FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Trivago N.V. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

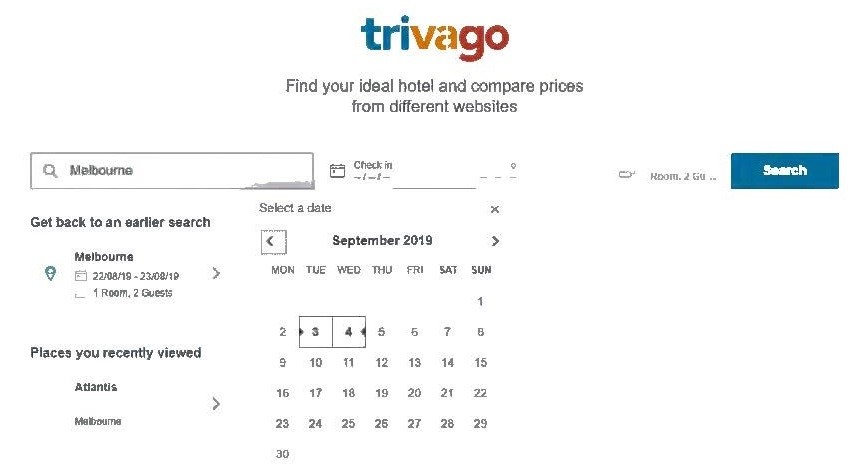

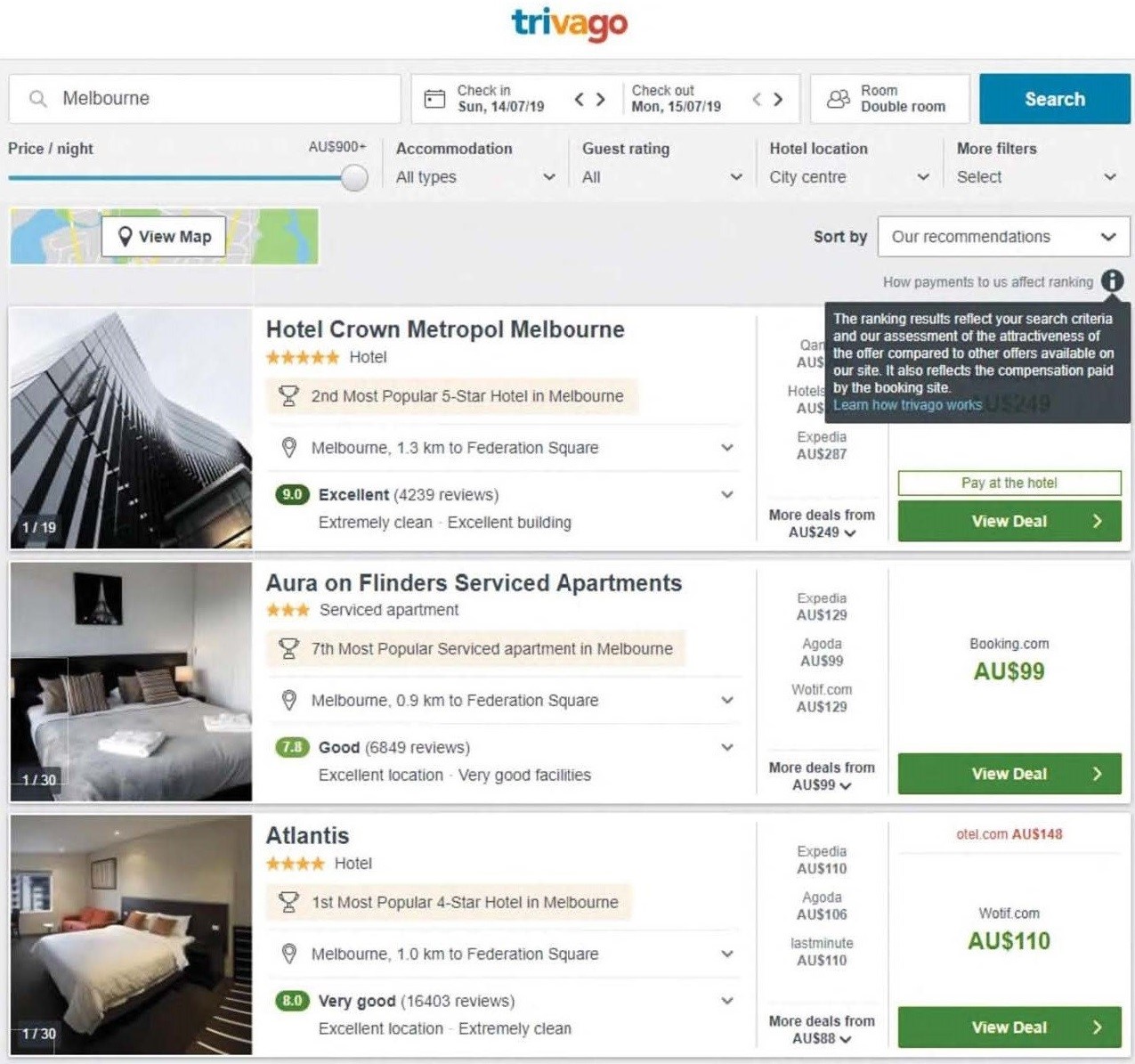

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The appellant pay the costs of the respondent, to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 150 of 2020 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | TRIVAGO N.V. Appellant | |

AND: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Respondent | |

JUDGES: | MIDDLETON, MCKERRACHER AND JACKSON JJ |

DATE OF ORDER: | 4 november 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. To the extent that it is necessary, leave is granted for the appellant to appeal from the orders of the primary judge made on 28 February 2020 at Melbourne in proceeding VID 1034 of 2018.

2. The appeal be dismissed.

3. The appellant to pay the costs of the respondent, to be assessed if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of Contents

THE COURT:

1 The appellant, Trivago N.V., operates an online search and price comparison site for hotel accommodation. The Trivago website swiftly aggregates hotel room offers from many online sites and displays those options to the user.

2 The issue in this appeal is whether the information Trivago conveyed or, importantly, did not adequately convey to consumers who used the Trivago website between 1 December 2016 and 13 September 2019 (the Relevant Period), either alone or together with Trivago’s advertising, was misleading or deceptive or likely to be so.

3 At trial the primary judge held that it was. For the reasons that follow, his Honour’s conclusion was substantially correct.

4 The appeal (and therefore these reasons) are factually intense. It follows that it is also necessary on the appeal to address the evidence in detail. But for two evidentiary sub-issues, only one substantive point of law arises.

2. THE NATURE OF THE TRIVAGO WEBSITE

5 Central to this appeal is an understanding of the Trivago website as an aggregator of hotel offers, as distinct from Online Booking Sites whose websites allow consumers to directly book hotel rooms. Online Booking Sites reached arrangements with Trivago in order that their hotel offer prices would be displayed on Trivago’s website so as to reach potential consumers who might then click through from Trivago’s website to the Online Booking Site and make a booking.

6 At dates relevant to the litigation, the Landing Page of the Trivago website enabled consumers to input a city (or region) in a search bar, to select their desired dates and room type, and to choose the filter they wished, if any, to produce results. When a consumer initiated a search of this nature, the Trivago website would display an initial set of search results in response to the selection criteria inserted by the consumer (the Initial Search Results Page). This page displayed a list of hotels. Each hotel listing was displayed in substantially the same format. To the left of the screen in each instance was an image relating to the hotel being advertised and certain information about it. On the right were multiple offers for each hotel from identified Online Booking Sites. One such offer was displayed on the far right side in green text in a standalone column (for example, “Booking.com AU$299”). This was known as the Top Position Offer. On occasions a box was displayed underneath the Top Position Offer, showing that the Top Position Offer had particular attributes, such as free cancellation or free WiFi, pay at the hotel (rather than in advance) etc.

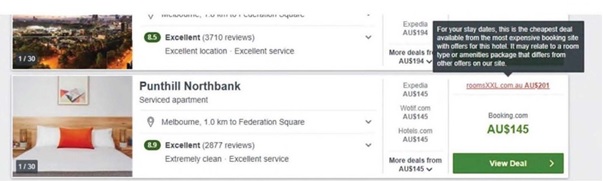

7 Additionally, there were three offers along with each of the Online Booking Sites’ names, displayed in smaller sized grey text directly to the left of the Top Position Offer (for example, Expedia AU$299, Wotif AU$299, Destina AU$420). These were described at trial as the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers. Underneath the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers a “More Deals button” was displayed which, when clicked, would show, by way of a “slide-out” function (More Deals slide-out), additional offers for the selected hotel. Initially the More Deals button indicated the number of further offers within the More Deals slide-out. After about 5 December 2017, the More Deals button was changed to read “More Deals from AU$...”. It would display the price of the cheapest deal contained in the More Deals slide-out, for example, “More Deals from AU$227”. The cheapest deal contained in the More Deals slide-out was sometimes at a lower price than the Top Position Offer.

8 There was a “sort by” filter option which appeared above the listings on the Initial Search Results Page. The default filter was “our recommendations”. Other filters included “price only”, “rating only” and “distance only”. Additional filtering tools were available to consumers who wanted to exclude offers on the Initial Search Results Page including a price per night scrolling bar, where consumers could set the maximum cost per night. They could also filter by accommodation type, for example, hotel or house/apartment; and by hotel location, for example, number of kilometres from the city centre.

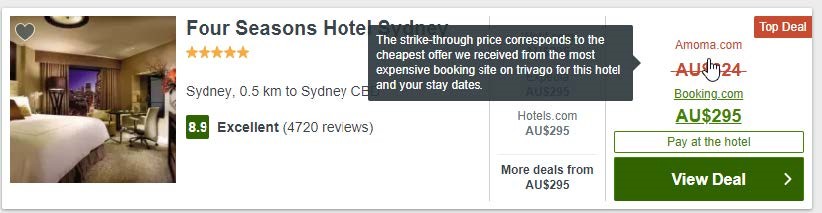

9 Prior to about 20 November 2018, above the Top Position Offer, for some hotel listings on the Initial Search Results Page, there was a higher priced offer from another named Online Booking Site in red strike-through text. This was known as the Strike-Through Price. From on or about 20 November 2018, the Strike-Through Price was replaced by red text without a strike-through, in a smaller text size referred to in the litigation as the Red Price. The Red Price was only displayed for some hotel listings.

10 The primary judge found (against Trivago’s contention) that most consumers would only stay on the Trivago website for a short time. If a consumer clicked an Online Booking Site’s offer on the Initial Search Results Page, he or she would be referred away from the Trivago website to the Online Booking Site’s website in order to view that offer in greater detail and to complete a booking, if the consumer wished to do so.

11 An important aspect of the litigation was that the contractual terms between Trivago and the Online Booking Sites required the latter to pay Trivago a fee if a consumer clicked on the advertiser’s offer on Trivago’s website. This fee was described as the CPC or “cost per click”. The CPC would be payable regardless of whether the Online Booking Site converted the click into a booking. The CPC payable by the Online Booking Site, was the amount bid by them directly to Trivago. Trivago did not charge a fee to consumers for use of its website. Another issue in the litigation was whether consumers were informed about the existence or effect of the CPC, or whether or not they should have been.

12 The order of the Top Position Offer and the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers was determined by Trivago’s proprietary Algorithm. Expert evidence was adduced as to various aspects of the Trivago Algorithm. The experts agreed that there were several inputs into the Algorithm, including the offer price, the historical click through rate for the hotel, the CPC, and the priority modifier.

13 Another issue at trial was the degree to which the CPC influenced the determination of the Top Position Offer. The respondent (the ACCC) particularly emphasised that most of Trivago’s revenue was derived from the CPC fees. Online Booking Sites made CPC “bids” to Trivago in respect of the offers they wished to have displayed when consumers conducted searches via the Trivago website.

14 The Online Booking Sites knew, because Trivago told them, that the higher a CPC bid, the more likely it was that an offer would be prominently displayed when a consumer conducted a relevant search. Whether Trivago adequately disclosed to consumers the role that the CPC bids played in determining the hotel offers displayed is one of the issues upon which this appeal turns.

15 Evidence was adduced at trial, not only as to the operation of the Trivago website at various times, but also as to Trivago’s advertising. Consumers of Trivago’s website were, by Trivago’s advertising, invited to look for their “ideal hotel for the best price” or “the best deal on accommodation”.

16 The ACCC contended that ordinary and reasonable users of Trivago’s website were looking for the best available hotel room offer that corresponded to their needs in relation to matters such as location, date and type of room at the cheapest available rate. It contended that the best available offer for the consumer’s chosen hotel was the cheapest offer that conformed to those needs, or an offer other than the cheapest offer if it had some other characteristic making it more attractive than cheaper available offers.

17 By making CPC bids, Online Booking Sites would compete to be displayed as the Top Position Offer which was displayed much more prominently and attractively by Trivago than other offers.

18 In the period from 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018, there were over 20 million site visits where consumers clicked on Top Position Offers, but only 4.73 million visits where they clicked the More Deals slide-out showing offers additional to the Top Position Offer and the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers shown on the Initial Search Results Page.

19 However, the Top Position Offer was the cheapest available offer for a hotel room only 33.2% of the time. The ACCC stressed that in 66.8% of cases, cheaper offers for the same room were available. Some cheaper available offers were not displayed at all because Trivago did not display offers from Online Booking Sites if the site’s CPC bid for the offer was below a minimum amount determined by Trivago.

20 The ACCC also asserted that when the Top Position Offer was more expensive than other available offers, this was not because there was some other characteristic that made the Top Position Offer more attractive to a consumer.

21 Rather, the ACCC said, amongst other things, that the most important factor that determined why a higher priced offer was displayed as the Top Position Offer above a lower priced offer for the same hotel was the value of the CPC bid by the competing Online Booking Sites.

22 During that part of the period when the Red Price was displayed above the Top Position Offer, the ACCC contended that this display implied a “like-for-like” comparison between available offers for the same room but without informing consumers clearly or at all that the Red Price might be higher because it related to a superior room or a room with superior amenity in the same hotel.

23 At trial, Trivago did not call any of its officers or employees to give evidence.

24 The findings against Trivago at trial were extensive. Some contraventions were admitted by Trivago and some contraventions, which were found by the primary judge to be established, are not the subject of appeal.

25 The facts recorded in this section were not in dispute.

3.1 Trivago’s advertising and marketing

26 During the Relevant Period, Trivago used a number of advertising methods to advertise its website to Australian consumers, including a series of television advertising campaigns.

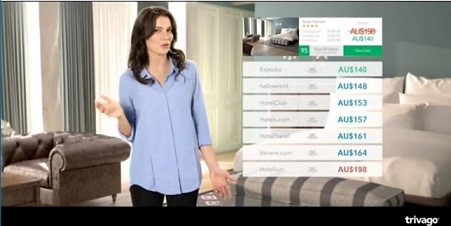

27 Although there were numerous iterations and variations, each television advertisement adhered to a similar format in which a presenter would make oral statements about the Trivago website.

28 For example, in one of the advertisements that aired on Australian television networks between 10 January 2016 and 26 September 2017, the presenter (pictured below) stated as follows:

Have you ever looked for a hotel online?

Did you notice that there are so many different prices out there for the exact same room?

Trivago does the work for you and instantly compares the prices of over 600,000 hotels from over 200 different websites.

So, instead of searching for hours or spending too much, Trivago makes it easy for you to find the ideal hotel for the best price.

Just go to Trivago, type in where you want to go, and with two clicks select your check-in and check-out dates and search. It’s that simple.

Trivago searches hundreds of websites at the same time and shows you the most popular hotels. You can adjust the price so that it fits in with your budget, or select the number of stars, or filter by average guest ratings from over 100 million reviews.

Remember, Trivago shows you all the different prices for the exact same room, and that’s how you can be sure that you find your ideal hotel for the best price.

Hotel? Trivago

29 In addition, Trivago aired a number of advertisements throughout different times in the Relevant Period, in some cases starting before, but then continuing into the Relevant Period. Among those advertisements were the following that included statements relevant to the present appeal:

(a) between 28 August 2016 and 29 May 2017, Trivago caused a television advertisement to be aired on television networks in Australia stating:

there are so many different prices all over the internet. And Trivago instantly compares them all to find your ideal hotel for the best price

(b) from 13 January 2017 to 29 May 2017, Trivago caused television advertisements to be aired on television networks in Australia containing the following statements:

Trivago makes it easy for you to find the ideal hotel for the best price …

You can be sure that you can find your ideal hotel at the best price …

Remember, Trivago shows you all the different prices for the exact same room. And that’s how you can be sure that you find your ideal hotel for the best price

(c) between 20 December 2016 and 2 July 2018, Trivago caused television advertisements to be aired, which included the following statement:

and that’s one more way Trivago helps you find your ideal hotel at the best price.

30 In the period 29 June 2017 to 1 April 2018, a television advertisement with the following statements was aired on Australian television networks:

Did you notice that there are so many different prices out there for the exact same room?

I know I’ve been asking this a lot lately, but this is what it really means. The same hotel room can have up to ten different prices across the internet. So even if you spend a lot of time looking around, chances are, it is still out there for a better price. So make one last check before you book, the Trivago check.

Trivago compares prices from more than 200 websites to make sure you find your ideal hotel for the best price.

Hotel? Trivago

31 In the period between 19 December 2017 and 1 April 2018, a television advertisement with the following statements was aired on Australian television networks:

There are plenty of booking websites. Your ideal hotel may only be listed on one, or on several, but for very different prices. Do you really want to check them all?

Instead, use Trivago to compare these offers and find your ideal hotel for the best price.

Hotel? Trivago

32 In addition to the television advertisements, between 1 December 2016 and on or around 19 June 2017, Trivago caused the following statements to be made in a “snippet” which appeared beneath Google search results displayed when Australian consumers conducted a search for “Trivago”:

Compare over 250 booking sites and find the ideal hotel at the best price!

Compare hotels, find the cheapest price and guarantee the best deal on accommodation …

33 The Landing Page for the Trivago website displays the Trivago logo. During the first part of the Relevant Period (defined below), the logo was accompanied by the slogan: “Find your ideal hotel for the best price”. Later in the Relevant Period, this was changed to read: “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from many websites”. It was subsequently changed again, by replacing the word “many” with the word “different”.

34 Because of various changes in the presentation of material, either advertising or content on the Trivago website, it was necessary to break up the Relevant Period in respect of the allegations raised by the ACCC into four periods, which the primary judge designated as follows (at [17]):

…

(a) the period from 1 December 2016 to 29 April 2018 (the first relevant sub-period), a period of approximately 17 months;

(b) the period from 29 April 2018 to 20 November 2018 (the second relevant sub-period), a period of approximately seven months;

(c) the period from 20 November 2018 to 13 February 2019 (the third relevant sub-period), a period of approximately three months; and

(d) the period from 13 February 2019 to 13 September 2019 (the fourth relevant sub-period), a period of approximately seven months.

35 It was then necessary to apply different descriptions to those periods, which his Honour dealt with in the following way (at [18]):

Consistently with the approach taken by the parties, the website during the first relevant sub-period will be referred to as website version 1, the website during the second relevant sub-period will be referred to as website version 2, the website during the third relevant sub-period will be referred to as website version 3 and the website during the fourth relevant sub-period will be referred to as website version 4. It should be noted that the appearance of the website was not necessarily static within each sub-period; on some occasions, as detailed below, changes were made within a sub-period.

3.2 The first relevant sub-period (1 December 2016 to 29 April 2018)

36 In the period from about 1 December 2016 to 4 January 2018, the slogan beneath the logo on the Landing Page read: “Find your ideal hotel for the best price”. Further below, under the heading “Find cheap hotels on trivago”, appeared the statement:

With Trivago you can easily find your hotel at the lowest rate. Simply enter where you want to go and your desired travel dates and let our hotel search engine compare accommodation prices for you.

(Emphasis in original.)

37 As at 4 January 2018, the top part of the Landing Page appeared as follows:

38 Prior to 12 April 2018, another slogan appeared on the Trivago website. This read: “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from many websites”. From on or about 12 April 2018, the slogan was amended to state: “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from different websites”.

39 The statement of agreed facts in the proceedings below included various screenshots of website version 1. These included the following screenshots of individual hotel listings:

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

40 In response to a consumer search, website version 1 generated an Initial Search Results Page containing a number of individual hotel listings, each of which displayed:

(a) the Top Position Offer in the column furthest to the right. The Top Position Offer was the most prominently displayed offer for the hotel. It was displayed in large green text together with the Online Booking Site’s name and a green “view deal” click-out button. In addition, some hotel listings on the Initial Search Results Page displayed a box underneath the Top Position Offer showing that the Top Position Offer had particular attributes including, for example, “Pay at the hotel” or “Free cancellation” (see, for example, Fig 3 above);

(b) the Strike-Through Price in red strike-through text above the Top Position Offer;

(c) the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers in smaller size text (compared with the Top Position Offer and Strike-Through Price). These offers were displayed less prominently than the Top Position Offer and were contained in one column;

(d) the More Deals button, with bolded black text indicating (until about 5 December 2017) the number of further offers contained in the More Deals slide-out (e.g. “More deals: 22”; see Fig 1 above);

(e) a red box above the Top Position Offer and Strike-Through Price which showed the percentage difference between the two prices (Percentage Savings box) (see Fig 2 above); and

(f) a Top Deal box would replace the Percentage Savings box if, among other factors, the Top Position Offer was at least 20% lower than the Strike-Through Price, the hotel had a rating of at least three stars and the hotel met Trivago’s internal rating index for quality (see Figs 1, 3 and 4 above).

41 Between May 2017 and January 2018, the Trivago website displayed the Strike-Through Price as the Fourth Position Offer (in addition to it appearing directly above the Top Position Offer; see Fig 1 and Fig 2). In or around January 2018, the Strike-Through Price ceased to be shown as the Fourth Position Offer (see Fig 3 and Fig 4).

42 In addition, during the first relevant sub-period, the following changes were made to the Initial Search Results Page:

(a) on or about 5 December 2017, the More Deals button on Trivago’s desktop website ceased to include the text indicating the numbers of further offers contained within the More Deals slide-out; instead, the bolded black text was changed to read “More deals from AU$...” and displayed the price of the cheapest deal contained in the More Deals slide-out (e.g. “More deals from AU$226”; see Figs 2, 3 and 4);

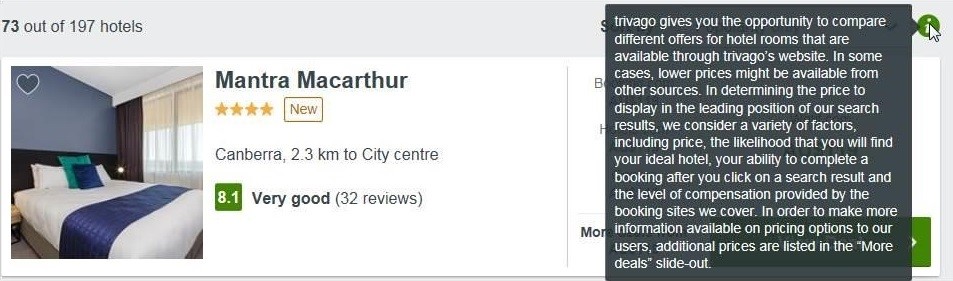

(b) on or about 6 October 2017, the Trivago website began displaying the Our Recommendations information button with a hover-over. If a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Our Recommendations information button, the hover-over would display text stating:

Trivago gives you the opportunity to compare different offers for hotel rooms that are available through Trivago’s website. In some cases, lower prices might be available from other sources. In determining the price to display in the leading position of our search results, we consider a variety of factors, including price, the likelihood that you will find your ideal hotel, your ability to complete a booking after you click on a search result and the level of compensation provided by the booking sites we cover. In order to make more information available on pricing options to our users, additional prices are listed in the “More deals” slide-out.

(see the “Mantra Macarthur” listing above.)

(c) from about 27 January 2018, the text displayed if a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Our Recommendations information button stated:

The ranking results reflect your search criteria and our assessment of the attractiveness of the offer compared to other offers available on our site. It also reflects the compensation paid by the booking site.

(d) on or about 29 March 2018, a hover-over was added in respect of the Strike-Through Price. If a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Strike-Through Price, the following text was displayed:

The strike-through price corresponds to the cheapest offer we received from the most expensive booking site on Trivago for this hotel and your stay dates.

(see the “Four Seasons Hotel” listing above).

(e) on or about 29 March 2018, a hover-over was added for the Percentage Savings box. If a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Percentage Savings box, the following text was displayed:

This figure represents the difference between the strike-though deal price and the featured deal price [i.e. the Top Position Offer].

(see Fig 4 above).

(f) on or about 29 March 2018, a hover-over was added for the Top Deal box (which was only displayed if the conditions were met). If a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Top Deal box, the following text was displayed:

This deal is at least 20% cheaper than the strike-through deal price and its Trivago Rating Index is above 7.5.

3.3 The second relevant sub-period (29 April 2018 to 20 November 2018)

43 From 12 April 2018 (i.e. just before the start of the second relevant sub-period), the words on the Landing Page read: “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from different websites”. During the second, third and fourth relevant sub-periods, the Landing Page therefore appeared as follows:

44 In response to a consumer search, the Initial Search Results Page in website version 2 displayed the same features as website version 1 (set out at [40]-[42] above).

45 However, during the second relevant sub-period, the following changes to the Initial Search Results Page occurred:

(a) in or around August 2018, the text displayed if a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Strike-Through Price was amended to state:

This is the cheapest deal from the most expensive booking site with offers for this hotel on your stay dates.

(b) on or about 6 August 2018, the Top Deal box was removed from the Trivago website.

46 Website version 2 also had the following new features:

(a) from about 3 July 2018, some information about Trivago’s Algorithm and the ranking of offers on the Initial Search Results Page was provided to consumers under the link “Learn how Trivago works”; and

(b) in about October 2018, the text displayed if a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Our Recommendations information button was amended to include a hyperlink to the “Learn how Trivago works” page. Consumers who clicked on that link were taken to a new page on the Trivago website that stated:

How does Trivago determine the ‘our recommendations’ sort?

The ‘our recommendations’ feature is based on a dynamic Algorithm that shows you a range of attractive and relevant offers we think you’re going to love. In the ‘top position’ we display in green the offer which our Algorithm recommends as a great offer. Our Algorithm takes into account a number of relevant factors, such as your search criteria (for example your location and stay dates), the offer’s price, and its general attractiveness – for example the experience we think you’ll likely have on the displayed booking site. We also take into account the compensation booking sites provide us with when a user clicks on an offer.

To the left of the ‘top position’ offer and/or under the ‘more deals from’ tab, we display additional offers to allow you to compare other deals for the same hotel. You may find offers under the ‘more deals from’ slide-out section with a lower price than the ‘top position’ offer. While price is an important factor when selecting our ‘top position’ offer, we believe other factors, such as those mentioned above, make offers attractive and relevant to you, and contribute to high levels of satisfaction by our users.

Ultimately, our mission is to give you the information and tools to help you find your ideal hotel.

3.4 The third relevant sub-period (20 November 2018 to 13 February 2019)

47 Website version 3 was displayed during this period.

48 In response to a consumer search, the Initial Search Results Page in website version 3 displayed:

(a) the Top Position Offer in the column furthest to the right. The Top Position Offer was the most prominently displayed offer on the Trivago website. It was displayed together with the Online Booking Site’s name and a green “view deal” click-out button. In addition, some hotel listings on the Initial Search Results Page displayed a box underneath the Top Position Offer showing that the Top Position Offer had particular attributes including, for example, “Pay at the hotel” or “Free breakfast” (consistently with website versions 1 and 2);

(b) (for some of the hotel listings only) a Red Price from identified Online Booking Sites in smaller text above the Top Position Offer with a hover-over. If a consumer’s mouse cursor hovered over the Red Price, the following text was displayed:

For your stay dates, this is the cheapest deal from the most expensive booking site with offers for this hotel. It may relate to a room type or amenities package that differs from other offers on our site.

(see “Punthill Northbank” listing below).

(c) the Second, Third and Fourth Position Offers in smaller size text (compared with the Top Position Offer) to the left of the Top Position Offer. These offers were displayed less prominently than the Top Position Offer and were contained in one column (consistently with website versions 1 and 2);

(d) the More Deals button as described in [42(a)] above; and

(e) the Our Recommendations information button as set out in [42(c)] and [46(b)] above.

49 Website version 3 did not include the following features:

(a) the Strike-Through Price (save to the extent the Strike-Through Price continued to appear in the map portion of the Trivago website);

(b) the Percentage Savings box; and

(c) the Top Deal box.

50 On or about 14 January 2019, it came to Trivago’s attention that the words “best price” appeared in a subset of unpaid Trivago-related Google search results in Australia. To produce its unpaid search results, Google ‘crawls’ internet pages, including the metadata of those pages. Although Trivago updated the metadata of the Trivago website, Trivago inadvertently did not update the metadata of the pages for individual hotels on the Trivago website. As a result, Google search results for individual hotels (e.g., for a Trivago listing for the Hilton in Sydney) included a snippet that included the words “best price”. Trivago subsequently updated the metadata for these pages. This error did not affect Trivago’s paid advertisements or its other unpaid listings on Google.

3.5 The fourth relevant sub-period (13 February to 13 September 2019)

51 On or about 13 February 2019, it came to Trivago’s attention that Strike-Through Prices continued to appear on the map portion of the Trivago website. When searching for hotels in a particular location, a user could select an option to view a map that included relevant offers. The map was inadvertently not updated and, as a result, Strike-Through Prices continued to be displayed when users hovered over price symbols on the map. Trivago removed these Strike-Through Prices promptly after becoming aware of this issue on or about 13 February 2019. Therefore, during the fourth relevant sub-period, the Strike-Through Price no longer appeared in the map portion of the Trivago website.

52 Website version 4 displayed the following:

53 In response to a consumer search, the Initial Search Results Page for website version 4 displayed the same features as website version 3 (as described at [48] above.

54 From about 17 April 2019 the words “How payments to us affect ranking” appeared next to the Our Recommendations information button on website version 4. The hover-over accompanying the Our Recommendations information button continued to read as set out in [42(c)] and [46(b)] above.

55 Trivago informed the ACCC by correspondence of the following matters, which were treated as proven facts:

(a) in the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018 new search results were displayed on Trivago’s Australian website 217,514,783 times;

(b) Trivago does not record the number of users visiting its Australian website or the number of times a user enters a location or region in Trivago’s search bar. However, Trivago records the number of user “sessions”. A session starts when a user first interacts with the Trivago website and continues until the user has been inactive for one hour. For example, if a user visits Trivago’s Australian website and is then inactive for an hour before interacting with the site again, two user sessions will be logged by Trivago’s system;

(c) in the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018 there were 4,421,184 sessions on Trivago’s Australian website where the sorting order was changed from the default sorting option to a different sorting option;

(d) in the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018 there were 4,726,241 sessions on Trivago’s Australian website where the More Deals slide-out was displayed;

(e) in the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018 there were 1,400,205 sessions on Trivago’s Australian website where a user clicked on a deal displayed in the More Deals slide-out;

(f) in the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018 there were 20,039,530 sessions on Trivago’s Australian website where the Top Position offer for any hotel listing was clicked; and

(g) in the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018 there were 68,783 sessions on Trivago’s Australian website where a comparison rate, being the Fourth Position Offer that was the same as the Strike-Through Price (see Fig 2 above) was clicked.

4. THE ASSERTED REPRESENTATIONS

56 The ACCC contended that Trivago made a number of key representations throughout the Relevant Period (with some representations made only during certain sub-periods) that amounted to conduct in contravention of s 18 (misleading or deceptive conduct), s 29(1)(i) (false or misleading representations about the price of goods and services) and s 34 (misleading conduct as to the nature of services) of the Australian Consumer Law (sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)). It sought declarations to that effect.

57 Those asserted representations were as follows:

(a) The Cheapest Price Representation during the first relevant sub-period. Through online and television advertising, Trivago is alleged to have represented that its website would quickly and easily identify the cheapest rates available for a hotel room responding to a consumer’s search when in fact the Trivago website did not enable consumers to quickly or easily identify the cheapest rates available for particular hotel rooms. This is said to contravene s 18 and s 34 of the Australian Consumer Law;

(b) The Top Position Representation during the entire Relevant Period, which is said to contravene s 18 and s 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law by prominently displaying on the Trivago website, Top Position Offers (which were sometimes accompanied by a Top Deals box or a Percentage Savings box) and thereby representing that the Top Position Offers were the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel, or had some other characteristic which made them more attractive than any other offer for that hotel when in fact:

(i) the Top Position Offers were not always the cheapest available offers for an identified hotel;

(ii) Trivago did not select the Top Position Offers by reference to any other characteristic which may have made them the most attractive offer; and

(iii) Trivago selected the Top Position Offers primarily by reference to the CPC bids Trivago would receive from the Online Booking Site if a consumer clicked on that Online Booking Site’s offer.

(Emphasis added.)

(c) The Strike-Through Representation during the first and second relevant sub-periods, which is said to contravene s 18 and s 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law by displaying the Strike-Through Price above the Top Position Offer on the hotel listing display and the map portion of the Trivago website, and thereby representing that the Strike-Through Price was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel when in fact the Strike-Through Price that Trivago displayed often related to a more expensive room category than the Top Position Offer;

(d) The Red Price Representation, which together with the Strike-Through Representation during the third relevant sub-period is said to contravene s 18 and s 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law by:

(i) displaying the Red Price above the Top Position Offer on the hotel listing display, and thereby representing that the Red Price was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel when in fact the Red Price that Trivago displayed often related to a more expensive room category than the Top Position Offer; and

(ii) displaying the Strike-Through Price above the Top Position Offer on the map portion of the Trivago website, and thereby representing that the Strike-Through Price was a comparison between prices offered for the same room category in the same hotel, when in fact the Strike-Through Price that Trivago displayed often related to a more expensive room category than the Top Position Offer.

58 Further, during the fourth relevant sub-period, when the Strike-Through Price was completely removed from the Trivago website, the ACCC contends that Trivago continued to make the Red Price Representation by engaging in the same conduct as described at (d)(i) above.

59 The ACCC also sought declarations in relation to the additional conduct allegations. In relation to the first relevant sub-period, it was alleged that Trivago contravened s 18 and s 34 of the Australian Consumer Law by:

…

making the Cheapest Price Representation, and by making Top Position Offers together with the Top Position Representations and the Strike-Through Representation, and thereby leading consumers to believe that the Trivago website provided an impartial, objective and transparent price comparison which would enable them to quickly and easily identify the cheapest available offer for a particular (or the exact same) room at a particular hotel when, in fact, the Trivago website:

(c) did not enable consumers to quickly or easily identify the cheapest prices available for a particular hotel room; and

(d) directed consumers to more prominently displayed offers made by Online Booking Sites that offered to make higher CPC payments to Trivago than competing Online Booking Sites each time a consumer clicked on the offer, irrespective of the prices offered to consumers for a particular hotel room.

60 In relation to the second and third relevant sub-periods, the ACCC sought a declaration in similar terms, save that, rather than relying on the Cheapest Price Representation (which is alleged only in respect of the first relevant sub-period), the ACCC relied on Trivago making Top Position Offers on the Trivago website, making the Top Position Representation, making the Strike-Through Representation, and:

advertising the Trivago website using statements such as: “Compare over 250 booking sites and find the ideal hotel at the best price!”; “find your ideal hotel and compare prices from different websites”; “impartial comparison”; “find the ideal hotel at a great price”; and “Compare & Save. No Ads or Pop-Ups”.

(Emphasis added.)

61 In relation to the fourth relevant sub-period, the declaration sought was similar to that sought in respect of the second and third relevant sub-periods. The ACCC relied on Trivago making Top Position Offers on the Trivago website, making the Top Position Representation, making the Red Price Representation, and advertising the Trivago website using statements such as: “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from different websites”; “impartial comparison”; “find the ideal hotel at a great price”; and “Compare & Save. No Ads or Pop-Ups”.

62 The ACCC also contended in its Further Amended Concise Statement (FACS) (at [12]-[19]) that:

12 Contrary to the Top Position Representation, the Top Position Offer was not always the cheapest available offer and Trivago did not select it by reference to any other characteristic which may have made it the most attractive offer. Trivago selected the Top Position Offer primarily by reference to the value of the CPC Trivago would receive from the advertiser who submitted the offer.

13 Trivago used an Algorithm to determine the Top Position Offer. The Algorithm placed a significant weighting on the value of an advertiser’s CPC bid. By applying the Algorithm, Trivago gave greater prominence to offers from advertisers who had submitted higher CPC bids than to cheaper offers at the same hotel from advertisers who submitted lower CPC bids. In addition, from at least May 2017 to at least October 2017, Trivago set a minimum CPC amount. If an advertiser submitted a CPC bid below this amount, the Algorithm prevented the Trivago website from displaying the advertiser’s offer, even if it was the cheapest price offer Trivago had received. The result was that often the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest price offer Trivago had received for the relevant hotel.

…

15 Beneath the Fourth Position [Offer], Trivago displayed a “More Deals” button. Clicking on this button opened a list of other offers which advertisers had submitted for the same hotel. From at least May 2017 to at least October 2017, the “More Deals” button did not display the cheapest price offer which Trivago had received for that hotel. In addition (as set out in paragraph 13) if an advertiser made a CPC bid that was less than a predetermined minimum, Trivago did not display the advertiser’s offer on its website at all, even if it was the cheapest price offer Trivago had received for the hotel. From a date not before October 2017, Trivago changed the “More Deals” button to display the cheapest offer it had received and introduced a mouse over information button in respect of the top position Algorithm. These changes did not affect the Top Position Representation.

…

19 By making the Strike-Through Representation and the Red Price Representation (separately or in combination) [and] by displaying the Percentage Saving or Top Deal box next to the Top-Position Offer, Trivago reiterated and reinforced the Top Position Representation. One effect of this was that consumers (especially those who had viewed advertising in which Trivago made the Cheapest Price Representation) were less likely to open the “More Deals” list, even after Trivago amended the button to identify that cheaper price offers were available. …

(Emphasis added.)

63 In a confidential annexure to the FACS, the ACCC compared the number of visits to the Trivago website in which a consumer clicked on an offer located in the More Deals slide-out with the number of visits in which a consumer clicked on a Top Position Offer. The figures provided related to the period from 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018, which captures most of the first relevant sub-period. During this period the latter figure was much higher than the former.

64 By its Concise Response, Trivago raised various matters, including the following:

5. Trivago acts as a metasearch site and not as a direct booking site. Trivago’s primary function is to aggregate and compare accommodation offers from different Online Booking Sites in a manner that consumers find helpful. The booking sites appearing on Trivago’s website include participating hotels and online travel agencies. If a consumer clicks on the booking site’s offer on the Trivago website, the consumer is taken to the booking site’s online booking service and completes the booking using the booking site’s service. Trivago does not provide the booking service.

6. Trivago’s contractual terms require booking sites to pay Trivago a fee if a consumer clicks on the booking site’s offer on the Trivago website (referred to as the “cost-per-click” or “CPC”). The CPC is Trivago’s principal source of revenue. Trivago does not charge fees to consumers who use its service.

7. Trivago’s business offers booking sites a marketplace on which to advertise their hotel offers. The CPC payable by the booking site to Trivago to advertise their hotel offer is the amount bid by the booking site on Trivago’s marketplace, subject to a minimum CPC determined by Trivago.

(Emphasis added.)

…

C. Lowest rate statements

24. Trivago admits that during the following periods, it described and marketed its Australian website in the following mediums and using statements to the following effect:

(a) between 1 December 2016 and 4 January 2018, as alleged by the ACCC, the Trivago website stated:

“Find your ideal hotel for the best price”;

and

“With Trivago you can easily find your ideal hotel at the lowest rate. Simply enter where you want to go and your desired travel dates and let our hotel search engine compare accommodation prices for you.”;

(b) between 1 December 2016 and 19 June 2017, as alleged by the ACCC, Trivago caused the following statements to be made in the snippet which appeared beneath the Google search results displayed when Australian consumers conducted an online search for Trivago:

“Compare over 250 booking sites and find the ideal hotel at the best price!”;

and

“Compare hotels, find the cheapest price and guarantee the best deal on accommodation...”;

(c) between 28 August 2016 and 29 May 2017, as alleged by the ACCC, Trivago caused a television advertisement to be aired on television networks in Australia on 10,933 occasions stating:

“...there are so many different prices all over the internet. And Trivago instantly compares them all to find your ideal hotel for the best price.”;

(d) from 13 January 2017 to 29 May 2017, as alleged by the ACCC, Trivago caused television advertisements to be aired on television networks in Australia on 4,761 occasions containing the following statements:

“Trivago makes it easy for you to find the ideal hotel for the best price”;

and

“You can be sure that you can find your ideal hotel at the best price”;

and

“Remember, Trivago shows you all the different prices for the exact same room. And that’s how you can be sure that you find your ideal hotel for the best price.”

25. Trivago admits that the statements referred to in paragraph 24 (lowest rate statements) conveyed to ordinary consumers that:

(a) the Trivago website is easy to use; and

(b) the Trivago website assists consumers in finding their ideal hotel accommodation at the lowest rates advertised by a wide range of booking sites through the Trivago website for that hotel on the relevant stay dates.

26. Trivago says that, at all relevant times:

(a) the Trivago website has been easy to use; and

(b) the Trivago website has in fact assisted consumers in finding their ideal hotel accommodation at the lowest rates advertised by a wide range of booking sites through the Trivago website for that hotel on the relevant stay dates.

27. However, for the purposes of this proceeding, Trivago admits that:

(a) while the Initial Search Page Offers were selected by Trivago from the lowest rates advertised by those booking sites on the Trivago website for that hotel on the relevant stay dates, those rates were not always the lowest rates advertised on the Trivago website for that hotel on the relevant stay dates;

(b) the lowest rate statements may have caused some consumers to form an erroneous belief that the Initial Search Page Offers were the lowest rates advertised on the Trivago website for that hotel on the relevant stay dates; and

(c) to that extent, during the relevant period until 29 April 2018, Trivago engaged in conduct in contravention of s 18 and s 34 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL).

28. As noted above, from on or about 29 April 2018, Trivago ceased making the lowest rate statements.

D Strike through pricing

29. Trivago admits that, during the relevant period until on or about 20 November 2018, in response to a consumer search for accommodation in a particular region on particular stay dates, the initial search results page on Trivago’s website displayed, in respect of each hotel listed:

(a) a Strike-Through Price with a “hover-over” which stated: “This is the cheapest deal from the most expensive booking site with offers for this hotel on your stay dates.”; and

(b) in the circumstances referred to earlier, a Percentage Savings box and a Top Deal box.

30. For the purposes of this proceeding, Trivago admits that:

(a) while the Strike-Through Price for each hotel listed on the initial search results page was the lowest rate from the most expensive booking site with offers for that hotel on the relevant stay dates, the room rate did not always relate to the same room category as the Top Position Offer;

(b) by displaying the Strike-Through Price next to the Top Position Offer in the form it was displayed (using a “strike-through” notation) either on its own or in conjunction with the Percentage Savings box and the Top Deal box, Trivago may have caused some consumers to form an erroneous belief that the Top Position Offer and the Strike-Through Price were offers for rooms in the same room category; and

(c) to that extent, by displaying the Strike-Through Price next to the Top Position Offer in the form it was displayed during the relevant period until on or about 20 November 2018 either on its own or in conjunction with the Percentage Savings box and the Top Deal box, Trivago engaged in conduct in contravention of s 18 and s 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL).

31. As noted above, from on or about 20 November 2018, Trivago altered the “hover-over” in respect of the Strike-Through Price to state that the price may relate to a room type or amenities package that differs from other offers on the site.

32. Further, from on or about 20 November 2018, Trivago ceased using the “strike-through” notation and also removed the Percentage Savings box and the Top Deals box.

5. THE CONTRIBUTION OF EXPERT EVIDENCE

65 There was expert evidence at trial. It was relevant not to the question of whether representations were made, a question for the primary judge, but to the question of the underlying content and computation of data on the website and to the habits of relevant consumers, being a topic going to their likely perceptions on using the Trivago website. The expert evidence was also relevant to the question of the accuracy of the content on the Trivago website.

66 The ACCC called two witnesses:

Professor Robert Slonim, a Professor in the School of Economics, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney; and

Mr Victor Bajanov, who holds the position of Executive, Product Analytics at Quantium, a global data and analytics firm headquartered in Sydney.

67 Trivago also called two expert witnesses:

Professor David C Parkes, a Professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard University; and

Mr Patrick Smith, partner at RBB Economics.

68 Additionally, there was a joint report dated 22 August 2019 of Mr Bajanov and Professor Parkes, which highlighted their areas of agreement and disagreement (the Joint Report). They gave evidence concurrently.

69 In relation to the computer science experts, Mr Bajanov and Professor Parkes, the primary judge was satisfied that each expressed opinions independently and impartially and each was knowledgeable about the topics they were questioned on. There was an initial report from Mr Bajanov dated 15 May 2019 (the First Bajanov Report) addressing nine questions that had been set out in his letter of instructions. Professor Parkes responded by a report dated 15 July 2019 (the First Parkes Report). Mr Bajanov prepared a reply report on 5 August 2019 (the Second Bajanov Report). Professor Parkes prepared a further report on 22 August 2019 (the Second Parkes Report). Their concurrent evidence was structured around the nine questions set out in the Joint Report. It was conducted in closed court due to the commercial sensitivities of some aspects of Trivago’s Algorithm and other data provided by Trivago.

70 In considering the evidence given by these experts by reference to the nine common questions, the primary judge recorded the following evidence and his findings:

5.1.1 Question 1: Making reference to the source code, pseudocode and written descriptions in the documents provided, provide a brief, high-level description of how the Top Position and Default Sorting Algorithms operated

71 The primary judge found there was general agreement between the experts in relation to this question. Trivago’s Algorithm calculated a “composite score” for each offer made by an Online Booking Site with respect to a hotel listing. (The word “offer” referred to the offer price for the hotel room, rather than the CPC bid.) The offer with the highest composite score became the Top Position Offer for that hotel listing.

72 The inputs to the composite score (as set out in the Joint Report) were:

(a) the offer price, the CPC and the priority modifier;

(b) hotel position, average historical price, historical click-through rate; and

(c) minimum listing price, maximum listing price, minimum priority CPC, maximum priority CPC, minimum gain and maximum gain.

73 The priority modifier was a value that adjusts the CPC value, as discussed further below. The priority CPC was the CPC multiplied by the priority modifier. The expression “gain” was a quantity related to the estimated revenue Trivago could expect to receive from showing an offer, calculated as the product of the predicted click-through rate on the offer and the priority CPC.

74 The priority modifier, described by Professor Parkes as a “kind of quality adjustment”, was made to the CPC bid of an Online Booking Site. While there was agreement between the experts that the priority modifier was strongly correlated with, or heavily dependent on, a value called the “Landing Page score”, the evidence regarding the Landing Page score was incomplete. Professor Parkes’ understanding of the Landing Page score was based on the information that Trivago provided to Online Booking Sites and Trivago’s Response to the ACCC, but the statements in those documents were not proved in evidence by Trivago. Trivago did not call any of its officers or employees to give evidence.

75 Thus, the primary judge said that while it may be accepted that Trivago stated in those documents that the Landing Page score is a measure of the “quality” of the Online Booking Site’s Landing Page in terms of user experience, he was not prepared to accept that the Landing Page score actually operated in that way. As Professor Parkes said in his evidence, neither he nor Mr Bajanov had been able to analyse how Trivago went about calculating the Landing Page score. Further, Professor Parkes made clear that his conclusions regarding the Landing Page score were “contingent” on the statements made by Trivago to the Online Booking Sites and to the ACCC. In any event and fundamentally, the primary judge noted that, even if the Landing Page score did operate in the manner understood by Professor Parkes, it measured the quality of an Online Booking Site’s landing page, not the quality of the hotel accommodation offers themselves.

5.1.2 Question 2: What factors influenced whether an offer was selected as the Top Position Offer?

76 The experts agreed in the Joint Report that the following factors were the raw inputs into Trivago’s Algorithm:

(a) The minimum listing price: the minimum price among the competing offers within a listing;

(b) The maximum listing price: the maximum price among the competing offers within a listing;

(c) The hotel position in the search results;

(d) The historical click through rate for the hotel;

(e) The average historical price of the hotel over a pre-defined period;

(f) The offer price: the price provided by the Online Booking Site for a specific offer within a listing;

(g) The CPC: the CPC bid made by an Online Booking Site for a specific offer;

(h) The priority modifier: see the discussion in relation to question 1, above;

(i) The minimum gain and maximum gain of all offers within the listing; and

(j) The minimum priority CPC and maximum priority CPC for all offers within the listing.

5.1.3 Question 3: What was the weighting or relative importance of these factors?

77 This was the main area of disagreement between the experts. In the First Bajanov Report, Mr Bajanov utilised two methods to consider question 3:

(a) first, he considered the effect of the various factors on the composite score by reverse engineering Trivago’s Algorithm; and

(b) secondly, he considered the effect of the various factors on an offer being selected as the Top Position Offer by building a ‘Gradient Boosting Model’ (explained below).

78 Mr Bajanov had been provided with Trivago data for three dates (9 December 2017, 3 January 2018 and 5 April 2018) in respect of four capital cities. The reason Mr Bajanov adopted a reverse engineering approach in his first method was because he had not, at that stage, been provided with certain ‘weights’ used in the Trivago Algorithm. However, the primary judge said that in terms of the disagreement between the experts, little, if anything, turned on the fact that Mr Bajanov used a reverse engineering approach. This was because the major area of disagreement between the experts concerned Mr Bajanov’s second method, rather than his first method. Applying his first method, Mr Bajanov concluded that the three factors with the most influence on the composite score on 9 December 2017 were (in order of importance):

(a) offer price;

(b) CPC; and

(c) minimum listing price.

79 The concept of a Gradient Boosting Model was explained as being a machine learning algorithm commonly used by data science professionals to predict a single outcome given a set of raw input data; it was widely used due to its high accuracy and its ability to determine the relative contributions of the input factors to each predicted value. Applying this method, Mr Bajanov concluded that the CPC had the highest relative importance in determining which offer was most likely to be selected as the Top Position Offer, followed by the maximum priority CPC and the priority modifier. For example, he concluded that on 9 December 2017, the factors had the following relative importance:

(a) CPC (59.0%);

(b) maximum priority CPC (21.0%); and

(c) priority modifier (9.6%).

80 Under the Gradient Boosting Model, the CPC was the most important factor on all three dates, with a relative importance of between 52.9% and 59.2%. The range for the priority modifier was from 8.7% to 18.3%. The range for the offer price was from 0.7% to 1.0%.

81 Professor Parkes strongly disagreed with the appropriateness of the Gradient Boosting Model utilised by Mr Bajanov. He based his analysis instead on Trivago’s Algorithm, in circumstances where he had access to the “weights” used in the Algorithm, which Mr Bajanov did not have.

82 Applying his methodology, Professor Parkes concluded that:

(a) the offer price was the most important factor in selecting the Top Position Offer, with a relative importance between 45.5% and 60.0%;

(b) the CPC was the second most important factor on all three dates, with a relative importance between 33.8% and 44.8%;

(c) the priority modifier was the third most important factor on all three dates, with a relative importance between 4.0% and 13.3%; and

(d) the other factors set out above (at [76]) have no bearing.

83 Ultimately, the primary judge concluded that it was not necessary to form a concluded view as to which of the experts’ approaches was preferable. Mr Bajanov’s analysis involved looking at the events that happened and assessing the relative importance of the various factors in the selection of a particular offer as the Top Position Offer. Professor Parkes’ analysis involved assessing the relative importance of the various factors by making adjustments to those factors and assessing the effect of making such adjustments on the selection of an offer as the Top Position Offer. Each method addressed a different question, and the answers to both questions were of assistance to the primary judge in resolving the issues at first instance; in particular, the question whether, if the alleged representations were made, they were misleading or deceptive or liable to mislead.

84 Most importantly, however, the primary judge noted that, even on Professor Parkes’ approach, the CPC was a very significant factor in determining the Top Position Offer: it was the second most important factor, with a relative importance of between 33.8% and 44.8%. This was directly relevant to the contention of the ACCC in [13] of its FACS, rather than in [12] of the FACS (set out at [62] above).

5.1.4 Question 4: How and to what extent (if any) did the Top Position offer Algorithm filter certain offers made by advertisers?

85 It was common ground between the experts that Trivago’s Algorithm filtered out offers which did not meet a minimum gain threshold. Offers were also filtered out by a minimum CPC bid, the value of which was confidential.

5.1.5 Question 5: How important was an advertiser’s CPC payment in determining the Top Position Offer?

86 There was disagreement between the experts in relation to this question, but it is covered under question 3 in 5.1.3. The experts also agreed on several matters in relation to this question, including (as set out in the Joint Report) that 84.52% of listings had a Top Position Offer with an offer price lower than the mean of all offer prices submitted by Online Booking Sites, and a CPC higher than the mean of all CPC bids. The mean CPC within a listing was highest when the offer prices submitted varied the least within a listing. This demonstrated that high CPC and low-priced offers were not necessarily inconsistent. This statement was subject to the qualification that Mr Bajanov could not verify the calculations for the figure of 84.52%.

87 Professor Parkes said:

(a) approximately 86.5% of listings had a Top Position Offer lower than the mean of all offers; and

(b) conversely, approximately 13.5% of listings had a Top Position Offer higher than the mean of all offers.

5.1.6 Question 6: How “frequently” were higher priced hotel offers selected as the Top Position Offer over alternative, lower priced offers? In these cases (if any), what factor primarily determined why a higher priced offer was selected over a lower-priced offer?

(a) higher priced hotel offers were selected as the Top Position Offer over alternative lower priced offers in 66.8% of listings;

(b) in regard to the comparison with the lowest priced offer, the price of the Top Position Offer was the same in 33.2% of listings; within 1% in 63.1%, within 5% in 79.3%, within 10% in 88.7%, within 15% in 95.3%, and within 20% in 97.3%; and

(c) when a higher priced offer was selected as the Top Position Offer over the lowest priced offer, then the observable variation between the two offers was explained by a difference in CPC more than any other factor. The next most common factor was the priority modifier, which was the leading factor in between 2% and 8% of listings, depending on city and date.

89 The primary judge noted (at [126]) that in oral evidence the experts confirmed that the 66.8% figure referred to above (at [88(a)]) was based on their analysis of all the data provided to them; in other words, it included both offers that were displayed on the Trivago website and offers that were not displayed (i.e. those that were filtered out). In relation to [88(b)] above, the effect of these figures was that, in approximately 88% of cases, the variation between the Top Position Offer and the cheapest offer was less than 10%. Conversely, in approximately 12% of cases, the variation between the Top Position Offer and the cheapest offer was more than 10%.

5.1.7 Question 7: What percentage of listings had a Top Position Offer with the highest CPC of all offers within that listing? Further, how did CPC generally relate to offer price?

90 The experts agreed that 56% of the listings had a Top Position Offer with the highest CPC.

5.1.8 Question 8: What percentage of listings had a Top Position Offer with the cheapest price offer of all offers within that listing? What percentage of listings had a Top Position Offer within 1% or 5% of the cheapest offer of all offers within that listing?

91 The experts agreed that:

(a) as noted in answer to question 6 above, 33.2% of listings had a Top Position Offer that was the cheapest offer; and

(b) when the Top Position Offer was 10% or 20% higher than the minimum listing price, there was a discontinuity in the distribution of the price of other offers at the same 10% or 20% price points. The experts said that they had not been provided with data to definitively establish the cause of the discontinuity.

The statement in (b) was subject to the qualification that Mr Bajanov did not verify the calculations.

5.1.9 Question 9: Considering only listings where the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest price offer of all offers within that listing, what percentage of the Top Position Offers had a CPC value higher than the cheapest offer? Further, what were the other factors by which the Top Position Offer and cheapest price offer differed?

92 The experts agreed that, considering offers where the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer of all offers within a listing, 95.9% of the Top Position Offers had a CPC value higher than that of the cheapest offer.

93 There was a difference of opinion between the experts in relation to the second part of question 9. Professor Parkes referred to economic principles and academic literature concerning consumer behaviour in relation to the attributes of a hotel room. He stated that the academic literature documented that consumers believe that offers for a given hotel room are heterogeneous. Professor Parkes stated that he had created a dataset of listings where the Top Position Offer differed by more than 1% from the lowest price offer and had examined the variations in attributes between the Top Position Offer and the lowest price offer for the listings in this dataset. His analysis did not attempt to quantify the value of those attributes.

94 As the primary judge explained:

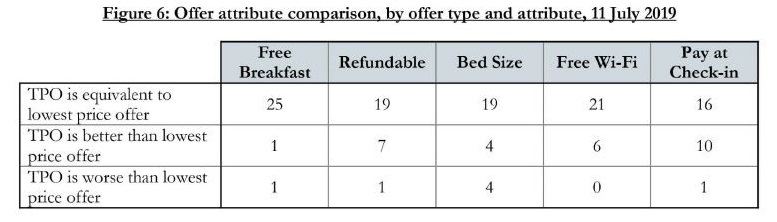

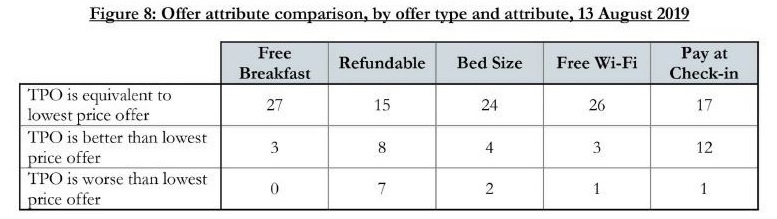

136 … in order to create this dataset, he searched the Trivago website for a one-night stay in Adelaide, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney four days in advance of check-in. (This was seen as a typical search that a consumer would do on the Trivago website ...) The search was carried out on 11 July 2019. From these searches, Professor Parkes examined all first page listings for which the Top Position Offer was at least 1% more than the lowest price offer listed. This yielded 27 listings. For each of the corresponding pairs of Top Position Offer and lowest priced offer, Professor Parkes recorded whether each of the Top Position Offer and lowest price offer included the following attributes: free cancellation; bed size; free Wi-Fi; pay at hotel; and free breakfast. The results of this analysis were set out in the report (and are set out later in these reasons).

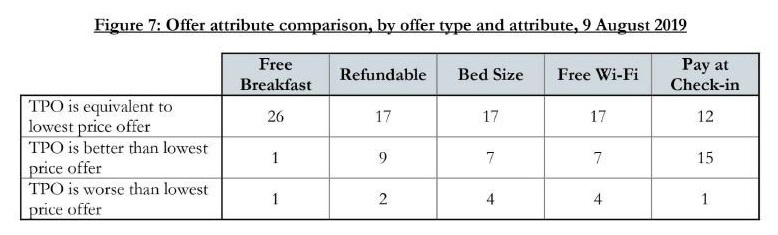

137 Following criticism of this analysis in the Second Bajanov Report, including on the basis of sample size, Professor Parkes supplemented his analysis by collecting additional datasets of listings on 9 August 2019 and 13 August 2019 ... Professor Parkes stated that this further analysis reaffirmed the conclusions in … his first report, namely that there is clear evidence of heterogeneity among offers for a hotel listing. Again, Professor Parkes examined all first page listings for which the Top Position Offer was at least 1% more than the lowest price offer listed. This yielded 28 listings for 9 August 2019 and 30 listings for 13 August 2019. For each of the corresponding pairs of Top Position Offer and lowest price offer, Professor Parkes carried out the same analysis as described above.

138 The results of this analysis were set out in Figures 6, 7 and 8 in the Second Parkes Report (including, at Fig 6, the results for 11 July 2019):

139 In the above figures, the statement “TPO [Top Position Offer] is equivalent to lowest price offer” means that the offering is equivalent in respect of the particular attribute – either they both have it or they both do not have it ... The statement “TPO is better than lowest price offer” means that the Top Position Offer is better than the lowest price offer in respect of the particular attribute – for example, the Top Position Offer has free Wi-Fi and the lowest price offer does not.

140 It should be noted that the above analyses were not based on the Trivago-provided dataset analysed by the experts and discussed above in relation to earlier questions. That dataset related to three earlier dates. Rather, the analyses set out in Figures 6, 7 and 8 were based on more recent searches carried out by Professor Parkes.

141 In oral evidence, Professor Parkes stated that: the results of these analyses were statistically significant; 87% of the time the Top Position Offer and the lowest price offer differed in non-price ways; moreover, where there was a statistically significant effect, it went in favour of the Top Position Offer ... Professor Parkes provided the following further observations, referring to his discussion with Mr Bajanov …:

And so where we have a discussion, I’m not even sure if it rises to a disagreement. It’s a discussion. Is how could this come about … So for me the way I think about it is now, if you will, there’s a bit of a mystery. I see that statistically significant effect in favour of non-price attributes – how can that be? We’ve had a discussion here today.

And I think there’s no disagreement about – that Trivago does not use non-price attributes to decide how to make a decision in regard to the top position offer. And as you think about it, there’s only one conclusion that makes any sense. The only conclusion that makes any sense – as Trivago has also stated – but it’s, indeed, the only conclusion that is consistent as an explanation with the data that I have observed – is that the cost per click – the bid is conveying, implicitly, information that is carrying this idea that the offer might be favourable in other ways. And that is how I believe these non-price attributes are coming into the Algorithm. And I think that’s quite clever.

This is an example of an incentive aligned way to get at information that would not be available to consumers otherwise. The CPC is conveying information in this case about the click to book rate on the site. And it’s information that would not otherwise be visible. And, in this case, through the design of the marketplace, the bids are in an incentive aligned way, it’s aligned with the incentives of the [Online Booking Site]. The bids are conveying this information.

(Emphasis added.)

95 Importantly for present purposes, the above passage makes it clear that Trivago’s Algorithm did not use non-price attributes to determine the composite score (and thus the Top Position Offer). This was common ground between the experts. Professor Parkes nonetheless inferred that the CPC was conveying information about the quality of the underlying offer, and that this was a desirable by-product of the CPC bid mechanism.

96 While Mr Bajanov accepted that the results of Professor Parkes’ analyses were statistically significant, he did not accept that such an inference should be drawn. Mr Bajanov stated in the Joint Report that the experts had no “visibility” as to the way in which Online Booking Sites “estimate or predict their prospective conversion rates in deciding on a CPC bid”. Therefore, in Mr Bajanov’s view, the experts could not make “any definitive statements about the role or importance of these particular non-price attributes”.

97 The primary judge accepted, correctly, that for this reason given by Mr Bajanov, it could not be inferred that the CPC is conveying information about the quality of the underlying offer.

98 The primary judge also concluded that, in any event, when comparing corresponding pairs of Top Position Offers and lowest priced offers, Professor Parkes did not seek to value the non-price attributes. His analysis did not, therefore, provide a basis to compare the relative values of the Top Position Offers and the lowest priced offers. The analysis also did not include offers that were excluded from the listings because they did not meet the minimum CPC threshold.

99 Professor Parkes’ analysis did not, therefore, compare the Top Position Offer with all other offers; it merely compared the Top Position Offer with the cheapest offer that was displayed. For these reasons, the primary judge concluded that the analysis cited above by Professor Parkes did not show that where the Top Position Offer was not the cheapest offer, it nonetheless had some other characteristic which made it more attractive than any other offer for that hotel. As will be seen, Trivago contends that this approach was wrong in principle, and also that the primary judge reversed the onus of proof. This will be addressed below.

5.2 Behavioural evidence – Professor Slonim

100 There was also expert evidence in relation to consumer behaviour. The ACCC sought to rely on a report of Professor Slonim dated 17 May 2019. The whole of the report was subject to objection by Trivago. The primary judge allowed some objections and having done so, commented on the remaining admissible consumer behaviour evidence.

101 Professor Slonim’s report and opinions related only to recreational (as opposed to business) travellers. Further, one of the assumptions Professor Slonim made was that consumers using the Trivago website paid for hotel accommodation at the time of making an online booking. This was not always the case. In some cases, the Top Position Offer was displayed on the Trivago website together with the words “Pay at the hotel”, indicating that the consumer could pay later. Professor Slonim’s evidence was to be understood subject to this qualification.

102 Professor Slonim expressed the following opinions, which the primary judge accepted:

(a) a traditional economics approach, as presented in most basic texts and university courses, assumes that consumers are “maximizers” who gather all available information on all available options and all attributes of every option (e.g., for a hotel room this could include price, amenities, location, services, room size, cancellation policies, applicable taxes, and so forth) to come to a rational (i.e., optimal) decision that maximizes preferences across all attributes. Although this assumption on rational decision-making might explain some macro level market behaviour, there was extensive research with robust evidence over the past 40 years showing that this rational decision-making approach was not descriptive of how most consumers in most contexts make decisions;

(b) in general, consumers were often time constrained, did not have all (or even most) information easily accessible, and could not easily process more than a small amount of information in making choices;

(c) these constraints resulted in consumers using short cuts (known as heuristics) to make choices, and these heuristics were subject to many biases, resulting in deviations from making optimal choices. These biases could be influenced by many seemingly irrelevant factors including, but not limited to: how information was presented, the order in which information was presented, and how choices were framed. The two most important, relevant and well-recognised biases were “present bias” and “loss aversion”;

(d) present bias is a bias in decision-making in which consumers place an inordinate amount of weight on factors that affect them in the present (whether it is a benefit or a cost). Traditional economic analyses have been well-aware for at least a century that consumers might rationally place somewhat more weight in the evaluation of choices on factors that occur sooner rather than later, but present bias indicates that the weight that people place on the present is quite dramatically more important in decisions than the traditional economic approach has considered;

(e) one important consequence of present bias for decision-making in general, and for booking a hotel in particular, was that since the costs of the time spent to find a room were borne at the time of making the decision (i.e., the present), whereas the benefits of finding the room occur in the future when the consumer gets to enjoy the room, consumers will look for ways to expedite the search process by taking shortcuts in the decision process to save time in the present;

(f) loss aversion is a bias in which consumers are assumed to make choices by comparing options with one item serving as the reference (or status quo or default) option and all other choices serving as the alternative options. The loss aversion bias in decision-making explains that in making comparisons to a reference option, an equally sized gain and an equally sized loss were treated quite differently in terms of evaluating each alternative option. This was demonstrated by considering two cases. Case 1: the reference hotel has a price of $180 and an alternative hotel has a price of $200, the alternative hotel option thus has a loss of $20 on price compared to the reference hotel. Case 2: the reference hotel has a price of $220 and an alternative hotel again has a price of $200, the alternative hotel in this case has a gain of $20 on price compared to the reference hotel. In both cases, there is a change in price of $20 between the alternative and the reference hotel;

(g) in Case 2, the relative gain of $20 to the consumer would factor positively on the consumer choice for the alternative hotel, but in Case 1 the $20 loss will weigh much more heavily into adversely affecting the choice for the alternative hotel than the gain would help in Case 2. As a consequence of loss aversion, an option that becomes the reference item would be much more likely to be chosen when there were various trade-offs across attributes, since every alternative would have some attributes that involve a loss compared to the reference item, and these losses weigh more heavily than any gains on other attributes in the evaluation of each alternative option;