FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2021] FCAFC 159

National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2020] FCA 1709 | |

File number(s): | NSD 1373 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | ALLSOP CJ, JAGOT AND RANGIAH JJ |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – university – right of intellectual freedom – whether primary judge erred in construction of right of intellectual freedom in enterprise agreement – whether primary judge erred in finding that exercise of intellectual freedom can constitute “misconduct” or “serious misconduct” within meaning of enterprise agreement – whether conduct in posting photo to social media was sufficiently connected to his employment to constitute “misconduct” – whether University gave lawful and reasonable instruction to remove photo – whether failing to remove photo constituted “misconduct” – appeal allowed – matters remitted to primary judge for hearing and determination. |

Legislation: | Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ss 50, 340, 539, 545 |

Cases cited: | Boston Deep Sea Fishing and Ice Co v Ansell (1888) 39 Ch D 339 Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) [2001] FCA 1833; (2001) 117 FCR 424 Concut Pty Ltd v Worrell [2000] HCA 64; (2000) 75 ALJR 312 Dare v Pulham [1982] HCA 70; (1982) 148 CLR 658 Downer EDI Limited v Gillies [2012] NSWCA 333; (2012) 92 ACSR 373 Eldridge v Wagga Wagga City Council [2021] NSWSC 312 James Cook University v Ridd [2020] FCAFC 123; (2020) 382 ALR 8 Linkhill Pty Ltd v Director, Office of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] FCAFC 99; (2015) 240 FCR 578 Mercer v Whall (1845) 5 QB 447 National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2020] FCA 1709; (2020) 302 IR 272 Ridgway v Hungerford Market Company (1835) 3 AD & E 171 Shepherd v Felt and Textiles of Australia Ltd (1931) 45 CLR 359 Suttor v Gundowda [1950] HCA 35; (1950) 81 CLR 418 Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited v Marmara [2014] FCAFC 84; (2014) 222 FCR 152 United Group Rail Services Ltd v Rail Corporation New South Wales [2009] NSWCA 177; (2009) 74 NSWLR 618 |

Division: | Fair Work Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Employment and Industrial Relations |

Number of paragraphs: | 292 |

Date of hearing: | 12 July 2021 |

Date of last submissions: | 19 July 2021 |

Counsel for the Appellants: | Mr B Walker SC with Ms S Kelly |

Solicitor for the Appellants: | National Tertiary Education Industry Union |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Ms K Eastman SC with Mr D Lloyd |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Ashurst Australia |

ORDERS

| ||

NATIONAL TERTIARY EDUCATION INDUSTRY UNION First Appellant

TIM ANDERSON Second Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

ALLSOP CJ, JAGOT AND RANGIAH JJ | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. Order 1 made on 26 November 2020 be set aside.

3. The matter be remitted to the primary judge on terms to be decided.

4. The parties may file and serve written submissions not exceeding 10 pages identifying their proposed issues for the remittal and any amendment to the pleadings requested, and reasons in support, within 14 days of the date of these orders.

5. If any party files and serves written submissions in accordance with order 4, the other parties may file and serve written submissions in reply not exceeding 10 pages within a further seven days thereafter.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

1 I have read the reasons for judgment of Jagot J and Rangiah J. I agree with the orders proposed by their Honours. Their Honours’ detailed recounting of the facts and circumstances of the matter below and on appeal, which I gratefully adopt, permits me to express my reasons shortly.

2 I agree with the reasons of Jagot J and Rangiah J in relation to the “lunch photo”. The conduct in relation to this was not asserted to be an exercise of intellectual freedom. Whilst it can be accepted that many features of world affairs give rise to contradictory and sometimes mutually hostile opinions, the apparently deliberate posting on Facebook of a photograph of a badge on the arm of a colleague on a social occasion that said “Death to Israel” and “Curse the Jews” can be characterised as anti-Semitic. I agree with Jagot J and Rangiah J that the refusal to take down the post can be characterised as Misconduct if the removal direction was lawful and reasonable. Whether posting the lunch photo was Misconduct or Serious Misconduct and if so, whether failing to remove the photo was Serious Misconduct is a question (for the reasons given by Jagot J and Rangiah J) that should be remitted to the primary judge, to be assessed in the light of all the circumstances.

3 I turn to the balance of the controversy. Subject to what follows, I agree with the reasons of Jagot J and Rangiah J.

4 Central to resolution of the controversy is the proper construction and ascription of meaning and content to cll 315–317 of the 2018 Enterprise Agreement (in relevant respects identical to cll 254–256 of the 2013 Enterprise Agreement).

5 The provisions deal with a central feature of university and academic life; indeed the subject, intellectual freedom, goes to the heart of the nature and character of the institution of the university itself.

6 The three clauses naturally fit together and are to be construed in the context of each other, and in the context of the whole of the Agreement. Clause 315, in terms, recognises the rights which are part of the concept of intellectual freedom to the protection and promotion of which concept, and which rights, the parties expressly state their commitment. These are not on their face words of mere aspiration. They are words of commitment. That the parties are committed, is not in its context a mere description of their respective views; it is the expression of a commitment that they make, to each other. The freedom (to whose protection and promotion the parties express their commitment) is not apt for exhaustive definition, but it is apt for non-exhaustive description or identification of relevant conduct – a process undertaken by the parties in their inclusive list of rights in subcll (a) and (b)(i)–(iv). Those rights were stated to be part of the freedom. That the freedom is difficult or impossible to define exhaustively is no reason to diminish the clarity with which the Agreement expresses the nature of the rights. Rights to the protection and promotion of which the parties express their commitment is naturally the expression not of aspiration, but of obligation. The terms of cl 315 are apt to mean that the parties commit themselves to the contents of the clause, including the protection and promotion of the expressed rights. The Agreement is to be the basis of the relationship between the parties for its term. The words “are committed” should not be understood as speaking only as at 12 December 2017 when the Agreement was signed. The present tense should be seen as continuous and the commitment as ongoing and real. There does not need to be a separate promise to maintain the commitment made on 12 December 2017 into the future. Even if one did look at it in that restricted temporal fashion, the clause still is an express recognition of the rights set out, which the staff enjoy: such should be construed as legal rights that staff are free to exercise. The recognition of the rights is to be understood as a clear agreement that staff are permitted, indeed have the right, to act as set out in cl 315 (a) and (b).

7 Clauses 316 and 317 are expressed in terms as to how the parties will act in the future. Clause 317 can be seen to include an undertaking by staff to uphold the practice of intellectual freedom: that is to exercise the rights in practising intellectual freedom, in a way which accords with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

8 So, cl 315 recognises the rights and the parties’ commitment to protecting and promoting them; and by cl 317 the parties agree to exercise the rights in accordance with the highest standards.

9 That the freedom involved is in its entirety not capable of precise and comprehensive or exhaustive definition does not mean that an expressed commitment to it for the life of the Agreement is not meaningful and no more than aspirational. The parties identified constituent rights with some clarity. Whether the commitment to the protection and promotion of the freedom and the rights has been contravened and whether conduct falls within the freedom or the rights as expressed can be the subject of evidence and debate. The freedom and rights are not so uncertain or indefinable as to be incapable of legal characterisation or as to make an assessment of a contravention or not of the commitment impossible. A breach of an express undertaking to do something, the boundaries of which are unclear may be hard to prove, but it does not follow that the undertaking is legally unenforceable or lacking in enforceable content: see for example, in the context of an express obligation to negotiate the resolution of contractual differences in good faith, United Group Rail Services Ltd v Rail Corporation New South Wales [2009] NSWCA 177; 74 NSWLR 618 at 639 [74].

10 It follows from this that the primary judge erred in not giving to cl 315 the legal reality which its terms admit.

11 The recognition of the right of staff to conduct themselves in accordance with cl 315, including relevantly here, right (b)(iv), means that Misconduct, Serious or otherwise, must be assessed within that frame of reference.

12 Also, the commitment to the protection and promotion of the freedom and the rights in cl 315 is capable of contravention. Any contravention of cl 315 was in the conduct of the University in seeking to have Dr Anderson desist from the activity complained of, to remedy the conduct, to take steps to discipline him, and eventually to terminate his employment. The relevant question is whether it can be concluded that the University, by its conduct, failed to protect or promote the freedom or the rights. One way of putting the matter is that the University is obliged not to discipline or punish or threaten to discipline or punish a member of staff if the member of staff exercises the freedom or right lawfully.

13 Breach of cl 317 was not pleaded by Dr Anderson and the Union. The reason for this is not curious, nor is it defining of the case. The right to which the University committed itself to protect and promote is, relevantly, that in cl 315(b)(iv). By cl 317, Dr Anderson agreed to uphold the practice of intellectual freedom and (reading cll 315 and 317 together) to exercise the right in cl 315(b)(iv) in accordance with the highest standards set out in cl 317. He could have added cl 317 to this pleading and have asserted that there was a breach of cl 315 by a failure of the University to protect and promote the right ((b)(iv)) exercised by him and also a breach of cl 317 by a failure of the University to uphold the practice of intellectual freedom by his exercise of the rights in (b)(iv) that he undertook in accordance with the highest standards. Or, he could confine himself to cl 315 and let the University say in answer to that, that any exercise of rights under cl 315 was not in accordance with the highest standards set out in cl 317 and so there could be no contravention of cl 315 by the University.

14 As the reasons of Jagot J and Rangiah J show, the second of those courses was taken by Dr Anderson and by the respondents, who were at all times alive to cl 317 and its significance and propounded it in answer (in the alternative) to the case made by Dr Anderson for contravention of cl 315. In opening (as discussed by Jagot J and Rangiah J) Dr Anderson’s counsel also appeared to call in aid cl 317. The absence of reliance on a contravention of cl 317 as a foundation for a penalty (in the pleading and in final address) did not remove or make the clause irrelevant, either to assist in the construction of cl 315, or as available in partial answer to the claim made for contravention of cl 315.

15 Once one concludes that cl 315 contains an obligation to protect and promote the freedom and the relevant rights identified that is capable of being contravened, it becomes necessary to reconcile cll 315 and 317 with the balance of the Agreement. Clause 306 requires the staff to comply with the “Codes of Conduct (as defined in clause 3)”. Clause 3 contains a definition of one Code, which in its terms incorporates the University’s Public Comment Policy. Given that the Code of Conduct and Public Comment Policy are not part of the Agreement (whether referred to in the Agreement or not: see cl 14) a clear hierarchy of reconciliation can be seen in the Agreement between, on the one hand, the (general) Code of Conduct and Public Comment Policy and, on the other hand, the (specific) protection and promotion of the freedom and rights in cll 315–317, to which the parties are obligated. Those rights in cll 315–317 are not to be diluted, undermined or derogated from by some requirement otherwise on its face applicable in the Code of Conduct or Public Comment Policy. The freedom and rights in cl 315 are important and are specific rights to which the parties have committed, that is obligated themselves. A general obligation to conduct oneself in accordance with a Code of Conduct drawn from time to time by one party, the University, should not be seen to derogate from the mutual agreement to protect and promote a specific and important freedom and specific and important rights, albeit including the manner of the exercise of the freedom or of the rights. The question whether or not the Code of Conduct has been breached is subsidiary to an inquiry whether what occurred was an exercise or attempted exercise of one of the rights in cl 315 or otherwise an exercise or attempted exercise of intellectual freedom, recognising the obligation to exercise the right in the manner provided for by cl 317. That inquiry may make the Code of Conduct relevant to an assessment of compliance with the standards referred to in cl 317, but it does not follow that any breach of the Code of Conduct according to its own terms is a failure to exhibit the standards called for in cl 317. As the reasons of Jagot J and Rangiah J make clear, it is not easy to see how one finds in this Code of Conduct requirements that truly inform, in any given case, the exercise of the right in cl 315(b)(iv) or of the freedom. The expression of unpopular or controversial views may well, for instance, be seen to lack sensitivity to the feelings of others. The Code of Conduct, as an inferior document in the hierarchy of documents in the Agreement, cannot, by its terms, reduce the content of cl 315, exercised in accordance with the standards set in cl 317.

16 The inquiry is not whether the Code of Conduct has been breached according to its terms, divorced from cll 315 and 317. The relevant inquiry calls for an assessment of whether or not a right or the freedom in cl 315 was being exercised or attempted to be exercised and if so whether it was exercised or attempted to be exercised in accordance with the standards in cl 317. To the extent that the Code of Conduct can inform the inquiry as to whether the standards referred to in cl 317 were manifested in the exercise of the freedom or right, it will be relevant. As the reasons of Jagot J and Rangiah J demonstrate, however, that last expression of the relevance of the Code of Conduct is more easily expressed than applied. For instance, to the extent that notions of demonstrating respect, impartiality, courtesy and sensitivity are required by the Code of Conduct, or exercising appropriate restraint by the Public Comment Policy, it may be difficult to see how, in a given case, these can qualify an exercise of the right to express unpopular or controversial views, provided that there is no harassment, vilification or intimidation. In any given case, the exercise of the right in cl 315(b)(iv) according to its terms might necessarily be seen by some as, or might necessarily be, discourteous or lack sensitivity. The relevant question is whether there has been an exercise of the freedom or right in cl 315 and whether it was to the standards referred to in cl 317. It is not just a question of whether the Code of Conduct or Public Comment Policy has been breached according to its terms. I agree with Jagot J and Rangiah J, and for the reasons their Honours give, that the approach of the Court in James Cook University v Ridd [2020] FCAFC 123; 382 ALR 8 can be distinguished by reference to the different terms of the enterprise agreement before the Court in that case.

17 If the conduct was an exercise of the right or freedom in cl 315, in accordance with the highest standards in cl 317, there can be no question of there having been Misconduct, Serious or otherwise, by reference to the Code of Conduct or Public Comment Policy. The rights and the freedom to which the parties have committed themselves are to be construed as superior in hierarchy in the Agreement to the general obligations in the Code of Conduct and the Public Comment Policy, if such on their face would be inconsistent with, or undermine, or dilute the exercise of the right to the standards agreed. If it be the case that what has occurred can be characterised as the exercise or attempted exercise of the freedom or one of the rights, but one that was not in accordance with the standards required by cl 317, the question of any Misconduct would have to be assessed by reference to the failure to exercise the freedom or rights in accordance with the highest standards. The departure from those standards would be the conduct from which any judgment of Misconduct is to be made. The above enquiry should not be approached mechanically by concluding that the freedom or right in cl 315 was not validly exercised under cl 317 and so the conduct can be judged simply by reference to the Code of Conduct, ignoring otherwise cll 315 and 317. If the conduct is properly characterised as an exercise or attempted exercise of the freedom or right, but not at the highest standards, the vice of the conduct is in the departure from those standards, which may or may not be Misconduct, Serious or otherwise.

18 If the conduct cannot be characterised as an exercise of the freedom or one of the rights in cl 315, then the conduct will be assessed simply by reference to the Code of Conduct.

19 Thus, the Misconduct, relevantly here Serious Misconduct, must be assessed by reference to the freedom and rights in cl 315, to be exercised in accordance with the standards in cl 317. The terms of cl of 384(d)(iii) and cl 434 make clear that there must be the engagement by the member of staff in Serious Misconduct for the employment of the staff member to be terminated without notice. Dr Anderson at all times asserted that he had not engaged in Serious Misconduct. The state of satisfaction of a delegate (here, Professor Garton) was necessary for disciplinary action, but for the termination to be valid, the engagement in Serious Misconduct must have occurred, as a matter of fact. That was for the Court to decide.

20 There was a dispute about whether Dr Anderson engaged in Serious Misconduct. That dispute was not resolved by accepting Professor Garton’s state of satisfaction, as not having been put in issue. The facts had to be assessed by the Court, recognising the legal rights of Dr Anderson under cl 315, qualified in the manner of exercise by cl 317, not diluted or undermined, by the Code of Conduct. In my respectful view, the errors of the primary judge, all of which can be seen to be encompassed within or stem from the success of grounds 1 and 2 of the notice of appeal, were:

(a) failing to give legal effect to cl 315;

(b) failing to assess the question whether there was Serious Misconduct in the context of the asserted exercise of the right to intellectual freedom and specifically to exercise the right in cl 315(b)(iv), and failing to make the necessary finding whether there was an exercise of the right in cl 315(b)(iv) or the freedom otherwise, and if so whether such was in accordance with the standards set out in cl 317;

(c) failing to address the question of the general obligations in the Code of Conduct by reference to their subordinate status to the specific rights in cll 315 and 317 in the Agreement in the hierarchy of relevant documents in any such assessment;

(d) failing to recognise that an exercise of a right under cl 315 in accordance with cl 317 could not be Misconduct; and

(e) failing to make a finding necessitated by cl 384(d)(iii) (and indeed cl 434, though not pleaded nor the subject of submission) as to whether Serious Misconduct occurred and by addressing the issue of Serious Misconduct by relying upon Professor Garton’s unchallenged state of satisfaction as to that matter and in so doing failing to address the question whether the University in fact had power to terminate Dr Anderson’s employment.

21 The above was the proper framework for relevant fact finding and assessment as to whether Dr Anderson was guilty of Serious Misconduct to justify the termination of his employment and whether the Agreement had been contravened by the University’s conduct in the case for remedies for a contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth).

22 Whether or not there has been a contravention of the Agreement and so a contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act depends upon the provisions of the Agreement. If Dr Anderson’s employment has been terminated without notice in circumstances where there had been no Serious Misconduct that would be a contravention of cl 384(d)(iii), or cl 434. (Even if cl 384 is construed as procedural, it nevertheless prevents, in terms, termination of a staff member’s employment in the absence of Serious Misconduct.) Clause 434 was not pleaded. On appeal, the case under cl 384 was abandoned. Termination without notice in the absence of Serious Misconduct may also be a breach of the employment contract, but such was also not pleaded. Whether or not cl 315 was contravened depends on the question whether the University by its conduct failed to protect or promote the freedom or the right in cl 315(b)(iv). Whether there has been a contravention of cl 315 should be the subject of a remitted hearing as part of the hearing as to whether Dr Anderson engaged in Serious Misconduct as the basis for the termination of his employment.

23 As provided for in the orders, the parties will be heard on the question and terms of the remitter. The remitter should not be such as to reopen the hearing to more evidence, at least substantive evidence. The parties have had their trial. Whether or not the remitter should contain any leave to amend to accommodate matters not currently pleaded can be debated before us as to the terms of the order for remitter. As presently minded, I would tend to the view to keep the appellants substantially to the case they ran below.

I certify that the preceding twenty-three (23) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop. |

Associate:

Dated: 31 August 2021

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JAGOT AND RANGIAH JJ:

24 These reasons for judgment explain why the appeal must be allowed and the matter remitted to the primary judge for further submissions and determination. The parties will be heard further about the scope of the remittal.

1. Background

25 The appellants, the National Tertiary Education Industry Union (the NTEIU) and Dr Tim Anderson, appeal against the orders of the primary judge dismissing their application: National Tertiary Education Industry Union v University of Sydney [2020] FCA 1709; (2020) 302 IR 272 (referred to below as J).

26 The appellants had applied for declarations that the respondents below, the University of Sydney, the Provost and Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the University (Professor Garton), and the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (Professor Jagose) (together, the respondents), had contravened s 340(1) (the protection from adverse action) and s 50 (contravention of an enterprise agreement) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), and consequential orders that Dr Anderson be reinstated and paid compensation, and for pecuniary penalties to be paid to the NTEIU.

27 The University had terminated Dr Anderson’s employment without notice on 11 February 2019 following a number of warnings relating to a series of comments and posts by Dr Anderson on social media and the convening of a review committee as required by the applicable enterprise agreement, the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2018-2021 (the 2018 agreement).

28 Dr Anderson claimed that: (a) the comments as pleaded constituted the exercise by Dr Anderson of intellectual freedom within the meaning of cl 254 of the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2013-2017 (the 2013 agreement) and the equivalent cl 315 of the 2018 agreement and, by reason thereof, did not constitute “misconduct” within the meaning of either agreement, (b) as a result, there was no lawful right, power or authority of the University to give any warning to Dr Anderson about the comments, (c) in giving Dr Anderson the warnings about the comments the University breached cll 254 and 309 of the 2013 agreement and cll 315 and 384 of the 2018 agreement (as applicable), and thereby contravened ss 50 and 340 of the Fair Work Act, (d) in posting the so-called lunch photo Dr Anderson did not engage in misconduct as it was not sufficiently connected to his employment, (e) as a result, there was no lawful right, power or authority of the University to give any warning to Dr Anderson about the lunch photo, (f) in giving Dr Anderson a warning about the lunch photo the University breached cll 315 and 384 of the 2018 agreement, and thereby contravened ss 50 and 340 of the Fair Work Act, and (g) in terminating Dr Anderson’s employment without notice the University breached cll 254 and 309 of the 2013 agreement and cll 315 and 384 of the 2018 agreement (as applicable), and thereby contravened ss 50 and 340 of the Fair Work Act.

29 The primary judge dismissed the amended originating application.

2. The appeal

30 The appeal is brought on three grounds.

31 First, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred by:

(a) finding (at [7] and [140] … ) that cl 254 of [the 2013 agreement] did not, and cl 315 of the University of [the 2018 agreement] does not, create any enforceable obligations; and

(b) failing to find that cl 254 of the 2014 created, and cl 315 of the 2018 Agreement creates, an enforceable right to intellectual freedom consisting of, among other things, the rights enumerated in each clause.

32 Second, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred by:

(a) finding (at [7], [140(4)], [140(5)] and [140(6)] … ) that an exercise of intellectual freedom can constitute “misconduct” or “serious misconduct” within the meaning of the 2013 Agreement and the 2018 Agreement; and

(b) failing to find that conduct that constitutes an exercise of intellectual freedom within the meaning of cl 254 of the 2013 Agreement and/or cl 315 of the 2018 Agreement could not constitute “misconduct” or “serious misconduct” within the meaning of cl 3 of the 2013 Agreement or cl 3 of the 2018 Agreement (as the case may be).

33 Third, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred by:

(a) finding (at [227] and [236]) that Dr Anderson’s conduct in posting a photograph to Facebook (defined in the statement of claim and the [reasons for judgment] as the Lunch Photo) was sufficiently connected to Dr Anderson’s employment to constitute misconduct within the meaning of the 2018 Agreement;

(b) finding (at [235]) that the University gave Dr Anderson a lawful and reasonable instruction to remove the Lunch Photo from his Facebook page; and

(c) failing to find that:

(i) the sole basis on which the University found that Dr Anderson’s conduct in posting the Lunch Photo to Facebook constituted misconduct within the meaning of cl 3 of the 2018 Agreement was that it allegedly infringed the University’s code of conduct;

(ii) in posting the Lunch Photo, Dr Anderson was not performing any “University duties or functions” and that, accordingly, the University’s code of conduct did not apply to his conduct;

(iii) further and in any case, Dr Anderson’s conduct in posting the Lunch Photo to Facebook was not sufficiently connected to Dr Anderson’s employment to authorise the University to discipline him for doing so;

(iv) accordingly, the University had no lawful right, power or entitlement to discipline Dr Anderson for posting the Lunch Photo; and

(v) the instruction the University issued to Dr Anderson to remove the Lunch Photo from Facebook was not a lawful and reasonable direction.

34 The appeal is brought against the University only. It appears that the appellants may not seek to disturb the orders below insofar as they relate to Professors Garton and Jagose. If so, it is not apparent how this is to be achieved other than through the orders relating to the remittal of the matter. On that basis, Professors Garton and Jagose are necessary parties to the appeal and an order should be made for their joinder as respondents. The parties should consider this aspect of the matter and address it in their proposed further submissions about the remittal.

35 Unfortunately, the hearing of the appeal descended into a debate about the case the appellants put below. The University submitted that the appellants had not put the case as they argued it in the appeal and were not entitled to do so. The appeals books did not contain the material necessary for this debate to be resolved and so the parties were given an opportunity to make further submissions in writing about it after the hearing of the appeal, and to file further supporting material. The University also contended that the appeal was moot in the sense that even if the primary judge had erred as alleged, the errors were not material as there were independent findings supporting the dismissal of the amended originating application. Further, the University said it wished to be heard further on the scope of any remittal of the matter to the primary judge.

36 The appellants contended that the only change to their case was that they no longer pressed the claim that the University had breached cl 384 of the 2018 agreement (and the equivalent cl 309 of the 2013 agreement). They also contended that the appeal was not moot as, if the appellants are correct, the primary judge did not make the necessary findings to dismiss the appellants’ case.

37 The appellants are correct. To understand why the appellants are correct it is necessary to identify the claims made and arguments put below and the reasoning of the primary judge. It should also be noted that senior counsel for the appellants, Mr Walker SC, did not appear below. In the appeal Mr Walker SC exposed a number of the problems below, but issues requiring further consideration (necessary for a sensible remittal of the matter to the primary judge) remain.

3. The enterprise agreements

38 The primary judge referred to the provisions of the 2018 agreement only, as the provisions of the 2013 agreement and the 2018 agreement are the same, albeit with different clause numbers. The same course is adopted below, recognising that Dr Anderson’s employment was terminated under the provisions of the 2018 agreement, but some of the earlier warnings were given under the 2013 agreement.

39 The equivalent provisions are as follows:

2018 agreement | 2013 agreement |

315 | 254 |

316 | 255 |

317 | 256 |

384 | 309 |

4. Summary of conclusions

40 As will be explained, the primary judge did not receive adequate assistance from the parties below and his Honour’s process of reasoning accordingly miscarried as follows:

(1) in respect of the claimed exercises of the right of intellectual freedom by Dr Anderson, the primary judge, in effect, said he was holding the appellants to their case as pleaded relying on cl 315 of the 2018 agreement and thus misconstrued cll 315-317 of that agreement, in circumstances where:

(a) in oral and written opening submissions before the primary judge, the appellants had accepted that cl 315 could not be construed in isolation from cl 317 and had accepted that any exercise of rights under cl 315 had to be in accordance with that clause and cl 317, and the respondents made no objection to the appellants having done so;

(b) the respondents’ primary and alternative cases before the primary judge were also to the effect that cl 315 could not be construed in isolation from cl 317. Their primary case was that cl 315 and/or both clauses conferred no enforceable rights capable of contravention. Their alternative case was that if, contrary to their primary case, cl 315 and/or both clauses did confer such rights, the rights had to be exercised in accordance with both clauses and the University’s Code of Conduct;

(c) as a matter of forensic logic it was for the appellants to plead that Dr Anderson’s conduct involved the exercise of the right in cl 315 (which they did) and for the respondents to plead that if cl 315 involved an enforceable right (which it does) then the right had to be exercised in accordance with cl 317 (which they did not plead, but did put to the primary judge); and

(d) as a result, if there was any deficiency in the appellants’ pleading in not referring to cl 317 as a qualification on the right conferred by cl 315 (which there was not), the deficiency could not have been material;

(2) the parties did not draw the primary judge’s attention to the consequences of the fact that the appellants had pleaded and were running a number of separate cases (apart from their adverse action case under s 340, rejected by the primary judge and no longer pressed), being:

(a) a case that the University’s warnings and termination involved a breach of cl 384. It was said by the appellants that, as a result, the University contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act, making available the relief of compensation and reinstatement as specified in s 545 of that Act (a provision regrettably not pleaded or mentioned in the appellants’ submissions before the primary judge, despite it being the source of the main relief sought). The primary judge rejected this cl 384 case. The appellants did not press this case in the appeal. As explained below, however, this creates a problem for the appellants. It is also apparent that in rejecting the cl 384 case, again due to the oversight of the parties, the primary judge does not mention some other critical provisions (cll 90 and 434) which assist in identifying the role of cl 384 and would have made the function of cl 384(d)(iii) clear;

(b) a case that the University’s warnings and termination were in breach of cl 315 of the 2018 agreement. It was said that, as a result, the University contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act, making available the relief of compensation and reinstatement as specified in s 545 of that Act; and

(c) a case that, even if the fourth comments and the fifth and sixth comments did not involve the exercise of the right in accordance with cll 315-317 they were not, in any event, misconduct at all (as to the fourth comments) or serious misconduct (as to the fifth and sixth comments). This meant that the Court also had to determine these issues for itself, but the primary judge did not do so and instead confined himself to considering the reasonableness of the state of satisfaction reached by the University’ delegate in this regard; and

(3) the primary judge’s observation at J [141] that if the appellants had “pleaded a case based on breach of cl 317, the result would not have been any different” is incorrect as his Honour’s observation to the same effect about the fifth comments at J [257]. This is because:

(a) the question whether conduct involved the exercise of the right of intellectual freedom in accordance with cll 315-317 is for the Court to determine for itself in all of the circumstances, whereas the primary judge (apparently relying on the respondents’ erroneous submissions) confined himself to considering the reasonableness of the state of satisfaction reached by the University’ delegate in this regard (which was an issue only in the cl 384 case and not otherwise);

(b) if conduct involved the exercise of the right in accordance with cl 315 (including the inbuilt qualifications on the exercise of that right in cll 315 and 317) then, as the appellants contended, that conduct could not be misconduct or serious misconduct. The primary judge’s contrary conclusion (again based on the respondents’ erroneous submissions) was in error; and

(c) if this was so, the appellants’ contention that the University itself breached cll 315 if it gave warnings to and terminated Dr Anderson’s employment based, in whole or in part, on conduct that involved the exercise of the right in accordance with cll 315-317 had to be addressed, but was not; and

(d) while the appellants’ claims of breach of cl 384 were addressed, the primary judge did so on an erroneous basis (involving a misconstruction of cl 384(d)(iii)), apparently resulting from the fact that the parties never referred his Honour to cll 90 and 434). If the University’s conduct involved breach of cl 384(d)(iii) of the 2018 agreement, the University would have contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act, making available the relief of compensation and reinstatement as specified in s 545 of that Act. The primary judge did not consider these issues.

41 The determination of the remitted matter may also miscarry if the basis and scope of the remittal is not carefully considered. The relevant issues are exposed below and preliminary views provided, but the parties will be given a further opportunity to address these matters. In summary, and without having heard from the parties, it appears that:

(1) the appellants remain able to contend that the University breached cl 315 and thus s 50 of the Fair Work Act by giving warnings to and terminating Dr Anderson’s employment without notice (thereby engaging the potential for relief under s 545 of the Fair Work Act, being compensation and reinstatement, and the imposition of pecuniary penalties in s 539 of the Fair Work Act, s 50 being a civil remedy provision as specified in the table in s 539(2), item 4); and

(2) despite the appellants having said in the appeal that they did not press the cl 384 case, in one respect (the University’s power to terminate employment without notice for serious misconduct as referred to in cl 384(d)(iii) of the 2018 agreement), that claim needs to be pressed. The appellants remain able to contend that the University breached cl 384(d)(iii) and thus s 50 of the Fair Work Act by terminating Dr Anderson’s employment without notice (thereby engaging the potential for relief under s 545 of the Fair Work Act, being compensation and reinstatement, and the imposition of pecuniary penalties in s 539 of the Fair Work Act, s 50 being a civil remedy provision as specified in the table in s 539(2), item 4).

42 As noted, while not apparent from the submissions of the parties to the primary judge or in the appeal, s 545 of the Fair Work Act is the source of power for the orders for reinstatement and compensation sought by the appellants in paras 4 and 5 of the amended originating application.

43 Relevantly, s 545 of the Fair Work Act provides that:

(1) The Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court may make any order the court considers appropriate if the court is satisfied that a person has contravened, or proposes to contravene, a civil remedy provision.

…

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), orders the Federal Court or Federal Circuit Court may make include the following:

(a) an order granting an injunction, or interim injunction, to prevent, stop or remedy the effects of a contravention;

(b) an order awarding compensation for loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention;

(c) an order for reinstatement of a person.

44 Also not referred to by the parties, but critical to understanding cl 384(d)(iii) of the 2018 agreement, is cl 434, which provides that:

A staff member’s employment may be terminated by the University at any time without notice if the staff member engages in Serious Misconduct, subject to a right of review under clause 460.

45 For reasons which cannot be known, neither party drew the primary judge’s attention to this clause of the 2018 agreement despite requiring his Honour to construe cl 384(d)(iii) which reflects cl 434.

5. The primary judge’s reasoning

5.1 Overview

46 There was a statement of agreed facts. The agreed facts included that the University employed Dr Anderson. Dr Anderson was employed as a member of the University’s academic staff on various bases since 1998. The University suspended Dr Anderson’s employment on 3 December 2018 and terminated his employment without notice on 11 February 2019. The agreed facts also included all of the primary facts about Dr Anderson’s conduct.

47 The primary judge recorded that, as Dr Anderson’s impugned conduct extended over several years, both the 2013 agreement and the 2018 agreement were relevant. As the agreements were relevantly identical, references could be confined to the 2018 agreement: J [3]-[4]. This remains the position in the appeal (see above).

48 The primary judge identified three relevant events at J [2], being:

(1) the first warning made by the University on 2 August 2017;

(2) the final warning made by the University on 19 October 2018; and

(3) the termination of Dr Anderson’s employment on 11 February 2019.

49 The primary judge divided the relevant issues in two groups at J [5] as follows:

(1) The first set of issues related to alleged contraventions of s 50 of the [Fair Work Act] and concerned a claimed right to “intellectual freedom”. As framed by the applicants, this part of the proceedings gave rise to the following questions:

(a) whether cl 315 of the 2018 Agreement created an enforceable right to the exercise of “intellectual freedom” and, if so, the content of that right;

(b) whether conduct constituting the exercise of “intellectual freedom” was capable of constituting misconduct or serious misconduct within the meaning of cl 3 of the 2018 Agreement;

(c) whether the conduct of Dr Anderson on which the first warning, final warning and the termination of his employment was based constituted the exercise of “intellectual freedom” and was therefore not capable of constituting “misconduct” or “serious misconduct” within the meaning of cl 3 of the 2018 Agreement; and

(d) whether, if cl 315 of the 2018 Agreement did not immunise the conduct of Dr Anderson leading to the final warning and the dismissal, that conduct was otherwise “misconduct” or “serious misconduct” within the meaning of cl 3 of the 2018 Agreement.

(2) The second set of issues related to alleged contraventions of s 340 of the [Fair Work Act]. This part of the proceedings gave rise to the questions whether:

(a) Dr Anderson exercised a workplace right by making “complaints” within the meaning of s 341(1)(c)(ii) of the [Fair Work Act]; and

(b) the University had established that it did not impose the first warning or the final warning or terminate Dr Anderson’s employment because Dr Anderson exercised any one or more of the workplace rights.

50 As noted, the second set of issues, relating to s 340 of the Fair Work Act, does not form part of the appeal.

51 The primary judge answered the first set of issues in summary form at J [7]:

(1) The 2018 Agreement, including by cl 315, does not recognise the existence of, or give rise to, a legally enforceable right to intellectual freedom of the kind identified the exercise of which can never: (a) constitute “misconduct” or “serious misconduct”; or (b) be the subject of the processes contemplated by cl 384.

(2) The University did not contravene ss 50 or 340 of the [Fair Work Act].

(3) The question of accessorial liability on the part of Professor Garton does not arise in light of the fact that the contraventions are not made out. It is not appropriate to hypothesise what conclusions would have been reached if contraventions of ss 50 and 340 had been established, because the answer would depend on factual findings which have not been made.

5.2 Facts

52 The primary facts are not in dispute. The following summary is extracted from the primary judge’s reasons as indicated.

53 Dr Anderson has been employed by the University since 1998. He was a senior lecturer: J [8]-[10]. At the time of his termination he was employed part-time and taught a post-graduate course, Human Rights and International Development (ECOP6130), in semester 2 of 2015, semester 2 of 2016 and semester 1 of 2018 and a third-year undergraduate unit, Human Rights in Development (ECOP3017), in semester 1 of each of 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018: J [13].

54 Dr Anderson has a Facebook account under the name “Tim Anderson” accessible to the public and used only by Dr Anderson. Until at least mid-2018 the Facebook account identified Dr Anderson as working at the University: J [11].

55 Dr Anderson has a Twitter account accessible to the public and used only by Dr Anderson: J [12].

56 The University had numerous policies in place regulating conduct including a Code of Conduct, relevantly the Code of Conduct – Staff and Affiliates effective from 12 September 2016 and the Code of Conduct – Staff and Affiliates effective from 16 October 2017, and a Public Comments Policy effective from 1 February 2007: J [16].

57 Between 4 and 10 or 11 May 2017, Dr Anderson made various tweets on his Twitter account and posts on his Facebook account. The various tweets and posts, among other topics, related to media coverage concerning Mr Jay Tharappel, a tutor employed by the University in subjects taught by Dr Anderson. The focus of these posts and tweets was an allegation that “Murdoch journalist fools Armenian Council with fake genocide threat”. In the posts Mr Tharappel is identified as having said “Kylar Loussikian … Armenian name right? ... traitor who wants a second Armenian genocide … stabbing Syria in the back”. Amongst other things, Dr Anderson posted “Murdoch press fabricates ‘genocide threat’ story in attempt to intimidate anti-war academics. Academic Jay Tharappel said Daily Telegraph Journalist Kylar Loussikian was a traitor to his Armenian ancestry, inviting a ‘second genocide’ on the Armenian people by attacking (on false pretexts) the Syrian Government, a historic protector of the Armenian people. The Murdoch journalist responded with a fabricated ‘genocide threat’ story”. A further tweet described United States Senator John McCain as “a key US war criminal”. These are referred to in the further amended statement of claim (FASOC) as the first comments: J [18]-[19].

58 On 19 May 2017, Dr Anderson wrote to Professor Jagose. The letter concerned allegations against Mr Tharappel and the investigation of those complaints (the first complaint): J [20].

59 On 30 May 2017 the University sent to Dr Anderson a letter signed by Professor Jagose containing allegations that in making the tweets and posts Dr Anderson breached the University’s Code of Conduct and Public Comments Policy (the first allegations). The letter directed Dr Anderson to refrain from “disclosing to, or communicating with, anyone, the contents of this letter, the Allegations or any information or documents relating to them, other than to members of your family (or support person), your professional adviser on the basis they provide you with an undertaking that they will comply with the above confidentiality direction or unless you are required to do so by law or with the prior written consent of the University”: J [21]-[23].

60 Dr Anderson published a further post and tweet in response to the first allegations on 30 May 2017, the focus of which was “University of Sydney threatens to sack me for criticising the deceitful war propaganda of News Ltd journalists, and for showing that the university’s latest guest John McCain is a key al Qaeda supporter” and that “University of Sydney policy says ‘Staff and affiliates are encouraged to engage in debate on matters of public importance’. Apparently not!”. These are referred to in the FASOC as the second comments: J [24]-[25]. He then sent an email on 31 May 2017 to the Department of Political Economy Board, Department of Political Economy Casual Tutors and Department of Political Economy Honorary Associates about “USyd management trying to gag anti-war academics” involving further details (the so-called 31 May email): J [26]. He then sent an email to Professor Jagose on 6 June 2017 asking her to recuse herself from dealing with the first allegations (the so-called second complaint and 6 June email): J [27]. Profesor Jagose responded on 8 June 2017: J [28]. The NTEIU supported Dr Anderson by letter to the University dated 9 June 2017: J [29]. On 23 June 2017 the University sent a letter to the NTEIU advising that the matters raised in Professor Jagose’s letter dated 30 May 2017 would be referred to Professor Garton: J [30].

61 On 26 June 2017, the University sent a letter from Professor Garton to Dr Anderson with the subject line “Further Allegations Relating to Your Conduct” (the so-called second allegations): J [31]. The second allegations related to the post and tweet on 30 May 2017, the 31 May email, and the 6 June email and said these constituted a breach of the University’s Code of Conduct and Public Comments Policy: J [32]. The letter also said:

Tim, I remind you that the matters raised in this letter, and in the 30 May Letter, are confidential, and I direct you to refrain from disclosing to, or communicating with, anyone, the contents of this letter, the 30 May Letter, the Allegations, the Further Allegations, or any information or documents relating to them, other than to members of your family (or support person), your professional adviser on the basis they provide you with an undertaking that they will comply with the above confidentiality direction or unless you are required to do so by law or with the prior written consent of the University…

I remind you that the University takes the need for confidentiality very seriously, and reserves the right to take disciplinary action if the confidentiality direction is not adhered to.

62 Dr Anderson responded to the first and second allegations on 5 July 2017: J [35].

63 On 2 August 2017, the University, by Professor Garton, sent to Dr Anderson a letter with the subject line “Re: Outcome – Allegations of Misconduct or Serious Misconduct”. This letter concluded that the various allegations which had been set out in the first and second allegations letters had been made out. Professor Garton was satisfied that disciplinary action was appropriate and that the letter should be treated as a written warning in relation to Dr Anderson’s conduct (the first warning): J [36].

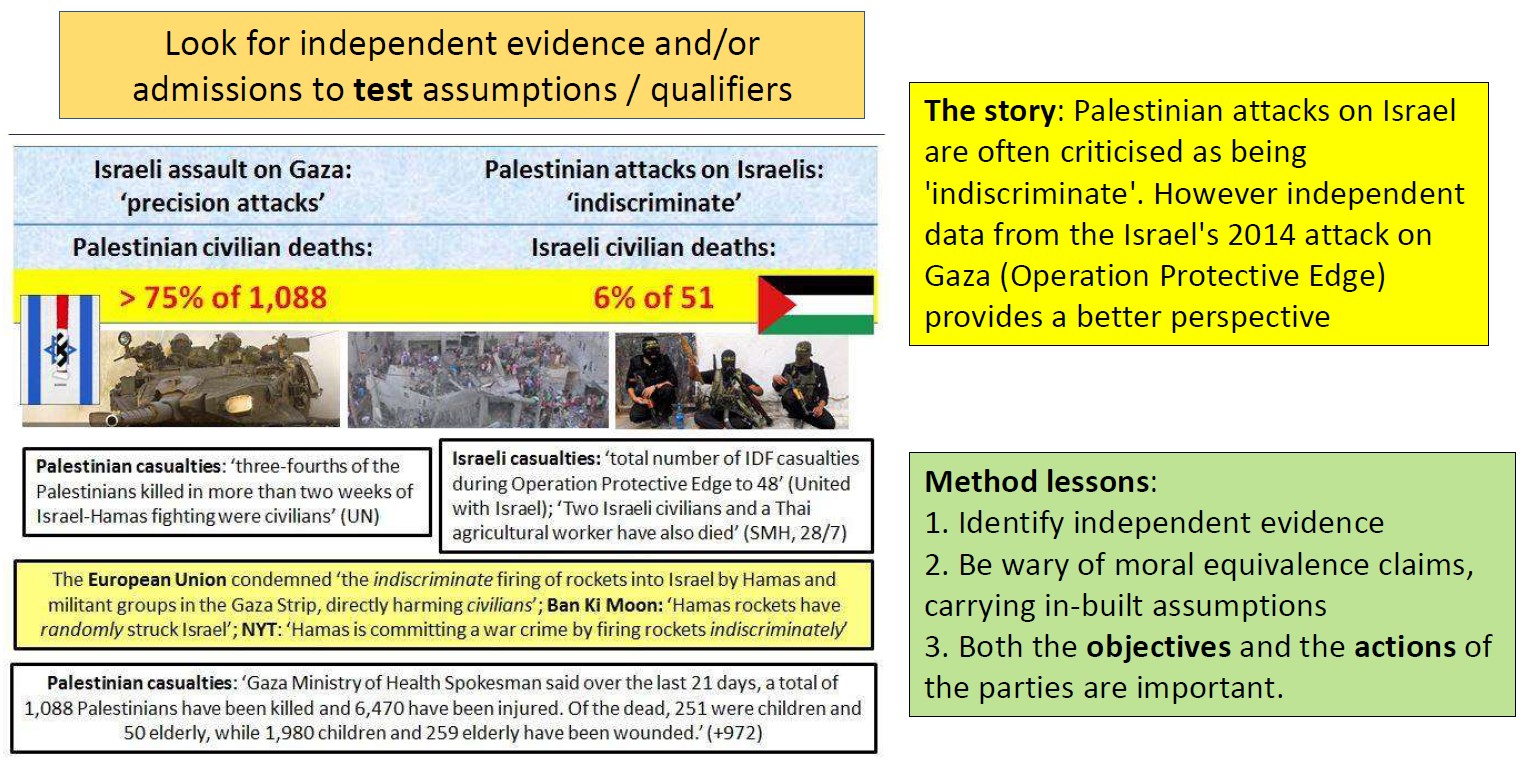

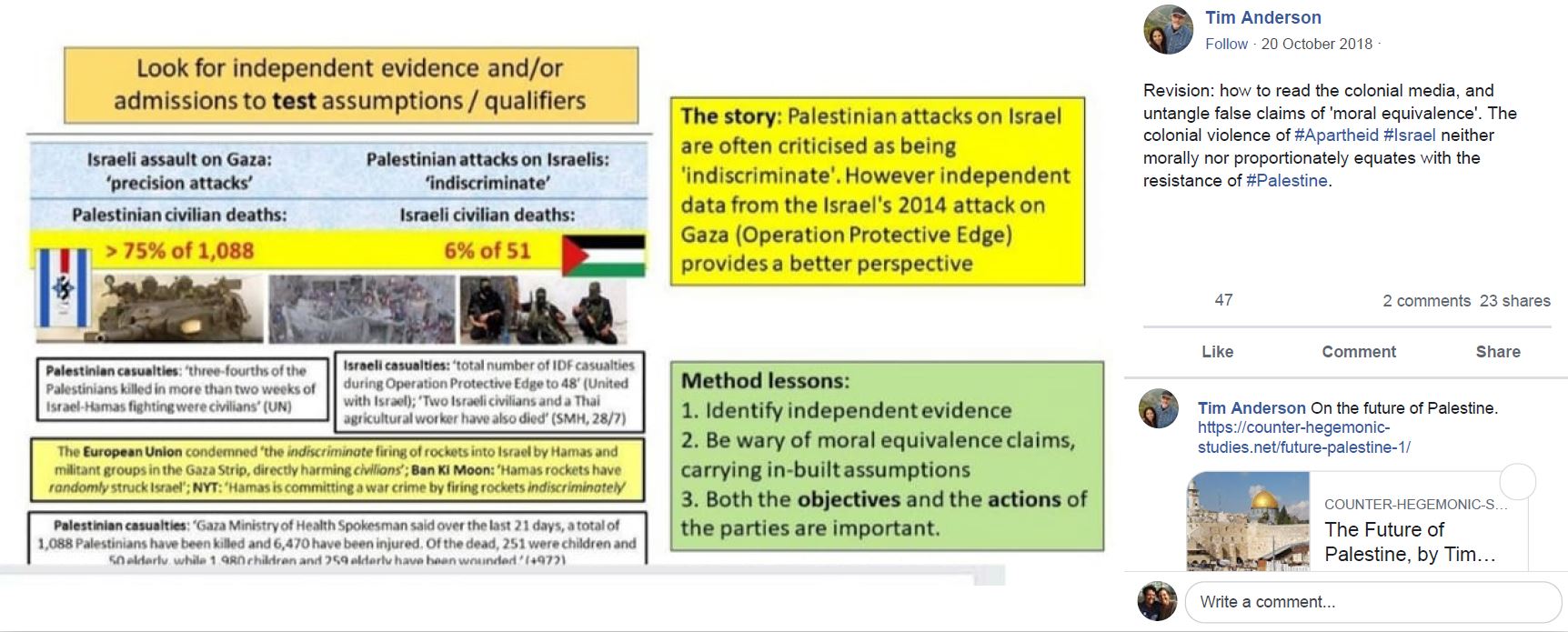

64 On 21 April 2018, Dr Anderson delivered a PowerPoint presentation at a seminar titled “Reading Controversies”, which he had organised (the PowerPoint presentation). The PowerPoint presentation contained an infographic which included what the parties described as an Israeli flag with a superimposed swastika (see the left hand side of the “infographic” in the paragraph below): J [39].

65 On 23 April 2018, Dr Anderson posted the slides from the PowerPoint presentation to his Facebook account, along with some comments. The infographic, described by the parties as the third comments, was as follows (J [41]):

66 On Sunday 22 July 2018, just before commencing annual leave, Dr Anderson posted on his Facebook account a photo referred to as the lunch photo (J [42]), shown below:

67 Mr Tharappel is second from the right. The patch on Mr Tharappel’s shirt which is in Arabic says “Death to Israel”. Other parts say “Curse the Jews” and “Victory to all Islam”: J [220].

68 Dr Anderson was on approved annual leave between 23 and 30 July 2018. Between 31 July 2018 and 2 December 2018, Dr Anderson was on approved special study period leave. Between 3 and 10 December 2018, Dr Anderson was on approved annual leave: J [44].

69 On 2 August 2018, 7NEWS Sydney posted a video news story by Channel 7 reporter Mr Bryan Seymour about the lunch photo, focussing on the badge on Mr Tharappel’s shirt and commenting on Dr Anderson. The story was titled “University student sparks outrage: A University of Sydney academic has outraged many in the Muslim and Jewish communities by wearing an offensive slogan”. Among other things, Mr Seymour described Dr Anderson and Mr Tharappel as “fervent supporters of … Kim Jong Un”: J [45].

70 On 3 August 2018, Dr Anderson:

(1) twice posted to his Facebook account:

Colonial media promotes ignorance, apartheid and war. Channel 7’s Bryan Seymour accuses Indian Australian student of ‘racism’ for siding with #Yemen and other Arab states against #ApartheidIsrael. Also lies about those in solidarity with #Korea #DPRK.

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=2248128551877932&id=108878629136279

(2) tweeted on his Twitter account:

Colonial media promotes ignorance, apartheid and war. Channel 7’s Bryan Seymour accuses Indian Australian student of ‘racism’ for siding with #Yemen and other Arab states against #ApartheidIsrael. Also lies about those in solidarity with #Korea #DPRK . [Link attached to 7NEWS video story]

71 These were referred to in the FASOC as the fourth comments: J [47].

72 On 3 August 2018, Dr Anderson received a letter from the University, signed by Professor Jagose, which formally directed Dr Anderson to remove the lunch photo and the fourth comments from his social media accounts: J [48]. The letter also said:

This letter is to be kept confidential and I especially require that you do not share this publicly or with any third party.

Should you not comply with the directions in this letter, I note that disciplinary action may be taken against you.

73 Dr Anderson responded on 4 August 2018 saying (J [49]):

I never respond favourably to secret demands and threats. You should know that you have no right to demand any censorship of my social communications. Your claim for secrecy of communications is also rejected.

74 Dr Anderson did not remove the lunch photo or the fourth comments: J [50].

75 On 10 August 2018, the University sent a letter from Professor Jagose to Dr Anderson with the subject line “Allegations Relating to Your Conduct”. These were referred to in the FASOC as the third allegations. The third allegations related to the lunch photo and fourth comments and Dr Anderson not having deleted the same: J [51].

76 On 15 August 2018, Dr Anderson made a written complaint to the University’s Director of Workplace Relations and Director of Safety, Health and Wellbeing making bullying and harassment allegations about the conduct of Professor Jagose (the so-called third complaint): J [53].

77 On 17 August 2018, Dr Anderson received an email from Michael Koziol, a journalist from Fairfax media about the University’s investigation of Dr Anderson’s conduct: J [54].

78 The same day Dr Anderson forwarded the email to Professor Jagose asking “Can i take it that someone in your team has provided information to journalists (see below) to smear me in the media?”: J [55].

79 On 19 August 2018, the Sydney Morning Herald published an article by Mr Koziol entitled “Sydney Uni lecturer investigated for defending ‘Death to Israel’ badge”: J [56].

80 On 20 August 2018, the University sent to Dr Anderson a letter signed by Professor Garton which stated that the “misconduct process” would be put on hold whilst Dr Anderson’s bullying complaint against Professor Jagose was considered: J [57].

81 On 22 August 2018, Dr Anderson wrote to the University’s Associate Director of Workplace Relations. This letter is described as the fourth complaint: J [58]-[59].

82 On 23 August 2018, Professor Garton sent an email to Dr Anderson denying anyone from the University had tried to “smear” Dr Anderson: J [60].

83 Dr Anderson responded on the same day saying “Dont [sic] be disingenuous. You know very well that that SMH story would not have run without that official statement”: J [61].

84 On 24 August 2018 the NTEIU sent a letter to the University to the effect that the University should not have disclosed that Dr Anderson was being investigated for misconduct: J [62].

85 On 8 September 2018, Dr Anderson sent a concerns notice under the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) to the University’s Vice Chancellor. This was described as the fifth complaint: J [63].

86 The University’s Vice Chancellor responded on 14 September 2018 denying any defamation: J [64].

87 On 8 October 2018, Professor Garton sent a letter to Dr Anderson saying that the investigation into his complaints of bullying and harassment by Professor Jagose was completed and it had been determined that Dr Anderson’s allegations could not be substantiated and that the “substance and fact of the investigation must be kept confidential”: J [65].

88 Dr Anderson responded on 8 October 2018 requesting a full copy of the investigation report and saying “I will disregard your claims for secrecy in correspondence”: J [66].

89 Professor Garton replied on 9 October 2018 saying (J [67]):

I reaffirm that you are directed not to publish or disclose confidential information or correspondence relating to the bullying investigation, the misconduct process, or any other confidential information. Any breach of this direction may result in disciplinary action against you.

90 Professor Garton sent Dr Anderson a letter on 19 October 2018 (the final warning) advising that he was satisfied that the misconduct allegations against Dr Anderson had been largely substantiated, referred to the first warning, and said (J [68]-[69]):

This letter constitutes a final warning that you must appropriately discharge your obligations pursuant to your contract of employment with the University, the Enterprise Agreement, the Code of Conduct and the Public Comment Policy going forward.

91 The letter referred to the PowerPoint presentation as posted on 23 April 2018 and said (J [70]):

Given the period of time which had elapsed from when you had made the post and when it was referred to the University, a decision was made not to include it in the allegations. In the circumstances, the University will not raise this post with you formally. However, in my view, a reasonable person would regard the superimposition of a cropped Swastika over the Israeli flag as offensive.

Please immediately add a disclaimer in any medium in which this post appears that the presentation is not connected in any way with the University of Sydney and remove any references to the University of Sydney from the relevant posts.

92 The letter referred to the lunch post (forming part of the allegations of misconduct), and said (J [71]):

In my view a reasonable person is likely to find the Patch worn by Mr Tharappel and posted by you to be offensive and/or derogatory. This allegation is substantiated.

93 The letter referred to the posts about Mr Seymour on 3 August 2018 saying (J [72]):

In my view, the statement made by you (and set out above) are, on any objective view, derogatory of Bryan Seymour and go beyond the expression of an opinion about the underlying issue.

…

This allegation is substantiated.

94 The letter referred to Dr Anderson’s refusal to comply with the direction given by Professor Jagose on 3 August 2018 to remove the lunch photo and the fourth comments from his social media accounts, and said (J [73]):

Professor Jagose provided a lawful and reasonable direction to you, as someone in a supervisory position relating to your employment, that you remove posts that she considered had the potential to be in breach of University’s expectation of employees under the Code of Conduct and Public Comment Policy. It was reasonable for her to issue that direction to you in circumstances where she had formed the view that the content of your posts was contrary to your obligations under the Code of Conduct and Public Comment Policy.

You have admitted that you refuse to comply with Professor Jagose’s direction.

Finding relating to Allegation 7

The Allegation is substantiated.

95 Dr Anderson stated in his affidavit that, after receiving the final warning, he removed “the University of Sydney” from the “about” details of his Facebook and Twitter accounts: J [74].

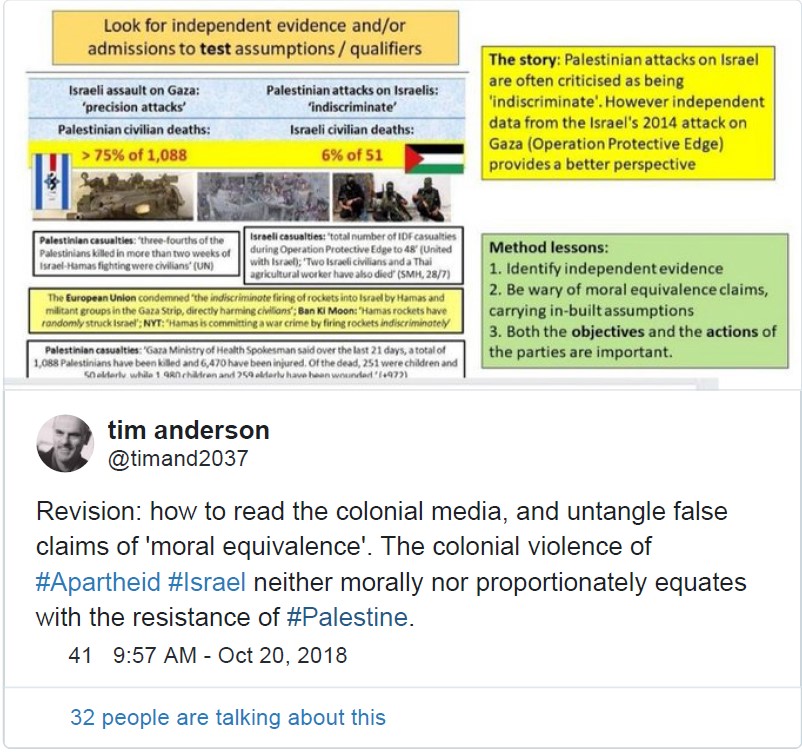

96 On 19 or 20 October 2018, Dr Anderson posted an image from the PowerPoint presentation and tweeted that image on his Twitter account. These were referred to in the FASOC as the fifth comments. The Facebook post was (J [76]):

97 The Twitter post was (J [77]):

98 On 26 October 2018, the University sent a letter to Dr Anderson with the subject line “Further Allegations Relating to Your Conduct”. The letter contained allegations that publication of the 19 or 20 October 2018 Facebook posts and Twitter tweets might constitute misconduct. These were referred to as the fourth allegations: J [79]. The letter said that the further allegations, if substantiated, would amount to “serious misconduct” and may justify the termination of Dr Anderson’s employment: J [81]. The letter included an enlarged image of the Israeli flag from the Facebook posts and Twitter tweets as follows:

99 Dr Anderson responded on 26 October 2018 (the so-called sixth complaint): J [83].

100 The University suspended Dr Anderson on 3 December 2018 informing him that the fourth allegations had been found to be substantiated, saying (J [88]):

I am satisfied that your conduct amounts to Serious Misconduct and is in breach of your obligations under the University of Sydney Enterprise Agreement 2018 - 2021 (Enterprise Agreement), your contract of employment, the Code of Conduct- Staff and Affiliates and the Public Comment Policy.

…

I am proposing that the appropriate Disciplinary Action is the termination of your employment with the University due to your Serious Misconduct, particularly in the context of previous warnings issued on 2 August 2017 and 19 October 2018 in respect of similar conduct.

You have the opportunity to have this proposed decision reviewed by a Review Committee in accordance with clause 460 of the Enterprise Agreement…

101 On 4 and 5 December 2018, Dr Anderson made posts and tweets to his Facebook and Twitter accounts: J [89]. Although not identified as such in the FASOC, these must be the so-called sixth comments referred to in paras 78, 79 and 80 of the FASOC. On 7 December 2018 the University sent a letter to Dr Anderson saying (J [89]):

I refer to my letter to you dated 3 December 2018 relating to the outcome of the further allegations about your conduct.

I have since become aware that on 4 December 2018 at approximately 12.55pm you made a post on your Facebook account (https://www.facebook.com/timand2037), as set out in Annexure A. The post refers to the proposal to terminate your employment, and then subsequently posts screenshots of the text of my 3 December 2018 letter to you (not including attachments/annexures) in the comments on that post.

I have also become aware that on 5 December 2018 at approximately 8.51pm you published a post on your Twitter account (https://twitter.com/timand2037), as set out in Annexure B. The post names the Fairfax media journalist who published a story commenting on your post and shows the statement you made on your Facebook account referred to above.

I consider your posts on social media, especially the fact that you posted my 3 December 2018 letter to you in full on social media as inappropriate and contrary to my previous statements that you are not to post University letters on social media.

I have confirmed in previous correspondence to you on 19 October 2018, and separate correspondence to the NTEU, that you are able to confirm the fact of the allegations more broadly, but not to disclose the substance of them. I have also confirmed that the contents of correspondence such as private and confidential University letters are not to be posted on social media.

In my letter to you dated 26 October 2018, I confirmed that the Allegations of misconduct against you are confidential and they were not to be discussed with anyone other than a support person, representative or personal adviser (such as a lawyer, doctor or counsellor) or disclosed in any manner or form on social media.

You were told that you “must not victimise or otherwise subject any person, to detrimental action as a consequence or that person raising, providing information about, or otherwise being involved in the resolution of a complaint, including the disciplinary process.” This includes showing the names of individuals involved in disciplinary processes, such as your managers and those in support functions at the University.

You were also informed that it is open to the University to “take disciplinary action against you if you breach confidentiality, or knowingly become involved in victimisation or other detrimental action.”

I understand that you have requested a review of the proposal to terminate your employment, as you are entitled to do. I respect your decision and will respect the outcome of that process.

Whilst that process is ongoing, the University will not take any further action relating to your disclosure of the letter on social media. However, the University reserves its rights to review this matter further after the review process has completed.

I confirm that you are directed to specifically not post this letter on social media or to disclose its contents more broadly, save for the letter or its contents being disclosed to a support person, representative or personal adviser (such as a lawyer, doctor or counsellor), or by either you or the University as part of the review of the proposal to terminate your employment.

102 On about 5 December 2018, Dr Anderson requested that a review committee review the proposed termination of his employment. A review committee was convened on 17 December 2018: J [90]. Following the making of submissions and a hearing the review committee published its findings on 8 February 2019. Two members of the review committee endorsed the termination of Dr Anderson’s employment and one did not: J [90]-[91].

103 The University terminated Dr Anderson’s employment on 11 February 2019: J [92].

5.3 The Enterprise Agreements

104 The 2013 and 2018 agreements are in the same terms, albeit with different clause numbers. Relevant provisions of the 2018 agreement include (J [95]-[98]):

DEFINITIONS

3 In this Agreement:

…

Code of Conduct means the University’s Code of Conduct - Staff and Affiliates or Research Code of Conduct, as amended or replaced from time to time.

…

Misconduct means conduct or behaviour of a kind which is unsatisfactory. Examples of conduct or behaviour which may constitute Misconduct include:

(a) a breach of a Code of Conduct (as defined in this clause); or

(b) a refusal or failure to carry out a lawful and reasonable instruction.

…

Serious Misconduct means:

(a) serious misbehaviour of a kind that constitutes a serious impediment to the carrying out of a staff member’s duties or to other staff carrying out their duties; or

(b) a serious dereliction of duties.

Examples of conduct which may constitute Serious Misconduct are:

(a) a serious breach of a Code of Conduct (as defined in this clause);

(b) theft;

(c) fraud;

(d) assault;

(e) serious or repeated bullying or harassment, including sexual harassment;

(f) persistent or repeated acts of Misconduct; or

(g) conviction of an offence that constitutes a serious impediment to the carrying out of a staff member’s duties.

…

RELATIONSHIP TO OTHER AGREEMENTS, AWARDS AND POLICIES

13 This Agreement is a closed and comprehensive agreement and wholly displaces any awards and agreements which, but for the operation of this Agreement, would apply.

14 Policies, guidelines, procedures and Codes of Conduct of the University, whether referred to in this Agreement or not, do not form part of this Agreement. The University will consult with the Joint Consultative Committee and through the University’s collegial processes in relation to the introduction or amendment of policies, guidelines, procedures and Codes of Conduct that have a significant and substantial impact on matters pertaining to the employment of staff under this Agreement, including for example, policies dealing with recruitment and selection, performance planning and development, performance management and academic promotion.

…

PART G: MANAGEMENT OF WORK AND PERFORMANCE

PERFORMANCE OF WORK

305 Staff may be directed by the University to carry out such functions and duties as are consistent with the nature of their appointment, classification/level and employment fraction, and are within their skill, capability and training and are without risks to health and safety. Other factors to be taken into account when assigning work will include:

(a) the importance of maintaining an appropriate balance between work and family life;

(b) provision of appropriate opportunities for career development;

(c) the working hours specified in this Agreement; and

(d) ensuring equity within each work unit.

WORKPLACE CONDUCT

306 Staff must comply with the Codes of Conduct (as defined in clause 3).

307 Workplace bullying is unacceptable behaviour and is defined as repeated, unreasonable behaviour directed towards a staff member or a group of staff that creates a risk to health and safety. It does not include reasonable management action or practices.

308 The University is committed to eliminating workplace bullying and to providing staff with information and training about this. This commitment is supported by the Bullying, Harassment and Discrimination Prevention Policy and the Bullying, Harassment and Discrimination Resolution Procedures, which provide a framework for managing any incidents of workplace bullying in a fair and timely manner. These policies will remain in force and will not be changed without consultation with the Unions through the normal process and through the Joint Consultative Committee, including consultation over the final form of the policy.

309 Staff must co-operate with the University and comply with all reasonable directions of the University directed at preventing, responding to or minimising the risk of workplace bullying.

…

312 Staff who want to make a complaint of bullying should do so in accordance with the Bullying, Harassment & Discrimination Resolution Procedures. In these circumstances, the University will appropriately deal with the complaint, including:

(a) conducting any preliminary assessment of alleged bullying in a timely manner;

(b) where it is determined by the University that an investigation is appropriate, an Investigator will be appointed by the University;

(c) taking reasonable steps to secure the safety of the complainant, the respondent and other impacted staff during the investigation and resolution; and

(d) if it is determined that bullying has occurred, the University will take reasonably practicable steps and actions to address the bullying.

313 Where a staff member does not accept the outcomes of a preliminary assessment or the actions taken under clause 312(d), they may have the matter referred to the Delegated Officer (Staffing) for a review.

314 Nothing in this Agreement prevents a staff member from applying to the Fair Work Commission at any time for Anti-Bullying orders under the Fair Work Act.

INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM

315 The Parties are committed to the protection and promotion of intellectual freedom, including the rights of:

(a) Academic staff to engage in the free and responsible pursuit of all aspects of knowledge and culture through independent research, and to the dissemination of the outcomes of research in discussion, in teaching, as publications and creative works and in public debate; and

(b) Academic, Professional and English Language Teaching staff to:

(i) participate in the representative institutions of governance within the University in accordance with the statutes, rules and terms of reference of the institutions;

(ii) express opinions about the operation of the University and higher education policy in general;

(iii) participate in professional and representative bodies, including Unions, and to engage in community service without fear of harassment, intimidation or unfair treatment in their employment; and

(iv) express unpopular or controversial views, provided that in doing so staff must not engage in harassment, vilification or intimidation.

316 The Parties will encourage and support transparency in the pursuit of intellectual freedom within its governing and administrative bodies, including through the ability to make protected disclosures in accordance with relevant legislation.

317 The Parties will uphold the principle and practice of intellectual freedom in accordance with the highest ethical, professional and legal standards.

…

MISCONDUCT AND SERIOUS MISCONDUCT

384 Where a staff member’s Supervisor or a relevant Delegate becomes aware of allegations that the staff member may have engaged in Misconduct or Serious Misconduct:

(a) The Supervisor or relevant Delegate may undertake or arrange such preliminary investigations or enquiries as they consider necessary to determine an appropriate course of action to deal with the matter;

(b) The Supervisor or relevant Delegate may, in the case of a less serious matters, seek to resolve the matter directly with the staff member concerned through guidance, counselling, warning, mediation or another form of dispute resolution;

(c) In cases other than those which are dealt with under clause 384(b), the staff member will be provided with allegations in sufficient detail to ensure that they have a reasonable opportunity to respond. The staff member will be given ten days to respond to the allegations.

(i) If the staff member admits the allegations in full, the relevant Delegate may take Disciplinary Action.

(ii) In other cases the relevant Delegate may:

(A) proceed to deal with the matter under clause 384(d); or

(B) if the Delegate considers it appropriate to do so, appoint an Investigator to investigate the allegations and report to the relevant Delegate on their findings of fact and any other matters requested by the relevant Delegate. The Investigator will determine the procedure to be followed in conducting the investigation, subject to the requirement that such procedure must allow the staff member concerned with a reasonable opportunity to respond to the allegations against them, including any new matters, or variations to the initial allegations resulting from the investigation process. The Investigator will provide a written report to the relevant Delegate and a copy to the staff member.

(d) Where the relevant Delegate is satisfied that a staff member has engaged in Misconduct or Serious Misconduct, the relevant Delegate may take Disciplinary Action against the staff member, provided that:

(i) before taking Disciplinary Action the relevant Delegate must be satisfied the staff member has been given a reasonable opportunity to respond to the allegations against them;

(ii) in any case of Disciplinary Action other than counselling, a direction to participate in mediation or an alternative form of dispute resolution or a written warning, the staff member must be given notice of the proposed Disciplinary Action and an opportunity to have the allegations examined by a Review Committee in accordance with clause 460, A request for a review must be made within five working days of receipt of notice of the proposed Disciplinary Action; and

(iii) a staff member’s employment may be terminated only if they have engaged in Serious Misconduct, as defined in clause 3 of this Agreement …

5.4 Code of Conduct

105 The University’s Code of Conduct includes these provisions (J [99]):

1 Principles

This Code has been formulated to provide a clear statement of the University’s expectations of its staff and affiliates in respect of their professional and personal conduct.

The Code reflects, and is intended both to advance the object of the University, namely the promotion of scholarship, research, free inquiry, the interaction of research and teaching, and academic excellence, as well as to secure the observance of its values of:

• responsibility and service through leadership in the community;

• quality and sustainability in meeting the needs of the University’s stakeholders;

• merit, equity and diversity in our student body;

• integrity, professionalism and collegiality in our staff; and

• lifelong relationship and friendship with our alumni.

These values must inform the conduct of staff and affiliates in upholding and advancing:

• freedom to pursue critical and open inquiry in a responsible manner;

• recognition of the importance of ideas and ideals;

• tolerance, honesty, respect, and ethical behaviour; and

• understanding the needs of those we serve.

…

4 Personal and Professional Behaviour

In performing their University duties and functions, the behaviour and conduct of staff and affiliates must be informed by the University’s object and its values and the principles enunciated in Part 1 above. All staff and affiliates must:

• maintain and develop knowledge and understanding of their area of expertise or professional field;

• exercise their best professional and ethical judgement and carry out their duties and functions with integrity and objectivity;

• act diligently and conscientiously;

• act fairly and reasonably, and treat students, staff, affiliates, visitors to the University and members of the public with respect, impartiality, courtesy and sensitivity;

• avoid conflicts of interest;