Federal Court of Australia

District Council of Streaky Bay v Wilson [2021] FCAFC 181

ORDERS

DISTRICT COUNCIL OF STREAKY BAY Appellant | ||

AND: | CAROLINE WILSON (and others named in the Schedule) First Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 October 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Leave is granted to amend the application for leave to appeal in terms of the proposed amended application for leave at annexure CD-03 to the affidavit of Ceilia Divakaran sworn on 28 June 2021.

2. The interlocutory application filed on 28 June 2021 for leave to adduce further evidence in support of the amended application for leave to appeal is, to the extent necessary, granted.

3. Leave to appeal in the terms of the draft notice of appeal at annexure CD-03 to the affidavit of Ceilia Divakaran sworn on 28 June 2021 is granted.

4. To the extent that the interlocutory application filed on 28 June 2021 seeks leave to adduce fresh evidence on the appeal pursuant to s 27 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and r 36.57 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), that application is refused.

5. The interlocutory application filed on 6 September 2021 to further amend the draft notice of appeal dated 28 June 2021 in terms of annexure CD-05 to the affidavit of Ceilia Divakaran sworn on 6 September 2021 is refused.

6. The appeal is dismissed.

7. The appellant is to pay the costs of the first-to-seventh respondents and the eighth respondent of and incidental to the application referred to in Order 5 as agreed or, if not agreed, to be determined by a Registrar.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction and overview

1 In 1997, the Wirangu native title applicant (Wirangu respondent) lodged an application on behalf of the Wirangu people for a determination of native title under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). The respondents included the State of South Australia (State), the District Council of Streaky Bay (Council), and, at a later stage, the Streaky Bay and Districts Golf Club Inc (Club).

2 The Streaky Bay golf course (golf course) falls within the claim area and is situated on an elongated area of land of about 31 hectares (land) which runs through the centre of the town of Streaky Bay in South Australia, roughly parallel with the coast. A significant proportion of the land is Crown land which is shown on early maps of Streaky Bay dating from 1877 to 1885. Golf has been played on various parts of the land since about 1929.

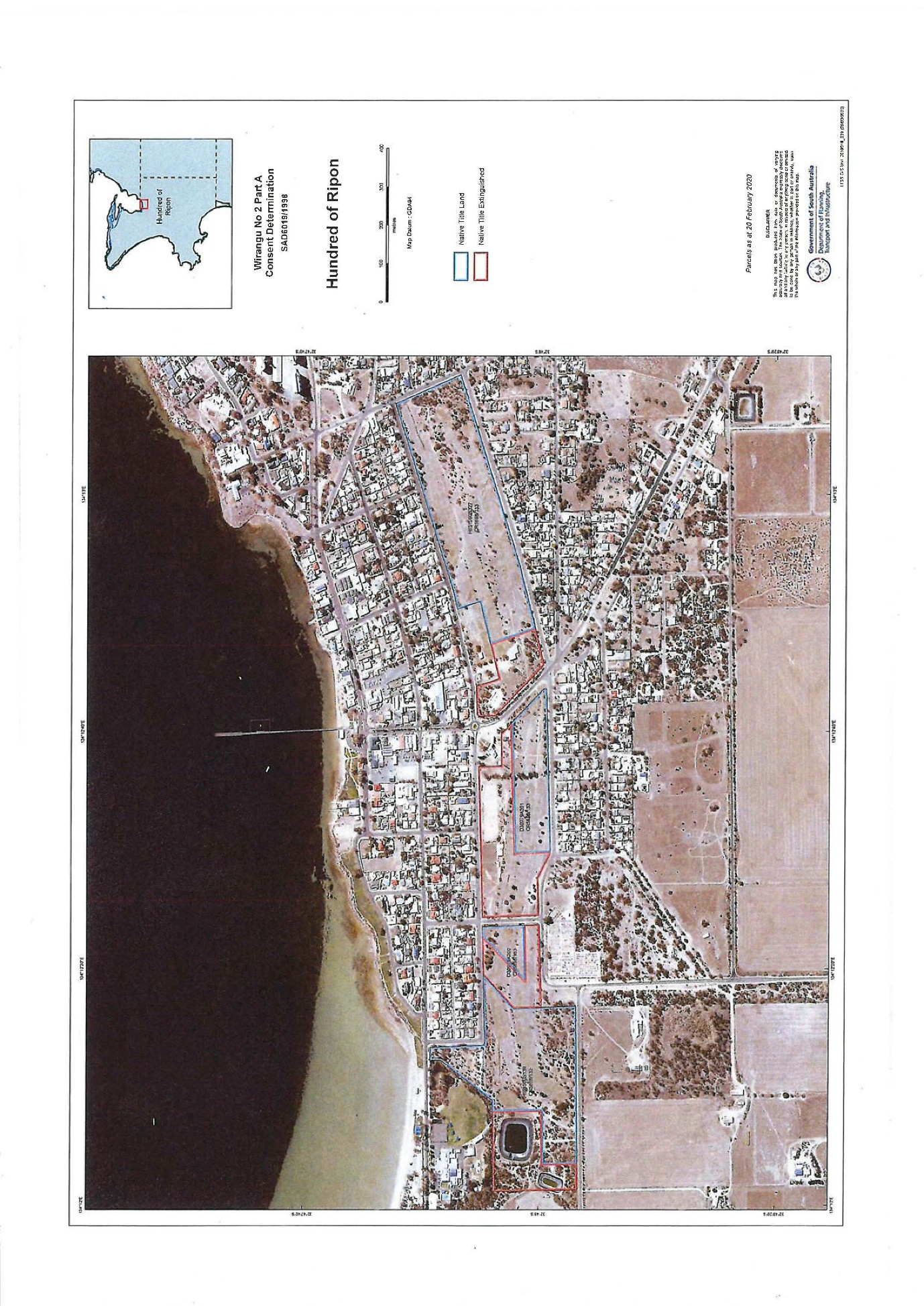

3 There is no dispute that the members of the claim group, the Wirangu respondent, are the holders of native title in the land subject to the resolution of tenure disputes (Reasons of the primary judge at [9]). This assumption underlies the draft native title determination proposed to be made by consent in accordance with s 87A of the NTA (proposed CD), which was circulated by the State on 28 February 2020 to the native title applicant, the Council and the Club.

4 On 26 November 2019, the Court ordered the Council and the Club to identify those parts of the proposed CD to which they would not consent, giving rise to the present dispute.

5 The Council identified two bases for its contention that native title had been extinguished with respect to the whole of the golf course, namely:

(1) the construction of public works allegedly in the nature of major earthworks on the land on or before 31 December 1993 which was either valid if construction pre-dated 1975 or validated by s 34 of the Native Title (South Australia) Act 1994 (SA) (NTA (SA)) as a category A past act; or, in the alternative,

(2) a lease (the Lease) encompassing the land which was “granted or intended to be granted” by the Council to the Club between 1 January 1994 and 23 December 1996 which was valid as an intermediate period act under s 32A of the NTA (SA).

6 In each case, the act in question is said to constitute a previous exclusive possession act which extinguished all native title in the land either by virtue of, or as confirmed by, s 36G of Part 6 of the NTA (SA) (which is enacted consistently with s 23E of the NTA).

7 In this regard, s 31(2) of the NTA (SA) provides that a word or expression in the NTA (SA) has the same meaning in Part 6 (comprising ss 31-38) as in the NTA, unless a contrary intention appears. In turn, an act is a previous exclusive possession act as defined by s 23B(2) of the NTA if it is valid (including because of the validating provisions in Division 2 or 2A of Part 2 of the NTA) and it consists of the construction or establishment of any public work prior to 23 December 1996 (s 23B(7), NTA). Section 23B(2) of the NTA also defines “previous exclusive possession act”, relevantly, as follows:

(2) An act is a previous exclusive possession act if:

(a) it is valid (including because of Division 2 or 2A of Pt 2); and

(b) it took place before 23 December 1996; and

(c) it consists of the granting or vesting of any of the following:

…

(vi) a community purpose lease (see section 249A)

…

(viii) any lease (other than a mining lease) that confers a right of exclusive possession over particular land waters.

8 The two bases on which extinguishment in whole was said to have occurred were the subject of determination as a separate question by the primary judge which was formulated in the following terms:

Whether the applicant’s claimed native title in the land referred to at [3] of the affidavit of Kerin Dare Rain affirmed on 15 April 2020, or alternatively in the portions of that land delineated by the blue boundaries on the map contained in annexure KDR2 (at page 107) (in either case, ‘the land’), has been wholly extinguished by either:

a. the construction of public works in the nature of major earthworks on the land on or before 31 December 1993, [the Earthworks question] or:

b. a community purposes lease, or alternatively a lease conferring exclusive possession, in respect of the land granted or intended to be granted by the District Council of Streaky Bay to the Streaky Bay Golf Club Inc, after 1 January 1994 and before 23 December 1996 [the Lease question].

(For convenience and consistently with her Honour, we refer to questions (a) and (b) of the separate question as the Earthworks and the Lease questions respectively in our reasons.)

9 At [11]-[12] of her Honour’s Reasons, the primary judge answered both questions in the negative, holding that she was not satisfied that the Wirangu respondent’s native title in the land had been wholly extinguished by either of the alleged acts. As in Peterson v Western Australia [2017] FCA 1056 at [51], the orders answering the separate question in the negative are not “final” because the native title determination application proceedings are continuing and the separate question has resolved only one issue, albeit that the remainder may ultimately be resolved by agreement to the proposed CD. As the decision on the separate question is interlocutory in character, leave to appeal is required pursuant to s 24(1A) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1975 (Cth) (FCA Act); see also eg Bodney v Bennell [2008] FCAFC 63; 167 FCR 84 at [6] and [209] (the Court); and Roberts on behalf of the Widjabul Wia-Bal People v Attorney-General of New South Wales [2020] FCAFC 103 at [3] (the Court).

10 By an amended interlocutory application filed on 29 June 2021, the Council seeks leave to amend its application for leave to appeal filed on 18 January 2021 and leave to adduce fresh evidence in support of its amended application for leave to appeal and, if leave is granted, the appeal.

11 If successful in obtaining leave to appeal, the Council appeals from the negative determination made by the primary judge on the following grounds:

Earthworks question

1. The Judge erred at [71] of the reasons for judgment published as Wilson v State of South Australia (No 4) [2020] FCA 1805 in finding that scrape 16 is approximately 15 square metres in area. The Judge should have found that scrape 16 is approximately the same area as the footprint of many of the houses around the perimeter of the course (i.e. more than 100 square metres).

2. The Judge erred at [104], [109]-[111] and [114] in interpreting the definition of ‘major earthworks to exclude:

a. ‘the erection of fixtures or features upon or above the land’s surface’; and

b. the filling of land.

3. The Judge erred at [104] and elsewhere in interpreting the word ‘land’ within the definition of ‘major earthworks’ to mean only subsurface or soil.

4. The Judge erred at [105]-[106] in finding that the works occurring prior to 1994 to create and alter the fairways were not ‘major earthworks’.

5. The Judge erred at [109] in finding that the works occurring prior to 1994 to create 13 and remove 3 scrapes and to create and remove the various mounds shown in the aerial photographs in evidence, were not ‘major earthworks’.

6. Alternatively, the Judge erred at [109] in finding that the works occurring prior to 1994 to create 13 and remove 3 scrapes, were not major earthworks.

7. The Judge erred at [111] in failing to find that the works occurring prior to 1994 to: (i) to create 13 and remove 3 scrapes; (ii) create and remove the various mounds shown in the aerial photographs in evidence; and (iii) to create and remove the various tee-off points, were not in aggregate ‘major earthworks’.

8. The Judge erred at [115] in failing to find that the works occurring prior to 1994 to: (i) create 13 and remove 3 scrapes; (ii) create and remove the various mounds shown in the aerial photographs in evidence; (iii) create and remove the various tee-off points; and (iv) create and alter the various fairways, were not in aggregate ‘major earthworks’.

9. The Judge erred in failing to find that earthworks done between 1975 and 1994 involving in the order of 750 cubic metres of earth, together with (or without) the construction of an approximately 1,600 sq m gravel driveway and car park, done for the purpose of improving the golf course, was not ‘major earthworks’.

10. The Judge erred in failing to find that the physical conversion of the land in its natural state at the time of colonisation to a golf course as at 1 January 1994 was not a ‘major disturbance’ to the land and so ‘major earthworks’ (and so a ‘public work’).

11. In respect of Grounds 3-8 above, in each case the Judge further erred in not finding that s 251D had the effect that the whole of the golf course (alternatively, the relevant areas containing relevant feature[s] comprising a major earthwork and its associated tee-off, fairway and hole) was land on which those public works were situated (alternatively, established) because that area was adjacent land and the use of that area was incidental to the operation of each thing which comprised a major earthwork or which was considered in aggregate part of a major earthwork (i.e. the playing of golf).

12. The Judge erred at [112] and [113] in her Honour’s choice of comparator or identification of context. The proper comparison was the size and scale of the golf course compared with its townscape surrounds; alternatively, the size and scale of the fairways, scrapes, tee-offs, and mounds compared with the townscape surrounds; in the further alternative the size and scale of the fairways, scrapes, tee-offs, and mounds compared with the cadastral parcel in which they were situated.

13. Having found at [102] that the infilling of the Sceale Bay Road involved a ‘major disturbance to the land’ (and so, presumably, ‘major earthworks’ and so a ‘public work’) the Judge erred in failing to hold that s 251D had the effect that the whole of the golf course (alternatively, the area containing the two fairways which had crossed the said road) was land on which that public work was situated (alternatively, established) because that area was adjacent land and the use of that area was incidental to the operation of the infilled road (i.e. the playing of golf).

14. Having found at [101] that the club rooms were a public work and that the associated driveway and carpark involved a ‘major disturbance to the land’ (and so, presumably, ‘major earthworks’ and so a ‘public work’) the Judge erred at [101]-[102] in failing to hold that s 251D had the effect that the whole of the golf course (alternatively, the whole cadastral parcel containing the club rooms) was land on which that public work was situated (alternatively established) because that area was adjacent land and the use of that area was incidental to the operation club rooms and car park (i.e. the playing of golf).

15. The Judge erred at [113] in not finding that tee-off 2 (described at [74]) and the Crows Nest scrape (described at [70]) were not ‘major earthworks’.

16. The Judge further erred in not finding that s 251D had the effect that the whole of the golf course (alternatively, the area containing tee-off 2 and associated fairway and hole, and the area containing the Crows Nest scrape and associated fairway and tee-off respectively) was land on which those public works were situated (alternatively, established) because that area was adjacent land and the use of that area was incidental to the operation of the tee-off and/or the scrape (i.e. the playing of golf).

Lease question

17. The Judge erred in finding at [172] that the Council’s letter of 14 January 1994 to the Club did not attach a lease, alternatively an offer of a lease with sufficiently certain terms to give rise to a lease in equity upon the Club accepting the said offer.

18. The Judge erred at [173] in failing to find that the Club by letter dated 11 February 1994 communicated to the Council its acceptance of the terms of that lease, alternatively the terms of a lease proposed by the Council in its offer.

19. The Judge erred in finding (e.g. at [197], [199]) that the Club did not communicate its acceptance of the terms of any lease prior to 23 December 1996.

20. The Judge should have found that the Club:

a. accepted the lease (alternatively, a proposal to lease) attached to the Council’s 14 January 1994 letter by resolution at its meeting of 9 February 1994; and

b. communicated its acceptance of the said lease to the Council prior to 23 December 1996; or

c. in the alternative to (b) gave effect to the said lease (alternatively the proposal to lease) by complying with its terms.

21. The Judge erred at [200] in finding that there was not a specifically enforceable agreement for a lease, or a lease enforceable in equity prior to 23 December 1996.

22. The Judge should have found that:

a. prior to 23 December 1996, the Council granted a lease to the Club:

i. for the period 1 July 1994 to 30 June 2004;

ii. for the area depicted in the map annexed to the document entitled Memorandum of Lease dated 11 April 1997 (leased area);

iii. which was executed by the Club on 11 April 1997; and

iv. which was executed by the Council on 18 April 1997, and

b. the said lease was enforceable in equity, at least by the Club, prior to 23 December 1996;

c. the said lease was a ‘lease’ as defined by the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA); and

d. the said lease was at all times a community purposes lease within the meaning of NTA s 249A; and

e. the said lease therefore extinguished native title within the leased area.

12 By further amended draft notice of appeal provided to the Court on the Sunday afternoon prior to the hearing, the Council seeks to raise yet a further ground of appeal being:

Pre-existing right-based act issue

23. In the alternative to Ground 22, the judge erred in fact and law in failing to find that:

a. the Council by letter provided a lease in executable form to the Club in September 1994 with an invitation to execute it;

b. the provision of that lease was an offer made in good faith to grant that lease, evidenced by the said letter which is dated 14 September 1994;

c. the Club in good faith accepted that lease by executing it on 11 April 1997;

d. the acceptance of the lease gave effect to the Council’s offer;

e. acceptance of the lease conferred a right of exclusive possession upon the Club in relation to the subject land (or so much of it as is in dispute);

f. the acceptance of the lease was a pre-existing right-based act within the meaning of s 24IB(b) (which applies to the acceptance by virtue of Sch 5 cl 3 to the Native Title Amendment Act 1998);

g. by reason of s 24ID(1), the acceptance of the lease (a) was valid, and (b) extinguished any native title in relation to the subject land (or at least so much of it as is in dispute).

13 It was not in issue that proposed ground 23 is new, having not been raised at trial.

14 Upon being served with this further proposed ground of appeal the day before the hearing, the State sought to be heard on the substantive application, it having previously filed a submitting notice. The Court was informed in the luncheon adjournment that the Commonwealth did not wish to be heard.

15 Given the eleventh-hour nature of the further proposed ground of appeal, the parties were afforded the opportunity to make written submissions on the additional ground, and on whether leave should be granted to entertain it, in order to avoid delaying the substantive application.

16 For the reasons set out below, the application to further amend the amended application for leave to appeal to raise ground 23 should be refused. Leave should be granted, in so far as it is required, to rely upon the further evidence in support of the application for leave to appeal but the application for leave to adduce further evidence on the appeal should be refused.

17 As the separate questions effectively determined a substantive right and the proposed grounds of appeal, when considered at a reasonably impressionistic level, were not plainly lacking any merit, it is appropriate for leave to appeal in terms of the notice of appeal dated 15 January 2021 to be granted. The appeal, however, should be dismissed.

Background

18 There is no dispute about the background facts.

19 Aerial images of Streaky Bay dated 2 March 1967 show the configuration of the golf course in 1967, which includes some portions of the land over which the State and the Wirangu respondent have agreed that native title has been extinguished. The remaining disputed parcels of land are shown enclosed within blue boundaries on the aerial photograph appearing at page 107 within annexure KDR2 to the affidavit of Kerin Dare Rain affirmed on 15 April 2020 (AB Pt C, 488) and is Annexure A to these appeal reasons.

20 Aerial photographs taken in 1967 show the existence of a nine-hole golf course encompassing both the undisputed parcels and the disputed parcels. The land has, at all times since 1967, been accessible to members of the public. Over time, the golf course has been reconfigured on several occasions including by relocating or reconfiguring holes, tee-off points, scrapes, mounds, bunkers and fairways and to establish a new fairway. Between 1975 and the early 1980s, the Sceale Bay Road, which passed through one of the fairways, was dug up using a grader or bulldozer and in-filled with top soil and grass was seeded. In the 1980s, the existing driveway to the club rooms was removed and a new driveway and large all-weather carpark was created. The entrance, club rooms and carpark, and a significant area surrounding those features, are located on an undisputed parcel (Reasons at [52], [55], [65], [81], [82]).

21 On 22 April 1975, the Club became an incorporated body under the Associations Incorporations Act 1956-1965 (SA) (Reasons at [50]). As at this date, the Club occupied the land comprising the golf course as a bare licencee, revokable at the will of the Council (Reasons at [119]).

22 From 1975, the management of the land was the responsibility of the Management Committee of the Council (a controlling body for the purposes of s 666C of the Local Government Act 1934 (SA) as then in force). The Management Committee included persons who were members of the Club (Reasons at [164]).

23 Under the controlling body model, the Council was liable for the acts and omissions of the Management Committee including in respect of the occupation and management of the land. This model existed until the repeal of s 666C in 1988 (Reasons at [164]).

24 The impetus for moving from a relationship of bare licencee to lessee was to reduce the Council’s exposure to liability for any personal injury that might arise on or in relation to land under its responsibility (Reasons at [166]).

25 Section 242 of the NTA defines a ‘lease’ to include:

(a) a lease enforceable in equity; or

(b) a contract that contains a statement to the effect that it is a lease; or

(c) anything that, at or before the time of its creation, is, for any purpose, by a law of the Commonwealth, a State or a Territory, declared to be or described as a lease.

26 A ‘community purposes lease’ is defined in s 249A of the NTA:

A community purposes lease is a lease that:

(a) permits the lessee to use the land or waters covered by the lease solely or primarily for community, religious, educational, charitable or sporting purposes; or

(b) contains a statement to the effect that it is solely or primarily a community purpose lease or that it is granted solely or primarily for community, religious, educational, charitable or sporting purposes.

27 It was common ground before the primary judge that the grant of a community purposes lease between 1 January 1994 and 23 December 1996 (if it occurred) would, by reason of s 232A(2) be a valid ‘intermediate period act’ and therefore an act that would extinguish native title, provided that the lease did not contain a reservation for the benefit of Aboriginal people (Reasons at [134]).

The earthworks question

28 There are 16 grounds of appeal in relation to the earthworks question.

Relevant legislative provisions for the earthworks question

29 The Council’s primary submission at trial was that the works establishing the golf course before 31 October 1975 (that is, before the enactment of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth)) validly extinguished native title at common law (Reasons at [26]). If so, their extinguishing effect at the time of construction or establishment was confirmed by s 36F of the NTA (SA). Alternatively, those works constructed or established after that date and before 1 January 1994 were said to be validated past acts attributable to the State under s 32 of the NTA (SA) which, as Category A past acts and previous exclusive possession acts, extinguished native title by operation of s 34 and s 36G of the NTA (SA) respectively (Reasons at [27]-[28]).

30 As the primary judge explained at [20] of her reasons, the Council advanced these alternative bases for the extinguishment of native title in respect of the whole of the golf course referable to earthworks. Nonetheless, each depended on the proposition that there had been a “public work”, as defined in the NTA and applied by the NTA (SA), which extinguished native title prior to 31 December 1993 (being the date put in issue by the Separate Question). So much was not in issue.

31 It is common ground that conduct which falls within the definition of “public work” in the NTA extinguishes native title: see, relevantly, s 23B(7) (previous exclusive possession acts), s 229(4) (category A past acts), and s 24JB(2) (future acts).

32 The phrase “public work” is defined in s 253 to mean (and not simply include):

(a) any of the following that is constructed or established by or on behalf of the Crown, or a local government body or other statutory authority of the Crown, in any of its capacities:

(i) a building, or other structure (including a memorial), that is a fixture; or

(ii) a road, railway or bridge; or

(iia) where the expression is used in or for the purposes of Division 2 or 2A of Part 2—a stock‑route; or

(iii) a well, or bore, for obtaining water; or

(iv) any major earthworks; or

(b) a building that is constructed with the authority of the Crown, other than on a lease.

33 By the use of the word “means”, and the purpose and context of the provisions, it appeared to be common ground that this definition is exhaustive (a proposition with which we agree).

34 The phrase “major earthworks” is defined in s 253 as follows:

major earthworks means earthworks (other than in the course of mining) whose construction causes major disturbance to the land, or to the bed or subsoil under waters.

35 We understand it is (correctly) common ground that this definition is also exhaustive.

251D Land or waters on which a public work is constructed, established or situated

In this Act, a reference to land or waters on which a public work is constructed, established or situated includes a reference to any adjacent land or waters the use of which is or was necessary for, or incidental to, the construction, establishment or operation of the work.

Summary of the primary judge’s reasons on the earthworks question

37 At [11], the primary judge expressed her conclusions on the earthworks contentions:

I am not satisfied that the applicant’s native title in the land was wholly extinguished by the construction of public works in the nature of major earthworks on the land on or before 31 December 1993.

38 At [26]-[28], the primary judge set out, in a way which is not impugned on the appeal, the various aspects of the Council’s contentions:

The Council’s principal submission was that the works for the establishment of the golf course were acts attributable to the State that were done prior to 31 October 1975, and that their extinguishing effect on native title was valid.

To the extent that the works occurred on or before 23 December 1996 (and hence before the date specified in the question before the Court), the works were said to be both valid and a “previous exclusive possession act” that completely extinguished native title from the date that the construction of the works began: NT Act, s 23B(7); State NT Act, s 36G.

Works occurring after 31 October 1975 and before 1 January 1994 were said to be validated past acts attributable to the State: NT Act, s 228; State NT Act, s 32. Validated past acts that consist of public works extinguish native title: NT Act, s 229(4); State NT Act s 34.

39 At [42], contrary to the Wirangu respondent’s submissions at trial, the primary judge noted that while most of the parcels which constituted the golf course were parcels where it was not disputed that native title had been extinguished, that extinguishment did not render those parcels irrelevant to the question before the Court. Her Honour gave two reasons: first, the parties’ various contentions “necessitate consideration to be given to the whole of the land on which the golf course is situated”. Second,

it is conceivable that works may be taken to have been situated on a disputed parcel by the operation of s 251D of the NT Act, even if the activities causing “major disturbance to the land” occurred on adjacent land falling within an undisputed parcel.

40 The development of the golf course is summarised in general at [20] of the appeal reasons, by reference to the primary judge’s findings. At [56]-[58], the primary judge made the following findings, again not impugned on the appeal, about the development of the golf course over time:

In 1967, as now, the vast majority of the golf course was comprised of the grassed areas that form the fairways (expanses of land cleared of vegetation) together with vegetated surrounds. In the aerial photographs, the area occupied by the club rooms is very small relative to the size of the golf course as a whole.

The Sceale Bay Road (and an area surrounding area it) as well as the club rooms, car park (and large areas surrounding them) are situated within the undisputed parcels. In other words they are areas in respect of which the applicant agrees native title was extinguished.

An aerial photograph taken in 1998 shows changes to some features of the golf course. Based on the evidence as a whole, I am satisfied that the photograph fairly represents the extent of the construction and establishment of the golf course as at 31 December 1993.

41 At [59]-[63], the primary judge then set out the evidence before the Court about what works were undertaken at which times, and the two key deponents of affidavits on behalf of the Council. These gentlemen, as her Honour points out, were not only key Council members, but key members of the Streaky Bay Golf Club and its committees.

The evidence does not establish to the requisite standard what (if any) works were carried out on the land in the period between 1967 and 30 October 1975. The evidence of works occurring between 1975 and 1994 is more specific. Two witnesses have deposed to events occurring in that period from their living memory. Whilst the beginning and end dates for the activities they describe are not in all cases specific, that lack of precision does not bear on the outcome, for reasons that will soon become apparent.

David Lane was the Chief Executive Officer (formerly titled District Clerk) of the Council from November 1985 until July 2003. He first began working for the Council in 1977. Mr Lane has also had a long association with the Club, serving for many years in the joint role of Secretary and Treasurer. He has played golf on the course since 1978 and was made a life member of the Club in 2003.

John Rumbelow was the Chief Executive Officer of the Council from 2003 to 2008. Between 1985 and 2003 he was the Deputy Chief Executive Officer (formerly Deputy District Clerk) under Mr Lane. Mr Rumbelow has played golf on the course since 1972. He, too, has been an office bearer of the Club and was made a life member in 2001.

On the basis of the evidence given by Mr Lane and Mr Rumbelow, I am satisfied that between 1975 and 1994 there were changes to the configuration of the course having the effect of relocating or reconfiguring some of its features such as holes, tee-off points, scrapes and fairways. The changes altered the configuration of the game, in which certain tee-off points, scrapes and fairways do double duty. Only one new fairway was established and other fairways changed shape. A new hole 3 was established and the remaining holes and fairways were renumbered.

Mr Lane’s evidence is brief. He does not remember specific details of any particular works conducted in that period although he does recall that the activities “involved major earthworks, and required permission to rip up and remove vegetation from some areas”. Whilst I accept that significant vegetation clearance (and also revegetation) occurred as the game configuration on the course changed, whether the works overall should be described as “major earthworks” within the meaning of the NT Act is for the Court to decide in accordance with the statutory definition. I give little weight to Mr Lane’s characterisation and make my own evaluation based on the underlying facts.

42 Between [65] and [82], the primary judge moves to a description of each of the public works said to have extinguished native title. In summary, these are the modification of Sceale Bay Road from a gravel road to becoming part of the golf course between 1975 and the early 1980s; the construction and removal of “mounds and bunkers”; the formation and removal of “scrapes” up until 1994; the formation of tee-off points, the formation and modification of fairways, and the reconfiguration of the entrance and car park for the golf course. In these passages her Honour made factual findings about the nature and extent of the works involved in each of these features of the golf course over the relevant time period. Some of these findings are impugned on the appeal and we return to them below where appropriate.

43 At this point, it should be clarified that the “scrapes” which her Honour describes are a form of (un-grassed) putting greens. At [67]-[69] her Honour describes them thus:

A scrape is a putting surface. It is formed by introducing and compacting imported base material on the earth’s surface to form a raised mound with a flat top, over which a fine layer of material is laid. The scrapes were initially constructed of silica sand and later from slag sourced from a lead smelter. More recently, the scrapes have been formed with creek sand. The top layer is now constituted of irrigated greens, although that improvement did not occur until after 1994.

I am satisfied that in 1994 there were 10 scrapes in play, whereas previously there had been 13.

Of the 10 scrapes in existence in 1994, most of them were situated on the disputed parcels.

44 The primary judge then turned to an issue about who carried out the various works. This matter is not an issue on the appeal and it suffices to note that at [89] the primary judge concluded that all works were carried out “on behalf of” the Council, for the purposes of the definition in s 253.

45 From [91] the primary judge turned to findings about what her Honour described as the Council’s “primary argument”; namely that the evidence disclosed there had been “major disturbance” to the land.

The primary argument advanced by the Council is that all of the works for the construction of the golf course are to be considered as a whole and that the works involved a major disturbance to the whole of the land in question. On that analysis, it was submitted, “major earthworks” are situated in fact on the whole of the land comprising the golf course without resort to s 251D of the NT Act. The alternative argument is that some elements of the works constituted major earthworks and that those works must be taken to be situated on the whole of the golf course by the deeming operation of s 251D.

46 In order to answer that question, the Court set out the existing authority on the meaning of “major disturbance”: [96]-[100]. Her Honour noted, contrary to some of the grounds that are sought to be put on the appeal, that while it was accepted that the Sceale Bay Road and the club house were public works because they are a road and a building (at [101]):

However, the Council did not suggest that the remainder of the 31 hectares of land on which the golf course is located should be considered as land upon which the road and club rooms must be taken to be situated because of the operation of s 251D of the NT Act. If I have misunderstood the Council’s position in that respect I would conclude that s 251D does not have that operation on the facts. It has not been submitted that the whole of the golf course was incidental to or necessary for the construction and use of the road or the club rooms, nor does the evidence establish any such proposition.

47 The primary judge’s interpretation and application of the definition of “major earthworks” is central to several proposed grounds of appeal. At [103]-[104] her Honour described her reasoning process:

It remains to determine whether the works for the establishment of the golf course caused a major disturbance to the land when considered as an integrated whole. In the analysis that follows I will focus first upon discrete features of the course (as that was the approach taken in the evidence and submissions), before analysing them together.

An important feature of the “major earthworks” definition is its focus on disturbance to the land itself, rather than upon the erection of fixtures or features upon or above the land’s surface per se. The disturbance must be “to the land”, and it must be “major”.

48 At [109] her Honour found:

In my view, it may reasonably be inferred that the works for the creation of the features of the golf course (and the later changes to those features) were subjectively intended to be indefinite at the time that they were undertaken. However, the fact that a significant number of features of the golf course were removed, relocated or altered from time to time is informative of the objective nature of the works and the degree to which they have impacted the land. The removal of mounds and scrapes is illustrative. Qualitatively speaking, the construction of scrapes and mounds involved the importation of fill for the purpose of raising the level of some parts of the ground to varying degrees. The evidence does not demonstrate that the construction of the mounds and scrapes involved disturbance of the land surface before fill (in the nature of imported slag or creek sand) was mounded upon it. Whilst the construction of those features no doubt involved the use of heavy machinery and the importation of fill, I am not satisfied that those activities constituted major earthworks when considered in the context of the golf course as a whole.

As Mansfield J said in Margarula, by reference to the Explanatory Memoranda, the “major earthworks” definition is intended to cover large scale earthworks such as damns and weirs which permanently (or at least indefinitely) disturb the land. The evidence shows that the mounds are not immovable from the earth’s surface and that they have in fact been removed or rebuilt in accordance with the Club’s desires to change the configuration of the game from time to time. As has been said, neither their construction nor their removal involved major disturbance to the land in the requisite sense.

In the result, I am not satisfied that the construction of any one particular feature of the golf course referred to in the evidence and occurring after 31 October 1975 and before 1 January 1994 constitutes a major earthwork when considered separately. Accordingly, it is unnecessary to determine whether s 251D of the NT Act would operate to deem land to be included in the place where each of those asserted public works is situated. Nor do I consider those features described in the affidavits to constitute a major earthwork when considered together in the context of the golf course as an integrated whole.

50 Based on these considerations, the primary judge answered the earthworks question “no” (at [118]).

Summary of the Council’s submissions on the earthworks question

51 In its submissions, except for the first ground, the Council grouped some of the 16 grounds of appeal together, and the Wirangu respondent responded similarly. It is convenient to summarise the submissions in that grouped way.

52 As to ground 1, the Council contended that the aerial images annexed to the affidavit of John Graham Rumbelow affirmed 18 May 2020 and filed in the proceeding below show that scrape 16 was clearly larger than 15 sq m, as her Honour found it to be at [70]-[71]. The Council contended:

The true size of the scrape (indeed all except 1/10 and 6/15) was much larger. This misapprehension of scale infected the Judge’s reasoning because her Honour thought scrape 16 to be “typical of most of the scrapes” other than the ‘Crows Nest’.

53 The Council grouped grounds 2, 3, 10 and 12 together. These grounds all relate to the interpretation and application of the “major earthworks” definition, and whether the primary judge erred by finding that major earthworks had not occurred in the disputed parcels.

54 The Council contended that the primary judge’s understanding of the concept of “major earthworks” as requiring “large scale earthworks such as damns and weirs which permanently (or at least indefinitely) disturb the land” (Reasons at [114]) was incorrect. That understanding is “contrary to the ordinary meaning of ‘earthworks’”, which the Council submitted includes the banking of earth or soil, not merely its excavation. The primary judge is said to have erred in her approach by focussing on the concept of disturbance to the surface or “wounding” of the land (being her Honour’s term).

55 In grounds 4-9, and 15, the Council submitted that the primary judge further erred in her selection of comparator in asking whether major earthworks had occurred. Instead, the appropriate comparison exercise was contended to be the following:

(i) accept that the mounds, scrapes and other filling of the land was itself ‘earthworks’; (ii) to compare the land pre-earthworks with the land post-earthworks; (iii) to undertake that comparison in the context of the township of Streaky Bay and its parklands; and thus determine whether there had been major disturbance to the land.

56 The comparison ought to have been between the golf course as at 1 January 1994 and the state of the land prior to 1929, or at sovereignty. The earthworks over that time did cause major disturbance to the land, and should be considered major earthworks. This “comparison” argument was also raised in support of grounds 10 and 12.

57 In addition:

(a) as to ground 4, the Council submitted that the creation of fairways constituted major earthworks, since they involved heavy machinery such as graders, front-end loaders, and combines. Large swathes of land were cleared of trees and given over to fairways;

(b) as to the works identified at grounds 5-8, being to create 13 and remove 3 scrapes, to create and remove “the various mounds shown in the aerial photographs in evidence”, various tee-off mounds, and various fairways, the Council submitted the primary judge erroneously concentrated on whether the works had disturbed the surface of the land, or possibly the sub-surface by means of compaction, instead of undertaking a “before and after” comparison of the landform, the “before” including times before the golf course existed, as well as at sovereignty. In oral submissions the Council contended that at sovereignty, it could be inferred from the aerial photographs showing retained vegetation areas that the entire area now covered by the golf course was covered in vegetation;

(c) as to ground 15, the tee-off number 2 and the scrape called the “Crows Nest” are both large, obvious alterations to the land that are indefinite in character. The latter was shown in a 1967 aerial photograph to have a “footprint” the size of a house. Each should have been found to be a major earthwork as they were conceptually no different to a farm dam (which the Council contended would constitute “major earthworks”); and

(d) as to ground 9, it was artificial to consider the “disputed” parcels of land separately to the “undisputed” parcels of land. The comparison exercised ought to have been a comparison of the whole of the works to create the golf course, and the state of the land before that time. The Council also made a general submission that the works to create the golf course over time were not genuinely considered cumulatively, as they should have been.

58 Grounds 11, 13, 14 and 16 are each grounds where it is contended that the primary judge erred by not applying s 251D of the NTA (as picked up and applied by the NTA (SA) as we explain at [128] below). The Council contended that given the primary judge’s findings that there were public works in the vicinity, the whole of the golf course should have been found to be land on which public works have been undertaken. The Council submitted that the primary judge accepted that Sceale Bay Road and the club rooms were each public works, and the construction of the car park was found by the primary judge to have involved a “major disturbance to the land” (at [102]). The Council equates the latter to a finding that the car park was a public work.

59 The Council contended that because the construction of Sceale Bay Road, and the operation of the club rooms and car park would have no utility without the golf course, by operation of s 251D the whole golf course is therefore land on which public works have been undertaken, because the balance of the golf course was land ‘necessary’ (or at least incidental to) the operation of the reintegrated land as a golf course.

60 The Council submitted that if the Full Court found error in the approach of the primary judge in any respect in relation to the earthworks questions, it was in as good a position as the primary judge and should decide the matters for itself.

Resolution

61 The Council’s earthworks grounds of appeal in some instances did no more than assert error without any corresponding contention of what the precise error was, or what the correct finding should have been. There was sometimes little further development in written or oral submissions and therefore the ground of appeal remained at the level of assertion. That is insufficient for the Council to discharge its burden of establishing error. Nevertheless, we will attempt to deal with each ground as it is expressed in the further amended notice of appeal, and to the extent each was developed in submissions. It is first necessary to deal with the correct approach to the definition of “major earthworks” in s 253, and also the correct approach to s 251D, as revealed by the authorities.

The correct approach to s 253 and the definition of “major earthworks”

62 The central thesis of the grounds of appeal concerning the earthworks is that the primary judge misunderstood the statutory concept of “major disturbance”, or misapplied it to the evidence.

63 Before turning to the authorities, it is necessary to note two features of the text of the relevant provisions. First, the expression chosen by the Parliament in the exhaustive definition of public works is “major earthworks”. It is not “all earthworks”, or “earthworks” without a qualifying adjective. It is not “major or minor earthworks”. The adjective “major” has been chosen and must be given effect: Commonwealth v Baume [1905] HCA 11; 2 CLR 405 at 141, applied in Wilkie v Commonwealth [2017] HCA 40; 263 CLR 487 at [146].

64 Next, the context of s 253 is that “any major earthworks” is one of a list of other activities which are prescribed to be public works. These include buildings, “other structures” that are fixtures; a road, railway or bridge and in some circumstances a stock-route; well, or bore. This context is emphasised in some of the authorities discussed below.

65 Of the definition of “major earthworks” the following textual matters should be noted. The definition focusses on “construction”. It is the construction of the earthworks which must, relevantly, cause a “major disturbance” to the land. As with the principal term, the use of the adjective “major” must be given effect. The same adjective is used in the principal term as in the definition, and this emphasises the legislative choice by Parliament to differentiate between the scale and impact of some works from others.

66 At a general level it might be supposed that, in the context of a legislative scheme designed to protect native title, in selecting and defining the activities which will extinguish native title by force of the operation of express provisions in the NTA, Parliament intended to select activities the carrying out of which were inconsistent with the continuation of native title rights in that land or waters. However, the legislative scheme has other objectives, and with the amendments following the decision in Wik Peoples v State of Queensland [1996] HCA 40; 187 CLR 1 in particular, one objective was the bringing of greater certainty about the effect of previous activities on the continuation of native title to land and waters. Thus, the activities which fall within provisions such as s 253 may, or may not, have extinguished native title at common law, but Parliament has made a legislative choice for the sake of certainty about which activities have that effect, and which do not. As two members of the Full Court in Anderson v Wilson [2000] FCA 394; 97 FCR 453 pointed out (at [27], per Black CJ and Sackville J):

There is no occasion in this case to consider the precise relationship between the rules embodied in the NTA governing “confirmation of past extinguishment of native title” and the general law principles of extinguishment of native title. It is enough to note that, despite the terminology employed in Pt 2, Div 2B of the NTA, the effect of Div 2B is not necessarily simply to confirm instances of extinguishment of native title that have already taken place under the general law. For example, it is possible that some of the leases, or classes of leases, specified in Sch 1 to the NTA (all of which, by virtue of s 23B(2), constitute “previous exclusive possession acts”) would be found, on general law principles, not to have completely extinguished native title. If that is so, the inclusion of these leases in Sch 1 simply reflects the fact that Parliament, in the interests of certainty, has chosen to interpret the general law differently from the courts. (Compare the effect of the recital to the preamble to the NTA which was said in Wik to have read too much into the judgments in Mabo (No 2): Wik at 125, per Toohey J.)

67 That said, the legislative choice having been made, each provision must be carefully construed and applied so as not to alter the balance reflected in the legislative choice between certainty and the protection of native title rights and interests. That is why, as always, the particular text matters.

68 Finally, some assistance on the intended meaning of the “major earthworks” aspect of the public works definition is provided in the Explanatory Memorandum (Part B) to the Native Title Bill 1993 (Cth) at [103]:

The definition of this term is intended to cover major or large scale works such as dams and weirs whose construction permanently and significantly disturbs or changes the land, or the bed or subsoil under waters. A work must be constructed to come within the definition. The term is referred to in the definition of ‘public works’.

(Emphasis added.)

69 The key authorities are Rubibi Community v State of Western Australia (No 7) [2006] FCA 459, Banjima People v Western Australia (No 2) [2013] FCA 868; 305 ALR 1 and Margarula v Northern Territory [2016] FCA 1018; 257 FCR 226. These were the three authorities considered by the primary judge and the parties did not submit her Honour had overlooked any critical authorities.

70 All three authorities make two propositions abundantly clear: the question is one of characterisation on the evidence, and the evidence and facts are critical.

71 In Rubibi, Merkel J looked at the earthworks definition in the context of a number of activities on the claimants’ land which were submitted to have extinguished native title. One of the guiding approaches his Honour took in making the factual findings he did was to ask “whether there was permanent disturbance and change to the land such that it was appropriate to characterise” an activity as a major earthwork: see for example [131].

72 An example of this was Merkel J’s reasoning about an uncompleted sports oval which was one of the works in dispute (at [132]):

McMahon Oval is area 135 (R41551). This reserve includes an uncompleted sports oval which covers approximately 40% of the reserve. The oval has never been used as an oval. There was uncontested evidence that, in the course of creating the oval, the Shire carried out earthworks and installed drainage ditches and paths. There was also evidence that the whole of the reserve was traversed and disturbed by heavy earthmoving equipment during the creation of the oval and drainage ditches. A water storage tank was installed in the northern corner of the reserve. I undertook a site visit to McMahon Oval. I am satisfied that creation of the oval was a major earthwork the construction of which involved usage of the whole of the reserve. It is therefore not necessary to consider whether the drain on the reserve was also a major earthwork, although it probably was not such a work.

73 It should also be noted that Merkel J undertook a view or inspection of all the works in dispute. That did not occur before the primary judge.

74 In Banjima at [1465], Barker J noted an element of circularity in the definition of “major earthworks”, and expressed the view that the adjective “major” in the phrase “major disturbance” (and we infer, also in the statutory term itself) means “something prominent or significant in size, amount or degree”. His Honour also referred to various dictionary definitions of the adjective “major”. At [1467], his Honour referred to considerations of proportionality and context, comparing the construction of a gravel pit somewhere like Kings Park, Perth, with the same construction in “a vast area of remote country near a gravel road”. As has been explained above, the adjective must be given work to do, and that is the point Barker J also makes at [1468]:

While, obviously a gravel pit of the type described in Ex 68 by Mr Armstrong no doubt involves disturbance to the land, I do not consider it constitutes a “major” disturbance of the land.

75 We respectfully agree with his Honour’s approach.

76 Margarula appears to be the latest relevant authority. Relevantly in that case, Mansfield J was considering a dispute over two previous activities, in terms of whether they constituted “major earthworks” for the definitions of “public work”. One was a go-kart track and pedestrian underpass; the other the Magela Creek sewage pipeline.

77 As to the go-kart track, his Honour relied on specific affidavit evidence about the construction of the track, including that it had been “surfaced with bitumen to a high standard with additional kerb edge protection in certain areas”, and found at [348]

the process of “levelling the area, forming contours, and provision for stormwater run off to perimeter drains” for a 250 x 200 m track can be and should be characterised as “major disturbance to the land”.

78 At [348], Mansfield J made the same point that has been made earlier in these reasons, and was made by Barker J in Banjima:

The word “major” cannot be said to qualify the word “disturbance” with any degree of precision. However, the qualification of “disturbance” by the word “major” must mean that not just any disturbance will be sufficient. If any disturbance at all would be sufficient to satisfy the definition, then the word “major” would be otiose. In addition, the word “major” must require rather something more akin to “significant”, and sensibly attracting that description.

79 Having considered the extrinsic material, to which we have referred above, Mansfield J concluded at [349] that

in the overall context it is also sensible generally to require a disturbance which has permanently and significantly disturbed or changed the land.

80 After referring to Rubibi, Mansfield J noted at [352] that there was “obviously an element of judgment required” in making findings about whether construction or activities were major earthworks, and had resulted in major disturbance to the land or waters concerned. His Honour concluded:

The go-cart track is sealed and contoured, with perimeter drainage works, and as installed has an adjacent surfaced car parking area. It occupies a significant space. It has, clearly, elements or features which indicate that it is intended to exist indefinitely.

81 As a contrasting example, Mansfield J found the Magela Creek pipeline was not a major earthwork. His Honour’s reasoning at [356] is with respect instructive, and illustrates that size in itself – in terms of the area of land covered – may not necessarily be indicative of major disturbance:

While the trench dug was two kilometres long, and required about a five metre clearing width, it is only one metre deep. It has been covered. Apart from the removal of trees, I do not think that this pipeline falls within the definition of a major earthwork. The disturbance to the land whilst permanent in the sense that the pipeline lies within it, is not substantial. The digging of the trench did not cause a permanent disturbance to the land. The excavation was substantial but its residual effects are small. Again, it is a matter of judgment on all the material. In this instance, I do not characterise that disturbance as a significant one, and conclude that the Magela Creek sewage pipeline is not a “major earthwork”.

Section 251D

82 The Council advanced a construction of s 251D which would give it a sweeping operation. That construction should be rejected. Section 251D is facilitative: it is intended to ensure that where there are public works, they can be carried out, or the products of the public works effectively used, without interaction with native title rights and interests.

83 That is, if the public work itself has extinguished native title but land or waters adjacent to it are still subject to native title, the purpose of the extinguishing provisions could be compromised. Sundberg J recognised this in Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402 at [659]:

Section 251D is specifically directed to public works, and is plainly intended to operate in conjunction with ss 23B(7) and 23C(2). There is no reason to deny its beneficial function of ensuring that a public work has the benefit of adjacent land that is necessary for or incidental to the operation of the work, especially in relation to access to landlocked works.

(Emphasis added.)

84 His Honour’s example aptly illustrates the confined operation of the provision. So too what was said by Mansfield J in the trial judgment in Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakay Native Title Claim Group v Northern Territory of Australia [2004] FCA 472; 207 ALR 539 at [299]:

If those works are valid public works, s 251D of the NT Act has the effect that the areas of land upon which those roads and infrastructure are constructed or established or situated are taken to include adjacent land the use of which is or was necessary for, or incidental to their construction, establishment or operation. In the case of the roads, the necessary area is said to include a corridor, the physical extent of which is dictated by what is necessary to service and maintain them. In the case of the infrastructure, the necessary area is said to include the hard stands upon which the works are located.

(Emphasis added.)

85 In Banjima at [1452], Barker J also adopted an approach of asking whether access over other land was “necessary” for access to the public work. Another matter to note from Barker J’s judgment at [1453]-[1456] is that insufficient evidence led his Honour to reject evidence of those contending for extinguishment about the size of the area to which s 252D should be found to apply, in respect of three water bores. His Honour stated at [1456]:

In the circumstances I would not find extinguishment in respect of water bores in respect of an area as great as 1 ha (which in old imperial measure is about 2.46 acres), when a water bore itself covers an area of only 1 square metre. In that regard I note that Mr Armstrong does not specify 1 ha without qualification, but says that an area of “about 1ha” is required.

86 That led his Honour, in a pragmatic way, to decide at [1457] that “some allowance” for access should be made, at 0.10 ha.

87 A further example from Banjima is the approach taken to a tourist information bay along the State Highway to Karijini National Park. Contrary to the submissions of the native title applicant in that decision, Barker J found (at [1470]-[1474]) that this area was to be regarded as part of the public work that was the highway itself by reason of s 251D, because it was “adjacent to the roads and serves motorists and so is included in the operation of the roads”.

88 One matter which should be referred to from Mansfield J’s reasons in Margarula on the application of s 251D is what his Honour says at [363] about land adjacent to a townhouse complex which was accepted to be a public work, where the Northern Territory relied on the existence of what it submitted was a “shared park/garden area” visible on a satellite map. Mansfield J found:

In my view, the satellite map alone does not constitute proof of all these things. It demonstrates that lot 871 is indeed “bounded and isolated” together with lot 872 by roads on all sides. But that is not the definition of an “adjacent land”. The appearance of lot 871 on the satellite map is also consistent with a characterisation of it as a “shared park/garden area”. But its appearance could also be consistent with a host of other uses. There is insufficient evidence to conclude that it is an “adjacent land” to the public work on lot 872.

89 The point of referring to this example is as an illustration, no more, of the operation of the burden of proof in these circumstances, and the need for the Court to be persuaded by the nature of the evidence before it. Satellite maps, like aerial maps in the current proceeding may or may not be sufficient proof of the elements of s 251D.

90 The Council did not challenge the primary judge’s treatment of these authorities, but rather her Honour’s application of them to the evidence. We have spent some time on the authorities to demonstrate that her Honour did not err in her application of the approach required by the definition of “major earthworks”, nor by the operation of s 251D as picked up and applied by the NTA (SA). We turn to explain why this is so by reference to the grounds of appeal.

The 16 grounds of appeal

91 We do not consider that any of the 16 grounds of appeal should be upheld.

Ground 1

92 This ground challenges a single aspect of the primary judge’s fact finding, at [71] of the reasons, about one scrape (scrape 16). Paragraph [71] states:

A photograph of the scrape at hole 16 looking back over the fairway depicts an elevated area with a fairway behind it. The surface area of the elevation is not specified in the evidence. It appears to be a circular shape of approximately 15 square metres. The height of the elevation does not appear to be more than 60 cm. In the absence of evidence to the contrary it is reasonable to infer that the scrape at hole 16 is typical of most of the other scrapes.

93 The Council submits the “uncontested evidence” about the size of this scrape is found in the affidavit of Mr Rumbelow filed 11 June 2020, [3] and annexures JGR-3 and JGR-4.

94 Paragraph [3] simply refers to annexures JGR-3 and 4, and deposes they are photographic images of the golf course from 1967 and 1998 respectively, which he has annotated. In other words, Mr Rumblelow gives no direct evidence himself about the size of scrape 16, and these photographs contain images of many scrapes on the course. The two images have no scale measure attached to them.

95 Scrape 16 is highlighted on the far right hand side of JGR-3. On the face of photograph, the red circle signifying scrape 16 is smaller than some of the other red circles, signifying other scrapes. Whereas on JGR-4, all or most of the red circles appear on the face of the photograph to be of approximately the same size.

96 Again, on the face of the photograph, all of the scrapes appear smaller in size than the houses which can also be seen on the photograph.

97 No probative basis in the evidence before the primary judge has been provided by the Council upon which this Court could identify error in the primary judge’s factual finding about size. Her Honour was much more familiar with all the evidence than this Court. This Court was taken to nothing more than selected aerial photographs. At base, the Council asks the Court to speculate about size of scrape 16 and whether it was “typical”, and that is not appropriate. The most that can be said is that a visual inspection of the two annexures confirms her Honour’s assessment of scrape 16 as being “typical” in size, aside from the Crows Nest scrape, appears correct.

98 Ground 1 is not made out.

Grounds 2, 3, 10 and 12

99 These grounds challenge the primary judge’s findings at [104], [109]-[111], and [112]-[114].

100 There is no error in the primary judge’s findings at [104], where her Honour said:

An important feature of the “major earthworks” definition is its focus on disturbance to the land itself, rather than upon the erection of fixtures or features upon or above the land’s surface per se. The disturbance must be “to the land”, and it must be “major”.

(Original emphasis)

101 That is an approach consistent with the authorities we have explained above. That the disturbance must be “to the land” is apparent from the text of the definition itself – “whose construction causes major disturbance to the land” (the second part – “or to the bed or subsoil under waters” not being in issue in the trial). We have explained above the importance of the word “major” and the primary judge was, with respect, correct to emphasise this.

102 At [109]-[111], the primary judge dealt with the evidence about how some of the features on the golf course (such as mounds and scrapes were made), and how they were altered:

In my view, it may reasonably be inferred that the works for the creation of the features of the golf course (and the later changes to those features) were subjectively intended to be indefinite at the time that they were undertaken. However, the fact that a significant number of features of the golf course were removed, relocated or altered from time to time is informative of the objective nature of the works and the degree to which they have impacted the land. The removal of mounds and scrapes is illustrative. Qualitatively speaking, the construction of scrapes and mounds involved the importation of fill for the purpose of raising the level of some parts of the ground to varying degrees. The evidence does not demonstrate that the construction of the mounds and scrapes involved disturbance of the land surface before fill (in the nature of imported slag or creek sand) was mounded upon it. Whilst the construction of those features no doubt involved the use of heavy machinery and the importation of fill, I am not satisfied that those activities constituted major earthworks when considered in the context of the golf course as a whole.

Whilst Mr Lane and Mr Rumbelow both referred to features of that kind being removed or replaced, it was not suggested that the land below the compacted mounds was significantly “disturbed” such as to require remedial works of any significance to be done to the underlying land when the man-made elevations were taken away. There is no evidence of remedial works in fact being undertaken so as to rehabilitate the land formerly covered by relocated scrapes or mounds, and it does not appear from the evidence that any such remedial work was required in fact. In my view, upon the removal of features of that kind, the land below was in its original state, as it had always been.

It is conceivable that the construction of mounds and scrapes may have caused some compaction in the underlying land, but there is insufficient evidence to support a finding that the compaction was “major” in its effect. I would draw that conclusion no matter what the height of each scrape.

103 These passages are responsive to, and accepting of, a submission made on behalf of the Wirangu respondent at trial, recorded at [108] of her Honour’s reasons, where the Wirangu respondent submitted that the activities undertaken on and relating to the golf course did not fall within the concept of “major disturbance” and instead were the “modification and adaption of the parklands to allow golf to be played”, occurring “in an evolutionary way over a number of decades”. The Wirangu respondent submitted there was no evidence they were intended to be permanent.

104 As the authorities indicate, the permanency of the changes made to land is capable of being an indicator of whether or not construction has “caused major disturbance”. Her Honour was, with respect, correct to consider this factor, and the evidence plainly bore out a finding that the constructed features of the golf course had changed over time, but had done so largely by moving soil around on top of the land, rather than excavating under the land. The absence of significant excavations under the land was also capable of being an indicator of no major disturbance. These were matters for her Honour on the evidence and no error has been demonstrated.

105 The primary judge’s findings at [112]-[114] were:

The impact of the scrapes, tee-off points and mounds may also be considered having regard to the size of the footprint occupied by them relative to the surface area of the golf course as a whole. In the context of an area totalling 31 hectares, the areas on which the tee-off points and scrapes are situated are very small indeed. That is not to lose sight of the importance of considering the golf course as a singular “work”, but if the scrapes and tee-off points are to be regarded as the most serious of all of the wounds on the land, I consider them to be few and far between.

Two mounded features require specific attention: the tee-off point and the scrape described earlier in these reasons at [74] and [70] respectively. Each of those features is significant in height relative to the usual height of the surface of the land. As has been said, the tee-off point is accessed by players using stairs to reach it. Notwithstanding their size relative to the other mounded features, I do not consider these features to be significant when considered in the context of the land as a whole and I do not consider the works for the construction of those two features to constitute major earthworks when considered both qualitatively and quantitatively.

As Mansfield J said in Margarula, by reference to the Explanatory Memoranda, the “major earthworks” definition is intended to cover large scale earthworks such as damns and weirs which permanently (or at least indefinitely) disturb the land. The evidence shows that the mounds are not immovable from the earth’s surface and that they have in fact been removed or rebuilt in accordance with the Club’s desires to change the configuration of the game from time to time. As has been said, neither their construction nor their removal involved major disturbance to the land in the requisite sense.

106 It is not correct to understand what the primary judge says in these passages, or the earlier ones extracted in this section as “excluding” the filling of land, or fixtures, from the definition of “major earthworks” (ground 2). Rather, the primary judge describes, correctly with respect, the “focus” of the definition as disturbance to land. Similarly, in considering the evidence that most of the mounds, scrapes and tee-off points were constructed using fill from elsewhere piled on the existing surface of the land, the primary judge was entitled to consider this as a factor weighing in her assessment of whether the construction of these features “caused” major disturbance to the land. The causal factor in the definition should not be overlooked and her Honour did not overlook it.

107 Likewise, contrary to the contention contained in ground 3, the primary judge did not construe the word “land” in the definition of “major earthworks” as meaning only subsurface and soil. Rather, the primary judge focussed on the whole of the definition – construction causing major disturbance – and in this context focussed on the nature and extent of the changes brought about by the creation of mounds, scrapes and tees, noting the absence of much if any disturbance to the surface and subsoil. There was no error in this approach.

108 Grounds 10 and 12 deal with the kind of comparison used by the primary judge in assessing whether the activities fell within the definition of major earthworks. In submissions, these grounds were developed by reference to what might be called a “comparator” argument: see [55]-[56]. There appear to be two different kinds of comparisons the Council submits the primary judge should have undertaken, but did not. The first was a comparison of how the entire golf course (not just the disputed parcels) appeared at or prior to sovereignty, with how it appeared by 1 January 1994: see ground 10. The second was a scale-based comparison – namely, that the primary judge should have compared the “size and scale of the golf course” with its townscape surrounds, or the size and scale of the fairways, scrapes, tee-offs, and mounds with the townscape surrounds; or the “size and scale of the fairways, scrapes, tee-offs, and mounds compared with the cadastral parcel in which they were situated”. It can be seen that some of these alternatives are mutually inconsistent with each other, as to what the correct comparison was (assuming one had to be made, which in the terms put we do not accept).

109 These grounds are not expressed to involve s 251D.

110 As to the first kind of comparison, the simple answer to this contention is that there was not sufficient evidence before the primary judge to make such a comparison, even if the primary judge was expressly invited by the Council to do so, which is not apparent from the reasons. However, counsel for the Council and the State confirmed during the appeal hearing that this submission was put, and was also put by the State. The submissions of the Wirangu respondent on this issue should be accepted. Mr Lane’s affidavit evidence (in his 17 May 2020 affidavit) was at the most general level – he deposed that vegetation was removed from some areas without saying where and if any of that activity occurred on the disputed parcels, and that other areas were rehabilitated. He deposed (unsurprisingly, as a witness for the Council) that what occurred were “major earthworks”, an assertion which carried no real probative value in the context of a statutory definition.

111 The submissions of the Council at [14]-[15] of its reply should be rejected, as should the submissions to similar effect made orally. The Council bore the burden of proof that a public work on the disputed parcel, consisting of major earthworks, had extinguished native title. For it to contend that there is no real evidence about how the land appeared at sovereignty and therefore the requisite degree of “disturbance” can somehow be assumed, or that the Court can speculate there was the requisite degree of disturbance “caused to the land”, must be rejected. Counsel’s attempt in oral submissions to persuade the Court, by reference to aerial photographs in evidence, that all of the land was covered in dense vegetation, should be rejected. Apart from anything else, the somewhat poor quality aerial photographs to which the Court was taken do not themselves enable any findings about the nature and density of the remaining vegetation on which counsel relied. The findings of Mansfield J in Margarula about the use of photographs might here be recalled. Beyond this, there is no probative basis for any inference to be drawn from the evidence to which the Court was taken about the extent of vegetation coverage at sovereignty. Even if such an inference were to be drawn, the removal of some vegetation to create fairways does not inescapably amount to a “major disturbance to the land” caused by the construction of the fairways. That was clear from many aspects of the primary judge’s reasoning and we respectfully agree. This contention gives the word “major” no work at all to do. It also gives the concept of construction “causing” major disturbance no real work to do.

112 As to the second kind of comparison, the primary judge well appreciated the need to consider the effect of the construction of fairways, mounds, scrapes and tees in the overall context of the golf course as a whole, recalling that the issue before the primary judge was not whether native title was extinguished by major earthworks over the whole of the golf course, but rather whether it was extinguished by major earthworks over the disputed parcels, being only certain parts of the golf course. The principal focus was on the disputed parcels and whether the construction of a public work on those parcels extinguished native title, subject of course to the operation of s 251D. Some of the Council’s submissions on these grounds invited quite the wrong approach to the question before the primary judge, which was a parcel-by-parcel exercise. The “context” – recalling for example the observations of Barker J in Banjima – might require regard to be had to the wider landscape effects so as to understand the proportionality and context in order to decide if the disturbance is properly described as “major”, but her Honour’s reasons demonstrate she was alive to this issue, for example by findings such as those at [112] – “[t]hat is not to lose sight of the importance of considering the golf course as a singular work”.

113 Grounds 2, 3, 10 and 12 are not made out.

Grounds 4-9 and 15

114 All these grounds as expressed in the notice of appeal suffer from the flaw of simply asserting error in a factual conclusion by the primary judge, without identifying why the finding was erroneous.

115 It is correct, as the Council submits, that at [76]-[79] of the primary judge’s reasons, her Honour summarises the evidence about how the golf course was constructed (and therefore, we infer, how the construction on the disputed parcels occurred):

A fairway is created by using a grader to clear the surface of the ground so that grass may grow over the cleared area. The shapes of the fairways are depicted in both the 1967 and 1998 photographs. I am satisfied that immediately prior to 1994, the vast majority of the land constituting the golf course was dedicated to fairways which, for the most part, were cleared of vegetation.

Mr Lane recalls that front-end loaders and seeding combines were used to till the ground and to mass-plant grass seeds along the fairways, including (and especially) at the time that the Sceale Bay Road was removed.

It is otherwise reasonable to infer from the aerial photographs that the creation of a new fairway and the reshaping of other fairways involved the removal of vegetation and the seeding of grass.

116 Thus, it can be taken (and the Council did not contend otherwise) that the primary judge correctly understood the evidence about the machinery used in the construction and alteration of fairways, mounds, scrapes and tees.

117 In addition to the passages in the primary judge’s reasons which were also impugned by the previous group of appeal grounds, the primary judge’s reasoning at [105]-[106] was also impugned by these grounds and should be set out: