Federal Court of Australia

State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 57

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellants pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal as agreed or taxed.

3. The cross-appeal be allowed in part.

4. Order 1 of the Court’s orders made on 28 May 2021 be set aside.

5. Other than to the extent in order 4 above, the cross-appeal otherwise be dismissed.

6. The cross-respondents pay 90% of the cross-appellant’s costs of the cross-appeal.

7. Any party seeking to vary a costs order may do so by notifying the Court and the other party within 14 days of the proposed varied order it seeks accompanied by a written submission not exceeding 2 pages in support.

8. Any party served with a written submission in accordance with order 7 may file and serve a written submission not exceeding 2 pages in support of its position on costs within a further seven days thereafter.

9. Subject to any request by a party to the contrary which is accepted, costs will be determined without a further oral hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Background

1 After a hearing of seven days the primary judge published reasons for judgment of [1191] paragraphs rejecting all of the appellants’ claims including claims for misleading and deceptive conduct, passing off, trade mark infringement, and copyright infringement: State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 137. All of those claims arose from a common set of facts. Most of the 16 errors in the primary judge’s reasoning alleged on appeal are said to arise from the primary judge’s mischaracterisation of the evidence.

2 The first appellant, State Street Global Advisors Trust Company (SSGA), commissioned a statue entitled “Fearless Girl” from an artist, Kristen Visbal, as part of a marketing campaign to promote its Standard & Poor’s Depository Receipts (SPDR) Gender Diversity Index Exchange Traded Funds (known as the SHE fund) which tracks against SSGA’s Gender Diversity Index. That index measures the performance of large US capitalisation companies that exhibit gender diversity in their senior leadership positions.

3 SSGA installed the statue opposite the Charging Bull statue at Bowling Green Park on Wall Street in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City the night before International Women’s Day on 7 March 2017. A plaque was placed beneath the statue that stated “Know the power of women in leadership. SHE makes a difference” with SSGA’s logo. “SHE” referred to the ticker symbol of the SHE fund and the gender of the girl shown in the statue, Fearless Girl. At the same time SSGA launched a “Fearless Girl” marketing campaign in which SSGA called on 3500 companies in the US, UK and Australia representing more than US$30 trillion in market capitalisation to increase the number of women on their boards. This campaign received wide publicity around the world.

4 On 12 May 2017 SSGA and the artist, Ms Visbal, entered into an agreement (called a master agreement). Under the master agreement Ms Visbal granted SSGA an exclusive licence to “display and distribute two-dimensional copies, and three-dimensional Artist-sanctioned copies, of the Artwork to promote (i) gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector, and (ii) SSGA and the products and services it offers”. Ms Visbal otherwise reserved all uses of the statue to herself subject to certain restrictions, and the parties agreed certain “Pre-Approved Uses” which would not be subject to any obligation of Ms Visbal to discuss in good faith with, and obtain written approval from, SSGA. The master agreement also recorded that SSGA “filed an intent-to-use application to register the term “Fearless Girl” as a trademark (the “Mark”) in the United States Patent and Trademark Office” and SSGA is “the exclusive owner of the Mark”.

5 The exhibits to the master agreement include a copyright licence from Ms Visbal to SSGA and a trade mark licence from SSGA to Ms Visbal.

6 By the copyright licence Ms Visbal granted to SSGA the exclusive right to create and use two- and three-dimensional copies of the statue in connection with “(A) gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector; and (B) SSGA and the products and services SSGA offers and/or will offer at any time after the Effective Date”. Ms Visbal agreed not to “grant the rights described herein as granted to SSGA to any third party”.

7 The trade mark licence recorded that “SSGA is the exclusive owner of the FEARLESS GIRL trademark (the “Trademark”) in connection with goods and services that support women in leadership positions and the empowerment of women, and that promote public interest in and awareness of gender diversity and equality issues”. By the licence SSGA granted Ms Visbal:

an exclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, right and license to use the Trademark on and in connection with (i) three-dimensional copies of the Statue in various mediums and sizes in connection with the offer of goods for sale (“Merchandising”); (ii) two-dimensional copies of the Statue for Artist’s portfolio, for “fine art” purposes; and (iii) two-dimensional copies of the Statue in various mediums and sizes in connection with Merchandising (collectively, the “Licensed Products”).

8 In accordance with the trade mark licence SSGA is the registered proprietor of Australian Trade Mark No. 1858845 for the word mark “FEARLESS GIRL” in relation to the following services with a priority date of 16 March 2017:

(1) class 35: publicity services in the field of public interest in and awareness of gender and diversity issues, and issues pertaining to the governance of corporations and other institutions; and

(2) class 36: funds investment; financial investment advisory services; financial management of donor-advised funds for charitable purposes; accepting and administering monetary charitable contributions; financial information.

9 The respondent, Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (MBL), is an Australian law firm which had previously advocated on behalf of clients and independently on issues of workplace sexual harassment, gender discrimination in hiring, and the gender pay gap.

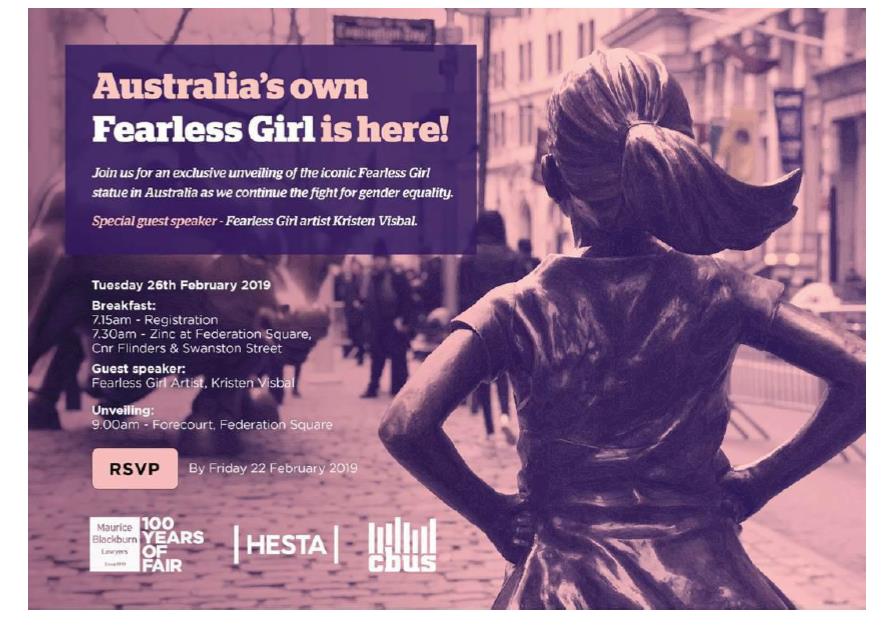

10 In February 2019 MBL commissioned Ms Visbal to produce a limited-edition reproduction of Fearless Girl for an Australian campaign concerning workplace gender equality including equal pay for women. Two co-sponsors, the Australian superannuation funds United Super Pty Ltd (Cbus) and H.E.S.T. Australia Ltd (HESTA), joined MBL’s campaign which was launched by the unveiling of the Fearless Girl replica at Federation Square in Melbourne’s CBD on 26 February 2019.

11 Before the planned launch of the gender equality campaign in Melbourne, SSGA and its subsidiary, State Street Global Advisors Australia Ltd (SSGAA), launched this proceeding, obtaining interim injunctive relief which was discharged a week later by the primary judge on the giving of certain undertakings without admissions.

12 In his principal reasons the primary judge evaluated the evidence and concluded that MBL was right that the Fearless Girl statue had a reputation in Australia separate and distinct from both SSGA itself and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Further, the primary judge considered that MBL’s campaign was directed to the public at large and concerned gender equality generally whereas SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign was directed to publicly listed companies and financial institutions and concerned gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector (particularly female representation on the boards of such companies). The primary judge considered that the evidence established that the Fearless Girl statue, reproduced below, had achieved a level of fame in Australia as a public artwork associated with gender diversity issues generally which dwarfed any association in Australia between SSGA, SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign and the statue.

13 The primary judge identified this distinction between: (a) the messages associated with the statue, (b) SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign, and (c) MBL’s gender equality campaign in a variety of ways in these terms:

(1) “the New York statue’s message was one of equality for women, not some endorsement for the values and aspirations of a large US financial institution [such as SSGA]”: [839];

(2) “there were many meanings conveyed by Fearless Girl that were unrelated to SSGA. Such meanings related to gender based violence, gender equality, equal pay and sexual harassment. Indeed to the broad public, the replica on display, as it is at Federation Square in Melbourne, presents as a “selfie-inducing” (apparently) depiction of a young girl in a defiant pose to which any number of different but positive messages can be attached. Such themes had little, if anything, to do with the finance industry, gender equality in corporate governance or the unknown SSGA in Melbourne”: [841];

(3) “MBL’s campaign was a social or political campaign intended to promote, in good faith, workplace gender equality and in particular equal pay”: [1078]; and

(4) “a desire to tap into the established narrative around Fearless Girl…was not a desire to tap into some narrative around State Street (US) and its association with the New York statue. Rather, the established narrative around the statue was in relation to gender equality”: [1080].

14 In this context, the primary judge rejected all of SSGA’s claims. The primary judge subsequently explained in State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 568 that despite his rejection of all of the appellants’ claims he proposed to grant relief in the form of a permanent injunction. While the primary judge accepted that the basis for the grant of an injunction was “not strong”, it was “sufficient” to impose a solution which his Honour hoped “may now resolve the unnecessary and continuing posturing of both parties”: [25]. The primary judge’s solution was to grant an injunction restraining MBL from making use or display of the replica of the “Fearless Girl” statue owned by it except where there is no plaque or other markings used with or on the replica, or if there is such a plaque or other markings, it must say that:

This statue is a limited edition reproduction of the original “Fearless Girl” statue in New York that was sculptured by the artist Kristen Visbal. The original statue was commissioned and is owned by State Street Global Advisors Trust Company. This reproduction is owned by Maurice Blackburn who purchased it from the artist. Maurice Blackburn has no association with State Street.

15 In its cross-appeal MBL contends that there was no proper foundation for the making of the injunction. In their appeal, the appellants contend that the primary judge rejected their claims because he mischaracterised the evidence and should have found that SSGA’s marketing campaign had given it a significant reputation and associated goodwill in Australia or, at the least, that the Australian public was aware of the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign and that it was used to distinguish the services of the entity behind the campaign. The appellants also contend that the fact that MBL did not challenge the validity of the trade mark means that the mark is taken to distinguish SSGA’s services from those of others and is not generic. Further, according to the appellants, the primary judge should have found that MBL intentionally appropriated to itself SSGA’s goodwill in Australia by reason of SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign.

16 The appellants observed that they did not get the opportunity to make oral submissions as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and posited that this might explain why, according to them, the primary judge consistently mischaracterised the evidence. This seems implausible in a case involving thousands of pages of material, multiple witnesses who gave oral evidence, and extensive reasons for judgment explaining why the primary judge did not accept the appellants’ case. This impression of implausibility is reinforced by the fact that the appellants have been unable to identify any material evidence or submission that they contend the primary judge overlooked.

17 Nor have the appellants identified any error of principle. While they contend that the primary judge incorrectly focused on the association between the statue and SSGA when it was unnecessary to establish specific awareness of SSGA or of the precise form of association, it is apparent that the primary judge acknowledged this principle in the context of both the passing off and misleading and deceptive claims at [752] and [851]. What the primary judge did was to focus on the claims as pleaded and argued to the effect that there was an association between the statue and SSGA and the statue and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign in connection with the SHE fund concerning gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector (particularly female representation on the boards of such companies). This was an orthodox approach.

18 As will be explained below, if the primary judge was correct about the differences between the reputation and associations in the mind of the Australian public in respect of the statue, SSGA and/or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign and MBL’s gender equality campaign, then the appellants’ repeated assertions of error by the primary judge are unsustainable. To take one example, the appellants referred to evidence of MBL’s intention to take advantage of SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign, alleging that the primary judge erred in dismissing the relevance of that intention at [774] and [904]. Two points should be made in response. First, subjective intention was relevant to the claims to the extent that it might support an inference that the intention was likely to be or was in fact achieved. Second, in a case such as the present, where part of the dispute involved the existence and significance of the distinction between the reputation and associations in the mind of the Australian public in respect of the statue, SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign, and MBL’s gender equality campaign, care was required to identify the content of the subjective intention and precise inferences this supported. As will be explained, the primary judge’s reasoning exhibits that required care.

19 Having considered the swathes of evidence upon which the appellants relied in the appeal, we are not persuaded that the primary judge’s conclusions about these fundamental differences were incorrect. Rather, they are supported by an evaluation of the evidence as a whole. We are persuaded, however, that the primary judge erred in making the injunction in circumstances where all of SSGA’s claims had properly been rejected and there was no evidence of any proposed legal wrong by MBL in respect of future use of its replica statue.

Scope of SSGA’s rights (ground 1)

20 The appellants contend that the primary judge misconstrued the rights held by SSGA and wrongly assessed all of SSGA’s claims by reference to the master agreement. Neither contention is sustainable.

21 The primary judge’s observation at [23] that “SSGA has sought to weave its web of statutory and tort claims in such a fashion as to effectively assert monopoly rights in an icon that it does not have” is not made in isolation. At [23] the primary judge also said “[t]here is considerable disparity between what [SSGA] paid for and what it now asserts it is entitled to protect. But Australian statute law and tort law cannot fill that gap”. The primary judge had to assess the rights which SSGA acquired from Ms Visbal under the master agreement as they were the ultimate source of SSGA’s allegedly infringed copyright and trade mark rights. Otherwise it is clear the primary judge understood that the other claims did not depend on the master agreement.

22 The primary judge also recognised that SSGA alone owns the trade mark. So much is clear from his Honour’s reasons at [956]. It is also clear from [681]–[1047] that the primary judge evaluated SSGA’s claims for misleading and deceptive conduct, passing off and trade mark infringement by reference to SSGA’s reputation and trade mark registration rather than its rights under the master agreement.

SSGA’s reputation in Australia - misleading and deceptive conduct (ground 3)

23 The appellants’ submission that the “reputation of the Statue in Australia as a symbol of [SSGA’s marketing campaign] cannot be disputed. It is why [MBL] chose the Statue (PJ[105])” discloses the impermissible elisions underlying the appellants’ case which the primary judge rightly rejected.

24 First, the reputation of the statue in Australia as a symbol of SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign was in dispute. As noted by the primary judge, MBL’s case was founded on the propositions that “SSGA has wrongly purported to equate the reputation in the New York statue with SSGA’s own Fearless Girl campaign or SSGA itself” and “in Australia, the reputation and message conveyed by the New York statue has existed independently of SSGA and that whilst some people in Australia might have known of the New York statue, very few people outside the US were likely to associate SSGA with it”: [685]. The primary judge had to consider these propositions.

25 Second, the primary judge was persuaded that MBL’s propositions were correct. In addition to the conclusions identified at [12] above, the primary judge said at [836]–[837]:

Now it may be accepted that the unveiling of the New York statue was a matter of some publicity at the time. But the difficulty for SSGA is taking the next step. It has failed to establish that the relevant members of the class in Australia in 2019 associated the New York statue with SSGA. SSGA conflates the reputation of the New York statue with its own reputation. In my view, the latter was not relevantly proved in Australia at the relevant time. SSGA was largely unknown by members of the public in Victoria in 2019, let alone as being associated with the New York statue.

Further, there was no “spill-over reputation” of the Fearless Girl campaign and its association with SSGA into Victoria in 2019.

26 Third, the primary judge did not accept that MBL chose the statue because of its association with SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Rather, it is apparent from the primary judge’s reasons as a whole that he concluded that MBL chose the statue because of its iconic status as a symbol representing gender equality and gender diversity generally, a status which was separate from, and independent of, the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign and SSGA. It should go without saying that the mere fact that SSGA called its marketing campaign “Fearless Girl” in reference to the statue does not mean that the Australian public knew of SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign or made any association between SSGA and “Fearless Girl” — either the statue or the concepts which she came to represent.

27 The problem with the appellants’ case before the primary judge and in this appeal is also apparent in their further proposition that MBL’s first invitation to its launch event “described the Statue as “iconic” and depicted the Statue in situ on Wall Street, staring down the Charging Bull. The message conveyed required no further explanation. The Statue’s reputation is assumed”. The fact that MBL’s first invitation assumes that the statue has a reputation well-known in Australia does not establish the appellants’ case that this reputation involved any association with SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. The effect of MBL’s case, which the primary judge accepted at [834], was that:

…the evidence showed that the New York statue, as a public artwork, took on a life of its own from the day it was unveiled and had many meanings to many people.

28 The phrase “life of its own”, in context, means a reputation separate and distinct from SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. It is this separate and distinct reputation of the statue which is assumed in MBL’s first invitation, not any association with SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. In accepting this conclusion the primary judge was not saying (and MBL was not asserting) that SSGA’s trade mark was generic. The impugned findings at [834], [841]–[845], to the effect that the statue immediately took on a “life of its own”, separate and distinct from SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign, are in the context of the misleading and deceptive conduct and passing off claims, not the alleged trade mark infringements.

29 It is also not the case that the primary judge erred by focusing on SSGA’s activities in Australia. Rather, the primary judge correctly focused on SSGA’s reputation in Australia. While the primary judge referred at [50] to SSGA’s “activities and reputation in Australia” it is apparent from his reasons as a whole that the primary judge considered all of SSGA’s activities (including but not limited to its activities in Australia) for the purpose of evaluating its reputation in Australia. See, for example, his Honour’s reasons at [27]–[57] in which his Honour considered the development of the Fearless Girl marketing campaign in the United States. Further, it is apparent from [789]–[802] and [833]–[870] that the primary judge did not accept the appellants’ proposition that SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign (as opposed to the statue itself) had acquired and retained a global reputation as at the date of MBL’s impugned conduct.

30 The appellants’ real point in this regard is that the primary judge’s assessment of the evidence leading to these conclusions was wrong in that there was “strong documentary evidence demonstrating the existence of a substantial “spillover” reputation of the Statue, Trade Mark and [SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign] in Australia at the relevant time”, and “SSGA is and was seen as the originator of the Trade Mark, [SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign] and Statue”, and the primary judge wrongly sought to disaggregate the reputation of the statue, trade mark and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign.

31 Dealing with these propositions in reverse order, we do not accept any error by the primary judge in seeking to identify the relevant reputations in Australia. MBL’s case was that from the moment it was unveiled the statue acquired a reputation (including in Australia) which had nothing to do with SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. The primary judge was bound to deal with MBL’s case and did so on the evidence. There was no principle preventing the primary judge from concluding that the statue had a reputation in Australia unconnected to SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. The appellants are entitled to contend in the appeal that the evidence supported a contrary conclusion, but the assertion of some kind of error in principle because of the primary judge’s conclusions about the different reputations and associations involved is untenable. Equally untenable is the contention that the primary judge’s conclusion of the lack of any “spill-over reputation” in Australia of SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign is “largely unexplained”. The primary judge’s conclusion to that effect at [837] was supported by the reasoning which precedes and follows at [833]–[836] and [838]–[870].

32 The fact that SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign was perceived by it to be “extraordinarily successful” does not mean that in Australia at the relevant time (that is, the time of MBL’s conduct) SSGA “is and was seen as the originator of the Trade Mark, [SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign] and Statue” (emphasis added).

33 The appellants’ proposition that the primary judge wrongly evaluated the evidence and should have concluded that the statue’s reputation in Australia was associated with SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign must also be rejected. According to the appellants the “volume of media articles in Australian newspapers, financial industry websites and other media services which referred to the Statue and the [SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign], and recognition of the [SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign] in the advertising industry, including in Australia, establishes this”. The appellants took us to many examples of these articles and publications referring to the statue and SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign, as well as internal documents of MBL, HESTA and Cbus to support their case.

34 The best examples of the internal documents (from the appellants’ perspective), however, do not support their case. For example, it is true that an internal MBL document identifies that the New York statue was commissioned by SSGA and “was intended to raise awareness of the need to improve gender diversity in corporate leadership roles and to celebrate the power of women in leadership and the potential of the next generation of women leaders”. The document then says “[w]e are harnessing the popularity of Fearless Girl and the emotions that she provokes in all who see her”. What is critical is that the expressed intention was to harness the popularity of Fearless Girl, the statue, and the emotions that she provokes, not to harness any reputation of SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign in connection with gender diversity in corporate leadership roles.

35 Similarly, the fact that MBL, HESTA and Cbus became aware that SSGA had commissioned the New York statue and used it for SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign does not mean that they intended to use the replica to trade on any association between the replica and SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Far from supporting the appellants’ case, these internal deliberations about the text of a proposed media release expose that the message of the MBL, HESTA and Cbus campaign was not focused on women in corporate leadership roles (specifically, board memberships) but on gender equality generally.

36 The further problem for the appellants is that it is apparent that the primary judge had regard to all of the articles and other material (such as social media engagement) relied on by the appellants, including at [842]–[847] and [858]–[862]. However, the primary judge also properly had regard to the following circumstances, amongst other matters:

(1) “SSGA’s marketing campaign concerning the New York statue was directed at publicising the SHE fund, which was not directly accessible to investors in Australia”: [835];

(2) “…the New York statue’s message was one of equality for women, not some endorsement for the values and aspirations of a large US financial institution”: [839];

(3) “there have been numerous media articles published since the unveiling of the New York statue, each of which mentions the New York statue but which do not mention the words “State Street” or “SSGA””: [840];

(4) “the evidence demonstrated that there were many meanings conveyed by Fearless Girl that were unrelated to SSGA … Such themes had little, if anything, to do with the finance industry, gender equality in corporate governance or the unknown SSGA in Melbourne”: [841];

(5) “although SSGA put into evidence articles associating the New York statue with SSGA, most of these articles were from early 2017 when the New York statue was unveiled, and then in early 2018 when it was announced that the New York statue was to be moved to its current location”: [842]. In this regard the primary judge had identified that MBL’s conduct occurred in early 2019;

(6) SSGA’s market in Australia and internationally is constituted by sophisticated wholesale investors such as high level traders, stockbrokers, financial planners, wealth managers and private banks and there was no evidence of SSGAA advertising to the general public in relation to its financial services or at all: [849];

(7) “SSGA led no direct evidence that members of the general public would know the name “State Street” or know of its business in Australia”: [851]; and

(8) SSGAA’s promotion of the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign was directed to its sophisticated and select institutional clients and not the public at large and did not focus on Fearless Girl: [853]–[856].

37 The primary judge drew six conclusions in these terms from the evidence at [865]–[870]:

First, I accept that members of the Australian public may have known of the New York statue and the name “Fearless Girl” and recalled in a very general sense the publicity several years earlier concerning its unveiling in New York.

Second, I also accept that such members would have associated the New York statue and the name “Fearless Girl” with gender diversity and other social issues concerning equal opportunity and equal pay.

Third, I do not accept that such members, except a very small wealthy few, would have known of SSGA generally.

Fourth, I do not accept that such members, except a very small wealthy few, would have known that State Street (US) was the commissioner of the New York statue.

Fifth, none of the few that I have identified in propositions three and four would:

(a) mix up MBL (or indeed HESTA or Cbus) with SSGA;

(b) consider that MBL (or indeed HESTA or Cbus) was associated with SSGA.

Sixth, it is problematic to say the least to suggest that the ordinary and reasonable member of the Australian public would, in early 2019, think that SSGA, a Boston based global financial asset manager, had licensed or approved of the replica as it was unveiled in Australia by a local plaintiff law firm known for its social justice work and its “fight for fair” mantra. Indeed that particular plaintiff law firm was well known in Australia for having a philosophy and pushing campaigns that were diametrically opposed to the likes of global financial asset managers.

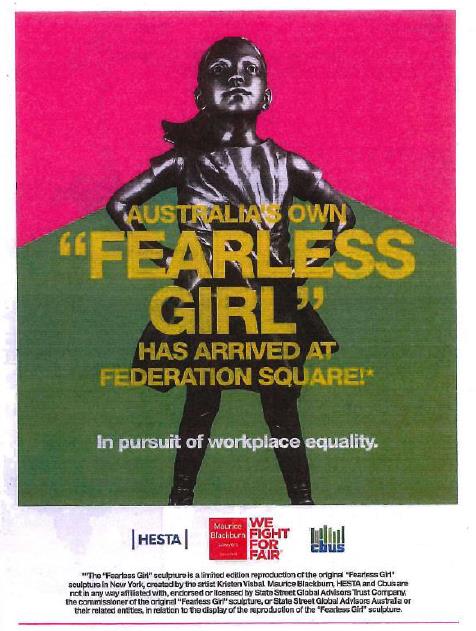

38 Contrary to the appellants’ submissions, these conclusions do not include the primary judge accepting “awareness in Australia by members of the public of the Statue and the [SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign]”. As noted, the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign concerned SSGA’s call for 3500 companies in the US, UK and Australia to increase the number of women on their boards in the context of the promotion of SSGA’s SHE fund. The awareness to which the primary judge is referring in [865] and [866] is of the statue and the publicity about its unveiling “in a very general sense” and the association of the statue with gender diversity and other social issues concerning equal opportunity and equal pay, and not, by implication, SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign.

39 We also do not accept the appellants’ submission that the distinction which MBL drew (and which the primary judge accepted) between the goodwill generated by SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign and the statue’s reputation was illusory and contrary to authority. The fact that SSGA commissioned the statue and chose to locate it opposite the Charging Bull statue on Wall Street did contribute to the statue taking on a “life of its own”. No doubt SSGA acted in both respects to increase the effectiveness of its Fearless Girl marketing campaign. But that does not mean that the reputation or associations of the statue in Australia had anything to do with SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. The distinction the primary judge drew was founded in the evidence. The distinction is not contrary to authority. Specifically, Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC v Bega Cheese Limited [2020] FCAFC 65; (2020) 377 ALR 387 at [123]–[135] is about the goodwill of a business. The primary judge’s point was that SSGA did not have any material goodwill in Australia in connection with the statue at the time of the impugned conduct of MBL, HESTA and Cbus.

40 As discussed, the appellants submitted that the primary judge focused on the wrong question as SSGA “needed only to establish that the Trade Mark, Statue and the [SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign] were known by members of the public in Victoria in 2019, and to be connected to a source, even if the identity of the source was unknown or not readily recalled”. However, and as noted, the primary judge dealt with the case as pleaded and as argued for by the appellants, the focus of which was the association between the statue and SSGA and the statue and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. The primary judge acknowledged that “it may be unnecessary to establish that the relevant purchasing class knew the precise identity of the [appellants] to establish the tort of passing off” (at [752]) and “that it was not necessary for SSGA to lead” evidence “that members of the general public would know the name “State Street” or know of its business in Australia” (at [851]). In these circumstances, the appellants’ references to parts of the reasons where the primary judge focused on knowledge of SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign (at [870], [908]–[910] and [918]) do not expose error.

41 The appellants also alleged that the primary judge erred in relying on the evidence of Mr Geoffrey Edwards, a consultant and adviser on sculpture to public and private collections throughout Australia and formerly the Senior Curator of Sculpture at the National Gallery of Victoria and Director of the Geelong Art Gallery. The primary judge said he had no reason to doubt the opinions Mr Edwards expressed “although his evidence had its obvious limitations”: [80]. According to the appellants, Mr Edwards’s expertise was confined to fine art and did not extend to the use of symbolic merchandising characters in marketing campaigns such as SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign.

42 The primary judge recorded at [805] that “Mr Edwards expressed the following opinions which I was given no reason to question”. In its submissions in the appeal the appellants did not suggest that they had cross-examined Mr Edwards and he conceded that: (a) there was a valid distinction in this case between “fine art” and merchandising as part of a marketing campaign, or (b) his opinions did not apply to the Fearless Girl statue. In these circumstances the assertion of error on the part of the primary judge in giving weight to aspects of Mr Edwards’s opinions remains mere assertion. It is also apparent that the evidence of Mr Edwards of most concern to the appellants, that the association between an artwork and the person commissioning it usually was a “fleeting recognition” and “short-lived”, existing at the time of launch but from then on “it’s pretty much the artist and the artwork that resonate with the community”, was the result of the appellants’ own cross-examination of Mr Edwards: see [823] of the primary judgment. While Mr Edwards unsurprisingly agreed that he was not an expert in marketing, it was not suggested to him that the statue was not “fine art”. Further, the appellants put the same submissions to the primary judge, which the primary judge rejected. In so doing the primary judge said at [831] that:

…SSGA’s criticism of Mr Edwards fails to grapple with his evidence about the passage of time since the launch of the New York statue and his evidence that the association of artwork with the commissioner of the work is usually short-lived. Indeed most of the articles in evidence concerning the New York statue were from early 2017 or early 2018.

43 The appellants submitted that at [831] the primary judge ignored the close temporal proximity between the unveiling of the statue in 2017, the announcement that the statue was to be moved in or about April 2018, the time of the moving of the statue from Bowling Green to in front of the New York Stock Exchange in December 2018, and the unveiling of the replica in February 2019. However, Mr Edwards’s opinions were informed by the original placement of the Fearless Girl statue opposite the Charging Bull statue. In Mr Edwards’s opinion this partly explained the fact that the Fearless Girl statue had taken on “a story of its own” disconnected from its commissioner, SSGA. Mr Edwards also knew that the creator of the Charging Bull statue objected to the placement of the Fearless Girl statue which was subsequently moved.

44 The public discourse generated by these circumstances exposes the extent to which the Fearless Girl statue had come to represent ideas far removed from SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign focusing on gender diversity on corporate boards. According to the public discourse, the (male) sculptor of the Charging Bull statue claimed that the Fearless Girl statue (created by a female artist) was “violating his legal rights as an artist”, and his sculpture was a symbol for America and for “prosperity and strength”, while Fearless Girl was a mere “advertising trick”. Vogue, for example, commented in response that the Charging Bull was apparently “not strong enough to duke it out with a girl…an old bull fights for relevance against a fearless future female leader? Looks a lot like a symbol to us”. Fortune Magazine said that the “presence of the new statue threatens the creator of the bull” and women would fight to allow the Fearless Girl statue to keep her place in the world. Harpers Bazaar described the location of the Fearless Girl statue opposite the Charging Bull as part of the “current battle of the sexes” and described all women as standing, hands on hips, “defiantly staring down the bulls in our midst” including the male artist who created Charging Bull who had claimed that the Fearless Girl statue “corrupted his artistic integrity”.

45 Accordingly, the fact of the original location and relocation of the Fearless Girl statue between 2017 and 2018 was an important part of the statue taking on a “life of its own” and, as Mr Edwards put it, of SSGA as the commissioner of the statue and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign becoming “less and less relevant (to the extent it ever were considered relevant)”.

46 None of this assists the appellants in establishing error.

47 Far from it, it reinforces the accuracy of the primary judge’s conclusion that the Fearless Girl statue was associated with a wide range of ideas transcending gender diversity on corporate boards. The statue, literally and metaphorically, concerned womens’ place in the world, the fact of their presence, their occupation of public space, their difference from men, their capacity to contribute if recognised and accepted as fully autonomous human beings, as well as the systemic and structural reality which women face that the very fabric of the spaces they occupy in public life have been created by and for men.

48 The appellants submitted that the primary judge erred at [830] in comparing the Fearless Girl statue to Rodin’s “The Thinker” sculpture, observing that the Fearless Girl statue “was commissioned for use and used as a symbol in a marketing campaign by an advertising agency for SSGA” rather than sitting in a Parisian museum. Mr Edwards had used the Rodin sculpture as an example of the artistic tradition of naming authorised replicas by the same name as the original work. The primary judge’s point at [830] was not that the Fearless Girl statue was comparable to a Rodin sculpture but that the Fearless Girl statue was not, as the appellants would have it, akin to the Oscar statue which was synonymous with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. On the evidence, that conclusion is unimpeachable; her origins may be in the very nature of capitalism, but Fearless Girl’s significance rapidly transcended her origins.

The association representations (grounds 2(b) and 5)

49 The appellants noted the primary judge’s findings that: (a) the MBL, HESTA and Cbus gender equality marketing campaign was a comprehensive marketing campaign intended to reach all channels of consumption with maximum exposure ([761]), (b) each of MBL and its campaign partners used the launch event to promote themselves by tying their name to that of Fearless Girl ([762]–[763]), and (c) each of the campaign partners saw significant value to them in having their businesses and brands associated with the campaign ([763] and [893]). The appellants contend, however, that the primary judge then erred in dismissing the relevance of the similarities between the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign and the MBL gender equality campaign at [889]. According to the appellants, these similarities “would have reinforced the association between the parties’ campaigns” in the minds of the public.

50 This contention assumes that the Australian public were aware of the details of the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign, a proposition that rightly found no favour with the primary judge at [889]. It also disregards the fundamental difference between SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign to promote the SHE fund (unavailable in Australia) by a call for increased gender diversity on the boards of large corporations and MBL’s purpose of leveraging the wide range of other ideas associated with the Fearless Girl statue in support of gender equality generally, including but not limited to, the workplace including equal pay for women.

51 The primary judge also did not err at [774] and [904] by focusing on the “objective external conduct” of MBL, HESTA and Cbus rather than their internal communications. As noted, subjective intention may assist in the drawing of an inference that the “objective external conduct” was likely to achieve its intended purpose of misleading, but ultimately the question remains the effect of that “objective external conduct”. Further, as also noted, in the present case the dispute included the nature or content of the subjective intention – on the appellants’ case to leverage off SSGA’s reputation and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign and on MBL’s case to leverage off the range of ideas about gender equality associated with the Fearless Girl statue separate from and unconnected to SSGA’s reputation and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign.

52 In asking “so what?” at [904] in response to the proposition that MBL was seeking to leverage its campaign off the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign the primary judge did not err. His point that this “does not establish that [MBL] made the representations concerning an association with SSGA” remains sound. This does not involve an unduly narrow framing of the question. If, as the appellants contended, MBL “sought to establish an association in the minds of the public” between the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign and the MBL gender equality campaign, the existence of that purpose was relevant only to the drawing of inferences as to whether or not the relevant objective external conduct achieved that alleged purpose. The primary judge found the relevant objective external conduct did not achieve that alleged purpose.

53 Nor, for that matter, did the primary judge accept the existence of the alleged purpose. The primary judge put this in various ways including:

(1) “SSGA’s select market in Australia is likely to be highly educated, commercially sophisticated, and not likely to make any connection between MBL, a law firm known to take on big corporate and government interests”: [850];

(2) “it is problematic to say the least to suggest that the ordinary and reasonable member of the Australian public would, in early 2019, think that SSGA, a Boston based global financial asset manager, had licensed or approved of the replica as it was unveiled in Australia by a local plaintiff law firm known for its social justice work and its “fight for fair” mantra. Indeed that particular plaintiff law firm was well known in Australia for having a philosophy and pushing campaigns that were diametrically opposed to the likes of global financial asset managers”: [870];

(3) “MBL and SSGA are hardly competitors and often serve diametrically opposed interests”: [916];

(4) “SSGA asserts that MBL was seeking to leverage the reputation in the New York statue for its own campaign. But this is a different thing to seeking to leverage any reputation SSGA has in relation to the Fearless Girl with the MBL campaign. It was clear from Ms Hanlan’s evidence that the narrative she was concerned with was “gender equality”, not the more limited messaging promoted by SSGA, being the influencing of board membership”: [917]; and

(5) “given the antithetical relationship between SSGA and MBL, one can readily assume that if members of the public made any assumptions of a connection between MBL and someone or something in relation to its use of the replica, they would likely assume a connection with the artist”: [918].

54 The appellants have not confronted this reality or the insuperable problem it creates for these aspects of their appeal.

55 The appellants’ proposition that by promoting the artist, Ms Visbal, in connection with the replica statue MBL, HESTA and Cbus strengthened the perception of an association or connection with the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign with which Ms Visbal was also involved is unsustainable. It is not apparent how the involvement of Ms Visbal in MBL’s gender equality campaign could have reinforced a purported connection with the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign in the face of the primary judge’s unassailable conclusions that SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign were effectively unknown in Victoria by the time of the MBL gender equality campaign: [836] and [841]. As emphasised, SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign was not gender diversity generally or equal pay for women, still less the idea of the place of autonomous women in the world, equally deserving of the opportunities, respect and dignity which are afforded to men, which Fearless Girl had come to symbolise.

56 The appellants contend that there “was at least one instance of confusion; which ought not to have been so lightly dismissed” at [943] where the primary judge said this:

SSGA referred to one email received by SSGA on 8 February 2019 from Ms Michelle Baltazar of the Financial Standard. She enquired whether SSGA would be interested in doing some cross-promotion with the Financial Standard in relation to the replica on the basis that she believed SSGA must have been involved. SSGA said this is a clear instance of confusion which was not dispelled by any disclaimer. But in essence, one swallow does not make a summer. And in any event, it appears this was the only communication SSGA received from a third party concerning the replica in Australia and on the face of the communication appears to have been a pitch for business. This takes SSGA nowhere.

57 We agree. The primary judge could also have made the point in response that the Financial Standard was in a unique position to have specialised knowledge of SSGA given the evidence of its role as the publishing division of the Rainmaker Group, which provides trade news, investment analysis and education for superannuation trustees, financial planners, researchers, consultants, investment managers, and professional investors. Further, the Financial Standard presented the annual MAX (Marketing Advertising and Sales Excellence) awards which was awarded to SSGAA in 2017.

58 We do not accept that the “sheer weight of social media content produced in the wake of the [SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign]” compelled the primary judge to reach a conclusion different from that which he reached. The primary judge weighed that evidence (for example, at [32], [34], [47], [49], [57], [778], [779], [786], [790] and [843]–[847]) along with all other evidence. No error is apparent in the primary judge’s reasoning process in this regard.

59 Nor are we persuaded that any error is apparent in the primary judge’s approach to the authorities about ss 18(1) and 29(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) sch 2) at [706]–[746]. The facts as found by the primary judge did not call for any analysis of the role of the concept that a “not insignificant number” of the relevant class are likely to have been misled or deceived subsequent to the obiter dicta in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; (2020) 278 FCR 450 at [23]–[24] and Trivago N.V. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185; (2020) 384 ALR 496 at [192], [193] and [206]. The primary judge made clear that his approach was to apply the obiter dicta in TPG and Trivago, but that the result would be the same if his Honour were permitted to apply the “not insignificant number” test: [746].

60 We do not accept that the primary judge erred at [880], [883], [888], or [906]–[907] in concluding that the alleged “association representations” were not made. The primary judge was right at [881] to say that “MBL and its campaign partners were loosely “associated” with the New York statue, but only in the sense that they were using and promoting the replica which was of course a copy of the New York statue” but that this went nowhere. It went nowhere because there was no association found in Australia between the New York statue and SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign.

The replica was the New York statue representation (grounds 2(a) and 5)

61 The primary judge rejected the appellants’ claim that MBL represented, and authorised HESTA and Cbus to represent, that the replica commissioned by MBL was the New York statue commissioned by SSGA: [874].

62 The appellants submitted that the primary judge’s reference to “sloppiness” by MBL in its drafting of invitations and promotional material (at [875] and [876]) exposed error. We disagree. Accepting imprecision of expression is not the same as accepting that MBL represented or authorised the representation that the replica was the New York statue.

63 The appellants said that at least one member of the public was misled. At [936] the primary judge said:

Further, SSGA points out that the replica is presently on display in Federation Square with no accompanying disclaimer. SSGA says that consumers continue to be misled. This is exemplified by a more recent Instagram post by a member of the public on 18 January 2020 of a photograph of the replica with the comment “Fearless Girl on loan from NYC”. I should say now that this is not part of the pleaded case. Little can be made of the Instagram post produced by SSGA on the last day of evidence in its voluminous tender bundle. Indeed, almost one year after the unveiling of the replica in Federation Square, SSGA found a single Instagram post referring to the “Fearless Girl on loan from NYC”. Further, what is notable is that of all the hashtags accompanying the post, there is no mention of SSGA.

64 We agree that this evidence was too little and too late to lend material weight to the appellants’ case.

65 It is also apparent that the appellants’ approach to the evidence was selective. As the primary judge identified at [875], MBL’s first invitation dated 12 February 2019 said “Australia’s own Fearless Girl is here!” in large letters and underneath in smaller letters said “[j]oin us for an exclusive unveiling of the iconic Fearless Girl statue in Australia as we continue the fight for gender equality”. As the primary judge said, the reference to “Australia’s own Fearless Girl” is not a representation that the statue is the New York statue. In that context, the reference to “the iconic Fearless Girl statue in Australia” cannot be reasonably understood as a reference to the New York statue.

66 The second invitation of 14 February 2019 is explicit, saying both that “Australia’s own “Fearless Girl” is here!” in large letters and underneath in smaller letters that the statue is a “limited edition reproduction of the original “Fearless Girl” sculpture in New York created by the artist Kristen Visbal”. In small letters at the foot of the invitation is the statement:

The purchase, promotion and installation of this sculpture, the surrounding communications, as well as the sponsors and promoters, are not in any way affiliated with, endorsed or licensed by State Street Global Advisors Trust Company or State Street Global Advisors Australia or their related entities.

67 The third invitation of 25 February 2019 says “Join us for the Australian unveiling of Fearless Girl” and has a statement in smaller letters which are clearly visible (as the statement is lengthy) saying:

The “Fearless Girl” sculpture is a limited edition reproduction of the original “Fearless Girl” sculpture in New York, created by the artist Kristen Visbal. Maurice Blackburn, HESTA and Cbus are not in any way affiliated with, endorsed or licensed by State Street Global Advisors Trust Company, the commissioner of the original “Fearless Girl” sculpture, or State Street Global Advisors Australia or their related entities, in relation to the display of the reproduction of the “Fearless Girl” sculpture.

68 This disclaimer was included as a result of an interlocutory hearing before the primary judge and an undertaking by MBL to include that disclaimer, thereby enabling dissolution of an interim injunction obtained by the appellants on 14 February 2019.

69 While we would accept that the fine print at the foot of the second invitation would not draw the eye, the fact is that the first invitation (with no disclaimer) was not likely to mislead a reasonable reader. This is because it referred to “Australia’s own “Fearless Girl”” which is inconsistent with the notion that the statue to be unveiled is the New York statue. Even if some person had or was likely to have been misled by the first invitation, the primary judge was right at [930] to describe this possible impression as “fleeting and quickly dispelled by subsequent events”.

70 Contrary to the appellants’ submission, the facts underpinning that finding are clear — it is sufficient that the second invitation, issued only two days later, specifically said that the statue is a “limited edition reproduction of the original “Fearless Girl” sculpture in New York created by the artist Kristen Visbal”. Further, the very fact that MBL sent the second invitation to the same people as the first invitation, recorded at [930] of the primary judgment, is itself evidence supporting the inference that those people are likely to have seen the second invitation. In this context, the fact that the invitations show the New York statue in location opposite the Charging Bull statue does not undermine the effectiveness of the message that what is being unveiled is a replica of the New York statue.

71 Knight v Beyond Properties Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 170; (2007) 242 ALR 586 at [53]–[56] does not assist the appellants. In that case the Full Court of the Federal Court accepted the proposition that a “temporary and commercially irrelevant confusion” does not amount to conduct likely to mislead or deceive. In the present case, at worst, it is possible that a recipient of the first invitation might have unreasonably disregarded the message that “Australia’s own Fearless Girl is here!” in large letters and instead focused solely on the reference in small letters to “the iconic Fearless Girl statue” engendering a belief that the statue to be unveiled was the New York statue. Such a belief could not have survived the second invitation only two days later.

Effectiveness of disclaimers (ground 4)

72 This ground does not confront the fact that the primary judge concluded that, irrespective of the disclaimers, the promotional material was not likely to mislead or deceive (as discussed above). Accordingly, while we would accept that the reader’s eye would not be drawn to the disclaimer at the foot of the second invitation, that is immaterial given the primary judge’s other unassailable conclusions and the fact that the second invitation clearly states that the statue is a reproduction. We do not accept that the other disclaimers would not have been perceived and understood by the reasonable reader. The primary judge held that:

(1) the disclaimer on the third invitation was prominent: [941]. We agree;

(2) the attendees at the launch event were invited guests who can be expected to have paid regard to the wording on the billboards in the vicinity of the replica: [941]. We agree; and

(3) with the wrap-around cover in the Herald Sun newspaper and the Stellar magazine advertisement, the use of the disclaimer cannot be said to have been presented in such a way as to accentuate part of the articles complained of: [942]. We agree.

73 The appellants’ assertion that consumers would have only absorbed the general thrust or dominant message conveyed by the promotional material and that message centrally included an association with the New York statue and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign is irreconcilable with the conclusions of the primary judge which involve no error. First, the Australian public did not associate the New York statue with SSGA or the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Second, the association between the MBL replica and the New York statue in the minds of the Australian public was unconnected to SSGA and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Third, the ideas represented by the New York statue (and thus the replica) in the minds of the Australian public were unconnected to SSGA and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Contrary to the appellants’ case there was no “obvious link” between the New York statue, the MBL replica and the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign to sever.

Passing off (grounds 6 and 7)

74 Consistently with the reasoning above, the evidence did not reveal that MBL sought to appropriate SSGA’s goodwill as a result of the SSGA Fearless Girl marketing campaign to benefit its business to the exclusion of SSGA. Australian Woollen Mills v FS Walton & Co Ltd [1937] HCA 51; (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 657 does not assist the appellants. The relevant principle is that:

a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive.

This is no different from the observation above that a subjective intention to mislead may assist in the drawing of an inference that the object or purpose of misleading was achieved. As also observed above, a critical issue in the present case was MBL’s contention, properly accepted by the primary judge given the evidence, that there was a difference between the reputation and associations of the New York statue and the reputation and associations of SSGA and SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign. Given the evidence, the primary judge was also correct that the subjective intentions of MBL, HESTA and Cbus had nothing to do with any association between the New York statue and SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign but were focused on the reputation and associations of the New York statue as a positive symbol of equal opportunity, dignity and respect for women.

75 Accordingly, applying the reasoning in Australian Woollen Mills supports MBL’s case, not that of the appellants. It does so because, as the primary judge recognised at [850], [870], [916], and [918], the idea that MBL would wish to associate itself with SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign is far-fetched. MBL is a law firm priding itself on its reputation for supporting “social justice” and the “we fight for fair” logo, often acting for individual plaintiffs in litigation against “big corporate and government interests”: [850]. SSGA is a big corporate interest, being a Boston based global financial asset manager. SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign, while a call for an important form of gender equality, was focused on increasing the number of women on the boards of big corporations including because SSGA considered that diverse boards led to better outcomes for its investors. As the primary judge rightly recognised (for example at [694]), MBL’s gender equality campaign was about all women and all women in the workplace with a particular focus on equal pay. While MBL’s gender equality campaign also incidentally called for increased women in leadership roles the focus was not on corporate boards or corporate leadership.

76 The appellants’ complaint about the primary judge’s reasoning at [946]–[953], namely that his Honour erred in peremptorily dismissing SSGA’s claim to have suffered damage, cannot be accepted. Those paragraphs deal with damage which is an essential element of the tort of passing off. The paragraphs are obiter dicta because the primary judge concluded that there was no misrepresentation and no relevant reputation in Australia of SSGA or SSGA’s Fearless Girl’s marketing campaign which could have suffered damage. As there is no error in these conclusions, the observations at [946]–[953] are immaterial.

Trade marks (grounds 8 and 9)

77 The appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding that various uses by MBL, HESTA and Cbus of the words “Fearless Girl” were not uses as a trade mark or in the course of trade. According to the appellants these conclusions at [971], [981], [984] and [993] are irreconcilable with the primary judge’s earlier findings at [754]–[774] that the conduct of MBL, HESTA and Cbus was in the course of trade or commerce for the purposes of the claims under the Australian Consumer Law. Further, the primary judge is said to have erred at [983], [991]–[992] in characterising MBL’s use of the words “Fearless Girl” as merely the title of the statue and replica when the uses had a dual character including as a trade mark for MBL’s campaign indicating a connection in the course of trade between the trade mark and the services of MBL, HESTA and Cbus.

78 There is no inconsistency in the reasoning of the primary judge. At [754]–[774], in the context of the claims for misleading and deceptive conduct under the Australian Consumer Law, the primary judge concluded that each of MBL and its campaign partners used the launch event to promote themselves by tying their name to that of Fearless Girl and saw significant value to them in having their businesses and brands associated with the campaign. This does not mean that when each used the words “Fearless Girl” they did so as a trade mark, that is, as a sign to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person: s 17 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Trade Marks Act).

79 The necessary focus is on the use of a sign as an indicator of the origin of the goods or services: Woolworths Ltd v BP plc (No 2) [2006] FCAFC 132; (2006) 154 FCR 97. The statutory proscriptions in ss 120(1) and 120(2) of the Trade Marks Act respectively apply to: (a) use as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered, and (b) use as a trade mark of a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services of the same description as, or that are closely related to, the registered goods or services.

80 There was no dispute that artistic naming conventions require an authorised replica to be given the same title as the original artwork: [807].

81 Take the first invitation as an example. That invitation is reproduced below:

82 There are four uses of “Fearless Girl” on the invitation. It is clear that each use describes the statue. “Australia’s own Fearless Girl” means the replica statue. “The …unveiling of the iconic Fearless Girl statue” means the replica statue. The two uses of “Fearless Girl artist Kristen Visbal” means the creator of the statue. None of the uses can be characterised as distinguishing the origin of the services of MBL, HESTA or Cbus from the services of SSGA as the owner of the “Fearless Girl” trade mark.

83 Another example is the Stellar magazine advertisement which is reproduced below:

84 The reference to “Australia’s own “Fearless Girl”” means the replica statue. To the extent it also refers to MBL’s gender equality campaign by the inclusion of the words “[i]n pursuit of workplace equality” that use is not indicating the origin of the services of MBL, HESTA or Cbus. MBL, HESTA and Cbus were not associating their name with “Fearless Girl” to indicate anything about the origin or source of their services. That was indicated by their names and logos. The association with “Fearless Girl” was not to distinguish their services from those of SSGA or from anyone else, it was to have their brands associated with the positive gender equality reputation of the Fearless Girl statue. This is why at [990] the primary judge rightly distinguished between SSGA’s Fearless Girl marketing campaign to promote its SHE fund and MBL’s campaign to promote gender equality particularly in the workplace. MBL, HESTA and Cbus no doubt also wanted to promote themselves, but they were not offering any service which could resonate with “Fearless Girl” such as SSGA’s SHE fund which is an investment option tracking a gender diversity index consisting of corporations that exhibit gender diversity in leadership positions.

85 Accordingly, the primary judge was also correct to conclude at [1001] and [1002] that a collateral commercial benefit to MBL, HESTA and Cbus does not mean that their uses of the words “Fearless Girl” distinguished their legal and financial services (respectively) from those of any other person in the course of trade. None of MBL, HESTA or Cbus were using “Fearless Girl” to distinguish their services. Rather, their services were distinguished from those of others by their respective logos.

86 For the same reasons we see no error in the primary judge’s approach to the social media posts using the “#fearless girl” hashtag. At [992] the primary judge said:

But when assessing whether the use of the hashtag is use as a trade mark, it is important to have regard to the context of usage. In the context in which it is used, it is clear that MBL’s use of the #fearlessgirl hashtag is not use as a trade mark. In the case of the replica, the hashtag provides a means of identifying the replica in a manner consistent with social media usage, namely, that hashtags used in such a manner identify the topic or subject of a post, not its maker or source.

87 We agree. The social media posts are in the context of the statement “Fearless Girl is coming to Australia”. In that context, “#fearlessgirl” is a reference to the statue and its gender equality associations. MBL is distinguished in the posts by its logo.

Trade marks – class 36 services (grounds 10 and 13)

88 For the same reasons these challenges to the primary judge’ conclusions must fail. While HESTA and Cbus provide financial services which are the same as the registered services, they did not use “Fearless Girl” as a trade mark to distinguish their services.

Trade marks – class 35 services (grounds 11 and 13)

89 SSGA’s trade mark registration also includes class 35 in respect of “publicity services in the field of public interest in and awareness of gender and diversity issues, and issues pertaining to the governance of corporations and other institutions”. The primary judge rejected the appellants’ case that MBL provided publicity services in class 35 under or by reference to the “Fearless Girl” mark: [1027]–[1028].

90 We agree with the primary judge. As his Honour said at [1027], in approaching potential partners in its campaign, MBL was not providing publicity services to those partners. The fact that MBL routinely branded itself as a “leading law firm, not just for individual plaintiff claims but in the area of social justice more broadly” does not mean that MBL provides publicity services (or goods). It may be accepted that MBL wanted its potential co-campaigners to be able to benefit from the campaign for gender equality as much as it wanted to campaign for gender equality, but in seeking co-campaigners MBL was not offering or providing publicity services. It does matter that MBL was a law firm. It was not in the business of providing publicity services, nor did it do so, or offer to do so in the present case. In addition, as we have noted, such services as MBL provided were not by reference to the use of “Fearless Girl” as a trade mark in respect of those services.

Trade marks – good faith use (grounds 12 and 13(b)(ii))

91 The primary judge concluded that the good faith defence in s 122(1)(b)(i) of the Trade Marks Act would apply to the impugned conduct (at [1083]). That section provides that a person does not infringe a registered trade mark when the person uses a sign in good faith to indicate the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or some other characteristic, of goods or services.

92 It must be accepted that the primary judge’s conclusions about s 122(1)(b)(i) depended on his Honour’s earlier conclusions about the use of the words “Fearless Girl” not being use as a trade mark. That is, the primary judge’s reasoning at [1057]–[1082] assumes that his Honour’s earlier conclusions are correct. The reasoning is cumulative upon, and not in the alternative to, those earlier reasons. As we do not consider the primary judge’s earlier conclusions involve any error, there is no scope for s 122(1)(b)(i) to operate, as the section operates “[i]n spite of section 120” (that is, it operates to make what would otherwise be an infringement of a trade mark into a non-infringement of a trade mark).

93 We do not consider it possible for the primary judge or us to purport to consider s 122(1)(b)(i) on a hypothetical basis. The precise content of the hypothesis would affect the application of the requirements of s 122(1)(b)(i). Accordingly, while we would accept that an intention to take advantage of the reputation acquired by another trader or an intention to use another’s trade mark to identify the origin of one’s own goods or services would not be in good faith, those propositions remain disproved hypotheses in the present case.

Trade marks – authorisation (ground 13A)

94 The liability of MBL as a joint tortfeasor with HESTA and Cbus does not arise. The conduct of HESTA and Cbus did not involve any infringement of the trade mark.

Copyright (grounds 14 and 15)

95 The primary judge held that under the master agreement SSGA had a worldwide, exclusive licence to create, use, display and distribute the statue and two-dimensional copies of the statue in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance, the financial services sector, and itself and the products and services it offers or will offer at any time after the effective date: [1112]. That construction of the exclusive licence is unchallenged.

96 However, the primary judge did not accept that the impugned reproductions of the statue were within the scope of SSGA’s exclusive licence: [1131]–[1134]. As the primary judge put it at [1131] the impugned reproductions “do not refer to gender diversity issues in corporate governance or the financial services sector at all”.

97 It is true that MBL’s gender equality campaign was sufficiently broad to encompass equal representation between men and women at board level and in senior positions within organisations: [698]. But the primary judge also correctly found that MBL’s gender equality campaign was not “principally focused on equal representation at board level or about the finance industry” and taking “little snippets and selective aspects of the evidence” which referred to these matters did not transform MBL’s gender equality campaign from one for gender equality including in the workplace into one for equal representation of women and men at board level and in senior positions within organisations: [701].

98 Accepting that a purpose or object (say X) is sufficiently broad to encompass other narrower purposes and objects (say Y) does not mean that the creation, use, display or distribution of a reproduction for purpose or object X is also the creation, use, display or distribution of the reproduction in connection with purpose or object Y. For the reasons explained below, the phrase “in connection with” in the exclusive licence requires a relationship between the creation, use, display or distribution of the reproduction and the exclusive field reserved to SSGA (relevantly, gender diversity issues in corporate governance, and the financial services sector). The issue is the nature of the relationship which the exclusive licence requires in cl 1(a).

99 Clause 1(a) of the exclusive licence must be construed in context, which includes the master agreement providing for the exclusive licence in cl 3(a). Clause 3(a) of the master agreement describes the exclusive rights of SSGA as being to display and distribute reproductions “to promote (i) gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector, and (ii) SSGA and the products and services it offers”. However, the Artist “is free to discuss issues involving Gender Diversity Goals [see below] in connection with the Artwork, provided the Artwork is not used to promote any third party” (the Artwork is defined in the preamble to mean the visual art embodied by the statue of clause 3(a) of the exclusive licence). Further, by cl 3(b) all “uses not licensed to SSGA hereunder are reserved to Artist, subject to the restrictions set forth in Paragraphs 6, 7, 12 and 13 below”. Those restrictions include in cl 7(c)(ii) the Artist not selling, licensing or distributing “copies of the Artwork in any medium or size to any third party to use in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance or in the financial services sector”.

100 There is an important and obvious distinction in the master agreement between the exclusive field granted by the Artist to SSGA and all residual rights otherwise reserved to the Artist. The exclusive field granted to SSGA is in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance, and (on the primary judge’s unchallenged disjunctive construction) the financial services sector. The residual rights otherwise reserved to the Artist include but are not limited to reproductions in connection with the Gender Diversity Goals. Those Gender Diversity Goals are defined in the preamble as supporting “women in leadership positions, empowerment of young women, women’s education, gender equality, the reduction of prejudice in the work place through education, equal pay for women, and the general well-being of women (collectively, the “Gender Diversity Goals”)”. Had the parties intended SSGA’s exclusive licence to extend to reproductions to support the Gender Diversity Goals as a whole, the master agreement and exclusive licence would have said so. The fact that SSGA’s exclusive licence is confined to aspects only of the Gender Diversity Goals (gender diversity issues in corporate governance) indicates that all of the other aspects of the Gender Diversity Goals are outside of the scope of SSGA’s exclusive licence.

101 Accordingly, while “in connection with” generally involves a broad subject-matter relationship (as opposed to causal or temporal), in the context of this agreement with its recognition of broader Gender Diversity Goals, a vague or loose relationship between the use of the reproduction and SSGA’s exclusive field was not within the common contemplation of the parties.

102 It follows that it cannot be the case that a reproduction to promote gender equality generally and equal pay for all women is “in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector” (on a conjunctive construction of cl 1(a) of the exclusive licence) or “in connection with the financial services sector” and thereby within the scope of SSGA’s exclusive licence. If that were so SSGA would have acquired from the Artist the exclusive right in respect of any reproduction to promote any and every possible aspect of gender equality (that is, the Gender Diversity Goals), ranging from childcare availability and educational opportunities to ensure a capacity to work, to the experience of gender diverse individuals in the workplace. It is clear that what SSGA acquired was more limited and should not be expanded by reference to the relational words “in connection with”.

103 For these reasons, “Gender diversity issues in corporate governance”, in context, means the representation of women on the boards and in senior leadership roles of corporations.

104 It is also apparent that on the primary judge’s disjunctive construction of cl 1(a) of the exclusive licence, “[t]he financial services sector”, in context, means the products and services offered by participants in that sector, and not the actions of a participant in that sector in support of causes unconnected to the products and services the participant offers. To explain further the distinction which is being drawn, further regard must be had to the context and text of the master agreement. Relevantly:

(1) SSGA commissioned the statue to promote its financial product, the SHE fund;

(2) under the master agreement, the parties recognised that the exclusive licence granted to SSGA was confined to one aspect only of the broader Gender Diversity Goals (gender diversity issues in corporate governance) and (on the disjunctive construction of cl 3(a)) “the financial services sector”;

(3) cl 7(a) says that the:

Parties acknowledge and agree that use or exploitation of the Artwork by certain third parties, such as third party financial institutions, corporations, or individuals, that may not share the Parties’ Gender Diversity Goals may dilute, tarnish, or otherwise damage SSGA, the SSGA brand, Artist’s reputation, or the integrity of the Artwork.