Federal Court of Australia

Minister for the Environment v Sharma [2022] FCAFC 35

ORDERS

MINISTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT (COMMONWEALTH) Appellant | ||

AND: | ANJALI SHARMA AND OTHERS NAMED IN THE SCHEDULE (BY THEIR LITIGATION REPRESENTATIVE SISTER MARIE BRIGID ARTHUR) Respondents | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 March 2022 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. Before the Court makes orders setting aside orders 1 and 3 made by the primary judge on 8 July 2021 and dismissing the application, the parties should seek to agree further orders necessary to give effect to these reasons for judgment, including any appropriate orders concerning represented parties and as to costs.

3. Within 14 days, the parties file and serve brief written submissions annexing proposed short minutes of order dealing with costs and any further necessary or appropriate order.

4. Final orders will then be determined on the papers and without a further oral hearing, unless a party objects to such a course in writing to the Chambers of the Chief Justice in which case the Court will consider the need for any further hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

Introduction

1 The threat of climate change and global warming was and is not in dispute between the parties in this litigation. The seriousness of the threat is demonstrated by the attention given to it by many countries around the world, and the attempts made by them to reach agreement and to co-operate to reduce the emission of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in order to reduce the rate of increase of the Earth’s surface temperature. Those steps of international diplomacy and international co-operation in scientific matters, including research, have had the consequence that many countries and constituent political parts of countries have adjusted national and regional policy to meet the recognised threat. The debate over the appropriate steps to take at a national and international level has not been without its international and national political controversy.

2 At the outset it is important to appreciate the nature of the proceeding and the basis upon which the case was fought. The evidence led by the respondents (applicants before the primary judge) was not challenged by the appellant, whether by cross-examination or by the leading of contrary or supplementary evidence. This is a matter of some importance. It should not be seen merely as a strategic or tactical choice in a piece of inter partes litigation. This was not a demurrer procedure where the applicants’ case was to be taken at its highest for the purposes of striking out the claim. Evidence was led, on a final basis. Some objections were taken and ruled upon. There was no cross-examination. The appellant is the Minister for the Environment. The Minister is not any litigant. She is the Minister of the Commonwealth responsible, with her Department, for the very type of issue with which the Court was concerned and to which the evidence was directed. There are challenges to some of the primary judge’s findings (which should be rejected), but, by and large, the nature of the risks and the dangers from global warning, including the possible catastrophe that may engulf the world and humanity was not in dispute.

3 The Minister is responsible for decision-making under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (the EPBC Act or the Act). In the discharge of these responsibilities, the Minister is responsible to Parliament (and thereby the Australian people) for the decisions made and the policies implemented in the execution of the laws of the Parliament. The Minister’s decision-making is also subject to judicial review by the courts (the High Court of Australia under s 75(v) of the Constitution and the Federal Court of Australia under, at least, s 39B(1) and s 39B(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth)) for the legality of the decision-making, and of the decisions made, by her. That simple, but basal, structure of responsible and representative parliamentary democracy in which the Executive is subject to the rule of law rooted in s 75(v) of the Constitution and is responsible to the Australian people through Parliament is an important part of the context for the claim. That claim is that apart from, indeed quite distinct from, the subjection to scrutiny for the lawfulness of the decision, the Minister has a personal duty, for breach of which she (and also the Commonwealth), may be found to be personally liable in damages, to take reasonable care, in the execution of her particular duties, powers and functions under ss 130 and 133 of the EPBC Act to avoid causing personal injury or death to all persons who were less than 18 years of age and ordinarily resident in Australia at the time of the commencement of the proceeding in this Court arising from emissions of carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere. Further, in so finding such a duty of care, the primary judge concluded that human safety was a distinct implied mandatory consideration in the decision about a controlled action that might endanger human safety, to be implied from the subject matter, scope and purpose of the EPBC Act.

4 In setting out at the outset the basic constitutional position of the Executive and the role of the Judiciary in pronouncing upon the legality of Executive decision-making, the potential liability of the Commonwealth and its officers in tort is to be recognised, as it is by s 75(iii) of the Constitution. Section 64 of the Judiciary Act recognises that in a suit to which the Commonwealth or a State is a party the rights of parties shall as nearly as possible be the same as in a suit between subject and subject. The law of torts applies to Ministers and the Commonwealth, as much as it applies to ordinary persons or companies. The “aspiration to equality” in s 64 (to use the words of Gleeson CJ in Graham Barclay Oysters Pty Ltd v Ryan [2002] HCA 54; 211 CLR 540 at 556 [12]) recognises within itself that “perfect equality is not attainable”: Gleeson CJ (in the same paragraph)). The nature and responsibilities of government are relevant to the operation of legal principle, here in determining whether a duty of care to avoid personal injury or death is to be recognised. The subjection of governments and public authorities, including Ministers of the Crown, to the rule of law encompasses not only the requirement of legality under s 75(v) of the Constitution, but also liability for tortious wrongs ascertained in accordance with the application of principle under the common law.

5 The EPBC Act takes its place within the federal structure under which the Commonwealth and the States and Territories have co-ordinate, and to a degree overlapping, responsibility and authority in relation to the environment. The EPBC Act, for its own part, is founded in significant part on the translation of international agreements into Commonwealth law. In this regard, it is important to keep in mind that there has been no attempt by the Commonwealth Parliament to translate those international agreements concerning climate change, in particular the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, opened for signature 16 March 1998, 2303 UNTS 162 (entered into force 16 February 2005) or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Paris Agreement 2015 (Paris Agreement) into Commonwealth law. In 2011, Parliament did legislate in relation to climate change issues, the central component being the Clean Energy Act 2011 (Cth). This legislation was repealed on 1 July 2014: Clean Energy Legislation (Carbon Tax Repeal) Act 2014 (Cth). See also the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (Cth); Australian National Registry of Emissions Units Act 2011 (Cth); Australian Renewable Energy Agency Act 2011 (Cth); Clean Energy Finance Corporation Act 2012 (Cth); Greenhouse and Energy Minimum Standards Act 2012 (Cth); and Product Emissions Standards Act 2017 (Cth).

6 Before the time of the hearing of the appeal, but after the primary judge’s decision and orders, the Minister made a decision and granted approval. There was discussion at the hearing as to whether the Court should receive the decision and any reasons. This course was opposed by the respondents. The Court did not receive this material.

The conclusion of the appeal in summary form

7 For the reasons that follow the Minister’s appeal against the imposition of a duty of care in the terms articulated and against the conclusion that human safety was an implied mandatory statutory consideration should be upheld. The latter implication cannot be derived from the EPBC Act. The primary judge’s conclusions in this respect were not sought to be supported by the respondents. The imposition of the duty should be rejected. First, the posited duty throws up for consideration at the point of breach matters that are core policy questions unsuitable in their nature and character for judicial determination. Secondly, the posited duty is inconsistent and incoherent with the EPBC Act. Thirdly, considerations of indeterminacy, lack of special vulnerability and of control, taken together in the context of the EPBC Act and the nature of the governmental policy considerations necessarily arising at the point of assessing breach make the relationship inappropriate for the imposition of the duty. These conclusions reflect differences of view that I have with the evaluative judgments of the primary judge in a field of contention, the imposition of a duty of care in novel circumstances, that is not without difficulty. The primary judge considered and dealt with the arguments of the respondents and the Minister in a careful, thorough and clear body of reasons.

The duty and its framing and its calling forth core policy-making and considerations unsuitable for resolution by the Judicial branch of government

8 In their application at [2] and their concise statement at [22] the respondents sought to express the posited duty at a high level of abstraction: Whether the Minister owed the respondents and the children whom they represented a duty to exercise the power under ss 130 and 133 of the EPBC Act with reasonable care not to cause the respondents harm. The duty was said to arise out of positive action, not omission. Expressed at that high level of abstraction and divorced from concrete facts and referable to any decision under ss 130 and 133 it can be seen to be of little assistance. A postulated duty of care must be stated by reference to the kind of damage that a plaintiff will suffer: John Pfeiffer Pty Ltd v Canny [1981] HCA 52; 148 CLR 218 at 241–242 (Brennan J); Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman [1985] HCA 41; 157 CLR 424 at 487 (Brennan J); Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil [2000] HCA 61; 205 CLR 254 at 262–263 [13]–[16] (Gleeson CJ); Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd [2004] HCA 29; 217 CLR 469 at 472–473 [1] (Gleeson CJ); see also Roads and Traffic Authority of NSW v Dederer [2007] HCA 42; 234 CLR 330 at 345 [43]–[44] (Gummow J) and Sydney Water Corporation v Turano [2009] HCA 42; 239 CLR 51 at 71 [47] (the Court).

9 The scope and content of the duty was illuminated by the expression of its anticipated breach in the concise statement at [23]: To exercise reasonable care not to cause the applicants harm by acting in a manner that materially contributes to increasing the minimum level at which carbon dioxide concentration can flatten. That expression of the matter, taken with the balance of the concise statement and the uncontested evidence presented, informs one that the duty concerns acting in connection with an approval of the extension of a coal mine in the light of the risks of global temperature warming and the consequent risks of harm to humans in the future caused by climate change, by not just the mining and transportation of the coal, but also by the emissions from the combustion of the coal mined from the extension of the mine.

10 The declaration made by the primary judge was in the following terms:

The first respondent has a duty to take reasonable care, in the exercise of her powers under s 130 and s 133 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) in respect of referral EPBC No. 2016/7649, to avoid causing personal injury or death to persons who were under 18 years of age and ordinarily resident in Australia at the time of the commencement of this proceeding arising from emissions of carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere.

11 That expression of the duty omits the express reference to “the material contribution to increasing the minimum level at which [carbon dioxide] concentration can flatten”. The primary judge’s reasons, however, demonstrate that such consideration is embedded within the duty declared and that such matter will be the very subject thrown up for consideration at the point of breach. Further, the duty as expressed in [23] of the concise statement, and the duty declared, is based on the evidence of the contribution of mining the coal to carbon dioxide emissions, not only by the activity of mining and transportation, but also by its combustion. This latter point becomes important as necessarily raising question of policy concerning so-called “Scope 3” emissions to which I will come.

12 The appropriate level of abstraction or focal length of perspective for the proper articulation of the scope and content of the duty is by reference to the whole of the asserted cause of action. As Brennan J said in John Pfeiffer v Canny 148 CLR at 241–242:

His duty of care is a thing written on the wind unless damage is caused by the breach of that duty; there is no actionable negligence unless duty, breach and consequential damage coincide … For the purposes of determining liability in a given case, each element can be defined only in terms of the others.

(emphasis added)

13 As Gleeson CJ said in Cole 217 CLR at 472–473 [1]:

The appellant, having suffered personal injuries, claims that the first respondent is liable to her in damages for negligence … In the circumstances of this case, it is of little assistance to consider issues of duty of care, breach, and damages, at a high level of abstraction, divorced from the concrete facts. In particular, to ask whether the respondent owed the appellant a duty of care does not advance the matter. Before she was injured, the appellant was for some hours on the respondent’s premises, and consumed food and drink supplied by the respondent. Of course the respondent owed her a duty of care. There is, however, an issue concerning the nature and extent of the duty. To address that issue, it is useful to begin by identifying the harm suffered by the appellant, for which the respondent is said to be liable, and the circumstances in which she came to suffer that harm ... As Brennan J said in Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman, ‘‘a postulated duty of care must be stated in reference to the kind of damage that a plaintiff has suffered’’. The kind of damage suffered is relevant to the existence and nature of the duty of care upon which reliance is placed. Furthermore, a description of the damage directs attention to the circumstances in which damage was suffered. ‘‘Physical injury’’, or ‘‘economic loss’’, may be an incomplete description of damage for the purpose of considering a duty of care, especially where, as in the present case, the connection between the acts or omissions of which a victim complains and the damage that she suffered is indirect.

(emphasis added, footnotes omitted)

14 The importance of the articulation of the nature and extent or scope and content of the posited duty (here, illuminated by [23] of the concise statement and by the declaration made) is that, if one posits the duty by reference to the asserted breach and the closely related evidence led to reveal the risk of harm, in order to decide the questions of the existence of the duty and of breach one is necessarily taken to consider all the evidence, material, policy and other considerations that attend the decision and that involve the question of the proper response to, including the adequacy of governmental policy in relation to, the risks of the emissions from the combustion of the coal mined as part of the worldwide risks of global warming and climate change. If one leaves the duty expressed at the high level of abstraction in [2] of the application or [22] of the concise statement one might well respond: Yes of course, but what are the circumstances? Possibly (though the Minister’s submissions contest the proposition) there could be a duty upon the Minister faced with the question of an approval of a mine of some description or of some other controlled action near a centre of urban population to exercise reasonable care for the health and safety of the nearby residents in exercising the power to approve or not approve the mine or controlled action, and if the former, on what conditions. Considerations and dangers in such a case might be so direct, so well understood, so immediately proximate, and attended by considerations in respect of which the court was entirely suited to adjudicate.

15 The question of duty is not to be placed at such a level of abstraction or generalisation as to elicit such an unhelpful response as yes, but depending on the facts, thereby leaving the real controversy and contest to breach. The duty here, however, is framed by reference to contributing to carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere by the combustion of the coal mined. That duty throws up for consideration at the point of assessing breach the question of the proper policy response to climate change and considerations unsuitable for resolution by the Judicial branch of government. In particular, the duty throws up at the point of assessing breach the question whether, and if so, how so-called Scope 3 emissions from the combustion of the coal that is to be exported should be or should have been taken into account in making a decision about whether to approve the extension of a coal mine, when the statutory focus and concern of the decision is the protection of identified species and communities of fauna and water resources. A duty that calls up such questions should not be imposed: It is one of core, indeed high, policy-making for the Executive and Parliament involving questions of policy (scientific, economic, social, industrial and political) which are unsuitable for the Judicial branch to resolve in private litigation by reference to the law of torts and potential personal responsibility for indeterminate damages, if harm eventuates in decades to come.

16 Later in these reasons, I will refer to other parts of the judgment of Gleeson CJ and of other members of the High Court in Graham Barclay Oysters 211 CLR 540. It is appropriate, however, at the outset to set out what the Chief Justice said at 553–554 [6], which is, in my view, the central framing consideration in this case that transcends any distinction between acts and omissions:

Citizens blame governments for many kinds of misfortune. When they do so, the kind of responsibility they attribute, expressly or by implication, may be different in quality from the kind of responsibility attributed to a citizen who is said to be under a legal liability to pay damages in compensation for injury. Subject to any insurance arrangements that may apply, people who sue governments are seeking compensation from public funds. They are claiming against a body politic or other entity whose primary responsibilities are to the public. And, in the case of an action in negligence against a government of the Commonwealth or a State or Territory, they are inviting the judicial arm of government to pass judgment upon the reasonableness of the conduct of the legislative or executive arms of government; conduct that may involve action or inaction on political grounds. Decisions as to raising revenue, and setting priorities in the allocation of public funds between competing claims on scarce resources, are essentially political. So are decisions about the extent of government regulation of private and commercial behaviour that is proper. At the centre of the law of negligence is the concept of reasonableness. When courts are invited to pass judgment on the reasonableness of governmental action or inaction, they may be confronted by issues that are inappropriate for judicial resolution, and that, in a representative democracy, are ordinarily decided through the political process. Especially is this so when criticism is addressed to legislative action or inaction. Many citizens may believe that, in various matters, there should be more extensive government regulation. Others may be of a different view, for any one of a number of reasons, perhaps including cost. Courts have long recognised the inappropriateness of judicial resolution of complaints about the reasonableness of governmental conduct where such complaints are political in nature.

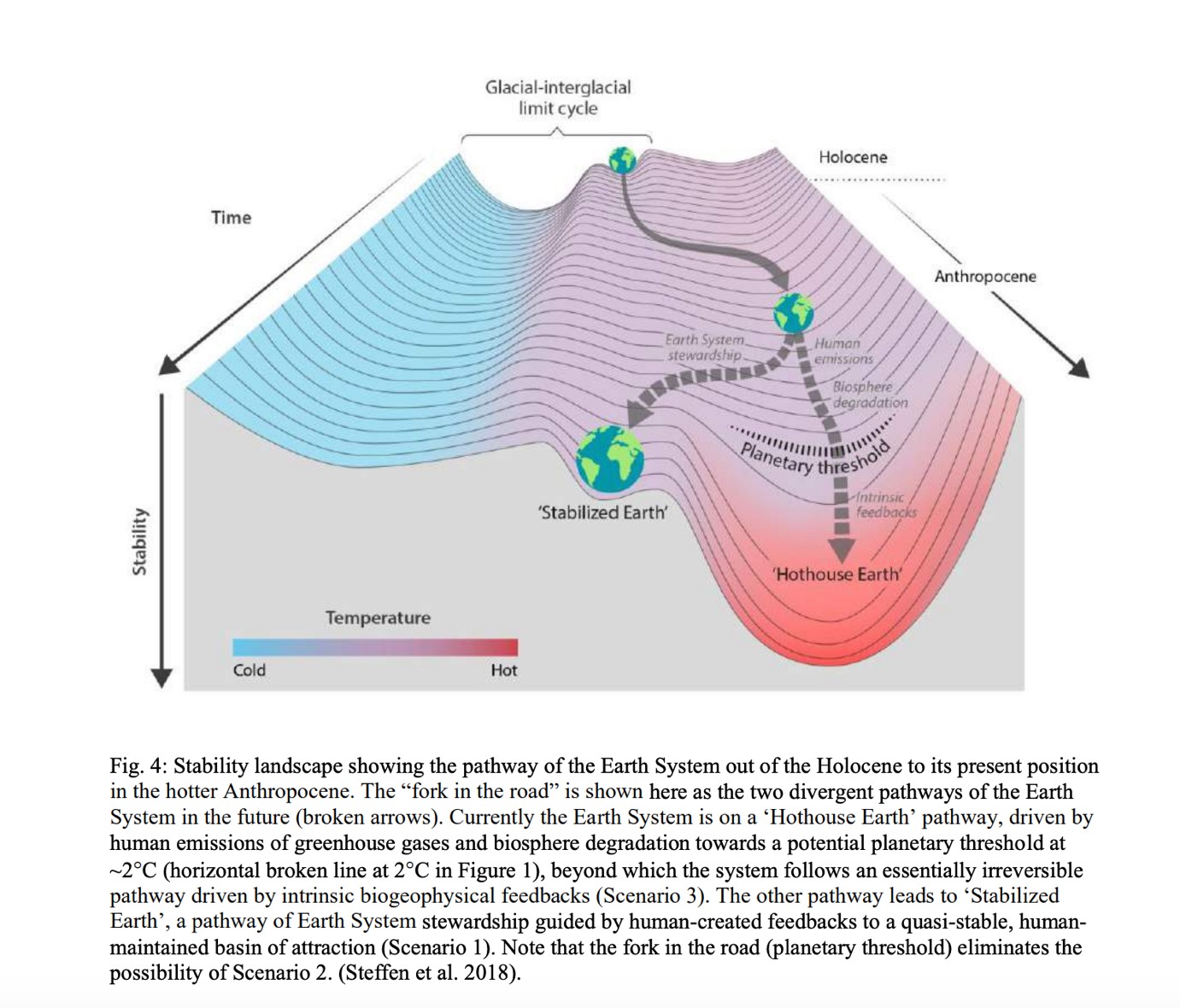

17 The central error of the primary judge, in my respectful view, was to marginalise such questions and considerations as a miscellaneous control mechanism and as not relevant (see J[474]–[485]), and to construct the duty by individual analysis of salient features commencing with the risk of harm, assuming the matters thrown up by the duty were suitable for judicial determination as in any other tort case. That was the approach urged on his Honour and on this Court by the submissions of the respondents (applicants below). The submissions went so far (at least before us) that, it was said, to hold that the duty should not be imposed because it raised core policy-making and involved considerations unsuitable for judicial determination would be to abrogate judicial responsibility under Chapter III of the Constitution to quell controversies between subject and government and to introduce a “political question” doctrine foreign to Australian Constitutional government and the rule of law within it. That submission should be rejected by reference to cases of the highest binding authority. That which follows, especially [206]–[272] and [291]–[293], is an elaboration and explanation of the above. The immanent and central proposition for the existence of a duty of care, based on the central thesis of Professor Steffen, is that science dictates that for the Minister not to endanger the Children requires a re-evaluation and change to any government policy on climate change that remains fixed within the parameters of the Paris Agreement and the treatment of Scope 3 emissions.

The structure of these reasons

18 I approach the explanation of why the posited duty of care should not be imposed by dealing with the following:

The immediate factual context of the decision of the Minister: [19]–[42]

The statutory framework of the decision of the Minister: [43]–[92]

The legislative context of the EPBC Act: [93]–[98]

The reasons of the primary judge: [99]–[176]

The Minister’s grounds of appeal and submissions: [177]–[187]

The respondents’ submissions: [188]–[205]

Consideration and determination: [206]–[346]

Introduction: [206]–[213]

Grounds 2(a) and (b): human safety is not an implied mandatory consideration in the EPBC Act: [214]–[217]

The relationship between the Minister and the respondents and the class: [218]–[232]

The EPBC Act, core policy and incoherence: grounds 1 and 2(c): [233]–[272]

Challenge to the factual findings in ground 5: [273]–[290]

Coda to ground 5: [291]–[293]

The law of negligence: reasonable foreseeability and causation, control, vulnerability and reliance, and indeterminacy: grounds 3 and 4: [294]–[343]

Conclusion: [344]–[346]

Orders: [347]

The immediate factual context of the decision of the Minister

19 Vickery Coal Pty Ltd is a subsidiary of Whitehaven Coal Pty Ltd which holds development consent under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) (the EPA Act) for a coal mine in northern New South Wales near Gunnedah. No mining has commenced under the approval. In February 2016, Whitehaven applied under s 68 of the EPBC Act to the Minister to expand the existing approved project for coal mining. In July 2018, Vickery replaced Whitehaven as the proponent for the application. The extension of the mine would increase total coal extraction from the mine from 135 million to 168 million tonnes (Mt), that is by 33 Mt which, when combusted, would produce 100 Mt of carbon dioxide (CO2).

20 The application for an extension will not only increase the total coal extracted from the mine, but also increase the rate of extraction from 4.5 to 10 Mt per year, increase the area of land disturbed by mining, and there will be a new coal handling and preparation plant and rail facility at the site. The extension project itself will cause directly or indirectly emissions of greenhouse gases, especially CO2.

21 The Minister came to be concerned with the approval of the extension of the mine because on 14 April 2016 a delegate of the Minister determined that the extension of the mine was a “controlled action” under s 75(1) of the EPBC Act. The delegate decided that the relevant controlling provisions were ss 18 and 18A concerned with listed threatened species and communities and ss 24D and 24E concerned with a water resource, in relation to coal seam gas development and large coal mining development. The assessment approach was to be under the bilateral agreement with New South Wales, an approach provided for by the EPBC Act. The initial project had been approved as a “State Significant development” under the EPA Act and a delegate of the Minister had determined that it was not a “controlled action” under s 75. So the initial project being a little over four times larger than the extension did not involve the Minister under the EPBC Act.

22 As a consequence of the extension of the mine being a controlled action, the Minister was required to approve or not approve the application under ss 130(1) and 133 of the EPBC Act. The duty was binary: to approve or not, though, as will be seen, there was a power to attach some conditions. The EPBC Act requires that prior to that approval the matter be assessed. One method of assessment provided for by the EPBC Act (used in this case) was pursuant to bilateral agreement with the relevant State, here New South Wales. In May 2020, the New South Wales Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (the NSW Department) provided its assessment report to the Independent Planning Commission of New South Wales (the IPC), in the context of the Minister for Planning and Public Spaces (the State Minister) directing the IPC (under s 2.9(1)(d) of the EPA Act) to conduct a further public hearing concerning the extension of the mine with particular attention to the assessment report and any relevant public submissions. In August 2020, the IPC, after conducting a further public hearing as directed, granted development consent for the extension project. The report of the department and the reasons in the report of the IPC were provided to the Minister.

23 The IPC received a significant body of evidence during the public hearing, including a report of Professor Steffen that was in substantial accordance with the evidence led before the primary judge.

24 The two reports (of the NSW Department and the IPC) were prepared under the relevant State legislation, primarily the EPA Act. Under that statutory framework it was mandatory for the NSW Department and IPC to consider the question of greenhouse gases, including under the framework of the public interest: see s 4.15(1)(e) of the EPA Act. As discussed below, there is nothing in the EPBC Act which required the Minister to consider greenhouse gas emissions or global warming or climate change. The Minister’s necessary statutory focus was on the considerations concerned with listed threatened species and communities and the water resource in question. An approval of the extension would have greenhouse gas emissions consequences as discussed below, but they did not bear directly or indirectly upon the matters to which the Minister was directed by the EPBC Act. They did, however, bear directly upon the decision of the State Minister and upon the reports of the NSW Department and of the IPC.

25 The extension of the mine, being a development for the purpose of mining, was a “State significant development” under New South Wales legislation (s 4.36 of the EPA Act, as specified by cl 8 and cl 5 of Sch 1 of the State Environmental Planning Policy (State and Regional Development 2011 (NSW) (the SRD SEPP)). Pursuant to s 4.38 of the EPA Act, a consent authority is required either to grant (with or without modifications or conditions) or refuse consent to a development application concerning a State significant development. By operation of s 4.5(a) of the EPA Act and cl 8A(1)(b) of the SRD SEPP (due to over 50 public submissions objecting to the extension being provided to the NSW Department), the IPC became the designated consent authority. Under s 4.6(b) of the EPA Act, certain functions of the IPC are to be exercised by the Planning Secretary, including “undertaking assessments of the proposed development”, which provided the basis for the NSW Department preparing the assessment report for the IPC.

26 Unlike the requirements imposed on the Minister under the EPBC Act, the IPC as the consent authority (and as is reflected in the NSW Department’s report and the IPC’s reasons) was required specifically to consider the impact of the extension of the mine on greenhouse gas emissions and the risks to the environment and human consequences thereof. The evaluative task imposed by s 4.15 (applicable by operation of s 4.40) required the IPC to consider, among other things: the likely “environmental impacts on both the natural and built environment” (s 4.15(b)); the public interest (s 4.15(e)) (which requires consideration of the relevant objects of the EPA Act, including promoting the social and economic welfare of the community and a better environment (s 1.3(a)) and the principle of ecologically sustainable development (s 1.3(b))); and the provisions of any applicable environmental planning instrument (s 4.15(1)(a)(i)), which includes the State Environmental Planning Policy (Mining, Petroleum Production and Extractive Industries) 2007 (NSW) (the Mining SEPP). The Mining SEPP specifically required the IPC to “consider an assessment of the greenhouse gas emissions (including downstream emissions) of the development … having regard to any applicable State or national policies, programs or guidelines concerning greenhouse gas emissions” (cl 14(2)) and to consider whether or not consent should be granted with an aim to ensuring “that greenhouse gas emissions are minimised to the greatest extent practicable” (cl 14(1)(c)). The phrase “downstream emissions” encompassed the consequences of combusting or burning the coal mined.

27 The two reports considered the question of greenhouse gas emissions. In the Executive Summary of the report of the NSW Department the following appeared under the heading “Greenhouse Gas Emissions”:

The Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions of the Project have been assessed on a cumulative basis incorporating the Approved Project, but consideration has been given to the additional impacts over and above those associated with the Approved Project for comparative purposes.

The main sources of Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions from the Project are from electricity consumption, fugitive emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), diesel usage, and the transport and end use of product coal.

The Project would generate approximately 3.1 Mt carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) of Scope 1 emissions, 0.8 Mt Scope 2 and 366 Mt CO2-e Scope 3 emissions.

In comparison to the Approved Project, there would be a reduction of about 1 Mt CO2-e of Scope 1 emissions, increase of about 0.15 Mt CO2-e Scope 2 emissions and an increase of about 100 Mt CO2-e of Scope 3 emissions over the life of the Project. The reduction in Scope 1 GHGE can be partially attributed to the inclusion of the Project CHPP, rail loop and rail spur, due to reduction in the consumption of diesel fuel associated with ROM coal haulage by truck to the Gunnedah CHPP.

The Project’s Scope 1 emissions would contribute to about 0.028% of Australia’s current annual GHG emissions and would remain a very small contribution when compared to Australia’s commitments under the Paris Agreement, as identified in the Commonwealth government’s nationally determined contribution (NDC).

The Department acknowledges that the Scope 3 emissions from the combustion of product coal is a significant contributor to anthropological climate change and the contribution of the Project to the potential impacts of climate change in NSW must be considered in assessing the overall merits of the development application.

However, the Department notes that the Project’s Scope 3 emissions would not contribute to Australia’s NDC, as product coal would be exported for combustion overseas. These Scope 3 emissions become the consumer countries Scope 1 and 2 emissions and would be accounted for in their respective national inventories.

Importantly, the NSW or Commonwealth Government’s current policy frameworks do not promote restricting private development as a means for Australia to meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement or the long-term aspirational objective of the NSW Government’s Climate Change Policy Framework. Neither do they require any action to taken by the private sector in Australia to minimise or offset the GHG emissions of any parties outside of Australia, including the emissions that may be generated in transporting or using goods that are produced in Australia.

Overall, the Department considers that the GHG emissions for the Project have been adequately considered and that, with the Department’s recommended conditions, are acceptable when weighed against the relevant climate change policy framework, objects of the EP&A Act (including the principles of Ecologically Sustainable Development) and socio-economic benefits of the Project.

The Department has recommended conditions to manage the GHG emissions of the Project, including requiring Whitehaven to:

• take all reasonable steps to improve energy efficiency and reduce Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions for the Project; and

• prepare and implement an Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Management Plan, including proposed measures to ensure best practice management is being employed to minimise the Scope 1 and 2 emissions of the Project.

(emphasis added)

28 In the detailed body of the report is the section dealing with the “public interest”. That public interest was described in [670] of the report as consideration of the objects of the State environmental legislation, including the principles of environmentally sustainable development, greenhouse gas emissions having regard to relevant climate change policy frameworks, and the (international) demand for coal and whether its sale would be to a country that is a signatory to the Paris Agreement.

29 Critical to the analysis and conclusions drawn in the report was the division of the emissions into Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. The protocols employed were of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and the World Resources Institute. By that method of analysis Scope 3 emissions from the burning of the coal were part of the Scope 1 emissions of the country where the coal is combusted.

30 The coal to be mined in the extension of the mine was for export to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

31 At [683]–[715] the report considered “Climate Change Policy Consideration”. The report recognised that the requirements under cll 14(1) and 14(2) of the Mining SEPP to consider whether conditions should be attached to ensure the development is undertaken to minimise greenhouse gas emissions to the greatest extent possible (see [683]) and to consider an assessment of greenhouse gas emissions (including downstream emissions, which would include emissions from the combustion of the coal), such consideration to have regard to State or national policies, programs, or guidelines concerning greenhouse gas emissions (see [684]). Two key policy documents were identified (at [685]) for this assessment: the “Climate Change Policy Framework” of the New South Wales Government (CCPF) and the Commonwealth Government’s commitments to the Paris Agreement. In addition to these two policy frameworks, the report noted (at [686]) the State’s recently announced (March 2020) plan for net zero emissions by 2050 and a 35% cut in 2005 emissions by 2030.

32 At [688] the report described the State’s policy under the CCPF, as follows:

… The CCPF does not set prescriptive emission reduction targets and sets policy directions for government action, for example, to improve opportunities for private sector investment in low emissions technology in the energy industry, which is needed for a transition to a net-zero emissions inventory.

33 The report stated (at [689]) that the project was not inconsistent with the CCPF, by reference to Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions.

34 The report then considered the Paris Agreement and Australia’s obligations and commitments thereunder and thereto. The evident important consideration recognised by the report was Scope 3 emissions. The importance of Scope 3 emissions and their place in the State, Commonwealth and international policy frameworks (the last being the Paris Agreement) can be seen in [692]–[696]:

692. The Department acknowledges that the Scope 3 emissions from the combustion of product coal is a significant contributor to anthropological [sic] climate change and the contribution of the Project to the potential impacts of climate change in NSW must be considered in assessing the overall merits of the development application.

693. Importantly, the Project’s Scope 3 emissions would not contribute to Australia’s NDC [nationally determined contributions], as product coal would be exported for combustion overseas. These Scope 3 emissions become the consumer countries Scope 1 and 2 emissions and would be accounted for in their respective national inventories.

694. A regular 5-yearly review of NDCs is required under the Paris Agreement with the next review to be submitted by signatories in 2020. The Department acknowledges that ongoing review to meet emission targets by signatories may affect export markets for coal and that the UNFCCC global approach to nationally determined emission reduction targets is the appropriate mechanism for managing Australia’s Scope 3 emissions, rather than regulating Scope 3 emissions on a project by project basis in Australia.

695. The Department also notes that the Department’s ‘Guidelines for Economic Assessment of Mining and Coal Seam Gas Proposals’ and the associated 2018 technical notes do not require the social cost of Scope 3 emissions to be incorporated into the economic evaluation when determining the net benefits to NSW or Australia of the development. This approach, where both the costs and benefits of consumption and use of the coal is considered by the country/ development where the coal is being used, is consistent with the global accounting framework for GHG emissions under the UNFCCC.

696. Importantly, the NSW or Commonwealth Government’s current policy frameworks do not promote restricting private development as a means for Australia to meet its commitments under the Paris Agreement or the long-term aspirational objective of the CCPF guidelines. Neither do they require any action to [sic] taken by the private sector in Australia to minimise or offset the GHG emissions of any parties outside of Australia, including the emissions that may be generated in transporting or using goods that are produced in Australia.

35 The place of Scope 3 emissions in Commonwealth policy was made clear in the report at [697] in which a letter from the Commonwealth Minister to her State counterpart expressing Commonwealth Government policy was quoted as saying:

… “any requirement to consider scope three emissions within a sub-national or state jurisdiction is inconsistent with long accepted international carbon accounting principles and Australia’s international commitments”.

36 The report went on to explain (at [701]–[706]) why Scope 3 emissions should not be relevant:

701. There is no NSW or Commonwealth policy that supports placing conditions on an applicant to minimise the Scope 3 emissions of its development. Any such policy is likely to result in significant implications for the NSW and Australian economy and it is not clear it would have any effect on reducing GHG emissions generated by parties in other jurisdictions outside Australia. Further, conditions must be for a proper planning purpose, must fairly and reasonably relate to the subject development, and must not be manifestly unreasonable.

702. On this basis the Department has recommended conditions requiring Whitehaven to take all reasonable steps to improve energy efficiency and reduce Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions for the Project and to prepare and implement an Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Management Plan, including a requirement to apply best practice to minimise the Scope 1 and 2 emissions of the Project.

703. The Department also acknowledges that GHG emissions have attracted additional attention following a February 2019 judgement in the Land and Environment Court (Rocky Hill appeal – [Gloucester Resources Limited vs Minister for Planning] (2019 NSWLEC 7) and the Commission’s subsequent decisions relating to GHG emissions in coal mining projects, including the refusal of Bylong Coal Project and inclusion of conditions relating to Scope 3 GHG emissions for the United Wambo Open Cut Coal Mine.

704. In its Statement of Reasons for Decision for the Rixs Creek Continuation of Mining Project (SSD 6300), the Commission noted that the Applicant for the Rixs Creek Project does not have direct control over Scope 3 emissions and accepted that Scope 3 emissions were the responsibility of the end customer for coal export. The Commission also noted that coal consumption in countries which are signatories to the Paris Agreement, or have enforced GHG reduction targets (such as Taiwan) would lead buyers to seek coal products which meet their product requirements and would also minimise GHG emissions to achieve domestic emission reduction targets.

705. The NSW Government has since introduced a Bill into Parliament (Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill 2019). The Bill was introduced in response to recent planning decisions and seeks to clarify that conditions under EP&A Act can only be imposed if they relate to impacts occurring within Australia or its external territories.

706. This aligns with the intent that development consent conditions set and enforced in the NSW planning system are not an appropriate mechanism to control the impacts resulting from the activities of third parties in other countries.

37 The report then considered (at [707]–[710]) the international demand for coal, as follows:

707. The Project would produce metallurgical coal (around 70% of the product coal) including semi-soft coking coal, pulverised coal injection (PCI) coal and thermal coal (around 30% of the product coal) to supply Whitehaven’s main export market customers in Japan, the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the Republic of China (Taiwan).

708. Japan and South Korea are signatories to the Paris Agreement and have developed GHG emission reduction targets, which would be managed under the NDCs of these countries. Taiwan is not a signatory to the Paris Agreement but has developed its own GHG emission reduction targets (enforced under its Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act) that are comparable to those of countries who are signatories.

709. Whitehaven recognises that global coal demands are shifting and has provided an economic sensitivity analysis (see Section 6.8 – Economic Evaluation) to account for changing trends in forecast coal pricing and demand. The sensitivity analysis shows that significant net benefits would accrue to NSW over a range of assumptions for coal prices, discount rates, exchange rates and employment related benefits.

710. The Department notes that the majority of the coal is of metallurgical quality and that the thermal coal quality is a high calorific/ low ash/ low sulphur coal which is in stronger demand globally compared to lower quality (high ash/ high sulphur) coal. Whitehaven provided the Department with further information (see Appendix G6-10) on the Project’s coal quality relative to anticipated demand based on the three climate changes scenarios contemplated by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in its World Energy Outlook 2019. Under the Sustainable Development Scenario there would continue to be demand for high quality (low ash/ low sulphur/ high calorific energy) thermal and metallurgical coal, particularly in the Asia Pacific region, as provided by the Vickery coal resource.

38 Explicit in the above is an approach based on State and Commonwealth public policy stated to be conformable with international convention (the Paris Agreement) and in part reduced to State legislation that Scope 3 emissions are a matter for the countries buying and combusting the coal which have emission targets conformable with international treaty.

39 Appendix J to the report concerned matters relevant to the Minister’s decision under the EPBC Act. It dealt with impacts on listed species and communities in section J.1. This included the likely impact of certain native vegetation clearing on listed species and communities of fauna, including birds, koalas, bats and fish. Section J.2 dealt with offsetting impacts. Sections J.3 to J.6 dealt with other matters required to be considered under the EPBC Act. At s J.7 conclusions were set out on the controlling provisions as follows:

Threatened species and communities (Sections 18 and 18A of the Act)

For the reasons set out in Section 6.2, Appendix I and this Appendix, the Department recommends that the impacts of the action would be acceptable, subject to avoidance, mitigation measures described in Whitehaven’s EIS, Submissions Report and additional advice provided to the Department and the recommended conditions of consent in Appendix L.

A water resource, in relation to coal seam gas development and large coal mining development (Sections 24D and 24E of the Act)

For the reasons set out in Section 6.2 and this Appendix, the Department recommends that the impacts of the action on a water resource, in relation large coal mining development would be acceptable, subject to the avoidance, mitigation measures described in Whitehaven’s EIS, Submissions Report and the requirements of the recommended conditions of consent in Appendix L.

40 In appendix K, the NSW Department considered various aspects of the EPA Act requirements. Amongst these were “intergenerational equity”. The report stated in appendix K about this matter the following:

Intergenerational equity has been addressed through maximising efficiency and coal resource recovery and developing environmental management measures which are aimed at ensuring the health, diversity and productivity of the environment are maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations.

The Department acknowledges that coal and other fossil fuel combustion is a contributor to climate change, which has the potential to impact future generations. However, the Department also recognises that there remains a clear need to develop coal deposits to meet society’s basic energy requirements for the foreseeable future. The proposal includes measures to mitigate potential GHGE’s from the operation of the Project, which would be recommended as a requirement of the Project’s operating conditions and detailed in an Air Quality and Greenhouse Gas Management Plan.

The Department’s assessment of direct energy use and associated GHGE’s (ie Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions) has found that these emissions would be low and comprise a very small contribution towards climate change at both the national and global scale (see Section 6.10).

The Department considers that the socio-economic benefits and downstream energy generated by the Project would benefit future generations, particularly through the provision of national and international energy needs in the short to medium term.

41 The report of the IPC reviewed the Department’s report. It similarly categorised the greenhouse gas emissions into Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. A public hearing was conducted. The submissions of members of the public expressed concern as to the total amount of greenhouse gas emissions from the extension and the project, including Scope 3 emissions. The IPC made its findings, consistent with Australia’s non-responsibility for Scope 3 emissions, saying at [215]–[216] and [220]–[223], as follows:

215. The Commission acknowledges that the aim of the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework (CCPF) is to “maximise the economic, social and environmental wellbeing of NSW in the context of a changing climate and current and emerging international and national policy settings and actions to address climate change” with an aim to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 and to ensure NSW is more resilient to a changing climate. The Commission notes that the CCPF does not set prescriptive emission reduction targets and sets policy directions for government action as stated by the Department in paragraph 207 above. The Commission also notes that the NSW Government released the Net Zero Plan Stage 1: 2020–2030 (Net Zero Plan) in March 2020 as referenced by the Department in paragraph 208 above. The Commission notes that the Net Zero Plan builds on the CCPF and sets out a number of initiatives to deliver a 35% cut in emissions by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. The Commission agrees with the Department’s assessment, in paragraph 207 above that the Project is not inconsistent with the CCPF and that the Applicant has committed to minimising its Scope 1 emissions over which it has direct control.

216. The Commission notes that, under the Paris Agreement, the Australian Government committed to a nationally determined contribution (NDC) to reduce national GHG emissions by between 26 and 28 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. The Commission also notes that Australia does not require monitoring or reporting of Scope 3 emissions under the NGERS [National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme] and they are not counted in Australia’s national inventory of GHG emissions under the Paris Agreement. The Commission agrees with the Department’s statement in paragraph 209 above that the Project’s Scope 3 emissions would not contribute to Australia’s NDC, as product coal would be exported overseas. The Commission notes that these Scope 3 emissions become the consumer countries’ Scope 1 and 2 emissions and would be accounted for under the Paris Agreement in their respective national inventories.

…

220. The Commission has acknowledged that the concerns raised by the public in paragraphs 188 to 191 above, including submissions made by the BFCG [Boggabri Farming and Community Group] in relation to the burning of fossil fuels as an energy resource and meeting the Paris Agreement climate targets. The Commission notes that the ‘carbon budget’ approach suggested in some submissions is not endorsed by the Paris Agreement, the Australian Government or the NSW Government. Furthermore, neither the Australian nor NSW Government have indicated that the development of new coal mines or the expansion of existing mines be prohibited or restricted in any way for the purpose of achieving Australia’s NDC.

221. The Commission agrees with the Department’s statement in paragraph 209 above and acknowledges that Scope 3 emissions from the combustion of product coal are a significant contributor to anthropological [sic] climate change and that the contribution of the Project to the potential impacts of climate change in NSW must be considered in assessing the overall merits of the development application.

222. The Commission notes that between 60-70% of the coal proposed to be extracted is likely to be metallurgical coal, with the remainder being thermal coal as stated above by the Applicant in paragraph 200 and by the Department in paragraph 205 of this report. The Commission notes that at this point in time, metallurgical coals are essential inputs for the current production of approximately 70% of all steel globally as stated by the Applicant in paragraph 200 above. The Commission is of the view that in the absence of a viable alternative to the use of metallurgical coal in steel making and on balance, the impacts associated with the emissions from the combustion of the project’s metallurgical coal are acceptable. The Commission also notes that the coal proposed for extraction is anticipated to be of a relatively high quality, as stated above by the Applicant in paragraph 194 and Department in paragraph 204. The Commission notes the Applicant’s statement in paragraph 194 above that the use of higher quality coal may result in lower pollutants.

223. For the reasons set out above, the Commission is of the view that the GHG emissions for the Project have been adequately considered. The Commission finds that on balance, and when weighed against the relevant climate change policy framework, objects of the EP&A Act, ESD principles (section 4.10) and socio-economic benefits (section 4.9.6), the impacts associated with the GHG emissions of the Project are acceptable and consistent with the public interest. The Commission therefore imposes the Conditions B35, B36 and B37 as recommended by the Department.

(emphasis added)

42 The Minister thus came to her responsibility to decide whether to approve the application.

The statutory framework in the EPBC Act of the decision of the Minister

43 The statutory framework of the Minister’s decision needs to be explained. I will begin with the text of the statute. It is, however, necessary to say something of the context of the EPBC Act, in particular its passing as an expression of the agreement amongst governments of the federation to co-operate in their shared responsibilities in respect of the environment.

44 At the outset of this explanation it is appropriate to emphasise a point (correctly) submitted by the Minister to be central to the resolution of the controversy. The EPBC Act is not concerned generally with the protection of the environment. Nor is there any part of the EPBC Act that is expressly concerned with greenhouse gases, global warming or climate change. Using such Constitutional foundations as are available, most importantly the external affairs power in the implementation of conventions and international agreements (s 51(xxix) of the Constitution), the Parliament has directed the EPBC Act to nine “matters of national environmental significance”. In respect of some, but not all, of these matters the environment (as widely defined) is a relevant consideration. The two matters of national environmental significance which were the subject of the Minister’s concern and decision were listed endangered species and communities and the water resource. As will be seen, the environment generally (as widely defined) was not an express consideration in respect of those matters. Yet, it was only by the exercise of the power to approve the extension, derived from the duty to approve or refuse the application, by reference to the particular matters of concern (species, communities and water resource) that the question, called forth by the posited duty, of the affectation of the environment generally by emission of greenhouse gases arose. The decision for the Commonwealth Minister was not concerned with greenhouse gas emissions, although the State decision was so concerned. The duty of care was said to arise because the power to approve amounted to the effective grant of a licence to carry on activity which involved the foreseeable risk of personal injury or death to the respondents.

45 The objects of the EPBC Act are set out in s 3(1) as follows:

(1) The objects of this Act are:

(a) to provide for the protection of the environment, especially those aspects of the environment that are matters of national environmental significance; and

(b) to promote ecologically sustainable development through the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of natural resources; and

(c) to promote the conservation of biodiversity; and

(ca) to provide for the protection and conservation of heritage; and

(d) to promote a co‑operative approach to the protection and management of the environment involving governments, the community, land‑holders and indigenous peoples; and

(e) to assist in the co‑operative implementation of Australia’s international environmental responsibilities; and

(f) to recognise the role of indigenous people in the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of Australia’s biodiversity; and

(g) to promote the use of indigenous peoples’ knowledge of biodiversity with the involvement of, and in co‑operation with, the owners of the knowledge.

46 The word “environment” (see ss 3(1)(a) and Ch 2) is defined in broad terms in s 528 of the EPBC Act as including:

(a) ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities; and

(b) natural and physical resources; and

(c) the qualities and characteristics of locations, places and areas; and

(d) heritage values of places; and

(e) the social, economic and cultural aspects of a thing mentioned in paragraph (a), (b), (c) or (d).

47 The phrase “ecologically sustainable use” (in para 3(1)(b)) is defined in s 528 as follows:

ecologically sustainable use of natural resources means use of the natural resources within their capacity to sustain natural processes while maintaining the life‑support systems of nature and ensuring that the benefit of the use to the present generation does not diminish the potential to meet the needs and aspirations of future generations.

48 Subsection 3(2) sets out how the EPBC Act seeks to achieve these objects:

(2) In order to achieve its objects, the Act:

(a) recognises an appropriate role for the Commonwealth in relation to the environment by focussing Commonwealth involvement on matters of national environmental significance and on Commonwealth actions and Commonwealth areas; and

(b) strengthens intergovernmental co‑operation, and minimises duplication, through bilateral agreements; and

(c) provides for the intergovernmental accreditation of environmental assessment and approval processes; and

(d) adopts an efficient and timely Commonwealth environmental assessment and approval process that will ensure activities that are likely to have significant impacts on the environment are properly assessed; and

(e) enhances Australia’s capacity to ensure the conservation of its biodiversity by including provisions to:

(i) protect native species (and in particular prevent the extinction, and promote the recovery, of threatened species) and ensure the conservation of migratory species; and

(ii) establish an Australian Whale Sanctuary to ensure the conservation of whales and other cetaceans; and

(iii) protect ecosystems by means that include the establishment and management of reserves, the recognition and protection of ecological communities and the promotion of off‑reserve conservation measures; and

(iv) identify processes that threaten all levels of biodiversity and implement plans to address these processes; and

(f) includes provisions to enhance the protection, conservation and presentation of world heritage properties and the conservation and wise use of Ramsar wetlands of international importance; and

(fa) includes provisions to identify places for inclusion in the National Heritage List and Commonwealth Heritage List and to enhance the protection, conservation and presentation of those places; and

(g) promotes a partnership approach to environmental protection and biodiversity conservation through:

(i) bilateral agreements with States and Territories; and

(ii) conservation agreements with land‑holders; and

(iii) recognising and promoting indigenous peoples’ role in, and knowledge of, the conservation and ecologically sustainable use of biodiversity; and

(iv) the involvement of the community in management planning.

(emphasis added)

49 Section 3A describes the principles of “ecologically sustainable development” as follows:

(a) decision‑making processes should effectively integrate both long‑term and short‑term economic, environmental, social and equitable considerations;

(b) if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation;

(c) the principle of inter‑generational equity—that the present generation should ensure that the health, diversity and productivity of the environment is maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations;

(d) the conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity should be a fundamental consideration in decision‑making;

(e) improved valuation, pricing and incentive mechanisms should be promoted.

50 Chapter 2 of the EPBC Act concerns “protecting the environment”. Section 11 contains a simplified outline of the chapter as follows:

This Chapter provides a basis for the Minister to decide whether an action that has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact on certain aspects of the environment should proceed.

It does so by prohibiting a person from taking an action without the Minister having given approval or decided that approval is not needed. (Part 9 deals with the giving of approval.)

Approval is not needed to take an action if any of the following declare that the action does not need approval:

(a) a bilateral agreement between the Commonwealth and the State or Territory in which the action is taken;

(b) a declaration by the Minister.

Also, an action does not need approval if it is taken in accordance with Regional Forest Agreements or it is for a purpose for which, under a zoning plan for a zone made under the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975, the zone may be used or entered without permission.

51 Part 3 within Ch 2 concerns “requirements for environmental approvals”. Division 1 of Pt 3 concerns “requirements relating to matters of national and environmental significance”. Subdivisions A to G set out ten categories of such matters: “World Heritage” (Subdiv A), “National Heritage” (Subdiv AA), “wetlands of international importance” (Subdiv B), relevantly here “listed threatened species and communities” (Subdiv C), “listed migratory species” (Subdiv D), “protection of the environment from nuclear actions (Subdiv E), “marine environment” (Subdiv F), “Great Barrier Reef Marine Park” (Subdiv FA), relevantly here “protection of water resources from coal seam gas development and large coal mining development” (Subdiv FB), and “additional matters of national environmental significance” (Subdiv G).

52 The phrases “coal seam gas development” and “large coal mining development” are defined in s 528 as follows:

coal seam gas development means any activity involving coal seam gas extraction that has, or is likely to have, a significant impact on water resources (including any impacts of associated salt production and/or salinity):

(a) in its own right; or

(b) when considered with other developments, whether past, present or reasonably foreseeable developments.

…

large coal mining development means any coal mining activity that has, or is likely to have, a significant impact on water resources (including any impacts of associated salt production and/or salinity):

(a) in its own right; or

(b) when considered with other developments, whether past, present or reasonably foreseeable developments.

53 Sections 18 and 18A (in Subdiv C) and 24D and 24E (in Subdiv FB) were relevant to the delegate’s decision under s 75. Their structure mirrors the pattern of other sections in Pt 3: a prohibition on taking an action and an identification of the circumstances when that prohibition does not apply. Sections 18 and 18A set out the prohibitions and offences in relation to species and communities and are as follows:

18 Actions with significant impact on listed threatened species or endangered community prohibited without approval

Species that are extinct in the wild

(1) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the extinct in the wild category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the extinct in the wild category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Critically endangered species

(2) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Endangered species

(3) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the endangered category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the endangered category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Vulnerable species

(4) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Critically endangered communities

(5) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened ecological community included in the critically endangered category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened ecological community included in the critically endangered category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

Endangered communities

(6) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed threatened ecological community included in the endangered category; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed threatened ecological community included in the endangered category.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

18A Offences relating to threatened species etc.

(1) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person takes an action; and

(b) the action results or will result in a significant impact on:

(i) a species; or

(ii) an ecological community; and

(c) the species is a listed threatened species, or the community is a listed threatened ecological community.

Note: Chapter 2 of the Criminal Code sets out the general principles of criminal responsibility.

(1A) Strict liability applies to paragraph (1)(c).

Note: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

(2) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person takes an action; and

(b) the action is likely to have a significant impact on:

(i) a species; or

(ii) an ecological community; and

(c) the species is a listed threatened species, or the community is a listed threatened ecological community.

Note: Chapter 2 of the Criminal Code sets out the general principles of criminal responsibility.

(2A) Strict liability applies to paragraph (2)(c).

(3) An offence against subsection (1) or (2) is punishable on conviction by imprisonment for a term not more than 7 years, a fine not more than 420 penalty units, or both.

(4) Subsections (1) and (2) do not apply to an action if:

(a) the listed threatened species subject to the significant impact (or likely to be subject to the significant impact) is:

(i) a species included in the extinct category of the list under section 178; or

(ii) a conservation dependent species; or

(b) the listed threatened ecological community subject to the significant impact (or likely to be subject to the significant impact) is an ecological community included in the vulnerable category of the list under section 181.

…

54 Section 19 provides for certain actions not being prohibited. These include where an approval under Pt 9 for the taking of the action is in operation: subss 19(1) and (2), or for other reasons set out in subs 19(3) including if the Minister decides under Div 2 of Pt 7 that the provision is not a controlling provision: para 19(3)(b).

55 Sections 24D and 24E set out the prohibitions and offences in relation to water resources, and are as follows:

24D Requirement for approval of developments with a significant impact on water resources

(1) A constitutional corporation, the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency must not take an action if:

(a) the action involves:

(i) coal seam gas development; or

(ii) large coal mining development; and

(b) the action:

(i) has or will have a significant impact on a water resource; or

(ii) is likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(2) A person must not take an action if:

(a) the action involves:

(i) coal seam gas development; or

(ii) large coal mining development; and

(b) the action is taken for the purposes of trade or commerce:

(i) between Australia and another country; or

(ii) between 2 States; or

(iii) between a State and Territory; or

(iv) between 2 Territories; and

(c) the action:

(i) has or will have a significant impact on a water resource; or

(ii) is likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(3) A person must not take an action if:

(a) the action involves:

(i) coal seam gas development; or

(ii) large coal mining development; and

(b) the action is taken in:

(i) a Commonwealth area; or

(ii) a Territory; and

(c) the action:

(i) has or will have a significant impact on a water resource; or

(ii) is likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(4) Subsections (1) to (3) do not apply to an action if:

(a) an approval of the taking of the action by the constitutional corporation, Commonwealth, Commonwealth agency or person is in operation under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(b) Part 4 lets the constitutional corporation, Commonwealth, Commonwealth agency or person take the action without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(c) there is in force a decision of the Minister under Division 2 of Part 7 that this section is not a controlling provision for the action and, if the decision was made because the Minister believed the action would be taken in a manner specified in the notice of the decision under section 77, the action is taken in that manner; or

(d) the action is an action described in subsection 160(2) (which describes actions whose authorisation is subject to a special environmental assessment process).

(5) A person who wishes to rely on subsection (4) in proceedings for a contravention of a civil penalty provision bears an evidential burden in relation to the matters in that subsection.

24E Offences relating to water resources

(1) A constitutional corporation, or a Commonwealth agency that does not enjoy the immunities of the Commonwealth, commits an offence if:

(a) the corporation or agency takes an action involving:

(i) coal seam gas development; or

(ii) large coal mining development; and

(b) the action:

(i) results or will result in a significant impact on a water resource; or

(ii) is likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

Penalty: Imprisonment for 7 years or 420 penalty units, or both.

…

(2) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person takes an action involving:

(i) coal seam gas development; or

(ii) large coal mining development; and

(b) the action is taken for the purposes of trade or commerce:

(i) between Australia and another country; or

(ii) between 2 States; or

(iii) between a State and Territory; or

(iv) between 2 Territories; and

(c) the action:

(i) has or will have a significant impact on a water resource; or

(ii) is likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

Penalty: Imprisonment for 7 years or 420 penalty units, or both.

…

(3) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person takes an action involving:

(i) coal seam gas development; or

(ii) large coal mining development; and

(b) the action is taken in:

(i) a Commonwealth area; or

(ii) a Territory; and

(c) the action:

(i) has or will have a significant impact on a water resource; or

(ii) is likely to have a significant impact on a water resource.

Penalty: Imprisonment for 7 years or 420 penalty units, or both.

(4) Subsections (1) to (3) do not apply to an action if:

(a) an approval of the taking of the action by the constitutional corporation, Commonwealth agency or person is in operation under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(b) Part 4 lets the constitutional corporation, Commonwealth agency or person take the action without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(c) there is in force a decision of the Minister under Division 2 of Part 7 that this section is not a controlling provision for the action and, if the decision was made because the Minister believed the action would be taken in a manner specified in the notice of the decision under section 77, the action is taken in that manner; or

(d) the action is an action described in subsection 160(2) (which describes actions whose authorisation is subject to a special environmental assessment process).

56 The matters of national environmental significance in Div 1 of Pt 3 are varied, see Subdivs A-G of Div 1 of Pt 3 referred to at [51] above. Division 2 of Pt 3 is also relevant: The protection of the environment from proposals involving the Commonwealth, including: “protection of the environment from actions involving Commonwealth land” (Subdiv A); concerning Commonwealth Heritage places outside Australia (Subdiv AA); and “protection of the environment from Commonwealth actions” (Subdiv B). The matters relevant to this decision are in Subdivs C and FB of Div 1 of Pt 3 (see above). But an appreciation of the variety of the others is relevant to the question of the imposition of the duty in decision making under the ss 130 and 133 because it assists in comprehending the structure and purpose of the EPBC Act and the particular provisions in respect of which decisions of the Minister may be required and the responsibility of the Minister to Parliament in respect thereof.

57 A feature of some importance in the understanding of the nature of the duties, powers and functions of the Minister in connection with the various features of the requirements relating to matters of national environmental significance is the place of the “environment” as defined in such considerations. The definition of the word is set out at [46] above. The word appears as part of the expression of the matters of national environmental significance in some, but not all, of the matters to which the EPBC Act makes reference: in Div 1 of Pt 3: in Subdiv E: the protection of the environment from nuclear actions where the nuclear action has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment: (ss 21–22A); in Subdiv F: action which has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment being a Commonwealth marine area: (ss 23–24A); Subdiv FA: action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: (ss 24B and 24C); and in Div 2 of Pt 3: in Subdiv A: concerning protection from action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment on Commonwealth land (ss 26–27A); Subdiv AA: concerning protection from action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment in a Commonwealth Heritage Place outside Australia: (ss 27B and 27C); and Subdiv B: concerning protection of the environment from action by the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on the environment: (s 28).

58 The other provisions of Pt 3 are not directed to protection of the “environment” as that word is defined, but rather the more specific features within the concept of the environment set out that are “matters of national environmental significance”. In the decision before the Minister under consideration here, those matters are contained in ss 18, 18A, 24D and 24E of the EPBC Act.

59 Part 4 within Ch 2 concerns “cases in which environmental approval are not needed”. In s 34, the matters protected by Pt 3 are identified. Items 3 to 8A concern ss 18 and 18A and items 13H and 13J concern ss 24D and 24E.

60 Chapter 3 concerns bilateral agreements between Commonwealth and States and Territories.