Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 142

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | EMPLOYSURE PTY LTD ACN 145 676 026 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be allowed.

2. The orders made on 1 and 23 October 2020 be set aside.

3. The parties confer and seek to agree the form of any declaration and injunction that ought be made in relation to the subject matter of the appeal, failing which they provide submissions limited to two pages on or before 20 August 2021.

4. The proceeding be remitted to the primary judge for hearing as to penalty and costs in respect of the proceedings at first instance.

5. The Respondent pay the Appellant’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

introduction

1 In this proceeding the appellant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), appeals from the judgment of a single judge of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1409 (TJ). The respondent, Employsure Pty Ltd, is a specialist workplace relations consultancy which advises employers and business owners across Australia in relation to the requirements of workplace relations and workplace health and safety legislation. It is a private company which has no affiliation with, or endorsement by, any government agency.

2 Through Google LLC, Employsure arranged the publication of online advertisements promoting its free employment-related advice service (Google Ads), which appeared on the screens of computers, tablets or smartphones in response to Google searches made by persons over the period from 10 August 2016 to 31 August 2018 (the relevant period). Employsure was aware that search terms such as “fair work commission”, “fair work Australia”, “fair work”, “fwc” and “fair work ombudsman” were frequently used by consumers for visits to the websites of major government agencies, the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Fair Work Commission. It selected those search terms as “keywords” in its search engine marketing strategy. Its use of such keywords meant that when a person making a Google search used search terms such as “fair work ombudsman”, “fair work Australia”, “fair work commission”, “Australia government fair work” or “Australia fair pay”, some of those terms appeared in the headline of the Google Ad. For example, when a person made a Google search using the term, “fair work ombudsman”, the headline of the Google Ad which appeared as the first search result said “Fair Work Ombudsman Help - Free 24/7 Employer Advice”. If users clicked on the hypertext in the Google Ads they were taken to a landing webpage operated by Employsure, and if they telephoned the number provided in some of the Google Ads, they reached an Employsure representative. None of the Google Ads, however, made any mention of Employsure.

3 In the proceeding below, the ACCC claimed that by the publication of seven Google Ads in the relevant period Employsure represented that it was, or was affiliated with and/or endorsed by, a government agency (the Government Affiliation Representations), and thereby engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, or conduct which was likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). It also claimed that by publication of the Google Ads Employsure made false or misleading representations that its services were of a particular standard or quality in contravention of s 29(1)(b) of the ACL, and that it had government sponsorship or approval in contravention of s 29(1)(h) of the ACL.

4 The primary judge found that none of the Google Ads conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations to the class of persons who were the target audience for the advertisements, being business owners who are employers and who search for employment-related advice on the internet. On that basis his Honour dismissed the ACCC’s claims that Employsure’s conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18, and that Employsure made false or misleading representations in contravention of ss 29(1)(b) and (h).

5 The ACCC now appeals against those findings in respect of six of the seven Google Ads considered below. The central issue in the appeal is whether the learned primary judge erred in finding that the six Google Ads were not misleading or deceptive or likely to be so, nor false or misleading. That finding was essentially based on his Honour’s conclusion that, viewed through the prism of an ordinary or reasonable member of the target audience of the advertisements, none of the Google Ads conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations.

6 For the reasons we explain, we respectfully consider the learned primary judge erred in failing to find that by publication of the Google Ads, Employsure conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations to the ordinary or reasonable member of the relevant class, which constituted misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct which was likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18, and the making of false and misleading representations in contravention of s 29(1)(b) and (h).

7 Accordingly we have set aside the orders of the primary judge to dismiss the originating application and for the ACCC to pay the costs of the proceeding below. We have directed the parties to confer to seek to agree the form of any declaration and injunction that ought be made in relation to the subject matter of the appeal, failing which they must provide submissions limited to two pages on or before 20 August 2021. The matter shall then be remitted to the primary judge for decision in relation to the application for pecuniary penalties for the contraventions of ss 29(1)(b) and (h) and the costs of the proceeding below.

The Facts

8 The following is drawn from the Statement of Agreed Facts filed by the parties in the proceeding below, from some of the unchallenged factual findings of the primary judge, and from some evidence which is uncontentious as between the parties.

The Google Search Engine

9 The Google search engine allows users to search for information on the internet by entering terms into a browser window and pressing “Enter” or clicking on a button marked “Google Search”.

10 From about 2000, in addition to “organic” search results, “paid” search results or “Google Ads” started to be displayed in Google search result lists. From at least early 2015, a Google search could produce both “organic” search results and “paid” search results.

Organic search results

11 “Organic” search results are links to webpages that do not require any payments to be made to Google.

12 Organic search results are ranked by Google using a number of proprietary algorithms, which are subject to regular modification by Google (Google Organic Algorithms). The Google Organic Algorithms are maintained and updated by Google and are not publicly available. The overall purpose of the ranking is to produce results that may be relevant to the search terms entered by the user.

13 Whether or not a webpage link is displayed as an organic search result in response to a user search is determined by the Google Organic Algorithms, which accounts for a range of factors, including, for example:

(a) the extent to which there is a “match” between the search terms used and the content of a given website, as assessed by the Google Organic Algorithms; and

(b) the number and types of other websites that are hyperlinked to the relevant webpage, as assessed by the Google Organic Algorithms.

14 Below is an example of an organic search result which appeared in response to a search conducted on 10 July 2019 using the search term “buy property melbourne”:

15 Organic search results typically include the following features, as demonstrated in the example set out above:

(a) a headline that incorporates a link to a webpage (in blue hypertext);

(b) an address (or URL) of the webpage to which the headline links (in green text); and

(c) a description of what the page is about (in grey text).

Paid search results (Google Ads)

16 Sometimes, in addition to the display of organic search results, one or more paid search results may also appear on the search results page.

17 “Paid” search results (or Google Ads) are advertisements that are created by, or at the direction of, advertisers using a platform provided by Google. Advertisers who use this platform are required to pay Google upon certain actions being taken by the internet user.

18 Paid search results are displayed in addition to the organic search results, generally above the organic results. Historically, paid search results were also displayed beside the organic results; however, starting in early 2016, Google commenced phasing out the display of paid search results on the right side of the page beside the organic search results.

19 The process of producing paid search results on a webpage is not determined by the Google Organic Algorithms. Rather, the display and location of a paid search result is determined by other algorithms used for Google’s advertising service (Google Ads Algorithms).

20 The table below sets out information about how paid search results may have been displayed from at least early 2015 to at least the end of 2018. However, the way a paid search result appears to a user can change depending on a number of factors including, for example, the browser (e.g. Internet Explorer, Firefox or Google Chrome) or device (e.g. personal computer, tablet or smart phone) that was used to conduct the search.

Period | Location of paid search result | Display of paid search result |

At least 2015 and to around April 2016 | Often, but not always, appeared on the top, bottom or on the right-hand side of the search results page | Typically marked by a yellow box underneath the headlines in which the word “Ad” appeared in white |

Around April 2016 to around February 2017 | Often, but not always, appeared on the top or bottom of the search results page | Typically marked by a green box underneath the headlines in which the word “Ad’ appeared in white |

Around February 2017 to at least the end of 2018 | Often, but not always, appeared on the top or bottom of the search results page | Typically marked by a white box underneath the headlines, with a green border in which the word “Ad” appeared in green |

21 From at least early 2015, a paid search result has consisted of three elements, as required by Google, and which are populated by, or at the direction of, the advertiser (emphasis added). These elements are demonstrated in the paid search result below (which appeared in response to a search on 10 July 2019 using the search term “buy property melbourne”) and comprise:

(a) a “headline 1” (“Property Buyers Melbourne” in the example below) and a “headline 2” (“Independant [sic] Advice” in the example below), which incorporates a single link to a webpage (in blue hypertext);

(b) the display URL (or URL) of the webpage to which the headline links (in green text) (this is sometimes different to the actual URL for the webpage to which the paid search result links and not the full URL); and

(c) the description (in grey text – sometimes referred to as the “advertising text” or “ad copy”).

22 When the searcher clicks on a paid search result, he or she is taken to a website or “landing page”.

23 A “landing page” is the page of a website that a searcher “lands” on when they click on a Google search result (whether an organic search result or Google Ad). During the period from 2015 to 2018, Google recommended that a landing page featured what was advertised in the Google Ad. Sometimes advertisers create bespoke “landing pages”, which exist separately from their website, and which feature the particular product or service presented in the Google Ad. “Landing pages” otherwise operate in the same way as other websites.

Google Ads service

24 Google provides advertisers with access to the Google Ads service by creating a Google Ads account.

25 An advertiser’s Google Ads account allows the advertiser to create and change their ad copy, and monitor the performance of their paid search results.

26 An advertiser using a Google Ads account to create a paid search result is able to request or propose the content of the headlines, the address of the webpage to which the headline links, and the advertising text.

27 A paid search result may display differently on a computer screen, as compared with how it displays on a smartphone.

28 Advertisers using Google Ads pay Google based on different measures (at the election of the advertiser), for example each time a user of the Google search engine clicks on the advertiser’s paid search result. This is known as “pay-per-click”.

29 Advertisers can set up “ad groups” and “campaigns” through their Google Ads account. An ad group contains a group of advertisements which target a shared set of keywords. For example, when marketing for a pet shop, there may be an ad group for “puppies” and another ad group for “kittens”. Each ad group will then contain a group of keywords (for example, in the case of “puppies” the keywords might be “buy puppy”, “puppies Sydney” and “pet shop puppy”).

30 Each campaign is made of one or more ad groups (in the example in the preceding paragraph the campaign would relate to the pet shop). The ad groups within a campaign generally share a budget, location and other parameter settings.

31 The default for a campaign is to run indefinitely. Campaigns can be ended at any time, and can be paused, resumed or removed. Advertisers can run multiple campaigns at the same time. By way of example, an advertiser (for example, a furniture retailer) may run different campaigns for different products (for example, one campaign for tables and another campaign for chairs).

Keywords for paid search results

32 An advertiser can specify one or more keywords corresponding to each of its paid search results in the advertiser’s Google Ads account. This is the first step in creating ad copy, ad groups or campaigns. That is, when creating a paid search result, ad group or campaign in a Google Ads account, an advertiser will be prompted to select its keywords first, before creating ad copy.

33 A “keyword” is a word or series of words that are selected by an advertiser on the basis that they relate to the search terms used by an internet user. A paid search result is more likely to display when the keywords that are associated with the paid search result are more relevant to terms in fact used by the searcher. More than one advertiser can specify the same keyword in an ad group or campaign.

34 Keywords can also contain a series of words that represent longer, specific phrases for which a targeted audience might search.

35 Advertisers can add, remove or change the keywords in their ad groups and campaigns at any time. Google also recommends keywords to any advertiser who has a Google Ads account.

36 When keywords for a paid search result are entered into Google Ads, the advertiser can choose 5 types of keyword settings. These are known as “match type” settings.

37 Match type settings determine how the search term used by the searcher must “match” the keyword selected by the advertiser. The match types are:

(a) exact match: an exact match allows an advertisement to appear only when a search term is entered which matches or closely matches the keyword;

(b) phrase match: a phrase match allows an advertisement to appear when the search term includes the exact phrase selected by the advertiser or close variations of it;

(c) broad match: a broad match allows an advertisement to appear when a search term includes the keyword or a variation of the keyword, including synonyms and misspellings;

(d) broad match modifier: a broad match modifier allows an advertisement to appear when the search term includes the keyword or a variation of it in any order, including synonyms; and

(e) negative match: a negative match enables advertisers to prevent their advertisements being displayed when a particular search term is used.

The Google Auction

38 When a searcher enters search terms into the Google search engine that match the keyword or keywords included in an advertiser’s keywords list, an “auction” is triggered. This involves the Google Ads Algorithms.

39 The Google Ads Algorithms make an almost instantaneous calculation that resolves the “auction” and determines which paid search results will appear in the search results, in which order they are shown, and how much Google will charge the advertiser whose paid search results are displayed (if and when the searcher clicks on them, if the advertiser has selected the pay-per-click payment method).

40 The “winners” of the auction are judged by Google’s process of ranking advertisements. This is referred to by Google as “Ad Rank”.

41 The exact formula that Google uses to determine top placement of paid search results is not publicly available. Ad Rank takes into account at least the following five features in determining whether a given Google Ad is eligible, whether it may appear in response to a particular search and, if so, where it may appear in the list of paid search results:

(a) the maximum amount that the advertiser is willing to pay for a click on their paid search result;

(b) the quality of an advertiser’s paid search advertisement and landing page, including how useful and relevant the advertisement, keywords and linked website are to the searcher (this is sometimes referred to as a “quality score”);

(c) the Ad Rank thresholds, which are the minimum bids set by Google for an advertisement to show in a particular position;

(d) the context of the searcher’s search, including the search terms used, the searcher’s location, the type of device they are using, the time of the search, the nature of the search terms and the relative quality of other Google advertisements and search results that are bidding in that “auction”; and

(e) the expected impact from the advertisement extensions and the format of the advertisement (such as, the inclusion of phone numbers and other links to specific webpages).

42 The interaction between these factors will affect the Ad Rank of a given advertisement. For example, even if an advertiser is prepared to pay a large amount for a click on their advertisement, the Google Ad may not appear if it does not have a sufficient quality score (and whether the Google Ad will in fact appear, and if so where it appears, ultimately depends on all of the factors set out above).

43 During the period from 2015 to 2018, the higher the quality score for a keyword, the less an advertiser may have had to pay for a given ad position. Conversely, if a keyword had a poor quality score, the advertiser may have had to pay more for a given ad position.

44 Since the auction process is repeated for every search on Google, each auction can have potentially different results depending on the competition at that particular moment in time. That is, internet users may see search result lists with different Google Ads displayed, and in different orders, in response to the same search.

45 An advertiser can seek to improve the number of impressions of a given paid search result by:

(a) adding negative keywords to an ad group keyword list;

(b) optimising the ad copy text (for example by including in the ad copy keywords that may have been used in the internet user’s search terms) to attempt to improve the relevance of the paid search result; and

(c) amending or optimising the content and coding of the landing page (such as by including key terms that would be relevant to the target audience on both the webpage and in its URL) to attempt to improve the relevance of the paid search result and landing page.

Dynamic keyword insertion

46 An advertiser can further set up “dynamic keyword insertion”, which is a feature of Google Ads that dynamically updates the displayed advertisement text to include one or more of the keywords that were included in a searcher’s search terms.

47 To use this feature, the advertiser can include a code within their ad copy (for example, {KeyWord: melbourne property}).

48 If a searcher uses one of the keywords in their search, Google Ads automatically replaces the code with the keyword that was included in the searcher’s search terms. This means that the paid search advertisement may appear differently to searchers depending on the search terms they use.

The impugned Google Ads

49 Each of the Google Ads is a paid search result, being an advertisement created by or at the direction of Employsure, using the platform provided by Google.

Google Ad 1

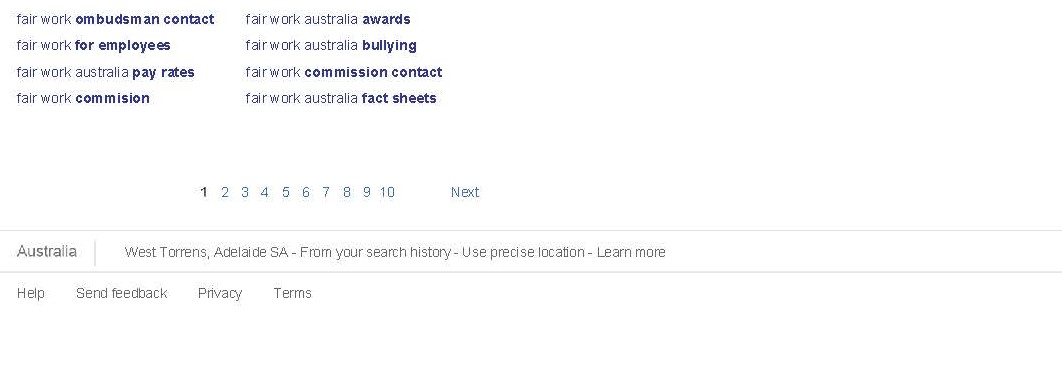

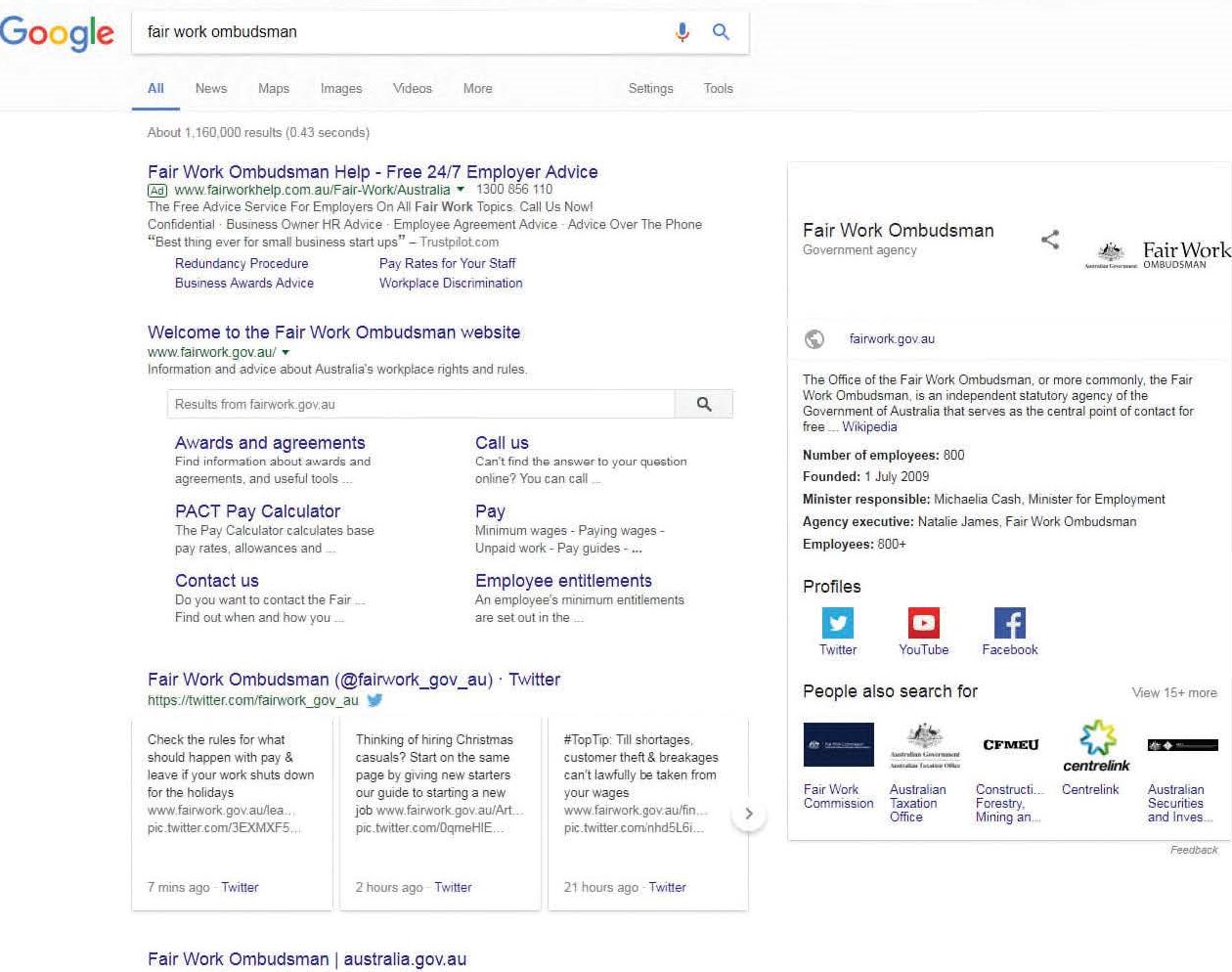

50 Google Ad 1was published during the period from 27 August 2016 to 12 April 2018 when a person made a Google search using the search terms “fair work ombudsman” (at TJ [12]). An image of Google Ad 1 is set out below.

51 While the way in which Google Ad 1 appeared in relation to other search results may have been somewhat different on the screens of computers, tablets or smartphones, and might have differed somewhat as between different searches because of Google’s algorithms, it is uncontentious that during the relevant period it appeared as the first search result and in the context of a page of search results, an image of which is displayed in Schedule 1 to these reasons.

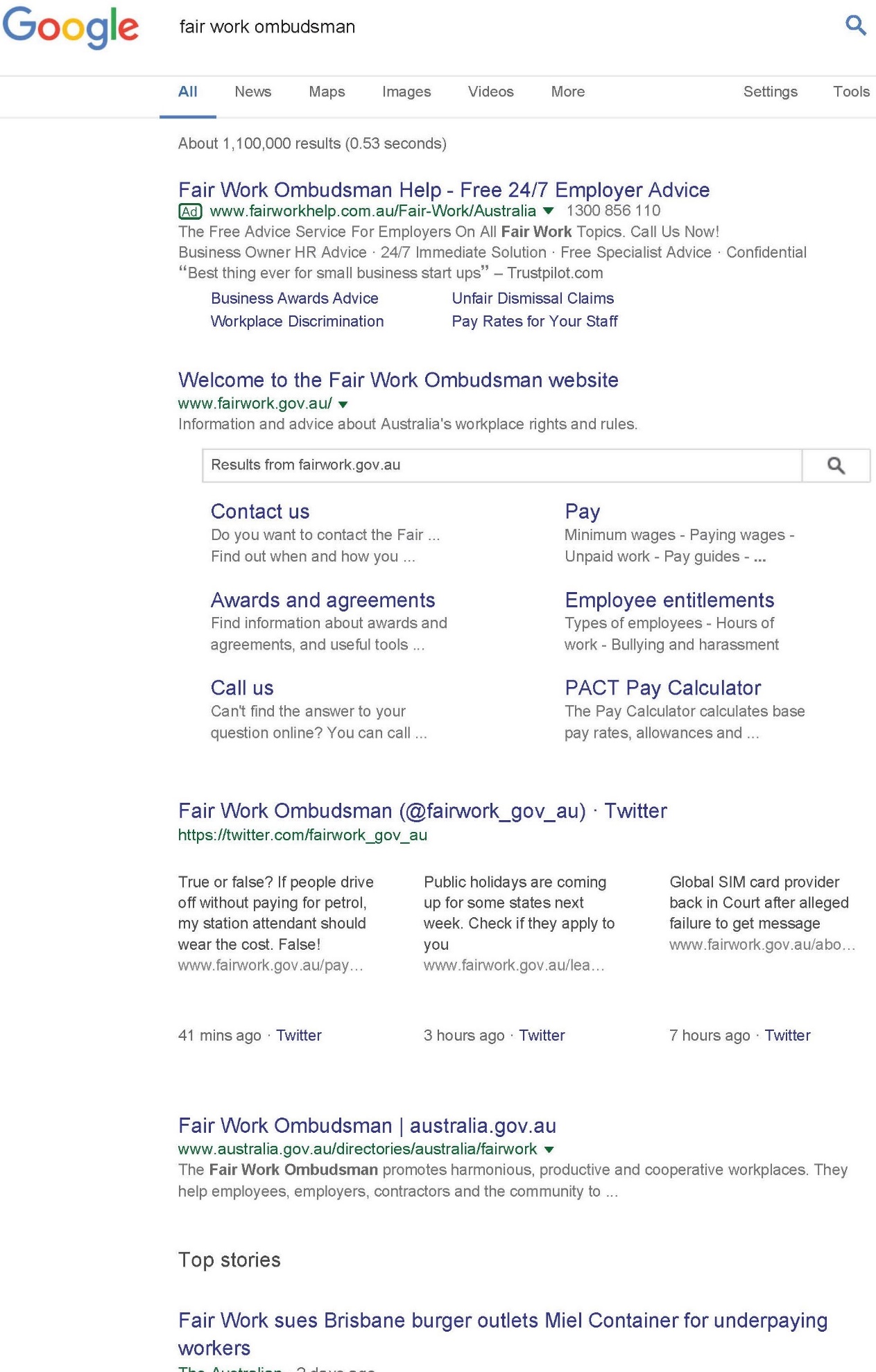

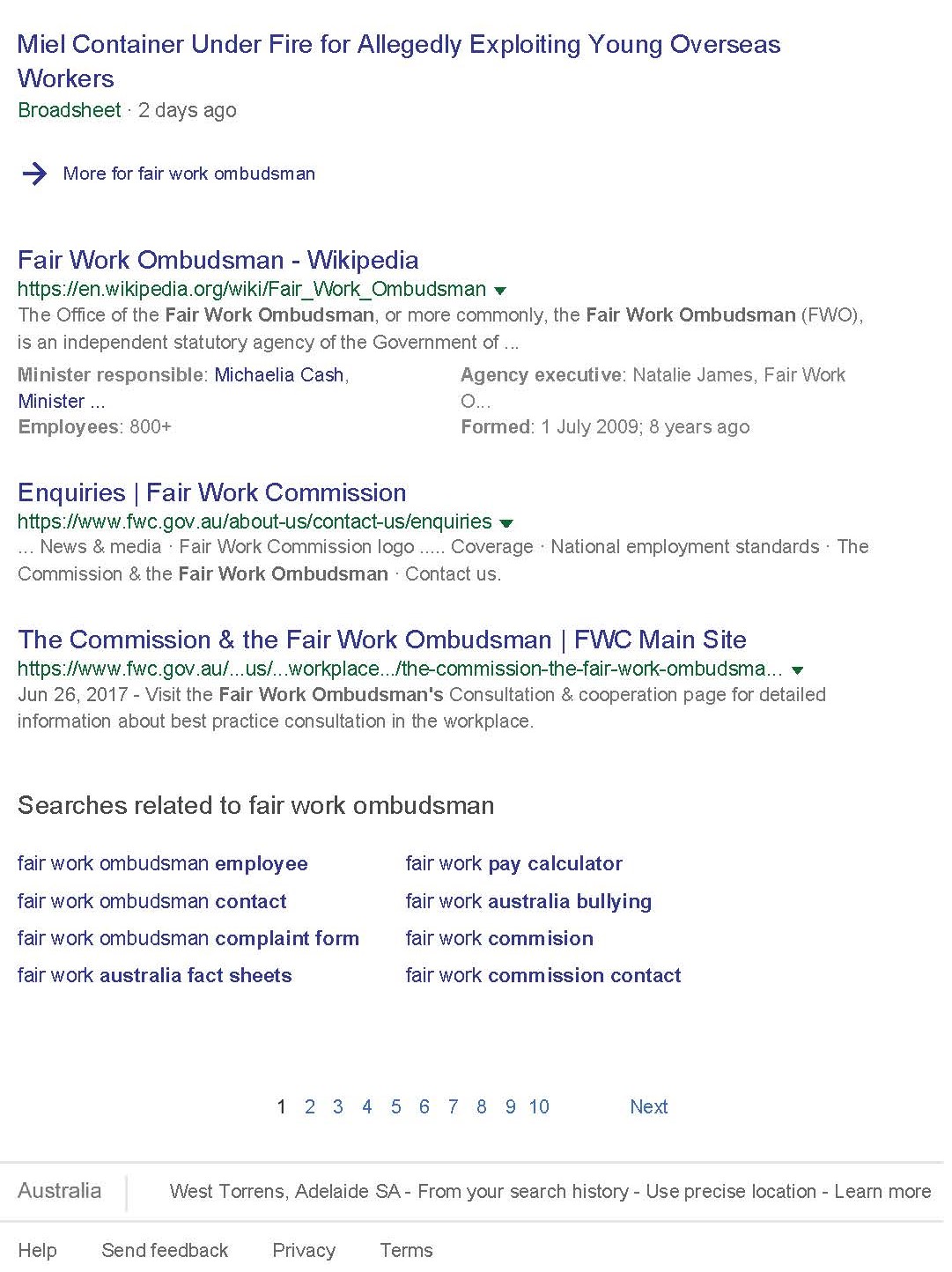

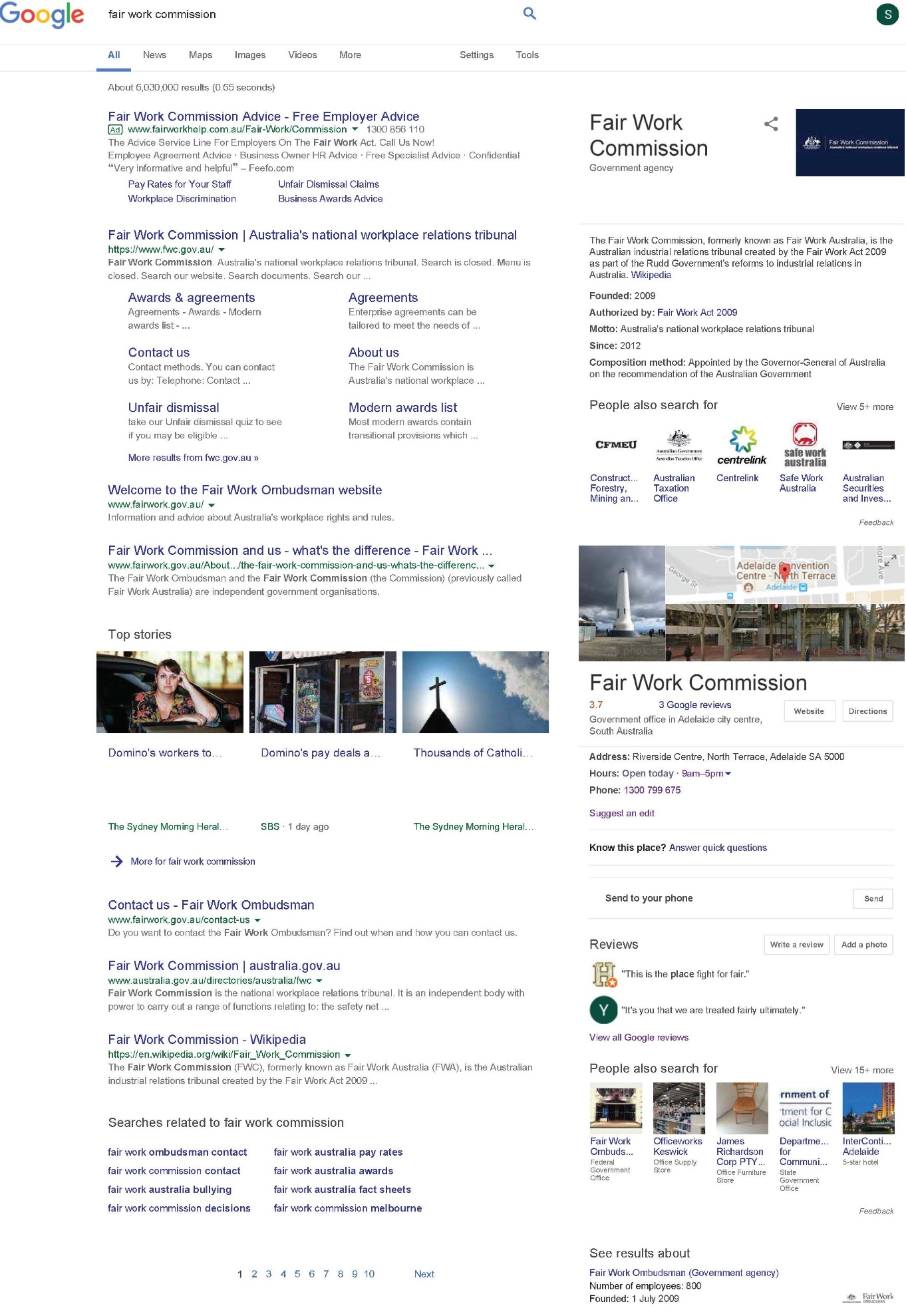

Google Ad 2

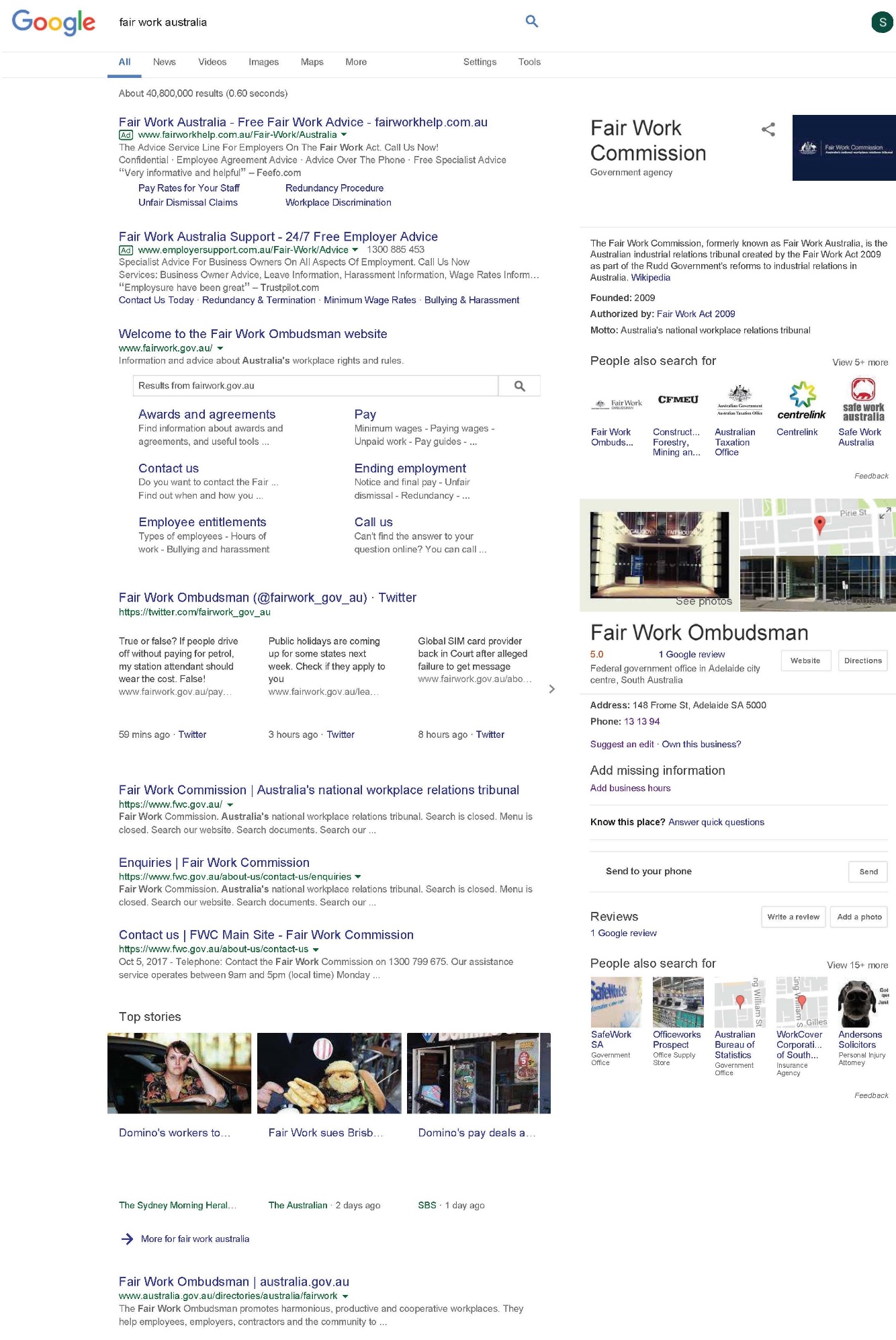

52 Google Ad 2 was published during the period from 10 August 2016 to 23 April 2018 when a person made a Google search using the search terms “fair work australia” (at TJ [13]). An image of Google Ad 2 is set out below.

53 With the same proviso as to the appearance of the advertisement on different devices and with different searches, it is uncontentious that during the relevant period Google Ad 2 appeared as the first search result and in the context of a page of search results, an image of which is displayed in Schedule 2.

Google Ad 3

54 Google Ad 3 was published during the period from 1 February 2017 to 30 April 2018 when a person made a Google search using the search terms “fair work commission” (at TJ [14]). An image of Google Ad 3 is set out below.

55 With the same proviso, it is uncontentious that during the relevant period Google Ad 3 appeared as the first search result and in the context of a page of search results, an image of which is displayed in Schedule 3.

Google Ad 4

56 Google Ad 4 was published during the period from 31 August 2017 to 31 August 2018 when a person made a Google search using the search terms “fair work ombudsman” (at TJ [15]). An image of Google Ad 4 is set out below.

57 With the same proviso, it is uncontentious that during the relevant period Google Ad 4 appeared as the first search result and in the context of a page of search results, an image of which is displayed in Schedule 4.

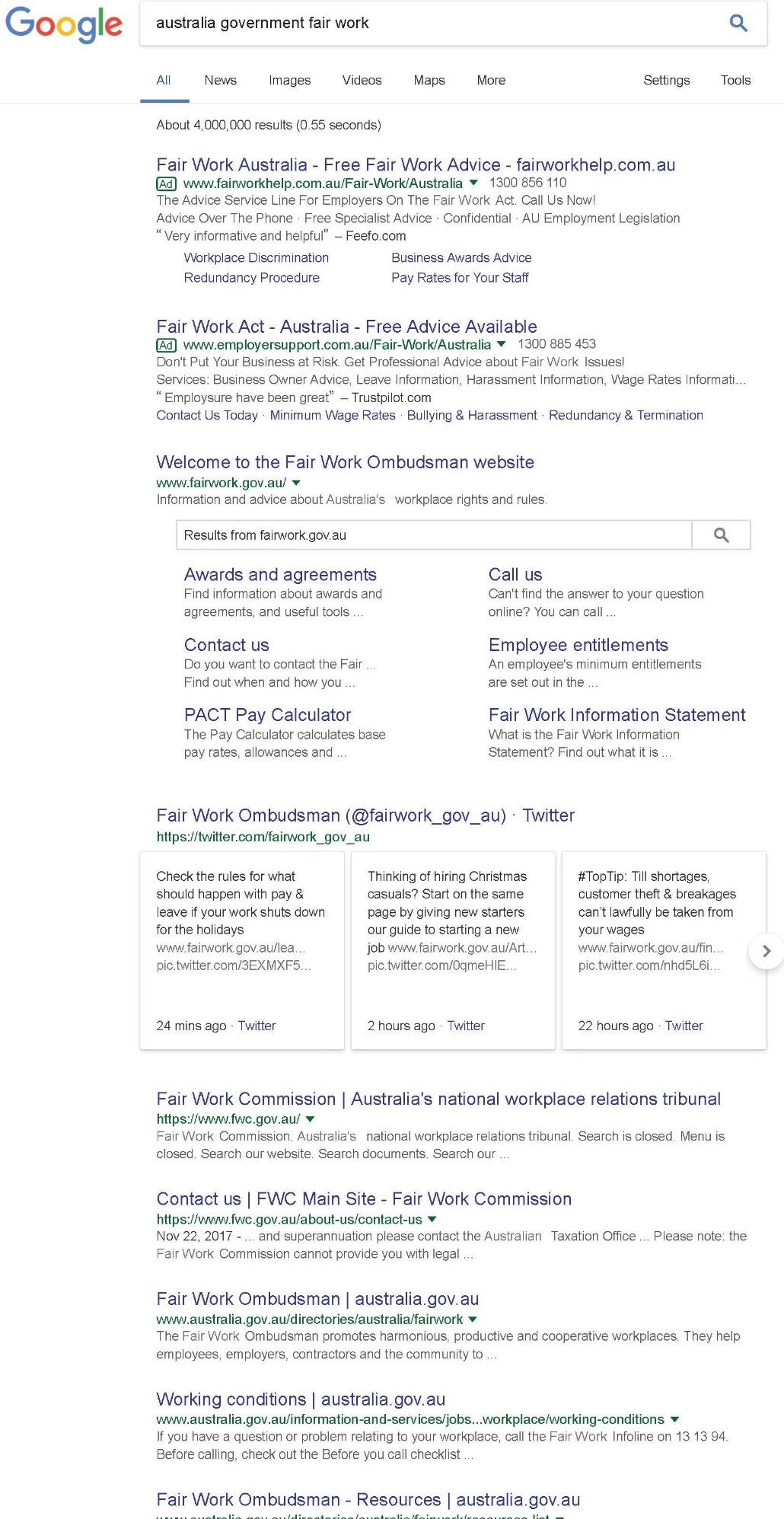

Google Ad 5

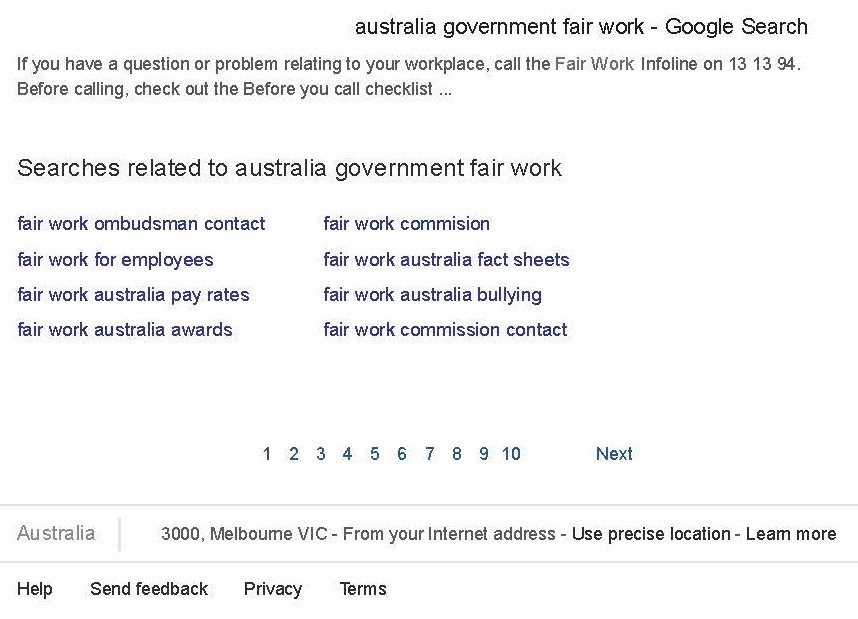

58 Google Ad 5 was published during the period from 2 January 2017 to 9 August 2018 when a person made a Google search using the search terms “australia government fair work” (at TJ [16]). An image of Google Ad 5 is set out below.

59 With the same proviso, it is uncontentious that during the relevant period Google Ad 5 appeared as the first search result and in the context of a page of search results, an image of which is displayed in Schedule 5.

Google Ad 6

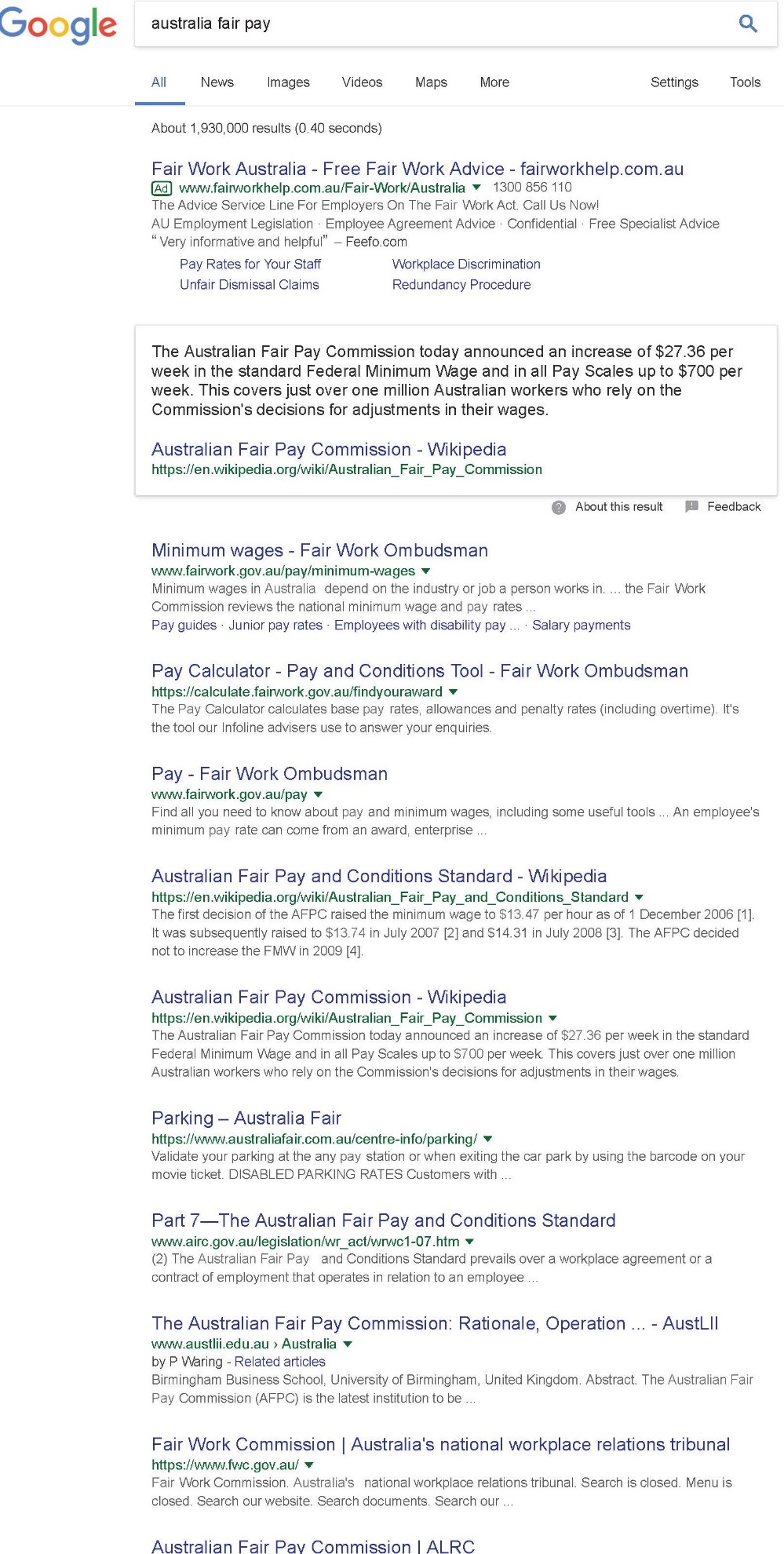

60 Google Ad 6 was published during the period from 2 January 2017 to 9 April 2018 when a person made a Google search using the search terms “australia fair pay” (at TJ [17]). An image of Google Ad 6 is set out below.

61 With the same proviso, it is uncontentious that during the relevant period Google Ad 6 appeared as the first search result and in the context of a page of search results, an image of which is displayed in Schedule 6.

62 In the relevant period:

(a) Employsure was aware of certain search terms (including “fair work commission”, “fair work Australia”, “fair work”, “fwc” and “fair work ombudsman”) being used frequently by consumers for on-line visits to the websites of the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Fair Work Commission, each being a major government agency dealing with employment related matters; and

(b) it selected those search terms as “keywords” in its search engine marketing strategy (at TJ [294]).

63 In doing so Employsure was not deliberately trying to lure people away from the services offered by government agencies such as the Fair Work Ombudsman or the Fair Work Commission, but instead was trying to have its Google Ads displayed to the people to whom it wished to direct its advertising, being prospective customers who were business owners who may have employment-related issues (at TJ [295]).

The primary judgment

The claims in the proceeding

64 Before the primary judge the ACCC advanced five claims. It alleged that Employsure:

(a) through the publication of seven Google Ads over the relevant period that conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations:

(i) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct which was likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL; and

(ii) made false or misleading representations that its services were of a particular standard or quality in contravention of s 29(1)(b) of the ACL, and that it had government sponsorship or approval in contravention of s 29(1)(h).

(b) engaged in misleading conduct or conduct which was liable to mislead in contravention of ss 18(1) and 34 of the ACL by using keywords associated with government agencies as part of the design of its Google Ads campaign (the Keywords Design case);

(c) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct or conduct which was liable to mislead and/or made false or misleading representations in contravention of ss 18(1), 29(1)(b) and 34 of the ACL by representing that Employsure provided a free advice helpline, which consumers could call to receive advice free of charge, where the primary purpose of the free advice telephone line was to secure marketing leads and book face to face meetings to sell its advisory services;

(d) engaged in unconscionable conduct in contravention of s 21 of the ACL in its dealings with three of its customers; and

(e) included unfair contract terms in three versions of its standard form contract in contravention of ss 23 and 24 of the ACL.

65 The primary judge dismissed each of the ACCC’s claims. Only the first claim is the subject of appeal, and then in respect of six of the seven Google Ads impugned below.

66 It is therefore unnecessary to consider the primary judgment insofar as it deals with the other four dismissed claims or with the seventh Google Ad in the first claim.

Employsure’s business

67 The primary judge found that Employsure is a specialist workplace relations consultancy which advises employers and business owners regarding the requirements of workplace relations and work health and safety legislation and provides products and services to over 20,000 employers across Australia. Those services included reviewing client documentation relating to workplace relations and work health and safety compliance, providing a 24 hour advice helpline and representing clients in courts and tribunals if they became involved in formal proceedings (at TJ [1]). Its business model is to require employers to pay a fixed fee subscription, as opposed to paying a fee for service, and then be entitled to access Employsure’s products and services as required. The subscription fee is not affected by the volume of work which, as it eventuates, a particular employer requires from Employsure (at TJ [2]).

68 The majority of Employsure’s client base are small business owners who employ staff, although Employsure also has several large clients (at TJ [3]).

69 Employsure offers on-site consultancy services as required, including staff training, management of disciplinary processes and risk reviews, as well as an initial review of a client’s work health and safety practices (which Employsure calls a “Safe Check Review”) and a review of a client’s workplace relations practices (which Employsure calls a “Wage Check and Contract Check”). These particular services are generally offered by Employsure to its clients on payment of an additional fee, although sometimes they may be provided gratuitously as part of the negotiations of the total subscription fee (at TJ [4]).

70 Where a prospective client or interested person telephones Employsure, the calls are received by Employsure’s business sales consultants. Sometimes these calls involve the sales consultant providing free advice to the caller. If the caller is, or may be, interested in acquiring Employsure’s services, there is a procedure whereby the sales consultant offers to arrange a face-to-face meeting with one of Employsure’s business development managers. Where that opportunity is taken up, the business development manager normally provides the person with additional advice, as well as explaining Employsure’s services and providing an obligation free quote. Some clients enter into a formal agreement with Employsure at this initial meeting or shortly thereafter (at TJ [5]).

The Google Ads

71 The primary judge set out the relevant facts showing the publication of each of the impugned Google Ads together with images of each advertisement (at TJ [12]-[17]). The fact that Employsure arranged the publication of the Google Ads, the contents of the advertisements, and the context in which the advertisements appeared on the pages of search results, is not contentious in the appeal. We have already set out images of the Google Ads, together with the context in which they appeared, and need not do so again.

The relevant principles

72 His Honour set out the applicable principles in relation to conduct which is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL (at TJ [236]-[244]) and in relation to false or misleading representations in contravention of s 29(1)(b) and (h) of the ACL (at TJ [245]-[249]).

73 The ACCC does not contend that the primary judge misstated the principles except to the extent that his Honour said (at TJ [282]) that it was necessary for the ACCC to establish that each of the Google Ads conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations to a “not insignificant number” of ordinary or reasonable members of the class. We later deal with the primary judge’s reference to that purported test, but otherwise need not reiterate his Honour’s statement of the relevant principles.

The relevant class or target audience of the Google Ads

74 The ACCC submitted before the primary judge that the Google Ads were directed at members of the public who search for employment-related advice on the internet; this class included business owners but was not confined to them. His Honour found that the relevant class was a narrower one, being “business owners who are employers and who search for employment-related advice on the internet” (at TJ [259]). That finding is not challenged in the appeal. For ease of reference we will call the members of the class “business owners”.

Whether the Google Ads are misleading or deceptive

75 The primary judge accepted, and it is uncontentious, that the relevant context in which a statement is to be viewed in assessing whether it is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, includes both internal and external factors operative at the time the representation was made, citing the observations of Wigney J in Unilever Australia Ltd v Beiersdorf Australia Ltd [2018] FCA 2076 at [20]-[22] (at TJ [260]).

76 His Honour summarised the ACCC’s contentions in relation to the allegedly misleading nature of the Google Ads (at TJ [19]-[20]) as follows:

19 The ACCC contended that the Government Affiliation Representations are conveyed by the headline and other words and phrases in the Google Ads and the URLs. Those phrases included “Fair Work Ombudsman” (FWO), “Fair Work Australia” or “Fair Work Commission” (FWC), which are major government agencies dealing with workplace relations. It contended that, by using those words in the Google Ads, the advertisements took on an “official” or “authoritative air”. The ACCC emphasised that the term Employsure did not appear in the advertisements. The ACCC contended that the Government Affiliation Representations were further conveyed by:

(a) the URL www.fairworkhelp.com.au/Fair-Work/Australia being displayed in the first six of the seven Google Ads immediately under the headline;

(b) the references to “free” advice, which appeared in all seven Google Ads, and to which particular emphasis was given in the first four ads by being expressed as “Free 24/7 Employer Advice”; and

(c) referring to its helpline as “the” advice service (or “the” free advice service) with the definitive article being used to reinforce the association of the service, or its resemblance, to the FWO helpline.

20 Finally, the ACCC relied upon the context in which the relevant representations were made. In particular, it emphasised that the seven Google Ads appeared following an internet search for the terms “fair work ombudsman” (Google Ads 1, 4 and 7), “fair work australia” (Google Ad 2), “fair work commission” (Google Ad 3), “australian government fair work” (Google Ad 5) and “australia fair pay” (Google Ad 6). It emphasised that Employsure knew that those search terms were commonly used by consumers searching for the FWO or the FWC. Another matter of context relied upon by the ACCC was the fact that several of the Google Ads (1, 3, 4, 5 and 6) displayed a phone number which allowed Google searchers to call simply by linking through to Employsure.

(Emphasis omitted from original).

77 His Honour noted the ACCC’s submission that the alleged representations were made in the course of advertising and that “much advertising is given little attention by consumers”. The ACCC submitted that was particularly so when the Google Ads which appeared when a person used a search term such as “fair work ombudsman”, actually contained that term in the headline as hypertext, which could then be clicked on immediately and the user would be taken through to the “Fair Work Help” landing page of Employsure. The ACCC said that in other cases the Google Ad displayed a telephone number which enabled the consumer to call immediately without reference to a landing page. His Honour noted the ACCC’s contention that in such circumstances the time and effort and concentration that a member of the relevant class might have applied to these ads was probably not as significant or as great as the person might have applied in other circumstances where there were significant implications arising from the material that the person was reading and digesting (at TJ [262]).

78 His Honour also noted the ACCC’s submissions that the Google Ads conveyed the alleged representations:

(a) by the headline, and other words and phrases in the Google Ads and the URL which included “Fair Work Ombudsman”, “Fair Work Australia” or “Fair Work Commission” being key government agencies which deal with workplace relations. The ACCC said that use of these words, including the names of government agencies, meant that the Google Ads took on an “official” or “authoritative air”. That was said to be reinforced by the use of these terms in their capitalised form because it suggested a government agency, rather than merely a reference to the subject matter that the agency regulates (at TJ [263]);

(b) by the absence of any mention of Employsure in the headline of the Google Ads, or at all, and the fact that each of Google Ads 1-6 contains the name of a government agency as prominent words at the beginning of the headline (at TJ [264]); and

(c) by:

(i) the URL www.fairworkhelp.com.au/Fair-Work/ being displayed in each of the Google Ads immediately under the headline;

(ii) the references to “free” advice, which appeared in each of the Google Ads, and which was expressed as “Free 24/7 Employer Advice” in Google Ads 1 and 4 in particular; and

(iii) the reference to Employsure’s hotline as “the” advice service, or “the” free advice service, using the definitive article, reinforced the association or resemblance of the services to the Fair Work Ombudsman helpline (at TJ [265]).

79 The primary judge noted the ACCC’s contentions as to the context in which the Google Ads were published (at TJ [266]-[270]). The ACCC submitted that in addition to the statements in the Google Ads themselves, the context in which the representations were made was also relevant in that:

(a) each of the Google Ads was generated following an internet search using the search terms “fair work ombudsman” (Google Ads 1, 4 and 7), “fair work Australia” (Google Ad 2), “fair work commission” (Google Ad 3), “Australia government fair work” (Google Ad 5) or “Australia fair pay” (Google Ad 6). The ACCC submitted that Employsure knew that “fair work ombudsman”, “fair work Australia” and “fair work commission” were search terms commonly used by consumers searching for the Fair Work Ombudsman (at TJ [266]);

(b) some of the Google Ads (Google Ads 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6) displayed a phone number which allowed consumers to call directly from the Google Ad, including by clicking on the link if using a smartphone. The ACCC said that in such cases consumers only had before them the search terms they had used and the information displayed in the Google Ad before speaking with an Employsure representative (at TJ [267]);

(c) some persons searching for employment-related advice on the internet and to whom Employsure’s Google Ads were presented were likely to have an immediate problem for which they required advice and assistance. Employsure’s Managing Director, Mr Mallett, gave evidence that a number of “Premier 1 leads” (being small businesses with 1-5 employees) who contacted Employsure fell into “what might be described as the urgent category”, who may have “need[ed] immediate help”(at TJ [268]);

(d) there was little force in Employsure’s claim that the presence of “.com” in the URL (and the absence of “.gov”) and the presence of the word “[Ad]” detracted from or dispelled the Government Affiliation Representations (at TJ [269]). Instead the misleading impression created by the Google Ads was a product of the following contextual matters:

(i) the search terms that generate the Google Ads, being the context in which they were published in response to a search term used by the consumer;

(ii) the text of the Google Ads themselves in what is said there and what is not said (particularly that none of the ads referred to “Employsure” and Google Ads 1 to 6 contain the name of a government agency prominently at the beginning of the headline); and

(iii) the fact that the Fair Work Ombudsman provides a similar business helpline that provides free advice; and

(e) each Google Ad was published at the top of the page, because such positioning gets attention, and once a user identifies the result that responds to their query there is no need for them to keep searching (at TJ [270]).

80 His Honour also noted the ACCC’s submissions that while it was unnecessary to show actual deception to establish a contravention of s 18 of the ACL, it was not “wholly irrelevant” that some consumers were in fact misled into thinking that Employsure was affiliated with government (at TJ [272]). In this regard the ACCC relied on:

(a) the evidence of representatives of three small business owners who gave evidence that after using a Google search to find employment-related advice they thought they were communicating with a government entity (variously and interchangeably characterised as “Fair Work”, “Work Safe” or the “Department of Fair Trading”) when in fact they were communicating with Employsure;

(b) Employsure’s own documents, which the ACCC said demonstrated the frequency with which employees (as distinct from employers) clicked on the Google Ads and called through to Employsure;

(c) Mr Mallett’s evidence that many employees called Employsure each day. The ACCC submitted that the primary judge should infer that the reason why a not insignificant number of employees contacted Employsure was that they, like employers, believed that the Google Ads had been published by a government agency; and

(d) the complaints received by the Fair Work Ombudsman which caused it to issue a media release, which the ACCC said demonstrated the scale on which members of the public were misled or deceived by Employsure’s Google Ads campaign.

81 The primary judge did not accept the ACCC’s submissions. His Honour considered that, viewed as a whole and taking into account both internal and external contextual features, the Google Ads were not misleading or deceptive, or likely to be so, when looked at through the prism of a hypothetical reasonable member of the relevant class (at TJ [273]). His Honour referred to seven matters as significant to that conclusion (at TJ [274]-[281]):

[274] First, it is made clear on the face of each of the seven Google Ads that they are advertisements, as is indicated by the word “Ad” which appears at the top of the advertisement adjacent to the hyperlink. An ordinary reasonable business owner, to whom should be attributed some knowledge of basic features of the internet and the Google search engine and its operations, would understand that this symbol demonstrated that the search result was a paid advertisement.

[275] As previously mentioned, the ACCC placed great emphasis on the fact that the word “Employsure” did not appear in the Google Ads. In my view, the significance of that omission is overstated, particularly when reference is made to Mr Mallett’s evidence that even when the term “Employsure” was added in 2019, there was no material change in the number of employees contacting the business. The following matters are also important in assessing the significance of the omission.

[276] Secondly, there are significant differences between the Google Ads and the organic search results linked to government agencies. The Google Ads are coloured differently from the government websites, which appear immediately below them. Moreover, the language used is quite different. For example, the government search results include language such as:

(a) “Welcome to the Fair Work Ombudsman website. Information and advice about Australia’s workplace rights and rules”;

(b) “The Fair Work Ombudsman promotes harmonious, productive and cooperative workplaces. They help employees, employers, contractors and the community to …”;

(c) “News & media ꞏ Fair Work Commission logo ... Coverage ꞏ National employment standards ꞏ The Commission & the Fair Work Ombudsman”;

(d) “Fair Work Commission. Australia’s national workplace relations tribunal”;

(e) “Fair Work Commission is the national workplace relations tribunal. It is an independent body with power to carry out a range of functions relating to: the safety net ...”;

(f) “Visit the Fair Work Ombudsman’s Consultation & cooperation page for detailed information about best practice consultation in the workplace”; and

(g) “The Fair Work Ombudsman and Fair Work Commission (the Commission) (previously called Fair Work Australia) are independent government organisations”.

[277] Thirdly, the domain description “.gov” appears prominently in both the FWO and FWC websites, clearly identifying them as government agencies, which is to be contrasted with Employsure’s Google Ads, which use the “.com” domain. I accept Employsure’s submission that ordinary reasonable business owners would understand the distinction between a “.gov” domain and a “.com” domain, which indicates the domain of a commercial organisation.

[278] Fourthly, the Google Ads are, in their terms, directed to employers. This is reflected in the terminology used, such as “The Free Advice Service for Employers”; “The Advice Service Line for Employers”; “Free 24/7 Employer Advice”; “Business Owner HR Advice” and “Pay Rates for Your Staff”.

[279] Fifthly, the words “fair work” have a broad descriptive meaning, which is not limited to particular government agencies such as the FWO or the FWC. Indeed, the expression reflects the name of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). I also accept Employsure’s submission that the expression “fairworkhelp” is descriptive and advertises a place where advice may be obtained as to the meaning and operation of that legislation and other employment related matters. Furthermore, as indicated above, I accept Mr Mallett’s explanation as to how the use of the words “fair work” increases the Quality Score and accordingly reduces the cost of Employsure’s Google advertising.

[280] Sixthly, although there is evidence that three witnesses who were associated with the three relevant small business owners mistakenly believed that they were dealing with a government agency when they used particular search words which took them to Employsure’s Google Ads or landing pages, the weight to be accorded to this evidence should not be overstated. As Employsure pointed out, there is no evidence to establish that each of the three relevant representatives was misled by one of the impugned representations. Mr Ottes’ evidence was that he could not recall whether he performed the Google search or whether it was someone else in the office that did it (see [413] below). Ms Richardson could not say precisely what search terms she entered or what she saw (see [374] below). Similarly, Ms Martindale was not entirely certain what search terms she entered and in any event it was not clear what results she was presented with (see [392] below). Further, Ms Richardson and Ms Martindale gave some evidence relating to Google Ads which falls outside the pleaded period. To my mind, of more evidentiary significance is the material which suggests that the vast majority of consumers who were presented with the Google Ads did not click on them. Presumably they were not led into error.

[281] Seventhly, I accept Employsure’s submission that a reasonable business owner who wished to contact the FWO or FWC or other similar government agency would be expected to take reasonable steps to verify that they are calling the correct number. The point is well illustrated by Puxu and the observations of Mason J which are set out at [240] above. The object of the consumer protection provisions is not to protect persons who do not take reasonable steps in their own self-interest. As already highlighted, the Google Ads indicate on their face that they are an advertisement and from a body which, at the very least, does not clearly identify itself as a government agency. Moreover, it is notable that the Google Ads are closely followed by organic search results which explicitly relate to specific government agencies, such as the FWO or FWC.

82 The primary judge concluded (at TJ [282]) as follows:

For these reasons, I find that the ACCC has failed to establish that a not insignificant number of ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class would infer that Employsure was, or was affiliated with and/or endorsed by government. Accordingly, the Government Affiliation Representations were not likely to mislead or deceive, nor were they false or misleading.

The appeal

83 The Notice of Appeal alleges:

The learned trial judge erred in failing to find:

(a) that the publication of each of Google Ads 1 to 6 as set out at TJ[12]-[17] conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations as defined in the Amended Concise Statement filed on 16 September 2019; and

(b) that the Respondent therefore engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) and/or made false or misleading representations about its services, including as to an affiliation with or endorsement by a government agency, or status as a government agency, in contravention of s 29 of the ACL.

Legislation AND relevant principles

84 Section 18 of the ACL provides:

Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

(2) Nothing in Part 3-1 (which is about unfair practices) limits by implication subsection (1).

85 Sub-sections 29(1)(b) and (h) of the ACL provide:

False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(b) make a false or misleading representation that services are of a particular standard, quality, value or grade; or

…

(h) make a false or misleading representation that the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation; or…

86 The parties were essentially in agreement as to the applicable principles concerning the prohibition on misleading or deceptive conduct under s 18 and on false or misleading representations under s 29, and their areas of disagreement largely concerned the application of those principles to the facts of the present case.

87 Section 18 of the ACL is based on s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) whereas s 29 is based on s 53 of the TPA. Section 29 is concerned with “representations” while s 18 is concerned with “conduct”, but in the present case, as in many cases, that makes no difference as it is uncontentious that conduct such as publication of the Google Ads can convey representations. The purpose of s 29 (and its predecessor provision in the TPA) has been described as being to “[support] ACL s 18 by enumerating specific types of conduct which, if engaged in trade or commerce in connection with the promotion or supply of goods or services, will give rise to a breach of the Act”: R Miller, Miller’s Australian Competition and Consumer Law Annotated (43rd ed, 2021), [ACL 29.20] p 1510.

88 There is no meaningful difference between the expressions “misleading or deceptive” in s 18 and “false or misleading” in s 29: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] (Gordon J) (in respect of the analogous provisions in the TPA); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [40] (Allsop CJ) (Coles Fresh Bread); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; (2020) 278 FCR 450 (TPG FFC) at [21] (Wigney, O’Bryan and Jackson JJ). The prohibitions under the provisions are similar in nature.

89 There is, though, one significant difference between ss 18 and 29. The inclusion of the phrase “likely to mislead or deceive” in s 18 means that a contravention may be established if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility that a person exposed to impugned conduct would be misled. It is not necessary to demonstrate that the impugned conduct was actually misleading; it is enough if it was likely to be so: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd [1984] FCA 167; (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87 (Bowen CJ, Lockhart and Fitzgerald JJ); Noone (Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria) v Operation Smile (Australia) Inc [2012] VSCA 91; (2012) 38 VR 569 at [60] (Nettle JA (as his Honour then was), Warren CJ and Cavanough AJA agreeing at [33]); Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2013] HCA 1; (2013) 249 CLR 435 at [6] (French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel (as her Honour then was) JJ). In contrast, the absence of that phrase in s 29 means that the applicant must prove to the requisite standard that the respondent made representations that were actually false or misleading. It is not sufficient for the applicant to prove only that it was likely that they were such: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 2) [2021] FCA 367 at [110] (Thawley J).

90 Because s 18 is focussed on “conduct” that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive, the necessary consideration must begin by identifying the impugned conduct with precision: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd [2009] HCA 25; (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [32] (French CJ); Google Inc at [89] (Hayne J). Section 29 is focussed on the alleged representation and that must be identified with precision. The impugned conduct and representations have been identified in the present case.

91 It is then necessary to consider whether the identified conduct was conduct “in trade or commerce”. In the present case it is uncontentious that it was.

92 The central question is whether the impugned conduct (under s 18) or the alleged representations (under s 29), viewed as a whole and in context, have a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter): Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 170; (1982) 42 ALR 177 at 200 (Deane and Fitzgerald JJ); Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd [1982] HCA 44; (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 198 (Gibbs CJ); Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [98] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne and Callinan JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG HCA) at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Campbell at [25] (French CJ).

93 Where, as in the present case, the impugned conduct or representation is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question as to whether the impugned conduct or representation is misleading (or in relation to s 18, is at least likely to mislead) must be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct or representation is directed, and consider the likely effect of the conduct on hypothetical ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Puxu at 199; Campomar at [102]; Google Inc at [7] and TPG FFC at [22].

94 Section 18 and 29 are not intended to protect people who fail to take reasonable care to protect their own interests: Puxu at 101, Campomar at [102].

95 It is unnecessary to prove that any person was actually misled by the conduct or representations in question. Evidence that a person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible, and may be persuasive, but is not essential. Indeed, such evidence does not of itself establish that conduct or a representation is misleading. The question as to whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or a representation is false or misleading is an objective one and the Court must determine the question for itself: Taco Bell at 202; Puxu at 198; Google Inc at [6] and TPG FFC at [22].

96 Conduct or a representation that merely causes confusion and wonderment is not necessarily misleading or deceptive, or false or misleading: Google Inc at [8]; Campomar at [106]; Taco Bell at 201; Coles Fresh Bread at [39].

97 It is not necessary to prove an intention to mislead or deceive or to make a false or misleading representation to show a contravention of s 18 or s 29:

in relation to s 18: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd [1978] HCA 11; (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228 (Stephen J with whom Barwick CJ and Jacobs J agreed, and at 234 per Murphy J); Puxu at 197; Google Inc at [9];

in relation to s 29: Given v C.V. Holland (Holdings) [1977] FCA 33; (1977) 29 FLR 212 at 217 (Franki J), Darwin Bakery Pty Ltd v Sully [1981] FCA 134; (1981) 36 ALR 371 at 376 (Keely, Toohey and Fisher JJ); Sporte Leisure v Paul’s International (No. 3) [2010] FCA 1162; (2010) 275 ALR 258 at [125] (Nicholas J).

98 In relation to allegedly misleading representations in advertisements it should be borne in mind that many readers will not study an advertisement closely, instead reading it fleetingly and absorbing only its general thrust. It is the impression or thrust conveyed to a viewer, particularly the first impression, that will often be determinative of the representation conveyed: Tobacco Institute of Australia v Australasian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc [1992] FCA 962; (1992) 38 FCR 1 at 4 (Sheppard J); Telstra Corporation v Optus Communications Pty Ltd [1996] FCA 1035; (1996) 36 IPR 515 at 523-524 (Merkel J) (Telstra v Optus); Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Telstra [2004] FCA 859 at [38] (Jacobson J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1254; [2011] ATPR 42-383 at [38] (TPG first instance), approved in TPG HCA at [47]. In deciding whether or not an advertisement is misleading the Court must put itself in the position of the relevant consumer. It should be kept in mind that the relevant consumers would have read the advertisement in a quite different context and way to that in which the judge considers them in a court environment and in the quiet of chambers. As Thawley J said in Google LLC (No 2) at [86]:

There is no question that the more one pores over the relevant screens, the more one notices matters of detail, the more one appreciates the literal meaning rather than what might first have been understood and the more one sees nuances and subtleties which might have been overlooked by the consumer.

EMploysure’s submissions

99 Employsure submits (as is common ground in the appeal) that the Google Ads were directed to a target audience comprising “business owners who employed staff and who used the internet to search for employment related advice”. It did not dispute that, depending on the operation of Google’s algorithms, by Employsure’s specification of and payment for various “keywords” to be associated with its Google Ads in the relevant period, advertisements were presented in the results of searches conducted by business owners that included headings with the terms “fair work ombudsman”, “fair work commission” and/or “fair work Australia”, which related to the terms in fact used by the searcher.

100 Employsure notes that none of the Google Ads are said by the ACCC to have expressly represented that Employsure was, or was affiliated with and/or endorsed by, a government agency. Rather the ACCC’s case depends upon it establishing that an ordinary or reasonable member of the class of business owners, reading each of the Google Ads in the context in which they appeared, would infer that Employsure was, or was affiliated with and/or endorsed by, a government agency.

101 Employsure says, and it is uncontentious, that it is necessary to consider each of the Google Ads in the context in which they appeared on the screen of a computer, tablet or smart phone in response to a Google search. That context includes the adjacent organic (or unpaid) search results that were displayed on the screen. Employsure argues that when the six Google Ads are seen in that context, even on a perfunctory or cursory review, the ordinary or reasonable business owner would have seen a clear contrast between the paid Google Ads and the adjacent organic search results linked with various government agencies.

102 Employsure submits that the relevant context includes the features of the Google Ads, as found by the primary judge, being that:

(a) they were identified as advertisements (at TJ [274]);

(b) they are in a different colour to the adjacent government related organic search results (at TJ [276]);

(c) the language they used is quite different to the more formal language of the adjacent government related organic search results ( at TJ [263] and [276]);

(d) they were directed exclusively to employers (at TJ [278]);

(e) the words “fair work” have a descriptive meaning which is not limited to government agencies, and reflect the name of the relevant legislation (at TJ [279]); and

(f) the evidence suggests that the vast majority of consumers presented with the Google Ads did not click on them (at TJ [280]).

103 Employsure contends that the present case is unlike the advertisements considered in TPG HCA as there is no express statement or dominant message in the impugned Google Ads, and no question arises about whether qualifications in the advertisements are sufficiently prominent to dispel the express statement or dominant message.

104 It submits that the ACCC is wrong in arguing that the primary judge attributed an excessive degree of technological and commercial sophistication and awareness to the relevant class. It argues that the degree of technological and commercial sophistication, and awareness that the primary judge attributed to class members was modest, as his Honour only attributed to class members “some knowledge of basic features of the internet and the Google search engine and its operation” (at TJ [274]). It contends that it would be wrong not to attribute at least that degree of knowledge to the relevant class of business owners who, by reason of their having the capacity to own and operate a business with employees, should reasonably be attributed with greater acumen than the public at large.

105 Employsure’s submissions as to the relevant principles broadly accorded with the applicable principles we have set out above. It accepts that in relation to representations allegedly made to the public or to a section of the public, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member and then to inquire with respect to that hypothetical individual whether the alleged misconception or deception arose or is likely to arise, excluding those reactions which are extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [103] and [105].

106 Employsure argues that the primary judge was correct (at TJ [273]) in stating that “the relevant question is whether an ordinary reasonable business owner would infer that such an affiliation [with a government agency] existed, when all relevant circumstances are taken into account.” Employsure argues that the primary judge then proceeded, correctly, to identify seven features of the Google Ads and their context which explained his conclusion that an ordinary or reasonable business owner would not infer that Employsure was, or was affiliated with and/or endorsed by, a government agency (at TJ [273]-[282]).

107 Employsure says that it was open to the primary judge to conclude that an ordinary or reasonable member of the class would understand that the  symbol (Ad Symbol) which appeared in each Google Ad signified that they were paid advertisements (at TJ [274]). It submits that the ordinary and reasonable member of the class would understand the distinction between the “.gov” domain name that appeared in the organic search results relating to government agencies such as the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Fair Work Commission, which appeared on the same search results page; and the “.com” domain name that appeared in each Google Ad and which indicated the domain related to a commercial organisation (at TJ [277]). On its argument, the primary judge asked himself the correct question and then answered it in a way that was open to him.

symbol (Ad Symbol) which appeared in each Google Ad signified that they were paid advertisements (at TJ [274]). It submits that the ordinary and reasonable member of the class would understand the distinction between the “.gov” domain name that appeared in the organic search results relating to government agencies such as the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Fair Work Commission, which appeared on the same search results page; and the “.com” domain name that appeared in each Google Ad and which indicated the domain related to a commercial organisation (at TJ [277]). On its argument, the primary judge asked himself the correct question and then answered it in a way that was open to him.

108 Employsure accepts that the primary judge incorrectly stated the applicable test in expressing his ultimate conclusion that “the ACCC has failed to establish that a not insignificant number of ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class would infer that Employsure was, or was affiliated with and/or endorsed by government” (at TJ [282]). It concedes that the Full Court decisions in TPG FFC and Trivago NV v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185; (2020) 384 ALR 496 (Middleton, McKerracher and Jackson JJ), both handed down after the close of argument before the primary judge, are authority for the proposition that there is no requirement for the ACCC to show that a “not insignificant number” of ordinary or reasonable class members were or were likely to be misled by the advertisements.

109 Employsure argues, however, that the primary judge’s reference to the “not insignificant number” test should properly be regarded as “superfluity” given that:

(a) his Honour identified the correct question (at TJ [273]); and

(b) his Honour’s substantive reasons (at TJ [260]-[281]) leading to the conclusion (at TJ [282]) were not expressed in terms that suggested that the ACCC was required to establish, on a qualitative basis, that some proportion of the ordinary and reasonable members of the class would have to be misled, or be likely to be misled.

110 Employsure argues that the primary judge’s expression of the ultimate conclusion in terms that the authorities now show to be incorrect does not mean that he did not address the correct question, nor that his Honour would have reached a different conclusion had he done so. It notes that in both TPG FFC at [24] and Trivago at [193] the Full Court held that the application of the wrong test in those cases made no difference to the result.

111 Employsure also rejects the ACCC’s contention that the primary judge mistakenly narrowed the representations alleged (at TJ [248]-[249]), by omitting the representation that the Google Ads conveyed that Employsure was a government agency (as compared to a private service affiliated with or endorsed by a government agency). It contends that when careful attention is given to those paragraphs, the omission was appropriate as the primary judge was considering the alleged breach of s 29(1)(h) of the ACL which concerns false or misleading representations that a person has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation. The primary judge observed that in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optell Pty Ltd [1998] FCA 602; (1998) ATPR 41-640, O’Loughlin J held that s 53(d) of the TPA, the predecessor to s 29(1)(h) of the ACL, did not apply where the private organisation represented that it was the government. It says that the primary judge drew an appropriate contrast on the basis that in the present case, unlike in Optell, the ACCC alleged that Employsure represented that it is a government agency and also that it is affiliated with, or is endorsed by, a government agency.

112 Employsure says that the ACCC’s contention that the trial judge considered the Google Ads as a “job lot”, rather than individually, is unfair and contends that the primary judge considered each of the impugned Google Ads. It notes that the primary judge set out each of the Google Ads (at TJ [12]-[17]) and referred to the various aspects of the advertisements upon which the ACCC relied (at [TJ [263]-[265]). On its argument, the primary judge having concluded that there were a series of matters that were common to all of the Google Ads, it was unnecessary for his Honour to repeat himself five times by saying the same thing about each of the advertisements.

113 It submits that the primary judge took into account and weighed the contextual matters which the ACCC alleges show that the Google Ads conveyed the Government Affiliation Representations. For example, the primary judge:

(a) considered the absence of the name Employsure in the search results to be “a relevant factor” (at TJ [264] and [275]);

(b) took into account that the Google Ads were generated upon an internet search for the terms “fair work ombudsman, “fair work Australia”, “fair work commission”, “Australia government fair work” and “Australia fair pay” (at TJ [266]);

(c) did not expect that the ordinary or reasonable business owner would engage in “careful scrutiny” of the Google Ads or undertake a “careful comparison” of those ads with the organic search results for government agencies. The primary judge considered that a reasonable business owner who wished to contact a relevant government agency would be expected to take reasonable steps to verify that they were calling the correct number (at TJ [281]); and

(d) took into account that some of the Google Ads included a telephone number (at TJ [262] and [273]).

114 Employsure also rejects the ACCC’s contention that the fact that each of the Google Ads referred to “free” advice, which was similar to the free helpline offered by the Fair Work Ombudsman, acted in support of the alleged representation. It says that does not alter the balance in terms of whether the alleged representations were conveyed.

115 Employsure notes that the primary judge found (at TJ [280]) that there is no evidence to establish that any of the small business owners called by the ACCC were misled by one of the impugned Google Ads. This finding is not challenged in the appeal.

116 It submits that the ACCC has failed to demonstrate why, what it describes as the primary judge’s “layered and careful analysis” of the circumstances relevant to publication of the impugned advertisements, shows appellable error. It contends that the primary judge’s conclusions were open to him and that the appeal should be dismissed.

Consideration

The nature of the appeal

117 Appeals to this Court from the decision of a single judge of the Court are by way of a rehearing, which involves correction of error. How the primary judge’s reasoning may be shown to be wrong depends on what the reasoning is about, and error is not demonstrated merely because the appellate court disagrees with the primary judge: Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees Pty Ltd (No 2) [2001] FCA 1833; (2001) 117 FCR 424 at [20]-[24] (Allsop J (as his Honour then was) with Drummond and Mansfield JJ agreeing).

118 As Perram J (with whom Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreed) pellucidly explained in Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; (2018) 261 FCR 301 at [45]-[54], at one extreme lies a trial judge’s conclusions as to the law, where the appellate court will show no deference at all to such conclusions. If the appeal court considers the trial judge has made an error of law it must substitute its view. At the other extreme lies a trial judge’s findings of fact where the reliability or credit of a witness is involved. In such cases it is accepted that the trial judge enjoys very considerable advantages over an appellate court and the court on appeal will not depart from such findings unless they are shown to be wrong by reference to “incontrovertible fact or uncontested testimony” or otherwise are “contrary to compelling inferences”: Moroccanoil at [46] citing Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 at [28]-[29].

119 Between those extremes lies a “grey area” in which the amount of deference shown to a trial judge’s conclusions is a function of the nature of the issues before the trial judge and the relative advantage enjoyed by the trial judge over the appellate court: Moroccanoil at [47]. One type of finding that falls within this grey area is the drawing of inferences by an appellate court from facts already found. Speaking of that question, in Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 551, Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ explained:

…[I]n general an appellate court is in as good a position as the trial judge to decide on the proper inference to be drawn from facts which are undisputed or which, having been disputed, are established by the findings of the trial judge. In deciding what is the proper inference to be drawn, the appellate court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the trial judge, but, once having reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it.

120 Other types of findings within this grey area, include conclusions as to whether certain packaging conveyed the alleged representation, whether a word or phrase is capable of distinguishing one trader’s goods from another, and whether the facts show conduct within or outside standards such as unconscionability or oppressive conduct. Such questions and the application of such standards involve an element of evaluation. In such cases the appeal court must be guided not by whether it disagrees with the finding but whether it detects error in it. Error may appear syllogistically where it is apparent that the conclusion reached involves some false step, for example overlooking some relevant matter. Error may, on the other hand, also appear without any explicitly erroneous reasoning as the result may be such as simply to bespeak error. In such cases as Allsop J (as his Honour then was) said in Branir at [29] an error may be manifest where the appellate court has a “sufficiently clear difference of opinion”: Moroccanoil at [49].

121 Even so, as Allsop CJ (with whom Markovic J agreed) said in Moroccanoil at [7], the Full Court in Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 130; (2011) 197 FCR 67 at [33] (Cowdroy, Middleton and Jagot JJ) correctly eschewed the use of “sound bites” such as “plainly or [sic: and] obviously wrong” (taken from Eagle Homes Pty Ltd v Austec Homes Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 138; (1999) 87 FCR 415) or “sufficiently clear difference of opinion” (taken from Branir). The Full Court in Optical 88 explained that the task of this appellate Court is complex; it cannot be captured by such sound bites and approved the principles explained in Branir at [28]-[29].

122 We have reached our view on the appeal by application of the principles explained in Branir and Moroccanoil. First, we have made up our own mind as to the facts, doing so in the context that there is now no factual dispute between the parties. In particular there is no dispute in relation to the primary judge’s findings as to the publication and contents of the Google Ads and the context in which they appeared in relation to other search results on the screens of computers, tablets and smartphones. Our view that the primary judge fell into error is not based on any difference of view in relation to those matters.

123 Second, we have given appropriate respect and weight to the views of the primary judge, in the context that there is no challenge to the primary judge’s acceptance of the evidence of Employsure’s witnesses, nor to his Honour’s finding that the evidence of the three small business owners called by the ACCC does not establish that any of them was misled by one of the Google Ads. This is not an appeal which involves application of the principles relating to appellate review of findings as to the reliability and credit of witnesses.

124 Third, the primary judge’s conclusions that the advertisements were not misleading or likely to be so were based on his Honour’s enunciation of the matters significant to that conclusion (at TJ [274]-[281]), being an evaluation of the relative significance of the features of the Google Ads and the context in which they appeared, in terms of the impression conveyed to an ordinary or reasonable business owner. Like the primary judge, we have the Google Ads and how they appeared in context before us. We are in as good a position as his Honour to decide whether the Google Ads conveyed the alleged representations to an ordinary or reasonable business owner.

125 Fourth, this is not a case of the type described in State Rail Authority of New South Wales v Earthline Constructions Pty Ltd (in liq) and Others [1999] HCA 3; (1999) 160 ALR 588 at [90] (Kirby J), approved in Fox v Percy (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Kirby JJ), in which the primary judge had an advantage through hearing the evidence in its entirety and had the opportunity for reflection and mature contemporaneous consideration over the course of a lengthy and complex hearing and adjournments. The claim in relation to the Government Affiliation Representations was not lengthy or complex, and the witness evidence is not central to our conclusion. Again, we are in as good a position as the primary judge.

126 It can be accepted that the primary judge’s conclusion that the advertisements did not convey the Government Affiliation Representations involved weighing and evaluating the features of the advertisements and the context in which they appeared; but in our view Employsure’s contention that the conclusion was “open” to his Honour eludes the point. The proper question is whether the primary judge’s reasoning and conclusion reveals error. In our view they do.

The relevant class and the likely characteristics of persons comprising it

127 Where, as in the present case, the impugned conduct or representation is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question as to whether the conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, or the representation false and misleading, must be approached by the Court considering the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the class to whom the conduct or representation is directed, and the likely effect of the conduct or representation on a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Puxu at 199; Campomar at [102]; Google Inc at [7]; TPG FFC at [22].

128 Identifying an ordinary or reasonable member of the class of business owners involves “an objective attribution of certain characteristics” against the background of the membership of the class: Campomar at [102]. It is necessary to “isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class” and determine whether the misconceptions or deceptions alleged to arise, or to be likely to arise “are properly to be attributed to the ordinary member of the [class]”: Campomar at [103] and [105].