Federal Court of Australia

Facebook Inc v Australian Information Commissioner [2022] FCAFC 9

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN INFORMATION COMMISSIONER First Respondent FACEBOOK IRELAND LIMITED Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant be granted leave to appeal on the terms of the draft notice of appeal.

2. The notice of appeal be filed within 7 days hereof.

3. The first respondent file her Notice of Contention within 7 days of the filing of the notice of appeal.

4. The appeal be dismissed.

5. The appellant pay the first respondent’s cost of the appeal (including the costs of the application for leave to appeal).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

1 Subject to the following, largely by way of elaboration, I agree with the reasons of Perram J and with the orders proposed by his Honour.

2 The nature of Facebook Inc’s business is fundamental to all enquiries that concern it, especially where it was being carried on. Legal (like other) reasoning can be assisted by metaphor. In particular there is assistance sometimes in the description or characterisation of circumstances or activity by reference to metaphor. But the metaphor may have its dangers. As the Full Court said in D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc [2014] FCAFC 115; 224 FCR 479 at [4] in the context of scientific analysis:

… Metaphor can assist thought, in particular, by the evocation of structure and form by imagination; but it can also blind the eye of the mind by oversimplification. It may risk blinding real illumination that is achieved through analysis of the facts, including the scientific principles involved, by the utilisation of a striking evocation of a simplified structure of analysis that is derived from the metaphor chosen, rather than from the facts as existing.

3 We are not dealing with scientific analysis here. But we are dealing with a business that is not manifested in physical or material matter or structures or goods, but as described by Perram J at [29]–[33] of his reasons, which can be described as the collection, storage, analysis, organisation, distribution, deployment and monetisation of information about people and their lives. How that monetisation takes place in relation to the activities carried on by Facebook Inc is neither clear nor the subject of this proceeding. One can be sure, however, that the acts done to collect, store, analyse, organise, distribute and deploy the information about people and their lives are integral to the methods of monetisation or extracting commercial value from the information. The business is not about the simple sale of goods whether tangible or intangible. It is about extracting value from information about people.

4 The above is crucial in addressing the argument of Facebook Inc that there is a clear distinction useful for analysis here between physical acts and their consequences or effects. Facebook Inc’s business is not the sending of letters or telegrams, or the receipt of communications in California of messages sent by acts of users in other countries. To conceptualise what is occurring in such broken or particularised parts, especially by reference to more easily visualised in the mind physical activity, is to mischaracterise by oversimplification through the application of a false taxonomy of activity.

5 This is particularly the case in relation to the placement of cookies on users’ devices in Australia. The act of a person need not be discrete and conceptually separated in reality from its consequences. An act may occur in more than one place, may be continuous, complex and multilateral, and not just physically instantaneous in one place. Micro-surgery is not undertaken by the physical, manual manipulation of a scalpel by the hand of a surgeon upon the body of a patient. The surgeon may be at an instrument, physically separated from the patient, controlling the minute device that effects the surgery. The act is taking place at both places: where the surgeon is and where the patient is. It can be characterised or conceived of as one act. There is no reason of logic or conceptual appreciation as to why the conclusion must be different depending upon the distance of separation between the two locations. The consideration of the matter and the proper characterisation of the act or activity is to be approached by reference to the nature of the business and the place of the act or activity within the business, and the context as to why the question is being asked, being here the operation of a statute concerned with the privacy of information concerning people.

6 The law is familiar in many contexts with the notion of a continuing act, where characterisation of act and consequence or act and effect may be available, but less appropriate for the context at hand: The Queen v Rogers (No 2) (1877) 3 QBD 28 at 34 (the sending of a letter being regarded as a continuous act and the offence being committed where the letter is read); Ward v The Queen [1980] HCA 11; 142 CLR 308 (the shooting in Victoria and the impact on the victim in New South Wales – the impact not being an effect of the act in Victoria; but rather the fatal act of shooting in New South Wales); R v Baxter [1972] 1 QB 1 (the complex and continuing actus rei of a criminal enterprise); Dow Jones v Gutnick [2002] HCA 56; 210 CLR 575 at 600 [26] (distinguishing between unilateral and bilateral acts); Distillers Co (Biochemicals) Ltd v Thompson [1971] AC 458 at 468–469 (the ascertainment of the place of the tort). There is no necessary distinction in law between an instantaneous act and an effect. Digital activity is not to be reduced to pressing a button, sending a signal, and recognising a discrete effect. This miscomprehends and mischaracterises, in the context of the business, what is going on. In the context of a digital business such as Facebook Inc’s described earlier, the relevant act done in Australia is the installation and operation of cookies on Australian users’ devices and the making of the Facebook login available to an Australian developer in Australia. This is so whether one abstracts or conceptualises these as bilateral or continuing acts or activities, or as acts or activities not attaining significance or not crystallising until installation and operation on the device or the making of the login available to the user. The installation and operation and the making of the login available are not effects or consequences, but essential elements of the acts or activities themselves.

7 The division for all purposes of instant act from consequence or effect suppresses both philosophical and practical enquiry. We are not concerned with the former; but we are the latter. In law, act and effect and indeed cause and consequence and like enquiries depend upon context. Their resolution is not dictated by systematic exposition of theory (which would be, as Pound said in relation to causation, “unscrewing the inscrutable”: Pound, NR “Causation” (1st Harry Schulman Lecture of Torts, Yale Law School (1957) 67 Yale Law Journal 1, 1); but by appreciating why one is asking the question and the nature of the problem and the context at hand.

8 The place of these activities and these acts that are carried on and done by Facebook Inc in Australia in the overall commercial enterprise of Facebook Inc need not be precisely identified at this stage. Nor need the commercial significance of these activities and acts be drawn out beyond a recognition that they are part of the data collection and processing of the business described earlier. They may lack an intrinsic commercial quality in themselves looked at in isolation, but they take their place as a material part of the working of the business, which is held out as providing to its users a single global network for the instantaneous transmission and exchange of information. Much of the activity carried on by Facebook Inc does not generate revenue directly. An understanding that the revenue of the business is derived from monetisation of information collected, stored and analysed over a data sharing platform gives a ready intuitive explanation of that lack of direct revenue generation from such individual acts or activities in the overall commercialisation of the information. That does not, however, lessen the importance to the business, and to its being carried on, of the acts or activities occurring, where they occur.

9 The acts occurring in Australia, on Australian users’ devices, being the installation and deployment of cookies to collect information and help deliver targeted advertising, and the management of the Graph API to facilitate the collection of even more data may lack an intrinsic commercial character in and of themselves, but they are integral to the commercial pursuits of Facebook Inc.

10 This makes it unnecessary, and perhaps, with respect, distracting, to elevate a hypothetical question built on another business (Luckins (Receiver and Manager of Australian Trailways Pty Ltd) v Highway Motel (Carnarvon) Pty Ltd [1975] HCA 50; 133 CLR 164) to a status revelatory of the correct answer to the question whether Facebook Inc is carrying on business in Australia. The question has in any event been answered: the acts or activity in Australia need not be intrinsically commercial in themselves if they involve acts within the territory that amount to, or are ancillary to, transactions that make up and support the business: Valve Corporation v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2017] FCAFC 224; 258 FCR 190 at 235 [149].

11 Finally, Facebook Inc submitted that upholding the primary judge’s decision would involve an unprecedented expansion of the concept of “carrying on business” such that it would result in the “world…carrying on business in the world”. With respect, one should be wary of exaggeration. This is so, for at least two reasons. First, plainly, these reasons and those of Perram J do not support such a conclusion. Secondly, the consequences for other online businesses in other areas of law which utilise the concept of “carrying on business” are far from clear and are certainly not a foregone conclusion to be described as Facebook Inc’s submissions did. Any impact will depend upon the statutory context of the phrase and of the nature of the business being conducted.

I certify that the preceding eleven (11) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop. |

Associate:

Dated: 7 February 2022

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

PERRAM J:

12 This application for leave to appeal arises out of the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal and a Facebook application known as This Is Your Digital Life. It involves the apparently short question of whether the Australian Information Commissioner should have leave to serve her proceedings on Facebook Inc. Facebook Inc is incorporated in Delaware and is based in California. It is therefore ‘a person in a foreign country’ such that, irrelevant exceptions aside, leave is necessary before it can be served overseas with an originating process: rr 10.42 and 10.43(1)(a) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). Generally, a grant of leave to serve out of the jurisdiction requires the demonstration of a prima facie entitlement to all or any of the relief claimed: r 10.43(4)(c). The Commissioner was successful in establishing a prima facie case on an application which, for obvious reasons, was argued in the absence of Facebook Inc. Leave to serve Facebook Inc out of the jurisdiction was granted. It then conditionally appeared, as it was entitled to do, to set aside service but that application was refused by the primary judge: Australian Information Commissioner v Facebook Inc (No 2) [2020] FCA 1307 (‘J’). That determination was interlocutory in nature and therefore is subject to appeal only if leave to appeal is first obtained. Facebook Inc has applied for that leave and it is that application which is presently before the Full Court. The matter was fully argued on the basis that if leave were granted nothing further would need to be submitted on the appeal.

13 At the heart of the issues which fall for decision is the fact that whilst the social network known as ‘Facebook’ appears to its users to be a single object unaffected by international borders, it is in fact principally provided by two different entities. One of these is Facebook Inc itself which provides the Facebook platform to users located in North America. The other is an Irish subsidiary of Facebook Inc, Facebook Ireland Limited (‘Facebook Ireland’), which provides the Facebook platform to users located anywhere in the rest of the world. The issues before the Court concern, to an extent, the relationship between these two entities. The Commissioner has sued both entities and leave was also obtained to serve Facebook Ireland out of the jurisdiction. Unlike its parent, however, Facebook Ireland does not seek to set aside the service upon it. It took no active role in the present application.

14 Before turning to the issues which arise it is convenient to describe the events which have given rise to the litigation and to do so without distinguishing between Facebook Inc and Facebook Ireland. I will use the expression ‘Facebook’ as a placeholder to indicate that either or both of them did the act or thing described.

15 The Commissioner’s suit concerns an application known as This Is Your Digital Life. The application was created by Dr Aleksandr Kogan, a researcher employed by, or affiliated with, Cambridge University and from May 2014 was operated by a company of which he was a shareholder and director, Global Science Research Ltd (‘GSR’). I will refer to Dr Kogan and GSR as ‘the Developers’.

16 Dr Kogan described This Is Your Digital Life in a document he provided to Facebook. In that document, he described This is Your Digital Life as:

a research app used by psychologists. The requested permissions provide the research team with a rich set of social behaviour that Users engage in. This app is used in studies where we link psychological traits and behaviour (typically measured using questionnaires) with digital behaviour data in the form of Facebook information. We aim to use this data to better understand how big data can be used to gain new insights into people’s well-being, personality traits, and other psychological constructs.

17 As is common with many applications, This Is Your Digital Life invited persons wishing to use it to log in using their Facebook account. Perhaps unlike many applications, however, it did not offer any alternate means of doing so (for example, by creating a username and password). Users who used their Facebook logins to access This Is Your Digital Life were asked for permission by the application to access the personal information held by Facebook about them and also for access to the personal information of their Facebook friends. These permissions were subject to each user’s own privacy settings.

18 Having obtained the user’s permission, the Developers then requested that Facebook provide them with access to that user’s personal information and that of the user’s friends. Facebook provided this information, however, under the terms which governed the Developers’ use of the Facebook login. Under these terms, the Developers were not permitted to use the information other than for the purposes of the application. The Developers breached this requirement by permitting the personal information to be used for the purpose of political campaigns.

19 In Australia, approximately 53 Facebook users installed This Is Your Digital Life but the Developers obtained not only their personal information but that of approximately 311,074 of their Facebook friends. The Commissioner’s suit alleges, in a nutshell, that these events involved Facebook in contraventions of the Privacy Act 1998 (Cth) (‘the Privacy Act’). Specifically, the Commissioner says that Facebook Ireland and Facebook Inc have each breached Australian Privacy Principles (‘APPs’) 6 and 11.1(b). What are these?

The Privacy Act and its operation to entities outside of Australia

20 APPs 6 and 11.1(b) are located in Sch 1 to the Privacy Act. By s 15 of that Act, an organisation (which by s 6C includes a body corporate) must not do any act, or engage in a practice that breaches an APP. APP 6 prevents an organisation which has collected information for a particular purpose to use it for another, except in limited circumstances. APP 11.1(b) requires an organisation which holds personal information to take reasonable steps to protect that information from unauthorised disclosure.

21 It is presumed that a Commonwealth statute does not apply to persons outside of Australia: Jumbunna Coal Mine NL v Victorian Coal Miners’ Association (1908) 6 CLR 309 at 363 per O’Connor J. That presumption will be displaced, however, where the statute exhibits an intention to displace it. The Privacy Act is explicit in applying to persons outside of Australia although only in some circumstances. So much flows from s 5B, which is entitled ‘Extra-territorial operation of Act’. Section 5B(1A) applies the Privacy Act to acts done or practices engaged in ‘outside Australia’ if they are done or engaged in by an organisation that ‘has an Australian link’.

22 Where a body corporate such as Facebook Inc or Facebook Ireland is concerned, an Australian link will be present if two requirements are satisfied: first, the body corporate must carry on business in Australia (s 5B(3)(b)); and secondly, it must have collected or held personal information in Australia (s 5B(3)(c)). Importantly, it follows from the text and structure of s 5B that the ‘personal information’ so collected or held must be the information which forms the subject matter of the acts or practices said to breach an APP (I explain why this is so in more detail below). In other words, an Australian link will only be present where an organisation has collected or held personal information in Australia and it is that information which is alleged to have been misused or mishandled in contravention of the Act. If, for example, Facebook Inc collected personal information from users in Australia and then separately collected and misused personal information from users in the United States, such conduct would be beyond the scope of the Privacy Act.

23 As a matter of drafting, this has been achieved in a way which is obscure. Section 5B(3) provides:

(3) An organisation or small business operator also has an Australian link if all of the following apply:

(a) the organisation or operator is not described in subsection (2);

(b) the organisation or operator carries on business in Australia or an external Territory;

(c) the personal information was collected or held by the organisation or operator in Australia or an external Territory, either before or at the time of the act or practice.

24 The reference to ‘the personal information’ in s 5B(3)(c) appears to make no sense since there is no other reference to personal information in s 5B. The only way to make sense of it is to connect ‘the personal information’ to the acts and practices referred to in s 5B(1A). Put another way, s 5B(1A) applies the APPs to conduct outside of Australia. Most of those principles are expressed to operate by reference to either the collection of information or its holding. What the reference to ‘the personal information’ in s 5B(3)(c) does is to require that the personal information regulated by the APPs is the same personal information which provides the Australian link.

25 The disposition of the present application therefore turns upon two questions: first, whether Facebook Inc prima facie ‘carries on business’ in Australia within the meaning of s 5B(3) of the Privacy Act; and secondly, whether Facebook Inc prima facie collected or held certain personal information (which must be the same as the information which is the subject of the Commissioner’s claim in respect of APPs 6 and 11) in Australia.

The structure of the case and the proposed appeal

26 The Commissioner’s case before the primary judge was pitched at two levels. First, she submitted that there was a prima facie case that Facebook Inc carried on business in Australia in its own right and collected or held the relevant personal information in Australia. This case the primary judge accepted. Facebook Inc says that the primary judge was wrong to draw either the conclusion that it was carrying on business in Australia or the conclusion that it had collected or held the personal information in Australia. These arguments form the basis of Facebook Inc’s proposed notice of appeal in the event that leave to appeal is granted.

27 Secondly, the Commissioner submitted that there was a prima facie case that everything done by Facebook Ireland was done on behalf of Facebook Inc. Facebook Inc’s own submission was that Facebook Ireland was conducting the Facebook business in Australia and collecting and holding the relevant personal information in respect of Australian users. If a prima facie case were found that Facebook Ireland had done these things on behalf of Facebook Inc it would readily follow that there existed a prima facie case against Facebook Inc. This case was, however, rejected by the primary judge who concluded that there was no such prima facie case. The Commissioner says that the primary judge was wrong to draw that conclusion and this argument forms the basis of ground 1 of the Commissioner’s proposed Notice of Contention in the event that Facebook Inc is granted leave to appeal.

Was Facebook Inc carrying on business in Australia?

28 It is convenient to deal first with the question of whether Facebook Inc was carrying on business in Australia. In doing so, it is useful to consider separately the business that Facebook Inc is alleged to be engaged in and then to ask whether that business was being conducted in Australia.

What activities was Facebook Inc carrying on?

29 In my opinion, the evidence certainly presents a prima facie case that Facebook Inc was engaged in the business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland. The evidence consists of an agreement between Facebook Ireland and Facebook Inc entitled ‘Data Transfer and Processing Agreement’ (‘the Data Processing Agreement’). The agreement did a number of things but for present purposes it contained two core sets of obligations. First, it identified the data which Facebook Ireland was to transfer to Facebook Inc for processing. Secondly, it identified the nature of the processing which Facebook Inc was to carry out on that data.

30 Pursuant to cl 5(a) of the agreement, Facebook Inc promised to process the ‘personal data’ provided to it by Facebook Ireland. Appendix 1 to the agreement makes clear that the personal data to be provided by Facebook Ireland to Facebook Inc for ‘processing’ was the personal data of ‘registered users of the Facebook platform’. The data which was to be provided was also set out. It was the personal data ‘generated, shared and uploaded by the registered users of the Facebook platform’. This sounds broad and the agreement confirmed its breadth. It was to include: photographs, videos, events attended or invited to, group memberships, friends, gender, date of birth, relationship status, email address, URL, hometown, family, political views, religious views, sexual life, biography, employment history, location, education, interests, entertainment preferences, material shared by the user (i.e. wall posts, messages, pokes), credit card information and actions taken on Facebook and other services. Further it included ‘special categories’ of data. These were: racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, health and sex life.

31 What was the purpose of the processing to which Facebook Inc was to subject this data? It was, inter alia, to ‘facilitate communications across the Facebook platform’. Pausing there, it is to be noted that the Facebook platform comprised all users of Facebook, not just those users to whom Facebook Ireland provided the service. The data was also to be processed for the purposes of ‘personalising content’, ‘targeting advertisements and to assess their effectiveness’ and ‘identifying connections between Facebook users’. Again, none of this was limited to the users of the service provided by Facebook Ireland.

32 The nature of the Facebook platform might suggest that it is impossible to disaggregate the Facebook business in North America from that in the rest of the world. For example, such a balkanisation is difficult to reconcile with the fact that a post by an Australian user may appear in the newsfeed of a user in New York. Such a train of thought might pursue the implications of the obligation Facebook Inc had to Facebook Ireland to ‘facilitate communications across the Facebook platform’ and inquire further into whether the network effects which make Facebook so successful can be put to one side when analysing the nature of its business structure.

33 It is not necessary to pursue those bread crumbs, however. On its face it would appear that Facebook Inc carries on the business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland under the Data Processing Agreement. Facebook Inc denied that this was so but I did not find its submission persuasive. Here the argument was that its actions under that agreement were those of Facebook Ireland. But where A does an act for B it has never been the law that just because A’s act has been done on behalf of B (or even in the performance of B’s business) that A has not done the act as well. For example, a person who engages in misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law cannot say in their defence that they did not engage in the conduct because they were doing it on behalf of someone else. Consequently, and contrary to Facebook Inc’s submission, there is no plausible reason why Facebook Inc cannot be seen as carrying on the business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland. The contracting out by one firm of part of its business operations to another firm is common. The proposition that the second firm in such a situation is not conducting its own business appears heterodox.

34 I therefore reject Facebook Inc’s liminal objection that the only business being conducted in relation to Australian users was business conducted by Facebook Ireland. At the prima facie level, the Data Processing Agreement provides abundant evidence to the contrary.

Was this business being carried on in Australia?

35 That leaves, of course, Facebook Inc’s submission that assuming it was conducting a business, it was not conducting one in Australia. The primary judge was disinclined to accept this because the business being conducted by Facebook Inc appears to have included as two of its elements the installation of cookies upon the devices of users and the provision to Australian application developers of an interface known as the Graph API which includes as part of its functionality a facility which allows third party applications to utilise the Facebook login. The primary judge thought that there was a prima facie case that both of these activities occurred in Australia.

Cookies

36 One of the obligations that Facebook Inc had under the Data Processing Agreement was the installation of cookies. This obligation was as follows:

Installing, operating and removing, as appropriate, cookies on terminal equipment for purposes including the provision [of] an information society service explicitly requested by Facebook users, security, facilitating user log in, enhancing the efficiency of Facebook services and localisation of content.

37 At the prima facie level I would think that the installation of cookies ‘on terminal equipment’ is sufficient to answer this question adversely to Facebook Inc. There is no debate that ‘terminal equipment’ is a reference to a user’s device. What Facebook Inc has agreed to do is to install cookies on the devices of users. It is more than open to infer that the Data Processing Agreement is a carefully drawn document drafted by persons who know precisely what is involved in the installation of a cookie. Facebook Inc’s own assent to the expression that the cookie is installed ‘on’ the terminal equipment is eloquent that this is likely to be the case. It is certainly enough to make good a prima facie case.

38 Facebook Inc submitted that this question could not be answered without expert evidence as to the nature of cookies. I do not accept this submission. This is an application to set aside orders granting service out of the jurisdiction. It is not a trial. The only question is whether enough evidence has been put before the Court to make it appropriate to require a respondent to answer the claims made in the originating application and statement of claim: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Prysmian Cavi E Sistemi Energia S.R.L (No 4) [2012] FCA 1323; 298 ALR 251 at [94] per Lander J. Because of that, it is not necessary to adduce the whole of the evidence that the applicant will present at trial. Here, the Commissioner has put documents before the Court in which Facebook Inc itself says that it installs cookies on terminal devices. To my mind, this evidence is a canonical example of precisely the kind of evidence with which applications of the present kind are concerned. If Facebook Inc ultimately wishes to submit that it did not mean what it said or perhaps, that it spoke in error, then that is a matter which can be taken up at trial. However, such contentions have no place in a debate as to whether service out of the jurisdiction should be permitted.

39 Facebook Inc then sought to draw an analogy with the making of information available for browsing on a website where there is some authority for the proposition that a web page is not located where the user who accesses the web page is located: Gebo Investments (Labuan) Ltd v Signatory Investments Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 544; 190 FLR 209 (‘Gebo’). Indeed, Facebook Inc was explicit in submitting the installation of a cookie involved purely an act of uploading of some data by it and its corresponding download by the user. I do not accept this submission either. In its 2013 Data Use Policy, Facebook Inc described cookies in the following terms:

V. Cookies, pixels and other similar technologies

Cookies are small pieces of data that are stored on your computer, mobile phone or other device. Pixels are small blocks of code on webpages that do things like allow another server to measure viewing of a webpage and often are used in connection with cookies. We use technologies like cookies, pixels, and local storage (like on your browser or device, which is similar to a cookie but holds more information) to provide and understand a range of products and services. Learn more at: https://www.facebook.com/help/cookies.

This is prima facie evidence that cookies are ‘small pieces of data that are stored on your computer’, that they permit Facebook Inc to ‘understand the use of our products and services’ and that they make ‘Facebook easier or faster to use’. I do not accept that this is analogous to users of the World Wide Web using their browsers to examine documents located on servers situated outside of Australia. Thus I do not accept that cases such as Gebo have any bearing on the significance of the location where cookie installation occurs. Gebo is entirely silent on that issue.

40 Further, it is apparent that cookies are central to the Facebook platform. For example, in the 2013 Data Use Policy they are mentioned frequently. Under the heading ‘Other information we receive about you’, the policy tells users that whenever they visit a game, an application, or a website that uses the Facebook platform or visit a website with a Facebook feature then Facebook will receive data about this. Further, this data will be collected ‘sometimes through cookies’. What will the cookies collect? The policy continues: ‘the date and time you visit the site; the web address, or URL, you’re on; technical information about the IP address, browser and the operating system you use; and, if you are logged in to Facebook, your User ID’.

41 Later, the data use policy expands upon the use to which, inter alia, cookies are put:

We use these technologies to do things like:

• make Facebook easier or faster to use;

• enable features and store information about you (including on your device or in your browser cache) and your use of Facebook;

• deliver, understand and improve advertising;

• monitor and understand the use of our products and services; and

• protect you, others and Facebook.

42 The policy continues on the same page, ‘Cookies and things like local storage help make Facebook work, like allowing pages to load faster because certain content is stored on your browser or helping us authenticate you to deliver personalized content’.

43 For that reason, there is a readily available inference that Facebook Inc installs cookies on devices in Australia on behalf of Facebook Ireland as part of its business of providing data processing services to it. Further, it is clear that Facebook Ireland’s use of cookies (installed and removed by Facebook Inc) forms an important part of the operation of the Facebook platform. It is not an outlier activity. It is one of the things ‘which makes Facebook work’.

44 Finally, Facebook Inc invoked the spectre of the floodgates. Mr Hutley submitted that they would surely be opened were the Court to conclude that the installation of a cookie occurs where the cookie was installed. A number of points may be made about this. First, this Court is not called to say anything on that topic. It is merely asked to determine whether there is a prima facie case that the installation of a cookie on a device in Australia takes place in Australia. It may be that at trial, Facebook Inc establishes that a cookie is not installed where it was installed but rather from where it was sent. The determination that there is a prima facie case that a cookie is installed at the place where it is installed is not a momentous determination.

45 Secondly, the invocation of the floodgates raises more questions than it answers. I return shortly to the question of whether Facebook Inc was carrying on business in Australia, but the question of whether an overseas entity that installs cookies on a device in Australia is thereby carrying on business in Australia is likely to turn on the nature of the business it carries on and the nature of the cookie. For example, a cookie which remembers a user’s login details so that they do not have to re-enter them each time a site is visited may stand in a somewhat different position to a cookie which tracks a user’s interest in chocolate biscuits so that the user’s newsfeed is peppered with advertisements for Tim Tams.

46 In any event, contrary to Facebook Inc’s submission, the question of whether the installation of a cookie in Australia can be seen as the carrying on of a business in Australia is unlikely to have a single answer.

47 I therefore accept that there is a prima facie case that in the conduct of its business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland, Facebook Inc installs cookies on devices in Australia and this is an activity which occurs in Australia.

The Graph API

48 The primary judge drew the inference that the Graph API was managed by Facebook Inc although he was prepared to accept that it did so on behalf of Facebook Ireland. He drew this inference because of an answer that Facebook Inc had given to a question asked by the Commissioner about the Graph API. This answer was:

… the process of allowing third party App developers to access the API was managed by Facebook Inc for all Apps on the Facebook platform, including on behalf of Facebook Ireland as the provider of the Facebook service to Australian users.

49 His Honour then reasoned this way at J[147]:

Accepting for the purpose of argument that Facebook Inc’s activities in managing the Graph API were performed as a service to Facebook Ireland and that app developers contracted with Facebook Ireland, that does not mean that Facebook Inc did not carry on business, as service provider to Facebook Ireland, in Australia. Whether or not the activity was performed by way of services provided to Facebook Ireland, the fact is that Facebook Inc managed the Graph API process as part of its business. If the inference is open that some of Facebook Inc’s activities in managing the Graph API process were carried out in Australia, it is reasonably arguable that Facebook Inc carried on business in Australia within the meaning of s 5B(3)(b). In my view, the inference is available that a part of Facebook Inc’s activities in making available the Graph API to Australian apps included activity in Australia. The Graph API allowed apps to create a link or interface between the Facebook website’s “social graph” and the app. It is arguable and the inference is open that this involved activity by Facebook Inc in Australia, albeit initiated, controlled or operated remotely, such as the installing and operation of data in various forms.

50 Facebook Inc made two broad submissions about this statement. First, it was said not to have been supported by the evidence. Secondly, even assuming that it was so supported, the activities described by the primary judge – the installation of data in devices and the performance of operations on that date – could not constitute carrying on business as that concept was understood in the authorities. It is convenient to deal with these points separately.

51 Turning to the first proposition, it was not in dispute that the contract which Australian developers entered into when seeking to utilise the Facebook platform was a contract between each developer and Facebook Ireland. Clause 19(1) of that agreement expressly provided that where a developer was outside North America it was an agreement with Facebook Ireland. The balance of the agreement has little relevance although the principal obligations imposed on a developer may be found in cl 9. Facebook Inc did not point to any particular obligation imposed by that provision which was said to aid its argument.

52 Next, Facebook Inc submitted that all of the activity involving the Graph API happened in the United States or Sweden. The point of this submission was to show that the finding by the primary judge that it was open to infer that the installation and operation of data occurred in Australia could not be correct. The evidence about this consisted of written answers given by Facebook Inc to the Commissioner. The Commissioner had asked Facebook Inc to identify the Facebook entities which processed the personal information of Australian users. It had responded that this happened under the exclusive control of Facebook Ireland and was done in data centres located in either the United States or Sweden. The Commissioner had then asked Facebook Inc to give a description of how that equipment handled the personal information. Facebook Inc had responded that the data centres in the United States and Sweden were used to ‘run software through which the information was processed’ and that this included software ‘to action requests made by Australian Users, including through the Graph API and other features of the Facebook service’ (emphasis added).

53 In Facebook Inc’s submission, there was therefore no evidence that Facebook Inc did anything in Australia even leaving aside the fact that its actions in Australia were being done on behalf of Facebook Ireland. Everything to do with the Graph API happened in Sweden or the United States and there was no evidence that in the conduct of the Graph API anything was installed or operated in Australia.

54 I do not accept this submission. The primary judge attributed to the Commissioner this summary of the Graph API:

(6) The Graph API and Facebook Login (Statement of Claim [25]-[38])

23. During the Relevant Period, apps could request personal information from Users’ Facebook Accounts using a tool called the Graph Application Programming Interface (Graph API). The Graph API allowed apps to create a link or interface between the Facebook Website’s “social graph” (being the network of connections through which Users communicated information on the Facebook Website) and the app. Version 1 of the Graph API was in place during the Relevant Period (Graph API V1).

24. The link or interface between the Facebook Website and the app was facilitated by a further tool known as “Facebook Login”. This allowed an installer of an app (Installer) to utilise their Facebook account credentials (username and password) to login to an app. Where an Installer did so, a screen or page would appear on the app requesting the Installer’s permission for the app to request, through the Graph API, certain categories of the User’s personal information as that User had provided to the Facebook Website (Permission Request).

25. Through the Graph API V1, an app could request a wide range of information about not only those Installers who had responded to Permission Requests, but also their Facebook friends who had not installed the app (Friends). This included requests for sensitive information. In response to a request from an app, the Respondents disclosed information about Installers and their Friends to the app, subject to the User’s privacy settings on the Facebook Website … However, a User’s “privacy settings” did not alone control how a User’s personal information was shared with apps, including apps installed by Users’ Friends. Unless a User modified their “app settings”, various categories of the User’s personal information, including sensitive information, would be disclosed to apps installed by their Friends by default …

26. Although the Respondents had in place terms and conditions about what kinds of information an app could request (see the Platform Policy, the relevant terms of which are pleaded at [35] of the Statement of Claim), the Respondents relied upon app developers’ self-assessment that an app complied with these rules. In particular, as is alleged at [36] of the Statement of Claim, the Respondents did not have in place any procedures to approve an app’s ability to make requests of the Graph API V1; nor did it review the privacy policies of the apps themselves.

27. On 30 April 2014, a new version of the Graph API (Graph API V2) was launched by the Respondents. Under Graph API V2, app developers wishing to request more than basic information from Friends and Installers had to undergo a manual app review process (App Review). Such requests would only be approved where, among other things, the additional information clearly improved the User’s experience of the app. However, Facebook allowed apps using Graph API V1 a 12-month ‘grace period’ (Grace Period) to migrate to Graph API V2.

55 Facebook Inc did not submit that this description of the Graph API was incorrect. It will be seen that the description is agnostic as to which Facebook entity was involved. The key points in the description are these:

(1) the creation of a link or interface between the application and the network of connections through which users communicated information on Facebook; and

(2) the Facebook login which when offered by an application (i.e. an Australian application) and when utilised by an Australian user would ask the user for permission for the application to request personal information through the Graph API. If that permission was obtained then the application could then request and receive personal information through the Graph API.

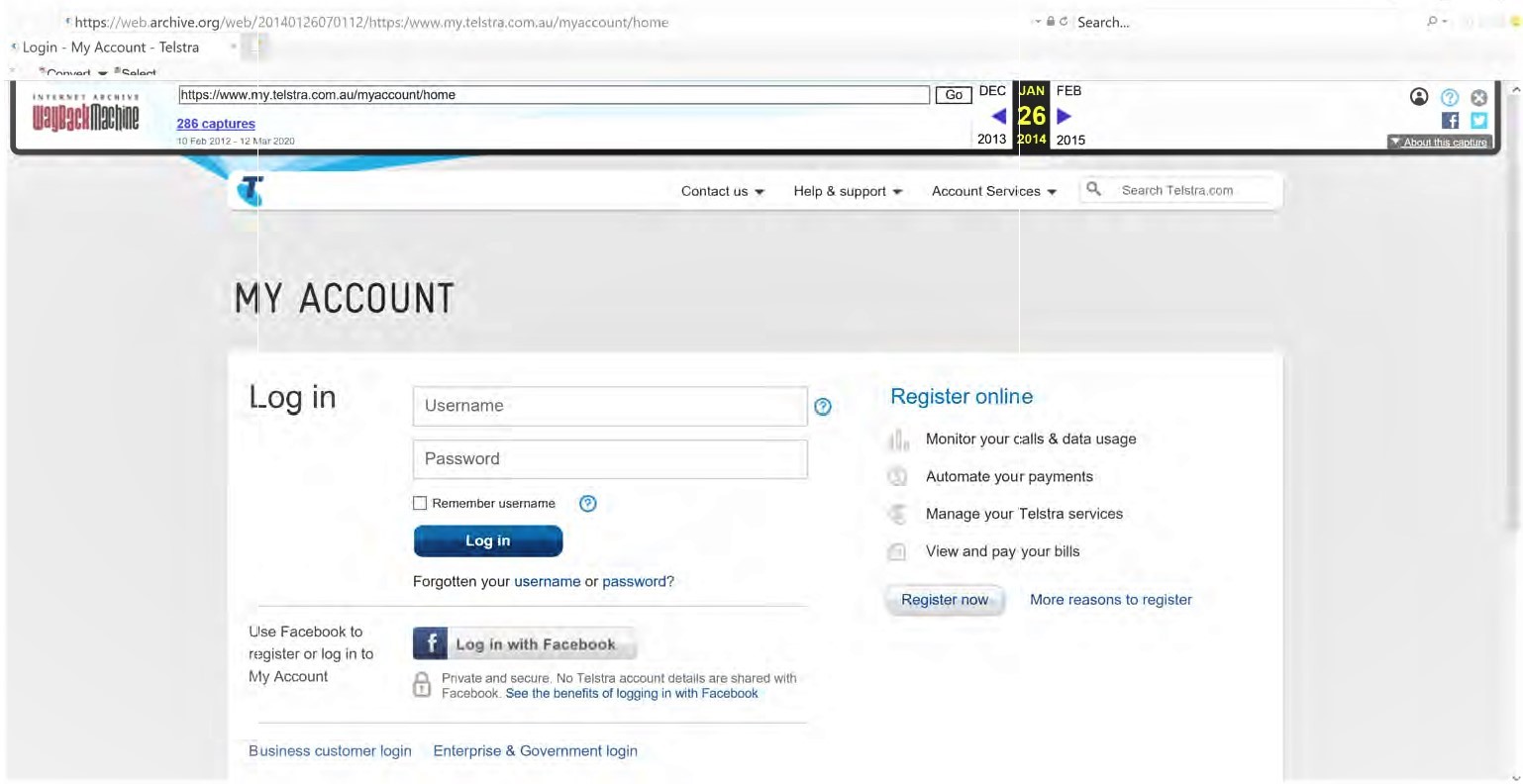

56 The Commissioner relied upon evidence about what the Facebook login looked like from the perspective of an Australian developer. Part of this evidence concerned Telstra’s portal for logging on to a user’s account with it. That page looked like this:

57 From this a number of inferences may be drawn. First, where a Telstra customer seeks to log in to the Telstra website using their Facebook credentials, the commencement of that logging in process occurs when the user presses the ‘Log in with Facebook’ button. The pressing of that button generally occurs in Australia (at least when the user is located in Australia). Secondly, the Australian user then provides their Facebook credentials. Thirdly, the provision of the credentials then permits the creation of a link or interface between Telstra and the network of connections through which users communicate information on Facebook. Fourthly, Facebook Inc then provides personal information to Telstra.

58 Returning to Facebook Inc’s answer that the software running in the data centres in the United States and Sweden included software ‘to action requests made by Australian users, including through the Graph API and other features of the Facebook service’, I would accept that this is likely to mean that the information which was provided to Telstra in this example is likely to have come from the data centres in the United States and Sweden. Further, I would accept the operation of the Facebook login is something which is done by Facebook Inc (on behalf of Facebook Ireland) from those data centres.

59 But I do not accept that this means that Facebook Inc did nothing in Australia. The correct focus is not on each individual log in by a Facebook user. Rather, it should be upon the business of providing the Facebook login functionality to Australian developers. The inference is open that this is an activity which occurs in Australia. Over-focus on the digital events which constitute that commercial activity with Australian developers is apt to distract attention upon the nature of the business activity.

60 Mr Hutley sought to distance Facebook Inc from that commercial activity in Australia. He pointed out that the answer that Facebook Inc had given about its management of the Graph API was not a statement that it managed the Graph API but rather a statement that it managed access to the Graph API. I accept that the literal answer given by Facebook Inc supports that contention. However, two obstacles lie in the path of accepting the submission. The first is that Facebook Ireland gave other answers which are inconsistent with any such peripheral role. The relevant questions and answers are Questions 26 and 30 which were posed by the Commissioner to Facebook Ireland in her s 44 notice. They were in these terms:

Question 26: For the period between 12 March 2014 and 17 December 2015, the number of Apps that Facebook Ireland deliberately prevented from accessing data through Graph API V1 due to the App’s misuse of data.

Answer: All review and assessment in relation to Graph API V1 and V2 was managed by Facebook Inc for all Apps on the Facebook Platform, including on behalf of Facebook Ireland as the provider of the Facebook service to Australian Users. Please see the response to Question 28 in the Facebook Inc Response for further detail.

Question 30: In relation to Graph API V1, particulars of:

a. the systems built by Facebook Platform Integrity (the Facebook team that builds systems and automation to detect and take enforcement actions against Apps violating the Platform Policy, as described in Facebook’s letters to the OAIC dated 6 July 2018 and 16 November 2018) to detect violations of the Facebook Platform Policy;

b. DevOps’ processes and policies for monitoring and enforcing compliance with the Platform Policy.

Answer: Relevant detection, monitoring and enforcement systems, processes and policies were managed by Facebook Inc for all Apps on the Facebook Platform, including on behalf of Facebook Ireland as the provider of the Facebook service to Australian Users. Please see the response to Question 32 in the Facebook Inc Response for further detail.

61 In addition, in response to a general question about its role in the data breach by Dr Kogan, Facebook Inc gave an answer which included this statement:

In addition, Facebook Inc was the entity most directly involved in the development and maintenance of the Facebook service, including the Graph API, for Users worldwide (although Facebook Ireland remained responsible for all processing of personal information of Australian Users, with Facebook Inc conducting data processing activities on behalf of Facebook Ireland in relation to the provision of the Facebook service to Australian Users).

(Emphasis added)

62 These answers are inconsistent with Facebook Inc merely managing access to the Graph API. I do not accept Mr Hutley’s submission that these documents have nothing to do with the issues in this case. They were raised by the Commissioner in response to the submission that Facebook Inc did not manage the Graph API but only managed access to it.

63 The second obstacle is that Facebook Inc conceded to the primary judge that it did manage the Graph API on behalf of Facebook Ireland. The concession was recorded at J[146(2)]. Dr Higgins relied upon this concession in her submissions and Facebook Inc did not contradict it. There is no reason, therefore, not to accept the concession recorded by the primary judge.

64 In that circumstance, I accept that an inference is open that: (a) Facebook Inc managed the Graph API on behalf of Facebook Ireland; and (b) this included providing the Facebook login to Australian developers for use in Australia as part of the business being conducted by Facebook Ireland. I also accept that the computers from which that business was being conducted in Australia were located in the United States and Sweden.

65 Before turning to the legal question of whether this activity constituted the carrying on of a business in Australia, a few points should be noted for completeness. Facebook Inc submitted that it was unclear what was involved in ‘managing’ the Graph API. The Commissioner submitted that this was Facebook Inc’s own word and it could hardly complain about what it meant when it came from its own answer. Facebook Inc responded to this by submitting that the burden lay on the Commissioner to prove the existence of a prima facie case. It was not clear what was involved in ‘managing’ the Graph API and the fact that it was its word did not mean that it was its problem. It is not necessary to resolve that debate. It is clear that Facebook Inc does acts in the United States and Sweden which result in the Facebook login being available for commercial use by developers in Australia. What the precise internal mechanics of this are do not matter. The real question is whether Facebook Inc on behalf of Facebook Ireland makes the Facebook login available to Australian developers in Australia. It is clear that an inference is open that it does.

Do these activities constitute the carrying on of business within the meaning of s 5B(3) of the Privacy Act?

66 Having accepted that it is open to infer that Facebook Inc installed and removed cookies on users’ devices in Australia and that it managed the Graph API here too, the question then arises whether it can be said that it was carrying on business in Australia by reason of that conduct. The primary judge accepted that Facebook Inc was engaged in this conduct as part of the services it delivered to Facebook Ireland under the Data Processing Agreement. Consequently, his Honour accepted that Facebook Inc had conducted part of that business in Australia.

67 On the application for leave to appeal, Facebook Inc took issue with this conclusion. There were, in essence, two contentions. First, it argued that Facebook Inc had no physical presence in Australia. It entered into no contracts, employed no personnel, had no customers and derived no revenues. There was, Facebook Inc submitted, no decided case in which a foreign entity had ever been held to be carrying on business in Australia where all of these indicia were absent. Even if the installation of cookies and the management of the Graph API were acts which took place in Australia, therefore, they lacked from the perspective of Facebook Inc the quality of being business activities.

68 Secondly, whilst there was a business being conducted in Australia, that business was that of Facebook Ireland. All that Facebook Inc did was provide services to Facebook Ireland in the conduct of that distinct business which, ex hypothesi, was not the business of Facebook Inc. Put another way, Facebook Inc undertook on its own account no trading or commercial activities in Australia. In that circumstance, even accepting for the sake of argument that the installation and removal of cookies together with the management of the Graph API might be activities occurring in Australia, they still could not be capable of sustaining a conclusion that Facebook Inc was itself carrying on business in Australia. It is useful to discuss these points in turn.

The absence of physical indicia in Australia

69 Facebook Inc submitted that it had no physical assets, customers or revenues in Australia. The data processing services were, on the evidence, provided from data centres which were located in the United States and Sweden. I take it to be implicit in that submission that the data centres consisted of physical premises containing servers and some employees. Facebook Inc submitted that before it could be held that a foreign corporation was carrying on business in Australia it had to be shown that at least some of the following were present: a fixed place of business, human instrumentalities (perhaps, humans), business assets, agents, contractual counter parties and customers. It submitted that there was not a single case which had held a foreign corporation to be carrying on business in a particular place where at least one of those elements was not present.

70 I do not accept this submission. Whilst it is common to speak of the general approach to the question of whether an entity is carrying on business in a jurisdiction, usually the question arises in a particular statutory context. In this case, the question is whether Facebook Inc ‘carries on business in Australia’ within the meaning of s 5B(3)(c) of the Privacy Act. The expression ‘carries on business in Australia’ is not a defined term in the Act. However, its meaning is informed by the statute in which it appears. Two matters are relevant. First, the objects of the Act include by s 2A(f) the facilitation of ‘the free flow of information across national borders while ensuring that the privacy of individuals is respected’. The statute therefore has in its contemplation the regulation of the flow of information insofar as it concerns privacy. Secondly, the terms of s 5B(3)(c) suggest that the focus of the Act is on the enforcement of the APPs in relation to the collection or holding of personal information. It is true that s 5B(3)(b) imposes the additional requirement that the organisation carry on business in Australia but that does not change the fact that this statute has as its focus a non-material concept: information.

71 I am unable in that circumstance to discern the presence of a negative implication in the Act which altogether denies the possibility that a business might be conducted in Australia without any of the indicia to which Facebook Inc points. The absence of such a negative implication is confirmed by the Explanatory Memorandum which accompanied the introduction of s 5B(3)(b):

Item 6 Subsection 5B(3)

Item 6 will amend subsection 5B(3) by rephrasing the opening of the subsection and inserting a reference to the new term ‘Australian link’. This will clarify that the subsection lists additional connections with Australia which would be a sufficient link for the Privacy Act to operate extra-territorially in relation to organisations and small business operators under subsection 5B(1A).

The collection of personal information ‘in Australia’ under paragraph 5B(3)(c) includes the collection of personal information from an individual who is physically within the borders of Australia or an external territory, by an overseas entity.

For example, a collection is taken to have occurred ‘in Australia’ where an individual is physically located in Australia or an external Territory, and information is collected from that individual via a website, and the website is hosted outside of Australia, and owned by a foreign company that is based outside of Australia and that is not incorporated in Australia. It is intended that, for the operation of paragraphs 5B(3)(b) and (c) of the Privacy Act, entities such as those described above who have an online presence (but no physical presence in Australia), and collect personal information from people who are physically in Australia, carry on a ‘business in Australia or an external Territory’.

(Emphasis added)

72 The emphasised part of the quote goes somewhat further than the language of s 5B(3)(b) probably permits. In particular, it appears to assume that the collection or holding of personal information under s 5B(3)(b) is sufficient to constitute the carrying on of a business under s 5B(3)(b). I do not think that the language of s 5B(3) can bear such an interpretation. As Facebook Inc correctly submitted, the requirements of ss 5B(3)(b) and (c) are cumulative. Read in the precise way that the Explanatory Memorandum suggests, s 5B(3)(b) appears to have no work to do which is not normally regarded as a likely interpretation: Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355 at [71] (per McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ). However, the statement is still useful because it is consistent with the conclusion which flows from the objects of the Act and the terms of s 5B(3) itself: that there can be no negative implication that an organisation cannot carry on business in Australia unless it has a physical presence of some kind in Australia.

73 Of course, to say that there is no such negative implication does not take the matter very far. In particular, it does not demonstrate that Facebook Inc is carrying on business in Australia merely because it does not have any of the suggested local attributes.

74 Is it possible to conduct business in Australia without having any physical presence within the jurisdiction? The primary judge concluded that ‘the means by which entities carry on business are constantly evolving’. He then observed that many of the cases in which the concept of carrying on business was discussed were ‘decided long before the technological advances which underpin many forms of commerce’. I agree with his Honour. The concept of carrying on business must, of necessity, take its shape from the business being conducted. Whilst the indicia to which Facebook Inc points no doubt have their place, I do think that some care has to be exercised about those statements to ensure that obvious propositions about the qualities of businesses at one time are not misapplied to radically different businesses at another. Facebook Inc submitted that the primary judge had, by making these observations, stated that the test needed to be changed. It is quite clear, with respect, that his Honour said no such thing.

75 Nor do I accept the submission that the primary judge’s approach would entail that any modern business conducted on the internet with a website accessible in Australia would be carrying on business in Australia. What this case decides is only that an inference may be drawn that a firm which installs and removes cookies in Australia (and which also manages for Australian developers a credential system which is widely used in Australia) is carrying on its worldwide business of data processing in this country. Whether a particular foreign-based business providing goods or services in this country carries on business here will depend on the nature of the business being conducted and the activity which takes place in this country. There is no one size fits all answer to this question. Correspondingly, the menace of opened floodgates from which Facebook Inc was commendably keen to protect the Australian legal system, is in my view very much overstated.

76 Nor do I accept the more radical form of this submission which Facebook Inc also pursued. It submitted that what had happened in this case was the transmission of digital signals from the data centres to user devices and that the transmission had brought about a change in the digital state of the devices. As such, all that happened was that action taken outside of the jurisdiction had resulted in an effect within the jurisdiction. Mr Hutley made the submission that once this was appreciated it could be seen that the current situation was no different to a person sending a letter from overseas to Australia, with the effect that upon its receipt, the reader did something which had an economic impact.

77 The problems with this submission are first that it proves far too much, and secondly that it is, with respect, divorced from reality. It proves too much because it has the consequence that no computer-based activity in one jurisdiction can ever amount to more than an effect in computers located in another. The submission has the result that no internet business based in one jurisdiction can ever carry on business in another. Any such business will, at best, be sending electronic signals to computers within Australia which will cause effects in those computers. But, according to the submission, mere effects cannot constitute the carrying on of a business. This extreme conclusion suggests the presence within the submission of error.

78 The error is the failure to account for the reality of what the signals and effects constitute. For example, there is an obvious distinction between an overseas website which provides data to an Australian computer when requested to do so, and an application that installs executable code on that computer and then causes it be executed. Facebook Inc’s submission lumps these two quite different situations together. Whilst Facebook Inc’s description of what is occurring is not wrong, it is pitched at such a high level of generality that it is, in my respectful opinion, useless as a tool of analysis. One might also say that Facebook Inc had done no more than turn on and off vast numbers of tiny switches – a true statement since all computers operate solely by switching on and off binary digits – but the statement, whilst true, is not helpful for grasping anything about the activities which Facebook Inc is actually engaged in. By parity of reasoning, one learns little about art history by observing that Rembrandt’s The Night Watch consists of some pigments on canvas in a wooden frame.

79 It is not necessary in that circumstance to assess Facebook Inc’s submission that mere effects within Australia cannot constitute carrying on a business. This is not a case of mere effects. For the same reason, the correctness of Mr Hutley’s analogy with the postal system does not fall for consideration.

80 Facebook Inc also placed particular reliance on Gebo and Valve Corporation v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2017] FCAFC 224; 258 FCR 190 (‘Valve’). In Gebo Barrett J said at [33]:

Advances in technology making it possible for material uploaded on to the internet in some place unknown to be accessed with ease by anyone in Australia with internet facilities who wishes (or chances) to access it cannot be seen as having carried with them any alteration of principles as to the place of carrying on business developed at times when such communication was unknown. It has never been suggested that someone who by, say, letters posted in another country and addressed to recipients in Australia, seeks to interest those persons in business transactions to be entered into in the other country and in fact succeeds in concluding such transactions with some of them thereby carries on business in Australia, even though, depending on precise circumstances, the solicitation may contravene some other Australian law. There is a need for some physical activity in Australia through human instrumentalities, being activity that itself forms part of the course of conducting business.

81 The Full Court in Valve was disinclined to accept the reference to human instrumentalities. As it said at [149]:

Although Gebo Investments concerned different statutory provisions, we consider the discussion of principles regarding carrying on business generally to be of assistance for present purposes. We do not, however, see the reference to “human instrumentalities” in the last sentence of [33] as laying down an inflexible rule or condition as to the circumstances in which an overseas company may be taken to be carrying on business in Australia. We would instead place emphasis on the statement at [31] of Gebo Investments that the case law makes clear that the territorial concept of carrying on business involves acts within the relevant territory that amount to, or are ancillary to, transactions that make up or support the business.

82 What Barrett J had said at [31] was this:

It is my opinion that the circumstances outlined are, of themselves, insufficient to constitute the carrying on of business in Australia. Case law makes it clear that the territorial concept of carrying on business involves acts within the relevant territory that amount to or are ancillary to transactions that make up or support the business. Many of the cases concern persons acting as agents within the jurisdiction of enterprise bases and operating outside the jurisdiction. One view has traditionally been taken where the agent within the jurisdiction has authority to bind the principal to dealings there; while another view has been taken of cases in which the agent is empowered to do no more than receive proposals or orders within the jurisdiction (often, no doubt, in response to solicitation there) and retransmit them to the principal. The distinction is discussed in several cases, including Okura & Co Ltd v Forsbacka Jernverks Aktiebolag [1914] 1 KB 715. Buckley LJ, speaking of a situation of the latter kind, there said (at p 721):

These being the facts, 101, Leadenhall Street is really only an address from which business is from time to time offered to the foreign corporation; the question whether any particular business shall or shall not be done is determined by the foreign corporation in Sweden and not by any one in London. In my opinion the defendants are not “here” by an alter ego who does business for them here, or who is competent to bind them in any way. They are not doing business here by a person but through a person. That person has to communicate with them, and the ultimate determination, resulting in a contract, is made not by the agents in London, but by the defendants in Sweden. It follows from this that one of the essential elements which must be present before a writ can be served in this country on the agent of a foreign corporation is lacking in this case. This appeal must, therefore, be dismissed.

83 The application of the test enunciated at [149] of Valve requires a focus on the transactions making up the business. As I explain in the next section, the transactions which make up Facebook Inc’s business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland include the installation and removal of cookies in Australia and the management for Australian developers of the Facebook login as part of the Graph API. I therefore do not accept that the discussion in Gebo, as qualified by what this Court said in Valve, assists Facebook Inc although I do accept that Valve requires one to identify with precision the nature of the transactions said to constitute the business.

84 Facebook Inc also submitted that the result in Valve could be distinguished from this case inter alia because there was no doubt in that case that physical assets (servers) were located in Australia. I accept this submission. The precise holding in Valve says nothing about this case. However, I do not think that this provides a good reason for not applying what was said at [149]. In terms of outcome, I do not think that Gebo throws much light on the current situation.

The Commercial Quality of Facebook Inc’s Activities

85 For the reasons I have already given, it is open to infer that Facebook Inc has two local attributes in Australia. It is installing and removing cookies on the devices of Facebook users and it is managing the Graph API; in particular, it is managing the provision by Australian developers to Australian users (and other users too) of the Facebook login. Facebook Inc’s submission that no case has held an entity to carry on business in a jurisdiction having none of the attributes to which it points may be correct. But it is not an overly useful observation in the present context because it does not engage with the consequences of the two attributes it does actually have in Australia.

86 Characteristically, Mr Hutley sought to meet this problem head on in his address. Accepting for the sake of argument that both the installation and removal of cookies on Australian devices by Facebook Inc and its management of the Facebook login (as part of the Graph API) were activities which took place in Australia, he pointed out that these were actions which were done on behalf of Facebook Ireland. It might well be that Facebook Ireland was carrying on business in Australia but it was that business which was being carried on and not the business of Facebook Inc. All it had done was to provide services to Facebook Ireland. The business transactions making up the relationship between Facebook Ireland and Facebook Inc did not occur in Australia.

87 This submission is, with respect, correct to emphasise the need to be precise in one’s identification of the business which is being carried on. In the present context it has been said more than once that the idea of a business denotes ‘activities undertaken as a commercial enterprise in the nature of a going concern, that is, activities engaged in for the purpose of profit on a continuous and repetitive basis’: Hope v Bathurst City Council (1980) 144 CLR 1 (‘Hope’) at 8-9 per Mason J (with whom Gibbs, Stephen and Aickin JJ agreed). Subsequent authority has held that the answer to this question involves: (a) identifying what the transactions that make up or support that business are; and (b) then asking whether those transactions or the transactions ancillary to them occur in Australia: Valve at [149] applying Gebo at [31].

88 It is necessary then to turn to the transactions which make up Facebook Inc’s business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland. Under the Data Processing Agreement what Facebook Ireland received from Facebook Inc was data processing services. The Data Processing Agreement is silent, however, on what it was that Facebook Inc was to receive from Facebook Ireland for providing those services. It may be assumed, I think, that it was obtaining some benefit but further than that it is not necessary to go. I did not understand Mr Hutley to deny that Facebook Inc was carrying on the business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland. His point was not that there was no such business but rather that it was a business which inhabited the data centres in the United States and Sweden. I take to be implicit in that position an acceptance that Facebook Inc was conducting a data processing business although how Facebook Inc pursued the making of profit from that business remains obscure.

89 The transactions making up this business would therefore appear to consist of the provision of the data processing services by Facebook Inc to Facebook Ireland in return for some kind of benefit whose nature is unclear but whose lack of clarity is not said by Facebook Inc to entail that no business was being conducted.

90 Where did these transactions take place? Facebook Inc did not submit that the nature of its data processing services was such that they were not situated anywhere. As I understood it, the contention was that the data processing services were located where the data centres which provided them were situated. This was in the United States and in Sweden. Consequently, Mr Hutley denied that these services took place in Australia. Indeed, Facebook Inc explicitly relied on the proposition that its business of providing the data processing services could not have been conducted in Australia precisely because it was being conducted in data centres overseas. I return to that proposition below.

91 At this point it is necessary to emphasise the distinction between, on the one hand, the location of activities constituting the installation and removal of the cookies on Australian devices and the management for Australian developers of the Facebook login (through the Graph API) and, on the other, the business of data processing of which those activities formed part. I have dealt with the first concept above and concluded that the primary judge was correct to conclude that an inference was available that those actions took place in Australia. The question now concerns the location of the second concept, that is to say, the location of the business of data processing.

92 Mr Hutley submitted that the fact that the installation of the cookies and the management of the Facebook login (through the Graph API) took place in Australia did not entail that the business which included them was located in Australia. Whilst it was true that these services were being provided by Facebook Inc to Facebook Ireland as part of its business of providing data processing services, this was not the business which was being conducted in Australia. The only business being conducted in Australia was that of Facebook Ireland. The users and developers in Australia had contractual relations with Facebook Ireland and the revenue which was derived from them was earned by Facebook Ireland. Facebook Inc’s role in this picture was merely to provide services to Facebook Ireland in the conduct of that quite different business.

93 The essence of this submission is that Facebook Inc’s activities in Australia themselves lack a commercial quality because Facebook Inc is not engaged in any commerce in Australia. Mr Hutley submitted that the facts of this case raised the interesting question which had been left unanswered by Gibbs J in Luckins (Receiver and manager of Australian Trailways Pty Ltd) v Highway Motel (Carnarvon) Pty Ltd (1975) 133 CLR 164 (‘Luckins’). I believe that Mr Hutley is correct and that the unanswered question in Luckins is now ripe for determination. To understand the unanswered question one needs to understand a little of the facts in Luckins. (The following summary is largely borrowed from the judgment of Barrett J in Gebo at [39]).

94 In Luckins, the relevant question was whether a company carried on business in Western Australia (the outcome of that question affected the validity of a charge over its property which was at issue in a dispute between creditors). The company operated overland tours in Western Australia in which passengers were transported by bus and provided with food and camping accommodation purchased by the company in the fulfilment of its contractual obligations to customers. The despatch of busloads of passengers through Western Australia and the undertaking of commercial transactions there in support of their transportation (the purchase of food, fuel and accommodation) entailed the carrying on of a business in Western Australia. And this was so even though none of the tours ever started or finished in Western Australia and even though it was rare for anyone to join a tour in Western Australia (and anyone who did so always left the tour outside Western Australia). So much was held by each of the judges including Gibbs J but with a dissent by Barwick CJ. However, at 178-179 Gibbs J left unresolved this conundrum:

It is unnecessary to consider whether the company would have carried on business within Western Australia if the only relevant fact had been that its tours had proceeded through the State without receiving or depositing passengers and if its employees or agents had no dealings with persons within the State. That, however, was not the case.

95 I accept Mr Hutley’s submission that this question is essentially the same as the question now posed for this Court. Facebook Inc’s business of providing data processing services to Facebook Ireland is conducted from its data centres which are not in Australia. But an aspect of that business – the installation and removal of cookies and the management of the Facebook login through the Graph API – are activities which do take place in Australia. As with the bus company in the unanswered question above, those activities do not themselves comprise the commercial dealings which are the business. If the answer to the question posed by Gibbs J in Luckins is that the company would have carried on business in Western Australia then this will entail that Facebook Inc does carry on business in Australia.

96 Luckins does not provide the answer to this question. In fact, the question posed by Gibbs J is a particular manifestation of a more general question. This question emerges from the description given by Mason J in Hope of the nature of the carrying on of a business as a collection of ‘activities undertaken as a commercial enterprise in the nature of a going concern, that is, activities engaged in for the purpose of profit on a continuous and repetitive basis’. The concept has therefore two elements: (a) activities undertaken as a commercial enterprise as a going concern with a view to a profit; and (b) carried on in a continuous and repetitive basis. Where a company undoubtedly conducts business in one place, this two limbed definition can give rise to two distinct problems when the company then does an act or acts in another place which, however, satisfy only one of the limbs in Hope. The two problems are these:

(1) the company engages in a single commercial transaction in a place where it otherwise does not conduct business. Does the company conduct business in this place? The single transaction means that the repetition requirement in Hope is not satisfied in that place but the commerciality limb is satisfied; and

(2) the company engages in repetitive acts in the performance of its business in a place where it otherwise does not conduct business but in doing so it engages in no commercial activity. Does the company conduct business in this place? The repetition requirement in Hope is satisfied but the commerciality limb is not.