FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Allergan Australia Pty Ltd v Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 163

ORDERS

JAGOT, LEE AND THAWLEY JJ | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondents be granted leave to rely upon the amended notice of contention filed on 27 August 2021.

2. The appeal be allowed.

3. Order 7 of the orders made on 7 December 2020 be set aside and in lieu thereof it be ordered that the cross-claim be dismissed.

4. The proceedings be remitted to the primary judge for determination of:

(a) damages or an account of profits for infringement of the BOTOX Mark pursuant to s 126(1)(b) of the TM Act;

(b) additional damages under s 126(2) of the TM Act;

(c) damages under s 236 of the ACL; and

(d) any account or inquiry as to damages or profits as may be necessary.

5. The parties confer with a view to confirming within 7 days the form of declarations and injunctions proposed in the reasons for judgment or providing to the Court agreed declarations and injunctions or, failing agreement, competing versions thereof together with submissions of no longer than 2 pages in support.

6. The respondents pay the appellants’ costs of the appeal as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 249 of 2021 | ||

BETWEEN: | ALLERGAN AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 000 612 831) First Appellant ALLERGAN INC Second Appellant | |

AND: | SELF CARE IP HOLDINGS PTY LTD (ACN 134 308 151) First Respondent SELF CARE CORPORATION PTY LTD (ACN 132 213 113) Second Respondent | |

order made by: | JAGOT, LEE AND THAWLEY JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 September 2021 |

1. Orders 1 and 2 made on 5 March 2021 in proceedings NSD15/2017 be set aside.

2. The question of the costs of the hearing below be remitted to the primary judge.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

INTRODUCTION

1 Botox is an injectable product containing botulinum toxin type A. Allergan Inc is the manufacturer of Botox and the owner of various trade marks for BOTOX, including the word mark BOTOX, being Trade Mark No 1578426 (BOTOX Mark) in various classes including class 3 which includes “anti-ageing creams; anti-wrinkle cream”. Botox is used for both therapeutic and cosmetic purposes. It is a well known product.

2 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd and Self Care Corporation Pty Ltd (together Self Care) supply cosmetic products, including topical anti-wrinkle skincare products under the trade mark FREEZEFRAME.

3 Allergan Inc and its subsidiary, Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (together Allergan), brought proceedings in this Court against Self Care and Ms Sonia Amoroso, who was at the relevant times the sole director and secretary of Self Care IP and Self Care Corporation.

4 In the first proceedings (NSD15/2017):

(1) Allergan claimed that Self Care had infringed various of the Botox trade marks, including the BOTOX Mark. Allergan contended that the infringement arose through the use by Self Care of the word Botox in various ways on its packaging and in its promotion and advertising of its FREEZEFRAME products. The proceedings concerned a number of products referred to as: Inhibox, Protox, Night (tube version), Night (tub version) and Boost. Of particular relevance to the appeal, Allergan claimed that Self Care used:

(a) the brand name PROTOX as a trade mark, that PROTOX was deceptively similar to the BOTOX Mark, and that use of the name PROTOX as a trade mark constituted an infringement under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TM Act) of the BOTOX Mark; and

(b) the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” as a trade mark and that Self Care’s use of the phrase also constituted an infringement of the BOTOX Mark.

The primary judge dismissed both of these aspects of the proceedings by orders made on 7 December 2020: Allergan Australia Pty Ltd v Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1530; (2020) 156 IPR 413 (the primary judgment).

(2) Allergan brought claims under the Australian Consumer Law, being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL) alleging Self Care had made misleading or false representations concerning its affiliation with Allergan and the efficacy of its products. Again, these claims concerned multiple products. The primary judge concluded that only 1 of about 35 statements in contention formed part of conduct in contravention of the ACL and dismissed the remaining claims. The successful claim was based on the statement that the Night (tube version) produced equivalent results in four weeks to those which Botox would achieve.

(3) Allergan made claims for passing off and for alleged contraventions of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth). These claims were all dismissed.

(4) Allergan made claims for accessorial liability on the part of Ms Amoroso in respect of various of the claims summarised above. These were each dismissed.

5 In the second proceedings (NSD1802/2017), Allergan Inc appealed from a decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks to allow Self Care IP’s Trade Mark Application No 1653383 for the words FREEZEFRAME PROTOX to proceed to registration in respect of goods in class 3 (anti-aging serum and anti-wrinkle serum). Before the primary judge, Allergan Inc raised ss 42(b), 44, 58, 59, 60 and 62A of the TM Act as grounds of opposition. Self Care contended that each of the grounds on which Allergan opposed registration should be rejected, including because its trade mark was not deceptively similar to the word BOTOX. The primary judge dismissed these proceedings and, as discussed below, the trade mark has since proceeded to registration.

6 On 5 March 2021, the primary judge made an order in the first proceedings (NSD15/2017) that Allergan pay 90% of Self Care’s party and party costs in the proceedings and in proceedings NSD1802/2017. His Honour made an order on the same day in proceedings NSD1802/2017 that the costs of those proceedings be costs in proceedings NSD15/2017: Allergan Australia Pty Ltd v Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 185 (the costs judgment).

7 Allergan brings two appeals in respect of the first proceedings only, NSD15/2017. Allergan’s second appeal (NSD249/2021) is from the orders flowing from the costs judgment. The success or otherwise of that appeal depends upon Allergan’s first appeal (NSD35/2021) which concerns confined aspects of the primary judgment. In respect of the primary judgment, Allergan relies on seven grounds of appeal, covering three areas of dispute:

(1) The first concerns Self Care’s use of the word “PROTOX”. Grounds 1 to 3 relate to this area of dispute.

(2) The second concerns Self Care’s use of the words “instant Botox® alternative”. Grounds 4 and 5 relate to this area of dispute.

(3) The third concerns whether Self Care’s use of the words “instant Botox® alternative” resulted in contraventions of the ACL. Grounds 6 and 7 relate to this area of dispute.

8 It follows from the confined nature of the appeal that the majority of the conclusions reached by the primary judge are not challenged. In those circumstances, it is neither necessary nor desirable to repeat the factual background in detail. They are comprehensively set out in the primary judgment (hereafter “J”). The facts are repeated only to the extent necessary to explain the conclusions in respect of the three limited areas of dispute on appeal.

FIRST AREA OF DISPUTE

Introduction

9 The first area of dispute concerns Self Care’s use of the word “PROTOX”. Allergan contends that the primary judge should have found that PROTOX so nearly resembled BOTOX that it was likely to deceive or cause confusion: Ground 3. Grounds 1 and 2 are subsidiary complaints in the sense that infringement under s 120(1) of the TM Act would be established if Ground 3 succeeds whether or not Grounds 1 and 2 are made out.

10 Ground 1 was to the effect that the primary judge erred in: (a) treating the word “Botox” as a generic name for anti-wrinkle injections; and (b) consequentially concluding that Self Care’s use of PROTOX did not demonstrate an intention to appropriate the reputation of the BOTOX brand. Ground 2 contended that the primary judge should have: (a) found that Self Care and Ms Amoroso intended to leverage off the BOTOX mark; and (b) consequentially applied the “rule” in Australian Woollen Mills Limited v F S Walton and Company Limited [1937] HCA 51; (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 657 to treat that intention as evidence that the marks were deceptively similar.

11 Also relevant to the first area of dispute is Self Care’s notice of contention to the effect that it was FREEZEFRAME PROTOX which was used as a trade mark, not the word PROTOX alone. It is convenient to deal first with the notice of contention.

The notice of contention: PROTOX or FREEZEFRAME PROTOX?

12 The primary judge did not accept that PROTOX was almost always used in combination with FREEZEFRAME, but accepted it was usually used in combination with FREEZEFRAME; even then “the spatial relationship between those words [was] not consistent”: at J[191].

13 On the packaging for the Protox product, the word “PROTOX” is used separately from the word “freezeframe®” as shown at J[63] (reproduced in part at [17] below). Further, pages from the Freezeframe website depicted the PROTOX name and mark being used independently of FREEZEFRAME, including in banner headings: at J[196]. Some advertisements referred to the product as “FREEZEFRAME PROTOX” others as “PROTOX” on its own and also in combination with “PROTOX freezeframe” and “freezeframe PROTOX” and also “PROTOX by freezeframe”: at J[195], [197]. The primary judge concluded it was “quite clear that PROTOX is used as a trade mark”: J[198]. This conclusion at J[198] is challenged by Self Care’s notice of contention.

14 Self Care relied in particular upon Colorado Group Limited v Strandbags Group Pty Limited [2007] FCAFC 184; (2007) 164 FCR 506. The word “Colorado” had been nearly always used with a multiple peak mountain device: Colorado at [95]-[103]; [110]. It was held that the word “Colorado” could not be said to have been used alone to show origin, but was rather part of a composite mark with the device: at [110]. The device was held to be part of the trade mark use which, unlike the word “Colarado” on its own, had the capacity to distinguish: Colorado at [29], [40], [41], [110], [128].

15 Self Care also relied upon P B Foods Ltd v Malanda Dairy Foods Ltd [1999] FCA 1602; (1999) 47 IPR 47, referred to by Allsop J in Colorado at [109]. P B Foods concerned the use of CHOC CHILL in relation to flavoured milk. Carr J considered that it was the word CHILL that was doing the work of denoting the trade origin of the goods and that the word CHOC was not distinctive; rather, it was descriptive of flavour.

16 Whilst the reasoning process leading to the conclusions in other cases can provide guidance, each case turns on its particular facts. It should be observed that the present case is not one in which the question involves whether a word is being used separately or only in combination with a device, like Colorado; nor is this a case involving two words, one of which is merely descriptive, like P B Foods.

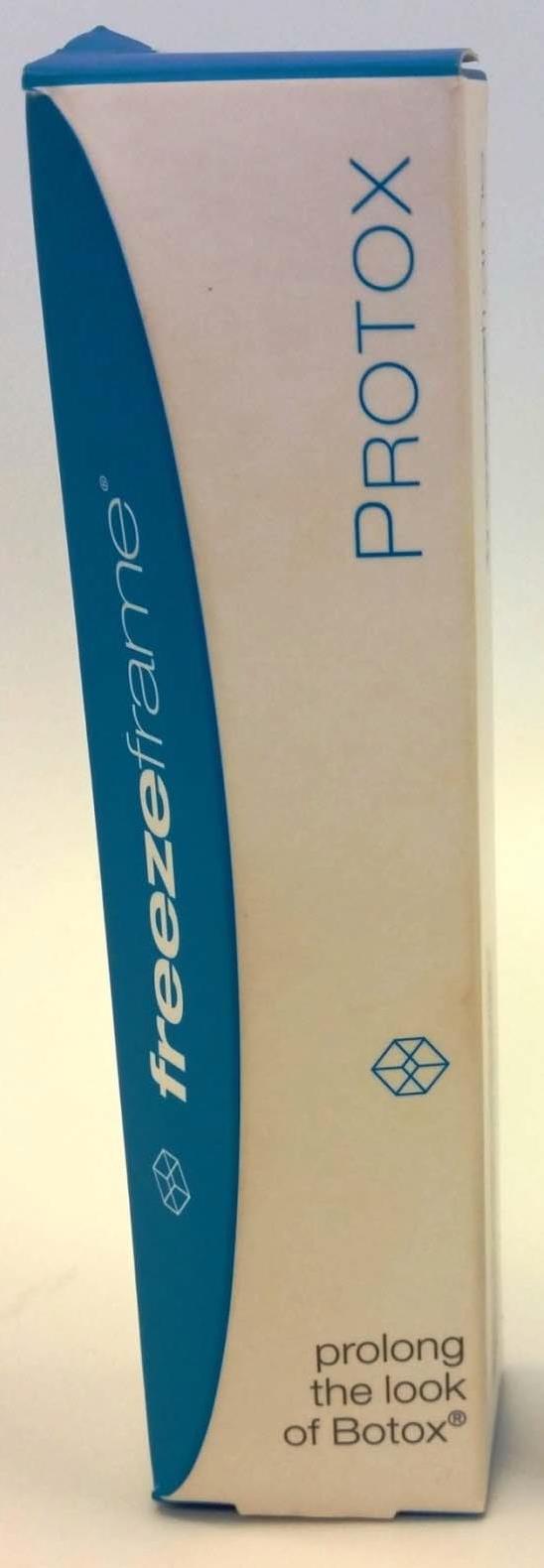

17 An example of the Protox packaging in the present case is as follows:

|

|

18 In this packaging, PROTOX and FREEZEFRAME are both used as independent trade marks and not as a composite mark FREEZEFRAME PROTOX. This conclusion follows from an assessment of the packaging as a whole, including the words themselves. The FREEZEFRAME mark (used in relation to multiple products) is isolated to the blue “surfboard” part of the packaging, separating it structurally and spatially from the PROTOX mark as something distinct. The fonts used for the two words are different. “PROTOX” is in capital letters and “freezeframe®” is in lower case. The ® symbol is very small. The word “freezeframe®” is in two colours; the word “PROTOX” is in one. The background colours on which the two words appear are different. The physical structure of the box itself serves to differentiate the two words. Both marks in the present case serve a function of denoting the trade origin of the goods. Both words convey allusions or hint at potential meanings, but neither is directly descriptive. The primary judge was correct to conclude that PROTOX was used as a trade mark and that it was used independently of FREEZEFRAME.

Are PROTOX and BOTOX deceptively similar?

19 Allergan claimed that Self Care, in using the sign PROTOX as a trade mark, infringed the BOTOX Mark under s 120(1) of the TM Act. Section 120(1) provides:

Part 12—Infringement of trade marks

120 When is a registered trade mark infringed?

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

Note 1: For registered trade mark see section 6.

Note 2: For deceptively similar see section 10.

Note 3: In addition, the regulations may provide for the effect of a protected international trade mark: see Part 17A.

20 Section 120(1) refers to substantial identity and deceptive similarity. These are independent criteria: The Shell Company of Australia Limited v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Limited [1963] HCA 66; (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414 (Windeyer J). The appellants’ case was confined to deceptive similarity: J[166].

21 That term “deceptively similar” is the subject of s 10 of the TM Act. Section 10 sets out the circumstances in which “a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar”. It provides:

10 Definition of deceptively similar

For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

22 The definition (in the form of a deeming provision) is directed to whether one mark “so nearly resembles” another that the former is “likely to deceive or cause confusion”. The statutory context makes it clear that the topic about which marks should not deceive or cause confusion is ultimately the source of the products to which the mark relates. Section 17 of the TM Act provides:

A trade mark is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

23 An application for the registration of a trade mark must be rejected if the trade mark is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered: s 41(1).

24 Deceptive similarity raises, as a central question, whether there is a real risk that the consequence of use of the allegedly infringing mark would result in persons being caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the products in respect of which the mark is used come from the same source as products the subject of the mark said to be infringed: Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd [1954] HCA 82; (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 608 (Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Webb, Fullagar and Taylor JJ); Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd [1999] FCA 1020; (1999) 93 FCR 365 at [50] (French J, with whom Tamberlin J agreed); The Coca-Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (t/as Millers Distributing Company) [1999] FCA 1721; (1999) 96 FCR 107 (Black CJ, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ) at [39]; Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235; (2020) 385 ALR 514 (Nicholas, Yates and Burley JJ) at [66].

25 Deceptive similarity is not determined by a “side-by-side” comparison of the two marks of the kind undertaken in determining whether the marks are substantially identical. Rather, it is determined by considering the impression that would be left with ordinary persons seeing the marks. In Shell at 415, a case which involved alleged infringement through advertising films exhibited during television broadcasts, Windeyer J explained:

The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from [viewing the allegedly infringing mark].

26 It is relevant to consider the circumstances in which the goods would be acquired and the character of the probable acquirers of the goods. In Australian Woollen Mills at 658-659, Dixon and McTiernan JJ explained:

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of the potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. The effect of spoken description must be considered. If a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods, then similarities both of sound and of meaning may play an important part. The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard. Evidence of actual cases of deception, if forthcoming, is of great weight.

…

It depends on a combination of visual impression and judicial estimation of the effect likely to be produced in the course of the ordinary conduct of affairs.

27 The primary judge set out the relevant principles concerning deceptive similarity from J[164] to J[172]. His Honour dealt with the application of those principles to the facts, so far as concerned PROTOX and BOTOX, at J[204] to J[211].

28 In the section addressing the applicable principles (J[164] to J[172]), the primary judge did not refer to the fact that the confusion to which the relevant provisions were directed was confusion as to the source of the products as opposed to confusion between the marks or products themselves.

29 In the section of the primary judgment applying the principles to the facts (J[204] to J[211]), there is no reference to the question whether there might be confusion as to trade source as opposed to confusion between the marks or products themselves. The conclusion to the analysis at J[204] to [211] was expressed in the following way at J[211]:

The result is that although the marks are undoubtedly very similar in look and sound, they are sufficiently distinctive that, in my view, persons of ordinary intelligence and memory are not likely to confuse them. The PROTOX mark does not so nearly resemble the BOTOX mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion. Put differently, in my view, a person with even an imperfect recollection of the BOTOX mark is not likely to be deceived by the PROTOX mark, or even the general impression left by that mark; there is no real, tangible danger of that occurring. There is also no evidence of actual confusion, which offers some support to that conclusion.

30 When the primary judge’s articulation of the principles from J[164] to J[172] is read with the application of those principles from J[204] to J[211], it cannot safely be concluded that the primary judge asked himself or answered the question whether the two marks so nearly resemble each other that people might be confused as to whether the products to which they relate might come from the same source. His Honour only asked and answered the question whether people would confuse the marks PROTOX and BOTOX or the products to which those marks related. There is no analysis or reference in the primary judgment to whether consumers, understanding that the products are different, might wonder whether they came from the same source. It should be accepted that ordinary people would not confuse the names PROTOX and BOTOX or the underlying products. However, of itself, that conclusion does not answer the question whether there is a risk that people might think the different products come from the same source.

31 Self Care submitted that the primary judge did not err in the way contended by Allergan. It submitted that it should be inferred, notwithstanding the absence of a direct reference to the issue, that the primary judge asked and answered the correct question. As to the identification of principle, Self Care pointed to J[169], where the primary judge referred to Southern Cross at 608 in the context of summarising the level or risk of confusion which needed to be established. The primary judge stated:

It is sufficient if persons who only know one of the marks and have perhaps an imperfect recollection of it are likely to be deceived: Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd [1952] HCA 15; 86 CLR 536 at 538 per Dixon, Williams and Kitto JJ. A mere possibility of confusion is not enough; there must be a real, tangible danger of its occurring: Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd [1954] HCA 82; 91 CLR 592 at 595 per Kitto J (adopted on appeal at 608 per Dixon CJ, McTiernan, Webb, Fullagar and Taylor JJ).

32 Self Care correctly observed that the Full Court in Southern Cross at 608, in addition to approving what Kitto J had said at trial about the necessary level of risk of confusion, stated that it was confusion about source which was relevant. Self Care submitted that it should therefore be inferred that the primary judge had that principle in mind when stating his conclusions as to the application of the principles to the facts at J[211]. That submission must be rejected. The primary judge’s reference at J[169] to Southern Cross was directed only to the degree of confusion required, not what the confusion must be about. Read fairly, the primary judge was stating at J[211] that people would not confuse PROTOX and BOTOX, either the mark or the product. One cannot properly infer in the convoluted way suggested that the primary judge asked or answered the question whether there was a real risk that people would be caused to wonder whether BOTOX and PROTOX came from the same source.

33 The appellants have established error and this Court must re-examine the evidence to form its own conclusion: PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 128 at [98]-[99], citing Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 and Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1835; (2001) 117 FCR 424. Proper regard should be had to the primary judge’s conclusions to the extent the findings are not shown to be erroneous.

34 The respondents submitted that the primary judge’s conclusion at J[211] was based on three key considerations, each of which was said to be consistent with authority:

(1) First, the primary judge considered that the words are distinguished by their first syllable, PRO- and BO-, and that attention would more likely be directed to the first syllable: J[207].

(2) Secondly, the primary judge observed that the prefix “pro” is a familiar and recognisable element of words and carries a meaning, whereas “bo” is not familiar and has no recognisable meaning: J[206], [207].

(3) Thirdly, the primary judge considered that the word “botox” is so well known that the difference between that word and the mark PROTOX would be immediately apparent.

35 All of this may be accepted, but is directed to the question whether a consumer would confuse the BOTOX and PROTOX marks, not whether consumers might wonder, in light of the similarities between the marks and given the nature of the products in respect of which the BOTOX Mark and other Botox marks are registered, whether the marks or underlying products came from the same source.

36 The primary judge concluded at J[209] that a consumer, on seeing or hearing PROTOX, is likely to be reminded of BOTOX. His Honour stated:

An important factor, in my assessment, is the ubiquitous reputation of BOTOX. As I have found, the word is very widely known, and to such a degree that it has become in ordinary usage a common noun, not only a proper noun. Thus, and within the authority of CA Henschke and Australian Meat referred to above (at [180]-[182]), and as in Mars Australia Pty Ltd v Sweet Rewards Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 606; 81 IPR 354 at [97] per Perram J, the fame of the mark is such as to impact on a consumer’s imperfect recollection of the mark. First, there is not likely to be an imperfect recollection of the mark and, second, even if there is, such a consumer is not on seeing or hearing PROTOX likely to mistake it for BOTOX; they are more likely to be reminded of BOTOX.

37 Relevantly to the observation at J[209] (and Ground 1 of the appeal) that the word Botox “has become in ordinary usage a common noun, not only a proper noun”, the primary judge concluded that the word Botox was understood in a generic sense as referring to an anti-wrinkle injection, whether or not being Allergan’s product; it could refer to any botulinum toxin product (being an injection) on the market: at J[153]. His Honour accepted the evidence of Ms Amoroso that people refer to “having Botox” even when they are having a different brand of botulinum toxin injection: at J[56]. His Honour also stated at J[56] that “BOTOX is to a significant degree like marks such as HOOVER, XEROX or BAND-AID which have gained use to describe a whole category of product rather than specifically a particular brand within the category”. It is important to note in respect of these observations that no case of “genericide” under s 24 of the TM Act was either pleaded or run. That is, it was not contended that the word Botox had become “generally accepted within the relevant trade as the sign that describes or is the name of an article, substance or service” such that the exclusive rights to use the mark had come to an end. There was no independent trade evidence adduced.

38 Relevantly to the observation at J[209] (and Ground 2 of the appeal) that the word PROTOX was likely to remind people of BOTOX, the primary judge had earlier concluded that Ms Amoroso had chosen names like PROTOX because of the closeness of the name to the BOTOX Mark: at J[71]. He considered that “the intention was obviously to leverage off” the fame of the BOTOX Mark and that consumers in the target market would “get” that inference: at J[73]. As noted earlier, Allergan submitted that these conclusions should have lead the primary judge to apply the “rule” in Australian Woollen Mills at 657 in which Dixon and McTiernan JJ said:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive. Moreover, he can blame no one but himself, even if the conclusion be mistaken that his trade mark or the get-up of his goods will confuse and mislead the public. But the practical application of the principle may sometimes be attended with difficulty.

39 The “rule” was held by the Full Court in Hashtag Burgers to have been engaged on the trial judge’s findings in that case that there was an intention to capitalise on reputation and cause confusion: Hashtag Burgers at [101]. Although the trial judge had concluded that the intention was dishonest, dishonesty was not necessary for the “rule” to apply: Hashtag Burgers at [104].

40 In the present case, the primary judge concluded that there was an intention to capitalise on BOTOX’s reputation, but there was no finding that there was an intention to deceive or cause confusion about the origin of the products. There is no implicit finding by the primary judge, or sufficiently reliable inference available on appeal in the absence of direct cross-examination on the topic, to the effect that Ms Amoroso intended to cause confusion as to source. In any event, the issue can be answered without reference to Ms Amoroso’s subjective intention or motivations being treated as expert evidence. The “rule” in Australian Woollen Mills is not one of inflexible application. It reflects a process of reasoning, the appropriateness of which depends on the particular facts, as does the weight to be given to the conclusion reached through application of that process of reasoning. The primary judge is not shown to have erred in failing to apply the “rule” in the circumstances of this case.

41 The primary judge correctly concluded that the word PROTOX would have reminded consumers of BOTOX: J[209]. That is why the word was chosen, as the primary judge found: J[71] to [73]. Consumers would not have confused PROTOX for BOTOX. The words are sufficiently different for consumers to appreciate that the words are different and that the products to which the words relate are different. That is reinforced by the context in which the consumer would come to see the words PROTOX and BOTOX. PROTOX was generally sold online and in pharmacies and such like, was topical rather than injectable, and was significantly cheaper than BOTOX. BOTOX was available through professional medical channels, via injection, and at significantly higher cost than PROTOX. However, that does not mean that consumers would not have wondered whether the different products, both intended to treat the appearance of wrinkles, came from the same source.

42 PROTOX so nearly resembles BOTOX that there is a real risk that PROTOX would deceive or cause confusion as to whether the two might come from the same source. As the primary judge found, most consumers on seeing PROTOX on an anti-wrinkle cream would immediately have been reminded about BOTOX. Consumers would not confuse the words PROTOX with BOTOX because the words are sufficiently distinct for the two not to be confused. As both parties accepted, this is not a case in which the words might have been confused because of faulty memory. However, the similarities between the two words would naturally have led consumers to wonder if perhaps the underlying products came from the same source. The similarities in the words imply an association.

43 Some consumers are likely (in the sense of a real and tangible danger or risk) to have wondered whether PROTOX was an alternative product being offered by those behind BOTOX, perhaps targeted to those who did not like injections or who wanted the convenience of a home treatment. Some consumers are likely to have wondered whether PROTOX was developed by those behind BOTOX as a topical treatment to be used in conjunction with Botox treatment, perhaps to improve or prolong results. Self care submitted in this regard that there was no evidence of any seller of botulinum toxin products also selling in the market for anti-wrinkle creams and that, therefore, consumers would not have wondered about an association between PROTOX and BOTOX. One difficulty with this submission is that it assumes a degree of knowledge on the part of consumers which is unlikely. A second difficulty is that, even if most consumers did have such an intricate knowledge of the relevant market or markets, it is likely that consumers would wonder whether those behind BOTOX had decided to expand into topical cosmetic anti-wrinkle products.

44 PROTOX is deceptively similar to BOTOX for the purposes of s 10 of the TM Act.

SECOND AREA OF DISPUTE

45 The second area of dispute concerns Self Care’s use, in a variety of ways, of the words “instant Botox® alternative”. Allergan contends that the primary judge should have found that:

(1) Self Care’s use of the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” on product packaging and in relation to the sale and promotion of its Inhibox product constituted trade mark use for the purpose of assessing infringement: Ground 4.

(2) the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” so nearly resembled BOTOX that it was likely to deceive or cause confusion: Ground 5.

46 It should be observed that Grounds 1 and 2 have a relevance to Ground 5 in the same way as those grounds are relevant to Ground 3. Ground 1 has been addressed at [37] above and Ground 2 at [38] to [40].

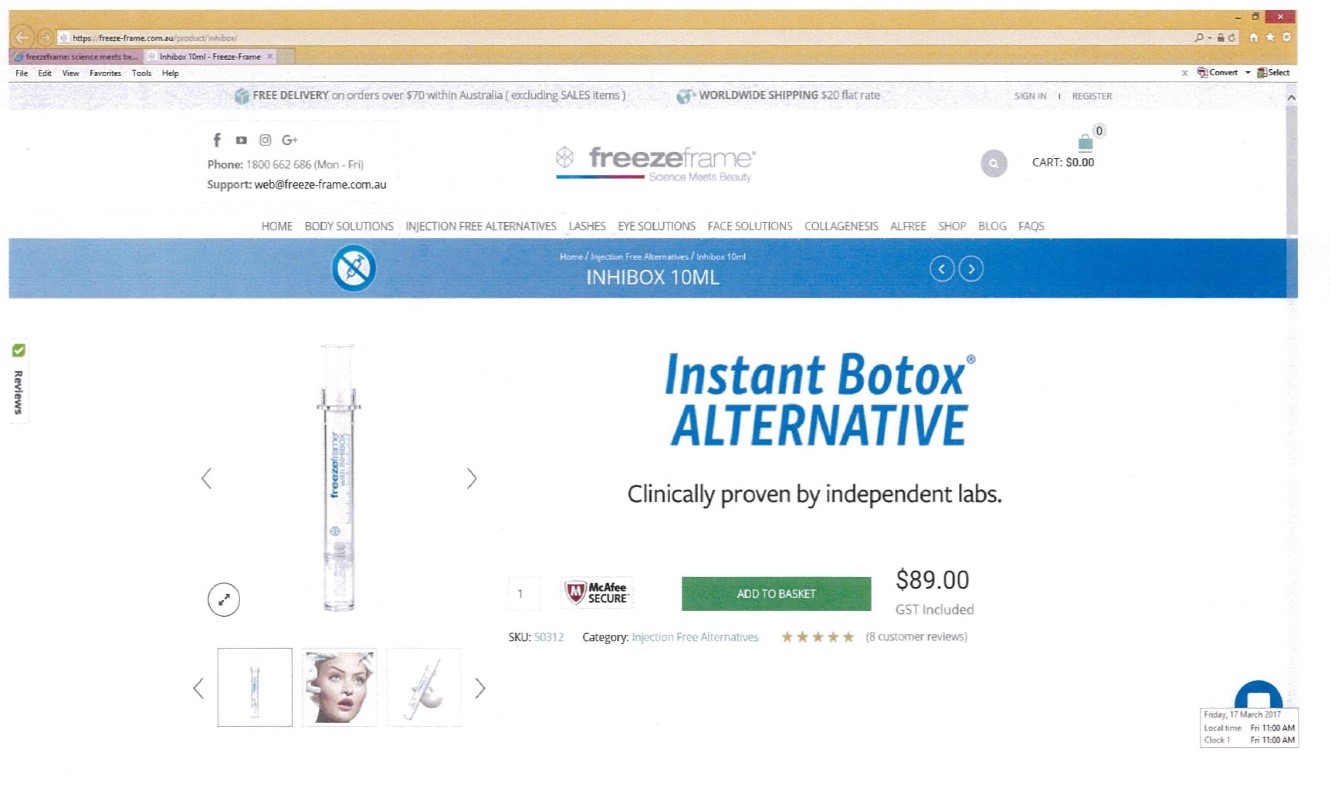

47 As mentioned, the second area of dispute concerns Self Care’s uses of the words “instant Botox® alternative” on product packaging and sales and promotion of Self Care’s Inhibox product. An example of two sides of the packaging (current at the time of trial) is as follows:

48 The phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was also used in a week-long promotion of Self Care’s Inhibox product in a large Myer department store and in advertising and promotion on the Freezeframe website – see: J[237], [238]. An example of the phrase being used in relation to the Inhibox product on the Freezeframe website is as follows:

Was use of the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” trade mark use?

49 In order to establish infringement under s 120(1) the use of the allegedly infringing mark must be use “as a trade mark”. The primary judge concluded that the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was not so used. This conclusion was reached in the context of numerous different phrases used on numerous different products, none of which uses the primary judge considered were uses as a trade mark. The primary judge observed that many of the phrases said to be used as trade marks were “narrative or descriptive phrases that include within them badges of origin such as PROTOX, FREEZEFRAME and BOTOX”: at J[231]. The primary judge stated at J[234]:

The only phrases that cause some hesitation with regard to whether or not they can themselves amount to trade marks or be used as trade marks are those without verbs such as “the accidental Botox Alternative”, “Instant BOTOX® alternative”, “Overnight Botox® alternative” and “Long term BOTOX® Alternative”. These phrases have the quality of being sufficiently short and catchy such as to possibly amount to labels for products and as such serve to distinguish them.

50 Notwithstanding that the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was sufficiently “short and catchy” as to potentially qualify as a mark capable of use as a trade mark, the primary judge concluded it was not used as a trade mark for four reasons.

51 The first aspect of the primary judge’s reasoning revolved around the word “alternative” in the phrase “instant Botox® alternative”. The primary judge stated at J[163] and J[249], [250]:

[163] The decision of the House of Lords in Irving’s Yeast-Vite Ltd v Horsenail (1934) 51 RPC 110 is particularly pertinent in the present context. Irving complained that Horsenail infringed its YEAST-VITE trade mark by using the phrase “Yeast Tablets, a substitute for Yeast-Vite” in relation to the product. It was held that the impugned use was to distinguish the products from each other: “It is not a use of the word as a trade mark, that is, to indicate the origin of the goods in the Respondent by virtue of manufacture, selection, certification, dealing with or offering for sale” (at 115 per Lord Tomlin).

…

[249] The Yeast-Vite case, discussed above at [163] above, is a good illustration of why Self Care’s use of the BOTOX mark does not constitute use of it as a trade mark. There, the one product was described as a “substitute” of the other. Describing one product as an “alternative” to another is not materially different. It serves to emphasise that the one is not the other. That was not use as a trade mark.

[250] Thus, BOTOX is not used by Self Care as its own badge of origin, i.e., indicating that the product identified by that name originates from Self Care. Indeed, the opposite is true.

52 The second matter referred to by the primary judge was the use of the ® (registered trade mark) symbol adjacent to the word Botox. His Honour stated that, “where that is done, [it] acknowledges that BOTOX is a badge of origin for the well-known product of that name”: at J[251]. His Honour noted that it was expressly recorded on the relevant packaging or in the relevant marketing material that BOTOX was a registered trade mark of Allergan Inc, making it “particularly clear that Botox is not Self Care’s product”.

53 Thirdly, the primary judge noted that Self Care’s products are branded and marketed under the umbrella brand FREEZEFRAME: at J[252]. The primary judge noted that, whilst there were differences in the spatial relationship, each product generally contained the product name and the umbrella brand. His Honour then stated at J[253]:

The result is that one is left with the impression that each product has two prominent brands with which it is associated, the umbrella brand and the product name – the latter sometimes reflected as “freezeframe [PRODUCT]” and other times only as the product name. The descriptive phrases that are also used in relation to the products, such as those that are complained of, have less prominence and serve less to identify the products and do not as a consequence tend to badge or brand the products.

54 The conclusion in the final sentence is a general one which the primary judge considered applied to each of the phrases including the single one challenged on appeal.

55 The fourth matter referred to by the primary judge draws on the first two matters referred to above. At J[254], the primary judge stated:

Fourth, Self Care’s use of the BOTOX mark does not indicate a connection in the course of trade between Self Care and BOTOX. It does the opposite. By describing Self Care’s products as alternatives or enhancers, comparing and contrasting, attaching the ® symbol and citing Allergan as the owner of that registered trade mark – as identified above – the point is made that there is no connection in the course of trade between BOTOX and Self Care.

56 It is the first matter which was the predominant reason for the primary judge’s conclusion that the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was not being used as a trade mark. The respondents submitted that the primary judge adopted the ordinary meaning of the word “alternative” and correctly concluded that, by use of the word, Self Care was indicating that its product was different to Botox. It was submitted that the word “alternative” dispelled any possible conclusion that there was an association or approval.

57 This submission cannot be accepted. The word “alternative” merely describes something as another possibility or choice. Self Care’s argument that “alternative” necessarily implies differentiation, accepted by the primary judge, is only helpful if one also identifies what is differentiated. The word “alternative” implies that the products are different, and there is a choice between them, but it does not necessarily imply that the trade source is different. Given the similarities in the words PROTOX and BOTOX, the labelling of PROTOX as “instant Botox® alternative” implies an association in the trade source of the different products. The inferences which might be drawn from use of a word such as “alternative” or “substitute” (Yeast-Vite) depends on context and there may well be more than one available inference to draw. Describing a product as an “alternative” to another product does not, of itself, say anything about who is offering the choice. The primary judge did not address whether he considered the use of the word “alternative” implied that the different products were not connected to the same source; rather, his Honour concluded that the word implied that the products were different. The latter implication must be accepted, but it is not clear that a single source would not be offering two product alternatives. The use of the word “alternative” does not necessarily negative use as a trade mark.

58 Yeast-Vite, upon which the primary judge relied, was distinguished by a majority of the High Court in Mark Foy’s Ltd v Davies Coop & Co Ltd [1956] HCA 51; (1956) 95 CLR 190. The plaintiff and appellant, Mark Foy’s, had registered the words “tub happy” in respect of articles of clothing. Its frocks, for example, bore labels stating “Tub Happy Cottons by Mark Foy’s Limited, Sydney”. The defendants had begun promoting their products with the words:

Exacto Cotton Garments – Tub Happy Cotton Fresh Budget Wise

59 Allowing the appeal and concluding that “Tub Happy” was used as a trade mark, Williams J (with whom Dixon CJ agreed) stated at 205:

The public are not being invited to compare the “Exacto” goods of the defendants with the “Tub Happy” goods of the plaintiff. They are being invited to purchase goods of the defendants which are to be distinguished from the goods of other traders partly because they are described as “Tub Happy” goods.

60 Kitto J would have dismissed the appeal on the basis that the words “Tub Happy” were disqualified from being registrable as a trade mark because they directly refer to the character or quality of the goods – cf: s 16(1)(d) of the Trade Marks Act 1905 (Cth). Kitto J did not express a view about whether, if the words were validly registered as a trade mark, the use of the words by the defendants was use as a trade mark.

61 The expression in Yeast-Vite was:

Yeast Tablets, a substitute for Yeast-Vite

62 Lord Tomlin described the use as being “to indicate the Appellant’s preparation and to distinguish the Respondent’s preparation from it”: at 115. That conclusion was one which flowed from the sentence structure and context in which the word “substitute” was used.

63 The primary judge correctly concluded that the word “alternative” in the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” indicated that the Inhibox product was not Botox, but that does not lead to the result that the phrase was not being used as a trade mark.

64 The critical question is whether the phrase as a whole was used as a trade mark. This involves an assessment of the phrase in the context and way in which it was used.

65 The evidence established that results from treatment by injection of Botox typically took a number of days. The phrase “instant Botox® alternative” might reasonably be understood to refer to a product in the Botox range which works instantly. It might reasonably be understood to refer to an alternative form of Botox, for example, a form of Botox that works instantly or a form of Botox applied as a cream as an alternative to being injected. Whilst the words “instant” and “alternative” are descriptive, the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was not being used in a purely descriptive way to distinguish Self Care’s products from Allergan’s products; rather, the phrase was being used to denote some trade source connection with those products, albeit the product was not Botox.

66 An example of the packaging and an online advertisement have been set out above. In the packaging, the words “INHIBOX” and “freezeframe” are plainly used as trade marks. The phrase “instant Botox® alternative” would not be read as being purely descriptive of the product. It is also difficult to conclude that the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” is being used to distinguish Inhibox from Botox in a manner equivalent to the situation in Yeast-Vite. Rather the packaging suggests the use of three trade marks: FREEZEFRAME, INHIBOX and INSTANT BOTOX® ALTERNATIVE. There is nothing unusual in the use of multiple marks, such as EXACTO and TUB HAPPY in Mark Foy’s; see also: Anheuser Busch v Budejovicky Budvar Narodni Podnik [2002] FCA 390; (2002) 56 IPR 182 at [191]; Nature’s Blend Pty Ltd v Nestlé Australia Ltd [2010] FCAFC 117; (2010) 272 ALR 487 at [40].

67 As to the second matter referred to by the primary judge, it is true that a close examination of the packaging would have revealed that BOTOX was a registered trade mark of Allergan Inc. In context, however, the use of the ® symbol, and the reference to BOTOX being the registered trade mark of Allergan Inc, does not lead to the conclusion either that there was no implied association with Allergan Inc or that the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was not being used to denote product origin. Even the meticulous consumer who searched the packaging to find out that BOTOX was a registered trade mark of Allergan Inc might reasonably consider there was an association. Such a consumer, noting that Inhibox was Self Care’s product and aware that Self Care was not Allergan Inc, might reasonably think that Self Care must have some form of authorisation or licence to use Allergan Inc’s trade mark or that there was some other association between Self Care and Allergan Inc. Indeed, the typical consumer might reasonably wonder whether, or think that, Self Care and Allergan Inc were related corporations in light of the packaging, in particular the reference to Allergan Inc and Botox®.

68 The third and fourth matters referred to by the primary judge have been addressed in what has been said earlier.

69 In the online advertisement the use of the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” as a trade mark is perhaps even clearer given the prominence given to the words in comparison to the use of the word “INHIBOX” and “freezeframe”.

70 The phrase “instant Botox® alternative”, on the packaging and in the website advertising, was being used to identify the product and to distinguish it from those of other traders. That is use as a trade mark.

Was “INSTANT BOTOX® ALTERNATIVE” deceptively similar to BOTOX?

71 The primary judge’s statement of the relevant legal principles at J[164] to J[172], in relation to whether PROTOX was deceptively similar to BOTOX, applied equally to his Honour’s consideration of this issue. The primary judge considered the marks were not deceptively similar, stating:

[256] Fairly obviously, the phrases are not in any way similar to the BOTOX marks. For all the reasons already given with regard to why those phrases are not used as trade marks, they cannot be mistaken for any of the BOTOX marks – they serve principally to compare, contrast and distinguish the product to which they are affixed from the product traded under the BOTOX marks that is named Botox. There simply is no deceptive similarity.

[257] That conclusion includes the use of the phrase “Instant Botox® Alternative” in respect of its use in the in-store promotion in Myer discussed above. There is nothing about the phrase that might cause it to be confused with any of the BOTOX marks, aside from the fact that it includes the word BOTOX within it. However, the use of “alternative” serves the function of demonstrating that it is not the same as, or linked to, but is quite different from, the BOTOX marks and thus their origin. Indeed, the point of the promotion, and its central message, was to distinguish the product in question from Botox.

72 Although not free from doubt, it would seem that his Honour approached the issue as being whether “instant Botox® alternative” could be mistaken for Botox rather than asking whether a consumer would be caused to wonder whether the products come from the same source. The doubt just referred to is raised by the fact that his Honour referred at J[257] to “origin”. However, a fair reading of the reasons indicates that his Honour approached the matter by asking himself whether a consumer would appreciate that the products were different, and then assuming on this basis that (rather than addressing or answering whether) there was not a real risk that the consumer would be caused to wonder if the two products came from the same source. The reasons do not address why the mere understanding that the products are known to be different necessarily results in a conclusion that one would not wonder whether the two products come from the same source. It follows that sufficient error has been demonstrated.

73 The question of whether the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” is deceptively similar to BOTOX involves a comparison of the impression ordinary people would have of the two marks: Shell at 415. The word “Botox®” is the most distinctive and memorable word in the phrase “instant Botox® alternative”. It is the “dominant cognitive cue”: Accor Australia & New Zealand Hospitality Pty Ltd v Liv Pty Ltd [2017[ FCAFC 56; (2017) 345 ALR 205 at [206]; Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imagin Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; (2017) 251 FCR 379 at [51]. The dominant cognitive cue in the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” is effectively identical to BOTOX.

74 The words “instant” and “alternative” in the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” are descriptive. As noted earlier, the word “alternative” implies that the product is different to Botox, but it does not necessarily imply that the products are not associated or that they do not come from the same or an associated source. The word “instant” implies that the product works faster than Botox, that is, that the product will deliver results faster than treatment by Botox injection. The use of these descriptive words around the dominant word “Botox®” make the phrase less similar to BOTOX, but there is a real risk that use of the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” would cause people to wonder whether the different products come from the same source.

75 Some of the matters referred to at [65] to [67] above are also relevant. Consumers may reasonably have wondered whether the product was a new BOTOX product, being a cream which, unlike the injection, brings “instant” results. In this regard, the primary judge concluded at J[334] that, if the BOTOX mark “was applied to a topical cosmetic product … it is likely that ordinary reasonable consumers would draw a connection between the product and the owner of the trade mark BOTOX; it is not likely that ordinary reasonable consumers would consider that the topical cosmetic product is in fact an anti-wrinkle injection; nor is it likely that ordinary reasonable consumers would conclude that the product had a different trade source because it was not an injectable”. There is no challenge to that conclusion.

76 In light of all of these matters, and accepting that the matter is one of impression about which differing views can be reached, the preferable view is that the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” so nearly resembles BOTOX that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion within the meaning of s 10 of the TM Act.

THIRD AREA OF DISPUTE

77 As noted earlier, the third area of dispute concerns claims for contravention of the ACL. Allergan contends that the statement “instant Botox® alternative” as used with respect to Self Care’s Inhibox product constituted a representation that the Inhibox product would give results to the same standard, or of the same quality, as Botox products in contravention of s 18 or s 29(1)(a) of the ACL or that Inhibox would achieve or had the same performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits as Botox in contravention of s 18 or 29(1)(g): Ground 6.

78 Ground 7 contains an alternative case to the effect that the primary judge should have found that Self Care did not have reasonable grounds for representing that Inhibox achieved a similar outcome to Botox in terms of the extent or longevity of Inhibox’s effectiveness with respect to the appearance of wrinkles.

79 By [29D] of its Second Further Amended Statement of Claim (2FASOC), Allergan pleaded that the INHIBOX product and packaging contained the following statements:

the front face of the INHIBOX packaging contained the words in a prominent position on the box “Instant Botox® Alternative”;

the back of the INHIBOX packaging contained the words in a prominent position “The World’s first Instant and Long Term Botox® Alternative”;

since August 2017, the words: “The original instant and long term Botox® alternative”

80 Allergan also pleaded, at 2FASOC [29E], that Self Care had advertised, promoted and sold or offered for sale the Inhibox products from the Freezeframe website, by reference to the following statements:

“CLINICALLY PROVEN, INSTANT BOTOX® ALTERNATIVE, FREEZES WRINKLES INSTANTLY, REDUCES WRINKLES LONG TERM”;

“Freezeframe with INHIBOX is the original Instant Botox® Alternative, clinically proven to erase wrinkle appearance under the eyes and on the forehead in just 5 minutes, whilst delivering up to 63.23% reduction in visible wrinkles in just 28 days”;

“… a topical alternative to Botox® injections …”;

“The original Instant Botox® Alternative, freezeframe INHIBOX has been a number 1 seller all over the world”.

81 The allegations in 2FASOC 29[D] and 29[E] were, subject to certain qualifications, admitted in Self Care’s Third Further Amended Defence (TFAD).

82 On 18 February 2019, Self Care gave undertakings not to make certain statements and it declined to give undertakings with respect to others. By reference to this undertaking, Allergan pleaded in 2FASOC [29EA]:

29EA From at least 4 March 2019, Self Care IP and Self Care Corporation have threatened or intend to advertise, promote, sell or offer for sale or authorise the advertising, promotion, sale or offer for sale of the Inhibox Products in Australia and for export under or by reference to the following statements

(a) “Instant Botox® Alternative”

(b) “The World’s first Instant Botox® Alternative”,

(c) “The original instant Botox® alternative”

(d) “CLINICALLY PROVEN, INSTANT BOTOX® ALTERNATIVE, FREEZES WRINKLES INSTANTLY”

(e) “Freezeframe with INHIBOX is the original Instant Botox® Alternative”

(f) “… a topical alternative to Botox® injections …”

(g) “The original Instant Botox® Alternative, freezeframe INHIBOX has been a number 1 seller all over the world”.

83 Self Care admitted it had not given undertakings in respect of the statements there pleaded.

84 Allergan pleaded, at 2FASOC [44F], that, by making these statements, Self Care expressly or impliedly represented, in trade or commerce, that use of the Inhibox product would achieve:

results that are at least the same standard of quality as Botox (injection);

the same performance characteristics uses and/or benefits as Botox.

85 These representations were referred to in the 2FASOC and reasons for judgment as the “efficacy representations”. Allergan pleaded that both representations were as to a future matter for the purposes of s 4 of the ACL and that Self Care did not have reasonable grounds for making the representations: 2FASOC [44G], [44H].

86 Allergan pleaded in the alternative, at 2FASOC [44I], that, to the extent the representations were not as to a future matter, the representations were false because:

use of the Inhibox product does not achieve results that are at least the same standard or quality as Botox (injection);

use of the Inhibox product does not achieve the same performance characteristics uses and/or benefits as Botox;

the Inhibox product (as a cream) is not of the same standard or quality as Botox (as an injection); and

the Inhibox product does not have the same performance characteristics uses and/or benefits as Botox.

87 Allergan pleaded that Self Care had:

(1) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the ACL: 2FASOC [45];

(2) represented that Inhibox had performance characteristics, uses of benefits it did not have in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL: 2FASOC [46]; and

(3) represented that Inhibox was of a particular standard or quality when it was not, in contravention of s 29(1)(a): 2FASOC [46].

88 Self Care denied that the efficacy representations arose from the statements, admitted that the efficacy representations, if made, constituted representations as to future matters for the purposes of s 4 of the ACL and that they were made in the course of trade and commerce: J[487]. It denied the contraventions.

89 The primary judge began by examining whether the pleaded representations were made: J[493]. His Honour correctly described the task in the following way:

That exercise includes identifying the statements that are complained of which are said to give rise to the pleaded representations and to construe them in the whole of their context and thereby identify whether, in that context, they make the pleaded representations. This includes consideration of the target consumer or class of consumers and the likely effect on the ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class of consumer, i.e., disregarding extreme or fanciful reactions: Campomar at [105].

90 The primary judge noted at J[497] that the context included that:

(1) the reputation of Botox was as an injectable anti-wrinkle treatment that can only be administered by healthcare professionals;

(2) the Self Care products were all topical creams, serums and lotions that are typically self-applied;

(3) the cost of a single Botox treatment is substantially more than the cost of an item of any of the Self Care products, and such an item will offer daily treatments for, perhaps, several weeks or even longer depending on individual application habits and techniques; and

(4) there was nowhere where the Self Care products and Botox treatments were both offered for sale.

91 In relation to the first matter of context referred to at J[497] and set out immediately above, Allergan contended that the primary judge should also have found that the reputation of Botox was such that the ordinary reasonable consumer is likely to have known that Botox is a semi-permanent injectable anti-wrinkle treatment that lasts up to four months: Ground 7(b). For reasons given below, the target market would have included reasonable consumers who had the understanding that Botox continued to have effect for a period of 4 months after treatment.

92 As to the class of consumers for Self Care’s products, the primary judge stated at J[498] and J[499]:

… First, it is people who are interested in treatments for the reduction of the appearance of wrinkles who are liable to have their attention drawn to Self Care’s impugned statements. They would likely be aware of Botox, as the survey evidence shows, and they may be people who have used Botox, or who might consider using Botox, or who would not be interested in using Botox. Secondly, they are for the most part likely to be people, men or women, who know something about anti-ageing and/or anti-wrinkle treatments. That is because if they have an interest in the subject matter, which is the reason why their attention might be drawn to Self Care’s statements about its products, they are likely to have previously looked at materials or to have engaged in conversations on the subject matter.

The result is that the ordinary and reasonable consumer on reading the impugned statements in their context is likely to know that Botox is an injectable anti-wrinkle treatment that is available to be administered only by healthcare professionals, that in contrast Self Care’s products are topically self-applied creams, serums and lotions, and Botox is likely to be more expensive than Self Care’s products because it is required to be professionally administered. Also, although probably not being conscious of the fact, such consumers will not have seen or experienced Botox and Self Care’s products being available in the same place.

93 The primary judge’s conclusions on whether the statements, in context, conveyed the representations are contained from J[500] to [504]. The word “alternative” had been used in statements relating to a number of products apart from Inhibox, namely: Protox, Night and Boost – see: J[494], [495]. The primary judge set out the statements which Allergan complained about (in relation to all of the products including Inhibox) by reference to tables which Allergan had put forward in submissions – see: J[107] to [116], [481].

94 The reasons at J[500] to [504] deal compendiously with all of the statements containing the word “alternative” in relation to each of the products. This approach is understandable given the significance which the primary judge attributed to the word “alternative”, the manner in which Allergan appropriately summarised its case, and the number of products and circumstances in which the word “alternative” was used. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that the approach emphasises the perceived importance of the word “alternative” and risks omitting important matters of context specific to the particular products or the specific words of the various statements.

95 The primary judge included a table at J[114], summarising (amongst other things) the statements that Allergan complained of specifically in respect of Inhibox (some had fallen away) and whether Self Care had undertaken not to make the statements anymore – see: J[110]. The table recorded that each statement was relied on as conveying the efficacy representations and also included the following information:

No. | Statement | Undertaking Yes/No |

1 | “Instant BOTOX® alternative” | No |

2 | “The World’s first Instant and Long Term Botox® Alternative” | Yes re “Long term Botox alternative” only |

3 | “The original instant and long term Botox® alternative” | Yes re “Long term Botox alternative” only |

4 | “Clinically Proven, Instant Botox® Alternative” | No |

5 | “Freezeframe with INHIBOX is the original Instant Botox® Alternative” | No |

6 | “…a topical alternative to Botox® injections…” | No |

7 | “The original Instant Botox® Alternative” | No |

96 Each of the statements uses the word “alternative”, with the result that the reasoning at J[500] to [504] applies to each statement. On appeal, Allergan only challenges the conclusion that the statement “instant BOTOX® alternative” did not convey the efficacy representations. Nevertheless, as explained below, this statement must be examined in the context in which it appears and from the perspective of reasonable members of the target market.

97 At J[500], his Honour stated:

In that context, in my assessment the impugned statements that describe the relevant product as an “alternative” to Botox are likely to be understood by ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of consumer as representing that the Self Care product will reduce the appearance of wrinkles to a similar extent as Botox does. The statements convey, in context, that the product will be effective in reducing the appearance of wrinkles. The statements do not say anything expressly about the extent of that effectiveness, particularly with regard to how long any such reduction in the appearance of wrinkles will last. The statements also say nothing about the mechanism of the effect on the reduction in the appearance of wrinkles.

98 His Honour’s conclusion that “[t]he statements do not say anything expressly about the extent of that effectiveness, particularly with regard to how long any such reduction in the appearance of wrinkles will last” must be read subject to the earlier conclusion that reasonable members of the relevant class of consumer would have understood that the “Self Care product will reduce the appearance of wrinkles to a similar extent as Botox does”. The primary judge’s remaining conclusions, may be summarised as follows:

(1) The statements that the relevant product was an “alternative” to Botox:

(a) imply that the product will achieve a similar outcome (being a reduction in the appearance of wrinkles) to Botox, otherwise it would not be an “alternative”: J[501], [503];

(b) do not convey that the effect of the product was the same as the effect of Botox, because the word “alternative” would not have been understood as carrying such an implication: J[502], [503];

(c) do not imply that the Self Care products have the same mechanism or mode of action as Botox: J[502];

(d) in context, were likely to have been understood as distinguishing the product as not having the qualities of Botox that the consumer might regard to be disadvantageous, such as it being an injectable that can only be administered by healthcare professionals and that it is relatively expensive: J[501].

(2) The ordinary and reasonable consumer would appreciate that there are many variables to take into account in choosing one product over another, including the trouble, pain and expense of purchase and administration or application, how long the effects of the product last, and how significant the effects are: J[503].

(3) In summary, the statements, in context, represent that Self Care’s products achieve a similar aesthetic outcome with regard to the reduction in the appearance of wrinkles to the outcome that Botox achieves: J[504].

99 Allergan’s first complaint on appeal was that the primary judge treated the word “alternative” inconsistently when addressing the ACL issues compared to when his Honour addressed the trade mark issues. When determining whether the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” was being used as a trade mark, the primary judge treated the word “alternative” as meaning that Inhibox was not Botox but was a substitute for Botox. If that is correct, Allergan submitted, the primary judge should have concluded that the statement was misleading because Inhibox was not of equivalent efficacy to Botox and, accordingly, not properly described as a substitute.

100 There is no real inconsistency in relation to the primary judge’s treatment of the word “alternative”. On the trade mark issue, the primary judge considered that the word “alternative” signified that Inhibox was different to Botox, not that it was, in all material respects, a substitute. His Honour’s treatment of the effect of the word “alternative” in the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” is consistent with his Honour’s treatment of the effect of the word when dealing with the ACL issues: Inhibox was a different product which could be used as an alternative to Botox to effect a similar reduction in the appearance of wrinkles.

101 Allergan next submitted that the primary judge did not refer to critical matters of context, such as the packaging as a whole, and also did not address marketing statements apart from those which included the word “alternative”. The lack of reference to this material suggested, in Allergan’s submission, that the primary judge did not examine the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” in context, but examined its meaning divorced from context.

102 It must be accepted that, when considering at J[500] to [504] the question whether the statements conveyed the pleaded efficacy representations, the primary judge did not refer to the Inhibox packaging or statements apart from those which included the word “alternative”. Rather, his Honour concluded that the word “alternative” operated in respect of each phrase in the manner described at J[500] to [504].

103 As mentioned, the question on appeal is confined to the statement “instant Botox® alternative”. The question whether that statement conveyed the pleaded representations must be assessed in context, which includes the packaging and marketing material. The question is not the “separate effect” of the statement, less still a particular word in it, but the effect of the conduct as whole, here the making of the statement in a particular context: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [52] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

104 Until about February 2017, the Inhibox applicator was packaged in a box containing a clear plastic window through which one could see the syringe-like applicator: J[77]. The primary judge had earlier noted (but not when dealing with the ACL claims) that the packaging included the words FREEZEFRAME and WITH INHIBOX. It included the phrases “instant Botox® alternative”, “Clinically proven to erase wrinkle appearance in 5 minutes” and “The world’s first Instant and Long Term Botox® Alternative”: J[77]. The front of the packaging was:

105 Since September 2016, the applicator was packaged in a different box without a window: J[78]. This packaging is depicted at [47] above. The primary judge noted the box prominently displayed the words “freezeframe” and “INHIBOX” and also included the phrases “instant Botox® alternative”, “clinically proven to erase eye wrinkles & puffiness in 5 minutes” and “The original instant and long-term Botox® alternative”: J[78].

106 The primary judge stated at J[83]:

From about October 2012, the Inhibox product together with the statements below have been included on the Freezeframe website at various times, for various periods of time:

(1) “CLINICALLY PROVEN

INSTANT BOTOX® ALTERNATIVE

FREEZES WRINKLES INSTANTLY

REDUCES WRINKLES LONG TERM”

(2) “Freezeframe with INHIBOX is the original Instant Botox® Alternative, clinically proven to erase wrinkle appearance under the eyes and on the forehead in just 5 minutes, whilst delivering up to 63.23% reduction invisible [sic] wrinkles in just 28 days”

(3) “a topical alternative to Botox® injections”

(4) “The original Instant Botox® Alternative, freezeframe with INHIBOX has been a number 1 seller all over the world”.

107 The primary judge also noted at J[330] that: (a) the cosmetic skin care products and pharmaceutical treatments for skin ageing and wrinkling such as Botox share a substantially common market; and (b) there was ample evidence of complementary use of certain skin care products and pharmaceuticals. The primary judge accepted at J[473] that there was cross-over in trade channels in that clinics that offer cosmetic injections almost always sell skincare products.

108 Consumers in the target market would have included consumers who considered that there was a common trade origin of Inhibox and Botox given that the Inhibox product bore, prominently on the front of the package, a reference to “Botox®”. The primary judge accepted at J[334] that BOTOX was a powerful brand with a widespread reputation and that, if it was applied to a topical cosmetic product, ordinary reasonable consumers would draw a connection between the product and the owner of the trade mark BOTOX; the ordinary reasonable consumer would not conclude that the product had a different trade source because it was not injectable.

109 Consumers in the target market would include consumers who would appreciate that Botox requires a short period after injection for its full effect to show and then has a reasonably long lasting effect. Botox will usually have an effect for about 4 months: J[11].

110 The target market would have included consumers who, acting reasonably, understood from the phrase “instant Botox® alternative”, when read in context, that Inhibox was an instant alternative to Botox in that Inhibox would reduce the appearance of wrinkles to a similar extent as Botox, but that its mode of operation was topical rather than by injection, and its anti-wrinkle effects occurred instantly rather than after days. Some reasonable consumers would have understood from the statement, in the context in which it was made, that Inhibox would provide a long term effect, after treatment ceased, comparable to that provided by Botox. Some reasonable consumers, at least before further inquiry or sober later consideration, may have thought from the phrase “instant Botox® alternative”, read in context, that the long term effect of Inhibox would be achieved after a single use in common with a single Botox treatment. In particular, the phrase “instant Botox® alternative” appearing on the website with the statements – “freezes wrinkles instantly” and “reduces wrinkles long term” – would have been understood by some reasonable members of the class as meaning that the product would reduce the appearance of wrinkles instantly and that the effect would last long term, the term being comparable to that obtained through treatment by Botox injection. The earlier packaging (through which the syringe-like applicator is visible), which contained the statement “instant Botox® alternative” also contained the statement “The world’s first Instant and Long Term Botox® Alternative”. Some consumers acting reasonably would have thought that a long term effect could be achieved through a single use, but more would reasonably have assumed that a long term post-treatment effect, equivalent to Botox, could be achieved through use of the Inhibox product over some undefined but reasonable time.

111 Self Care submitted on appeal that the agreed expert evidence established that Inhibox had an instant effect of reducing the appearance of wrinkles and that the evidence also “provided support for a long-term effect” of Inhibox. In support of the former submission reference was made to paragraphs (3) and (4) of J[532] and, in relation to the long term effects of Inhibox, reference was made to paragraph (5) of J[532] and J[549] to [568]. J[532] must be read with J[529]:

Self Care’s identified support for the claims

[529] Self Care identified the following ingredients and related studies, and in some cases other evidence as well, as supporting the relevant claims.

…

[532] In support of the proposition that the Inhibox product reduces the appearance of wrinkles:

(1) Study 5, a short term study using the Inhibox product itself, concluded that the product reduces the appearance of wrinkles in five minutes (i.e., an instant effect). Further measurements after eight hours confirmed that the effect is long lasting. This study is discussed in more detail in the next paragraph.

(2) A video of raw footage of Ms Amoroso applying the product to a woman’s face shows the efficacy of the product. Ms Amoroso’s evidence was that the video was created in about 2014 for educational and advertising purposes. It can be seen that as she applies the product on the woman’s frown lines and crow’s feet and around the eyes a transparent film is formed on the skin which tightens during the drying process and pulls the skin taut. It appears to have the visual effect of smoothing out wrinkles and lifting the area.

(3) In respect of a particular ingredient (identified as item 4 in the formulation), Mr Williams said that it creates the tightening effect on the surface of the skin seen in Study 5. The experts agree that it has an anti-wrinkle effect on skin surfaces – Dr Hayley categorises it as a wrinkle filler and Mr Williams says that it forms a “smooth wrinkle filling form when dry”.

(4) Studies 3 and 4 (in respect of Active H) show an instant tightening effect that reduces the appearance of wrinkles within 10 minutes and lasts for 3-4 hours. The experts agreed that the ingredient in Active H reduces wrinkles by forming a film and tightening the skin when dry.

(5) Studies 1 and 2 (in respect of Active A), are in vivo studies which show that Active A reduces the appearance of wrinkles in 28 days. These studies are discussed in more detail at [549]-[568] below.

112 It was not in dispute that Inhibox reduced the appearance of wrinkles quickly enough to describe the effect in a non-misleading way as “instant”. There was no significant challenge to the primary judge’s conclusion that a representation to the effect that Inhibox would reduce the appearance of wrinkles to a similar extent as Botox was not misleading or deceptive. However, it was not accepted that there were reasonable grounds for representing that Inhibox had long lasting effects equivalent to treatment with BOTOX. Allergan submitted such a representation was false.

113 The evidence did not establish that Inhibox had long term effects equivalent to BOTOX or that there were reasonable grounds for representing that it did. On the findings of the primary judge, the high point of the evidence was that Study 2 “offers a reasonable foundation to the claim that Active [ingredient] A produces a significant reduction in the appearance of wrinkles over a 28-day period of application”: J[568]. That, of course, only establishes that continued use over 28 days reduces wrinkles and says nothing about the long term effect once treatment ceases. The effects of treatment with Inhibox are noticeable for up to between 5 and 8 hours after application: J[533]. The studies which Self Care relied upon did not include any studies comparing the effect of treatment with Botox with treatment with Inhibox: J[489].

114 The statement “instant Botox® alternative”, in context, conveyed to reasonable consumers in the target market that: (a) use of Inhibox would result in a similar reduction of the appearance of wrinkles to that which would be achieved with treatment by Botox; and (b) the effect would last, after treatment, for a period equivalent to that which would be achieved with treatment by Botox injection. Self Care had reasonable grounds for making the former representation, but did not have reasonable grounds for making the latter representation, there being no scientific or other material from which such a representation could reasonably be made. The latter representation was misleading or deceptive with the result that Self Care contravened s 18 of the ACL. The representation also contravened ss 29(1)(a) and (g) of the ACL.

115 It should be observed that Allergan’s “efficacy representations” were pleaded at a level of generality, namely that the statement expressly or impliedly represented that use of the Inhibox product would achieve (a) results that are at least the same standard of quality as Botox (injection); (b) the same performance characteristics uses and/or benefits as Botox: 2FASOC [44F]. Notwithstanding, the trial was conducted on the basis that the relevant results or characteristics were the extent of reduction in the appearance of wrinkles and the length of time results would last.

THE AMENDED NOTICE OF CONTENTION