Federal Court of Australia

Ambrose v Commonwealth of Australia [2021] FCAFC 88

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

Collier, griffiths and abraham jJ | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 This appeal is from a single judge of the Court who dismissed an application for judicial review under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act). As is made clear in the amended originating application for judicial review, the applicant below (whom we shall refer to as the appellant) sought judicial review of what he described as the conduct of the first respondent in “refusing to review any decision made by a delegate of the Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business (DESSFB) in relation to the suspension of Newstart allowance (NSA)”. In particularising that claim, the appellant said that Centrelink had refused to review a decision by his employment service provider (ESP) to suspend his Newstart allowance. He complained that Centrelink’s refusal blocked his right to have the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) review that decision. The appellant complained that the conduct constituted a denial of natural justice and also amounted to a failure to observe procedures required by law. He sought a declaration that all actions taken in relation to the conduct “be invalid”.

2 For the reasons that follow, the appeal should be dismissed, with costs.

3 It is convenient first to outline the background facts, then summarise the primary judge’s reasons for judgment before addressing the grounds of appeal.

Summary of background matters

4 The appellant is a law student. He received Newstart payments for several years (Newstart is now known as Jobseeker). Under s 593(1)(e) of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth) (Social Security Act), an applicant for Newstart could be required to enter into an employment pathway plan (job plan). The purpose of such a plan was to document the obligations of a Newstart recipient. A failure to comply with a job plan requirement (such as failing to attend an appointment or failing to satisfy a job search requirement in the plan) could amount to a “mutual obligation failure” for the purposes of s 42AC of the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 (Cth) (Social Security (Administration) Act). Where a person committed a mutual obligation failure, the “usual rule” under s 42AF was that the Secretary of the Department of Human Services (Department) was obliged to determine that the person’s “participation payment” (as defined in the Dictionary) was not payable during the relevant period (s 42AF(1)(a) of the Social Security (Administration) Act). There was also a “special rule” from which more severe consequences flowed (such as reduction of allowance or cancellation) if the Secretary was also satisfied for the purposes of s 42AF(2) (and via s 42AF(1)(b)) that the person had “persistently committed mutual obligation failures”.

5 The Secretary’s power under s 42AF(1)(a) to suspend Newstart payments was delegated under s 234(7) of the Social Security (Administration) Act to certain persons, including private sector organisations who were known as ESPs (see item 2 of the Schedule to the Social Security (Administration) (Secretary of the Department of Jobs and Small Business) Delegation (No. 1) 2019 (Cth) (Delegation)). It is notable that the Secretary’s power and function under ss 42AF(1)(b) and (2) were not delegated to ESPs.

6 The suspension period affecting the appellant’s Newstart payments was calculated under s 42AL of the Social Security (Administration) Act. That provision provided two ways by which the payment suspension period ended. The first (s 42AL(3)(a)) operated so as to have the payment suspension period end immediately before the day the person whose Newstart payments had been suspended complied with the “reconnection requirement” imposed under s 42AM(1). This avenue only applied where the second avenue did not apply. The second avenue (s 42AL(3)(b)) operated to end the payment suspension period at an earlier time if the Secretary determined that an earlier day was more appropriate. It may be interpolated here that the Secretary’s power to determine that an earlier day was more appropriate was also delegated to ESPs under the Delegation referred to immediately above.

7 Part 4 of the Social Security (Administration) Act provided for internal review of decisions. Under s 126, the Secretary could review a decision of an “officer” under the social security law if the Secretary was satisfied that there was sufficient reason to review the decision. It was made clear in s 126(2) that such a review could be conducted by the Secretary whether or not any person had applied for review of the decision and even if an application had been made to the AAT for review of the decision. The powers of the Secretary in conducting such a review were set out in s 126(3) and included the power to affirm a decision.

8 Separate provision was made in s 129 for a person to seek an internal review of a decision. Section 129 relevantly provided:

129 Application for review

(1) Subject to subsections (3) and (4), a person affected by a decision of an officer under the social security law may apply to the Secretary for review of the decision.

…

Neither s 129(3) nor (4) is relevant to the present proceeding. It will be necessary to return later in these reasons for judgment and discuss some additional statutory provisions which are relevant to the right of internal review under s 129.

9 There is no dispute that employees of MatchWorks were “officer[s]” for the purposes of either ss 126 or 129. Presumably this is because of the operation of s 3(2) of the Social Security (Administration) Act, which provided that “unless a contrary intention appears, an expression that is used in the 1991 Act has the same meaning, when used in this Act, as in the 1991 Act”. The reference to the “1991 Act” is a reference to the Social Security Act. “Officer” was defined in s 23 of the Social Security Act as meaning “a person performing duties, or exercising powers or functions, under or in relation to the social security law”. As noted above, the Secretary’s power to impose a suspension order under s 42AF(1)(a) was delegated under s 234(7) of the Social Security (Administration) Act to employees of the ESP in the present proceeding.

10 Perhaps a little unusually, the Social Security (Administration) Act provided for two tiers of review of certain decisions in the AAT. Under s 142 the AAT could conduct a “first review” of inter alia a decision of the Secretary or an authorised review officer (ARO) made under either s 126 or s 135 (s 135 related to a decision by an ARO in respect of an internal review application under s 129). Section 179 provided for a “second review” by the AAT from a decision of the AAT on a “first review”.

11 This broad summary of some of the relevant statutory provisions fails to convey the complexity and technicalities of the statutory regime. It will be necessary to return to those matters below in more detail after setting out some relevant factual matters.

12 In the present matter, the appellant entered into a job plan on 12 February 2019. The plan nominated his ESP as the Employment Services Group, which later changed its name to MatchWorks. In the job plan, the appellant expressly acknowledged that there was a compulsory requirement that, if he did not comply with any mutual obligation requirement, his income support payments “will be suspended” (emphasis added).

13 On 7 August 2019, MatchWorks notified the appellant by SMS text that he had an appointment with it the following day on 8 August 2019 at 3:00 pm. This produced an exchange of emails on 7 August 2019. It is not necessary to summarise all those emails but we will highlight the key relevant points.

14 The email exchange commenced with an email sent by the appellant at 11:09 am on 7 August 2019. He acknowledged receipt of the SMS text informing him of the appointment the following day. He said in his email that MatchWorks must be mistaken as he was not due for an appointment until later in the month.

15 At 11:49 am, MatchWorks responded and said that the appellant was required to attend the appointment on 8 August 2019 because he had not attended a face to face appointment for some time. He was asked to let MatchWorks know if he needed to come in at a later or earlier time (presumably still on 8 August 2019).

16 At 11:52 am, the appellant sent another email to MatchWorks in which he said that it was “wrong in every respect”. He asked that an appointment be made some time after 13 August.

17 Later, at 3:43 pm on 7 August 2019, a more senior officer at MatchWorks responded to the appellant and confirmed the appointment at 3:00 pm on 8 August 2019. The appellant was told that he “must attend”. He was also told that the appointment was “compulsory” and that failure to attend could result in his Centrelink payments being suspended.

18 It is evident from this exchange that MatchWorks never agreed to postpone the appointment and that, although the appellant requested that it do so, the appointment remained in place and he was required to attend it.

19 The appellant did not attend the scheduled appointment. Consequently, later on 8 August 2019, MatchWorks entered data on Service Australia’s computer system which recorded that the appellant had failed to attend the appointment. Service Australia’s internal records noted that the decision to suspend the appellant’s Newstart allowance from 1 August 2019 was because of the appellant “not complying with a compulsory requirement arranged by an employment service provider”. The document stated that the decision was made under s 42AL of the Social Security (Administration) Act. What is not stated in this document is whether the initial determination that the appellant had committed a mutual obligation failure was made under s 42AF(1)(a) or, alternatively, under ss 42AF(1)(b) and (2). The former provision operated where a person had committed a mutual obligation failure and consequently the person’s participation payment was not payable for the period specified in s 42AL, as opposed to the situation where s 42AF(2) applied on the back of s 42AF(1)(b) and the Secretary was satisfied that the person had persistently committed mutual obligation failures. Presumably, however, the decision was made under s 42AF(1)(a) because, as noted above, this power was delegated to MatchWorks (who made the decision), but not the other power.

20 By a letter dated 8 August 2019, the Secretary of the Department of Human Services wrote to the appellant and informed him that, because he did not attend the appointment on 8 August 2019, his Newstart allowance had been stopped from 1 August 2019. He was advised that he should call his ESP and discuss the reasons why he had not attended the appointment and to obtain advice on what he needed to do to have his Newstart allowance restarted. He was told that if he disagreed with the decision and had discussed it with his ESP he could contact Centrelink and ask for a review of the decision. He was also given information regarding review by the AAT in the event that he disagreed with the review officer’s decision.

21 MatchWorks entered additional information into Service Australia’s IT system concerning the appellant’s non-compliance. This included a document stamped 4:17 pm on 8 August 2019 which noted that the suspension of the appellant’s payments was because of his failure to attend a provider appointment. The document recorded that the appellant had not given prior notice of his inability to attend. Alongside the pro forma question as to whether “Provider accepted reason given”, the document said “No”. This internal document also recorded “non-compliance event update details” as at 12 August 2019. The updated material recorded that MatchWorks had discussed the non-compliance with the appellant on 12 August 2019 and that the appellant’s excuse for non-compliance was that the appellant believed that he did not have a requirement. Alongside the pro forma question as to whether the job seeker had given prior notice of inability to attend the appointment, the internal record said “No”.

22 At 5:03 pm on 8 August 2019, the appellant lodged with the AAT an electronic application for review of the suspension decision. In that application, the appellant said that he was “not going to go through the Centrelink [or] ARO process as Centerlink (sic) did not make the decision”. “ARO” refers to an authorised review officer.

23 It appears that shortly thereafter the appellant was told that the AAT lacked jurisdiction because it could become involved only after the internal review process was completed.

24 On 9 August 2019, the appellant contacted the Department concerning the internal review process. As will shortly emerge (see at [29] below), the appellant claimed in his originating application for judicial review that he was told that Centrelink was not able to remove the suspension and that he had to sort it out with his ESP. He says he was also told that all authorised review officers were “a virtual team”.

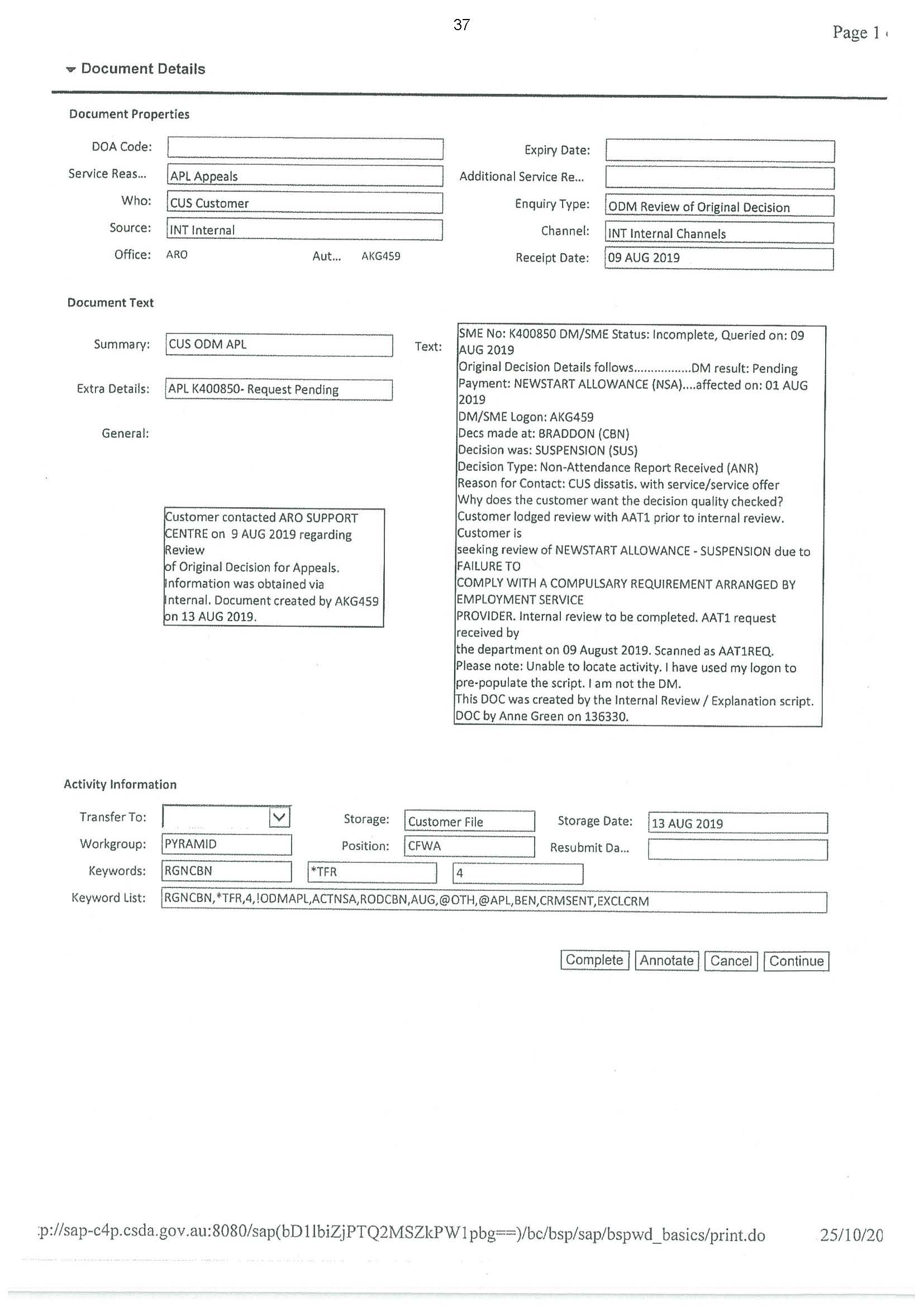

25 It appears, however, that despite these claims and apparently unbeknown to the appellant at the time, his contact with Centrelink on 9 August 2019 had the effect of initiating an internal review process. This is reflected in the following document which was created internally within Centrelink on or about 13 August 2019 (note the reference towards the end of the large box on the right hand side of the document to “Internal review to be completed” and “AAT1 request received by the Department on 9 August 2019”, which is a reference to the first tier of review in the AAT):

26 Returning to the chronology of events, by an email sent at 4:52 pm on 8 August 2019, the appellant told a senior officer at MatchWorks that he will never “SEE [the junior MatchWorks officer he was dealing with] AGAIN” and that he “WILL NOT HAVE THE POLICE CALLED ON ME AGAIN BY ANY OF YOUS (sic) STAFF”. He said that he had appealed the other officer’s decision today “with the AAT and further”.

27 A file note dated 12 August 2019, prepared by the junior MatchWorks officer with whom the appellant had been dealing, records a telephone call she received from him, apparently on that day. The note is as follows (JS presumably refers to job seeker):

JS called the office aggressively screaming “don’t you hang up on me, this is your last chance to un-suspend my payments or I’m coming to get your c**nts” JS then terminated the phone call.

28 Subsequently, on 21 August 2019, the appellant’s Newstart allowance was reinstated and he was paid in full for the suspension period. The internal document which records the restoration of the Newstart payments discloses no reason why that occurred. As will shortly emerge, however, in her reasons for decision on the internal review, the ARO said that “[o]n 12 August 2019 MatchWorks updated this failure as finalised and reconnection not required” and that the allowance was restored without any penalty. Accordingly, it appears that no reconnection requirement was imposed upon the appellant for him to have his Newstart payments restored and that it was sufficient that MatchWorks informed the Department, following its contact with the appellant on 12 August 2019, that his mutual obligation failure had been “finalised” in some other way and in spite of the appellant’s grossly offensive remarks recorded in the file note dated 12 August 2019.

Judicial review proceeding in this Court

29 On 27 August 2019, the appellant filed in the Court an originating application for judicial review, which sought review of the “conduct” of the Department of Human Services (Centrelink). In the body of the originating application, the appellant complained that he had gone to a Centrelink office at Tuggeranong after his Newstart allowance was suspended. He said that he asked to see an ARO to have the ESP’s decision reviewed. He said that he was told that Centrelink was not able to remove the suspension and that he had to sort out the issue with his ESP. When he insisted on seeing an ARO, he said that he was told to contact the Centrelink Participation Team because there were no AROs physically located in any Centrelink office and that all AROs were “a virtual team”. The appellant stated in the originating application that at no time was he given a Centrelink complaint form or offered an ARO.

30 In his originating application, the appellant complained that his experience was inconsistent with the internal review process described on Centrelink’s website. He said that it prevented him from having the Newstart suspension decision reviewed by the AAT because there had first to be a review by an ARO. He said that this situation “illustrates a broken complaint/review process that systematically blocks access to any review process to anyone wanting to have an ESP’s decision reviewed”. The evidence is unclear as to when the appellant first became aware of the fact that an internal review process had commenced on or about 13 August 2019.

31 On 27 August 2019, the appellant filed a proposed amending originating application for judicial review. This document described the subject of the amended application as Centrelink’s conduct in refusing to review any decision made by a delegate of the Department in relation to the suspension of the appellant’s Newstart allowance. It is evident from the “Details of claim” that the central object of the appellant’s concern was what he saw as Centrelink’s refusal to review MatchWorks’ decision to suspend his Newstart allowance. It may reasonably be inferred that, as at 27 August 2019, the appellant was unaware of the fact that an internal review of the suspension decision was being conducted. As noted above, however, the evidence is unclear as to when the appellant first became aware of that fact.

32 On 29 October 2019, in order to clarify the parties’ respective cases, each was ordered to file a concise statement. On 4 November 2019, the appellant served a concise statement. It appears that he never filed a copy with the Court. However, a copy of his concise statement was handed up, without objection, in the course of the appeal. At the end of that concise statement, in summarising his case, the appellant said that “he would like to know the process to have a decision of an ESP reviewed” and “the authority of the decision of the ESP to suspend my NSA”.

33 There are several points to note about the respondent’s concise statement, which was filed on 12 November 2019. The respondent stated at [4] that the appellant’s Newstart allowance had been suspended “in accordance with s 42AF(1)” and that this suspension “was a decision of the [appellant’s] Employment Services Provider” acting under delegation. Significantly, in a footnote, the respondent referred to ss 42AF(2) and (3A) and its application to persistent mutual obligation failures, but then said: “There is nothing to suggest that either subsection is relevant to these proceedings”. Accordingly, the respondent’s clear position before the primary judge was that the suspension decision was one made under s 42AF(1)(a) and was a decision made by MatchWorks. This position was supported by the relevant documentation, despite some of the limitations referred to above.

34 Later in its concise statement, the respondent said that its records “indicate that the [appellant] sought internal review, pursuant to s 129 …”. It added that the appellant could seek review of the ARO’s decision under s 135 in the AAT.

35 In its concise statement, the respondent said that the Court had no jurisdiction to entertain the appellant’s grievance as described in his concise statement. Alternatively, it claimed that his judicial review application was futile and that he had “not availed himself of his rights to merits review”. This can only be a reference to a review by the AAT. If that is so, it is difficult to understand that alternative proposition simply because, in circumstances where the ARO had not yet completed her internal review, at that time the appellant had no right to seek review by the AAT.

36 In the Court below, the appellant filed a response dated 21 November 2019 to the respondent’s concise statement (a copy of this document was included in the appeal papers). This response also pre-dates the finalisation of the ARO’s internal review. In response to the respondent’s claim that he had sought internal review of the suspension decision, the appellant said that this was incorrect because he was not able to seek an internal review by anyone in Centrelink, including an ARO. The appellant repeated his complaint that because he was unable to access an internal review, he was “prevented from accessing the AAT for any reason concerning Newstart payments”. Later in his response, the appellant acknowledged that he had “sought an internal review”, but he added that he had not actually been able to lodge any such review.

37 In the light of these matters, it appears, therefore, that the appellant first became aware of the fact that an internal review was on foot upon reading the respondent’s concise statement dated 12 November 2019. He said in his concise statement in response that he had not been contacted by the ARO about the review and that the review had been on foot apparently for more than three months and was still to be concluded. Accordingly, he claimed in his concise statement in response that there was no adequate alternative remedy which would justify dismissal of his judicial review application. As matters stood at that time, that proposition appears to be correct, but the position changed shortly thereafter when the ARO informed the appellant of the outcome of the internal review by the letter dated 26 November 2019. From that time, the appellant did have a right to seek a review of that decision in a first tier review by the AAT.

Outcome of the internal review

38 The appellant was informed of the outcome of the internal review by a letter dated 26 November 2019 (i.e. after the appellant commenced his judicial review proceedings in the Court on 27 August 2019). On the first page of the ARO’s reasons for decision, reference is made to the appellant having “requested a review because you disagree with your Newstart Allowance being suspended when you faile to meet your mutual obligations”. The appellant was told that the suspension decision was affirmed because the ARO found that he had failed to comply with the mutual obligation requirement by not attending the appointment on 8 August 2019 with his ESP. He was also advised that the ARO had found that he had not given his ESP “prior notice” that he would not be attending the appointment. The ARO noted that the Newstart allowance had been restored and that no penalty had been imposed. For completeness it might be noted that the ARO’s reasons for decision relate not only to the suspension decision dated 8 August 2019, but also to what were said by the appellant to be two earlier suspension decisions dated 17 April 2019 and 24 May 2019 for which the appellant had also apparently sought reviews.

39 In her reasons for decision, the ARO identified the law and policy which she had applied. The material referred to was not confined to material which was relevant to a decision under s 42AF(1)(a). Reference was also made to material which was relevant to a decision under s 42AF(1)(b) when combined with s 42AF(2). It is not entirely clear why the ARO regarded it as necessary to refer to that latter material. The explanation may lie in the fact that the appellant’s Newstart allowance had been cancelled twice in 2015 and 2016 respectively, which must have involved a decision under ss 42AF(1)(b) and (2). In any event, it is reasonably clear from the balance of the ARO’s reasons for decision that she treated the appellant’s internal review request relating to the decision made on 8 August 2019 as being a decision made under s 42AF(1)(a) and not under s 42AF(1)(b) in combination with s 42AF(2).

40 The ARO’s reasons record that the appellant had committed 29 mutual obligation failures in the period 22 March 2018 to 8 November 2019, which had resulted in his Newstart allowance being suspended each time that the Department was notified of those failures.

41 The ARO’s reasons also recorded that the ARO had had discussions with MatchWorks and “they have advised that due to inappropriate behaviours you have displayed in their office and towards staff during your attendances they have arranged alternate servicing arrangements for you” and that most interaction was now online. The appellant was informed of his right to request a review by the AAT.

42 The ARO’s reasons include the following statements (emphasis added):

On 8 August 2019 the department sent you a letter advising that our records showed that you did not go to, or were late for an appointment arranged by your provider on 8 August 2019. As a result, your Newstart Allowance has been stopped from 1 August 2019.

You were required to attend an appointment with Matchworks on 8 August 2019. You did not attend that appointment and you did not give Matchworks prior notice that you would not be attending.

Matchworks submitted this failure to the department reporting that you had provided an invalid reason for your non-attendance. On receipt of this notification from Matchworks regarding the non-attendance of your mutual obligation appointment your Newstart Allowance was stopped.

This letter is a notice of decision made under social security law. Information about what to do if you think this decision is wrong is on the back of the letter.

…

On 12 August 2019 Matchworks updated this failure as finalised and reconnection not required.

Your Newstart Allowance was restored and no penalty was applied for failing to meet your mutual obligation.

…

43 The emphasised sentence confirms that no reconnection requirement was imposed on the appellant under s 42AM. This provides further support for the view expressed above that the ARO viewed her task as conducting an internal review of a decision made under s 42AF(1)(a) and not one under s 42AF(1)(b) in combination with s 42AF(2).

44 Finally, as indicated above, it appears that the appellant was unaware of the internal review prior to 12 November 2019 when he was served a copy of the respondent’s concise statement in the proceeding below. The ARO’s reasons record, however, that she attempted to telephone the appellant on both 21 and 25 November 2019 to discuss the review but she was unable to contact him.

Summary of primary reasons for judgment

45 The parties each filed written submissions and agreed to have the matter determined on the papers. As the primary judge noted at [2], however, there was a short oral hearing conducted on 30 September 2020. This was intended to permit the appellant to explain what he sought to achieve by the proceedings, given that the respondent had contended that the proceeding lacked any utility and that relief should be refused on this ground. Her Honour noted at [2], that at the hearing on 30 September 2020, the appellant made “brief oral submissions consistent with his written submissions”.

46 After noting that the appellant had filed three affidavits in the proceedings (two of which were described by the primary judge as being in the nature of submissions only), the primary judge described the background to the proceeding. Her Honour gave brief reasons for dismissing the amended originating application.

47 In the course of summarising some relevant aspects of the statutory regime, the primary judge made specific reference to s 42AF(1)(a) of the Social Security (Administration) Act which, when read in context, strongly suggests that her Honour proceeded on the basis that the decision to suspend the appellant’s Newstart allowance was made under that provision (and not under s 42AF(1)(b) and (2)).

48 At [11], the primary judge found that, on 9 August 2019, the appellant had “sought internal review pursuant to s 129 of the Administration Act” of the suspension decision and that he contacted his ESP on 12 August 2019. Her Honour then added that, as a result, the appellant’s Newstart payments were reinstated on 20 August 2019 and he was repaid in full the amounts withheld from him during the suspension period.

49 Her Honour noted at [12] that, on 26 November 2019, the ARO had affirmed the 8 August 2019 suspension decision. Her Honour said that the ARO had found that the appellant had failed to comply with a mutual obligation requirement by not attending the appointment with MatchWorks and “had not given MatchWorks prior notice that he would not be attending”. Her Honour added that the ARO had noted that the Newstart allowance had been restored and no penalty was imposed.

50 The primary judge said at [16] that the precise nature of the appellant’s legal grievances were “unclear”. Her Honour added that it appeared that the complaint related to “the scheme for merits review established by the Administration Act”.

51 With specific reference to the appellant’s complaint that the review officer did not undertake a merits review of the ESP’s decision and merely confirmed that the Newstart allowance had been restored, the primary judge stated at [17] that the “fundamental difficulty” with this submission is that the appellant had been successful in his internal review application in having the suspension brought to an end and his payments restored without penalty. Accordingly, her Honour added that there was nothing further which the appellant could achieve on a merits review. As will shortly emerge, these findings are the subject of ground 3 of the notice of appeal.

52 At [18], the primary judge added that the proceedings lacked any utility in circumstances where the suspension had ended and Newstart payments had been restored without penalty. This finding is the subject of ground 5 of the notice of appeal.

53 The primary judge then noted at [19] that, even if there had been a live issue between the parties, relief would have been refused in any event under s 10(2)(b)(ii) of the ADJR Act because of the availability of an adequate and alternative review mechanism in the AAT. This finding is the subject of ground 4 of the notice of appeal.

54 Finally, because the respondent had been wholly successful, the primary judge ordered the appellant to pay the respondent’s costs. This costs order is the subject of grounds 7 and 8 of the notice of appeal.

The grounds of appeal and their resolution

55 It is convenient to set out the eight grounds of appeal and explain why each should be rejected. Before doing so, it is necessary to enter the thicket of the relevant statutory regime.

(a) The statutory provisions

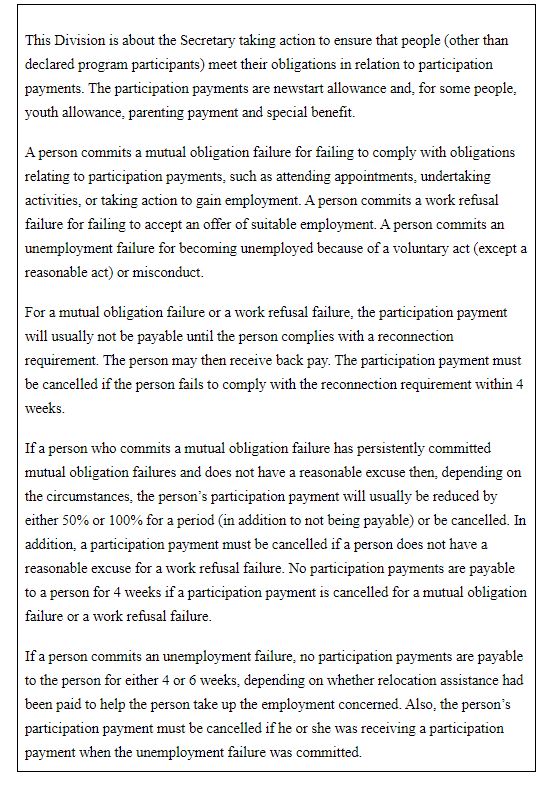

56 The statutory provisions relating to this proceeding are notably complex. Before descending into the thicket, it is appropriate to set out in full the simplified outline of Div 3AA of Pt 3 of the Social Security (Administration) Act, which related to compliance with participation payment obligations (this Division contained many of the statutory provisions relevant to the present proceeding):

42AA Simplified outline of this Division

57 It is desirable to set out the relevant parts of ss 42AC, 47AF(1) and (2), 42AI, 42AJ, 42AL and 42AM(1) and (2).

58 Section 42AC provided:

42AC Mutual obligation failures

(1) A person commits a mutual obligation failure if the person is receiving a participation payment and any of the following applies:

…

(c) the person fails to attend, or to be punctual for, an appointment that the person is required to attend by:

(i) …; or

(ii) an employment pathway plan that is in force in relation to the person;

…

(Emphasis in original.)

59 As noted above, there was an employment pathway plan in the form of a job plan in relation to the appellant.

60 Section 42AF provided:

42AF Compliance action for mutual obligation failures

Usual rule

(1) If a person commits a mutual obligation failure (the relevant failure), the Secretary must:

(a) determine that the person’s participation payment is not payable to the person for a period (see section 42AL); and

(b) take action under subsection (2) (if applicable).

Note: The person may be eligible for back pay once the payment suspension period ends (see subsection 42AL(4)).

Special rule—persistent mutual obligation failures and no reasonable excuse

(2) If:

(a) the Secretary is satisfied in accordance with an instrument made under subsection 42AR(1) that the person has persistently committed mutual obligation failures; and

(b) the person does not satisfy the Secretary that the person has a reasonable excuse for the relevant failure (see sections 42AI and 42AJ);

the Secretary must, in accordance with that instrument, determine:

(c) that an instalment of the person’s participation payment for an instalment period is to be reduced (see section 42AN), in addition to making a determination under paragraph (1)(a) of this section; or

(d) that the person’s participation payment is cancelled (see section 42AP).

Note 1: For paragraph (c), the person may be eligible for back pay once the person’s payment suspension period ends (see subsection 42AL(4)). However, the back pay may be reduced (including to nil) if the instalment period for which an instalment is to be reduced under paragraph (c) overlaps with the payment suspension period.

Note 2: For paragraph (d), a further consequence is that participation payments will not be payable to the person for the person’s post‑cancellation non‑payment period (see subsection 42AP(5)).

61 As noted above, sub-section 42AF(2) only applied in circumstances where the Secretary was satisfied that the person had “persistently committed mutual obligation failures” and the person did not satisfy the Secretary that the person had a reasonable excuse for the relevant failure. This draws attention to ss 42AI and 42AJ. Where the conditions to the exercise of the power in s 42AF(2) did not apply and s 42AF(1)(a) applied, the end of the payment suspension period was determined by s 42AL(3). Sub-section 42AL(3) contemplated that the period may end either because the person had complied with a reconnection requirement or the Secretary had determined under s 42AL(3)(b) that an earlier day was more appropriate.

62 Section 42AI provided:

42AI Reasonable excuses—matters that must or must not be taken into account

Matters to be taken into account

(1) The Secretary must, by legislative instrument, determine matters that the Secretary must take into account in deciding whether a person has a reasonable excuse for committing:

(a) a mutual obligation failure (see paragraph 42AF(2)(b)); or

(b) a work refusal failure (see subsection 42AG(2)).

(2) To avoid doubt, a determination under subsection (1) does not limit the matters that the Secretary may take into account in deciding whether the person has a reasonable excuse.

Matters not to be taken into account

(3) The Secretary may, by legislative instrument, determine matters that the Secretary must not take into account in deciding whether a person has a reasonable excuse for committing:

(a) a mutual obligation failure (see paragraph 42AF(2)(b)); or

(b) a work refusal failure (see subsection 42AG(2)).

63 This provision was only engaged where the “special rule” in s 42AF(2) applied.

64 Section 42AJ provided:

42AJ Reasonable excuses for mutual obligation failures—prior notification required for certain failures

(1) For the purposes of paragraph 42AF(2)(b), an excuse cannot be a reasonable excuse for a mutual obligation failure mentioned in subsection (2) of this section that is committed by a person unless:

(a) the person notifies the excuse as mentioned in subsection (3) of this section; or

(b) the Secretary is satisfied that there were circumstances in which it was not reasonable to expect the person to give the notification.

Note: The Secretary may also decide for other reasons that the excuse is not a reasonable excuse.

(2) The failures are as follows:

(a) a failure to comply with a requirement that was notified to the person under subsection 63(2) to attend an office of the Department, to contact the Department, or to attend a particular place;

(b) without limiting paragraph (a), a failure to attend, or to be punctual for, an appointment that the person is required to attend by a notice under subsection 63(2);

(c) a failure to attend, to be punctual for, or to participate in, an activity that the person is required to undertake by an employment pathway plan that is in force in relation to the person;

(d) a failure to attend, or to be punctual for, an appointment that the person is required to attend by an employment pathway plan that is in force in relation to the person.

(3) The person must notify the excuse:

(a) for a failure mentioned in paragraph (2)(a) or (b):

(i) before the end of the time specified under subsection 63(2); and

(ii) to the person or body specified by the Secretary as the person or body to whom prior notice should be given if the person is unable to comply with the notice under subsection 63(2); and

(b) for a failure mentioned in paragraph (2)(c) or (d):

(i) before the start of the activity on the day concerned, or before the time of the appointment; and

(ii) to the person or body specified in the employment pathway plan as the person or body to whom prior notice should be given if the person is unable to undertake the activity or attend the appointment.

As with s 42AI, this provision only applied where the “special rule” was engaged.

65 Section 42AL provided:

42AL Payment suspension periods for mutual obligation failures and work refusal failures

(1) If the Secretary determines under section 42AF or 42AG that a participation payment is not payable to a person for a period, the participation payment is not payable for the period (the payment suspension period) worked out under this section.

(2) The payment suspension period begins at the start of:

(a) the instalment period in which the person commits the mutual obligation failure or the work refusal failure (unless paragraph (b) applies); or

(b) if the Secretary determines that a later instalment period is more appropriate—that later instalment period.

(3) The payment suspension period ends immediately before:

(a) the day the person complies with the reconnection requirement imposed under subsection 42AM(1) (unless paragraph (b) of this subsection applies); or

(b) if the Secretary determines that an earlier day is more appropriate—that earlier day.

(4) If the payment suspension period ends under subsection (3) for a person, then, for the purposes of the social security law after the end of that period:

(a) the participation payment is taken to be payable to the person from the start of that period (subject to the social security law); and

(b) the Secretary is taken to have made a determination to the effect mentioned in paragraph (a).

Note: The effect of this subsection is that the person may receive back pay for the payment suspension period. However, the back pay may be reduced (including to nil) if the instalment period for which an instalment is to be reduced under section 42AN overlaps with the payment suspension period.

This provision determined the length of the payment suspension period where the Secretary has determined inter alia that a participation payment was not payable under s 42AF. Sub-section 42AL(3) determined when the payment suspension period ended. A distinction was drawn there between the situation where a person complied with a reconnection requirement imposed under s 42AM(1) and where the Secretary determined under s 42AL(3)(b) that an earlier day was more appropriate. The Secretary’s power to make a determination under s 42AL(3)(b) was another power which was delegated to ESPs in item 2 of the Delegation referred to at [5] above.

66 It is presumably this power which was exercised by MatchWorks in determining that the suspension period in respect of the appellant should end notwithstanding that no reconnection requirement had been imposed under s 42AM(1).

67 Section 42AM relevantly provided (emphasis in original and denotes a defined expression):

42AM Reconnection requirements for mutual obligation failures and work refusal failures

(1) The Secretary must impose a requirement (the reconnection requirement) on a person if the Secretary determines under section 42AF or 42AG that a participation payment is not payable to the person for a period.

(2) The Secretary must notify the person, in any way the Secretary considers appropriate, of:

(a) the reconnection requirement; and

(b) the effect of not complying with the reconnection requirement.

(3) The Secretary must determine that the person’s participation payment is cancelled if:

(a) the Secretary does not determine an earlier day for the purposes of ending the person’s payment suspension period under paragraph 42AL(3)(b); and

(b) the person fails to comply with the reconnection requirement within 4 weeks after it is notified under subsection (2) of this section.

…

68 It is appropriate to make several observations regarding s 42AM. The first thing to note is that it imposed an obligation on the Secretary to impose a requirement on a person if the Secretary made a determination under inter alia s 42AF that a participation payment was not payable to the person for a period. This was referred to as the “reconnection requirement”.

69 Secondly, s 42AM(2) imposed an obligation on the Secretary to notify the person of the reconnection requirement and the effect of non-compliance with it.

70 Thirdly, as noted above, the Secretary’s powers and functions under s 42AM(1) and (2) were delegated to ESPs under the same Delegation as that referred to at [5] above.

71 Fourthly, as noted above in respect of s 42AL(3)(a), failure to comply with a reconnection requirement was not the only way in which a suspension period came to an end. It may also have come to an end as a consequence of a determination made under s 42AL(3)(b). In accordance with orthodox principles of statutory construction, ss 42AL and 42M must be read harmoniously. When read together, and noting the absence of any explicit time period within which the Secretary (or delegate) must impose a reconnection requirement under s 42AM(1), that obligation could be displaced by action being taken under s 42AL(3)(b) by the Secretary (or delegate). That is what occurred here.

(b) The grounds of appeal

Ground 1

The finding of the Court at paragraph 12, that the appellant did not give MatchWorks prior notice for not attending an appointment was not open to the Court as there being no evidence to support the finding. The requirement to give notice in this regard forms the basis of the administrative process in dispute between the parties.

72 This ground cannot succeed. That is simply because the primary judge did not herself make the finding at [12] of the primary reasons for judgment about which the appellant complains. Her Honour did not find that the appellant had failed to give MatchWorks prior notice for not attending the appointment. Rather, her Honour simply described the ARO’s finding to that effect.

Ground 2

The finding of the Court at paragraph 7, that emails between the appellant and the respondent were subsequent and not prior to, was not open to the Court as there being no evidence to support the finding.

73 In his written outline of submissions, the appellant describes his complaint as relating to the primary judge’s mischaracterisation of the email correspondence between him and MatchWorks as “a confirmation of the appointment”. He highlights the fact that he asked MatchWorks to reschedule the appointment, which he contends is directly contradictory to the finding that no “prior notice” had been provided by him.

74 This ground must also be rejected for similar reasons for rejecting ground 1. The primary judge’s reference to “no prior notice” does not involve a finding of fact by the Court, but merely describes what the ARO had found.

75 It is evident from the appellant’s written reply that he ties this particular complaint to his contention that ss 42I and 42AJ applied to his circumstances. That submission cannot be accepted. As noted above, the source of the decision suspending the appellant’s Newstart allowance was s 42AF(1)(a) of the Social Security (Administration) Act. Sections 42AI and 42AJ dealt with circumstances where there is a “reasonable excuse” but only where an adverse decision has been made under ss 42AF(1)(b) and (2), which dealt with “persistent mutual obligation failures”. Although the appellant had been involved in what might fairly be described as persistent mutual obligation failures, as recorded in the ARO’s reasons for decision, the decision to suspend his Newstart allowance was not made under s 42AF(1)(b) and (2), but rather under s 42AF(1)(a). That provision is not subject to the requirements of ss 42AI and 42AJ. That is not to say, however, that prior notice and reasonable excuse are irrelevant considerations for the purpose of that provision, as opposed to being mandatory relevant considerations for the purposes of the combined operation of ss 42AF(1)(b) and (2).

Ground 3

The finding of the Court at paragraph 17, that the appellant’s benefit was restored due to the applicant being successful in an internal merits review process, was not open to the Court as there being no evidence to support the finding.

76 It may be accepted that the primary judge’s reference at [17] to the appellant having been successful in his internal review application was in error. The true position was that, putting to one side whether or not the appellant actually applied for an internal review, the internal review which was conducted and ended on 26 November 2019 did not result in the suspension being brought to an end and payments being restored without penalty. Those events certainly occurred but not as a result of the internal review. Rather, they occurred because of the contact the appellant made with MatchWorks on 12 August 2019 and the consequential “finalisation” of the matter.

77 We are not satisfied, however, that this error is material. What caused the suspension to end and the appellant’s Newstart allowances to be restored is not to the point. The critical point is that the occurrence of those events triggered the internal review provisions and, in turn, the AAT review provisions. The real issues are whether the judicial review proceedings had any utility in the light of these matters and/or whether there was an adequate alternative remedy. The primary judge was correct to resolve those matters as she did. They would have been resolved the same way even if the primary judge had correctly identified the source of the power under which the suspension ended and the allowance was restored.

78 It is well established that, for the purposes of the discretion under s 10(2)(b)(ii), the availability of a full merits review on a de novo basis can constitute “adequate provision” for review and entitle the Court to refuse relief in its discretion (see, for example, Bragg v Secretary, Department of Employment, Education and Training (1995) 59 FCR 31 at 34 per Davies J; McGowan v Migration Agents Registration Authority (2003) 129 FCR 118; [2003] FCA 482 at [49] per Branson J; Dauguet v Centrelink [2015] FCA 395 at [160] per Mortimer J and Rizkallah v Tax Practitioners Board (2020) 169 ALD 295; [2020] FCA 431 at [5]-[7] per Griffiths J). The position is perhaps even stronger here where the appellant potentially had available to him two tiers of review in the AAT. There can be no doubt that his complaint of procedural unfairness could have been cured if he had availed himself of those rights of review.

Ground 4

The finding of the Court at paragraph 19, that the avenues of review available to the appellant constitute adequate provision for review, was not open to the Court as there being no evidence to support the finding.

79 This ground should also be rejected. As emphasised above, it is true that prior to the finalisation of the internal review process on 26 November 2019, the appellant could not avail himself of rights of review in the AAT. That was the position when he filed his concise statement in response on 21 November 2019. But the appellant was well aware by on or about 26 November 2019 that he could seek review in the AAT of the ARO’s internal review decision. He elected not to do so and persisted with his judicial review application.

80 It was well open to the primary judge to conclude as she did at [19] that the judicial review proceeding should be dismissed in the Court’s discretion because of the availability of an alternative review mechanism in the form of the two tiers of review in the AAT. The appellant has failed to establish any error in the exercise of that judicial discretion, as required in accordance with the well-established principles in House v The King (1936) 55 CLR 499; [1936] HCA 40 at 504-5 (House).

Ground 5

The Court incorrectly applied a legal principle at paragraph 18, in finding that the parties had resolved any live issues.

81 As the respondent pointed out, the burden of this ground is not easily understood. In his reply submissions in the appeal, the appellant said that the “lack of an avenue of review is separate to the statutory “reconnection requirement””. He added that the reconnection requirement did not form part of any statutory review process and he submitted that there was no merits review avenue available to him, hence the issues remained alive.

82 The appellant’s reply submissions do not clarify the true gravamen of this ground of appeal. It is difficult to see any issues which were properly amenable to judicial review which remained live once the appellant had had his Newstart allowance restored and repaid in full, without any penalty.

83 If the burden of the appellant’s contention that live issues remained related to the issues raised by him in his concise statement to know the process to have a decision of an ESP review and the source of MatchWorks’ decision to suspend his Newstart allowance, there are real doubts whether the Court had jurisdiction to address those matters. That is because, as is well known, the Court’s jurisdiction under that legislation relates either to a decision of an administrative character made under an enactment (see s 5 of the ADJR Act) or conduct preceding the making of such a decision (s 6). The Court’s jurisdiction under the ADJR Act did not extend to providing the advice which the appellant sought as described in his concise statement. And the “conduct” identified in his amended originating application was overtaken by the ARO’s decision dated 26 November 2019. It is notable that, in his amended originating application, the appellant did not explicitly raise any legal question as to the source of the power underpinning the 8 August 2019 suspension decision.

84 It is desirable to now say something regarding the appellant’s complaint of procedural unfairness notwithstanding that this complaint is not included in the grounds set out in his notice of appeal. It appears that the complaint is primarily directed to the conduct of the internal review. Although the appellant submitted in oral address that the internal review was conducted under s 126 of the Social Security (Administration) Act, the better view is it was conducted under s 129, i.e. where a person affected by a decision of an officer under the social security law applies to the Secretary for review of the decision. Sub-section 129(1) does not require any such application to be made in writing. The appellant claims that he asked for an internal review on 8 August 2019 and although he believed that his request had been rebuffed, an internal review was in fact initiated shortly thereafter. The document set out at [25] above confirms that the internal review was initiated following Mr Ambrose’s request for a review.

85 Division 2 of Pt 4 dealt with internal review of decisions, however, little guidance was provided regarding the procedures applicable to such a review. Section 135 obliged the person conducting the internal review to “review” the decision and such a person was required to affirm or vary the decision or set it aside and substitute a new decision. The respondent submitted that the legislation did not disclose a plain intention to exclude procedural fairness requirements. That submission should be accepted. What is uncertain, however, is the content of procedural fairness requirements. It is unnecessary to determine that question in this appeal. That is for two reasons. The first is that while it is evident that the appellant played no active role in the conduct of the internal review, there was no reason to doubt the correctness of the ARO’s statement in her reasons for decision that she tried unsuccessfully twice to contact the appellant before finalising the internal review. From the bar table, the appellant said that it was his practice not to answer any telephone calls he received from a private number. He said that the ARO should have contacted him by email. In our view, it was reasonably open to the review officer to try to contact the appellant by telephone in circumstances where it may be inferred that the appellant provided the Department with that detail.

86 Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, even if what occurred involved procedural unfairness, that unfairness was capable of being cured by the full merits review in the AAT, which remedy was not pursued by the appellant (see, for example, Twist v Randwick Municipal Council (1976) 136 CLR 106 and Hill v Green (1999) 48 NSWLR 161; [1999] NSWCA 477).

87 For completeness, it may also be observed that it appears that the statutory regime does not contemplate procedural fairness requirements applying to the original decision to suspend Newstart allowances under s 42AF(1)(a). It is notable that that provision imposes a statutory obligation on the Secretary to determine that a participation payment is not payable to a person who has committed a mutual obligation failure. The mandatory nature of that obligation is reflected in the statement made by the appellant in his job plan that he recognised that his allowance “will” be suspended if he committed a mutual obligation failure (see at [12] above).

Ground 6

The appellant made submissions early in the proceedings that were not in affidavit form and were not considered by the Court as material that the appellant sought to rely upon. Further to this, the respondent failed to maintain a court book for the proceedings as directed by the Judge in the first case management hearing.

88 The appellant clarified in his reply submissions that this ground of appeal is directed to his complaint that neither the respondent nor the primary judge adequately addressed his claims regarding the respondent’s alleged refusal to accept his initial request for internal review on 8 August 2019. The difficulty for him, however, is that notwithstanding what he may have believed at the time, an internal review under s 129 was in fact commenced shortly thereafter and it culminated with the determination by the ARO on 26 November 2019. It can hardly be disputed that the 15 weeks it took for the ARO to complete the internal review seems very long, but it must be borne in mind that the review covered three different suspension decisions and was not confined to the suspension decision dated 8 August 2019. The ARO’s reasons for decision also made clear that the opportunity was taken by the ARO to undertake what she described as “a holistic review of [the appellant’s] Newstart allowance to address [the three alleged] failures and ensure no outstanding issues remain and a detailed explanation is provided to you”. The reasons for decision addressed additional matters beyond the 8 August 2019 suspension, including the fact that the appellant’s full time study at the University of New England was not an approved “work for the dole” activity.

Ground 7

The finding of the Court at paragraph 20, that the respondent has been wholly successful in defending the application, was not open to the Court as there being no evidence to support the finding.

89 It is convenient to address this ground and ground 8 together because they both relate to the primary judge’s order that the appellant pay the respondent’s costs. As that decision involved the exercise of a judicial discretion, the appellant needed to establish an error of the kind identified in House. No such error has been established.

90 In his reply submissions, the appellant contended that the respondent had only revealed its position in its outline of written submissions dated 29 April 2021 in the appeal. We do not except that the respondent’s position emerged so belatedly. Its position regarding the futility of the proceeding and the issue of the Court’s jurisdiction were made abundantly clear in its concise statement below filed on 12 November 2019. As emphasised above, the appellant elected to persist with his judicial review challenge despite the contents of that concise statement and the clear significance of the internal review decision dated 26 November 2019. That was his choice. He was well aware that there was a risk that he might be ordered to pay the respondent’s costs of the proceeding below. This was made clear to him at an early case management hearing.

Ground 8

The appellant was given no other avenue other than an application for review of the appellant’s complaint regarding the merits review process in the Federal Court and the appellant should not incur any costs apart from the appellant’s own costs in seeking redress in this form.

91 See [89]-[90] above.

Conclusion

92 For these reasons, the appeal should be dismissed, with costs.

I certify that the preceding ninety-two (92) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Collier, Griffiths and Abraham. |