Federal Court of Australia

Commissioner of Taxation v Glencore Investment Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 187

ORDERS

NSD 1637 of 2019 NSD 1639 of 2019 | ||

Appellant | ||

AND: | GLENCORE INVESTMENT PTY LTD ABN 67 076 513 034 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer and, if agreement can be reached, provide the Court with orders for final relief within seven days hereof, or failing that, each party shall file written submissions on the issue of the form of final relief limited to 10 pages in length.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MIDDLETON AND STEWARD JJ.

1 For the years of income ended 31 December 2007 to 31 December 2009 in lieu of the years of income ended 30 June 2008 to 30 June 2010 (the “2007 to 2009 years”), Cobar Management Pty Ltd (“C.M.P.L.”), a resident of the Commonwealth of Australia, sold copper concentrate to its ultimate parent, Glencore International A.G. (“G.I.A.G.”), a resident of the Swiss Confederation. It did so pursuant to amended terms agreed in February 2007 (the “C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement”). The Commissioner of Taxation (the “Commissioner”) contends that the consideration G.I.A.G. paid C.M.P.L. for its copper concentrate was not, to use a generic expression, an arm’s length price. He submits that it was too low. Relying on Australia’s transfer pricing laws — contained for the purposes of the 2007 to 2009 years in Div. 13 of Pt. III of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth.) (the “1936 Act”) and in Subdiv. 815-A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth.) (the “1997 Act”) — the Commissioner issued amended assessments to Glencore Investment Pty Ltd (the “taxpayer”), who at the time was the provisional head company of a multiple entry consolidated group. C.M.P.L. was a subsidiary member of that group. The amended assessments included in the assessable income of the taxpayer what the Commissioner contended, and still contends, was the correct arm’s length consideration for the sale by C.M.P.L. of copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. The learned primary judge disagreed with that contention. Her Honour was satisfied that C.M.P.L. had been paid arm’s length consideration by G.I.A.G., and accordingly that the amended assessments were wholly excessive. The Commissioner appeals that decision to this Court.

Legislation and Swiss Treaty

2 It is necessary to set out the applicable provisions of Div. 13 of the 1936 Act and Subdiv. 815-A of the 1997 Act. Div. 13 has been repealed, but relevantly continues to apply to the 2007 to 2009 years.

3 Here, in applying Div. 13, the Commissioner made determinations pursuant to both ss. 136AD(1) and (4) for the 2007 to 2009 years. Sections 136AD(1) and (4) provided:

Arm’s length consideration deemed to be received or given

(1) Where:

(a) a taxpayer has supplied property under an international agreement;

(b) the Commissioner, having regard to any connection between any 2 or more of the parties to the agreement or to any other relevant circumstances, is satisfied that the parties to the agreement, or any 2 or more of those parties, were not dealing at arm’s length with each other in relation to the supply;

(c) consideration was received or receivable by the taxpayer in respect of the supply but the amount of that consideration was less than the arm’s length consideration in respect of the supply; and

(d) the Commissioner determines that this subsection should apply in relation to the taxpayer in relation to the supply;

then, for all purposes of the application of this Act in relation to the taxpayer, consideration equal to the arm’s length consideration in respect of the supply shall be deemed to be the consideration received or receivable by the taxpayer in respect of the supply.

...

(4) For the purposes of this section, where, for any reason (including an insufficiency of information available to the Commissioner), it is not possible or not practicable for the Commissioner to ascertain the arm’s length consideration in respect of the supply or acquisition of property, the arm’s length consideration in respect of the supply or acquisition shall be deemed to be such amount as the Commissioner determines.

4 It was accepted that the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement was an “international agreement” for the purposes of Div. 13. The taxpayer did not otherwise dispute that G.I.A.G. and C.M.P.L. did not relevantly deal with each other at arm’s length (although it claims that C.M.P.L. was nonetheless paid arm’s length consideration). It also did not dispute that the Commissioner had been lawfully satisfied that C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. were not relevantly dealing with each other at arm’s length. Nor did the taxpayer challenge the legal efficacy of the determinations the Commissioner had made.

5 Section 136AA(3) of the 1936 Act provided as follows in respect of the definition of arm’s length consideration and related matters:

Interpretation

…

(3) In this Division, unless the contrary intention appears:

…

(b) a reference to consideration includes a reference to property supplied or acquired as consideration and a reference to the amount of any such consideration is a reference to the value of the property;

(c) a reference to the arm’s length consideration in respect of the supply of property is a reference to the consideration that might reasonably be expected to have been received or receivable as consideration in respect of the supply if the property had been supplied under an agreement between independent parties dealing at arm’s length with each other in relation to the supply;

...

(e) a reference to the supply or acquisition of property under an agreement includes a reference to the supply or acquisition of property in connection with an agreement.

6 Subdivision 815-A was inserted into the 1997 Act in 2012, but is relevantly expressed to apply retrospectively to the 2007 to 2009 years by reason of s. 815-1 of the Income Tax (Transitional Provisions) Act 1997 (Cth.) (the “Transitional Provisions Act”). The taxpayer did not challenge the validity of Subdiv. 815-A’s retrospective application.

7 The object of Subdiv. 815-A of the 1997 Act is set out in s. 815-5, which relevantly provides:

Object

The object of this Subdivision is to ensure the following amounts are appropriately brought to tax in Australia, consistent with the arm’s length principle:

(a) profits which would have accrued to an Australian entity if it had been dealing at *arm’s length, but, by reason of non-arm’s length conditions operating between the entity and its foreign associated entities, have not so accrued;

8 The operative provision is s. 815-10, which relevantly provides:

Transfer pricing benefit may be negated

(1) The Commissioner may make a determination mentioned in subsection 815-30(1), in writing, for the purpose of negating a *transfer pricing benefit an entity gets.

Treaty requirement

(2) However, this section only applies to an entity if:

(a) the entity gets the *transfer pricing benefit under subsection 815-15(1) at a time when an *international tax agreement containing an *associated enterprises article applies to the entity; or

(b) the entity gets the transfer pricing benefit under subsection 815-15(2) at a time when an international tax agreement containing a *business profits article applies to the entity.

9 The Commissioner made determinations here pursuant to this provision for the 2007 to 2009 years in addition to the determinations made under Div. 13 of the 1936 Act.

10 Section 815-15 delineates when a taxpayer gets a transfer pricing benefit for the purposes of s. 815-10. The section relevantly provides:

When an entity gets a transfer pricing benefit

Transfer pricing benefit—associated enterprises

(1) An entity gets a transfer pricing benefit if:

(a) the entity is an Australian resident; and

(b) the requirements in the *associated enterprises article for the application of that article to the entity are met; and

(c) an amount of profits which, but for the conditions mentioned in the article, might have been expected to accrue to the entity, has, by reason of those conditions, not so accrued; and

(d) had that amount of profits so accrued to the entity:

(i) the amount of the taxable income of the entity for an income year would be greater than its actual amount; or

(ii) the amount of a tax loss of the entity for an income year would be less than its actual amount; or

(iii) the amount of a *net capital loss of the entity for an income year would be less than its actual amount.

The amount of the transfer pricing benefit is the difference between the amounts mentioned in subparagraph (d)(i), (ii) or (iii) (as the case requires).

11 The term “associated enterprises article” is defined by s. 815-15(5) in the following way:

Meaning of associated enterprises article

(5) An associated enterprises article is:

(a) Article 9 of the United Kingdom convention (within the meaning of the International Tax Agreements Act 1953); or

(b) a corresponding provision of another *international tax agreement.

12 Relevantly here, the Commissioner may only make a determination under s. 815-10 to negate a transfer pricing benefit if an international tax agreement containing an associated enterprises article applies to the taxpayer. There was no dispute that this requirement was satisfied because of the application to the taxpayer of Art. 9 of the Agreement between Australia and Switzerland for the Avoidance of Double Taxation with Respect to Taxes on Income, and Protocol [1981] ATS 5 (the “Swiss Treaty”). The Swiss Treaty has since been replaced by the Convention between Australia and the Swiss Confederation for the Avoidance of Double Taxation with respect to Taxes on Income, with Protocol [2014] ATS 33, but that agreement only entered into force on 14 October 2014. Accordingly, Art. 9 of the Swiss Treaty is the relevant associated enterprises article for the 2007 to 2009 years. It provided:

Where –

(a) an enterprise of one of the Contracting States participates directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of an enterprise of the other Contracting State; or

(b) the same persons participate directly or indirectly in the management, control or capital of an enterprise of one of the Contracting States and an enterprise of the other Contracting State,

and in either case conditions operate between the two enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which might be expected to operate between independent enterprises dealing wholly independently with one another, then any profits which, but for those conditions, might have been expected to accrue to one of the enterprises, but, by reason of those conditions, have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly.

13 The taxpayer did not dispute that some conditions operated between C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. which differed from those which might be expected to have operated between independent enterprises dealing wholly independently with one another. It accepted that G.I.A.G. exercised financial and managerial control over C.M.P.L.’s mine.

14 Subdivision 815-A identifies certain extrinsic documents which must be considered when applying its provisions. A determination as to whether a taxpayer got a transfer pricing benefit must be made “consistently” with those documents “to the extent the documents are relevant.” Similarly, an international tax agreement must be construed consistently with those documents to the extent that they are relevant to that task. Section 815-20 thus provides:

Cross-border transfer pricing guidance

(1) For the purpose of determining the effect this Subdivision has in relation to an entity:

(a) work out whether an entity gets a *transfer pricing benefit consistently with the documents covered by this section, to the extent the documents are relevant; and

(b) interpret a provision of an *international tax agreement consistently with those documents, to the extent they are relevant.

(2) The documents covered by this section are as follows:

(a) the Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital, and its Commentaries, as adopted by the Council of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and last amended on 22 July 2010;

(b) the Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, as approved by that Council and last amended on 22 July 2010;

(c) a document, or part of a document, prescribed by the regulations for the purposes of this paragraph.

(3) However, a document, or a part of a document, mentioned in paragraph (2)(a) or (b) is not covered by this section if the regulations so prescribe.

(4) Regulations made for the purposes of paragraph (2)(c) or subsection (3) may prescribe different documents or parts of documents for different circumstances.

15 By reason of s. 815-5 of the Transitional Provisions Act, the parties agreed that the relevant version of the Transfer Pricing Guidelines are those which were published by the Council of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (the “O.E.C.D.”) in 1995 (the “Transfer Pricing Guidelines”).

The Facts Found by the Learned Primary Judge

16 Nearly all of the facts found by the learned primary judge were not in dispute. Rather, and with respect, the real contest before us was as to which expert’s opinion should be preferred: that of Mr. Wilson, one of the experts called by the taxpayer; or that of Mr. Ingelbinck, one of the experts called by the Commissioner. We shall return to this issue.

17 C.M.P.L. owned and operated an underground copper mine at Cobar in central western New South Wales. The Glencore Group, if it may be so called, acquired the mine in the late 1990s. C.M.P.L. entered into its first contract to sell all of its copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. in 1999. The mine had two attributes which should be mentioned; it was relatively small and it had high operating costs. The learned primary judge described the mine (the “C.S.A. mine”) in the following terms at [111]-[112]:

The CSA mine is a high grade underground copper mine and copper concentrate plant located near the town of Cobar in New South Wales. Although in the relevant years it was the largest of the copper mines in the Cobar region, in relative terms it is a small mine. Mr Kelly deposed that by way of comparison some copper mines in South America (like Escondida) mine in a day or two what CSA mines in a year and, in 2006, the CSA mine’s annual production of concentrate represented about 0.2% of world copper concentrate production.

During the relevant years, the mine’s primary ore body, which was mined from an area known as QTS North, produced an homogenous copper concentrate of a consistently high grade. That ore body was comprised in a series of vertical lenses and was mined using the long hole open stoping method. Mr Kelly gave the following description of the steps involved in the mining operations:

(a) mining of the underground stopes occurred at depths of about 1,400 metres to 1,500 metres;

(b) vehicle and heavy machinery accessed the underground stopes via the decline, which was a road which descended into the mine from the surface in a corkscrew manner to a depth of about 1,400 metres to 1500 metres; regular worker and materials access to the mining operations was via a shaft that extended from the surface to a depth of 980 metres, and then via the decline to a depth of 1,400 metres to 1,500 metres;

(c) the stopes, once accessed, were drilled and blasted;

(d) once blasted, the ore was collected and transported in trucks to an underground stockpile located at a depth of about 980 metres;

(e) from the stockpile, the ore was transported via the ore pass to a primary crusher and then to the surface via the vertical shaft;

(f) once the ore reached the surface, the ore was transferred to mills where it was ground to a slurry;

(g) the slurry was then pumped to a flotation tank to separate the different minerals which were skimmed from the flotation cells and then dried. This skimmed and dried material is the copper concentrate which the mine sold; and

(h) copper concentrate produced at CSA was stockpiled before being transported by rail to the port at Newcastle from where it was then shipped to various ports in Asia.

18 Her Honour accepted the following explanation given by the taxpayer’s lay witness as to why the mine had such high operating costs at [114]:

Mr Kelly’s evidence was that:

(a) the depth of the mine and the need to continue mining deeper into the ore body gave rise to significant technical and financial challenges for the mine and led to high operating costs. This was because the depth of the mine increased the complexity, time, effort and cost involved in extracting the copper ore from the mine face, getting it to the underground stockpile and then transporting it from the stockpile to the surface; the mine’s depth required expenditure on infrastructure, extensive ground support and stabilisation regimes, as well as systems to provide adequate ventilation, power and air conditioning; and there were difficulties in accessing the deep underground stopes both to bring workers and equipment to and from the underground stopes and in transporting extracted ore to the surface and gave rise to congestion in the movements, as well as long trucking distances, restricting operations. Mr Kelly deposed that from at least 2004, CSA worked on projects with a view to making mining at depth more economical, including a proposal to extend the shaft to a depth of 1,500 metres;

(b) the remoteness of the mine made it difficult to attract and retain employees and there were significant vacancies in key roles for long periods of time. For an 18 month period leading up to October 2007, there was no mine manager and at other times the mine manager changed regularly; and

(c) the mine faced the issue of having enough water to support the mine’s production. He explained that mining operations cannot occur without a water supply and Cobar is a dry town. Its main source of water is the Burrendong dam which caters for the greater Cobar region. The dam level fell to below 3% capacity in 2007 and there was not enough water to support the town, agriculture and mining. Priority was given to the town and agriculture and CSA was required to find alternative water sourced by drilling for water, retreating water and trucking water to the site.

19 The learned primary judge also made unchallenged findings about the copper concentrate market and the pricing of both concentrate and of copper. Relevantly they were as follows:

(a) Copper concentrate comes from mining sulphide and oxide ore. The copper content of such concentrate is highly variable (from around 10 to 50%). It may be present with other valuable minerals, such as gold and silver, as well as with impurities. Smelters refine the concentrate to produce pure copper.

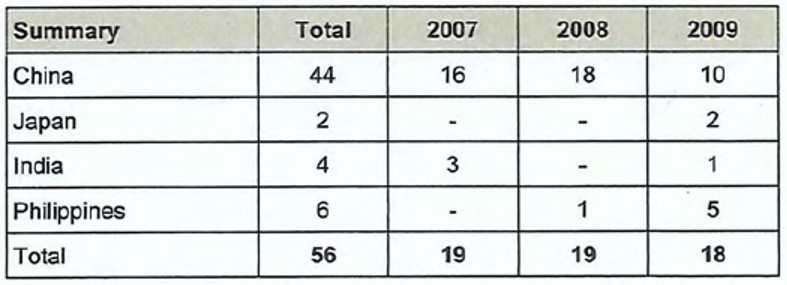

(b) Miners may sell copper concentrate to either smelters or to traders. Traders are intermediaries who buy concentrate from miners and sell it to smelters. A miner may enter into a long term contract with a trader to sell specified quantities of its concentrate or the whole of a particular mine’s production. Such contracts are known as “offtake agreements.” In this way, a miner is able to “monetize its production.” This is what C.M.P.L. did. It sold all of its copper concentrate from the C.S.A. mine to G.I.A.G. Though it was not the subject of an express finding in her Honour’s reasons, it was not in dispute that, until August 2003, G.I.A.G. sold all of this concentrate to a smelter at Port Kembla in New South Wales. But the smelter closed. Thereafter, G.I.A.G. sold C.M.P.L.’s copper concentrate to a range of smelters located in China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines and India. A miner or a trader may also sell copper concentrate on the spot market, which accounts for about 20% of all copper concentrate trading.

(c) Whilst the copper industry has developed a pricing structure for its contracts which follows a reasonably well-established framework, each contract is nonetheless individually negotiated and the detail and pricing of individual contracts varies greatly. Critically, her Honour accepted that such variation will depend “on the needs and risk appetites of the seller and buyer and whether the contracts are for spot sales or medium/long-term contracts” (at [72]).

(d) The “well-established” pricing framework was as follows:

(i) Unlike pure copper, there is no terminal market for copper concentrate where it can be traded for a given price.

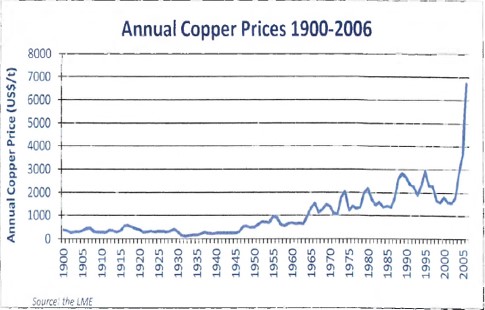

(ii) Nonetheless, the price of refined copper as quoted on a metal exchange, such as the London Metal Exchange (“L.M.E.”), is the starting point for determining the price of copper concentrate. The price of pure copper is volatile. In 2006, being the year leading up to the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement, the copper price reached unheard of heights. This is illustrated by the following graph, extracted from a report prepared by the taxpayer’s expert, Mr. Wilson.

(iii) Offtake agreements specify the period, whether a day, days, weeks or months, with which the price or average price of the copper is to be ascertained. In the industry this is known as the “quotational period.” Some agreements give the buyer options about how to choose the applicable quotational periods and how often such choices can be made. We will call this “quotational period optionality.” These options are described in more detail below. The C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement gave G.I.A.G. a number of such options. The Commissioner complains that they favoured G.I.A.G.’s position.

(iv) A deduction is then made from the ascertained copper price notionally on account of the cost to a smelter of treating and refining the copper concentrate (called “T.C.R.C.s”). This permits the trader or smelter potentially to make a profit. The size of that deduction is a matter for negotiation and often bears little relationship to the actual costs of treating and refining the concentrate.

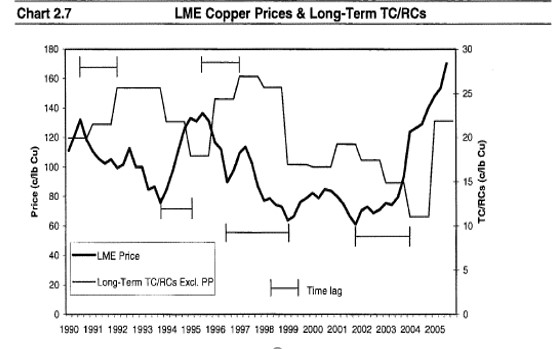

(v) There are different ways of determining T.C.R.C.s. One way is to adopt benchmark T.C.R.C.s which are established annually by the major players in the copper concentrate industry. Ordinarily applicable to a given year, parties may use that benchmark or agree to negotiate a deduction for T.C.R.C.s based on that benchmark. Benchmark T.C.R.C.s are subject to significant variation from year to year. They are also not necessarily correlated with the price of refined copper. Importantly, the price of copper and the amount of the annual benchmark T.C.R.C.s can move in opposite directions. The following graph, extracted from the December 2006 Brook Hunt report, illustrates this phenomenon.

(vi) The accuracy of the above graph was never impugned. The Brook Hunt report was an annual industry report which examined the global market for copper concentrate. It was used by players in the industry. Her Honour described the role of the Brook Hunt reports in the copper industry at [93] as follows:

It was common ground between the experts and, similarly, it was the evidence of Mr Kelly, that market participants, including miners, traders and smelters, access information in relation to the copper market and particularly the copper concentrate market from industry publications such as the Brook Hunt Reports (which Mr Wilson authored/edited for around 30 years). The Brook Hunt Report presents a global analysis of the market each year. Mr Kowal and Mr Ingelbinck [the Commissioner’s experts] both acknowledged that Brook Hunt is an authoritative resource and, whether accurate or not, influences negotiations in the copper concentrate market. Mr Kowal and Mr Ingelbinck each gave evidence that they relied upon Brook Hunt publications to support their opinions in these proceedings.

(vii) Another method for determining the T.C.R.C.s was to use spot T.C.R.C.s, which reflect the market at any given point in time. Spot T.C.R.C.s are “very volatile and vary greatly throughout a year” (at [80]).

(viii) Parties can use a mix of these methodologies to determine T.C.R.C.s. In the contract entered into between C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. for the sale of copper concentrate which was on foot just before February 2007, the parties agreed to negotiate the T.C.R.C.s annually in respect of 50% of the “Base Tonnage” based upon the Japanese benchmark T.C.R.C.s. For the other 50% of Base Tonnage, the negotiation was to be based on the spot market T.C.R.C.s. For any tonnage exceeding the Base Tonnage, the terms would be those that were “mutually agreed.” The Base Tonnage was defined to be 100,000 wet metric tonnes (“w.m.t.”).

(ix) In the period leading up to 2007, being the first year in dispute, parties sometimes included a clause which permitted “price participation.” This permitted buyers and sellers to benefit from movements in the price of copper. For example, the parties might agree a particular L.M.E. copper price above which the refining charge would be increased by an agreed amount, and below which the refining charge would be reduced by an agreed amount. At the end of 2006, it was expected that price participation was unlikely to be used by buyers and sellers, or be set to zero.

(x) A fundamentally different formula for determining the amount of the T.C.R.C.s was called “price sharing.” Under contracts using a price sharing formula, the T.C.R.C.s are a negotiated specified percentage of the metal exchange copper price. They are not re-negotiated annually but are agreed for a period of years. That period could be between three to 13 years in length. An advantage of this type of formula was that it eliminated a particular type of dangerous volatility arising from the use of annual benchmark T.C.R.C.s, namely an inverse movement in the price of copper and benchmark T.C.R.C.s which can occur from time to time. While the formula still exposed the miner to volatility in copper prices, when the price went down, the miner would enjoy lower T.C.R.C.s; when the price went up, the T.C.R.C.s would increase, but the miner would nevertheless benefit from the increased revenues resulting from the increase in the copper price.

(xi) The taxpayer’s expert, Mr. Wilson, reported that in the December 2006 Brook Hunt report titled “Global Concentrate & Blister/Anode Markets to 2016”, it was stated that the “normal range” of price sharing is 21-26% of the copper price. The report went on to observe that price sharing was:

also reasonably equitable to both buyer and seller because when copper prices are low, so too are the fees received by the buyer and vice versa.

(xii) The C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement on foot in the 2007 to 2009 years included a term that adopted a price sharing formula at a rate of 23% of the copper price, being roughly the mid-point of the historical normal range of 21-26%. The Commissioner’s experts considered that the adoption in February 2007 of such a term was very much to the disadvantage of C.M.P.L. and was not what an independent seller would have agreed to.

(xiii) Other terms in a typical copper concentrate sale agreement further adjusted, or had the potential to adjust, directly or indirectly, the consideration receivable by the miner. These included terms prescribing penalties for the presence of deleterious elements in the copper concentrate, and terms governing freight allowances and insurance costs. As a matter of industry practice, the seller paid, directly or indirectly, for freight and insurance. In each case, the actual amount was a matter for negotiation and the agreed result might not bear much of a relationship with the actual costs of shipping and insurance. The parties could sell/buy copper concentrate on a carriage insurance and freight (“C.I.F.”) basis, whereby the seller would be responsible for arranging and paying for freight and insurance. Alternatively, the parties could sell/buy copper concentrate on a free-on-board (“F.O.B.”) basis, whereby the buyer would be responsible for shipping, but with the seller paying a freight allowance. C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G., in the 2007 to 2009 years, sold copper concentrate on an F.O.B. basis with the allowance negotiated annually. For the 2009 year only, the Commissioner contends that the allowance negotiated was not an arm’s length allowance.

(xiv) The foregoing mechanisms or formulae, when applied to a given shipment, resulted in a price for copper concentrate sold.

(e) There were other terms that parties in the copper concentrate market typically negotiated but which less directly bore upon the pricing formulae set out above. One concerned the “payable metal”, which is the negotiated percentage of the metal content of the concentrate to which the copper reference price is to be applied. Another concerned the terms of payment. It is industry practice for a seller to receive a provisional payment. If the buyer is a trader (and not a smelter) such a payment is typically made after an agreed number of days following receipt of the bill of lading and other documents. The provisional payment gives the seller a cash flow advantage, at least to an extent.

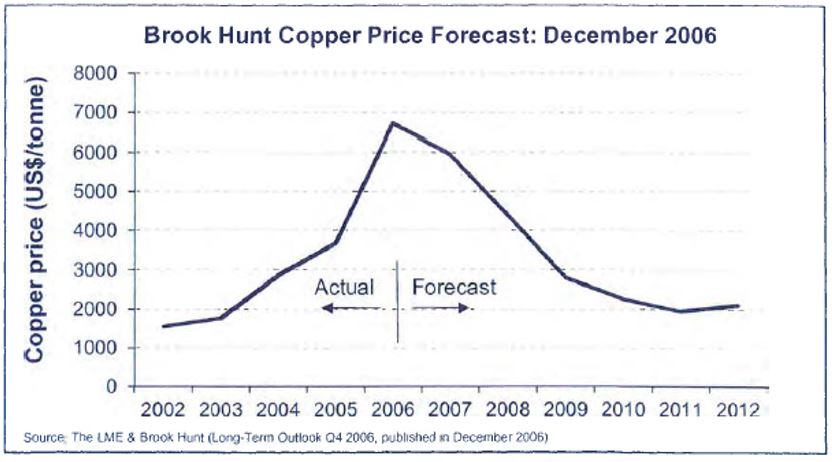

(f) The market conditions for the price of copper in 2006 were unique. The copper price had risen by more than 80% as compared to the previous year price, reaching a point that was four times the average copper price over the 1998 to 2003 period. This was unprecedented. One of the Commissioner’s experts observed that the 80% rise in copper prices in 2006 was “a somewhat unheard of event and caused all kinds of re‑evaluations amongst industry participants as to what made sense and how to structure these agreements ... people were confused”. At the start of 2007, the taxpayer’s expert considered that there would be a material decline in copper prices. The learned primary judge found that Brook Hunt’s estimates as at December 2006 for the L.M.E. price moving forward were that, for 2007, in money of day terms, the copper price would be around US$2.70/lb, in 2008 US$2/lb, in 2009 US$1.34/lb and in 2011 less than US$1/lb.

(g) By the end of 2006, the Japanese benchmark T.C.R.C.s for the 2007 year were already known (they had been determined earlier in the year). The treatment charge was set at US$60/dry metric tonne (“d.m.t.”) and the refining charge US6.0c/lb (or US15.4c/lb expressed as a combined T.C.R.C.) for 30% concentrate, with price participation for benchmark T.C.R.C.s having been set at zero. At the same time, the benchmark T.C.R.C.s for 2008 and 2009 were unknown. They were nonetheless respectively forecast to be about US$65 and then US$60 per d.m.t. for treatment charges and US6.5c/lb and then US6.0c/lb for refining charges (or US16.7c/lb and US15.4c/lb expressed as combined T.C.R.C.s). All experts agreed that balances for copper concentrate in the 2007 to 2009 years were likely to be “tight” and there was an expectation that a significant increase in T.C.R.C.s was a relatively low probability. The taxpayer’s expert thought that it was highly unlikely that T.C.R.C.s would go above US$70 a tonne over these years.

(h) Spot T.C.R.C.s were unknown for 2007. All experts agreed that spot pricing was very volatile and inherently difficult to predict.

(i) C.M.P.L.’s 2007 budget and five year plan (the “2007 Budget”) was prepared in September 2006. It predicted that C.M.P.L. would realise a significant profit in 2007. It forecast a copper price of US$2.54/lb for 2007 (Brook Hunt forecast a price of US$2.70/lb). This was noted to be a conservative forecast. The 2007 Budget stated that adequate ventilation for the mine shafts and staff retention were key issues for the C.S.A. mine. The learned primary judge also accepted that the mine was at this time facing water supply issues. Cobar was in a drought. Nonetheless, output was increasing. The production of ore had increased in 2006 by over 30%. Even though operating costs had exceeded budgeted costs in 2006 by 31%, net profit and revenue far exceeded budget estimates, due to the increase in copper prices. The 2007 Budget forecasted that cost control would be an important focus of the business in 2007. It also forecast that the amount of copper concentrate would decline consistently with an expected reduction in feed grade.

(j) Budgeted T.C.R.C.s for the 2006 year were 31.8% of forecast revenue. They ended up being only 14.9% of actual revenue. Budgeted T.C.R.C.s for the 2007 year, assuming the use of benchmark T.C.R.C.s, were US16.7c/lb (or about 6.5% of the forecast copper price). The 2007 Budget predicted for the 2008 year benchmark T.C.R.C.s of US21.8c/lb (or about 9.6% of the forecast copper price) and for the 2009 year benchmark T.C.R.C.s of US19.2c/lb (or about 9.4% of the forecast copper price). It also predicted a copper price of US$2.27/lb for the 2008 year and US$2.04/lb for the 2009 year. These were accepted to be “reasonable figures” by the learned primary judge.

(k) It was expensive to mine ore at the C.S.A. mine. The learned primary judge found that it was a “high cost” mine. Based on the actual costs for the 2006 year, Brook Hunt placed the mine at the 89th/90th percentile of “C1” costs, being the direct cash costs of the mine. The taxpayer’s expert gave uncontradicted evidence that the fact that the C.S.A. mine was a high cost mine made C.M.P.L. vulnerable to fluctuations in gross revenue for its copper concentrate.

The International Agreements between C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G.

20 The terms upon which C.M.P.L. sold copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. varied over time. However, and critically, it was always agreed that G.I.A.G. would purchase all of C.M.P.L.’s production of copper concentrate for the life of the C.S.A. mine, subject to an important qualification described below. The first offtake agreement entered into in 1999 required the parties to negotiate the T.C.R.C.s based upon the Japanese benchmark T.C.R.C.s, and specified only one quotational period. The learned primary judge summarised its terms as follows at [162]:

(a) CMPL agreed to sell and deliver, and GIAG agreed to buy and take delivery of, the entire production of copper concentrate from the CSA mine for the life of the mine starting from 1 July 1999;

(b) GIAG was to pay for 96% of the copper content of the copper concentrate (subject to a minimum deduction) at the official London Metal Exchange cash settlement quotation for Grade A copper as published in USD in the ‘Metal Bulletin’ in London, averaged over the relevant quotational period, less the TCRCs;

(c) a typical analysis of the quality of the copper concentrate produced was required to have a copper content of approximately 30%;

(d) there was one quotational period for material produced after 1 July 1999, which was the month following the month of production, with this single quotational period to remain valid for the life of the mine;

(e) the amounts to be deducted as TCRCs in respect of copper concentrate for the period between 1 July 1999 and 30 June 2000 comprised a treatment charge, a refining charge that was subject to an adjustment for “price participation” under which the charge would increase if the copper price exceeded a certain amount and would decrease if the price fell beneath that amount, and a penalty to be deducted when the bismuth content of the concentrates exceeded a certain percentage;

(f) the amounts to be deducted as the TCRCs in respect of copper concentrate and freight allowances for each delivery year after July 2000 were to be negotiated and agreed prior to the commencement of the corresponding shipment based on the existing Japanese benchmark; and

(g) if GIAG opted to take FOB Newcastle, then GIAG would be entitled to a freight credit as if the copper concentrate had been sold Cost Insurance and Freight Free Out (“CIFFO”) Main Japanese Port, with the credit fixed for each contractual year.

21 This first offtake agreement was replaced with a further agreement dated 1 October 2004. Following the closure of the Port Kembla smelter, the parties agreed to give G.I.A.G. much greater flexibility in deciding how to choose the quotational period for determining the L.M.E. copper price. This was achieved in two ways. First, from January 2005 G.I.A.G. was given the option to choose one of two classes to be declared on an annual basis, with each class containing three quotational periods. Then, within each of those two classes, one of the three quotational period options was to be declared on a shipment by shipment basis by G.I.A.G. at a later time. Secondly, the 2004 agreement introduced “back pricing”. This enabled G.I.A.G. to have knowledge of the average copper prices in (at least) one of the periods from which it was to make its selection of one of three quotational periods to be declared prior to each shipment from the loading port. This 2004 agreement was not before us. But a succeeding agreement applicable for the 2006 year and following and dated 12 December 2005 was included in the appeal papers. It contained a quotational period optionality clause which gave G.I.A.G. similar options as described above as well as back pricing. It was relevantly in these terms:

9. QUOTATIONAL PERIOD:

9.1 For copper:

The quotational period for copper shall be, in Buyer’s option, either as per item a) or as per item b) below, to be declared on an annual basis at the time of negotiation of the terms for the new Contractual Year:

a) i) The average of the calendar month prior to the month of shipment, or

ii) The average of the calendar month of shipment, or

iii) The average of the first calendar month following the month of shipment

b) i) The average of the first calendar month following the month of arrival of the carrying vessel at discharge port, or

ii) The average of the second calendar month following the month of arrival of the carrying vessel at discharge port, or

iii) The average of the third calendar month following the month of arrival of the carrying vessel at discharge port.

In case Buyer elects alternative “a)”, then the exact month, i), ii) or iii), shall be declared latest on the last LME (London Metal Exchange) market day after closing time 6 PM London time of the month of shipment, which means latest on following working day Australian time.

In case Buyer elects alternative “b)”, then the exact month, i), ii) or iii), shall be declared latest on the last LME (London Metal Exchange) market day after closing time 6 PM London time of the second month following the month of arrival of the carrying vessel at discharge port, which means latest on following working day Australian time.

22 As foreshadowed above, in December 2005, the terms upon which C.M.P.L. sold copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. changed again. The basal methodology or formula for determining price was set out at cl. 8 as follows:

The price per dry metric ton of copper concentrates shall be the sum of the payments less the deductions as specified below:

23 The clause for determining the “payments” was found in cl. 8.1.1 as follows:

Pay 96% (ninety six percent) of the final copper content, subject to a minimum deduction of 1 (one) unit, at the official LME Cash Settlement Price for Copper Grade “A” in USD, as published in the London Metal Bulletin averaged over the Quotational Period.

24 The clause setting out the “Deductions”, or T.C.R.C.s, was cl. 8.2. New cls. 8.2.1 and 8.2.2 now provided for the negotiation of T.C.R.C.s annually based upon the Japanese benchmark T.C.R.C.s for 50% of the Base Tonnage, with the remaining 50% of Base Tonnage based upon the spot market T.C.R.C.s, and for any tonnage in excess of the Base Tonnage on terms to be mutually agreed. In the 2007 Budget, it was estimated that excess tonnage would be in the region of 45,000 tonnes for that year, 39,000 tonnes for 2008 and 39,000 tonnes for 2009. Clauses 8.2.1 and 8.2.2 were relevantly as follows:

8.2 Deductions:

8.2.1 Treatment Charge for copper

Treatment charge for each Contractual Year of shipment will be negotiated and agreed between Seller and Buyer in form of an Addendum prior to the commencement of the corresponding Contractual Year.

Both parties have agreed that the terms will be negotiated on the following basis:

- 50% of the Base tonnage basis the Japanese benchmark.

- 50% of the Base tonnage basis the spot market.

For any tonnage exceeding the Base tonnage, the terms shall be mutually agreed.

8.2.2 Refining Charges:

8.2.2.1 For copper:

Refining charge for each Contractual Year of shipment will be negotiated and agreed between Seller and Buyer in form of an Addendum prior to the commencement of the corresponding Contractual Year.

Both parties have agreed that the terms will be negotiated on the following basis:

- 50% of the Base tonnage basis the existing Japanese benchmark.

- 50% of the Base tonnage basis the spot market.

For any tonnage exceeding the Base tonnage, the terms shall be mutually agreed

25 In addition, there were terms for the calculation of penalties payable by C.M.P.L. and for the making of provisional payments by G.I.A.G.

26 From 2006, the applicable agreement also provided for delivery at G.I.A.G.’s option of either “CIF F.O. main port Japan, Korea, India or China,” or on the basis of “FOB S.T. Newcastle, Australia”, in which case a freight and insurance allowance was to be mutually agreed on an annual basis at the prevailing spot market rates to “main port Japan, Korea, India or China”. In other words, in each year the parties had to agree upon which spot market rate to use by reference to the cost of shipping to Japan, Korea, India or China in order to determine a freight and insurance allowance. The applicable clauses were relevantly as follows:

6.1 CIF F.O. main port Japan, Korea, India or China, in Buyer’s option (hereinafter called “CIF shipments”).

Discharge conditions, demurrage and despatch shall be as per Charter Party, subject to Buyer’s approval.

Vessel shall furthermore be suitable for draught survey as per conditions stated in the attached Appendix No. 2, performing a constituent part of this contract.

The copper concentrates shall be shipped in accordance with IMO Code of Safe Practice for Solid Bulk Cargoes.

6.2 Buyer shall have the option to take delivery of the concentrates on basis FOB S.T. Newcastle, Australia, (hereinafter called “FOB Shipments”).

A freight and insurance allowance, based on the outturn wmt, to cover the cost of shipment from FOB S.T. Newcastle to CIF F.O. main port Japan, Korea, India or China shall be mutually agreed on an annual basis between Buyer and Seller basis prevailing spot market rates to main port Japan, Korea, India or China and shall be credited to the Buyer, unless otherwise agreed.

100% (one hundred percent) of these freight and insurance discount will be deducted from Buyer’s provisional payment to Seller (as set out in clause 10. PAYMENT, item 10.1. Provisional Payment, below).

27 We should also observe that this agreement, and we believe the pre-existing agreements, was expressed to be one that would remain in force “until the date when production ceases permanently at the Cobar mine.” However, this was qualified by G.I.A.G.’s right to terminate the agreement with 12 months’ notice prior to the end of any “Contractual Year” (being a calendar year). Relevantly, this right did not apply to a year in which terms had already been agreed for the full year.

28 In February 2007, C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. agreed to amend their agreement in four relevant ways.

29 First, the parties abandoned their 50/50 reliance on the Japanese annual benchmark T.C.R.C.s and spot T.C.R.C.s for the Base Tonnage and on the mutual agreement process to determine T.C.R.C.s for any excess tonnage. They agreed to adopt instead a price sharing clause to determine the deduction to be made for each shipment, and to forgo price participation. For the 2007 to 2009 years, T.C.R.C.s were set at 23% of the copper price. The new clauses were as follows:

Sub−clause 8.2.1 Treatment Charge and

Sub−clause 8.2.2.1 Refining Charge for copper:

Only for the Contractual Year 2007, 2008 and 2009, delete this sub−clauses entirely and replace by the following:

Combined Treatment Charge and Copper Refining Charge shall be 23% (twenty three percent) of the copper price established as set out in clause 9. QUOTATIONAL PERIOD below for the payable copper content.

The calculation of the Treatment Charge and Copper Refining Charge shall be as follows:

(copper price for establishment of Treatment Charge and Copper Refining Charge) *(multiply) 23% (twenty three percent) *(multiply) (final payable copper content) = (equal) combined Treatment Charge and Copper Refining Charge per dmt.

Sub−clause 8.2.3 Price Participation:

Not applicable for Contractual Years 2007, 2008 and 2009.

30 Because G.I.A.G. and C.M.P.L. had agreed the formula for the determination of the price of copper concentrate for the 2007 to 2009 years, it was said that G.I.A.G. had, for that period, thereby lost its right of termination. This level of certainty was important to the taxpayer’s case.

31 Secondly, the clause dealing with quotational periods was amended again to give G.I.A.G. even greater optionality. G.I.A.G. could now make its election to choose either option a) or b) (as set out above) on a shipment by shipment basis as opposed to an annual basis only.

32 Thirdly, the clause dealing with the required quality of copper was replaced. Previously, the copper concentrate had to contain 30% copper. This was reduced to 28.5%.

33 Finally, it will be recalled that the freight allowance had to be agreed annually. In 2009, by a written addendum to the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement, it was agreed that this allowance should be fixed at US$60 “per outturn wmt.” It did not appear to be in dispute that this was the rate for shipping to India. The cost of shipping to India was considerably greater than the cost of shipping to China, Korea or Japan.

The Evidence Led by the Parties

34 The taxpayer relevantly relied on one lay witness and on the opinions of one expert witness. The Commissioner relevantly relied on the opinion of two expert witnesses, but before us really relied on only one. Other expert evidence was led by the parties, but was found by the learned primary judge to be irrelevant; that finding was not challenged on appeal.

35 Perhaps the most significant feature of the taxpayer’s lay evidence is that the taxpayer did not call any person to give evidence about the entry into the various agreements, and amended agreements, referred to above. In particular, no evidence was led about why, as a fact, G.I.A.G. became entitled to increased quotational period optionality and why C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. had changed their formula for determining the T.C.R.C.s in 2007 from a part benchmark and part spot formula to a price sharing formula. No one gave evidence about how the 23% rate was determined. No one gave evidence about C.M.P.L.’s appetite for risk taking in 2007, even though, as will be seen, the taxpayer’s case turned upon how the issue of risk might bear upon the ascertainment of an arm’s length price. Nor was any evidence led of any actual negotiations between G.I.A.G. and C.M.P.L., although it would be strange if such negotiations had ever meaningfully taken place. C.M.P.L., indirectly, is a wholly owned subsidiary of G.I.A.G. The relevant provisions here effectively require the payment of an arm’s length price to C.M.P.L. But they do not require the parties otherwise to pretend that they are at arm’s length.

36 Instead, the taxpayer called Mr. David Kelly. He was an accountant who, prior to July 2006, had been employed at Deloitte. From July 2006 to April 2009 he was employed by G.I.A.G. (not C.M.P.L.) as the C.S.A. mine’s asset manager. From April 2009, he traded commodities for G.I.A.G. which included C.M.P.L.’s copper concentrate. From November 2007 until October 2017 he was also a director of C.M.P.L. He gave general evidence about the C.S.A. mine; the logistics and risks for C.M.P.L. in selling its product from 2006 to 2009 if it had been independent of G.I.A.G.; and he exhibited a number of offtake agreements which the taxpayer said contained comparable terms which had been used by arm’s length counterparties.

37 The Commissioner submitted that Mr. Kelly was not independent, had overstated his evidence, and was not qualified to give evidence about a number of matters. On occasion he tended to give inadmissible opinion evidence. The learned primary judge accepted some of these criticisms, but concluded that the case did not turn upon “the contentious parts of Mr Kelly’s affidavit evidence.” As best as we can tell, no part of the taxpayer’s case on appeal appeared to rely upon these contentious bits of his evidence.

38 The taxpayer’s expert witness was Mr. Richard Wilson. He graduated in 1981 from the Royal School of Mines, Imperial College London with an honours degree in Mineral Technology. He is an Associate of the Royal School of Mines. He had worked for Brook Hunt since 1982; for many years he wrote parts of the annual Brook Hunt report; he had been a director since 1988, and then Managing Director of that firm since 1996, and was the Chairman of Metals of Wood Mackenzie at the time of the trial below (Brook Hunt is now owned by Wood Mackenzie Ltd and has been since 2008).

39 The Commissioner took issue with the reliability of the opinions Mr. Wilson gave. He had never directly negotiated a contract for the sale of copper concentrate. He had never worked for a mine; he had never traded copper concentrate; and he had never worked for a smelter. But, it would appear, he had very extensive and detailed knowledge of the copper market that was regularly relied upon by direct participants in the market. The source of that knowledge was disclosed in his first report in the following terms:

Over the past 36 years I have spoken at numerous conferences around the world on topics related to the copper market and the economics of copper supply. My views on the copper industry are also regularly quoted in the press and in other media journals. I attach some of the most recent references to my work, along with conferences that I have attended, in Appendix B of this report. I have also attached other references to Brook Hunt/Wood Mackenzie’s data from various industry publications in Appendix B.

Wood Mackenzie initially cultivated deep expertise in upstream oil and gas, producing its first research report in 1973. It has since broadened its focus to deliver the same level of detailed insight for each connected sector of the energy, chemicals, metals and mining industries. The company employs over 1000 people in over 30 offices worldwide, including three hubs in Australia. Expert analysts and consultants provide monthly, quarterly and annual insights across the value chains of metals including copper, lead, zinc, nickel, aluminium and gold. Wood Mackenzie has few direct competitors; these include Commodity Research Unit (CRU), Australian Mineral Economics (AME) and Bloomsbury Mineral Economics (BME).

Data produced by Brook Hunt/Wood Mackenzie has been and continues to be used extensively by our clients who regularly reference our information in their publications. For example, we publish so-called annual ‘Benchmark’ terms between concentrate buyers and sellers, described later in this report, and we are specifically named in some copper concentrate contracts as the reference source for this data.

In 1990 I initiated an annual research offering entitled ‘Global Outlook for Copper Concentrates and Blister/Anodes’ and was the author of this study until 2011 and the editor thereafter. Up until 2011, I was also responsible for writing the commentary on copper supply and concentrate/blister markets in Brook Hunt’s monthly copper publication entitled ‘Copper Metal Service’. Since then I have been the editor of this report. I remain in regular contact with producers, consumers and traders of copper concentrates and I am a recognised authority in this market. The aforementioned reports are available on a multi-client annual subscription basis. Clients that subscribe to the abovementioned reports include mining, smelting and trading companies, governments and financial institutions.

(Footnote omitted.)

40 G.I.A.G. has been a client of Brook Hunt; so too has the Commissioner of Taxation.

41 Mr. Wilson was asked to answer the following questions:

(a) whether the conditions (individually or together) that operate under the 1999 Off-take agreement as amended from time to time and including as amended by the Third Replacement Concentrate Agreement (together with its Addendums and Amendment) as they applied in the 2007 to 2009 calendar years differ from those that might be expected to operate between a producer/seller of copper concentrate in the position of [CMPL] and a purchaser independent of CMPL having regard to the circumstances of CMPL in the period 1999 to February 2007; and

(b) if they do,

(i) how such conditions differ; and

(ii) what profits (if any) may have been expected to accrue to CMPL by reason of such differences?

42 Mr. Wilson examined the terms upon which C.M.P.L. sold copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. Using his extensive experience of the copper market, he formed the view that the adoption of the price sharing formula that was in fact adopted by C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. in February 2007 was commercial and prudent given the volatile nature of the copper market. Contrary to the Commissioner’s submission, Mr. Wilson’s opinion was not limited to issues of commerciality and prudence. He expressed his answer to the questions asked of him in his first report in the following way:

For the reasons set out later in this report, I am of the opinion that the conditions both individually and taken together that operate under the 1999 Off-take agreement as amended from time to time including as amended by the Third Replacement and Concentrate Agreement (together with its Addendums and amendment) as they applied in the 2007 to 2009 calendar years did not (with the exception of the payment terms) differ either in respect of their contractual terms or in respect of the expected financial impact of those terms from those conditions that might be expected to operate between a producer/seller of copper concentrate in the position of CMPL and a purchaser (including a purchaser having substantially the same characteristics as Glencore International AG (GIAG)) which is independent of CMPL.

(Footnote omitted.)

43 Mr. Wilson gave evidence that price sharing is a recognised way of pricing T.C.R.C.s in a market where both the price of copper and T.C.R.C.s are “highly volatile”, noting in particular that spot T.C.R.C.s were “virtually impossible to predict”. He estimated that, at its peak in 2008, the tonnage of copper concentrate that had been contracted globally under price sharing contracts was equivalent to about 9% of the seaborne trade in copper concentrates in the Asian smelting region. He gave his opinion that price sharing had advantages for both buyers and sellers. They existed whether or not a mine produced larger or smaller quantities of concentrate. They were as follows:

• it allows for greater certainty of the projected cash flows for the mine/project as TCRCs are correlated with the income stream (i.e. the LME copper price);

• it makes the annual negotiating process easier because conditions applied to price-sharing contracts are typically set for periods of 3-13 years and are not negotiated annually. Under some price-sharing contracts the price-sharing percentage is able to be varied in accordance with terms as set out in the original contract. Where a contract provides for such a variation it almost invariably results in an increase in the price-sharing percentage;

• it makes the project economics easier to understand for providers of funds, if applicable, as part of the costs are determined by the copper price through the price-sharing mechanism. For the copper price, as opposed to the TCRC, there is a long history of data available for statistical analysis;

• when a floor price on the price-sharing exists, it effectively guarantees the buyer a minimum price which can provide the impetus for the development of additional smelting capacity (which was necessary during the 1990s) to accommodate the extra concentrate producing capacity. Under the CMPL-GIAG price-sharing contract there was no floor price. This would have been a significant benefit to CMPL under a low or very low copper price scenario. Most price-sharing contracts that I am aware of have/had price-sharing floors, i.e. a minimum price for the buyer;

• it removes volatility arising from the movement of the LME copper price and TCRCs in opposite directions.

To illustrate the volatility that is removed by price sharing, Mr. Wilson observed that in 1998, despite the approximate 25% drop in annual average copper prices, the T.C.R.C.s as a percentage of copper prices had increased from 27% to 33% for a relative increase of 21%.

44 In Mr. Wilson’s opinion there is no standard price sharing contract. He said some contracts have the following features:

(a) a price-sharing range between defined LME price caps and/or floors;

(b) percentages of price-sharing that vary according to the LME copper price;

(c) a fixed percentage of price-sharing regardless of LME copper price;

(d) annual price-sharing escalators linked to a US GNP adjustment.

45 As for the fixing of a percentage of the copper price, Mr. Wilson observed, as already mentioned, that the normal range was 21-26%. That range had not altered materially since the early 1990s. The lowest percentage he had ever seen in a price sharing contract was 20%. He then turned to consider the price sharing clause adopted by C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. in February 2007. In his opinion, it was reasonable and prudent for C.M.P.L. to have adopted the clause, as it was the operator of a high cost mine and the copper price was expected to undergo a steep decline after having achieved an exceptionally high price. His observation on the copper price was illustrated by the following graph, based as it was on Brook Hunt’s long term copper price forecast as at December 2006.

46 Notwithstanding the general expectation of a steep decline in prices, Mr. Wilson observed that “there was considerable uncertainty as to the extent and time over which prices would decline”. Nevertheless, using the forecast figures in C.M.P.L.’s 2007 Budget, the operation of the 23% price sharing clause meant that C.M.P.L.’s profits were still expected to be “healthy.”

47 In his subsequent report, Mr. Wilson identified all of the “unknowns” as at February 2007. These included future L.M.E. copper prices for the 2007 to 2009 years, benchmark T.C.R.C.s for 2008 and 2009 (those for 2007 were known by February 2007), spot T.C.R.C.s for the 2007 to 2009 years (Brook Hunt does not attempt to forecast spot prices as they are too volatile), and whether or not price participation would be re-introduced. In his commercial judgment, having regard to the history of the C.S.A. mine (it had previously closed down in 1998 due to poor profitability) and the mine’s high costs, an overriding consideration for a miner in the position of C.M.P.L. would have been to ensure that the C.S.A. mine remained a viable going concern.

48 Mr. Wilson opined that fixing the T.C.R.C.s at 23% eliminated C.M.P.L.’s exposure to annual volatility arising from a formula that depended on both benchmark and spot T.C.R.C.s. To illustrate the volatility, Mr. Wilson observed that in the space of just two years (2004 to 2006) the average annual L.M.E. copper price had risen by 135%, and the realised benchmark T.C.R.C.s had increased by 254%. Mr. Wilson reasoned:

The use of full price-sharing terms as set out in the CMPL-GIAG Contract in 2007 removed one of the two unknowns by eliminating the volatility of TCRCs. The absence of a price-sharing floor gave CMPL added protection as the buyer was not guaranteed a minimum share of the price. It also meant that CMPL would have known precisely at any time during this three-year contract what CMPL’s net price would have been for any given copper price. Put another way, by fixing the TCRC at 23% of the copper price CMPL would have known with a high level of certainty the breakeven copper price for the CSA mine in each of the three years through the fixing of the TCRC. In my opinion, this is particularly important for a high cost mine such as CMPL which can quickly move into a loss position as copper prices decline (as was anticipated by market commentators in late 2006 and as shown by the LME forward price curve for copper (see figure at paragraph 38 of my first report)). Although it is apparent in hindsight that copper prices did not decline significantly over the three year period, benchmark TCRCs did not increase significantly, and price participation was not reintroduced, the use of the price-sharing arrangement was, in my opinion, a conservative and reasonable approach to minimising risk. If copper prices had fallen significantly over the three year period and TCRCs had increased, CMPL could have endured serious financial difficulties.

Critically, it was Mr. Wilson’s opinion that the adoption of a price sharing clause such as that adopted by C.M.P.L. in February 2007 was ultimately “a matter of commercial judgment having regard to the particular risk appetite and cost pressures facing a particular mine.”

49 Mr. Wilson’s conclusions about commerciality and prudence were criticised by the Commissioner as falling short of the statutory tests set out in Div. 13 and Subdiv. 815-A. It followed, it was said, that the taxpayer had failed to discharge its onus of proof. We respectfully disagree with that criticism. Mr. Wilson gave his opinion which sufficiently addressed the statutory test in Subdiv. 815-A (as reflected in the question asked of him) which we have already set out above. Because the case presented by both parties did not distinguish between Div. 13 and Subdiv. 815-A, it did not matter that he was not also asked a question which more directly engaged the statutory test in Div. 13. In any event, conclusions about commerciality and prudence are, in our view, conclusions about what parties dealing at arm’s length in the copper concentrate market might be expected to agree to in a contract of sale. As Allsop C.J. observed in Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v. Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2017) 251 F.C.R. 40 at 50-51 [42]:

[T]he ultimate purpose is to determine the consideration that would have been given (that is implicitly, by the taxpayer) had there not been a lack of independence in the transaction. How one comes to that assessment and the relationship between the posited arm’s length dealing and what in fact occurred will depend on the circumstances at hand, and a judgment as to the most appropriate, rational and commercially practical way of approaching the task consistently with the words of the statutory provision, on the evidence available.

(Our emphasis.)

50 Mr. Wilson’s opinion about the use of price sharing terms in contracts entered into between arm’s length parties was, in his view, supported by other contracts in the market that he was aware of. For example, in his first report he said the following:

I am aware of other price-sharing contracts involving Australian miners in the period prior to 2007. Northparkes (owned at the time by Rio Tinto and a Sumitomo consortium) had contracts with Japanese smelters between 1995 and 2002, with price-sharing rising from 21% initially, to 23.5% in the final year. Osborne (owned then by Placer Pacific) also had contracts with Japanese smelters, between 1996 and 2000, with price-sharing rising from 22.5% to 23.8% over the life of the contract.

As regards other price-sharing contracts, a further price-sharing contract that I have seen a copy of, is between Tritton Resources Ltd (Tritton), now owned by Aeris Resources, and trading company, Sempra. This contract was between unrelated parties and is similar to the CMPL-GIAG agreement in terms of being an Australian miner-trader contract with a price-sharing mechanism.

The Tritton contract was more complex than the CMPL-GIAG arrangement, with the percentage of price accruing to the buyer varying according to copper price. The contract had a minimum price sharing of 21%, increasing up to 27.5% with specified increases in the copper price. Ultimately Tritton was unable to fully perform the Sempra contract and renegotiated the terms. I do not believe that the failure of Tritton to perform the original contract was due to the price-sharing element of the contract.

(Footnotes omitted.)

51 Mr. Wilson also considered the quotational period optionality clause in the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement. He said that such clauses were recognised in the copper industry where the price of copper can vary significantly from month to month. In his view, some sellers required a financial inducement for the conferral of optionality on the buyer. Importantly, in his view, not all did so. Optionality was especially attractive to traders so that they could match the periods for purchases and deliveries of copper products, or hedge differentials in the periods used in purchase and sales contracts. Mr. Wilson examined a number of contracts for the sale of copper concentrate between independent parties and summarised the different selections of the quotational periods used in them. In his opinion, had C.M.P.L. sold its copper concentrate to independent smelters or traders, it would have been exposed to multiple quotational periods. In Mr. Wilson’s opinion, the move in 2004 to multiple quotational periods was a logical choice following the closure of the Port Kembla smelter in August 2003. Following this, G.I.A.G., instead of selling all of the C.S.A. mine’s copper concentrate to one smelter, became exposed to the risk of multiple smelter contracts using different quotational periods.

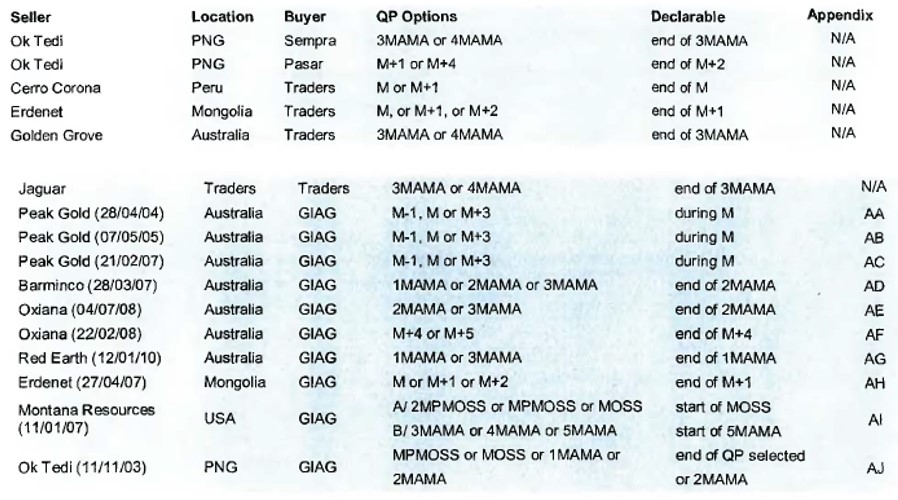

52 Mr. Wilson also considered the back pricing aspect of the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement. Again, he referred to a number of contracts entered into between independent parties where back pricing was used. He included in his report the following table of such contracts.

53 He also stated that based on his previous discussions with traders, back pricing was “common” in contracts used by “Trafigura, Louis Dreyfus, Gerald Metals, MRI, Ocean Partners, Sempra, Transamine, Traxys etc.” Whilst both quotational period optionality and back pricing were thought to be desirable for traders, in Mr. Wilson’s view the dollar value of such a benefit was “virtually impossible to predict in advance and is simply the “price paid” by the producer for the significant benefit of having a guaranteed purchaser for all of its production.”

54 In Mr. Wilson’s opinion, one clause in the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement differed from that usually found in copper concentrate contracts. G.I.A.G. was obliged to pay 100% of the provisional value of any concentrate produced but not shipped 14 days after the end of each production month. This gave C.M.P.L. a benefit; it gave it reliable cash flow and interest free working capital.

55 The Commissioner’s first expert was Mr. Marc Ingelbinck, who had “retired from corporate life at the end of 2010,” and was a self-employed consultant at the time of the trial. He has had extensive experience in relation to mining and trading in non-ferrous metals. From 2002 to 2010 he had been the Vice President, Marketing and Trading for B.H.P.’s Base Metals Customer Sector Group (our references to “B.H.P.” should be read as references generally to the dual listed company arrangement that exists between B.H.P. Group Limited and B.H.P. Group p.l.c., as those entities are now known). He had overall responsibility for the marketing of all of B.H.P.’s concentrate. This included copper concentrate. B.H.P. was the single largest supplier of custom copper concentrate in the market. As such, it was often the driver of benchmark T.C.R.C.s.

56 In his first report, Mr. Ingelbinck was asked to answer the following questions:

(1) For the [2007 to 2009 years], do the conditions that were operating between CMPL and GIAG in their commercial and financial relations, differ from the conditions which might have been expected to operate between an Independent Producer/Seller and Independent Buyer dealing wholly independently with one another? If so:

(a) how and to what extent do such conditions differ; and

(b) what profits (if any) by reason of these conditions might reasonably have been expected to have accrued to CMPL but for those conditions?

(2) For the [2007 to 2009 years], is the consideration received or receivable by CMPL for the sale of Cobar copper concentrate to GIAG different from the consideration that might reasonably have been expected to have been received or receivable for the sale of Cobar copper concentrate by an Independent Producer/Seller to an Independent Buyer dealing wholly independently with one another? If so:

(a) how and to what extent; and

(b) what consideration might reasonably have been expected to have been received or receivable by an Independent Producer/Seller but for that difference?

(3) Please answer the above questions in the alternative and assuming that the Independent Producer/Seller was the operator of the Cobar Mine in the period 1 January 1999 to 31 December 2009 and:

(a) operated in a commercial context as a wholly owned subsidiary of a multinational global resources company in the same or similar circumstances to that of CMPL and GIAG; or

(b) for the period between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2009 operated as a stand‑alone producer/seller of Cobar copper concentrate.

57 He was also asked, more generally, to consider Mr. Wilson’s expert reports and to comment on them.

58 Mr. Ingelbinck reviewed the terms upon which C.M.P.L. had historically sold copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. He was of the view that the initial 1999 offtake agreement had been generally structured as a traditional benchmark type contract. His focus, however, was on the amendments made to the terms of that agreement in 2004, 2005 and then in 2007. In his view, an independent seller would not have agreed to those amendments as they uniformly favoured the position of the buyer to the detriment of the seller. His views remained constant even where the independent seller was assumed to be the operator of the C.S.A. mine, either in a commercial context as a wholly-owned subsidiary of a multinational global resources company in the same or similar circumstances to that of C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. (Question 3(a)), or as a stand-alone seller of copper concentrate from the C.S.A. mine (Question 3(b)).

59 More particularly, Mr. Ingelbinck had never seen in long-term benchmark contracts a quotational period optionality clause as “liberal” as that enjoyed by G.I.A.G. An independent party would not have agreed to such an amendment as there was “zero quid pro quo granted to CMPL for the introduction of this optionality despite the fact that it materially improved the commercial position of GIAG.” Optionality, he said, equals value; the greater the optionality the greater the value. Moreover, by the end of 2006, in his view the market was aware that benchmark T.C.R.C.s were falling. The benchmark set for 2007 for 30% concentrate, which was known by the end of 2006, was US15.4c/lb. That being so, the 23% price sharing clause, based on projected copper prices, would have resulted in higher T.C.R.C.s: it would have resulted in T.C.R.C.s which were four times higher than the 2007 benchmark T.C.R.C.s (a similar observation could not be made about the 2008 and 2009 benchmark T.C.R.C.s as these were unknown in early 2007; we also note that Mr. Ingelbinck’s observation loses force when one takes into account the volatility of annual T.C.R.C. benchmarks). There was “zero justification” for such a change, which only made sense if the copper price were to average US67c/lb over the 2007 to 2009 years. But the “likelihood of this happening was essentially non-existent given the cost pressures faced by copper mines.” In contrast, Mr. Wilson was of the view that a miner in 2006 could reasonably have been somewhat sceptical about the accuracy of forecasting copper prices. We shall return to this issue.

60 Mr. Ingelbinck strongly disagreed with Mr. Wilson’s opinion that the terms upon which C.M.P.L. sold copper concentrate to G.I.A.G. were reasonable and prudent. In his first report he gave the following reasons for that opinion:

(a) the copper price had risen significantly over the course of the year – the LME forward curve on 1 January 2007 indicated a then prevailing value of at least $6,100/MT or approximately $2.75/lb for QP’s associated with 2007 shipments – I do note that Brook Hunt’s December 2006 copper price forecast projected lower figures than the above and that LME forward curve valuations can fluctuate on a daily basis but the value of projected 2007 shipment QP’s remained high during the late 2006 period

(b) 2007 benchmark discussions were well advanced with a consensus view that the outcome would be $60/dmt and 6.0 c/lb or 15.4 c/lb for 30% concentrate

(c) the concentrate market had tightened significantly and market observers such as Brook Hunt were forecasting such conditions would continue to exist for a number of years.

(Footnotes omitted.)

61 In Mr. Ingelbinck’s opinion, the switch to price sharing was “irresponsible” (emphasis in original). An independent seller in the position of C.M.P.L., when offered price sharing, should have answered with a simple “thanks but no, thanks.” In cross-examination, he said that if arm’s length parties in the circumstances of C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. had wanted to adopt price sharing in early 2007, a starting point might have been a rate of 8.1%, being the forecast average T.C.R.C.s as a percentage of the copper price for the 2007 to 2009 years (as extracted from the December 2006 Brook Hunt report). This was a “far cry” from the rate of 23%. He accepted, however, that no buyer would have agreed to purchase copper concentrate with price sharing fixed at a rate of 8.1% of the copper price.

62 In his cross-examination, Mr. Ingelbinck maintained his position that C.M.P.L. should not have agreed to the change to price sharing. His focus, as we understood it, was not upon whether the terms and conditions upon which copper concentrate was sold by C.M.P.L. to G.I.A.G. from 2007 were of an arm’s length nature, but rather, whether given the pre-existing terms and conditions it made sense to agree to the amendments made in February 2007. This can be seen in the following answer given by him in cross-examination:

And it is also a situation where you are not actually looking at establishing a contract, you are being asked to make a change from an existing contract so, under those circumstances, I would expect any commercial team to do a fairly serious analysis of, “Okay, so we can stay with what we have and what are the implications of that?” Making certain assumptions over a relatively short period of time, and then looking at the implications of making the switch to the suggested new pricing approach and evaluating what, under those same circumstances, the result is on your revenues.

63 Mr. Ingelbinck characterised price sharing as a “bet”. C.M.P.L. was betting in 2007 that in 2008 and 2009 the benchmark T.C.R.C.s would exceed 23% of the copper price. The last time this had occurred was in 2001. The force of that observation was diminished, in our view, by the sheer unpredictable volatility in copper prices at the time, and in particular following the unprecedented copper price increase in 2006 which resulted in confusion amongst copper industry participants. In the meantime, Mr. Ingelbinck observed that the benchmark T.C.R.C. rates from 2002 to 2006 had been 21.9%, 17.3%, 10%, 17.7% and 15% respectively. But comparing the use of benchmark T.C.R.C.s as against the use of a price sharing clause assumes that benchmark T.C.R.C.s would have been adopted by C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. in 2007 as the only means of determining T.C.R.C.s annually. In the past, this had not been the case. Prior to February 2007, benchmark T.C.R.C.s were used in the C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement as a basis for negotiating only 50% of the Base Tonnage (and the remaining 50% used spot market T.C.R.C.s as a basis). The C.M.P.L.-G.I.A.G. agreement was silent on their use as a basis for negotiating sales in excess of the Base Tonnage. Significantly, as will be seen, the Commissioner contends that this pre-existing pricing formula was arm’s length in nature.

64 Mr. Wilson had referred in his evidence to a contract for the sale of copper concentrate entered into by B.H.P. Billiton Marketing A.G. and B.H.P. Billiton Tintaya S.A. dated 16 December 2003 (the “B.M.A.G.-Tintaya Contract”). Mr. Ingelbinck, who had worked for B.H.P., had been involved with this contract. It was not an arm’s length contract, but a contract entered into by two B.H.P. subsidiaries. Consistently with its transfer pricing obligations, B.H.P. had sought to determine an arm’s length price for this contract. It chose a price sharing formula using a rate of 25.5%. That exceeds the rate used by C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G. Mr. Ingelbinck sought to explain why this rate had been chosen as follows:

The agreement was formalized on 16 December 2003 but had been under discussion for quite some time before that. Copper prices averaged $0.743/lb in the 2001-2003 period (a situation which had triggered a temporary curtailment of the Tintaya copper concentrate operations). We felt that given that background, a one third price sharing component at 25.5% was reasonable at that time.

65 Somewhat defensively, he then said:

I am not aware of the final outcome but I do recall that the results of the Tintaya-BMAG distribution agreement ended up being challenged by the Peruvian tax authorities.

66 In relation to the contracts relied upon by the taxpayer in support of the price sharing clause adopted by C.M.P.L. and G.I.A.G., Mr. Ingelbinck was otherwise generally of the opinion that they were not comparable either because the tonnage involved was too small or because the contracts had not been entered into contemporaneously with early 2007.