hospitality businesses (cafés and bars) that also use the name “Corner” or a close derivative. Consistently with the conclusion reached by the Full Court in MID, I consider that ordinary members of the public should be credited with a general knowledge that there are many businesses, broadly in the hospitality industry, which use the name “Corner”. Such is the familiar use of the name “Corner” that almost any adjective added to that word is likely to create a distinct impression to an ordinary member of the public. For example, Blue Corner, Shady Corner, High Corner or Nature’s Corner each create a different impression, despite the common use of the name “Corner”.

250 It must be accepted that the word “jazz” has a descriptive meaning. However, in comparison to the words “corner” and “hotel”, it is a word that leaves a more striking impression. That is for two reasons. First, it is less commonly used, particularly in the hotel and hospitality industry (there being no evidence of other use in the trade). Second, the word has an evocative resonance because jazz music itself (whether it is appreciated or disliked) is evocative. As a musical form, jazz uses melodic and harmonic elements derived from the blues (including the dissonant and expressive “blue” notes, classically the flattened third, fifth and seventh notes in the major scale), syncopated rhythms and is marked by improvisation in which the music is created or developed during performance. I consider that ordinary members of the public should be taken to be familiar with the overall style of jazz music, even if they are not familiar with the musical techniques that give jazz its distinctive style. The commonly used adjective “jazzy”, derived from the noun “jazz”, means bright, colourful or showy, reflecting the recognised characteristics of jazz music.

251 The addition of the word “jazz” to the word “corner” or the words “corner hotel” gives the composite phrase a distinct sound and meaning. In my view, attention is immediately drawn to the word “jazz” and the words “corner” or “corner hotel” assume a secondary role in the phrase. The name “Jazz Corner” suggests a corner (or location or place) devoted to jazz music in some manner. The name “Jazz Corner Hotel” suggests a hotel named “Jazz Corner”, creating the same impression. As is the case with other adjectives added to the name “Corner”, I consider that the addition of “Jazz” is likely to create an impression or idea in the mind of an ordinary member of the public that is distinct from the impression or idea created by the CORNER or CORNER HOTEL marks.

49 As we have noted, the primary judge concluded (at J[255]) that the relevant Jazz Corner marks were not likely to deceive or cause confusion and were therefore not deceptively similar to the Swancom marks. Thus, the primary judge held that there was no infringement pursuant to s 120(1) of the Act.

The first appeal

Swancom’s submissions: Grounds 1 to 4

50 Swancom submits that in conducting the assessment of whether the relevant Jazz Corner marks were deceptively similar to any “registered trade mark” of Swancom, the primary judge was required to assume that an intending purchaser or viewer had knowledge of the registered mark alleged to have been infringed (Idameneo (No 789) Ltd v Symbion Pharmacy Services Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 164 at [57] citing Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380 at [97]).

51 Swancom submits that, in the case of a mark whose capacity to distinguish is based on distinctiveness in fact (for example, pre-RTB s 41(6)(a)), the mark has an acquired distinctive “meaning” which forms part of the knowledge of the mark that should be credited to ordinary members of the public.

52 Swancom submits that, having found that the CORNER HOTEL, CORNER and THE CORNER marks were distinctive in fact of Swancom’s live music services at the time of filing, such that they were capable of distinguishing Swancom’s professional live music services, the primary judge, when assessing the question of deceptive similarity, should have credited this acquired distinctive meaning to the ordinary members of the public who encounter the relevant Jazz Hotel marks.

53 Swancom submits that attributing the acquired distinctive meaning to the Swancom marks was necessary to “give full and proper effect to the exclusive proprietary rights duly granted to Swancom under ss 20, 21, 41 and 120(1)” of the Act. This includes the right to restrain others from using marks which are deceptively similar to the registered marks.

54 Swancom submits that a hypothetical consumer, credited with knowledge of the acquired distinctive meaning of CORNER HOTEL in respect of live music services, would be caused to wonder whether those services, provided under the Jazz Corner Hotel marks, might be from a sister venue of the Corner Hotel with a focus on jazz.

55 We note that Swancom’s senior counsel confirmed that, for the purposes of its appeal, Swancom was not contending that the Swancom marks were notoriously ubiquitous.

56 Swancom submits that, in undertaking his assessment on whether the Jazz Corner marks were deceptively similar to the Swancom marks, the primary judge wrongly discounted the effect of the words “corner hotel” and “corner” by failing to take into account the fact that there was no other live music venue trading under the names THE CORNER or CORNER HOTEL and by distracting himself by focussing on the perception of consumers of hotel and hospitality services, when the infringement claim related to use in relation to services in respect of which the Swancom marks were registered: live music services.

57 Swancom submits that these asserted errors “infected” the primary judge’s analysis of the word “jazz” in the impugned marks which, Swancom submits, is “utterly descriptive”. Swancom submits that the primary judge failed to consider that the Jazz Corner Hotel marks incorporate the whole of the distinctive mark CORNER HOTEL. Swancom also submits that the primary judge gave inappropriate weight to the consideration that consumers of live music services can be expected to be discerning with their choices.

The respondents’ submissions: Grounds 1 to 4

58 From this point, we will refer to JCHPL and BBPL as the respondents (noting that STPL is not a party in the first appeal).

59 The respondents submit that the principles for assessing deceptive similarity set out by the primary judge accord with the correct approach when undertaking trade mark comparison for the purpose of determining infringement.

60 The respondents submit that, in assessing the likelihood of deception or confusion for the purposes of infringement, the Court is to consider the marks at issue in the relevant trade or business, the way the particular services are supplied, and the character of the probable acquirers of the services. The respondents submit that this was not a case where the marks related to services supplied only to a specialised market. They submit that the primary judge correctly considered the character of the marks, and the primary and colloquial meanings of “corner hotel” and “hotel” for the ordinary person whose reaction was in question.

61 The respondents submit that, in circumstances where it was conceded by Swancom that the Swancom marks do not have a reputation at the “level of notoriety where it becomes relevant to the statutory task”, it is well established that the reputation of the allegedly infringed mark is irrelevant to the statutory enquiry.

62 The respondents submit that Swancom’s approach seeks to eliminate the common experience of the meaning of words. The respondents submit that, when determining trade mark infringement, it is not appropriate to go back to the initial question posed by s 41 of the Act to consider the effect of Swancom’s actual use of the marks prior to filing. The issue under s 120(1) that is relevant to the present appeal is not whether the alleged infringer’s conduct is deceptive or confusing, but whether the alleged infringer’s trade mark is deceptively similar. The circumstances of Swancom’s actual use of the Swancom marks pre-filing, in order to satisfy the requirement of s 41, is irrelevant: PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd (2021) 160 IPR 174 at [111] per Jagot, Nicholas and Burley JJ.

Consideration: Grounds 1 to 4

63 As Branson J observed in Blount v Registrar of Trade Marks (1998) 83 FCR 50 at 55, crucial to the concept of a trade mark is its capacity to distinguish the goods or services of one person from the goods or services of another.

64 In that case, her Honour rehearsed the history of the legislative amendments that allowed registration of marks that were only capable of distinguishing on the basis of the prior use of the mark. Under the Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth), it was established that certain marks could never be regarded as entitled to registration even though they were, as a matter of fact, plainly distinctive of the trade mark applicant’s goods. Marks falling in that category were typically geographical names and laudatory or descriptive terms. Things changed with the enactment of the present Act. Section 41(6) was introduced to allow for the registration of such marks in certain circumstances.

65 In Blount at 61, Branson J observed:

61 The concept of adaption to distinguish, which was, as Gummow J pointed out in the Oxford University Press case, central to s 26 of the 1955 Act, is not reflected in s 41 of the Act. Section 41 is concerned with capacity to distinguish. As s 41(6)(a) makes plain, a trade mark which is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish may nonetheless be treated under the Act as capable of distinguishing if, by reason of past use, it does in fact distinguish. The Act appears plainly to disclose an intention that it should no longer be the case that a trade mark which is “100 per cent distinctive in fact” should not be able to achieve registration (as to the expression “100 per cent distinctive in fact” see the Oxford University Press case per Lockhart J at 511 and Gummow J at 523). This conclusion is confirmed by recommendation 4B of the report of the Working Party:

Inherent distinctiveness, or acquired distinctiveness or a combination of both, should establish that a mark is capable of distinguishing the specified goods or services, and justify registration.

66 Thus, under the newly introduced s 41(6), a mark which had no inherent capacity to distinguish, could acquire distinctiveness in fact through the prior use of the mark, sufficient to justify the registration of the mark. Neither party suggested that the registrability of such marks was changed by the RTB amendments to s 41 of the Act. Nothing in this appeal turns on the subsequent amendments that have been made to s 41. Further, the parties’ submissions were directed to the acquired distinctiveness of the Swancom marks which enabled them to be registered, regardless of the form of s 41 pursuant to which they were registered.

67 The process by which a trade mark is assessed to be registrable and achieves registration, including an assessment of whether a trade mark falls foul of any of the grounds for rejecting a trade mark application, is a separate and distinct exercise from comparing marks to determine whether a registered trade mark is infringed pursuant to s 120(1) of the Act.

68 Once registered, all marks are treated equally for consideration of whether they are infringed pursuant to s 120(1) of the Act, irrespective of how they came to be registered. As the Full Court said in Henschke in relation to the test of deceptive similarity:

43 But there is another important aspect of infringement by use of a deceptively similar trade mark. It is that the test of deceptive similarity must be applied whether the mark of which infringement is alleged is newly registered and almost unknown or has been prominently displayed on well-known merchandise for many years. It must also be applied where the mark appears on goods (or in advertisements of goods) commonly seen, for example, on supermarket shelves in Sydney but rarely seen in Victoria or South Australia. The consumer posited by the test is hypothetical, although having characteristics of an actual group of people.

69 The deceptive similarity enquiry for trade mark infringement purposes is a limited one. Section 10 of the Act makes clear that the essential task is one of trade mark comparison; it is the resemblance between the two marks that must be the cause of the likely deception or confusion.

70 The test for deceptive similarity has been long settled. The authorities make clear that the comparison involves the ordinary consumer’s imperfect recollection of the registered mark. The ordinary consumer is not to be credited with any knowledge of the actual use of the trade mark, or of any acquired distinctiveness arising from use of the mark prior to filing.

71 In Australian Woollen Mills v F.S. Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641, Dixon and McTiernan JJ described it as follows (at 658):

But, in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained.

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. The effect of spoken description must be considered. If a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods, then similarities both of sound and of meaning play an important part. The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard. Evidence of actual cases of deception, if forthcoming, is of great weight.

72 Equally well known is the following passage explaining the relevant comparison from the judgment of Windeyer J in Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 415:

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. The marks are not now to be looked at side by side. The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff's mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the defendant's television exhibitions.

73 In New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray-Goulburn Co-operative Company Ltd (No 1) (1989) 14 IPR 26, in a passage not affected on appeal, Gummow J said at 67:

In determining whether MOO is deceptively similar to MOOVE, the impression based on recollection (which may be imperfect) of the mark MOOVE that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have, is compared with the impression such persons would get from MOO; the deceptiveness flows not only from the degree of similarity itself between the marks, but also from the effect of that similarity considered in relation to the circumstances of the goods, the prospective purchasers and the market covered by the monopoly attached to the registered trade mark: Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414–15; [1963] ALR 634; 1B IPR 523 at 528–9; Polaroid Corp v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491 at 498. The latter case is also authority (at 497) for the proposition that the essential comparison in an infringement suit remains one between the marks involved, and that the court is not looking to the totality of the conduct of the defendant in the same way as in a passing off suit.

74 This passage was approved by the Full Court in Henschke at [44] and more recently by the Full Court in Combe International Ltd v Dr August Wolff GmbH & Co KG Arzneimittel (2021) 157 IPR 230 at [27] per McKerracher, Gleeson and Burley JJ and in Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd & Ors v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235 at [64] per Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ; and PDP Capital at [97] per Jagot, Nicholas and Burley JJ.

75 Justice Yates summed up the test for deceptive similarity in Optical 88 at [111]:

111 At the end of the day the question of deceptive similarity is one to be resolved in a given case by judicial estimation based on the visual and aural impression created by each mark and on the likely effect to be produced by each mark on the minds of likely customers of the goods and services in the course of the ordinary conduct of affairs.

(Citation omitted.)

76 It is necessary to commence the deceptive similarity enquiry having regard to the prior registered mark and the notional consumer’s impression or recollection of that mark. The Full Court in PDP Capital noted (at [97]):

97 The distinction between consideration of whether one mark is deceptively similar to another, rather than substantially identical, lies in the point of emphasis on the impression or recollection which is carried away and retained of the registered mark when conducting the comparison…. [A]llowance must be made for the human frailty of imperfect recollection.

77 The notional consumer’s imperfect recollection of the registered mark is central to the test for deceptive similarity. The authorities make clear it is the imperfect recollection of the mark as registered, not any knowledge about the actual use of the mark, or any reputation associated with the mark.

78 The notional consumer’s imperfect recollection of the mark is based on the assumption that the consumer has seen the registered mark itself: Crazy Ron’s Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd (2004) 61 IPR 212 per Moore, Sackville and Emmett JJ at [81].

79 In MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd (1998) 42 IPR 561, the Full Court (at 570) noted the artificiality of the question to be asked, and observed that the person who may be caused to wonder is not one who knows of the actual business of the proprietor of the registered mark, the goods it produces, or the services it provides.

80 There is no scope under s 120(1) to consider the reputation associated with any mark, save (perhaps contentiously) where reputation is a matter of notoriety: Optical 88 per Yates J at [96], Henschke at [44]–[45] and Australian Meat Group at [41]–[42]. The primary judge correctly placed no reliance on the reputation associated with the Swancom marks: J[254].

81 The Full Court in Henschke carefully and comprehensively discussed the place of reputation in trade mark infringement and observed at [45] that it was not easy to see what relevance the reputation an applicant may have in a particular mark (even the “icon status” of that mark) has in an action for infringement brought under s 120(1) of the Act (the Court noted the contrast, in this regard, with infringement under s 120(3) of the Act). There, the Full Court closely analysed four cases which were said to involve a question of infringement by a use of a deceptively similar mark, and in which the reputation of the mark allegedly infringed had been taken into account. Those cases, the Full Court said at [52], were authority for no wider proposition than this:

52 … in assessing the nature of a consumer’s imperfect recollection of a mark, the fact that the mark, or perhaps an important element of it, is notoriously so ubiquitous and of such longstanding that consumers generally must be taken to be familiar with it, and with its use in relation to particular goods or services is a relevant consideration.

82 As we have emphasised, Swancom does not contend that the Swancom marks were notoriously ubiquitous.

83 The authorities emphasise that the imperfect “impression or recollection” of the registered mark which is carried away by the notional consumer for the purposes of assessing deceptive similarity in the context of s 120(1) of the Act is the impression or recollection that is taken from their observation of the registered mark. In the same way that any reputation in the registered mark or idiosyncrasies in its actual manner of use are to be ignored, the consumer’s impression and recollection of the registered mark is not to be augmented by knowledge of any factual distinctiveness that the mark may have acquired through use before its filing date.

84 Swancom places reliance on references in the cases to the notional consumer’s “knowledge” of the mark in support of its contention that the knowledge of the mark to be attributed to the consumer, when assessing deceptive similarity, includes the “acquired distinctive meaning” of a mark. These cases concern marks registered pursuant to the pre-RTB s 41(6): Optical 88 at [112] and Idameneo at [57]. The passing references in these two cases to the notional consumer’s “knowledge” of the mark do not contemplate anything other than the well-known and long standing test for deceptive similarity. The knowledge of the mark credited to the notional consumer is no more than the imperfect recollection of the registered mark, as referred to in the authorities.

85 Specifically, in the context of discussing the assessment of deceptive similarity, Yates J in Optical 88 said (at [112]):

112 The question of the impression of the marks on the minds of likely customers is important because, although they are assumed to have knowledge of the mark alleged to have been infringed, those customers are not to be treated as having perfect recollection of the mark in all its details. Quite to the contrary; in considering the question of deceptive similarity, allowance must be made for imperfect recollection based on impression.

(Citations omitted.)

86 It is clear that his Honour’s use of “knowledge” in this passage in Optical 88 was not conveying the broader concept of knowledge for which Swancom contends. His Honour’s reference to “knowledge” was made in the context of his discussion of the well-known test for deceptive similarity in Australian Woollen Mills at 659, and the imperfect recollection of the registered mark. His Honour’s comments were made after he had expressly stated earlier, at [96], that it is generally recognised that, for the purposes of trade mark infringement under s 120(1) of the Act, consideration of the trade mark owner’s reputation in the registered mark is not relevant “save (perhaps somewhat contentiously) where reputation is a matter of notoriety”. At [98], his Honour contrasted the position under s 120(3) where, in that context, actual knowledge of the mark is “all important”.

87 The Full Court in Idameneo referred, at [57], to the above passage from Optical 88 and observed that “the statutory criterion of ‘deceptive similarity’ assumes that an intending purchaser or viewer has knowledge of the mark alleged to have been infringed”. In that case, the Court was construing a contractual term and considering the use of a trade mark in a specialised market. The Court meant no more than that, in assessing deceptive similarity, the notional consumer is taken to have an imperfect recollection of the registered mark in accordance with the long standing authorities discussed above.

88 In assessing deceptive similarity, the context of the surrounding circumstances is not to be ignored. Context is all important: Shell at 422. In Optical 88, Yates J said (at [94]):

94 As Australian Woollen Mills makes clear, the comparison takes place in a particular context in accordance with a particular standard: “the course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass” affords the standard in determining whether the impugned mark is, properly judged, “deceptively similar”.

89 But consideration of the context of the surrounding circumstances in which the use occurs does not open the door for a detailed examination of the actual use of the registered mark, or any consideration of the reputation associated with the mark. The enquiry into the surrounding circumstances that is required should not be confused with the wider enquiry of the kind that might be undertaken in a passing off action or a claim of misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law: Optical 88 at [95] per Yates J. Such a wider enquiry into goodwill, if any, around the mark is not appropriate: Henschke at [44]; Pacific Publications Pty Ltd v IPC Media Pty Ltd (2003) 57 IPR 28 per Beaumont J at [102].

90 The deceptiveness that is contemplated must result from similarity in the competing marks; but the likelihood of deception must be judged not by the degree of similarity alone, but by the effect of that similarity in all the circumstances, including against the background of the usages of the particular trade: Shell at 410 and 416 per Windeyer J. In Henschke (at [42]) the surrounding circumstances were held to include the way in which wine is marketed and the knowledge that the wine market was a crowded one with topographical and geographical reference being common.

91 In MID Sydney, the surrounding circumstances included the widespread use of the word “Chifley” in contexts other than the property management services in respect of which the mark was registered. The Full Court considered whether the mark “Chifley Tower”, registered in respect of property management services, was deceptively similar to the name “Chifley” used in connection with hotel related services. The Full Court noted that “Chifley” was familiar not only as the name of a former Prime Minister but, as the evidence showed, also from its use in a number of geographic and other contexts including suburbs, districts or places known as “Chifley”, as well as a Chifley Arcade and a well-known restaurant “The Chifley” in Canberra. The Full Court stated (at 570):

The ordinary person whose reaction is in question need not be credited with an encyclopaedic knowledge of everything to which the name “Chifley” has been applied, but should be credited with a general knowledge that there are several such applications.

92 In PDP Capital, the Full Court, at [111], observed that “[b]eyond having a general bearing on the habits and practices of consumers, more granular detail of actual trade circumstances of either parties’ conduct is not relevant to the inquiry” as to whether the alleged infringer’s trade mark is deceptively similar to the registered trade mark. The Full Court identified that as an important distinction between the enquiry for s 120(1) and the broader enquiry for passing off or misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law.

93 Contrary to Swancom’s submission, the use by Swancom and its predecessors of CORNER, THE CORNER and CORNER HOTEL for professional live music services that contributed to satisfying the requirements for their registration as trade marks by reason of their acquired distinctiveness, was not a relevant consideration when determining the question of deceptive similarity for the purposes of s 120(1) of the Act, beyond having a general bearing on the habits and practices of consumers, as the Full Court noted in PDP Capital. However, Swancom’s primary submission in this appeal is, in substance, really no more than a contention that, for the purposes of determining the question of deceptive similarity in the context of infringement, the primary judge should have taken into account Swancom’s reputation in the Swancom marks. We reject that contention. It is contrary to established principle. Correctly, the primary judge placed no reliance on the reputation associated with the Swancom marks for that purpose: J[254]. Therefore, error, in this respect, has not been established.

94 We are not persuaded that, in undertaking his assessment of whether the relevant Jazz Corner marks were deceptively similar to the Swancom marks, the primary judge erred in the other respects canvassed in Swancom’s submissions.

95 A major theme in those submissions is that, in undertaking his assessment, the primary judge distracted himself by focussing on the perception of consumers of hotel and hospitality services, when the infringement claim related to services in respect of which the Swancom marks were registered (relevantly, live music services).

96 We do not accept that submission. First, as we have noted, the primary judge’s starting point was his finding that JCHPL had used the Jazz Corner Hotel and Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks, and that BBPL had used the Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks, in relation to live music services: J[244]. This provided the framework for his Honour’s subsequent analysis—trade mark use in respect of live music services.

97 Secondly, we do not accept that his Honour erred by having regard to the meaning of “corner hotel” as perceived by consumers of hotel and hospitality services. His Honour had earlier rejected Swancom’s contention that the words “corner hotel” have no signification in respect of live music services: J[154]. At J[247], his Honour returned to that finding, stating that the meaning he had found had some signification for persons who wish to attend a live music performance. This indicates that his Honour did not stray from the framework he had set.

98 Thirdly, at J[253], the primary judge stated that, in assessing deceptive similarity, he had accepted the respondents’ submission that consumers of live music services can be expected to be discerning with their choices. In that regard, his Honour said:

253 … Not only will consumers want to see the music they like, they can be expected to be knowledgeable and discerning about the venues they wish to attend to see live music performance. …

99 Once again, this indicates that his Honour did not stray from the framework he had set.

100 Swancom’s submission that the primary judge failed to take into account that there was no other live music venue trading under the names THE CORNER or CORNER HOTEL is an iteration of its principal submission that the “acquired distinctive meaning” of a registered trade mark informs the assessment of deceptive similarity in the context of trade mark infringement—a submission we have rejected.

101 Swancom’s submission that the primary judge erred by failing to consider that the Jazz Corner Hotel marks incorporate the whole of the distinctive mark CORNER HOTEL, cannot be accepted. It flies in the face of the primary judge’s acceptance at J[245] that all the Swancom marks and Jazz Corner marks have the word “corner” in common and, specifically, that the CORNER HOTEL and the Jazz Corner Hotel marks have two words in common.

102 The balance of Swancom’s submissions on Grounds 1 to 4 really invite us to carry out afresh the evaluative task that the primary judge had carried out, with a view to us arriving at a different finding to supplant his Honour’s finding. That is not an invitation we accept. We are not persuaded that the primary judge erred in carrying out his evaluative task.

103 The primary judge’s ultimate findings that the relevant Jazz Corner marks were not deceptively similar to Swancom marks, and that the Swancom marks were not infringed, were open to his Honour. There is no proper basis to interfere with those findings. Grounds 1 to 4 of the first appeal have not been established.

Grounds 5 and 6

104 By Grounds 5 and 6 of the notice of appeal, Swancom challenges the primary judge’s finding at J[221] that the respondents had not used THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD as a trade mark.

105 Swancom submits that it is difficult to reconcile the primary judge’s finding at J[219] that the Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks were used as a trade mark with his finding that the respondents had not used THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD as a trade mark, in circumstances where Swancom contends both were used as marks by the respondents in a similar manner and fashion.

106 At J[183] to [186] the primary judge set out the relevant principles with respect to determining whether use of a sign constitutes trade mark use for the purposes of the Act, highlighting the applicable legal principles summarised by Reeves J in Mantra Group Pty Ltd v Tailly Pty Ltd (No 2) (2010) 183 FCR 450 at [50]. Neither party challenges the correctness of that summary.

107 Swancom acknowledges that the Court is required to examine the purpose and nature of the use in its context. Relevant factors include the positioning of the sign, the type of font used, the size of the words or letters, and the colours which are used, as well as how the sign is applied to advertising.

108 Swancom submits that the respondents’ purpose in using the THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD was to convey an impression to consumers of a connection with the New York jazz institution, Birdland Jazz Club. This, it says, is “classic trade mark use”.

109 At J[220], the primary judge found that THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD had been used in a more limited manner than the Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks, predominantly in connection with Bird’s Basement. The primary judge was not persuaded that the respondents’ use of THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD was use as a badge of origin, even though those familiar with the Birdland Jazz Club in New York and its own use of that phrase might have thought that the respondents’ use conveyed some form of association between Bird’s Basement and the New York club.

110 At J[220], the primary judge noted:

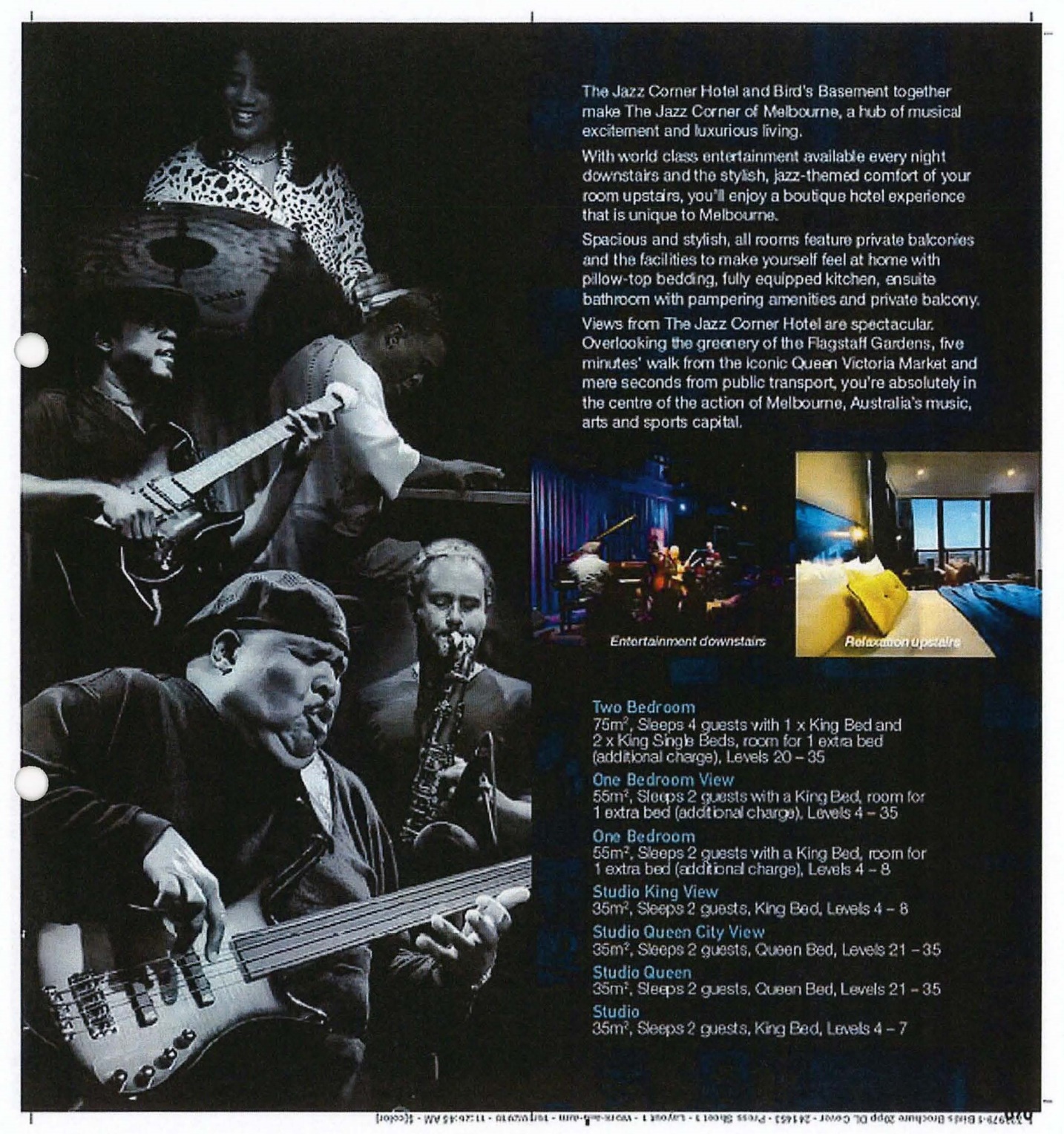

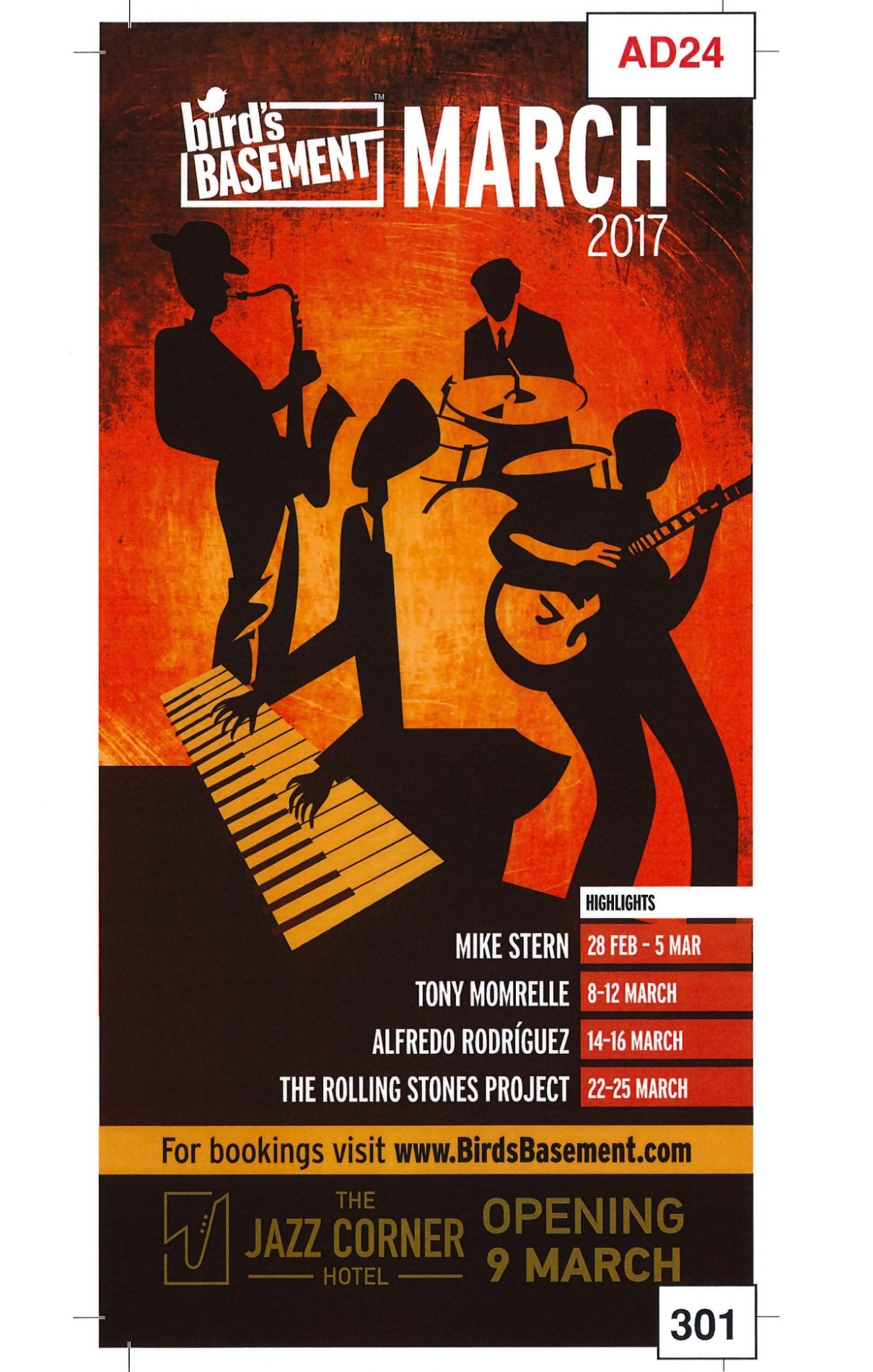

220 The most prominent use is on signage outside the William Street building that associates Bird’s Basement with the phrase “Jazz Corner of the World”. Two of the signs state, next to the Bird’s Basement device mark, that “The Jazz Corner of the World now extends to Melbourne”. A monthly brochure issued by BBPL in March 2017, to promote the opening of The Jazz Corner Hotel in that month, contained the statement: “Bird’s Basement is the Jazz Corner of the World, welcome to the Jazz Corner Hotel”.

111 Annexure A1 to these reasons is the brochure use.

112 At J[221], his Honour accepted the respondents’ submission that the uses he identified at J[220] were merely descriptive uses.

113 The assessment of whether a sign is used as a trade mark is an evaluative exercise on which reasonable minds might differ. In our view, the primary judge’s finding that the respondents’ use of THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD did not extend beyond a descriptive use of that phrase, and was not trade mark use, was one that was open to his Honour to make. We are not persuaded that his Honour erred in carrying out his assessment in this regard.

114 We add that neither the respondents’ desire to be associated with the history and world-renowned reputation of the Birdland Jazz Club, nor the fact that some consumers of the respondents’ services were familiar with the Birdland Jazz Club, compelled his Honour to come to different findings. Similarly, his Honour’s acceptance that, on balance, the respondents had used the Jazz Corner of Melbourne marks in relation to all the businesses conducted from the William Street building, including the jazz club, did not compel his Honour to come to the same conclusion with respect to the respondents’ use of THE JAZZ CORNER OF THE WORLD.

115 Grounds 5 and 6 of the first appeal are not established.

116 For completeness, we record that, had we found that Grounds 5 and 6 of the first appeal were established, we would not have been persuaded that the Jazz Corner of the World marks are deceptively similar to the Swancom marks.

Ground 7

117 By Ground 7 of the notice of appeal, Swancom challenges the primary judge’s finding at J[215] that BBPL had not used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services.

118 Swancom submits that it is difficult to reconcile the primary judge’s finding at J[208] – [209] that JCHPL had used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks, and his findings as to the unified nature of the businesses within the Jazz Corner Hotel at J[210] and [212], with his findings at J[215] that BBPL had not used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services.

119 Swancom took the Court to some examples of what it submits was use of the Jazz Corner Hotel mark by BBPL. These comprise Annexures A2 to A4 to the reasons.

120 The primary judge observed at J[201] that, while each of JCHPL, BBPL and STPL conducted separate businesses, they had common ownership, were located in the same building, and engaged in substantial cross-promotion of each other’s businesses.

121 The primary judge considered that, on balance, JCHPL had used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks on the Jazz Corner Hotel website, social media accounts, and travel websites to distinguish live music performances in the basement jazz club in the sense of indicating origin. At J[209]–[211] his Honour discussed three factors that he considered to be significant in coming to this finding.

122 First, at J[209] his Honour noted that the Jazz Corner Hotel website and other promotional material promoted other services provided in the same building in a manner which suggested that they were complementary services offered by the hotel and provided under the head brand “Jazz Corner Hotel”.

123 Secondly, at J[210] his Honour referred to the significance of the physical location of Bird’s Basement jazz club in the basement of the William Street building in which the hotel is located. In his Honour’s assessment, this served to indicate that the jazz club was part of a unified business within the Jazz Corner Hotel.

124 Thirdly, at J[211] his Honour considered that there was nothing unusual in a hotel also operating a café and jazz club.

125 At J[212], the primary judge stated:

212 It can be accepted that JCHPL’s cross-promotion of live music performances in the basement jazz club is almost always done by using the Bird’s Basement trade mark as a badge of origin of live music services. In my view, though, the use of the Bird’s Basement trade mark does not diminish the significance of the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a badge of origin. Rather, the Bird’s Basement mark would be perceived to be a sub-mark or secondary-mark of the live music services. The promotional material conveys that The Jazz Corner Hotel is a unified business that has accommodation, a café and a jazz club, with the café trading under the name The Jazz Corner Café and the jazz club trading under the name Bird’s Basement.

126 However, the primary judge considered BBPL’s use of THE JAZZ CORNER HOTEL to be different. At J[215], the primary judge said:

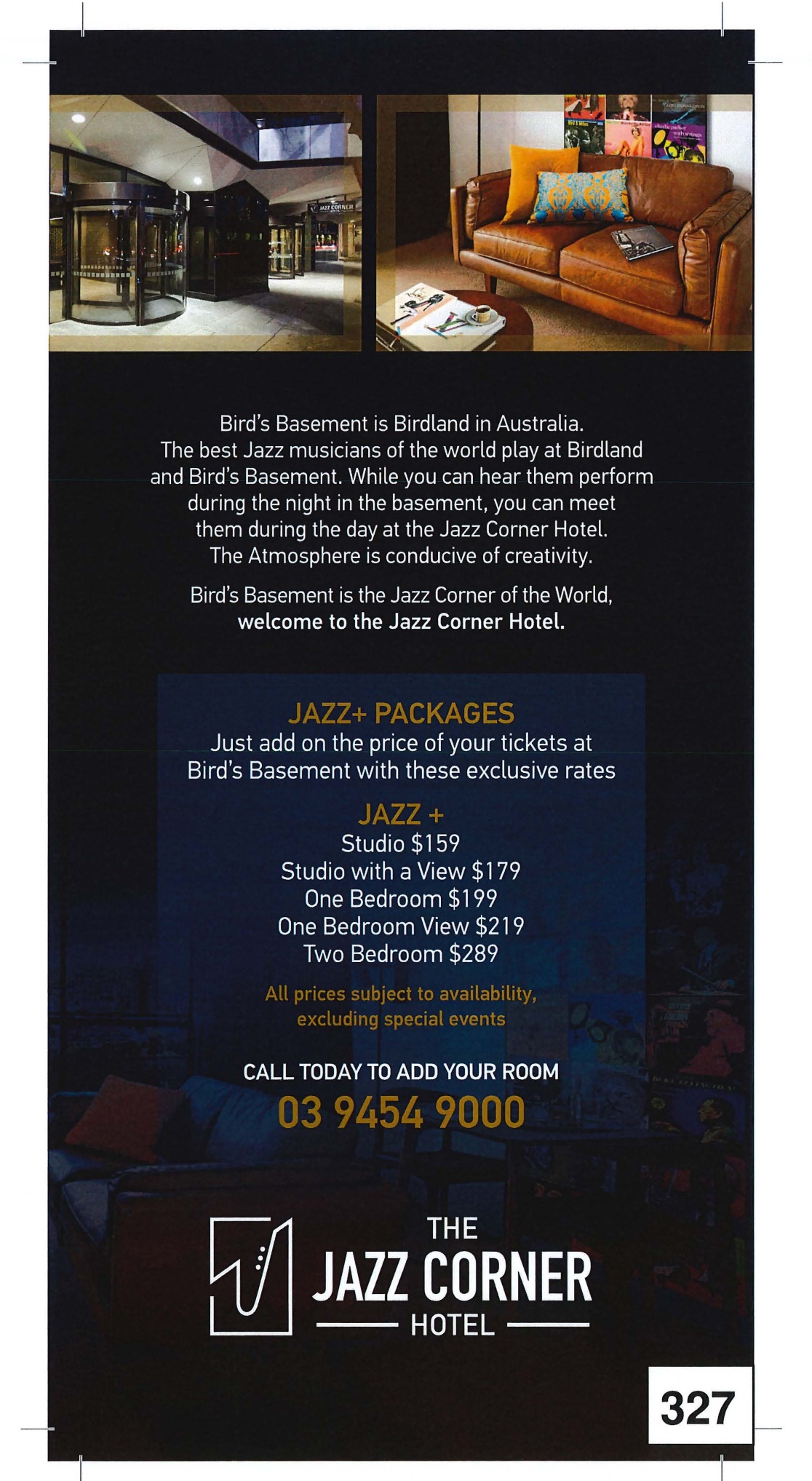

215 … The Bird’s Basement website contains a cross-promotion of accommodation at The Jazz Corner Hotel. It also contains the promotional statement “Stay with us at the Jazz Corner Hotel”. The use of the possessive pronoun again indicates that there is common ownership between the businesses. However, on the website, the Bird’s Basement mark is clearly identified as the badge of origin of the live music services, while the Jazz Corner Hotel marks are identified as a bade of origin of accommodation services. In contrast to the by JCHPL, BBPL does not use the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a primary or “umbrella” mark to indicate a source of origin for all of the services provided at the William Street building. The same can be said for the marketing brochures published by BBPL. While the brochures cross-promote The Jazz Corner Hotel, they do not use the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a badge of origin in respect of live music services. Rather, the brochures depict the Registered Jazz Corner Hotel device mark with the by-line “relaxation upstairs” and the Bird’s Basement device mark with by-line “entertainment downstairs”, indicating that each is the badge of origin for accommodation and live music services respectively.

127 We acknowledge, once again, that the assessment of whether a sign is used as a trade mark is an evaluative exercise on which reasonable minds might differ. The primary judge’s analysis of the differing uses of the Jazz Corner Hotel marks by JCHPL on the one hand, and by BBPL on the other, was nuanced. However, we do not discern error in his Honour’s approach or conclusions. Therefore, Ground 7 of the appeal is not established.

128 We add that, even if it be accepted that BBPL had used the Jazz Corner Hotel marks as a trade mark in relation to live music services, this would not lead to a finding of infringement, given the primary judge’s finding that the Jazz Corner Hotel marks are not deceptively similar to the Swancom marks—a finding we have upheld.

Notice of Contention

129 As we have noted, the respondents’ notice of contention raises two grounds: first, the primary judge should have found that JCHPL had not used the phrase (THE) JAZZ CORNER HOTEL as a trade mark; and (b) the primary judge should have found that JCHPL and BBPL had not used the phrase (THE) JAZZ CORNER OF MELBOURNE as a trade mark.

130 Given our conclusion on Grounds 1 to 4 of this appeal, it is not necessary for us to consider the respondent’s notice of contention. The notice of contention invites us to interfere with the primary judge’s evaluative findings on trade mark use in a way that can have no effect on the outcome of the first appeal.

The Second Appeal

131 In the second appeal, JCHPL challenges the costs orders made in respect to its cross-claim, contending that the primary judge’s decision was erroneous in that his Honour ought to have ordered that Swancom pay JCHPL’s costs of the proceeding as JCHPL was the successful party. As previously noted, this appeal should be dismissed.

Grounds 1 to 4

132 By Grounds 1–3, JCHPL advances three bases for challenging the primary judge’s reasons in the Costs Decision, which it submits, by Ground 4, results in the conclusion that his Honour erred in failing to order that Swancom pay it costs of the cross-claim. In summary, the three bases advanced are as follows. First, that the primary judge erred in breaking up the costs order into components, and in particular, in treating the costs of the cross-claim in a different manner to the other defences raised by the respondent. Secondly, that the primary judge erred in failing to take account of the partial result obtained by JCHPL in the cross-claim which arose from its evidence on historical and industry usage. Thirdly, that the primary judge erroneously concluded at CD[26] that the scope for the dispute as to the categorisation of costs incurred as relating to the application or the cross-claim, was relatively narrow.

133 Section 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) confers jurisdiction on the Court to award costs. The award involves the exercise of a discretionary judgment: Foots v Southern Cross Mine Management Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 56; (2007) 234 CLR 52 at [25]. The disposition to be made in any case where there are competing considerations will reflect a broad evaluative judgment of what justice requires: Gray v Richards (No 2) [2014] HCA 47; (2014) 89 ALJR 113 at [2]. That said, ordinarily, a successful party is entitled to an award of costs in its favour in the absence of special circumstances justifying some other order: see Ruddock v Vadarlis (No 2) [2001] FCA 1865; (2001) 115 FCR 229 at [11]; Oshlack v Richmond River Council [1998] HCA 11; (1998) 193 CLR 72 at [67], [134]; Victoria v Sportsbet Pty Ltd (No 2) [2012] FCAFC 174 at [6]–[7]. As the primary judge uncontroversially observed at CD[20], although usually the discretion is exercised in favour of a successful party, “a successful party may be deprived of a proportion of its costs, or even required to pay costs to the other party, if the successful party succeeded only upon a portion of its claim, or failed on issues that were not reasonably pursued, or where the result of the litigation might be described as mixed”. The primary judge also recognised that “the mere fact that a court does not accept all of a successful party’s arguments does not make it appropriate to apportion costs on an issue by issue basis”. JCHPL does not take issue with the correctness of those principles.

134 It is trite to observe that in an appeal from a discretionary judgment, it is not sufficient that an appellate court considers that it would have taken a different course if it had been in the position of the primary judge. Rather, it is necessary to establish that the discretion miscarried through an error of principle of the kind discussed in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499 at 504–5. The grounds on which JCHPL challenges the orders do not suggest that the primary judge acted on wrong principle, took into account irrelevant material, or did not take into account relevant material. JCHPL’s submissions, properly considered, reflect there to be a disagreement with the assessment of the factual conclusions underpinning the costs orders made.

135 As a preliminary observation, the submissions advanced by JCHPL are the same as those advanced below. In practical terms, JCHPL does not point to any error in the primary judge’s reasoning process, but rather repeats the submission rejected below. Related to that, the primary judge’s reasons reflect a detailed and considered analysis of the submissions.

136 In that context, the primary judge recited the arguments advanced at CD[13]–[19], and the relevant principles, at CD[20]. Having done so, the primary judge first addressed the question of the costs on Swancom’s application and determined that JCHPL was entitled to its costs, it having succeeded in defending the application: at CD[21]. Relevantly, the primary judge turned to the cross-claim and at CD[22] stated:

In relation to the cross-claim brought by JCHPL, I accept Swancom’s submission that it should be regarded as, overall, the successful party on the cross-claim. As JCHPL submitted, the cross claim was brought as a defence to the infringement claim. While JCHPL established that the designated services in respect of which the CORNER and THE CORNER marks are registered in class 41 require amendment, the amendment did not afford any defence to the infringement claim. JCHPL failed in its application for cancellation of Swancom’s registered trade marks. Swancom’s defence of the cross-claim required the filing of substantial evidence concerning its business and the use of its registered trade marks, including industry and expert evidence. In the circumstances, Swancom would ordinarily be entitled to its costs of the cross-claim.

137 At CD[23], the primary judge concluded that the outcome of the proceeding suggests that the (then) respondents should have their costs of the application and Swancom should have its costs of the cross-claim. Reference was made to the relevant Practice Note. At CD[24], the primary judge addressed a submission by Swancom, based on Hansen Beverage Company v Bickfords (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2008] FCA 601, that it was fair to all parties to offset their costs entitlements and make no order as to costs. The primary judge rejected the application of the approach in Hansen on the basis that there was insufficient material before him. At CD[25], the primary judge expressed his conclusion that the appropriate orders were for Swancom to pay the respondents’ costs of the application and for JCHPL to pay Swancom’s costs of the cross-claim.

138 Relevantly at CD[26], the primary judge stated:

In making those orders, I recognise that there is some potential for dispute as to the categorisation of costs incurred as relating to the application or the cross-claim. However, I consider that the scope for such dispute to be relatively narrow. Swancom’s application claiming trade mark infringement did not require it to establish any reputation in its marks. It follows that the evidence adduced by Swancom in relation to its business, reputation and trade mark use principally related to the cross-claim and Swancom should be entitled to its costs of that evidence as part of its costs of the cross-claim. Conversely, the evidence adduced by the respondents in relation to their businesses and trade mark use principally related to the application and the respondents should be entitled to their costs of that evidence as part of their costs of the application. As to the evidence adduced by JCHPL concerning the use of the word “corner” as a trading name, such evidence was relevant to both the application and the cross claim. In circumstances where Swancom initiated the proceeding and the respondents were brought to Court to defend the claim, in my view the respondents are entitled to be awarded their costs of that evidence as part of their costs of the application. That will include the costs associated with the proof of facts stated in the Notice to Admit that were not admitted by Swancom and which were ultimately found by the Court (at [66] of the principal judgment).

139 Against that background, we turn to the three bases of challenge.