FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Crowley v Worley Limited [2022] FCAFC 33

Crowley v Worley Limited [2020] FCA 1522 | |

File number(s): | NSD 1248 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | PERRAM, JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS – representative proceedings – whether primary judge erred in not finding that respondent engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct –whether primary judge erred in not finding that respondent contravened its continuous disclosure obligations – relevant representor was the corporation and not the board of the corporation – knowledge of the board not determinative – inferences from facts as found – failure to call officers and employees – attribution of knowledge to a corporation – officer – meaning of “aware” – meaning of “information” – opinions are information – opinions that ought reasonable to have been formed are information – appeal allowed – remittal required |

Legislation: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) ss 12BB, 12DA Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Sch 2, ss 4, 18 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 9, 674, 677, 1041H |

Cases cited: | Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2019] FCA 1039 Australian Prudential Regulation Authority v Kelaher [2019] FCA 1521; (2019) 138 ACSR 459 Blatch v Archer (1774) 98 ER 969 Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 City of Botany Bay Council v Jazabas Pty Limited [2001] NSWCA 94; (2001) ATPR 46-210 Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Kojic [2016] FCAFC 186; (2016) 341 ALR 572 Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Limited (In Liquidation) [2015] FCA 149; (2015) 322 ALR 723 Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Limited (In Liquidation) [2016] FCAFC 60; (2016) 330 ALR 642 James Hardie Industries NV v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 332; (2010) 274 ALR 85 Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298 Jubilee Mines NL v Riley [2009] WASCA 62; (2009) 40 WAR 299 Maloney v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) (1978) 18 ALR 147 Pancontinental Mining Limited v Posgold Investments Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 131; (1994) 121 ALR 405 Sykes v Reserve Bank of Australia [1998] FCA 1405; (1988) 88 FCR 511 The Bell Group Ltd (in liq) v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 9) [2008] WASC 239; (2008) 39 WAR 1 TPT Patrol Pty Ltd as trustee for Amies Superannuation Fund v Myer Holdings Limited [2019] FCA 1747; (2019) 140 ACSR 38 Warren v Coombs [1979] HCA 9; (1979) 142 CLR 531 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 186 |

Date of hearing: | 16-17 August 2021 |

Date of last submissions: | 22 October 2021 |

Counsel for the Appellant: | Mr J Sheahan QC with Mr D Sulan SC and Mr A Edwards |

Solicitor for the Appellant: | ACA Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Ms W Harris QC with Mr R G Craig QC and Ms J A Findlay |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Herbert Smith Freehills |

ORDERS

NSD 1248 of 2020 | ||

| ||

Appellant | ||

AND: | WORLEY LIMITED ACN 096 090 158 Respondent | |

perram, jagot and murphy JJ | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. Orders 2 and 3 made on 22 October 2020 be set aside.

3. The matter be remitted to a single judge for such further hearing as that judge decides and for determination.

4. The respondent pay the appellant’s costs of the appeal as agreed or taxed.

5. The costs of the hearing below be remitted to the single judge for such further hearing as that judge decides and for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1 I agree with the orders proposed by Jagot and Murphy JJ and with their Honours’ reasons for those orders. I would like however to say something about my own interpretation of ASX Listing Rule 19.12 (‘Listing Rule 19.12’) in Grant-Taylor v Babcock & Brown Limited (In Liquidation) [2015] FCA 149; 322 ALR 723 (‘Babcock & Brown’). Listing Rule 19.12 now defines the word ‘aware’ in these terms:

an entity becomes aware of information if, and as soon as, an officer of the entity (or, in the case of a trust, an officer of the responsible entity) has, or ought reasonably to have, come into possession of the information in the course of the performance of their duties as an officer of that entity.

2 The plaintiffs’ contention in Babcock & Brown was that the directors of Babcock & Brown Limited (‘BBL’) ought to have held the opinion, on 29 November 2008, that the company was insolvent. My primary conclusion was that the facts known to the board on 29 November 2008 did not provide any basis for thinking that BBL was insolvent on that day. Consequently, there was no reason to think that the board ought to have formed an opinion that BBL was insolvent and hence no reason to think that it was ‘aware’ that it was insolvent. However, in the course of coming to that conclusion, I offered some observations on the interaction between the definition of ‘aware’ in Listing Rule 19.12 and the situation where facts might reasonably indicate that an opinion ought to be reached on those facts but where no such opinion is formed. I said this at [156]-[158]:

156. The word ‘information’ appears in both Listing Rule 3.1 and also in the definition of ‘aware’ in Listing Rule 19.12. I should be surprised if ‘information’ in Listing Rule 3.1 did not include opinions. For example, if the directors did in fact form the opinion that the company was insolvent it is difficult to see that Listing Rule 3.1 could be ignored on the basis that it did not apply to opinions. It is more likely that Listing Rule 3.1 should be construed as requiring the disclosure, all other requirements being satisfied, of opinions actually held or possessed. And, if ‘information’ includes opinions in Listing Rule 3.1, it is difficult to see that it does not bear the same meaning in the definition of ‘aware’ in clause 19.12. If directors hold opinions about market sensitive matters which are not generally available then, subject to the other requirements and exceptions in the ASX Listing Rules, these are to be disclosed to the market. However that observation needs to be understood in the context of Jubilee. The opinion of a single director would rarely be the correct information to assess from a disclosure perspective. Ordinarily, the relevant views are those of a board majority. This case does not raise any issue about the position of minority opinions and it is not necessary to express any concluded view on that matter, however.

157. What then of opinions not actually held? The plaintiffs submitted that BBL should have become aware of the fact of its insolvency on 29 November 2008 for a number of reasons to which I shall return. However, leaving that to one side, I do not think that the plaintiffs’ argument can be reconciled with the actual language of the definition of ‘aware’. What is required is that the information – on the present hypothesis, an opinion – ought reasonably to have come into the directors’ possession in the course of their duties. These words are not apt to describe the formation of an opinion. One does not come into possession of an opinion when one forms one because the phrase ‘come into possession’ conveys the concept of receipt and the concept of ‘receipt’ suggests an antecedent act of possession by another. Where the constructive knowledge limb of the definition of ‘aware’ is applied to information which is an ‘opinion’ what enlivens it is an opinion – not of the directors but of some other person – which reasonable diligence on the directors’ part would have brought to their attention. What it does not require is for the directors to form an opinion.

158. To give an example, if an opinion of senior counsel that a company was insolvent were included in its board papers then the company would be aware of that opinion within the meaning of the definition. Reasonable diligence on the part of the directors – i.e. reading the board papers – would have brought it to their attention. Leaving aside issues such as privilege, confidentiality and the need for its full context to be considered (i.e. Jubilee) it would be subject to Listing Rule 3.1. On the other hand, Listing Rule 3.1 is not engaged where the directors of a company should have, but did not, realise the implications of information of which they were aware.

3 Having considered the matter further, it seems to me that this statement is not correct. One problem it has is internal inconsistency. For example, in the third sentence of [156], I accepted that an opinion which was actually held would be within the definition of ‘aware’ (in the context of discussing ASX Listing Rule 3.1). Yet, at [157], I concluded that the formation of an opinion could not be brought within the language of ‘come into possession of the information’ because it connoted an antecedent act of possession by another. But if that was true, it is just as true in the case of an opinion actually held. The logic of the statement leads to the conclusion that the formation of opinions is not caught by Listing Rule 19.12.

4 Since no-one thinks that is correct, it implies that my approach to the construction of Listing Rule 19.12 has gone awry in some way. I think the error is in reading too much into the words ‘come into possession’. Once one accepts that ‘information’ can include an opinion, it is appropriate to construe the expression so that the definition is capable of applying to opinions just like any other class of information. Consequently, the information in Listing Rule 19.12 should not be approached on the basis that it is to be treated like a chattel in the sense that possession of it can only ever be obtained from another. Rather, the possession into which the rule contemplates that a person might come, must be a possession whose nature is sufficiently broad to encompass the various ways an opinion might be acquired. Opinions can no doubt be acquired from others but can also be formed for oneself. The concept of possession in the rule must account for both.

5 I would therefore accept that an entity to whom Listing Rule 19.12 applies is ‘aware’ of an opinion which it ought reasonably to have formed on the facts known to it regardless of whether it did or did not in fact form that opinion. To the extent that [157] of Babcock & Brown suggests otherwise it should be regarded as an incorrect statement.

I certify that the preceding five (5) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Perram. |

Associate:

Dated: 9 March 2022

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JAGOT AND MURPHY JJ:

1 INTRODUCTION

6 This appeal is brought on multiple grounds alleging that the primary judge erred in dismissing the originating application and fourth further amended statement of claim (4FASOC) as a result of the primary judge rejecting the appellant’s claims that:

(1) the respondent, Worley Limited (WOR), engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by representing that it expected to achieve NPAT (net profit after tax) in excess of $322 million in the financial year ended 30 June 2014 (FY14) and that it had reasonable grounds to so expect (the FY14 guidance representation), in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Corporations Act), s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act) and/or s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) (the ACL); and

(2) WOR contravened its continuous disclosure obligations under s 674 of the Corporations Act and listing rule 3.1 of the (then) Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) Listing Rules by not notifying the ASX of the Material Information (that WOR did not have a reasonable basis for making the August 2013 earnings guidance statement) and/or the Earnings Expectation Material Information (that WOR’s FY14 earnings were likely to fall materially short of the consensus expectation of professional analysts covering the ASX and WOR securities that WOR would deliver between approximately $354 and $368 million in NPAT for FY14) on 14 August 2013, 21 September 2013, 9 October 2013 or 15 October 2013.

7 The primary judge’s reasons for rejecting the appellant’s claims are set out in Crowley v Worley Limited [2020] FCA 1522 (the judgment below or J).

8 For the reasons given below the appeal must be allowed and the matter must be remitted to a single judge for further hearing as that judge decides and determination. It is a matter for decision by that judge, but there is no apparent reason why it would be necessary for the further hearing to involve anything other than submissions as required, having regard to the reasons of the Full Court in this matter.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Defined terms

9 Terms defined in the judgment below have the same meaning in these reasons for judgment. In particular:

2.1.1 Budgets and budgeting terms

(3) the 27 May 2013 draft budget means the proposed budgets prepared by each of the locations in which WOR operated, which when compiled together disclosed an NPAT of $252 million for FY14 (which NPAT increased to $284 million by the time of adoption of the FY14 budget due to changes in foreign exchange (FX) rates: J [45], [47], [165];

(4) the FY14 budget means WOR’s budget for the financial year 2013/2014 approved by WOR’s board in August 2013 and which forecast NPAT of $352 million: J [8];

(5) HOH means “Half on half” and refers to the “phasing” or timing of financial results; in particular comparisons of results between the first half of a financial year, 1 July to 31 December (H1) and the second half, 1 January to 30 June (H2): J [172];

(6) P50 budget means a budget using the P50 parameter. P50 is a probabilistic Monte Carlo analysis of the statistical confidence level for an estimate. It means that 50% of estimates exceed the P50 estimate and, by definition, 50% of estimates are less than the P50 estimate. In other words, there is an equal chance of exceeding or going below the estimate: J [114];

(7) sandbagging means the suspected practice of executives in WOR’s locations attempting to lower the expectations of senior management by submitting a draft budget that they could then exceed quite readily: J [151];

2.1.2 WOR’s statements and alleged representations

(8) the August 2013 earnings guidance statement means the statement WOR published on 14 August 2013 saying (J [2]):

While recognizing the uncertainties in world markets, we expect our geographic and sector diversification to provide a solid foundation to deliver increased earnings in FY2014;

(9) the 9 October 2013 announcement means the statement WOR published on 9 October 2013 to the effect that its first-half result would be lower than in the prior year, but that it affirmed the August 2013 earnings guidance statement: J [3];

(10) the November 2013 revised earnings guidance means the statement WOR published on 20 November 2013 that (J [5]):

On current indications the company now expects to report underlying NPAT for FY2014 in the range of $260 million to $300 million with first half underlying NPAT in the range of $90 million to $100 million;

(11) the FY14 guidance representation means the representation alleged to have been conveyed by WOR publishing and maintaining its August 2013 earnings guidance statement that: (a) it expected to achieve NPAT in excess of $322 million in FY14, and (b) it had reasonable grounds to expect that it would achieve NPAT in excess of $322 million in FY14: J [23] and [624];

2.1.3 The allegedly non-disclosed material information

(12) Material Information means the claim that WOR did not have a reasonable basis for making the August 2013 earnings guidance statement: J [20];

(13) Earnings Expectation Material Information means the claim that WOR’s FY14 earnings were likely to fall materially short of the consensus expectation of professional analysts covering the ASX and WOR securities that WOR would deliver between approximately $354 and $368 million in NPAT for FY14: J [20];

2.1.4 WOR’s organisational structure

(14) region means one of the following eight regions around the world into which WOR’s business was organised, known as ANZ (Australia New Zealand), CAN (Canada), ASCH (Asia and China), USAC (USA and Caribbean), LAM (Latin America), MENAI (Middle East, North Africa, India), EUR (Europe), and SSA (Sub-Saharan Africa): J [91];

(15) location means the business locations into which each region was divided, of which there were 43 in total. For example, the ASCH region comprised eight locations, while MENAI comprised seven locations: J [92].

(16) CSGs means the three Customer Service Groups into which WOR allocated customers for FY14, being;

(a) Hydrocarbons: being customers involved in extracting and processing oil and gas;

(b) Minerals, Metals & Chemicals (MM&C): customers involved in extracting and processing mineral resources and manufacturing chemicals; and

(c) Infrastructure: a consolidation of two sectors Infrastructure & Environment (customers involved in projects relating to water, the environment, transport, ports and site remediation and decommissioning) and Power (customers involved in power generation, transmission and distribution).

There was a Managing Director for each CSG: J [93]-[94].

(17) ExCo means the Executive Committee, which reported directly to Andrew Wood, WOR’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), means the committee comprising Mr Wood and six Group Managing Directors (GMDs) who reported directly to Mr Wood, being Stuart Bradie (GMD Operations), Iain Ross (GMD Development), David Steele (GMD New Ventures), Randy Karren (GMD Improve), Barry Bloch (GMD People), and, from September 2013, Simon Holt, WOR’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO). The ExCo met at least monthly: J [97]-[100];

(18) CEOC means the CEO’s Committee, comprising the members of ExCo, the CFO in the period when he was not formally on ExCo, eight Regional Managing Directors (RMDs) who reported to Mr Bradie, and three Managing Directors of the Customer Service Groups (CSGs). The CEOC’s role was only to advise Mr Wood, and it did not make decisions: J [33], [91]-[93], [100];

(19) board means WOR’s board of directors. From 23 October 2012 and throughout the relevant period, Mr Wood was WOR’s only executive director.

(20) A&RC means the Audit and Risk Committee of the board, comprised of board members;

2.1.5 The different types of work for budgeting purposes

(21) secured work related to revenue from WOR’s portfolio of work in hand; where a signed contract for the work existed: J [112];

(22) unsecured work related to revenue from work described either as a “proposal”, “prospect” or “blue sky”; which had the following meanings:

(a) proposals related to work for which WOR had submitted a tender or had received a request for a tender, where there was usually a proposed start date for the project within the forthcoming year. An assessment of “Go” and “Get” likelihood was made for proposals in order to risk weight forecasted revenue and costs for work that may not materialise. “Go” was a percentage figure representing the likelihood that the project would be undertaken at all. “Get” was a percentage figure representing the likelihood that WOR would be engaged for the work in the event that the project went ahead: J [116];

(b) prospects related to tender processes for which WOR had not yet submitted a tender, or known projects where the tender process had not started. Budgeted revenue from “Prospects” was also discounted for “Go” and “Get” risks: J [117];

(c) blue sky means estimated revenue from expected projects not identified at the time of forecasting. Mr Wood described “blue sky” as estimated revenue from expected projects based on discussions with customers and projects that are likely to materialise based on history and past experience, such as under a framework agreement. Denis Lucey, RMD of the ASCH region from 2011 to 2014, described it as an estimate of the value of projects which WOR expected to be engaged to undertake during the course of the financial year (other than secured work, proposals and prospects), based on a subjective assessment of the particular location’s historical performance and current market conditions and also taking into account WOR’s strategy for the coming year. Robert Ashton, RMD of the MENAI region from March 2013 to November 2016, described it as projects that were not known but were anticipated based on a combination of the operational history of the location, information obtained from customers or industry analysts and or anticipated market conditions. Blue sky was estimated at a numerical value and accounted for that value in the budget without any discount: J [41], [118]-[119];

2.1.6 Other

(23) BEBIT means business earnings before interest and taxes.

(24) EBIT means earnings before interest and tax.

(25) the Holt memorandum means a memorandum from Mr Holt, CFO, to the A&RC dated 5 December 2013: J [74];

(26) Michael Daly was WOR’s Global Director – Operations and Communications Support. He reported directly to Mr Holt: J [101];

(27) John Allen was WOR’s Global Director – Corporate Finance. He reported directly to Mr Holt: J [101];

2.2 Key facts

10 Many of the key facts were not in dispute.

11 On 14 August 2013 WOR published to the ASX the August 2013 earnings guidance statement, as follows (J [2]):

While recognizing the uncertainties in world markets, we expect our geographic and sector diversification to provide a solid foundation to deliver increased earnings in FY2014.

WOR’s NPAT for FY13 was $322 million: J [1].

12 WOR’s earnings guidance was based upon its internal FY14 budget, which forecast FY14 NPAT of $352.1 million: J [8].

13 On 9 October 2013, WOR made the 9 October 2013 announcement, to the effect that its first-half result would be lower than in the prior year, but that it affirmed the August 2013 earnings guidance statement: J [3].

14 On 10 October 2013, Mr Wood gave a strategy presentation on behalf of WOR to members of the investment community. WOR lodged a slide pack of Mr Wood’s presentation with the ASX and thereby publicly released it. By that presentation WOR repeated the August 2013 earnings guidance statement: J [4] and [505].

15 On 15 October 2013, Mr Wood presented at the Macquarie WA Investor Forum. The slide pack for the forum ended with several bullet points including:

• We remain committed to our Vision 2017

…

• Expect improved earnings FY14 across all sectors

By that presentation WOR repeated the August 2013 earnings guidance statement: J [4] and [510].

16 On 20 November 2013 WOR published the November 2013 revised earnings guidance, in the following terms (J [5]):

On current indications the company now expects to report underlying NPAT for FY2014 in the range of $260 million to $300 million with first half underlying NPAT in the range of $90 million to $100 million.

17 On publication of the November 2013 revised earnings guidance, the price of ordinary shares in WOR fell approximately 26%: J [1].

18 The appellant purchased 423 WOR shares on 4 October 2013 for a total consideration (including brokerage) of $10,046.59. On 30 May 2015, the appellant sold all of his WOR shares for $2,755.70: J [16].

19 The November 2013 revised earnings guidance led to reflection among WOR senior management about what might have gone wrong in WOR’s budgeting process. Mr Wood requested that Mr Holt “download…the issues as people saw them” about WOR’s budget process: J [577]. Mr Holt interviewed WOR managers and others, made the Holt interview notes, and prepared a memorandum dated 5 December 2013 accompanied by his notes of the interviews, which is the Holt memorandum: J [74] and [577].

20 The subject of the Holt memorandum was “Financial forecasting process” and its stated purpose was (J [571] and [576]):

… to provide a review of the current process that WorleyParsons follows with respect to its budgeting and forecasting and to discuss certain changes to this process being actioned or considered by management.

21 The “Background” section of the Holt memorandum records:

In the past six years, WorleyParsons has underperformed its original budget by 10% or more five times.

Moreover, re-forecasts done during the year have also proved to be less reliable than we would have expected.

Given that WorleyParsons uses its budgets/forecasts to provide guidance to the market, we have been in a position where we have been required to make a number of formal and informal profit downgrades.

These downgrades, and in particular the most recent one, have had an adverse impact not only on the WorleyParsons share price but also on our credibility in the market.

A summary of our budgeting process is attached as Appendix One to this document. It is important to note that the stated intention of the budgeting process is that the budget should be a “P50” budget. That is, that there should be a 50% chance that the group, or any particular location within the group, will achieve its budget.

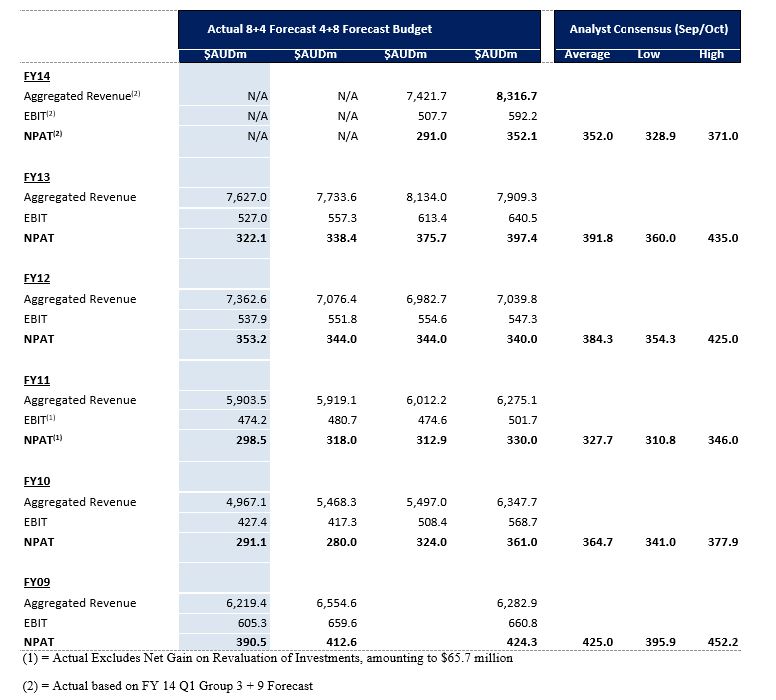

22 Section 3 of the Holt memorandum is headed “Recent results”. It includes a table, reproduced below, comparing WOR’s original budget, reforecast and final NPAT numbers over the past 5 years, including the analysts’ views of WOR for the period based on the analyst reports written following the release of WOR’s full year results:

23 The Holt memorandum says:

The table shows that, with the exception of FY12, WorleyParsons has underperformed on its original budget by at least 10% for every year back to FY09 (and will again for FY14). Further, the numbers suggest that our re-forecasts have probably not been much better than our budget from an accuracy perspective. However, the figures do indicate that we have done a good job at year end of guiding the analysts to a consensus that is approaching our budgeted figure.

24 In section 4, headed “Reasons for poor budgeting/forecasting performance”, the Holt memorandum records:

The CFO has undertaken a review to seek to understand why budgets and forecasts have consistently not been met over the last six years. This review has included discussions with EXCO, The Managing Directors of Operations and the Finance Leadership Team including the Finance Directors. The main conclusions are discussed below.

25 The key points about the budget are said to be that:

• There are some practical and cultural issues around the budgeting process including whether it is the right process for all locations.

• Expectations of growth at the senior management level have been too optimistic and have not matched what the locations are seeing on the ground.

• There is insufficient allowance made in the budget process for potential downsides.

• There is continued tension between locations and senior management as to whether locations are “stretching” themselves sufficiently in preparing their budgets.

26 The Holt memorandum continues:

The budget process

…there are still questions around whether the current process is appropriate for all locations and whether there is sufficient analysis being done of the reasonableness of the budget numbers at a group level. The budget process needs to be challenged/refined around the level of comfort placed in the go/get of prospects/proposals versus a scenario based methodology and the impacts of binary outcomes of the same prospects/proposals.

…

A consistent message is that there has been an expectation at group level that the company will grow, or grow at a certain rate versus previous years. This expectation seems to be driven both internally (“WorleyParsons has always grown at these type of rates”) and externally (“the market expects us to grow at x% so therefore that is what we need to do”). It does not necessarily seem to be driven by our own assessment of the markets in which we operate.

This expectation is then communicated back to the locations. The consequence of this is that, in many cases, the bottom up build that the locations submit does not match the expectations of growth from senior management. In order to meet these expectations, the most common response is for locations to simply include a greater level of “blue sky” revenue in the second half of their budget period. In essence, locations are ending up budgeting on the hope that work will materialise, rather than any real expectation that it will. Therefore, the probability that the budget will be met decreases. A conclusion from this is that our budgets have not genuinely been P50 budgets. This is supported by the fact that we have missed budget five out of the last six years.

Insufficient allowance for potential downsides

The review identified that our budget process does not make sufficient allowance for potential downsides – whether known or unknown. As the WorleyParsons business model has moved into larger and more complicated projects, the potential for material downside on one or more of these projects in a particular accounting period is high, but this potential downside is not built into the budgeting process. Put another way, our budget assumes that everything will go right in a world where we know things will go wrong.

The size of these issues can impact not only on the ability of a location to meet its budget, but on the group as a whole. In addition, the way in which the group budgets and operates means that it is unlikely that there will be unknown upside (i.e. work that is not already in secured, prospect or blue sky that is won and executed during the financial period) sufficient to offset the potential downsides.

In cases where potential problems have been identified on projects the feedback is that locations are actively discouraged from including potential downside in their budgets (at best, these are treated as a sensitivity at group level).

“Are we stretching?”

Another common message is that there is an assumption that locations are not “stretching” when they put in their initial budgets. The reasons for this appear to be both historical (based on the fact that for many years WorleyParsons consistently outperformed its budgets) and remuneration related (because location managers are rewarded based on their performance versus budget there is an assumption that they will always look to put in a low budget).

This perceived lack of trust in the initial location budget places pressure on the process, and leads to a considerable amount of back and forth between locations and management. It also obviously has the potential of penalising locations who make a genuine effort to get their forecasts correct, but who are still assumed to be “sandbagging”.

27 The Holt memorandum then turned to the issue of “Re-forecasts”. It says:

As noted above, the intention behind our re-forecast process is to give management an assessment, on a quarterly basis, as to how the group is tracking versus its original budget. This assessment is then used to determine whether WorleyParsons current market guidance is appropriate.

In practice, it appears that similar issues to those identified in the budget are cropping up in the re-forecast process. In particular, locations are under significant pressure to “hold the line” with respect to their original blue sky forecasts, even in situations where the local market conditions are such that it has become less likely that this work will materialise.

The reason given for this approach is to continue to put pressure on locations to perform. However, the risk is that our re-forecast is still about work we hope will come, rather than about work that we feel the market for our services will deliver.

28 In section 5, headed “Consequences”, the Holt memorandum says:

From an equity market perspective the consequences of our poor budgeting and forecasting have been pretty clear – a loss of confidence leading to a significant decline in our share price. In the longer term, if this lack of confidence continues, our ability to raise equity as required (e.g. for a material acquisitions) is also likely to be severely reduced.

A key point to note is that we have been good at guiding the market to our budgeted number; but that what the market did not necessarily realise is that this was a “P50” number (and, in reality, was probably lower than this). Consequently, the market is probably more surprised than it should be when we don’t reach this number.

From a staff perspective, the inaccurate budgeting has had a direct impact via our incentive schemes. The existence of the “gate opener” that was tied to performance versus budget has led to the very low payouts in recent years on our incentive schemes, with the resulting impact on engagement/retention etc.

In addition to the direct financial impact on staff, the setting of budgets that are considered unrealistic has, at least in some parts of the business, had a de-motivating effect. It is hard to engage staff when their views on budgets are not being taken into account and when they are being set targets they believe have a low probability of being met.

Another potentially less understood consequence has been that it has potentially allowed additional overhead to creep into the organisation. That is, we build an overhead structure for the revenue that we budget for, which includes blue sky. As blue sky revenue tends to be back ended, the overhead costs most likely get added earlier than when the blue sky revenue is earned. Consequently, if the revenue does not arise as forecast, it is not possible to remove the associated overhead in time to compensate.

29 The Holt memorandum concluded by noting that changes arising from a review process would be implemented in the FY15 budget process.

30 Appendix one to the Holt memorandum is headed “The current budget process”. It notes that the “current process is, at least in theory, a ‘bottom up’ process” explained as involving the following:

1. Most locations forecast their revenue and gross margin based on work that is “secured”, “prospects” or “blue sky”. Certain locations (usually the smaller ones and/or locations with high levels of consulting revenue) may budget more based on the current and forecast number of people.

2. This revenue and gross margin is split across the three CSGs and four service lines.

3 The location then determines what a reasonable level of overhead for the location is and derives the “location BEBIT” – which is essentially the EBIT of the location before global charges.

4. The location BEBIT number is subject to review by the Managing Director responsible for the location, and then by the Global Director of Operations, with any changes being put through the location pack.

5. Once all of the locations have determined their BEBIT, this result is consolidated at the group level to reach a group “Operational BEBIT” number.

6. The Global Services Group costs are then determined and subtracted from the Operational EBIT number to arrive at a Group EBITDA number.

7. Estimates are made of group interest, tax, depreciation, amortisation, minority interests etc. to arrive at a Group NPAT number.

8. The full result is then reviewed by the CEO and the CFO and changes may be made to either location or group numbers.

9. After all changes are made, the final pack is presented to the Board for its review and approval.

31 Appendix one to the Holt memorandum also records this:

Note that the stated intention of the budgeting process is that the budget should be a “P50” budget. That is, there should be a 50% chance that the group, or any particular location within the group, will achieve its budget.

32 As to re-forecasts, appendix one to the Holt memorandum says WOR does regular forecasts, previously 4+8 (that is, four months in for the next eight months) and 8+4 (that is, eight months in for the next four months).

33 WOR did not call Mr Holt, the author of the Holt memorandum, to give evidence. In addition, WOR also did not call Mr Bradie, Mr Allen or Mr Daly who were directly involved in the amendments to the 27 May 2013 draft budget, in which the 27 May 2013 draft budget with an NPAT of $252 million ($284 million with FX increases up to August 2013), was increased in the FY14 budget to an NPAT of $352.1 million. Her Honour described this process at J [47], as follows:

(1) the 27 May 2013 draft budget produced a forecast NPAT of $252 million;

(2) Messrs Bradie and Daly then added $34.9 million in operational EBIT and Mr Allen added $12 million for acquisition stretch with the result that the budgeted FY14 NPAT was $288.6 million;

(3) Messrs Bradie and Daly then added $20.7 million in operational EBIT with the result that budgeted FY14 NPAT increased to $295 million;

(4) CEOC then resolved to include an additional $43.8 million in overhead savings in the FY14 budget, of which $33 million would be recorded in operational EBIT; and

(5) $32 million was added to the budget NPAT figure using the current foreign exchange spot rate (Mr Crowley makes no complaint about this adjustment).

34 On 31 May 2013 Mr Daly noted in an email to Mr Holt and Mr Allen about the 27 May 2013 draft budget that “you see that the level of blue sky in ANZ (North and West) in particular is very high (ANZ South is high but is not such a worry given the nature of their business)”: J [198(2)].

35 On 11 June 2013, Mr Allen made the following comments to Ms Wallace (WOR’s Group Financial Controller), following a conversation with Mr Daly (J [224]):

Our guess is that Stu Stu [i.e. Mr Bradie] got a rocket from Andrew last week re the budget and has been told to change everything - making somewhat of a mockery of the process. If there was going to be a top down target why didn’t we start with that in the first place??

I am also concerned that we are putting the company’s reputation at risk. If we go out with another unrealistic budget, and need to do another profit downgrade next year, it is not going to look good at all in the market. Something to discuss with Simon.

36 On 3 August 2013 Mr Bradie emailed all RMDs about the draft budget, noting that the first and second half weighting of 43/57 was too second-half weighted and the RMDs needed to look across locations to see if more revenue could be moved into the first half: J [288].

37 On 7 August 2013 Mr Daly emailed Mr Holt saying (J [293]):

As an fyi only, there remains a strong sense within the business that the FY14 targets – both full year and H1 – are a stretch and I agree with that given current performance and the reliance on timely realisation of the cost saving targets. Something to bear in mind during your briefings over the coming weeks!

38 WOR released its final FY14 results on 27 August 2014. WOR reported statutory NPAT of $249 million, down 23% and underlying NPAT of $263 million, down 18%: J [611]. That is, having represented to the market that it expected to achieve NPAT in excess of $322 million in FY14 and that it had reasonable grounds to so expect, WOR in fact achieved NPAT of only $263 million.

3 PRIMARY JUDGE’S KEY FINDINGS

39 The primary judge made some key findings which are not the subject of challenge. These include that by publishing and maintaining the August 2013 earnings guidance statement WOR made the FY14 guidance representation on 14 August and thereafter, including on 9, 10 and 15 October 2013 that it expected to achieve NPAT in excess of $322 million in FY14, and it had reasonable grounds to so expect: J [29].

40 The August 2013 earnings guidance statement was based on its expected NPAT, calculated by reference to WOR’s FY14 budget: J [111].

41 WOR professed to adopt the P50 parameter to produce its budgets: J [114]. However, the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget: J [197].

42 As the FY14 budget setting process began, WOR’s major markets were “either not growing or were deteriorating”: J [418]. WOR admitted that there would be “continued uncertainty in the markets for its services in FY 14”: J [419]. The 27 May 2013 draft budget, compiled from the budgets provided by each of the locations, resulted in an NPAT of approximately $252 million: J [165]. On Mr Wood’s evidence, this draft budget generally reflected the locations’ efforts to identify “aggressive yet achievable budget targets”: J [196].

43 CEOC directed a reconsideration of the draft budget as a result of which, by late June 2013, the revised draft budget instead reflected an NPAT of $352.1 million: J [254]-[263]. As a result of this revision ExCo was concerned that “[e]veryone will be challenged to meet their budgets” and also that the split between the first and second halves of the year needed “more work … to reduce the weighting to the second half”: J [286]. The weighting to the second half of the year in fact increased as a result of further work: J [294]-[295].

44 On 13 August 2013 the board approved the FY14 budget with an NPAT of $352.1 million, a 9% increase on the FY 2013 result of NPAT of $322.1 million: J [309]. The August 2013 earnings guidance statement was developed in meetings of the A&RC on 12 and 13 August 2013: J [303]. The board approved the August 2013 earnings guidance statement to the market: J [298]-[303].

45 By its statements to the market, WOR aimed to get the analysts to align with WOR’s expectations and to encourage analysts to forecast WOR’s FY14 NPAT at around $352 million: J [307]-[308].

46 The primary judge also concluded that:

(1) the fact that, by the 23 February 2013 and 17 May 2013 ASX announcements, WOR had downgraded its earning guidance on two recent occasions before the FY14 budget was approved and stated that the downgrades were required because of WOR’s underperformance against its internal budget are additional matters that provided WOR’s officers with a basis for approaching the FY14 budget with caution: J [416] and [417];

(2) the fact that, as the FY14 budget setting process began, WOR’s major markets were “either not growing or were deteriorating” and that WOR was aware that in FY13 it had experienced challenging conditions in a number of its key markets and there would be continued uncertainty in the markets for its services in FY14, is a persuasive reason for approaching the FY14 budget with caution: J [418]-[421];

(3) there is evidence that aspects of the 27 May 2013 draft budget were optimistic and that, overall, the draft budget was “ambitious”: J [423];

(4) the Holt memorandum tends to support the appellant’s case that WOR’s historical performance against budget reflects defects in WOR’s budgeting process: J [600]; and

(5) the Holt memorandum demonstrates a significant record of underperformance by WOR against its internal budget every year since FY09, with the exception of FY12. It states that in five of the past six years WOR had underperformed its original budget by 10% or more: J [410]. The Holt memorandum interview notes provide “a basis for suspecting some locations may have submitted to pressure to accept adjustments to their respective budgets that they considered to be unrealistic, or may even have proposed budgets that they considered to be unrealistic”: J [329].

4 THE MISLEADING AND DECEPTIVE CONDUCT CASE

4.1 The appellant’s case

47 The appellant contends that the primary judge made all necessary findings to support the conclusion that WOR lacked reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement which conveyed the FY14 guidance representation other than the ultimate finding to that effect. According to the appellant, this failure results from four fundamental errors in the primary judge’s approach:

(1) first, a focus on justifying a decision of the board of WOR to approve the FY14 budget for 2014 and the August 2013 earnings guidance statement, rather than the required focus on the reasonableness or otherwise of WOR using the FY14 budget to justify the August 2013 earnings guidance statement;

(2) second, an unwarranted search for a level of detail in the evidence which would permit the primary judge to identify a calculation of NPAT for FY14 which would have been reasonably based;

(3) third, failing to appreciate the full significance of the evidence that was tendered and the findings made by considering the issues through too narrow a lens and failing to assess the evidence in the context of the other evidence; and

(4) fourth, failing to weigh the evidence and the proper inferences to be drawn consistently with the principles in Blatch v Archer (1774) 98 ER 969 and Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298.

48 The appellant submitted that these errors in approach are apparent in the primary judge’s apparent reluctance to draw the ultimate adverse inference against WOR, as disclosed in numerous paragraphs of her Honour’s reasons including as follows:

(1) as to WOR’s historical underperformance against budget resulting in previous earnings guidance downgrades, “more detailed analysis would be required to make a finding about the reason or reasons for WOR’s historical underperformance against EBIT and NPAT budgets. WOR’s performance against budget certainly raised an issue about systemic problems in accurately forecasting EBIT and NPAT, but it does not provide a basis for making a finding of systemic problems in accurately forecasting EBIT and NPAT without more”: J [414];

(2) as to these facts providing WOR’s officers with a basis for scepticism as to the grounds for the FY14 budget, “without knowing more about the reasons for WOR’s underperformance in any year, WOR’s track record does not itself provide a sound basis for a conclusion that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement”: J [415];

(3) as to WOR twice having to downgrade pervious earnings guidance in 2013, “[t]hese are additional matters that provided WOR’s officers with a basis for approaching the FY14 budget with caution but again, without knowing more about the reasons for WOR’s underperformance against its internal budget in FY13, they do not themselves provide a sound basis for concluding that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement”: J [417];

(4) as to the fact that WOR’s markets were not growing or deteriorating when the FY14 budget was set, while this was “a persuasive reason for approaching the FY14 budget with caution”, whether “it provided a basis for concluding that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement must depend upon the extent to which the budget reflected the perceived market conditions. That question was not analysed in sufficient detail to permit a conclusion that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement”: J [421];

(5) as to the fact that aspects of the 27 May 2013 draft budget were optimistic and that, overall, the draft budget was “ambitious”, the subsequent amendments increasing NPAT “does not prove that subsequent changes to the budget were unreasonable or inappropriate. By way of analogy, solicitors and junior counsel may conscientiously develop a set of arguments; those arguments may still be refined and improved by senior counsel”: J [229];

(6) as to the Holt memorandum, it does not “analyse how any particular defect affected any element of any budget. Nor does it attempt to quantify the impact of any defect in the budget process. For example, the memorandum does not analyse how any of its ‘key points’ affected the budget EBIT or NPAT figures in any year or years. Nor does the memorandum seek to test whether there might be any other explanation for the identified discrepancies between budget and actual performance apart from defects in the budgeting process. Nor, perhaps unsurprisingly, does the memorandum contain a broad conclusion that WOR’s budget process was ‘not reliable’, as Mr Crowley contended that the Court should find”: J [600]; and

(7) as to the Holt interview notes, which record WOR senior management’s “strong criticism of aspects of WOR’s budgeting and reforecasting processes”, “the notes do not provide significant weight in support of a conclusion that the FY14 budget lacked a reasonable basis to any particular extent, or that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement”: J [602]-[603].

49 The appellant also noted that, on the evidence and the primary judge’s findings:

(1) despite Mr Wood’s evidence that blue sky revenue was a function of market buoyancy, blue sky revenue was included in the FY14 budget when markets were flat or deteriorating as 19% of the gross margin, the same percentage of the total as in 2013, when markets were buoyant;

(2) the proportion of blue sky revenue was maintained at all times despite overheads being reduced so that blue sky, with its inherent risk, became a greater proportion of the EBIT; and

(3) the November 2013 revised earnings guidance was largely a result of a reduction in blue sky revenue of $110 million.

50 The appellant submitted that there was more than sufficient evidence, identified and accepted by the primary judge, which established that WOR lacked reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement but because of her errors in approach the primary judge refused to make that finding. In particular, the primary judge should have approached the issues recognising that:

(1) there is no principle which required a level of detail in the evidence sufficient to enable the primary judge to calculate the FY14 guidance representation which would have been based on reasonable grounds, and her Honour’s search for that kind of detail was erroneous;

(2) in any event, there was only one party that could provide detail of that kind, being WOR. Yet WOR only called evidence from Mr Wood, Mr Lucey and Mr Ashton, the latter two being RMDs for regions whose earnings were relatively minor, and it did not call evidence from Mr Holt or those directly reporting to him, particularly Mr Bradie, Mr Allen and Mr Daly, thereby engaging the principles in Blatch v Archer and Jones v Dunkel;

(3) all of the known and identified risks in the budgeting process, confirmed by the Holt memorandum, in fact came to pass; and

(4) the Holt memorandum is a near contemporaneous analysis of what was wrong with WOR’s budgeting process, promoted by the problems caused by the FY14 budget and August 2013 earnings guidance statement. It was not a product of hindsight by a person either uninvolved in or trying to deflect blame for the events. It was by the CFO, Mr Holt. It exposed precisely why the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement. It bears no resemblance to the years after the event documents characterised as nothing more than hindsight in Australian Prudential Regulation Authority v Kelaher [2019] FCA 1521; (2019) 138 ACSR 459.

51 The appellant submitted that the primary judge also should have appreciated the significance of her finding at J [197] that the FY14 budget on which the August 2013 earnings guidance statement was founded was not a P50 budget. It is one thing to intend a budget for internal purposes to be a P50 budget. It is another to use a budget that is not a P50 budget for the purposes of providing external guidance about earnings to the market. Given that the FY14 earnings guidance, as given in the August 2013 earnings guidance statement and thereafter, involved a positive statement to the market about expected earnings, the basis for that statement must be at least a P50 financial forecast (one where the results are as equally probable as improbable). Anything less is inherently unsuitable for use as the basis for external earnings guidance because, by definition, the expectation is not as equally likely to be met as not met. WOR’s officers knew or ought to have known this at the time.

52 According to the appellant, given that the August 2013 earnings guidance statement was a representation as to a future matter, and the only evidence WOR adduced to the contrary was as to the FY14 budget and the asserted P50 budget process, the primary judge should have concluded in these circumstances that WOR did not have reasonable grounds for making the FY14 guidance representation.

4.2 Discussion

53 The appellant’s contentions that the primary judge’s process of reasoning miscarried should be accepted.

54 Contrary to the case put for WOR below and in the appeal, the relevant issue was not what was actually known by WOR’s board, what views the board held, or the reasonableness of the conduct of the board (although that was also put in issue by the appellant below). WOR made the FY14 guidance representation, which conveyed to the market that it expected to achieve NPAT in excess of $322 million in FY14 and that it had reasonable grounds to so expect. While the FY14 guidance representation was made as a result of a decision of the board to adopt the FY14 budget and give the August 2013 earnings guidance statement to the market, the representor was WOR, not the board of WOR. Accordingly, the issue is whether WOR had reasonable grounds for making the FY14 guidance representation. The issue is not whether the board acted reasonably or unreasonably given the information made available to it by WOR’s officers.

55 The appellant did not contend before the primary judge that the board made the FY14 guidance representation. In the 4FASOC the appellant pleaded at para 51 that WOR made the FY14 guidance representation. The submissions made by the appellant below, recorded at J [640]-[645], do not suggest to the contrary. Those submissions focus on a different issue, being the deeming provision in ss 4(1) and (2) of the ACL and s 12BB(2) of the ASIC Act. A representation as to a future matter is taken to be misleading if a person does not have reasonable grounds for making the representation. A person is also taken not to have reasonable grounds for making such a representation “unless evidence is adduced to the contrary”. In the context of evaluating whether WOR had adduced evidence to the contrary the appellant submitted to the primary judge that “it was necessary for WOR to identify the relevant decision makers who relied on the asserted evidence to the contrary; and to prove that the asserted evidence to the contrary was in fact relied on by those decision makers”. This does not mean that the appellant was submitting that WOR’s board made the FY14 guidance representation, with the consequence that the issue of reasonable grounds was to be answered by reference to the diligence or otherwise of WOR’s board.

56 The erroneous focus of the primary judge on the conduct and knowledge of the board, as opposed to the conduct and knowledge of WOR, is most evident in the way in which her Honour dealt with her finding that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget. At J [428] the primary judge said:

Considered together, there were reasons for WOR’s Board to approach the task of approving the FY14 budget with caution (although there is no evidence that the Board ought to have known that the budget was not a true P50 budget). However, the matters identified by Mr Crowley fall well short of proving on the balance of probabilities that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement.

57 The relevant issues were that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget and whether WOR knew that to be so or knew the facts from which it should be inferred to have known that was so. If WOR knew, or by its knowledge of underlying facts should be taken to have known, that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget then that would have been evidence supporting the inference that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement. And as explained below, the fact that Mr Holt, Mr Bradie, Mr Daly and Mr Allen were not called to give evidence was itself relevant to the question whether the inference should be drawn that relevant persons within WOR (whether officers of WOR or not) knew or should be taken to have known that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget.

58 Nor can it be accepted that the appellant did not put below that WOR’s FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the making of the FY14 guidance representation. The appellant pleaded in the 4FASOC that, by 14 August 2013:

(1) WOR’s officers with responsibility for overseeing the budget projections were aware, and it was a fact that, the FY14 budget would be challenging to achieve (para 22B) including because:

(a) the forecast NPAT was increased from $252 million in the 27 May 2013 draft budget, as provided by the locations, to $352.1 million (particular 10);

(b) the 27 May 2013 draft budget and the adjusted budget thereafter reflected unrealistic blue sky forecasts (particular 11); and

(c) WOR had underperformed on its NPAT budget by at least 10% in each financial year from FY09 other than FY12 (particular (c));

(2) WOR’s officers with responsibility for overseeing the budget projections were aware, and it was a fact that, the FY14 budget (para 22C):

(a) provided for 19% of WOR’s expected earnings to come from the realisation of blue sky revenue;

(b) provided for 16% of WOR’s expected earnings from the realisation of prospect revenue;

(c) projected 59% of EBIT would be accrued in the second half of 2014, significantly exceeding the 52% EBIT actually achieved in the second half of 2013; and

(d) projected a significantly greater proportion of EBIT from blue sky and prospect revenue against secured work in in the second half of 2014 as compared to the first half of 2014;

(3) WOR had downgraded its earnings guidance on two occasions in FY13 (involving a downgrade in earnings from an NPAT of $346 million in FY12 to an NPAT of $260 to 300 million for FY13): para 23;

(4) WOR was aware that in FY13 WOR had experienced challenging conditions in a number of its key markets and that there would be continued uncertainty in the markets for its services in FY14: para 24;

(5) WOR was “aware” within the meaning of ASX Listing Rule 19.12, and it was the fact that, it did not have a reasonable basis for making the August 2013 earnings guidance statement (para 46), because (amongst other things)

(a) the effect of the budget process within WOR required the locations to reflect WOR’s growth strategy without due regard to the market conditions, including through an additional EBIT of $88.6 million to the “bottom up” build from the location’s budgets and $12 million “acquisition stretch” to WOR’s EBIT figure without a proper basis, and by including no contingency against underperformance except that from movements in foreign exchange rates: particular (a);

(b) the budget process within WOR had not included any or any adequate critical review of the locations’ blue sky revenue forecasts to ensure the forecasts were not inflated: particular (b);

(c) WOR budgeted for an unreasonable amount of blue sky revenue in its ANZ region, and in the SWO location of its USAC region: particular (c);

(d) as a result, WOR did not have reasonable grounds for including in the FY14 budget an NPAT forecast materially higher than approximately $284 million and/or a profit guidance to the market of “growth” on its FY13 NPAT result of $322 million: particular (d);

(e) further as a result, WOR’s officers with responsibility for overseeing its budget and forecasting processes ought to have known that WOR did not have a reasonable basis to forecast increased earnings in FY2014: particular (e); and

(6) further or in the alternative to para 46, WOR was “aware” within the meaning of ASX Listing Rule 19.12, and it was the fact that, its FY14 earnings were likely to fall materially short of the FY14 WOR Earnings Expectation: para 47;

(7) by reason of these matters, by making and repeating the August 2013 earnings guidance statement on 14 August 2013, 9 October 2013, 10 October 2013 and 15 October 2013 WOR engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H(1) of the Corporations Act, s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act, and/or s 18 of the ACL: paras 51-55.

59 The respondents’ contention - that it was no part of the appellant’s case that there was no reasonable basis for the FY14 budget because it was not a P50 budget - does not withstand scrutiny. It is true, as WOR contended, that the appellant did not plead that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget. It is also true that the appellant submitted at one point below that the case was not a case about a generally defective budget process but concerned an “obvious and unreasonable upwards adjustment of projected earnings by WorleyParsons’ executives once its budget process had produced unsatisfactory numbers” in the sense of the projected NPAT being too low. In other words, the appellant accepted that the outcome produced by the 27 May 2013 draft budget was reasonable (that is, a forecast NPAT for FY14 of approximately $252 million).

60 However, as discussed, the 4FASOC did sufficiently plead the alleged deficiencies in the budgeting process which meant that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget. Further, in opening written submissions the appellant identified that while WOR claimed to have produced a P50 budget the evidence would show that “this is far from what occurred in FY14”. In oral opening submissions the appellant contended that the interview notes underlying the Holt memorandum said that there was a “[g]eneral recognition of P50 trending down to P25”, and therefore that WOR “have only a 25% chance of meeting their internal forecasts”. In closing written submissions the appellant submitted that the essential conclusions from Mr Holt’s review were or included that:

…insufficient allowance was being made in the budget for potential downsides. WorleyParsons’ budget process “assumes that everything will go right in a world where we know things will go wrong.” Locations reported being “actively discouraged” from budgeting for downside risks. A process that was supposed to produce a P50 budget - namely a target with a 50% probability of being achieved - instead became a P25 budget meaning, critically, that it was three times more likely to be missed than achieved.

The appellant also submitted that the FY14 budget was not a true P50 budget, and included no adequate allowance for the risks associated with continued slow markets and operational underperformance.

61 In closing submissions the appellant further submitted:

The effect of the stretch targets for gross margin in the 27 May 2013 budget, plus the management adjustments that followed during June 2013, was to strip any P50 character from the budget. If every element of a budget is optimistic, there is no “portfolio offset” where a miss on one item can be offset by gains on others - a miss anywhere has an immediate effect on achievement of the budget. The process of “management adjustments” during June 2013 demonstrates how that P50 ambition became something much closer to a P 25 reality - as the Holt interview notes observed.

62 The appellant argued that: (a) WOR’s abandonment of a “bottom-up” budget process led to senior management imposing an unrealistic amount of EBIT for FY14 on the draft 27 May 2013 budget outcomes (referred to as management adjustments), and (b) the impact of flawed processes and assumptions resulted in a substantial and material overstatement of WOR’s FY14 budget and its guidance to the market.

63 In opening written submissions below the appellant said that this would be established by: (a) WOR’s historical underperformance against its budgets (b) the unrealistic and unreasonable “top down” pressure placed on the business in order to fulfil market expectations of continued growth, and (c) the fact that in November 2013 WOR removed about $97 million blue sky forecast from its FY14 budget, generally equivalent to the additional EBIT added to the 27 May 2013 budget by the management adjustments.

64 WOR’s response was that the robustness of its budget process and the availability of budget contingencies answered the appellant’s claims. In its further amended defence WOR pleaded that it had systems in place for the preparation of a robust and detailed annual budget for FY14: for example, paras 25(b) and 54(a). In its written opening submissions WOR made the positive assertion that the “evidence will show that WorleyParsons adopted a P50 parameter to produce the [FY14 budget]” and that the appellant appeared to accept that “a P50 standard is, without question, an appropriate measure for budgetary purposes”, which is correct because “the very task of forecasting is complex and there is an appreciation that forecasting for a 12 month period will mean that there will likely be change to the individual line items within the forecast” and operating a business is about taking calculated risks.

65 In its written opening submissions WOR also submitted that there were reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement as it resulted from “a detailed, time consuming and thorough budget process”. WOR further submitted that the August 2013 earnings guidance statement was substantially more conservative than the forecast NPAT in its FY14 budget, noting that there was approximately $30 million in “headroom” between the FY14 budget of $352.1 million and the August 2013 earnings guidance statement which forecast growth from the FY13 NPAT of $322 million, and even more when the FX contingency is taken into account.

66 In its written opening submissions WOR submitted that the appellant’s case was “schizophrenic and irretrievably illogical in its foundation”. According to WOR the predicate for the management adjustments case was that the 27 May 2013 draft budget from the locations was reasonable but the “errors” in the FY14 budget relied upon by the appellant were embedded in that 27 May 2013 draft budget. This submission was overstated. The appellant accepted that the forecast NPAT in the 27 May 2013 draft budget ($252 million) was reasonable and contended that the FY14 budget forecast NPAT of $352.1 million was not. Moreover, in answer to WOR’s case, the appellant submitted that WOR’s reliance on the budget process was misplaced given WOR’s historical underperformance against budget, the content of the Holt memorandum about that process, and the steps involved in the management adjustments. In other words, the reasonableness of the budget process and FY14 budget NPAT forecast were in issue. The appellant also challenged WOR’s reliance on the contingency in the FY14 budget. The $16.1 million contingency in the FY14 budget arose from a favourable shift in FX rates. However, WOR described it as a general contingency and a contingency against FX movements. In our view it was never a general contingency given that it arose from a short-term movement in FX rates and was fully deployed for that reason early in the FY14.

67 Given the above, in particular the way WOR conducted its defence, WOR cannot now complain in the appeal that it was not part of the appellant’s case below that the FY14 budget was unreasonable and not fit for use to prepare the August 2013 earnings guidance statement because of: (a) WOR’s history of material budget underperformance, (b) WOR having to twice downgrade its earnings forecasts in 2013, (c) the fact that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget and should have been known by WOR (and, it must be inferred, was known by some WOR employees) not to be such when it was adopted, (d) the fact that the FY14 budget did not result from a risk-adjusted approach to forecasting, (e) the fact that WOR’s markets were not growing or were deteriorating when the FY14 budget was being prepared, and (f) the fact that WOR maintained the 19% blue sky revenue, the same as 2013 when markets were buoyant, given that blue sky performance was a function of market buoyancy.

68 It is not to the point that WOR repeatedly asserted that it held the appellant to his pleading. The appellant was entitled to respond to the positive case asserted by WOR that its FY14 budget was the result of a robust and reasonable (indeed, according to WOR, “best practice”) budgeting process, was in fact reasonable as a matter of substance, and was a P50 budget which, by definition, was suitable for budgetary purposes and, by implication from WOR’s case, the FY14 budget was suitable to found the making of the August 2013 earnings guidance statement.

69 The primary judge referred to the appellant’s contentions to these effects at J [52] as the core factual matters on which the appellant relied to establish that the FY14 budget did not provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement. Her Honour said:

The [applicant’s] eight core factual propositions are as follows:

(1) WOR had a consistent record of underperforming against its internal budget since FY09, with the sole exception of FY12, and had not materially changed its FY14 budget-setting process from previous years.

(2) WOR had been required to downgrade its earnings guidance on two occasions in FY13 because of underperformance against its internal budget.

(3) In early 2013, as the FY14 budget-setting process began, WOR’s major markets were either not growing, or were deteriorating, and the expectation was for continued uncertainty in its markets during FY14.

(4) Between March and May 2013 the locations, together with the regional managing directors (RMDs) and managing directors of the customer service groups (CSGs), engaged in a thorough bottom-up budget process, with conscientious regard to “growth” and overhead reduction directives issued by senior management. The result was that the “detailed budget” compiled in very late May 2013 already incorporated stretch targets in respect of both revenue, and costs savings. Those targets were already optimistic, given market conditions.

(5) In June and July 2013, when it became apparent that the actual bottom-up budget would not support WOR’s Vision 2017 objective of year-on-year growth in every year from FY13 to FY17 (set out in full at [121] below), senior management, by the so-called management adjustments, demanded a series of top-down adjustments that aimed to increase operational EBIT by $88.6 million. The locations duly stretched again to reflect the majority of those adjustments in their local budgets (however improbable they were and proved to be).

(6) The FY14 budget included the $12 million acquisition stretch addition to EBIT that lacked a proper basis.

(7) The FY14 budget was not a true P50 budget (explained at [114] below), but rather included no adequate allowance for the risks associated with continued slow markets and operational underperformance.

(8) WOR’s budget process lacked a risk-adjusted review of its internal budget, particularly in relation to unsecured work, for the purpose of ensuring that any consequential guidance to the market properly reflected the risk associated with its stretch budget targets.

WOR has not filed any notice of contention to the effect that the primary judge erred in identifying the appellant’s case in these terms.

70 Further, and in any event, as the appellant submitted, regard should be had to the (accurate) observation of Beaumont J in Pancontinental Mining Limited v Posgold Investments Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 131; (1994) 121 ALR 405 at 414 that:

…under the modern system of pleading, the question is not whether the facts pleaded are in themselves sufficient to give rise to a cause of action. Rather, the question is whether it would be open to the applicant upon the pleadings to prove facts at the trial which would constitute a cause of action (see Mutual Life and Citizens Assurance Company Limited v Evatt [[1968] HCA 74]; (1970) 122 CLR 628 at 631).

71 For these reasons many of WOR’s submissions in the appeal must be rejected. For example, for the reasons given it is not to the point that:

(1) the 4FASOC does not refer to the FY14 budget not being a P50 budget;

(2) the 4FASOC does not assert that the FY14 budget was unreasonable and not fit for use as the foundation for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement because the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget; and

(3) there was no evidence that the board itself knew that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget.

72 The 4FASOC pleaded the facts from which it was open to the appellant to prove that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget and that WOR (as opposed to WOR’s board) should be inferred or taken to have been aware of this before the FY14 budget was adopted. Further, as WOR positively asserted that the FY14 budget was a P50 budget and therefore was both reasonable and a reasonable foundation for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement. It was open to the appellant to rebut that assertion by seeking to prove that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget and that relevant persons within WOR knew this to be so before the August 2013 earnings guidance statement was made.

73 The primary judge also expressed concern that she could conclude that the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget but could not conclude that that was a result of the management adjustments and did not know how the P50 standard was applied by WOR in preparing the FY14 budget: J [197]. These observations may be correct but they did not change the fact that, amongst other things, the primary judge was satisfied that the budget was not a P50 budget. Having so concluded, the issue was whether WOR knew or ought to have known that before it adopted the FY14 budget and used it as the foundation for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement.

74 For the same reasons, and in particular given each of the circumstances described in [67] above, the appellant was entitled to seek to prove that WOR’s reliance on its asserted robust budget process did not establish the reasonableness of the FY14 budget or provide reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement.

75 In the context of the cases put by the parties below, the primary judge was required to decide whether the appellant had established the facts described in [67] above and whether, as a result, the appellant was correct that WOR’s defence, that the evidence established the reasonableness of the FY14 budget and that it provided reasonable grounds for the August 2013 earnings guidance statement, should be rejected. As the appellant submitted, the primary judge did find all of the underlying facts but failed to draw the relevant inferences from those facts because of her Honour’s: (a) focus on the conduct of the board (in accordance with WOR’s submissions) rather than of WOR as the appellant submitted was appropriate, (b) search for a level of detail in the evidence enabling her Honour to decide on what would have been a reasonable forecast of FY14 NPAT, which was misguided, (c) lack of focus on the overall effect of the evidence, including the Holt memorandum, and (d) not weighing the evidence consistently with the principles in Blatch v Archer and Jones v Dunkel.

76 In particular, the primary judge made the following findings (and WOR has not filed a notice of contention that her Honour erred in so doing):

(1) the FY14 budget was not a P50 budget: J [197], [426];

(2) WOR had historically materially underperformed against its budgets from FY09 to FY13 (except in FY12) and had to twice downgrade its earnings guidance in 2013, and these facts provided a basis for WOR’s officers to be sceptical about the FY14 budget, and raised an issue about systemic forecasting problems in WOR: J [410]-[415];

(3) the FY14 budget process was not materially different from the process that had been followed in the preceding years: J [411];

(4) WOR’s markets were not growing or were deteriorating when the FY14 budget was set which was a persuasive reason for approaching the FY14 budget with caution: J [421];

(5) aspects of the 27 May 2013 draft budget (forecasting an NPAT of $252 million) were optimistic and that draft budget, overall, was “ambitious”, but the FY14 budget forecast NPAT of $352.1 million: J [423];

(6) ExCo was concerned that the FY14 budget meant that “[e]veryone will be challenged to meet their budgets” and the split between the first and second halves of the year needed “more work … to reduce the weighting to the second half”: J [286]; and

(7) the Holt interview notes record strong criticism by senior management of aspects of WOR’s budgeting and reforecasting processes”: J [602]; and

(8) consistent with the Holt memorandum (J [601]):

(a) WOR’s budget-setting process was affected by a culture of optimism. The Holt memorandum and the related interview notes recorded a “consistent message” of expectations of growth from senior management. There were cases where locations inflated their projections of blue sky revenue in order to meet senior management expectations;

(b) insufficient allowance was made in the WOR budget setting process for potential downsides. There was feedback that locations had been actively discouraged from including potential downside in their budgets where potential problems had been identified on projects; and

(c) there was a belief held by some of WOR’s senior management that locations were not sufficiently stretching in their initial budgets which was not necessarily valid.

77 The primary judge’s reasons do not bring all of these facts together in assessing whether WOR’s defence, and the appellant’s rebuttal of that defence, should be accepted. Rather, the primary judge focused on each piece of evidence explaining why, in and of itself, that piece of evidence did not support the appellant’s rebuttal. Accordingly, and as noted, the primary judge repeatedly considered that to draw the required inferences, more evidence and analysis would be required: J [414], [415], [417], [421], [229], [600]-[603] (set out in [48] above).