Federal Court of Australia

Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 224

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 42, ‘J[287]’ has been amended to ‘J[268]’. | |

In paragraphs 119, 131, and 166 ‘HDD’ has been replaced with ‘HHD’. |

ORDERS

VEHICLE MONITORING SYSTEMS PTY LTD Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave be granted to appeal from Orders 1 to 8 made on 9 July 2020 in proceeding NSD 75 of 2018 in terms of the draft notice of appeal provided to the Court on 5 February 2021.

2. The applicant forthwith file a notice of appeal substantially in accordance with the draft notice of appeal.

3. The appeal be dismissed.

4. The applicant pay the respondent’s costs of the application for leave to appeal and of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The applicant, Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd, seeks leave, pursuant to s 158(2) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (the Act), to appeal from a judgment of a single Judge of the Court who dismissed its appeal from a decision of a delegate of the Commissioner of Patents. The delegate dismissed the applicant’s opposition to Patent Application No 2013213708 (the 708 application) proceeding to grant in respect of claims 1 to 24 thereof.

2 The complete specification filed in support of the 708 application is entitled “Vehicle Detection”. The named inventors are Paul Carboon, Stephen Toal, and Sandy Del Papa. The field of the invention is vehicle parking compliance.

3 The claims defining the invention fall into four groups. First, there are claims to a vehicle detection unit (VDU) (claims 1 to 10, with claims 2 to 10 directly or indirectly dependent on claim 1). Secondly, there are claims to a method of vehicle detection (claims 11 to 19, with claims 12 to 19 directly or indirectly dependent on claim 11). Thirdly, there is a claim to a method for issuing a parking infringement notice (claim 20). Fourthly, there are claims to a system for detecting vehicle parking infringements (claims 21 to 28, with claims 22 to 28 directly or indirectly dependent on claim 21).

4 In its opposition proceeding before the Commissioner, the applicant advanced three grounds. The first ground was that the respondent is not entitled to the grant of a patent based on the 708 application or, alternatively, is only entitled to a grant in conjunction with another person. The second ground was that the claimed invention is not a patentable invention because, as claimed, it is not novel and lacks an inventive step. The third ground was that the claims do not comply with the legal requirements of s 40 of the Act.

5 The delegate found that claims 25 to 28 did not comply with s 40(3A) of the Act. At the hearing, the respondent indicated that it was prepared to abandon these claims. The delegate granted leave to the respondent to file amendments to reflect its decision. The delegate otherwise rejected the opposition.

6 The applicant elected to appeal to this Court against the delegate’s decision pursuant to s 60(4) of the Act. Following a five-day hearing, the primary judge dismissed the applicant’s appeal on all grounds: Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 408 and Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 961.

7 Section 158(2) of the Act provides that an appeal to the Full Court against the judgment or order of a single Judge of the Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from decisions or directions of the Commissioner does not lie except with leave.

The application for leave

8 The applicant’s application for leave is in respect of a single ground of appeal. The ground is that the primary judge erred in finding that the applicant had not established that the respondent is not entitled to the grant of a patent based on the 708 application. In essence, the applicant contends that its managing director, Fraser Welch, is entitled to be named as an inventor of the invention the subject of the 708 application. It contends that because Mr Welch is an inventor, and because the respondent has not derived title to the invention from Mr Welch, the respondent is not a person who, under s 15 of the Act, can be granted a patent.

9 In Genetics Institute Inc v Kirin-Amigen Inc [1999] FCA 742; 92 FCR 106 (Genetics Institute) the Full Court explained (at [13]) that this Court’s jurisdiction to grant leave pursuant to s 158(2) of the Act involves the exercise of a discretion that is not constrained by reference to any particular test. The Full Court nevertheless observed that the purpose of pre-grant opposition proceedings is to provide a swift and economical means of settling disputes that would otherwise need to be dealt with in more expensive and time-consuming post-grant litigation, namely revocation proceedings. The Full Court noted that pre-grant opposition proceedings have the potential to delay, improperly, the grant of a patent. Therefore, the Full Court reasoned, a “relatively stringent filter” for appeals to the Full Court under s 60(4) of the Act should be applied.

10 The Full Court said (at [23]):

23 We consider that the Full Federal Court should also exercise its discretion to grant leave to appeal under s 158(2) against a decision of a single judge of the Federal Court refusing to grant relief in a pre-grant opposition proceeding with care. Leaving aside applications for leave on a question of pure law in the context of essentially undisputed facts, and subject always to considerations of fairness and the interests of justice raised by a particular case, we think the contextual and policy matters to which we have referred will ordinarily require that leave to appeal against a decision rejecting a pre-grant opposition only be granted where the applicant has demonstrated a clear prima facie case of error in the decision appealed from, such that the likely effect of that decision would be to allow an invalid patent to proceed to grant.

11 In Pfizer Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [2006] FCAFC 190; 155 FCR 578 (Pfizer), the Full Court (at [10] – [12]) emphasised the importance of not laying down rigid rules that would restrict the exercise of the power in s 158(2) of the Act. Nonetheless, their Honours said (at [12]):

12 No doubt, where an unsuccessful opponent, after two hearings and where questions of fact, impression and judgment are involved, seeks leave to appeal, it may be appropriate to require the demonstration of a clear prima facie case of error on the part of the primary judge. …

12 When Genetics Institute and Pfizer were decided, the question before the Court in an appeal in pre-grant opposition proceedings was whether it was “practically certain” that a patent granted on an unopposed application would be invalid. That is no longer the test. The test is now whether, on the balance of probabilities, a ground of opposition to grant exists. This is the test that the Commissioner must apply in opposition proceedings (see s 60(3A)) and, as an appeal to this Court from the Commissioner’s decision is conducted as a hearing de novo (see New England Biolabs Inc v F Hoffman-La Roche AG [2004] FCAFC 213; 141 FCR 1 at [44]), the same standard of proof applies.

13 The significance of this change may not be limited, simply, to lowering the standard of proof for an opponent in opposition proceedings. The Full Court in Genetics Institute confronted the question whether a finding by a single Judge of the Court in pre-grant opposition proceedings could ground an issue estoppel in post-grant revocation proceedings raising the same issue for determination. The Full Court held (at [17]) that the two proceedings are sufficiently different to preclude the operation of issue estoppel principles. As the Full Court explained, a finding in pre-grant opposition proceedings—that it is not “practically certain” that a patent granted on an unopposed application would be invalid—would be inconclusive of the question whether, in revocation proceedings, the patent should be revoked, on the same ground.

14 The applicant argued that the change introduced by s 60(3A) of the Act has significance when leave to appeal under s 158(1) of the Act is being considered. It means that the primary judge’s ultimate finding on entitlement, made in the context of pre-grant opposition proceedings, might also raise an issue estoppel that would have the effect of finally determining its rights on the same issue should it bring post-grant revocation proceedings in reliance on s 138(3)(a) of the Act.

15 Supposing the primary judge’s decision to be wrong, the applicant submitted that substantial injustice would result if leave to appeal were to be refused, because the primary judge’s decision may operate to finally determine the question of entitlement it has raised and, should it be sued by the respondent for infringement, the decision would preclude the applicant from contesting that question in the infringement proceedings or in separate proceedings for revocation. The applicant also submitted that leave should be granted because the public interest in the integrity of the Register of Patents would be adversely affected by an invalid patent application proceeding to grant.

16 The respondent agreed that, following the introduction s 60(3A) of the Act, it is no longer clear that the applicant could raise, either defensively or by way of revocation proceedings, the question of entitlement determined in the pre-grant opposition proceedings. But, the respondent said, this is a matter that the applicant must have weighed up when deciding to commence its appeal from the delegate’s decision. In other words, it made a forensic decision and put itself in jeopardy. The respondent submitted that the considerations raised in Genetics Institute still apply. The applicant has had two levels of review and seeks to raise, again, questions of fact, or of mixed fact and law, that have been decided against it. Thus, according to the respondent, the applicant must demonstrate a clear prima facie case of error for leave to appeal to be granted.

17 What is more, the respondent submitted, a large part of the applicant’s present application is based on the contention that the primary judge should have accepted a particular account of a conversation, in circumstances where the account was given nine years after the event. The respondent submitted that this would involve an attack on concurrent findings of fact. We doubt the correctness of that proposition. Even so, the respondent submitted, if the applicant’s contention in this regard were to be accepted, it would make no difference to the outcome of the question of entitlement.

18 We are persuaded that leave to appeal should be granted. First, the proposed appeal raises consideration of some important aspects of the law with respect to entitlement. Secondly, one aspect of the proposed appeal is the proper construction of the complete specification of the 708 application, insofar as that question concerns the identification of the invention or “the inventive concept”. We observe that the primary judge’s identification of the invention or inventive concept differs from the delegate’s identification. For the reasons given below, we are satisfied that the applicant has demonstrated a prima facie error in relation to the primary judge’s determination of that question. This assumes importance because the identification of the invention or inventive concept sets the framework for determining the further question of contribution, and thus the ultimate question of entitlement. Thirdly, there is the public interest in maintaining the integrity of the Register of Patents.

19 We would add that, in exercising the power under s 158(2) of the Act in the present case, it is not necessary to reach a concluded view on the question of whether an issue estoppel would be available to the respondent in subsequent proceedings between the parties. Whether an issue estoppel is available should only be determined if, and when, that question arises. It is pertinent to observe, however, that the legal landscape has changed, and that earlier cases dealing with the question of leave should be read with that change in mind.

The complete specification

20 The complete specification lodged in support of the 708 application characterises the invention as relating to vehicle parking compliance, in particular to the “automated determination of notifiable parking events”. The specification says that vehicle parking is usually subjected to rules and regulations, and describes the shortcomings of “manual enforcement” (page 1, lines 19 – 34):

Enforcement of vehicular parking regulations can be the responsibility of either private or public agencies. Such enforcement is costly and time consuming. Typical enforcement involves a parking inspector manually inspecting all of the restricted spaces periodically, regardless of whether vehicles are actually present. Further, to identify a violation in a free time-limited zone requires that the parking inspector inspect the violating car at least twice, once to establish a time of arrival of the car (for example by chalking the tire of the car), and a second time once the permitted time period for parking has elapsed. Even in paid metered zones, such manual enforcement is inefficient as the parking inspector may fail to note an expired meter or ticket before the violating car departs, reducing the deterrent to infringers and denying fines revenue to the relevant body. It has been estimated that only 1 in 25 parking violations are identified by manual enforcement. Enforcement is made even more difficult when the spaces are distributed over a large area, such as a city block or a large, multi-level parking garage. Manual enforcement is also unable to provide historical data of parking usage, and such data is becoming of increasing importance to the implementation of parking supply and regulation.

21 The specification describes the invention as having four aspects:

(1) a VDU – page 2, lines 14 – 26 (the consistory statement for claim 1);

(2) a method for vehicle detection by a VDU – page 2, line 28 – page 2a, line 4 (the consistory statement for claim 11);

(3) a method for issuing a parking infringement notice (PIN) – page 4, lines 25 – 32 (the consistory statement for claim 20); and

(4) a system for detecting vehicle parking infringements – page 5, lines 5 – 19 (the consistory statement for claim 21).

22 The first aspect of the invention provides (page 2, lines 14 – 26):

... a vehicle detection unit comprising:

a magnetic sensor able to sense variations in magnetic field and for outputting a sensor signal caused by occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle;

a storage device carrying parameters which define notifiable vehicle space occupancy events;

a processor operable to process the sensor signal to determine occupancy status of the vehicle space, and operable to compare the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters in order to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred, and operable to initiate a communication from the vehicle detection unit to a supervisory device upon occurrence of a notifiable event, wherein the communication includes data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software.

23 As the specification emphasises, the first aspect of the invention provides for the VDU itself to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred: page 3, lines 1 – 2. However, this aspect of the invention is not limited to a VDU in which communications are initiated only upon the occurrence of a notifiable event. His Honour found that, by use of the word “operable”, the VDU only has to be capable of initiating such communications. His Honour noted that the specification describes the VDU initiating a communication by listening for a beacon and, upon detecting such a signal, sending a communication in response: page 9, lines 30 – 35. His Honour rejected the suggestion that the VDU is only “listening” for such a beacon when it has a notifiable event to report on.

24 When the VDU initiates a communication to the supervisory device upon the occurrence of a notifiable event, the communication must include data pertaining to the notifiable event and be in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software: page 2, lines 24 – 26. The primary judge found that the pre-population step means that data items pertaining to the notifiable event are transmitted directly into the infringement issuing software by the VDU without the need for a parking officer to take a step to do so.

25 The primary judge also found that, by this feature, the supervisory device is relieved of the processing obligation for any items of data that are communicated by the VDU concerning a notifiable event, other than processing of the kind that must always be done at the receiver end to return the data to its original form (such as by the removal of headers). His Honour concluded that the pre-population steps involve a choice designed to save power at the supervisory device end, and to impose the processing task on the VDU.

26 After identifying the second aspect of the invention—which, as the primary judge noted, is a method of vehicle detection involving use of the VDU characterised according to the first aspect of the invention—the specification describes, in general terms, various preferred embodiments of the VDU, so characterised.

27 One such embodiment is where the VDU communicates wirelessly directly with a portable supervisory device, such as a personal digital assistant carried by an inspector. The specification refers to this network topology as a transient middle tier or TMT. This is distinguished from a fixed middle tier or FMT, which is a fixed communications infrastructure connecting the VDU with a head office server, and the head office server with a supervisory device: page 3, lines 4 – 13.

28 Another preferred embodiment is where the VDU is operable to provide the information associated with the notifiable event to the supervisory device in a form in which the information can be pre-populated into the device itself: page 3, lines 15 – 27. The refinement introduced in this preferred embodiment seems to be that the infringement issuing software (referred to in the consistory statement) is run in the supervisory device itself.

29 Another preferred embodiment is where a plurality of VDUs communicate with a single supervisory device. The specification notes that, in this embodiment, the supervisory device is not required to possess the substantial power needed to make determinations about notifiable events for every VDU because, in accordance with the consistory statement, each VDU undertakes its own determination: page 3, line 29 – page 4, line 2.

30 Other described preferred embodiments are: the VDU is embedded in the roadway beneath the associated parking space (page 4, lines 4 – 5); the sensor of the VDU is a magnetometer able to sense variations in magnetic field caused by the arrival, presence, departure, or absence of a vehicle (page 4, lines 7 – 16); and the VDU is operable to receive updates to the parameters defining notifiable vehicle space occupancy events (page 4, lines 18 – 23).

31 After identifying the third and fourth aspects of the invention, the specification gives a detailed description of the invention with reference to Figures 1 to 8.

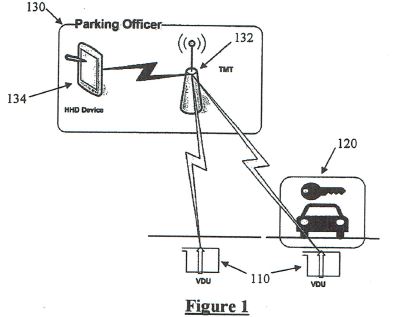

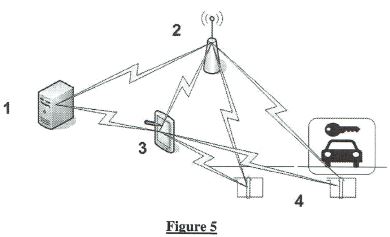

32 Figures 1, 2, and 5 illustrate, respectively: a network topology comprising a TMT in accordance with a preferred embodiment of the invention; a network topology comprising a FMT in accordance with an alternative embodiment of the invention; and a generalised network topology of a further embodiment of the invention.

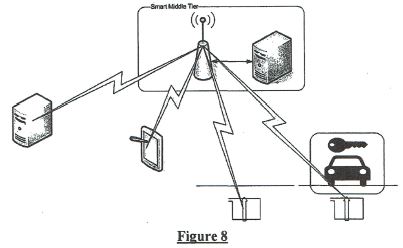

33 Figures 6 to 8 illustrate, respectively: the operation of a “smart” VDU in accordance with another embodiment of the invention; the operation of an “intelligent” VDU in accordance with yet another embodiment of the invention; and the operation of a “smart” middle tier together with “smart” VDUs, in accordance with a further embodiment of the invention.

34 Figures 3a to 3i illustrate cases which influence operation of the vehicle detection algorithm in distinguishing parking events from exceptions. Figure 4 is a flowchart illustrating operation of the vehicle detection algorithm.

35 The specification ends with 28 claims. As we have noted, claims 1, 11, 20, and 21 are independent claims representing the four described aspects of the invention:

1. A vehicle detection unit (VDU) comprising:

a magnetic sensor able to sense variations in magnetic field and for outputting a sensor signal caused by occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle;

a storage device carrying parameters which define notifiable vehicle space occupancy events;

a processor operable to process the sensor signal to determine occupancy status of the vehicle space, and operable to compare the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters in order to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred, and operable to initiate a communication from the vehicle detection unit to a supervisory device upon occurrence of a notifiable event, wherein the communication includes data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software.

…

11. A method for vehicle detection by a vehicle detection unit, the method comprising:

sensing variations in magnetic field caused by occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle, and outputting a sensor signal;

retrieving from a storage device parameters which define notifiable vehicle space occupancy events;

processing the sensor signal to determine occupancy status of the vehicle space, comparing the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters in order to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred, and initiating a communication from the vehicle detection unit to a supervisory device upon occurrence of a notifiable event, wherein the communication includes data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into an infringement issuing device.

…

20. A method for issuing a parking infringement notice, the method comprising:

a portable device establishing a transient wireless connection with at least one fixed vehicle detection unit (VDU);

the portable device obtaining from the VDU via the wireless connection data arising from a notifiable parking event magnetically detected by the VDU; and

the portable device pre-populating the data into infringement issuing software and generating a parking infringement notice using the pre-populated data obtained from the VDU.

21. A system for detecting vehicle parking infringements, the system comprising:

a plurality of vehicle detection units (VDUs) each associated with a respective vehicle parking space and storing parameters defining notifiable vehicle space occupancy events, each VDU configured to sense variations in magnetic field caused by occupancy of the associated vehicle space and determine by reference to the parameters whether a notifiable event has occurred, and operable to communicate wirelessly including wirelessly transmitting data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software;

a mobile supervisory device configured to wirelessly communicate with each respective VDU when brought within range, to receive information from the VDU arising from a notifiable parking event detected by the VDU, to pre-populate received data items into infringement issuing software and to generate a parking infringement notice using the pre-populated data items obtained from the VDU.

...

Entitlement: The primary judge’s reasons

36 The applicant’s opposition on the ground of entitlement was based on the content of conversations that were said to have taken place in 2005 and 2006. These conversations took place against the background that, in early 2005, the Maribyrnong City Council had commenced to trial the applicant’s system using in-ground sensors to monitor vehicle non-compliance with parking restrictions. The sensors detected changes in the Earth’s magnetic field when a vehicle entered a parking bay. This system was called the Parking Overstay Detection System (or the POD system) by its inventor, Mr Welch.

37 The system trialled by the Maribyrnong City Council required the use of three devices:

(a) an in-ground sensor;

(b) a handheld computer device (HHD) to receive infringement alerts from the in-ground sensor via a radio link which displayed details of the infringement to a parking officer, including a bay number, vehicle overstay time, vehicle entry time, time-limit, and location; and

(c) a ticket issuing device (an Autocite brand ticket issuing machine) that was used to generate PINs.

38 The trial revealed a problem, which was that the issue of PINs required the parking officer to manually enter the details into the Autocite ticket issuing machine. This led not only to a degree of frustration among parking officers, but also errors in transcription that could invalidate the PINs that were issued. The primary judge referred to this as the manual entry problem.

39 At around this time, the Maribyrnong City Council was interested in obtaining a new ticket issuing device. Mr Gladwin, who was the Manager of Parking and Local Laws at Maribyrnong City Council, knew that the respondent had expertise in ticket issuing machines because the Council had purchased some from the respondent and was using them to issue tickets for non-parking law enforcement purposes. The respondent’s device is called PinForce. Mr Gladwin facilitated Mr Welch contacting Mr Del Papa, who Mr Gladwin understood to be a senior salesman of the respondent.

40 The primary judge surveyed the evidence given by Mr Gladwin, Mr Welch, and Mr Del Papa. He noted that there was some dispute between the evidence given by Mr Del Papa on the one hand, and the evidence given by Mr Gladwin and Mr Welch on the other. He found that some evidence given by Mr Del Papa was untruthful.

41 The primary judge found that, in or about August 2005, Mr Welch communicated a proposal to Mr Del Papa (the Welch proposal), which is captured by the following evidence given by Mr Welch of a telephone conversation he had with Mr Del Papa:

Tom Gladwin and I have discussed the benefits of integrating PODS with a ticket issuing device. [The POD system] is currently displaying offence details to the officer on a PDA, the officer must read the details from our PDA and enter them manually into their Autocite. It would obviously be much better if the offence details went straight into the infringement application. Since you’re using PDAs and Maribyrnong is already a customer of yours I thought I should call you to see if you are interested in working together on this.

42 The primary judge found that the Welch proposal (at J[268]):

268 ... conveyed the notion that the POD system could be integrated with a ticket issuing device and solve the manual entry problem by providing offence details ‘straight into the infringement application’. Having regard to the context of the conversation, I find that this was a suggestion that the POD system could be adapted to operate in conjunction with SARB’s PinForce software. That is plainly how Mr Del Papa understood the communication at the time. The idea was expressed by Mr Welch in private, but it was no secret. The evidence indicates it was also raised by Mr Gladwin and Mr Reid.

43 The primary judge referred to the integration of the POD system ticket issuing software with a ticket issuing device, so that the infringement details were automatically entered into the ticket issuing software, as the integrated solution. As to this, his Honour said (at J[115]):

115 …the particular frustrations of parking officers familiar with operating [the] POD system and the knowledge and concerns of Mr Gladwin and Mr Welch, do not, of themselves, form part of the common general knowledge. By the priority date only four councils had implemented the POD system.

44 The primary judge found that the Welch proposal led Mr Del Papa and the respondent to develop the invention the subject of the 708 application. However, his Honour made the following finding, which is central to this appeal (at J[270]):

270 However, the message conveyed to Mr Del Papa was, at its highest, the idea that the POD system could possibly be adapted in the way suggested in the proposal. In my view the invention disclosed in the specification and the subject of the claims is not that obvious, high level idea, but rather a more prosaic, practical implementation. It is the reduction of that concept to a working apparatus that is the invention: Polwood at [33]. The solution to the manual entry problem involved arriving at a wireless system that balances the power saving considerations involved in the communication between remote devices that do not have connections to mains power. One factor in the balancing process was to enable the processor in the VDU to detect and determine an overstay (or notifiable event). Another was to require the processor to initiate a communication with a HHD (including in response to a wake-up call). A third was the decision to communicate data relating to the overstay (or notifiable event) to a HHD in a format that can pre-populate the infringement issuing software without additional formatting. Neither Mr Welch nor Mr Gladwin played any role in arriving at that solution.

45 On this basis, the primary judge rejected the applicant’s claim that Mr Welch should be named in the 708 application as the inventor or co-inventor of the invention.

46 In reaching this conclusion, the primary judge referred to the principles discussed in JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 1474; 67 IPR 68 (JMVB) (on appeal, JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd (formerly A’Van Campers Pty Ltd) v Camoflag Pty Ltd [2006] FCAFC 141; 154 FCR 348); and Polwood Pty Ltd v Foxworth Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 9; 165 FCR 527 (Polwood).

The Law

The notion of the “inventive concept”

47 Section 15 of the Act is the cardinal statutory provision for determining who may be granted a patent:

(1) Subject to this Act, a patent for an invention may only be granted to a person who:

(a) is the inventor; or

(b) would, on the grant of a patent for the invention, be entitled to have the patent assigned to the person; or

(c) derives title to the invention from the inventor or a person mentioned in paragraph (b); or

(d) is the legal representative of a deceased person mentioned in paragraph (a), (b) or (c).

(2) A patent may be granted to a person whether or not he or she is an Australian citizen.

48 Central to this provision is the identification of the “inventor” because it is by reference to the “inventor” that patent ownership is established.

49 However, the term “inventor” is not defined in the Act. The term “invention” is defined:

“invention” means any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention.

50 Notwithstanding this definition, the High Court has recognised that, both in ordinary parlance and in patent legislation (including the Act), “invention” is used in various senses.

51 For example, in Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Limited v Arico Trading International Pty Limited [2001] HCA 8; 207 CLR 1 the High Court held that, for the purposes of s 40(2) of the Act—then dealing with the statutory requirement that a complete specification must describe “the invention” fully—“the invention” is to be taken as meaning “the embodiment which is described, and around which the claims are drawn”: at [21]. This use of “the invention” is to be distinguished from the Act’s use of “invention” in s 18(1) which posits the requirements for a “patentable invention”.

52 Current Australian case law takes the “inventor”, for the purposes of s 15(1)(a) of the Act, to be the person who is responsible for—in the sense of the person (there may be more than one) who materially contributes to—the “inventive concept”: Polwood at [20], [59] – [66]; University of Western Australia v Gray (No 20) [2008] FCA 498; 76 IPR 222 (UWA) at [1419] – [1443], on appeal University of Western Australia v Gray [2009] FCAFC 116; 179 FCR 346 (UWA(FC)) at [218] – [269]; Kafataris v Davis [2016] FCAFC 134; 120 IPR 206 (Kafataris) at [60] – [75]. Recourse to the notion of the “inventive concept” signifies another dimension to the meaning of “invention”, as used in the Act.

53 The notion of the inventive concept, as it applies to the question of entitlement, appears to derive from Jacob J’s use of the expression in Henry Brothers (Magherafelt) Ltd v The Ministry of Defence and the Northern Ireland Office [1997] RPC 693 (Henry Brothers). This use was adopted, without comment, by Robert Walker LJ on appeal: Henry Brothers (Magherafelt) Ltd v The Ministry of Defence and Northern Ireland Office [1999] RPC [No. 12]. The latter case is now recognised as the leading modern authority in the United Kingdom on the question of entitlement: Collag Corp v Merck & Co Inc [2003] FSR 16 (Collag) at [70]. The notion is firmly entrenched as an aspect of that law.

54 It is possible that Jacob J’s deployment of the “inventive concept” was inspired by s 14(5)(d) of the Patents Act 1977 (UK) (the UK Act) which, in the context of specifying the requirements for a claim or claims in a specification, stipulates that the claim or claims must:

… relate to one invention or to a group of inventions which are so linked as to form a single inventive concept.

55 Section 14(5)(d), in turn, derives from Art 82 of the European Patent Convention:

The European patent application shall relate to one invention only or to a group of inventions so linked as to form a single inventive concept.

56 It is also possible that Jacob J’s use was inspired by the identification, in the United Kingdom case law, of “the inventive concept embodied in [a] patent” as the first step in a staged approach to determining the question of obviousness: Windsurfing International Inc v Tabur Marine (Great Britain) Ltd [1985] RPC 59 at 73 – 74; Pozzoli SpA v BDMO SA [2007] EWCA Civ 588; FSR 37 at [14] – [17].

57 Notably, in both these contexts, the notion of the “inventive concept” is deployed specifically with respect to the claims in the specification, not the specification more generally. When used with respect to the claims, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom has said that the inventive concept of a claim is synonymous with the “inventive core” of the claim: Actavis UK Ltd v Eli Lilly and Company [2017] UKSC 48; RPC 21 at [60] and [65].

58 Australian patent law is not informed by the same antecedents. For one thing, while unity of invention is required by s 40(4) of the Act, there is no provision corresponding to s 14(5)(d) of the UK Act, insofar as that provision contemplates a claim relating to a group of inventions linked so as to form a single inventive concept.

59 Further, as explained in Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Limited [2002] HCA 59; 212 CLR 411 and Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] HCA 21; 235 CLR 173 (Lockwood No 2), there are significant differences between Australian law and United Kingdom law with respect to the determination of the question of obviousness. One consequence of these differences was identified in Lockwood No 2 (at [64]):

64 Although the recognition of the need to identify an “inventive idea” justifying a monopoly is not new in Australia, the developments in the United Kingdom, which emphasise the need to identify the “inventive concept” in terms of “problem and solution”, have raised the threshold of inventiveness. This has been exemplified by a number of relevant English cases since 1977.

(Footnotes omitted.)

60 Notwithstanding the different underpinnings of Australian patent law, the notion of the inventive concept has been picked up in the Australian cases as the tool of analysis for determining questions of entitlement.

61 A question arises as to whether this adoption is apt or, indeed, even necessary. It is not a question, however, that need be explored in this appeal. The parties advanced their respective cases on the basis that the contested question of entitlement should be determined by reference to whether Mr Welch did contribute to the “inventive concept” of the 708 application. They each relied on the United Kingdom cases as informing the determination of that question. They proceeded on the two-stage inquiry referred to in those cases. The first stage is to identify the inventive concept or concepts in the patent or, as the case might be, the patent application. The second stage is to identify who came up with the inventive concept or concepts. This approach was endorsed by French J in UWA at [1418] and [1442], and accepted by the Full Court in UWA(FC) at [221], and in Kafataris at [62].

Identification of the inventive concept

62 In Markem Corp v Zipher Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 267; [2005] RPC 31 (Markem), Jacob LJ (with whom Kennedy and Mummery LJJ agreed) reasoned that questions of entitlement fall to be determined by reference to information in the relevant specification rather than the form of the claims.

63 As to how the inventive concept is to be identified, he said (at [102]):

102 It is not possible to be very specific about how this is to be done. But as a general rule one will start with the specific disclosure of the patent and ask whether that involves the use of information which is really that of the applicant, wholly or in part or as a joint owner. … What one is normally looking for is “the heart” of the invention. There may be more than one “heart” but each claim is not to be considered as a separate “heart” on its own. …

64 In that case, the Court of Appeal expressed agreement with the following observation of Christopher Floyd QC, sitting as a Deputy Judge of the Chancery Division, in Stanelco Fibre Optics Limited v Bioprogress Technology Limited [2004] EWHC 2263; [2005] RPC 15 (Stanelco) (at [15]):

15 It is clear that a mechanistic, element by element approach to inventorship will not produce a fair result. If A discloses a new idea to B whose only suggestion is to paint it pink, B should not be a joint inventor of a patent for A’s product painted pink. That is because the additional feature does not really create a new inventive concept at all. The feature is merely a claim limitation, adequate to overcome a bare novelty objection, but having no substantial bearing on the inventive concept. …

65 The same general approach, with its emphasis on the disclosure in the specification, and not merely the definition of the invention in the claims, has been adopted in this country. In Polwood, the Full Court said (at [33]):

33 … What constitutes the invention can be determined from the particular patent specification which includes the claims. In some cases, evidence can assist. In some cases, the reduction of a concept to a working apparatus by a person may not be part of the invention, in other cases it may be. For example, the construction of an apparatus may involve no more than carrying out the instructions in the specification. This would not normally entitle that person to joint inventorship. On the other hand joint inventorship may arise where the invention is in the apparatus itself, or where the person constructing the apparatus contributed to a different or better working of it which is then described and claimed.

66 Later, the Full Court said (at [60] – [61]):

60 The invention or inventive concept of a patent or patent application should be discerned from the specification, the whole of the specification including the claims. The body of the specification describes the invention and should explain the inventive concepts involved. While the claims may claim less than the whole of the invention, they represent the patentee’s description of the invention sought to be protected and for which the monopoly is claimed. The claims assist in understanding the invention and the inventive concept or concepts that gave rise to it. There may be only one invention but it may be the subject of more than one inventive concept or inventive contribution. The invention may consist of a combination of elements. It may be that different persons contributed to that combination.

61 In this case, the body of the specification and the claims describe two aspects of the invention, the concept and the apparatus to give effect to it. Both are described and claimed by Polwood as the patent applicant as inventive.

Contribution to the inventive concept

67 In IDA Ltd v University of Southampton [2004] EWHC 2107 (Pat); [2005] RPC 11 (University of Southampton), when reflecting on the fact that there may be more than one devisor of an invention, Laddie J said (at [35]):

35 … One person may shout “eureka” but, depending on the facts, the inventive concept may be a product of the non-severable contributions of a number of persons. In such a case, they are all inventors. …

68 When questions of entitlement arise, the Court is not concerned with whether the invention, as claimed, satisfies the requirements of a patentable invention. Rather, attention is directed to the “concept” as it is described. In Stanelco Christopher Floyd QC observed (at [15]):

15 … one must keep in mind that it is the inventive concept or concepts as put forward in the patent with which one is concerned, not their inventiveness in relation to the state of the art.

69 This approach is seen in JMVB where, in a passage approved by the Full Court in Polwood, Crennan J said (at [132]):

132 Rights in an invention are determined by objectively assessing contributions to the invention, rather than an assessment of the inventiveness of respective contributions. If the final concept of the invention would not have come about without a particular person’s involvement, then that person has entitlement to the invention. One must have regard to the invention as a whole, as well as the component parts and the relationship between the participants. …

70 It does not follow, however, that anyone who contributes to the invention is an inventor. In Henry Brothers (at 706), Jacob J observed that, in relation to a combination:

… One must seek to identify who in substance made the combination. Who was responsible for the inventive concept, namely the combination?

71 For example, it has been recognised that a person will not establish a claim to entitlement where his or her claimed contribution to the inventive concept is merely positing desiderata or making a vague proposal. In Stanelco, Christopher Floyd QC recorded the following submission by counsel for Stanelco (Mr Miller QC) (at [13]):

13 At one extreme, there are vague ideas and pipedreams—the sort of thing where someone says ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if we could do such and such’—but without any idea as to whether ‘such and such’ can in fact be done or how it might be done. That person will not be an actual devisor of an invention that is subsequently made by another—even though without the initial prompt of the invention might never have been made. At the other end of the scale there is the person who produces a fully worked-up proposal and an actual working embodiment of it. That person is clearly an actual divisor of the invention. …

72 This submission was accepted as a general proposition (at [14]):

14 I think Mr Miller is right to the extent that it is never going to be enough for an antecedent worker to rely solely on an initial prompt of the vague kind he refers to: a “but-for” approach would lead to all sorts of people being treated as inventors. But where the worker comes up with and communicates an idea consisting of all the elements in the claim, even though it is just an idea at that stage, it seems to me that he or she will normally, at the very least, be an inventor of the claim. What US patent law calls “reduction to practice” is not, it seems to me, a necessary component of a valid claim to any entitlement.

73 Although rejecting vague suggestions as capable of constituting material contributions to the inventive concept, the observation in the last two sentences of this quotation recognises, nonetheless, that invention may reside in the conception of an idea, without the need for reduction to practice.

74 In UWA, French J (at [1419] – [1427]) surveyed the case law concerning ideas, discoveries, and inventions. His Honour observed that the notion of the “inventive concept” was recognised in Hickton’s Patent Syndicate v Patents & Machine Improvements Co Ltd (1909) 26 RPC 339, although not referred to by that name. In that case, when discussing Watt’s idea for the condensation of steam in a separate vessel, not in the cylinder itself, Fletcher Moulton LJ said (at 347 – 348):

… That conception occurred to Watt and it was for that that his Patent was granted, and out of that grew the steam engine. Now can it be suggested that it required any invention whatever to carry out that idea when once you had got it? It could be done in a thousand ways and by any competent engineer, but the invention was in the idea, and when he had once got that idea, the carrying out of it was perfectly easy. To say that the conception may be meritorious and may involve invention and may be new and original, and simply because when you have got the idea it is easy to carry it out, that that deprives it of the title of being a new invention according to our patent law, is, I think, an extremely dangerous principle and justified neither by reason, nor authority.

75 It is well established in Australian patent law that an invention may reside in the conception of an idea. In National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252, when discussing an “invention” as “a manner of new manufacture” within the meaning of the Statute of Monopolies, the High Court said (at 264):

The truth is that the distinction between discovery and invention is not precise enough to be other than misleading in this area of discussion. There may indeed be a discovery without invention—either because the discovery is of some piece of abstract information without any suggestion of a practical application of it to be a useful end, or because its application lies outside the realm of “manufacture”. But where a person finds out that a useful result may be produced by doing something which has not been done by that procedure before, his claim for a patent is not validly answered by telling him that although there was ingenuity in his discovery that the materials used in the process would produce the useful result no ingenuity was involved in showing how the discovery, once it had been made, might be applied. The fallacy lies in dividing up the process that he puts forward as his invention. It is the whole process that must be considered; and he need not show more than one inventive step in the advance which he has made beyond the prior limits of the relevant art.

76 Of course, the Full Court in Polwood recognised that the inventive concept, derived from the specification as a whole, may be, or include, the manner in which an idea is carried out: see at [60] – [61]. The point made in Stanelco, and accepted in Polwood, is that a contribution, which is a reduction to practice, is not necessarily part of the inventive concept.

77 Other examples where a person’s claim to entitlement will not be established are where his or her contribution is to do no more than to verify the inventive concept (UWA at [1426]), or to supply data in order for the specification to provide, in United Kingdom parlance, an “enabling disclosure” (IDA at [45] – [47]), or, more generally, to provide “essentially unnecessary detail” (IDA Ltd v University of Southampton [2006] EWCA Civ 145; [2006] RPC 21 (University of Southampton (CA)) at [39]).

78 Implicit in the above discussion is an understanding that a patent specification may disclose more than one inventive concept. As Pumfrey J observed in Collag (at [70]), the approach (i.e., the notion of the inventive concept) is simply stated. The problem is to apply it when there are a number of distinct concepts disclosed by the specification.

79 There is one area in which Australian patent law on the question of entitlement diverges from the United Kingdom patent law. This relates to whether questions of inventiveness, as understood in the context of claim validity, intrude into the identification of the inventive concept, and more particularly into whether particular contributions will be recognised as supporting a claim to entitlement.

80 As we have noted, when questions of entitlement arise, the Court is not concerned with whether the invention, as claimed, satisfies the requirements of a patentable invention. This is the general position in the United Kingdom: Stanelco at [15] and [20]; Collag at [79]. However, there have been developments in the United Kingdom case law which suggest that inventiveness, as it is understood in relation to considerations of claim validity, may have a role in determining questions of entitlement.

81 In Markem, the Court of Appeal directed attention to whether patent validity is relevant to the question of patent entitlement in the context of proceedings under s 8 of the UK Act. This provision confers jurisdiction on the Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks (the Comptroller) to determine contested claims of entitlement before a patent is granted. A broadly similar jurisdiction in respect of Australian patent applications is conferred on the Commissioner of Patents by s 36 of our Act; see also s 33 dealing with claims of entitlement made in the context of opposition proceedings.

82 In dealing with a submission that, under s 8 of the UK Act, the validity of the patent is completely irrelevant, the Court of Appeal held that, where an unanswerable case of invalidity is raised—where “the patent or part of it is clearly and unarguably invalid”—the Comptroller, as a matter of convenience, should take that consideration into account in exercising his or her discretion under the section. As Jacob LJ put it (at [88]):

88 … The sooner an obviously invalid monopoly is removed, the better from the public point of view. But we emphasise that the attack on validity should be clear and unarguable. Only when there is self-evidently no bone should the dogs be prevented from fighting over it.

83 At [90], Jacob LJ continued:

90 … We think that if an inherent part of a claim to entitlement is also an assertion of or acceptance of invalidity, the entitlement claim must fail.

84 While these observations were made in the context of determinations of entitlement under s 8 of the UK Act, they are expressed in terms which suggest a more general application to all proceedings in which entitlement is in issue.

85 In University of Southampton (CA), the Court of Appeal appears to have gone further. The case concerned a method of controlling pests by exposing them to a composition comprising particles containing or consisting of at least one magnetic material. One person claiming to be an inventor, Professor Howse from the University of Southampton, had previously invented an insect trap which used electrostatically charged particles. The trap was described in an article in The Times:

The creatures are lured onto the bridge of the wooden box by a bait. When their feet alight on the electrostatic talcum powder with which it is dusted they slip onto a fly paper and meet their end.

86 The University of Southampton obtained a patent for Professor Howse’s invention using electrostatically charged powder.

87 Mr Metcalfe of IDA, a specialist in magnetic powders, read the article in The Times and realised, from the article’s reference to “electrostatic” powder, that Professor Howse’s invention depended in some way on the “stickiness” of the powder. He knew that electrostatically charged powders were apt to lose their charge over time. He wondered whether magnetic powders would work in the trap.

88 Mr Metcalfe contacted Professor Howse and told Professor Howse about his idea. At the time of this communication, Mr Metcalfe did not actually know how the electrostatically charged particles worked. Professor Howse told Mr Metcalfe that the particles adhered to the legs of the insects, disabling them “so that they slid down the slope to their doom”.

89 Professor Howse followed up Mr Metcalfe’s idea using magnetic powder supplied by IDA. The magnetic powder was trialled by graduate students. Jacob LJ described this work as follows (at [5]):

5 … The work done by the graduate students was no more than simple routine experimentation. It was not work necessary to enable Mr Metcalfe’s idea to be put into practice but work in the nature of mere verification. Any skilled man could have readily done it, given Mr Metcalfe’s idea. It was not suggested the graduate students should be named as inventors.

90 On learning that the magnetic particles work as the electrostatically charged particles had worked, Professor Howse caused the University to apply for a patent. Professor Howse and another (the managing director of a company used by the University to commercialise its inventions) were named as inventors. In a reference under s 8 of the UK Act, the Comptroller held that the true inventors were Mr Metcalfe and another (a consultant to IDA).

91 In the Patents Court, Laddie J held that Mr Metcalfe and Professor Howse (and their respectively named co-inventors) were joint inventors. On appeal, the Court of Appeal restored the Comptroller’s decision.

92 The Court of Appeal’s reasoning was this: the specification in suit (the method using magnetic particles) was essentially the same as the specification of the previous patent (the method using electrostatically charged particles), save that magnetic particles were substituted for electrostatically charged particles. Jacob LJ explained (at [31]):

31 … In 1994 the exposure was “to particles carrying an electrostatic charge”; in the patent in suit the exposure is “to a composition comprising particles containing or consisting of at least one magnetic material”. In short: magnetic particles for electrostatic particles. To my mind, that is the sole key to the information in the patent in suit. That key was provided solely by Mr Metcalfe. Putting it another way, insofar as there is anything inventive in the patent, it was provided only by him.

93 Jacob LJ noted that Mr Metcalfe did not know whether his idea would work or that, if it did work, it would be by adhesion to the legs of the insects. This adhesion meant that the insects could be made to pick up insecticide (what Laddie J called the “sticky poison concept”). At [32] – [33], Jacob LJ said that:

32 … Neither of these matters prevents Mr Metcalfe from being the sole devisor of the invention. For neither of these matters involve the contribution of anything inventive to his idea. So far as finding out whether or not his idea worked that was a matter of simple and routine experimentation—mere verification.

33 So far as the sticky poison concept is concerned that would follow by adding that which any ordinary skilled worker in the field of insect killing would have known. All that Professor Howse added to Mr Metcalfe’s idea is the common general knowledge of those in the art. There was nothing inventive about it and I do not see how Professor Howse could fairly be described as an inventor. The “heart” was Mr Metcalfe’s idea and his alone.

94 At [37], Jacob LJ continued:

37 This case is very unusual in that the invention was not made by a man skilled, or even acquainted with the art. Normally the addition of matter which is common general knowledge is the sort of thing often forming the subject of subsidiary claims of no significance as regards inventorship. Persons skilled in the art naturally add common general knowledge to their key ideas. The fact that here such an addition goes to the generality of the main concept and claim should not, and in my view does not[,] make any difference.

95 These observations can be understood as saying no more than that, once the inventive concept is identified, additions of common general knowledge to the inventive concept will not establish a claim to entitlement. On the other hand, they can also be understood as advancing a different proposition, namely that contributions that are, in fact, matters of common general knowledge cannot form part of the inventive concept.

96 The correctness of Markem was considered in Yeda Research and Development Co Pty Ltd v Rhone-Poulenc Rorer International Holdings Inc [2007] UKHL 43; [2008] RPC 1 (Yeda). This was in respect of a particular principle of the law of entitlement, formulated by the Court of Appeal in Markem, which is not relevant to the present appeal. The House of Lords held that the particular principle formulated by the Court of Appeal was wrong. The House of Lords nevertheless concluded that Markem was correctly decided.

97 When addressing the question of who (under s 7(3) of the UK Act) is “the actual deviser of the invention”, Lord Hoffmann (with whose speech the other Law Lords expressed agreement) said (at [20]):

20 … It is not enough that someone contributed to the claims, because they may include non-patentable integers derived from prior art: see Henry Brothers (Magherafelt) Ltd v Ministry of Defence [1997] R.P.C. 693,706; [1999] R.P.C. 442. As Laddie J. said in the University of Southampton case, the “contribution must be to the formulation of the inventive concept”. Deciding upon inventorship will therefore involve assessing the evidence adduced by the parties as to the nature of the inventive concept and who contributed to it. In some cases this may be quite complex because the inventive concept is a relationship of discontinuity between the claimed invention and the prior art. Inventors themselves will often not know exactly where it lies.

98 In distinguishing the inventive concept from “non-patentable integers derived from prior art”, and in identifying the inventive concept as “a relationship of discontinuity between the claimed invention and the prior art”, Lord Hoffmann appears to have proceeded on the basis that the Court of Appeal in University of Southampton (CA) was expressing a principle that is broader than the limited proposition stated in Markem. Further, Lord Hoffman appears to have accepted that contributions that are matters of common general knowledge cannot form part of the inventive concept, and will not establish a claim of entitlement to the invention.

99 Later, Lord Hoffmann distinguished between the “rules about validity” and the “law of entitlement” and observed (at [29]) that:

29 … in proceedings in which neither side is challenging the validity of the patent, there is no justification for requiring an applicant in a claim to entitlement to plead and prove allegations which are relevant only to the question of validity.

100 Two matters should be noted about this observation. The first is that it involved the rejection of the particular principle formulated by the Court of Appeal with respect to entitlement to which we have referred. It was made in the context of considering the “first to file” rule and thus questions of novelty, not inventiveness. It is possible, therefore, that the “rules of validity” that Lord Hoffmann had in mind were confined to the rules of validity with respect to novelty. The second matter is that Lord Hoffman’s observation appears to suggest that, in entitlement proceedings in which the validity of a patent is challenged, allegations relevant only to the question of validity (including, it would seem, inventiveness) may be relevant to entitlement.

101 Even so, in Welland Medical Limited v Philip Arthur Hadley [2011] EWHC 1994 (Pat), Floyd J (at [20] – [21]) suggested that Lord Hoffman’s statement in Yeda at [20] was directed only to the limited proposition referred to by Jacob LJ in Markem at [88] (quoted above). Floyd J said (at [21]):

21 I do not think that in this passage Lord Hoffmann was saying that one determines entitlement to subject matter in a patent application by reference to any detailed analysis of validity in relation to the prior art. The relevance of validity was addressed in Markem at [87] to [90], and I do not understand the decision in Yeda to undermine the correctness of what was said there. In a nutshell the position arrived at was, per Jacob LJ at [88]: …

102 The role that considerations of inventiveness play in determining questions of entitlement under United Kingdom patent law is not clear. Indeed, it would seem that there is even debate about the precise meaning in law of the expression “inventive concept” and whether its meaning differs in the various contexts in which it has been used in United Kingdom patent law: Kwikbolt Limited v Airbus Operations Limited [2021] EWHC 732 at [94].

103 In the present application, the respondent submits that the reasoning in Markem and University of Southampton (CA) reflects the approach to entitlement that should be adopted in Australia. However, the respondent is not entirely clear as to what this approach is. For example, the respondent does not contend that the present case is one where there is no “bone” to fight over (to use Jacob LJ’s metaphor in Markem). Also, in one part of its submissions, the respondent submitted that Markem and University of Southampton (CA) stand for the principle that “the addition of common general knowledge to an inventive concept does not result in entitlement”. In other parts of its submissions, when dealing with Mr Welch’s contribution, it appears to contend that contributions that are, in fact, common general knowledge, cannot be part of the inventive concept.

104 The present state of Australian law on entitlement is declared in Polwood. Neither party suggested that we should depart from that authority. Polwood adopted, without qualification, Crennan J’s observation in JMVB that rights in an invention are determined by objectively assessing contributions to the invention rather than assessing the inventiveness of respective contributions. That approach conforms to principle. The invention or the inventive concept (in Polwood the Full Court appears to have used these terms synonymously) is discerned from the whole of the specification, not just the claims. However, the requirements of s 18 of the Act, dealing with the characteristics of a patentable invention, including (in the case of a standard patent) the need for an inventive step, are directed specifically to the invention as claimed (i.e., as defined by the claims). The question of entitlement is separate to, and distinct from, the question of patentability assessed by reference to the patent claims. It involves a broader inquiry. It stands to reason, therefore, that consideration of the requirements of patentability under s 18 of the Act, including the existence of an inventive step within the meaning of s 7(2) of the Act, is not part of the entitlement calculus.

SUBMISSIONS on the inventive concept of the 708 application

The applicant’s submissions

105 The applicant submitted that, in J[270] of his reasons, the primary judge erred in his determination of the inventive concept of the 708 application. The applicant identified four errors.

106 First, the applicant contended that the primary judge, in substance, confined the inventive concept of the 708 application to the embodiment claimed in claim 1 of the specification—particularly with respect to the processor integer—and thereby excluded from his consideration of entitlement broader embodiments of the invention that are described in the specification.

107 In this regard, the primary judge identified three factors that characterise the invention: the processor in the VDU detects and determines vehicle overstay (or a notifiable event); the processor initiates a communication with a HHD; and the communication includes data relating to vehicle overstay (or a notifiable event) in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software without additional formatting. These are three features of the VDU claimed in claim 1.

108 But, the applicant submitted, the specification describes alternative embodiments of the invention in which data pertaining to a notifiable event are not communicated to an HHD by the VDU, and the VDU does not format the data so that it is suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software. The applicant submitted that the primary judge erred by not construing the “inventive concept” to encompass all the embodiments described in the specification—being embodiments of the one invention: s 40(4) of the Act.

109 Secondly, the applicant submitted that the primary judge erred by not finding that the inventive concept of the 708 application includes, at least in part, the idea of an integrated sensor system in which the infringement details are pre-populated into the infringement issuing software, saving the parking officer from undertaking “manual entry”. The applicant submitted that the sensor system described in the specification is agnostic as to which component performs the formatting work, so long as the infringement details (or notifiable event) are pre-populated into the infringement issuing software.

110 Thirdly, the applicant submitted that the primary judge erred by not finding that the inventive concept also included, at least in part, an integrated sensor system in which the sensor is a magnetic sensor that is able to output a signal caused by the occupancy by a vehicle of a vehicle space.

111 Fourthly, and relatedly, the applicant submitted that the primary judge erred by analysing the inventive concept of the 708 application from the perspective of the manual entry problem. The applicant submitted that this is the wrong starting point; the specification does not even refer to a manual entry problem. The applicant submitted that, by commencing his analysis from the perspective of the manual entry problem, the primary judge, in error, excluded the use of a magnetic sensor as part of the inventive concept.

112 The applicant referred to a number of examples where, it said, the specification describes alternative embodiments of the invention in which the data pertaining to a notifiable event is not communicated by the VDU to the supervisory device, and the VDU does not perform the formatting work.

113 The first example is the description, at page 10, lines 11 – 19 of the specification, of the infringement issuing software being run in the supervisory device, which is a HHD:

When the IIS [Infringement Issuing Software] is being run on the HHD [Hand Held Device] 134, the HHD 134 is responsible for receiving and processing of data from the TMT [Transient Middle Tier] 132, including the storage of Parking Event data and System Health data for each VDU [Vehicle Detection Unit] 110. When infringement details are acquired, the location of the associated VDU 110 and any other details required for the IIS to produce the infringement notice will be retrieved from an internal memory of the HHD 134 based on the details provided by the VDU 110. For example, the details of the internal memory may include a street-to-suburb mapping to enable the HHD 134 to include the suburb in the infringement notice. When an infringement has been issued the HHD 134 passes a message via the TMT 132 to the VDU 110 to reset the VDA [Vehicle Detection Algorithm] so that a new monitoring period can commence.

114 This passage is part of the detailed description of the invention that is given with reference to Figure 1. As we have noted, Figure 1 illustrates a network topology comprising a TMT in accordance with a preferred embodiment of the invention:

115 The applicant contended that the quoted passage discloses an arrangement in which the HHD (rather than the VDU) is responsible for processing the infringement data into a format that is suitable for pre-population into the data fields in the infringement issuing software. The applicant contended that, in this arrangement, the HHD pre-populates the infringement issuing software with details it obtains from its own internal memory. It further contended that, in order for this to be done, the HHD formats the infringement data in a format that allows for pre-population into the data fields in the infringement issuing software.

116 We do not accept the applicant’s interpretation of this part of the specification insofar as it suggests that, in this embodiment of the invention, the VDU does not communicate data of notifiable events in a format suitable for pre-population in the infringement issuing software. The passage on which the applicant relied must be read in the broader context of the description of the preferred embodiment given at page 8, line 14 to page 10, line 9 of the specification.

117 This broader context makes clear that the VDU determines when a vehicle moves into violation of parking restrictions. Upon determination of an actual or impending infringement, communications are initiated from the VDU to the TMT. The TMT acts as a conduit. It passes data between the HHD and each VDU.

118 In this embodiment, the TMT is provided by wireless networking hardware positioned in the holster of the HHD. The communications between the TMT and the HHD occur via a mini USB port. The HHD and the TMT thus have a permanent connection in place, whereby communication can occur at any time. The TMT is “transient” because it travels in the field with the parking officer. It is not always available for communications with any given VDU.

119 The specification teaches that each VDU has memory storage enabling the VDU “to upload data for pre-population into the HHD ... as required”. The data includes infringement data and offence details.

120 It is implicit in the enablement of the VDU “to upload data for pre-population into the HHD ... as required” that the data is communicated to the HHD in a format suitable for pre-population into the infringement issuing software.

121 When the infringement issuing software is run in the HHD, the HHD is responsible for receiving and “processing” data from the TMT. However, when, in this part of the description, the specification refers to the HHD “processing” data from the TMT, it is not talking about formatting all data items pertaining to a notifiable event. This is because the detailed description also teaches that the VDU has already uploaded data items pertaining to the notifiable event for pre-population into the infringement issuing software.

122 The applicant’s reliance on this example appears to proceed from a misreading of claim 1. At J[63], the primary judge found that there is nothing in the text of claim 1 that requires all data items pertaining to the notifiable event to be communicated by the VDU in a format suitable for pre-population into the infringement issuing software. Further, the primary judge found that there is no technical reason why all data items need to be communicated in this way. The communications could be just a sensor node ID and the duration of the vehicle in the parking bay. Other required information could be obtained from a database in the supervisory device itself.

123 Further, at J[70], the primary judge also found that, although the data pertaining to a notifiable event communicated by the VDU to the supervisory device must be in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software, this does not mean that the supervisory device does not carry out necessary processing of data packets sent by the VDU, such as the removal of headers, that must always be done at the receiver end to return the data to its original form.

124 We do not accept, therefore, that the first example given by the applicant is the description of an alternative embodiment of the invention in which data pertaining to a notifiable event is not communicated by the VDU to the supervisory device, or in which the VDU does not perform formatting work.

125 Another example proffered by the applicant is the specification’s description of the generalised network topology illustrated by Figure 5:

126 In this embodiment, a backend system provides for the configuration, processing, and storing of data. It also provides for the processing of all PINs, and stores all signage information to determine if a vehicle has “committed an offence”.

127 The HHD is carried by a parking officer and receives communications regarding infringements, or pending infringements, from the backend system, from a middle tier separate from the HHD, or from the VDUs. The HHD is provided with pre-populated details, which are automatically passed into the PINs for processing by the officer.

128 We accept that the specification’s description of this embodiment contemplates a topology (among other possible topologies) in which, for example, communications regarding the details of an infringement or pending infringement (notifiable events), including “prepopulated details”, are from the backend system (which determines whether a vehicle has “committed an offence”) to the HHD, not from the VDU to the HHD.

129 A further example proffered by the applicant is the specification’s description of a “smart middle tier”, with reference to Figure 8:

130 In this embodiment, the “smart middle tier”, as opposed to a “dumb middle tier” (which simply functions as a router), provides the sophisticated functionality of the backend system and is responsible for determining if a vehicle in a parking bay is in violation of a parking requirement. If it is, the “smart middle tier” passes the information to a HHD for issuing a PIN. The “smart middle tier” is mobile and may be carried by a parking officer in a HHD.

131 We accept that the specification’s description of this embodiment contemplates a topology (among other possible topologies) in which communications regarding infringements or possible infringements are from the smart middle tier (which determines parking violations) to the HHD, not from the VDU to the HHD.

132 When regard is had to the descriptions provided with respect to Figures 5 and 8, it is apparent that the invention is not confined to devices, systems, or methods in which the VDU determines notifiable events. When notifiable events are determined by components other than the VDU, such as a backend system or smart middle tier, it is implicit that any communications that the VDU has with other components are not communications that include data items pertaining to notifiable events, let alone such data items communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software.

The respondent’s submissions

133 The respondent supported the primary judge’s finding as to the inventive concept of the 708 application. It submitted that the primary judge was correct to consider the claims in determining the inventive concept, and that the inventive concept lay not in the concept of an integrated sensor system, but in reducing that concept into practice, which required inventive ingenuity. This, the respondent argued, was reflected in the claims.

134 The respondent also supported the primary judge’s approach of viewing the inventive concept from the perspective of a solution to the manual entry problem which, the respondent submitted, involved arriving at a wireless system that balances the power saving considerations involved in communications between remote devices that are not connected to mains power. In this regard, the respondent maintained that the inventive concept included the requirements of claim 1 that the processor in the VDU should initiate communications with the HHD and that the VDU itself should send infringement information in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software.

135 The respondent submitted that the (broader) inventive concept identified by the applicant closely resembles that which was found by the primary judge to have been obvious at the priority date. Based on the observations made in University of Southampton (CA), the respondent submitted that information which does not incorporate inventive ingenuity, and which has been disclosed publicly, without fetter of confidentiality, cannot found a claim to entitlement. It submitted that “the contribution of common general knowledge does not give rise to entitlement”.

Analysis

136 The primary judge saw the invention as the reduction of a concept to a working apparatus. The concept found expression in the Welch proposal ([41] above), which was Mr Welch’s solution to the manual entry problem ([38] above). However, the specification does not identify a manual entry problem as such; nor is the invention, as described, directed to providing a solution to a manual entry problem.

137 The invention, as the respondent chose to describe it, relates to the “automated determination of notifiable parking events”: page 1, lines 10 – 11. It provides devices, methods, and systems which are said to provide advantages over the prior art method of enforcing vehicular parking regulations. According to the specification, the prior art method typically involved a parking inspector manually inspecting all of the restricted spaces periodically, regardless of whether vehicles were actually present. The specification points to the deficiencies of manual enforcement: it is costly; time-consuming; and inefficient, in that the parking inspector may fail to detect a parking violation, leading to a lack of deterrence and the denial of infringement revenue to the parking agency. The specification also points to the asserted fact that manual enforcement is unable to provide historical data of parking usage. No mention is made of a manual entry problem.

138 Thus, the specification seats the invention as an automated parking enforcement system that provides advantages over a so-called manual parking enforcement system.

139 Later, the specification discloses that, in further preferred embodiments of the invention: