Federal Court of Australia

Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd v Lloyd [2021] FCAFC 187

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | Cross-Appellant | |

AND: | BELCONNEN LAKEVIEW PTY LTD (and others named in the Schedule) First Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal brought by the appellant (Belconnen) be allowed.

2. The cross-appeal brought by the respondent (Mrs Lloyd) be dismissed.

3. The cross-cross-appeal brought by the second cross-respondent (Mr Hindmarsh) and the third cross-respondent (Mr Ryan) be allowed.

4. The following parts of the orders of the primary judge dated 14 May 2020 be set aside:

(a) paragraph 1;

(b) paragraph 4; and

(c) the reference to order 4 in paragraph 6.

5. In lieu thereof, it be ordered that Mrs Lloyd’s claim against Belconnen be dismissed.

6. In relation to any consequential orders arising from the above, the costs of the proceeding at first instance, and the costs of the appeal, the cross-appeal and the cross-cross-appeal:

(a) Within 14 days:

(i) Belconnen file and serve written submissions (of no more than five pages), proposed minutes of orders and any affidavit material; and

(ii) Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan file and serve written submissions (of no more than two pages), proposed minutes of orders and any affidavit material;

(b) Within a further 14 days, Mrs Lloyd file and serve written submissions (of no more than seven pages), proposed minutes of orders and any affidavit material; and

(c) Subject to further order, the issues of consequential orders and costs be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The appellant, Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd (as trustee of the Belconnen Lakeview Unit Trust) (Belconnen) was the developer and vendor of the “Altitude Apartments” located on land in the suburb of Belconnen in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT).

2 In the relevant proceeding at first instance, which was a representative proceeding under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), the present respondent (the applicant at first instance) (Mrs Lloyd), on her own behalf and on behalf of group members, sued Belconnen and two of its officers, Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan (who are, respectively, the second and third cross-respondents before this Court).

3 The transaction in issue was a sale of the unexpired term of a lease with respect to a residential unit from Belconnen to Mrs Lloyd for $554,900, inclusive of Goods and Services Tax (GST). The draft contract of sale was prepared by Belconnen on the basis that the sale was a taxable supply for GST purposes and that the vendor would apply the “margin scheme” (described later in these reasons). The parties entered into the contract in this form.

4 Approximately one month later, settlement took place. Mrs Lloyd paid the purchase price and the unexpired term of the lease was transferred to her.

5 Despite the form of the draft contract (and the contract as entered into by the parties), in truth the sale was not a taxable supply. That is, no GST applied to the sale (and the margin scheme could not be applied). Indeed, some two years before the date of the contract with Mrs Lloyd, Belconnen had obtained a private binding ruling from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) that sales of unexpired terms of leases with respect to residential units in the development were not taxable supplies. The draft contract was prepared on an incorrect basis.

6 Subsequently, Mrs Lloyd commenced the proceeding at first instance, relying on several causes of action. The following two causes of action are of particular relevance for present purposes.

(a) First, Mrs Lloyd contended that Belconnen had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Australian Consumer Law) and that Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan were knowingly involved in the contravention.

(b) Secondly, Mrs Lloyd sought recovery of money on the basis of an action for money had and received (the restitution case). By this claim she sought the recovery of approximately $46,000, being the GST that would have applied to the sale of the unit had the supply been a taxable supply and subject to the margin scheme.

Another pleaded cause of action was breach of contract, but Mrs Lloyd abandoned this case after the close of evidence and before submissions during the trial.

7 The primary judge, in his principal reasons for judgment, Lloyd v Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 2177 (the Reasons):

(a) upheld Mrs Lloyd’s misleading or deceptive conduct case against Belconnen, finding that the conduct of Belconnen in proffering the draft contract conveyed a misleading representation, that the representation continued to be made between the date of the contract and the date of settlement, and that the misleading conduct was causative of loss, in that Mrs Lloyd lost an opportunity to renegotiate the contract; the primary judge awarded Mrs Lloyd compensation of approximately $23,000 for the loss of this opportunity;

(b) rejected Mrs Lloyd’s case against Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan; and

(c) rejected Mrs Lloyd’s restitution case.

8 Belconnen has filed a notice of appeal and Mrs Lloyd has filed a notice of cross-appeal. Further, Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan have filed a notice of cross-cross-appeal, which relates only to costs and is contingent on the appeal being allowed and the cross-appeal being dismissed.

9 The following documents have also been filed by the parties:

(a) Mrs Lloyd has filed a notice of contention in the appeal;

(b) Belconnen, Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan have filed a notice of cross-contention in the cross-appeal; and

(c) Belconnen has filed an interlocutory application dated 21 April 2021 seeking that the Court receive further evidence on the appeal.

10 The issues raised by the notices and other documents referred to above can be summarised as follows (and it is convenient to deal with the issues in the following order):

(a) Whether the primary judge erred in finding that Belconnen had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, that the conduct was causative of loss, or in the assessment of any loss or damage (appeal grounds 1 to 6; Mrs Lloyd’s notice of contention, grounds 1 and 2); and whether Belconnen should be permitted to adduce further evidence on appeal (the First Issue).

(b) Whether the primary judge erred in failing to find that Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan were knowingly involved in any contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law by Belconnen (cross-appeal, grounds 8 to 11; notice of cross-contention, ground 2) (the Second Issue).

(c) Whether the primary judge erred in rejecting Mrs Lloyd’s restitution case (cross-appeal, grounds 1 to 7; notice of cross-contention, ground 1) (the Third Issue).

(d) Whether the primary judge erred in relation to the answers to certain common questions of law and fact and in dismissing an interlocutory application by Belconnen to declass the proceeding (appeal grounds 7 to 9) (the Fourth Issue).

(e) In the event that the appeal is allowed and the cross-appeal is dismissed, whether the primary judge erred in relation to costs (cross-cross-appeal, ground 1) (the Fifth Issue).

11 For the reasons that follow, we have concluded, in summary, as follows:

(a) In relation to the First Issue:

(i) Insofar as Belconnen challenges the primary judge’s finding that any misleading or deceptive conduct caused loss or damage to Mrs Lloyd, we uphold this contention. We consider that the primary judge erred in concluding that Mrs Lloyd lost an opportunity of non-negligible value (namely the opportunity to renegotiate the contract). In our view, the primary judge should have held that Mrs Lloyd did not lose an opportunity of non-negligible value. It follows that Belconnen’s appeal is to be allowed.

(ii) Insofar as Belconnen contends that the primary judge erred in holding that the draft contract was misleading or deceptive, and that the relevant representation was a continuing representation, we reject those contentions.

(iii) In light of these conclusions, it is unnecessary to determine Belconnen’s application to receive further evidence on appeal. Had it been necessary to deal with this, we would have rejected it.

(b) In relation to the Second Issue, no error is established in the primary judge’s conclusion that Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan were not knowingly involved in any contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law by Belconnen.

(c) In relation to the Third Issue, the primary judge was correct to conclude that Mrs Lloyd’s restitution case failed. However, our reasons for reaching this conclusion are different from those of the primary judge.

(d) In relation to the Fourth Issue, we do not accept Belconnen’s contentions that the primary judge erred.

(e) In relation to the Fifth Issue, given the conclusions we have reached, the relevant costs order made by the primary judge needs to be set aside and re-visited.

The proceeding at first instance

12 There were two proceedings at first instance, but only one of those proceedings is relevant for present purposes. The two proceedings before the primary judge were:

(a) proceeding NSD 1417 of 2017 (the Altitude proceeding); and

(b) proceeding NSD 1555 of 2018 (the Governor Place proceeding).

13 The relevant proceeding for present purposes is the Altitude proceeding. However, it will be necessary to refer to some parts of the primary judge’s reasoning in relation to the Governor Place proceeding, to provide context and background for his Honour’s reasoning in relation to the Altitude proceeding. In that regard, it is convenient to note that the developers relevant to the Governor Place proceeding were referred to in the Reasons as the Barton Developers, and the specific cases that were tried as part of that proceeding related to Mr and Mrs El-Zein and Mr and Mrs Eppelstun.

14 Mrs Lloyd brought the Altitude proceeding as a representative proceeding on her own behalf and on behalf of other persons (Altitude group members) who purchased the unexpired term of a lease for a residential unit in the development known as “Altitude Apartments” from Belconnen pursuant to a contract (Altitude Contract) that contained the terms pleaded in paragraphs 17-18 of the second further amended statement of claim filed 3 May 2019 (the statement of claim).

15 Mrs Lloyd pleaded a number of different causes of action, including money had and received, breach of contract, misleading or deceptive conduct and unconscionable conduct (contrary to statutory provisions). She also brought claims for accessorial liability against Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan on the basis that they were knowingly involved in the statutory contraventions.

16 On 30 April 2019, an order was made in the Altitude proceeding that the following matters would be determined at an initial trial: the whole of the claim of Mrs Lloyd; and various agreed common issues of law or fact set out in Schedule 1 to those orders. The issues of law and fact are set out in [20] of the Reasons.

The GST context

17 Before setting out the background facts, we refer to some relevant aspects of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (the GST Act).

18 Under s 7-1(1) of the GST Act, GST is payable on (relevantly) taxable supplies. An entitlement to claim input tax credits arises on (relevantly) creditable acquisitions: GST Act, s 7-1(2). Liability to pay the GST on a taxable supply falls on the person making the supply: GST Act, s 9-40. Generally, the amount of GST on a taxable supply is 10% of the value of the taxable supply: GST Act, s 9-70.

19 Section 9-5, which provides a definition of “taxable supply”, provides that a supply is not a taxable supply to the extent that it is GST-free or input taxed. GST-free supplies can be put to one side for present purposes. Section 9-30(2) provides that a supply is input taxed if (relevantly) it is input taxed under Div 40 or under a provision of another Act. Under the GST Act, if a supply is input taxed, no GST is payable on the supply, and there is no entitlement to an input tax credit for anything acquired or imported to make the supply: see s 40-1.

20 Division 75 of the GST Act contains special rules relating to the sale or grant of certain interests in real property, including (relevantly) long-term leases. The Division allows the taxpayer to use a “margin scheme” in relation to the supply of such interests. If a taxable supply of an interest in real property is under the margin scheme, the amount of GST on the supply is 1/11 of the margin for the supply: GST Act, s 75-10(1). Broadly, the margin for the supply is the amount by which the consideration for the supply exceeds the consideration for the taxpayer’s acquisition of the interest in land: GST Act, s 75-10(2).

21 In order for the margin scheme to apply, it is necessary for the person selling or granting the interest and the recipient of the supply to agree in writing that the margin scheme is to apply: GST Act, s 75-5(1). The taxpayer is not required to issue a tax invoice for a taxable supply that it makes that is solely a supply of real property under the margin scheme: s 75-30(1).

22 An acquisition of certain interests in real property, including a long-term lease, is not a creditable acquisition if the supply of the interest was a taxable supply under the margin scheme: GST Act, s 75-20. Thus, one effect of the margin scheme is that the purchaser of a long-term lease cannot claim an input tax credit for the GST paid on the purchase price. For a private residential purchaser, who cannot claim input tax credits in any event, this is of little concern. For a commercial purchaser, who would otherwise be able to claim an input tax credit in respect of the acquisition, it might prefer to forgo the input tax credit so as to benefit from the margin scheme when on-selling the property. However, the commercial purchaser can only use the margin scheme when on-selling the property if it had earlier acquired the property under the margin scheme: see GST Act, ss 75-5(2) and 75-5(3)(a). As Robb J explained in Prowl Pty Ltd v DL Brookvale Pty Ltd [2018] NSWSC 1255 (at [22]-[23]) in the context of a development:

22 … The benefit that the purchaser gains from the application of the margin scheme is that it is entitled to apply the margin scheme at the time the property is on-sold, or individual units following the development of the property are sold. The GST payable by the purchaser (now as vendor) will be calculated as a proportion of the difference between the sale price and the original purchase price. The GST payable will invariably be less than if the ordinary basis had applied. …

23 It will be a matter for commercial judgment for a developer … concerning the balance between being able to recover the GST as an input tax credit if the purchase takes place on the ordinary basis, and possibly having to sell the developed units with a higher component of GST payable, on the one hand, and absorbing the GST on the other if the margin scheme is applied, but being able to deal with a lesser amount of GST on the sale of the units after the development has been completed.

23 The interest of a commercial purchaser in being able to use the margin scheme for a future sale would seem to be the purpose of the warranty by the seller in cl 24.5 of the contract of sale in issue in the present case (discussed later in these reasons).

Background facts

24 The following statement of the background facts is largely based on the findings of the primary judge as set out in the Reasons.

Overview

25 Before setting out the facts in detail, it is useful to identify five key dates in the chronology of relevant events:

(a) On 8 February 2013, Belconnen applied to the ATO for a private binding ruling.

(b) On 12 March 2013, Belconnen received a private binding ruling from the ATO (the Altitude Private Ruling).

(c) In March and April 2013, Belconnen amended its GST returns and repaid input tax credits consistently with the Altitude Private Ruling.

(d) On 10 March 2015, Mrs Lloyd and Belconnen exchanged contracts with respect to her purchase of the unexpired term of a lease of a residential unit in the Altitude Apartments development (the Lloyd Contract).

(e) On 7 April 2015, settlement of the purchase took place.

The period before February 2013

26 In 2007, Belconnen purchased the unexpired term of a Crown lease for the relevant land in the suburb of Belconnen, ACT.

27 In or around August 2008, Belconnen retained Clayton Utz to prepare a master contract for the Altitude Apartments development and to act on any sales. A partner of Clayton Utz was appointed by power of attorney to sign contracts on Belconnen’s behalf.

28 Mr Hindmarsh is and was at the material times the sole director and 50% shareholder of Belconnen. He was the Executive Chairman of the Hindmarsh Group, of which Belconnen formed part. At the material times, Mr Ryan was the company secretary of Belconnen and the CFO of the Hindmarsh Group.

29 In 2009, Belconnen was granted development approval in relation to the development of the Altitude Apartments.

30 From about 2010, Belconnen offered to enter into, and entered into, contracts to sell the unexpired term of the then unregistered leases for the residential units in the development.

31 In May 2010, the Full Court of this Court gave judgment in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Gloxinia Investments Ltd (2010) 183 FCR 420 (Gloxinia). In the context of a developer selling strata lot leases with respect to residential premises, the Full Court (by a majority) held that the supply was an “input taxed supply” rather than a taxable supply for the purposes of the GST Act. In circumstances where the Full Court’s holding departed from the then prevailing understanding of the ATO, legislation was passed (the Tax Laws Amendment (2011 Measures No. 9) Act 2012 (Cth)), with the effect that, subject to transitional provisions (or exceptions), sales of newly constructed residential premises that were the subject of a development lease arrangement would be taxable supplies. The transitional arrangements (or exceptions) are of significance for present purposes. As discussed below, Belconnen obtained a private binding ruling that an exception applied to supplies of the unexpired term of leases of residential units in the Altitude Apartments development, with the effect that the relevant supplies were input taxed supplies.

32 In mid-2011, the building of the Altitude Apartments commenced.

33 On 16 May 2012, Mr Ryan met with Mr Mile Petrevski and Mr Warwick Burr of Maxim Chartered Accountants (Maxim). During that meeting, Mr Ryan provided Messrs Petrevski and Burr with some information about the Hindmarsh Group’s ongoing developments and they discussed Gloxinia. Subsequently, there was an exchange of information and further meetings.

34 On 20 December 2012, Mr Petrevski sent Mr Ryan a letter confirming the terms of engagement between Belconnen and Maxim, and on 23 January 2013, Mr Ryan sent an email to Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Darren Dougan (the then CEO of the Hindmarsh Group) that attached the Maxim engagement letter and provided a useful recounting of the background to the engagement:

As discussed last week, I have agreed to a proposal from Maxim Chartered Accountants to provide consultancy services to Hindmarsh to prepare a request for a Private Binding Ruling (PBR) to be lodged with the ATO during January, regarding the treatment of GST that Hindmarsh should follow for GST relating to the settlements at Altitude…

To summarise, Maxim approached me before Christmas advising that they had recently been successful with PBRs for 2 development clients where there were very specific circumstances that applied, and offered to review the facts around any Hindmarsh projects that were similar. On the basis of high level information I provided on the Altitude project, they assessed it as a close fit with the circumstances and timing in which amendments to the GST law during 2011 and 2012 allowed for certain sales of new residential apartments to be input-taxed.

By treating sales as input-taxed, Hindmarsh would not have to remit GST on the sale prices received for the apartments, but would have to refund any GST input credits previously received by Hindmarsh from expenditure on the project. This would increase the Altitude profit by approximately $3m (GST on sales of $13m less $10m in credits refunded)…

The timing of lodgement of the PBR is crucial, so that we are in a position to decide whether to go ahead with this treatment before we have to remit the GST on the first settlements to occur at Altitude…

I am confident that this is a low risk proposal for Hindmarsh, on the basis of the fee arrangement and Maxim’s reputation and experience in these matters…

I will advise you when the PBR is ready for lodgement.

The period from February to April 2013

35 In February 2013, the plan for the residential units was registered. Upon registration, the Crown lease ended and Belconnen became the holder of an estate in leasehold in each of the residential unit leases, and Belconnen was entitled to sell the unexpired term of each of the residential unit leases.

36 On 4 February 2013, Mr Burr sent Mr Ryan an email attaching a copy of the draft private ruling request for Belconnen. In this email, Mr Burr asked Mr Ryan to review the contents, confirm that the facts and circumstances were accurate and sign the declaration to go with the private ruling request. The private ruling request was later lodged on behalf of Belconnen with the ATO on 8 February 2013, before any settlements occurred.

37 From 8 February 2013, contracts for the unexpired term of leases with respect to residential units in the Altitude Apartments development started to be settled.

38 Mr Ryan became concerned about the delay in obtaining the private ruling. On 18 February 2013, he sent an email to Mr Burr requesting an update on whether any feedback had been received from the ATO and stating:

For information, as at COB today there have been 44 settlements in Stage 1 (Chandler St) for a gross proceeds of $18,485,075 and a GST value under the margin scheme of $1,706,073.

39 Prior to the Altitude Private Ruling, Belconnen was treating the sale of the unexpired term of a lease with respect to a residential unit in the Altitude Apartments development as a taxable supply and intended to apply the margin scheme.

40 On 12 March 2013, the Altitude Private Ruling was issued and the following day, Mr Burr sent Ms Margaret O’Shea (Financial Controller at the Hindmarsh Group) an email, copied to Mr Ryan, stating: “[as] discussed with Gerry this morning, the ATO have confirmed that sales of residential apartments at Altitude are eligible to be treated as input taxed” and thereafter provided Ms O’Shea some instructions with respect to preparing the February 2013 and later Business Activity Statements on an input taxed basis, amending prior Business Activity Statements upon which Belconnen had claimed input tax credits, and repaying all relevant input tax credits previously claimed.

41 The February 2013 Business Activity Statement was prepared on the basis that all of the sales that had occurred during this month were input taxed supplies, not taxable supplies. An email sent by Ms O’Shea to Mr Burr on 20 March 2013 attached a GST calculation worksheet showing that the sales throughout February 2013 amounting to $25,703,393 were treated as input taxed. Also, in or about March 2013, Belconnen filed amended GST returns and on or about 21 March 2013, Belconnen repaid $2,086,245 (being some of the input tax credits).

42 On 30 April 2013, Maxim issued an invoice to the Hindmarsh Corporate Unit Trust for $712,250, being an amount it calculated as 15% of the benefit obtained by Belconnen from treating the sales as input taxed, plus GST. An email from Mr Burr to Mr Ryan had noted that “I have made the invoice out to Belconnen Lakeview (per our engagement letter) … I note that as Belconnen Lakeview is treating is [sic] sales input taxed, it is unlikely to be able to claim the GST on our fee. Please advise if you would like us to invoice an alternate Hindmarsh entity”. Mr Ryan responded, reflecting the distinct benefit received by Belconnen, by noting he was happy with the fee calculation as it “appropriately reflect[s] the benefit coming to Hindmarsh from the change of GST status to input taxed”.

Mrs Lloyd

43 Mrs Lloyd is a widow in her 60s. Following the death of her husband and her retirement in 2014, she decided to move to Canberra and looked at various properties in Canberra, including a two-bedroom apartment in the Altitude Apartments development.

The Lloyd Contract (10 March 2015)

44 As noted above, on 10 March 2015 the Lloyd Contract was entered into by exchange of contracts. In the proceeding at first instance, the Lloyd Contract was treated as representative of the Altitude Contracts.

45 The Lloyd Contract was adapted from a standard form, namely the Law Society of the ACT Contract for Sale form (2013 edition). The contract comprised:

(a) standard printed terms (the Printed Terms), commencing with a two-page Schedule to be populated (the Schedule); and

(b) special conditions drafted by the solicitors for Belconnen (the Special Conditions).

The Special Conditions had paramountcy over the Printed Terms: see cl 59 of the Special Conditions.

46 It is common ground that the Printed Terms were drafted so as to be applicable to all conveyances of land in the ACT, which, like conveyances of land elsewhere in Australia, is a type of property transfer closely regulated by statute. Accordingly, the Printed Terms may or may not be applicable depending upon the particular circumstances of the conveyance. Similarly, the Schedule includes space for including individual details which may or may not be relevant depending upon the circumstances.

47 Notwithstanding that “supply” is defined very broadly in s 9-10(1) of the GST Act, and includes “a grant, assignment or surrender of real property”, there is no “supply” within the meaning of the GST Act upon exchange of contracts for the sale of land. It is therefore conceivable that after exchange, and prior to settlement (which in the case of “off the plan” sales could be a very considerable period), the characterisation of the anticipated supply could change from a taxable supply to a supply which is not taxable or vice versa: see the Reasons, [38].

48 In the case of the Lloyd Contract, the Schedule set out, on page one, the conventional particulars of the conveyance including the following matters (which were defined terms in the contract): the Land, the Seller, the Seller Solicitor, the Stakeholder, the Seller Agent, the Goods (that is, inclusions), the Date for Completion, the Buyer, the Buyer Solicitor and the Date of this Contract. Importantly, the Price was specified as follows:

$554,900.00 (GST inclusive unless otherwise specified).

As can be seen, the Price was specified as being GST inclusive “unless otherwise specified”. No provision of the contract “otherwise specified”.

49 After referring to any details of co-ownership, page one also provided space for execution. The copy of the Lloyd Contract in the Appeal Book has been executed by the Seller.

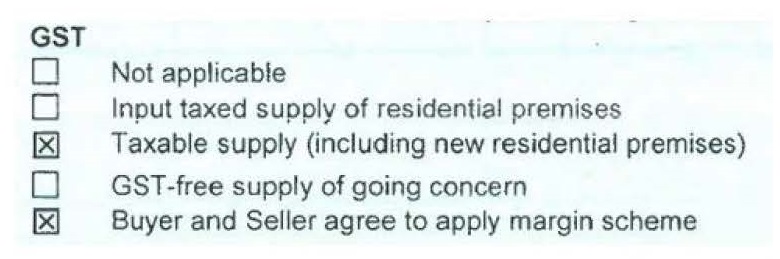

50 The second page of the Schedule identified documents included in, and forming part of the contract, and then identified further particulars, including the following boxes relating to GST:

51 It is common ground that, to reflect the correct tax treatment of the supply, the two boxes that were crossed should not have been crossed; rather, the box alongside the words “Input taxed supply of residential premises” should have been crossed.

52 The Printed Terms included a clause (cl 24) relating to GST. That clause was in the following terms:

24 GST

24.1 If a party must pay the Price or provide any other consideration to another party under this Contract, GST is not to be added to the Price or amount, unless this Contract provides otherwise.

24.2 If the Price is stated in the Schedule to exclude GST and the sale of the Property is a taxable supply, the Buyer must pay to the Seller on Completion an amount equal to the GST payable by the Seller in relation to the supply.

24.3 If under this Contract a party (Relevant Party) must make an adjustment, pay an amount to another party (excluding the Price but including the Deposit if it is released or forfeited to the Seller) or pay an amount payable by or to a third party:

24.3.1 the Relevant Party must adjust or pay at that time any GST added to or included in the amount; but

24.3.2 if this Contract says this sale is a taxable supply, and payment would entitle the Relevant Party to claim an input tax credit, the adjustment or payment is to be worked out by deducting any input tax credit to which the party receiving the adjustment or payment is or was entitled multiplied by the GST Rate.

24.4 If this Contract says this sale is the supply of a going concern:

24.4.1 the parties agree the supply of the Property is the supply of a going concern;

24.4.2 the Seller must on Completion supply to the Buyer all of the things that are necessary for the continued operation of the enterprise;

24.4.3 the Seller must carry on the enterprise until Completion;

24.4.4 The Buyer warrants to the Seller that on Completion the Buyer will be registered or required to be registered;

24.4.5 If for any reason (and despite cl. 24.1 and 24.4.1) the sale of the Property is not the supply of a going concern but is a taxable supply:

(a) the Buyer must pay to the Seller on demand the amount of any GST payable by the Seller in respect of the sale of the Property; and

(b) the Buyer indemnifies the Seller against any loss or expense incurred by the Seller in respect of that GST and any breach of cl 24.4.5(a).

24.5 If this Contract says that the Buyer and Seller agree that the margin scheme applies to the supply of the Property, the Seller warrants that it can use the margin scheme and promises that it will.

24.6 If this Contract says the sale is a taxable supply, does not say the margin scheme applies to the sale of the Property, and the sale is in fact not a taxable supply, then the Seller must pay the Buyer on Completion an amount of one-eleventh of the Price.

24.7 On Completion the Seller must give the Buyer a tax invoice for any taxable supply by the Seller by or under this Contract.

53 Turning to the Special Conditions, three clauses have relevance. They are clauses 52, 56 and 60, which were in the following terms:

52. Price inclusive of GST

(a) The Price payable in accordance with this Contract is inclusive of GST (within the meaning of the A New Tax System (Goods & Services Tax) Act 1999 (sic) as amended from time to time.)

(b) The Buyer agrees with the Seller that any GST the Seller is liable to pay on the supply of the Unit to the Buyer under this Contract is calculated under Division 75 of the A New Tax System (Goods & Services Tax) Act 1999 (sic) (ie. the Margin Scheme).

…

56. Representations

56.1 Entire agreement

The Buyer agrees that this Contract sets out the entire agreement of the parties on the subject matter of this Contract and supersedes any prior agreement, advice, material supplied to the Buyer or understanding on anything connected with the subject matter of this Contract.

56.2 No reliance

Each party has entered into this Contract without reliance upon any representation, statement or warranty (including sales and marketing material and preliminary art work), except as set out in this Contract.

…

60. Definitions

60.1 Definitions

In these Special Conditions the following words have the following meanings:

“Contract” means this contract for sale including the Printed Terms and these Special Conditions and any annexure or schedules to it.

…

“Printed Terms” means the printed terms of the standard ACT Law Society Contract 2013 Edition.

60.2 Same meanings

For the avoidance of any doubt, unless otherwise stated, the terms that are defined in the Printed Terms of the Contract have the same meanings in these Special Conditions.

54 Clause 52 serves to reinforce the fact that the Lloyd Contract was GST inclusive and that the Special Conditions did not otherwise specify (as referred to in the definition of the Price). Additionally, cl 52(b) contemplated that Belconnen may not be liable for GST on the supply (“any GST the Seller is liable to pay on the supply …”) and that only Belconnen could have a liability for GST, if applicable on settlement, as Belconnen, as Seller, was the entity making the supply.

Settlement of the Lloyd Contract (7 April 2015)

55 On 7 April 2015, settlement of the Lloyd Contract took place.

56 The sale by Belconnen to Mrs Lloyd was an input taxed supply.

57 Significantly, there was no evidence at trial that Mrs Lloyd’s residential unit was worth anything less than the amount she paid at the time of purchase: Reasons, [336].

Other facts and evidence relating to the Lloyd Contract

58 As stated in the Reasons at [316], there was no dispute at trial (nor is there any dispute now) that at all material times prior to the completion of the Lloyd Contract, Belconnen did not disclose to Mrs Lloyd that Belconnen: (a) had obtained the Altitude Private Ruling; and (b) GST was not payable in respect of the sale of the unexpired term of the lease with respect to the relevant residential unit. This was despite the fact that Belconnen intended, at all times following the Altitude Private Ruling, to treat any sales as being input taxed.

59 Belconnen’s selling agent for the residential units was Independent Property Group (IPG). Mr Matthew Wykes of IPG was the selling agent who dealt with Mrs Lloyd. He was not called to give evidence at trial, nor was the person within Belconnen who was responsible for giving instructions to Mr Wykes on behalf of Belconnen in the negotiations with Mrs Lloyd.

60 Mrs Lloyd gave evidence at trial by affidavit. She was not required for cross-examination. Her evidence was, therefore, unchallenged.

61 Mrs Lloyd gave evidence in her affidavit about her communications with Mr Wykes. Mrs Lloyd stated that after Mr Wykes had shown her unit 202 in the Altitude Apartments development (on 13 February 2015), there was a discussion about price and whether “there was any room for negotiation”, with particular reference to stamp duty. The listed price for the unit was $554,900, which was well over Mrs Lloyd’s budget. Mr Wykes then gave her a document that showed the amount of stamp duty on various purchase prices and Mrs Lloyd made a note on the document that the stamp duty on a price of $555,000 would be about $18,550. Mrs Lloyd was still unsure whether to proceed at that point, but Mr Wykes agreed that he would approach Belconnen to see if it would “waive” the stamp duty and she also asked if window coverings could be included as part of the purchase price, as the other three flats Mr Wykes had shown her had included fitted window coverings. Again, Mr Wykes advised that he would approach Belconnen “to find a solution” for her. On 16 February 2015, Mr Wykes called Mrs Lloyd and advised that that the seller (Belconnen) would pay the stamp duty and give her an allowance for her window fittings of $3,000. She then told Mr Wykes that she was interested in buying unit 202. On 19 February 2015, Mrs Lloyd paid a deposit of $1,000 to IPG.

62 Mrs Lloyd gave evidence in her affidavit that she did not know any solicitors or conveyancers in Canberra, so asked Mr Wykes if he could recommend one. He recommended a firm called Colquhoun Murphy, whom Mrs Lloyd engaged. Mrs Lloyd referred in her affidavit to email correspondence with Colquhoun Murphy, including an email from Ms Watt dated 25 February 2015 that attached a copy of the contract of sale, and another email from Ms Watt that included the statement:

The price is inclusive of GST (within the meaning of the A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (“the GST Act”), and the Buyer and Seller agree that any GST the seller is liable to pay to the Buyer will be calculated under Division 75 of the GST Act (i.e. “the Margin Scheme”).

63 After referring in her affidavit to the exchange of contracts and settlement, Mrs Lloyd gave evidence that: she was unable to recall whether, at the time of her purchase, she believed her purchase was subject to GST; however, she recalled reading the contract and the email from Ms Watt that stated that the price was inclusive of GST, and on that basis believed that she understood at the time that her purchase was subject to GST and the price she paid included GST.

64 Mrs Lloyd gave evidence in her affidavit that: (a) if Belconnen had told her before settlement that the sale was not subject to GST, she would have sought advice from Colquhoun Murphy or a local solicitor and discussed the matter with her family; (b) she would have asked Colquhoun Murphy what effect it had on her rights; (c) if told she might have a right to reduce the amount payable on completion because GST was not payable, she would have asked Colquhoun Murphy to take steps to ensure that Belconnen “did not get a windfall at [her] expense”; and (d) if Belconnen “had refused to make any adjustment”, she would have been prepared to walk away from the contract, including because: there were many other apartments on the market in Canberra at the time and she was in no particular rush; she was stretched beyond her budget as it was; and she dislikes “dishonesty and bad ethics”.

Sale of the residential unit in 2017

65 Mrs Lloyd gave evidence in her affidavit that she sold the residential unit in July 2017, for $490,000, approximately $64,000 less than the price she paid to Belconnen.

The reasons of the primary judge

Section B – general matters

66 The primary judge outlined the two representative proceedings that were before the Court in Sections B.1 and B.2 of the Reasons. In Section B.3, the primary judge discussed the centrality of the contracts of sale to the resolution of all issues before the Court (notwithstanding the abandonment of the breach of contract claim). The primary judge set out three reasons why the contracts were important at [25]-[29]. These included, relevantly for present purposes:

(a) First, although the main thrust of the case advanced in final submissions at trial was one based on application of restitutionary principles, restitution cannot impose a liability that would subvert or undermine an existing allocation of risk established by contract, referring to Mann v Paterson Constructions Pty Ltd (2019) 267 CLR 560 (Mann v Paterson) at [14]-[18] per Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ.

(b) Secondly, the assessment as to whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is a question of fact to be determined in the context of the evidence as to the alleged conduct and all relevant surrounding circumstances. The context, which is critical, includes the contractual context.

Section C – the contracts of sale

67 In Section C of the Reasons, the primary judge analysed the contracts of sale relevant to the two proceedings before the Court. The primary judge discussed the general form of the contracts and then considered the specific contracts that were in issue, including the Lloyd Contract.

68 In the course of discussing the general form of the contracts, the primary judge set out cl 24 of the Printed Terms. The primary judge observed at [42] that this provision had subclauses that would operate in different ways depending on the boxes crossed in the part of the Schedule relating to GST and the nature of the supply ascertained upon settlement. The primary judge observed at [43] that, in addition to the reference in the Schedule to the Price being GST inclusive and the part of the Schedule relating to GST, the terms of cl 24 “reflect the bargain relating to the imposition of GST”. The primary judge then discussed how the various aspects of cl 24 operated in the different circumstances contemplated by the standard contract.

69 The primary judge discussed the relationship between the part of the Schedule relating to GST and cl 24 of the Printed Terms at [71]-[85]. The primary judge made an important point (not challenged on appeal) at [72], namely that “the fact that the Price was GST inclusive is not the same as saying that the supply on completion would necessarily be a taxable supply, or that GST would necessarily be payable following the supply”. His Honour continued:

As explained above, the Contracts necessarily contemplated that the characterisation of the supply could change between exchange and settlement. Subject to further qualification by other terms, what “GST inclusive” means in the standard contract for the sale of real property in the ACT is that irrespective of what happens between exchange and settlement or prior to GST becoming payable, the Buyer will have no liability for payment of GST. In this sense, the “risk” of liability for GST lies with the Seller.

70 In a similar vein, the primary judge observed at [75] that the contracts of sale “necessarily accommodated the possibility, irrespective of the crossing or crossings in the GST Schedule [i.e. the part of the Schedule with the boxes relating to GST], that the nature of the supply could change when it later came time, upon completion, to make the supply”.

71 The primary judge discussed the significance of the crossing of the boxes relating to GST in the Schedule to the contracts of sale, and identified some representations that were conveyed by the developers to the purchasers by those crossings. After setting out the parties’ submissions on what was conveyed by the crossing of the boxes, the primary judge stated at [83]-[84]:

83 In my view, none of these positions is entirely correct, although I do consider the alternative argument of the Barton Developers to be closest to the mark. It seems to me plain that having regard to the Contracts as a whole, the crossing of the boxes on the Contracts provided to the solicitors for the Buyer by the solicitors for the Seller, conveyed: (a) a representation that at the time, it was the Seller’s opinion, that upon settlement, the supply would be as identified by the crossing of the GST Schedule and other relevant terms of the Contracts; and (b) impliedly, a representation that the Seller actually holds the opinion and that there was a reasonable basis for it (Completion Representations). I also consider a further representation was made (again a statement of opinion) that on the basis of the information then known to the Barton Developers, it was likely, following settlement, an amount representing GST on the supply would, in due course, be paid to the ATO (Likely Payment Representation).

84 It is accepted as between the parties, however, that whether in fact the Completion Representations and/or the Likely Payment Representation were actually conveyed to an individual purchaser is a question that cannot be answered in the abstract, divorced from consideration of all the communications between the Seller and Buyer which may bear upon the question.

Section D – findings relating to the Altitude proceeding

72 In Section D of the Reasons, the primary judge made findings of fact that related generally to the Altitude proceeding (as distinct from the particular facts of Mrs Lloyd’s case). This section included the primary judge’s findings relating to Mr Ryan and Mr Hindmarsh.

73 At [97], the primary judge noted that there was a controversy as to Mr Ryan’s credit as witness. At [98], the primary judge stated that the controversy primarily related to evidence that at relevant times Mr Ryan was unaware of the basis upon which Belconnen had contracted with Altitude group members and that he was not involved in instructing Clayton Utz about the contracts of sale relating to the Altitude Apartments. More specifically, there was dispute as to whether the Court should accept Mr Ryan’s evidence that, following the Altitude Private Ruling of 12 March 2013, Mr Ryan was unaware that Clayton Utz had continued to treat sales of the unexpired terms of leases with respect to residential units in the Altitude Apartments development as taxable supplies to which the margin scheme applied, rather than treating the sales as input taxed.

74 The primary judge stated at [99] that Mr Ryan’s affidavit evidence and email correspondence with Amanda Noy (which was exhibit A4), taken together, “give rise to real concerns”. After a detailed discussion of the evidence and competing submissions, the primary judge, at [113], rejected the suggestion that Mr Ryan was attempting to mislead the Court about his true recollection, but did not accept that the true position was as set out in his evidence in chief.

75 The primary judge set out some of Mr Ryan’s oral evidence at [114] and then made the following key findings at [115]:

When given orally, this highlighted evidence had a crystal clear ring of truth about it. I am satisfied that Mr Ryan did not, at any time during this process, give any real or considered thought to how the Altitude Contracts were drafted. If he was asked about the how the Altitude Contracts dealt with GST, at any time prior to the date of the emails which became exhibit A4, I am confident that Mr Ryan would have responded that he believed that the Altitude Contracts would have provided for the Price to be GST inclusive and that they would have treated the sales as taxable supplies to which the margin scheme would apply. In this respect, his professed ignorance of these matters in chief overstates the position; but this is not the same thing as saying that he did, in fact, turn his mind to the drafting until it was specifically raised by Clayton Utz. It is more likely that like most property developers, Mr Ryan was focussed primarily on the progress of the development and achieving sales and leaving the prosaic contractual details to others, unless the issue called for his specific involvement. If it had crossed his mind earlier, I think it likely the instructions given by exhibit A4 would have been given at an earlier time by Mr Ryan. Doing my best to assess the inherent probabilities and the oral evidence of Mr Ryan, it is more probable than not that a failure by him to provide instructions earlier is not, as Mrs Lloyd asserted in submissions, attributable to a malign intention to dissemble the true position, but rather his focus on other matters.

(Emphasis added.)

76 The primary judge discussed Mr Ryan’s evidence regarding the setting of the sale prices for, and the negotiation of, contracts of sale relating to the Altitude Apartments development at [116]-[122] of the Reasons. The primary judge stated at [123] that parts of the evidence given by Mr Ryan during cross-examination were unpersuasive. At [124], the primary judge rejected Mr Ryan’s evidence to the effect that Belconnen would not under any circumstances have agreed to reduce the sale price of Mrs Lloyd’s residential unit by any amount because GST was not payable. The primary judge set out his reasons for this at [125]-[130]. The primary judge found at [131]:

Particularly towards the end of a long project, I am satisfied on the evidence (including but not depending on the absence of evidence from those directly involved in pricing the 50 or so units at the end of the development) that the commercial position was such that it is more likely than not that Altitude was a willing vendor and hence potentially open to renegotiation as the price for securing or keeping a sale.

77 In relation to Mr Hindmarsh (who was not called to give evidence), the primary judge found at [139] that there was no sound basis upon which to conclude that Mr Hindmarsh had anything to do with the review and approval of the contracts of sale relating to the Altitude Apartments development.

Section F – Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case

78 Section F of the Reasons contains the primary judge’s consideration of Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case, which was part of the Governor Place proceeding. Although not directly relevant, it is necessary to refer to some parts of the primary judge’s reasons in this section to provide context for his consideration of Mrs Lloyd’s case.

79 In the context of the El-Zein’s case, the primary judge set out at [178]-[180] relevant legal principles concerning misleading or deceptive conduct, referring to Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Limited (2004) 218 CLR 592 at [37] per Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ, [109] per McHugh J; Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [26] per French CJ, [102] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ; and Chowder Bay Pty Ltd v Paganin [2018] FCAFC 25 at [30]-[31].

80 The primary judge also referred, at [185], to applicable principles as to when non-disclosure of information may amount to misleading or deceptive conduct, referring to Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Limited (2010) 241 CLR 357 at [20] per French CJ and Kiefel J; and Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky (1992) 39 FCR 31 at 32.

81 At [182], the primary judge rejected Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s pleaded “GST Representations case”.

82 The primary judge then considered the El-Zein’s “GST Omissions” case, namely that the Barton Developers failed to disclose to them that: (a) the Barton Developers intended to apply for, had applied for or had obtained the relevant private ruling; and (b) GST was not, or was unlikely to be, payable in respect of the sale of the unexpired term of a lease of a residential unit.

83 The primary judge concluded at [194]-[195] that, in circumstances where the Barton Developers expressed an opinion such as the Likely Payment Representation, a reasonable expectation existed that if it was unlikely that GST on the supply would be remitted to the ATO, this fact would be revealed. The primary judge found that that fact should have been disclosed in the circumstances (describing this as the “Relevant Omission”). The primary judge held that in all the circumstances, the non-disclosure constituted conduct that was likely to mislead or deceive.

84 The primary judge then considered causation and loss in the context of Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s misleading or deceptive conduct case, referring to relevant principles and cases. The primary judge described the way Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case was put at [200]-[202], noting that it had morphed into a “loss of opportunity to renegotiate” case. At [204], the primary judge accepted the proposition that if contravening conduct caused a person to forgo an opportunity to enter a contract that would have been on different and more favourable terms, the loss, subject to appropriate discounts, will be recoverable under s 82 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) or s 236 of the Australian Consumer Law, referred to Gates v City Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd (1986) 160 CLR 1 at 13 and Bullabidgee Pty Ltd v McCleary [2011] NSWCA 259 at [57]. However, the primary judge held that the “loss of opportunity to renegotiate” case was not established on the evidence: at [205]-[209].

85 The primary judge considered Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s restitution case in Section F.5 of the Reasons. The primary judge discussed the relevant case law, referring to: Mann v Paterson; Pavey & Matthews Pty Ltd v Paul (1987) 162 CLR 221; Roxborough v Rothmans of Pall Mall Australia Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 516 (Roxborough); Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89; Equuscorp Pty Ltd v Haxton (2012) 246 CLR 498; Australian Financial Services and Leasing Pty Ltd v Hills Industries Ltd (2014) 253 CLR 560.

86 It should be noted that the facts of Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case were different from those of Mrs Lloyd. Among other things, in Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case, the box alongside the words “Buyer and Seller agree to apply margin scheme” in the GST Schedule was not crossed (see the Reasons at [50]).

87 In the circumstances of Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case, the primary judge held that there was a relevant contractual gap, in that cl 24.6 of the Printed Terms (see [52] above) applied, but did not contemplate what actually occurred in their case: see the Reasons at [230]-[233]. Further, the primary judge, applying Roxborough, held that there had been a failure of consideration in respect of the GST component of the Price: see the Reasons at [243]-[244], [248], [253]. The primary judge then considered whether an order for restitution would be unjust in the sense discussed in the cases. In circumstances where the Barton Developers had repaid certain input tax credits and thereby changed their position, the primary judge concluded that there would be an injustice to the Barton Developers if they were required to make restitution of the entire amount referable to the GST: Reasons, [286]. His Honour concluded that Mr and Mrs El-Zein were entitled to have the Barton Developers account to them for an amount representing the GST paid by them pursuant to the terms of the contract, but excluding the proportion of that sum that was referable to the repayment of any input tax credit by the Barton Developers to the Commissioner: Reasons, [288].

Section G – Mr and Mrs Eppelstun’s case

88 The primary judge considered Mr and Mrs Eppelstun’s case, which was also part of the Governor Place proceeding, in Section G of the Reasons. In the context of the misleading or deceptive conduct case, the primary judge held at [295] that the Barton Developers conveyed to Mr and Mrs Eppelstun the Completion Representations and the Likely Payment Representation (as described in the Reasons at [83]). The primary judge also held, at [296], that the Barton Developers conveyed what his Honour defined as the “Post-ruling Representation”. As the primary judge found a comparable representation was made to Mrs Lloyd, it is necessary to set out the terms of this representation. The primary judge stated at [296]:

As noted above, it [is] important to bear in mind that what was conveyed to Mr and Mrs Eppelstun and their solicitor occurred after the Governor Place Private Ruling was obtained (and at a time when the proposed supply was clearly never going to be taxable). Having regard to the terms of the draft counterpart Eppelstun Contracts as a whole (see [53]-[55] above) and absent any further relevant communication, what was conveyed to Mr and Mrs Eppelstun and their solicitor by the Barton Developers, albeit unintentionally, was that on the information then available to the Barton Developers, that: (a) it was likely GST was payable in respect of the sale of the relevant Governor Place Unit; and (b) it was likely an amount representing GST on the supply would, in due course, be paid to the ATO. In the balance of these reasons, I will describe what was conveyed as the Post-ruling Representation. This was a continuing representation until completion. For completeness, I note that I also consider it was impliedly represented that the Seller actually held the opinion conveyed and that there was a reasonable basis for it, but it is unnecessary for the case of Mr and Mrs Eppelstun (or, for that matter Mrs Lloyd whose case against Belconnen I will consider below), to consider this implied representation further.

89 The primary judge provided additional reasons for finding that the Post-Ruling Representation was made at [298] of the Reasons. At [299], the primary judge found that the Barton Developers’ conduct in making the representation was misleading and deceptive. In these circumstances, the primary judge considered that framing the conduct in terms of an omission added nothing to the case. The primary judge then considered causation and loss, explaining that the case ultimately presented was that, depending on legal advice, Mr and Mrs Eppelstun would have taken all reasonable steps to obtain a lower purchase price and that they suffered loss and damage by settling on the purchase. The primary judge rejected this case on the evidence: Reasons, [303].

90 The primary judge considered Mr and Mrs Eppelstun’s restitution case in Section G.5. The primary judge considered there to be a significant difference between their case and that of Mr and Mrs El-Zein. In Mr and Mrs El-Zein’s case, the primary judge had held that there was a contractual gap, in circumstances where cl 24.6 applied but did not contemplate what had actually occurred. However, in relation to Mr and Mrs Eppelstun, the primary judge considered that no contractual gap existed, because cl 24.5 of the Printed Terms (see [52] above) covered the situation. The primary judge therefore rejected the restitution claim. The primary judge’s reasoning (which is also relevant to Mrs Lloyd’s case) was as follows:

308 Unlike the El-Zein Contract (where cl 24.6 did apply because the sale is a taxable supply but the margin scheme did not apply), as I have explained above, properly construed, the bargain struck between the Barton Developers and Mr and Mrs Eppelstun was that the supply was to be taxable and that the margin scheme was to apply. When engaged, cl 24.5, it will be recalled, expressly provided that the Barton Developers warranted: first, they could use the margin scheme; and secondly, they promised that they would. Although this warranty may have been given by the Barton Developers unintentionally, it was part of the bargain and it was breached. There is no relevant gap in the Eppelstun Contract.

309 As Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ explained in Mann v Paterson at 10 [24]:

In Roxborough, consistently with the view later taken in Lumbers, Gummow J explained that restitutionary claims, such as an action to recover moneys paid on the basis of a failure of consideration, “do not let matters lie where they would fall if the carriage of risk between the parties were left entirely within the limits of their contract”. His Honour was at pains to explain that where a plaintiff already has “a remedy in damages ... governed by principles of compensation under which the plaintiff may recover no more than the loss sustained”, allowing the plaintiff to claim “restitution in respect of any breach ... would cut across the compensatory principle” of the law of contract.

310 To allow a claim in the present circumstances would cut across the agreement which identified the nature of the warranty given and allowed a claim in breach of contract to be the consequence of breach. Put another way, the common law imposed an obligation to pay damages for breach of contract, in the event of breach, which was relevantly “substituted” for the primary obligations contained in the cl 24.5. The remedy of Mr and Mrs Eppelstun is not restitutionary, it is a common law action for breach of contract. The fact that compensatory damages may not be available (and only nominal damages arise) cannot be relevant to the question as to whether the contract allocated risk and provided for the consequences of breach.

Section H – Mrs Lloyd’s case

91 The primary judge considered Mrs Lloyd’s misleading or deceptive conduct case in Section H.3 of the Reasons. The primary judge held that Belconnen had made the Post-Ruling Representation (as defined in [296] of the Reasons) to Mrs Lloyd and that its conduct was misleading and deceptive. The primary judge’s core reasoning on this issue was as follows:

314 As noted above, the Lloyd Contract was entered into two years subsequent to the Altitude Private Ruling having been issued and the amended BAS being lodged. From this time the sale by Belconnen of the Altitude Units became input taxed supplies.

315 In the ASOC at [42]–[45] the GST Representation was pleaded (that Belconnen represented to Mrs Lloyd that GST was payable in respect of the sale of the unexpired term of a Unit Lease for a Unit; and GST would be paid to the ATO). The GST Omissions were also pleaded (that Belconnen failed to disclose that: (a) it had obtained the Altitude Private Ruling; (b) GST was not payable in respect of the sale of the unexpired term of a Unit Lease for a Unit; and/or (c) Belconnen “intended to retain an amount equivalent to the component of the Price referable to GST as purely a windfall gain”.

316 It is not in dispute that at all material times prior to the completion of the Lloyd Contract, Belconnen did not disclose to Mrs Lloyd that Belconnen: (a) had obtained the Altitude Private Ruling; and (b) GST was not payable in respect of the sale of the relevant Altitude Unit. This was despite the fact that Belconnen intended, at all times following the Altitude Private Ruling, to treat any sales as being input taxed. Again, despite the pleading, I do not consider that there is any prejudice in dealing with the case with regard to what I have defined above as the Post-ruling Representation.

317 For the same reasons I have explained in relation to Governor Place, when properly analysed, what Belconnen’s statement of opinion conveyed to Mrs Lloyd and her solicitor was that on the information then known to Belconnen, it was likely GST was payable in respect of the sale of the relevant Altitude Unit and it was likely an amount representing GST on the supply would, in due course, be paid to the ATO: that is, what I have described above as the Post-ruling Representation. Again, there was simply no reasonable basis for the statement of opinion at the time it was conveyed as it was plainly evident at that time the supply would be input taxed. As a result, the conduct of Belconnen in making the Post-ruling Representation was misleading and deceptive in contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL. An omission case adds nothing in these circumstances.

92 The primary judge considered Mrs Lloyd’s knowing involvement case against Mr Hindmarsh and Mr Ryan at [318]-[324]. The primary judge referred at [320] to Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 (Yorke v Lucas) at 667, 670 and 677; Rinbridge Marketing Pty Ltd v Walsh [2000] FCA 1738 (Rinbridge) at [26]; and Kovan Engineering (Aust) Pty Ltd v Gold Peg International Pty Ltd (2006) 234 ALR 241 at [114]. His Honour rejected the knowing involvement case for the following reasons:

322 In relation to Mr Ryan, I have found (see [115] above) that it was more probable than not that a failure of him to provide instructions was a consequence of the fact that he simply did not turn his mind at the relevant time to the Altitude Contracts, including the Lloyd Contract, and his focus was on other matters. Further, I do not find that he had knowledge of the pleaded fact, dealt with elsewhere, that Belconnen’s retention of the amount paid by Mrs Lloyd for GST was “purely a windfall gain”. Indeed, for the reasons that I have already explained in relation to the case of Mr and Mrs El-Zein, I do not consider the full amount paid by Mrs Lloyd constituted a windfall gain. Moreover, there is insufficient evidence to prove Mr Ryan knew of the content of all the dealings between the agent and Mrs Lloyd and what in truth passed between them. Again, one of the difficulties with the way the case is pleaded is that it is pitched at such a high level of generality by reference to group members; but a case of knowing involvement in contravening conduct directed to an individual requires knowledge of what was conveyed (and not conveyed) to the individual, which amounted to the conduct which was in contravention of the statutory norm. This is not a prospectus case or a case involving representations to a market; all parties accepted that this is a case which involves consideration of the individualised dealings between a vendor and purchaser, represented by solicitors, in a conveyance. It follows, for a number of reasons, the knowing involvement case against Mr Ryan must fail.

323 In the case of Mr Hindmarsh, although I accept knowledge may more easily be inferred against a respondent who fails to give evidence, the “proven facts” must, however, be “capable of raising the inference”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1800; (2001) 115 FCR 442 at 556 [509], 557 [515], 558 [522], 559 [529] per Hill J; Bowler v Hilda Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 899 at [79] per Finn J. I have found in relation to Mr Hindmarsh that Mrs Lloyd has failed to prove that Mr Hindmarsh had anything to do with the review and approval of the Altitude Contracts (see [139] above) or, for that matter, knowledge of the content of the dealings with purchasers including Mrs Lloyd or that Belconnen’s retention of an amount equivalent to the component of the Price referable to GST was purely a windfall gain. It follows that no knowing involvement case can be made out against Mr Hindmarsh.

(Emphasis added.)

93 The primary judge considered causation and loss (in respect of the misleading or deceptive conduct case against Belconnen) at [325]-[371]. The primary judge set out the relevant part of Mrs Lloyd’s pleading and indicated that the way the damages case was put had changed (or at least reduced in scope significantly) during the course of the hearing: Reasons, [331]. Initially, it had seemed that there was a case based upon Mrs Lloyd’s capital loss of $64,000 (Direct Loss Case). This had been supplemented by a case that, given her evidence that she would have sought to negotiate a discount, her loss amounted to the component of the Price referable to GST (Loss of Opportunity to Negotiate Case). The primary judge rejected the Direct Loss Case on the evidence (at [336]). There is no challenge to that conclusion and it can be put to one side.

94 The primary judge next considered the Loss of Opportunity to Negotiate Case. The primary judge rejected Belconnen’s submission that it would not have been prepared to compromise on the Price of the residential unit, and found that Belconnen would likely have been willing to discount the price: at [340]. The primary judge discussed the applicable principles concerning a case based on loss of a commercial opportunity, referring to cases including Sellars v Adelaide Petroleum NL (1994) 179 CLR 332; Badenach v Calvert (2016) 257 CLR 440; and Masters Home Improvement Australia Pty Ltd v North East Solution Pty Ltd [2017] VSCA 88.

95 The primary judge considered whether the Loss of Opportunity to Negotiate Case was within the pleading, holding that it was: at [351]-[353]. Significantly, the primary judge rejected the loss of opportunity case based on the period prior to the exchange of contracts, stating at [354]:

354 Before leaving the pleading and submissions, it is important to be specific about the opportunity the subject of the claim and when it arose. Although the submissions of Mrs Lloyd did not abandon a case premised on a counterfactual whereby the true position was revealed prior to exchange, I am satisfied that any such case is unavailable. Mrs Lloyd settled upon her intention to purchase her flat without any reference whatsoever to GST. She entered into negotiations with Belconnen through Mr Wykes, was satisfied with the result, and decided to proceed and pay an initial deposit following the call with Mr Wykes on 16 February 2015. If the draft Lloyd Contract subsequently provided to her had revealed the true position and its provision had not amounted to conduct conveying the Post-ruling Representation, I am not satisfied that it would have made any difference to her decision to exchange and then later settle and pay the Price for which she had bargained (indeed I would go further and say I am affirmatively satisfied it would have made no difference).

(Emphasis added.)

96 The primary judge held at [355] that the Post-Ruling Representation was a continuing representation, in the sense that it continued to be made by Belconnen to Mrs Lloyd in the period between the date of the contract and the date of settlement. The primary judge then examined the loss of opportunity case with respect to that period by addressing the following questions:

(a) Was there an opportunity of some value?

(b) Would Mrs Lloyd have pursued the opportunity?

(c) What amount should be awarded having regard to the prospects?

97 In relation to (a) above, the primary judge found that during the relevant period (that is, between exchange of contracts on 10 March 2015 and settlement on 7 April 2015) it was more likely than not that Belconnen was “a willing vendor and hence potentially open to renegotiation as to the price for securing or keeping a sale”: at [356]. The primary judge found that the opportunity to negotiate with Belconnen had a “non-negligible value, in that it was real and more than speculative”.

98 In relation to (b) above, namely whether Mrs Lloyd would have pursued the opportunity, the primary judge held that she would have, reasoning at [357]-[358]:

357 Additionally, I am comfortably satisfied that if Mrs Lloyd had been apprised of the true position during the relevant period that the Lloyd Contract incorrectly indicated that the supply was taxable (and hence the Post-ruling Representation was wrong), this would have been of real significance to her. Mrs Lloyd was evidently no shrinking violet. She not only was someone who was not coy about negotiating, but gave unchallenged evidence she was prepared to walk away if Belconnen “had refused to make any adjustment” to the amount payable. Importantly, she was a person who obviously had a relatively acute sensitivity about business ethics giving the following (again unchallenged) evidence in her affidavit at [68]:

(c) I dislike dishonesty and bad ethics, and I would have seen [Belconnen’s] attempt to keep the GST component for itself as bad practice. I have had bad experiences with real estate agents before, in Lismore, and the justice of these situations is important to me; and

(d) I have been a Justice of the Peace in both the ACT and New South Wales, and I believe that businesses should treat their customers honestly and fairly and should ensure their contracts are correct, accurate and compliant with relevant laws. I pride myself in being ethical as a person and as a Rotarian, so expect others to act the same.

358 In the relevant counterfactual Mrs Lloyd would have had concerns about what she subjectively would have perceived as bad practice and would have tried to reopen negotiations. But even if she was somehow assuaged as to her concerns that Belconnen had attempted to do something wrong (for example, by reason of Belconnen voluntarily correcting the Post-ruling Representation and revealing the true position prior to settlement), I do not think there is any real doubt she would have attempted to use this information revealed belatedly to her advantage and tried, to use Mr Ryan’s words, to “drive the price down from [Belconnen]” (T175.22 2.5.19). In this way, causation is established because the contravening conduct deprived Mrs Lloyd of the opportunity to negotiate a better bargain: see Bullabidgee Pty Ltd v McCleary at [57] per Allsop P (Basten and Young JJA agreeing).

99 In relation to (c) above, namely the amount that should be awarded to Mrs Lloyd having regard to the prospects of a beneficial outcome, the primary judge observed that this aspect of the analysis was “more complicated” (at [359]). The primary judge’s reasoning was at [359]-[368]. This included the following passage at [362]:

Belconnen’s submission (SBR [485]) was simply that the evidence is insufficient to support the proposition that it would have compromised on price to the extent of any “windfall gain” of GST; it also went so far as to submit (SBR [486]) that the fact Belconnen compromised on other concessions (such as stamp duty rebates and other inclusions) “is simply irrelevant”. Although, for reasons I will explain, there is some substance in the first of these submissions, the second has no merit at all. It is wrong because there clearly was a recognition that to secure sales, at least towards the end of the project, Belconnen was prepared to move away from the listed prices and negotiate. Although the evidence as to how these negotiations on an individual basis were conducted, and how far Belconnen was prepared to go is opaque (because of the forensic decision of Belconnen not to call anyone directly involved in the negotiations, or in the ongoing meetings discussing pricing with the selling agent), the picture of a willing vendor is clear. And it is picture which stands in contrast to that which emerges in relation to Stage 1 of the Governor Place development. This willingness to treat prior to exchange with individual purchasers, (including, importantly, Mrs Lloyd), together with the “soft” market for the remaining flats, provides important context in assessing the degrees of probability or possibility of Mrs Lloyd securing a commercial advantage if she became armed with information that allowed her to “drive the price down from [Belconnen]” between exchange and completion.

It is convenient to note that the above reasoning is criticised by Belconnen on the basis that the evidence about discounts related to the situation before exchange of a contract, but the primary judge was here considering the position after a contract had been entered into.

100 The primary judge stated at [364] that the maximum value that could be achieved in the negotiation was $46,759 “being the agreed amount equivalent to the component of the Price referable to GST pursuant to the terms of the Lloyd Contract”. It appears that the reference to this being an “agreed amount” was to it being agreed between the parties at trial (as reflected in Annexure A to the Reasons). The primary judge reasoned:

365 When one comes to the probability of realising the opportunity, I have to do the best that I can, notwithstanding the lack of clarity as to the circumstances in which the negotiation would have taken place. The context in which the negotiations took place would have been of some importance. For example, even in the absence of evidence from Mrs Lloyd’s conveyancing or family solicitor, it is possible to conclude that any competent legal advice given to Mrs Lloyd during the relevant period is that the incorrect information given to her pre-exchange, more likely than not, gave her a basis to at the very least threaten Belconnen with the prospect Mrs Lloyd would seek statutory relief to relieve her of her obligations under the Lloyd Contract and seek recovery of an amount representing that paid over by way of deposit. For reputational reasons, as well as for more specific reasons relating to a potential loss of the individual sale, I do not consider that this is a prospect that Belconnen would have faced with equanimity. This would have dealt Mrs Lloyd a very powerful hand in doing a deal. But another scenario is possible, that is, the negotiations took place following an unsolicited approach from the agent Mr Wykes explaining that an innocent mistake had been made and that Belconnen were willing, in all the circumstances, as a gesture of goodwill, to “throw in” better quality appliances and other miscellaneous benefits. Although, in either of the scenarios I have outlined, I am confident that: (a) Mrs Lloyd would have approached any negotiation with some competence and without being shy seeking out the best deal she could; and (b) Belconnen would have been keen to do what it could do to not jeopardise the completion of the sale to Mrs Lloyd, these are very different, yet equally plausible scenarios.

366 Further, much might depend upon Mrs Lloyd’s subjective reaction to the circumstances in which the information was revealed. Her Rotarian mission of maintaining high ethical standards in her professional and personal life was evidently of importance to Mrs Lloyd. Although implicit in her unchallenged evidence is that upon understanding the true position she would have allowed Belconnen the opportunity “to make any adjustment” to the amount payable before considering walking away (hence leading me to conclude she would have pursued the opportunity), the vigour with which she would have pursued the negotiations may have been rationally affected by her sense of how far she thought Belconnen had strayed from playing with a straight bat in its dealings with her.

367 The uncertainties of context, unavoidable in a case of loss of opportunity to negotiate such as the present, demonstrate the difficulties with the task of informed estimation. But the inherent difficulties and the impossibility of precision do not mean the task cannot be assayed.

368 Having regard to the circumstances proved in the evidence, and recognising that giving a percentage figure gives a patina of precision to a task which is no more than informed estimation, the degrees of probabilities or possibilities are such that if the true position had been revealed post-exchange and prior to completion, then I expect that Mrs Lloyd and Belconnen would have done a deal to secure settlement of the Lloyd Contract and that this would have involved Mrs Lloyd securing a benefit. But given the inherent uncertainties, I consider that having identified the maximum value of the opportunity at $46,759, it should be discounted and the sum awarded should reflect a 50% probability of realising the opportunity.

101 Accordingly, the primary judge concluded (at [369]) that Mrs Lloyd was entitled to an award of statutory compensation in an amount calculated as explained above, together with interest from the date of settlement, namely 7 April 2015. In other words, Mrs Lloyd was entitled to compensation of approximately $23,000 plus interest.

102 Insofar as Mrs Lloyd submitted that she had lost an opportunity to “walk away”, the primary judge rejected this part of her case at [370].

103 The primary judge considered Mrs Lloyd’s restitution case at [373], essentially adopting his Honour’s reasoning in relation to Mr and Mrs Eppelstun. The primary judge stated at [373]: