Federal Court of Australia

Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc v Sequenom, Inc [2021] FCAFC 101

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

VID 879 of 2019 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | SONIC HEALTHCARE LIMITED Appellant | |

AND: | SEQUENOM, INC Respondent | |

VID 910 of 2019 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | CLINICAL LABORATORIES PTY LTD Appellant | |

AND: | SEQUENOM, INC Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer and within 14 days file an agreed minute of orders, including as to costs, reflecting the reasons of the Court, or, in default of agreement:

(a) within 14 days of the date of these orders, the appellants are to file and serve submissions of no more than 5 pages in support of their draft form of orders;

(b) within 14 days thereafter, the respondent is to file and serve submissions of no more than 5 pages in response; and

(c) within 7 days thereafter, the appellants are to file and serve any submissions in reply of no more than 2 pages.

2. Unless otherwise requested, any outstanding issues between the parties be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[7] | |

[9] | |

[10] | |

[13] | |

[17] | |

[22] | |

[30] | |

[30] | |

[65] | |

[76] | |

[76] | |

[94] | |

[95] | |

[108] | |

[168] | |

[168] | |

[179] | |

[181] | |

[185] | |

[185] | |

[204] | |

[206] | |

[219] | |

[227] | |

[228] | |

[228] | |

[233] | |

[234] | |

[236] | |

[244] | |

[244] | |

[245] | |

[249] | |

[250] | |

[252] | |

[272] |

THE COURT:

1 The present appeals concern a ground-breaking discovery by Professor Yuk-Ming Lo that cell-free foetal DNA could be detected in the blood plasma and serum of pregnant women. It led to the grant of Australian patent No.727919, entitled “Non-invasive prenatal diagnosis”, claim 1 of which is:

A detection method performed on a maternal serum or plasma sample from a pregnant female, which method comprises detecting the presence of a nucleic acid of foetal origin in the sample.

2 The respondent, Sequenom, Inc, is the patentee. Ariosa Diagnostics Inc conducts and licenses others, including Sonic Healthcare Ltd and Clinical Laboratories Pty Ltd (collectively, the appellants) in Australia, to conduct a non-invasive prenatal test called the Harmony Test. Sequenom sued the present appellant’s alleging that the Harmony Test infringed claims 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 13, 14, 22, 23, 25 and 26 of the patent. The appellants cross-claimed seeking the revocation of those claims. They failed to establish invalidity in respect of the grounds of lack of manner of manufacture, lack of inventive step, lack of utility, lack of sufficiency and false suggestion, but succeeded in relation to claim 26 in their allegations of lack of fair basis. The respondent succeeded in its infringement case on all but claim 26: Sequenom, Inc. v Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. [2019] FCA 1011; 143 IPR 24 (Beach J).

3 The appellants now appeal against the decision of the primary judge on the bases that he erred in his conclusions in relation to lack of manner of manufacture (appeal grounds 1 to 5), lack of fair basis (appeal grounds 6 to 9), lack of sufficiency (appeal grounds 10 to 11) and aspects of the infringement findings (appeal grounds 12 to 15). In the present appeals, the appellants challenge the validity of claims 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 13, 14, 22, 23 and 25 (relevant claims).

4 The priority date of the patent is 4 March 1997. It was filed on 4 March 1998 and granted on 19 April 2001. The relevant legislation applicable to the issues in suit is the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) in the form that it took at the priority date.

5 For the reasons set out in more detail below, we dismiss appeal grounds 1 to 13, but allow the appeal insofar as it challenges the primary judge’s findings concerning infringement by use of the “send out test” as identified in grounds 14 and 15 of the appeal.

6 There are divided views as to whether the correct spelling is “foetus” or “fetus” (and its derivatives). In these reasons we adopt the former.

2. BACKGROUND COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE

7 The primary judge commenced his judgment with a glossary of some relevant terms in the field of prenatal diagnosis and then set out a summary of the common general knowledge in the fields of foetal medicine and molecular genetics as at the priority date. He found that the relevant person skilled in the art to whom the patent is addressed is a team comprising a person with experience in foetal medicine and in particular an interest in prenatal screening and diagnosis, and a person with experience in standard molecular genetics techniques, preferably including some practical experience of the techniques involved in laboratory-based genetic analysis of patient samples in a clinical context. The findings that he made in respect of these subjects are not challenged on appeal.

8 The following matters are relevant background to understanding the disclosure of the patent and have been extracted from the glossary of terms and the primary judge’s findings of common general knowledge as at the priority date.

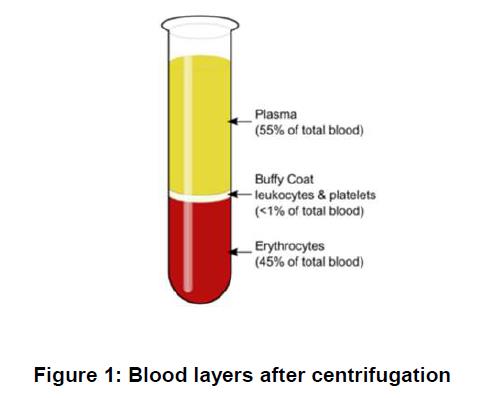

9 It was known in the field that foetal cells were present in the mother’s blood. Plasma makes up 55% of the blood. It contains water, blood plasma proteins (including clotting factors), minerals and dissolved nutrients and waste products. Serum is the name given to plasma which has had the clotting factors removed. Whole blood can be separated by centrifugation into three layers: (a) the upper plasma layer; (b) the “buffy coat” layer which contains leukocytes and thrombocytes; and (c) the lower layer which contains the erythrocytes which may be depicted as follows:

10 “Cell free DNA” is non-cellular DNA (i.e. DNA that is outside a cell). “Cell free foetal DNA” (cffDNA) is non-cellular DNA from a foetus.

11 The idea that foetal cells might be present in the mother’s blood had been first proposed in 1969. The possibility of being able to access whole foetal cells by taking a maternal blood sample was of great interest because it would allow analysis of the foetal genome to be carried out without the need for invasive testing, which typically involved extracting a sample with a needle inserted through a mother’s abdomen or cervix, and the problems associated with those invasive techniques such as an increased risk of miscarriage. Instead, all that would be needed was a blood sample from the mother’s arm. As a result, a substantial amount of work was carried out in this area through the 1980s and the 1990s. By the priority date it was known that several different types of foetal cells were present in maternal blood during pregnancy, and that these foetal cells had the potential to be used for prenatal testing.

12 From at least the late 1980s there was research being done by a number of groups on processes of recognition and enrichment of foetal cells. The aims of this research included investigating the use of foetal cells isolated from maternal blood to provide a non-invasive means of diagnosis of Down syndrome, to determine the blood type of the foetus and enable the pregnancy to be managed accordingly, to provide a way to determine the sex of the foetus (which would be useful when trying to identify foetuses with possible sex-linked disorders), and to diagnose single gene disorders. However, isolating foetal cells was not easy because they were known to occur only rarely in maternal blood and were vastly outnumbered by maternal cells in the sample.

13 The human genome represents the complete set of inherited instructions encoded in DNA in a human cell. Genetic disorders are caused by changes to the genome. They may be caused by a range of mechanisms such as deletions, duplications, rearrangements and chemical modifications affecting anything from a single base to a whole chromosome or even the whole genome. Those caused by a defect in only one gene, for example cystic fibrosis, are classed as “single-gene disorders”. Other disorders may be caused by one of a number of genes. Although the spectrum is a continuum, disorders involving larger regions such as partial or whole chromosomes, for example Down syndrome, are generally referred to as “chromosomal” whilst those involving changes at the nucleotide level are generally classed as “molecular”. Genetic disorders may be inherited or arise “de novo” in the germ cell or developing embryo.

14 Before the priority date, prenatal testing was available for some single gene disorders, such as sickle cell anaemia, thalassemia and cystic fibrosis. Disorders can be inherited in an X chromosome-linked fashion in which a male will be more likely to have the disease phenotype as they only have one copy of the X chromosome.

15 A number of diseases were known to be caused by a defective gene on the X chromosome, e.g. haemophilia. In many cases, these diseases primarily affect male foetuses because female foetuses will have another, non-defective, copy of the X chromosome. Work was on-going at the priority date to try to find ways to identify foetuses with possible sex-linked disorders. There was, therefore, a desire to develop a way to identify the sex of the foetus quickly, accurately and as early as possible in the first trimester. Further, in cases of congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which is not an X-linked condition, treatment with dexamethasone is needed to prevent virilisation in girls. This medication can be stopped once the foetus is known to be male. In severe X-linked diseases for which the parents may wish to elect termination, having a diagnosis as early as possible in the first trimester is valuable. DNA testing for diseases in such cases, which often took a week or longer, would only be done after the sex determination and could be omitted if the foetus was known to be female. Gender determination by ultrasound only became reliable for establishing the sex of a foetus from 18 weeks onwards.

16 As at the priority date, the sex of a male foetus would be apparent if a particular molecular test involved the amplification of sequences known to be from the Y chromosome. In other words, if one could detect a Y-specific fragment, it was most likely that the foetus was male. This required sequence information for the Y chromosome to be known to allow for the design of primers to result in the Y-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products. Further, the loci would need to be known to be unique to the Y chromosome. As at the priority date, there were Y-specific sequences published in the literature which could be used as PCR primers.

2.4 Molecular genetic diagnosis

17 Molecular genetic clinical diagnosis first became possible in the 1980s following the discovery of genetic markers, that is, known sites of variation between individuals within a population located on a particular chromosome, otherwise known as genetic polymorphisms.

18 The process of working out which allele (marker) a person had at a particular position or set of positions on a chromosome, that is, determining the genetic make-up of the alleles at the relevant loci on an individual’s chromosomes was called genotyping.

19 At the priority date the vast majority of genotyping methods depended on either detecting differences by length of genetic variation, sequence, position, conformation, or methylation.

20 Genetic markers used to detect human DNA per se could be as simple as detecting any one of the many repeat element families in the human genome e.g. Alu repeats. An alternative approach would be to test for the presence of a single copy gene. A more refined method of detection would rely on demonstration of differences based on polymorphism such as restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) detected either by genomic Southern blotting, or by PCR. Other markers commonly used at the time included short tandem repeats (STRs), variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs), and other genetic variants. These markers and others, along with the determination of single or multiple copy sequences relative to a standard, were used to quantify DNA.

21 In 1997 thousands of markers that could be used for human molecular genetic testing, including STRs, VNTRs, RFLPs and markers of structural variants, were known. Of the variants, those used for human molecular screening/diagnosis would detect or be closely linked to the mutations underlying the specific genetic disease. Such markers would ideally be validated to document sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values. A wider number of markers may be required for diagnostic testing compared to screening.

22 By the priority date there was a range of molecular techniques and technologies available. These included gel electrophoresis, PCR (including nested PCR, and quantitative PCR techniques) and ligase chain reaction (LCR). For present purposes it is sufficient to describe PCR.

23 PCR is a standard molecular biology technique that involves the amplification of specific sequences of DNA using repeated cycles of denaturation, primer annealing and extension, resulting, in theory, at least in exponential accumulation of DNA fragments.

24 A primer is a short nucleic acid sequence that serves as a starting point for DNA synthesis. It is required for DNA replication because the enzymes that catalyse this process, DNA polymerase, can only add new nucleotides to an existing strand of DNA. DNA primers must be designed to bind to opposite DNA strands and flank the target of interest and initiate synthesis of a new DNA strand complementary to the target sequence of each template strand. These primer pairs are commonly referred to as the forward and reverse primers.

25 PCR requires the following components:

(a) A DNA template which is the gene or DNA sequence to be amplified.

(b) Primers, which are short single stranded pieces of DNA that have been synthesised to be complementary to a section of DNA. Two primers flank the gene or DNA fragment (in opposite orientation) to be amplified.

(c) DNA polymerase, being an enzyme that recognises primers and mediates the replication of the DNA template between the two primers starting from the 5' end to the 3' end (being the two ends of a strand of DNA) by adding a complementary base to the growing strand. The most commonly used of these enzymes was Taq DNA polymerase which was derived from the heat-resistant bacteria Thermus aquaticus. As it is heat resistant it is suitable for use in PCR, which relies on thermal cycling.

(d) Nucleotides (dNTPs or deoxynucleotide triphosphates), being single units of the bases A, T, G, and C or in other words the “building blocks” for new DNA.

26 In broad terms, PCR involves the following steps:

(a) Denaturation where the sample DNA is heated to break the weak bonds between the nucleotides of each strand so that the DNA separates into two separate strands.

(b) Annealing. PCR does not copy all of the DNA in the sample but only a very specific gene or DNA sequence targeted by the primers. In this step, the primers bind, or anneal, to their complementary sequences on the DNA strands, marking the beginning of the sequence to be copied in the following step. Annealing occurs at lower temperatures than denaturation, and in this respect a balance needs to be achieved between a higher temperature which achieves greater specificity / lower mismatches, and the risk of denaturing the primers at those higher temperatures which prevents binding.

(c) Extension where the reaction tube is heated to facilitate the extension of the nucleotide chain. From the start of the regions marked by the primers, nucleotides in the solution are added to the annealed primers by DNA polymerase to create a new strand of DNA complementary to each of the single DNA template strands. After this step, two identical copies of the original target DNA sequence are made. The extension must continue past the position of the primer on the complementary strand, so that in the next PCR round that new copy serves as a template for further amplification.

(d) Repetition of the above steps about 30 to 35 times to produce a sufficient amount of DNA copies of the original DNA target sequence. Too many amplification cycles beyond this leads to a building up of PCR “artefacts”, which create extra bands and impede analysis.

27 PCR relies on the design of primers that will amplify a sequence of interest. As at the priority date, a number of issues needed to be considered in primer design, which sometimes required multiple rounds of optimisation, including limited sequence information and manual primer design. The Gene Mutation Database and Human Genome Database were used at the priority date to design primers for use in DNA amplification methods for human molecular genetic testing. Therefore, it was wise to validate any chosen marker. Both of these databases were searchable for specific DNA loci and the specific sequences could be downloaded and employed for primer design.

28 Quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a broad term that is used to refer to PCR methods which enable the products of a conventional PCR reaction to be quantified. By the priority date, amplification of sequences that were the targets of qPCR could be detected using a number of methods including agarose gels (a form of gel electrophoresis), fluorescent labelling of PCR products and detection with laser-induced fluorescence using capillary electrophoresis or acrylamide gels and plate capture and sandwich probe hybridisation.

29 One type of qPCR method that was available by the priority date was real-time quantitative PCR (real-time qPCR). Real-time qPCR involved a PCR reaction during which accumulation of the amplified PCR product was monitored by measuring a signal created by either fluorescent dyes or fluorescent probes in the reaction sample to generate an amplification curve. That is, real time qPCR is a development of standard (or end-stage) PCR, and uses fluorescent reporter molecules to monitor the amounts of PCR product present after each PCR cycle. This allows the generation of a growth curve and enables the quantification of DNA in the exponential phase by determining the number of amplification cycles necessary to achieve a specified fluorescence level.

30 The patent commences by identifying the field (page 1 lines 1 to 5):

This invention relates to prenatal detection methods using non-invasive techniques. In particular, it relates to prenatal diagnosis by detecting foetal nucleic acids in serum or plasma from a maternal blood sample.

31 The patent continues by referring to known methods for detecting foetal abnormalities (page 1 lines 7 to 11):

Conventional prenatal screening methods for detecting foetal abnormalities and for sex determination traditionally use foetal samples derived by invasive techniques such as amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling. These techniques require careful handling and present a degree of risk to the mother and to the pregnancy.

32 The patent then turns to techniques for predicting abnormalities (page 1 lines 12 to 14):

More recently, techniques have been devised for predicting abnormalities in the foetus and possible complications in pregnancy, which use maternal blood or serum samples. Three markers commonly used include alpha-foetoprotein (AFP- of foetal origin), human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) and estriol, for screening for Down’s Syndrome and neural tube defects.

33 The patent continues (page 1 lines 18 to 28):

The passage of nucleated cells between the mother and foetus is now a well-recognised phenomenon (Lo et al 1989, Lo et al 1996). The use of foetal cells in maternal blood for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis (Simpson and Elias 1993) avoids the risks associated with conventional invasive techniques. WO 91/08304 describes prenatal genetic determination using foetal DNA obtained from foetal cells in the maternal blood. Considerable advances have been made in the enrichment and isolation of foetal cells for analysis (Simpson and Elias 1993; Cheung et al 1996). However, these techniques are time-consuming or require expensive equipment.

34 The specification then describes a breakthrough discovery at page 2 lines 5 to 9:

It has now been discovered that foetal DNA is detectable in maternal serum or plasma samples. This is a surprising and unexpected finding; maternal plasma is the very material that is routinely discarded by investigators studying non-invasive prenatal diagnosis using foetal cells in maternal blood.

35 It goes on to describe some benefits of the discovery, including that using serum or plasma results in higher detection rates than comparable volumes of blood, suggesting enrichment of foetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum. At page 2 lines 12 to 16 the specification explains that:

… the concentration of foetal DNA in maternal plasma expressed as a % of total DNA has been measured as from 0.39% (the lowest concentration measured in early pregnancy) to as high as 11.4% (in late pregnancy), compared to ratios of generally around 0.001% and up to only 0.025% for cellular fractions (Hamada et al 1993).

36 In what may be described as a broad characterisation of the invention the specification then says (page 2 lines 20 to 23):

This invention provides a detection method performed on a maternal serum or plasma sample from a pregnant female, which method comprises detecting the presence of a nucleic acid of foetal origin in the sample. The invention thus provides a method for prenatal diagnosis.

37 The term “prenatal diagnosis” is defined in the passage that follows (page 2 line 24 to page 3 line 4):

The term “prenatal diagnosis” as used herein covers determination of any maternal or foetal condition or characteristic which is related to either the foetal DNA itself or to the quantity or quality of the foetal DNA in the maternal serum or plasma. Included are sex determination, and detection of foetal abnormalities which may be for example chromosomal aneuploidies or simple mutations. Also included is detection and monitoring of pregnancy-associated conditions such as pre-eclampsia which result in higher or lower than normal amounts of foetal DNA being present in the maternal serum or plasma. The nucleic acid detected in the method according to the invention may be of a type other than DNA e.g. mRNA.

38 The specification explains aspects of how the method may be performed, both in the examples and also in the general description. In the latter, it explains first that a maternal serum or plasma is “derived” from the maternal blood, and that as little as 10 µl of serum or plasma can be used (page 3 lines 5 to 6).

39 Secondly, it refers to the preparation of the serum or plasma (using “standard techniques” which are expanded upon in the examples) and, normally, the process of nucleic acid extraction (page 3 lines 11 to 23):

The preparation of serum or plasma from the maternal blood sample is carried out by standard techniques. The serum or plasma is normally then subjected to a nucleic acid extraction process. Suitable methods include the methods described herein in the examples and variations of those methods. Possible alternatives include the controlled heating method described by Frickhofen and Young (1991). Another suitable serum and plasma extraction method is proteinase K treatment followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. Serum and plasma nucleic acid extraction methods allowing the purification of DNA or RNA from larger volumes of maternal sample increase the amount of foetal nucleic acid material for analysis and thus improve the accuracy. A sequence-based enrichment method could also be used on the maternal serum or plasma to specifically enrich for foetal nucleic acid sequences.

40 Thirdly, it explains (at page 3 lines 24 to 28) that the amplification of foetal DNA sequences in a sample is normally carried out, and describes “standard nucleic acid amplification systems” that can be used as including PCR, LCR, nucleic acid sequence based amplification, branched DNA methods “and so on”. However, preferred amplification methods involve PCR.

41 The specification then sets out one use to which the method of detection may be put (page 3 line 29 to page 4 line 1):

The method according to the invention may be particularly useful for sex determination which may be carried out by detecting the presence of a Y chromosome. It is demonstrated herein that using only 10 µl of plasma or serum a detection rate of 80% for plasma and 70% for serum can be achieved. The use of less than 1ml of maternal plasma or serum has been shown to give a 100% accurate detection rate.

42 As examples of detection methods within the invention, the specification describes each of (page 4 lines 5 to page 5 line 2): foetal RhD status determination in rhesus negative mothers; the detection of haemoglobinopathies; and the detection of paternally-inherited DNA polymorphisms or mutations. The techniques so described concern the qualities of the foetal genes detected.

43 The patent then says (page 5 lines 3 to 6):

The plasma or serum-based non-invasive prenatal diagnosis method according to the invention can be applied to screening for Down’s Syndrome and other chromosomal aneuploidies.

44 It explains two possible ways in which this might be done by consideration of the quantity of foetal cells in the maternal blood or the quantitation of foetal DNA markers on different chromosomes. A further application of the accurate quantitation of foetal nucleic acid levels is then said to be the monitoring of certain placental pathologies such as pre-eclampsia, because in that condition the concentration of foetal DNA in maternal serum and plasma is elevated (page 5 line 28 to page 6 line 2).

45 As we note in section 5 below, the distinction between qualitative and quantitative methods is relevant to the sufficiency challenge advanced by the appellants based on s 40(2)(a) of the Act.

46 The patent then illustrates the invention by reference to five examples.

47 Example 1 provides an analysis of cffDNA for sex determination, a qualitative test. The example describes the patients being pregnant women from whom maternal peripheral blood was collected, centrifuged and the plasma and serum separately extracted. Detail in the example addresses sample preparation and DNA extraction from plasma and serum as follows (page 7 lines 6 to 26):

Sample preparation

Maternal blood samples were processed between 1 to 3 hours following venesection. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000g and plasma and serum were carefully removed from the EDTA-containing and plain tubes, respectively, and transferred into plain polypropylene tubes. Great care was taken to ensure that the buffy coat or the blood clot was undisturbed when plasma or serum samples, respectively, were removed. Following removal of the plasma samples, the red cell pellet and buffy coat were saved for DNA extraction using a Nucleon DNA extraction kit (Scotlabs, Strathclyde, Scotland, U.K.) The plasma and serum samples were then subjected to a second centrifugation at 3000g and the recentrifuged plasma and serum samples were collected into fresh polypropylene tubes. The samples were stored at -20°C until further processing.

DNA extraction from plasma and serum samples

Plasma and serum samples were processed for PCR using a modification of the method of Emanuel and Pestka (1993). In brief, 200 µl of plasma or serum was put into a 0.5ml eppendorf tube. The sample was then heated at 99°C for 5 minutes on a heat block. The heated sample was then centrifuged at maximum speed using a microcentrifuge. The clear supernatant was then collected and 10 µl was used for PCR.

48 Next, the example describes the DNA extraction from amniotic fluid. It then describes the use of PCR (page 8 lines 7 to 20):

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out essentially as described (Saiki et al 1988) using reagents obtained from a GeneAmp DNA Amplification Kit (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA). The detection of Y-specific foetal sequence from maternal plasma, serum and cellular DNA was carried out as described using primers Y1.7 and Y1.8, designed to amplify a single copy Y sequence (DYS14) (Lo et al 1990). ... The Y-specific product was 198 bp. Sixty cycles of Hot Start PCR using Ampliwax technology were used on 10 µl of maternal plasma or serum or 100ng of maternal nucleated blood cell DNA. ... Forty cycles were used for amplification of amniotic fluid.

49 The PCR products then were analysed using “agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining”. Gel electrophoresis is a technique used to separate and visualise molecules like DNA based on their molecular weight.

50 The specification then reports the results, saying at page 9 lines 1 to 5 that of the 30 women bearing male foetuses, Y-positive signals were detected in 24 plasma samples and 21 serum samples, when 10 µl of the respective samples was used for PCR.

51 By contrast, the results using cellular DNA were less accurate (page 9 lines 6 to 7): “When nucleated blood cell DNA was used for Y-PCR, positive signals were only detected in 5 of the 30 cases”.

52 The specification concludes at page 9 lines 10 to 13:

Accuracy of this technique, even with serum/plasma samples of only 10 µl, is thus very high and most importantly it is high enough to be useful. It will be evident that accuracy can be improved to 100% or close to 100%, for example by using a larger volume of serum or plasma.

53 Example 2 is entitled “Quantitative analysis of foetal DNA in maternal serum in aneuploid pregnancies”. The specification explains that prenatal screening and diagnosis of foetal chromosomal aneuploidies is an important part of modern obstetric care, and that much effort has been devoted to the development of non-invasive screening methods. The two main such methods are maternal serum biochemical screening and ultrasound examination for nuchal translucency, but both are associated with significant false positive and negative rates (page 9 lines 18 to 26). The specification notes that recent studies have demonstrated that there is increased foetal nucleated cell number in maternal circulation when the foetus is suffering from a chromosomal aneuploidy (page 10 lines 2 to 5).

54 The primary judge describes the process used in the example at [260]:

In this example, the inventors used 400 to 800µL of plasma/serum samples derived from the blood of pregnant women, extracted DNA from those samples and subjected the extracted DNA to real-time qPCR using the methods described in Heid et al 1996 (discussed above) and an SRY TaqMan system consisting of amplification primers for the SRY region on the Y chromosome and a dual-labelled fluorescent TaqMan probe. The primer/probe combinations were designed using the Primer Express software and Sequence data for the SRY gene were obtained from the GenBank Sequence database (page 11, lines 19 to 21 of the Patent).

55 In the discussion of the results the specification says (page 14 lines 18 to 25):

In this study we demonstrate that the concentration of foetal DNA in maternal serum is elevated in aneuploid pregnancies. These results indicate that foetal DNA quantitation has the potential to be used as a new screening marker for foetal chromosomal aneuploidies. A large scale population-based study could be carried out to develop cutoff values for screening purposes. It would also be useful to investigate the correlation of foetal DNA concentration with the other biochemical markers for maternal serum biochemical screening.

56 Example 3 is entitled “Non-invasive prenatal determination of foetal RhD status from plasma of RhD-negative pregnant women”. It is a qualitative test.

57 By way of background, the Rhesus factor (also known as the RhD antigen) was known to be a protein found on the surface of red blood cells in Rh positive individuals. Rh negative individuals lack this protein, because of a mutation of the gene. Rh disease can cause haemolytic disease of the newborn and foetus and typically arises in the second or subsequent pregnancies when a Rh negative mother is carrying a Rh positive foetus, and the foetus expresses the Rh factor on its red blood cells. During pregnancy and birth the mother may be exposed to those red blood cells, and then her immune system mounts a response to Rh factor, which it identifies as foreign, and that response sensitises her immune system to Rh factor. That sensitisation may result in the destruction the red blood cells of a Rh positive foetus in subsequent pregnancies. It was routine to test mothers for Rh status and to treat mothers identified as Rh negative with anti-Rh factor antibodies to prevent an immune response being raised. This was inefficient, because it involved treating Rh negative mothers who did not need it because they were not carrying a Rh positive foetus.

58 The specification says that a number of groups have investigated the possibility of using foetal cells in maternal blood for the determination of foetal RhD status, but that the system is not sufficiently reliable without foetal cell enrichment or isolation procedures, which are tedious and expensive to perform (page 15 line 26 to page 16 line 3). It says (page 16 lines 4 to 6):

Our discovery of the presence of foetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum offers a new approach for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis.

59 The primary judge summarised the method then described at [272]:

In the project the subject of Example 3, blood samples were taken from 21 serologically RhD negative pregnant women, including some who were in the second trimester of pregnancy just prior to amniocentesis and others who were in the third trimester just before delivery (page 16, lines 13 to 17). No blood or DNA samples were taken from fathers. 800µL of plasma was used for cffDNA analysis (page 17, line 5), which was performed as described in Example 2 with modifications relating to the primer/probe sets. The Example 3 method also included a non-fetal specific beta-globin TaqMan system, which acted as a control for the presence and amplifiability of cell free DNA in the plasma samples (page 19, lines 1 to 3).

60 The discussion of the example provided in the specification says (page 19 lines 6 to 13):

In this study we have demonstrated the feasibility of performing non-invasive foetal RhD genotyping from maternal plasma. This represents the first description of single gene diagnosis from maternal plasma. Our results indicate that this form of genotyping is highly accurate and can potentially be used for clinical diagnosis. This high accuracy is probably the result of the high concentration of foetal DNA in maternal plasma.

61 Example 4 is entitled “Elevation of foetal DNA concentration in maternal serum in pre-eclamptic pregnancies” and focuses on a quantitative test.

62 It was known before the priority date that pre-eclampsia is a pregnancy disorder which affects about 6% of pregnancies and is characterised by high blood pressure and elevated protein levels in the maternal urine. Pre-eclampsia generally occurs 24 to 26 weeks after fertilisation and often increases in severity until birth. Untreated, pre-eclampsia may lead to eclampsia (convulsions), bleeding in the mother’s brain and death of the mother. The early forms of pre-eclampsia are often associated with foetal growth restriction due to placental dysfunction.

63 In this example, the inventors used a real-time qPCR assay to show that the concentration of foetal DNA in the serum of women suffering from pre-eclampsia was elevated compared to normal pregnancies. Y chromosomal sequences from male foetuses were used as a foetal marker and a proxy for the total level (concentration) of foetal DNA (page 21 lines 5 to 9). Serum/plasma samples were taken from women with and without pre-eclampsia and real-time qPCR was performed as described in example 2 (page 22 line 6 to 7). The results indicated that the concentration of foetal DNA is higher in pre-eclamptic compared with non-pre-eclamptic pregnancies and that foetal DNA concentration measurement in maternal plasma may be used as a new marker for pre-eclampsia (page 22 lines 20 to 23). The specification says that compared with other markers, foetal DNA measurement is a genetic marker, which has the advantage that it is completely foetal-specific (page 22 lines 24 to 28).

64 Example 5 is entitled “Quantitative analysis of foetal DNA in maternal plasma and serum”. It commences by citing an article by Lo et al, 1997 for the proposition that the inventors have demonstrated that foetal DNA is present in maternal plasma and serum, with the detection of foetal DNA sequences in 80% and 70% of cases using only 10 µl of boiled plasma and serum respectively (page 23 lines 18 to 21). It says that these observations indicate that maternal plasma/serum DNA may be a useful source of material for the non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of certain genetic disorders, but that foetal DNA needs to be shown to be present in sufficient quantities for reliable molecular diagnosis to be carried out, and data on the variation of foetal DNA with regard to gestation age is required to determine the applicability of the technology to early prenatal diagnosis (page 23 lines 22 to 30).

65 For convenience we repeat claim 1, which provides:

A detection method performed on a maternal serum or plasma sample from a pregnant female, which method comprises detecting the presence of a nucleic acid of foetal origin in the sample.

66 Claim 2 is the method according to claim 1, “comprising amplifying the foetal nucleic acid to enable detection”.

67 Claim 3 is the method according to claim 2, “wherein the foetal nucleic acid is amplified by the polymerase chain reaction”.

68 Claim 5 is relevantly the method according to any one of claims 1 to 3, “wherein the foetal nucleic acid is detected by means of a sequence specific probe”.

69 Claim 6 is relevantly the method according to any one of the above claims, “wherein the presence of a foetal nucleic acid sequence from the Y chromosome is detected”.

70 Claim 9 is the method according to any one of claims 1 to 5, “wherein the presence of a foetal nucleic acid from a paternally-inherited non-Y chromosome is detected”.

71 Claim 13 is relevantly the method according to claim 6, “for determining the sex of the foetus”.

72 Claim 14 is relevantly the method according to claims 6 or 9, which comprises “determining the concentration of the foetal nucleic acid sequence in the maternal serum or plasma.”

73 Independent claim 22 is “A method of performing a prenatal diagnosis, which method comprises the steps of”:

(i) providing a maternal blood sample;

(ii) separating the sample into a cellular and a non-cellular fraction;

(iii) detecting the presence of a nucleic acid of foetal origin in the non-cellular fraction according to the method of any one of claims 1 to 21;

(iv) providing a diagnosis based on the presence and/or quantity and/or sequence of the foetal nucleic acid.

74 Claim 23 is the method according to claim 22, “wherein the non-cellular fraction as used in step (iii) is a plasma fraction”.

75 Independent claim 25 is:

A method of performing a prenatal diagnosis on a maternal blood sample, which method comprises removing all or substantially all nucleated and anucleated cell populations from the blood sample and subjecting the remaining fluid to a test for foetal nucleic acid indicative of a maternal or foetal condition or characteristic.

4.1 The decision of the primary judge

76 The primary judge commenced by referring to s 18(1)(a) of the Act and then providing a detailed review of the law concerning patentable subject matter, commencing with the decision of the High Court in D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc [2015] HCA 35; 258 CLR 334. It is convenient here to set out the reasoning of the plurality in Myriad at [28]:

A number of factors may be relevant in determining whether the exclusive rights created by the grant of letters patent should be held by judicial decision, applying s 18(1)(a) of the Act, to be capable of extension to a particular class of claim. According to existing principle derived from the NRDC decision, the first two factors are necessary to characterisation of an invention claimed as a manner of manufacture:

1. Whether the invention as claimed is for a product made, or a process producing an outcome as a result of human action.

2. Whether the invention as claimed has economic utility.

When the invention falls within the existing concept of manner of manufacture, as it has been developed through cases, they will also ordinarily be sufficient. When a new class of claim involves a significant new application or extension of the concept of "manner of manufacture", other factors including factors connected directly or indirectly to the purpose of the Act may assume importance. They include:

3. Whether patentability would be consistent with the purposes of the Act and, in particular:

3.1. whether the invention as claimed, if patentable under s 18(1)(a), could give rise to a large new field of monopoly protection with potentially negative effects on innovation;

3.2. whether the invention as claimed, if patentable under s 18(1)(a), could, because of the content of the claims, have a chilling effect on activities beyond those formally the subject of the exclusive rights granted to the patentee;

3.3. whether to accord patentability to the invention as claimed would involve the court in assessing important and conflicting public and private interests and purposes.

4. Whether to accord patentability to the invention as claimed would enhance or detract from the coherence of the law relating to inherent patentability.

5. Relevantly to Australia's place in the international community of nations:

5.1. Australia's obligations under international law;

5.2. the patent laws of other countries.

6. Whether to accord patentability to the class of invention as claimed would involve law-making of a kind which should be done by the legislature.

Factors 3, 4 and 6 are of primary importance. Those primary factors are not mutually exclusive. It may be that one or more of them would inform the "generally inconvenient" limitation in s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies. It is not necessary to consider that question given that no reliance was placed upon that proviso. They are nevertheless also relevant to the ongoing development of the concept of "manner of manufacture".

77 The primary judge relied upon and repeated his reasoning in Meat & Livestock Australia Limited v Cargill, Inc [2018] FCA 51; 354 ALR 95 (MLA (No 1)) for a general exposition of the relevant law. He then summarised in detail the submissions advanced on behalf of the appellants before turning to his analysis. He observed that in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 50; 253 CLR 284 Crennan and Kiefel JJ at [224] noted that:

In Australian law, the starting point is the recognition in the NRDC Case that any attempt to define the word “manufacture” or the expression “manner of manufacture”, as they occur in s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, is bound to fail.

78 The primary judge noted that it was significant in the present case that there is no claim to the product or presence of cffDNA, but rather to a method by which the discovery of the existence of cffDNA can be put to practical use. In this way, his Honour considered that the subject matter of the relevant claims can be seen to fall within the principles of National Resource Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents [1959] HCA 67; 102 CLR 252 (Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ) (NRDC) and affirmed in Myriad, whilst not falling within the impermissible product claims rejected in Myriad (at [463]).

79 The primary judge noted that pursuant to Myriad the starting point for the resolution of the issue is the identification of what in substance each claim is for. In this regard the primary judge first noted:

[467] ... the Patent is entitled “Non-invasive prenatal diagnosis”. The first paragraph of the Patent provides that the invention described and claimed therein “relates to prenatal detection methods using non-invasive techniques” and “[i]n particular, it relates to prenatal diagnosis by detecting foetal nucleic acids in serum or plasma from a maternal blood sample.”

[468] The Patent describes (page 1) the prenatal testing methods used before the priority date of the invention, including CVS and amniocentesis, being techniques requiring careful handling and that present a degree of risk to the mother and to the pregnancy, and the use of fetal cells in maternal blood.

80 The primary judge then quoted the passage at page 2 lines 5 to 19 of the specification (which we have summarised and quoted at [35] above), and at [470] said that the patent specification confirms at page 2 lines 20 to 23 that the invention is:

… not simply the presence of cffDNA in maternal serum or plasma but rather, “a detection method performed on a maternal serum or plasma sample from a pregnant female, which method comprises detecting the presence of a nucleic acid of foetal origin in the sample”. It is explained that the claimed method thus provides a “method of prenatal diagnosis”, a term defined at page 2, line 24 to page 3, line 4.

81 Earlier, at [215], the primary judge had characterised the invention:

The inventors named in the Patent, Dr Dennis Lo and Dr James Wainscoat had discovered the presence and utility of cffDNA. The invention described and claimed in the Patent is the practical application of this discovery by a new method of detection of fetal DNA, which unlike previously disclosed cellular methods, involved human mediated discrimination between cell-free maternal and fetal DNA in an artificially prepared plasma or serum sample extracted from a pregnant female.

(emphasis in original)

82 He then identified at [472] to [476] that there are four classes of claims. The first is a detection method as set out with increasing detail in independent claim 1 and dependent claims 2, 3, 5, 6 and 9. The second is a detection method within the first class for determining the sex of a foetus in dependent claim 13. The third is a method of the first class which further comprises determining the concentration of foetal nucleic acid sequences in the maternal serum or plasma sample in dependent claim 14, and the fourth is the provision of a “prenatal diagnosis” following the performance of the method in the first class in independent claim 22 and dependent claims 23, 25 and 26.

83 The primary judge distinguished the present case on its facts from Myriad finding (at [477]):

It should be well apparent that unlike Myriad, this case does not concern whether product claims to naturally occurring nucleic acid molecules per se or naturally occurring genetic information encoded by such sequences are patentable. Rather, like MLA (No 1), this case concerns method claims (MLA (No 1) at [409] and [462]). Both MLA (No 1) and the present case involve claims to methods of identifying or detecting a nucleic acid having a particular characteristic, not the nucleic acids or the information encoded by such nucleic acids per se.

(emphasis in original)

84 The primary judge noted that the detection method of claims 6 to 9 inherently involve at least artificial steps requiring human action (at [480]) and that a person seeking to detect cffDNA from maternal serum or plasma would necessarily be deliberately employing the method invented and claimed. As such, a method of detection would involve the use of artificial human action, such as PCR in the case of claim 3 or probes in the case of claim 5 (at [482]).

85 In relation to the inventive concept underlying the invention as disclosed in the specification the primary judge said at [481]:

Further, all uses of the relevant method(s) would be commensurate with the scope of the inventor’s claimed new method of prenatal detection involving the detection of cffDNA from a maternal serum or plasma sample, rather than existing methods which all focused on more problematic cellular (as distinct from non-cellular) samples of DNA. The claims cover what the inventors of the Patent invented. In other words, the inventive step or concept, that is, that paternally inherited cffDNA is detectable in maternal plasma or serum, is the subject of and is carried out in, for example, claims 6 and 9.

(emphasis in original)

86 In this regard at [484] the primary judge drew upon the evidence in the joint expert report, where the experts agreed that “detect” in context means:

... demonstrating the presence of non-maternal nucleic acid that is inferred to be of fetal origin. It is difficult to see how it could sensibly be said that such a method does not involve artificial human action to discriminate or distinguish between nucleic acids of maternal origin and non-maternal (i.e. fetal) origin. Moreover, without such a step, one cannot detect the presence of non-maternal (i.e. fetal) nucleic acid.

87 The primary judge accepted the submission advanced by the respondent that the substance of the method applies and follows from, but is different to, the identification of a natural phenomenon, namely the presence of cffDNA in maternal blood. This, he considered, is made clear by page 16 lines 4 to 6 of the specification which explain that the discovery “offers a new approach for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis”. The primary judge found at [485]:

Thus, the invention builds on, uses, practically applies and reduces to practice a discovered substance found in nature, namely, cffDNA in maternal blood, to provide a new, inventive, useful, artificial method of detection of cffDNA, and where the method is of economic significance.

88 The primary judge then addressed claims 13 and 14 and concluded that they provide for the practical application of the discovery of cffDNA in maternal plasma and that claims 22, 23, 25 and 26, founded as each is on “prenatal diagnosis”, are on any view a manner of manufacture (at [486], [487]).

89 The primary judge next turned to what he described as the “inventive concept”. After quoting from NRDC at 262 and 264, he said at [491]:

Now in my view there is no requirement that the inventive concept be seen to make a contribution to the essential difference between the product and nature. But even if I were to conclude otherwise, the inventive concept of the Patent does so. In nature, the presence of cffDNA in the maternal blood has not and cannot be detected without human action. Accordingly, unlike the claims considered in Myriad, the invention claimed adds to human knowledge and involves the suggestion of an act to be done which results in a new result, or a new process.

90 The primary judge considered the question of whether the claimed invention was for an artificially created state of affairs. In a passage criticised by the appellants on appeal the primary judge said at [494]:

In the present case the relevant claims involve human interaction and the creation of an artificially created state of affairs discernible by an observer. The artificially created state of affairs is the detection of cffDNA in the tested sample. This “product” is, by definition the result of human action and is not naturally occurring. The inventive method does not simply produce an abstract, intangible situation. It is not just the “information” encoded by the naturally occurring cffDNA itself. Moreover, production of the result requires at least:

(a) The taking of a maternal blood sample from a pregnant female.

(b) The separation of the maternal blood sample into its component parts, namely, plasma, white blood cells and red blood cells. It is obvious that such samples do not exist in the natural world. They must be artificially created by centrifuging a sample of blood to remove all cells in the presence of an anti-coagulant in the case of plasma, or without an anti-coagulant but after clotting in the case of serum.

(c) The extraction of nucleic acids from the plasma component of a maternal blood sample.

(d) A step to discriminate between maternal and cffDNA in the sample, such as, the targeting and amplification by PCR of paternally inherited sequences from the Y chromosome in the case of claim 6 and a non-Y chromosome in the case of claim 9.

91 Next, the primary judge concluded that the invention is of economic significance, again distinguishing Myriad, because unlike in that case here the claim is not to the nucleic acid isolate or merely a step along the way to another method claimed (at [499]), but a method that provides a significant advantage over existing foetal DNA detection methods (at [500]). His Honour continued at [503]:

In my view the claimed invention falls clearly within the concept of manner of manufacture described by the High Court in NRDC, satisfies the first two criteria identified in Myriad at [28] and is therefore patentable. But even if the substance of the invention is considered to fall outside the established boundaries of patentable subject matter, consideration of the non-exhaustive list of additional factors outlined in Myriad confirms my opinion of the invention’s patentability.

92 Despite his finding that the invention fell clearly within the first two factors identified in Myriad, his Honour nevertheless turned to consider the other factors. In relation to factor 3, he considered that there would be no chilling effect as the boundaries of the claims are clear and commensurate with the invention described in the patent, and there was no risk that someone could infringe the patent without knowing it (at [506]-[509]). In relation to factor 4, his Honour noted that his findings were consistent with MLA (No 1) and would accordingly promote consistency in the application of the law (at [511]-[517]). In relation to factor 5, at [519] his Honour noted that in corresponding proceedings in the United Kingdom Carr J held that claims equivalent to claims 6 and 9 were patentable (Illumina, Inc v Premaitha Health Plc [2017] EWHC 2930 (Pat) at [184] to [189]), but also observed at [522]-[525] that in the corresponding United States proceedings the majority of the Supreme Court took a different view (Ariosa Diagnostics Inc. Sequenom, Inc. 788 F3d 1371 (3d Cir 2015) (Ariosa (US)). The primary judge distinguished the US court’s findings on the basis that the court had approached the claims by dissecting integers, which was not the correct approach under Australian law.

93 The primary judge concluded on the subject of manner of manufacture at [526]:

The Patent does not simply claim the discovery of cffDNA in maternal blood. Rather, it claims a new and inventive practical application of the discovery comprising a method requiring human action to detect, in an artificially created sample of maternal plasma or serum, a DNA sequence as being of fetal rather than maternal origin. And prior to the invention, no-one had worked or was working a method comprising the detection of cffDNA in plasma or serum samples extracted from pregnant females.

94 The appellants contend broadly in ground 1 of the appeal that the primary judge erred in finding that the relevant claims are for an invention that is a manner of manufacture within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1624 (21 Jac c 3) and s 18(1)(a) of the Act. They elaborate in grounds 2 to 5 by contending that the primary judge ought to have found that the end result of each claim does not, at all or sufficiently, involve an artificial effect or an artificially created state of affairs, but rather involves the detection of what is naturally occurring, and that in substance each of the relevant claims is to a mere discovery. The appellants further contend that the primary judge erred in finding that the alleged invention does not concern a new class of claim and that accordingly there was no need to apply the “other factors” identified by the plurality in Myriad, and in finding in any event (at [506]-[525]) that those factors confirm the patentability of the invention claimed.

95 The appellants submit that the invention claimed in the relevant claims does not involve a manner of manufacture because what is claimed is a mere discovery of a naturally occurring phenomenon, and not a method involving a practical application that in substance goes beyond the discovery itself, and as a result there is no artificially created state of affairs. In a related submission, the appellants contend that properly understood the end result of each claim is information only and, accordingly, not an artificially created state of affairs.

96 The appellants submit that as at the priority date it was known that foetal DNA could provide valuable information about the foetus, and it was known that foetal DNA for analysis could be obtained by an invasive sampling method, such as amniocentesis or CVS. Another known source of foetal DNA was the foetal cells that were circulating in the mother’s blood, albeit in very low concentration. The cffDNA from maternal plasma or serum, once its existence was discovered, was another source of foetal DNA from these other known sources.

97 The appellants submit that the primary judge’s findings at [494] (set out in section 4.1 above) miss the point, because the claims are not directed to a new method of obtaining a plasma or serum sample from maternal blood. Rather, in this case, although human action may be involved in the performance of the claimed methods, the end result or outcome of the method as claimed is simply the information, namely the presence of cffDNA discovered by Professor Lo. They summarise the reasons of the plurality in Myriad as, in characterising an invention as a manner of manufacture, requiring consideration of the question “whether the invention as claimed is for a product made, or a process producing an outcome as a result of human action” (at [28]), which is to be answered by reference to whether the invention yields an “outcome which can be characterised, in the language of NRDC, as an ‘artificially created state of affairs’” (at [6]). In this regard the appellants also rely on the decisions of the Full Court in Research Affiliates LLC v Commissioner of Patents [2014] FCAFC 150; 227 FCR 378 (Kenny, Bennett and Nicholas JJ) at [8], [92], [95], [103], [106] and [115], Commissioner of Patents v RPL Central Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 177; 238 FCR 27 (Kenny, Bennett and Nicholas JJ) at [95] and Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; 379 ALR 86 (Rares, Nicholas and Burley JJ) at [89].

98 The appellants submit that in the present case the substance of what has been invented is simply the information about the DNA of the foetus, which is no more than naturally occurring information. By focussing on the process used to obtain the information the appellants submit that the primary judge failed to look at the “end result” and ask whether that end result involved an artificial effect. In this regard, the primary judge is said to have failed to apply the reasoning of Gageler and Nettle JJ in Myriad at [152].

99 The appellants contend that while the claims of the patent are drafted as methods of detection or diagnosis, in substance none does more than Professor Lo’s discovery that cffDNA is detectable in maternal serum or plasma. In this respect, claim 1 does no more than claim Professor Lo’s discovery that cffDNA is detectable in maternal serum or plasma by “detecting the presence of a nucleic acid of foetal origin”. The discovery only of the presence of a naturally occurring phenomenon, being the presence of foetal DNA in maternal plasma or serum, is not an invention. The appellants emphasise that there is no claim in the patent to any new method for detecting cffDNA once it is discovered to be present in the plasma or serum, it being accepted in the statement of common general knowledge in these proceedings that the methods so used were well-known by the priority date.

100 The appellants submit that unlike the claims in MLA (No 1), the claims here do not claim any specific or new method of applying the detectability of cffDNA in maternal plasma or serum, but simply claim the identification or discernment of the naturally occurring phenomenon of the presence of cffDNA in maternal plasma or serum. The dependent claims are merely broad examples of how to detect cffDNA in maternal plasma, using well-understood and conventional activity.

101 Each of claims 6 and 9 specifies the chromosome from which the foetal nucleic acid to be detected is derived, but taken together they cover all foetal chromosomes that are paternally-inherited and which may therefore be distinguishable from the maternal DNA if a sequence can be identified that is not possessed by the mother. So considered, claims 6 and 9 do not effectively limit the scope of claims 1 to 3 or 5, they only identify the subsets of foetal nucleic acids which might be detected in those latter claims.

102 The appellants further submit that claim 13 is the first and only asserted claim that involves a specific application of the discovery, involving a method “for determining the sex of the foetus”, but this conclusion follows so directly from the discovery itself, that it involves nothing more than the discovery; knowing that foetal DNA is present, a known probe is used to determine whether sequences from the Y chromosome are present or not. Claim 14 requires the concentration of the foetal nucleic acid in the maternal serum or plasma to be determined. It requires detecting the presence of foetal nucleic acid and measuring how much is there. The claim is not directed to any application of that information and so similarly does not give rise to a manner of manufacture. The appellants submit that independent claims 22 to 26 involve making a prenatal diagnosis, and whilst in form these claims might appear to involve a practical application of the discovery, in substance these claims are still merely for the identification or discernment of the naturally occurring phenomenon because the claims say nothing as to the method of arriving at a diagnosis, nor as to the diagnosis to be made, and consequently provide no relevant limitation. In substance they are to the discovery itself.

103 The appellants submit that even if the claims would satisfy the threshold requirements of NRDC the claims are still not patentable as they are not within the established boundaries of what constitutes patentable subject matter, having regard to the additional factors identified by the plurality in Myriad at [28].

104 The respondent distinguishes the decision in Myriad by noting that the relevant claims are not product claims to isolated nucleic acids, or naturally occurring “genetic information” encoded by such sequences. Nor do they claim cffDNA itself. Rather, the claims concern the application of the discovery of the existence of cffDNA by the inventors, and their invention of new methods of non-invasive detection of foetal DNA from a maternal serum or plasma sample and prenatal diagnosis. The respondent submits that the claimed method must be considered as a whole. It is not to the point that once it was discovered that foetal DNA was present in extracellular maternal serum or plasma samples such DNA could be detected using known biotechnical methods. The steps involved in implementing the method were correctly found by the primary judge to be part of the claimed method, and cannot be disaggregated from it. Prior to the invention, skilled persons sought to detect foetal DNA by invasive methods or by seeking to extract foetal DNA from foetal cells within the cellular component of maternal blood, but before the priority date no one had amplified and detected cffDNA in maternal plasma and serum samples.

105 The respondent submits that for a conclusion that a claim is the proper subject matter for a patent it will normally suffice to find that the claim is for an invention that gives rise to “something brought about by human action” (citing Myriad at [6] (plurality)) or a discernible artificially created state of affairs (NRDC at 277, MLA (No 1) at [455]) or something of economic significance. The present case falls within these categories and it is unnecessary to consider whether the claims concern a new class of claim requiring consideration of the “other factors” identified by the plurality in Myriad at [28].

106 The respondent contends that the reasons in Myriad support the contention that detection and diagnosis methods are patentable subject matter, and submits that the substance of the invention is a method resulting in an artificially created state of affairs producing an economically significant outcome. It submits this in relation to each of the asserted claims, but advances a composite exemplar detection method claim to demonstrate its point, being claims 6 and 9 when dependent on claims 2, 3 and 5:

A method of detecting in a maternal plasma sample prepared from blood extracted from a pregnant female, the presence of a foetal nucleic acid sequence [claim 6: from the Y chromosome or claim 9: from a paternally-inherited non-Y chromosome], wherein the foetal nucleic acid is amplified by the polymerase chain reaction and the foetal nucleic acid is detected by means of a sequence specific probe.

107 After defending the primary judge’s reasoning in respect of each of the asserted claims, the respondent turns to the “other factors” identified by the plurality in Myriad at [28] and contends that, to the extent that it is necessary to apply them, the primary judge correctly considered that they pointed in favour of patentability.

108 Fundamental to the appeal is the contention that what is claimed is a mere discovery of a naturally occurring phenomenon, and not a method involving a practical application that goes beyond the discovery itself. Here, the appellants identify the discovery as the fact that cffDNA from maternal plasma or serum was a source of foetal DNA. They submit that there is no artificially created state of affairs arising from the invention as claimed. Furthermore, they submit that the “end result” of each claim results in information only, being the detection of cffDNA. The appellants rely substantially on the decision in Myriad in support of their appeal.

109 For an invention to be patentable, it must meet the relevant requirements of the Act including s 18(1)(a) which requires that the invention, as claimed, be a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies. Schedule 1 to the Act defines “invention” as “any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention”. This element of patentability was considered in NRDC, Apotex and more recently in Myriad.

110 According to NRDC, as explained in Myriad, the relevant question to be posed is: “Is this a proper subject of letters patent according to the principles which have been developed for the application of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies?” (Myriad at [18] (plurality), citing NRDC at 269).

111 The common law has developed standards by which patentable subject matter may be assessed by reference to the determination of what is a manner of manufacture. In NRDC Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ emphasised the long-established requirement that a patentable invention must involve more than mere discovery of a scientific fact or law of nature. However, at 263-264 they counselled caution in too quickly using such distinctions, quoting Frankfurter J in the United States Supreme Court decision Funk Bros. Seed Co v Kalo Inoculant Co (1948) 333 US 127 at 134, 135 (92 Law Ed 588, at 591), where his Honour said:

It only confuses the issue ... to introduce such terms as ‘the work of nature’ and the ‘laws of nature’. For these are vague and malleable terms infected with too much ambiguity and equivocation. Everything that happens may be deemed ‘the work of nature’, and any patentable composite exemplifies in its properties ‘the laws of nature’. Arguments drawn from such terms for ascertaining patentability could fairly be employed to challenge almost any patent.

112 Their Honours continued in NRDC at 264:

The truth is that the distinction between discovery and invention is not precise enough to be other than misleading in this area of discussion. There may indeed be a discovery without invention – either because the discovery is of some piece of abstract information without any suggestion of a practical application of it to a useful end, or because its application lies outside the realm of “manufacture”. But where a person finds out that a useful result may be produced by doing something which has not been done by that procedure before, his claim for a patent is not validly answered by telling him that although there was ingenuity in his discovery that the materials used in the process would produce the useful result no ingenuity was involved in showing how the discovery, once it had been made, might be applied. The fallacy lies in dividing up the process that he puts forward as his invention. It is the whole process that must be considered: and he need not show more than one inventive step in the advance which he has made beyond the prior limits of the relevant art.

113 The Court went on to explain this point by reference to the distinction between a mere idea and its application by reference to Watt’s invention of the use to which steam may be put (at 264):

This is perhaps nowhere more clearly put than it was by Fletcher Moulton LJ in Hickton’s Patent Syndicate v Patents and Machine Improvements Co Ltd when he said of Watt’s invention for the condensation of steam, out of which the steam engine grew: “Now can it be suggested that it required any invention whatever to carry out that idea when once you had got it? It could be done in a thousand ways and by any competent engineer, but the invention was in the idea, and when he had once got that idea, the carrying out of it was perfectly easy. To say that the conception may be meritorious and may involve invention and may be new and original, and simply because when you have once got the idea it is easy to carry it out, that that deprives it of the title of being a new invention according to our patent law, is, I think, an extremely dangerous principle and justified neither by reason nor authority”.

(citations omitted)

114 Three points of emphasis may be noted from these passages. First, the distinction between mere discovery and an invention lies in its practical application to a useful end. Secondly, it is important that the invention be considered as a unitary concept, not segregated artificially into parts. The invention may arise from an idea and then be applied in a perfectly well known way, and yet the combined effect of the idea and its application may result in patentable subject matter, as arose from the example described in Hickton’s Patent Syndicate v Patents and Machine Improvements Co Ltd (1909) 26 RPC 339. The approach of the appellants in the present appeal, which seeks to disaggregate the discovery of cffDNA in maternal plasma or serum from the method used to harness that discovery, tends to overlook these matters. Thirdly, an invention may reside in an abstract idea, such as the condensation of steam that is then put to a useful end, even though the way of putting it to that end can be carried out in many useful ways, all of which are otherwise known.

115 In Apotex the High Court considered whether methods of treatment of the human body using a known substance would amount to a manner of manufacture. At [230] Crennan and Kiefel JJ referred to an earlier passage at 264 in the NRDC case:

In determining that a novel use of known substances (for the eradication of weeds from crops) was a patentable invention, this Court (Dixon CJ, Kitto and Windeyer JJ) decided that it was not essential that a process produce or improve a vendible article. Their Honours explained, by reference to the doctrine of analogous uses set out in BA's Application:

"If ... the new use that is proposed consists in taking advantage of a hitherto unknown or unsuspected property of the [known] material ... there may be invention in the suggestion that the substance may be used to serve the new purpose; and then, provided that a practical method of so using it is disclosed and that the process comes within the concept of patent law ultimately traceable to the use in the Statute of Monopolies of the words 'manner of manufacture,' all the elements of a patentable invention are present ... It is not necessary that in addition the proposed method should itself be novel or involve any inventive step".

(emphasis added, citations omitted)

116 Later, their Honours considered and approved the reasoning of Lockhart J in Anaesthetic Supplies Pty Limited v Rescare Limited [1994] FCA 304; 50 FCR 1 at 19. At [240] their Honours said:

In the majority, Lockhart J found that once the notion of the necessity for a vendible product (as in Re C & W's Application) is eliminated (as it was in the NRDC Case), there is no distinction in principle between a product for treating humans and a method for treating humans. ... His Honour said:

“I see no reason in principle why a method of treatment of the human body is any less a manner of manufacture than a method for ridding crops of weeds as in NRDC. Australian courts must now take a realistic view of the matter in the light of current scientific development and legal process; the law must move with changing needs and times ...

If a process which does not produce a new substance but nevertheless results in ‘a new and useful effect’ so that the new result is ‘an artificially created state of affairs’ providing economic utility, it may be considered a ‘manner of new manufacture’ within s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies”.

(emphasis added in Apotex, citations omitted)

117 Claim 1 in issue before the Court in Apotex was for a method of preventing or treating psoriasis, and claimed a previously unknown therapeutic use of a pharmaceutical substance which was known for other therapeutic uses disclosed in an earlier patent (at [276]). The Court rejected a submission that the subject matter of the claim was “essentially non-economic” (French CJ at [50], Crennan and Kiefel JJ at [277], Gageler J at [314]). Crennan and Kiefel JJ provided seven reasons for this conclusion at [278]-[285] (with which Gageler J agreed at [314]). Two aspects are presently material. In the first, their Honours noted at [278] that the requirement that an invention have “economic utility” raises the same considerations as those applicable in the UK and Europe that an invention be susceptible or capable of industrial application. This was, they said, apparent from the definition of “exploit” in the Act.

118 The reference to that definition serves to emphasise the distinction between product and method claims and, in respect of method claims, to demonstrate that a “product” in the sense of a tangible thing is not required for patentability. In this respect, the plurality in Myriad noted at [16] that the definition of "exploit" distinguishes “between an invention which is a product and an invention which is a method or process which may or may not yield a product” (emphasis added). They noted that in Northern Territory v Collins [2008] HCA 49; 235 CLR 619 at [18] Gummow ACJ and Kirby J “linked that distinction to the way in which, over time, the expression ‘manner of manufacture”’ had been construed to include the practice and means of ‘making’, as well as its product, which would include an economically useful outcome effected by an inventive method” (emphasis added).

119 In the fourth aspect discussed by Crennan and Kiefel JJ, their Honours said at [282]:

... the subject matter of a claim for a new product suitable for therapeutic use, claimed alone (a product claim) or coupled with method claims (combined product/method claims), and the subject matter of a claim for a hitherto unknown method of treatment using a (known) product having prior therapeutic uses (a method claim), cannot be distinguished in terms of economics or ethics. In each case the subject matter in respect of which a monopoly is sought effects an artificially created improvement in human health, having economic utility. It could not be said that a product claim which includes a therapeutic use has an economic utility which a method or process claim for a therapeutic use does not have. It could not be contended that a patient free of psoriasis is of less value as a subject matter of inventive endeavour than a crop free of weeds. Patent monopolies are as much an appropriate reward for research into hitherto unknown therapeutic uses of (known) compounds, which uses benefit mankind, as they are for research directed to novel substances or compounds for therapeutic use in humans. It is not possible to erect a distinction between such research based on public policy considerations.

(emphasis added)

120 In their concluding remarks in relation to patentability, Crennan and Kiefel JJ noted at [287] that the expression “essentially non-economic” came from the requirement that the subject matter of a patent must have useful application in the sense that it must be capable of being practically applied in commerce or industry in the sense of being “susceptible or capable of industrial application”. These observations serve to reinforce the proposition that it is not necessary for a method or process claim to have as its outcome or result a tangible product or output in order to be a method that produces an economically useful outcome. What is necessary is that there be “a new and useful effect”.

121 The decision of the High Court in Myriad concerned the inherent patentability of a claim to an isolated DNA sequence that mirrored naturally occurring genetic information. Although three claims were in issue, it is sufficient to refer for present purposes to claim 1, which was in the following terms: