Federal Court of Australia

Riseley v Suncorp Portfolio Services Ltd [2022] FCAFC 8

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed with costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Introduction

1 The appellants, John and Colleen Riseley, appeal from the judgment of a judge of this Court published as Riseley v Suncorp Portfolio Services Ltd [2021] FCA 472 (J).

2 The appellants brought two applications in the same proceeding which were heard and decided together by the primary judge. The one application was under s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) alleging jurisdictional error by the Superannuation Complaints Tribunal. The other was a review under s 5(1)(f) of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act) involving an error of law.

3 The applications related to complaints made by the appellants to the Tribunal against the first respondent, Suncorp Portfolio Serviced Ltd, which was the trustee of a superannuation fund of which the appellants were members. The complaints concerned the management of the appellants’ superannuation accounts between 2000 and around 2016, particularly the arrangements for insurance that were put in place as part of establishing the accounts, the payment of insurance premiums from the accounts, and the failure to provide total and permanent disability (TPD) insurance in circumstances where the appellants believed it should have been.

4 The Tribunal exercised its power under s 22(3)(b) of the Superannuation (Resolution of Complaints) Act 1993 (Cth) to treat each complaint as withdrawn on the basis that the Tribunal thought that the complaints were “lacking in substance”.

5 The primary judge found that no error had been demonstrated in the decisions of the Tribunal, namely with respect to each of Mr and Mrs Riseley. The applications were therefore dismissed with costs. The appeal to the Full Court turns on the proper construction of s 22(3)(b) and the proper exercise of the Tribunal’s power under that provision.

6 For the reasons below, the appeal should be dismissed with costs.

7 It is helpful to set out the legislative framework before identifying the relevant background facts and history of the complaint.

Legislative framework

8 The long title of the Complaints Act reveals that it is an Act “relating to the resolution of complaints about decisions and conduct of trustees of superannuation funds and approved deposit funds and of [retirement savings account] providers and insurers”. Part 2 of the Complaints Act establishes the Tribunal, and s 11 (in Pt 3) identifies the Tribunal objectives as follows:

11 Tribunal objectives

The Tribunal must, in carrying out its functions or exercising its powers under this Act, pursue the objectives of providing mechanisms for:

(a) the conciliation of complaints; and

(b) if a complaint cannot be resolved by conciliation—the review of the decision or conduct to which the complaint relates;

that are fair, economical, informal and quick.

9 The functions of the Tribunal are then set out in s 12:

12 Functions

(1) The functions of the Tribunal are:

(a) to inquire into a complaint and to try to resolve it by conciliation; and

(b) if the complaint cannot be resolved by conciliation—to review the decision or conduct to which the complaint relates;

(c) any functions conferred on the Tribunal by or under any other Act.

…

10 The nature of “complaints” that can be made to the Tribunal, which form the subject of its functions under s 12, are identified in Pt 4. There are a number of different categories of complaint that can be made against a trustee or an insurer, but in respect of each the ground of the complaint that can be made is that a decision or the conduct of the trustee or the insurer was “unfair or unreasonable”: ss 14(2), 14A(1), 15A(1), 15B(1), 15CA(1), 15E(1), 15F(1), 15H(1) and 15J(1).

11 It is common ground that the complaints in the present case are complaints made under s 14 which relevantly provides as follows:

14 Complaints about decisions of trustees other than decisions to admit persons to life policy funds

(1) This section applies if the trustee of a fund has made a decision (whether before or after the commencement of this Act) in relation to:

(a) a particular member or a particular former member of a regulated superannuation fund; or

(b) a particular beneficiary or a particular former beneficiary of an approved deposit fund.

…

(2) Subject to subsection (3) and section 15, a person may make a complaint (other than an excluded complaint) to the Tribunal, that the decision is or was unfair or unreasonable.

Note: Although a complaint is about the decision of a trustee, the Tribunal may join an insurer or other person as a party to the complaint (see subsection 18(1)). The Tribunal may then review any decision of a person joined as a party that may be relevant to the complaint.

…

12 In Wilkinson v Clerical Administrative and Related Employees Superannuation Pty Ltd [1998] FCA 51; 152 ALR 332 at 345 and 354, and in Breckler v Leshem [1998] FCA 57, it was held by Lockhart, Heerey and Sundberg JJ that the Tribunal’s review jurisdiction was confined to discretionary decisions. That was upheld in Attorney-General v Breckler [1999] HCA 28; 197 CLR 83 at [24] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ where it was said that the limitation of the grounds of complaint to one that the decision was unfair or unreasonable suggests that what is involved is a complaint as to the exercise by the trustee of a discretion rather than the discharge of duties, for example to distribute to those answering specified criteria (and see also [39]).

13 Following those decisions as to the limitation of the Tribunal’s review jurisdiction to discretionary decisions, the Complaints Act was amended (with effect from 11 December 1998 by item 8 of Sch 1 to the Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Resolution of Complaints) Act 1998 (Cth)) by the insertion of s 14AA (see Explanatory Memorandum, Superannuation Legislation Amendment (Resolution of Complaints) Bill 1998 at 9) to make it clear that non-discretionary decisions are also included within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction:

14AA Complaints may be made about discretionary or non‑discretionary decisions

(1) To avoid doubt, a complaint may be made under this Part about a decision whether or not the decision involved the exercise of a discretion.

(2) However, a decision that did not involve the exercise of a discretion is taken to have been unfair and unreasonable if the decision was contrary to law.

14 Section 15(1) identifies who may make a complaint under s 14. Relevantly, that includes a member or former member of the regulated superannuation fund or a beneficiary or former beneficiary of the approved deposit fund. There is no dispute that the appellants qualified to make their complaints.

15 Section 16 provides that the Tribunal must take reasonable steps to help the complainant if it thinks that a complainant wishes to make a complaint and they need help to make the complaint or to put it in writing. There is, however, no obligation on the Tribunal to assist a complainant to present their case to the Tribunal at the determination stage of the procedure to which we will come: Kristoffersen v Superannuation Complaints Tribunal [2014] FCAFC 63 at [66] per Dowsett, Collier and Rangiah JJ.

16 Under s 18(1), the parties to a complaint under s 14 are the complainant and the trustee, and if the subject matter of the complaint relates to a benefit under a contract of insurance between the trustee and an insurer and the Tribunal decides that the insurer should be a party to the complaint, then also the insurer. The joinder of the insurer is referred to in the note to s 14(2) quoted above (at [11]).

17 As this case concerns the (deemed) withdrawal of a complaint, it is helpful to set out the provisions dealing with that subject:

21 Withdrawal of complaint

A complainant may withdraw a complaint at any time.

22 Power to treat a complaint as having been withdrawn

(1) If:

(a) a complainant makes a complaint; and

(b) the Tribunal is satisfied, either after having communicated with the complainant, or having made reasonable attempts to contact the complainant and having failed to do so, that the complainant does not intend to proceed with the complaint;

the Tribunal must deal with the complaint as if it had been withdrawn by the complainant under section 21.

…

(3) The Tribunal may also decide to treat a complaint as if it had been withdrawn under section 21, in the following cases:

…

(b) if the complaint has been made to the Tribunal—the Tribunal thinks that the complaint is trivial, vexatious, misconceived or lacking in substance;

…

18 Part 5 of the Complaints Act deals with the conciliation of complaints. Under s 27, if a complaint has not been withdrawn and the Tribunal is satisfied that it can deal with the complaint under the Act, “the Tribunal must inquire into the complaint and try to settle it by conciliation.” There are then various provisions in support of the conciliation of complaints including as to the attendance at conciliation conferences (s 28), the conduct of such conferences remotely (s 29), privilege attaching to what is said at such conferences (s 30) and the implementation of settlements (s 31).

19 Part 6 of the Complaints Act deals with the review of decisions or conduct complained of.

20 Under s 32, if the Tribunal has tried to settle a complaint by conciliation but has been unsuccessful, the Tribunal must fix a date, time and place for a review meeting. A party to a review meeting may make written submissions to the Tribunal (s 33), the Tribunal may make an order allowing oral submissions to be made at the review meeting (s 34) and it may allow such oral submissions to be made remotely (s 35). Section 36 provides that in reviewing a decision or conduct, the Tribunal is not bound by technicalities, it is to act as speedily as proper consideration of the review allows and it may inform itself of any matter relevant to the review in any way it thinks appropriate.

21 Section 37 provides for the powers of the Tribunal in a review with respect to complaints under s 14:

37 Tribunal powers—complaints under section 14

…

(3) On reviewing the decision of a trustee, insurer or other decision-maker that is the subject of, or relevant to, a complaint under section 14, the Tribunal must make a determination in writing:

(a) affirming the decision; or

(b) remitting the matter to which the decision relates to the trustee, insurer or other decision-maker for reconsideration in accordance with the directions of the Tribunal; or

(c) varying the decision; or

(d) setting aside the decision and substituting a decision for the decision so set aside.

(4) The Tribunal may only exercise its determination-making power under subsection (3) for the purpose of placing the complainant as nearly as practicable in such a position that the unfairness, unreasonableness, or both, that the Tribunal has determined to exist in relation to the trustee’s decision that is the subject of the complaint no longer exists.

(5) The Tribunal must not do anything under subsection (3) that would be contrary to law, to the governing rules of the fund concerned and, if a contract of insurance between an insurer and trustee is involved, to the terms of the contract.

(6) The Tribunal must affirm a decision referred to under subsection (3) if it is satisfied that the decision, in its operation in relation to:

(a) the complainant; and

(b) so far as concerns a complaint regarding the payment of a death benefit—any person (other than the complainant, a trustee, insurer or decision‑maker) who:

(i) has become a party to the complaint; and

(ii) has an interest in the death benefit or claims to be, or to be entitled to benefits through, a person having an interest in the death benefit;

was fair and reasonable in the circumstances.

22 The powers of review of the Tribunal are much the same in respect of the various other categories of complaint: ss 37A – 37G.

23 In Board of Trustees of State Public Sector Superannuation Scheme v Edington [2011] FCAFC 8; 119 ALD 472 at [45]-[47], Kenny and Lander JJ (Logan J agreeing), with reference to pre-existing authority, identified key characteristics of the Tribunal’s review function:

(1) The function of the Tribunal is to conduct a form of administrative review of decisions made by trustees of regulated superannuation funds on the ground that the decision is unfair or unreasonable;

(2) A hearing before the Tribunal is a hearing de novo, following which the Tribunal makes findings of fact relevant to its deliberations;

(3) The Tribunal is not called upon to determine whether the trustee made the correct or preferable decision; rather, the tribunal stands in the shoes of the trustee and determines, based on all the information before it, whether or not a decision taken by the trustee was fair or reasonable in the circumstances;

(4) The words “the decision … was fair and reasonable” in s 37(6) were directed to whether the actual decision, rather than the process that led to it, was fair and reasonable;

(5) If the Tribunal is satisfied that the decision of the trustee was not fair and reasonable, the Tribunal makes a decision that is fair or reasonable in substitution for the decision of the trustee, always providing that the Tribunal cannot do anything contrary to law, the rules of the fund, or the terms of insurance.

24 It is to be observed that under s 37(5), the Tribunal is restricted to making a decision that is not contrary to law, the governing rules of the fund or the terms of a contract of insurance. That is to say, once having found that the decision under review was unfair or unreasonable, the Tribunal cannot substitute that decision with any decision that it considers fair and reasonable; it is limited to making a fair and reasonable decision within the confines of any governing rules or policy terms.

25 Under s 39, the Tribunal may refer a question of law to the Federal Court.

26 Finally, under Pt 7, a party to a complaint may appeal a determination of the Tribunal to the Federal Court on a question of law. No such appeal was brought in this case notwithstanding that the error that is complained of is an error of law. Although it does not matter, that may be because it was held in Burtaleea v AustralianSuper Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 521 at [41] and [57] per Buchanan J that a decision under s 22(3)(b) to treat a complaint as withdrawn is not a determination from which an appeal on a question of law lies under Pt 7; cf. Ludowyk v Superannuation Complaints Tribunal [2013] FCA 692 at [32] per Foster J. It may also be because of the 28 day limit on the commencement of an appeal from the day on which the determination is given to the person, noting that the proceeding below was brought nearly six months after the Tribunal’s decision.

27 The complaint process before the Tribunal can be analysed as comprising a number of phases as follows:

(1) Making the complaint, including the Tribunal assisting the complainant to do so (s 16), other parties joining or being joined (ss 17A and 24A), the provision of material to the Tribunal (s 24), and the Tribunal obtaining information and documents (s 25) (i.e., Pt 4);

(2) Conciliation of the complaint (Pt 5); and

(3) Review and determination by the Tribunal (Pt 6).

28 It is to be noted, however, that the withdrawal of a complaint by a complainant under s 21 may be made “at any time”. Also, given that there is no express temporal limitation on when the Tribunal may exercise the power under s 22 to treat a complaint as if it had been withdrawn, and that when it does so the complaint is to be treated as if it had been withdrawn under s 21 (which expressly has no temporal limitation), the power under s 22 can also be exercised at any time.

Background and history of complaint

29 The following events are drawn from the primary judgment where the background matters are set out in some detail: J[11]-[60]. The background matters up until the Tribunal’s notice of the withdrawal of the complaints are not in dispute.

30 In 2015, Mr and Mrs Riseley made complaints about their superannuation accounts to the then trustee. Broadly speaking, the complaints were founded on their claim that they had paid $10,000 as an upfront payment into superannuation and that they had done so on the basis that they had been told that the funds would be sufficient to provide life and TPD policies on an ongoing basis and that there would be a surplus that would be available for their retirement. They said that their accounts had not been operated in the manner indicated to them at the time the accounts were established: J[11].

31 The appellants were not provided with TPD cover and over a number of years the funds invested were used up paying for life insurance and other fees and charges: J[12].

32 The payment of the $10,000 occurred in January 2000 when Mr and Mrs Riseley applied to become members of the Connelly Temple Super Savings Plan. The arrangements were made by an advisor who was known to the appellants. He was not a representative of Connelly Temple. He was licenced to provide advice as a representative of another entity (MLC): J[13].

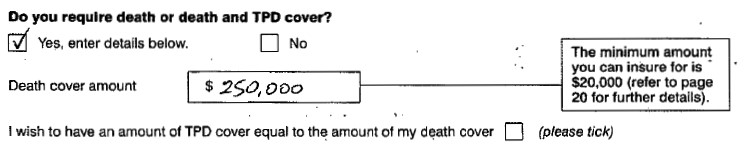

33 The advisor recommended that the insurance be arranged through superannuation accounts. The appellants each signed application forms that had been provided by Connelly Temple and were completed by the advisor. Mr Riseley contributed $6,000 and Mrs Riseley contributed $4,000. As can be seen from the form which is reproduced in part below, in response to the question, “Do you require death or death and TPD cover?”, each applicant answered “Yes” and specified a “Death cover amount” of $250,000. There was a further question: “I wish to have an amount of TPD cover equal to the amount of my death cover”. For each appellant, the box next to that further question was not ticked: J[14].

34 As an aside, it can be mentioned at this stage that the appellants complain that ambiguity arises from the way in which the form was presented. The ambiguity is said to be that a binary option of “yes” or “no” was given for the question “Do you require death or death and TPD cover?” which admits of three possible answers, being “no”, or “yes, death only”, or “yes, death and TPD”. There is, however, no ambiguity there because on a fair reading and proper analysis, in particular taking into account and giving effect to the notation “enter details below”, the question only admits of two answers, namely, “no”, or “yes, death or death and TPD, the details of which will be given below”.

35 It might also be said that ambiguity arises from the pre-printed statement “I wish to have an amount of TPD cover equal to the amount of my death cover” and the tick-box adjacent to it. That is because if TPD cover was required but not at the same amount of the death cover, it is not apparent what answer could be given other than to leave the box un-ticked in the expectation that an opportunity to reflect what was really sought would be given further down in the form. However, there was no other place on the form to indicate such a requirement. It is thus tolerably clear that if TPD cover was sought, it could only be sought in the same amount as death cover; that is all that was on offer by way of TPD cover. Thus, if TPD cover was sought the box had to be ticked, and the appellants or their advisor failed to do so.

36 In any event, the appellants say that the amount of TPD cover that they wanted and intended to apply for was $250,000, i.e., the same as the death cover. It is therefore inexplicable how they could have seen the form to be ambiguous; it asked the very question that conformed to their needs but they failed to tick the box to indicate those needs. There was certainly no ambiguity in the intention that they conveyed by not ticking the box.

37 Those conclusions on the ambiguity of the form are ultimately of little consequence because, as will be seen, the appellants were given welcome letters and then regular notice in the form of statements over a number of years that recorded that they had no TPD cover. Thus, even if the form was ambiguous it could hardly be said that such ambiguity gave rise to any unreasonable or unfair “decision” by the trustee as contemplated by s 14(2) of the Complaints Act.

38 Returning now to the narrative, after the forms were lodged, in March 2000 the appellants were sent welcome letters by Connelly Temple. The letter to Mr Riseley relevantly provided the details of an investment that had been accepted and the letter stated clearly as to Insurance Type, “Death Only” and Sum Insured, “$250,000.00”: J[15]-[16].

39 In Mrs Riseley’s welcome letter there was no information about insurance but there was a request for further information from her. The information was provided and, with effect from January 2000, the appellants both had $250,000 in death cover which was paid for using the contributed funds and returns on investing the balance: J[17], [19]-[20].

40 The appellants received regular reports and information as to the balance of their superannuation accounts all of which showed that the insurance coverage was for death only: J[20].

41 After a number of years, further monthly contributions were also requested to be made and were then made by the appellants to ensure that the accounts were put into sufficient funds to meet the cost of the insurance. However, the making of the additional contributions became too burdensome and were not continued: J[21]-[22].

42 In November 2014, Mr Riseley’s lower left leg was amputated: J[39]. That is relevant because Mr Riseley later said that had he had the TPD cover he believed he had, he would have been entitled to a payment under the policy.

43 In December 2016, the superannuation accounts of the appellants with Connelly Temple were closed and moved to “a brand new Suncorp Super account”. The death cover insurance appears to have lapsed before the rollover to the new accounts: J[23]. There is no dispute that Suncorp is now answerable for any conduct of Connelly Temple about which the appellants complain.

44 It was in February 2017 that the appellants took the first steps that led to the complaints when they emailed customer service at the then trustee of the fund. The email set out that that they had required a $250,000 death and TPD policy, the advisor had recommended the policy, there would only be a $10,000 payment and that the policy would be self-funding, that they believed they were misled, and they intended to call on the advisor to support their claims: J[24].

45 In June 2017, Mr Riseley sent a further letter of complaint by email and post where he particularised his complaint. He said, among other things, that he and Mrs Riseley never received an acceptable reason as to what “churned up” their initial capital. He also asked for a complete audit trail and a signed copy of their initial policy: J[25].

46 In July 2017, a Suncorp customer relations specialist responded to Mr Riseley. Relevantly, the response was that the advisor was licensed under MLC and any concern Mr Riseley had over the advice provided by the advisor should be referred to MLC: J[26].

47 It is useful to pause at this point to note that the advisor was not party to, nor did the advisor participate in, any dispute resolution process or proceeding despite his key role in the events that led to the dispute. The advisor also provided no evidence in circumstances where the appellants’ initially said that they would call upon the advisor to support their claim, and only the advisor could give evidence to support the appellants’ position that they had required a $250,000 death and TPD policy.

48 In August 2017, Suncorp was notified that a dispute had been lodged with the Financial Ombudsman Service. The dispute was summarised again by Mr Riseley, at this point eschewing any complaint against the advisor but rather that they were misled by “your company”: J[27]-[28]. There were further exchanges that need not be detailed here: J[31]-[36].

49 In its response to the Ombudsman, Suncorp maintained the distinction between the advice provided by the advisor for which Suncorp disclaimed responsibility and its responsibility to administer the accounts in accordance with instructions and the terms of the fund. As to the latter, the position of Suncorp was that there had been regular annual reporting to Mr and Mrs Riseley and financial information was provided as to how the funds had been applied and the premiums for the death cover insurance charged, the accuracy of which was never challenged by the appellants. In effect, it was Suncorp’s position that the accounts had been administered in accordance with their instructions and the fees and charges that had been charged were permitted under the terms of the trust instrument, were reasonable and had been fully disclosed at all times: J[37].

Proceeding before the Tribunal

50 In November 2017, the complaints of the appellants were referred to the Tribunal. In the form by which the appellants registered their complaints, they said that they had no reason to suspect anything other than what the advisor had presented to them. They then set out that they had been deceptively dealt with at the time they were sold their policy and reiterated that they believed that the “Provider” misrepresented how far the $10,000 would go, that they believed they had death and TPD cover, and that they should have been informed that they only had death cover: J[41]-[42].

51 The term “Provider” derived from the form as a reference to the party complained against. It is, however, apparent that the appellants were referring to the advisor. They did not identify any conduct of the trustee that caused them to be misled: J[43].

52 Sometime later in April 2019, the Tribunal communicated to Mr Riseley its understanding of the complaint. That understanding was that Mr Riseley sought the reinstatement of the death cover and payment of the TPD benefit: J[45].

53 In a wide-ranging response, Mr Riseley stated what he wanted, namely: a credit for undeclared trailing commissions, payment appropriate for the loss of his leg, and explanation of how they were sold a policy that would provide life and TPD cover for a once-off payment of $10,000. He also requested the “formula/evidence” used by MLC as a basis for the policy: J[46].

54 At no point was any part of any document provided by the trustee identified as containing statements to the effect attributed to the advisor: J[47].

55 In February 2020, Asteron Life & Superannuation Ltd (the insurer) (the third respondent in this proceeding) was given notice of joinder to the complaint by the Tribunal, and Suncorp and the insurer were requested by the Tribunal to provide a number of documents relating to the complaint: J[50].

56 Detailed information was then given to the Tribunal by Suncorp and the insurer. The primary judge summarised this information by saying that there was a long history of dealings over many years with the trustee concerning the insurance arrangements during which regular statements in which the cover that was provided was consistently described as death cover. There was no indication of any complaint being raised until 2015, some 15 years after the arrangements were made, at which time it was said that the advisor had told the appellants that the initial contributions were all that would be required and that the cover would be death and TPD cover. There was no basis articulated for any claim that the trustee (as distinct from the advisor) did anything at any time to suggest that the accounts and the attached insurance arrangements would operate in the manner in which it was alleged that the advisor had described them. There was no identification of any basis upon which the actions of the advisor might be attributed to Suncorp as trustee: J[52].

The May 2020 notice letters

57 It was in the circumstances described above that, on 6 May 2020, the Tribunal gave notice to the appellants that the Tribunal was considering exercising its power to treat the complaints as withdrawn.

58 The Tribunal summarised Mr Riseley’s various articulations of his complaint, which the appellants accepted in their submissions as fairly reflecting their complaints:

Specifically, you consider the circumstances unfair and unreasonable because:

• You and your wife were deceptively dealt with at the time you were sold the policy;

• the provider misrepresented the requirements of the policy and Fund membership to you and your wife;

• the policy you and your wife agreed to was for death and TPD, however you and your wife have been provided with a death only policy;

• the Fund had over 15 years to rectify the circumstances and provide you and your wife with a death and TPD policy;

• the Fund should have advised you and your wife of the death only cover;

• you and your wife queried the costs and commissions you were paying on your respective member accounts.

59 Background matters and Suncorp and the insurer’s position were summarised, and then the Tribunal set out its analysis. The Tribunal noted the following:

Notwithstanding your comment that the policy you and your wife agreed to was for death and TPD, and your expectation was of being provided with, and having TPD cover, without having complaint material to show you applied for TPD cover, the Tribunal is not able to arrive at a sound conclusion about whether you should have been provided with TPD cover.

To your comments that the Fund had over 15 years to rectify the circumstances and provide you and your wife with a death and TPD policy; that the Fund should have advised you and your wife of the death only cover; and that you and your wife queried the costs and commissions being deducted from your respective member accounts, the Tribunal notes the following:

• by way of annual member statements mailed to your current postal address during your membership with the Fund, the Fund provided you and your wife with information explaining and detailing your account and your benefits and entitlements with the Fund.

• The annual member statements provided you with information about the financial movement in your account, including details about the ongoing fees and charges, taxes and the insurance premiums being deducted to cover the cost of cover, and details about the investment performance.

• The annual member statements show you had cover in place for death.

To your comment that you and your wife were deceptively dealt with at the time you were sold the policy and that the provider misrepresented the requirements of the policy and Fund membership to you and your wife, and that you were advised your initial $6,000.00 contribution would provide you with insurance cover and a superannuation benefit into your retirement, from the material available, the Tribunal notes by way of the annual member statements the Fund regularly informed you of the costs associated with your account, informed you of the insurance premiums deducted from your account and informed you of the investment performance of your account. The Fund also notified you when your account could no longer cover the cost of your insurance cover.

Notwithstanding that you applied to join the Fund whilst travelling, the Tribunal notes your application and the applications key feature statement provided you with information about the product, and the Tribunal notes the Fund provided you with information about your account and membership benefits in your annual member statements. To the information provided to you the Tribunal is of the opinion it is important for members of superannuation funds to avail themselves of fund information at the time it is provided to them, and it is important for fund members to put in place arrangements to suit personal needs.

To the resolution you seek and to your expectation for a retirement benefit, the Tribunal has been unable to find that you or your wife applied for TPD cover and finds your initial contribution of $6,000.00 and subsequent contributions did not provide for the ongoing cost of your insurance cover with the Fund. The Tribunal also finds that given the costs associated with the management of your account, your account did not provide you with a benefit for your retirement.

For the purposes of section 22(3)(b) of the Act, the Tribunal is of the opinion the expression ‘lacking in substance’ means the complaint brought before the Tribunal is unsupported by the evidence.

Based upon this interpretation, the Tribunal is of the view this complaint should be withdrawn under section 22(3)(b) of the Act as lacking in substance because:

• the evidence available does not indicate you or your wife applied for TPD cover with the Fund; and

• from the evidence available to the Tribunal, your insurance cover with the Fund ceased on 13 September 2015; and

• by way of annual member statements, the Fund regularly disclosed to you the benefits and entitlements, investment performance and costs associated with your account; and

• your initial contribution of $6,000.00 and subsequent contributions, and the investment performance did not offset the management of your account to provide you with a benefit in your retirement.

60 The Tribunal also invited Mrs Riseley to make any comment on why she considered that her complaint should not be withdrawn. The letter to Mrs Riseley was materially the same as the letter to Mr Riseley.

61 Mr Riseley responded to the Tribunal’s letter by reiterating his complaint and relevantly saying that:

It is not mine or my Wife’s intentions to withdraw our claim on Suncorp. We have at all times been open to negotiation and a fair settlement, our allegations and losses are real, and a legitimate claim, we had been taken advantage of by a company who obviously were at best, deceptive in actions and behaviors. [sic]

…

We still are keen to be rid of the anxiety and stress associated with pursuing this matter and are open to a negotiated settlement, we want the $4,000 and the $6,000 a total of $10,000.00 returned/refunded to us with the interest we could of earned on that $10,000.00. The interest rate? [sic]

The Tribunal’s decision

62 On 15 May 2020, the Tribunal sent a further letter to Mr Riseley with an attachment setting out its reasons, and materially the same letter and attachment to Mrs Riseley. After setting out background matters in essentially the same way that it had done in the notice letters, the Tribunal set out its analysis relevantly as follows (with emphasis added to highlight the wording particularly said to give rise to the ground of review maintained on appeal):

The Tribunal can only return the Complainant to the position he would be in if not for error. In the circumstances of this complaint, the Tribunal notes the complaint material indicates the Complainant applied for Death cover only in his application to join the Fund. The complaint material does not show the Complainant applied for TPD cover in his application to join the Fund or during his membership with the Fund. Without corroborating evidence, the Tribunal is not able to arrive at a sound conclusion about whether the Complainant should have been provided with TPD cover.

…

The Tribunal finds no new material was provided by the Complainant to show that he applied for TPD cover.

63 The Tribunal then expressed the following conclusions (with emphasis added):

Based on all the information and documentation on file,

• there is no evidence to show the Complainant applied for TPD cover with the Fund; and

• the evidence shows that the Complainant’s insurance cover with the Fund ceased on 13 September 2015; and

• the evidence shows that the Fund regularly disclosed the benefits and entitlements, investment performance and costs associated with the account to the complainant; and

• there is no evidence to show that the initial contribution of $6,000.00, along with the investment performance, was intended to offset the management of the account and provide the Complainant with a retirement benefit.

Primary judgment

64 Five review grounds were advanced by the appellants at first instance, all of which were dismissed. Only ground 2 is the subject of appeal so the primary judge’s treatment of the others can be put to one side.

65 Ground 2 concerned an alleged misunderstanding by the Tribunal of the nature of its task under s 22(3)(b). It alleged error by the Tribunal in reasoning that it was necessary for the applicants to show, prior to any conciliation and review, that there was “evidence” to establish that (a) they had applied for TPD insurance; and (b) it was intended that their initial contributions would offset the management of the accounts and provide a retirement benefit: J[87].

66 The ground focussed upon particular aspects of the reasons given by the Tribunal. It was said that they revealed that the Tribunal engaged in an evaluative process of all the material advanced and formed its own view that there was a lack of substance in the complaints. This was said to be an exercise of the Tribunal’s ultimate task on review and was not a proper exercise of the statutory power to treat the complaints as withdrawn: J[88].

67 The submissions on this ground were said to have two themes. First, it was said that the Tribunal’s function was to gather materials and pass them on to the trustee to obtain answers and only undertake its evaluation after that process had been undertaken. Secondly, it was said that the Tribunal required Mr and Mrs Riseley to establish too high a standard that the complaints had substance. It was said that s 22(3)(b) called for a threshold assessment of the merits that was low and the Tribunal erroneously applied a high standard by inquiring into whether Mr and Mrs Riseley would ultimately succeed: J[89]-[91].

68 The first theme is not pressed, but the second is pressed on appeal. The second theme focussed upon the statements in the course of the Tribunal’s reasons set out at [62]-[63] above, in particular “corroborating evidence”, “sound conclusion” and “no evidence”.

69 The primary judge took the view that these statements must be considered in the context of the Tribunal’s reasons as a whole, particularly the section headed “The Tribunal’s analysis”. That analysis began by describing the form of the Tribunal’s ultimate power. The reasons that followed, in effect, considered the available material and looked forward to when a review would be conducted and considered what would happen, taking Mr and Mrs Riseley’s material at its highest. The reasoning was to the effect that as there was no real basis for the complaint as against the trustee (or the insurer), as distinct from the advisor, the power to treat the complaints as withdrawn should be exercised: J[97].

70 The primary judge went on to say that reference to the outcome that would follow “without corroborating evidence” was a way of expressing the problem that arose because there was no material of the relevant kind pointed to by Mr and Mrs Riseley. It was looking forward to the type of consideration that would be undertaken on review and pointing out what would be the necessary conclusion if there was nothing to “corroborate” a claim that Mr and Mrs Riseley should have been provided with TPD cover (that is, it was unreasonable for a decision to be made to that effect): J[99].

71 The primary judge noted that the word “corroborate” was perhaps used inaptly but that nevertheless it was apparent that it was describing an absence of any material that could lead to a sound conclusion that Mr and Mrs Riseley should have been provided with TPD cover: J[99].

72 The primary judge then noted that reasoning in that manner was not to undertake the kind of adjudication that would ultimately be undertaken on review. It was “to look forward to what would happen at that point as a way of exposing that the claim lacks substance because there was no material to support it.” The appellants say that this reasoning is in error and is the crux of the appeal. The primary judge added that the observation is entirely correct in circumstances where the complaints by Mr and Mrs Riseley pointed only to the conversations with the advisor and made assertions as to matters that were not to be found in any of the documents: J[100].

73 The primary judge said that it is not the case that the power conferred by s 22(3)(b) must be exercised, in effect, on an assumption that the alleged factual basis for the complaint will be established. His Honour added that no doubt it will be difficult for the Tribunal to “think” that a complaint lacks substance where there is a contest on the evidence or there is sufficient evidence to establish a basis for a claim but an issue as to whether the available material is sufficient to conclude that a decision was unreasonable or unfair. His Honour took the view that there was no error of law or jurisdictional error where the Tribunal thinks a complaint lacks substance on the basis of an evaluation that the available material lacks substance, was devoid of credibility, was mere assertion or was supported by material that, even taken at its highest, would not persuade the Tribunal that a decision was unfair or unreasonable. Nor was a list of that kind capable of being exhaustive. All was said to depend upon the circumstances: J[105].

74 In addition, the primary judge noted that the repository of the statutory power was the Tribunal and the power was conditioned on what the Tribunal “thinks”. It was said that the usual qualification of reasonableness would no doubt apply. Also, the section required the Tribunal to form a view as to whether it thinks the complaint is lacking in substance and to do so as the repository of a statutory power to determine whether a decision to vary or set aside the decision should be made on the basis of its assessment as to what is required to place the complainant in a position that removes unfairness or unreasonableness that the Tribunal has determined to exist: J[106], [109].

75 In that context, the question involves an evaluation as to whether the complaint has sufficient substance to justify the complaint proceeding to conciliation, and if not there resolved, to review for the purpose of considering whether to exercise that statutory power: J[109].

76 The primary judge added finally that the proper exercise of the statutory power conferred by s22(3)(b) no doubt required due consideration to be given to the fact that the purpose of conferring a right to conciliation and review was for the merit of the basis for the complaint to be evaluated by processes of that kind. For that reason, it may be expected that the power would only be exercised taking due account of whether there was material that had sufficient substance: J[111].

Ground of appeal and notices of contention

77 The appellants advance the following ground of appeal, which has two sub-grounds:

The trial judge erred by failing to find that the Superannuation Complaints Tribunal erred by:

a. requiring that the appellants show that there was evidence that they had each applied for insurance cover for total and permanent disablement, and that it was intended that their initial contributions would offset the management of their accounts and provide a retirement benefit; and

b. assessing the merits of the complaint rather than determining whether the complaint was ‘trivial, vexatious, misconceived or lacking in substance’; and

thereby asked itself the wrong question when performing its function under s 22(3)(b) of the Superannuation (Resolution of Complaints) Act 1993 (Cth).

78 Suncorp and the insurer also each filed a notice of contention that the judgment should be affirmed on grounds other than those relied on by the primary judge. The notices go to the question of materiality. The notices are the same and provide:

1. The Appellants failed to demonstrate that the purported errors of law of the Superannuation Complaints Tribunal (the Tribunal) could realistically have made any difference to the Tribunal’s decision.

2. None of the purported errors of law of the Tribunal amounted to a material error.

79 In view of the conclusion on the ground of appeal, the notices of contention fall away.

The appellants’ contentions

80 The appellants’ submissions are conveniently identified in two parts.

81 First, with reference to various provisions of the Complaints Act which demonstrate the centrality of the conciliation of complaints, the appellants submit that the Tribunal’s primary statutory function is to facilitate such conciliation and that it is only if conciliation fails that its secondary statutory function arises, namely to review and determine the complaint.

82 The appellants submit that the Tribunal asked itself whether the evidence before it supported the conclusion that the appellants’ complaint had sufficient prospects of achieving a favourable result from the Tribunal’s secondary statutory function, the process of review; in undertaking the exercise, the Tribunal failed to perform its primary statutory function, being the provision of a mechanism for the conciliation of a complaint in a manner that is fair, economical, informal and quick.

83 The appellants submit that the purpose of the Complaints Act is to promote the resolution of complaints about “unfair” and “unreasonable” decisions of trustees by means of alternative dispute resolution. Given the scope and purposes of the Complaints Act, its terms ought to be construed beneficially, and, consistent with that approach, the expression “lacking in substance” should not be construed in a sense that readily prevents aggrieved complainants from accessing the mechanism of conciliation provided by the Complaints Act.

84 Secondly, the appellants submit that the Tribunal considered the contentions of the parties, weighed the evidence available, and reached a conclusion as to the merits of the complaints. This assessment went well beyond an assessment of whether the complaints were “trivial, vexatious, misconceived or lacking in substance”. Instead, the Tribunal performed, at a preliminary stage, an abbreviated exercise of its power under s 37(3) of the Complaints Act to assess the evidence, and consider and then affirm, vary or set aside the decision under review. This is demonstrated in part by the Tribunal’s reference to the limitation of its powers at the review stage under s 37(5). The appellants submit that, in effect, the Tribunal replaced “lacking in substance” with “unsupported by the evidence”, which is in error.

85 The appellants submit that the test of “lacking in substance” provides a mechanism by which the Tribunal’s resources may be preserved and respondents not vexed by complaints that are unimportant or insignificant, or complaints that have no basis in reality or fact.

Consideration

The applications before the primary judge

86 Before each ground is considered it is helpful to consider the nature of the review that each application invoked.

87 First, review under s 5(1)(f) of the ADJR Act requires there to be an error of law. In Australian Broadcasting Tribunal v Bond [1990] HCA 33; 170 CLR 321 at 353, Mason CJ (Brennan and Deane JJ agreeing, Toohey and Gaudron JJ saying much the same at 384) said in relation to s 5(1)(f):

A decision does not “involve” an error of law unless the error is material to the decision in the sense that it contributes to it so that, but for the error, the decision would have been, or might have been, different. The critical question on this aspect of the case is whether, but for the alleged error of law on which the respondents rely, the decision might have been different by reason of the possibility that the Tribunal would not have made the findings of fact relating to the settlement in the terms in which they were made.

88 The appellants were thus required to establish an error of law by the Tribunal that was material to its decision.

89 Secondly, an application under s 39B of the Judiciary Act for a writ of certiorari quashing the decision of the Tribunal and a writ of mandamus requiring the Tribunal (or its successor) to consider the complaint according to law requires the establishment of jurisdictional error. In Craig v South Australia [1995] HCA 58; 184 CLR 163 at 179, Brennan, Deane, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ held that if an administrative tribunal falls into an error of law which causes it to identify a wrong issue or to ask itself a wrong question and the tribunal’s exercise or purported exercise of power is thereby affected, it exceeds its authority or powers. Such an error of law is jurisdictional error which will invalidate any order or decision of the tribunal which reflects it.

90 In MZAPC v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2021] HCA 17; 390 ALR 590 at [29], Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane and Gleeson JJ explained that to say that a decision is affected by jurisdictional error is to say no more and no less than that the decision-maker exceeded the limits of the decision-making authority conferred by the statute in making the decision. The relevant decision in this proceeding is the decision by the Tribunal under s 22(3)(b) to treat the complaint as withdrawn.

91 In Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 34; 264 CLR 123 at [30]-[31] it was explained by Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ that the threshold of materiality must be met for jurisdictional error to arise; a breach of a condition is not material unless compliance with the condition could have resulted in the making of a different decision. In MZAPC it was held (at [60]) that where materiality of a breach of an express or implied condition of a conferral of statutory decision-making authority is in issue in an application for judicial review of a decision on the ground of jurisdictional error, the onus of proving by admissible evidence on the balance of probabilities historical facts necessary to satisfy the court that the decision could realistically have been different had the breach not occurred lies unwaveringly on the applicant.

92 The point of setting out the above is that both applications lead to essentially the same analysis. The parties did not argue the applications differently. Also, if it is found that the Tribunal had erred, the question of materiality of the decision under s 22(3)(b) to withdraw the complaint is relevant to both applications.

The Tribunal’s statutory task

93 There is no substance to the appellants’ submission that there is a hierarchy to the tasks of the Tribunal, the primary task being the conciliation of complaints and the secondary task being the review and determination of complaints. The process before the Tribunal, as identified above (at [27]), can be analysed as constituting three phases or stages, but there is nothing in the Complaints Act to suggest that conciliation of complaints is more important than, or in some other way to be regarded as “primary” relative to, the other stages or other tasks.

94 The Complaints Act, as the long title identifies, concerns the “resolution” of complaints. Such resolution can occur either by conciliation or, if conciliation fails, by review and determination. It can be accepted that conciliation is an important component of the statutory scheme. The Tribunal’s objectives and functions as identified in ss 11 and 12 give apparently equal weight and importance to conciliation and, if conciliation fails, to review and determination.

95 As identified above (at [15]), previous Full Court authority, which was not challenged in the appeal, has held that the Tribunal’s obligation under s 16 to take reasonable steps to help a complainant to make a complaint does not extend to an obligation to help a complainant to present a complaint at the determination stage. Since the obligation of the Tribunal to try to settle a complaint by conciliation under s 11 does not arise unless a complaint has been made to the Tribunal, it has not been withdrawn and the Tribunal is satisfied that the Tribunal can deal with the complaint under the Complaints Act, on the same reasoning s 16 does not impose any obligation on the Tribunal to assist a complainant to put or assert that complaint in the conciliation of the complaint. Section 16 is therefore not a basis for elevating the importance of conciliation over review and determination.

96 That is not to say, however, that the Tribunal is not obligated to assist a complainant with conciliation. The Tribunal must “try to resolve” complaints by conciliation (s 12(1)(a)) by providing mechanisms that are fair, economical, informal and quick (s 11), and inevitably the obligation to inquire into a complaint and try to settle it by conciliation (s 27) will entail helping the parties to try to reach a settlement. Those obligations are, however, part of the conciliation function, and do not elevate conciliation above other functions.

97 Finally on this aspect, as identified above (at [28]), the power under s 22(3)(b) to treat a complaint as if it had been withdrawn can be exercised at any time, i.e., before conciliation, during conciliation, after failed conciliation or during review. That does not suggest that the grounds for the exercise of that power, i.e., that the Tribunal thinks that the complaint is trivial, vexatious, misconceived or lacking in substance, are to be construed with reference to only or even primarily the conciliation function; those grounds must be construed with reference to all functions that may follow the point in time at which the power is considered to be exercised.

Lacking in substance

98 The phrase “lacking in substance” has been interpreted in different ways in different statutory contexts. See, for example, Nagasinghe v Worthington [1994] FCA 1387; 53 FCR 175 at 178 adopting Sir Ronald Wilson in Assal v Department of Health, Housing and Community Services (1992) EOC 92-409, State Electricity Commission of Victoria v Rabel [1998] 1 VR 102 at 107-9 per Ormiston JA and Manu Chopra v Department of Education and Training [2019] VSCA 298 at [134] per Tate, Whelan and Kyrou JJA. However, as explained in Owners Corporation of Strata Plan 4521 v Zouk [2007] NSWCA 23; 69 NSWLR 61 at [41] per Ipp JA (Beazley and Bryson JJA agreeing) and Rabel at 107, authorities considering those words in other statutory contexts are not of assistance in determining the meaning of the words in the particular statute before the Court. The words must therefore be construed in the context of the Complaints Act, not other legislation.

99 In McAtamney v Superannuation Complaints Tribunal [2016] FCA 1062, as in the present case, the applicant sought review of the Tribunal’s decision under s 22(3)(b) to treat the complaint as withdrawn on the basis that it was lacking in substance. In considering the nature of the statutory task under that provision, North J reasoned as follows:

(1) In the same way that the Tribunal is required, when making a determination under s 37, to decide for itself whether the outcome of the trustee’s decision was fair and reasonable, so it must, when considering whether to treat the complaint as withdrawn under s 22(3)(b), form a view itself whether the complaint that the decision was unreasonable or unfair, lacks substance: at [133].

(2) Section 22(3)(b) is designed as a mechanism to avoid the need for conciliation and review when those processes are not warranted by the weakness of the complaint: at [134].

(3) The role of the Tribunal is to assist superannuation fund members and to ensure fair dealing with them by superannuation fund trustees; the Tribunal thus has a function which is rather different from the usual function of most administrative Tribunals in that it is focused on assisting one party to a transaction by ensuring that that party has been dealt with fairly and reasonably: at [135].

(4) The Tribunal’s function is not merely to gather information from the applicant, pass it on to the trustee and then report back to the applicant the answers provided by the trustee; the Tribunal was obliged to evaluate the material provided by the trustee and make an assessment whether there was substance in the complaint that the decision or conduct in question was not fair or reasonable: at [137].

100 With respect, there is no error in the approach adopted in McAtamney. Equally, there is no error in the primary judge’s reliance (at J[68]) on McAtamney in reasoning that if a complaint is lacking in substance it means that the complaint does not have enough substance to justify it proceeding to conciliation and review “when those processes are not warranted by the weakness of the complaint”. That means, as the primary judge identified (at J[99]-[100]), that the exercise is forward-looking. It is forward-looking as to what could happen at conciliation or, failing that, adjudication. If there is no substance to the complaint in the sense that it is so lacking in merit or foundation as to put the trustee to any serious consideration of compromise during conciliation or to possibly lead to an adjudication in the complainant’s favour, then it is lacking in substance; in the words of the primary judge (J[99]), if the “necessary conclusion” is that the complaint “would” fail then it is lacking in substance.

101 Thus, a complaint may be found to be lacking in substance if it fails to disclose a basis for a possible resolution that the decision or conduct complained of was unfair or unreasonable, whether such resolution is in conciliation or review and determination. Such an absence of a basis to the complaint could be with reference to legal rights and obligations, e.g., if the complaint could not succeed even if all the factual allegations in support of the complaint were accepted as true, or with reference to the facts, e.g., if on the material available and likely to become available the factual assertions in support of the complaint would not be able to be established.

102 Seen in that way, there is no error in the Tribunal having had regard to what “the material indicates”, or what “the evidence shows”, or that “there is no evidence to show” some or other material element of the complaint, provided that it was doing that in a forward looking way as to what could happen in conciliation and review and determination, including the possibility of further investigation bringing further relevant material to light. The primary judge was correct (J[99]) that the Tribunal’s use of “corroborate” (as quoted at [62] above) was inapt, but what the Tribunal was really doing was “describing an absence of any material that could lead to a sound conclusion that Mr and Mrs Riseley should have been provided with TPD cover” (emphasis added).

103 The Tribunal had over a period of time engaged in correspondence with the appellants in which it had flushed out all relevant material that they might be expected to produce, and it had engaged in a similar process with the trustee and the insurer. It then engaged in a preliminary assessment in which it concluded that the complaint lacked substance because, in essence, there was no evidence to support essential elements of the complaint, i.e., that the appellants had applied for TPD cover and that there was an agreement or representation by the trustee that the initial capital contribution along with the investment performance would offset the management costs and provide a retirement benefit. The complaint was in substance one about the advisor’s conduct and it was not said that the advisor was in any way misled by the trustee. The only link to the trustee was the fact that the then trustee provided the application form. It was in the application form that the appellants had the opportunity to but did not apply for the TPD cover that they say that they thought that they had applied for and been given.

104 Also, the Tribunal’s reference in its decision to the powers that it has at the determination stage does not demonstrate that it applied the test that it would apply at that stage and was thus in error. Since the Tribunal’s powers are limited, a complaint that calls for relief that it is beyond the power of the Tribunal to give, or that the material (or evidence) could not support, is a complaint that would justifiably be regarded as lacking in substance – there could be no reasonable prospect of it being resolved favourably to the complainant; it would fail.

105 In the circumstances, the appeal must fail.

Conclusion

106 In light of the above, the ground of appeal is not made out. The question of materiality does not arise.

107 The appeal should be dismissed with costs.

108 The Court expresses appreciation for the able assistance of pro bono counsel for the appellants.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and eight (108) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Banks-Smith, Stewart and Cheeseman. |

Associate:

WAD 134 of 2021 | |

AUSTRALIAN FINANCIAL COMPLAINTS AUTHORITY LTD |