Federal Court of Australia

Connor v State of Queensland (Department of Education and Training) [2021] FCAFC 21

ORDERS

BEAU CONNOR (BY HIS LITIGATION REPRESENTATIVE, PETER CONNOR) Appellant | ||

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND (DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING) Respondent | |

reeves, perry and snaden JJ | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appellant’s interlocutory application of 13 November 2020 be dismissed.

2. The appeal be dismissed.

3. The appellant pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal, to be assessed in default of agreement in accordance with the court’s Costs Practice Note (GPN-COSTS).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

1 The appellant, Beau Connor (hereafter, “Beau”), is a former pupil of Kawungan State School (hereafter, the “School”), which is located in Hervey Bay, Queensland. Throughout the period of his enrolment at the School, he suffered from Autism Spectrum Disorder, Pervasive Development Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and other conditions. He claims that the respondent, the State of Queensland (which administers the School), discriminated against him in connection with his enrolment at the School; and that it did so contrary to the requirements of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) (hereafter, the “DD Act”).

2 Beau’s claims—which are brought with the assistance of his litigation representative and father, Peter Connor (hereafter, “Connor”)—revolve around various instances of detrimental treatment to which he says that the School subjected him throughout the course of his enrolment. His claims were the subject of a nine-day hearing before the primary judge in October 2019. His Honour dismissed them with costs: Connor v State of Queensland (Department of Education and Training) (No 3) [2020] FCA 455 (Rangiah J; hereafter, the “Primary Judgment”). By the present appeal, Beau contends that that judgment was the product of error, which this court should correct on appeal.

3 For the reasons that follow, we are unable to agree. The Primary Judgment discloses no appellable error and the appeal will be dismissed with the usual order as to costs.

Background

4 By the proceeding below, Beau pursued three broad species of complaint, described in his pleading as “the First Allegation”, “the Second Allegation” and “the Third Allegation”.

5 By the First Allegation, Beau claimed to have been unlawfully discriminated against insofar as he had been suspended from the School on multiple occasions between February 2011 and August 2015. The primary judge fairly described that headline allegation as follows (Primary Judgment, [18]-[19]):

The First Allegation is that Beau was suspended from the School on multiple occasions during the period from February 2011 to August 2015. These are described as “formal suspensions” and “informal suspensions”. The “informal suspensions” involved Beau’s parents being called to take him home from the School during normal teaching hours. The informal suspensions are alleged to have occurred on ten occasions. There are alleged to have been eleven formal suspensions totalling 88 days.

It is alleged that by suspending him, the State treated Beau less favourably than it would treat a student without disabilities, or without Beau’s disabilities, attending a government school. The formal and informal suspensions are alleged to have been imposed directly due to Beau’s disabilities. It is further alleged that the State failed to provide Beau with supports that students in government schools can receive, such as a formal social skills program, language and sensory programs, engaging an external expert to address Beau’s behaviours of concern and a comprehensive Individual Education Plan.

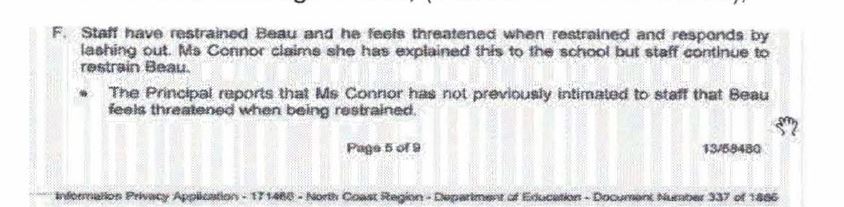

6 By the Second Allegation, Beau claimed to have been unlawfully discriminated against by having been subjected to various instances of physical restraint, and seclusion or isolation from his classmates. The primary judge fairly described the allegation as follows (Primary Judgment, [20]):

The Second Allegation is that Beau was subjected to physical restraint/violence and seclusion/isolation at the School on the basis of his disability. This is alleged to have occurred on at least 25 occasions. It is alleged that this treatment was directly due to Beau’s disabilities and was also inconsistent with the School’s policies, procedures and guidelines for the treatment of students. It is alleged that the State treated Beau less favourably than it would treat a student without disabilities, or without Beau’s disabilities, attending a government school.

7 By the Third Allegation, Beau charged the respondent with having failed to provide him with a “Functional Behaviour Assessment” or a “Behaviour Plan”. The primary judge properly described that allegation as follows (Primary Judgment, [21]):

…It is alleged that a Functional Behaviour Assessment was required to determine the function of Beau’s behaviours of concern to mitigate or extinguish those behaviours. It is alleged that the Behaviour Plans that were developed by the School were inadequate and punitive. It is alleged that the failure to provide a formal Functional Behaviour Assessment and Behaviour Plan had the effect that Beau was, because of his disabilities, treated less favourably than a student without his disabilities would have been.

8 It was not controversial that Beau was, at material times, relevantly afflicted by a disability or disabilities. At issue was whether (or the extent to which) Beau had been subjected to the treatment of which he complained; and, if he had been, whether that treatment had been visited upon him by reason of his disabilities.

9 In his thorough reasons for judgment, the primary judge made findings about the various ways that Beau claimed to have been treated. For present purposes, it is not necessary to recite all of those findings. It suffices to note that his Honour largely (though not entirely) accepted that Beau had been suspended, restrained and isolated in the various ways that he had alleged (Primary Judgment, [232]-[234], [278]-[281]). What his Honour did not accept was that that treatment (or any individual instance of it) amounted to unlawful discrimination contrary to the DD Act. His Honour concluded that none of the treatment to which Beau had been subjected had been visited upon him by reason of his disabilities. Rather, his Honour concluded (Primary Judgment, [256], [289], [295]) that, on each occasion, Beau had been treated in the way that he was in order to address disruptive or violent behaviour on his part, or because he had otherwise been distressed; and that, on each occasion, his treatment was no different to how the School would have treated any student who had exhibited the same behaviours, whether afflicted by the same disabilities or not.

10 His Honour also addressed Beau’s claim that the School (or the respondent, via the agency of the School) had failed to provide him with a “Functional Behaviour Assessment” or a “Behaviour Plan”. Those instruments were said to qualify as “reasonable adjustments” for the purposes of the DD Act; and it was alleged that the School’s (or the respondent’s) failure to provide them had the effect of subjecting Beau to treatment that was less favourable than that to which a student without his disabilities would have been subjected. His Honour rejected the assertion both at a factual level and at the level of principle (Primary Judgment, [334]-[335]). He concluded that a “2013 Class Behaviour Management Plan” and two “Individual Behaviour Support Plans” that were adopted by the School were sufficient to qualify as “Functional Behaviour Assessment[s]” (as defined by Beau’s statement of claim). Even assuming otherwise, his Honour concluded (Primary Judgment, [336]-[337]) that Beau could not establish that he had been treated less favourably on account of his disabilities than he would have been had those measures (that is, the adoption of a “Functional Behaviour Assessment” or a “Behaviour Plan”) been properly implemented.

The statutory framework

11 Section 22(2) of the DD Act relevantly provides (and at relevant times, provided) as follows:

22 Education

…

(2) It is unlawful for an educational authority to discriminate against a student on the ground of the student’s disability:

(a) by denying the student access, or limiting the student’s access, to any benefit provided by the educational authority; or

(b) by expelling the student; or

(c) by subjecting the student to any other detriment.

…

12 It was not in contest—and, in any event, is plain—that the respondent qualifies as an “educational authority”: DD Act, s 4(1).

13 Sections 5 and 6 of the DD Act define what is meant by “discriminate” in s 22(2): DD Act, s 4(1). Section 5 of the DD Act—which is relevant for present purposes—provides as follows:

5 Direct disability discrimination

(1) For the purposes of this Act, a person (the discriminator) discriminates against another person (the aggrieved person) on the ground of a disability of the aggrieved person if, because of the disability, the discriminator treats, or proposes to treat, the aggrieved person less favourably than the discriminator would treat a person without the disability in circumstances that are not materially different.

(2) For the purposes of this Act, a person (the discriminator) also discriminates against another person (the aggrieved person) on the ground of a disability of the aggrieved person if:

(a) the discriminator does not make, or proposes not to make, reasonable adjustments for the person; and

(b) the failure to make the reasonable adjustments has, or would have, the effect that the aggrieved person is, because of the disability, treated less favourably than a person without the disability would be treated in circumstances that are not materially different.

(3) For the purposes of this section, circumstances are not materially different because of the fact that, because of the disability, the aggrieved person requires adjustments.

14 “[D]isability” is defined (DD Act, s 4(1)) so as to include:

(1) the total or partial loss of a person’s mental functions; and

(2) a disorder, illness or disease that affects a person’s thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgment, or that results in disturbed behaviour.

The respondent accepted before the primary judge—and still accepts—that Beau was afflicted by relevant disabilities throughout the period of his enrolment at the School.

15 “[R]easonable adjustment” is defined as an adjustment that would not impose an unjustifiable hardship upon the person required to make it: DD Act, s 4(1). “[U]njustifiable hardship” is separately defined in terms that needn’t be set out here: DD Act, s 11.

16 Section 10 of the DD Act provides as follows:

10 Act done because of disability and for other reason

If:

(a) an act is done for 2 or more reasons; and

(b) one of the reasons is the disability of a person (whether or not it is the dominant or a substantial reason for doing the act);

then, for the purposes of this Act, the act is taken to be done for that reason.

The appeal

17 By his notice of appeal, Beau listed 18 discrete grounds by which he charged the primary judge with error. Intending no disrespect (and acknowledging the courtesy and aptitude with which Connor prosecuted Beau’s appeal), many of the grounds that he sought to agitate were difficult to comprehend; and many of those difficulties remained after—and, indeed, some were amplified by—the written and oral submissions that were advanced. Those realities acknowledged, it is convenient to replicate in full the grounds that found expression in Beau’s notice of appeal (errors, formatting and emphasis original):

Grounds of appeal;

1. Abuse of process, Misuse or unjust use of court procedure.

2. Breach of Natural Justice.

3. Abuses/Breach's of Procedural fairness.

A. Judge accepted Documents (applicant was not privy to) after Judge had adjourned on the last day,

B. Judge had accepted a USB (applicant was not privy to).

4. Justice Rangiah has applied an incorrect principle of law; (multiple times).

5. Justice Rangiah has made a finding of fact or facts on important issues which could not be supported by the evidence.

6. Restraint;

Justice Rangiah has ERRED in his findings of fact, (extracts from the evidence),

a. He has ignored evidence that "The Connors" did not consent to "Restraint" of Beau.

Extract from complaint to Dept. 15th Feb 2013. Conflicts with the Judgement.

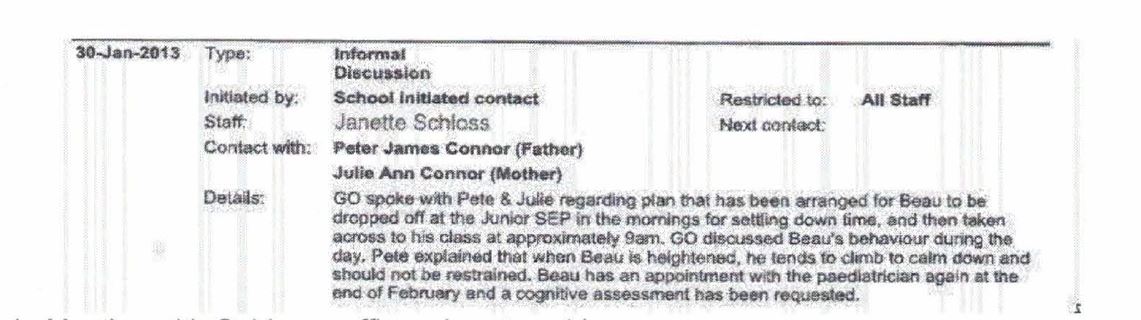

b. Meeting with Guidance officer, Janette schloss.

Judge has ERRED in accepting that Beau was only subjected to restraint "As a last resort" but as evidenced, as many people (cleaners, groundsmen, and admin staff) who weren't privy to Beau's plans, restrained Bea. Beau was also Restrained whilst in the Jail cell, which was after being put in there, despite being the second last item on the plan before calling his parent(s).

The state has a greater responsibility within their institutions to follow the law, and their international agreements

A Unilateral mistake was made, as full disclosure was not made to the connor’s, being Non est factum at law. The evidence supports the Connor’s claims not the respondents.

7. Disability/ Respondents defence;

Justice Rangiah accepted the State Admits the Applicant has a disability when the State denied this, and provided no amended defence. A mistake at law.

What appears not, does not exist, and nothing appears judicially before judgement.

Error in procedendo - procedural error (in court) Error on a point of law or procedure (vs. error in iudicando)

8. False Testimony / Perjury;

Justice Rangiah has accepted, False testimony (Perjury) and altered documents (Fraud), he has ignored aspects of the evidence presented to him, being a mistake at law, resulting in him applying an incorrect principle of law. The state has hidden documents and facts, which were bought to the Judges attention. Page numbers Vary 128 to 77. Ignoring the fact that on the balance of probabilities, the state's witnesses have colluded to pervert the course of justice.

No original documents were handed up to the court, with wet ink signatures on them to verify their authenticity.

"A concealed fault is equal to a deceit. It is a fraud to conceal a fraud.

Gross negligence is equivalent to fraud- Culpa lata - gross negligence,

Deceit is an artifice since it pretends one thing and does another.

This is a Breach of procedural process and contempt."

Justice Rangiah has made a finding of fact or facts on important issues which could not be supported by, or conflict with the evidence.

9. Respondent evidence;

Justice Rangiah overlooked the fact Boss-walker stated he was only employed at KSS from 2014, he authored documents in 2012 and 13. They form part of the One school records, and the Respondents evidence. This goes against the witness credibility.

They were submitted to the HRC and appear in the beginning of the file.

Erratum having been made in error.

10. Contempt of court;

The respondent has also shown contempt of court, Contempt in the face of the court is an act which has the tendency to interfere with or undermine the authority, performance or dignity of the courts or those who participate in their proceedings:

Witham v Holloway (1995) 183 CLR 525 per McHugh J at 538-539.

The respondent's evidence has caused the court to Fall in Error.

In relation to the respondent's contempt, (by lying to the court and altering documents), which is also FRAUD upon the court, the respondent, made the court an inadvertent instrument of inJustice.

Justice Rangiah has ERRED in making a finding of fact or facts on important issues which could not be supported by the evidence. Justice Rangiah has applied an incorrect principle of law.

11. Comparator;

Justice Rangiah has accepted and compared this case to another case (Purvis) and the Judge has accepted that the state of QLD has provided evidence to support its claim that Beau was not discriminated against, and referenced parts of that case, which conflict with the judgement. Accepting the comparator in that case, which is an Error on the Judges behalf, as there are major discrepancies in the Purvis case compared to Beau's case.

Evidence was not presented by the respondent to back its defence that it alleges compares to that case (Purvis).

What appears not, does not exist, and nothing appears judicially before judgement.

The only comparators between the two cases are;

i. Two separate children that attended separate schools with disability(s},

ii. They both claim discrimination.

The main issues in Purvis, are that Daniel did NOT suffer restraint, and was NOT Locked in a room (Jail cell). In Beau's case, he was never expelled from Kawungan State School (KSS).

Justice Rangiah states the "burden of proof' is on Peter connor,

to prove that the state did treat Beau differently from another child without a disability.

During the hearing (Trial) Peter connor questioned the State's witnesses, they were asked;

1. Whom was put in the Special Education Program (SEP) withdrawal room (Jail cell), and they stated "ONLY SEP students", (Like Beau).

2. Were other students without a disability put in that Jail cell, and they stated "NO".

Peter connor does not need to provide any other evidence, as this is the states evidence and it is on record. The Judge has ERRED here in this finding of fact.

Judge has conceded the other points in the statement of claim, and agreed Beau has suffered a detriment, being discrimination in itself.

Justice Rangiah has ERRED in focusing on the "behaviours of concern", that caused the issues, He has ERRED in comparing the case of Purvis with Beau's Case, where Beau's treatment was certainly worse once he was formally diagnosed (verified) with Autistic Spectrum Disorder, ie; (locked in the room more frequently).

Was the behaviour "Consciously Intentional", the Judge has accepted it is,

A conflict exists it seems in p272,

"Beau's behaviours, in view of the evident severity of his disabilities and the behaviours they produced', Judge accepts they were not Consciously Intentional.

Conflicting with his judgement that his behaviour was "Consciously Intentional".

The Judge has ERRED by overlooking the lack of training and compassionate understanding of the underlying psychological issues Beau was already dealing with. Beau was sent to a Special environment; Special Education Program (SEP) and Positive Learning Centre (PLC) because of these issues and the parents had a right to expect that Beau would be treated with a reasonable amount of care and consideration, dignity and respect from professionals, instead Beau was Excluded. Clearly Discrimination and Breach's of the Equality Act 2010.

There is also little relevance to this case in the Precedent (Keitel) other than the fact the child was put into Solitary confinement like Beau, "for LONG periods of time ", in fact it mirrors the exact same treatment as Beau was exposed to at Kawungan State School.

http://wwwB.austlii.edu.au/cgibin/viewdoc/au/cases/cth/FCA/2011 /1301.html

Error in procedendo - procedural error (in court) Error on a point of law or procedure (vs. error in iudicando).

Justice Rangiah has made a finding of fact or facts on important issues which could not be supported by the evidence. Justice Rangiah has applied an incorrect principle of law.

12. Applicant's Expert Witness's;

Justice Rangiah has not accepted the evidence of the applicants, not one, but two professional witness's. Two professional reports from Experts, where as the Judge is not an Expert in Psychology, Education, Restraint or Seclusion.

Neither were objected to with facts or points of law.

Error in procedendo – procedural error (in court) Error on a point of law or procedure, (vs. error in iudicando). Breach of Natural Justice and procedural process.

Judge has not accepted the Connor’s claims, and evidence, yet agrees with them in points.

13. Error / Irrelevance;

Justice Rangiah has made an error in saying "its Julie 's dad in prison': when in fact he's not.

He also mentions Maryborough prison, and this was not induced into evidence.

There is also absolutely NO relevance of this point to the case.

erratum having been made in error.

vel non or not Used when considering whether some event or situation is either present or it is not.

14. Abuse of the child;

Peter Connor has argued enough in the pleadings, that "Beau was exposed to collateral abuse". Justice Rangiah accepts that, by stating that Beau Suffered a Detriment.

Why was the room "Demolished" if it was in accordance with the standards.

Why did NO room exist at Urangan Point State School, if Beau was so much Trouble, this is proof the room (As Margaret stated) was a "Trigger'' for Beau's Behaviour of concern.

Justice Rangiah has accepted that Beau suffered a detriment at the hands of the school.

15. Article 7 International Civil and Political Rights;

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. In particular, no one shall be subjected without his free consent to medical or scientific experimentation.

Is consent to something that they (the DepUSchool) should know; and have a duty to know, is unlawful, is irrelevant.

16. Staff Qualifications;

Non qualified staff drafted plans, including the Functional Behaviour Assessment (FBA).

Justice Rangiah has ERRED in accepting a finding of fact.

Judge has ERRED in accepting that a NON Board Certified Behaviour Analyst or someone supervised by a Board Certified Behaviour Analyst completed the Functional Behavioural Assessment, (As Mcnamara was Not qualified as such, and gave evidence that She herself drafted the ONLY Functional Behavioural Assessment.)

As upon finalisation of such an assessment, an intervention plan be developed and implemented based on that assessment.

Margaret Webb testified that these should be done atleast once a year, preferably Biannually, this was not done, and the only one tendered to evidence was unsigned and dated 2011 .

Justice Rangiah has ERRED in making a finding of fact or facts on important issues which could not be supported by the evidence.

Justice Rangiah has applied an incorrect principle of law.

17. Detriment/ Discrimination;

Judge has accepted that Beau has suffered a detriment due to the actions of the school, (Seclusion/Suspensions) but does not accept discrimination, this conflicts with the Judgement in multiple instances.

“Detriment” is a legal term. It means unfair action by an Employer against an Employee during the employment which falls short of an actual dismissal.

In Ministry of Defence v Jeremiah [1980],

the Court of Appeal considered the meaning of detriment in the context of discrimination.

Justice Rangiah has applied an incorrect principle of law.

Justice Rangiah has ERRED in making a finding of fact or facts on important issues which could not be supported by the evidence.

18. Same Treatment;

In 2014 in Ms Brooke's class, during this period Beau sustained very few seclusions in the gaol cell, he was minimally restrained , and not suspended. This was at the same school.

In late 2015 Beau was moved to UPSS, he stayed there until mid 2017,

Beau sustained one restraint, and no seclusions, and no suspensions.

These are significant points the Judge has ignored.

18 By the written submissions that were advanced in support of his appeal, Beau identified (and addressed) 24 discrete appeal grounds. They included all of the 18 grounds referred to in his notice of appeal, plus six others. At the outset of the appeal hearing on 5 November 2020, Connor—who, as he had done below, continued to self-represent—was advised of the need to adhere to the appeal grounds that were nominated in the notice of appeal. The oral submissions that he then made reflected the grounds of appeal that found expression in that notice.

19 The hearing of the appeal commenced on 5 November 2020. When the court rose that afternoon, Connor had completed his submissions in chief. The matter was scheduled for a second day of hearing on 17 November 2020. On 13 November 2020, Connor filed an interlocutory application to amend the notice of appeal so as to incorporate seven additional appeal grounds. None of the additional grounds was adequately particularised; each was, instead, listed summarily as follows (with numbering following from the 18 appeal grounds contained within the initial notice of appeal):

19. International covenant on the Rights of the Child, Jus Cogens

20. Model litigant guidelines.

21. Deloitte review on Students with Disability in QLD schools 2017– EQ

22. Amendment to Statement of claim (pleadings)

23. Costs;

24. Extrinsic Fraud / Vicarious Conduct

25. Abuse / Vicarious Conduct

Six of those seven additional grounds that were sought to be incorporated into the appeal were the subject of Beau’s initial written submissions. One—ground 25—was entirely new.

20 At the resumption of the appeal hearing on 17 November 2020, the court indicated that it would not permit Beau to press proposed ground 25; but that it would otherwise consider whether or not to permit (or the extent to which it might permit) the agitation of the other additional proposed grounds in the context of its judgment on the appeal (and having regard to what was said about them in Beau’s initial written submissions). Before the court, then, are:

(1) the 18 discrete grounds of appeal to which the original notice gave voice (above, [17]); and

(2) six additional grounds of appeal in respect of which Beau requires the leave of the court to agitate.

21 For reasons that will become apparent, it is convenient to group the 24 discrete grounds—that is, the 18 existing grounds and the six additional grounds in respect of whose agitation Beau requires the court’s leave—into five categories, namely:

(1) grounds that convey extreme allegations for which there is self-evidently no proper basis (this category covers grounds 8 and 10, and proposed ground 24);

(2) grounds by which no error is particularised, much less established (this category covers grounds 2, 4, 5 and 15, and proposed grounds 19, 20, 21 and 23);

(3) grounds that involve procedural matters (this category covers grounds 1, 3 and 7, and proposed ground 22);

(4) grounds that seek to impugn the primary judge’s findings of fact (this category covers grounds 6, 9, 12, 13 and 16); and

(5) grounds that challenge the primary judge’s conclusions of law (this category covers grounds 11, 14, 17 and 18).

Principles governing the amendment of the appeal notice

22 The principles governing the amendment of notices of appeal were not the subject of submissions but, in any event, are notorious enough. It is not necessary to recite them at length, save to observe that leave ordinarily will not be granted to permit on appeal the agitation of an additional ground that lacks reasonable prospects of success: Odzic v Commonwealth (represented by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development) [2017] FCAFC 28, [71] (Kenny, Robertson and Griffiths JJ). For the reasons mapped out below, none of the six proposed grounds that Beau hopes to incorporate into his notice of appeal enjoys prospects rising to that level and, for that reason, leave will be refused in respect of each.

Category One: extreme and unfounded allegations

23 The grounds—existing and proposed—that comprise the first category need not be repeated. It suffices to note that they charge the respondent with very serious misconduct and are, in each case, wholly without foundation. It is tempting—and probably appropriate—to say nothing further about them; but two observations bear noting.

24 First, there is an apparent (indeed obvious) overlap between the allegations inherent in the grounds that comprise this first category (on the one hand) and the alleged errors of fact that are the subject of grounds that comprise the fourth category (on the other). It is to be understood that Beau and Connor take the view that the primary judge was wrong to draw the factual conclusions contemplated by the grounds that comprise that fourth category. The allegations inherent in the grounds that comprise this first category are not necessary in order to establish those errors (if they exist).

25 Second and with due respect, the extreme nature of the allegations that are made and the wholesale absence of any proper basis for making them are likely attributable to an exuberance that occasionally attends self-representation. That is not to excuse the making of allegations that ought not to have been made; but it may explain their making. It should go without saying that litigants—no matter how inexperienced—should always refrain from making serious criminal or quasi-criminal accusations for the making of which they have no proper basis.

26 None of the discrete grounds that comprise this first category is made out. Grounds 8 and 10 are rejected, and we do not grant leave to agitate proposed ground 24.

Category two: grounds that fail to particularise error

27 Again, it is not necessary to replicate the grounds that comprise this second category. It suffices to note that none of them properly alleges any error on the part of the primary judge that this court might correct on appeal. Although there was some elaboration in the written and oral submissions that were advanced in support of them, they too failed to identify, let alone establish, any such error. Over the course of the hearing of the appeal, it became apparent that many (and perhaps all) of the grounds in this category were directed to subjects that are also covered by other grounds in other categories (principally those that seek to challenge various of the primary judge’s findings of fact).

28 By way of example, the written submissions that Beau advanced in respect of ground 4 read as follows (errors, formatting and emphasis original):

4. Justice Rangiah has applied an incorrect principle of law; See p8, 10, 11, 16, 17

House v The King 1936 40 - 55CLR499 The Majority held that it must appear that some error has been made in exercising the discretion. The majority (Dixon, Evatt & McTiernan JJ) identified five errors that would lead the appellate court to exercise its own discretion in substitution for that of the sentencing judge:

1. The judge acted on a wrong principle, 2. The judge allowed extraneous or irrelevant matters to guide or affect him, 3. The judge mistakes the facts, 4. The judge does not take into account some material consideration, or 5. The sentence (Judgement) is unreasonable or plainly unjust.

The Applicant claims all of the points relevant to it’s appeal. (24) these are paragraph numbers not page numbers - (25) As the applicant is limited pages (10) allowed for written submissions it makes it difficult to expand on the facts, and argument by the applicant, this will be expanded on in the applicant’s verbal submissions. The basis are noted in the intention to appeal and submissions.

(26) The applicant’s submissions, evidence and facts are all inclusive and highlight the relevant errors Judge Rangiah has made at law. The primary being that he has allowed the Respondents witness’s testimonies, evidence to form his basis for judgment and inadvertently used the court as a vehicle for injustice. He is not a professional and dismissed the applicants expert witnesses without just cause, Judge Rangiah is NOT an EXPERT in either Education or Psychology.

29 Again, it is apparent that Beau takes issue with some of the primary judge’s findings of fact. At the risk of repetition, those concerns are covered by other appeal grounds that are addressed below. With respect, the “incorrect principle of law” upon which the primary judge is alleged to have acted is not apparent.

30 All of the other grounds comprising this second category are similarly unclear. Intending no disrespect (and appreciating the difficulties that typically attend upon self-represented litigants), the submissions advanced in support of them did not alter that reality and, in many respects, were unintelligible.

31 None of the grounds that comprise the second category referred to above is sustainable. Grounds 2, 4, 5 and 15 are rejected. We do not grant the leave that is required to agitate proposed grounds 19, 20 or 21. Proposed ground 23—by which, so far as we understand it, Beau seeks to recover his costs in the event that the appeal succeeds—is less an allegation of error than an assertion of entitlement to costs. For obvious reasons, nothing more need be said about it.

Category three: procedural grounds

32 A number of Beau’s grounds (and proposed grounds) concern matters of process that attended the trial before the primary judge. Perhaps again spurred by the exuberance of self-representation, Connor sought, in the appeal, to impress upon the court what he considered to be various procedural transgressions that impacted upon the way that the primary judge determined the matter.

33 Perhaps the most significant of those focused upon the primary judge’s receipt of an electronic version of the court book that had been prepared for the purposes of the trial. That was said to have occurred after the hearing of the trial had concluded. A copy of the electronic content handed to the judge (presumably via his associate or other court staff) was also provided to Connor; but Connor’s apparent concern is that he had no way of knowing precisely what was or was not provided to the court. So far as we were able to follow the submission, it was suggested that the court’s receipt of that material amounted to an abuse or misuse of process (ground 1) or procedural fairness (ground 3).

34 There was nothing remarkable or sinister about the primary judge’s receipt of the electronic court book. Connor does not suggest that the material provided to the court was not also provided to him. There is no suggestion, for example—much less any proper basis upon which to suggest—that the primary judge was led to decide the matter as he did on the strength of material with which he had surreptitiously been armed or that had deliberately been withheld from Connor (and Beau). The complaint, simply enough, is that that might have transpired. With due respect (and, again, appreciating the difficulties that this matter presents for both Connor and Beau), there is an unhelpful scent of paranoia to that submission and we reject it without hesitation.

35 Ground 3 (or, at least, the written submission that was advanced in respect of it) concerns interlocutory decisions made by the primary judge throughout the course of the trial. At least one such decision concerned an attempt by Connor to amend Beau’s statement of claim (an occurrence that is also the subject of proposed ground 22). In his written reasons, the primary judge made the following observations about that application (Primary Judgment, [29]):

On the seventh day of the nine day trial, Peter Connor sought leave to file an amended statement of claim. It sought to raise new allegations against staff of the School including attempted murder, abuse, deprivation of liberty, assault and battery, denial of medical attention, trespass, torts alleged against former lawyers and breaches of various regulatory provisions. I ruled that leave should not be granted, given that some of the new allegations were outside the jurisdiction of the Court or could not appropriately be brought within the present proceeding, and all were inadequately particularised and would cause prejudice to the State as they were raised too late…

36 Plainly enough, the primary judge had a discretion to rule as he did. He had a similar discretion to rule on the other interlocutory applications made throughout the course of the trial. It is not as clear as would be preferable what other such applications were made; but there was some suggestion before us that, during the trial, Connor had sought to compel testimony from a number of witnesses associated with Beau’s new school, the Urangan State School. The primary judge did not accede to that request.

37 In order to impugn the exercise of those discretions, it would be necessary for us to find that, in each case, they miscarried in any one or more of the ways famously outlined by the High Court in House v R (1936) 55 CLR 499 (especially at 505). Again with due respect, it is not apparent how it might be thought that his Honour’s discretion to make any of the interlocutory rulings referred to above miscarried in any such way or ways. We do not accept that it did.

38 By ground 7, Beau charges the primary judge with error insofar as his Honour recorded the respondent’s concession that he had a disability for the purposes of the DD Act (Primary Judgment, [235]). That, so Connor explained, was never conceded. Even assuming that he is right about that, it does not equate (by itself) with the primary judge having erred in any way that this court might correct on appeal. Whether the concession was made or not, the primary judge accepted the proposition that Beau advanced as to the disabilities under which he relevantly laboured. The existence of any concession on the part of the respondent is irrelevant.

39 Grounds 1, 3 and 7 are, therefore, rejected. We do not grant leave to amend the notice of appeal so as to incorporate proposed ground 22.

Category four: grounds concerning fact-finding

40 The grounds of appeal comprising the fourth category (above, [21]) all seek to impugn findings of fact made by the primary judge, specifically:

(1) his Honour’s finding (Primary Judgment, [287]-[288]) that, on the occasions that Beau was subjected to restraint or seclusion, that occurred in accordance with guidelines to which his mother consented (that finding is made the subject of challenge in the appeal by ground 6);

(2) his Honour’s finding (Primary Judgment, [289]) that Beau was only restrained as a “last resort in circumstances where he had hit, kicked or otherwise physically harmed students or staff or where his behaviour posed a risk of harm to students, staff or Beau himself” (that finding is made the subject of challenge in the appeal also by ground 6);

(3) his Honour’s rejection (Primary Judgment, [99], [109]-[112]) of the expert evidence that was led on Beau’s behalf (which is made the subject of challenge in the appeal by ground 12);

(4) his Honour’s observation (Primary Judgment, [68]), apparently sourced from a record created by the School, that Beau’s maternal grandfather was in prison (that observation is made the subject of challenge in the appeal by ground 13); and

(5) findings (Primary Judgment, [334]) that a “2013 Class Behaviour Management Plan” and two “Individual Behaviour Support Plans” that were adopted by the School were sufficient to qualify as “Functional Behaviour Assessment[s]”, as defined by Beau’s statement of claim (those findings are made the subject of challenge in the appeal by ground 16).

41 Ground 9 raises an additional factual challenge, the particulars of which are more difficult to discern. It charges the primary judge with having “overlooked the fact [that Mr] Boss-[W]alker stated [that] he was only employed at [the School] from 2014 [and yet, somehow], he authored documents in 2012 and [20]13”. That was said to “…go[] against the witness credibility”.

42 The principles governing the appellate review of factual findings are well-settled. An appeal from a judgment made in the exercise of the court’s original jurisdiction proceeds as an appeal by way of rehearing: Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1, 87 [70] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ). The susceptibility of factual findings to review in such an appeal depends, in part, upon whether (or the degree to which) the facts in question were the subject of conflicting oral testimony. Facts found by means of inference or on the basis of evidence that was not the subject of challenge are typically more susceptible to review than those that are founded upon the acceptance or rejection of conflicting oral testimony. In Kelso v Tatiara Meat Co Pty Ltd (2007) 17 VR 592, Dodds-Streeton JA (with whom Buchanan, Nettle, Ashley and Kellam JJA agreed) explained the distinction (at 620 [150]) as follows:

…As Warren v Coombes, the authorities approved therein and subsequent High Court decisions such as Fox v Percy and Della Maddalena make clear, the appeal court must consider the record of the trial below and the judgment of the trial judge, together with any additional evidence admitted. It must reach an independent conclusion on all issues which it is as well placed as the trial judge to determine, such as the assessment of documents, expert reports which are independent of the credit of any witness seen by the trial judge and inferences from established fact. It must also independently determine matters in which the trial judge enjoyed a legitimate advantage, such as the observation of witnesses, physical demonstrations and other matters referred to in Fox v Percy and like cases, but must make appropriate allowance, without uncritical deference, for such an advantage. If it reaches a different conclusion, either on any specific issue or the ultimate outcome of the case, it must give effect to its own decision.

43 With one possible exception (to which we shall shortly return), all of the facts that Beau seeks to impugn on appeal were the subject of conflicting oral evidence. That evidence was the subject of lengthy analysis in the Primary Judgment and it is not necessary to replicate that analysis here. It suffices to note that all of the findings that are sought to be impugned were open to be drawn on the evidence with which his Honour was furnished and that his Honour was better placed than we are to assess what aspects of that evidence ought properly to have been accepted or rejected. Making appropriate allowances for the usual advantages that a trial judge enjoys, we are unpersuaded that any of the factual conclusions that Beau seeks to impugn were wrongly arrived at. On the contrary, we agree with the relevant findings and with the reasons that his Honour gave for reaching them.

44 The “possible exception” concerns the finding that is the subject of appeal ground 13 (regarding Beau’s grandfather). It was not in contest—nor was it in any obvious way relevant—that Beau’s maternal grandfather is not (and was not) in prison. There was, before his Honour, a record belonging to the School that suggested that he was. It is not controversial that that record was inaccurate; but his Honour does not appear to have done anything beyond accurately reciting its inaccurate content. His doing so had no bearing on the outcome of the matter.

45 None of the discrete grounds that comprise this fourth category is made good. We therefore reject appeal grounds 6, 9, 12, 13 and 16.

Category five: incorrect legal conclusions

46 By the grounds comprising the fifth category identified above (at [21]), it is said that the primary judge committed errors of law insofar as he concluded that the detriments to which he found that Beau was subjected whilst enrolled at the School did not constitute discrimination on the grounds of disability under the DD Act.

47 Distilling them to their essence, the grounds that comprise this final category proceed on the basis that, having determined that Beau was subjected to various forms of detriment (suspension, restraint, etc) due to the conduct in which he engaged because of his disabilities, the only legal conclusion that it was open to the primary judge to draw was that Beau had been unlawfully discriminated against by reason of those disabilities.

48 That basic premise is at least superficially sound, in the sense that there is (and was) an obvious connection between Beau’s disabilities and the behaviour that they spawned (on the one hand) and the detrimental treatment to which he was subjected (on the other). Nonetheless, the premise fails. Whatever might be said of the connection just described, it is clear on present authority that it is insufficient to ground the finding of contravention that the court was invited to draw.

49 As the primary judge noted (Primary Judgment, [237]), the circumstances of this case are materially similar to those that the High Court considered in Purvis v New South Wales (2003) 217 CLR 92. That case concerned a student who was expelled from his school because of the violent behaviour in which he had a tendency to engage. It was accepted that that behaviour was a consequence of the intellectual disabilities by which he was afflicted. The appellant contended that, for the purposes of s 5(1) of the DD Act (above, [13]), the appropriate comparator was a student who did not possess the same disabilities and who, therefore, did not engage in the same aggressive behaviour. In other words, he contended that he had been discriminated against because the school had (by expelling him) treated him less favourably than it would have treated another student who, not labouring under the same disabilities, did not engage in the same violent behaviour.

50 That contention was rejected. Gleeson CJ held (at 102 [13]):

The fact that the pupil suffered from a disorder resulting in disturbed behaviour was, from the point of view of the school principal, neither the reason, nor a reason, why he was suspended and expelled. It is the school authority that is the alleged discriminator, and it is the reason or reasons for action of the responsible officers of the school authority that is or are in question. It is their conduct that is to be measured against the requirements of the [DD] Act. If one were to ask the pupil to explain, from his point of view, why he was expelled, it may be reasonable for him to say that his disability resulted in his expulsion. However, ss 5, 10 and 22 [of the DD Act] are concerned with the lawfulness of the conduct of the school authority, and with the true basis of the decision of the principal to suspend and later expel the pupil. In the light of the school authority’s responsibilities to the other pupils, the basis of the decision cannot fairly be stated by observing that, but for the pupil’s disability, he would not have engaged in the conduct that resulted in his suspension and expulsion. The expressed and genuine basis of the principal’s decision was the danger to other pupils and staff constituted by the pupil’s violent conduct, and the principal’s responsibilities towards those people.

51 Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ (with whom Callinan J relevantly agreed) held to similar effect (at 161-163 [224]-[236]).

52 In Walker v State of Victoria [2012] FCAFC 38, Gray J (with whom Reeves J agreed) applied that reasoning, holding that (at [73]):

When dealing with discrimination by less favourable treatment, it is clear that the proper comparator is a student with the same behavioural characteristics, but without the disabilities, of the student in respect of whom such discrimination is alleged.

53 Applying that reasoning to the present case, whether or not Beau was discriminated against contrary to s 22(2) of the DD Act turned upon whether the various detriments to which he was subjected were detriments to which the School would have subjected other students who did not labour under the same disabilities but who nonetheless exhibited the same disruptive behaviours. That was the question to which the primary judge directed himself and, with respect, he was correct to do so. His Honour found—as he was entitled to on the strength of the evidence before him—that the School would not have treated a student who did not possess the same disabilities as Beau any differently had he or she engaged in behaviour similar to that in which Beau engaged (Primary Judgment, [251], [256], [289], [295]).

54 There was no error of principle inherent in his Honour’s reasoning. We therefore reject the grounds that comprise this final category (grounds 11, 14, 17 and 18).

Conclusion

55 None of the grounds in the notice of appeal is made good and we do not grant leave to add any of the additional grounds that Beau has sought to agitate. The appeal must be dismissed. We will make the usual order as to costs.

I certify that the preceding fifty-five (55) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Reeves, Perry and Snaden. |