Federal Court of Australia

Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc [2020] FCAFC 235

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The cross-appeal be allowed.

3. The orders made by the primary judge on 29 May 2020 be amended by the addition of the following declarations:

2A. The first and second respondent have, in the period since 23 June 2017, infringed the In-N-Out Trade Marks, being those trade marks bearing Australian Trade Mark Registration Nos. 563986, 563987, 1190205 and 1345820, by joining in the infringements of the first respondent that are referred to in order 1 above as joint tortfeasors.

...

6A. The first and second respondent have, in the period since 23 June 2017, engaged in the tort of passing off, by joining in the conduct of the first respondent that is referred to in order 5 above as joint tortfeasors.

4. The appellants pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.

5. The second and third appellants pay the respondent’s costs of the cross-appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[8] | |

2 THE REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE RELEVANT TO THE TRADE MARK APPEAL | [9] |

2.1 Background factual findings relevant to the trade mark appeal | [9] |

2.2 The primary judge’s consideration of the trade mark infringement claim | [35] |

[58] | |

[58] | |

[69] | |

[69] | |

[71] | |

[92] | |

[92] | |

[94] | |

[111] | |

[126] | |

6 NOTICE OF CROSS-APPEAL: THE LIABILITY OF MESSRS KAGAN AND SALIBA AFTER THE INCORPORATION OF HASHTAG BURGERS | [130] |

[130] | |

[134] | |

[136] | |

[142] |

THE COURT:

1 The business of In-N-Out Burgers, Inc (INO Burgers) was founded in California in 1948 and incorporated in that State on 1 March 1963. By May 2016, there were over 300 In-N-Out restaurants in the United States of America, each branded with the composite trade mark (INO logo) set out below and each selling, as its name suggests, burgers, as well as the normal accoutrements of fast food restaurants such as French fries and drinks:

INO Burgers also regularly hosts pop-up restaurant events outside the United States of America. At these events, consumers are exposed to its goods and services in addition to its branding. Since 2012, it has hosted several such events in Australia.

2 In May 2016, Benjamin Kagan and Andrew Saliba commenced using the name DOWN-N-OUT to promote restaurant services for the sale of fast food, including burgers, French fries and drinks. On 23 June 2017, they incorporated Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd and became its sole directors and shareholders. Thereafter, Hashtag Burgers operated a growing number of burger restaurants under the name DOWN-N-OUT.

3 INO Burgers instituted proceedings against each of Hashtag Burgers and Messrs Kagan and Saliba (together, the appellants). In a decision published on 26 February 2020, the primary judge found that Messrs Kagan and Saliba were jointly and severally liable for trade mark infringement, passing off and misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (contained within Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) for their conduct prior to 23 June 2017. Thereafter Hashtag Burgers was so liable, and neither Messrs Kagan nor Saliba were found to be personally liable for its conduct found to constitute trade mark infringement and passing off. They were however found personally liable for misleading or deceptive conduct after Hashtag Burgers’ incorporation, having been found to be knowingly concerned in Hashtag Burgers’ contraventions of the ACL: In-N-Out Burgers, Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 193; 377 ALR 116 at [377] – [378]. The appellants now appeal from that decision and the orders made.

4 INO Burgers has filed a cross-appeal contending that the primary judge erred in finding that Messrs Kagan and Saliba were not liable as joint tortfeasors for the conduct of Hashtag Burgers found to constitute trade mark infringement and passing off.

5 The primary judge identified at [12] of her reasons the four registered trade marks that INO Burgers asserted in the infringement proceedings (the INO trade marks). Trade marks numbered 563986, 563987 and 1190205 are each for the INO logo (not limited in colour) and are relevantly registered in respect of services including restaurant services, and goods including hamburger sandwiches and cheeseburger sandwiches, or both. Trade mark number 1345820 is a word mark for IN-N-OUT BURGER, and the designated goods and services include burgers and food and drink restaurant services. The primary judge also set out in Annexure A to her reasons a table showing the DOWN-N-OUT marks and logos used by the appellants at various times in relation to their restaurants and the food and beverages offered for sale at those restaurants. Over time the appellants made small adjustments to the DOWN-N-OUT mark in response to INO Burgers’ demands.

6 In this appeal, it is unnecessary to refer to the differences between the INO trade marks and the variations between the appellants’ uses of the words DOWN-N-OUT (referred to collectively by the primary judge as the DNO marks) because, as noted by the primary judge at [87] and as we discuss in more detail below at [72], the trial was conducted on the basis that the relevant comparison was between the name DOWN-N-OUT and the word mark IN-N-OUT BURGER.

7 The first two grounds of appeal concern the primary judge’s findings that the impugned uses of various forms of the DNO marks by the appellants amounted to infringing use within s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth). The first ground challenges the findings of deceptive similarity on the basis that the evaluation conducted was not in accordance with established principles. For the reasons set out in more detail below, we reject this ground. The second ground challenges the primary judge’s conclusion that Messrs Kagan and Saliba adopted the marks for the deliberate purpose of appropriating the marks, branding or reputation of INO Burgers. We conclude that, with respect, the primary judge’s reasons involved some error, but that this error did not materially affect her conclusions as to deceptive similarity, which we do not consider should be disturbed. We also reject the third and fourth grounds which challenge the primary judge’s findings concerning misleading or deceptive conduct and passing off. However, we allow the cross-appeal, with the result that Messrs Kagan and Saliba are also liable as joint tortfeasors for trade mark infringement and for passing off.

8 In determining an appeal from a decision involving an evaluative process such as the present, an appellate court should be careful to distinguish between findings of error and disagreements in evaluation. As noted by Perram J in Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 261 FCR 301 (Allsop CJ and Markovic J agreeing):

49 ...[The court] must be guided not by whether it disagrees with the finding (which would be decisive were a question of law involved) but by whether it detects error in the finding. On the one hand, error may appear syllogistically where it is apparent that the conclusion which has been reached has involved some false step; for example, where some relevant matter has been overlooked or some extraneous consideration taken into account which ought not to have been. But error, on the other hand, may also appear without any such explicitly erroneous reasoning. The result may be such as simply to bespeak error. Allsop J said in such cases an error may be manifest where the appellate court has a sufficiently clear difference of opinion: Branir at 437-438 [29].

50 There may seem an element of circularity in this, but the sufficiently clear difference of opinion bespeaks not merely that the appellate court has a different view to the trial judge but that the trial judge’s view is wrong even having regard to the advantages enjoyed by the trial judge and even given the subject matter: Branir at 435-436 [24].

See also Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Careline Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 105; 264 FCR 422 (Murphy, Gleeson and Markovic JJ) at [35] – [37] and Verrocchi v Direct Chemist Outlet Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 104; 247 FCR 570 (Nicholas, Murphy and Beach JJ) at [45] – [47].

2. THE REASONS OF THE PRIMARY JUDGE RELEVANT TO THE TRADE MARK APPEAL

2.1 Background factual findings relevant to the trade mark appeal

9 Most of the relevant background facts were not in dispute, and were derived from documents. The primary judge found that in June 2015, Messrs Kagan and Saliba held a “Funk N Burgers” pop-up burger event at the Lord Gladstone Hotel in Chippendale, Sydney. The Facebook promotion for the event announced:

This time on the menu we have the legendary In’N’Ou … I mean the Down’N’Out burger served up ANIMAL STYLE for all you fatties. Go single or double-double that sexy MOFO.

10 On 10 June 2015, Messrs Kagan and Saliba worked with a graphic designer, John Paine, to prepare a flyer and logo for the event. Mr Saliba asked Mr Paine to make “a funk n burgers sign like in n out burger” and emailed him a copy of the INO logo. Mr Paine produced the following logo and a flyer incorporating it:

|

|

11 On 31 January 2016, Messrs Kagan and Saliba hosted another pop-up event advertised on Facebook as “FUNK-N-BURGERS: DOWN-N-OUT (IN-N-OUT TRIBUTE) ~FREE PARTY”. The promotion stated (without alteration):

WE ARE BACK FOR 2016!! To kick of[f] the new year we are bringing back the MOST POPULAR burger from last year … the In-N-Ou..*cough* I mean … Down-N-Out Burger – served ANIMAL STYLE for all you fatty boombas!

And if that wasn’t enough, every burger will be accompanied by ANIMAL STYLE fries with liquid cheese! Hrrrrrggggggggg…

Still not satisfied? DOUBLE-DOUBLE that sucka and turn your meal into a heart attack on a plate.

12 Sometime before 5 May 2016, Messrs Kagan and Saliba decided to open their first pop-up restaurant and call it DOWN-N-OUT. They again enlisted Mr Paine’s help with the design features. On 9 May 2016, Mr Saliba contacted Mr Paine attaching copies of three logos which the exchange indicates he designed himself (the Saliba logos):

| |

|

|

13 On about 13 May 2016, Messrs Kagan and Saliba hired a second designer, Olivia Tucker of Tablou Collective, to assist in the design and fit-out of the pop-up restaurant. Mr Kagan supplied her with copies of the Saliba logos.

14 On 25 May 2016, Mr Paine, who was designing the colour scheme for the Down-N-Out placemats and posters, told Mr Kagan that he would use yellow so that “it matches In and Out branding”. Mr Kagan said that was “cool”. In this same month the Down-N-Out Facebook page was launched. The initial cover photograph featured the following logo:

15 On 30 and 31 May 2016, Mr Kagan sent a media release to a number of organisations including Pedestrian Group TV and Timeout Magazine. It was entitled “Sydney’s Answer to In-N-Out Burgers Has Finally Arrived!” and read as follows:

SYDNEY'S ANSWER TO IN-N-OUT BURGERS HAS FINALLY ARRIVED!

Hashtag Burgers, the masterminds behind BURGAPALOOZA, are teaming up with the former Head Chef of Mr. Crackles to bring In-N-Out inspired burgers to Sydney's CBD for ONE WHOLE MONTH.

Launching Wednesday June 7th, the cheekily named DOWN-N-OUT will be popping up at the SIR JOHN YOUNG HOTEL on the corner of George and Liverpool Street, in the heart of the CBD.

The menu will be kept simple, similar to the original In-N-Out, with the addition of a vegetarian option. Of course there will be shakes and a plethora of secret menu hacks such as Animal Style and Protein Style. These will be leaked to the public as the pop-up continues.

In true Hashtag Burgers style, this won't simply be a food offering.

There are a few surprises planned for this pop-up and the Sir John Young Hotel is in the process of being redecorated – the details of which are being kept secret however you can find some hints on the DOWN-N-OUT Facebook page.

Hashtag Burgers will be partnering with Murrays Brewery to bring a craft beer pairing for the meal. They will be launching with Murrays’ famous Angry Man Pale Ale on tap.

This pop-up is the first in a series of plans by the Sir John Young Hotel to reboot its look and to revitalize the area which has been damaged by the lockouts. They plan to renovate the bar in the near future.

Down-N-Out will be launching at the SIR JOHN YOUNG HOTEL on the corner of George and Liverpool street on June 7th until the 6th of July.

Follow the DOWN-N-OUT Facebook page for more information[.]

16 On 4 June 2016, the following image was posted on the Tablou Instagram page:

17 Alongside the image the following announcement was made:

We’re teaming up with the @hashtag_burgers boys over this rainy weekend to bring In-N-Out down under …

18 Using the account @hashtag_burgers, Messrs Kagan or Saliba (or both) replied with positive emojis.

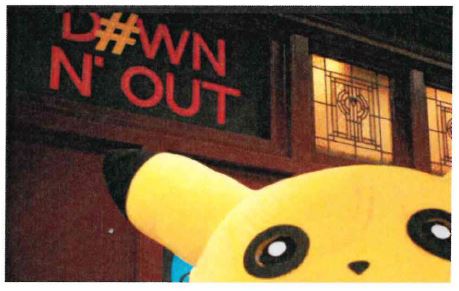

19 On about 7 June 2016, within six months of INO Burgers itself hosting a pop-up event in Surry Hills, Sydney, Messrs Kagan and Saliba opened their “cheekily-named” pop-up burger restaurant. The following sign (which the primary judge defined as the original DNO logo) was displayed at various locations, including above the entrance to the restaurant and on the wall above the open kitchen:

20 At some point in time that month, the following neon sign appeared outside the entrance:

21 Inside the restaurant, a blackboard menu was on display:

22 On 8 June 2016, Mr Khatri, a solicitor from Baker McKenzie retained on behalf of INO Burgers, attended the restaurant and took some photographs. The primary judge records that he also inquired about the “Secret Menu” and was told that it was “an Animal Style or Tiger Style burger or fries, or a Protein Style burger”. When he was asked what Tiger Style was, he received the answer “just Animal Style”. PROTEIN STYLE and ANIMAL STYLE are both trade marks owned by INO Burgers.

23 On 17 June 2016, INO Burgers wrote to Messrs Kagan and Saliba, requesting them to stop using its trade marks, ANIMAL STYLE and PROTEIN STYLE, and to select a different name and logo which sufficiently distinguished their business from that of INO Burgers so as to avoid confusion. The letter, which was signed by its Associate General Counsel, Valerie Sarigumba, was in the following terms:

We at In-N-Out Burger have heard from numerous international customers regarding your “Down-N-Out” tribute to In-N-Out Burger in Sydney. We were flattered to hear that you have admired our food and one-day events in Australia such that you decided to conduct a similar event. We also appreciate those who know what it means to have a good burger.

Nonetheless, the Down-N-Out event significantly trades off our well-known and valuable brand. For example, we note that as part of the event you have used the names ANIMAL STYLE and PROTEN STYLE, which are our registered trade marks, and adopting the name “Down-N-Out” displayed with a yellow arrow sounds and looks very similar to In-N-Out’s name and logo.

This may lead to some confusion amongst the Australian pubic that the In-N-Out is associated with the event (as reflected in some media reports to date). Even if you had the best of intentions, we still hope to avoid any such issues.

We therefore request that you do not use the above-mentioned trade marks. We also request that you select a different name for the remainder of this event and all of your future events that does not adopt In-N-Out’s name and logo.

24 Mr Kagan replied by email on 24 June 2016. He said they knew that “ANIMAL STYLE” and “PROTEIN STYLE” were “trademarked terms” and denied that they had ever been used for their menu items. He insisted that they were not trying to deceive customers or “rip-off” the In-N-Out brand. He advised that he and Mr Saliba intended to keep the name Down-N-Out, saying that they had legal advice that it did not infringe the In-N-Out trade mark. He asserted that:

This expression has its own separate and distinct meaning in the English language which is unlikely to conflict with the meaning of “In-N-Out”. Further, the word Down also relates to “Down Under” which relates to the fact that we are an Australian business.

25 On the other hand, Mr Kagan said that he understood INO Burgers’ concerns about the logo. He advised that, “as a temporary measure”, that is, until they could get new signs, they had covered up the arrows.

26 From then on a number of variations to the original logo started to appear.

27 A photograph of the DOWN-N-OUT sign on 24 June 2016, which Mr Saliba posted on his personal Facebook page, shows that the arrows had been obscured and that the word “censored” appears in upper case letters above and below the DOWN-N-OUT name where the arrow formerly appeared. In response to a query “What’s the deal with censored?”, Mr Kagan posted a photograph of part of Ms Sarigumba’s letter, advising that he had received the letter “the other day”. Mr Saliba replied saying he was going to get the letter framed and put on the wall at Down-N-Out.

28 On 29 June 2016, this variation of the original DNO logo appeared on the Down-N-Out Instagram page:

29 On 6 July 2016, two variations of the logo were posted on the Down-N-Out Facebook page:

|

|

30 On 6 and 7 July 2016, Mr Kagan advised Mr Paine of “some legal issues” and told him that “the main thing would be to change the sign and the arrow etc. but we might as well change the whole thing”. Mr Kagan informed Mr Paine that:

Need to differentiate ourselves ASAP before we get sued lol.

31 Mr Saliba told Mr Paine that the yellow arrow “definitely needs to go”. He then proposed a series of Down-N-Out logos using the same font and the same shade of red used in the INO logo. In response to a question apparently from Mr Paine about the problem INO Burgers had with “the previous images”, Mr Kagan responded:

To put it as simply as possible – each element on its own isn’t infringing on anything. But everything together is enough to fool the stupider people in society into thinking that we ARE In-N-Out

Secret menu, menu ingredients, logo, name etc.

…

Hehe — all a bit of fun really. We are now Sydney’s most controversial burger restaurant.

32 Although Mr Kagan had told INO Burgers that he understood its concerns about the original Down-N-Out logo, on 7 July 2016 he sent Ms Tucker a group of photographs featuring the original logo accompanied by the following text:

The fukd thing is we can[’t] post most of them anymore because of the In N Out issues lol. You guys can though

33 On 13 July 2016, the hyphens were removed from the signs at the Sir John Young Hotel and photographs showing the signs without the hyphens were posted on Instagram and the Down-N-Out Facebook page.

34 By late August 2016, new signs were installed. They differed from the earlier signs in the following respects. They included neither arrows nor hyphens and the “O” in “DOWN” was replaced by a hashtag. The following images were taken from Facebook posts on 30 August and 4 September 2016 respectively:

|

|

2.2 The primary judge’s consideration of the trade mark infringement claim

35 The primary judge provided a detailed and careful review of the law relevant to the assessment of whether an impugned trade mark is deceptively similar to a registered mark within s 120 of the Trade Marks Act. No party suggests that her Honour erred in her summary of the law. She then identified that the relevant dispute was whether or not the name DOWN-N-OUT was deceptively similar to the name IN-N-OUT, stating at [87]:

It was common ground that “In-N-Out” is the essential feature of all the INO marks. The evidence showed that the applicant’s restaurants are commonly referred to by that name. Since each of the INO marks either consists of, or includes as its essential feature, the name “In-N-Out”, it was common ground that, if the name Down-N-Out, in whatever form it appears or has appeared in the various DNO marks, is deceptively similar to the name In-N-Out, then the applicant succeeds in its claim with respect to all the DNO marks. That was so, despite the fact that all the applicant’s registered marks included the word “burger” and none of the respondents’ marks did. No doubt that was because “burger” is a “mere descriptive element” and is not apt to distinguish the relevant goods or services from those offered by other traders: Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd (2007) 251 FCR 379 at [52].

36 The primary judge noted that although there had been various punctuation changes (the removal of hyphens, the addition of an apostrophe) in the impugned uses of the DNO marks over time, the appellants did not contend before her that they were of any moment. She found that they were not. Her Honour also found that the substitution of a hashtag for the “O” in “DOWN” was also not a material point of distinction, noting that it made no material difference to the way that the mark would be pronounced (at [89]).

37 After summarising four contentions advanced on behalf of the appellants as to why the DNO marks were not deceptively similar to the INO trade marks, her Honour identified two questions that arose for consideration (at [99]): first, whether there was a resemblance between the competing marks; and secondly, if so, whether that resemblance was so close as to be likely to cause confusion, if not deception. Those questions conform to the structure of the statutory question posed in s 10 of the Trade Marks Act, to which we refer below at [60].

38 In relation to the first question, the primary judge considered the submission advanced on behalf of the appellants that the marks incorporate important visual differences. Relevantly, the appellants argued that the marks were visually different because: (1) the word DOWN looks nothing like IN; (2) the arrow in the composite INO trade marks is missing from the DNO word marks; and (3) the use of the hashtag in lieu of the “O” in DOWN since 30 August 2016 provides another point of distinction. She found that these distinctions were not material to her assessment of deceptive similarity, where “what counts is the impression the impugned mark would have on consumers of ordinary intelligence with an imperfect recollection of the registered marks” (at [100]). The primary judge said at [101]:

There is undoubtedly a visual resemblance between the competing word marks. For a start, they all finish with “N” followed by “OUT”. In addition, they all appear in sans serif fonts. The later adoption of a different colour scheme is immaterial since the applicant’s marks are registered without limitations as to colour and therefore are taken to be registered for all colours: TM Act, s 70. The respondents conceded that “N-Out” is an important component of the IN-N-OUT marks and that IN-N-OUT would be nothing without the “N-Out”. The respondents also conceded that the fact that it appears in the applicant’s marks provides some visual similarity between the competing marks. For the same reason there is also some aural similarity.

39 Her Honour then went on to consider the appellants’ submission that the respective marks do not sound alike, and that in conducting the necessary comparison, “due weight and significance” should be attached to the first part of the mark. Her Honour referred to each of the four authorities relied upon by the appellants to support the latter proposition (Re London Lubricants (1920) Ltd’s Application (1925) 42 RPC 264 (Sargant LJ) at 279; Johnson & Johnson v Kalnin [1993] FCA 279; (1993) 26 IPR 43 (Gummow J) at 221; Conde Nast Publications Pty Ltd v Taylor [1998] FCA 864; 41 IPR 505 (Burchett J) at 511; and Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Company GmbH [2001] FCA 1874; 54 IPR 344 (Lindgren J) at [160]) but noted that while English speakers might well emphasise the first syllable of a word in ordinary conversation, this was not universally so. In this respect her Honour referred at [107] to a case cited in Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks & Passing Off (Thomson Reuters, 6th ed, 2016) at [30.1550], where emphasis was placed on another syllable or on the later part of a word, being Upjohn Co v Schering AG (1994) 29 IPR 434 in which the suffix “velle” was found by a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks to be the essential element of the trade mark PROVELLE, and PROVELLE and NUVELLE were consequently considered to be deceptively similar. Her Honour also referred to Colgate-Palmolive Ltd v Pattron [1978] RPC 635 where despite the dissimilarity of the first syllables of COLGATE and TRINGATE, the Privy Council was persuaded that TRINGATE, when used in connection with toothpaste, was deceptively similar to the COLGATE mark.

40 Her Honour concluded by finding:

108 In any case, the “in” in IN-N-OUT BURGER is not a syllable, it is part of a phrase or expression. It is unlikely to attract any greater emphasis than “out”.

109 In my view, N-OUT is a distinctive and significant feature and an essential ingredient of all of the INO marks, just as “& GLORY” was an essential or distinguishing feature of the mark SOAP & GLORY in Soap & Glory Ltd v Boi Trading Co Ltd (2014) 107 IPR 574 at [33].

41 The appellants had also submitted that the idea or impression conveyed by the competing marks is different. It submitted that the impression conveyed by “down and out” is of a person, usually of disreputable appearance, without friends, money or prospects, whereas “in and out” connotes rapid inward and outward movement, an idea said to be reinforced by the arrow in the INO logo as well as the fact that it is used in connection with fast-food. Her Honour reasoned at [110]:

I accept that “down and out” and “in and out” can have different meanings. But meanings can change according to context...Focussing on the idea or impression created by the DNO marks, however, is apt to distract attention from the real question, namely, whether people with imperfect recollections of the applicants’ marks might be confused or deceived when coming across the respondents’ marks. What matters is the idea or impression carried away from seeing or hearing the applicant’s (registered) marks having regard to the surrounding circumstances. The idea or impression created by the registered marks is of fast-food, particularly burgers, and fast service. The respondents’ marks are being used with respect to the same kind of goods and services. The sort of deconstruction, if not reconstruction, in which the respondents engaged, albeit understandably, is an exercise the ordinary consumer is unlikely to undertake. A person seeing or hearing the registered marks might not be particularly struck by the “In”. After all, “in”, “out”, and “down” are all directional terms. As the applicant submitted, in the context in which they are used, at least some people may well understand DOWN-N-OUT (with or without the hyphens) to convey a similar idea to IN-N-OUT since “down” does not only mean “from higher to lower” but also means “into ... a lower position ...” (Macquarie Dictionary (4th ed, 2005)), as in “down the stairs and into the bar”, consistent with the location of the first DOWN-N-OUT pop up.

(emphasis added)

42 At [111] the primary judge found that although when compared side by side there are obvious differences in the design of the arrows in each of the appellants’ logo marks (see [19] and [20] above), the prominent use of the arrow in the INO logo provided a point of similarity with those. Furthermore, her Honour found that the arrow used in the appellants’ logo marks tended to reinforce a common directional idea with the INO logo.

43 The primary judge then turned to the second question that she posed, namely whether or not there was a real risk that a number of persons might be caused to wonder whether INO Burgers was the source of goods or services bearing the DOWN-N-OUT trade mark, or whether there was some association between INO Burgers and the appellants. To answer this question, the primary judge said it was necessary to examine two pieces of evidence.

44 The first was the evidence relied upon by INO Burgers to establish actual confusion. Her Honour reproduced the following schedule advanced by INO Burgers during its submissions:

Schedule of examples on Down N' Out’s Social Media Pages that associate or confuse Down N' Out with In-N-Out

Nature of document | Date | Comment | Court book reference |

Instagram post | 5 June 2016 | Heyitsjulian: “what?! In n out?!? Huh?!”

Heyitsjulian: “don’t play with my heart like that!! So confused” | Annexure A-27 to Harley affidavit at p194 |

Instagram post | 27 June 2016 | “…is this the in and out burger place???” | Cbv2.p755 |

Instagram post | 2 July 2016 | “… is this the same people as in n out??”: | Cbv2.p789 |

Facebook post | In or about April 2017 | “… in out of aus” | Cbv2.p792 |

Facebook post | In or about December 2016 | “the Aussie in n out burger” | Cbv2.p756 |

Instagram post | 7 June 2016 |

| Cbv2.p787 |

45 The primary judge said that in the absence of evidence of context and without being able to identify the people who posted the remarks, “it is difficult to put a great deal of weight on any of this evidence”, noting that it was conceivable that the posts were people “joking around on social media” and that, even if they were genuine instances of confusion, they were “few and far between” in the circumstances (at [115]). The primary judge later gave the evidence some probative value, saying at [118]:

...the evidence of the social media posts does have some probative value. On the face of things it raises the possibility that some people did wonder about the relationship between IN-N-OUT BURGER and DOWN-N-OUT, including after the arrows and hyphens were removed and the hashtag inserted. Importantly, neither Mr Kagan nor Mr Saliba saw fit to answer the questions raised by the posts or dispel the possibility of confusion, let alone take steps to remove them. It is reasonable to infer that they were happy to leave the question hanging.

(emphasis added)

46 Secondly, the primary judge considered the evidence of the appellants’ intentions. Her Honour noted at [120] that an inference may be drawn from evidence disclosing an intention to deceive or confuse, that deception or confusion is likely to occur. In support, her Honour cited Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills Limited v FS Walton & Co Ltd [1937] HCA 51; 58 CLR 641 at 657:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive.

47 The competing submissions before the primary judge were, for INO Burgers, that the inescapable inference is that the DOWN-N-OUT name and logos were deliberately chosen in order to obtain the benefit of market recognition of INO Burgers’ name, trade marks and branding. On the other hand, the appellants submitted that they were merely inspired by INO Burgers.

48 In this context, the primary judge found:

124 The evidence establishes that it was no coincidence that Messrs Kagan and Saliba settled on the name DOWN-N-OUT. The respondents’ own media release referred to the adoption of the name as “cheeky”, thereby owning up to their impudence. In closing argument, the respondents accepted that the “N-Out” was taken from the applicant’s trade name IN-N-OUT BURGER. They adopted the DOWN-N-OUT name, not to paint a picture of a person down on his luck, but to remind consumers of IN-N-OUT BURGER. On the face of the evidence, Messrs Kagan and Saliba chose the name DOWN-N-OUT because of its resemblance to IN-N-OUT. Why would they do that unless they believed that they would derive a commercial benefit from doing so?

…

128 When the first DOWN-N-OUT pop-up opened, “it broadly adopted the theme and style of an IN-N-OUT pop-up”, as the applicant put it, in that it was held inside a bar, offering a simple menu with three burgers and a “secret menu”. The so-called secret menu featured items the names of which, to the knowledge of Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, were registered trade marks of the applicant. The use by Messrs Kagan and Saliba of these names, together with the reference to the “secret menu” when the applicant’s “secret menu” also offered burgers in “Animal Style” and “Protein Style”, is likely to have fostered confusion. Having regard to the history and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it is reasonable to infer that in all probability that was their intention.

(emphasis added)

49 The primary judge noted that neither Mr Kagan nor Mr Saliba took any steps to dispel the possibility of confusion before they were served with the INO Burgers cease and desist letter, whether by replying to queries in the Instagram or Facebook posts or otherwise, and that the selection of a “N-OUT” mark together with the choice of font and the shade of red used for the DOWN-N-OUT name and the yellow arrow was designed to reflect INO Burgers’ branding. Furthermore, the primary judge noted that neither Mr Kagan nor Mr Saliba gave evidence, although both were present during the trial, and noted that the only persons who could give direct evidence as to the appellants’ intentions chose not to do so. Her Honour found that the inference was open from the evidence tendered by INO Burgers that the appellants:

132 ...adopted aspects of [INO Burgers] registered trade marks in order to capitalise on its reputation. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, that is the inference that should be drawn...In these circumstances, the choice of DOWN-N-OUT should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to confuse, if not deceive, consumers.

(emphasis added)

50 The primary judge accepted that the media release of late May 2016 distinguished DOWN-N-OUT from INO Burgers by describing the pop-up as “Sydney’s Answer to In-N-Out Burgers”, but concluded that:

133 ...in the absence of evidence from Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, the representations in the media release are not sufficient to dispel the inference or rebut the presumption that they intended at least to cause confusion. The similarities in the menus offered by the parties and their stated intention to use “Animal Style” and “Protein Style”, although they admittedly knew they were the applicants’ trade marks, support that conclusion.

51 As we explain below, [132] stands as a conclusion by the primary judge that Messrs Kagan and Saliba intended, by their selection of the name DOWN-N-OUT, to cause confusion. However, her Honour found that she would not have been disposed to conclude that Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba were being dishonest in their intention to appropriate aspects of INO Burgers’ marks but for two pieces of evidence.

52 The first is Mr Kagan’s denial, in his reply to INO Burgers’ letter of demand, that the appellants had ever used the terms “Animal Style” and “Protein Style” for their menu items. This, the primary judge concluded at [136], was a knowingly false statement lending weight to the inference that the appellants adoption of the name DOWN-N-OUT, and use of a yellow arrow for some time in their logo, was done for the purpose of appropriating INO Burgers’ reputation and, potentially, its trade.

53 The second concerns the appellants’ failure to comply with discovery obligations. In short, the primary judge noted that, despite assurances given by the solicitors representing the appellants that their clients had searched for documents and complied with discovery obligations, subpoenas issued to third parties yielded documents, many of which are summarised in section 2.1 above, that were not produced. The primary judge said at [151]:

Given the nature and quantity of this material, in the absence of evidence from Messrs Kagan and Saliba it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the respondents felt that they had something to hide by not discovering these documents in accordance with the original court order. I do not think it is insignificant, for example, that these documents included the disingenuous response to Mr Paine’s inquiry about the applicant’s problem with the DNO’s “previous images” in which Mr Kagan had replied that “the stupider people in society” could be fooled by the combination of “secret menu, menu ingredients, logo, name etc.” into thinking that they “ARE In-N-Out”. It will also be recalled that he appeared to treat the matter as “a bit of fun”.

(emphasis added)

54 We return to consider her Honour’s reasoning at [134] – [151] in the context of ground 2 of the appeal.

55 After completing her review of these matters the primary judge then said:

152 The only remaining question is whether the respondents achieved what they set out to do. In my opinion, they did. They sailed too close to the wind.

(emphasis added)

56 The emphasised words should be understood to be picking up the notion in Australian Woollen Mills at 657 that, having found that the appellants were dishonest traders who fashioned their marks as “an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers”, they should be regarded as providing a reliable and expert opinion on the question of whether what they had done was in fact likely to deceive. However, by adding “in my opinion they did”, it is also apparent that the primary judge did not supplant the apparent opinion of the appellants for her own, but rather went on to express her own opinion that the marks were deceptively similar, providing a summary of conclusions for doing so in the paragraphs that followed at [153] – [161]. The summary commences by noting at [153] that “[t]here is a sufficiently close resemblance between the two names to give rise to a real, tangible danger of confusion”, thereby picking up on the analysis provided in answer to the first question posed and considered by the primary judge in more detail from [100] – [111].

154 Having regard to the ordinary meanings of the word “down”, when used in relation to the sale of fast food, the sign DOWN-N-OUT might suggest to some potential customers that if they come down to, or into, the restaurant or bar they will be served quickly and, should they wish to take their purchases away, they will be able to leave quickly, the very notion suggested by IN-N-OUT. Further, upon seeing or hearing the name DOWN-N-OUT in connection with a burger restaurant, it is possible that some people with imperfect recollections of the INO marks might not remember that the first word used in those marks was “In”.

155 In any event, upon seeing or hearing the name DOWN-N-OUT used in connection with burgers, some people with an imperfect recollection of the INO marks might indeed wonder whether a burger restaurant called DOWN-N-OUT was IN-N-OUT BURGER or was in some way related to it, as at least one of the social media posts suggests. The use of “Down” in conjunction with “N-Out” in connection with the sale of burgers and related goods raises a reasonable doubt about whether there [is] a relationship between IN-N-OUT BURGER and DOWN-N-OUT. No evidence was led to indicate that “N-Out” or “N Out” had been used in the brand name of anyone other than the applicant before Messrs Kagan and Saliba decided to use it in DOWN-N-OUT to refer to their own burgers while at the same time referencing IN-N-OUT BURGER.

156 Besides, having regard to the ordinary meaning of “down and out”, the use of the name DOWN-N-OUT, with or without the variations in punctuation, to sell burgers and related goods, might also cause some people with an imperfect memory of the applicant’s marks to wonder whether the name refers to a down-market or “no frills” version of IN-N-OUT BURGER.

...

159 It is true that there are visual dissimilarities between the respective marks, which increased progressively over time. But none of these changes affected the impression created by the sound of the marks. That never changed. In Berlei Hestia, where there was no finding of visual similarity, BALI-BRA was held to be deceptively similar to BERLEI by reason only of the aural (“phonetic”) similarity of the two marks. Similarly, in Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co (1994) 49 FCR 89 (FC) the marks REVISE and LEVI’S were held to be deceptively similar because of their aural similarity, despite the obvious visual differences.

160 Whatever bearing it may have on their intentions, it is otherwise irrelevant that the respondents’ media release made it clear that the goods they would be serving did not come from the applicant. As Greene MR stated in Saville at 161:

In an infringement action, once it is found that the defendant's mark is used as a trade mark, the fact that he makes it clear that the commercial origin of the goods indicated by the trade mark is some business other than that of the plaintiff avails him nothing, since infringement consists in using the mark as a trade mark, that is, as indicating origin.

161 For all these reasons, I find that all the DNO marks infringed the applicant’s registered marks because they were deceptively similar to those marks in that they so nearly resembled the applicant’s marks that they were and are likely to cause confusion.

3. THE TRADE MARK INFRINGEMENT APPEAL (GROUNDS 1 AND 2)

58 The infringement findings of the primary judge depended on the application of s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act and the principles relevant to determining whether one mark is deceptively similar to another.

59 Section 120(1) provides:

A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

60 Section 10 provides the following in relation to “deceptively similar”:

For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be ‘deceptively similar’ to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion

61 The test for deceptively similarity has been long settled. In Australian Woollen Mills at 658, Dixon and McTiernan JJ described it as follows:

But, in the end, it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether in fact there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the new mark and title should be restrained.

In deciding this question, the marks ought not, of course, to be compared side by side. An attempt should be made to estimate the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers by the mark or device for which the protection of an injunction is sought. The impression or recollection which is carried away and retained is necessarily the basis of any mistaken belief that the challenged mark or device is the same. The effect of spoken description must be considered. If a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods, then similarities both of sound and of meaning play an important part. The usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected. Potential buyers of goods are not to be credited with any high perception or habitual caution. On the other hand, exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded. The course of business and the way in which the particular class of goods are sold gives, it may be said, the setting, and the habits and observation of men considered in the mass affords the standard. Evidence of actual cases of deception, if forthcoming, is of great weight.

62 A little while later, their Honours emphasised that the determination for the court is one of estimation and evaluation (at 659):

The main issue in the present case is a question never susceptible of much discussion. It depends on a combination of visual impression and judicial estimation of the effect likely to be produced in the course of the ordinary conduct of affairs.

63 The summary provided by Windeyer J in The Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd [1963] HCA 66; 109 CLR 407 at 415 also encapsulates the approach required by s 120(1):

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. The marks are not now to be looked at side by side. The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the plaintiff’s mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the defendant’s television exhibitions.

64 The distinction between consideration of whether one mark is deceptively similar to another, rather than substantially identical, lies in the point of emphasis on the impression or recollection which is carried away and retained of the registered mark, when conducting the comparison. In this context, allowance must be made for the human frailty of imperfect recollection. In New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray Goulburn Co-operative Company Ltd [1989] FCA 124; 86 ALR 549, in a passage in his judgment not affected by the proceedings on appeal, Gummow J said at 589:

In determining whether MOO is deceptively similar to MOOVE, the impression based on recollection (which may be imperfect) of the mark MOOVE that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have, is compared with the impression such persons would get from MOO; the deceptiveness flows not only from the degree of similarity itself between the marks, but also from the effect of that similarity considered in relation to the circumstances of the goods, the prospective purchasers and the market covered by the monopoly attached to the registered trade mark: Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 414–15; Polaroid Corp v Sole N Pty Ltd [1981] 1 NSWLR 491 at 498. The latter case is also authority (at 497) for the proposition that the essential comparison in an infringement suit remains one between the marks involved, and that the court is not looking to the totality of the conduct of the defendant in the same way as in a passing off suit.

This passage was approved by the Full Court in C A Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1539; 52 IPR 42 (Ryan, Branson, Lehane JJ) at [44].

65 It may be noted that the language of s 10 of the Trade Marks Act includes that a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another if it so nearly resembles the other that it is likely to “deceive or cause confusion”. The learned authors of Shanahan at [30.1005] explain that the distinction between “likely to deceive” and “likely to cause confusion” does not reside in some element of culpability in the user to be inferred from the word “deceive”, but in the effect of the trade mark on prospective purchasers. They observe that in Pioneer Hi-Bred Corn Co v Hy-Line Chicks Pty Ltd [1979] RPC 410 at 423 Richardson J, in the New Zealand Court of Appeal, said:

“Deceived’ implies the creation of an incorrect belief or mental impression and causing ‘confusion’ may go no further than perplexing or mixing up the minds of the purchasing public. Where the deception or confusion alleged is as to the source of the goods, deceived is equivalent to being misled into thinking that the goods bearing the applicant’s mark come from some other source and confused to being caused to wonder whether that might not be the case.

(citations omitted)

This passage was approved by the Full Court in Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721; 96 FCR 107 (Black CJ, Sundberg and Finkelstein JJ) at [39].

66 Section 114 of the Trade Marks Act 1905 (Cth) referred only to whether one mark was “likely to deceive”. The addition in s 10 (of the current Trade Marks Act) of “likely to deceive or cause confusion” brought the language into line with earlier English legislation, but was probably redundant. As Kitto J noted in Southern Cross Refrigeration Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd [1954] HCA 82; 91 CLR 592 at 594, the corresponding section of the English Act included “or cause confusion” but, “while these words make the section more specific, they add nothing to its effect”. Those words “likely to deceive” were wide enough to catch mere confusion, even though it was “unlikely to persist up to the point of, and be a factor in, inducing actual sale” (at 595). The Full Court on appeal (at 608) agreed that there will be deceptive similarity if there is a real risk that “the result of the user of the mark will be that a number of persons will be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products came from the same source”.

67 Despite the absence of a need for any defendant to have formed an intention to deceive or cause confusion, it may nevertheless be a relevant factor to take into account in the evaluation of deceptive similarity that the defendant did have that intention, as Dixon and McTiernan JJ explained in Australian Woollen Mills at 657.

68 However, the role of intention in the analysis should not be overstated. It is but one factor for the court to take into account in its evaluation. As the majority held in Australian Woollen Mills at 658, in the end it becomes a question of fact for the court to decide whether or not there is such a reasonable probability of deception or confusion that the use of the impugned mark should be restrained. That proposition may be demonstrated by noting that regardless of the mala fides of an alleged infringer, unless the impugned trade mark sufficiently resembles the registered owner’s mark, there cannot be a finding of deceptive similarity. To consider otherwise would be for the tail to wag the dog.

3.2.1 The appellants’ submissions

69 The appellants accept the primary judge’s summary of principles relevant to the assessment of a claim that a sign used as a trade mark is deceptively similar to a registered mark, but contend in the first ground of appeal that she erred in the application of those principles.

70 In particular, the appellants submit that the primary judge erred in her evaluation of deceptive similarity by: (a) failing to give weight to the presence of the word BURGER in the INO trade marks; (b) failing to assess the effect of the arrows in the composite INO trade marks; (c) placing undue emphasis on the “N-OUT” aspect of the INO trade mark and attributing insufficient significance to the difference between “DOWN” / “D#WN” and “IN”; (d) failing to give sufficient weight to the difference in meaning between the respective marks, and the ideas conveyed by those marks; (e) placing significant or dispositive weight on aural similarity and setting aside material visual differences between the marks; (f) framing the central question as one focussed on imperfect recollection; and (g) placing apparent weight on evidence of confusion from social media posts and no weight on the absence of evidence of actual confusion.

71 In our view, the criticisms made by the appellant in ground 1 are not made out.

72 The appellants first contend that the primary judge’s assessment began from an incorrect starting point because it removed from the equation the presence of the word “BURGER” in all of the INO trade marks, and also the arrow in three of those marks. The primary judge acknowledged at [87] that whilst all of the INO trade marks included the word “BURGER” none of the appellants’ marks did. She noted that the parties proceeded on the basis that if the name DOWN-N-OUT is deceptively similar to IN-N-OUT, in whatever form it appeared in the various marks, INO Burgers would succeed. That notation arose from counsel for the appellants at trial first, accepting that if INO Burgers established that the competing word marks (that is, “IN-N-OUT BURGER” and “DOWN-N-OUT”) were deceptively similar, it would succeed with respect to all of its marks; and secondly, accepting that because the competing marks were both used in relation to burgers, that less weight should be attributed to the inclusion of the word “burger” in the INO trade marks, it being manifestly descriptive in the circumstances. The appellants contend that the primary judge incorrectly recorded their concession that the word “BURGER” should be afforded less weight in the deceptive similarity assessment, as being that “BURGER” should be given no weight. However, considered in the context of the appellants having also conceded that “IN-N-OUT” was the essential feature of the “IN-N-OUT BURGER” word mark, and having regard to the transcript of the hearing, in our view it was open to the primary judge to characterise the appellants’ concessions in the way she did at [87]. In any event, it is apparent that her Honour did not proceed on the basis that the word “BURGER” was absent from the INO trade marks as may be seen from her Honour’s repeated references to the whole of the IN-N-OUT BURGER mark during her reasons (see for example [124], [130], [137] and [138]) and in the course of her summary of conclusions set out at [155] and [156]. Rather, she considered that, as a descriptive term, it was not a meaningful point of distinction and focussed, as the parties urged, on the essential feature, which was “IN-N-OUT”. Accordingly, the appellants’ submission is of no substance.

73 The appellants also contend that the primary judge failed to give weight to the use of the arrow logo in some of their trade marks. However, as we have noted, at [87] the primary judge correctly recorded the concession that the relevant point of comparison was between the word marks. The appellants should be held to the case that they ran below: Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc [2012] FCAFC 159; 99 IPR 1 (Keane CJ, Dowsett and Nicholas JJ) at [88] (Keane CJ); University of Wollongong v Metwally (No 2) [1985] HCA 28; 60 ALR 68 at 71.

74 The appellants next contend that, despite correctly identifying that IN-N-OUT is the essential feature of the INO trade marks, the primary judge proceeded to disassemble that feature to identify “N-OUT” as a “distinctive and significant feature and an essential ingredient” (at [109]). The appellants submit that it was by reference to this component of the words IN-N-OUT that her Honour found the marks to be deceptively similar, thereby placing undue emphasis on that aspect of the mark.

75 This criticism does not withstand a fair reading of the judgment. The primary judge noted at [101] that “[t]here is a visual resemblance between the competing word marks”, thereby referring to the entirety of those marks. She then correctly noted that the respondents conceded that the “N-OUT” component is an important part of the INO trade marks and gave her separate view that it was. A little later, in the context of addressing the appellants’ submission that the first word “DOWN” provides an important point of distinction, her Honour compared the relative significance of “IN” in the context of the whole of the phrase IN-N-OUT, and expressed the view that even without “IN”, “N-OUT” is a “distinctive and significant feature of all of the INO marks” (at [109]). That observation should not be understood to mean that her Honour concluded that the first word “IN” should be set to one side. In our view, her Honour did not do so.

76 In this context it may be noted that in her summary of conclusions at [155], her Honour made reference to the distinctiveness of the “N-OUT” component of the registered mark. No evidence suggested its use as a mark by any traders in respect of the relevant goods other than INO Burgers. In its particular rendition, the hyphenated form is a made-up suffix. IN-N-OUT BURGER as a whole is, indeed, a distinctive collocation, and the words N-OUT a distinctive component of that collocation. Distinctiveness is a factor that can legitimately be taken into account when considering deceptive similarity: see Stone & Wood Group Pty Ltd v Intellectual Property Development Corporation Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 29; 129 IPR 238 (Allsop CJ, Nicholas, Katzmann JJ) at [66]. For the reasons developed further below, we agree with her Honour’s assessment that “N-OUT” was a key visual and aural feature of the IN-N-OUT BURGER mark that the notional consumer would be likely to recall upon perceiving the DOWN-N-OUT mark.

77 Furthermore, we do not accept, as the appellants’ contend, that the primary judge erroneously placed reliance on an uncontested decision of the Trade Marks Office in reaching her view. Rather, her Honour observed at [109], no doubt for illustrative purposes, that her conclusion as to the significance of N-OUT was analogous to that decision.

78 The appellants next submit that the primary judge erred in her approach to assessing the meaning of the words IN-N-OUT as opposed to DOWN-N-OUT. They submit that the latter is a stylised abbreviation of the expression “down and out” which has several primary meanings including being destitute, being knocked unconscious in the boxing ring or defeated in some other endeavour. Further, the appellants submit that in this particular context, the word DOWN invokes the expression “down under” and a consequential cultural and geographic connection to Australia. By contrast, they submit, “IN-N-OUT” is an abbreviation of “in and out” which in this context creates the impression of “fast-food, particularly burgers, and fast service”. They submit that by placing undue emphasis on “N-OUT” the distinction between the two expressions was lost. They further contend that the primary judge’s comparison of the ideas of the marks paid no or insufficient regard to the ordinary meaning of “down and out”. These criticisms were particularly directed to her Honour’s reasons at [110] and [154].

79 In our view, these criticisms pay insufficient regard to the rigour with which the primary judge approached her judgment. In order to attend to each of the particular arguments advanced before her it was necessary, on occasion, to separate out the threads of the argument. In observing that the N-OUT aspect of the mark was a distinctive and significant feature of the INO trade marks, her Honour did not fail to recognise that the two marks could have different meanings. She said as much at the commencement of [110] (quoted at [41] above). Her Honour’s reasoning then takes account of the meaning of the phrase “down and out” and states that what matters (in the context of the competing arguments) is “the idea or impression carried away from seeing or hearing the applicant’s (registered) marks having regard to the surrounding circumstances” (at [110]).

80 The idea or meaning of a mark has a role to play in the analysis of deceptive similarity, although, as with many such tests, it forms only part of the overall analysis required to satisfy the statutory requirements of s 10 of the Trade Marks Act. An absence of visual or aural similarity is likely to lead to a conclusion that the two marks are not deceptively similar, despite similarity of idea. Section 10 provides emphasis on the requirement that a mark must so nearly resemble another that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion. As the High Court (Dixon, Williams and Kitto JJ) said in Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd [1952] HCA 15; 86 CLR 536 at 539:

… But it is obvious that trademarks, especially word marks, could be quite unlike and yet convey the same idea of the superiority or some particular suitability of an article for the work it was intended to do. To refuse an application for registration on this ground would be to give the proprietor of a registered trademark a complete monopoly of all words conveying the same idea as his trademark. The fact that two marks convey the same idea is not sufficient in itself to create a deceptive resemblance between them, although this fact could be taken into account in deciding whether two marks which really looked alike or sounded alike were likely to deceive. As Lord Parker said in the passage cited, you must consider the nature and kind of customer who would be likely to buy the goods.

(emphasis added)

81 (We note, however, that there may be room for debate on that subject. Section 10 requires that one trade mark so nearly resembles the other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion. Messrs Burrell R and Handler M, the learned authors of Australian Trade Mark Law (Oxford University Press, 2nd ed, 2016), point out at 214 – 215 that commonality of idea may be sufficient; see also Telstra Corporation Limited v Phone Directories Company Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 156; 237 FCR 388 (Besanko, Jagot, Edelman JJ) at [212].)

82 In Jafferjee v Scarlett [1937] HCA 36; 57 CLR 115, the idea of the mark was identified by the majority as a tool to assist in its analysis, in recognition of the fact that consumers, unlike a court, do not have the opportunity to compare marks side by side: see Latham CJ at 121 (with whom McTiernan J agreed at 126). Latham CJ noted that the usual circumstance is that a consumer will see one mark and have a memory of the other mark. Because, in the case of the legislation there under consideration, the issue is whether or not the consumer is likely to be deceived, and not whether on a side by side comparison of the two marks consumers might be deceived, the “idea of the mark” enables the court to place itself, as best as possible, into the mind of the consumer. At 121 – 122, the Latham CJ gave the example, quoted in Kerly on Trade Marks (1927, 6th ed) which in turn quoted Lord Herschell’s committee, of two different marks, one representing a game of football, and another representing a game of football where the players are shown in different dress and in very different positions yet still playing football, conveying what might be the same idea: a game of football. This example was said to illustrate the fact that it would be too much to expect people to be able to remember the exact details of the marks upon which they are in the habit of dealing. In a similar vein, in concluding that there was a real likelihood of deception, Dixon J considered it relevant to assess the “memory of the appellant's mark carried away by a buyer whose attention was directed to it only in the ordinary course of trade” (at 126). In Telstra Corporation the Full Court affirmed that whilst Jafferjee concerned marks that included images, the relevance of the idea of the mark is not confined to pictorial marks (at [213]).

83 In the present case, in her summary of conclusions, the primary judge noted at [154] that “some” potential customers might consider that “Down” in DOWN-N-OUT is used in a directional sense, but gave this prospect little apparent weight. She went on to note that some consumers with an imperfect recollection may not remember the first word of the IN-N-OUT BURGER mark at all. She then went on to say at [155]:

In any event, upon seeing or hearing the name DOWN-N-OUT used in connection with burgers, some people with an imperfect recollection of the INO marks might indeed wonder whether a burger restaurant called DOWN-N-OUT was IN-N-OUT BURGER or was in some way related to it, as at least one of the social media posts suggests.

(emphasis added)

84 This finding draws attention to the common N-OUT component in the marks that her Honour found was more likely to have a bearing on consumer perception than any distinctiveness arising from differences in meaning between the respective marks. It was apposite to consider that in the context of restaurant services and goods such as hamburgers, the notional consumer who is aware of IN-N-OUT BURGER, and takes with them an impression of that mark, would be caused to wonder whether there might be a connection with DOWN-N-OUT. There is no substance to the appellants’ criticism that her Honour had regard to the designated goods and services in respect of which the INO trade marks were registered in considering the question of the idea conveyed by the marks. As French J (as he then was) noted in Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd [1999] FCA 1020; 93 FCR 365 at [39] – [40] (Tamberlin J agreeing at [104]), whilst s 10 defines deceptive similarity solely in terms of the degree of resemblance of the trade marks in question, and whether that degree of resemblance is likely to deceive or cause confusion, in the end there is “one practical judgment to be made” which combines consideration of the relationship between the goods to which the impugned mark has been applied and the goods in respect of which registration has been obtained, as well as deceptive similarity between the marks:

...Whether any resemblance between different trade marks for goods and services renders them deceptively similar will depend upon the nature and degree of that resemblance and the closeness of the relationship between the services and the goods in question. It will not always be necessary to dissect that judgment into discrete and independent conclusions about the resemblance of marks and the relationship of goods and services. Consistently with that proposition, the Registrar or a judge on appeal from the Registrar could determine in a particular case that, given the limited degree of resemblance between the relevant marks he or she could not be satisfied, no matter how closely related the goods and services concerned, that the use of the applicant’s marks would be likely to deceive or to cause confusion.

85 The appellants next submit that the primary judge erred by placing significant or dispositive weight on aural similarity. They contend that the asserted phonetic similarity has its source in only the N-OUT component of the competing marks, and that the primary judge gave no work to the obvious difference between the words DOWN and IN. Furthermore, they submit that the dispositive emphasis on sound is inapt, because the evidence of oral use was one phone call, and accordingly, greater weight ought to have been given to visual dissimilarities.

86 We do not accept this submission. The primary judge did not place undue or dispositive weight on the aural use of the mark and neglect visual differences. Her Honour considered visual similarities and differences (see [100], [101] and [111]) and the idea or meaning of the mark (see [110]) as well as aural similarities and differences. Here, the appellants urge this court to review and overturn the primary judge’s findings on the basis that her Honour failed to give sufficient regard to the aural distinction between “down” and “in”. This was considered by her Honour by reference, inter alia, to authorities relied upon by the appellants where courts have given more weight to the first part of a word mark, including because of findings that English speakers tend to slur the endings of words (at [103] – [106]). Her Honour did not find those authorities persuasive, and found, as a matter of fact that the “in” in IN-N-OUT is unlikely to attract any greater aural emphasis than “out” (at [108]). In her summary of conclusions at [155] her Honour specifically referred to both the visual and aural effect of the DOWN-N-OUT mark.

87 That view was plainly open to her Honour. Phonetically “in” is a relatively weak, nasal sound. The “n” sound is repeated: “IN-N-OUT” which phonetically gives emphasis to “out” at the conclusion of the phrase. Visually, “out” at the end of the phrase is in relative terms prominent, the earlier letters and hyphens tending to run together. We see no occasion to displace her Honour’s reasoning.

88 The appellants next contend that the primary judge erred by framing the real question on deceptive similarity as being whether people with imperfect recollections of the INO trade marks might be confused or deceived when coming across the appellants’ marks. As we have noted, a key difference between marks that are substantially identical and those that are deceptively similar within s 120 of the Trade Marks Act concerns the means by which the comparison is conducted. Determination of deceptive similarity requires consideration of the memory carried away by a consumer whose attention has been drawn to the registered mark (Jafferjee at 121 and 126). Whether that is couched in terms of “imperfect recollection” or by reference to language of “impression”, it steadily remains necessary for the comparison between the marks to involve an evaluation of the corrosive effect of memory caused by not having, for the purpose of the notional comparison, the two marks side by side. The primary judge did not err by bearing in mind that the assessment of matters of visual impression (at [88], [100], [111] and [153]), meaning or idea (at [110], [111], [154] and [155]) must be considered by having regard to the recollection, which may be imperfect, that a consumer is likely to take away of the respective marks.

89 The appellants next contend that the primary judge erred by placing apparent weight on evidence of confusion from social media posts and no weight on the absence of evidence of actual confusion. However, at [115] the primary judge noted that, in the absence of evidence of the context to the social media posts and without being able to identify the people who posted the remarks, it was difficult to put a great deal of weight on the evidence, and that even if the posts did represent genuine instances of confusion, having regard to the total number of posts and the period in which the appellants’ marks have been in use, they were “few and far between”. In later noting that the evidence of the social media posts “does have some probative value” her Honour chose not to ignore the posts entirely, but it is apparent that, rightly in our view, the evidence did not play a significant role in the evaluation. That little probative weight was placed on this evidence is apparent from the context of her Honour’s citation, in the immediately preceding paragraphs, of Parker-Knoll Ltd v Knoll International Ltd [1962] RPC 265 at 291 in a passage cited with approval by the Privy Council in Colgate-Palmolive at 665, where Lord Devlin said:

…Instances of actual deception may be useful as examples, and evidence of persons experienced in the ways of purchasers of a particular class of goods will assist the judge. But his (sic) decision does not depend solely or even primarily on the evaluation of such evidence. The court must in the end trust to its own perception into the mind of the reasonable man…

(emphasis added)

90 The primary judge’s conclusion in the first sentence of [155] (set out at [57] above) reflects that approach. Her Honour did not supplant her own view for the proffered evidence of confusion, but noted that the evidence “suggests” support for her view, and no more. The view, independently reached, that some people with an imperfect recollection of the INO trade marks might indeed be caused to wonder was, in our respectful view, correct.

91 Accordingly, ground 1 of the appeal must be rejected.

3.3.1 The appellants’ submissions

92 In their second ground of appeal, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in finding at [136] – [138] that Messrs Kagan and Saliba adopted each of the DOWN-N-OUT marks for the deliberate purpose of appropriating INO Burgers’ trade marks, branding or reputation and failing to find that they were motivated by lawful inspiration and not unlawful appropriation and, in so doing, erred in her application of Australian Woollen Mills.

93 In their submissions, the appellants extended their criticism somewhat. They contend that the primary judge erred in her assessment of intention at [123] – [151], and misunderstood the relevance of the media release (see [15] above), which, they submit, was a central item of evidence going to intention. They submit that the second sentence of [133] contains a very unclear reference to a “presumption” that the appellants “intended at least to cause confusion” which involved an error in the application of the principles of Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; 101 CLR 298 and Australian Woollen Mills which, the appellants contend, do not create either a presumption to be rebutted or an inference to be dispelled. They further submit that the primary judge’s reasons at [134] creates further uncertainty as to the primary judge’s approach in her statement that “but for two pieces of evidence” she would not have been disposed to conclude that Messrs Kagan and Saliba were being dishonest in their decision to appropriate aspects of the INO trade marks. That, they submit, sits uneasily and unexplained with the inferences already drawn and conclusions reached in [132] and [133]. The two pieces of evidence concern first, the response given by Mr Kagan to the cease and desist letter from INO Burgers (see [24] above); and secondly, the findings of the primary judge concerning the appellants’ failure to give proper discovery. The appellants submit that the primary judge’s findings in relation to the first ought not to have been made and that the second ought never to have featured because, whatever the failure of discovery on behalf of the appellants, it was incapable of proving the state of mind of the individual appellants at the time when DOWN-N-OUT was launched in 2016.

94 It is necessary to understand the structure of the primary judge’s reasons to appreciate that her Honour considered first, whether or not Messrs Kagan and Saliba intended to cause confusion and secondly, whether they were being dishonest in their decision to appropriate aspects of the INO trade marks.

95 At [123] – [133] the primary judge considered whether or not they had an intention to cause confusion. She recited the battle lines between the parties at [123]: INO Burgers contending that DOWN-N-OUT was selected deliberately to obtain the benefit of market recognition of the IN-N-OUT name and branding; and the appellants contending that they were merely inspired by INO Burgers.

96 The paragraphs that follow must then be understood by reference to her Honour’s earlier recitation of the history of the development of the DOWN-N-OUT trade mark and logo, as well as the matters accepted by the appellants at trial, which we have set out in sections 2.1 and 2.2 above. At [124] the primary judge made a finding of fact that it was “no coincidence” that Messrs Kagan and Saliba settled on the name DOWN-N-OUT and that it was indeed selected with full knowledge of the INO trade marks. That finding was amply supported by at least the following matters, all of which the primary judge referred to in the reasoning that follows:

(a) The concession that INO Burgers inspired the name DOWN-N-OUT (see [47] above);

(b) The acceptance that the “N-out” component was a direct lift from IN-N-OUT (primary judgment at [130]) (see [48] above);

(c) Messrs Kagan and Saliba’s knowledge of the “legendary” INO Burgers and Mr Kagan’s attendance at the January 2016 INO Burgers pop-up event (primary judgment at [125]);

(d) The provision to Mr Paine of the INO logo with a request to make a design like it (primary judgment at [125]) with its subsequent choice of font, colour and yellow arrow all “plainly designed” to reflect INO Burgers’ branding (primary judgment at [130]) (see [10] above);

(e) The use in the May 2016 media release of IN-N-OUT, not DOWN-N-OUT, in its title, and the references to “secret menu hacks” such as “Animal Style” and “Protein Style”, themselves trade marks owned by INO Burgers (primary judgment at [126]) (see [15] above);

(f) The endorsement by Messrs Kagan and Saliba of another designer’s announcement that Tablou was “teaming up” with the appellants to “bring IN-N-OUT down under” (primary judgment at [127]) (see [16] – [18] above); and

(g) The adoption by the appellants of the IN-N-OUT broad theme and style, including, but not limited to, marketing a “secret menu” referring to additional trade marks owned by INO Burgers (primary judgment at [128]) (see [9] – [22] above).

97 None of these findings of fact are challenged on appeal. Nor, having regard to the correspondence quoted, could they be. It was these findings that formed the evidentiary basis for the primary judge’s findings at [132] that warrant repetition:

132 The respondents submitted that the applicant’s evidence did not rise high enough to enable such an inference to be drawn or to warrant an explanation from the respondents. I disagree. The inference is open from the evidence tendered by the applicant that the respondents adopted aspects of the applicant’s registered marks in order to capitalise on its reputation. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, that is the inference that should be drawn. If this were not their intention, why choose DOWN-N-OUT? Why not stick with FUNK-N-BURGERS? In these circumstances, the choice of DOWN-N-OUT should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to confuse, if not deceive, consumers.

98 The inference that DOWN-N-OUT was chosen by Messrs Kagan and Saliba for the purpose of causing confusion to consumers was based on the evidence available to the primary judge. Her Honour then noted at [133] that the media release emphasises that the DOWN-N-OUT pop-up was “Sydney’s Answer to In-N-Out Burgers”. From this, the appellants submitted, it cannot be inferred that the appellants had an intention to trade off the reputation of INO Burgers. The primary judge rejected that proposition saying:

...On balance, however, in the absence of evidence from Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, the representations in the media release are not sufficient to dispel the inference or rebut the presumption that they intended at least to cause confusion.