Federal Court of Australia

State of Escape Accessories Pty Limited v Schwartz [2022] FCAFC 63

ORDERS

STATE OF ESCAPE ACCESSORIES PTY LIMITED (ACN 163 053 665) Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent CHUCHKA PTY LTD (ACN 613 133 850) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal on a lump sum basis in a sum to be agreed or, in default of agreement, to be assessed by a Registrar of the Court.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 This is an appeal from the judgment of the primary judge in State of Escape Accessories Pty Limited v Schwartz [2020] FCA 1606 (Reasons) rejecting the appellant’s claim against the respondents for copyright infringement in respect of a perforated neoprene tote bag or carry-all bag (Escape Bag) on the basis that it was not a “work of artistic craftsmanship” within the meaning of s 10(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act). The appellant contends that the primary judge fell into error in holding that the Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship.

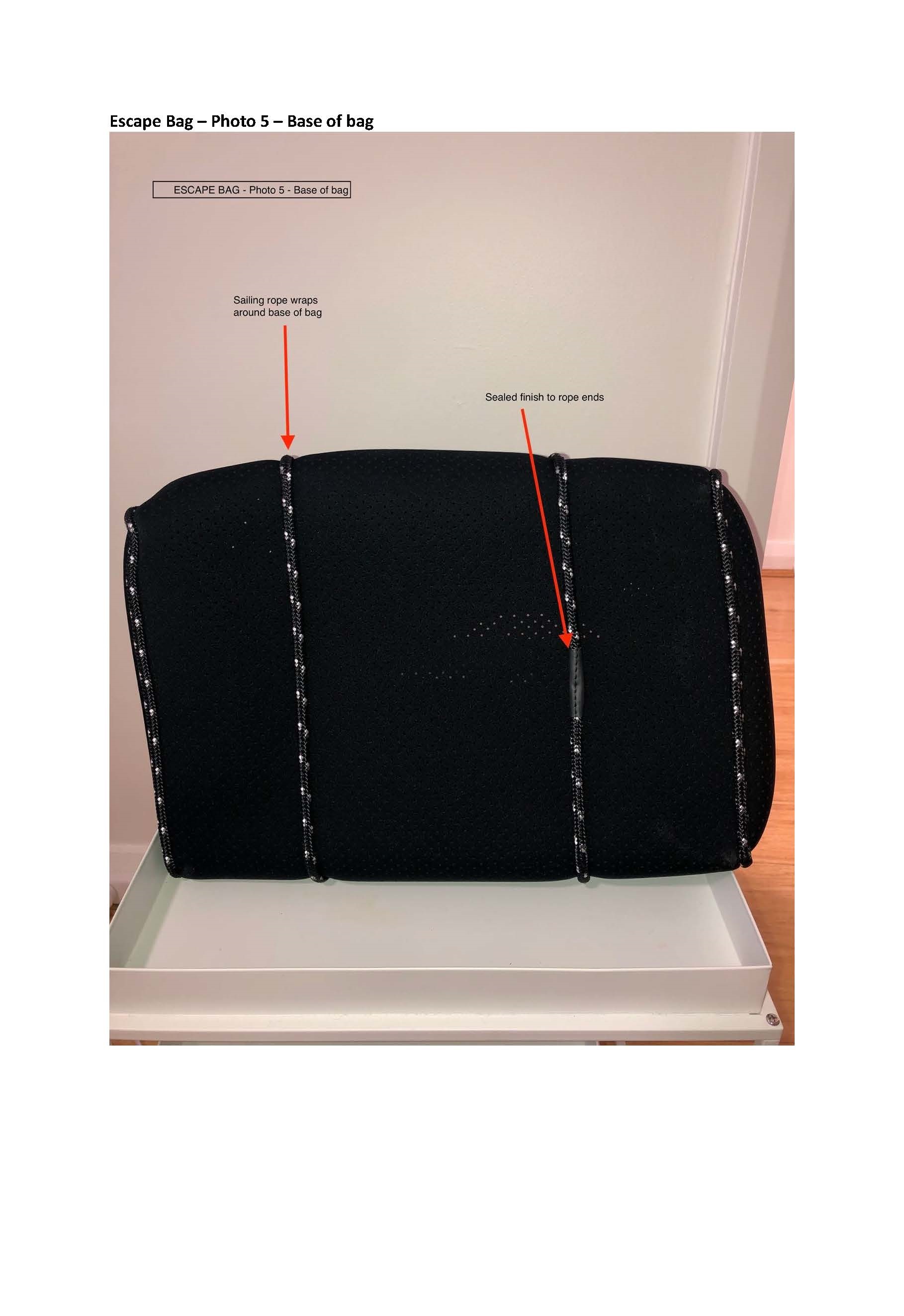

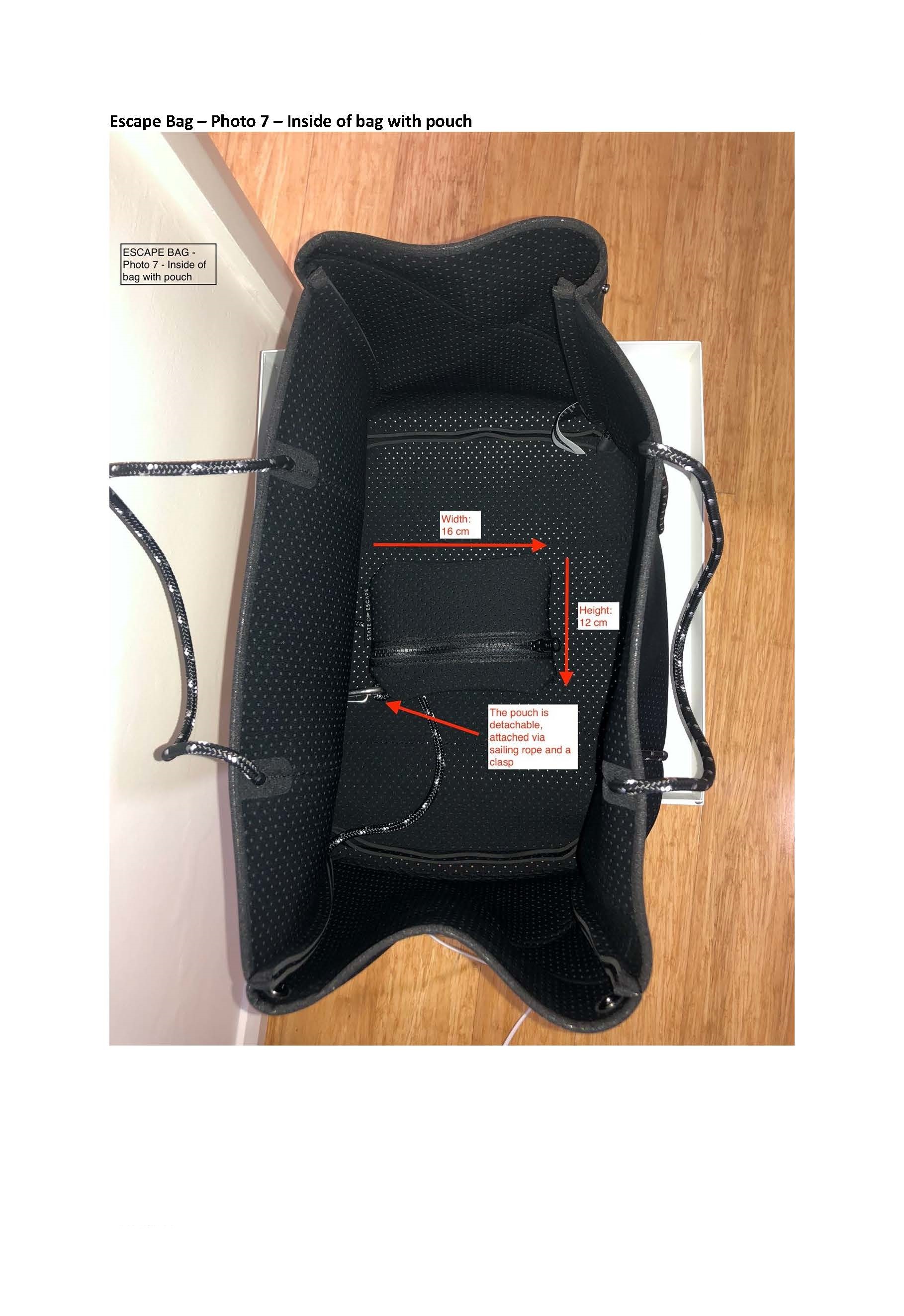

2 Photographs of the Escape Bag are reproduced in Annexure A to these reasons for judgment.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

3 Artistic works are a species of work protected under the provisions of Part III of the Copyright Act. It was not suggested by the appellant that copyright could subsist in the Escape Bag otherwise than as a “work of artistic craftsmanship” under para (c) of the definition of “artistic work”.

4 Section 10(1) of the Copyright Act defines an “artistic work” as:

(a) a painting, sculpture, drawing, engraving or photograph, whether the work is of artistic quality or not;

(b) a building or a model of a building, whether the building or model is of artistic quality or not; or

(c) a work of artistic craftsmanship whether or not mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b);

…

The words “whether or not mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b)” were added to (c) of the definition by amendments made by the Designs (Consequential Amendments) Act 2003 (Cth).

5 Section 5 of the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (“Designs Act”) defines “design” to mean “in relation to a product … the overall appearance of the product resulting from one or more visual features of the product”. A “visual feature” of a product includes the shape, configuration, pattern and ornamentation of the product (Designs Act s 7).

6 Many products are three-dimensional reproductions of a prototype of a product or a drawing of the product. These prototypes and drawings may be artistic works as defined by s 10(1) of the Copyright Act. Subject to the “overlap” provisions of the Copyright Act, these works may be protectable as artistic works under the Copyright Act or as registered designs under the Designs Act. However, an artistic work cannot be afforded protection under both the Copyright Act and the Designs Act simultaneously. The overlap provisions operate to remove copyright protection for an artistic work where a “corresponding design” has been “embodied in a product” and applied “industrially”. Regulation 12 of the Copyright Regulations 2017 (Cth) provides that a design is taken to be “applied industrially” if it is (inter alia) applied to more than 50 articles.

7 Section 75 of the Copyright Act provides a defence to copyright infringement in an artistic work where a corresponding design is, or has been, registered as a design. A person will not infringe copyright that subsists in an artistic work by reproducing the work in three-dimensional form when applying a corresponding design to a product. Section 77 of the Copyright Act also provides a defence to copyright infringement in an artistic work where a corresponding design is applied industrially and the design is not registered or is not registrable under the Designs Act.

8 However, these defences do not operate where the artistic work is a work of “artistic craftsmanship”. A work of artistic craftsmanship may still be afforded copyright protection, even if it is capable of protection by registration under the Designs Act, and even if a corresponding design has been industrially applied. Protection under the Designs Act lasts for up to 10 years from the date of application for registration of a design (Designs Act s 46). Copyright protection for an artistic work will in most cases last for 70 years after the calendar year in which the author died (Copyright Act s 33). Copyright protection is not dependant on registration.

9 The policy behind the overlap provisions is to ensure that works which are functional and intended for mass production in three dimensional form should not be afforded protection under the Copyright Act. The Revised Explanatory Memorandum to the Designs (Consequential Amendments) Bill 2003 (Cth) states that “[t]he broad policy is that artistic works commercially exploited as three-dimensional designs should generally be denied copyright protection.” The legislative policy is to encourage the use of the registered design system, rather than copyright, for the purpose of protecting artistic works which are applied to industrial products: see Burge v Swarbrick (2007) 232 CLR 336 (Burge) at [10].

10 The reason for the “special status” conferred upon works of “artistic craftsmanship” was referred to by Drummond J in Coogi Australia Pty Ltd v Hysport International Pty Ltd (1998) 86 FCR 154 (Coogi), who suggested at 168:

Real artistic quality that is an essential feature of such works and the desirability of encouraging real artistic effort directed to industrial design is sufficient to warrant the greater protection and the accompanying stifling effect on manufacturing development that long copyright gives, in contrast to relatively short design-protection.

His Honour’s observations were referred to by the High Court in Burge at [50] with apparent approval. Works of artistic craftsmanship are singled out because it was considered by Parliament that they are more appropriately protected under the Copyright Act: Explanatory Memorandum to the Copyright Amendment Bill 1988 (Cth) at [24]; Burge at [42].

PRIMARY JUDGE’S REASONS

11 The primary judge’s reasons include a detailed consideration of the guiding principles to be applied in determining whether or not something is a work of artistic craftsmanship: Reasons [77]-[80]. It is convenient to reproduce her Honour’s summary of the relevant principles appearing at [77]:

The parties were not in dispute on the guiding principles to apply in determining whether the Escape Bag is a “work of artistic craftsmanship”. Those principles were settled by the High Court’s decision in Burge and may be distilled as follows:

(a) the phrase “a work of artistic craftsmanship” is a composite phrase to be construed as a whole: Burge at 357 [56], 360 [66]. It is not permissible to inquire separately into whether a work is: (a) artistic; and (b) the manifestation of craftsmanship;

(b) in order to qualify as a work of artistic craftsmanship under the Copyright Act, the work must have a “real or substantial artistic element”: Burge at 356 [52];

(c) “artistic craftsmanship” does not mean “artistic handicraft”: Burge at 358 [59];

(d) a prototype may be a work of artistic craftsmanship “even though it was to serve the purpose of reproduction and then be discarded”: Burge at 359 [60];

(e) the requirements for “craftsmanship” and “artistic” are not incompatible with machine production: Burge at 358–9 [59]–[60];

(f) whilst there is a distinction between fine arts and useful or applied arts, when dealing with artistic craftsmanship there is no antithesis between utility and beauty or between function and art: Burge at 359 [61];

(g) a work of craftsmanship, even though it cannot be confined to handicraft, “at least presupposes special training, skill and knowledge for its production… ‘Craftsmanship’… implies a manifestation of pride and sound workmanship – a rejection of the shoddy, the meretricious, the facile”: Burge at 359 [61], citing George Hensher Ltd v Restawile Upholstery (Lancs) Ltd [1976] AC 64 (Hensher) at 91 per Lord Simon;

(h) although the matter is to be determined objectively, evidence from the creator of the work of his or her aspirations or intentions when designing and constructing the work is admissible, but it is neither determinative nor necessary: Burge at 360 [63]–[65]. In determining whether the creator intended to, and did, create a work possessing the requisite aesthetic quality and requisite degree of craftsmanship, the Court should weigh the creator’s evidence together with any expert evidence: Burge at 360 [64] and [65]; and

(i) in considering whether a work is one of “artistic craftsmanship”, the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the work is not determinative. The Court must also weigh in the balance the extent to which functional considerations have dictated the artistic expression in the form of the work: Burge at 364 [83]–[84].

Her Honour also later referred to the High Court’s preference for the views of Lord Simon in George Hensher Ltd v Restawhile Upholstery (Lancs) Ltd [1976] AC 64 (Hensher) and said at [80]:

The High Court adopted the approach of Lord Simon in Hensher. In issue in Hensher was whether a prototype chair of “a commercially bold and original design, though not calculated to appeal to fastidious taste” was a work of artistic craftsmanship within the meaning of the Copyright Act 1956 (UK). Lord Simon agreed with the Court of Appeal that mere originality in points of design aimed at appealing to the eye as commercial selling points was not sufficient to make the work a work of artistic craftsmanship. As Lord Simon explained, the issue was whether the work was a work of artistic craftsmanship, not an artistic work of craftsmanship. In passages cited by the High Court in Burge at 359 [61], Lord Simon said at 91:

A work of craftsmanship, even though it cannot be confined to handicraft, at least presupposes special training, skill and knowledge for its production… “Craftsmanship”, particularly when considered in its historical context, implies a manifestation of pride in sound workmanship—a rejection of the shoddy, the meretricious, the facile.

And at 93:

Even more important, the whole antithesis between utility and beauty, between function and art, is a false one—especially in the context of the Arts and Crafts movement. “I never begin to be satisfied,” said Philip Webb, one of the founders, “until my work looks commonplace.” Lethaby’s object, declared towards the end, was “to create an efficiency style.” Artistic form should, they all held, be an emanation of regard for materials on the one hand and for function on the other.

Lord Simon concluded that the chairs were “perfectly ordinary pieces of furniture”. Lord Simon considered it would be “an entire misuse of language to describe them or their prototypes as works of artistic craftsmanship”, stating that the “novelty” and “distinct individuality” of the chairs “at the most… established originality in points of design aimed at appealing to the eye as commercial selling points” but did not make the chair or its prototype a work of artistic craftsmanship.

12 It was not suggested by the appellants that her Honour’s analysis of the relevant legal principles was affected by any error. Rather, the appellant criticises her Honour’s evaluation of the evidence. For that reason it is necessary to refer to her Honour’s discussion of the evidence in some detail.

13 The Escape Bag is a soft, oversized tote bag designed and created by Ms Brigitte MacGowan, a co-founder and director of the appellant. Ms MacGowan’s evidence, which was largely unchallenged, was outlined by the primary judge at Reasons [24]-[46].

14 Ms MacGowan’s evidence was that each element in creating the Escape Bag involved a design choice in pursuit of Ms MacGowan’s quest for “simplicity, beauty and originality” and that “[e]verything in the design had to be there for a reason: Reasons [28], [30] and [81]. According to Ms MacGowan, her purpose was “really about creating an impression of the whole rather than the individual parts”: Reasons [30] and [31].

15 Ms MacGowan gave evidence that she regarded the fundamental elements of the Escape Bag to be (a) perforated neoprene; (b) sailing rope (or rope of that appearance); and (c) the shape and product dimensions “resulting in its distinctive silhouette”: Reasons [7] and [83]. She said that “the overall appearance of the bag as an object was fundamentally the most important thing”, that she “[felt] deeply passionate about what [she] created”, and that it was “a labour of love [and her] ultimate design challenge”. In Ms MacGowan’s view, she created something that “had never been seen before”: Reasons [84] and [86].

16 The primary judge accepted Ms MacGowan’s evidence about her aspirations and intentions in designing the Escape Bag: Reasons [109].

17 The appellant’s expert, Ms Claire Beale, and the respondents’ expert, Mr Andrew Smith, agreed that the Escape Bag displays a quality of workmanship. They also agreed that the neoprene fabric used in combination with the rope handles represented a departure from other bags known as at November 2013: Reasons [87].

18 Ms Beale referred to the Escape Bag as “unique” while Mr Smith was of the view that “combining two or more features that had been in common use over many years [was] an evolution in style rather than a completely new design”. Ms Beale accepted that the uniqueness to which she referred arises from the choice or “design decision” to use perforated neoprene and sailing rope, rather than in any contribution to the creation of those underlying materials: Reasons [87].

19 The primary judge undertook a comprehensive analysis of the expert evidence of Ms Beale and Mr Smith before concluding that, whilst the Escape Bag is a work of craftsmanship, it is not a work of artistic craftsmanship notwithstanding its aesthetic and design qualities.

20 The primary judge’s reasons why the Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship are set out at Reasons [108]-[123] which include the following:

108 Applying the principles set out in Burge leads to the conclusion that the Escape Bag is not a work of artistic craftsmanship. It is undoubtedly a work of craftsmanship but I am not persuaded that it is a work of artistic craftsmanship, notwithstanding its aesthetic and design qualities.

109. I accept Ms MacGowan’s evidence about her aspirations and intention in designing the Escape Bag, but whether the Escape Bag can be characterised as a work of artistic craftsmanship does not turn on her evidence: Burge at 360 [64]. I also accept Ms Beale’s evidence about the aesthetic qualities of the Escape Bag from a design perspective. However, characterisation of the Escape Bag as a work of artistic craftsmanship does not turn on assessing the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the work or on assessing any harmony between its visual appeal and its utility: Burge at 364 [83]. Nor is the test whether the Escape Bag has features that make it distinctive. Some of the evidence of the experts and the submissions for State of Escape tended to that approach, but distinctiveness is not a necessary corollary of artistic craftsmanship. Determining whether the bag is a work of artistic craftsmanship turns on the extent to which the Escape Bag’s artistic expression, in its form, was unconstrained by functional considerations: Burge at 364 [83]. In that assessment, whether the Escape Bag is a work of artistic craftsmanship must be considered objectively, looking at the bag as a whole, not by disintegrating the design choices made by Ms MacGowan within the functional limitations of the bag she created.

110. Ms MacGowan’s design approach was constrained by functional considerations. Ms MacGowan set out to create a stylish carry all bag and, in that endeavour, the function and utility of the bag as a carry all bag governed the overall design of the bag. As the experts agreed, the overall design of the bag incorporates the elements of conventional tote or carry all bags in terms of its dimensions and external shape and conforms to what is generally expected of this style of bag. As Ms MacGowan herself acknowledged, due to the soft nature of the perforated neoprene fabric the structure of the bag was fundamental to the success of the bag. As Ms MacGowan also said in evidence, she wanted the bag to be “useful” and “practical”.

111. Mr Smith said of the tote bag/carry all bag:

… the basic construction of tote bags and carry-all bags is largely standardised, and has been for many years. In both cases, the construction of those bags reflects the function they perform.

Both tote bags and carry-all bags permit users to conveniently and securely transport everyday items. Accordingly, a functional element of such bags is that they have a durable base and sides, with an opening at the top...

Another functional element of tote bags and carry-all bags is that they should have comfortable handles positioned in a way that supports that structure of the bag and helps it to retain its form when in use…

The size of the handles on these bags can also have a functional element. For example, a tote bag with very short handles would be awkward to carry over the shoulder...

Material selection also has a functional element... A more realistic example arises in connection with synthetic fabrics, which have a tendency to fray. Where such fabrics are used, the (functional) need to avoid the fabric fraying may dictate some choices, which appear to be design or style choices - for example, the need to bind the edges of the fabric to prevent fraying.

Another aspect of design, which I consider to have a functional aspect is the inclusion of pockets and/or removable pouches. While the inclusion of pockets and removable pouches are clearly a design choice, they also serve an obviously functional purpose. In my experience, it would be unusual to see a tote bag which did not incorporate either pockets or a removable pouch so that the user has a convenient and secure place to (for example) store valuable or regularly accessed items…

112. The choice of sailing rope for the handles, the arrangement of the handles (running down the exterior of the front and back, under the base and passing though the body of the bag near the top), the use of sailing rope around the gusset of the bag to reinforce and protect the corners and to help maintain the overall shape of the bag, and use of binding around the upper lip of the bag to stop the neoprene fraying were not merely matters of visual and aesthetic appeal but also, critically, resolved functional issues in the design of the bag. Ms MacGowan’s own evidence was that sailing rope is “hard wearing and non-stretch” and these properties enabled her to use it to “create a framework that when sewn around the entire girth of the bag allowed [her] to carry heavy loads without compromising the fabric”. Ms MacGowan also said that she chose sailing rope “for its structural quality, which was something that was also very, very important. It’s a beautiful quality rope, unlike a lot of decorative ropes that you see off the shelf, in our industry”.

113. In cross-examination, Ms MacGowan accepted that the handles of the Escape Bag serve an important functional purpose – namely, they enable a person to carry the bag either over the shoulder or in their hand. Mr Smith considered the arrangement of the handles to have a functional aspect …

114. Ms MacGowan also accepted during cross-examination that the particular arrangement of ropes had a functional purpose …

115. Ms MacGowan also agreed that the rope running along the outer edges of the Escape Bag served a functional purpose, namely, to protect vulnerable areas of the bag, in an approach akin to the use of piping on other handbags.

…

118. Moreover, as the experts also agreed, the functional issues were overcome using methods that were common practice and that none of these features alone represented a departure from bags known as at November 2013.

119. The experts also agreed that:

(a) the use of press studs in gussets to pinch the ends is a common practice;

(b) the incorporation of a detachable pouch into a carry all bag was not unusual;

(c) the Escape Bag is constructed using a standard construction method; and

(d) no significant skill, knowledge or training was required to design or construct the Escape Bag beyond what is expected by [sic] a person who makes and designs such bags.

120. The choice of the perforated neoprene as the fabric for the carry all bag was unconstrained by the function and utility of the Escape Bag and I accept that the selection of that fabric was governed by considerations of appearance and aesthetics. However, once the fabric had been selected, the design choices embodied within the bag were constrained by functional considerations.

121. I also accept the submission for the respondents that Ms MacGowan did not approach the design and manufacture of the Escape Bag as an artist-craftsperson. She had no special training, skill and knowledge relating to the design and manufacture of handbags and many of the issues she encountered were purely functional in nature – for example, preventing the raw edges of neoprene from fraying, reinforcing the point where the rope handle enters the bag, and how to sew the sailing rope onto the bag while retaining the roundness of the rope.

122. Further, I do not regard the selection and use of perforated neoprene as the fabric for the Escape Bag or its use in combination with sailing rope as involving an act of artistic craftsmanship. Both materials were readily available commercial materials capable of being used to manufacture a carry all bag without some particular training, skill or knowledge. At its highest, the use of those materials to make an everyday bag was an evolution in styling. Whilst Ms Beale was of the view the combination of those materials made the Escape Bag “unique” she accepted in cross-examination that the uniqueness to which she referred related to “design decision” to use those materials, rather than in any contribution to the creation of those materials.

123. Accordingly, I find that the Escape Bag is not a work of artistic craftsmanship and that copyright does not subsist in the Escape Bag.

21 Her Honour went on to consider various other issues that are not relevant to the appeal.

GROUNDS OF APPEAL

22 The appellant relied upon the following 10 grounds of appeal:

1. Having correctly found that the Escape Bag was “undoubtedly a work of craftsmanship” (at [108]), the primary judge erred in finding that the Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship and that copyright did not subsist in the Escape Bag (at [108], [123]).

2. Having correctly accepted the evidence of State of Escape’s expert, Ms Beale, as to the aesthetic qualities of the Escape Bag from a design perspective (at [109]), the primary judge erred in failing to give proper weight to:

(a) the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the Escape Bag;

(b) the artistic effort in designing the Escape Bag;

(c) the artistic quality of the Escape Bag,

in assessing whether the Escape Bag was a work of artistic craftsmanship.

3. Having correctly accepted the evidence of the Escape Bag’s author, Ms MacGowan as to her aspirations and intention in designing the Escape Bag (at [109]), the primary judge erred in failing to give proper weight to:

(a) the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the Escape Bag;

(b) the artistic effort in designing the Escape Bag;

(c) the artistic quality of the Escape Bag,

in assessing whether the Escape Bag was a work of artistic craftsmanship.

4. The primary judge should have found that the Escape Bag was a work which had “a real or substantial artistic element” (Burge v Swarbrick [2007] HCA 17; 232 CLR 336 (Burge) at [52]).

5. The primary judge erred in giving improper weight to the extent to which functional considerations constrained the artistic expression in the form of the Escape Bag (at [110] – [115] and [120]).

6. The primary judge should have found that:

(a) functional considerations did not substantially constrain the artistic expression evident in the form of the Escape Bag; and

(b) the Escape Bag was a work which had “a real or substantial artistic element” (Burge at [52]).

7. The primary judge erred in finding at [112] and [118] that the functional considerations resolved in the design of the Escape Bag involved the use of methods that were common practice.

8. In finding at [118] that none of the features referred to therein “alone represented a departure from bags known as at November 2013”, the primary judge erred in:

(a) failing to consider the entire combination of features which comprise the Escape Bag as a whole;

(b) failing to take into account the combination of features referred to at [118] which form only part of the Escape as a whole.

9. The primary judge erred in finding at [121] that Ms MacGowan did not approach the design and manufacture of the Escape Bag as an artist-craftsperson.

10. The primary judge erred in finding at [122] that the selection and use of perforated neoprene as the fabric for the Escape Bag or its use in combination with sailing rope did not involve an act of artistic craftsmanship.

23 Grounds 1, 2, 3 and 4 challenge the primary judge’s conclusion that the Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship and, therefore, not something in which copyright subsists, essentially on the basis that the primary judge failed to give “proper weight” to the evidence of Ms Beale and Ms MacGowan. Grounds 5 and 6, which are to be read together, similarly contend that the primary judge gave “improper weight” to evidence as to the extent to which functional considerations constrained the design of the Escape Bag.

24 Grounds 7 and 8 are concerned with what are said to be errors in the primary judge’s findings of fact concerning the state of the art in bag design and in the evaluation of the Escape Bag as a combination of features.

25 Grounds 9 and 10 challenge two specific findings made by the primary judge, the first of which concerns Ms MacGowan’s approach to the design of the Escape Bag, and the second of which concerns her choice of materials used in the design.

THE APPELLANT’S SUBMISSIONS

26 The appellant submitted that the primary judge should have found that the visual and aesthetic appeal of the Escape Bag was not subordinated to the achievement of purely functional aspects of the design necessary to produce a bag that was both “beautiful” and “practical”. In this regard the appellant focused on the final sentence in Burge at [73]. It submitted, in effect, that if the design of a product was substantially governed by considerations of appearance and aesthetics, the product is a work of artistic craftsmanship. At the same time the appellant submitted that a product might still be a work of artistic craftsmanship, even though its design was not substantially governed by such considerations.

27 The appellant further submitted that the primary judge gave “improper attention to the fact that the bag has functional components”. Elaborating upon this, the appellant contended that “the artistic quality continues to shine through regardless of some functional constraints” and that the Escape Bag reflects a real or substantial artistic effect.

28 The appellant submitted that in the case of any product, it will reflect a merger of functional and artistic elements and that the Escape Bag was clearly positioned towards the end of the spectrum at which artistic elements dominated or, as it also submitted, where it could not be said that “functional considerations [had] overwhelmed real artistic expression”.

29 The appellant sought to develop those submissions by reference to the evidence including, in particular, the evidence given by Ms MacGowan as to her design aspiration and intentions. The appellant submitted that Ms MacGowan’s evidence, which was largely unchallenged, showed that when creating the Escape Bag her dominant aesthetic considerations were “simplicity, beauty and originality” and that the choice of perforated neoprene with handles made from sailing rope were the result of a design choice made by her.

30 The appellant submitted that Ms MacGowan’s design philosophy, and its realisation in the Escape Bag, distinguish the present case from the products in issue in Burge and in Hensher. The Escape Bag, in the appellant’s submission, was made by hand, adopting techniques which were “non-commercial” and consistent with Ms MacGowan’s desire to keep everything as simple and true to form as possible. The appellant submitted that Ms MacGowan’s approach stands in marked contrast to designs driven by marketing and mass production imperatives of the kind which it said could be seen in Burge and Hensher.

31 The appellant submitted that the primary judge erred in accepting Mr Smith as an expert in handbag design rather than, as the appellant contends, someone whose expertise was in manufacturing bags. The appellant submitted that Mr Smith, unlike Ms Beale, was not qualified, or at least less qualified, than Ms Beale, to opine on the artistic qualities of the Escape Bag.

32 The appellant submitted that the primary judge, having accepted the evidence of Ms Beale as to the aesthetic qualities of the Escape Bag from a design perspective at Reasons [109], should have placed greater weight on her evidence that the Escape Bag, when assessed holistically “… has clever design elements … such that when the press studs are closed, the overall form of the bag took on “a softly curved organic form”…” and that the aesthetic qualities of the Escape Bag were pleasing to the eye, simple, elegant and beautiful.

33 The appellant also submitted that the primary judge erred in finding that the functional issues resolved by Ms MacGowan were overcome using methods that were common practice. The appellant further submitted that the primary judge correctly identified that a work of artistic craftsmanship must be considered objectively by looking at the work as a whole, but that when considering the features of the Escape Bag, the primary judge failed to consider the combination of features which constitute the Escape Bag as a whole.

34 The appellant also submitted that the primary judge erred in finding that Ms MacGowan did not approach the design and manufacture of the Escape Bag as an artist-craftsperson and this conclusion by the primary judge rested on the erroneous finding that “she had no special training, skill and knowledge relating to the design and manufacture of handbags and many of the issues she encountered were purely functional in nature …”. The appellant points to the evidence of Ms Beale which was said to establish that there was an exercise of skill on the part of the designer, Ms MacGowan, in the “end to end creation process of the Escape Bag” and that Ms MacGowan had used technical skills, an informed and observant approach, and a strong understanding of materials. The appellant also pointed to the fact that both experts agreed that the Escape Bag displayed quality of workmanship. The appellant submitted that to require specialist training and knowledge in the design and manufacture of bags would unduly limit the scope for original contribution by a person outside the traditional field.

35 Finally, the appellant submitted that the primary judge erred in finding that the use of neoprene alone or in combination with sailing rope, did not involve an act of artistic craftsmanship because those materials were readily available and could be used without particular training, skill or knowledge. The appellant submitted that in the field of useful or applied arts, it is commonplace to use materials which are readily available but that the primary judge gave insufficient weight to the fact that perforated neoprene was an unusual fabrication and the combination of perforated neoprene and sailing rope involved a design decision which led to the Escape Bag being unique.

36 The appellant also addressed, by way of reply, the functional considerations that did not, in the appellant’s submission, significantly constrain the Escape Bag’s design. In summary, these submissions referred to the overall and external shape of the bag; the use of neoprene fabric; the use of rope for handles; the arrangement of the handles; the rope handles entering the body of the bag near the top lip; the stitching of the rope handles to the bag; the use of rope around the bottom edge of the gusset; the use of a detachable pouch with a rope and clip; the use of heat shrinkable rubber binding around the rope ends and joins; the use of binding around the upper lip of the bag; the use of binding at the point where the rope handles pass through the bag; and internal stitching.

THE RESPONDENTS’ SUBMISSIONS

37 The respondents submitted that the primary judge was correct to find that the appellant’s Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship. The primary judge, in the respondents’ submission, correctly identified that whether the Escape Bag is a work of artistic craftsmanship depended on “… the extent to which the Escape Bag’s artistic expression, in its form, was unconstrained by functional considerations …”.

38 The respondents submitted that the appellant’s criticism that the primary judge placed undue weight on the functional aspects of the Escape Bag was without merit. They submitted that the primary judge correctly assessed the extent to which the design of the Escape Bag was constrained by functional considerations, and that every feature of the design of the Escape Bag relied upon by the appellant had a functional quality. They relied, in particular, upon the findings of the primary judge which appear at Reasons [112] set out above. The respondents submitted that those findings were supported by Ms MacGowan’s own evidence, as well as the evidence of Mr Smith.

39 The respondents submitted that the appellant’s criticisms of the primary judge’s reliance on the fact that some of the methods used in making the Escape Bag were “common practice” and the fact that many features of the Escape Bag were not “departures” from earlier bags are misplaced. They submitted that the appellant does not really challenge these matters as factual findings, but rather asserts that they disclose a failure to assess the Escape Bag as a whole. This criticism, in the respondents’ submission, should be rejected, since the primary judge correctly identified the importance of assessing the Escape Bag objectively and as a whole, and her Honour’s detailed reasons reveal that she did so. Further, the respondents submitted these challenges to the primary judge’s findings are contrary to the evidence, including the joint report of the experts, Ms Beale and Mr Smith which showed that none of the features of the Escape Bag represented a departure from bags known as at November 2013.

40 The respondents submitted that the appellant’s challenges to the primary judge’s finding that Ms MacGowan was not acting as an “artist craftsperson” when she designed and made the Escape Bag should be rejected because the evidence unequivocally established that she had no special training, skill or knowledge in the design and manufacture of handbags. They submitted that the appellant makes no challenge to the factual finding that Ms MacGowan had no special training, skill or knowledge relating to the design and manufacture of handbags and that, as the expert witnesses agreed, there was no significant skill, knowledge or training required to design or construct the Escape Bag beyond what is expected of a person who makes and designs such bags.

41 The respondents also submitted that the appellant’s criticism of the primary judge’s finding that “the selection and use of perforated neoprene as the fabric for the Escape Bag or its use in combination with sailing rope …” did not involve an act of artistic craftsmanship should be rejected. They submitted that the Escape Bag is a conventional tote or carry-all bag and that this was a matter of agreement between the experts, Ms Beale and Mr Smith. They submitted that the use of these commercially available materials to make a commercial product does not rise to a level of artistic craftsmanship.

42 The respondents submitted that the decision of the primary judge discloses no error, let alone error of the type that would justify appellate intervention having regard to the principles summarised by Allsop CJ and Perram J in Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd (2018) 261 FCR 301 at [2]-[10] per Allsop CJ and [43]-[54] per Perram J.

CONSIDERATION

43 The definitive authority on the meaning of the phrase “a work of artistic craftsmanship” is the decision of the High Court in Burge. In Burge, the respondent, Mr Swarbrick was a naval architect who designed a racing yacht called the JS 9000. In the course of designing the yacht, he created a full scale model (known as the Plug) of the hull and deck of what became the finished yacht. The question was whether the Plug was a work of artistic craftsmanship. The High Court held that it was not.

44 In so holding, the High Court adopted an objective test based substantially on the reasoning of Lord Simon in Hensher. The High Court observed that the phrase “work of artistic craftsmanship” is a composite phrase that must be construed as a whole: Burge at [56].

45 The High Court referred to the evidence given by Mr Swarbrick and made some observations in relation to it that are of particular relevance to this appeal given the reliance placed by the appellant on the evidence given by Ms MacGowan as to her intentions. Their Honours said at [63]-[64]:

[63] The answer to the question whether the Plug is a “work of artistic craftsmanship” cannot be controlled by evidence from Mr Swarbrick of his aspirations or intentions when designing and constructing the Plug. His evidence was admissible. But the operation of the statute does not turn upon the presence or absence of evidence of that nature from the author of the work in question. The matter, like many other issues calling for care and discrimination, is one for objective determination by the court, assisted by admissible evidence and not unduly weighed down by the supposed terrors for judicial assessment of matters involving aesthetics.

[64] The statute does not give to the opinion of the person who claims to be the author of “a work of artistic craftsmanship” the determination of whether that result was obtained; still less, whether it was obtained because he or she intended that result. Given the long period of copyright protection, the author, at the stage when there is litigation, may be unavailable. Indeed, as Pape J noted in Cuisenaire v Reed [1963] VR 719 at 730, the author may be dead. Again, intentions may fail to be realised. Further, just as few alleged inventors are heard to deny the presence of an inventive step on their part, so, it may be expected, will few alleged authors of works of artistic craftsmanship be heard readily to admit the absence of any necessary aesthetic element in their endeavours.

46 The High Court found that speed was the overriding consideration in the design of the JS 9000 and all other design factors were of lesser importance: Burge at [71] and [72]. The Court said at [73]:

Taken as a whole and considered objectively, the evidence, at best, shows that matters of visual and aesthetic appeal were but one of a range of considerations in the design of the Plug. Matters of visual and aesthetic appeal necessarily were subordinated to achievement of the purely functional aspects required for a successfully marketed “sports boat” and thus for the commercial objective in view.

47 The High Court emphasised that the critical point in determining whether a work is “a work of artistic craftsmanship” does not turn on assessing the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the work, or in assessing any harmony between visual appeal and utility, but rather “on assessing the extent to which the particular work’s artistic expression, in its form, is unconstrained by functional considerations”: Burge at [83].

48 The more that functional considerations dictate the form of the work, the less scope there may be for finding that there exists the substantial artistic effort and expression which characterises a work of artistic craftsmanship. As the High Court noted in Burge at [84], “[q]uestions of fact and degree inevitably arise”.

49 As we have mentioned, the appellant says that the primary judge erred in giving improper weight to the evidence of Mr Smith, and that her Honour should have given greater weight to the evidence of Ms Beale and Ms MacGowan.

50 As to Ms MacGowan’s evidence, we have referred to what the High Court said in Burge concerning the evidence of the author of what is alleged to be a work of artistic craftsmanship. The author’s evidence is admissible, but the weight it may be afforded is often affected by two particular factors. The first is that the question of whether an object is a work of artistic craftsmanship does not depend on the author’s aspirations and intentions. This is because the question is to be addressed by reference to the object itself and the extent to which any artistic expression manifested in the object is unconstrained by functional considerations. Secondly, just as few inventors are heard to deny that they made an inventive step, it is to be expected that the views of an author as to the artistic qualities of his or her own work may not be shared by others who have different tastes and preferences.

51 The fact that the primary judge accepted Ms MacGowan’s evidence as to her aspirations and intentions did not require that it be given weight in deciding whether the Escape Bag was a work of artistic craftsmanship. There is no inconsistency in her Honour having accepted Ms MacGowan’s evidence and holding that the Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship. In our opinion, the primary judge’s treatment of Ms MacGowan’s evidence is not shown to have been affected by any error.

52 The appellant’s complaint concerning the primary judge’s preference for Mr Smith’s evidence is not reflected in any ground of appeal. At times the appellant’s submissions on this topic seem to amount to a complaint about the admissibility of Mr Smith’s evidence due to what was said to be his lack of expertise in bag design. Ultimately, however, the submission was that the primary judge should have given Mr Smith’s evidence no or at least little weight on the basis that he did not have “extensive experience in bag design”.

53 The primary judge made findings in relation to both Mr Smith’s and Ms Beale’s expertise at Reasons [4]. She found that Mr Smith was an expert in the design, development and manufacture of handbags and accessories with more than 30 years’ experience. At paras 15 and 16 of Mr Smith’s Expert Report, he states:

15. As the matters I have set out above indicate, a good deal of my professional experience relates to the design and manufacture of leathergoods (including handbags). However, I have also worked extensively with other fabrics such as canvas, polyurethane, nylon, PVC and waxed cotton, Including when used for handbags.

16. As a result of my training and experience, I am very familiar with:

(a) the range of handbag styles that are, and have over recent decades been, widely available on the market (three of which were the subject of the RMIT courses referred to above - clutch, tote and gusseted);

(b) the process of designing handbags;

(c) the range of materials that are, and have over recent decades been, commonly used to make handbags and the issues that can arise in connection with the use of those materials;

(d) the types of accessories that are, and have over recent decades been, commonly used on handbags (such zips, press studs, magnetic closures etc);

(e) the development of sample handbags from a design;

(f) the process of moving from the design / sample phase of product development to commercial production of a handbag; and

(g) the manufacturing techniques and processes that are, and have over recent decades been, commonly used in relation to the commercial production of handbags.

54 Mr Smith’s evidence was not objected to by the appellant and he participated in an expert conference with Ms Beale at which they considered a number of questions including whether there was “agreement between the experts as to the functional considerations which inform the design and manufacture of tote bags and carry all bags …”.

55 The appellant emphasised in its submissions on this topic that Mr Smith did not have professional qualifications in bag design. But there is other evidence which showed that he had taught short courses on bag making, including tote bag making, sponsored by a well-known educational institution (RMIT) which were promoted as suitable for people who were interested in the craft of designing and making bags by hand. Ms Beale, on the other hand, agreed that she was not trained in constructing or making bags, and it appears from her evidence that she had very limited experience in bag design. Although Ms Beale recalled having made a tote bag as a university student, she was not shown to have anywhere near the same degree of involvement in the design and manufacture of bags as Mr Smith.

56 The appellant placed considerable reliance on the following passage of evidence given by Mr Smith and Ms Beale in their concurrent session:

MR CAINE: Yes. And so the overall look of that bag meets Ms MacGowan’s design philosophy that you find beauty and style in simplicity?

MR SMITH: I can’t say beauty, because I don’t find it beautiful, but some people may, but it’s simple, elegant, and distinctive, yes, I agree.

MR CAINE Thank you. And that was her design philosophy, and she has achieved that with the State of Escape bag that you can see in that image?

MR SMITH: That’s – would be for her to say, not me. I – she was a designer; she knew what she wanted the end look to be like.

MR CAINE: And so you and Ms MacGowan disagree on beauty, but otherwise you accept the matters I’ve put to you?

MR SMITH: Yes.

MR CAINE: Yes, thank you. Ms Beale, is there anything that you would care to say about the exchange I’ve just had with Mr Smith?

MS BEALE: Thank you, Mr Caine. Whilst we talk about beauty as a subjective term, it actually has a very strong history in design practice, and one of the overriding principles that has informed design from the arts and crafts movement onwards, was this notion of a quote by William Morris, in a lecture that he made in 1880, which said:

Have nothing in your homes that you do not know to be useful and believe to be beautiful.

And so my feeling when I was reading the notes on this case, in terms of the information presented to me, was that the designer was following in a tradition of design practice that is getting back to my earlier evidence around what is good design, and I believe that if you think about that concept of simplicity, elegance, a lack of extraneous material, that is a term that is how a designer would refer to an object as beautiful.

57 In this evidence Ms Beale suggested, albeit in a slightly round-about-way, that the Escape Bag was “beautiful”. Mr Smith, on the other hand, stopped short of accepting that it was beautiful, but did acknowledge that it was simple, elegant and distinctive, terms which Ms Beale also used when describing the design.

58 The appellant submitted that Mr Smith was not as qualified as Ms Beale to express opinions on the aesthetics of bags or bag designs. Even if that were true (we express no view one way or the other) as the High Court noted in Burge at [83], whether a work is a work of artistic craftsmanship does not turn on an assessment of the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the work.

59 Mr Smith was by his training and experience well qualified to give an expert opinion on matters addressed in this evidence including the functional considerations which inform the design and manufacture of tote bags and carry all bags and it was open to the primary judge to give his evidence considerable weight. In our opinion the appellant’s complaint that the primary judge gave Mr Smith’s evidence improper or excessive weight is without merit.

60 The next matter to be considered concerns the challenge to the primary judge’s finding that Ms MacGowan did not approach the design and manufacture of the Escape Bag as an artist-craftsperson. That conclusion rested on the finding that Ms MacGowan “… had no special training, skill and knowledge relating to the design and manufacture of handbags and many of the issues encountered were purely functional in nature”.

61 In a passage approved by the High Court in Burge at [61], Lord Simon said of the phrase “work of artistic craftsmanship” in Hensher at 91:

“A work of craftsmanship, even though it cannot be confined to handicraft, at least presupposes special training, skill and knowledge for its production … ‘Craftsmanship’, particularly when considered in its historical context, implies a manifestation of pride in sound workmanship – a rejection of the shoddy, the meretricious, the facile.

62 The evidence indicated that Ms MacGowan had no background in bag design. She had trained and worked as a graphic designer before working in her husband’s wine making company. Before designing the Escape Bag, she had contemplated making shoes out of neoprene. But there was no evidence that she had ever designed or made any form of bag before she started work on the Escape Bag.

63 Although the appellant pointed to evidence of Ms Beale suggesting that there was an exercise of skill on the part of Ms MacGowan in designing and making the Escape Bag, that evidence is not inconsistent with the primary judge’s finding that Ms MacGowan did not approach the design and manufacture of the Escape Bag as an artist-craftsperson.

64 The appellant submitted that to require specialist training and knowledge in the design and manufacture of handbags would unduly limit the scope for original contribution by a person whose skill and experience was acquired outside the relevant field. However, we do not understand her Honour to have held that it was essential that to be an artist-craftsperson a person must have specialist training and knowledge in a particular field. Her Honour correctly recognised that the fact that a person does not possess special training, skill and knowledge in the relevant field (in this case bag design) is at the very least a factor that may tend to show that the work that he or she has created is not a work of artistic craftsmanship.

65 One of the specific challenges raised by the appellant concerns what it referred to as the primary judge’s finding that the selection and use of perforated neoprene, or its use in combination with sailing rope, in the Escape Bag did not involve an act of artistic craftsmanship. The appellant submitted that the primary judge erred in finding that the Escape Bag was not a work of artistic craftsmanship for the reason that (or for reasons including that) neoprene and sailing rope were materials that were readily available that could be used without any particular training, skill or knowledge.

66 If the appellant is to be understood as suggesting that these considerations were treated by her Honour as determinative, then that reflects a misunderstanding of her Honour’s reasons. If, on the other hand, the appellant is contending that these considerations were irrelevant to the question which her Honour was required to decide, then we think the appellant’s contention is legally incorrect. What the primary judge found was that (contrary to the appellant’s submissions to her Honour) there was no act of artistic craftsmanship involved in the selection of perforated neoprene and sailing rope as materials for use in the manufacture of a carry bag.

67 It is worth noting that Ms MacGowan observed in an email she wrote to her co-director, Ms Maidment, on 27 November 2012 that “[i]t looks like all the top designers have a neoprene bag in their collections …”. And it was not disputed by the appellant that rope had also been used to make handles for carry bags. Ms MacGowan said she used sailing rope for its structural quality, which she considered important. The fact that Ms MacGowan used “perforated neoprene” and “sailing rope” in her design reflects minor variations in design detail that is consistent with the primary judge’s conclusion that the use of such materials to make an everyday carry bag was, at its highest, an evolution in styling rather than an act of artistic craftsmanship.

68 The appellant submitted that the primary judge did not consider the Escape Bag as a whole in deciding whether or not it was a work of artistic craftsmanship. Her Honour’s detailed recitation and analysis of the evidence shows that she understood that the question for determination was whether the Escape Bag was a work of artistic craftsmanship and her ultimate conclusion was that it was not. The detailed attention given in her Honour’s reasons to particular design elements reflected the evidence and submissions relied upon by the parties. For example, the experts were asked by the parties to comment on a range of specific features at least some of which were relied upon by the appellant in support of submissions made to the primary judge as to why it was that the Escape Bag is a work of artistic craftsmanship and not just a different style of tote bag. In our opinion there is no substance to this criticism of the primary judge’s overall approach.

69 With regard to the appellant’s challenge to the primary judge’s findings in Reasons [118], it is important to note the primary judge’s use of the word “alone”. Her Honour was not saying there that the combination of design features that make up the Escape Bag did not represent a departure from bags known as at November 2013. Rather, her Honour is to be understood as saying that the Escape Bag embodied common design features and methods each of which was known and used at that time. This is consistent with, and tends to reinforce, the primary judge’s conclusion that the Escape Bag represented an evolution in styling rather than a work of artistic craftsmanship.

70 Further, whether or not each of the design methods was “common practice” is not a matter which we consider to be of particular significance. In any event, we think the primary judge’s finding that such methods reflected common practice finds broad support in Mr Smith’s evidence. Mr Smith accepted that there were a few design features that were unfamiliar to him as finishes for a handbag: see Reasons [101] and [103]. However, it is clear that each of these performed a predominately functional role.

71 The appellant also submitted that the primary judge failed to give proper weight to the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the bag, its artistic quality, and the artistic effort that went into designing it. It submitted that the primary judge should have found that the Escape Bag manifested a real and substantial artistic element. We have dealt with these criticisms in the context of our discussion of the expert evidence and the passage in the High Court’s judgment in Burge at [83]. In any event, what weight should be given to any evidence relied upon by the appellant as to the “beauty or aesthetic appeal” or the “artistic quality” of the Escape Bag was a matter for her Honour. We are not persuaded that her Honour made any error in assessing what weight should be given to the evidence directed to those matters. The same is true, in our opinion, of the primary judge’s assessment of the evidence relating to the functional considerations relevant to the design of the Escape Bag and, in particular, the extent to which its design was unconstrained by functional considerations.

72 The primary judge found at Reasons [120] that the choice of perforated neoprene as the fabric for the Escape Bag was unconstrained by function. Although the respondents did not challenge that finding, we have difficulty accepting it. It seems to us that perforated neoprene would not have been selected by Ms MacGowan had it not possessed the strength and durability necessary for use in a useful and practical carry bag. As Mr Smith noted in his evidence, a functional element of a tote or carry-all bag is that it have a durable base and sides. Of course, many other materials might have been used in place of perforated neoprene, but we do not think it is correct to say that the selection of material from which to make the body of the bag was “unconstrained by function”.

73 In any event, the primary judge’s careful analysis of the evidence at Reasons [110]-[117] shows that the design of the Escape Bag was substantially constrained by function. In our view functional considerations substantially outweighed other considerations pertaining to its visual and aesthetic appeal in the determination of the shape, configuration and finish of the Escape Bag.

74 The appellant submitted that this was a clear case in which the primary judge’s conclusion was wrong and that her Honour’s decision should on that basis be overturned. For the reasons given we reject that submission. In our opinion the primary judge’s conclusion that the Escape Bag is not a work of artistic craftsmanship was correct.

Disposition

75 The appeal will be dismissed. The appellant must pay the respondents’ costs of the appeal on a lump sum basis in a sum to be agreed or, in default of agreement, to be assessed by a Registrar of the Court.

I certify that the preceding seventy-five (75) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Greenwood, Nicholas and Anderson. |

Associate:

Annexure A