Federal Court of Australia

Registered Organisations Commissioner v Australian Workers’ Union [2020] FCAFC 202

ORDERS

REGISTERED ORGANISATIONS COMMISSIONER Appellant | ||

AND: | First Respondent COMMISSIONER OF THE AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL POLICE Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to agreeing on a form of orders appropriate to give effect to the Court’s reasons.

2. Any minute of orders so agreed be provided to the Court within seven days.

3. In the event that the parties are not able within seven days to provide to the Court a minute of order reflecting these reasons:

(a) The appellant file and serve within a further seven days draft minutes of order containing the orders he seeks and written submissions of no more than three pages in support of such orders;

(b) The first respondent file and serve within a further seven days written submissions of no more than three pages in response to the appellant’s draft minutes of order and written submissions; and

(c) Subject to any further order, the Court will determine the orders to be made on the basis of the written submissions.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ALLSOP CJ:

1 I have read the reasons of Besanko J to be published. I agree with them and with the orders proposed by his Honour.

I certify that the preceding one (1) numbered paragraph is a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Chief Justice Allsop. |

Associate:

Dated: 20 November 2020

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BESANKO J:

Introduction

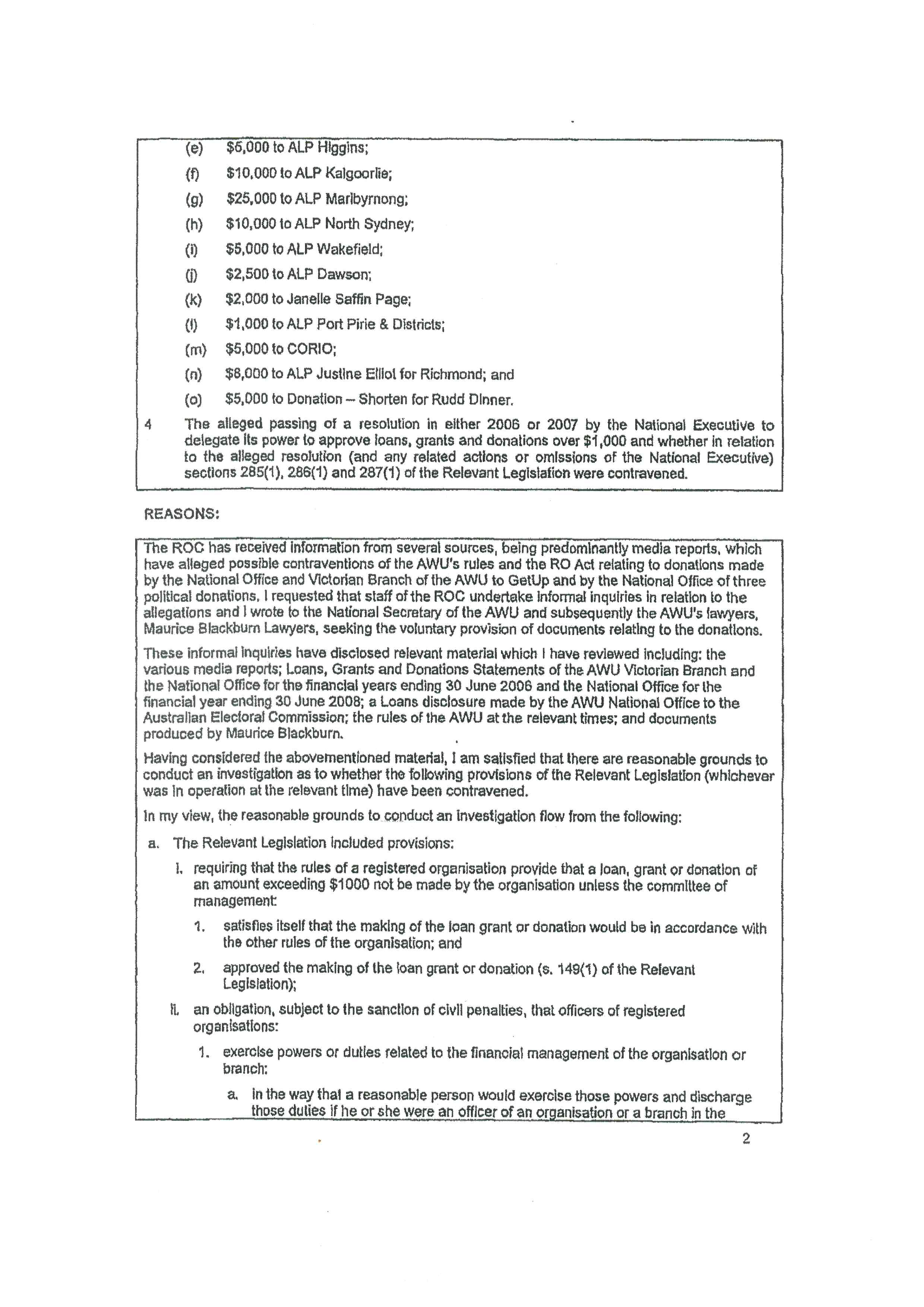

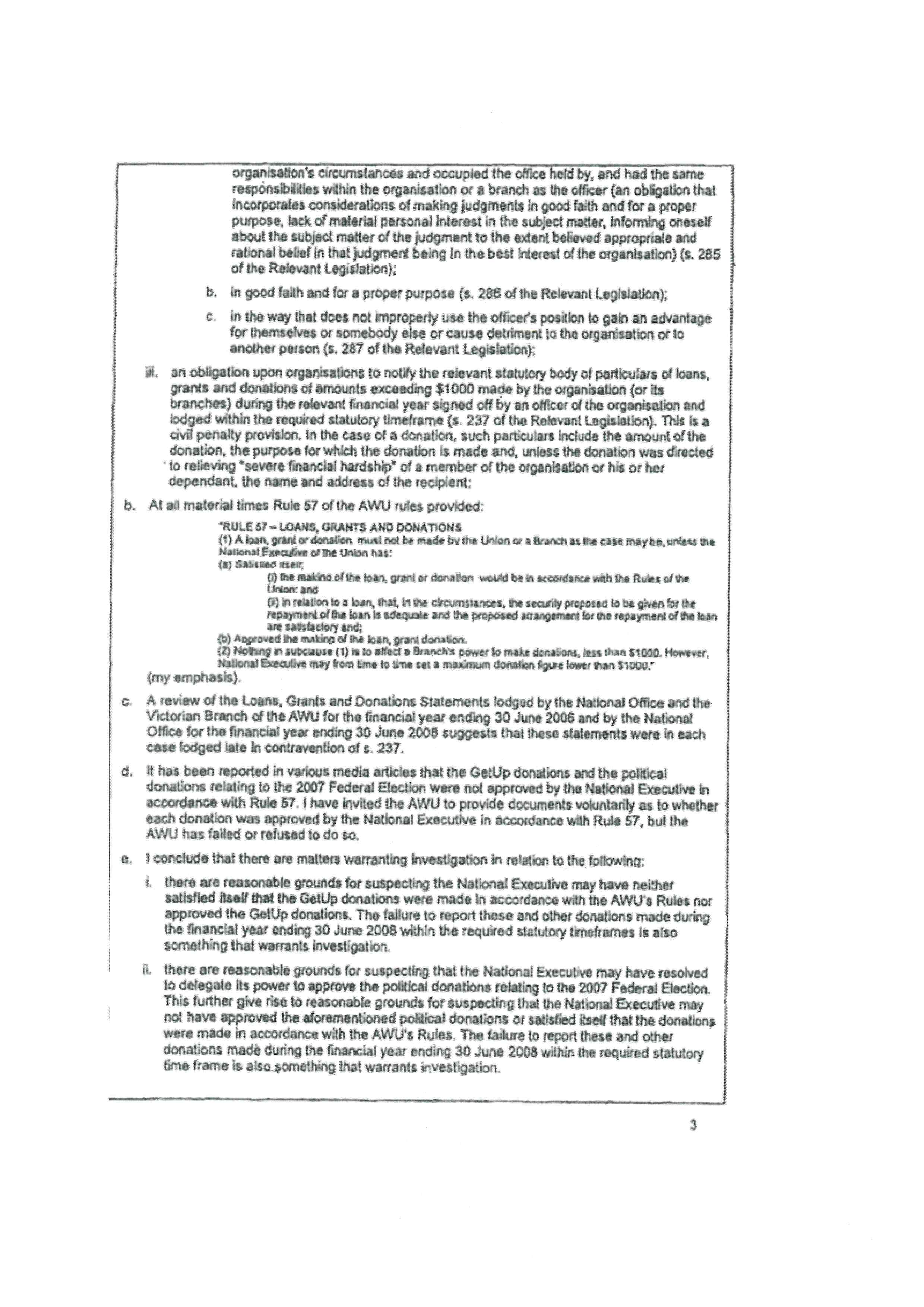

2 This is an appeal from orders made by a judge of this Court on 19 November 2019. The Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) is a registered organisation under the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) (the RO Act) and it brought an application for judicial review of a decision made by the Registered Organisations Commissioner (the Commissioner) by his delegate under s 331(2) of the RO Act to conduct an investigation as to whether civil penalty provisions had been contravened. Stating the matter broadly at this stage, the investigation was said to relate to an alleged donation by the National Office of the AWU to GetUp Limited (GetUp), an alleged donation by the Victorian Branch of the AWU to GetUp, 15 alleged donations by the National Office of the AWU to entities associated with the Australian Labour Party, and the alleged passing of a resolution in either 2006 or 2007 by the National Executive of the AWU to delegate its power to approve loans, grants and donations exceeding $1,000. The alleged donations were said to have been made in the financial years ending 30 June 2006 and 30 June 2008 respectively. The civil penalty provisions of the RO Act which were said to be relevant were s 237(1) which deals with the obligation on organisations to lodge with the Commissioner particulars of loans, grants or donations exceeding $1,000 made by them, and ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) which set out various duties of officers of organisations.

3 The AWU’s case before the primary judge was that the decision of the Commissioner by his delegate to conduct an investigation under s 331(2) (the Investigation) was invalid because it involved jurisdictional error. The AWU advanced five grounds of judicial review in support of its case before the primary judge. For introductory purposes, these grounds may be summarised as follows. First, the AWU alleged that the Commissioner did not have the power to investigate “historical conduct”, that is to say, conduct which had occurred prior to 1 May 2017. The significance of this date will be identified later in these reasons. Secondly, the AWU alleged that the Commissioner was not validly satisfied that there were reasonable grounds for conducting the Investigation. The third, fourth and fifth grounds are conveniently dealt with together and are to the effect that the decision to conduct the investigation was invalid by reason of the fact that the Commissioner had an improper political purpose or took into account an irrelevant consideration or was the subject of an impermissible direction from the responsible Minister under the RO Act.

4 The second ground of judicial review contained two limbs and the primary judge upheld the first limb in that he held that the Commissioner was not validly satisfied under s 331(2) that there were reasonable grounds for conducting an investigation of possible contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) of the RO Act. He rejected the ground insofar as it related to possible contraventions of s 237(1). The primary judge rejected the other four grounds of judicial review advanced by the AWU (Australian Workers’ Union v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 9) [2019] FCA 1671; (2019) 168 ALD 48 (the substantive reasons)). The primary judge’s rejection of the second ground of judicial review insofar as it related to possible contraventions of s 237(1) of the RO Act raised an issue as to whether the Commissioner, through his delegate, had made a decision which was partly valid and partly invalid. The primary judge dealt with this issue in a further set of reasons (Australian Workers’ Union v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 10) [2019] FCA 2004). In those reasons, he recorded the fact that he was informed by the parties that they had conferred and that, based upon the conclusions expressed in the substantive reasons, the parties proposed that a declaration be made that the decision of the Commissioner by his delegate be declared to be invalid. The orders which the primary judge made and which, with the exception of the order in paragraph 5, are the subject of the Commissioner’s appeal are as follows:

1. The decision of the first respondent by his delegate Mr Chris Enright made on 20 October 2017 to commence investigation INV2017/30 into the applicant (“Decision”), is invalid.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The Decision of the first respondent, by his delegate Mr Chris Enright, is quashed.

3. The second respondent (by himself or by his servants or agents) return to the applicant the documents seized pursuant to the warrants issued by Magistrate Reynolds on 24 October 2017 pursuant to s 335L of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth).

4. The execution of order 3 is stayed pending the hearing and determination of any appeal of these orders.

5. There be no order as to costs.

5 By his appeal, the Commissioner contends that the primary judge erred in upholding the AWU’s second ground of judicial review. There are nine grounds of appeal and in these grounds, the Commissioner challenges the primary judge’s final conclusions as well as important intermediate findings made by his Honour.

6 The AWU has filed a Notice of contention in which it seeks to have the primary judge’s orders upheld on grounds other than those relied on by him. There are four grounds in the Notice of contention. In grounds 1 and 3, the AWU seeks to have this Court uphold the second ground of judicial review on grounds other than those relied on by the primary judge. In ground 2, the AWU seeks to have this Court uphold the first ground of judicial review by reference to one of the arguments put to the primary judge and rejected by him. In ground 4, the AWU seeks to have this Court uphold a slightly reformulated version of the fifth ground of judicial review. There is no challenge in this Court to the primary judge’s rejection of the third and fourth grounds of judicial review.

7 There is an aspect of the case as it was conducted in the Court below which was not directly in issue on the appeal or by reason of the Notice of contention, but which should be noted. It concerns the Commissioner’s decision subsequent to his decision to conduct an investigation, to apply for the issue of certain search warrants and the execution of those warrants.

8 The primary judge described the events which were relevant to this aspect of the case in the following terms (at [8]):

8 On 24 October 2017, upon the application of the Commissioner under s 335K of the RO Act, a magistrate issued a warrant authorising officers of the second respondent (“AFP”) to search the premises of the National Office of the AWU in Sydney, and a warrant authorising officers of the AFP to search the premises of the Victorian Branch of the AWU in Melbourne (collectively “search warrants”). Later that day, officers of the AFP accompanied by representatives of the Commissioner executed the search warrants at each of the National and Victorian Branch offices of the AWU. In the execution of the search warrants, the AFP took possession of various documents.

9 The Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police was a respondent to the proceedings in the Court below. However, he did not participate in the trial. He sought leave to be excused from the trial and that leave was granted. He filed a submitting appearance in the appeal.

10 The AWU’s grounds of judicial review relevant to the search warrants were as follows:

Ground 6 - That the warrants are invalid because there was no valid investigation and thus no power to obtain a warrant under s 335K of the RO Act;

Ground 7 - That the warrants are invalid because there was no power for the Commissioner to apply for them in connection with the conduct under investigation (which allegedly occurred before 1 May 2017)

11 The primary judge dealt with these grounds in the following way. With respect to ground 6, his Honour said that the AWU’s essential point was that the existence of a valid investigation was an essential pre-requisite for the validity of the search warrants. The contention of the AWU was that as there was no valid investigation on foot, the Commissioner was not authorised under s 335K of the RO Act to apply to a magistrate for the search warrants to be issued and, in those circumstances, the warrants were invalid. His Honour went on to point out that in his view there were a number of difficulties with the relief sought by the AWU in relation to the search warrants having regard to the way in which the proceedings were constituted (at [387]–[390]). With respect to ground 7, the primary judge noted that the AWU pressed this ground in the alternative and on the basis that the decision to conduct the investigation was valid. His Honour noted that the ground was based on the proposition that in the conduct of an investigation as to whether civil penalty provisions had been contravened by historical conduct, the Commissioner was only permitted to exercise powers that were, or would have been, available to the General Manager in the course of such an investigation and such powers did not extend to a power to apply for search warrants to be issued. The primary judge noted that he had already rejected that premise in dealing with the first ground of judicial review, and, in the circumstances, he did not need to deal further with ground 7.

12 In my opinion, this appeal should be allowed. The declaration made by the primary judge and the order quashing the decision under s 331(2) of the RO Act should be set aside. If there are any issues concerning the search warrants and their execution which need to be addressed as a result of these reasons, then such matters can be raised at the time final orders are made.

Background

13 There is no dispute about the relevant background and the following summary is taken from the primary judge’s reasons.

14 The RO Act provides for the registration as organisations of associations of employers and associations of employees. Section 5 of the RO Act describes Parliament’s intention in enacting the Act and the section includes a statement to the effect that the standards set out in the Act “encourage the efficient management of organisations and high standards of accountability of organisations to their members” (s 5(3)(c)). The RO Act deals with a range of matters relevant to registered organisations, including the registration of associations and the cancellation of registration, the amalgamation of organisations and the withdrawal from amalgamation, the rules of organisations, the membership of organisations, the records which must be kept by organisations and the obligations in relation to their financial affairs, the conduct of officers and employees of organisations and branches of organisations, and civil penalties when certain provisions of the RO Act are contravened.

15 Part 3A of Chapter 11 of the RO Act deals with the Commissioner and the Registered Organisations Commission (the Commission), including their establishment, powers and functions. Section 329AA in Part 3A provides for the establishment of the Commissioner and s 329DA provides for the establishment of the Commission. Section 329DC provides that the Commission’s function is to assist the Commissioner in the performance of the Commissioner’s functions.

16 Part 4 deals with the Commissioner’s powers to conduct inquiries and investigations, as the case may be, and includes s 331. The key subsection in this case is s 331(2) and it is in the following terms:

(2) If the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so, the Commissioner may conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision (see section 305) has been contravened.

17 Except where otherwise indicated, a reference in these reasons to the RO Act is a reference to the Act as it was when the decision in issue in this appeal was made in October 2017.

18 At all times relevant to the matters raised in this proceeding, the Minister with oversight responsibility for the Commission was Senator the Honourable Michaelia Cash, the Minister for Employment (the Minister).

19 On 20 October 2017, Mr Chris Enright, who is the Executive Director of the Commission and a delegate of the Commissioner, decided to conduct an investigation which he described in a document he prepared, or caused to be prepared, titled “Case Decision Record” (the Decision Record) as “an investigation under section 331(2) of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (the RO Act) in relation to the National Office and Victorian Branch of the Australian Workers’ Union (AWU) as to whether various civil penalty provisions within the meaning of section 305 have been contravened”. The Decision Record describes the Investigation as one that “relates to the following matters”. The first matter is a donation of $50,000 from the National Office of the AWU to GetUp during the financial year ending 30 June 2006 and whether that donation was properly approved under Rule 57 of the AWU’s Rules (the Rules) at the relevant time. The second matter is a donation of $50,000 from the Victorian Branch of the AWU to GetUp during the financial year ending 30 June 2006 and whether that donation was properly approved under Rule 57 of the AWU’s Rules at the relevant time. The third matter is 15 other donations made by the National Office of the AWU to persons or entities associated with the Australian Labour Party during the financial year ending 30 June 2008 and whether those donations (and each of them) were properly approved under Rule 57 of the AWU’s Rules at the relevant time. In the case of each of these matters, the possible contraventions of civil penalty provisions included whether in relation to the donation (and its reporting), ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) in Sch 1B of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) (WR Act) between 12 May 2003 and 27 March 2006, and in Sch 1 of the same Act between 27 March 2006 and 30 June 2009 had been contravened. The fourth matter is a resolution allegedly passed by the National Executive in either 2006 or 2007 to delegate its power to approve loans, grants or donations of an amount exceeding $1,000. In the case of this matter, the possible contraventions of civil penalty provisions were identified as ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1).

20 At the time of the possible contraventions, ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) were in the following terms:

237 Organisations to notify particulars of loans, grants and donations

(1) An organisation must, within 90 days after the end of each financial year (or such longer period as the Registrar allows), lodge in the Industrial Registry a statement showing the relevant particulars in relation to each loan, grant or donation of an amount exceeding $1,000 made by the organisation during the financial year.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

…

285 Care and diligence—civil obligation only

(1) An officer of an organisation or a branch must exercise his or her powers and discharge his or her duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if he or she:

(a) were an officer of an organisation or a branch in the organisation’s circumstances; and

(b) occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within the organisation or a branch as, the officer.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

...

286 Good faith—civil obligations

(1) An officer of an organisation or a branch must exercise his or her powers and discharge his or her duties:

(a) in good faith in what he or she believes to be the best interests of the organisation; and

(b) for a proper purpose.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

...

287 Use of position—civil obligations

(1) An officer or employee of an organisation or a branch must not improperly use his or her position to:

(a) gain an advantage for himself or herself or someone else; or

(b) cause detriment to the organisation or to another person.

Note: This subsection is a civil penalty provision (see section 305).

21 A copy of the Decision Record is an appendix to these reasons.

22 Section 140 of the RO Act provides that an organisation must have rules that make provision as required by the Act. Section 149 addresses the rules which an organisation must have with respect to conditions for making of loans, grants and donations by the organisation. Section 149(1) is in the following terms:

Rules to provide conditions for loans, grants and donations by organisations

(1) The rules of an organisation must provide that a loan, grant or donation of an amount exceeding $1,000 must not be made by the organisation unless the committee of management:

(a) has satisfied itself:

(i) that the making of the loan, grant or donation would be in accordance with the other rules of the organisation; and

(ii) in the case of a loan – that, in the circumstances, the security proposed to be given for the repayment of the loan is adequate and the proposed arrangements for the repayment of the loan are satisfactory; and

(b) has approved the making of the loan, grant or donation.

23 At the time the donations were made, s 149(1) of Sch 1 of the WR Act was to the same effect.

24 The AWU’s Rules at the time the donations were made included Rule 57 which was in the following terms:

(1) A loan, grant or donation, must not be made by the Union or any Branch as the case may be, unless the National Executive of the Union has:

(a) Satisfied itself:

(i) that the making of the loan, grant or donation, would be in accordance with the Rules of the Union; and

(ii) in relation to a loan, that, in the circumstances, the security proposed to be given for the repayment of the loan is adequate and the proposed arrangements for the repayment of the loan are satisfactory; and

(b) Approved the making of the loan, grant or donation.

(2) Nothing in sub-clause (1) is to affect a Branch’s power to make donations, less than $1,000. However, National Executive may from time to time set a maximum donation figure lower than $1,000.

25 Mr Enright’s consideration of the matter under s 331(2) of the RO Act extended over a period of just over two months. The starting point was two articles published in the Weekend Australian on 12 August 2017, one titled “Shorten’s AWU donated $100,000 to [GetUp]” and the other titled “Union and ALP links test [GetUp] ‘independence’”. On 14 August 2017, Mr Enright asked his staff to commence inquiries and to locate documents that might assist in addressing the allegations in the articles. Later on the same day, Senator the Honourable Eric Abetz wrote to the Commissioner referring to reports in the Australian on 12 August 2017 in relation to a sum of funds provided by the AWU to GetUp and saying, “If these reports are correct, it would appear that this donation may have been in violation of the Union’s own rules and does not appear to have been included in its financial disclosures …”.

26 Further articles appeared in the Australian newspaper as follows:

(1) Article titled “Thomson case provides ammo for Shorten attack” published on 15 August 2017;

(2) Article titled “Probe for Shorten over AWU’s [GetUp] donation” published on 16 August 2017;

(3) Article titled “Shorten donated AWU funds to his political campaign” published on 17 August 2017; and

(4) Article titled “‘Unaccountably shifty’: Bill flayed” published on 18 August 2017.

27 The Minister sent two referral letters to the Commissioner dated 15 August 2017 and 17 August 2017 respectively. These referral letters and Mr Enright’s responses to them are considered in detail in connection with ground 4 in the Notice of contention.

28 Mr Enright communicated with the AWU (Mr Walton) and then with its solicitors, Maurice Blackburn. Some information was provided by the AWU in respect of the reporting of the donation of $50,000 by the National Office of the AWU to GetUp and the donation of $50,000 by the Victorian Branch of the AWU to GetUp. A stalemate soon developed with Mr Enright seeking all documents showing the AWU’s approval of various donations and the AWU, through its solicitors, seeking all documents disclosing communications between Mr Enright and his office on the one hand, and the Minister and her office on the other.

29 The AWU called a number of witnesses at the trial. In each case, the witness attended in response to a subpoena issued by the AWU. Mr Enright was called by the AWU and, in the course of his evidence, and with the leave of the Court granted under s 38 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), counsel for the AWU was able to question Mr Enright as though the AWU was cross-examining Mr Enright about aspects of his evidence. The Commissioner did not call any witnesses. The primary judge recorded the fact that, in addition to the oral evidence, a large number of documents were tendered at the trial.

The Commissioner’s Appeal and Grounds 1 and 3 IN the AWU’s Notice of Contention

30 The second ground of the AWU’s application for judicial review was in the following terms:

That the Commissioner’s decision to conduct the Investigation under s 331(2) of the RO Act was affected by jurisdictional error, because:

(i) it was not open to the Commissioner to be satisfied that there were “reasonable grounds” to conduct an investigation for breach of the AWU’s rules, due to the operation of s 320 of the RO Act;

(ii) further or alternatively, in not adverting to s 320 of the RO Act, the Commissioner misunderstood the law he was to apply.

As I have said, the primary judge upheld the first limb of this ground. He rejected the second limb.

31 Section 320, which is referred to in both limbs of the second ground, is in the following terms:

Validation of certain acts after 4 years

(1) Subject to this section and section 321, after the end of 4 years from:

(a) the doing of an act:

(i) by, or by persons purporting to act as, a collective body of an organisation or branch of an organisation and purporting to exercise power conferred by or under the rules of the organisation or branch; or

(ii) by a person holding or purporting to hold an office or position in an organisation or branch and purporting to exercise power conferred by or under the rules of the organisation or branch; or

(b) the election or purported election, or the appointment or purported appointment of a person, to an office or position in an organisation or branch; or

(c) the making or purported making, or the alteration or purported alteration, of a rule of an organisation or branch;

the act, election or purported election, appointment or purported appointment, or the making or purported making or alteration or purported alteration of the rule, is taken to have been done in compliance with the rules of the organisation or branch.

(2) The operation of this section does not affect the validity or operation of an order, judgment, decree, declaration, direction, verdict, sentence, decision or similar judicial act of the Federal Court or any other court made before the end of the 4 years referred to in subsection (1).

At the time the donations were made, s 89 of Sch 1 of the WR Act was in similar terms.

The Primary Judge’s Reasons

32 The primary judge summarised the AWU’s argument in support of the first limb of the second ground of judicial review in the following way. Mr Enright’s decision was affected by jurisdictional error because it was not open to him to be satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to conduct the investigation. The only ground relied upon by Mr Enright to reach a state of satisfaction that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened was that the making of the donations involved suspected non-compliance with the Rules and, in particular, Rule 57. The AWU submitted that this approach was misconceived because the operation and effect of s 320 of the RO Act was such that the making of the donations was “taken to have been done in compliance with the Rules” at the end of the four year period after each of the donations were made (at [85]). The AWU submitted that in those circumstances, there is no possibility of non-compliance with the Rules in relation to the making of the donations and it was not open to Mr Enright to reach the state of satisfaction required by s 331(2). It followed that his decision was affected by jurisdictional error and invalid.

33 The primary judge noted that the AWU’s submission did not extend to the conduct of an investigation into whether s 237(1) had been contravened because that aspect of the Investigation had nothing to do with a suspected contravention of the Rules. The relevant failure was a failure to comply with an obligation imposed by the RO Act itself.

34 The primary judge then discussed the general principles concerning the Court’s power, on an application for judicial review, to review the exercise of a power of the nature set out in s 331(2). There was no dispute before this Court about his Honour’s statement of the general principles and, to the extent necessary, the principles are referred to later in these reasons.

35 His Honour said that if reasons are given by a decision-maker which explain the basis for the decision-maker reaching a requisite state of satisfaction or opinion, it is to those reasons that a supervising court should look to understand how the state of satisfaction or opinion was reached. His Honour said (at [94]):

That is the approach taken by a supervising court in the related field of legal unreasonableness. I can see no reason why the same approach is not apposite.

36 I should say something at this point about the evidence of Mr Enright’s reasons for the decision he made. The primary judge focussed on the Decision Record as did the parties both before the primary judge and on appeal. However, as counsel for the AWU put it in the course of oral submissions, there was no statutory obligation on Mr Enright to give reasons and the identification of his actual reasons is a question of fact. As it happened, Mr Enright gave oral evidence extending over nearly two days primarily directed (so far as I can see) to the improper political purpose ground and related grounds (i.e., the third, fourth and fifth grounds of the application for judicial review). Nevertheless, he gave some evidence relevant to the second ground and both the primary judge and the parties referred to and relied on aspects of this evidence.

37 The primary judge’s approach was to set out his conclusions and then explain his reasons for those conclusions. He said that he had reached the view that the only circumstance or ground relied upon by Mr Enright to form the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) of the RO Act had been contravened was that there was a basis for suspecting that each of those provisions had been contravened, and further, that Mr Enright’s only basis for the suspicion that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened was that the donations were not made in accordance with the Rules. His Honour said that he reached that conclusion “looking to the reasons given by Mr Enright for the Decision” (at [96]).

38 His Honour said that it was open to Mr Enright to be satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether s 237(1) “has been contravened” and the conduct of the Investigation for that purpose was not invalid because the requisite state of satisfaction did not exist (at [97]).

39 The primary judge said that he reached the opposite conclusion in relation to the conduct of an investigation for the purpose of investigating whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened. His Honour concluded that the delegate’s suspicion that various acts had occurred in contravention of those sections was predicated upon the view that those acts, if done, were done in breach of the Rules and that, in each case, the breach of the Rules was the basis for the suspected contravention. His Honour said (at [98]):

… It was for that reason that Mr Enright formed the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether those provisions had been contravened.

40 His Honour said that the basis relied upon by Mr Enright to ground his suspicion could not sustain the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether those provisions had been contravened. He said that there was no basis for Mr Enright’s opinion that the suspected contraventions would be grounded in acts done in contravention of the Rules because, by the operation of s 320 of the RO Act, the suspected acts in question, if done, must be “taken to have been done in compliance with the [Rules]”. His Honour said that, in those circumstances, the matters relied upon by Mr Enright to form his opinion, were insufficient to induce a reasonable person to form the opinion that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened (at [100]). His Honour then turned to provide his reasons for reaching those conclusions.

41 There are eight key conclusions in his Honour’s reasoning and, in my opinion, it will assist in understanding the primary judge’s reasons, and the submissions on the appeal and with respect to the Notice of contention, if I organise my description of his Honour’s reasons by reference to those eight key conclusions.

42 The first key conclusion is a finding by the primary judge that Mr Enright’s state of mind in deciding to conduct the Investigation was a suspicion that ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened.

43 The primary judge said that Mr Enright “unquestionably” held a state of mind about whether ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened and relied upon that state of mind in forming the opinion that he did under s 331(2) (at [114], [121], [123], [128], [133], [137] and [147]). He considered that having regard to the Decision Record that state of mind was the only ground relied upon by Mr Enright in being satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to commence an investigation into whether each of ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened (at [114]).

44 The second key conclusion is a holding by the primary judge that the state of mind necessary for the Commissioner “to proceed reasonably” under s 331(2) is “at least a reasonable suspicion of a contravention” (at [113]). Although his Honour said that he did not need to determine the state of mind required by s 331(2), in view of his first conclusion, it is clear from his reasons read as a whole that he did reach the second key conclusion (at [113] and [122]).

45 His Honour began his analysis by considering the terms of s 331 and the coercive powers which are available for the purposes of an investigation. He then contrasted those matters with the powers available to the Commissioner in conducting inquiries under s 330 (at [102]–[109]). His Honour considered that the matters he identified were to be kept in mind when assessing whether a particular investigation has been commenced within the boundaries of the power conferred by s 331(2). I will address those matters later in these reasons.

46 The primary judge then summarised the competing submissions of the parties as to the necessary state of mind of the decision-maker before the power in s 331(2) to conduct an investigation is exercised. The AWU’s submission was that there will be reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation under s 331(2) if there are sufficient facts to satisfy a person that: (1) there are reasonable grounds to believe that a civil penalty provision may have been contravened; and (2) there are reasonable grounds to believe that the investigation will assist the Commissioner to establish that a civil penalty provision has been contravened.

47 By contrast, the Commissioner’s submission was that the decision-maker was not required to have a state of mind about whether a civil penalty provision “had been contravened”. He submitted that the only question to be answered in the formulation of the requisite opinion was “whether it was reasonable to investigate whether a civil penalty provision had been contravened” or “was it reasonable to think it appropriate to investigate” whether a civil penalty provision had been contravened.

48 His Honour considered that the Commissioner’s formulations merely restated the criterion in non-statutory language and did not identify the content of the criterion, that is, the considerations that needed to be taken into account. He described the Commissioner’s submissions as to content as involving identification of only those matters which were said not to be necessary. His Honour said that the considerations which were said not to be necessary or relevant, were “unhelpfully” supported by the Commissioner’s submissions by reference to authorities dealing with s 155 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), such as Melbourne Home of Ford Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (No 3) (1980) 31 ALR 519; (1980) 47 FLR 163 (Melbourne Home of Ford) at 173; Emirates v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2009] FCA 312; (2009) 255 ALR 35 at [103]; Singapore Airlines Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2009] FCAFC 136; (2009) 260 ALR 244 at [37]. His Honour said that these cases dealt with a different legislative provision with “insufficient equivalence” to s 331(2) (at [112]).

49 The primary judge said that the requirement of “at least a reasonable suspicion of a contravention” was implicit in the text, context and purpose of the limitation on the exercise of the power in s 331(2) i.e., reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation (at [113]).

50 The third key conclusion is that the primary judge construed Mr Enright’s “reasonable grounds” for the purposes of s 331(2) as being based solely on the alleged contraventions of the Rules of the AWU (at [96], [98], [137], [138], [146], [147] and [323]). He found that there were no other matters beyond the contraventions of the Rules which formed the basis of Mr Enright’s suspicion of contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1).

51 As part of determining whether Mr Enright had “proceeded reasonably” for the purposes of s 331(2), his Honour identified and then considered the “reasonable grounds” relied on by Mr Enright.

52 His Honour found that Mr Enright’s reasonable grounds were contained in the Decision Record. He relied on the following evidence to make that finding. First, he noted that although there was no statutory obligation upon the Commissioner or his delegate to provide reasons for a decision, including a decision to conduct an investigation under s 331, Mr Enright’s practice within the established processes of the Commission was to create a decision record in relation to any “significant” decision. Mr Enright regarded the decision in this case as a significant decision and the purpose of a case decision record is to set out the decision and the reasons for the decision. Secondly, the primary judge noted that a number of drafts of the Decision Record were in evidence and that Mr Enright explained in his evidence the reasons for those drafts. He set out a passage from Mr Enright’s evidence to the effect that the process of drafting is to ensure that “all of the relevant reasonable grounds” are identified. Thirdly, the primary judge noted that the Commissioner often obtained legal advice, including advice about “our reasonable grounds” (at [118]). In this case, Mr Enright obtained legal advice from Mr Chris O’Grady QC. Mr O’Grady provided advice by memorandum dated 4 October 2017. Mr Enright explained in his evidence that he sought advice because he wanted senior counsel’s advice “about whether or not there were reasonable grounds to commence an investigation in this case, and whether the Commissioner’s discretion ought to be exercised to conduct the investigation” as well as to ensure that the legal bases for conducting such an investigation were properly considered. The primary judge said that it was significant that in compiling a list of matters “suggesting that there may have been a contravention of the predecessor provisions warranting investigation”, Mr O’Grady referred to matters, in relation to which, either the Honourable Bill Shorten MP (Mr Shorten) or the Branch Secretary of the Victorian Branch of the AWU at the relevant time, Mr Cesar Melhem, were specifically mentioned.

53 In his memorandum of advice, Mr O’Grady expressed the opinion that on the basis of the material in the brief sent to him, it would appear that there are reasonable grounds for being satisfied that there is a matter warranting investigation in that there are good grounds for suspecting the following matters. I will not set out all the matters to which Mr O’Grady referred. The following are the relevant matters for present purposes. In April 2005, GetUp was incorporated as a non-profit organisation. On 1 August 2005, Mr Shorten was made an inaugural director of GetUp. He resigned from that position from some time in or around 2006, but prior to him being elected to the Commonwealth Parliament. In the year ending 30 June 2006, the AWU National Office approved a donation or donations to GetUp totalling $50,000 and at that time Mr Shorten was the National Secretary of the AWU. In November 2006, the National Secretary passed a resolution authorising Mr Shorten, who at that time was the National Secretary of the AWU, to make donations at his discretion to candidates in the 2007 Federal Election. Subsequent to that authorisation, Mr Shorten donated $25,000 to his own political campaign and a further $50,000 to two other campaigns. In the year ending 30 June 2006, the AWU Victorian Branch approved a donation or donations to GetUp totalling $50,000. At the time, Mr Melham was the Branch Secretary of the Victorian Branch of the AWU (at [118]).

54 As the primary judge said, there was no reference in the Decision Record to possible circumstances attending Mr Shorten or the delegation to Mr Shorten of the capacity to make donations at his discretion to candidates in the 2007 Federal Election or that Mr Shorten donated $25,000 to his own political campaign (at [143]).

55 The primary judge, having decided that it was intended that the Decision Record set out all of the grounds regarded by Mr Enright as constituting the “reasonable grounds” to conduct the Investigation and upon which his satisfaction was based, then turned to consider what the Decision Record disclosed about the reasonable grounds. He said that having regard to the content of the Decision Record, it was apparent that there are no considerations relied upon for the state of satisfaction reached by Mr Enright, other than considerations that he perceived supported a suspicion that either ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened.

56 The primary judge said that no matters going to other considerations are raised by the Decision Record. This demonstrated, in the primary judge’s opinion, that Mr Enright construed s 331(2) as the primary judge had, recognising that his assessment of whether there were reasonable grounds had to focus upon whether there was a basis for suspecting particular contraventions of civil penalty provisions. The primary judge referred to and relied on paragraphs e i. and e ii. in the Decision Record and said that the first sentence of each sub-paragraph addresses the basis for Mr Enright’s suspicion that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) were contravened, whilst the second sentence of each sub-paragraph addresses the basis for his suspicion in relation to contraventions of s 237(1).

57 As I have already said, and as the primary judge noted, there was little doubt that it was open for Mr Enright to come to the view, by reference to the consideration he relied upon, that there was a reasonable basis for suspecting contraventions of s 237(1) and that, therefore, there were reasonable grounds for conducting an investigation as to whether s 237(1) was contravened by the AWU in the financial years ending 30 June 2006 and 30 June 2008.

58 The primary judge then turned to consider ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) and said (at [128]):

However, whether objectively considered a reasonable basis existed for Mr Enright’s suspicion that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) were contravened, is far more problematic.

59 The primary judge then referred to the terms of each of the sections and reached the view that it was at least arguable that in exercising the powers and discharging the duties of his or her office, an officer of a registered organisation may contravene ss 285(1) and 286(1) because, in so doing, the officer acted in contravention of the rules of the organisation. However, with respect to s 287(1), the primary judge said that it was not immediately apparent how a contravention of the rules of an organisation would of itself contravene s 287(1), unless the contravention of the rules of an organisation was itself the means by which an advantage was gained or a detriment caused. The primary judge recorded the fact that the AWU had not argued that an act done in contravention of the rules was not capable of “founding a ground of contravention” of s 287(1) and the primary judge said that, “for present purposes”, he would proceed on the basis that such a contravention was at least arguable (at [132]).

60 The primary judge then identified the acts which appeared to have formed the basis of Mr Enright’s suspicion that acts had occurred which may have contravened each of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1). He noted that no particular officers or employees were named in the Decision Record as being the actors in relation to any of the matters relied upon by Mr Enright. The primary judge said that with respect to the acts identified, the only concern recorded in the Decision Record about them is that they might not have been done in accordance with the Rules.

61 The result of the primary judge’s analysis was that he reached the conclusion that the basis for Mr Enright’s suspicion that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened was that the Rules had been contravened. He analysed the matter by reference to the Decision Record, although he said that his conclusion was supported by two other matters “beyond” the Decision Record (at [137]).

62 The first matter was that there was “extensive evidence of communications” either made directly by Mr Enright, or made with his approval, which reported the bases for the Investigation as the making of donations not approved in accordance with the Rules (at [137]). In that regard, his Honour referred to three findings which he made in his analysis of the third ground of judicial review (at [234], [246] and [257]). The three findings related to draft media statements, one before and two after Mr Enright made his decision, stating that the Investigation related to a breach of the Rules.

63 The second matter was that his Honour considered that Mr Enright had been selective in relation to the matters he chose to rely upon to form the opinion that he was satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened. He said that two matters referred to in Mr O’Grady’s advice were not relied upon by Mr Enright. Those matter were as follows: (1) Mr Shorten may have been a director of GetUp at the time the donations were made by the AWU. This was also a circumstance “giving good grounds for suspecting” the possible contravention of the RO Act; and (2) there were grounds for suspecting that the National Executive delegated to Mr Shorten the capacity to make donations at his discretion to candidates in the 2007 Federal Election and that Mr Shorten donated $25,000 to his own political campaign. However, neither of those matters were referred to in the Decision Record. The primary judge expressed the following conclusion (at [144]):

It is apparent then that, beyond possible contraventions of the AWU’s Rules, Mr O’Grady advised Mr Enright that there were grounds for suspicion which, broadly stated, may be characterised as giving rise to possible conflicts of interest for Mr Shorten, which could be relied upon to form the view that there were potential contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1). However, those matters were not relied upon by Mr Enright.

64 The primary judge referred to the fact that in cross-examination Mr Enright was taken to earlier drafts of the Decision Record, including drafts which were based on there being reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation specific to the conduct of Mr Shorten in relation to the making of the donations as well as the conduct of two other officials of the AWU. Mr Enright was asked why later drafts were differently cast without reference to or naming any particular individuals. Mr Enright’s evidence was that this had occurred because, consistently with his own view, the Investigation was an investigation “into a range of office holders at the AWU and no particular office holder – there were no office holders in particular”. Mr Enright said in response to a question asking him to further explain his answer that “we weren’t focusing on any office holder in particular”. The primary judge did not make a specific finding at this point as to whether or not he accepted this aspect of Mr Enright’s evidence.

65 The primary judge concluded that Mr Enright had not relied on the fact that the donations had been made by the AWU to GetUp at the time when the National Secretary (Mr Shorten) was a board member of GetUp and the fact that donations were made to Mr Shorten as an election candidate and that there may be an argument about a conflict of interest or the best interests of the AWU. The primary judge considered that in this respect the Commissioner was restricted to the matters set out in the Decision Record.

66 The fourth key conclusion is the finding by the primary judge that the hypothesis which was the subject of Mr Enright’s suspicion was based upon acts of the kind referred to in either ss 320(1)(a)(i) or 320(1)(a)(ii) of the RO Act (at [154]). His Honour carried out an analysis by reference to “the facts as likely envisaged by Mr Enright in the hypothesis upon which he based his suspicion that acts had occurred in contravention of the Rules” (at [151]).

67 The primary judge said that on Mr Enright’s hypothesis, the donations made by the AWU were effected by an officer or employee of the National Office or the Victorian Branch of the AWU and the Rules conferred a power on the AWU to expend its funds by making donations. Furthermore, the hypothesis is based on that power being exercised by an officer without authority under the Rules and thus as a purported exercise of the expenditure power conferred by the Rules. The primary judge concluded that the donations were acts which would fall within the terms of s 320(1)(a)(ii) because in each case they were acts by a person holding an office or position in the AWU or its Victorian Branch purporting to exercise the power conferred by or under the Rules to expend the AWU’s funds. With respect to any resolution of the National Executive to delegate its powers of approval of loans, grants and donations and, on the assumption that Mr Enright regarded such a resolution as possibly grounding the contravention of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1), his hypothesis must have been that in contravention of the Rules, the National Executive exercised a power to delegate its functions. On that hypothesis, the act would fall within s 320(1)(a)(i) as an act of a collective body purporting to exercise power conferred by or under the Rules.

68 The fifth key conclusion is a holding by the primary judge that the effect of s 320 of the RO Act is to notionally alter the facts so that the act in question is deemed to have been in compliance with the Rules at the time the act was done (at [159]).

69 In the context of that conclusion, the primary judge rejected three arguments advanced by the Commissioner.

70 First, the Commissioner submitted that s 320 did not operate from the time of non-compliance, but from a point in time four years after the non-compliance. The primary judge rejected this argument by reference to what he considered the proper construction of the section and by reference to relevant authorities, in particular, Egan v Harradine (1975) 6 ALR 507; (1975) 25 FLR 336 (Egan v Harradine) at 380 per Sweeney and Evatt JJ. The primary judge went on to say that even if this conclusion was wrong and it was possible to say that there had been historical contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1), but contraventions which could not be proved because more than four years had passed, that would not be relevant because Mr Enright’s satisfaction must be understood to have been based upon his suspicion that there were contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) which were capable of being proved. Even if Mr Enright proceeded on the basis of historical contraventions only, he could hardly be said in those circumstances to have proceeded reasonably.

71 Secondly, the Commissioner submitted that it was at least arguable that s 320 cannot have the effect of defeating civil penalty proceedings. The primary judge rejected this argument. He considered that there was neither textual nor contextual support for construing the deeming effect of s 320 as being selective in its operation so that it would have no operation on an act when that act is relied upon to found a contravention of a civil penalty provision. In addition, the terms of s 320(2) supported the operation of s 320(1) in relation to Court orders or other judicial acts made after the end of the four year period referred to in s 320(1).

72 Thirdly, the Commissioner relied on s 321 of the RO Act which provides that where, having regard to the interests of the organisation, or members or creditors of the organisation, or persons having dealings with the organisation, the Federal Court is satisfied that the application of s 320 in relation to an act would do “substantial injustice”, s 320 does not apply and is taken never to have applied to that act. The primary judge rejected this argument on the basis that it was, as his Honour put it, “highly speculative” and because it impermissibly departed from Mr Enright’s reasons to take up a possibility which played no part in the formation of Mr Enright’s satisfaction that reasonable grounds existed. It is not necessary for me to describe this argument any further. The Commissioner did not repeat it on the appeal.

73 The sixth key conclusion is the finding by the primary judge that the facts assumed by Mr Enright which were central to the suspicion he formed, namely, the various acts done in contravention of the Rules “could not have existed” as acts done in contravention of the Rules at the time Mr Enright formed his opinion that there were reasonable grounds for the Investigation. The primary judge said that a reasonable person with a correct understanding of the operation of s 320 upon assumed facts central to Mr Enright’s suspicions of acts in breach of the Rules, could not have been satisfied, as Mr Enright was satisfied, that by reason of that suspicion, reasonable grounds existed for the conduct of an investigation into whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened.

74 The seventh key conclusion is a finding by the primary judge about materiality assuming he was wrong about the scope of Mr Enright’s reasonable grounds (i.e., the third key conclusion set out above). The primary judge said that even if he had been satisfied that there were matters beyond the contraventions of the Rules which grounded Mr Enright’s suspicions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1), he would arrive at the same ultimate conclusion because there was nothing in the Decision Record to suggest that the suspicion Mr Enright arrived at, and the satisfaction he formed based upon it, would have been arrived at by him in the absence of his reliance upon the view that “there are reasonable grounds for suspecting” contraventions of the Rules (at [166]).

75 The eighth and final key conclusion is the holding by his Honour that Mr Enright’s misconstruction of s 320 did not of itself constitute jurisdictional error.

76 Although it was unnecessary for the primary judge to do so, he went on to consider the second limb of the second ground of the AWU’s application for judicial review, that is to say, the allegation that the Commissioner’s decision was affected by jurisdictional error because in not adverting to s 320 of the RO Act, the Commissioner misunderstood the law he was to apply.

77 Section 320 is not referred to in the Decision Record. Mr Enright gave evidence that he regarded the provision as “inapplicable in this case”. The primary judge noted that Mr Enright did not explain why he regarded the provision as inapplicable, but at the same time, he was not pressed on that matter or challenged as to the veracity of his evidence. In the circumstances, the primary judge said there was no basis for the AWU’s contention that Mr Enright ought not to be accepted as to the evidence he gave which supports the conclusion that he considered s 320 (at [168]).

78 The alternative submission made by the AWU was that if Mr Enright thought that s 320 was inapplicable, he must have misunderstood the operation of the section. The primary judge said that, for reasons he had already given, Mr Enright was wrong to have regarded s 320 as inapplicable for the purpose of arriving at the suspicion and the consequent opinion arrived at by him, but that that did not in itself constitute jurisdictional error. The primary judge said that as the passage from the judgment of Latham CJ in R v Connell; Ex parte Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd (1944) 69 CLR 407 at 430 and 432 demonstrates, “misconstruing the terms of the legislation” means to misconstrue the law under which the decision-maker is required to reach the requisite opinion. In this case, that law was s 331(2) and not s 320 of the RO Act. The primary judge then said that it followed that the misconstruction by Mr Enright of s 320 would not, of itself, have given rise to jurisdictional error. However, the misconstruction of s 320 contributed to Mr Enright “not proceeding reasonably” under s 331(2) because a reasonable person proceeding on a correct construction of s 320 could not have formed the opinion that was formed by Mr Enright. The primary judge said (at [171]):

… Accordingly, the AWU has succeeded in its reliance on s 320 for the first limb of ground 2 but not for the second limb.

79 Before leaving this section of the reasons, it is necessary to say something more about Mr Enright’s approach to s 320 of the RO Act. That matter lay at the heart of the primary judge’s holding of jurisdictional error because his Honour held that a reasonable person with a correct understanding of s 320 could not have been satisfied that reasonable grounds existed for the conduct of an investigation into whether ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened.

80 Mr Enright had considered s 320, but had decided that it did not have any work to do and was not applicable in this case.

81 The primary judge discussed Mr Enright’s view as to the inapplicability of s 320 of the RO Act in the context of his consideration of whether Mr Enright’s decision to conduct the Investigation was motivated by an improper political purpose, that is, the third ground of the AWU’s application for judicial review (at [315]–[325]). In that context, his Honour declined to find that Mr Enright’s view as expressed by him in his evidence that s 320 of the RO Act was inapplicable was not a genuine and longstanding view held by him.

82 Mr Enright was not asked what he meant by “inapplicable” and, as I have said, s 320 is not even mentioned in the Decision Record. He was not asked whether inapplicability meant never relevant, or only irrelevant at the stage of deciding whether or not to conduct an investigation. He was not asked precisely how he construed s 320 of the RO Act. When counsel for the AWU was asked in the course of submissions to this Court what was Mr Enright’s “misconstruction” of s 320 (as the primary judge put it; see, for example, at [171]), he responded by saying that the way the AWU put its case below and the way in which the primary judge has approached the matter, was that an error is to be inferred from the result and, in that respect, counsel referred to the well-known statement of principle by Dixon J in Avon Downs Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1949) 78 CLR 353 at 360 as follows:

If the result appears to be unreasonable on the supposition that he addressed himself to the right question, correctly applied the rules of law and took into account all the relevant considerations and no irrelevant considerations, then it may be a proper inference that it is a false supposition. It is not necessary that you should be sure of the precise particular in which he has gone wrong. It is enough that you can see that in some way he must have failed in the discharge of his exact function according to law.

83 I agree with counsel for the AWU that without expressly saying so, that is how the primary judge reached his conclusion that Mr Enright had misconstrued s 320 of the RO Act.

The Structure of the Commissioner’s Arguments on the Appeal

84 As I have said, there are nine grounds of appeal. The Commissioner submitted that he did not need to succeed on all of them in order to establish his case on appeal that the orders of the primary judge should be set aside and the application for judicial review dismissed. Furthermore, he put some of the grounds of appeal on the assumption that he had failed on earlier grounds.

85 As argued by the Commissioner, and adopting the order in which he put his arguments, the grounds of appeal may be arranged as follows:

(1) Grounds 7, 6 and 8. The Commissioner submitted that if these grounds succeed, then it is not necessary to consider the other grounds of appeal. In other words, if these grounds are upheld, then the appeal must be allowed and the orders of the primary judge set aside;

(2) Grounds 1 and 2. The Commissioner submitted, as I understood him, that if the Court goes on to consider these grounds, it does so on the basis that the earlier grounds (i.e., grounds 7, 6 and 8) have failed and that the primary judge was correct to find that Mr Enright had suspected that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened. I say “as I understood him” because, with respect, it was not always easy to be clear as to the assumptions upon which various arguments were being put;

(3) Ground 9 to the extent to which it does not overlap with ground 8 (which I have chosen to include in the first category) is put on the assumption that Mr Enright did, in fact, misconstrue s 320 of the RO Act and it is argued by the Commissioner that nevertheless the error did not go to jurisdiction; and

(4) Grounds 3, 4 and 5. These grounds were addressed last by the Commissioner and on the basis that “they only arise in the event the Commissioner has failed on every other ground of appeal” (Commissioner’s Outline of Submissions dated 7 April 2020, para 49).

Grounds 7, 6 and 8 of the Appeal

86 These grounds appear under the heading Reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation and are as follows:

6. The primary judge erred by finding (at [113]) that for the appellant to be satisfied under section 331(2) of the FWRO Act that there were reasonable grounds to commence an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened, the appellant:

(a) must have a state of mind as to whether the provision being investigated has been contravened; or alternatively

(b) if a state of mind is necessary, that the state of mind must be (at least) a reasonable suspicion that the provision being investigated has been contravened.

7. Further or alternatively to ground 6, the primary judge erred by finding (at [114]) that the appellant’s delegate held a state of mind that sections 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) of the FWRO Act had been contravened.

8. Further to ground 6, the primary judge erred by finding (at [165] and [171]) that in order for the appellant (via his delegate) to be satisfied that there were reasonable grounds to commence an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened, the appellant (via his delegate) had to hold a correct understanding of the legal effect of section 320 of the FWRO Act on the relevant acts.

87 The starting point for the Commissioner’s arguments on the appeal is ground 7. The question which is raised by ground 7 of the appeal relates to his Honour’s first key conclusion and is what was in fact Mr Enright’s state of mind about possible contraventions at the time he made his decision. As I have said, the primary judge found that Mr Enright “unquestionably” held a state of mind about whether ss 237(1), 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened and relied upon that state of mind in forming the opinion he did under s 331(2). The Commissioner submitted that Mr Enright’s state of mind was not a suspicion of contraventions, but rather that there were reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision had been contravened. If the Commissioner succeeds on this argument, he must also succeed on the next argument which is raised by ground 6 of the appeal and relates to his Honour’s second key conclusion. In other words, he must establish that it is not the case, as the primary judge held, that as a matter of law in order to engage the power in s 331(2), Mr Enright needed, at least, to have a reasonable suspicion of a contravention. If the Commissioner succeeds on these two grounds, then he submitted that Mr Enright did not have to have a correct understanding of the legal effect of s 320 (ground 8 of the appeal) in order to decide to conduct an investigation under s 331(2) and the holding of jurisdictional error by the primary judge was erroneous. In other words, a correct understanding of s 320 was not “critical” (to use the primary judge’s word at [319]) because Mr Enright did not, and was not, as a matter of law, required to suspect that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened. In those circumstances, the whole foundation for his Honour’s finding of jurisdictional error was removed.

88 The Commissioner’s submission that the primary judge erred in finding that Mr Enright’s state of mind was one of a suspicion that there had been contraventions of civil penalty provisions was based on the following: (1) the contention that he had such a suspicion was never put to him in the course of his evidence; (2) there is no statement in his decision as recorded in the Decision Record that he had such a suspicion that ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had been contravened; and (3) leaving aside a suspected contravention of s 237(1), the suspicions expressed by Mr Enright in the Decision Record were as to breaches of the Rules, not civil penalty provisions.

89 In my opinion, the Commissioner’s overall submission should be accepted for the reasons which follow.

90 It is clear from the primary judge’s reasons that his finding about Mr Enright’s state of mind was based on inferences he drew and was not affected by impressions formed by him about the credibility and reliability of Mr Enright or other witnesses. In those circumstances, this Court is in as good a position as the primary judge to determine the inferences which should be drawn. This Court will give respect and weight to the conclusion of the primary judge, but “once having reached its own conclusion, will not shrink from giving effect to it” (Warren v Coombes [1979] HCA 9; (1979) 142 CLR 531 at 551 per Gibbs ACJ, Jacobs and Murphy JJ; see also Lee v Lee [2019] HCA 28; (2019) 266 CLR 129 at [55]–[56] per Bell, Gageler, Nettle and Edelman JJ).

91 The Decision Record consists of two sections, being a section entitled “Decision” and a section entitled “Reasons”.

92 The “Decision” section is drafted so as to incorporate the phraseology in s 331(2). The section also contains a reference to “possible contraventions” and whether particular sections “were contravened”.

93 In the “Reasons” section, Mr Enright refers to “alleged possible contraventions” and then expresses a state of satisfaction in terms of s 331(2), that is to say, there are reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether civil penalty provisions have been contravened. Mr Enright does refer to the civil penalty provisions and Rule 57 in this section, but only in a way which describes their content and effect (at paragraphs a. and b.).

94 Mr Enright expresses a view in relation to s 237(1) and the obligation to lodge with the Commissioner details of loans, grants and donations within a certain period of time and that view is that the material suggested that statements were lodged late in contravention of s 237(1) (paragraph c.). The Commissioner accepts that the reasons in the Decision Record are such that it should be concluded that Mr Enright suspected that s 237(1) had been contravened. As I have said, the AWU did not dispute that Mr Enright had proceeded reasonably in relation to the contravention or suspected contravention of s 237(1).

95 Paragraph d. is part of the narrative and is in the following terms:

It has been reported in various media articles that the GetUp donations and the political donations relating to the 2007 Federal Election were not approved by the National Executive in accordance with Rule 57. I have invited the AWU to provide documents voluntarily as to whether each donation was approved by the National Executive in accordance with Rule 57, but the AWU has failed or refused to do so.

96 Paragraph e. in the Decision Record is a critical paragraph and it will assist to set it out, other than those parts of it that relate to the reporting requirements in s 237(1):

e. I conclude that there are matters warranting investigation in relation to the following:

i. there are reasonable grounds for suspecting the National Executive may have neither satisfied itself that the GetUp donations were made in accordance with the AWU’s Rules nor approved the GetUp donations …

ii. there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that the National Executive may have resolved to delegate its power to approve the political donations relating to the 2007 Federal Election. This further give [sic] rise to reasonable grounds for suspecting that the National Executive may not have approved the aforementioned political donations or satisfied itself that the donations were made in accordance with the AWU’s Rules …

97 The effect of these statements is that Mr Enright reasonably suspected facts which, on their face, supported a conclusion that there had been contraventions of the Rules. There is no expression in these statements of a belief, opinion or suspicion about contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) of the RO Act. Breaches of the Rules and contraventions of civil penalty provisions in the RO Act are clearly two different things. With respect, it is not clear why the primary judge found that Mr Enright suspected that contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1) had occurred. There is very little in his reasons directed to this precise issue. Perhaps his Honour was influenced by his conclusion on the question of law to the effect that the power in s 331(2) is only engaged if the decision-maker reasonably suspects a contravention of a civil penalty provision and by the fact that any investigation is about whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened.

98 At all events, there is no reason to go beyond the Decision Record in order to determine Mr Enright’s suspicions and the Decision Record indicates that he suspected nothing more than facts which would or could give rise to the conclusion that there had been breaches of the AWU’s Rules. In my opinion, the primary judge’s finding about Mr Enright’s state of mind was erroneous. I do not consider that Mr Enright suspected that there had been contraventions of ss 285(1), 286(1) and 287(1).

99 In light of this conclusion, the Commissioner must, in order to avoid establishing a different jurisdictional error (i.e., a failure to form the state of mind required for the exercise of the power in s 331(2)) negate the proposition that an exercise of the power in s 331(2) is conditioned on a state of mind of a suspicion that there has been a contravention of a civil penalty provision.

100 The starting point for the purposes of determining this issue is the text of the subsection. Subsection 331(2) provides that the decision-maker must be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation as to whether there has been a contravention of a civil penalty provision. The subsection does not require the Commissioner to have reasonable grounds for believing or suspecting that there has been a contravention of a civil penalty provision. As the Commissioner pointed out, a consideration of other sections in the RO Act shows that where Parliament intended that a person must have reasonable grounds for believing or suspecting a circumstance to have occurred, such as a breach or contravention, before taking action, or exercising a power, then Parliament has used those words, or words to very similar effect (see, for example, ss 257(11), 273(2)(b), and 278(2) of the RO Act). Furthermore, the phrase “as to whether” in s 331(2) seems to be used as a form of shorthand for “as to whether or not” a civil penalty provision has been contravened. In my opinion, that consideration points away from a conclusion that the decision-maker under s 331(2) must, before exercising the power, have formed a belief or a suspicion on reasonable grounds that a contravention has occurred. Finally, in terms of text, the fact that the power in s 331(2) is a power to investigate, not a power to report or refer, or to prosecute or charge, also, in my opinion, points away from a conclusion that there must be a belief or suspicion on reasonable grounds that a contravention of a civil penalty provision has occurred before the power is exercised.

101 I turn now to the context in which the subsection appears and to the purpose of the subsection.

102 Section 331 of the RO Act deals with the Commissioner’s power to conduct investigations. It is convenient at this point to set the section out in full:

331 Commissioner may conduct investigations

(1) If the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so, the Commissioner may conduct an investigation as to whether:

(a) a provision of Part 3 of Chapter 8 has been contravened; or

(b) the reporting guidelines made under that Part have been contravened; or

(c) a regulation made for the purposes of that Part has been contravened; or

(d) a rule of a reporting unit relating to its finances or financial administration has been contravened.

(2) If the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for doing so, the Commissioner may conduct an investigation as to whether a civil penalty provision (see section 305) has been contravened.

(3) The Commissioner may also conduct an investigation in the circumstances set out in the regulations.

(4) Where, having regard to matters that have been brought to notice in the course of, or because of, an investigation under subsection (1) or (2), the Commissioner forms the opinion that there are grounds for investigating the finances or financial administration of the reporting unit, the Commissioner may make the further investigation.

(5) An investigation may, but does not have to, follow inquiries under section 330.

The Court was told that no regulations have been made under s 331(3).

103 The wording of subsections (1) and (2), save for that part which identifies the subject matter of an investigation, is in material respects the same and each subsection is to be given a similar interpretation. Subsection (5) makes it clear that whilst an investigation may follow an inquiry, it does not have to follow an inquiry.

104 The Commissioner is given extensive powers which may be exercised in the conduct of an investigation. Those powers include the power to compel persons to provide information or documents, to answer questions or to provide other reasonable assistance to the Commissioner (s 335). A failure to comply with these obligations is an offence (s 337). The Commissioner may apply for the issue of a search warrant in the course of an investigation (s 335K and the sections which follow). Each of these powers is subject to its own conditions for the exercise of the power.

105 The Commissioner also has the power to make inquiries under s 330 of the RO Act and that includes the power to make inquiries as to whether a civil penalty provision has been contravened (s 330(2)). The person making inquiries cannot compel a person to assist with the inquiries under s 330. The subject matter of inquiries under s 330(1) is the same subject matter of investigations under s 331(1) save that the inquiries are as to whether various matters are being complied with and investigations are as to whether those matters have been contravened. The subject matter of inquiries under s 330(2) is the same as the subject matter of investigations provided for in s 331(2), save that there is no requirement that the Commissioner be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for making the inquiries.

106 The Commissioner has the power to bring proceedings for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty for the contravention of a civil penalty provision (s 310).

107 The functions of the Commissioner are set out in s 329AB and that section provides as follows:

329AB Functions of the Commissioner

The Commissioner has the following functions:

(a) to promote:

(i) efficient management of organisations and high standards of accountability of organisations and their office holders to their members; and

(ii) compliance with financial reporting and accountability requirements of this Act;

including by providing education, assistance and advice to organisations and their members;

(b) to monitor acts and practices to ensure they comply with the provisions of this Act providing for the democratic functioning and control of organisations;

(c) such other functions as are conferred on the Commissioner by this Act or by another Act;

(d) to do anything incidental to or conducive to the performance of any of the above functions.

108 The Explanatory Memorandum for the amendments to the RO Act which, among other things, established the Commissioner and the Commission, namely, the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Act 2016 No 79, 2016 (Cth) (the 2016 Amendment Act), makes it clear that the aim of the changes was to ensure the better governance of registered organisations by improving the regulatory framework. An aspect of that aim was the establishment of an “independent watchdog”, being the Commission, “to monitor and regulate registered organisations with enhanced investigation and information gathering powers”. The enhanced investigation and information gathering powers were modelled on the powers set out in the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

109 The primary judge surveyed these contextual matters and considered that the comparison between s 331 and s 330 revealed a relation between the coercive powers conferred on the Commissioner and the limitation imposed on the investigative function for which those powers have been conferred. Another way of putting this point was to say that access to the coercive powers is not to be available unless the Commissioner is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds to conduct an investigation. His Honour then made two points which he considered needed to be borne in mind in the assessment of whether a particular investigation has been commenced within the boundaries of the power conferred by s 331(2). They are as follows: (1) the requirement of reasonable grounds should be understood “as harbouring a concern for the rights ordinarily enjoyed by others and the capacity for those rights to be adversely affected by the conduct of an investigation” (at [108]); and (2) coercive powers are not usually conferred “on” fishing expeditions, the language in s 331(2) is “specific” and the Commissioner is not “at large” (at [109]).